Abstract

Accurate precipitation data are essential for effective water resource management. This study aimed to correct precipitation values from the ERA5_Ag reanalysis dataset using observational data from 20 meteorological stations located in the Tensift basin, Morocco. Five machine learning models were evaluated: MLP, XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest. Model performance was assessed using RMSE, MAE, R2, and bias metrics, enabling the selection of the best−performing model to apply the correction. The results showed significant improvements in the accuracy of precipitation estimates, with R2 ranging between 0.80 and 0.90 in most stations. The best model was subsequently used to correct and generate raster maps of corrected precipitation over 42 years, providing a spatially detailed tool of great value for water resource management. This study is particularly important in semi−arid regions such as the Tensift basin, where water scarcity demands more accurate and informed decision−making.

1. Introduction

Accurate precipitation data are used in a vast range of environmental applications, including hydrological modeling [1,2,3], climate change impact studies [4,5,6], water resources planning, drought and flood early warning systems [7,8,9,10,11,12]. In arid and semi−arid areas, such as the Tensift Basin in Morocco, accurate rainfall estimates are particularly necessary due to the region’s strong dependence on seasonal rains and its persistent vulnerability to water shortages. Nevertheless, long−term and spatially comprehensive ground−based rainfall data in such regions are usually restricted due to logistical, financial, and infrastructural challenges [13,14]. In response, there is growing reliance among scientists and practitioners on satellite and climate reanalysis−derived gridded rainfall products. These have large spatial coverage with high temporal resolutions, serving as desirable substitutes for sparse in situ observations. An example is the ERA5_Ag dataset prepared by the European Centre for Medium−Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), with global climatic parameters at a spatial scale of roughly 9.6 km, widely applied in hydrological and climatological research studies [15]. Despite their operational advantages, gridded rainfall products derived from satellites and climate are prone to systematic biases. These biases may arise due to sensor limitations, algorithmic assumptions, under−representation of convective storms, orographic complexity, and spatial smoothing over heterogeneous terrains [16,17]. Such biases can compromise the reliability of these datasets when applied directly in hydrological simulations, particularly in topographically complex and data−scarce basins like the Tensift Basin, where local convection and terrain−driven rainfall variability play a significant role.

To offset the systemic biases that are common in gridded rainfall outputs, several statistical bias−correction techniques have emerged and have been widely compared in the field. Ref. [18] performed a benchmark comparison of a few of the most employed methods involving linear scaling, delta change methods, and quantile mapping, describing their strengths and limitations for diverse hydrometeorological applications. Subsequently, Ref. [19] provided a real−world comparison of these corrections, with emphasis on usability and performance for diverse climatic conditions. In recent years, Ref. [20] provided a thorough survey of quantile−based methods of correction, including quantile mapping, scaled distribution mapping, and quantile delta mapping, thereby validating the relevance of these methods for increasing the reliability of climate and hydrological inputs. These, taken together, highlight the usability and value of statistical bias−correction methods for climate impact studies, hydrological modeling, and other use cases. These models perform well in most applications, but they are limited by assumptions of stationarity, linearity, or distributional structure, and they may struggle in replicating complex nonlinear relationships between raw gridded output predictions and observed values of precipitation. Recent developments in machine learning (ML) have provided new avenues towards enhancing gridded rainfall accuracy. ML models can identify nonlinear, multivariate relationships in large datasets without strict statistical assumptions. A growing body of research has utilized machine learning strategies−like Random Forests, gradient boosting machines, Support Vector Machines, and Deep Neural Networks for satellite−based and rainfall dataset reanalysis corrections [21,22,23]. These models have exhibited superior prediction performance, transferability across diverse climatic regions, and accommodation of heterogeneous data sources. Few studies, however, have thoroughly compared a number of ML models of rainfall bias corrections in semi−arid catchments with ground station coverage. In addition, little research has been conducted on generalizing such models across ungauged parts of the same watershed.

1.1. Objectives and Contributions

This study aims to address these research gaps by proposing a comprehensive machine learning framework for the bias correction of the ERA5_Ag rainfall product using ground−based observations from 20 meteorological stations in the Tensift Basin, Morocco. The following five ML models are implemented and compared: Random Forest Regressor, XGBoost Regressor, LightGBM Regressor, CatBoost Regressor, and a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network [21,22,24]. Each model is trained using raw ERA5_Ag precipitation values as inputs and observed stations data as the target output. The goal is to minimize prediction errors and effectively reduce bias in the gridded dataset. The best−performing model is then used to generate high−resolution, bias−corrected raster maps of monthly precipitation across the Tensift Basin, facilitating improved hydrological modeling, water budget analyses, and land surface monitoring. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to apply machine learning−based bias corrections on gridded rainfall data in the Tensift Basin. In support of open science and reproducibility, the full set of corrected raster maps produced in this research will be made freely available on GitHub, allowing other researchers and stakeholders to access and build upon the corrected data products. The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- To evaluate the magnitude and spatial distribution of bias in the ERA5_Ag rainfall dataset relative to in situ observations across the Tensift basin;

- To develop and assess the performance of five machine learning algorithms for bias correction using observed stations data;

- To compare these models based on predictive accuracy, robustness, and interpretability using multiple evaluation metrics;

- To generate spatially continuous, bias−corrected rainfall rasters using the best performing model for hydrological and environmental applications.

1.2. Related Work

Precipitation data are foundational to hydrological modeling, water resource planning, and climate impact assessments. However, in arid and semi−arid regions, such as the Tensift Basin in Morocco, the availability of reliable rainfall data is often limited by the limited spatial coverage of ground−based observation networks. As highlighted by Ref. [25], rain gauges, though regarded as the most accurate tools for measuring precipitation, effectively cover only about 1% of the Earth’s surface. This scarcity is even more pronounced in mountainous and developing regions, where the infrastructure required for dense monitoring networks is often lacking. These observational gaps have spurred the use of gridded precipitation products derived from satellite observations and climate reanalysis models, including ERA5, CHIRPS, CFSR, GPM, and PERSIANN−CDR [26,27,28,29,30], to fill spatial and temporal voids in climate data.

Despite their widespread coverage and operational advantages, such gridded datasets suffer from large biases due to multiple sources: errors in sensors, spatial smearing, assumptions of retrieving algorithms, and inability in observing localized or convective events, especially over complex topographies [31,32]. For instance, Ref. [33] provided the “MSWEP” dataset, merging gauge, satellite, and reanalysis products with a weighted ensemble method. Despite MSWEP exhibiting better performance over some products in hydrological applications, especially in poorly gauged basins, bias correction remains essential. Ref. [34] revealed that downscaled climate projections significantly varied in performance with respect to variations in correction and spatial resolutions, with implications on water resource assessments. Acknowledging the scale of this problem, an increasingly large set of the literature has examined statistical and machine learning−based bias corrections in order to further improve the accuracy of precipitation estimates. Ref. [35] examined a variety of correction used with regional climate model outputs, commenting that the method effectively minimized bias in means values but had variable performance in correcting variability and extremes. Quantile mapping, in particular, has appeared as a versatile method. Ref. [36], and once again in a related study (2020), used this approach with satellite−derived precipitation estimates (e.g., PERSIANN−CCS) in a variety of climatic regions in Iran, with notable gains in monthly and annual rainfall precision and bias minimizations as high as 98% in some regions.

Besides traditional methods, machine learning models have demonstrated significant potential in alleviating spatial and temporal biases in gridded datasets. In a comparative analysis of 13 models of bias correction models, Ref. [37] presented Random Forest−based corrections that were more effective than traditional methods in correcting CMIP6 rainfall and temperature projections over Nigeria. In a similar study, Ref. [38] used XGBoost to correct the underestimation of rainfall in high−altitude regions over the Tibetan Plateau, reducing errors by more than 50% while showing good transferability of the scheme across diverse terrains in Norway, including the U.S. Ref. [39] further provided evidence of the applicability of machine learning models in hydrology, showing the higher predictive accuracy of LSTM networks in simulating runoffs in ungauged basins than traditional hydrological models. For the Moroccan scenario, Ref. [40] conducted a comparative evaluation of five satellite and reanalysis products of precipitation products (CHIRPS, ERA5_Ag, CFSR, GPM, and PERSIANN−CDR) across the semi−arid Haouz region. The study revealed that while ERA5_Ag and GPM outperformed the other products, ERA5_Ag exhibited significant biases, especially at finer temporal resolutions. By applying quantile mapping corrections, substantial improvements in data quality were achieved, consequently enabling the corrected dataset to be applied in approximating 30−year trends in groundwater recharge, which is vital in sustainable water resource planning in response to climate change. Subsequently, Ref. [7] further elaborated on the application of integrated hydraulic and hydrological modeling in flood mitigation and in designing infrastructure using a case study of one such bridge across Oued Ourika. In this research work, it was demonstrated how corrected and high−resolution rainfalls data could be applied in enhancing engineering decision−making in floodplain management.

Subsequent research including Ref. [41] contrasted correction approaches with ERA5−Land across a range of time scales and verified that no one approach invariably outperforms others in all cases. Their findings reiterated that the choice of bias correction models needs to be specific to the variable (e.g., temperature or rain), temporal disaggregation, and geographical setting. In another seminal review, ref. [27] warned of excessive reliance on current correction because most of them assume that climate models already produce realistic change signals, which is not necessarily true in all cases. He argued that, in addition to more process−based correction models, stochastic methods need to be developed in order to enhance climate impact simulation fidelity. Overall, these studies highlight the need of using sound bias corrections in both satellite and rainfall reanalysis datasets, particularly in the hydrological modeling of semi−arid and data−starved regions. Inclusion of machine learning strategies, as seen in some of most recent research studies, has opened new ways of enhancing such corrections by identifying complex nonlinear relationships and accounting for spatial heterogeneity. This study builds upon previous work, and we push our research further using five machine learning models, Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, and MLP, to correct biases in ERA5_Ag precipitation data using ground−based observations of 20 gauged stations in the Tensift Basin. By correcting and spatializing 504 monthly rasters of the years 1981−2023, this study aims to generate a high−resolution, bias−reduced rainfall dataset that is usable in long−term hydrological modeling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

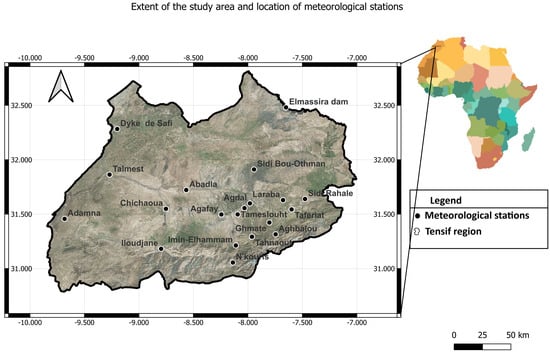

The Tensift Basin encircles the central–western area of Morocco and covers roughly 20,400 km2 in area. The basin extends longitudinally from the eastern edge of the Haouz Plain, and it is bordered to the south by the High Atlas Mountains and to the north by the Jbilet and Rehamna hills. The basin is drained by the river Oued Tensift, rising in the High Atlas and extending from the east to the west. The basin has a semi−arid to arid climate, with rainfall patterns that vary widely over time and across the basin. Most rainfall occurs during the winter and early spring, with annual rainfall ranging from over 800 mm in the mountains to less than 250 mm in the plains. Significant elevation ranges—from under 200 m up to more than 4000 m at Mount Toubkal—lead to big differences in results with respect to marked variations in climate, vegetation, and hydrological dynamics. Figure 1 presents the location of the study area and the meteorological stations.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the study area and the distribution of meteorological stations across the region.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

Table 1 presents the temporal distribution of samples at various meteorological stations. Long, uninterrupted time series are found for most of the stations, with records of data from January 1981 to December 2018 at most stations, amounting to 456 monthly records per station. These stations include Abadla, Adamna, Aghbalou, Chichaoua, Dyke−Safi, Elmassira−Dam, Iloudjane, Imine−Elhammam, Marrakesh, N’kouris, Sidi−Bou−Othman, Sidi−Rahal, Taferiat, Tahnaout, and Talmest. Conversely, other stations have more recent and shorter time series. Agafay has data from 2003 to 2023, consisting of 252 samples, while Agdal has records from 2005 to 2023, with 228 samples. Even shorter and more recent time series are available for Ghmate, Laraba, and Tameslouht. Ghmate has data from 2019 to 2023 with 50 records, Laraba has 83 samples from 2017 to 2023, and Tameslouht has records from 2018 to 2023, with 63 samples in total.

Table 1.

Temporal coverage and sample size for each rainfall station.

The ERA5_Ag dataset is a global reanalysis product developed by the European Centre for Medium−Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). It provides continuous and consistent meteorological data at a spatial resolution of approximately 9 km (0.08°) and a temporal resolution of hourly to daily intervals, covering the period from 1950 to the present. ERA5_Ag integrates a wide range of observations into a comprehensive atmospheric model, offering high−quality estimates of various climate and surface variables. This dataset is widely used in agricultural, hydrological, and climate−related studies due to its long−term coverage and global consistency. The data are freely accessible through the Copernicus Climate Data Store Ref. [26].

Key metrics for temperature, wind speed, and solar radiation relative to the weather stations derived from the ERA5_Ag dataset are presented in Table 2. In general, average temperatures range from 11.16 °C to 20.28 °C, with Laraba, Tameslouht, and Abadla being the warmest stations and Aghbalou, N’kouris, and Imine−Elhammam being the coldest. Minimum temperatures recorded at the stations range between −0.32 °C in Aghbalou and 10.29 °C in Laraba. Maximum temperatures range from 22.48 °C in N’Kouris to 32.29 °C in Laraba, indicating a wide temperature range among the different regions. With respect to wind speed, there were significant differences between the stations, with averages ranging from 1.45 m/s to 4.20 m/s. The highest average wind speeds were recorded at the Dyke−Safi, Adamna, and Elmassira−Dam stations, while the lowest speeds were recorded at Imine−Elhammam, Aghbalou, and Ghmate. The lowest wind speeds ranged from 1.15 m/s to 2.70 m/s, while the highest speed values are up to 6.16 m/s in Adamna and show that some stations experience more vigorous wind conditions.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of temperature, wind speeds, and radiation for each station.

In terms of solar radiation, average solar radiation values are relatively consistent across stations, ranging from 226.56 W/m2 to 238.36 W/m2. The highest average radiation value was recorded at Adamna, and the lowest was recorded at Ghmate. Minimum radiation values at the monthly scale range from 104.56 W/m2 to 132.80 W/m2, and the highest values are 345.62 W/m2 in Abadla, so in some stations, there are high peaks of solar radiation. In short, the stations exhibit significant variations in temperatures and wind speeds, with clear differences among the hottest, coldest, windiest, and calmest locations. While solar radiation shows limited variability overall, maximum values highlight seasonal peaks in certain regions.

Table 3 summarizes the long−term monthly mean precipitation (mm/month) computed for each rainfall station and the corresponding ERA5_Ag. These values represent the average of all months over the complete observation period (presented in the Table 1), providing an overview of the climatological monthly distribution of precipitation over the study area. Overall, the results highlight a clear seasonal contrast, with maximum rainfall occurring between November and March and minimum precipitation during the summer months (June–August), which is characteristic of the semi−arid Mediterranean climate prevailing in the Tensift Basin. Spatially, mountain stations such as Aghbalou, Imine−Elhammam, and Tahnaout record the highest monthly means, reflecting the strong influence of orographic uplifts and higher elevations on precipitation totals. Conversely, lowland and plain stations such as Abadla, Agafay, and Tameslouht exhibit markedly lower precipitation values, confirming the altitude−dependent gradients typical of the region.

Table 3.

Long−term monthly mean precipitation (mm/month) derived from station observations and ERA5_Ag reanalysis data for each rainfall station over the full study period.

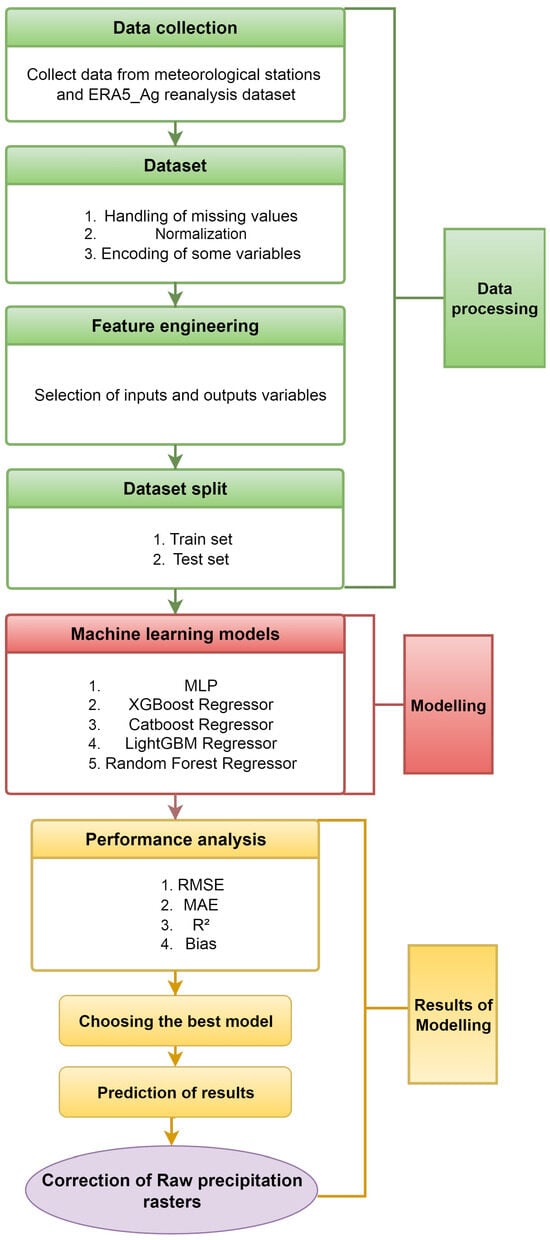

2.3. Methodology

The methodological process employed in this study was structured into a series of sequential steps to ensure the quality and stability of the results. The entire sequence of steps, ranging from data collection and preprocessing to model selection and final predictive model assessment, is covered by the designed process. Figure 2 schematically displays all methodological steps performed, offering a clear and well−organized visualization of the workflow followed throughout the study.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the methodology adopted in this study.

The first phase of this study consisted of the collection of meteorological data from both local meteorological stations and the ERA5_Ag reanalysis product. The ERA5_Ag dataset provides high−quality historical climate data with high spatial and temporal resolutions, and it is widely used in climate and agriculture research due to its spatial coverage, consistency, and reliability. Combining data from these two sources provides a richer and more comprehensive dataset, which is essential for developing more accurate predictive models. After data collection, the dataset was prepared by performing a series of preprocessing steps. First, missing values were addressed with appropriate methods, such as imputation using the mean or median or, when necessary, removal of incomplete records for data quality. After this, numerical features were normalized to ensure that all variables were on the same scale and that no feature dominated the modeling process due to its magnitude. To ensure consistent scaling of predictors across diverse climatic and geographic settings, all input features were normalized globally across all 20 meteorological stations. This involved computing the mean and standard deviation over the entire training dataset and applying the same transformation to all station data. A comparative test was also performed using a per−station normalization approach, where each station’s data was scaled independently using its own local statistics. The results from both strategies were nearly identical in terms of model performance metrics (RMSE, MAE, and R2), indicating that global normalization did not introduce bias or distort spatial variability due to station heterogeneity. Given its simplicity and suitability for extrapolation to ungauged areas, global normalization was retained in the final modeling pipeline. Finally, some categorical features were coded using techniques such as one−hot encoding so that they could be correctly interpreted by machine learning algorithms.

During the feature engineering stage, the most relevant variables for the prediction task were selected, which include the input variables (predictors) and output variables. In the characteristic engineering phase, the most relevant variables to the prediction problem at hand were selected. In this phase, the input variables (predictors) and the output variable (target) were carefully selected. This step helps reduce model complexity, improve performance, and focus the analysis on the variables with the greatest impact on the phenomenon under study. Subsequently, the dataset was divided into separate training and test subsets. The training set, which represented 80% of the overall data, was used to build and refine prediction models. The other 20% served as the test set, where the ultimate assessment of the model’s ability to generalize was conducted. The split is essential to ensure that the models can make accurate predictions, avoid overfitting, and provide an unbiased estimate of performance. To ensure the independence of the predictors used in the machine learning framework, we assessed multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). VIF quantifies how much the variance of a predictor is inflated due to its correlation with other predictors. The VIF is defined as follows:

where is the coefficient of determination obtained by regressing predictor i against all remaining predictors. A value of indicates no correlation with other predictors, values between 1 and 5 suggest moderate correlations that are generally acceptable, while values greater than 10 indicate severe multicollinearity and potential redundancy. This analysis was applied to four predictors: ERA5_Ag precipitation, temperature, radiation, and wind speed.

During the modeling phase, several regression algorithms known for their strong predictive performance were employed. The models utilized were as follows: Multi−Layer Perceptron (MLP), XGBoost Regressor, CatBoost Regressor, LightGBM Regressor, and Random Forest Regressor. We selected these machine learning models because they are widely used in precipitation bias corrections, regression tasks, and hydrological predictions, offering a balance between predictive accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency. Other algorithms such as Long Short−Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) were not retained due to data and computational constraints: LSTM requires much longer time series and larger datasets than those currently available from our ground stations, while SVM is computationally expensive and scales poorly with large sample sizes. Nonetheless, both approaches remain promising, and we note that they could be incorporated into future work if more extensive ground−based datasets become available, thereby enabling a broader evaluation of machine learning methods for precipitation bias correction.

A Multi−Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a feedforward neural network that has one or more hidden layers between inputs and outputs. It uses backpropagation to iteratively update weights and learn complex, nonlinear relationships in the data. Although capable and powerful, MLPs are data−scaling−sensitive, requiring careful tuning of the hyperparameters to prevent overfitting or underfitting [42,43,44,45].

XGBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm based on decision trees that is highly efficient in constructing models through iterative refinement, correcting residual errors at every iteration [42,46,47].

CatBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm developed to handle categorical features natively without extensive preprocessing. It avoids overfitting using permutation−driven statistics and employs symmetric tree structures that improve training stability. These features make CatBoost robust, easy to use, and effective in real−world datasets containing mixed data types [48].

LightGBM is a gradient boosting framework that enhances training efficiency by employing histogram−based feature binning and a leaf−wise tree growth strategy. This approach significantly improves computational speed and memory usage while often achieving higher accuracy than traditional level−wise methods. LightGBM is particularly well−suited for large datasets and time−constrained scenarios [49,50].

The Random Forest algorithm combines an ensemble of decision trees built on randomly sampled data and features, with high efficiency even on data with many variables. It is versatile and scalable and provides measures of the importance of variables [51,52].

To ensure model robustness and reduce overfitting risks, we employed a 5−fold cross−validation procedure during model evaluation. In each fold, the data were partitioned into training (80%) and validation (20%) subsets, and the model’s performance was assessed using RMSE and R2 metrics. This process was repeated across five iterations, and the results were averaged to estimate the generalization ability. The low variance across folds indicates model stability and minimal overfitting.

The performance accuracy of every model was assessed based on widely used statistical metrics: root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), the coefficient of determination (R2), and bias. They enabled quantitative assessments of the models’ accuracy of prediction, as well as the quality of fit of the data. In addition, a comparison of all models was conducted to determine the overall best−performing model.

Based on the performance assessment, the best−performing model was selected and used, with the aim of minimizing errors and maximizing explanatory power. This choice was made to ensure the uptake of a robust model with high predictability and good generalizability to new data. The results obtained from the selected model were presented and thoroughly discussed. This involved extensive discussions of the levels of errors attained, the accuracy of predictions, and the overall effectiveness of the model in addressing the problem under investigation. After selecting the optimum error model, a time series dataset and rasters were created with the predicted precipitation values.

3. Experimentation Settings

3.1. Hardware and Software Environment

All experiments were conducted in Kaggle’s cloud−based Jupyter notebook environment, which offers a highly reliable and scalable platform for deep learning and extensive analysis. We utilized the NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU with 16 GB of dedicated VRAM and 16 GB of system memory. GPU acceleration significantly reduces training time and enables the use of larger batch sizes and deeper model structures. The operating system underlying the environment is based on Linux, which provides a stable platform for scientific computing. The main programming language used in our experiments is Python (version 3.10), which is widely adopted in machine learning research due to its simplicity, flexibility, and rich ecosystem of scientific libraries.

A notable feature of the Kaggle environment is the ability to fix package versions to a specific environment snapshot, ensuring that library versions remain consistent across different runs. This capability enhances reproducibility and mitigates potential issues caused by version updates. Internet access was selectively enabled to allow the download of external resources, such as pre−trained models or additional datasets, when necessary. The combination of GPU−accelerated computing, a well-defined Python ecosystem, and reproducibility−focused configurations makes Kaggle an effective and robust environment for conducting our experimental evaluations.

3.2. Implementation Specifics

This subsection briefly describes the implementation configurations of each machine learning model, including architecture, hyperparameters, and training details. All models were tuned using a grid search strategy combined with 5−fold cross−validation applied to the training subset. The optimization objective was to minimize the mean root mean square error (RMSE) averaged across folds. The final configurations presented in Table 4 correspond to the best−performing parameter sets identified within each model’s defined search space. The hyperparameter search spaces explored for each algorithm are also presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of model architectures, training settings, and hyperparameter search spaces.

These ranges were selected based on established practices in precipitation modeling and previous studies [53,54,55], ensuring a compromise between computational cost and adequate exploration of plausible model configurations. The optimization metric was the mean RMSE computed on validation folds, while MAE and R2 served as complementary indicators to verify prediction robustness and generalization stability. A 5−fold cross−validation procedure was applied consistently for hyperparameter tuning and model performance assessment. Nested cross−validation (CV) was not applied, since the main goal of this study was to compare the performance of different machine learning models using the same data partitions rather than to perform exhaustive model selection. Nested CV, which involves separate loops for tuning and validation, greatly increases computational cost. By using identical 5−fold cross−validation splits for all models, the analysis ensured fair comparisons and computational efficiency, providing reliable benchmarking results without the extra complexity of nested cross−validation.

3.2.1. CatBoost

The CatBoost model was implemented as a gradient boosting regressor designed to efficiently handle both numerical and categorical data. It was configured with 1000 iterations and a learning rate of 0.01, which ensured gradual convergence and reduced the risk of overfitting. A maximum tree depth of 8 was selected to maintain a balance between expressiveness and generalizability. The training set consisted of 80% of the data, with 20% reserved for testing, using a fixed random seed (42) for reproducibility. Early stopping was employed to halt training if no improvement was observed, and model progress was tracked with verbose updates every 50 iterations. Default L2 regularization was used to further control overfitting. This configuration allowed CatBoost to effectively capture meteorological and spatiotemporal patterns while ensuring stable training and strong generalization.

3.2.2. LightGBM

The LightGBM model was implemented as a gradient boosting decision tree regressor (LGBMRegressor) with 800 boosting iterations and a learning rate of 0.01. A maximum tree depth of 12 was set to allow for sufficient feature interaction modeling while controlling overfitting. The ’month’ and ’year’ features were explicitly cast to categorical types to leverage LightGBM’s efficient categorical feature handling, whereas other variables, including spatial coordinates (X and Y), were treated as numerical inputs. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing, using a fixed random seed (42) to ensure reproducibility. Default L2 regularization was used, and verbose output was disabled to streamline training logs. LightGBM internally uses a leaf−wise tree growth strategy with gradient−based one−side sampling (GOSS) and exclusive feature bundling (EFB), enabling faster convergence and efficient computation.

3.2.3. MLP

The MLP model was implemented using PyTorch 2.9.0 and designed with three fully connected layers. The architecture included an input layer matching the number of features (9), followed by hidden layers with 128 and 64 neurons respectively, each followed by an ReLU activation function. The output layer consisted of a single neuron to produce a single continuous precipitation estimate. The model was trained using an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01, and the mean squared error (MSE) was used as the loss function. The training process was conducted over 200 epochs, with a batch size of 256 for training and 64 for testing to optimize computational costs while preserving stable convergence. Feature scaling was performed using standardization (StandardScaler), and categorical features such as month and year were treated as numerical values after scaling. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing, and a fixed random seed (42) was used to ensure reproducibility. This configuration allowed the MLP to learn complex nonlinear relationships between meteorological, temporal, and spatial features while maintaining training stability.

3.2.4. XGBoost

The XGBoost Regressor was implemented as a gradient boosting regressor with 500 boosting iterations, a learning rate of 0.01, and a maximum tree depth of 6, allowing the model to capture complex nonlinear interactions among features. The model used the histogram−based tree construction method (tree_method=’hist’) to accelerate training, with an option to switch to gpu_hist if GPU resources were available. The dataset was standardized using a StandardScaler to improve convergence stability. The training data consisted of 80% of the samples, with 20% held out for testing, using a fixed random seed (42) to ensure reproducibility. Early stopping was enabled with a patience of 100 rounds, and verbose logs were provided every 100 iterations to monitor progress. The optimizer used internally in XGBoost is based on gradient boosting optimization over decision trees, including regularization techniques to prevent overfitting. This configuration allowed XGBoost to effectively leverage meteorological, spatial, and temporal features to improve precipitation predictions.

3.2.5. Random Forest (RF)

The Random Forest model was implemented using the Random Forest Regressor from scikit−learn, using 250 trees and a fixed random seed (42) to ensure reproducibility. No maximum depth was explicitly set, allowing trees to grow until all leaf nodes became pure or the minimum sample split threshold was reached. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Feature scaling was not necessary due to the tree−based nature of the model. The input features included meteorological variables (temperature, wind speed, radiation, and ERA5_Ag precipitation), spatial coordinates (X and Y), and temporal indicators (month and year). This configuration enabled Random Forest to capture complex interactions and nonlinear relationships across features while maintaining robustness and interpretability.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of our models, we used three widely adopted error−based metrics: root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (). These metrics collectively offer a comprehensive assessment of model accuracy and generalization performance.

3.3.1. Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

RMSE quantifies the average magnitude of the error by taking the square root of the mean of squared differences between predicted and actual values:

where is the actual value, is the predicted value, and n is the total number of samples. RMSE penalizes larger errors more heavily, making it particularly useful for detecting significant deviations in precipitation prediction.

3.3.2. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

MAE represents the average of the absolute differences between predicted and actual values:

where , , and n are as defined above. Unlike RMSE, MAE treats all errors equally and provides a more direct interpretation of average prediction accuracy.

3.3.3. Coefficient of Determination ()

measures the proportion of variance in the observed data that is explained by the predictions:

where is the actual value, is the predicted value, is the mean of the actual values, and n is the total number of samples. An value close to 1 indicates strong explanatory power of the model.

4. Results

This section presents the evaluation results of all models evaluated across 20 meteorological stations, followed by a detailed analysis of one selected model to illustrate its predictive behavior. To ensure a comprehensive evaluation of predictive accuracy and the robustness of each approach, we highlight key metrics and provide insights into model performance and error characteristics. Furthermore, we examined the potential multicollinearity among the predictors (ERA5_Ag precipitation, temperature, radiation, and wind speed) using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The results indicated very low VIF values, ranging from 1.14 for wind speed to 1.41 for radiation, with ERA5_Ag precipitation and temperature showing values of 1.17 and 1.39, respectively. These consistently low values confirm the absence of problematic multicollinearity, ensuring that each predictor provides independent information to the models.

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Models

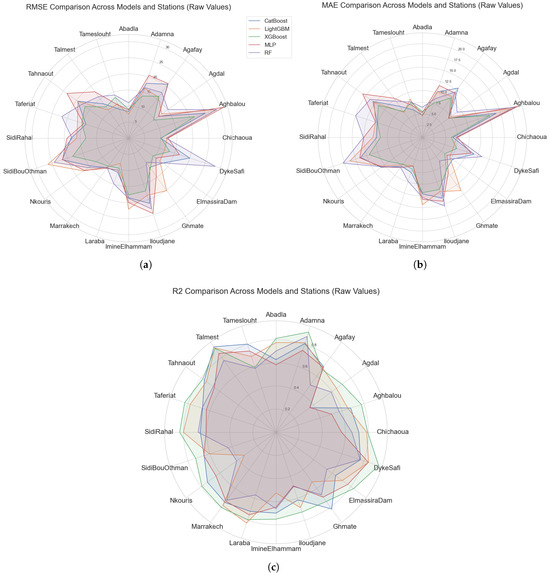

In this subsection, we conduct a detailed comparative analysis of five machine learning algorithms, CatBoost, LightGBM, XGBoost, Multi−Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Random Forest (RF), applied to precipitation estimation across 20 meteorological stations. The comparative evaluation is structured into two main analyses: first, an assessment of predictive accuracy using performance metrics (RMSE, MAE, and the coefficient of determination, ), and second, an evaluation of systematic prediction biases across all stations.

Figure 3 summarizes the predictive performance of each model across 20 meteorological stations using three metrics: RMSE, MAE, and .

Figure 3.

Evaluation of machine learning models for precipitation bias correction across stations using multiple performance metrics. (a) Root mean square error (RMSE) comparison across models and stations. (b) Mean absolute error (MAE) comparison across models and stations. (c) Coefficient of determination (R2) comparison across models and stations.

RMSE and MAE measure predictive accuracy, with lower values indicating better performance, while reflects the model’s explanatory power, with values closer to 1 suggesting a stronger fit to the observed data. An analysis of these metrics across individual stations reveals that no single model consistently outperforms others across all stations and criteria. XGBoost demonstrates particularly competitive performance, especially in stations like Adamna, where it achieves the lowest RMSE (13.78), lowest MAE (7.66), and the highest value (0.91), indicating excellent predictive power. XGBoost also performs strongly at Elmassira−Dam and Talmest, where it consistently ranks among the top in terms of accuracy. LightGBM also shows robust performance across multiple stations. For instance, it achieved an RMSE of 11.0389 and of 0.78 with respect to Marrakech and performed competitively for Adamna ( = 0.81) and Chichaoua ( = 0.78). However, its performance varies depending on the complexity of the station’s data. In some areas like Ghmate or Aghbalou, the RMSE is relatively higher, suggesting a potential sensitivity to spatial or temporal data heterogeneity.

CatBoost, while somewhat more stable across various environments, often lags behind other boosting algorithms in terms of absolute error metrics. Nevertheless, it maintains decent performance in stations such as Abadla and Agdal, and it provides a strong balance between bias and variance without major outliers. Its values are generally acceptable but not leading in any station. The MLP model exhibits inconsistent performance. While it performs adequately in more stable stations like Marrakech or Tameslouht, it struggles significantly in more complex regions such as Aghbalou ( = 0.50) and Iloudjane ( = 0.48). The relatively higher RMSE and MAE values across multiple stations suggest that MLP, despite its ability to model nonlinear patterns, may require more careful regularization or feature engineering to generalize well across spatially distributed datasets. Random Forest, by contrast, demonstrates moderate performance across all evaluated metrics. It rarely ranks first in terms of predictive accuracy but maintains relatively consistent performance. For example, it achieves a competitive of 0.87 in Adamna and reasonable RMSE values in stations like Sidi−Rahal and Taferiat. However, at stations like Agdal and Agafay, its performance declines relative to that of boosting models. This suggests that while Random Forest is robust and less prone to overfitting, its predictive capacity may be slightly limited in highly variable environments.

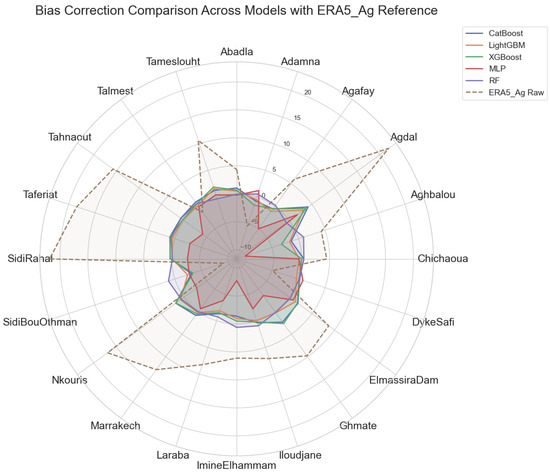

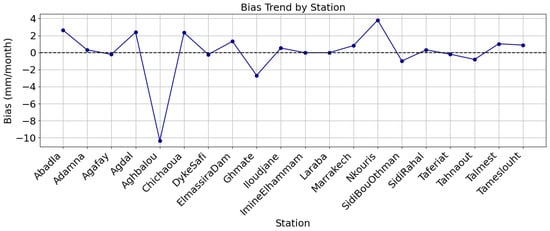

To complement the previous evaluation and support more informed model selection, we additionally investigate the presence of systematic prediction biases, which are not captured by RMSE, MAE, or alone. Turning to systematic prediction errors, Figure 4 presents the bias values associated with each model across the 20 stations. Bias quantifies a model’s systematic tendency to consistently overestimate or underestimate observed values. Ideally, bias should be minimal and close to zero, reflecting balanced and unbiased predictions. Here, Random Forest clearly demonstrates outstanding performance with consistently low absolute bias values across virtually all stations. Notable examples include Abadla (bias = −0.073), Dyke−Safi (bias = 0.13), and Marrakech (bias = 0.045), each reflecting minimal systematic deviations. By contrast, other models frequently exhibit larger bias magnitudes, which are indicative of more substantial systematic errors in their predictions. For instance, MLP at Aghbalou exhibits a large negative bias of approximately −10.03, indicating significant systematic underestimation.

Figure 4.

Bias comparison per station and model.

Combining the insights from both the predictive accuracy metrics (RMSE, MAE, and ) and the bias analysis, we observe that Random Forest demonstrates robust, consistent performance across most stations in terms of bias. While it may not always achieve the highest predictive accuracy (see Figure 3), it excels at minimizing systematic over− or under−prediction. This balance of accuracy and low bias makes it a strong candidate for operational precipitation corrections.

Given these findings, the next subsection will delve deeper into the Random Forest model’s results, utilizing visual analyses and additional evaluations to better understand its predictive behavior and performance characteristics.

4.2. Detailed Analysis of the Correction Model Performance

Based on the comparative analysis, the Random Forest (RF) model was identified as the most effective method for precipitation correction across all stations. Its superior performance is evidenced by consistently low error metrics and minimal bias compared to other machine learning models. In this subsection, we provide an in−depth discussion of the RF model through a set of visual analyses, highlighting its predictive power, feature relevance, and error distribution.

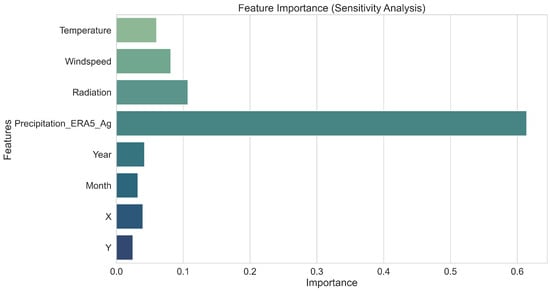

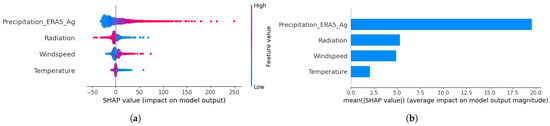

We begin this detailed exploration with a feature importance (sensitivity analysis) plot, which quantifies the contribution of each input variable to the model’s predictions. As illustrated in Figure 5, the most influential feature by far is the aggregated precipitation from ERA5 (Precipitation_ERA5_Ag), which holds a dominant importance score exceeding 0.6. This finding confirms the crucial role of ERA5_Ag precipitation estimates in driving the correction process.

Figure 5.

Feature importance (sensitivity analysis) derived from the Random Forest model for precipitation correction.

Other meteorological variables, such as radiation, wind speed, and temperature, also demonstrate significant importance, indicating that these factors provide valuable complementary information in refining precipitation estimates. Although their individual contributions are lower, their inclusion helps the model adjust for local climatic variability and improve accuracy. Temporal variables (month and year) and spatial coordinates (X and Y) exhibit smaller but notable importance scores, suggesting that temporal patterns and spatial positioning play supporting roles in capturing seasonal effects and regional disparities. This sensitivity analysis underscores the robustness of the RF model’s feature utilization strategy and highlights the necessity of integrating diverse predictors to achieve accurate and reliable precipitation corrections.

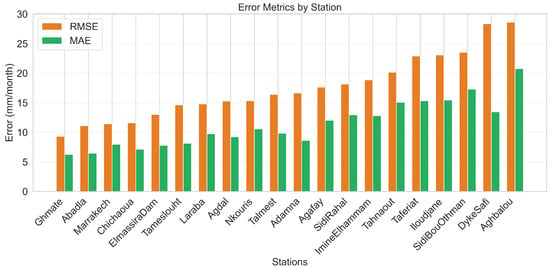

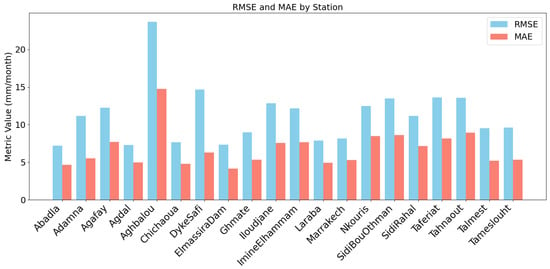

Following the analysis of feature importance, we further assess the performance of the Random Forest model through the evaluation of station−wise error metrics, as illustrated in Figure 6. This figure presents a comparative visualization of RMSE and MAE values across all stations, allowing us to understand how the model performs spatially.

Figure 6.

Station−wise mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) distribution for the Random Forest model.

The figure reveals that stations such as Ghmate, Abadla, and Marrakech exhibit the lowest RMSE and MAE values, indicating highly accurate predictions in these regions. This suggests that the RF model captures local precipitation patterns effectively in these locations, potentially due to more homogeneous climatic conditions or better representativeness of the input features. In contrast, higher error values are observed at stations like Aghbalou and Dyke−Safi, possibly due to complex terrain influences, localized micro−climates, or data scarcity, which make generalization more challenging. Nevertheless, their performance remains acceptable, demonstrating the robustness of the RF model across various contexts. The consistent trends between RMSE and MAE across stations suggest that the model does not suffer from extreme outlier predictions in most cases, reinforcing its stability and reliability.

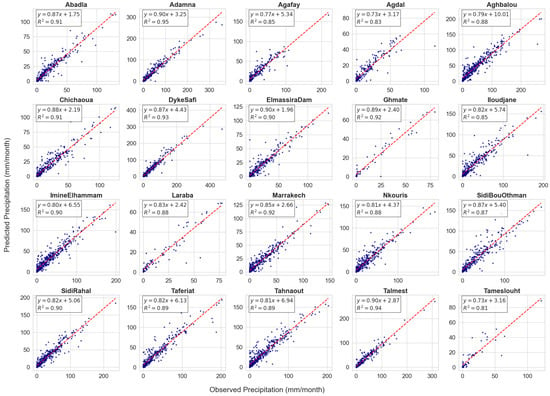

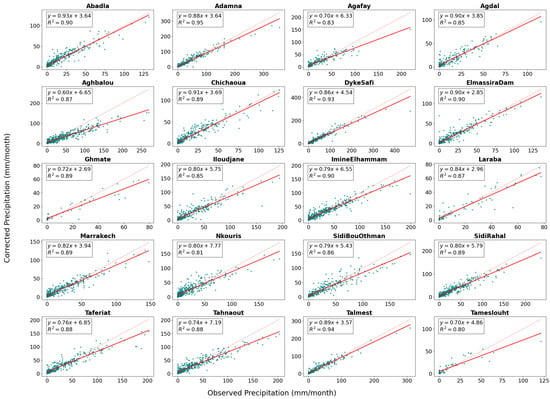

We then examine the scatter plots of observed versus predicted precipitation at each station, as shown in Figure 7. These plots provide a direct visual evaluation of the RF model’s predictive accuracy and its ability to replicate the observed precipitation patterns.

Figure 7.

Scatter plots of observed versus predicted precipitation for each station using the Random Forest model.

The scatter plots show that, across most stations, predicted values align closely with the 1:1 reference line (in red), indicating strong agreement between predicted and observed data. High values, such as those observed at Adamna (), Talmest (), and Dyke−Safi (), highlight the excellent predictive capacity of the RF model at these sites. At other stations, like Agafay () and Iloudjane (), slightly lower values point to some challenges, possibly linked to localized variability or less representative input data. Nevertheless, the linear trends remain strong and predictions largely follow the reference line. The tight clustering of points along the diagonal across most stations indicates minimal systematic biases and a limited presence of extreme over− or underestimation, supporting the reliability of the RF model for operational use. These scatter plots complement numerical error metrics and feature importance analyses, providing an intuitive, station−level visual validation.

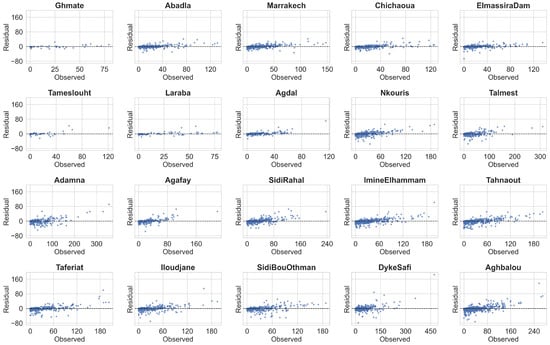

To further evaluate the Random Forest model’s predictive behavior, we examine the residual plots for each station presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Residual plots (predicted−observed) as a function of observed precipitation for each station using the Random Forest model.

Figure 8 displays the distribution of residuals (differences between predicted and observed values) plotted against the observed precipitation for all stations. These plots provide critical insights into the error structure and highlight potential biases or heteroscedasticity in model predictions. A general observation across most stations is that residuals are symmetrically distributed around the zero line (dashed black line), indicating no significant systematic overestimation or underestimation trends. This balanced residual pattern confirms the model’s ability to provide unbiased corrections, aligning with the previously reported low bias values.

Stations such as Ghmate, Abadla, and Marrakech exhibit narrow residual spreads, suggesting that the RF model captures precipitation variability effectively in these locations with minimal few large errors, reinforcing the conclusions drawn from both error metrics and scatter plot analyses. Conversely, a wider dispersion of residuals is observed in stations like Aghbalou and Dyke−Safi, particularly at higher precipitation values. This pattern suggests potential challenges for the RF model in accurately estimating extreme precipitation events in these areas, likely due to complex terrain effects or sparse high−intensity rainfall data. The lack of clear funnel−shaped patterns in most residual plots indicates limited heteroscedasticity (i.e., increasing error variance with increasing observed values), further supporting the model’s stability across different precipitation magnitudes. These findings strengthen the evidence for the robustness and reliability of the Random Forest model, confirming its capability to deliver accurate precipitation corrections while maintaining minimal systematic error structures across diverse geographic contexts.

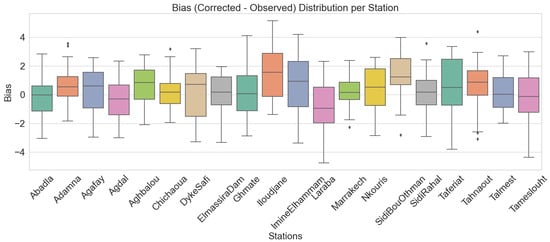

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of bias (corrected minus observed precipitation) for each station using the RF model. The median biases for most stations are very close to zero, indicating minimal systematic error and supporting findings from previous scatter and residual analyses. This indicates that, on average, the RF model neither consistently overestimates nor underestimates precipitation at most locations. Stations such as Ghmate, Abadla, and Marrakech show particularly tight interquartile ranges, reflecting both low bias and low variability, which indicates high model reliability.

Figure 9.

Distribution of bias (corrected−observed) across stations using the Random Forest model.

In contrast, stations like Aghbalou, Sidi−Bou−Othman, and Talmest exhibit slightly wider spreads, suggesting larger variations possibly linked to microclimatic effects, terrain heterogeneity, or data limitations affecting model calibration. Some stations also display outliers, indicating occasional large errors; however, these outliers do not substantially affect the central tendency, as shown by the stable median lines. This analysis reinforces the suitability of the RF model for operational precipitation corrections across varied environments and highlights its ability to maintain low median bias and moderate variability even under challenging local conditions.

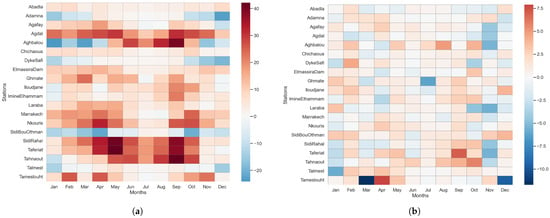

In addition, Figure 10 shows the spatial and temporal variability of the mean monthly precipitation bias by station and month (mm/month), computed over the full observation period. By analyzing the heatmap of the bias between uncorrected ERA5_Ag and the gauged stations datasets, ERA5_Ag exhibits a clear pattern of systematic overestimation across most stations and months, represented by the dominance of warm (red) tones. The overestimation is particularly evident during the spring months (March–May) and, to a lesser extent, in autumn (September–October), when convective and orographic rainfall events are more frequent. These systematic positive biases suggest that ERA5_Ag may overrepresent the intensity or frequency of precipitation during transitional seasons. Conversely, underestimation (blue zones) occurs sporadically at several stations such as Adamna, Dyke−Safi, Sidi−Bou−Othman, and Talmest, mainly in winter (December–February) and late autumn, indicating that ERA5_Ag struggles to capture localized rainfall events during these months.

Figure 10.

Heatmap illustrating the long−term mean monthly bias (ERA5_Ag−Station) across all rainfall stations, averaged over the complete study period. Red shades indicate ERA5_Ag overestimation, while blue shades represent underestimation. (a) Bias between uncorrected ERA5_Ag dataset and gauged stations. (b) Bias between Random Forest−corrected dataset and gauged stations.

Spatially, mountain stations show stronger positive biases, consistent with the difficulty of coarse reanalysis grids in reproducing orographic enhancement over complex terrain. In contrast, lowland stations exhibit smaller or mixed biases. In general, this pattern demonstrates that ERA5_Ag overestimation is both station−dependent and season−dependent, emphasizing the necessity of bias correction before any direct use of this dataset.

After bias correction, the heatmap of the Random Forest−corrected dataset shows a substantial reduction in bias amplitude compared to the uncorrected ERA5_Ag data (a), with most values clustering near zero (light tones). The remaining biases are small in magnitude and vary primarily with station and month, without a consistent seasonal trend. Small positive biases appear intermittently during spring (March–May) and early autumn (September) at stations such as Aghbalou, Tameslouht, and Taferiat, while slight underestimations (blue) occur sporadically in winter months (December–February) at Talmest and Sidi−Rahal. These localized differences likely reflect the micro−climatic effects and nonlinear rainfall variability not fully captured by the model.

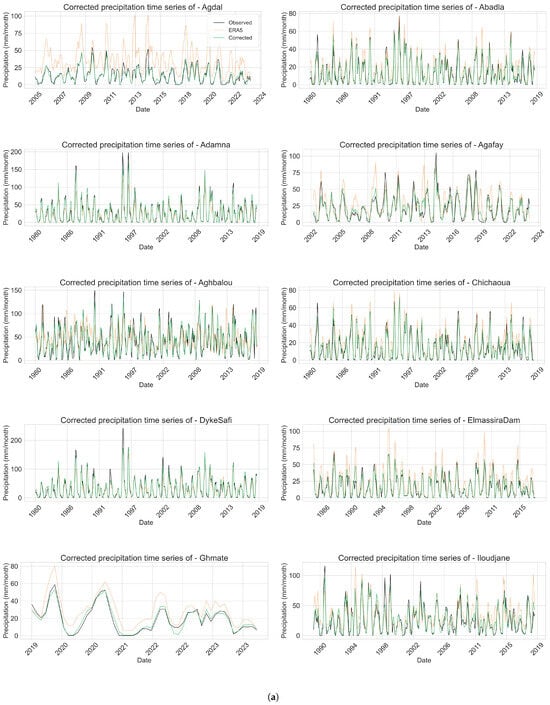

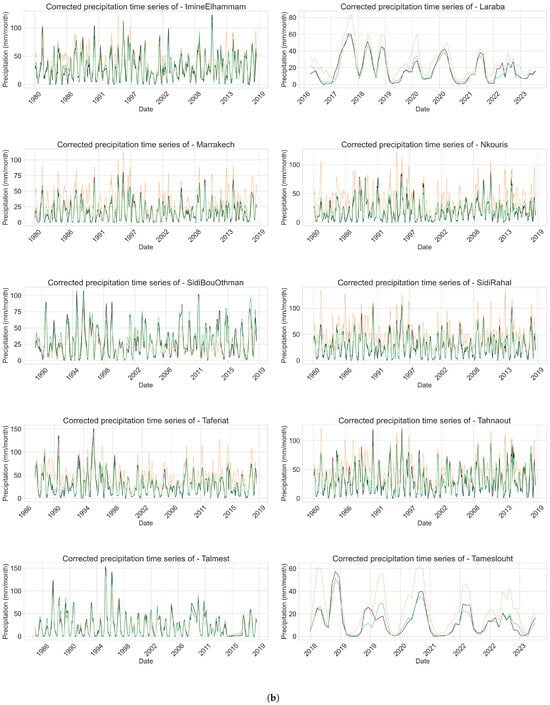

Figure 11 illustrates the monthly precipitation time series for each station, illustrating the observed data, the raw ERA5_Ag estimates, and the corrected outputs generated by the Random Forest model. These plots provide a temporal perspective on the model’s performance, highlighting its capability to align corrected precipitation estimates closely with ground observations across different climatic and geographic contexts. For most stations, the corrected series (green line) tracks the observed measurements (black line) remarkably well, effectively reducing the bias and overestimations commonly observed in the ERA5_Ag data (orange line). Stations such as Abadla, Adamna, and Marrakech demonstrate particularly strong alignment, indicating the RF model’s ability to capture both seasonal peaks and inter−annual variability.

Figure 11.

Corrected precipitation time series: comparison between observed, ERA5_Ag, and corrected values using Random Forest model. (a) First set of stations. (b) Second set of stations.

At more complex stations like Dyke−Safi, Agdal, and Aghbalou, where ERA5_Ag initially shows substantial deviations, the corrected outputs still significantly improve alignment with observations, although slight discrepancies during extreme events remain visible. This suggests that while the model performs robustly, localized microclimatic or terrain−related effects may present additional challenges.

For certain stations (e.g., Ghmate, Tameslouht, Laraba), the RF correction effectively smooths fluctuations and reduces exaggerated peaks, resulting in a time series that better captures the timing and magnitude of precipitation events. This indicates a strong capacity of the RF model to generalize corrections over diverse precipitation regimes, even when data gaps or local heterogeneity exist.

These time series plots highlight the temporal reliability of the RF approach, complementing the earlier cross−sectional analyses. By clearly demonstrating the reduction in biases and enhancement of overall pattern fidelity, this visualization reaffirms the RF model’s practical applicability for long−term precipitation correction and monitoring in operational hydrological and agricultural contexts.

To further assess the generalization ability of the Random Forest (RF) model and ensure it was not overfitting the training data, a 5−fold cross−validation procedure was applied using the full dataset of corrected precipitation and ERA5_Ag−based predictors. This approach consists of randomly dividing the dataset into five equal subsets (folds). At each iteration, four folds are used for training, while the remaining fold is reserved for testing. This process is repeated five times so that each fold serves once as a test set, and the performance metrics obtained from the five iterations are then averaged. Such a strategy reduces the dependency on a single train/test split and ensures that all data are used for both training and validation. In this study, The RF model achieved an average Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 20.87 mm, with a low standard deviation of ±0.37 mm across the five folds. This consistency in error values reflects a high degree of model stability. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (R2) averaged 0.64, with a standard deviation of only ±0.03, indicating that the model consistently explained a substantial portion of the variance in observed precipitation across different subsets of the data. The narrow range of R2 scores (from 0.61 to 0.70) also suggests minimal sensitivity to how the data were split, reinforcing the reliability of the model in capturing key predictive relationships. These results support the conclusion that the RF model generalizes well and is not merely memorizing patterns specific to the training set, thereby addressing potential concerns regarding overfitting.

To deepen the understanding of why the Random Forest (RF) model outperformed others, we conducted a SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) analysis to interpret feature contributions. The SHAP summary plot in Figure 12 reveals that the ERA5_Ag precipitation input was the most influential variable in predicting corrected precipitation values. Radiation and wind speed also contributed meaningfully, while temperature had minimal impact. This is confirmed in the SHAP bar plot in Figure 12, where the average absolute SHAP value of ERA5_Ag far exceeds that of other variables. These insights not only justify the strong performance of RF but also highlight the physical relevance of the predictors used.

Figure 12.

Feature contribution analysis using SHAP for the Random Forest model. (a) SHAP summary plot. (b) SHAP bar plot.

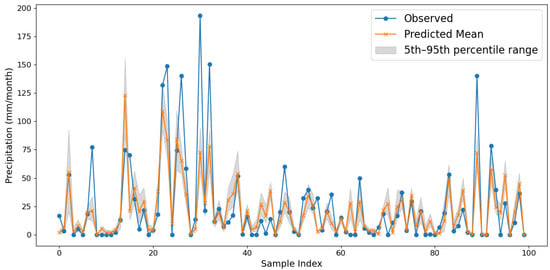

Uncertainty in the corrected precipitation estimates was assessed using a bootstrap-based approach. Fifty resampled subsets of the training data were generated, and a separate Random Forest model was trained on each subset. All confidence intervals represent the 5th–95th percentile range derived from 50 bootstrap resamples. As illustrated in Figure 13, the predicted means closely follow the observed precipitation values, and the majority of observations fall within the estimated confidence bounds.

Figure 13.

Comparison between observed and predicted precipitation with 5th–95th percentile confidence intervals.

In summary, the comprehensive set of analyses, including feature importance, station−wise error metrics, scatter plots, residual distributions, bias boxplots, and temporal time series evaluations, collectively demonstrate the strong performance and reliability of the Random Forest model. By effectively integrating multiple meteorological and spatiotemporal predictors, the RF model consistently delivers accurate precipitation corrections across diverse stations and conditions.

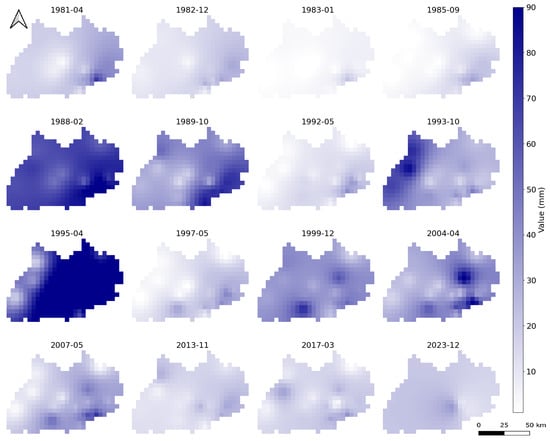

4.3. Bias Correction and Quality Assessment of Precipitation Rasters

Using the trained machine learning model, we generated a set of bias−corrected raster datasets derived from the ERA5_Ag precipitation product. The correction model was trained using data from 20 rain gauge stations, allowing for improved spatial adjustments of the original ERA5_Ag rasters. During training, we included the geographical coordinates of each station, enabling the model to learn the spatial variability of precipitation relative to location. This approach is particularly effective, as the raster datasets are structured as simple matrices defined by geographic coordinates and a single precipitation variable, making them suitable for correction by the model.

The stations are distributed across the Tensift Basin, and the corrected rasters were generated over the full spatial extent of this basin. The training period spans 42 years, resulting in a total of 504 monthly precipitation rasters. To evaluate the effectiveness of the correction process, we extracted precipitation values at the pixel locations corresponding to the station coordinates. These evaluations were conducted using all rasters from the full temporal span. The results demonstrate strong consistency between corrected values and observed data. Due to space limitations, we will present a set of representative corrected rasters, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Random set of monthly corrected rasters.

Figure 15 presents scatter plots comparing monthly precipitation values from the bias−corrected ERA5_Ag rasters to observed data from 20 gauging stations across the Tensift Basin. Each subplot includes a red dashed 1:1 reference line, allowing visual assessments of prediction accuracy. The corrected values exhibit a strong correlation with ground observations, with coefficients of determination (R2) ranging from 0.80 (Tameslouht) to 0.95 (Adamna). Over 70% of stations reported R2 values above 0.88, indicating excellent model performance in capturing local rainfall variability. These results confirm the robustness of the bias correction approach in reproducing spatial rainfall patterns closely aligned with in situ data. The minimal dispersion around the 1:1 line in most plots highlights the model’s capacity to correct for both magnitude and timing of rainfall events.

Figure 15.

Scatter plots of observed and ERA5_Ag precipitation from corrected rasters.

The mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) between ground−based observations and corrected raster precipitation estimates are shown in Figure 16. MAE values range from 4.5 mm to 14.7 mm, while RMSE values range from 7.1 mm (Abadla) to 23.4 mm (Aghbalou). A comparatively low prediction error is indicated by the mean MAE of 7.3 mm and the average RMSE of roughly 11.9 mm for all stations. Large outliers were uncommon and error distributions were balanced according to the small discrepancies between RMSE and MAE for all stations. Many stations show consistently low errors, demonstrating the model’s ability to generalize effectively across the region, even though some sites, such Aghbalou and Dyke−Safi, have slightly greater errors.

Figure 16.

Station−wise comparison of mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) between observed precipitation and corrected ERA5_Ag raster estimates.

The bias (mean error) between station observations and the corrected rasters values is shown in Figure 17. The average bias for all stations is approximately +0.4 mm, with bias values ranging from −10.3 mm (Chichaoua) to +3.9 mm (Nkouris). The model does not consistently overestimate or underestimate precipitation, as this near−zero mean bias attests. However, 17 out of 20 stations have absolute bias values less than 3 mm, indicating unbiased corrective performance and good spatial coherence. The correction model effectively represents local weather conditions while minimizing systematic errors, as evidenced by the low distribution of residual bias values. These findings support the suitability of the corrected ERA5_Ag rasters as reliable precipitation inputs for upcoming groundwater and hydrological modeling projects.

Figure 17.

Spatial distribution of the bias between ground−based precipitation observations and corrected ERA5_Ag raster estimates.

The analysis of the results clearly highlights the importance of correcting raw gridded data. This need extends beyond precipitation to all climate variables derived from satellite and reanalysis datasets products. The applied correction significantly improves the alignment of raster−based precipitation estimates with actual ground measurements, making them much more reliable. As a result, these corrected datasets can be confidently used in various calculations and models where precipitation serves as a critical input.

5. Discussion

Bias correction is a key part of obtaining reliable data for hydrological and climatic applications. Traditional statistics methods are largely employed, but they often fail to identify the nonlinearity and heterogeneity of climate variables, particularly in regions with high precipitation variability and topographically complex areas. In this context, machine learning (ML) models seem a powerful approach that offers more flexibility and accuracy. Recent research has demonstrated the effectiveness of ML models in bias correction. As shown in Ref. [56], Random Forests are superior to classical methods for correcting snow water equivalent in the cold environments of high latitudes. This is particularly relevant, as snow−dominated systems require methods capable of capturing seasonal dynamics and complex feedbacks, which Random Forests can manage effectively. Similarly, Ref. [57] applied ML−based bias correction on a global scale within the “E3SM” climate model, showing that ML techniques such as gradient boosting can correct biases while preserving the physical coherence of climate variables like humidity and wind.

In our study of the Tensift Basin, we found strong similarities with these results. Random Forest (RF) stood out in our model comparison not because it always achieved the highest R2, but because it maintained low bias and stable performance across various stations, including those with challenging climatic conditions such as Aghbalou or Dyke−Safi. This consistency reinforces the idea, also noted by Ref. [56], that RF is well suited for applications requiring both reliability and generalization. It is worth noting that no similar study has been conducted in our study area, making this research the first of its kind in the Tensift Basin. It is important to highlight that the results should be close to the real data—this requirement was emphasized by Ref. [57] and we have clearly fulfilled this requirement in our results. Our research indicates that models incorporating multiple environmental predictors, such as temperature, radiation, wind speed, and spatial coordinates, produce more reliable results. This multifactorial approach helped ML models capture the underlying climate structure rather than merely overfitting to precipitation values alone. Our analysis also confirms the findings of Ref. [58], which showed that ML models outperform the traditional quantile method for precipitation correction during monsoon periods in South Korea. Finally, the strong predictive accuracy of XGBoost in our study—particularly at climatically simpler stations like Adamna and Elmassira−Dam—aligns with broader findings regarding the model’s strength in handling nonlinearities and interactions, as illustrated by Ref. [59] in their hydrological modeling for the Third Pole region.

We adopted RF to generate the time series for the stations and to correct bias in the rasters. The XGBoost and LightGBM models both achieved the best overall precision, with lower RMSE and MAE and higher R2 values at most stations. These models captured the variability of precipitation patterns effectively, particularly at stations with complex precipitation patterns. It may seem contradictory that the chosen model showed lower results; however, when focusing on bias reduction, the Random Forest (RF) model consistently outperformed all others. Despite slightly lower precision metrics, RF yielded bias values closest to zero in the majority of stations, indicating better corrections of systematic overestimation or underestimation inherent in ERA5_Ag data. In contrast, models such as XGBoost and CatBoost tended to overestimate precipitation, particularly in high−rainfall areas, as evidenced by their generally positive bias. These results suggest that model selection for bias correction should not rely solely on accuracy indicators. Since the ultimate goal is to produce precipitation estimates that are both realistic and free of systematic error, Random Forest emerges as the most appropriate model for correcting ERA5_Ag bias, despite its moderate RMSE and R2 values. Its strong performance in minimizing bias makes it particularly suitable for hydrological modeling applications that require unbiased precipitation inputs, such as aquifer recharge estimation or water balance studies in semi−arid regions like the Tensift Basin.

This work is a continuation of the Ref. [40] study, which addressed the selection of the most suitable precipitation product for acquiring rainfall data in the Haouz area of the Tensift Basin. That study concluded that ERA5_Ag showed good results but was biased; its strength lies particularly in effectively capturing precipitation variability, despite a tendency to overestimate rainfall. The author attempted to reduce this bias using the statistical quantile mapping method, which yielded relevant results. However, this method has limitations: Notably, it does not spatialize the variable. Machine learning (ML) models, on the other hand, naturally allow for easy spatialization of precipitation because they are trained using the longitude and latitude coordinates of each station. Consequently, corrected data derived from ML models also depend on these geographical coordinates, enabling accurate spatial representations.

The bias correction of precipitation directly influences several hydrological variables, including infiltration (I), evapotranspiration (ET), and surface runoff (R). In our area of interest, however, there is a notable lack of comprehensive water balance modeling. To date, no regional water balance model has been developed that captures the spatial and temporal evolution of inflows and outflows across the Tensift Basin. This absence limits our understanding of how precipitation variability translates into changes in groundwater recharge and surface water availability. Given that the basin is characterized by strong climatic contrasts and limited hydrometeorological monitoring, improving rainfall accuracy through bias correction represents a critical first step toward establishing a reliable water balance framework.

In future work, the hydrological validation will focus on the establishment of a rainfall–runoff model for the five principal catchments that feed the Tensift River, which constitutes the main surface watercourse of the Tensift Basin. The selected catchments are N’fis, Rhiraya, Ourika, Zat, and Ghdat, each of which is monitored through long−term river discharge observations. Using these ground observations, rainfall–runoff models such as SWAT Ref. [60] or HEC−HMS Ref. [61] will be applied to simulate 42 years of runoff dynamics, thereby reconstructing the historical hydrological behavior of the basin. These runoff estimates define one of the boundary conditions of our area of interest, as the generated flows from the mountain catchments contribute to the recharge of the Haouz aquifer through infiltration along the riverbeds. This step will therefore enable the quantification of historical runoff and infiltration fluxes, which are not directly measured by monitoring stations. In parallel, by combining the bias−corrected precipitation rasters with existing evapotranspiration and runoff datasets, the water balance of the Haouz Plain will be calculated to determine the portion of rainfall contributing to diffuse groundwater recharge. The aquifer concerned is unconfined, and infiltration will be estimated through a simple water balance equation linking precipitation (P), evapotranspiration, and runoff components (P−I−ET−R = 0). These variables constitute essential inputs for the development of a MODFLOW groundwater flow model. It is important to emphasize that all these processes are strongly interconnected: the accuracy of precipitation data directly determines the reliability of the resulting hydrological and hydrogeological simulations. The corrected rasters will be made available online following the publication of this article (https://github.com/AC-hydrogeology/Bias-correction-of-precipitation-rasters.git, accessed on 20 October 2025).

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the strong potential of machine learning (ML) models in enhancing the accuracy of ERA5_Ag precipitation estimates using long−term observations from 20 meteorological stations in the Tensift Basin, Morocco. Among the five tested models—MLP, XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest—the Random Forest model proved particularly effective in reducing systematic bias and was therefore used to produce corrected precipitation rasters over a 42−year period. These bias−corrected datasets offer a valuable input for hydrological applications such as aquifer recharge and water balance modeling. Despite the encouraging results, several limitations should be acknowledged. Deep learning models like LSTM were not used due to insufficient temporal depth in the available station records, and the spatial coverage of stations remains moderate. Notably, observational data are lacking in the High Atlas Mountains, where complex orographic effects influence precipitation patterns. Consequently, some residual errors persist in these high−relief regions. Additionally, while ML models performed well across much of the basin, their ability to fully capture precipitation variability in mountainous terrains remains a challenge. Future work will address these limitations by expanding dataset and station coverage and by integrating the corrected precipitation into a comprehensive water balance model for the Haouz plain—a key sub-region of the Tensift basin. This next step will focus on quantifying groundwater recharge and modeling the dynamics of water tables under climate change scenarios. By connecting precipitation corrections with hydrological modeling, this research pathway will further support sustainable water resource planning in semi−arid environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., N.-E.L. and H.I.; methodology, A.C., S.A. and J.C.A.R.; software, A.C., S.A. and J.C.A.R.; validation, N.-E.L., H.I., L.Z. and E.Z.; formal analysis, A.C. and S.A.; investigation, A.C.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., S.A. and J.C.A.R.; writing—review and editing, N.-E.L., H.I. and E.Z.; visualization, A.C. and S.A.; supervision, N.-E.L. and E.Z.; project administration, H.I. and N.-E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

After the publication, all corrected rasters will be available online on the GitHub platform of the principal author via the following link: https://github.com/AC-hydrogeology/Bias-correction-of-precipitation-rasters.git, (accessed on 20 October 2025). Data can also be requested via email to the first author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to the international project “Earth Observation for Early Warning of Land Degradation” (EWALD) for its valuable support and collaboration. Our gratitude also goes to the I-Maroc project (“Artificial Intelligence/Applied Mathematics, Health/Environment: Simulation for Decision Support”), which is part of the RD MULTITHÉMATIQUE—APRD2020 program and funded by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (DESRS) and the OCP Foundation (FOCP), for their technical support. Finally, we acknowledge the important contribution of the Regional Office for Agricultural Development of Draa (ORMVAD) for their ongoing assistance and cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbaspour, K.C.; Yang, J.; Maximov, I.; Siber, R.; Bogner, K.; Mieleitner, J.; Zobrist, J.; Srinivasan, R. Modelling hydrology and water quality in the pre-alpine/alpine Thur watershed using SWAT. J. Hydrol. 2007, 333, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouziyne, Y.; Abouabdillah, A.; Bouabid, R.; Benaabidate, L. SWAT streamflow modeling for hydrological components’ understanding within an agro-sylvo-pastoral watershed in Morocco. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2018, 9, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guug, S.S.; Abdul-Ganiyu, S.; Kasei, R.A. Application of SWAT hydrological model for assessing water availability at the Sherigu catchment of Ghana and Southern Burkina Faso. HydroResearch 2020, 3, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, P.C.; Salhi, A. Long-term hydroclimatic projections and climate change scenarios at regional scale in Morocco. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driouech, F.; Stafi, H.; Khouakhi, A.; Moutia, S.; Badi, W.; ElRhaz, K.; Chehbouni, A. Recent observed country-wide climate trends in Morocco. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, E855–E874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakri, A.; Laftouhi, N.-E.; Ibnoussina, M.; Mandi, L. Contribution of hydraulic modeling and hydrology to flood prevention and design of engineering structures: Case study of a bridge over the Oued Ourika–Morocco. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 489, 04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bouazzaoui, I.; Ait Brahim, Y.; Amazirh, A.; Bougadir, B. Projections of future droughts in Morocco: Key insights from bias-corrected Med-CORDEX simulations in the Haouz region. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]