Featured Application

This review provided a comprehensive synthesis of volatile organic compound (VOC) sources, exposure levels, and health impacts in hospital environments in Thailand and other countries. The findings serve as a foundational reference for hospital administrators, public health policymakers, and environmental staff to design and implement standardized indoor air quality monitoring systems. The recommended practices can be directly applied to occupational safety, staff and patient well-being, as well as addressing infrastructure and regulatory challenges.

Abstract

Indoor air pollution has become a significant concern, contributing to the decline in air quality through the presence of gaseous pollutants and particulate matter, especially under poor ventilation. Hospitals, functioning as non-industrial microenvironments, particularly in Thailand, face challenges due to insufficient and incomplete databases for effective air quality management. Within these environments, patients with heightened sensitivity, along with hospital staff who are predominantly exposed indoors, face increased risk of exposure to indoor air pollutants. This study aimed to review current evidence on VOCs in hospital settings in Thailand, identifying their sources, concentrations, and health impacts. It also aimed to provide recommendations for improved air quality monitoring and management. The review included studies published between 2008 and 2023 in English or Thai. Studies were selected based on relevance to VOCs in hospital environments, while excluding those lacking sufficient data or methodological rigor. Literature searches were conducted using Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and PubMed. Results from international studies were also considered to address gaps. Data extraction focused on VOC sources, concentrations, measurement methods, and associated health impacts. Results were synthesized into six thematic categories: characterization, health effects, control measures, etiological studies, monitoring systems, and comparative studies. The review identified 87 relevant studies. VOC exposure was associated with several adverse health impacts resulting from short- and long-term exposures, leading to an increased risk of cancer. Identified sources of VOC emissions within hospitals encompass anesthetic gases, sterilization processes, pharmaceuticals, laboratory chemicals, patient care, and household products, as well as building materials and furnishings. Commonly encountered VOCs include alcohols (e.g., ethanol, 2-methyl-2-propanol, isopropanol), ether, isoflurane, nitrous oxide, sevoflurane, chlorine, formaldehyde, aromatic hydrocarbons, limonene, and glutaraldehyde, among those commonly detected in hospital environments. Yet, limited knowledge exists regarding their source contributions, emissions, and concentrations associated with health impacts in Thai hospitals.

1. Introduction

Indoor air pollution is an emerging and significant health concern [1]. Modern individuals spend over 90% of their time indoors, especially within occupational environments. Studies on human behavior reveal that most individuals spend more time indoors —both in residential and workplace settings—than in outdoor activities [2,3]. Accordingly, personal exposure is primarily attributable to various indoor air pollutant concentrations rather than the outdoor environment. Nevertheless, the quality of the indoor environment is usually neglected, particularly in hospitals, where occupants are often unaware of exposure to chemical hazards [4]. Hospitals, in particular, tend to accommodate a high density of patients, visitors, and staff.

Previous research has examined several parameters of indoor air pollution (IAP) in hospitals, including thermal comfort parameters (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, and air movement), particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), and total bacterial and fungal levels. By contrast, studies remain limited in their comprehensive examination of individual volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or total VOC (TVOC) within hospitals as non-industrial microenvironments in Thailand, primarily due to constraints related to research budget, technical expertise, and measurement equipment [2,5]. This gap is striking given that VOCs are a major class of pollutants with known health effects and are highly relevant to hospital environments, where disinfectants, cleaning agents, pharmaceuticals, and building materials are in constant use [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Nevertheless, numerous studies have reported on VOCs in hospitals from 31 different countries, including Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America. Additionally, many studies investigated other indoor pollutants in hospitals, particularly in Thailand, Iran, and Italy [14,15,16,17,18,19]. These studies revealed substantial variability in VOC levels depending on hospital function, ventilation system, and product use [9,20]. By comparison, reviews focusing specifically on hospital settings remain scarce, leaving policymakers and practitioners with limited consolidated knowledge.

VOCs represent a category of chemicals capable of evaporating at room temperature, exhibiting vapor pressures of ≥0.01 kPa at 20 °C [21]. They are commonly found in various environments, including industrial facilities, residential homes, and urban areas [22]. Importantly, VOCs can exert toxicological effects even at concentrations below odor thresholds. Several compounds—such as benzene, toluene, and formaldehyde—are classified as carcinogenic or neurotoxic [23]. VOC exposure has been implicated in Sick Building Syndrome (SBS), manifesting as headache, fatigue, and irritation of the upper respiratory tract, nose, throat, eyes, hands, and/or facial skin [24,25], and has also been consistently associated with an elevated risk of asthma in children and rhinitis in adults [26,27].

In hospitals, VOCs are present in many common materials, including household products, building materials, pharmaceuticals, laboratory reagents, patient care products, cigarette smoke, pesticides, and a range of healthcare-related activities. VOC concentrations in hospitals have been reported to range from <55 mg/m3 (room average) to approximately 4900 mg/m3 for ethanol and 4600 mg/m3 for isopropanol among staff. Although these concentrations were below OSHA/ACGIH occupational limits, in some cases they exceeded indoor air quality guidelines (e.g., Japan: toluene 260 mg/m3 vs. measured >1000 mg/m3). By contrast, residential levels ranged 14 to 2274 μg/m3, with several households surpassing U.S. EPA cancer risk benchmarks [12,27,28,29]. In the hospital environment, the widespread use of hand sanitizers has been shown to contribute substantially to increased indoor VOC concentration, particularly ethanol and propanol (e.g., 2-methyl-2-propanol) [9].

The biological mechanisms underlying these health impacts involve oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and mucosal irritation induced by VOC inhalation [30]. For example, aldehydes such as formaldehyde can form protein and DNA adducts, contributing to carcinogenesis, whereas aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzene can disrupt hematopoiesis [31,32]. Short-chain alcohols such as ethanol and isopropanol may impair mucociliary clearance and alter respiratory immune defense [33]. In healthcare workers, repeated exposure to mixed VOCs has the potential to result in cumulative neurological and respiratory effects [13], while vulnerable patients may experience aggravated disease outcomes due to compromised immunity [34]. Despite these risks, a comprehensive understanding of VOC exposure levels and associated mechanisms in hospital environments remains limited [13,30].

According to the Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health of Thailand [35], standards are specified for thermal comfort (temperature 24–26 °C, relative humidity 50–65%, air movement < 0.3 m/s) and air contaminants (CO2 ≤ 1000 ppm, TVOC ≤ 1000 ppb, formaldehyde (HCHO) ≤ 0.08 ppm or ≤100 µg/m3, etc.). However, the notification does not specific threshold values for other VOCs that are particularly relevant in hospital settings, which limits its applicability in protecting healthcare workers and patients.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to review the current evidence in Thailand and other countries regarding the sources, types, impact, and measurement of indoor VOCs in hospital settings. Additionally, it aims to provide practical recommendations for improving the routine measurement of VOCs in hospitals, developing mitigation plans to reduce their health impacts, and assisting policymakers, researchers, and environmental officers in establishing new standard values for specific VOCs using appropriate equipment in the future.

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The literature review was carried out using the keywords “VOCs”, “Indoor air”, and “hospital” in Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, and PubMed. We focused on published papers and gray literature (unpublished studies) in Thai and English, including reports, peer-reviewed journals, and conference proceedings related to indoor air pollution of VOCs and their sources in hospitals in Thailand, and relevant regulations and notifications. More precisely, the following MeSH terms were used to search the PubMed database for studies published between 2008 and 2023, to encompass as much research conducted in Thailand as possible, given the limitations on the number of published works: “indoor air” AND “VOCs” OR “volatile organic compounds” OR “TVOC” AND “concentration” OR “level” OR “emission” AND “hospital” OR “healthcare” AND “Thailand”. Accordingly, this review was expanded to include international evidence, rather than exclusively focusing on Thailand. Subsequently, our efforts aimed to identify comprehensive studies on VOCs and other indoor pollutants in hospitals as documented in international publications. The search results were screened by title and abstract and included studies that met our inclusion criteria: keywords, key findings, and methodologies. For exclusion criteria, articles not available in Thai or English were excluded. Studies published before 2008 were excluded to ensure the inclusion of recent and relevant information, as shown in Table 1. Additionally, studies with insufficient data or lacking key findings and methodologies pertinent to VOCs and indoor air quality in hospitals were excluded. Duplicate publications were also excluded to avoid redundancy. Our findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The review protocol was not registered in PROSPERO or other registries, and a formal risk of bias assessment was not conducted, which is acknowledged as a limitation of this review.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

2.2. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Analysis

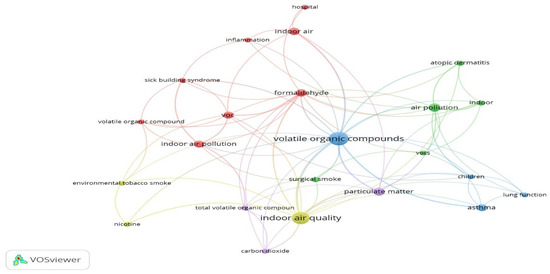

Search results were screened based on titles and abstracts for relevance. Eligible studies underwent full-text review. Data were extracted using a structured data extraction form. This form captured information on study design and location, VOC characteristics (e.g., types, sources, and concentrations, measurement and monitoring methods, health impacts, and mitigation strategies. The extracted data were compiled into Excel files to facilitate analysis and ensure consistency in data organization. The data analysis process for this study consisted of two main components: thematic classification and keyword co-occurrence analysis using VOSviewer version 1.6.20. The process of thematic classification of the reviewed studies and documents involved identifying recurring patterns and key topics. The information was then organized into six main categories. This classification framework was specifically designed to align with the objectives of this study and was informed by the patterns observed in previous research on VOCs in hospitals, both domestically and internationally. To explore the relationships between key topics in the reviewed studies, VOSviewer software was used to create a visual map of co-occurring keywords as shown in Figure 1. A minimum threshold of four co-occurrences was set to define the boundaries and include keywords that appeared together at least four times across the studies. The review process was conducted by a single reviewer, who performed all searches, screenings, and data extractions. Collaborative feedback was sought from co-authors during analysis and manuscript preparation.

Figure 1.

VOSviewer network of 4 co-occurrences for author keywords.

3. Results

Surprisingly, we found a restricted number of published studies on the subject, with only about six publications in Thailand. Moreover, a total of 175, 107, and 140 relevant results from different countries were obtained from Science Direct, Scopus, and PubMed, respectively. These results were then exported to Excel files and extracted using a structured data extraction form.

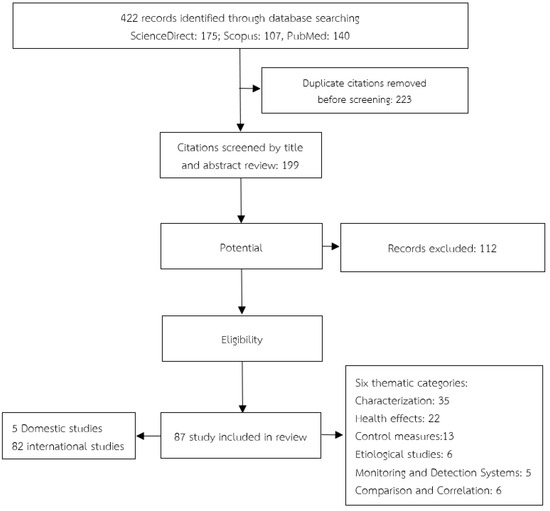

3.1. Overall Results for Indoor VOCs in Hospital Setting

In total, approximately 199 distinct articles were identified. Following the review of the titles and abstracts, 112 articles were deemed ineligible for inclusion because they did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Therefore, the remaining 87 articles (including 5 Thai articles) were included in this review of indoor VOCs in hospitals (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of study selection.

We compiled Supplementary Material SA, which systematically summarizes 87 studies from 31 countries: Asia (14 countries)—Bangladesh [36], China [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], India [49,50], Iran [51,52,53], Iraq [54,55], Japan [56], Lebanon [57], Malaysia [58,59], Qatar [60], South Korea [6,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], Taiwan [10,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75], Saudi Arabia [76], Mongolia [77] and Thailand [2,5,78,79,80]; Europe (14 countries)—England [13], Finland [11,81], France [9,20,47,82,83], Greece [84,85,86], Italy [87,88,89,90], Netherlands [91], Norway [92], Portugal [93,94], Romania [95], Slovakia [96], Spain [88,97], Sweden [98], Germany [7] and Switzerland [99,100,101]; Africa (1 country)—Nigeria [102]; Europe/Asia (1 country)—Turkey [103,104]; North America (1 country)—the United States [28,105,106,107,108,109,110]. A total of 32 VOCs were reported across the reviewed studies, and were categorized into two groups: carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic. The 13 carcinogenic substances are tetrachloroethylene (perchloroethylene), 1,4-dichlorobenzene (para-dichlorobenzene), benzene, formaldehyde, chloroform, methylene chloride, styrene, 1,3-butadiene, furfural, 1-bromopropane, chlorobenzene, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, and trichloroethylene. The 19 non-carcinogenic substances are 2-propanol (isopropyl alcohol), 2-methyl-2-propanol, ethanol, ketones (acetone, 2-butanone (methyl ethyl ketone; MEK), ethers (diethyl ether), naphthalene, toluene, xylene (ortho-, meta-, para- isomers), aliphatic hydrocarbons (n-nonane, n-decane, n-undecane, decane, octane), ethylbenzene, ethanol, isopropanol, acetaldehyde, limonene, hexane, alpha-pinene trimethylbenzene (TMB), 1-propanol (n-propyl alcohol), ethyl chloride (chloroethane), and methyl methacrylate. Short-term exposure to indoor VOC can result in immediate health effects such as eye, nose, and throat irritation, headaches, dizziness, nausea, and fatigue. These symptoms typically diminish once exposure ceases. Long-term exposure to VOCs may lead to more severe health consequences, including liver and kidney damage, as well as adverse effects on the central nervous system. Some VOCs are known or suspected carcinogens, heightening the risk of cancer over time. Moreover, chronic exposure to certain VOCs can exacerbate respiratory issues and contribute to conditions such as asthma. Supplemental information providing additional details is available in Table A1.

3.2. Indoor VOCs in Hospital in Thailand

The five studies and a notification in this analysis were published between 2008 and 2023 and were conducted in Thailand, highlighting the limited number of publications in this field, as shown in Table 2 and Table A2. Table 2 specifically summarizes only Thai research findings. This clear synthesis emphasizes that, despite existing efforts, systematic evidence for VOC exposure in Thai hospitals remains fragmented and insufficient for policy translation. According to Table 2 and Table A2, the characterization of VOCs in Thai hospital indoor air remains limited due to the absence of comprehensive assessments. VOC concentrations are influenced by healthcare activities, equipment, and building construction. Compared to other countries, VOC quantification in Thai hospitals lags behind, impeding IAQ management.

Table 2.

Summary of Thai research on indoor VOC air pollution in hospitals.

A concise explanation of Table 2 highlights the following: (i) VOC concentrations varied widely depending on the functional space, with pharmacy areas recording the highest TVOC levels (up to 796.77 ppb); (ii) only one study reported solvent-related exposures during hospital renovations, with average TVOCs of 9.5 ppm; (iii) formaldehyde was consistently detected in aged or poorly ventilated buildings, directly associated with respiratory sick building syndrome; (iv) certain studies reported non-detectable levels for TVOCs and formaldehyde, potentially reflecting methodological limitations rather than the absence of pollutants. Collectively, these findings point to heterogeneous monitoring practices and inconsistent application of international standards.

Ekpanyaskul (2010) [2] investigated unintentional solvent exposure from the renovation site among university hospital staff with an unknown etiology. The investigation involved measuring TVOCs in their working environments, revealing an average TVOC concentration of 9.5 ppm. However, this monitoring device does not provide the total weight average of toluene which might be underestimated. During the incidents, symptoms, and levels of hippuric acid were significantly higher than those observed after the issues were resolved. Consequently, the solvent emerged as a potential source of health hazards for hospital staff.

Tungjai & Kubaha (2017) [80] conducted an investigation assessing indoor air quality within single-patient rooms of government hospitals with 250 beds or more, encompassing a total of 11 hospitals situated in the northeastern region of Thailand. The results showed that the indoor VOC concentration did not exceed the standard (<3 ppm) based on the Guideline for good indoor air quality in office premises, with the average at 0.4 ppm, which was attributed to room cleaning immediately prior to measurement. On the other hand, CO2 concentration exceeded the standard due to high relative humidity and low velocity in isolation room.

Lasomsri et al. (2018) [78] developed a low-cost air quality monitoring device that integrated BME680 and CCS811 sensors. The device continuously measured and recorded TVOC, temperature, and humidity, enabling comprehensive air quality monitoring in waiting area, emergency room, and outpatient pharmacy. The standard level of concern for TVOC is based on Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the World Health Organization (WHO). The device was deployed in three key service areas of a large-scale hospital in Thailand—the waiting area, emergency room, and outpatient pharmacy. The obtained indoor air quality (IAQ) readings from the device indicated a very poor level. In addition, TVOC was significantly high in all areas, in particular in the pharmacy area.

Surawattanasakul et al. (2022) [5] conducted a cross-sectional study investigating (1) the prevalence of respiratory symptoms and skin Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) and (2) their associations with IAQ among office workers in administrative offices within an academic medical institute. The study utilized a self-reporting questionnaire to assess worker characteristics, working conditions, and perceptions of their working environments. Out of 290 office workers, 261 (90%) from 25 offices in 11 buildings participated in the survey. Elevated indoor formaldehyde (HCHO) and CO2 levels were associated with upper respiratory SBS. The high formaldehyde levels were attributed to aged offices, inadequate ventilation, and the use of formaldehyde-emitting materials. The building’s age, electronic equipment, and various consumer items were identified as common sources of indoor formaldehyde. Moreover, the new building was found to contain excessive concentrations of TVOCs [111].

Thongsumrit et al. (2023) [79] conducted a study on indoor air quality in Sub-district Health Promoting Hospitals (HP) and Early Childhood Development Centers (ED), and 11 parameters were employed to assess indoor air quality. The study revealed that concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 in all buildings surpassed indoor air quality standards. Furthermore, levels of CO2, total bacteria, and total fungi exceeded recommended thresholds. Conversely, values for TVOCs, ozone (O3), and HCHO were not detected (ND). The Hazard Index (HI) indicated that the exposure of children to indoor air pollutants exceeded the recommended limits for human health.

Thailand indoor air quality standards for public buildings were formalized by the Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health of Thailand through the Notification of the Department of Health regarding Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Standards in Public Buildings B.E. 2565 (2022) [35], issued on 21 November 2022. The notification provides a guideline for indoor air quality management in public buildings, including hospitals, for monitoring purposes. Current practices entail conducting a preliminary assessment using a Real-time photoionization detector or similar methods. For confirmation analysis, if measured values exceed acceptable limits, a comprehensive examination is recommended, employing Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) in accordance with ISO 16000-6:2011 or EPA Air Method, Toxic Organics-15 (TO-15), or equivalent protocols [35]. However, most VOCs lack specific surveillance and standard values, with only formaldehyde and TVOCs having established acceptable values.

Additional research using advanced instruments like GC-MS is necessary for precise VOC characterization and risk assessment. Standardized guidelines are needed to address VOC emissions in hospitals, emphasizing evidence-based approaches for further investigation and eco-friendly enhancements. In Thailand, TVOC is predominantly measured concurrently with other pollutants, while only a limited number of studies have measured formaldehyde (HCHO). However, there is a notable absence of data regarding the concentrations of individual VOCs, such as, alcohols (e.g., 2-methyl-2-propanol), benzene, toluene, xylene, ethyl-1-hexanol, aliphatic hydrocarbons, and acetone in different areas of hospitals, particularly within enclosed and confined spaces in hospitals, such as operating rooms (e.g., pathology laboratories, post-anesthesia units), nurse stations, clinics, clinic waiting areas, lobbies, meeting rooms, and wards. This deficiency impedes evidence-based initiatives aimed at enhancing indoor air quality in hospital settings.

From a policy perspective, the results summarized provide critical direction for the implementation of Thailand’s “Notification of the Department of Health regarding Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Standards in Public Building B.E. 2565 (2022)” [35]. Specifically, hospitals should: (i) strengthen real-time monitoring with confirmatory GC/MS analysis for VOCs exceeding preliminary thresholds, (ii) prioritize monitoring of high-risk hospital units such as pharmacies, waiting areas, and operating rooms, (iii) integrate VOC risk management within the Ministry’s Smart Energy and Climate Action (SECA) policy and Green & Clean Hospital initiative for eco-friendly building enhancements, and (iv) align hospital IAQ programs with SDG, which calls for reducing deaths and illnesses from air pollution. Hospitals should be vigilant about these potential sources and adopt measures to minimize indoor air pollution, including VOCs, enhancing ventilation, and implement effective indoor air quality management to safeguard the health and well-being of patients, staff, and visitors, contributing to overall building occupant health. Thus, there is a need for more studies on indoor VOC in Thai hospitals.

4. Discussion

It is imperative to seek corroborative evidence for indoor VOCs in hospitals from different countries, as shown in Table 2 and Table A2, as well as Supplementary Material SA, which synthesizes prior Thai studies. Supplementary Material SA summarizes 87 studies on hospital VOCs, enabling a structured cross-country comparison of sources, concentrations, health impacts, and regulatory frameworks. Notably, studies conducted in other countries employ diverse methodologies, including spatial aspects, use of specific equipment, and targeted investigation of pollutants.

For surgical procedures, in South Korea [6,64,67], Iran [53], and China [48], elevated BTEX levels were consistently detected in operating rooms due to surgical smoke, with estimated lifetime cancer risks from benzene exposure exceeding USEPA and Chinese thresholds. Choi et al. (2014) [6] aimed to address the issue of VOCs generated during surgical procedures, which are known carcinogens. A prototype multi-layered complex filter was tested during transperitoneal laparoscopic nephrectomy surgeries for renal cell carcinoma. Smoke samples were collected before and after filtration using a gas-sampling bag and analyzed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Results showed an 86.49% elimination rate of VOCs, significantly reducing occupational cancer risks associated with compounds such as benzene, ethylbenzene, and styrene. The study suggests that utilizing such filters can substantially mitigate health risks for operating room personnel exposed to surgical smoke. For neonatal care, in Germany, Wolf et al. (2020) [7] conducted in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) for premature neonates. Concentrations of VOCs were analyzed by real-time devices and reported inside the incubator after hand disinfection with an alcohol-based disinfectant solution. They found alcohol-based VOC spikes inside incubators following hand disinfection, raising concerns for premature infants. Higher VOC exposure during pregnancy has been associated with lower birth weights and worse neurocognitive outcomes in children. Increased prenatal VOC exposure resulting from renovation work has also been correlated with respiratory symptoms in children during the first 12 months of life. In the NICU study, VOC concentrations showed significant daytime-dependent fluctuations with the highest values around noon. VOC concentrations visibly increased at the beginning of each shift, which is when medical procedures and cleaning are mainly performed. For building-related emissions, in Finland, Rautiainen et al. (2019) [11] conducted to identify the causes of symptoms through the MM40 survey and house inspection methods. The study encompassed 14 different wards, 49 operating rooms, patient rooms, offices, policlinics, and pathology laboratories, involving 470 employees. A total of 61 materials and 49 indoor air samples were collected. The most frequently identified compounds in the material samples were 2-ethyl-1-hexanol and aliphatic hydrocarbons, as well as siloxanes in air samples. Elevated VOC emissions were observed in some material samples, likely contributing to the symptoms reported by workers in certain rooms. Furthermore, indoor VOC concentrations were strongly associated with ongoing healthcare activities within the hospital. Chinese [37,39,41,42,43,44,47,48] and Bangladeshi [36] studies identified construction and renovation activities (e.g., finishing paints) as major contributors to elevated TVOC and specific aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene and xylenes. For pharmaceutical and disinfectant use, European studies (Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, UK, Finland) [9,11,13,20,83,88,93,112] frequently observed peaks of alcohols (ethanol, isopropanol, 2-propanol), anesthetic gases, and siloxanes, with hospital activities and seasonality significantly influencing VOC concentrations. Importantly, many of these international investigations employed advanced instrumentation (thermal desorption GC-MS, TD-GC×GC-FID/MS, HPLC with DNPH derivatization) and reported compound-specific concentrations against established benchmarks (WHO, USEPA, ASHRAE, national IAQ standards).

Lü et al. (2010) [47] assessed the occurrence of carbonyl compounds and BTEXs (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes) in both indoor and outdoor air of a Guangzhou hospital. Sampling across diverse functional spaces—including pharmacy, traditional medicine preparation, supply/disinfection rooms, laundry, and garbage areas—revealed that acetaldehyde was the most abundant carbonyl, while toluene dominated the BTEX group. Indoor–outdoor concentration ratios remained close to unity, underscoring the significant role of ambient infiltration in shaping hospital indoor VOC burdens. Nevertheless, the authors also highlighted indoor emission sources, such as solvents, tobacco smoke, varnishes, and decoration materials, consistent with findings by Rautiainen et al. (2019) [11], who documented the strong influence of building decorations and construction materials on TVOCs and formaldehyde emissions. These findings support evidence that construction materials and healthcare activities can significantly elevate hospital VOC levels [113]. Expanding on this, Luo et al. (2011) [8] detected over 100 VOCs with mean concentrations ranging from 123.64 to 713.22 µg/m3. Toluene and xylenes (aromatics) and ethylene (alkene) were among the most abundant, with several waiting areas exceeding China’s 2003 indoor limits for toluene and xylenes. Benzene, n-hexane, and toluene exhibited strong indoor–outdoor correlations, whereas n-nonane, decane, undecane, m/p-xylene, and tetrachloroethylene were 3–4 times higher indoors, pointing to substantial contributions from building materials and cleaning products. Aromatics, alkanes, and alkenes constituted the major components, accounting for 61–98% of the total contents. Consistent with these findings, Bessonneau et al. (2013) [9] reported marked site-to-site variability in a French hospital, with mixtures spanning aromatic/halogenated hydrocarbons, aldehydes/ketones, siloxanes, anesthetic gases, esters, terpenes, and ubiquitous alcohols from disinfection. Ethanol and isopropanol are often used as sterilants in cotton balls; similar domination by alcohols and silicon-based VOCs was shown in Hyttinen et al. (2021) in Finland [12]. They found that the main emitted compounds in samples from 47 hospital rooms (two service, five meeting, 12 treatment, and 28 reception rooms) were alcohols (ethanol, 2-methyl-2-propanol, benzyl alcohol, isopropyl alcohol), xylenes, d-limonene, and silicon compounds (decamethylcyclopentasiloxane). Alcohols used in disinfectants and organic silicon compounds originating from occupants are the most common VOCs in operation rooms and offices. Palmisani et al. (2021) in Italy and Spain [88] utilized low-cost sensors to continuously monitor IAQ, focusing on TVOCs, fine particulate matter (PM2.5), and carbon dioxide (CO2) in two European hospitals at thoracic oncology ward, one in Italy and the other in Spain. Their findings demonstrated a weekday pattern in the temporal profiles of TVOCs, PM2.5, and CO2, showing concentration peaks during daytime hours, which align with increased human activity in oncology wards due to scheduled chemotherapy treatments. Factors such as human occupancy, pharmaceutical usage, and the application of disinfectants and cleaning agents were identified as primary influencers of TVOCs and PM2.5 levels in these settings.

In Taiwan, Jung et al. (2015) [10] investigated the distribution of indoor air pollutants across different areas of hospitals (nurse stations, pharmacy departments, clinics, clinic waiting areas, lobbies, meeting rooms, and wards), exploring potential associations with various types of air conditioning systems. The researchers measured CO, CO2, O3, TVOC, HCHO, PM2.5, and PM10, as well as airborne bacteria and fungi at 96 sites within seven distinct work areas. These areas were equipped with four major types of air conditioning systems, and the hospitals were randomly selected throughout Taiwan. The statistical analysis revealed higher levels of CO2 and TVOC in wards and pharmacy departments, which also exhibited elevated TVOC levels compared to other areas. This underscores that wards, pharmacies, operating rooms, and laboratories consistently emerge as VOC hotspots across diverse health systems. In Iran, Moslem et al. (2020) [53] found that operating rooms, such as general surgery theaters, exhibited the highest BTEX concentrations, with benzene-related lifetime cancer risks exceeding USEPA thresholds. This study is the first to compare BTEX concentrations in different ORs, but previous studies have reported high levels of BTEX compounds in surgical smoke and breath samples from other surgical settings. A Monte Carlo simulation was applied to assess the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks of exposure to BTEX compounds. The lifetime cancer risk (LCR) from benzene exposure exceeded the USEPA threshold in all ORs (1 × 10−6). The study highlights the need for further research on indoor air quality in operating rooms, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. For Thailand, expanding monitoring from aggregate TVOC toward compound-specific characterization in these high-risk zones would enable more precise exposure and health risk assessments. In the UK, Riveron et al. (2023) [13] used two-dimensional gas chromatography to characterize 36 VOCs in hospitals, reporting 2-propanol and ethyl chloride as the most abundant. Concentrations of naphthalene and ethyl chloride exceeded USEPA inhalation exposure limits, and seasonal variation as well as medical activities strongly influenced VOC patterns. The findings suggest the need for further investigations into the cancer risk associated with trichloroethylene exposure. These findings parallel those of Palmisani et al. (2021) [88] in Italy and Spain, where daily peaks of TVOCs and CO2 coincided with chemotherapy treatment schedules, underscoring the role of occupancy and pharmaceutical use in driving temporal fluctuations.

By contrast, Thai research on VOCs is limited in both volume and scope. Most studies measured only TVOC and formaldehyde, without compound-specific analyses. Reports of “not detected” (ND) values likely reflected sensor limitations (portable PID or low-cost devices) rather than the true absence of exposure. To date, only one study by Surawattanasakul et al. (2022) [5] has linked formaldehyde and TVOC levels to Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) symptoms. Unlike international studies, none have incorporated systematic health risk assessments for cancer or non-cancer outcomes. Furthermore, the 2022 Department of Health Notification established thresholds solely for TVOC (<1000 ppb) and formaldehyde (<0.08 ppm), with no regulatory standards for benzene, toluene, trichloroethylene, or other carcinogenic VOCs commonly regulated abroad.

The quantitative analyses demonstrated a clear concentration-dependent gradient of VOC-related health risks in hospitals, as shown in Supplementary Material SA. At levels below 300 µg/m3 or 0.3 ppm, exposures were minimal, with atrium values of 180–266 ppb [45] and room concentrations of 0.010–0.104 mg/m3 [46], all within national standards. Moderate exceedances were reported in several hospital settings, including consultation rooms (0.17–3.02 ppm, exceeding the German guideline of 1.32 ppm only in consultation rooms; [114]), ICUs (average 282 µg/m3, peak 617 µg/m3, exceeding the WHO limit of 300 µg/m3 and the China NAAQS of 600 µg/m3; [41]), and dental facilities (mean 700 ± 641 ppb, up to 1274 ppb in sterilization rooms, with peaks of 3290 ppb; [112]), with additional exceedances noted in pharmacies and elderly care facilities. High-intensity environments posed the greatest risks: during laparoscopic surgery, benzene reached 477–1266 µg/m3, exceeding USEPA and CalEPA limits, with toluene up to 632 µg/m3 and styrene 216 µg/m3 [64]. In operating theaters, TVOC levels near surgical teams ranged from 0.5 to 33 ppm, with formaldehyde up to 5 ppm—over 20 times the WHO short-term guideline [115]. Broader surveys reported TVOC levels of 279–46,904 µg/m3, with multiple anesthetic compounds, aldehydes, and aromatics exceeding NIOSH and OSHA limits [86]. Additional exceedances were noted in dental sterilization rooms (up to 3290 ppb) and pharmacy storage areas (up to 8398 ppb), surpassing German indoor guide values [112]. These concentrations consistently corresponded with respiratory dysfunction, asthma exacerbation, oxidative stress, and long-term outcomes including leukemia, nasopharyngeal cancer, and congenital heart disease [37,48,77]. Collectively, the evidence demonstrated that VOC-related risks escalated disproportionately at higher concentrations, underscoring the need for targeted interventions in operating theaters, ICUs, dental sterilization rooms, and pharmacy storage areas.

Moreover, hospitals host various healthcare-related activities that can also generate VOCs, encompassing the release of anesthetic gases during surgeries, sterilization procedures involving ethylene oxide, the handling of pharmaceuticals and laboratory chemicals, managing medical waste through incineration, preparing chemotherapy drugs, generating by-products of anesthetic medications such as ethyl chloride, and utilizing antiseptic solutions [9,11]. Additionally, we encountered other investigations focusing on indoor air pollutants within hospital settings, as shown in Table 2 and Table A2. In Thailand, Chokwinyou et al. (2014) [16] discovered significant parallels in the predominant issues. Both hospital and hotel environments exhibited similar critical concerns, including the presence of PM2.5, formaldehyde, as well as bacterial and fungal contaminants. Additionally, their investigation revealed that cooling tower systems and water storage and distribution setups within buildings served as conducive environments for the proliferation and dissemination of Legionella bacteria. Tinochai et al. (2019) [17] aimed to evaluate air quality and thermal comfort within a 120-bed community hospital across five departments. The study utilized biological indoor air pollution measurements. Results showed that total bacteria and fungi levels ranged from 3 to 411 CFU/m3 and 0–289 CFU/m3, respectively, within acceptable limits per the draft Department of Health and Singapore guidelines (not exceeding 500 CFU/m3) [116]. The outpatient department exhibited the highest mean values for both total bacteria (239 CFU/m3) and fungi (111 CFU/m3), correlating with department occupancy. Thermal comfort parameters such as temperature, relative humidity, and air movement fell mostly below recommended values, affecting 70.5%, 93.6%, and 56.4% of all measurements, respectively. Inappropriate ventilation and air conditioning system design, particularly in the male internal medicine department, contributed to discomfort and stuffiness, indicating a need for improvement. Mohammadyan et al. (2019) [18] revealed lower mean indoor concentrations compared to outdoor levels. Indoor and outdoor PM concentrations correlated for PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10, with ambient wind speed affecting PM1.0 and PM2.5 but not PM10 indoor/outdoor relationships. The intensive care unit (ICU) and children’s ward at Shahid Beheshti Hospital showed average indoor/outdoor ratios for PM2.5 close to or above 1.00. Positive associations were observed between indoor and outdoor PM1.0 and PM2.5 concentrations, while no relationship was found with PM10. These findings may guide policymakers in evidence-based initiatives to enhance indoor air quality in enclosed spaces. Onmek et al. (2020) [14] reported higher airborne bacteria concentrations compared to fungi concentrations. Significant differences in bacteria and fungi concentrations were observed across sampling times and hospital wards, while no disparity was noted based on electric fan positions. Correlations between concentrations and environmental parameters, such as temperature, occupancy, and humidity, were identified. Boonphikham et al. (2022) [15] examined IAQ in public health centers (PHCs) and primary healthcare units in Bangkok, focusing on the influence of different locations and ventilation systems on IAQ. PHCs situated on main roadsides exhibited higher average levels of PM2.5, CO2, and CO compared to those on secondary roadsides, with only CO showing significant variation between the two locations, highlighting vehicular emissions as a significant contributor to indoor CO levels. Additionally, comparisons among sampling areas with varying ventilation systems—natural ventilation, air conditioning with and without ventilation fans—revealed significant differences in pollutant levels. Areas with air conditioning without ventilation fans recorded the highest levels of PM2.5 and CO2, while areas with natural ventilation had the highest CO levels. Ventilation emerged as a crucial factor in improving IAQ, suggesting the incorporation of ventilation fans in air-conditioned rooms within PHCs. De Maria et al. (2023) [19] conducted a study at the University Hospital of Bari, Italy, monitoring radon concentrations in different premises over 402 days. The highest mean radon concentration was found in basement rooms, followed by ground-floor, first-floor, second-floor, and third-floor rooms. An average radon concentration lower than the WHO-recommended level of 100 Bq/m3 was detected in 73.5% of the monitored environments. Only 0.9% exceeded the reference level of 300 Bq/m3 set by national law, with exceedances significantly more frequent in the basement area. These studies indicated that Thailand has prioritized other toxic substances over VOCs in hospitals.

Therefore, research from other countries indicates that VOC concentrations vary across healthcare settings, with higher levels typically found in areas such as operating rooms, surgical intensive care units, and dental clinics. Surgical procedures, especially those involving electrocautery devices, are significant contributors to VOC emissions. However, the quantification of indoor VOC emissions, concentrations, and associated health risks in Thai hospitals remains limited compared with other nations. Despite concerted efforts, often encompassing the evaluation of various pollutants such as PM, CO, CO2, and total bacterial and fungal counts, a notable limitation persists in the comprehensiveness of indoor air quality (IAQ) management. This shortfall is evident in the omission or non-detection of specific VOCs, some of which are known human carcinogens (e.g., formaldehyde, benzene, trichloroethylene, toluene), as well as alcohols (e.g., 2-methyl-2-propanol), xylenes, d-limonene, silicon compounds, alkanes, esters, and ketones. Furthermore, results are often presented as TVOC using instruments with limited measurement accuracy, which are considered preliminary. While this reduces monitoring expenses, it may underestimate concentrations or yield “not detected” (ND) results. Additional research employing advanced detection and monitoring instruments, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), is necessary to enhance the characterization of individual VOCs, ideally incorporating formaldehyde measurements along with other pollutants. These efforts aim to improve our understanding of VOC exposure in healthcare settings and enable more accurate assessment of risks to healthcare workers and patients, considering spatial and temporal variations. However, specific regulations governing VOC emissions and exposure limits in hospitals remain limited, underscoring the need for standardized guidelines. Strengthening evidence-based approaches is essential to advance research in this area, particularly in evaluating eco-friendly building improvements within the framework of the Ministry of Public Health’s Smart Energy and Climate Action (SECA) policy, Green & Clean Hospital initiative, while alignment with SDG Target 3.9.1 and the development of harmonized standards consistent with Europe, Asia and international standards (e.g., Germany, China, US EPA, WHO, ASHRAE).

5. Recommendation

5.1. Monitoring Parameters

Based on the results of the literature review, we have identified the problem and recommended conducting a comprehensive assessment of IAQ in Thai hospital buildings across different work areas for comparative purposes. Firstly, the assessment of indoor air parameters should consist of four components (1) thermal comfort parameters (e.g., temperature, humidity, air velocity or movement); (2) particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10); (3) chemical parameters (e.g., CO, CO2, O3, TVOC, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and high-priority VOCs such as benzene, toluene, xylene); and (4) biological parameters (fungi, bacteria, allergens). Secondly, further investigations should ideally include individual VOCs categorized by prevalence, abundance, and toxicity across compound groups such as alkanes, alkenes, aromatics, ketones, and alkyne, as demonstrated in international studies (e.g., Spain, Korea, Bangladesh), where exceedances above WHO or national standards have been documented. More studies of VOCs—ideally also including formaldehyde measurements—are needed to better characterize VOC exposure in healthcare settings and to enable consequent evaluation of risks to healthcare workers and patients. Such detailed profiling will enable risk assessments that go beyond general TVOC thresholds.

5.2. Monitoring Instruments

At present, many Thai hospital studies employ low-cost sensors or PID-based devices. Careful consideration must be given to the appropriateness of these measurement devices when establishing standard or surveillance values. Two widely employed techniques for the statistical analysis of VOC are photoionization detectors (PIDs), which cannot detect methane, and flame ionization detectors (FIDs), which cannot detect inorganic substances and some highly oxygenated compounds [117]. However, the use of GC-FID (Gas Chromatography-Flame Ionization Detector) or GC-MS will provide more accurate, reliable measurements, enabling the detection of specific VOCs at low concentrations [118]. These methods offer sensitive detection and reliable quantification of carcinogenic VOCs at trace levels, as shown in studies from China, India, and Taiwan.

5.3. Exposure Risk Determination

Exposure to indoor VOCs in hospital or healthcare settings poses potential health risks to patients, healthcare workers, and other occupants. Health effects include respiratory irritation, exacerbation of asthma and allergies, and long-term risks such as carcinogenicity. Vulnerable populations, such as individuals with congenital abnormalities, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women, may be particularly susceptible to adverse health effects. In assessing potential human health impacts, a holistic approach should be undertaken, considering three crucial aspects: (i) IAQ; (ii) concentration and adherence to occupational exposure limits (OELs), and (iii) a comprehensive evaluation of health impacts and risks, encompassing both cancer and non-cancer outcomes among healthcare workers, patients, and visitors in various areas as highlighted by international evidence.

5.4. Prevention and Mitigation

Hospitals must remain vigilant regarding potential VOCs sources to mitigate human exposure risks. This necessitates the adoption of measures such as employing VOC-free products by replacing hazardous cleaning agents and disinfectants with safer alternatives and building materials, incorporating principles of healthy building design (e.g., waiting room layouts that limit crowding and activities), enhancing air filtration (e.g., high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters and activated carbon filtration systems), addressing leakage through sealing, improving ventilation and air exchange systems, and implementing robust indoor air quality management practices to reduce air pollutant levels, including VOCs, within hospital indoor environments, as well as encouraging the use of personal protective equipment. Additionally, routine maintenance of Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems and regular assessment of indoor air quality are essential to uphold a safe and healthy environment for patients, staff, and visitors. Implementing real-time IAQ monitoring dashboards in high-risk areas (e.g., operating theaters, pharmacies, laboratories) and training staff in safe chemical-handling practices is also recommended. Such interventions, already trialed in European and Asian hospital settings, should be localized and scaled for Thai hospitals.

5.5. Futures Studies

To advance research on VOCs in Thai hospitals and establish acceptable values for compound-specific exposure, future study designs should be expanded to cover multiple hospital types and diverse functional areas (e.g., operating rooms, emergency rooms, ICUs, waiting areas, laboratories, pharmacies, drug storage rooms, and wards) across different seasons. Longitudinal health outcome studies are needed to link VOC exposure with respiratory, reproductive, and carcinogenic risks. Such studies should employ high-resolution instruments (e.g., GC/MS) capable of detecting multiple compounds, including those present at trace concentrations. Thermal comfort parameters and other co-pollutants should also be incorporated to better understand synergistic interactions between environmental factors. Comprehensive risk assessments addressing both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic outcomes are essential. In addition, future work should evaluate the effectiveness of mitigation strategies (e.g., advanced ventilation systems, substitution of hazardous materials) and conduct comparative analyses against international benchmarks to guide the development of Thai IAQ standards. By adopting these directions, Thailand can move beyond simple parameter listings toward a robust, evidence-driven VOC management framework, ultimately reducing risks for healthcare workers, patients, and vulnerable populations.

6. Conclusions

Exposure to VOCs in hospital environments is widespread and poses clinically significant health risks. Across international studies, at least 32 VOCs have been identified, with 13 confirmed or suspected carcinogens, including benzene, formaldehyde, and trichloroethylene. Non-carcinogenic compounds such as ethanol, isopropanol, and limonene were also frequently detected at concentrations sufficient to trigger dose-dependent acute symptoms such as mucosal irritation, headache, and fatigue. Chronic exposures, particularly among healthcare workers and immunocompromised patients, carry elevated risks of respiratory disorders, neurological impairment, and malignancy.

In Thailand, several gaps and challenges remain, including the limited body of research on compound-specific VOCs, with most investigations restricted to TVOC and formaldehyde monitoring; the absence of health risk assessments and comprehensive concentration standards; and substantial variation in pollutant levels across hospital locations, especially in high-risk zones such as operating theaters, laboratories, and pharmacies, where VOC concentrations are highest. Moreover, regulatory frameworks in Thailand currently prescribe limits only for TVOCs and formaldehyde, falling short of international guidelines that specify thresholds for a wider range of VOCs. Such gaps expose healthcare workers and patients to inadequately controlled risks.

The findings of this review highlight three overarching conclusions. First, routine monitoring systems in Thai hospitals require modernization, moving beyond low-cost sensors toward advanced instruments such as GC–MS to enable the precise speciation and quantification of VOCs. Second, health risk evaluations must integrate both cancer and non-cancer endpoints, explicitly linking exposure duration and dose–response relationships across diverse hospital microenvironments. Third, policy development should be guided by international best practices, harmonizing occupational exposure limits and IAQ standards to protect vulnerable populations, including neonates, pregnant women, and immunocompromised patients.

In sum, the current body of evidence underscores VOCs as a neglected but critical determinant of indoor air quality in hospitals. Addressing this issue requires comprehensive surveillance, evidence-based exposure limits, and preventive interventions—aligned with Thailand’s Smart Energy and Climate Action policy (SECA), the Green & Clean Hospital initiative, and the Sustainable Development Goals (Target 3.9.1). Without these measures, both immediate and long-term health risks from VOC exposure will persist, undermining the safety and sustainability of hospital environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos16101135/s1, Supplementary Material SA: Summary of 87 studies on indoor VOCs in hospitals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M. and W.S.; methodology, W.M. and W.S.; software, W.S.; formal analysis, W.M.; validation, W.M. and S.K.; resources, T.J.; data curation, W.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M., T.J., and S.K.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, W.M.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, W.M. and S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding support from the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation [B41G680024].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Appendix.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Yot Teerawattananon for his valuable administrative guidance and institutional support during the conceptualization and initial development of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

| TVOCs | Total Volatile Organic Compounds |

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality |

| SBS | Sick Building Syndrome |

| HEPA | High-Efficiency Particulate Air |

| PID | Photoionization Detector |

| FID | Flame Ionization Detector |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| OEL | Occupational Exposure Limit |

| SECA | Smart Energy and Climate Action |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| AT | Air Temperature |

| AM | Air Movement |

| HCHO | Formaldehyde |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| TD-GC-MS | Thermal Desorption Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| LTCR | Lifetime Cancer Risk |

| HQ | Hazard Quotient |

| HI | Hazard Index |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sources and activities for VOCs and their potential health impacts.

Table A1.

Sources and activities for VOCs and their potential health impacts.

| Sources and Activities | Individual VOCs | Potential Health Impacts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | Long-Term | ||

| Operating rooms | anesthetic gases, aromatic hydrocarbons, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, other aldehydes, oxides, alcohols | dizziness, nausea, fatigue, headache, respiratory irritation, irritation of eyes, skin; asthma exacerbation | central nervous system, liver, kidney damage; reproductive issues; increased risk of leukemia and miscarriage, hematological disorders, carcinogenicity (nasopharyngeal and sinonasal cancer), respiratory issues, allergic reactions, occupational asthma, dermatitis, cardiovascular disease, blindness (in severe cases), addiction (in the case of ethanol) |

| Disinfection rooms | glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde, other aldehydes, alcohols, aromatic hydrocarbons, aliphatic hydrocarbons, halogenated hydrocarbons, ketones, ethers, limonene | irritation of eyes, nose, throat, skin, respiratory symptoms, headache, dizziness, | respiratory issues (e.g., asthma), potential carcinogenic effects, liver and kidney damage, neurological effects, respiratory irritation, central nervous system effects, potential sensitization |

| Laboratories | formaldehyde, other aldehydes, alcohols, aromatic hydrocarbons, aliphatic hydrocarbons, halogenated hydrocarbons, ketones, ethers, limonene | irritation of eyes, nose, throat, skin, respiratory symptoms, headache, dizziness | respiratory issues (e.g., asthma), potential carcinogenic effects, liver and kidney damage, neurological effects, |

| Nursing rooms | aromatic, aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) | eye irritation, nausea, and vomiting | increased risks of lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory disorders like asthma, developmental issues on child, reproductive toxicity |

| Sterilization of medical equipment (disinfection and sterilization) | ethylene oxide, glutaraldehyde | respiratory irritation, nausea, headaches, central nervous system, skin irritation | blood cancer (e.g., leukemia) and breast cancer, reproductive, neurological, respiratory effects (e.g., asthma) |

| Disinfectants and preserving specimens | formaldehyde | respiratory irritation, allergic reactions, headaches, dizziness, difficulty breathing | nasopharyngeal cancer and leukemia, respiratory issues, reproductive, developmental, neurological effects |

| Painting and renovation | toluene, xylene, formaldehyde, benzene, ethylene glycol ethers, acetone | respiratory irritation, eye irritation, headaches, dizziness, nausea, allergic reactions | neurological effects (e.g., headaches, dizziness), CNS depression, liver and kidney damage, respiratory issues (e.g., asthma), potential carcinogenic effects (leukemia and other blood disorders), potential reproductive and developmental toxicity |

| Building materials | trichloroethylene | irritating to the eyes, skin and respiratory tract. | Several cancers, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma and livers tumors |

| Alcohol-based hand sanitizer | ethanol, 2-propanol | skin irritation and allergic reactions, particularly in individuals with sensitive skin or pre-existing skin disorder | Excessive use of ABHS may result in a rise in other viral diseases and antimicrobial resistance due to the selection of resistant strains, particularly for bacteria |

| Building materials and occupants, personal care products, decoration materials and pharmaceutical products | acetone, various siloxanes, aldehydes (most abundant VOCs measured in hospitals) | irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, headaches, dizziness, nausea, respiratory symptoms (e.g., coughing, wheezing), allergic reactions | chronic respiratory irritation, central nervous system effects with prolonged exposure, developmental and reproductive toxicity, potential hormonal disruption. |

| Cleaning products | terpene (D-limonene) | skin irritation | skin sensitization if the substance has been oxidized |

| diethyl phthalate (DEP) | skin irritation, headache, dizziness, nausea | androgen-independent male reproductive toxicity (i.e., sperm effects) | |

| acetaldehyde | skin allergy | possible carcinogens | |

| Pesticides | xylene, toluene, ethylbenzene, methyl ethyl ketone (MEK), dichloromethane (methylene chloride), acetone, hexane, chloroform | respiratory irritation, eye and skin irritation, headaches and dizziness, neurological effects, allergic reactions: | neurological disorders, respiratory diseases, liver and kidney damage, cancer risk |

Table A2.

Summary of previous noticeable international research on indoor VOC air pollution in hospitals.

Table A2.

Summary of previous noticeable international research on indoor VOC air pollution in hospitals.

| Study | VOC Sources | Indoor Quality (Parameter and Concentration) | Measuring and Analytical Instruments (VOCs) | Concentrations Standards/Guidelines and Occupational Exposure Limits (OEL) of VOCs | Clinical Symptoms or Health Risk Assessment (Non-Cancer, Cancer) | Challenges and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] Germany | Alcohol-based disinfectants, cleaning products, building materials and furnishings, medical furniture and incubator materials, Human presence (staff and visitors) | Temperature, humidity, particulate matter (PM), * VOCs average in incubator: 1.1 [0.35–1.3] ppm, and odorous gases (OG) | U-Monitor, a monitoring device from U-Earth Biotech, London, UK to provide real-time data | Federal Environmental Agency (Germany) sets a total concentration limit of VOC at 25 mg/m3, equivalent to 0.4 ppm, which can lead to headaches and neurotoxicity. The study reported that the measured VOC concentrations significantly exceeded the regulatory limit over extended periods, indicating potential health risks for individuals | Headaches and neurotoxicity | Measurements being performed in an empty incubator and the data being collected in only one neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The study also did not measure the density of staff and visitors. Additionally, the standard for measuring fine dust in the outside air is the gravimetric measurement, which was not used in this study |

| [88] European (Italy and Spain) | Human occupancy, the administration of pharmaceutical products, and the use of disinfectants and cleaning products, wood products, occasional external infiltration ambient air, secondary organic aerosol (SOA) | Concentration peaks of TVOCs (0.60–1.40 ppm), PM2.5, and CO2 were observed during hours of higher human occupancy, particularly during scheduled chemotherapy treatments. AT and RH were also recorded | TVOCs, PM2.5, and CO2 were measured in high temporal resolution to assess indoor air quality. For TVOCs used Corvus IAQ Monitor (Ion Science, UK) with a photo-ionization detector (PID) | N/A | N/A | Spatial distribution analysis omitted, issues with low-cost sensor accuracy, influence of environmental parameters (like humidity) on sensors, insufficient data from multiple monitoring points |

| [36] Bangladesh | Indoor air pollution in hospitals can be caused by various sources such as disinfectants, sterilizers, laboratory materials, medical procedures, medical wastes, construction, cooling towers, humidifiers, contaminated carpets, and outdoor sources (Chemicals like alcohol, chlorhexidine gluconate, and aldehydes used for handwashing and disinfection purposes in hospitals) | Average concentrations of IAQ indicators in hospitals were 67.6–104.1 (PM1.0), 89.2–137.4 (PM2.5), 103.3–159.0 (PM10) mgm−3; 0.02–0.11 (NO2), 234.2–1047.1 (CO2), and 117.7–176.5 (TVOC) ppm | Aeroqual 500 series sampler for trace gas measurement, including TVOCs, and the use of a photoionization detector for TVOC measurement | Specific concentration standards for VOCs were not mentioned in the provided sources. But, Indoor TVOC levels were about two times higher than outdoor levels and higher in the post-monsoon season compared to winter. | N/A | Limited research on VOCs specifically, absence of health risk assessments and concentration standards, and variations in pollutant levels across different locations within hospitals. |

| [10] Taiwan | Ward and pharmacy departments (cleaning agents and disinfectants, medical treatments and solutions, building materials and furnishings, sterilization chemicals) | CO, CO2, O3, Mean TVOC = 0.54 ppm, HCHO = 0.02 ppm, PM2.5, PM10, airborne bacteria and fungus | RAE/PGM-730 instrument (ppbRAE 3000 real-time monitor) for TVOC and DNHP tube, analyzed by HPLC with UV detection at 254 nm for HCHO | TVOC and HCHO remained below limits in most areas based on Taiwan IAQ Standards | TVOC exposure causes eye irritation, and respiratory issues depending on the compound (e.g., ethers). | Seasonal bias (winter), lack of chemical speciation, limited spatial scope, population density not controlled, sampling limitation (only spot sampling) |

| [11] Finland | Building materials (PVC flooring materials, adhesive and filling), alcohol-based cleaning chemicals and hand disinfectants, Medical and laboratory activities (especially in pathology wards), office equipment and hygiene products | TVOC and individual VOC such as 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, toluene, ethylbenzene, octane, decane, xylenes (A total of 123 different VOCs were detected in all the samples combined. From the materials samples 79 VOCs were detected while 84 were detected in indoor air samples) as well as AT, RH, AM. | Tenax TA tubes (Active) and TD-GC-MS system | TVOC > 1200 µg/m3 as threshold contributing to symptoms | MM-40 survey (e.g., skin reactions, upper respiratory, headaches) | Limitations in identifying exact reasons for symptoms, outdated building service engineering and ventilation systems, as well as aged plumbing, were identified as major factors contributing to indoor air quality problems in hospitals, relationships between indoor environmental quality, psychosocial issues, working conditions, and symptoms are complex and not completely understood, presence of certain compounds, such as 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, in the hospital environment can also be found in other indoor environments, indicating that the compounds may not be specific to hospitals, sampling method (Tenax TA) was not suitable for detecting some alcohol-based |

| [12] Finland | Disinfectants and cleaning products, exhaust air terminal, building materials and furnishings (e.g., floor), occupant-related sources (e.g., silicon-based VOCs from personal care products) | Mean TVOC < 55 µg/m3, individual VOCs | Tenax TA tubes were used to collect and analyzed with Thermal Desorption and GC-MS | Finnish Indoor Classification M1 standard: TVOC emission target: <200 µg/m2h | N/A | Measurement uncertainty, emission area assumptions, weak predictive models (R2 < 0.10), room size effects |

| [9] France | Building-related sources (building and decoration materials), different products (laboratory chemicals, cleaning/disinfectant, alcohol-based, pharmaceutical products/antiseptics, anesthetic gases), personal care products. post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), patient room, and nursing care had highest alcohol levels. Disinfection unit had highest levels of chloroform and other halogenated hydrocarbons. | More than 40 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including aliphatic, aromatic and halogenated hydrocarbons, aldehydes, alcohols (ethanol = 928 µg/m3, isopropanol = 47.9 µg/m3), ketones, ethers = 75.6 µg/m3, terpenes and acetone = 22.6 µg/m3, HCHO = 5.8 µg/m3, Limonene = 8.7 µg/m3 | Multi-sorbent tubes (Carbopack C/B, Carboxen 1000; Tenax TA), DNPH cartridges for aldehyde sampling, ATD/GC/MS methods for VOCs, and HPLC with diode array detector for aldehydes | Although concentrations were below occupational exposure limits set in France, European Union and United States of America, the complex mixture of VOCs present in indoor air poses a potential risk to healthcare workers and patients due to the variety of chemical products. HCHO and benzene based on WHO guideline. | N/A | Single-site study, sampling method (stationary sampling at fixed points, which may not accurately reflect the real exposure of workers and patients to VOCs), lack of assessment of clinical symptoms, and the need for further research on OELs, temporal limitation |

| [8] China | Waiting areas (construction materials, furnishings, diesel emission, cleaning products, and industrial emission) | More than 100 VOCs in indoor and outdoor with average VOCs = 123.6–713.2 µg/m3. Toluene, xylenes, ethylene, and benzene were the most abundant aromatics with indoor concentrations significantly higher than outdoors except benzene. Toluene and xylenes were found exceeding the indoor air standard of China | Preconcentrator-GC/MS system | Specific VOCs like toluene, xylenes, ethylene, and benzene were the most abundant aromatics, with concentrations exceeding the indoor air standard of China (2003) in some areas | N/A | VOCs in hospital waiting areas in China varied, there are outdoor air factors involved for benzene, n-hexane, and toluene, VOCs such as n-nonane, decane, undecane, m/p-xylene, and tetrachlorethylene were about 3–4 times more concentrated indoors compared to outdoors |

| [13] United Kingdom | Consultation rooms (pediatric admissions unit and pediatric respiratory physiology laboratory); anesthesia, alcohol-based product (hand-sanitiser), building materials or related to ingress of vehicle emissions | TVOC, 36 VOCs (alcohols, ketones, aromatic hydrocarbons, aliphatic hydrocarbons, aldehyde, terpenes and terpenoids, halogenated hydrocarbons, ethers phthalate, siloxanes, acetone, hexane); highest concentrations for 2-propanol and ethyl chloride | Tenax/TA sorbent tubes with Carbograph 1TD sorbent tubes were used to collect and analyzed with TD-GC × GC-MS/FID analysis | Ethyl chloride concentrations were four times higher than the US EPA (environmental health guidelines), USEPA and OEHHA inhalation exposure limit values; naphthalene and ethyl chloride > USEPA | Non-cancer health hazard of all VOCs was negligible (hazard quotients < 1), ethyl chloride exceeds non-cancer guideline, trichloroethylene was identified as a potential risk to healthcare workers with long-term exposure, as the cancer risk (CR) exceeded the threshold of 10- | Further investigations on trichloroethylene exposure cancer risk may be considered to ensure the safety of healthcare workers, convenience samples (no repeated set-time samples), sorbent tubes used were not able to capture such a small VOC with high volatility (CHCO, acetaldehyde), short sampling time (underestimation), absence of information about specific healthcare activities |

| [119] Iran | Anesthetic gases in operating rooms | Isoflurane = 17.5–23.6, ppm, and sevoflurane = 1.5–7.8 ppm | Sorbent tube and analyzed with GC/FID | Within the range recommended by Iran’s Occupational and Environmental Health but long-term exposure to anesthetic gases may endanger the health | Non-carcinogenic risk based on US EPA, HQ < 1; acceptable | Limited sample size, short duration of sampling, potential variability in exposure, risk assessment methodology used the HQ only (not accounting for all potential health effects, possibly underestimating the overall risk), long-term health implications |

Note: means no study, * means exceed the standard, AT (air temperature), RH (relative humidity), AM (air movement), PM (particulate matter), HCHO (Formaldehyde), CO2 (carbon dioxide), CO (carbon monoxide), TVOC (total volatile organic compounds), ppb (parts per billion), ppm (parts per million), µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic meter), HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography), GC (gas chromatography), TD–GC–MS (thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry), ATD/GC–MS (automated thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, TD-GC×GC-FID/MS (thermal desorption coupled to two-dimensional gas chromatography with dual flame ionization detection and mass spectrometry, N/A (not applicable).

References

- Kumar, P.; Singh, A.B.; Arora, T.; Singh, S.; Singh, R. Critical review on emerging health effects associated with the indoor air quality and its sustainable management. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpanyaskul, C. Etiological investigation of unintentional solvent exposure among university hospital staffs. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 14, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepeis, N.E.; Nelson, W.C.; Ott, W.R.; Robinson, J.P.; Tsang, A.M.; Switzer, P.; Behar, J.V.; Hern, S.C.; Engelmann, W.H. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2001, 11, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.P. Indoor air quality and health. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 4535–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surawattanasakul, V.; Sirikul, W.; Sapbamrer, R.; Wangsan, K.; Panumasvivat, J.; Assavanopakun, P.; Muangkaew, S. Respiratory Symptoms and Skin Sick Building Syndrome among Office Workers at University Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand: Associations with Indoor Air Quality, AIRMED Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kwon, T.G.; Chung, S.K.; Kim, T.H. Surgical smoke may be a biohazard to surgeons performing laparoscopic surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2014, 28, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Diehl, T.; Zanni, S.; Singer, D.; Deindl, P. Indoor Climate and Air Quality in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Neonatology 2020, 117, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Xie, P.; Luo, C. Characteristics of Volatile Organic Compounds: Concentrations and Source Identification for Indoor and Outdoor Hospital Waiting Areas in China. Epidemiology 2011, 22, S209–S210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessonneau, V.; Mosqueron, L.; Berrubé, A.; Mukensturm, G.; Buffet-Bataillon, S.; Gangneux, J.P.; Thomas, O. VOC contamination in hospital, from stationary sampling of a large panel of compounds, in view of healthcare workers and patients exposure assessment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.-C.; Wu, P.-C.; Tseng, C.-H.; Su, H.-J. Indoor air quality varies with ventilation types and working areas in hospitals. Build. Environ. 2015, 85, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, P.; Hyttinen, M.; Ruokolainen, J.; Saarinen, P.; Timonen, J.; Pasanen, P. Indoor air-related symptoms and volatile organic compounds in materials and air in the hospital environment. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2019, 29, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyttinen, M.; Rautiainen, P.; Ruokolainen, J.; Sorvari, J.; Pasanen, P. VOCs concentrations and emission rates in hospital environment and the impact of sampling locations. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2021, 27, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveron, T.P.; Wilde, M.J.; Ibrahim, W.; Carr, L.; Monks, P.S.; Greening, N.J.; Gaillard, E.A.; Brightling, C.E.; Siddiqui, S.; Hansell, A.L.; et al. Characterisation of volatile organic compounds in hospital indoor air and exposure health risk determination. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onmek, N.; Kongcharoen, J.; Singtong, A.; Penjumrus, A.; Junnoo, S. Environmental Factors and Ventilation Affect Concentrations of Microorganisms in Hospital Wards of Southern Thailand. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 7292198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonphikham, N.; Singhakant, C.; Kanchanasuta, S.; Patthanaissaranukool, W.; Prechthai, T. Indoor Air Quality in Public Health Centers: A Case Study of Public Health Centers Located on Main and Secondary Roadsides, Bangkok. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 2022, 20, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokwinyou, P.; Pensuk, C.; Paweenkitiporn, W. Indoor air quality in hospitals and hotels, Thailand. J. Environ. Health 2014, 16, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tinochai, P.; Tealek, M.; Kongpran, J. Indoor Air Quality in Hospital: A Case Study for a Community Hospital in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province. J. Health Sci. Thail. 2019, 28, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadyan, M.; Keyvani, S.; Bahrami, A.; Heibati, B.; Godri Pollitt, K. Assessment of indoor air pollution exposure in urban hospital microenvironments. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2019, 12, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, L.; Sponselli, S.; Caputi, A.; Delvecchio, G.; Giannelli, G.; Pipoli, A.; Cafaro, F.; Zagaria, S.; Cavone, D.; Sardone, R.; et al. Indoor Radon Concentration Levels in Healthcare Settings: The Results of an Environmental Monitoring in a Large Italian University Hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.T.; Ni, P.; Urrutia, A.R.; Huynh, H.T.; Worrilow, K.C. Modelling the equilibrium partitioning of low concentrations of airborne volatile organic compounds in human IVF laboratories. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 46, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.J.; Pal, V.K.; Kannan, K. A review of environmental occurrence, toxicity, biotransformation and biomonitoring of volatile organic compounds. J. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2021, 3, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohura, T.; Amagai, T.; Shen, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, L. Comparative study on indoor air quality in Japan and China: Characteristics of residential indoor and outdoor VOCs. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 6352–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Niculescu, V.C. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) as Environmental Pollutants: Occurrence and Mitigation Using Nanomaterials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalender Smajlović, S.; Kukec, A.; Dovjak, M. Association between Sick Building Syndrome and Indoor Environmental Quality in Slovenian Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchner, S.; Mandin, C.; Derbez, M.; Ramalho, O. Quality of Indoor Air, Quality of life, a Decade of Research to Breathe Better, Breathe Easier; French Indoor Air Quality Observatory: Champs-sur-Marne, France, 2013; Volume 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Billionnet, C.; Gay, E.; Kirchner, S.; Leynaert, B.; Annesi-Maesano, I. Quantitative assessments of indoor air pollution and respiratory health in a population-based sample of French dwellings. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J.Y.; Godwin, C.; Parker, E.; Robins, T.; Lewis, T.; Harbin, P.; Batterman, S. Levels and sources of volatile organic compounds in homes of children with asthma. Indoor Air 2014, 24, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colareta Ugarte, U.; Prazad, P.; Puppala, B.L.; Schweig, L.; Donovan, R.; Cortes, D.R.; Gulati, A. Emission of volatile organic compounds from medical equipment inside neonatal incubators. J. Perinatol. 2014, 34, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]