Abstract

Langer–Giedion syndrome (LGS), also known as trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type II (TRPS II; OMIM #150230), is a contiguous-gene deletion disorder caused by haploinsufficiency of TRPS1 and EXT1. Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) is genetically heterogeneous; heterozygous variants in RAD21 cause the milder CdLS type 4 phenotype (OMIM #614701). Because RAD21 lies between TRPS1 and EXT1, overlapping phenotypes may arise when all three genes are deleted. We report a unique case of a 4-year-old female presenting with a blended phenotype of Langer–Giedion Syndrome (LGS) and Cornelia de Lange Syndrome (CdLS) type 4. This case is distinct from previously reported 8q deletions in three key aspects: (1) Complex Genomic Architecture: Chromosomal microarray revealed a novel complex rearrangement consisting of a 13.01 Mb mosaic interstitial deletion at 8q23.1–q24.12, flanked by two large duplications (21.5 Mb at 8q11.23–q23.1 and 25.78 Mb at 8q24.12–q24.3). (2) Rare Mosaicism: This represents only the second reported case of mosaicism affecting this contiguous gene region. Notably, the patient demonstrates a “mosaic rescue” effect, where the mosaicism appears to have mitigated the neurodevelopmental phenotype (the patient is bilingual and ambulatory) while failing to protect the skeleton. (3) First Bone-Specific Therapy: The patient suffered from severe, recurrent fractures due to a synergistic “double hit” of TRPS1-related osteopenia and EXT1-related exostoses. We report the first successful use of bisphosphonate therapy (pamidronate) in this specific mosaic profile, which resulted in a complete cessation of fractures during a 12-month follow-up. This case underscores the utility of detailed microarray analysis in complex phenotypes and suggests bisphosphonates as a viable rescue therapy for refractory syndromic osteoporosis.

1. Introduction

Langer–Giedion syndrome (LGS), also known as Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type II (TRPS II), is a rare autosomal dominant contiguous-gene deletion disorder involving TRPS1 (8q23.3) and EXT1 (8q24.1) [1,2,3]. The phenotype combines features of TRPS I—craniofacial dysmorphism and cone-shaped epiphyses—with hereditary multiple exostoses type I due to EXT1 haploinsufficiency and multiple osteochondromas [4,5,6]. The shortest region of deletion overlap has been localized near 8q24.11, spanning TRPS1 and EXT1 [1,3].

Clinically, TRPS is divided into three types. TRPS I results from TRPS1 variants and features skeletal abnormalities, sparse hair, thick eyebrows, a bulbous nasal tip, long philtrum, thin upper lip, and large ears [7,8]. TRPS II (LGS) reflects larger deletions including TRPS1 and EXT1 and adds multiple exostoses and, often, intellectual disability [9]. TRPS III arises from specific TRPS1 missense variants and is associated with severe short stature and brachydactyly without exostoses [10]. LGS prevalence is ~1:100,000 [11].

Cornelia de Lange syndrome type 4 (CdLS-4; OMIM #614701) is an autosomal dominant cohesinopathy caused by heterozygous pathogenic variants or deletions involving RAD21 [12,13]. CdLS-4 is generally milder than classic NIPBL-related CdLS and is characterized by synophrys, arched eyebrows, a low anterior hairline, anteverted nares, long philtrum, thin upper lip, growth delay, and variable neurodevelopmental involvement [12,13,14]. RAD21 encodes a core component of the cohesin complex, which plays a critical role in sister chromatid cohesion, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and apoptosis [15].

Importantly, TRPS1, RAD21, and EXT1 lie in close genomic proximity on chromosome 8q23.3–q24.11, creating the potential for blended phenotypes when deleted together. TRPS1 encodes a GATA-type transcription factor that regulates chondrocyte differentiation by repressing RUNX2 and IHH, thereby influencing endochondral ossification and bone mineralization [16,17]. EXT1, which forms a hetero-oligomeric complex with EXT2, is essential for heparan sulfate biosynthesis, and its haploinsufficiency leads to the formation of osteochondromas [4,5]. Loss of RAD21 contributes primarily to craniofacial, growth, and neurodevelopmental features through disruption of cohesin-mediated chromatin organization and gene regulation [12,14,15].

Deletions spanning 8q23.1–q24.12 may encompass additional genes—such as KCNQ3 and CSMD3—and thereby broaden the phenotypic spectrum to include epilepsy, central nervous system anomalies, and endocrine or metabolic manifestations [18,19,20,21]. Mosaicism further modulates clinical severity and tissue-specific expressivity, complicating genotype–phenotype correlations [22,23]. Prior reports of non-mosaic and complex rearrangements involving this region have demonstrated overlapping LGS and CdLS features [18,19,24].

Here, we describe a highly distinctive case characterized by a novel complex genomic architecture consisting of a mosaic interstitial 8q23.1–q24.12 deletion flanked by two large duplications. This report contributes to the literature in three key ways: (1) it documents a previously unreported duplication–deletion–duplication rearrangement within the LGS/CdLS spectrum; (2) it represents only the second reported case of mosaicism affecting the TRPS1–RAD21–EXT1 contiguous gene interval; and (3) it provides the first clinical evidence supporting the use of bisphosphonate therapy, informed by prior experience in TRPS-associated osteoporosis [25], in a patient with this specific mosaic blended phenotype and recurrent fractures.

2. Case Description

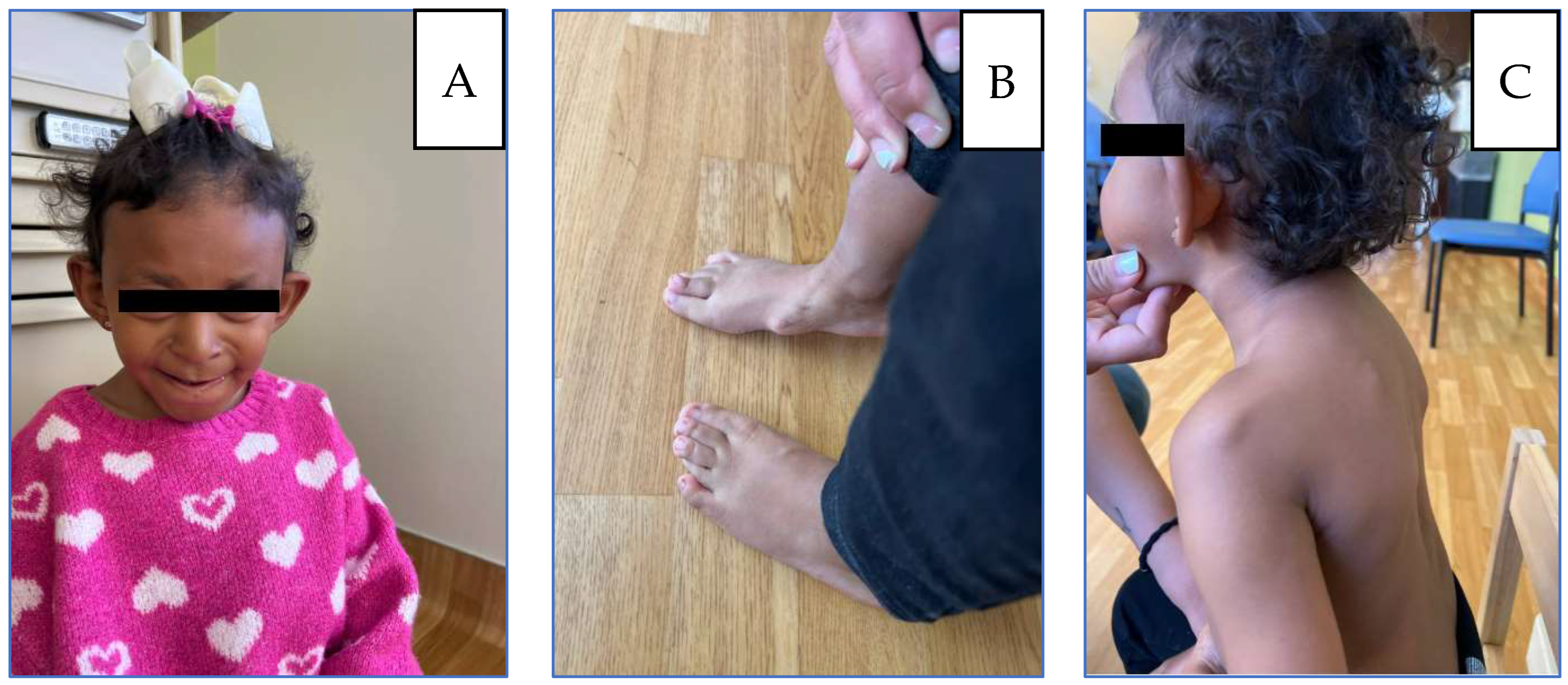

The patient first presented to the genetics clinic at age two (21 December 2021) for evaluation of multiple congenital anomalies and an abnormal chromosomal microarray suggestive of an unknown genetic syndrome. She was born at 39 + 3 weeks to a 30-year-old father and a 25-year-old mother. The pregnancy was notable for maternal alcohol use until 6–7 weeks of gestation, after which it was discontinued. Developmentally, she began walking independently at 16 months, and language milestones were achieved on time; she is bilingual (English/Spanish). She had a history of multiple congenital features, including microcephaly, plagiocephaly, post-axial polydactyly, overlapping toes on the left foot, and dysmorphic facial features. Her surgical history included correction of right hip dysplasia and repair of post-axial polydactyly. She had sustained a right femur fracture three months before the initial visit. On physical examination, she was noted to have large ears, a flat nasal bridge, a bulbous nasal tip, a long philtrum, and a thin upper lip; extremities were not examined (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Patient at 5 years: microcephaly, large protruding ears, broad nasal bridge, underdeveloped alae nasi, wide low-hanging columella. (B) Thoracic kyphosis and winged scapulae with posterior protrusion of the superomedial left scapula and acromioclavicular region. (C) Flat feet, Bilateral overlapping toes, and osteochondromas located on the internal side of the foot.

A bone survey from an outside hospital revealed an acute angulated comminuted fracture of the right distal femoral metadiaphysis. There was a bony deformity involving numerous long bones with multiple sessile osteochondromas, likely secondary to underlying multiple hereditary exostoses. Postoperative changes were consistent with right proximal femoral osteotomy without evidence of hardware complications. In addition, there was an asymmetric appearance of the feet with soft-tissue prominence along the medial aspect of the right midfoot, correlating with the physical examination. No abnormalities of the axial skeleton or cone-shaped epiphyses were noted. Family history was significant for Noonan syndrome in a maternal half-cousin and polydactyly in the paternal great-grandmother. Paternal history was otherwise limited, and consanguinity was denied.

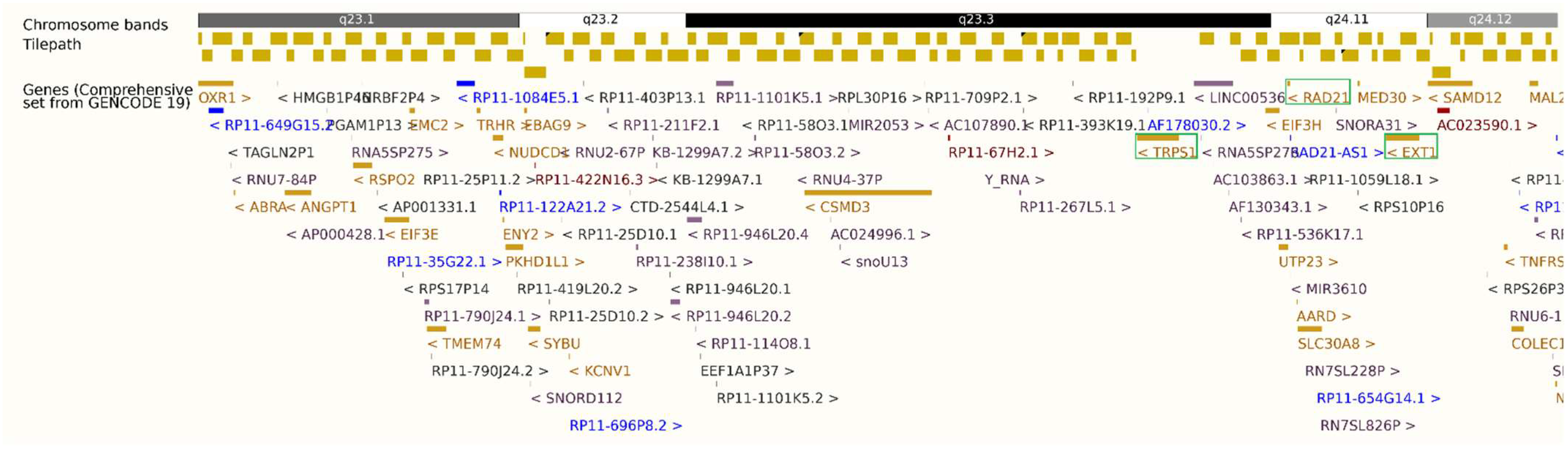

Chromosomal microarray (13 October 2021) revealed: (1) a 21.5 Mb mosaic interstitial duplication at 8q21.2–q23.1, (2) a 13.01 Mb mosaic interstitial deletion at 8q23.1–q24.12, and (3) a 25.78 Mb mosaic terminal duplication at 8q24.12–q24.3 (Figure 2 and Figure S1, Table S1). Approximately 10% of nucleated blood cells carried the duplications, while ~75%—predominantly granulocytes—harbored the interstitial deletion. The deleted interval included OXR1, ANGPT1, RSPO2, TRHR, PKHD1L1, TRPS1, RAD21, SLC30A8, EXT1, SAMD12, TNFRSF11B, and COLEC10 (Table 1, Figure 2). Maternal microarray was normal. Father was not available for the test.

Figure 2.

Ensembl GRCh37.p13 export showing the 8q23.1–q24.12 deletion (hg19: 8:107,431,257–120,443,762) and proximity of TRPS1, RAD21, and EXT1 (8q23.3–q24.11), highlighted in green box. Gene font colors represent different biotypes: gold for protein-coding genes, blue for non-coding RNA/antisense transcripts, and red/purple for pseudogenes.

Table 1.

List of OMIM disease-associated genes in the mosaic deletion interval. The information is sourced from the UCSC Genome Browser (2025 Update) using the Table Viewer tool [26,27]. OMIM genes in the deletion interval without a phenotype association were omitted from the final table.

At age three, she sustained a left wrist fracture; at age four prior to returning to the genetics clinic (24 October 2023), she sustained a left distal radial and distal right clavicular fracture. During the visit, the mother reported that she exhibited distractibility and reduced speech clarity but no other significant global developmental concerns. Overlapping toes, intoeing, and bone pain had worsened. She had a history of low muscle tone and strength for which she was receiving physical and occupational therapy. She subsequently underwent excision of a left femoral osteochondroma. Growth parameters tracked between the 10th and 50th percentiles for girls in the general population, but between the 80th and 95th percentiles relative to Cornelia de Lange syndrome norms. On physical exam, besides microcephaly, protruding ears, bulbous nose, thin upper lip as described in the previous visit, additional findings including sparse, wiry, and coarse scalp hair, synophrys with lateral thinning of eyebrows, prominent nasal bridge, short upturned nose, anteverted nares and low-hanging columella, thin upper lip, long philtrum, downturned corners of the mouth, overlapping toes, thoracic kyphosis and winged scapulae with posterior protrusion of the superomedial left scapula and acromioclavicular region, flat feet with overlapping toes and osteochondromas located on the internal side of the foot (Figure 1). MRI revealed non-expansile osteochondromas at the right humeral head and scapula; radiographs confirmed bilateral hip dysplasia and additional osteochondromas (Figure 3). A new distal right clavicle fracture was documented. A lower-limb length discrepancy was present (right femur 28 cm; left 25.5 cm).

Figure 3.

Imaging at age 5: (A) Left femur/tibia/fibula X-ray with sessile osteochondromas; (B) right tibia/fibula X-ray (comminuted distal right femur fracture shown); (C) MRI, medial border of left scapula; (D) MRI, head of left humerus and lateral left scapula.

Given her history of frequent fractures, an osteogenesis imperfecta and bone-fragility panel was performed to rule out osteogenesis imperfecta. The results confirmed a pathogenic TNFRSF11B deletion within the 8q-deleted interval and identified a maternal LRP5 variant of uncertain significance (VUS) without clinical evidence of osteopetrosis. A composite genetic diagnosis of Langer–Giedion syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome type 4, and hereditary multiple osteochondromas with mosaic 8q23.1–q24.12 deletion was established. Subsequent metabolic evaluation showed serum calcium, 25-hydroxy-vitamin D, osteocalcin, urine creatinine, and bone turnover markers (NTx) all within reference ranges. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA; Hologic Horizon Apex 5.5.31) revealed lumbar spine (L1–L4) bone mineral density = 0.375 g/cm2, Z = −2.6.

3. Management and Follow-Up

Given her fracture history and low bone mineral density, the patient’s mother provided consent for the off-label use of pamidronate therapy. Treatment was initiated at 1 mg/kg every four months, along with vitamin D3 supplementation in accordance with pediatric bone-health protocols. The management plan includes annual DEXA scanning, ongoing fracture surveillance, and orthopedic follow-up for monitoring of osteochondromas. The patient has remained fracture-free for 12 months since initiation of bisphosphonate therapy.

4. Discussion

4.1. Genotype–Phenotype Correlation: The Unique Complex Architecture

Unlike classic Langer–Giedion syndrome (LGS), which typically results from simple interstitial deletions, our patient presents with a complex chromosomal rearrangement consisting of a central 13.01 Mb deletion flanked by two large duplications. This “duplication-deletion-duplication” architecture is distinct from previously reported 8q deletions and likely stems from a complex post-zygotic replicative error, given the mosaic distribution. While the phenotype is driven primarily by the haploinsufficiency of the deleted genes (TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21), the contribution of the flanking trisomic regions (duplications) to the atypical features cannot be ruled out, making this a genotypically unique entry in the 8q deletion spectrum.

Deletions in the 8q23.1–q24.12 region produce a complex phenotypic spectrum ranging from LGS to Cornelia de Lange syndrome type 4 (CdLS-4) [3,19]. As summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, the extent of phenotypic overlap is largely dictated by the deletion size, gene content, and specific genetic architecture. Classic LGS/TRPS II is characterized by sparse hair, distinctive facial dysmorphism, multiple exostoses, short stature, and mild-to-moderate intellectual disability. The core genotype involves contiguous deletions of TRPS1, EXT1, and RAD21 [2,3], with the minimal critical region estimated at approximately 3.2 Mb [3]. Larger deletions generally correlate with broader clinical involvement, including more pronounced intellectual disability and congenital anomalies [2,3].

The interaction between these loci creates a blended phenotype. Overlapping features are observed when deletions encompass the critical regions for both LGS and CdLS-4—specifically TRPS1, EXT1, and RAD21—resulting in combined skeletal, ectodermal, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities [18,19,23]. Cases deleting EXT1 and RAD21 but sparing TRPS1 may exhibit a mild LGS-like phenotype combined with CdLS-4 traits, suggesting potential disruption of TRPS1 regulatory domains [24]. Conversely, when RAD21 is preserved, CdLS features are typically absent even when TRPS1 and EXT1 are lost [28]. Furthermore, complex rearrangements, including chromothripsis, can generate atypical syndromes that complicate genotype–phenotype interpretation [23].

Finally, additional genes within the 8q23.1–q24.12 interval—such as KCNQ3 and CSMD3—may contribute to neurological and central nervous system manifestations [19,21]. Atypical findings, including coccygeal agenesis, osteoporosis, and endocrine abnormalities, have been reported in larger or more complex deletions, emphasizing that both the extent and content of the chromosomal loss influence the final phenotype [18,24].

Table 2.

Genotype–Phenotype Correlations. Comparison of case reports and studies involving deletions, including at least one gene that is responsible for our combined phenotype.

Table 2.

Genotype–Phenotype Correlations. Comparison of case reports and studies involving deletions, including at least one gene that is responsible for our combined phenotype.

| Reference | Genotype (Deleted Genes, Region, Size) | Clinical Features (LGS/TRPS II) | Clinical Features (CdLS-4) | Overlapping or Additional Features | Fracture History and Bisphosphonate Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our patient | 13.01 Mb; 8q23.1–q24.12 deletion; TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21, 9 other genes with OMIM phenotypes | Protruding ears, bulbous nose, prominent philtrum, exostoses of ribs and scapulae, fracture risk | Synophrys, thin upper lip, polydactyly | Short stature, microcephaly, broad nasal bridge, multiple exostoses | Frequent fractures of long bones; subsequently treated with Pamidronate. |

| Chen et al., 2013 [19] | 8q23.3–q24.22 deletion; TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21, KCNQ3; size not specified (large) | Lax skin/joints, sparse hair, facial dysmorphism, multiple exostoses, scoliosis | Intellectual disability, epilepsy, cardiovascular defects | Gastroesophageal reflux, previously misdiagnosed as Ehlers–Danlos; overlap of LGS and CdLS-4 features | No reported fracture |

| Favilla et al., 2022 [3] | 3.2 Mb (smallest reported for classic LGS); 8q23–q24 deletion; TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21, ±CSMD3 | Exostoses, facial dysmorphism, skeletal anomalies, intellectual disability (variable) | CNS anomalies (if CSMD3 deleted) | Facial and bone anomalies most frequent; CNS anomalies possible with larger deletions | No reported fracture |

| Pereza et al., 2015 [29] | 7.5 Mb (8q23.3–q24.13); EXT1, RAD21, 30 other genes (not TRPS1) | Mild LGS phenotype (skeletal/facial features, exostoses) | CdLS-4 features due to RAD21 deletion | Suggests revision of diagnosis to CdLS-4; overlap with LGS phenotype | No reported fracture |

| Lei et al., 2020 [23] | Complex chromothripsis; loss of RAD21, EXT1 | Bone abnormality, facial dysmorphism (atypical LGS) | CdLS-4 features (intellectual disability, facial features) | Contiguous gene syndrome with both LGS and CdLS-4 | No reported fracture |

| Cappuccio et al., 2014 [18] | 8q23.3–q24.1 deletion; TRPS1, EXT1, likely RAD21 | Intellectual disability, short stature, microcephaly, facial dysmorphism, exostoses, osteoporosis | CNS malformations, pituitary hypoplasia | Atypical findings: coccyx agenesis, osteoporosis, hyperreninemia | Osteoporosis and increased fracture risk noted; bisphosphonate use not specified |

| Shanske et al., 2008 [30] | 19.79 Mb (8q22.3–q24.13, mosaic); TRPS1, EXT1, likely RAD21, 50 genes/loci | Mild facial features, cone-shaped epiphyses, exostoses, short stature | intellectual disability (if deletion extends beyond TRPS1/EXT1) | Degree of mosaicism affects severity | No reported fracture |

| Pereza et al., 2012 [24] | 7.5 Mb (8q23.3–q24.13); EXT1, RAD21, not TRPS1 | LGS phenotype (facial/skeletal features, exostoses), normal height, mild developmental delay | Not classic CdLS-4, but possible overlap if RAD21 deleted | Dyslalia, premature adrenarche; variable phenotype | No reported fracture |

| Lüdecke et al., 1999 [2] | Shortest region of overlap: 8q24.1; TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21, EIF3S3, OPG, CXIV | LGS features (TRPS1, EXT1), variable phenotype | CdLS-4 features (RAD21) | Clinical variability due to additional genes | No reported fracture |

| Nardmann et al., 1997 [31] | ~5 Mb (TRPS I); larger in TRPS II; TRPS1, EXT1, additional genes | TRPS I: normal intelligence; TRPS II: intellectual disability if >5 Mb | Not specified | Parental origin of deletion studied | No reported fracture |

| Carvalho et al., 2011 [32] | 8q23.1–q24.12 deletion; TRPS1, EXT1, possible others | LGS with bilateral tibial hemimelia | Not specified | Suggests additional gene(s) in region may influence limb development | No reported fracture |

| Schinzel et al., 2013 [28] | 8q24.11–q24.13 deletion; EXT1, TRPS1 | Ectodermal dysplasia, cone-shaped epiphyses, exostoses, mild intellectual impairment | Seizures, borderline cognitive delay | Joint stiffness/laxity, growth hormone/TSH deficiency, gynecomastia, vaginal atresia | Joint laxity and instability may predispose to trauma/fractures; no reported fracture |

| Kaur et al., 2023 [20] | Variable; NIPBL, SMC1A, SMC3, HDAC8, RAD21, others | Not applicable | Growth/developmental delay, limb involvement, hypertrichosis, cardiac/GI/craniofacial features | RAD21 variants cause milder CdLS phenotype | No reported fracture |

| Abarca-Barriga et al., 2023 [33] | Intragenic heterozygous deletion in RAD21 (exons 9–14) | Not applicable | Microcephaly, cleft palate, polydactyly, short stature, triangular facies, frontal bossing, bulbous nose, overfolded helix, limited pronosupination, anomalous uterus | No neurodevelopmental disorder at diagnosis; variable expressivity | No reported fracture |

| Maya et al., 2021 [21] | 8q24.13–q24.3 deletions; variable gene content and size | High phenotypic variability; some cases with bone anomalies, some asymptomatic | Some cases with neurodevelopmental delay | No clear association between gene content and fracture risk | Fracture history not systematically reported; bisphosphonate use not described |

4.2. Comparison of Mosaic Cases–The “Mosaic Paradox”: Dissociation of Tissue Severity

Shanske et al. (2008) [30] described the only previously reported mosaic case involving this region: a 14.5-year-old girl with a larger 19.79 Mb interstitial deletion at 8q22.3–q24.13. That deletion encompassed TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21, and approximately 50 other genes. Notably, mosaicism was detected in only 7% of peripheral blood lymphocytes but 97% of skin fibroblasts. Clinically, that patient exhibited mild facial features, classic skeletal manifestations (cone-shaped epiphyses, multiple exostoses, short stature), and mild intellectual disability. The authors proposed that the high level of mosaicism in fibroblasts (ectoderm/mesoderm) explained the classic skeletal phenotype, while the lower burden in other tissues may have attenuated the severity [30].

By comparison, our patient harbors a 13.01 Mb mosaic deletion at 8q23.1–q24.12, involving TRPS1, EXT1, RAD21, and additional genes (including TNFRSF11B and COLEC10). In contrast to the Shanske case, our patient exhibited a significantly higher burden of mosaicism in peripheral blood (~75%). Phenotypically, this correlated with a severe skeletal presentation, including multiple osteochondromas, hip dysplasia, kyphosis, winged scapulae, and the unique history of recurrent fractures. However, despite the large deletion size, which typically predicts severe intellectual disability, her neurodevelopmental profile is relatively preserved; she is bilingual with no global delay, although she exhibits distractibility and reduced speech clarity.

This comparison illustrates a ‘mosaic paradox’ or tissue-specific dissociation. Our patient’s high mosaicism in blood (mesodermal origin) correlates with her severe skeletal/hematologic fragility (‘double hit’ fractures). Conversely, her relative cognitive preservation suggests that the neuroectoderm (brain) may retain a higher proportion of normal cells than the blood, acting as a ‘mosaic rescue’ for neurodevelopment. This aligns with literature suggesting that larger deletions and higher mosaic levels in clinically relevant tissues increase the likelihood of classic TRPS II features, whereas lower levels in specific lineages can attenuate the phenotype [34]. This case underscores that in mosaic 8q syndromes, peripheral blood analysis may accurately predict skeletal severity but underestimate neurodevelopmental potential [3,18,30].

4.3. Skeletal Complications: The “Double Hit” Hypothesis and Therapeutic Targeting

Skeletal complications, including osteoporosis and increased fracture risk, are well recognized in Langer–Giedion syndrome (LGS/TRPS II), particularly among individuals with extensive exostoses and joint laxity [18,28]. Long-term follow-up studies have reported joint instability, trauma proneness, and, in some cases, Perthes disease or vertebral osteomas [28]. However, systematic data on fracture frequency remain limited, and most case reports do not describe bone-specific interventions.

The severity of the fracture history in our patient suggests a synergistic “double hit” mechanism compromising bone integrity. First, haploinsufficiency of TRPS1 impairs chondrocyte differentiation and mineralization, leading to generalized osteopenia (weak material). Second, EXT1 loss results in the formation of osteochondromas. We hypothesize that these exostoses act as biomechanical “stress risers”—focal points of structural weakness—which, when superimposed on a demineralized skeleton, precipitate fractures even with minimal trauma.

This mechanical synergy necessitates the pharmaceutical strengthening provided by bisphosphonates. Notably, Macchiaiolo et al. (2013) [25] reported a patient with TRPS and severe osteoporosis complicated by multiple spontaneous femoral fractures who showed marked improvement in bone mineral density and a complete absence of new fractures following treatment with intravenous neridronate. Consistent with this, our patient’s favorable outcome following pamidronate therapy supports the consideration of bisphosphonates as a viable adjunctive treatment for the management of refractory bone fragility associated with LGS/TRPS II and related contiguous gene syndromes.

4.4. Therapeutic Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first report of bisphosphonate therapy in a patient with this specific mosaic contiguous gene syndrome. The stabilization of bone density and the cessation of fractures in our patient suggest that bisphosphonates are an effective option. However, given the complexity of the condition, we propose this as a bone-specific rescue therapy for patients with refractory fractures, rather than a universal protocol. Furthermore, while the immediate clinical response (fracture cessation) has been positive, long-term follow-up is required to determine if bisphosphonate therapy can significantly improve bone mineral density (Z-scores) in this specific syndrome, or if its primary benefit lies solely in stabilizing bone turnover. In addition, assessment of clinical improvement with bisphosphonate therapy should be pursued in further cases of combined LGS/CdLS with osteoporosis to confirm our observations.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this case expands the phenotypic and genotypic spectrum of chromosome 8q disorders by documenting a novel mosaic complex rearrangement with a unique “duplication-deletion-duplication” architecture. As only the second reported instance of mosaicism in this region, this case highlights a potential “mosaic rescue” effect where tissue-specific mosaicism dissociates skeletal severity from neurodevelopmental outcomes. Most significantly, we report the first successful application of bisphosphonate therapy in a mosaic LGS/CdLS overlap. The patient’s fracture-free interval suggests that pamidronate can be an effective bone-specific intervention for the synergistic “double hit” skeletal pathology seen in this rare subset of patients. While promising, long-term follow-up is warranted to evaluate the sustained efficacy and potential effects on bone mineral density.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes17020175/s1. Supplementary Figure S1: Ensembl GRCh37.p13 export showing (A) the 8q21.2–q23.1 duplication (hg19: 8:85,840,724–107,396,172) with 10% mosaic frequency and (B) the 8q24.12–q24.3 duplication (hg19: 8:120,514,645–146,295,771) with 10% mosaic frequency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and S.D.A.V.; data collection, H.W. and S.D.A.V.; clinical evaluation and supervision, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.A.V.; writing—review and editing, H.W.; figure and table preparation, S.D.A.V.; final approval of the manuscript, H.W. and S.D.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study and its publication are supported by the intramural Grant for Collaborative and Translational Research (GCAT) from Loma Linda University School of Medicine, with the account number PPM#1001276.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This submission is a single-patient clinical case report, not a human subjects research study. No prospective research procedures were conducted, and the report contains only clinical information obtained in the course of routine care. Under the U.S. Common Rule (45 CFR 46), “human subjects research” involves a systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge. A single case report based on routine clinical care does not meet this definition and therefore does not require IRB review at our institution. This determination is consistent with Loma Linda University Health’s Office of Research Affairs policy on Non-Human Subjects Research (https://researchaffairs.llu.edu/research-compliance/human-studies/non-human-subjects-research, accessed on 27 January 2026).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained, from legal guardians for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article and its accompanying table and figures. Additional clinical details are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, in accordance with patient confidentiality regulations.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the patient and their family for their unwavering support and gracious consent to the publication of this case study. The author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, 5.2 version) for language editing and polishing. All AI-assisted edits were reviewed by the authors for factual accuracy, originality, and compliance with ethical publishing standards.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Lüdecke, H.-J.; Johnson, C.; Wagner, M.J.; Wells, D.E.; Turleau, C.; Tommerup, N.; Latos-Bielenska, A.; Sandig, K.-R.; Meinecke, P.; Zabel, B.; et al. Molecular Definition of the Shortest Region of Deletion Overlap in the Langer-Giedion Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1991, 49, 1197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lüdecke, H.-J.; Schmidt, O.; Nardmann, J.; von Holtum, D.; Meinecke, P.; Muenke, M.; Horsthemke, B. Genes and Chromosomal Breakpoints in the Langer-Giedion Syndrome Region on Human Chromosome 8. Hum. Genet. 1999, 105, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favilla, B.P.; Burssed, B.; Yamashiro Coelho, É.M.; Perez, A.B.A.; de Faria Soares, M.d.F.; Meloni, V.A.; Bellucco, F.T.; Melaragno, M.I. Minimal Critical Region and Genes for a Typical Presentation of Langer-Giedion Syndrome. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2022, 162, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukowska-Olech, E.; Trzebiatowska, W.; Czech, W.; Drzymała, O.; Frąk, P.; Klarowski, F.; Kłusek, P.; Szwajkowska, A.; Jamsheer, A. Hereditary Multiple Exostoses—A Review of the Molecular Background, Diagnostics, and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Genet. 2021, 10, 759129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, C.; Nardella, G.; Fischetto, R.; Copetti, M.; Petracca, A.; Annunziata, F.; Augello, B.; D’Asdia, M.C.; Petrucci, S.; Mattina, T.; et al. Mutational Spectrum and Clinical Signatures in 114 Families with Hereditary Multiple Osteochondromas: Insights into Molecular Properties of Selected Exostosin Variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 2133–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, R.; Lin, H.; Wang, H. Insights into the Molecular Regulatory Network of Pathomechanisms in Osteochondroma. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 16362–16369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedion, A.; Burdea, M.; Fruchter, Z.; Meloni, T.; Trosc, V. Autosomal-Dominant Transmission of the Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndrome. Report of 4 Unrelated Families, Review of 60 Cases. Helv. Paediatr. Acta 1973, 28, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Giedion, A. Trichorhinophalangeal Syndrome. In Birth Defects Encyclopedia; Buyse, M.L., Ed.; Blackwell Scientific: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 1710–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke, H.-J.; Schaper, J.; Meinecke, P.; Momeni, P.; Groß, S.; von Holtum, D.; Hirche, H.; Abramowicz, M.; Albrecht, B.; Apacik, C.; et al. Genotypic and Phenotypic Spectrum in Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndrome Types I and III. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccione, M.; Niceta, M.; Antona, V.; Fiore, A.; Cariola, F.; Gentile, M.; Corsello, G. Identification of Two New Mutations in TRPS1 Gene Leading to the Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndrome Type I and III. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149A, 1837–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.M.; Shaw, A.; Bikker, H.; Lüdecke, H.-J.; van der Tuin, K.; Badura-Stronka, M.; Fabia Belligni, E.; Biamino, E.; Bonati, M.T.; Diego, D.; et al. Phenotype and Genotype in 103 Patients with Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 58, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, M.A.; Wilde, J.J.; Albrecht, M.; Dickinson, E.; Tennstedt, S.; Braunholz, D.; Mönnich, M.; Yan, Y.; Xu, W.; Gil-Rodríguez, M.; et al. RAD21 Mutations Cause a Human Cohesinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 1014–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, A.D.; Moss, J.F.; Selicorni, A.; Bisgaard, A.-M.; Deardorff, M.A.; Gillett, P.M.; Ishman, S.L.; Kerr, L.M.; Levin, A.V.; Mulder, P.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: First International Consensus Statement. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannini, L.; Cucco, F.; Quarantotti, V.; Krantz, I.D.; Musio, A. Mutation Spectrum and Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, N.; Pati, D. Cohesin Subunit RAD21: From Biology to Disease. Gene 2020, 758, 144966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, T.H.; Shoichet, S.A.; Latham, P.; Kroll, T.G.; Peters, L.L.; Shivdasani, R.A. Transcriptional Repression and Developmental Functions of the Atypical Vertebrate GATA Protein TRPS1. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierala, D.; Sam, K.; Morello, R.; Zheng, Q.; Munivez, E.; Shivdasani, R.A.; Lee, B. Uncoupling of Chondrocyte Differentiation and Perichondrial Mineralization Underlies the Skeletal Dysplasia in Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 2244–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, G.; Genesio, R.; Ronga, V.; Casertano, A.; Izzo, A.; Riccio, M.P.; Bravaccio, C.; Salerno, M.C.; Nitsch, L.; Andria, G.; et al. Complex Chromosomal Rearrangements Causing Langer-Giedion Syndrome Atypical Phenotype: Genotype-Phenotype Correlation and Literature Review. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2014, 164A, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-P.; Lin, S.-P.; Liu, Y.-P.; Chern, S.-R.; Wu, P.-S.; Su, J.-W.; Chen, Y.-T.; Lee, C.-C.; Wang, W. An Interstitial Deletion of 8q23.3–Q24.22 Associated with Langer-Giedion Syndrome, Cornelia de Lange Syndrome and Epilepsy. Gene 2013, 529, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Blair, J.; Devkota, B.; Fortunato, S.; Clark, D.; Lawrence, A.; Kim, J.; Do, W.; Semeo, B.; Katz, O.; et al. Genomic Analyses in Cornelia de Lange Syndrome and Related Diagnoses: Novel Candidate Genes, Genotype–Phenotype Correlations and Common Mechanisms. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2023, 191, 2113–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, I.; Kahana, S.; Agmon-Fishman, I.; Klein, C.; Matar, R.; Berger, R.; Josefsberg, S.B.Y.; Shohat, M.; Marom, D.; Basel-Salmon, L.; et al. The Phenotype of 15 Cases with Rare 8q24.13–Q24.3 Deletions—A New Syndrome or Still an Enigma? Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2021, 185, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; Dowey, S.; Saul, D.; Cain, C.; Rossiter, J.; Blakemore, K.; Stetten, G. Prenatal Diagnosis of Mosaic Trisomy 8q Studied by Ultrasound, Cytogenetics, and Array-CGH. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2008, 146A, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Liang, D.; Yang, Y.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Katoh, K.; Miyake, N.; Frith, M.C.; Wu, L.; Matsumoto, N. Long-Read DNA Sequencing Fully Characterized Chromothripsis in a Patient with Langer–Giedion Syndrome and Cornelia de Lange Syndrome-4. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 65, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereza, N.; Severinski, S.; Ostojić, S.; Volk, M.; Maver, A.; Dekanić, K.B.; Kapović, M.; Peterlin, B. Third Case of 8q23.3–Q24.13 Deletion in a Patient with Langer-Giedion Syndrome Phenotype without TRPS1 Gene Deletion. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2012, 158A, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchiaiolo, M.; Mennini, M.; Digilio, M.C.; Buonuomo, P.S.; Lepri, F.R.; Gnazzo, M.; Grandin, A.; Angioni, A.; Bartuli, A. Thricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndrome and Severe Osteoporosis: A Rare Association or a Feature? An Effective Therapeutic Approach with Biphosphonates. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2013, 164, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, G.; Barber, G.P.; Benet-Pages, A.; Casper, J.; Clawson, H.; Diekhans, M.; Fischer, C.; Gonzalez, J.N.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Lee, C.M.; et al. The UCSC Genome Browser Database: 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, gkae974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolchik, D. The UCSC Table Browser Data Retrieval Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 493D496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinzel, A.; Riegel, M.; Baumer, A.; Superti-Furga, A.; Moreira, L.M.A.; Santo, L.D.E.; Schiper, P.P.; Henrique, J.; Giedion, A. Long-Term Follow-Up of Four Patients with Langer–Giedion Syndrome: Clinical Course and Complications. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2013, 161, 2216–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereza, N.; Severinski, S.; Ostojić, S.; Volk, M.; Maver, A.; Dekanić, K.B.; Kapović, M.; Peterlin, B. Cornelia de Lange Syndrome Caused by Heterozygous Deletions of Chromosome 8q24: Comments on the Article by Pereza et al. [2012]. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167, 1426–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanske, A.L.; Patel, A.; Saukam, S.; Levy, B.; Lüdecke, H.-J. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of a Patient with Langer-Giedion Syndrome and Mosaic Del(8)(Q22.3q24.13). Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2008, 146A, 3211–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardmann, J.; Tranebjærg, L.; Horsthemke, B.; Lüdecke, H.-J. The Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal Syndromes: Frequency and Parental Origin of 8q Deletions. Hum. Genet. 1997, 99, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.R.; Lima, C.; Dulce, M.; Speck-Martins, C.E. Tibial Hemimelia in Langer–Giedion Syndrome with 8q23.1–Q24.12 Interstitial Deletion. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 2784–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca-Barriga, H.H.; Punil Luciano, R.; Vásquez Sotomayor, F. Cornelia de Lange Syndrome Caused by an Intragenic Heterozygous Deletion in RAD21 Detected Through Very-High-Resolution Chromosomal Microarray Analysis. Genes 2023, 14, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truty, R.; Rojahn, S.; Ouyang, K.; Kautzer, C.; Kennemer, M.; Pineda-Alvarez, D.; Johnson, B.; Stafford, A.; Basel-Salmon, L.; Saitta, S.; et al. Patterns of Mosaicism for Sequence and Copy-Number Variants Discovered Through Clinical Deep Sequencing of Disease-Related Genes in One Million Individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.