VPS35 Deficiency Markedly Reduces the Proliferation of HEK293 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

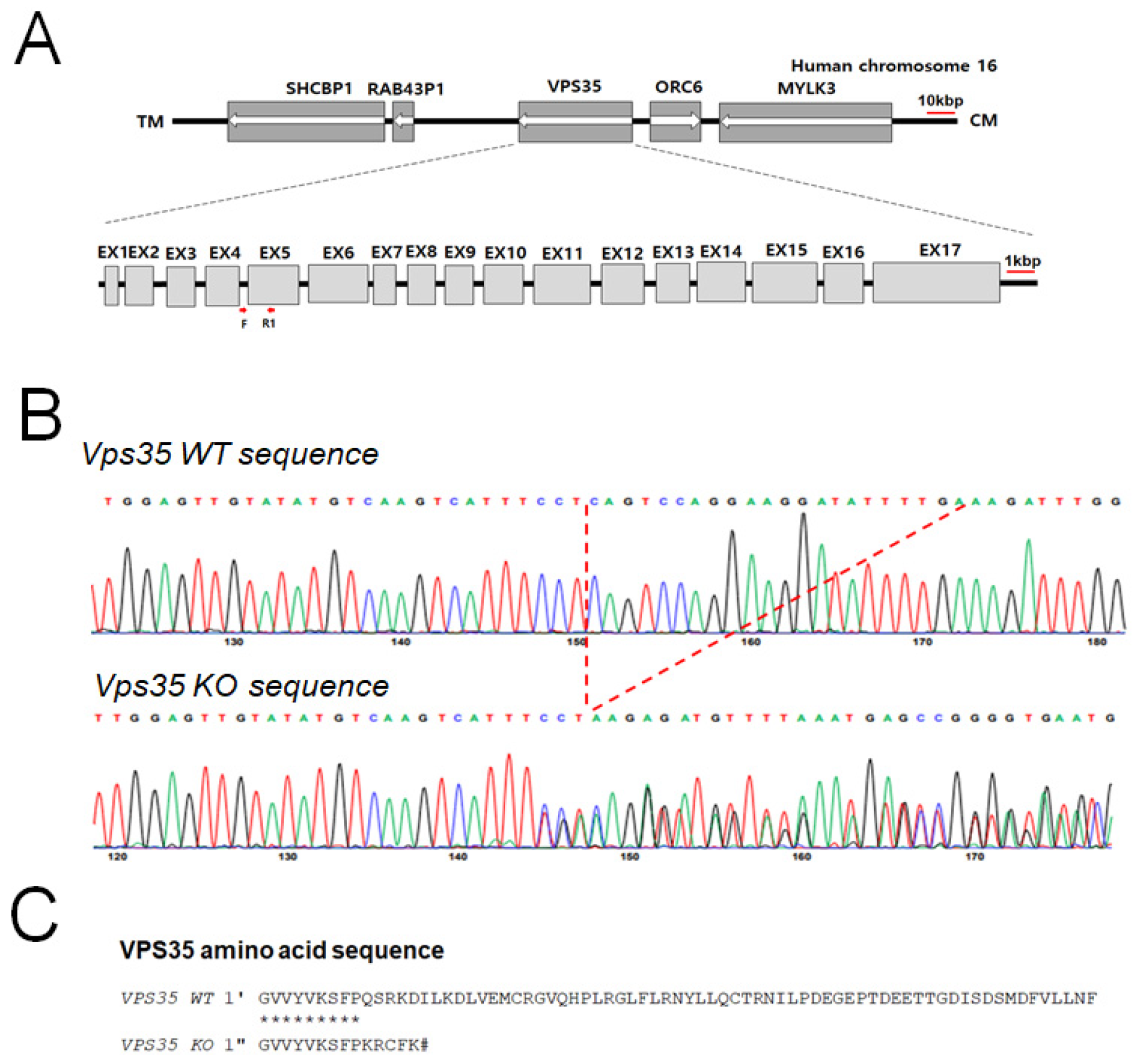

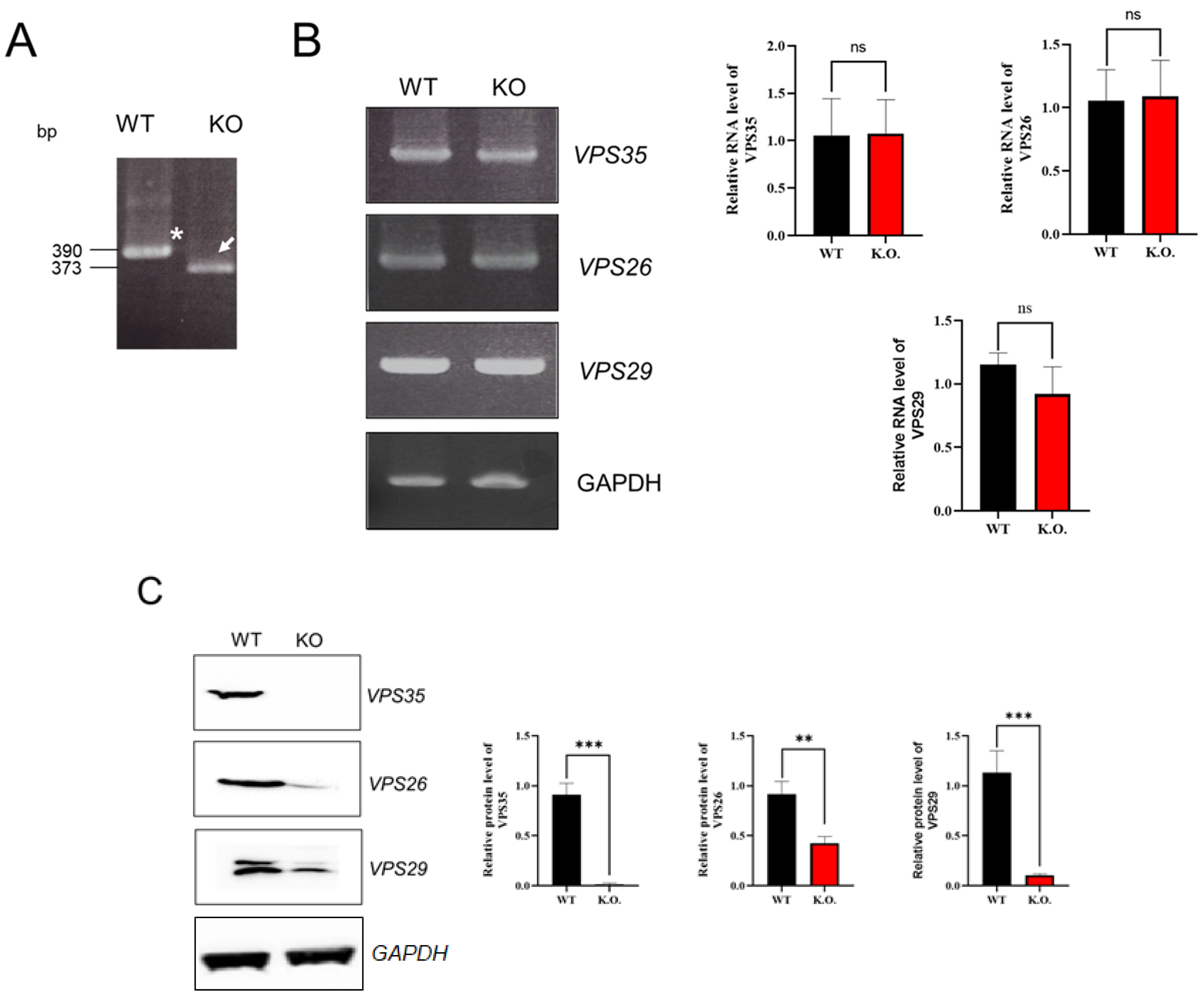

2.2. Establishment and Characterization of the VPS35-Deficient HEK293 Cell Line

2.3. RT-PCR Analysis

2.4. Preparation of Protein

2.5. Antibodies

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. Imaging Mitochondrial Morphology

2.8. Rescue Experiment

2.9. Statistical Analysis

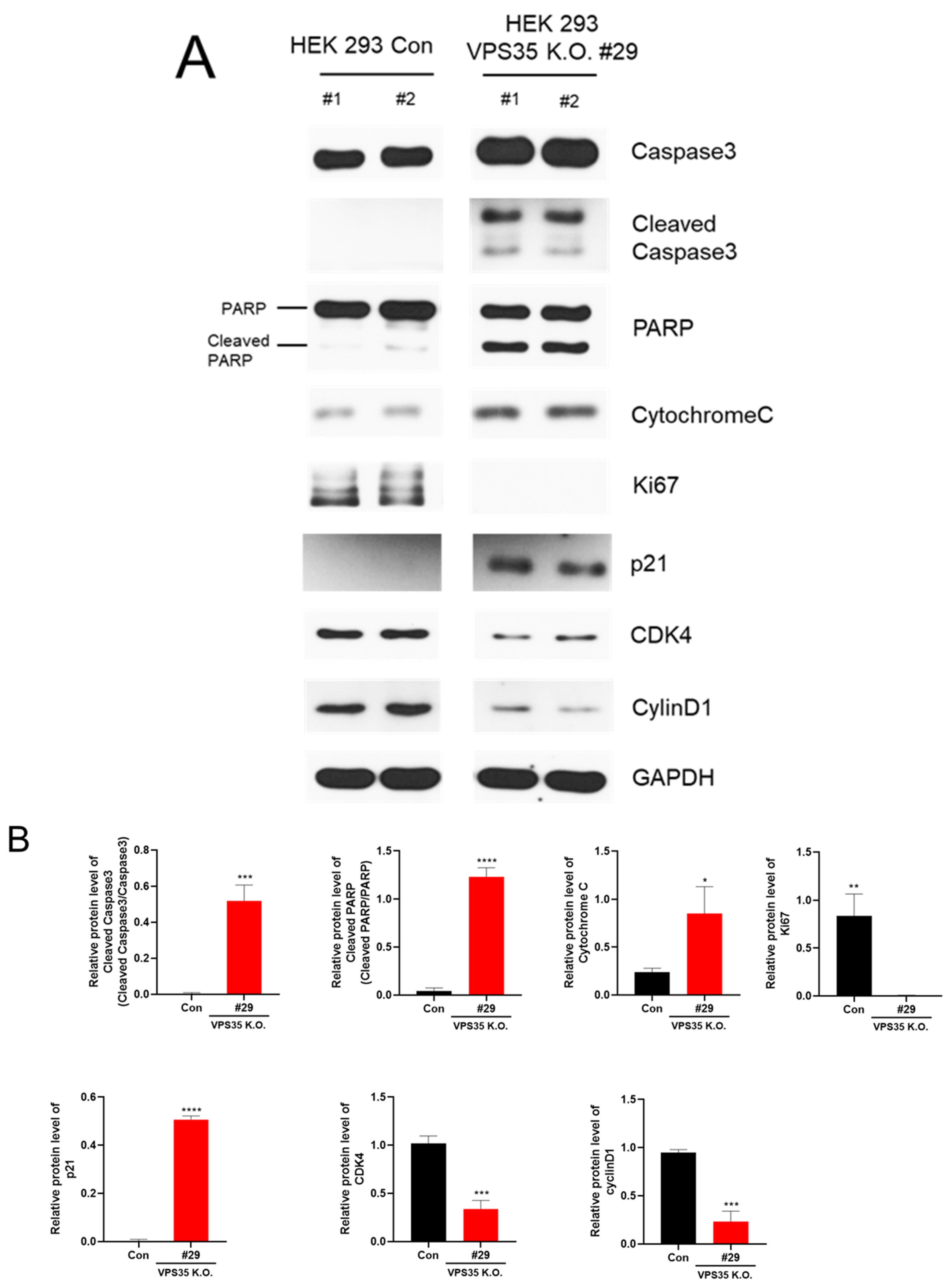

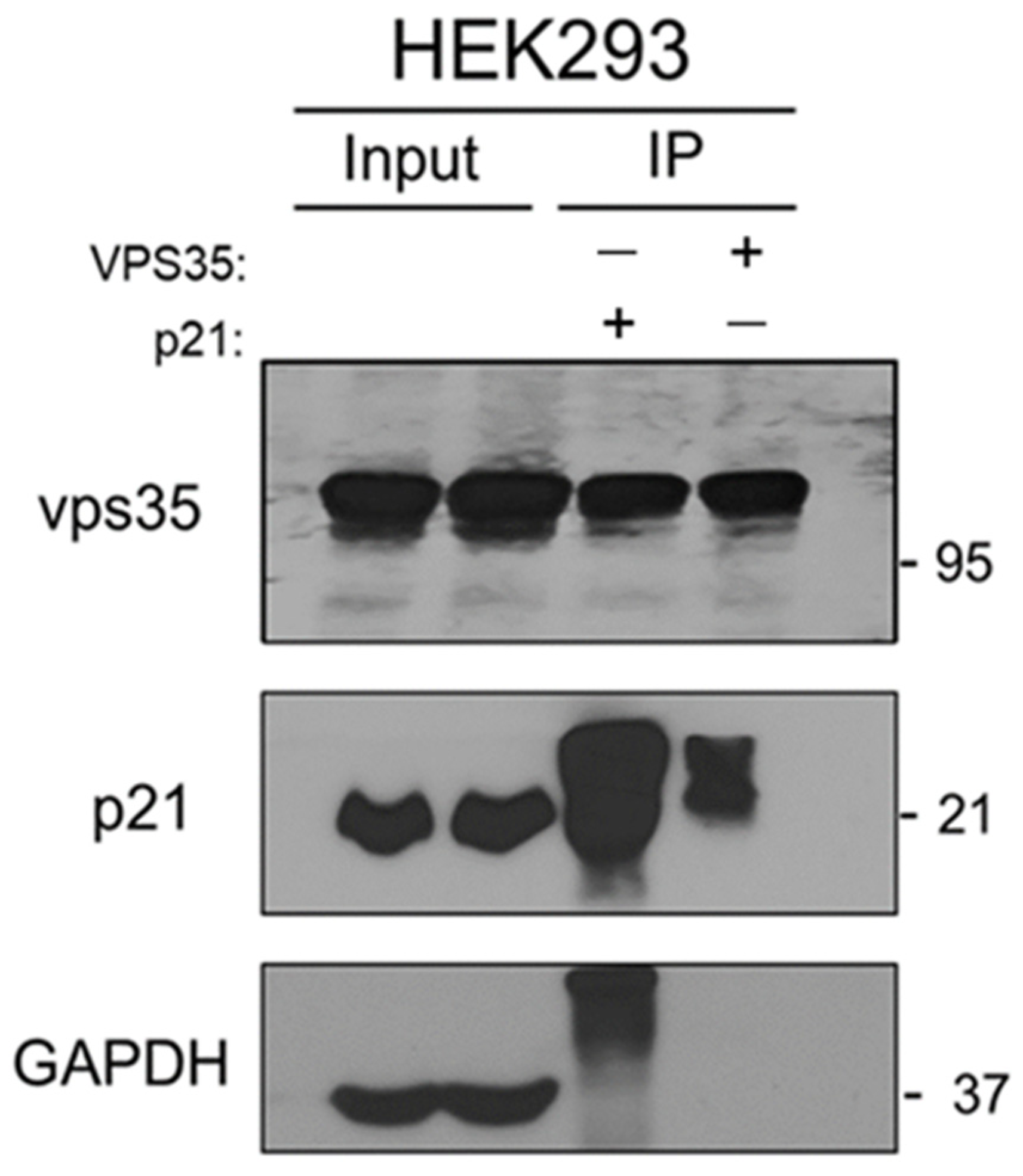

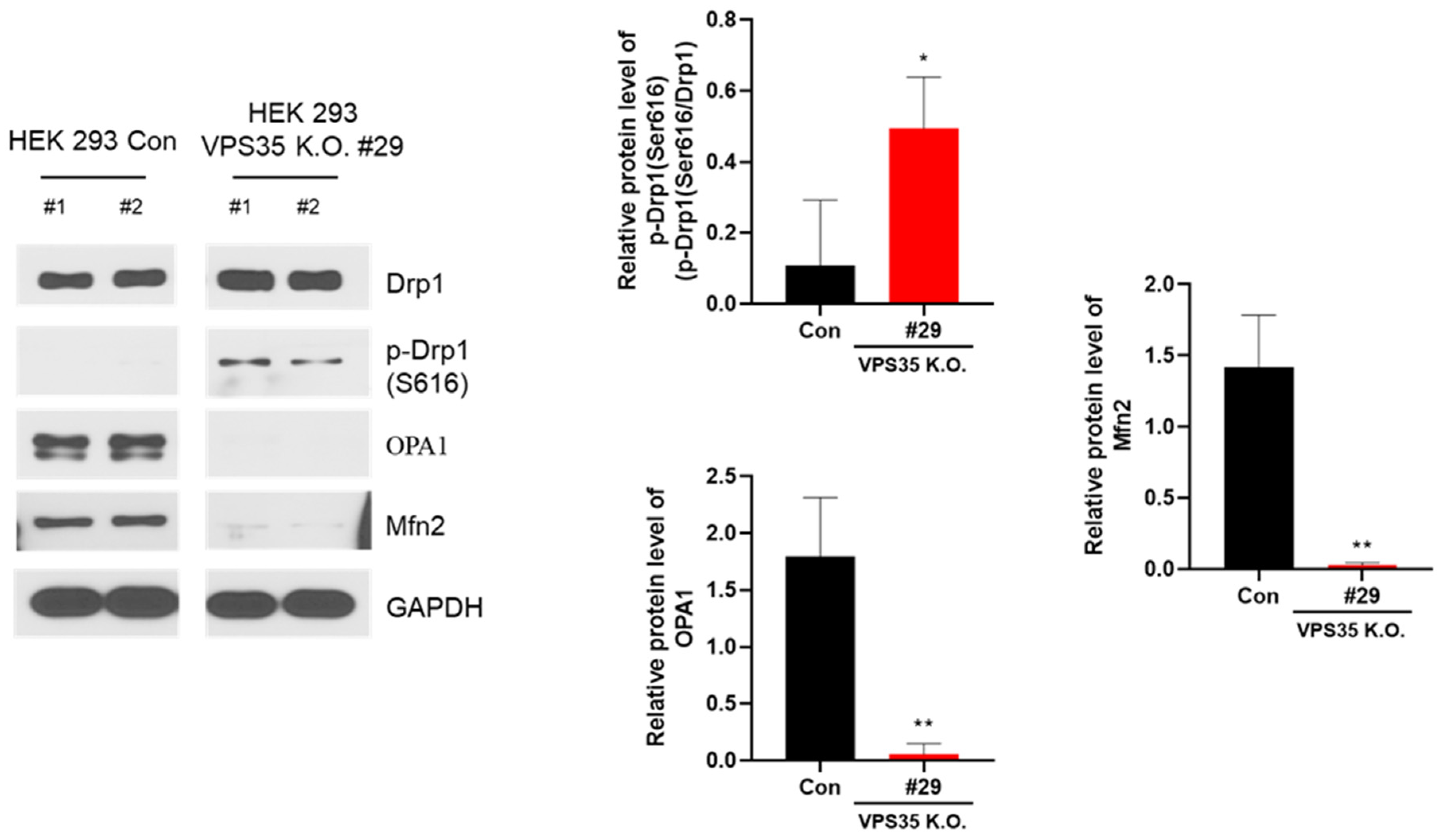

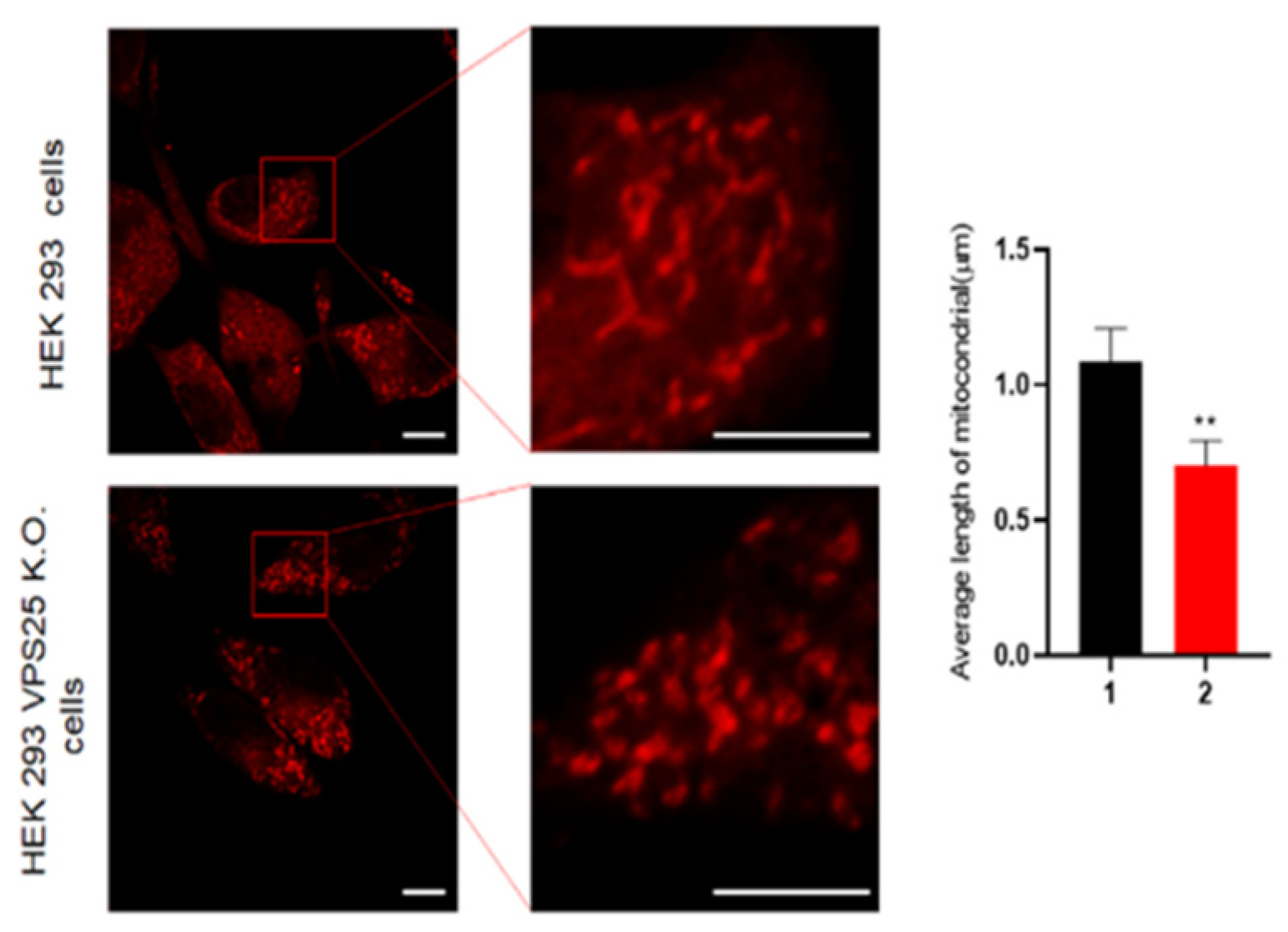

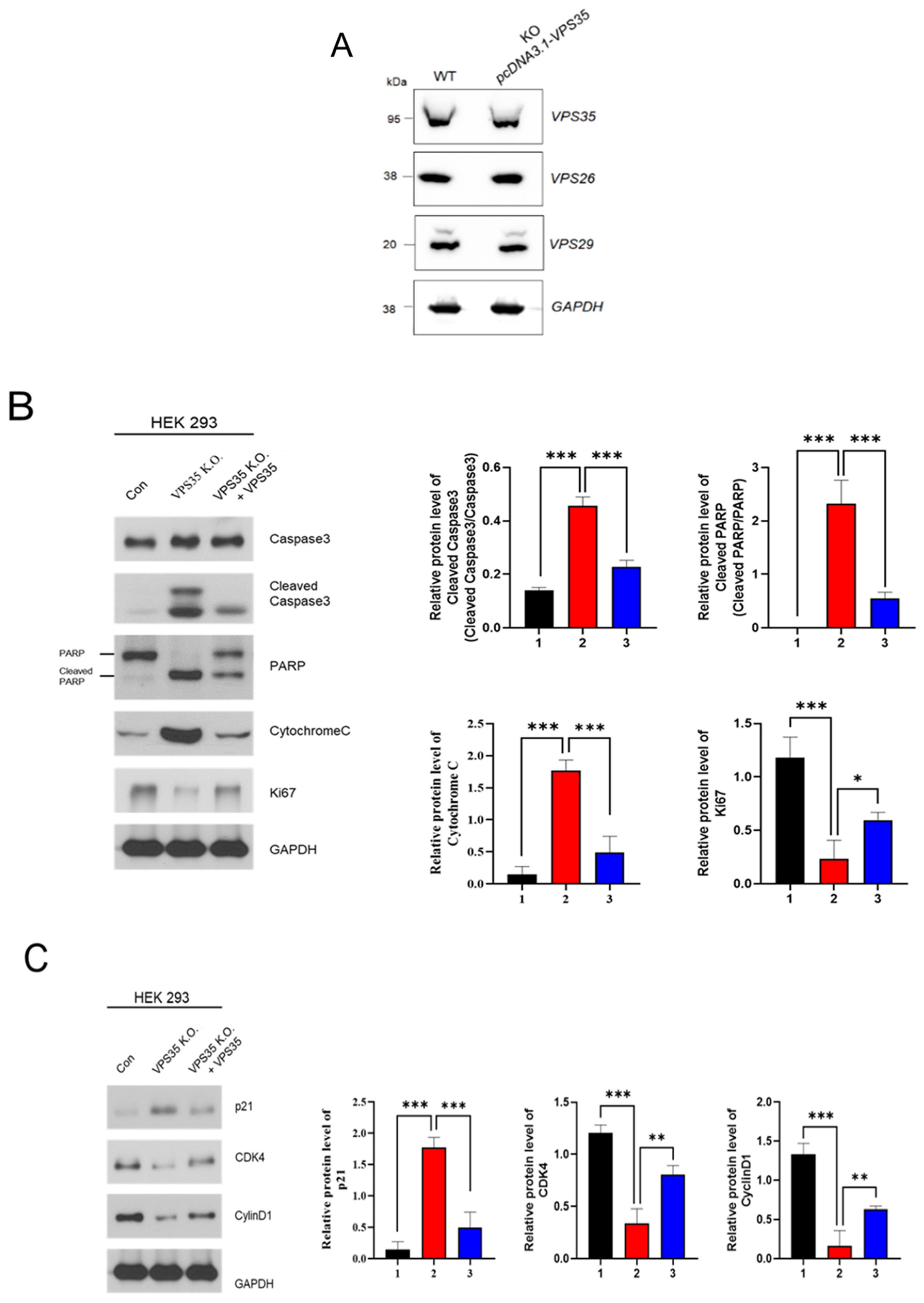

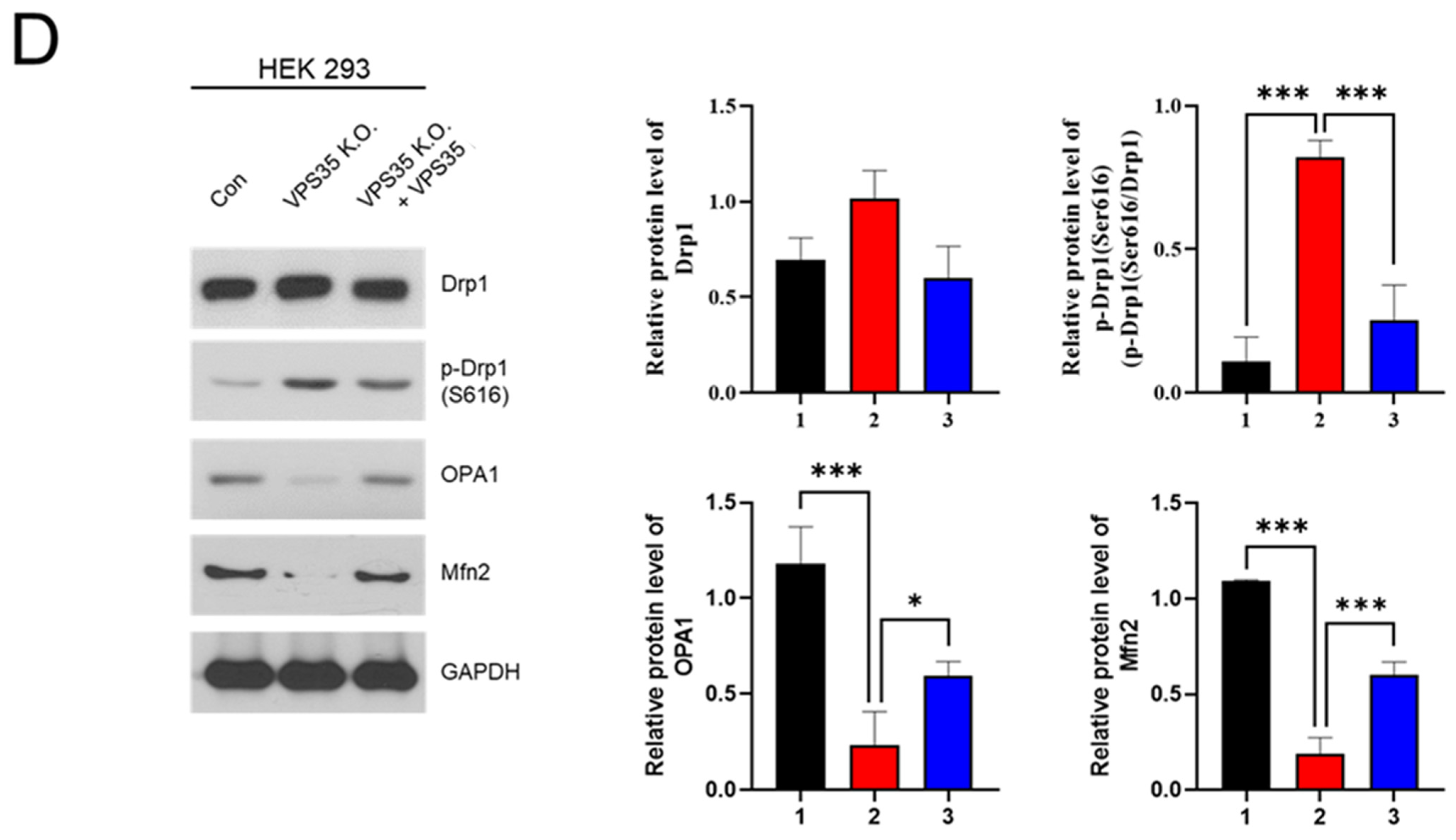

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| HEK | Human embryonic kidney |

| KO | Knockout |

| OPA1 | Optic atrophy 1 |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling |

| VPS | Vacuolar protein sorting |

| WT | Wild-type |

References

- Brenner, S. Twisted strands. Nature 1998, 395, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirokawa, N.; Noda, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Niwa, S. Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, A.; Goldstein, L.S. Principles of cargo attachment to cytoplasmic motor proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002, 14, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, A.S.; Seaman, M.N. Retromer-mediated endosomal protein sorting: The role of unstructured domains. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2620–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, S.A.; Petsko, G.A. Retromer in Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease and other neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.; Hierro, A. Retromer. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R687–R689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, C.; Cullen, P.J. Retromer: A master conductor of endosome sorting. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Radice, G.; Perkins, C.P.; Costantini, F. Identification and characterization of a novel, evolutionarily conserved gene disrupted by the murine H beta 58 embryonic lethal transgene insertion. Development 1992, 115, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arighi, C.N.; Hartnell, L.M.; Aguilar, R.C.; Haft, C.R.; Bonifacino, J.S. Role of the mammalian retromer in sorting of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 165, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchitsu, Y.; Mukai, K.; Uematsu, R.; Takaada, Y.; Shinojima, A.; Shindo, R.; Shoji, T.; Hamano, S.; Ogawa, E.; Sato, R.; et al. STING signalling is terminated through ESCRT-dependent microautophagy of vesicles originating from recycling endosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lee, K.H.; Follett, J.; Wabitsch, M.; Hamilton, A.N.; Collins, M.B.; Bugarcic, A.; Teasdale, D.R. Functional characterization of retromer in GLUT4 storage vesicle formation and adipocyte differentiation. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, J.W.; Baek, D.C.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.H.; Imakawa, K.; Chang, K.T. Identification of novel retromer complexes in the mouse testis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 375, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Song, B.S.; Huh, J.W.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, S.H.; Hong, Y.; et al. Implication of mouse Vps26b-Vps29-Vps35 retromer complex in sortilin trafficking. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 403, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banos-Mateos, S.; Rojas, A.L.; Hierro, A. VPS29, a tweak tool of endosomal recycling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2019, 59, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Feng, H.; Sang, Q.; Li, F.; Chen, M.; Yu, B.; Xu, Z.; Pan, T.; Wu, X.; Hou, J.; et al. VPS35 promotes cell proliferation via EGFR recycling and enhances EGFR inhibitors response in gastric cancer. EBioMedicine 2023, 89, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Li, Z.; Teasdale, R.D. Multifaceted roles of retromer in EGFR trafficking and signaling activation. Cells 2022, 11, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wang, T.; Du, J.; Hong, Y.; Yang, C.P.; Xiao, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, H.; Deng, Z.H. ITRAQ-based quantitatibe proteomic analysis reveals that VPS35 promotes the expression of MCM2-7 genes in HeLa cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Monani, U.R. Glut1 deficiency syndrome: New and emerging insights into a prototypical brain energy failure disorder. Neurosci. Insights 2021, 16, 26331055211011507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Sun, X.J.; Xiu, S.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, Z.Q.; Gu, Y.L.; Yi, C.X.; Liu, J.Y.; Dai, Y.S.; Yuan, X.; et al. Frizzled receptors (FZDs) in Wnt signaling: Potential therapeutic targets for human cancers. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1556–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, R.; Manzoor, M.; Hussain, A. Wnt signaling pathway: A comprehensive review. Cell Biol. Int. 2022, 46, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulski, J.; Ross, O.A.; Wszolek, Z.K. VPS35-Related Parkinson Disease. In GeneReviews; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.A.; Morrison, B.E. Contributions of VPS35 Mutations to Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroscience 2019, 401, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Tang, F.L.; Hong, Y.; Luo, S.W.; Wang, C.L.; He, W.; Shen, C.; Jung, J.U.; Xiong, F.; Lee, D.; et al. VPS35 haploinsufficiency increases Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 195, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Fan, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, D.; Zhu, L. Intermittent hypoxia training enhances Abeta endocytosis by plaque associated microglia via VPS35-dependent TREM2 recycling in murine Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Song, Y.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Jung, Y.; Park, Y.H.; Song, B.S.; Eom, T.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Development of a New Type of Recombinant Hyaluronidase Using a Hexahistidine; Possibilities and Challenges in Commercialization. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Lee, S.; Jeong, P.S.; Seol, D.W.; Son, D.; Kim, Y.H.; Song, B.S.; Sim, B.W.; Park, S.; Lee, D.M.; et al. Hyaluronidase 6 Does Not Affect Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Dispersal and Male Mice Fertility. Genes 2022, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Wang, X.D.; Jang, S.; Yu, Y. PARP1 nhibitors induce pyroptosis via caspase 3-mediated gasdermin E cleavage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 646, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.L.; Liu, W.; Hu, J.X.; Erion, J.R.; Ye, J.; Mei, L.; Xiong, W.C. VPS35 Deficiency or Mutation Causes Dopaminergic Neuronal Loss by Impairing Mitochondrial Fusion and Function. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, P.; Conceicao, D.V.; Sun, Y.; Ahamad, N.; Saraiva, R.L.; Selvaraj, S.; Singh, B.B. Calcium signaling regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cells 2021, 10, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, J.; Schwab, U.; Lemke, H.; Stein, H. Production of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with a human nuclear antigen associated with cell proliferation. Int. J. Cancer 1983, 31, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Shin, G.Y.; Qiu, H. The Role of Cell Cycle Regulators in Cell Survival-Dual Functions of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 20 and p21(Cip1/Waf1). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.Z.; Chung, H.L.; Shih, C.; Wong, K.K.L.; Dutta, D.; Nil, Z.; Burns, C.G.; Kanca, O.; Park, Y.J.; Zuo, Z.; et al. Cdk8/CDK19 promotes mitochondrial fission through Drp1 phosphorylation and can phenotypically suppress pink1 deficiency in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.J.; Tsai, C.Y.; Chiou, S.J.; Lai, Y.L.; Wang, C.H.; Cheng, J.T.; Chuang, T.H.; Huang, C.F.; Kwan, A.L.; Loh, J.K.; et al. The Phosphorylation Status of Drp1-Ser637 by PKA in Mitochondrial Fission Modulates Mitophagy via PINK1/Parkin to Exert Multipolar Spindles Assembly during Mitosis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N.; Ishihara, N.; Jofuku, A.; Oka, T.; Mihara, K. Mitotic phosphorylation of dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 participates in mitochondrial fission. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11521–11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanfardino, P.; Amati, A.; Perrone, M.; Petruzzella, V. The balance of MFN2 and OPA1 in mitochondrial dynamics, cellular homeostasis and disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C.; Martin, J.S. Mitochondrial fission/fusion dynamics and apoptosis. Mitochondrion 2010, 10, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Park, S.; Bang, H.; Kim, S.-U.; Park, Y.-H.; Wee, G.; Chae, U.; Kim, E. VPS35 Deficiency Markedly Reduces the Proliferation of HEK293 Cells. Genes 2026, 17, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020177

Lee S, Park S, Bang H, Kim S-U, Park Y-H, Wee G, Chae U, Kim E. VPS35 Deficiency Markedly Reduces the Proliferation of HEK293 Cells. Genes. 2026; 17(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020177

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sujin, Soojin Park, Hyewon Bang, Sun-Uk Kim, Young-Ho Park, Gabbine Wee, Unbin Chae, and Ekyune Kim. 2026. "VPS35 Deficiency Markedly Reduces the Proliferation of HEK293 Cells" Genes 17, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020177

APA StyleLee, S., Park, S., Bang, H., Kim, S.-U., Park, Y.-H., Wee, G., Chae, U., & Kim, E. (2026). VPS35 Deficiency Markedly Reduces the Proliferation of HEK293 Cells. Genes, 17(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17020177