Abstract

Background: Semisulcospiridae is a family of freshwater gastropods with over 100 species, primarily distributed in East Asia and North America. They play crucial ecological roles and are of medical importance as intermediate hosts for parasites. However, their phylogenetic relationship remains unclear. Most previous studies, which focused on fewer molecular markers (e.g., COI, 16S, 28S), have shown limitations in resolving relationships with low resolution. Mitochondrial genomes, with their richer phylogenetic information, offer a promising tool to infer the evolutionary relationships within this family. Methods: This study sequenced, assembled, and annotated the complete mitochondrial genomes of three Semisulcospiridae species from China: Koreoleptoxis friniana, Hua textrix, and Hua yangi. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods on five distinct datasets derived from the mitochondrial genomes, including nucleotide sequences of protein-coding genes (with and without third codon positions), amino acid sequences, and combinations with two ribosomal RNA genes. Results: The complete (or near-complete) mitochondrial genomes of K. friniana, H. textrix, and H. yangi were 15,474 bp, 15,660 bp, and 15,744 bp in length, respectively, showing typical gene content and an A+T bias. The gene order was highly conserved. Phylogenetic analyses consistently recovered the family Semisulcospiridae as monophyletic and revealed three well-supported, distinct clades corresponding to the genera Semisulcospira, Koreoleptoxis, and Hua. While the overall tree topologies were robust for Semisulcospiridae, some incongruences were observed in the placements of other cerithioidean families depending on the dataset used. Evolutionary rate analysis (Ka/Ks) indicated strong purifying selection across all protein-coding genes, with COX1 being the most conserved. Conclusions: This study provided three new mitochondrial genomes for Semisulcospiridae: K. friniana, H. textrix, and H. yangi. Phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial genome datasets offers new evidence that supports the monophyly of the three Asian genera of Semisulcospiridae. Future research should include broader taxonomic sampling, particularly of the North American genus Juga and the atypical Japanese Semisulcospira lineages, to achieve a comprehensive phylogenetic framework.

1. Introduction

Semisulcospiridae Morrison, 1952 is a family of freshwater gastropods, comprising over 100 species from four genera [1]. The members of this family are mainly distributed in East Asia and North America, with the majority (over 60 species of three genera) recorded in China [2,3]. They inhabit various freshwater bodies, including rivers, lakes, streams, and springs [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Semisulcospirids have attracted considerable research interest due to their important ecological roles and their role as intermediate hosts of human pathogens [3,5,6,7,8]. For instance, many semisulcospirids prefer clean, well-oxygenated waters, making them useful indicators of environmental quality [3,6,7]. Moreover, several species serve as intermediate hosts for medically significant trematodes [9,10,11]. Given their ecological and medical significance, a comprehensive understanding of their phylogenetic relationships is crucial [5,6].

Currently, there are four genera recognized under Semisulcospiridae. Hua S.-F. Chen, 1943, Koreoleptoxis J. B. Burch & Y. Jung, 1988, and Semisulcospira O. Boettger, 1886 are distributed in Asia and Juga H. Adams & A. Adams, 1854 in America [5,12]. Semisulcospira and Koreoleptoxis are mainly distributed in the northern and central regions of China, and Hua is distributed in the southwest of China [2,5]. The genus Semisulcospira is distinguished from other genera by its reproductive mode, because it is the only viviparous species in Semisulcospiridae. Koreoleptoxis and Hua can be distinguished by their female reproductive organs: female Hua species have an egg-laying groove or an ovipositor under the left tentacle, while Koreoleptoxis has both structures [2]. There are at least 13 species of Koreoleptoxis recorded in China, and almost all species of Hua are recorded in and endemic to China, except H. jacqueti, which is also recorded in Vietnam [2,13]

The phylogenetic relationships within Semisulcospiridae remain unresolved. Strong and Köhler [13] were the first to revise the taxonomy of this family using both morphological characteristics and molecular evidence. Köhler [6,7] subsequently provided comprehensive systematic treatments of Semisulcospira species from Japan and Korea, and Du et al. (2019a, 2019b, 2023) further investigated the phylogeny of Chinese semisulcospirids [2,4,5]. However, these studies relied mainly on a limited number of mitochondrial and nuclear markers, such as partial COI, 16S rRNA, and 28S rRNA genes. Three genera, Juga, Hua, and Koreoleptoxis, are generally monophyletic according to the phylogenetic trees based on those molecular markers [4,5,12,14], while the phylogenetic position of Semisulcospira is still in mystery. However, the problems mentioned above suggest that traditionally used molecular markers showed limitations in solving the phylogeny of Semisulcospiridae. Therefore, more methods have been applied to solve this question. Sawada and Fuke [15] imported genome-wide SNPs and have been successful in resolving the systematic relationships of the Japanese semisulcospirids [15,16,17,18,19]. Xu et al. [14,18] applied mitochondrial genomes in the phylogenetics of Semisulcospiridae with the description of a new species.

Animal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a cornerstone molecular marker in evolutionary biology. This compact, circular genome, typically 14–20 kb in length, encodes 37 genes, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), two ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) [20]. Its maternal inheritance, lack of recombination, and relatively high evolutionary rate have made it indispensable for studies in species identification, population genetics, and phylogenetic reconstruction across diverse taxonomic scales [21]. Therefore, we believe that more comprehensive sampling may help to clarify the phylogenetic relationships of Semisulcospiridae.

So far, the mitochondrial genome data of Semisulcospiridae reported in NCBI only include eight different species from three genera (four of Semisulcospira, three of Koreoleptoxis, and only one of Hua). In this study, we reported another three species from two genera of Semisulcospiridae from China: K. friniana (Heude, 1888 [22]), H. textrix (Heude, 1889 [23]), and H. yangi (Du et al., 2023 [2]). The former is common in the Southeast of China, sometimes consumed as food by local people, and the latter two species are endemic to China. We hope that studying the mitochondrial genome data of these species will improve our understanding of the phylogeny of Semisulcospiridae and thereby assist with research in conservation biology, ecology, and public health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection, Identification, and Sequencing

The sequenced specimen was collected from freshwater bodies in China. The specimen was fixed in ethanol (≥95%), preserved in a −20 °C refrigerator, and finally deposited at the College of the Environment and Ecology, Xiamen University. DNA extraction and library preparation protocols followed the procedures described in Yang et al. [24]. The morphological and molecular information (COI and 16S rRNA, see Supplementary File S2, Table S1) was integrated for species identification. The information of the specimens used in this study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Collect information on three semisulcospirid species.

Identification followed by Heude [22,23], Du et al. [5], Du and Yang [2], and Zeng et al. [25]. Some of the specimens used in this study are the same as those in Zeng et al. [25].

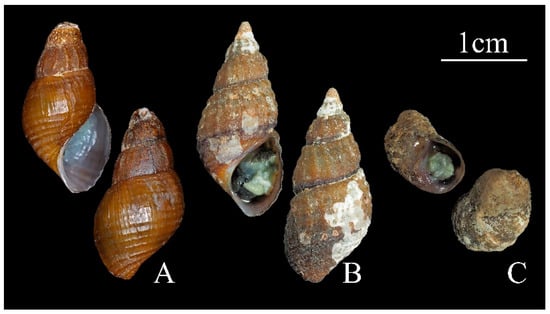

K. friniana (Heude, 1888 [22]), RTM11 (Figure 1A): Shell medium-sized, solid, conical, with seven whorls. Surface brown, with 13–16 spiral lines and 13–15 weak axial ribs crossing each other, forming checkerboard patterns. Apex seriously eroded. The blast results show high identity values (over 99%) with COI sequences of K. friniana (MK969058, MK969049, etc.) [4].

Figure 1.

Specimens sequenced in this study. (A) Koreoleptoxis friniana (Heude, 1888 [22]), RTM11; (B) Hua textrix (Heude, 1889 [23]), SEM-A1; (C) Hua yangi Du et al., 2023 [2], SEM-B1.

H. textrix (Heude, 1888 [22]), SEM-A1 (Figure 1B): Shell medium-sized, solid, conical, with seven whorls. Surface brown, with a dark brown band on the bottom of each whorl, with eight spiral raised lines and 13–16 axial ribs crossing each other, Apex pointed. Aperture ovate. The blast results show high identity values (over 99%) with two COI sequences and two 16S of H. textrix (MK251701, MK969005; MK251613, MK251612) [4,5].

H. yangi Du et al., 2023 [2], SEM-B1 (Figure 1C): Shell small, solid, ovate, with four whorls. Surface brown, smooth, often covered by algae and sediment. Body whorl inflated. Apex blunt. Aperture round. The blast results show high identity values (over 99%) with COI sequences of H. yangi (MK969082, MK969071, etc.) [2,5].

2.2. Assembly and Annotation of Mitochondrial Genome

Raw paired-end sequencing reads were quality-filtered using Fastp v.0.23.4 [26] to remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality regions [27]. Mitochondrial genome assembly was performed using GetOrganelle v.1.7.6.1 [28] with K-mer sizes of 17, 21, 33, 39, 45, 55, 65, 75, 85, 95, 105, 115, and 127; all other parameters were set to default values.

The assembled mitochondrial genomes were annotated using MitoFinder v.1.4.1 [29] and MitoZ v.3.6 [30]. The resulting annotation files (GenBank format) were reorganized using PhyloSuite v.1.2.3 [31] with cox1 (COI, COX1) designated as the starting gene. Annotations were subsequently manually refined in Geneious Prime v.2022.2.2 [32], adhering to the annotation principles outlined by Yang et al. [24]. The annotated mitochondrial genome sequences are provided in Supplementary File S1.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analyses incorporated the dataset from Xu et al. (2024) [27], supplemented with newly sequenced mitochondrial genomes of K. friniana (RTM11), H. textrix (SEM-A1), and H. yangi (SEM-B1) (Supplementary File S2, Table S1). Protein-coding genes (PCGs) and two ribosomal RNA genes (2R) were extracted and aligned using MAFFT under normal mode settings. Ambiguously aligned regions were removed using TrimAl v.1.2 [33] with the ‘automated1’ setting (Supplementary File S2, Table S2).

Phylogenetic reconstructions were performed on five distinct datasets: (i) 13PCGs123, encompassing all three codon positions of the 13 PCGs; (ii) 13PCGs123+2R, combining the 13PCGs dataset with two rRNA genes; (iii) 13PCGs12, excluding third codon positions of the 13 PCGs; (iv) 13PCGs12+2R, combining the 13PCGs12 dataset with two rRNA genes; and (v) 13PCGsAA, comprising amino acid sequences translated from the 13 PCGs.

Optimal substitution models were determined using ModelFinder v.2.2.0 (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017 [34]) under partitioned schemes: the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for maximum likelihood (ML) analysis and the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) for Bayesian inference (BI) analysis (Supplementary File S2, Table S3).

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction was conducted using IQ-TREE v.2.2.2 [34,35] with the optimal partition scheme and edge-linked partition model. Node support values were assessed using 100,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates. Bayesian inference was performed in MrBayes v.3.2.7a [36] with two independent runs of 1,000,000 generations each. Convergence was evaluated by monitoring the average standard deviation of split frequencies (ASDSF), with additional generations performed if ASDSF exceeded 0.005.

Topological incongruences among the inferred phylogenies were evaluated using TreeSpace [37] implemented in R v.4.3.1 [38], which utilizes Metric Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) to visualize tree relationships and hierarchical clustering methods (including single linkage, complete linkage, UPGMA, and Ward’s method) to identify distinct phylogenetic clusters formally. Final ML and BI trees were visualized using iTOL v.6 [39].

2.4. Sequence Analyses

Circular representations of mitochondrial genomes were generated using Proksee v.1.0.0a6 (https://proksee.ca/) [40] Strand asymmetries were quantified using the formulas of Perna and Kocher [41]: AT-skew = (A − T)/(A + T) and GC-skew = (G − C)/(G + C). Codon usage patterns and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values for the 13 protein-coding genes were calculated using PhyloSuite and visualized with the ‘ggplot2’ package [42] in R v.4.1.3 [38]. Non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution rate ratios were estimated using DnaSP v.6.0 [43] for all Semisulcospiridae sequences listed in Supplementary File S2, Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Mtgenome Organization

We successfully assembled complete mitochondrial genomes from three species: K. friniana (15,474 bp), H. textrix (15,660 bp), and H. yangi (15,744 bp) (Figure 2, Table 2). The genome sequences are deposited in Supplementary File S1. The overall A+T content was 66.0% (K. friniana), 65.3% (H. textrix), and 64.8% (H. yangi) (Table 3). These values are consistent with the AT bias observed across Semisulcospiridae mitochondrial genomes, which range from 64.85% to 77.32% (Supplementary File S2, Table S1).

Figure 2.

Gene maps of the K. friniana, H. textrix, and H. yangi mtgenomes. The innermost and middle circles depict the distribution of the sequencing depth, GC content, and GC-skew, respectively. The outermost circle represents the arrangement of genes: outer genes from the forward strand, and inner genes from the reverse strand.

Table 2.

Features of three species’ mtgenomes (RTM11/SEM-A1/SEM-B1).

Table 3.

Composition and skewness of three species’ mtgenomes (RTM11/SEM-A1/SEM-B1).

When calculated from the coding strand of individual genes, the A+T content of the 13 protein-coding genes was 65.4% (K. friniana), 64.5% (H. textrix), and 64.1% (H. yangi) (Table 3). Among the protein-coding genes (PCGs), ATP8 exhibited the highest A+T content, ranging from 71.0% to 72.8% across the three species (K. friniana: 72.8%, H. textrix: 72.2%, H. yangi: 71.0%), while COX3 displayed the lowest, varying from 59.1% to 60.9% (K. friniana: 60.9%, H. textrix: 59.1%, H. yangi: 59.8%) (Table 2).

Both AT-skew and GC-skew values were negative across all three species. AT-skew values followed the pattern: −0.043 (K. friniana) > −0.047 (H. yangi) > −0.065 (H. textrix). GC-skew values demonstrated the order: −0.026 (H. textrix) > −0.065 (H. yangi) > −0.069 (K. friniana).

3.2. Genes and Codon Usage

Among the 13 protein-coding genes, all utilized the standard initiation codon ATG, except ND4 in H. yangi, which employed GTG as the start codon (Table 2). All 13 genes terminated with canonical stop codons (TAG or TAA). Transfer RNA gene lengths varied from 62 to 72 bp. The 16S rRNA gene length was 1342 bp (K. friniana), 1339 bp (H. textrix), and 1333 bp (H. yangi), while the 12S rRNA gene was 890 bp (K. friniana), 892 bp (H. textrix), and 896 bp (H. yangi) (Table 2). The non-coding region (NCR), located between trnF and trnC, was 159 bp (K. friniana), 312 bp (H. textrix), and 391 bp (H. yangi).

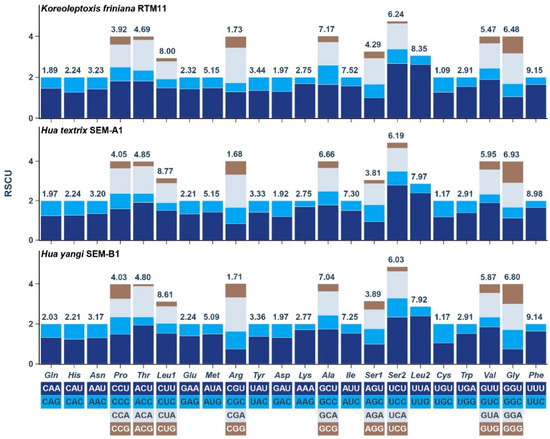

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) analysis revealed that UUA (Leucine) exhibited the highest RSCU values across all three species: 2.62 (K. friniana), 2.38 (H. textrix), and 2.40 (H. yangi). The lowest RSCU values were observed for UCG (Serine; 0.12) in K. friniana, AGG (Serine; 0.19) in H. textrix, and ACG (Threonine; 0.11) in H. yangi (Figure 3, Supplementary File S2, Table S4).

Figure 3.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the three mtgenomes. The codon families are provided under the x-axis. The frequency of amino acid usage is listed above the column.

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

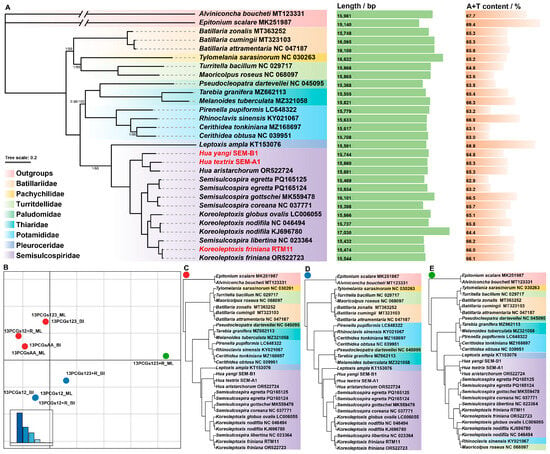

A total of ten maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) trees were inferred from five mitogenome datasets of Cerithioidea. These ten trees were grouped into three clusters, representing three distinct topological types (see Figure 4B–E). The most common topology is shown in Figure 4A,C. The primary differences between Cluster 1 (Figure 4C) and Cluster 2 (Figure 4D) lie in the clade formed by Pseudocleopatra dartevellei NC_045095, Tarebia granifera MZ662113, and Melanoides tuberculata MZ321058 (Figure 4). In Cluster 3 (Figure 4E), Rhinoclavis sinensis KY021067 and Maoricolpus roseus NC_068097 are embedded within Semisulcospiridae sequences, resulting in a substantially different topology from the first two clusters.

Figure 4.

An analysis of phylogenies from five mtgenome datasets. (A) Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) tree of Cerithioidea based on the dataset 13PCGs123. The GenBank accession numbers or specimen voucher numbers used are listed after the species names. The scale bar (0.2) corresponds to the estimated number of substitutions per site. Numbers at nodes are statistical support values for “BI posterior probabilities/ML bootstrap support”. “Unlabeled” denotes 100% bootstrap support. Color-coded clades are different families within Cerithioidea. The length and A+T content are shown to the right (full genome). (B) Two-dimensional metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot of ten trees, colored by different clusters. (C–E) For each cluster identified in (B), a representative tree was selected. Note: Sequences analyzed in this study are highlighted in red in (A).

The topologies of the phylogenetic trees inferred from 13 PCGs contain 27 Cerithioidea mitogenome sequences, of which 13 belong to Semisulcospiridae. The results demonstrate that Semisulcospiridae is most closely related to Pleuroceridae. The Semisulcospiridae sequences comprise five Semisulcospira species, five Koreoleptoxis species (including one newly reported in this study), and three Hua species (including two newly reported in this study). Four Semisulcospira sequences clustered in a clade, and another clade, sister to the former, contains five Koreoleptoxis sequences along with a misidentified ‘Semisulcospira libertina’ sequence (see Xu et al. [27]). Three Hua species formed a clade that is sister to the former two groups.

Regarding the three sequences provided in this study, H. textrix SEM-A1 is most closely related to Hua aristarchorum OR522724, while H. yangi SEM-B1 is sister to the clade formed by the former two sequences. K. friniana RTM11 is most closely related to the misidentified ‘Semisulcospira libertina’ sequence.

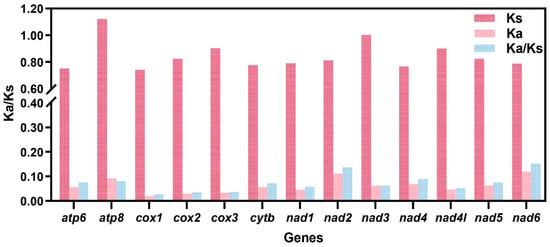

3.4. Non-Synonymous/Synonymous Analysis

Non-synonymous to synonymous substitution ratio (Ka/Ks) analysis demonstrated that COX1 (Ka/Ks = 0.026), COX2 (0.035), COX3 (0.037), and ND4L (0.051) evolved at relatively slow rates, indicating strong purifying selection. In contrast, ND6 (0.152), ND2 (0.137), ND4 (0.089), and ATP8 (0.081) exhibited comparatively elevated evolutionary rates (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Ka/Ks rates of 13 PCGs based on Semisulcospiridae species. The red, pink, and bule columns represent the values of Ks, Ka, and Ka/Ks, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Phylogenetic Relationships Within Semisulcospiridae

The phylogeny of Semisulcospiridae has been difficult to resolve, with studies based on a few molecular markers like COI and 16S often yielding unstable topologies and low support values at critical nodes [6,7,14]. Notably, some of these studies suggested a polyphyletic Semisulcospira genus, primarily due to the unstable positions of lineages from Japan characterized by unusual branch lengths [6,7]. To assess whether mitochondrial genomes could provide a more stable phylogenetic framework, we conducted phylogenomic analyses. For the species in our sampling, our results robustly support that there are three monophyletic groups corresponding to the three genera, Hua, Semisulcospira, and Koreoleptoxis. This finding is consistent with our previous studies [14,27] (considering the sequence Semisulcospira libertina NC_023364 is a misidentification of Koreoleptoxis sp., see Xu et al. [27]). A direct comparison with previous studies that reported a polyphyletic Semisulcospira genus is constrained by differences in taxonomic coverage, as our current dataset does not include the specific Japanese lineages.

4.2. Utility of Mitochondrial Genomes for Phylogenetic Inference

The reliability of the phylogenetic relationships within Semisulcospiridae inferred in this study is underscored by their stability across diverse analytical conditions. Our study generated ten phylogenetic trees from five distinct mitochondrial genome datasets, which were categorized into three topological clusters (Figure 4). Cluster 1 (Figure 4C), containing the most datasets, was selected as the main graph (Figure 4A). Importantly, despite these differences in the placement of other families (e.g., Thiaridae and Paludomidae), the relationships within Semisulcospiridae remained consistent across all clusters. This consistency indicates that the phylogenetic signal from mitochondrial genomic data is robust for this family, irrespective of the specific dataset or analytical approach employed here. Furthermore, we observed that the mitochondrial gene arrangement is highly conserved across the studied Semisulcospiridae species. This conservation suggests that for resolving phylogenetic relationships within this family, the nucleotide sequence information itself plays a far more critical role than gene order comparisons.

4.3. Future Directions

While mitochondrial genomes have demonstrated considerable utility in stabilizing the phylogeny for a significant portion of Semisulcospiridae, this study does not single-handedly resolve all historical controversies. The aforementioned Japanese Semisulcospira lineages and the North American genus Juga represent critical missing taxa in our analysis. Therefore, future research must prioritize the sequencing of mitochondrial genomes from these key groups. Integrating these data will be essential to rigorously test whether the three-clade framework we propose holds universally. Moreover, while nuclear genomic data would be invaluable for an independent phylogenetic assessment, such resources remain scarce for Semisulcospiridae. In this context, and given that our mitogenomic approach provides a more stabilized framework with higher support values compared with single-gene markers, the growing database of mitochondrial genomes presents a practical and promising path forward for future systematic studies aimed at achieving a comprehensive understanding of the family’s evolutionary history.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes16121488/s1, Supplementary File S1: Three mtigenomes’ information: RTM-11, SEM-A1, and SEM-B1; Supplementary File S2: Supplemental tables; Table S1: The blast results of mtgenome, COX1 and 16S (top 10 blast results are shown); Table S2: List of 29 sequences used for phylogenetic analysis; Table S3: Original and TrimAl lengths of 13 PCGs, 2 rRNAs, and 13 PCGsAA sequences; Table S4: Best partitioning schemes and models based on different datasets for maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference analysis; Table S5: Codon numbers and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of 13 PCGs in three mitogenomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.W. and H.Z.; data curation: S.Z. (Sheng Zeng), D.Y., Z.L. and Y.X.; formal analysis: Y.M., Y.X., X.C., Z.Z., S.Z. (Shen Zhong) and S.Z. (Sheng Zeng); funding acquisition: H.W. and H.Z.; investigation: Y.X., Y.M., Z.L., D.Y. and S.Z. (Shen Zhong); methodology: Y.M., D.Y. and S.Z. (Sheng Zeng); project-administration: H.W. and H.Z.; resources: D.Y., Z.L. and Y.X.; validation: Y.X., S.Z. (Sheng Zeng), Y.M., H.W. and H.Z.; visualization: S.Z. (Sheng Zeng); writing—original draft preparation: Y.X., Y.M. and S.Z. (Sheng Zeng); writing—review and editing: Y.X., Y.M., S.Z. (Sheng Zeng), D.Y., S.Z. (Shen Zhong), Z.L., X.C., Z.Z., H.W. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Fund of the Key Laboratory of Marine Ecological Monitoring and Restoration Technologies, Ministry of Natural Resources (MEMRT202411) and the Special Fund Projects for Promoting High-Quality Development of Marine and Fishery Industries in Fujian Province (FJHYF-L-2025-32).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve any vertebrate animals and thus did not require ethical approval. However, all necessary precautions were taken to ensure humane treatment of the mollusks studied.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We highly appreciate Bao-Gang Liu for collecting the specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- MolluscaBase. Available online: https://www.molluscabase.org (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Du, L.-N.; Yang, J.-X. Colored Atlas of Chinese Melania; Henan Science and Technology Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2023; p. 225. ISBN 9787572510458. [Google Scholar]

- Lydeard, C.; Cummings, K.S. Freshwater Mollusks of the World: A Distribution Atlas; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019; p. 242. ISBN 142142732X. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.-N.; Chen, J.; Yu, G.-H.; Yang, J.-X. Systematic relationships of Chinese freshwater semisulcospirids (Gastropods, Cerithioidea) revealed by mitochondrial sequences. Zool. Res. 2019, 40, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.-N.; Köhler, F.; Yu, G.-H.; Chen, X.-Y.; Yang, J.-X. Comparative morpho-anatomy and mitochondrial phylogeny of Semisulcospiridae in Yunnan, south-western China, with description of four new species (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea). Invertebr. Syst. 2019, 33, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, F. Against the odds of unusual mtDNA inheritance, introgressive hybridisation and phenotypic plasticity: Systematic revision of Korean freshwater gastropods (Semisulcospiridae, Cerithioidea). Invertebr. Syst. 2017, 31, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, F. Rampant taxonomic incongruence in a mitochondrial phylogeny of Semisulcospira freshwater snails from Japan (Cerithioidea: Semisulcospiridae). J. Molluscan Stud. 2016, 82, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, R.T. The Ecology of Freshwater Molluscs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA; Port Melbourne, Australia; Madrid, Spain; Cape Town, South Africa, 2000; Volume 509, ISBN 0 521 35210 X. [Google Scholar]

- Urabe, M. Trematode fauna of prosobranch snails of the genus Semisulcospira in Lake Biwa and the connected drainage system. Parasitol. Int. 2003, 52, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.M.; Chen, C.; Kang, Z.; Liu, Y. Snail Hosts of Paragonimus in Asia and America. Chin. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 1994, 12, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Medical Malacology; China Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 1993; p. 157. ISBN 7-5027-3356-6. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, E.E.; Garner, J.T.; Johnson, P.D.; Whelan, N.V. A systematic revision of the genus Juga from fresh waters of the Pacific Northwest, USA (Cerithioidea, Semisulcospiridae). Eur. J. Taxon. 2022, 848, 1–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, E.E.; Köhler, F. Morphological and molecular analysis of ‘Melania’ jacqueti Dautzenberg and Fischer, 1906: From anonymous orphan to critical basal offshoot of the Semisulcospiridae (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea). Zool. Scr. 2009, 38, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-B.; Meng, Y.-Z.; Zeng, S.; Wang, H.-J.; Zhong, S.; Yang, D.-Y.; Zhou, X.-P.; Glasby, C.J. A new species of Semisulcospira O. Boettger, 1886 (Gastropoda, Cerithoidea, Semisulcospiridae) from Fujian, China with mitochondrial genome and its phylogenetic implications. Zoosystematics Evol. 2025, 101, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Fuke, Y. Systematic revision of the Japanese freshwater snail Semisulcospira decipiens (Mollusca: Semisulcospiridae): Implications for diversification in the ancient Lake Biwa. Invertebr. Syst. 2022, 36, 1139–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Fuke, Y.; Miura, O. Integrative taxonomy of Semisulcospira kurodai (Mollusca, Semisulcospiridae) with insights into its geographic variation and description of three new species from Japan. Syst. Biodivers. 2025, 23, 2436684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Fuke, Y.; Miura, O.; Toyohara, H.; Nakano, T. Redescription of Semisulcospira reticulata (Mollusca, Semisulcospiridae) with description of a new species from Lake Biwa, Japan. Evol. Syst. 2024, 8, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, K.; Saito, T.; Uechi, T.; Sawada, N.; Miura, O. Out of the ancient lake: Multiple riverine colonizations and diversification of the freshwater snails in the genus Semisulcospira around Lake Biwa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2024, 191, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Fuke, Y. Diversification in ancient Lake Biwa: Integrative taxonomy reveals overlooked species diversity of the Japanese freshwater snail genus Semisulcospira (Mollusca: Semisulcospiridae). Contrib. Zool. 2022, 92, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boore, J.L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabuchi, K.; Fraser, T.H.; Song, H.; Azuma, Y.; Nishida, M. Revision of the systematics of the cardinalfishes (Percomorpha: Apogonidae) based on molecular analyses and comparative reevaluation of morphological characters. Zootaxa 2014, 3846, 151–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heude, P. Diagnoses molluscorum novarum in Sinis. J. Conchyliol. 1888, 36, 305–309. [Google Scholar]

- Heude, P. Diagnoses molluscorum novorum in Sinis collectorum. J. Conchyliol. 1889, 37, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Glasby, C.J.; Hwang, J.S.; Cai, L. Molecular systematics of Perinereis and an investigation of the status and relationships of the cultured species Perinereis wilsoni Glasby & Hsieh, 2006 (Annelida, Nereididae). Zoosystematics Evol. 2024, 100, 1297–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Meng, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S. De novo assembly of transcriptomes of six Hua species (Semisulcospiridae, Cerithioidea, Gastropoda). Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, S.; Meng, Y.; Yang, D.; Yang, S. The mitochondrial genome of Hua aristarchorum (Heude, 1889) (Gastropoda, Cerithioidea, Semisulcospiridae) and its phylogenetic implications. ZooKeys 2024, 1192, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.-J.; Yu, W.-B.; Yang, J.-B.; Song, Y.; DePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.-S.; Li, D.-Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allio, R.; Schomaker-Bastos, A.; Romiguier, J.; Prosdocimi, F.; Nabholz, B.; Delsuc, F. MitoFinder: Efficient automated large-scale extraction of mitogenomic data in target enrichment phylogenomics. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, S. MitoZ: A toolkit for animal mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T.; Kendall, M.; Almagro-Garcia, J.; Colijn, C. treespace: Statistical exploration of landscapes of phylogenetic trees. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: In-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W484–W492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, N.T.; Kocher, T.D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 41, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Data Analysis. In Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Wickham, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 189–201. ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).