Abstract

Background: Current carrier screening methods do not identify a proportion of carriers that may have children affected by spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Additional genetic data is essential to inform accurate risk assessment and genetic counselling of SMA carriers. This study aims to quantify the various genotypes among parents of children with SMA. Method: A retrospective cohort study was undertaken at Sydney Children’s Hospital Network, the major SMA referral centre for New South Wales, Australia. Participants included children with genetically confirmed SMA born between 2005 and 2021. Data was collected on parent genotype inclusive of copy number of SMN1 exons 7 and 8. The number of SMN2 exon 7 copies were recorded for the affected children. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the proportion of carriers of 2+0 genotype classified as silent carriers. Chi-square test was used to correlate the association between parents with a heterozygous SMN1 exon 7 deletion and two copies of exon 8 and ≥3 SMN2 copy number in the proband. Results: SMA carrier testing was performed in 118/154 (76.6%) parents, incorporating 59 probands with homozygous SMN1 deletions and one proband with compound heterozygote pathogenic variants. Among parents with a child with SMA, 7.6% had two copies of SMN1 exon 7. When only probands with a homozygous SMN1 exon 7 deletion were included, 6.9% of parents had two copies of SMN1 exon 7. An association was observed between heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 with two copies of exon 8 in a parent and ≥3 SMN2 copy number in the affected proband (p = 0.07). Conclusions: This study confirmed a small but substantial proportion of silent carriers not identified by conventional screening within an Australian context. Accordingly, the effectiveness of carrier screening for SMA is linked with genetic counselling to enable health literacy regarding high and low risk results and is complemented by new-born screening and maintaining clinical awareness for SMA. Gene conversion events may underpin the associations between parent carrier status and proband SMN2 copy number.

1. Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disorder characterised by progressive muscle weakness. Without therapeutic intervention, infantile onset (type 1) SMA is associated with a 95% mortality rate at two years of age [1]. However, targeted genetic therapies have revolutionised SMA care, improving the survival and reducing the comorbidities associated with the disease. With the introduction of reproductive genetic carrier screening (RCS) for SMA there is an opportunity for couples to become aware of their reproductive risk of having an affected child. Beyond the restoration of reproductive confidence, it remains vital that prospective parents have complete information including the burden, cost, and barriers to access treatment, to fully inform their reproductive decision-making [2].

SMA is caused by biallelic disruption of the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, leading to inadequate levels of survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, which is essential to maintain the integrity and survival of anterior motor neurons [3,4]. Approximately 95% of SMA cases are due to homozygous deletion of exon 7 in the SMN1 gene. Compound heterozygosity of an SMN1 exon 7 deletion in trans with a pathogenic SMN1 sequence variant accounts for a further 5% of cases [3,5]. A paralogous gene, survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2), which differs from SMN1 by five base pairs within the coding region, modulates the phenotype in a dose-dependent manner and is the most significant predictive biomarker of disease severity [6].

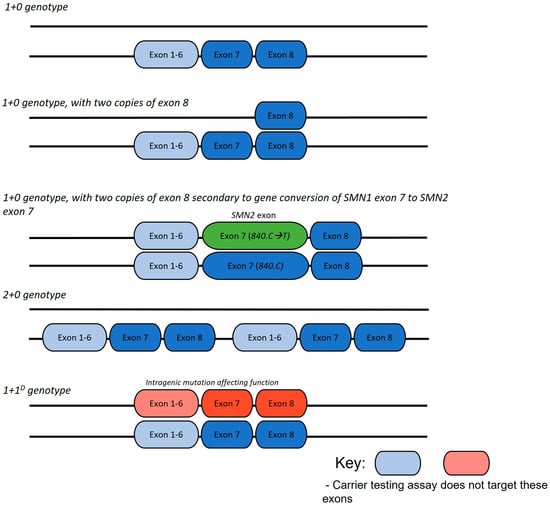

Reproductive genetic carrier screening (RCS) for SMA is generally limited to assays including multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) or quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) that determine the copy number of SMN1 exon 7 (referred to as 1+0 genotype) [7]. These conventional and currently utilised methods do not detect sequence variants and will not identify deletion carriers who have two copies of SMN1 on the non-deleted chromosome (referred to as 2+0 genotype) and those with a pathogenic SMN1 sequence variant (1+1D or 2+1D genotype) [7]. Individuals with sequence variants or a 2+0 genotype are referred to as ‘silent carriers’, appearing as an SMN1 copy number of 2 on MLPA testing, resulting in the potential to falsely reassure parents of a non-carrier status [8,9]. Rare cases of gonadal and somatic mosaicism have also been reported [10,11]. The presence of a 1+0, 2+0, or 1+1D genotype significantly impacts the chance of recurrence for a couple with a previous affected infant who has homozygous deleted SMN1 genotype.

Within the differing incidence of SMA internationally, the epidemiology of silent carriers also varies across jurisdictions with an increased incidence noted in certain African and Asian subgroups [12,13]. Within an Australian context, the epidemiology of silent carriers of SMA has been historically ascertained [14]. However, within an evolving diagnostic landscape where families have access to RCS and newborn screening, there is an imperative to investigate the contemporary epidemiology of silent carriers to inform local population screening.

In addition to epidemiological considerations, genotype as informed by carrier screening has the potential to affect SMA phenotype severity between generations. Gene conversion events, occurring at the c.840C>T nucleotide in SMN, are postulated to be relatively common, driving an increase in SMN2 copy number. In SMA-affected individuals, with bi-allelic SMN1 exon 7 deletion, the presence of SMN1 exon 8 is associated with both a greater SMN2 exon 7 copy number [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], as well as the translocation of an SMN2 exon 7 copy to the telomeric SMN1 region; both suggestive that the presence of SMN1 exon 8 reflects a gene conversion event of SMN1 exon 7 to SMN2 exon 7 rather than a simple deletion. Consequently, a carrier with a heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 and two copies of exon 8 may have a child with an increase in SMN2 copy number, thus predicting a less severely affected child.

2. Aims

- To investigate the genotype of SMA carriers using current carrier screening techniques. We aim to determine the proportion of silent carriers (2+0 and 1+1D) in an Australian state-based population and compare this to international data;

- To assess the relationship between parental SMN1 exon 8 copy number and proband genotype.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a retrospective cohort study including carrier parents of children with SMN-related SMA (0 to 18 years) born between January 2005 and December 2021, referred, and managed at the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network state-wide tertiary neuromuscular clinic. This time-period was chosen to reflect when routine carrier genetic testing commenced with the introduction of MLPA technology. Genetic testing was undertaken within the context of contemporary clinical practice and reported the number of copies of SMN1 exons 7 and 8. Probands were excluded when one or neither parent had undertaken SMA carrier testing. In the case of an affected sibship, the elder sibling was considered as the proband, and parental carriers only included once within the study population. The study was approved by the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ETH02020).

Data was obtained from medical records and the state-wide clinical genetics database (Trakgene, software, version 2.7.19). Collated data included genotype, ethnicity, and family history of neuromuscular disease of the family unit (carriers and probands).

Genotype was determined by copy number of SMN1 exons 7 and 8 in the proband and carriers, and SMN2 exon 7 in the proband. DNA from parents and probands were tested for SMN1 exon 7 and exon 8 copy number using the P060-B2 SMA MLPA kit produced by MRC-Holland. The SMN1 exon 7 probe has its ligation site at the C-to-T transition in exon 7 (c.840C>T) while the SMN1 exon 8 probe is able to distinguish between SMN1 and SMN2 at exon 8 (G-to-A transition (c.1155G>A). The SMN2 copy number quantitative analysis was performed by quantitative real time PCR and by droplet digital PCR from 2021 onwards.

The results of SMN1 sequencing, if undertaken, were recorded for children with SMA. Any further genetic analysis that identified carrier status was collected, including linkage analysis, functional RNA studies, genetic data from siblings or identification of intragenic mutations through research methods (including DNA sequencing). Specific parental carrier status and genotype were ascribed from analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Common SMA carrier genotype arrangements.

3.2. Literature Review

To allow for comparison with worldwide data, a literature review utilising two major medical databases, MEDLINE and PubMed, was conducted to identify any previously published studies that matched our methodology. We searched all articles available in English from January 1999 to October 2022 matching the search terms (SMA or spinal muscular atrophy) AND (Prenatal Diagnosis/or carrier screening.mp or Genetic Carrier Screening). We only included papers that incorporated the genetic data (SMN1 copy number) of parents of affected children with SMA, excluding all studies that statistically analysed carrier frequencies of SMN1 copy numbers within the general population to infer the percentage of silent carriers. All studies identified as eligible during abstract screening were then screened at a full-text stage by two reviewers (A.D. and J.D.). The full-text studies identified at this stage were included for the data extraction. Following reconciliation between the two investigators, a third reviewer (D.K.) was added to reach consensus for any remaining discrepancies.

Only studies that reported the number of parents with two SMN1 copy numbers were included and percentages of SMN1 exon 7 gene dosages were compiled. This method was chosen to allow for direct comparisons with previously published literature. Studies were segregated into those that included compound heterozygote probands and those with homozygous deletion of SMN1. To ensure a more accurate SMA carrier rate for risk analysis, we combined our population data with the published data.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Clinical and genetic data were analysed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages of SMN1 exon 7 gene dosage, genotype, and carrier status for parents. Standard deviation and 95% confidence interval of previously published studies was calculated using Graph Pad Prism to compare our data to worldwide published data. The results for those that included compound heterozygote probands were adjusted, with the parents of these probands removed to allow for direct comparison. Categorical and non-parametric data were analysed using a pairwise Chi-square test to examine the association between a carrier with a heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 with two copies of exon 8 and an SMN2 exon 7 copy number of ≥3 in the proband. A p-value of 0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad QuickCalcs Web site: http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ConfInterval1.cfm (accessed on 20 December 2022).

4. Results

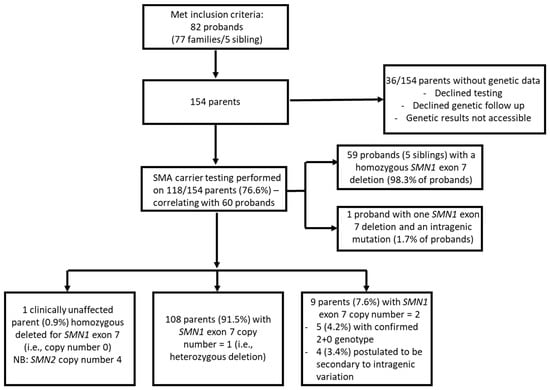

The cohort consisted of 82 probands from 77 families. SMA carrier testing was performed in 118/154 (76.6%) parents of 60 probands. Genetic data was unavailable for 36 parents due to declining testing for personal reasons, testing performed in external laboratories where results were not accessible, and parents lost to follow-up (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of spinal muscular atrophy carrier screening testing in New South Wales Australian population.

Of the 118 parents, 116 (98.3%) were parents of 59 probands with homozygous deletion of SMN1 (0+0), while two (1.7%) were parents of 1 proband who had a compound heterozygous genotype involving SMN1 exon 7 deletion and an intragenic point mutation (0+1D).

Parental carrier screening identified two copies of SMN1 exon 7 in 9/118 (7.6%) parents and within this population. This subgroup includes two probands diagnosed through NBS.

Out of the population, there was one copy of SMN1 exon 7 in 108/118 (91.5%) parents, and one parent who was clinically unaffected despite homozygous deletion of SMN1 and was later confirmed to have four copies of SMN2, likely serving to moderate clinical phenotype (Figure 3).

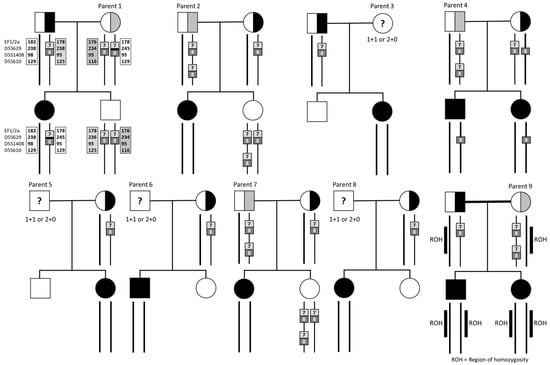

Figure 3.

Pedigrees, gene dosages, and analysis of nine families. All nine parents of the undetermined genotype had children with homozygous SMN1 deletion. Square: males, circles: females.

4.1. Parents with Two Copies of SMN1 Exon 7

Of the nine parents with two copies of SMN1 exon 7, three (33.3%) were mothers and six (67.7%) were fathers. Of all parents with two copies of the SMN1 gene, 7/9 (77.8%) were of European ancestry, 1/9 (11.1%) was of East Asian (Chinese), and 1/9 (11.1%) was of South Asian (Indian) heritage (Table 1, Figure 2). We were able to further clarify the genotype of five of the nine parents and determine that they were carriers following analysis of other family members. Parent 1 was inferred to have a pathogenic variant (1+1D) (1/118, 0.9%), and parents 2, 4, 7, and 9 (three fathers and one mother) were inferred to have the 2+0 genotype (4/118, 3.4%) after having further affected children, or through additional segregation in the family. Cascade testing was not undertaken in the other four parents and their genotype was undetermined (three fathers and one mother), and it remains possible that their child’s SMA may be due to a de novo deletion or non-paternity, in the case of the three fathers.

Table 1.

Parental genotypes corresponding to ethnic heritage.

Specific cases highlighted the heterogeneity of carrier genotype in SMA, and the complex pathways required to elucidate carrier status. Parent 1 had two copies of SMN1 exons 7 and 8, and Sanger sequencing did not identify point mutations in either allele. Transcriptomic studies of the trio showed no expression of SMN1 mRNA in the proband and reduction in both parents, inferring a pathogenic variant, not identified with these approaches (Figure 2). Linkage analysis [15] showed that the affected proband had inherited one maternal haplotype (the presumed mutated copy) while an unaffected sibling had inherited the other haplotype, linked to a functional copy. Parents 2 and 7 were both identified as having 2+0 genotype based on the genetic analysis of another unaffected child who had inherited three SMN1 gene copies. Parent 4 was identified as a likely 2+0 genotype carrier after having two affected children with no SMN1 gene copies. Although gonadal mosaicism could not be ruled out, a de novo mutation is less likely. Parent 9 was a mother of two affected children. The parents were first cousins and the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array of both children detected multiple regions of homozygosity consistent with parental consanguinity. A large 51 Mb region of homozygosity on chromosome 5 encompassing both the SMN1 and SMN2 genes indicated that the proband and the sibling had inherited a shared haplotype from both parents in this region, thus implying that Parent 9 had a 2+0 genotype (Figure 2).

4.2. Results in the Context of Worldwide Published Literature

The literature review identified two comparable studies [16,17] (Table 2) including probands of all genotypes (homozygous deletions and compound heterozygotes) and three comparable studies [14,18,19] including only probands with a homozygous SMN1 exon 7 deletion (Table 3). In all studies including probands with an SMN1 exon 7 homozygous deletion and compound heterozygotes, 16/227 parents (7.1%) were observed to have two SMN1 exon 7 copies.

Table 2.

A summary of previous English-language studies and this study included probands of all genotypes.

Table 3.

A summary of previous English-language studies and this study including only probands with a homozygous SMN1 exon 7 deletion.

In comparison to the cumulative findings of prior international studies, where only probands with homozygous deletions were included, the current study had a higher rate of individuals with two copies of SMN1 exon 7 (the current study had 8/116 (6.9%) versus the cumulative of prior studies 36/808 (4.5%), χ2 = 1.33, p = 0.24). However, this rate of 6.9% was comparable to the previous Australasian study rate of 6.0% [14] (Table 2).

4.3. Analysis of Parents with a Heterozygous Deletion of SMN1 Exon 7 and Two Copies of Exon 8

This study identified 52 probands born in 2009 or later with SMN2 data available. A total of 42 probands and 84 parents were included in the further analysis. Exclusion of 10 probands occurred secondary to missing genetic information in 1 parent, and absence of exon 8 information occurred in the remainder.

The parents of 6/42 (14.2%) probands had a heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 and two copies of exon 8. All six probands had ≥3 SMN2 copies. The unidirectional association of at least one parent who was heterozygous for SMN1, with two copies of exon 8 and an SMN2 copy number of three or more in the proband was χ2 = 3.231 (p = 0.07) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analysis of SMN2 copy number and parental genotype of heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 and two copies of exon 8.

5. Discussion

Spinal muscular atrophy, even within the new post treatment era continues to confer a substantial morbidity for affected individuals and remains a devastating diagnosis for families. This study presents the evaluation of the genotypes amongst parents of children with SMN-related SMA in a state-based Australian population within a paradigm of genetic carrier and newborn screening (NBS) and disease modifying therapy for SMA. The results highlight that current screening methods (MLPA or qPCR) do not identify a small but significant proportion of the SMA carrier population who may have children with SMA. This may be due to parents having a 2+0 genotype or a SMN1 point mutation, or when SMA arises from a de novo variant (exon 7 deletion). These findings have important implications for healthcare, emphasising the need to support health literacy in order to understand the low and high-risk results within screening programmes. Furthermore, NBS compliments carrier screening, to identify affected children early and together provide primary and secondary preventative strategies [22,23]. However, current NBS testing strategies used in Australia will not identify point mutations, or 2+0 genotype carriers which means that a small gap remains. In addition, this study observes a possible association between carrier parents (with a heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 and two copies of exon 8) and probands with ≥3 SMN2 copy numbers with the potential to confer a milder phenotype, postulated to be secondary to gene conversion events. The rate of silent SMA carriers can also be studied through assessment of population allele frequencies of 1, 2, and 3 copies of SMN1, inferring the percentage of 2+0 genotype utilising the principles of the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. In a 2014 meta-analysis using pooled data of 169,000 individuals in 14 published studies, this method estimated the 2+0 genotype to occur in 3.1% of Caucasian-heritage populations, 4.1% of Asian-heritage populations (defined as), 27.9% of African-heritage populations, 7.4% of Ashkenazi Jewish populations, 7.8% of Hispanic-heritage populations, and 8.1% of Asian Indian-heritage populations [14,20,24]. While these are comparable to the observed frequencies of 2+0 genotype ascertained by the methodology in the current study, the variations in the reported rates recapitulate the challenges shared by many rare diseases. Among these are small patient numbers and lack of a coordinated strategy for data mining. Whilst methodologies that ascertain population allele frequencies use large databases, thus counteracting the potential biases associated with the small sample size, they provide limited insight into the frequency of intragenic mutations contributing to a silent carrier status, relying on an assumed frequency of this genotype [24,25].

Ethnicity is noted to be associated with variation in silent carrier rate, however with a focus on the predominant ethnic groups within a population. Of our silent carrier cohort, 22% were of non-European background and identified as 2+0 genotype. Our study is limited in analysing silent carrier status within ethnic subgroups, which may limit the generalisability to broader populations. For example, the role of Australia’s unique ethnic spectrum may warrant further studies on the prevalence of the 2+0 genotype in broader subpopulations, including Indigenous subgroups to support equity of reproductive choice [13,21].

Within Australia, the rate of silent carriers has remained unchanged over the last two decades [14], yet continues to be higher when compared to similarly conducted international studies that have focussed on determining parental silent carrier status retrospectively from the birth of an affected child. As can be seen in our study, the recurrence risk for subsequent pregnancies is high in parents with the ‘2+0’ genotype with the potential to lead to several affected children within a sibship. In contrast, in the four parents with two copies of SMN1 exon 7 without further clarification (parents 3, 5, 6, and 8), it remains possible that the SMA in their child occurred as a de novo event, where the parent is truly not a carrier, with a low chance of recurrence in future pregnancies. If the previously published de novo rate of 2% [26] holds true for our cohort, it is plausible that at least one of these parents are not carriers. Thus, it remains imperative to distinguish between these two possibilities (of a de novo vs. a 2+0 genotype) through extended analysis of SMN, as it directly informs genetic counselling and decisions surrounding risk in future pregnancies.

As noted within our silent carrier cohort who had a spectrum of methodologies used to accurately determine carrier genotype, a multi-dimensional methodological approach to ascertaining carrier haplotype may be necessary. This includes utilising approaches including but not limited to SMN gene dosage, extending to linkage analysis, whole genome sequencing, long read sequencing, and RNA expression techniques. Thus, integration and collaboration between clinical and genetic laboratory testing services, to understand the clinical scenario including details of a comprehensive pedigree, coupled with expertise in diagnostic genomics will help navigate the complexities of SMN carrier elucidation, especially for individuals with a silent carrier status.

Through our findings, an association was observed between carrier parents with a heterozygous deletion of SMN1 exon 7 and two copies of exon 8 and a prognosticated milder genotype in the SMA-affected child (denoted by three or more ≥SMN2 exon 7 copy numbers). This observation supports the concept that the presence of SMN1 exon 8 in the absence of exon 7 may indicate an SMN2 exon 7 gene conversion event. Further study of the manner of architectural rearrangement and the rate of gene conversion events between generations may have clinical relevance to facilitate stratification of the severity of phenotype for subsequent pregnancies.

Whilst this study provides a retrospective snapshot, with technological advances being implemented in health practice and policy, the SMA clinical paradigm continues to rapidly change. In this context, the Australian Federal government has announced that reproductive carrier screening for SMA will be placed on the Medicare Benefit Schedule in November 2023, providing options for couples on their reproductive journey and reducing inequities of having to pay for screening. Accordingly, the present study provides critical data for its implementation, confirming that reproductive screening cannot stand alone and requires a model of care inclusive of robust bi-directional links across screening, diagnostic, and clinical (including genetic counselling) services, to ensure a patient- and family-focused delivery of screening processes [27]. Collectively, disease modifying therapies, NBS and RCS enable a precision medicine model of care. The awareness among health practitioners regarding predictive factors of SMA severity, such as SMN2 copy number and polymorphisms, as well as knowledge about therapeutic and reproductive options are important to provide optimal support and guidance to parents who receive high-risk screening results and can assist them in making informed decisions.

This study has some limitations in its applicability to a general and Australian population. The retrospective dataset was susceptible to ascertainment bias as prior to 2009 carrier testing of parents of SMA-affected children was not routinely offered. The data was also limited by the number of parents with 2+0 genotypes who proceeded with or were offered further testing based on clinical need and contemporary technologies to determine the genetic aetiology of their silent carrier status. The prospect of incorporating next generation sequencing (NGS) into carrier screening workflows to accurately identify silent carriers has been postulated [28]. In support of this notion, a recent economic evaluation of population-based expanded reproductive carrier screening for 300 recessive genes using a NGS panel demonstrated the cost effectiveness from health service and societal perspectives [29]. However, the high homology between SMN1 and SMN2 leads to poor mappability for short read sequencing methods (Table 5). Current available testing methodologies would not allow cost-effective identification of point-mutations in the screening context. However, as costs fall, this may change.

Table 5.

A summary of studies aimed to detect silent carriers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.D. and M.F.; methodology, J.E.D., A.D. and M.F.; software, J.E.D. and J.S.R.; validation, J.E.D., A.D. and M.F.; formal analysis, J.E.D. and A.D.; investigation, J.E.D., A.D., M.F. and J.S.R.; resources, J.E.D.; data curation, J.E.D., A.D. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.D., A.D., D.K. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, J.E.D., A.D., D.K., M.F., N.N.M., E.P.K., K.J.J. and D.R.M.; visualization, J.E.D., A.D., M.F., D.K. and N.N.M.; supervision, M.F., A.D. and J.S.R.; project administration, J.E.D., A.D. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to carry out this study. MAF received grant support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia: Investigator grant (APP1194940).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee 2020/ETH02020 on the 8 September 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee granted a waiver of participant informed consent due to the project solely using pre-existing, retrospective data and risk of harm in the form of undue distress by contacting family members of deceased patients.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to maintaining confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- D’Amico, A.; Mercuri, E.; Tiziano, F.D.; Bertini, E. Spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, K.A.; Farrar, M.A.; Kasparian, N.A.; Street, D.J.; De Abreu Lourenco, R. Family, healthcare professional, and societal preferences for the treatment of infantile spinal muscular atrophy: A discrete choice experiment. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrar, M.A.; Kiernan, M.C. The Genetics of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Progress and Challenges. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghes, A.H.; Beattie, C.E. Spinal muscular atrophy: Why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzier, C.; Chaussenot, A.; Paquis-Flucklinger, V. Molecular diagnosis and genetic counseling for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Arch. Pediatr. 2020, 27, 7s9–7s14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calucho, M.; Bernal, S.; Alías, L.; March, F.; Venceslá, A.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, F.J.; Aller, E.; Fernández, R.M.; Borrego, S.; Millán, J.M.; et al. Correlation between SMA type and SMN2 copy number revisited: An analysis of 625 unrelated Spanish patients and a compilation of 2834 reported cases. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2018, 28, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonic Genetics. Reproductive Carrier Screening Panel (CF, SMA and Fragile X) Macquarie Park; NSW: Sonic Healthcare, Austin, TX, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.sonicgenetics.com.au/our-tests/all-tests/reproductive-carrier-screening-panel-cf-sma-and-fragile-x/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Prior, T.W. Carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy. Genet. Med. 2008, 10, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, C.; Teng, Y.; Zeng, S.; Chen, S.; Liang, D.; Li, Z.; Wu, L. Detection of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Using a Duplexed Real-Time PCR Approach with Locked Nucleic Acid-Modified Primers. Ann. Lab. Med. 2021, 41, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L.; Daniels, R.J.; Dubowitz, V.; Davies, K.E. Maternal mosaicism for a second mutational event in a type I spinal muscular atrophy family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 63, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermann, T.; Zerres, K.; Anhuf, D.; Kotzot, D.; Fauth, C.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S. Somatic mosaicism for a heterozygous deletion of the survival motor neuron (SMN1) gene. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 13, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaart, I.E.C.; Robertson, A.; Leary, R.; McMacken, G.; König, K.; Kirschner, J.; Jones, C.C.; Cook, S.F.; Lochmüller, H. A multi-source approach to determine SMA incidence and research ready population. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, B.C.; Donohoe, C.; Akmaev, V.R.; Sugarman, E.A.; Labrousse, P.; Boguslavskiy, L.; Flynn, K.; Rohlfs, E.M.; Walker, A.; Allitto, B.; et al. Differences in SMN1 allele frequencies among ethnic groups within North America. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Calabro, V.; Chong, B.; Gardiner, N.; Cowie, S.; du Sart, D. Population screening and cascade testing for carriers of SMA. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, M.A.; Johnston, H.M.; Grattan-Smith, P.; Turner, A.; Kiernan, M.C. Spinal muscular atrophy: Molecular mechanisms. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009, 9, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng-Yuan, Z.; Xiong, F.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yan, T.-Z.; Zeng, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Chen, W.-Q.; Bao, X.-H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Molecular characterization of SMN copy number derived from carrier screening and from core families with SMA in a Chinese population. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 2010, 18, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ar Rochmah, M.A.; Awano, H.; Awaya, T.; Harahap, N.I.F.; Morisada, N.; Bouike, Y.; Saito, T.; Kubo, Y.; Saito, K.; Lai, P.S.; et al. Spinal muscular atrophy carriers with two SMN1 copies. Brain Dev. 2017, 39, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailman, M.; Hemingway, T.; Darsey, R.; Glasure, C.; Huang, Y.; Chadwick, R.; Heinz, J.; Papp, A.; Snyder, P.; Sedra, M.; et al. Hybrids monosomal for human chromosome 5 reveal the presence of a spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) carrier with two SMN1 copies on one chromosome. Hum. Genet. 2001, 108, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alías, L.; Barceló, M.; Bernal, S.; Martínez-Hernández, R.; Also-Rallo, E.; Vázquez, C.; Santana, A.; Millán, J.; Baiget, M.; Tizzano, E. Improving detection and genetic counseling in carriers of spinal muscular atrophy with two copies of the SMN1 gene. Clin. Genet. 2014, 85, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, K.A. Determination of SMN1 and SMN2 copy numbers in a Korean population using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Korean J. Lab. Med. 2010, 30, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaré, M.; Hendrickson, B.; Sango, H.A.; Chen, K.; Ba, J.N.; Amara, A.; Dutra, A.; Schindler, A.B.; Guindo, A.; Traoré, M.; et al. Genetics of low spinal muscular atrophy carrier frequency in sub-Saharan Africa. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, M.A.; Kiernan, M.C. Spinal muscular atrophy-the dawning of a new era. Nat. Rev. Neurology 2020, 16, 593–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Silva, A.M.; Kariyawasam, D.S.T.; Best, S.; Wiley, V.; Farrar, M.A.; Group, N.S.N.S. Integrating newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy into health care systems: An Australian pilot programme. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, W.K.; Hamilton, D.; Kuhle, S. SMA carrier testing: A meta-analysis of differences in test performance by ethnic group. Prenat. Diagn. 2014, 34, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, B.; Herz, M.; Wetter, A.; Moskau, S.; Hahnen, E.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S.; Wienker, T.; Zerres, K. Quantitative analysis of survival motor neuron copies: Identification of subtle SMN1 mutations in patients with spinal muscular atrophy, genotype-phenotype correlation, and implications for genetic counseling. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 64, 1340–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, B.; Schmidt, T.; Hahnen, E.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S.; Krawczak, M.; Müller-Myhsok, B.; Schönling, J.; Zerres, K. De novo rearrangements found in 2% of index patients with spinal muscular atrophy: Mutational mechanisms, parental origin, mutation rate, and implications for genetic counseling. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 61, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, A.D.; McClaren, B.J.; Caruana, J.; Tutty, E.; King, E.A.; Halliday, J.L.; Best, S.; Kanga-Parabia, A.; Bennetts, B.H.; Cliffe, C.C.; et al. The Australian Reproductive Genetic Carrier Screening Project (Mackenzie’s Mission): Design and Implementation. J. Pers. Medicine 2022, 12, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, X.; Xu, Y.; Chang, C.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Mao, A.; Wang, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: SMN1 Copy Number, Intragenic Mutation, and 2 + 0 Carrier Analysis by Third-Generation Sequencing. J. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 24, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, D.; Lee, E.; Parmar, J.; Kelly, S.; Hobbs, M.; Laing, N.; Mumford, J.; Shrestha, R. Economic evaluation of population-based, expanded reproductive carrier screening for genetic diseases in Australia. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genetics 2023, 25, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Liu, L.; Peter, I.; Zhu, J.; Scott, S.A.; Zhao, G.; Eversley, C.; Kornreic, R.; Desnick, R.J.; Edelmann, L. An Ashkenazi Jewish SMN1 haplotype specific to duplication alleles improves pan-ethnic carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genetics 2014, 16, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alías, L.; Bernal, S.; Calucho, M.; Martínez, E.; March, F.; Gallano, P.; Fuentes-Prior, P.; Abuli, A.; Serra-Juhe, C.; Tizzano, E.F. Utility of two SMN1 variants to improve spinal muscular atrophy carrier diagnosis and genetic counselling. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 2018, 26, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Folch, N.; Gavrilov, D.; Raymond, K.; Rinaldo, P.; Tortorelli, S.; Matern, D.; Oglesbee, D. Multiplex Droplet Digital PCR Method Applicable to Newborn Screening, Carrier Status, and Assessment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, A.K.; Huang, C.K.; Jin, H.; Zou, H.; Yanakakis, L.; Du, J.; Fiddler, M.; Naeem Goldstein, Y. Enhanced Carrier Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Detection of Silent (SMN1: 2 + 0) Carriers Utilizing a Novel TaqMan Genotyping Method. Lab. Med. 2020, 51, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Ge, X.; Meng, L.; Scull, J.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Zhang, T.; Jin, W.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; et al. The next generation of population-based spinal muscular atrophy carrier screening: Comprehensive pan-ethnic SMN1 copy-number and sequence variant analysis by massively parallel sequencing. Anesthesia Analg. 2017, 19, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, A.C.; Erdem, H.B.; Şahin, İ.; Agarwal, M. SMN1 gene copy number analysis for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in a Turkish cohort by CODE-SEQ technology, an integrated solution for detection of SMN1 and SMN2 copy numbers and the “2+0” genotype. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 2575–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Sanchis-Juan, A.; French, C.E.; Connell, A.J.; Delon, I.; Kingsbury, Z.; Chawla, A.; Halpern, A.L.; Taft, R.J.; Bentley, D.R.; et al. Spinal muscular atrophy diagnosis and carrier screening from genome sequencing data. Anesthesia Analg. 2020, 22, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).