Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Neurological complications, including loss of smell, cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, contribute to long COVID syndrome.

- A correlation exists between persistent anosmia and clinical dementia in patients who experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- SARS-CoV-2 infection of olfactory neuroepithelium may contribute to degeneration of limbic and cortical brain areas and, then, to the onset of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

- Interventions for treatment of SARS-CoV-2-mediated chronic olfactory dysfunction are required to improve brain and mental health in COVID-19 survivors.

Abstract

Complete or partial loss of smell (anosmia), sometimes in association with distorted olfactory perceptions (parosmia), is a common neurological symptom affecting nearly 60% of patients suffering from post-acute neurological sequelae of COronaVIrus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome, called long COVID. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may gain access from the nasal cavity to the brain (neurotropism), and the olfactory route has been proposed as a peripheral site of virus entry. COVID-19 is a risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), an age-dependent and progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized in affected patients by early olfaction dysfunction that precedes signs of cognitive decline associated with neurodegeneration in vulnerable brain regions of their limbic system. Here, we summarize the recent literature data supporting the causal correlation between the persistent olfactory deterioration following SARS-CoV-2 infection and the long-delayed manifestation of AD-like memory impairment. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the olfactory neuroepithelium is likely to trigger a pattern of detrimental events that, directly and/or indirectly, affect the anatomically interconnected hippocampal and cortical areas, thus resulting in tardive clinical dementia. We also delineate future advancement on pharmacological and rehabilitative treatments to improve the olfactory dysfunction in patients recovering even from the acute/mild phase of COVID-19. Collectively, the present review aims at highlighting the physiopathological nexus between COVID-19 anosmia and post-pandemic mental health to favor the development of best-targeted and more effective therapeutic strategies in the fight against the long-term neurological complications associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2. Persistent Anosmia After SARS-CoV-2 Infection Is Associated with an Increased Long-Term Risk of Developing Cognitive Impairment Related to Age-Related Neurodegenerative Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

Although the biological bases and molecular pathways underlying anosmia following exposure to SARS-CoV-2 are still a matter of debate in the literature published [87], several lines of evidence indicate that post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction might be a prodromal marker and/or an early readout for a clinical–pathological trajectory leading to neurodegeneration [88,89]. In this framework, prolonged and/or relapsing alterations of OBs in anosmic patients might have an early and prognostic value for the majority of affected patients in predicting an extensive neurodegeneration associated with neuropsychological symptomatology of poor mnemonic and emotional performance, consistent with long COVID symptomatology [90,91,92,93].

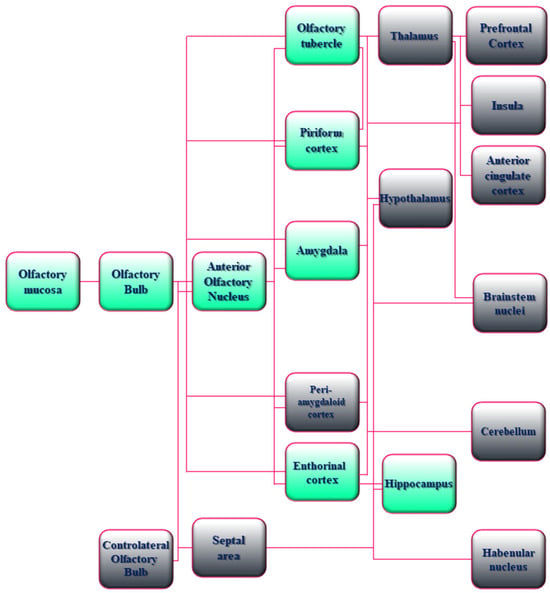

From an anatomic point of view, OBs are integral parts of the limbic system, including olfactory, amygdala, and hippocampal regions that have been referred for a long time as “rhinencephalon” or “smell brain” [94,95]. In particular, the human OS requires a hierarchical organization to convey information about the smell from the nasal epithelium to the primary and secondary olfactory cortices of the brain. First, the olfactory nerve—the bundle of axons (fila olfactoria) from sensory receptor neurons devoted to detecting odor molecules within the nasal epithelium—penetrates the small foramina in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and transmits excitatory signals to OBs that represent the first cerebral relay station of olfactory neurocircuitry. Upon entry into the cranial cavity, these fibers converge and make synaptic boutons named “glomeruli” on the output neuronal population called “Tufted and Mitral cells”, which are located in the External Plexiform Layer (EPL) and Mitral Cell Layer (MCL), respectively. From the glomeruli, processed information throughout second and third order nerves are then passed into the olfactory tract to upper cortical and subcortical regions, such as Anterior Olfactory Nucleus (AON), Piriform Cortex (PC), Cortical Amygdaloid nucleus (CoA) and Lateral Entorhinal Cortex (LEC) (primary olfactory cortex) and, in turn, to the PreFrontal Cortex (PFC), the OrbitoFrontal Cortex (OFC) and the HiPpoCampus (HPC) (secondary olfactory cortex) [96,97,98]. Noteworthy is that these regions dealing with the sense of smell are also critical for emotion, motivation, and long-term memory [95] (Figure 1). From a physiological point of view, both in rodent experimental models and in humans, OBs are functionally connected to the limbic system by sending projections and receiving inputs from Lateral Entorhinal Cortex (LEC), ventral HiPpoCampus (vHPC), and AmyGdala (AG) across a sensory–limbic neuronal network [98,99,100]. Therefore, a close anatomical and functional coupling exists between the odor-sensing olfactory areas and the high-order limbic regions, which are essential for cognitive processing and are selectively vulnerable in AD neurodegeneration. In accordance, comprehensive studies have underscored that olfactory bulbectomy and/or disruption of olfactory circuits in experimental animal models provoke several neurochemical, anatomical, and behavioural abnormalities typically associated with a classification of AD phenotype. For instance, impairment in memory and learning functions, disturbances in long-term synaptic plasticity, depletion of cholinergic neurons in the medial septum–diagonal band in combination with decrease of acetylcholine content and acetylcholinesterase, reduction in dendritic arborization and spine density, changes in neurogenesis, accumulation of extra-cellular Amyloid beta (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylation of intraneuronal tau protein with deposition of insoluble aggregated inclusions, hippocampal and neocortical atrophy are all downstream events connected with cytopathic insult of OS [101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112]. Besides, hyposmia is tightly linked with neuropathological brain changes of olfactory–limbic system connections at prodromal stages of AD before any detectable sign of cognitive impairments [113]. Furthermore, even though a direct, causal relationship between chronic smell impairment and increased susceptibility to AD has not yet been definitively demonstrated, an association between cognition and olfaction has been recently documented in long COVID [67,88,114]. More specifically, it has been proposed that SARS-CoV-2 infections in anosmic subjects might trigger and/or accelerate pathological progression of presymptomatic neurodegeneration [24,115,116,117]. In particular, a significant reduction in grey matter thickness in the OFC and ParaHippocampal Gyrus (PHG) regions supporting memory and neuropsychiatric function has been reported in association with an increment in tissue injury markers in primary olfactory cortex (temporal PC and AON) and cognitive decline by a longitudinal study carried out on 785 participants of UK Biobank, including 401 cases tested positive for infection with SARS-CoV-2 and underwent Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans with 141 days separating their initial diagnosis and the second imaging analysis [116].

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the anatomical and functional organization of the Olfactory System (OS) in humans. A flowchart of the hierarchical organization of the olfactory network in humans is shown. Boxes with green shading indicate the AD-relevant olfactory and limbic system connectivity. Boxes with gray shading indicate the other sensory, neuromodulatory, and motor olfactory cortical structures. In detail, the neuro-epithelium located in the olfactory mucosa of the human nasal cavity consists of bipolar OSNs whose axons coalesce to form the olfactory nerves that transmit processing signals by making excitatory synapses (glomeruli) onto the apical dendrites of Mitral and Tufted cells of OBs. The binding of airborne odorant molecules to specific receptors located on cilia of OSNs triggers a G-coupling protein-mediated intracellular transduction signaling with resultant generation of a Cyclic-Adenosine MonoPhosphate (cAMP) second messenger, opening of the cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels, and an influx of calcium and sodium ions, along with membrane depolarization and action potentials. The process of detection and specific information transmission requires multiple permutations between odor molecules and receptors because a single odor receptor can be activated by numerous similar odorants and vice versa. The OBs receiving inputs from the periphery project directly to the Anterior Olfactory Nucleus (AON) into the primary olfactory cortex and other contiguous regions with diverse associated functions including emotional processing of olfactory stimuli (AmyGdala (AG) and adjacent PeriAmygdaloid Cortex (PAC)), odor-induced motivated behavior (Olfactory Tubercle (OT)), odor-context episodic and working memory (entorhinal cortex–hippocampus), odor quality coding and discrimination (Piriform Cortex (PC)). Neuronal connections of these regions are reciprocal and bidirectional, allowing the integration of associative information about smell at the level of the primary olfactory cortex. The secondary olfactory cortex consists of structures (THalamus (TH), HypoThalamus (HT), HiPoCampus (HPC), and the portion of the PreFrontal Cortex (PFC) named the OrbitoFrontal Cortex (OFC)) receiving direct projections from the primary olfactory cortex. The nuclei of the TH send connections towards the orbitofrontal/insular/cingulate cortices and the motor areas of the brainstem involved in high-order functions such as odor-evoked reward, modulation of odor perception, and behavioral-guided emotional responses. Cerebellar (CB) and habenular (Hb) nuclei receiving projections from primary olfactory neurons, even though they do not directly participate in olfactory perception, play a role in smell-related motor performance.

On this point, a positive correlation between anosmia and cognitive and memory disturbances due to temporo-mesial dysfunction is reported in another study enrolling 18 patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome that underwent neuropsychological assessment and evaluation of clinical parameters approximately 2–3 months after recovery [118]. Likewise, in a cohort of 66 participants with acute or persistent COVID-19 anosmia, smell deterioration turns out to be linked with poor cognitive functions (short-term memory, working memory, visuospatial abilities, and orientation) in objective tests, adding more support to the occurrence of a clear relationship between the chronicity of olfactory disablement and memory complaints [119]. Persistent anosmia is significantly correlated with behavioural, functional and structural brain alterations (reduction in functional activity during the making-decision task, thinning of cortico-parietal regions, and dissipation in white matter integrity) in a large cohort of patients recovering from COVID-19, strongly supporting the fact that the persistent loss of smell is a reliable proxy biomarker for long-term brain and cognitive impairment following SARS-CoV-2 infection [120]. An increased vulnerability to verbal memory breakdown, accompanied by changes in delta-band EEG connectivity and White Matter Hyperintensity (WMH) volumes are reported in a large cohort of COVID-19 survivors with acute hyposmia at 10 months after infection resolution [121]. Moreover, another study reports moderate deficit in prefrontal-related cognitive responses in post-COVID-19 subjects with chronic hyposmia up to 4 months after the end of the infection, as assessed by means of a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy-ElectroEncephaloGram (fNIRS-EEG) co-recording techniques and Sniffin’ Sticks test paradigms aimed at testing their cognitive performance in concomitance with parameters of cerebral hemodynamic/bioelectrical activity and smell abilities [122]. In a similar way, a positive association between the reduction in integrity of the olfactory network, hyposmia severity, and neuropsychological performance in visuospatial memory and executive functions is observed in 23 patients with persistent (11 months and more) COVID-19-related anosmia in comparison to their sex- and age-matched controls [123]. Once more, mental clouding is reported in 71 (46.7%) out of 152 long COVID patients that had suffered from olfactory impairment and anosmia over 6 months from infection and underwent olfactometry, nasal endoscopy, headache scale, cognitive assessment, proving that a chronic, recrudescent smell deficit following exposure to SARS-CoV-2 greatly increases the probability of future neurodegenerative disease, including memory disorders [114]. On the contrary, no changes in amyloid-β peptide, tau protein, Neurofilament Light chain (NfL) and other AD markers have been detected in peripheral olfactory neurons from individuals with persistent (for 6 to 10 months) post-COVID-19 hyposmia when compared to age/sex-matched healthy controls, indicating that the loss of smell due to SARS-CoV-2 infection is not likely to predispose to future neurodegeneration [124]. Besides, an increased level of oxidative and neuroinflammatory stress in correlation with alteration in olfaction-associated genes has been found in a 3D in vitro model of olfactory mucosa from demented individuals with AD when compared to sister control cultures upon exposure to SARS-CoV-2, corroborating the existence of pathological cross-talk between COVID-19 and neurodegeneration [125]. Once more, post-acute COVID-19 survivors with olfactory defects complain of worse memory performance or “brain fog” in comparison to those without hyposmia/anosmia when objectively evaluated by means of both self-report surveys and clinical assessments of cognition in Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) tasks [126,127,128,129,130,131,132]. On the contrary, a significant trend between the recurrent olfaction and memory deterioration after the acute phase of COVID-19 has not been found in other prospective, longitudinal, case-control studies [133,134,135,136]. In particular, in one investigation performed on 141 confirmed cases of COVID-19 with prolonged neurological symptoms (more than 3 months), a lower frequency of anosmia is even detected in patients with cognitive impairment in comparison to the healthy and Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) groups, although prolonged hospitalization in the intensive care unit, cerebral ischemia and hypoxemia might have been confounding factors [137]. Finally, in 168 participants hospitalized for mild to moderate COVID-19 and evaluated at 6 months after discharge, the prevalence of objective hyposmia and subtle cognitive deficits is higher in older subjects [138], in line with results from a previous population-based investigation [139].

It’s important to emphasize that contradictory findings in the COVID-19 research are in part due to the urgency of the pandemic outbreak, with consequent heterogeneity in studies carried out [140]. Conflicting results can be ascribed to discrepancies in: (i) the study design (sample size, endpoints and observation periods, virus variants with diverse olfactory prevalence and disease severity, information registries about the participants’ mental health at baseline, and data collection of vaccination status); (ii) the methodologies used to assess the olfactory dysfunction and cognitive status (differing screening methods, diagnostic criteria and subjective (self-report) or objective outcome measures); and (iii) the low level of control for pre-existent confounders (risk factors and comorbidities) and non-standardized investigation of post-infection complications. Additional limitations are the lack of distinction in the COVID-19 group between participants with hyposmia and normosmia and between survivors from the early, more severe, and subsequent waves of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Alternatively, the occurrence of compensatory response of the neural network following temporary or permanent loss of smell should also be taken into account for results interpretation and comparability [141].

3. How Can SARS-CoV-2 Infection Promote the Onset of Alzheimer’s Disease?

Given that an intrinsic association between odour identification and spatial memory exists in humans regardless of the incidence of diseased states, the key question that arises in this field is what may be the possible cause(s) of the development of neurodegeneration and dementia in post-acute COVID-19 survivors with smell loss [88,142,143].

To start with, although most cases of COVID-19 patients in clinical practice recover from the loss of olfaction within 8 weeks from the initial infection and in highly variable way, some of them retain protracted and sometimes permanent olfactory deficits [77,144], likely due to immune cell infiltration and gene expression alteration of neuroepithelium residing in the nasal cavity, including OSNs [49]. Olfactory detriment, or lower ability to identify odors, is a preclinical sign of AD patients [145,146] by predicting the manifestation of early/moderate pathological stages associated with a reduction in cognitive scores and brain atrophy occurring in selected limbic structures, especially the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus [147,148,149,150,151]. Individuals with amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and olfactory deficits have a higher risk of their illness evolving into full-blown AD dementia with cerebral burden of Aβ, as shown in 63 participants undergoing olfactory identification task and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) [152,153]. Relevantly, the build-up of Aβ and tau into aggregated inclusions, named Senile Plaques (SPs) and NeuroFibrillary Tangles (NFTs), reactive gliosis with activation of inflammatory signalings, neuritic dystrophy, global decrease in gray matter, production of deleterious free radicals, neurotransmitter (cholinergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic) alterations, cellular senescence and neuronal death, are all pathognomonic hallmarks of AD taking place at multiple levels of the peripheral and central OS of affected subjects (olfactory epithelium, OBs/olfactory tract, olfactory nucleus and cortices) and mirroring similar neuropathology into their memory and cognitive-related higher brain centers, such as hippocampus and cerebral cortex [23,113,154,155,156,157,158]. In addition, COVID-19 survivors, particularly elderly individuals, display an increased susceptibility to developing AD-like memory complaints in response to severe outcomes, and vice versa, AD subjects manifest a greater vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection, thus indicating that an epidemiological connection exists between these two complex and multifaceted syndromes that share neuropathological convergences, common risk factors, and mechanistic aspects [85,159,160]. In agreement, is the evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes in the nasal neuroepithelium the release of few pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, in particular IL-1β and IL-6 and TNFα, and the activation of transcription factors, such as the NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome, that correlate with the severity of hyposmia after COVID-19 and overlap with the analogous intracellular signal transduction pathways and immune mediators related to AD neurodegeneration [161,162,163]. In addition, the dysregulation of immune response occurring in the brain in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers a marked oxidative stress with production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and NitrOgen Species (NOS) that further contribute in vicious feed-forward cycle to aggregation of insoluble Aβ fibrils and propagation of neuronal damage [164,165]. Interestingly, infection of the nasal epithelium by neurotropic human viruses, for instance Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV, Types 1 and 2) and Herpesvirus (Types 6A and 6B), elicits an exaggerated neuroinflammatory response in the brain that, in turn, promotes the production of Aβ known to be endowed with natural antimicrobial protective property [166].

Additionally, just as other viral pathogens [167,168], SARS-CoV-2 infection (which shows low neurotropic property in humans [51]) directly and/or indirectly leads, per se, to a boost in cerebral amyloidosis by accelerating in mice the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP)/Aβ metabolism because of an upregulation of β/γ secretase processing complex and/or an interference with its intracellular trafficking and clearance and/or a promotion of its seeding property [169,170,171]. Further complicating the phenomenon at hand, Aβ deposition triggers downstream several adverse consequences (tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, ionic imbalance, proteostasis, aberrant membrane receptor stimulation, disruption of neuronal network (excitatory–inhibitory imbalance), alteration in synaptic transmission and plasticity, DNA/RNA injury, axonopathy, apoptosis), causing cytotoxic insult to the surrounding parenchyma and ending up in neuronal shrinkage and loss [172]. Consistently, an increase in tau hyperphosphorylation at several AD-relevant epitopes with mislocalization into the somatic compartment and high propensity to form insoluble aggregates are observed following the exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in human SH-SY5Y neuron-like cell line and transgenic mouse expressing human ACE2 (K18-hACE2), an animal model that does not completely reflect the human pathophysiology [173]. Of note, in a mouse model overexpressing a humanized mutant form of APP (hAPP) into OSNs, a progressive spreading of Aβ through the OS towards the hippocampus is detected with aging [174], consistent with the “olfactory vector hypothesis” in which xenobiotics and toxins are supposed to trigger the prion-like transneuronal propagation of amyloid proteopathic seeds from the nose to brain during AD development [175,176,177]. Furthermore, the Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 interacts and interferes with α7 nicotinic AcetylCholine Receptors (nAChR) [178,179] that are present both in the nose and in the basal forebrain, corroborating that a hypofunction/disruption of the cholinergic system together with inflammatory response and redox imbalance occur both in COVID-19 and AD. Relevantly, the adenovirus-mediated expression of SARS-CoV-2 S1 in nasal cavity of mice is proved to cause marked OBs impairment due to a local increment of apoptotic markers associated with diminution of intracerebral acetylcholine production and hippocampal neurogenesis, excessive neuroinflammation and neurological complications that are mitigated by administration with donepezil, an U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved cholinergic compound used clinically for treatment of moderate or severe cognitive disturbances in AD patients [180].

Moreover, MRI and cognitive longitudinal analyses have revealed in a large cohort of participants of UK Biobank diagnosed positive for infection with SARS-CoV-2 that a greater alteration in markers of tissue damage occurs into their limbic structures in association with decline in memory performance, likely due to extensive neuroinflammation, disease spread throughout the olfactory pathways and/or loss of sensory input with anosmia [181]. An abnormal build-up of AD-related tau protein hyperphosphorylation accompanied by sustained glia stimulation and upregulation in inflammatory factors have been detected in the hippocampus and medial entorhinal cortex from postmortem human brain samples within 4–13 months of recovery from acute COVID-19 [182]. More recently, in a prospective and case-control study performed on 36 hyposmic and 26 normosmic participants who had experienced mild COVID-19 compared to 25 healthy controls, an atrophy in the OBs and thickness of related cortical structures (left orbital sulci) have been detected in correlation with lower cognitive performance especially in language skills in the relatively long-term period (402 ± 215.8 days), just as in elderly individuals and people with AD [183]. Notably, the majority of the above-mentioned studies are correlational with follow-up periods of less than 12 months, which are not long enough to accurately predict (and fully recapitulate) the entire neuropathological and clinical spectrum of AD. As a consequence, additional longitudinal investigations with prolonged observation time points (more than 1 year) aimed at assessing the functional and cognitive consequences of structural brain changes occurring in COVID19 survivors are still required to prove a direct, causal involvement of SARS-CoV 2 infection for the alterations of limbic brain via the olfactory route in triggering the full-blown AD phenotype.

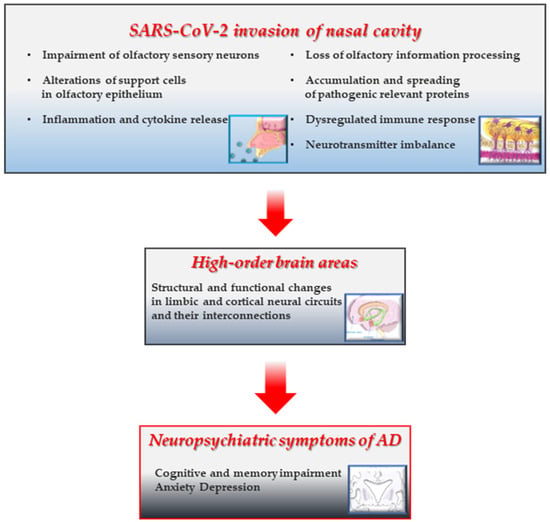

Despite this limitation and in light of the current studies cited in the present review, it has been suggested that: (i) the presence of olfactory impairment in patients recovering from COVID-19 might be a predictor of dementia-like decline in middle-aged and older adults [184]; (ii) anosmia and cognitive deterioration may arise from both direct and indirect effects (or combination of them) of SARS-CoV-2 nasal infection that may instigate and/or precipitate the underlying neuropathological processes linked with development of AD and clinical dementia [88,116,171,184,185] (Figure 2). From the OB, the virus might potentially gain access to different regions within the neuraxis (neuroinvasion), but, as previously reported, SARS-CoV-2 does not appear to be a neurotropic virus in humans [186]. In addition to infection of support cells (SUS and Bowman gland cells), followed by the deciliation and disruption of OE integrity [51], a deleterious effect on the OE resulting in inflammation and, then, in neuronal impairment is considered to be another plausible mechanism (i.e., immune reaction of the host) by which SARS-CoV-2 causes anosmia [27]. To this end, previous studies published before the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak have clearly shown that persistent nasal inflammation caused by deleterious environmental agents, including viruses, induces in mice a loss of OSNs and then atrophy of the OB [187]. In detail, the damage is due to the shrinkage of superficial layers of the OB (i.e., the Olfactory Nerve Layer (ONL), Glomerular Layer (GL), and EPL). The shrinkage of the ONL and GL originates from the retraction of OSNs axons (and loss of synapses) and gross injury of the Olfactory Epithelium (OE) owing to nasal inflammation [188,189]. Likewise, COVID-19 patients with anosmia display imaging and neuropathological findings of neuroinflammation and OB atrophy with changes in higher olfactory structures, such as reduction in gray matter mass and hypometabolism assessed by PET scans [190]. Relevantly, an association exists between nasal inflammation and neurologic disorders, including AD [191], supporting the notion that an indirect impairment of OSNs due to neuroinflammation with subsequent OB atrophy might affect the downstream synaptically-interconnected limbic circuits. Consistently, a marked inflammatory and degenerative pathology (microglial activation with neurophagia) in the absence of signs of viral RNA or protein (except for nasal epithelium) has been reported into the brains of a large cohort of COVID-19 cases from Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital, indicating that direct SARS-CoV-2 infection of brain tissues does not account for the neuropathological changes [192].

Figure 2.

SARS-CoV-2 infection of the nasal neuroepithelium may trigger a cascade of AD-like damaging events leading to degeneration of the limbic system involved in cognitive memory. A graphic illustrating the possible pathomechanisms underlying the neurodegenerative alterations of the limbic system and related AD-like amnestic and neuropsychiatric symptoms following nasal infection of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 subjects with persistent anosmia. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the nasal cavity and/or the long-term maladaptive, self-perpetuating responses following its acute invasion locally cause the disruption of cytoarchitecture and integrity of neuroepithelium (reduction in regeneration, sensory deciliation, deprivation of energy supply, and gene expression alteration) [51,52,60,65,186], persistent inflammatory infiltration) [17,62,77], proteostasis with accumulation/aggregation/spreading of toxic proteins [173,174], dysregulation in neurotransmission and network connectivity [178,179]. These insults trigger (and/or accelerate) long-range noxious effects on anatomically-interconnected higher limbic (and cortical) centers [115,116,120,121,122,123,181,182,183] whose progressive deterioration is associated with episodic memory and cognition decline in AD pathology. Prolonged or dysregulated responses following olfactory infection of SARS-CoV-2 could initiate transition to AD-like neuropathology [114,118,119,129,130,131,183,184]. This figure was partly generated using Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com, accessed on 15 October 2025) licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/, accessed on 15 October 2025).

Another conceivable pathogenesis of COVID-19-induced anosmia may involve the disuse of the olfactory sense (i.e., odor deprivation). In this context, several studies have shown that loss of smell in adults in response to an insult (acquired anosmia) triggers structural and functional changes in upper cortical areas associated with olfactory processing [193,194]. In line, olfactory impairment has been reported to be associated with signs of neurodegeneration such as lower volume in the fusiform gyrus and the middle temporal cortex (including the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex) and accelerated AD-like cognitive decline over 15 years [195]. Apart from the convergence of common molecules and biological pathways, the evidence that the SubGranular Zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus and the SubVentricular Zone (SVZ) of OBs are both sites of adult neurogenesis may also account for the selective vulnerability of these two neuronal circuitries and the coupled anosmia/AD-like dementia phenotypic manifestation in COVID-19. Attenuations in hippocampal and olfactory neurogenesis due to impairment of endogenous neural stem cell activity might be the neuropathological substrate linking limbic neurodegeneration and hyposmia/anosmia following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Impairments in olfaction and cognition occurring in COVID-19 syndrome may arise from the SARS-CoV-2 virus-mediated alteration of physiological neurogenesis that is known to play key roles in maintenance/regeneration of olfaction and cognitive learning/memory processes [196].

4. Therapy for Treatment of Olfactory Impairment in COVID-19

Understanding the intricate and variegated nature of the OBs damage following the SARS-CoV-2 infection and its mechanistic aspects is of paramount importance to design effective therapeutic interventions and long-term preventive strategies to counteract and/or mitigate the potential neurological complications in affected patients with long COVID sequelae. Notably, recent observations have shown that the incidence of olfactory deterioration is greatly variable among different SARS-CoV-2 genetic variants, calling into question the different outcomes and prognosis of individuals with chronic anosmia and/or parosmia after the initial disease presentation. Historically, the first wave of COVID-19 emerged in China in 2019 (the original Wuhan D614 strain (20A.EU2)) and spread to the rest of Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Australia, and North and South America. The spread was accompanied by the appearance of the G614 virus mutation, which was much more efficient in infecting the olfactory epithelium, resulting in greater olfactory dysfunction than the original D614 variant. Since the diffusion of the G614 virus throughout the world, several new SARS-CoV-2 virus variants have emerged—Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (B1.1.28), and Delta (B.1.617.2)—that carry the D614G mutation and are similarly harmful to olfaction [197]. In 2022, the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) emerged, which has numerous mutations in its Spike protein compared with the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 and is less neuroinvasive with scarse propensity to infect the olfactory epithelium owing to its strong hydrophobicity, alkalinity and lower solubility into the mucus in comparison to Delta (B.1.617.2) or Alpha (B.1.1.7) ones [198,199]. In keeping with this finding, the prevalence of long COVID with neurological complications might be lower in individuals infected by the Omicron variant than those infected by other variants [200]. Besides, a possible genetic predisposition to COVID-19-related anosmia has been proposed by a multi-ancestry Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) reporting in individuals, especially of European ancestry, who experienced loss of smell following SARS-CoV-2 infection due to the presence of UDP Glucuronosyltransferase Family 2 Member A1 and A2 (UGT2A1 and UGT2A2), two genes that are expressed in the olfactory epithelium and involved in metabolizing odorants and detoxifying compounds [201]. Additional risk factors for olfactory impairment in COVID-19 patients are proposed to be smoking, lifestyle, allergic conditions, sex, age, body size, race, physical inactivity, hypertension, heavy alcohol consumption and diabetes mellitus causing differences in cytokine production profile, relative abundance of neurons and glial cells in the olfactory epithelium, different expression level of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in SUSs, microvascular and inflammatory components [202]. Although different studies have provided conflicting results about what are actually the predisposing factors for persistent COVID-19-induced olfactory impairment (for details see [23,202]), smoking, history of allergy (particularly respiratory), and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) appear to significantly increase the risk for smell loss in COVID-19 patients [203,204].

Rehabilitation and/or treatments with drugs possessing potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroregenerative, modulatory, and neuroprotective properties are currently used, sometimes in a combined regimen, to relieve the post-viral COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. In this framework, olfactory training (OT) [205,206] based on the repeated inhalation exposure of four odorant agents (clove, citronella, eucalyptus, and phenylethyl alcohol) together with supplement-based oral therapy and pharmacological (local or systemic) interventions, including vitamin A or its metabolite Retinoic Acid (RA) [207,208], omega-3 fatty acid [209], zinc sulphate trace element [210], Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) [211], PalmitoylEthanolamide fatty Acid (PEA) with flavonoid Luteolin (PEA-LUT) [212], gabapentin [213,214], Cerebrolysin [215], 13-cis-retinoic acid plus aerosolized Vitamin D [216], dexamethasone [217], corticosteroids [218,219,220], insulin [221,222], autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma enriched with growth factors (PRP) [223,224], buffer solutions (sodium citrate, tetra sodium pyrophosphate and sodium gluconate) [225,226,227] are under investigation in recent prospective trials. Some agents (for all details, including number of clinical trials, phase distribution and a proposed management algorithm for clinicians see [21,228,229]) requires additional testing (omega-3 fatty acid supplement, gabapentin, insulin, PRP, vitamin A are in Phase 2/3) while others appear more effective being at the end of their clinical experimentation (aerosolized all trans-retinoic acid plus Vitamin D, cerebrolysin, dexamethasone, corticosteroids nasal irrigation and PEA-LUT are in Phase 4). In particular, the most promising drugs appear to be PEA, a bioactive lipid mediator with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities, administered in combination with LUT, a flavonoid (3,4,5,7-tetrahydroxy flavone) contained in plants with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties, and Cerebrolysin, a neuropeptide preparation with neuroprotective and neurotrophic actions similar to those of neurotrophic growth factors [228,229,230]. Transplantation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), implantation of an electrical device for stimulation of the OBs, and intranasal delivery of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for SARS-CoV-2 RNA hold promise as innovative therapeutic options, but they still require further validation. Standardization of protocols and outcome assessments, along with long-term studies are needed in the future to compare the safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of different central and peripheral-acting therapeutic options for chronic COVID-19-associated smell loss over placebo, even though a personalized treatment might be desirable due to differences in individual susceptibility and SARS-CoV-2 variants [229,230].

5. Conclusions

Evidence is accumulating on the pathological connection between long COVID following SARS-CoV-2 infection and neurodegeneration [231]. The olfactory neural circuit is an entry route of virus neurotropism to the brain, and anosmia is an early symptom of patients suffering from COVID-19. Several commonalities and underlying mechanisms have been described in support of the risk factors between COVID-19 and the initial stages of AD development [85]. The main purpose of the present review is to provide evidence that hyposmia due to COVID-19 infection causes modifications in the OB and olfactory-related cortical structures in the CNS, but whether these changes in the brain may univocally predict over time the cognitive decline remains to be elucidated. To date, the knowledge of the long-term impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the CNS is yet unknown due to the insufficient time elapsed since the COVID19 pandemic outbreak. It has been proposed that effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection propagated throughout the olfactory network may accelerate brain aging and favor the later onset/development of age-related AD-like neurodegeneration and dementia even years after the acute phase of viral infection. The virus invasion of the sinonasal cavity may directly spread, likely through exosomes, to the higher-order neuroanatomically-connected limbic and cortical areas involved in cognition and episodic memory, and/or initiate a local chain of degenerative events (dysregulated immune response, misfolding/aggregation of toxic proteins) that, in turn, affect the neuron function/survival and glial reactivity. As an alternative, virus-triggered systemic cytokine storm and increased BBB permeability indirectly amplify and/or promote neurodegenerative processes of these deep temporal nuclei associated with sensory inputs [171,232]. The selection of reliable SARS-CoV-2 animal models that approximate the human disease process of long-term neurodegeneration is urgently required for studying the etiology and testing the therapeutic efficacy of vaccines or drugs in pre-clinical studies. In addition, longitudinal and cross-sectional and case-control studies assessing pairwise cognitive and olfactory performances in conjunction with classical biomarkers (Aβ 1–42, phosphorylated tau, and NfL) in CerebroSpinal Fluid (CSF) or plasma from patients recovering from neurological sequelae of acute COVID-19 are needed in the near future to understand whether the chronic anosmia with olfactory deterioration actually contributes to the onset and/or worsening AD manifestation or is merely a bystander epiphenomenon. A combination of pharmacological, nutritional, and rehabilitative approaches is also recommended to re-establish the olfactory epithelial homeostasis in the management of post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction and its psychological, neuropsychiatric, and cognitive consequences.

Author Contributions

E.S., A.T., R.F. and V.A.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing; G.A.: Conceptualization and Writing—Original Draft Preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Alzheimer’s Association Research Grant—Proposal ID: 971925 and Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2021-12374301). This work was also supported (in part) by Fondo Ordinario Enti (FOE D.M865/2019) funds in the framework of a collaboration agreement between the Italian National Research Council and EBRI. FRES 2024_0000032: “Manifestazioni neuropsichiatriche nel long-COVID”, CUP B83C25001270001.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Valentina Latina for her valuable scientific and technical contributions during the preparation of this manuscript. We are also grateful to A. Carbone for his valuable teachings. E.G., V.A., and G.A. are members of Master Universitario in Tecniche diagnostiche autoptiche e forensi (pathology assistant 1) https://www.unicatt.it/corsi/master-universitari/roma/tecniche-diagnostiche-autoptiche-e-forensi/faculty.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

COronaVIrus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome; Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS); Central Nervous System (CNS); Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II (ACE2); TransMembrane PRoteaSe Serine type 2 (TMPRSS2); Olfactory Sensory Neurons (OSNs); SUStentacular cells (SUSs); Globose and Horizontal Basal Cells (GBCs and HBCs); NeuRoPilin-1 (NRP1); BaSiGinor (BSG); Olfactory System (OS); Olfactory Bulbs (OBs); Anterior Olfactory Nucleus (AON); AmyGdala (AG); PeriAmygdaloid Cortex (PAC); Olfactory Tubercle (OT); Piriform Cortex (PC); THalamus (TH); HypoThalamus (HT); HiPoCampus (HPC); PreFrontal Cortex (PFC); OrbitoFrontal Cortex (OFC); InterLeukin-6 (IL-6); Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α); InterFeroN-gamma (IFN-γ) and CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10); Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA); Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD); CerebroSpinal Fluid (CSF); small interfering RNAs (siRNAs); Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS); NitrOgen Species (NOS); Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP); Amyloid beta (Aβ); Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS); UDP Glucuronosyltransferase Family 2 Member A1 and A2 (UGT2A1 and UGT2A2); SubGranular Zone (SGZ); SubVentricular Zone (SVZ); Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI); Positron Emission Tomography (PET); Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB); Senile Plaques (SPs); NeuroFibrillary Tangles (NFTs); Blood Brain Barrier (BBB); Retinoic Acid (RA); Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA); PalmitoylEthanolamide fatty Acid (PEA); Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs); Cerebellum (CB); Habenula (Hb).

References

- Guo, G.; Ye, L.; Pan, K.; Chen, Y.; Xing, D.; Yan, K.; Chen, Z.; Ding, N.; Li, W.; Huang, H.; et al. New Insights of Emerging SARS-CoV-2: Epidemiology, Etiology, Clinical Features, Clinical Treatment, and Prevention. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-S.; Lam, C.-Y.; Tan, P.-H.; Tsang, H.-F.; Cesar Wong, S.-C. Comprehensive Review of COVID-19: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Advancement in Diagnostic and Detection Techniques, and Post-Pandemic Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slama Schwok, A.; Henri, J. Long Neuro-COVID-19: Current Mechanistic Views and Therapeutic Perspectives. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talkington, G.M.; Kolluru, P.; Gressett, T.E.; Ismael, S.; Meenakshi, U.; Acquarone, M.; Solch-Ottaiano, R.J.; White, A.; Ouvrier, B.; Paré, K.; et al. Neurological sequelae of long COVID: A comprehensive review of diagnostic imaging, underlying mechanisms, and potential therapeutics. Front. Neurol. 2025, 15, 1465787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.; Laksono, B.M.; de Vrij, F.M.S.; Kushner, S.A.; Harschnitz, O.; van Riel, D. The neuroinvasiveness, neurotropism, and neurovirulence of SARS-CoV-2. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spudich, S.; Nath, A. Nervous system consequences of COVID-19. Science 2022, 375, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.U.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.H.; Normandin, E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Mukerji, S.S.; Keller, K.; Ali, A.S.; Adams, G.; Hornick, J.L.; Padera, R.F., Jr.; Sabeti, P. Neuropathological features of COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sánchez, C.M.; Díaz-Maroto, I.; Fernández-Díaz, E.; Sánchez-Larsen, Á.; Layos-Romero, A.; García-García, J.; González, E.; Redondo-Peñas, I.; Perona-Moratalla, A.B.; Del Valle-Pérez, J.A.; et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology 2020, 95, e1060–e1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadaş, Ö.; Öztürk, B.; Sonkaya, A.R. A prospective clinical study of detailed neurological manifestations in patients with COVID-19. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1991–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Mu, J.; Guo, J.; Lu, L.; Liu, D.; Luo, J.; Li, N.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; Gao, H.; et al. New onset neurologic events in people with COVID-19 in 3 regions in China. Neurology 2020, 95, e1479–e1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleri, S. Neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2 and neurological diseases of the central nervous system in COVID-19 patients. Exp. Brain Res. 2022, 240, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniz-Mondolfi, A.; Bryce, C.; Grimes, Z.; Gordon, R.E.; Reidy, J.; Lednicky, J.; Sordillo, E.M.; Fowkes, M. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.L.; Simonetti, B.; Klein, K.; Chen, K.E.; Williamson, M.K.; Antón-Plágaro, C.; Shoemark, D.K.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Bauer, M.; Hollandi, R.; et al. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science 2020, 370, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Weyhern, C.H.; Kaufmann, I.; Neff, F.; Kremer, M. Early evidence of pronounced brain involvement in fatal COVID-19 outcomes. Lancet 2020, 395, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinhardt, J.; Radke, J.; Dittmayer, C.; Franz, J.; Thomas, C.; Mothes, R.; Laue, M.; Schneider, J.; Brünink, S.; Greuel, S.; et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, N.; Day, R.; Newcombe, J.; Talbot, P.J. Neuroinvasion by human respiratory coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 8913–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Han, Y.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Gupta, V.; Wang, P.; Duan, X.; Tang, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Jaffré, F.; et al. A Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-based Platform to Study SARS-CoV-2 Tropism and Model Virus Infection in Human Cells and Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 125–136.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, L.; Alivernini, S.; Tolusso, B.; Elmesmari, A.; Somma, D.; Perniola, S.; Paglionico, A.; Petricca, L.; Bosello, S.L.; Carfì, A.; et al. COVID-19 and RA share an SPP1 myeloid pathway that drives PD-L1+ neutrophils and CD14+ monocytes. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e147413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheeswaran, L.; Gokani, S.A.; Luke, L.; Klyvyte, G.; Espehana, A.; Garden, E.M.; Tarantino, A.; Al Omari, B.; Philpott, C.M. Assessment of COVID-19-related olfactory dysfunction and its association with psychological, neuropsychiatric, and cognitive symptoms. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1165329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Manan, H.; de Jesus, R.; Thaploo, D.; Hummel, T. Mapping the Olfactory Brain: A Systematic Review of Structural and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Changes Following COVID-19 Smell Loss. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Zaiko, T.; Kilner-Pontone, N.; Ho, C.-Y. Mechanisms of COVID-19-associated olfactory dysfunction. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2024, 50, e12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xydakis, M.S.; Albers, M.W.; Holbrook, E.H.; Lyon, D.M.; Shih, R.Y.; Frasnelli, J.A.; Pagenstecher, A.; Kupke, A.; Enquist, L.W.; Perlman, S. Post-viral effects of COVID-19 in the olfactory system and their implications. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.M.; Khaleeq, A.; Ali, U.; Syeda, H. Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Bai, W.Z.; Hashikawa, T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may be at least partially responsible for the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, J.; Streit, S.; Dittmayer, C.; Manitius, R.V.; Radbruch, H.; Heppner, F.L. The neurobiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 25, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Zohrabian, V.M. Neuroradiologists, Be Mindful of the Neuroinvasive Potential of COVID-19. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, E37–E39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, Z.; Duan, J.; Hashimoto, K.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Yang, C. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P.E.; Chappell, M.C.; Ferrario, C.M.; Tallant, E.A. Distinct roles for ANG II and ANG-(1–7) in the regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in rat astrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 290, C420–C426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowrisankar, Y.V.; Clark, M.A. Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6 expression in astrocytes: Role of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 437, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wang, K.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wen, C.; Xu, Z. The spatial and cell-type distribution of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in the human and mouse brain. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 573095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschke, J.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Hagel, C.; Sperhake, J.P.; Schröder, A.S.; Edler, C.; Mushumba, H.; Fitzek, A.; Allweiss, L.; Dandri, M.; et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: A post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilinska, K.; Jakubowska, P.; Von Bartheld, C.S.; Butowt, R. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Entry Proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in Cells of the Olfactory Epithelium: Identification of Cell Types and Trends with Age. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueha, R.; Kondo, K.; Kagoya, R.; Shichino, S.; Shichino, S.; Yamasoba, T. ACE2, TMPRSS2, and Furin expression in the nose and olfactory bulb in mice and humans. Rhinology 2021, 59, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramani, A.; Mueller, L.; Niklas Ostermann, P.; Gabriel, E.; Islam Pranty, A.; Mueller-Shiffmann, A.; Mariappan, A.; Goureau, O.; Gruell, H.; Walker, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 targets neurons of 3D human brain organoids. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e106230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.-H.; Chen, Q.; Gu, H.-J.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.-X.; Huang, X.-Y.; Liu, S.-S.; Zhang, N.-N.; Li, X.-F.; Xiong, R.; et al. A Mouse Model of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 124–133.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Yan, W.; Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Ma, K.; Xu, D.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. BMJ 2020, 368, m1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, J.; Kremer, S.; Merdji, H.; Clere-Jehl, R.; Schenck, M.; Kummerlen, C.; Collange, O.; Boulay, C.; Fafi-Kremer, S.; Ohana, M.; et al. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2268–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyiadji, N.; Shahin, G.; Noujaim, D.; Stone, M.; Patel, S.; Griffith, B. COVID-19-associated Acute Hemorrhagic Necrotizing Encephalopathy: CT and MRI Features. Radiology 2020, 296, E119–E120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Tang, A.; He, Y.; Fan, J.; Yang, Q.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H. Neurological complications caused by SARS-CoV-2. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0013124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molaverdi, G.; Kamal, Z.; Safavi, M.; Shafiee, A.; Mozhgani, S.-H.; Ghobadi, M.Z.; Goudarzvand, M. Neurological complications after COVID-19: A narrative review. eNeurologicalSci 2023, 33, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.W.; Brann, D.H.; Farruggia, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Pellegrino, R.; Tsukahara, T.; Weinreb, C.; Joseph, P.V.; Larson, E.D.; Parma, V.; et al. COVID-19 and the chemical senses: Supporting players take center stage. Neuron 2020, 10, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butowt, R.; Meunier, N.; Bryche, B.; von Bartheld, C.S. The olfactory nerve is not a likely route to brain infection in COVID-19: A critical review of data from humans and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butowt, R.; Bilinska, K.; von Bartheld, C.S. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: New insights into the underlying mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Wang, D.Y. COVID-19 Anosmia: High Prevalence, Plural Neuropathogenic Mechanisms, and Scarce Neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2? Viruses 2021, 13, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Las Casas Lima, M.H.; Brusiquesi Cavalcante, A.L.; Correia Leão, S. Pathophysiological relationship between COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction: A systematic review. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bartheld, C.S.; Butowt, R. New evidence suggests SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion along the nervus terminalis rather than the olfactory pathway. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 147, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Finlay, J.B.; Ko, T.; Goldstein, B.J. Long-term olfactory loss post-COVID-19: Pathobiology and potential therapeutic strategies. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 10, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Gu, J.; Gu, Z.; Du, C.; Huang, X.; Xing, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, A.; Hu, X.; Huo, J. Olfactory Dysfunction in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Review. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 783249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Yoo, S.J.; Clijsters, M.; Backaert, W.; Vanstapel, A.; Speleman, K.; Lietaer, C.; Choi, S.; Hether, T.D.; Marcelis, L.; et al. Visualizing in deceased COVID-19 patients how SARS-CoV-2 attacks the respiratory and olfactory mucosae but spares the olfactory bulb. Cell 2021, 184, 5932–5949.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brann, D.H.; Tsukahara, T.; Weinreb, C.; Lipovsek, M.; Van den Berge, K.; Gong, B.; Chance, R.; Macaulay, I.C.; Chou, H.-J.; Fletcher, R.B.; et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgin, E. The science behind COVID’s assault on smell. Nature 2022, 606, S5–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butowt, R.; von Bartheld, C.S. The route of SARS-CoV-2 to brain infection: Have we been barking up the wrong tree? Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukahara, T.; Brann, D.H.; Datta, S.R. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2-associated anosmia. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Clijsters, M.; Choi, S.; Backaert, W.; Claerhout, M.; Couvreur, F.; Van Breda, L.; Bourgeois, F.; Speleman, K.; Klein, S.; et al. Anatomical barriers against SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion at vulnerable interfaces visualized in deceased COVID-19 patients. Neuron 2022, 110, 3919–3935.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Zheng, J.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. SARS-CoV-2 infection of sustentacular cells disrupts olfactory signaling pathways. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e160277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodoulian, L.; Tuberosa, J.; Rossier, D.; Boillat, M.; Kan, C.; Pauli, V.; Egervari, K.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Landis, B.N.; Carleton, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptors and Entry Genes Are Expressed in the Human Olfactory Neuroepithelium and Brain. iScience 2020, 23, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saigh, N.N.; Harb, A.A.; Abdalla, S. Receptors Involved in COVID-19-Related Anosmia: An Update on the Pathophysiology and the Mechanistic Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryche, B.; St Albin, A.; Murri, S.; Lacôte, S.; Pulido, C.; Ar Gouilh, M.; Lesellier, S.; Servat, A.; Wasniewski, M.; Picard-Meyer, E.; et al. Massive transient damage of the olfactory epithelium associated with infection of sustentacular cells by SARS-CoV-2 in golden Syrian hamsters. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, S.F.; Yan, L.M.; Chin, A.W.H.; Fung, K.; Choy, K.T.; Wong, A.Y.L.; Kaewpreedee, P.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Nicholls, J.M.; et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature 2020, 583, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, G.D.; Lazarini, F.; Levallois, S.; Hautefort, C.; Michel, V.; Larrous, F.; Verillaud, B.; Aparicio, C.; Wagner, S.; Gheusi, G.; et al. COVID-19-related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigliano, E.; Dell’Aquila, M.; Vetrugno, G.; Grassi, S.; Amirhassankhani, S.; Amadoro, G.; Oliva, A.; Arena, V. Transdiaphragmatic autopsy approach: Our experience in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Virchows Arch. 2023, 482, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aquila, M.; Cafiero, C.; Micera, A.; Stigliano, E.; Ottaiano, M.P.; Benincasa, G.; Schiavone, B.; Guidobaldi, L.; Santacroce, L.; Pisconti, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-Related Olfactory Dysfunction: Autopsy Findings, Histopathology, and Evaluation of Viral RNA and ACE2 Expression in Olfactory Bulbs. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, G.D.; Perraud, V.; Alvarez, F.; Vieites-Prado, A.; Kim, S.; Kergoat, L.; Coleon, A.; Trüeb, B.S.; Tichit, M.; Piazza, A.; et al. Neuroinvasion and anosmia are independent phenomena upon infection with SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clijsters, M.; Khan, M.; Backaert, W.; Jorissen, M.; Speleman, K.; Van Bulck, P.; Van Den Bogaert, W.; Vandenbriele, C.; Mombaerts, C.; Van Gerven, L. Protocol for postmortem bedside endoscopic procedure to sample human respiratory and olfactory cleft mucosa, olfactory bulbs, and frontal lobe. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonini, L.; Frijia, F.; Ali, A.L.; Foffa, I.; Vecoli, C.; De Gori, C.; De Cori, S.; Baroni, M.; Aquaro, G.D.; Maremmani, C.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of COVID-19-Related Olfactory Deficiency: Unraveling Associations with Neurocognitive Disorders and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazhytska, M.; Kodra, A.; Hoagland, D.A.; Frere, J.; Fullard, J.F.; Shayya, H.; McArthur, N.G.; Moeller, R.; Uhl, S.; Omer, A.D.; et al. Non-cell-autonomous disruption of nuclear architecture as a potential cause of COVID-19-induced anosmia. Cell 2022, 185, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saussez, S.; Lechien, J.R.; Hopkins, C. Anosmia: An evolution of our understanding of its importance in COVID-19 and what questions remain to be answered. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 278, 2187–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilinska, K.; von Bartheld, C.S.; Butowt, R. Expression of the ACE2 virus entry protein in the nervus terminalis reveals the potential for an alternative route to brain infection in COVID-19. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 674123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellford, S.A.; Moseman, E.A. Olfactory immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschenbaum, D.; Imbach, L.L.; Ulrich, S.; Rushing, E.J.; Keller, E.; Reimann, R.R.; Frauenknecht, K.B.M.; Lichtblau, M.; Witt, M.; Hummel, T.; et al. Inflammatory olfactory neuropathy in two patients with COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 396, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziuzia-Januszewska, L.; Januszewski, M. Pathogenesis of Olfactory Disorders in COVID-19. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P.; Luscher, T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3038–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H.K.; Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M. COVID-19-a vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, T. Neurological infection with SARS-CoV-2—The story so far. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.B.; Brann, D.H.; Hachem, R.A.; Jang, D.W.; Oliva, A.D.; Ko, T.; Gupta, R.; Wellford, S.A.; Moseman, E.A.; Jang, S.S.; et al. Persistent post-COVID-19 smell loss is associated with immune cell infiltration and altered gene expression in olfactory epithelium. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eadd0484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doty, R.L. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: Pathology and long-term implications for brain health. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafiero, C.; Micera, A.; Re, A.; Postiglione, L.; Cacciamani, A.; Schiavone, B.; Benincasa, G.; Palmirotta, R. Could Small Neurotoxins-Peptides be Expressed during SARS-CoV-2 Infection? Curr. Genom. 2021, 22, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, J.B.; Gallagher, L.; Joseph, P.V.; Reed, D.; Gudis, D.A.; Overdevest, J.B. Qualitative Olfactory Dysfunction and COVID-19: An Evidence-Based Review with Recommendations for the Clinician. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2023, 37, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-Y.; Salimian, M.; Hegert, J.; O’Brien, J.; Gyeong Choi, S.; Ames, H.; Morris, M.; Papadimitriou, J.C.; Mininni, J.; Niehaus, P.; et al. Postmortem Assessment of Olfactory Tissue Degeneration and Microvasculopathy in Patients with COVID-19. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.P.; Brozzetti, L.; Cardobi, N.; Sacchetto, L.; Gibellini, D.; Montemezzi, S.; Cheli, M.; Manganotti, P.; Monaco, S.; Zanusso, G. Persistent chemosensory dysfunction in a young patient with mild COVID-19 with partial recovery 15 months after the onset. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 43, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.P.; Turner, J.; May, L.; Reed, R. A genetic model of chronic rhinosinusitis-associated olfactory inflammation reveals reversible functional impairment and dramatic neuroepithelial reorganization. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 2324–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Reed, R.R.; Lane, A.P. Chronic Inflammation Directs an Olfactory Stem Cell Functional Switch from Neuroregeneration to Immune Defense. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 501–513.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadoro, G.; Latina, V.; Stigliano, E.; Micera, A. COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s Disease Share Common Neurological and Ophthalmological Manifestations: A Bidirectional Risk in the Post-Pandemic Future. Cells 2023, 12, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto-Urata, M.; Urata, S.; Kagoya, R.; Imamura, F.; Nagayama, S.; Reyna, R.A.; Maruyama, J.; Yamasoba, T.; Kondo, K.; Hasegawa-Ishii, S.; et al. Prolonged and extended impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on the olfactory neurocircuit. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastassopoulou, C.; Davaris, N.; Ferous, S.; Siafakas, N.; Fotini, B.; Anagnostopoulos, K.; Tsakris, A. Olfactory Dysfunction in COVID-19 and Long COVID. Lifestyle Genom. 2024, 17, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, L.M. Neuroscience of disease: COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction: A looming wave of dementia? J. Neurophysiol. 2022, 128, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, A.P.L.; Leung, M.K.; Lau, B.W.M.; Ngai, S.P.C.; Lau, W.K.W. Olfactory dysfunction: A plausible source of COVID-19-induced neuropsychiatric symptoms. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1156914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirker-Kees, A.; Platho-Elwischger, K.; Hafner, S.; Redlich, K.; Baumgartner, C. Hyposmia Is Associated with Reduced Cognitive Function in COVID-19: First Preliminary Results. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2021, 50, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xia, F.; Jiao, X.; Lyu, X. Long COVID and its association with neurodegenerative diseases: Pathogenesis, neuroimaging, and treatment. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1367974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granvik, C.; Andersson, S.; Andersson, L.; Brorsson, C.; Forsell, M.; Ahlm, C.; Normark, J.; Edin, A. Olfactory dysfunction as an early predictor for post-COVID condition at 1-year follow-up. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarello, B.J.; Jacobson, P.T.; Tervo, J.P.; Waring, N.A.; Gudis, D.A.; Goldberg, T.E.; Devanand, D.P.; Overdevest, J.B. Olfaction and neurocognition after COVID-19: A scoping review. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1198267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, M. The rhinencephalon. Acta Anat. 1970, 76, 157–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudry, Y.; Lemogne, C.; Malinvaud, D.; Consoli, S.-M.; Bonfils, P. Olfactory system and emotion: Common substrates. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2011, 128, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.L. Olfactory System. In The Human Nervous System; Paxinos, G., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 979–998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Lane, G.; Cooper, S.L.; Kahnt, T.; Zelano, C. Characterizing functional pathways of the human olfactory system. eLife 2019, 8, e47177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, G.; Zhou, G.; Noto, T.; Zelano, C. Assessment of direct knowledge of the human olfactory system. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 329, 113304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennis, M.; Puche, A.C.; Holy, T.; Shipley, M.T. The Olfactory System. In The Rat Nervous System, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 761–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Olofsson, J.K.; Koubeissi, M.Z.; Menelaou, G.; Rosenow, J.; Schuele, S.U.; Xu, P.; Voss, J.L.; Lane, G.; Zelano, C. Human hippocampal connectivity is stronger in olfaction than other sensory systems. Prog. Neurobiol. 2021, 201, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rijzingen, I.M.S.; Gispen, W.H.; Spruijt, B.M. Olfactory bulbectomy temporarily impairs Morris maze performance: An ACTH(4–9) analog accellerates return of function. Physiol. Behav. 1995, 58, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozumi, S.; Nakagawasai, O.; Tan-No, K.; Niijima, F.; Yamadera, F.; Murata, A.; Arai, Y.; Yasuhara, H.; Tadano, T. Characteristics of changes in cholinergic function and impairment of learning and memory-related behavior induced by olfactory bulbectomy. Behav. Brain Res. 2003, 138, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitruskova, B.; Orendácová, J.; Raceková, E. Fluoro Jade-B detection of dying cells in the SVZ and RMS of adult rats after bilateral olfactory bulbectomy. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2005, 25, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkova, N.; Vorobyov, V.; Medvinskaya, N.; Aleksandrova, I.; Nesterova, I. Interhemispheric EEG differences in olfactory bulbectomized rats with different cognitive abilities and brain beta-amyloid levels. Brain Res. 2008, 1232, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterova, I.V.; Bobkova, N.V.; Medvinskaia, N.I.; Samokhin, A.N.; Aleksandrova, I. Morpho-functional state of neurons in temporal cortex and hippocampus in bulbectomized rats with different level of spatial memory. Morfologiia 2007, 131, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shioda, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Han, F.; Moriguchi, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hino, M.; Fukunaga, K. A novel cognitive enhancer, ZSET1446/ST101, promotes hippocampal neurogenesis and ameliorates depressive behavior in olfactory bulbectomized mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 333, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Medina, J.C.; Juarez, I.; Venancio-Garcia, E.; Cabrera, S.N.; Menard, C.; Yu, W.; Flores, G.; Mechawar, N.; Quirion, R. Impaired structural hippocampal plasticity is associated with emotional and memory deficits in the olfactory bulbectomized rat. Neuroscience 2013, 236, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkova, N.; Vorobyov, V.; Medvinskaya, N.; Nesterova, I.; Tatarnikova, O.; Nekrasov, P.; Samokhin, A.; Deev, A.; Sengpiel, F.; Koroev, D.; et al. Immunization Against Specific Fragments of Neurotrophin p75 Receptor Protects Forebrain Cholinergic Neurons in the Olfactory Bulbectomized Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 53, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanichev, M.; Markov, D.; Pasikova, N.; Gulyaeva, N. Behavior and the cholinergic parameters in olfactory bulbectomized female rodents: Difference between rats and mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 297, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedogreeva, O.A.; Evtushenko, N.A.; Manolova, A.O.; Peregud, D.I.; Yakovlev, A.A.; Lazareva, N.A.; Gulyaeva, N.V.; Stepanichev, M.Y. Oxidative Damage of Proteins Precedes Loss of Cholinergic Phenotype in the Septal Neurons of Olfactory Bulbectomized Mice. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2021, 18, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Tabasi, F.; Abdolsamadi, M.; Dehghan, S.; Dehdar, K.; Nazari, M.; Javan, M.; Mirnajafi-Zadeh, J.; Raoufy, M.R. Disrupted connectivity in the olfactory bulb-entorhinal cortex-dorsal hippocampus circuit is associated with recognition memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Kurokawa, K.; Hong, L.; Miyagawa, K.; Mochida-Saito, A.; Takeda, H.; Tsuji, M. Correlation between the reduction in hippocampal SirT2 expression and depressive-like behaviors and neurological abnormalities in olfactory bulbectomized mice. Neurosci. Res. 2022, 182, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lu, J.; Wei, L.; Yao, M.; Yang, H.; Lv, P.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Olfactory deficit: A potential functional marker across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1309482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stadio, A.; Brenner, M.J.; De Luca, P.; Albanese, M.; D’Ascanio, L.; Ralli, M.; Roccamatisi, D.; Cingolani, C.; Vitelli, F.; Camaioni, A.; et al. Olfactory Dysfunction, Headache, and Mental Clouding in Adults with Long-COVID-19: What Is the Link between Cognition and Olfaction? A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain. Sci. 2022, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, L.S.; Salsano, E.; Grimaldi, M. Magnetic resonance imaging alteration of the brain in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and anosmia. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1028–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.E.; Gurdasani, D.; Helbok, R.; Ozturk, S.; Fraser, D.D.; Filipović, S.R.; Peluso, M.J.; Iwasaki, A.; Yasuda, C.L.; Bocci, T.; et al. COVID-19-associated neurological and psychological manifestations. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathia-Dey, N.; Heinbockel, T. The olfactory system as marker of neurodegeneration in aging, neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, M.; Ricci, M.; Pagliaro, M.; Gerace, C. Anosmia predicts memory impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: Results of a neuropsychological cohort study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 275, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llana, T.; Mendez, M.; Garces-Arilla, S.; Hidalgo, V.; Mendez-Lopez, M.; Juan, M.-C. Association between olfactory dysfunction and mood disturbances with objective and subjective cognitive deficits in long-COVID. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1076743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kausel, L.; Figueroa-Vargas, A.; Zamorano, F.; Stecher, X.; Aspé-Sánchez, M.; Carvajal-Paredes, P.; Márquez-Rodríguez, V.; Martínez-Molina, M.P.; Román, C.; Soto-Fernández, P.; et al. Patients recovering from COVID-19 who presented with anosmia during their acute episode have behavioral, functional, and structural brain alterations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchetti, G.; Agosta, F.; Canu, E.; Basaia, S.; Barbieri, A.; Cardamone, R.; Bernasconi, M.P.; Castelnovo, V.; Cividini, C.; Cursi, M.; et al. Cognitive, EEG, and MRI features of COVID-19 survivors: A 10-month study. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 3400–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, L.; La Rocca, M.; Quaranta, N.; Iannuzzi, L.; Vecchio, E.; Brunetti, A.; Gentile, E.; Dibattista, M.; Lobasso, S.; Bevilacqua, V.; et al. Prefrontal dysfunction in post-COVID-19 hyposmia: An EEG/fNIRS study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1240831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccioli, L.; Sighinolfi, G.; Mitolo, M.; Ferri, L.; Rochat, M.J.; Pensato, U.; Taruffi, L.; Testa, C.; Masullo, M.; Cortelli, P.; et al. Cognitive and functional connectivity impairment in post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 38, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirinzi, T.; Maftei, D.; Maurizi, R.; Albanese, M.; Simonetta, C.; Bovenzi, R.; Bissacco, J.; Mascioli, D.; Boffa, L.; Di Certo, M.G.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Hyposmia Does Not Exhibit Main Neurodegeneration Markers in the Olfactory Pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 8921–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.A.; Kuivanen, S.; Lampinen, R.; Mussalo, L.; Hron, T.; Závodná, T.; Ojha, R.; Krejčík, Z.; Saveleva, L.; Tahir, N.A.; et al. Human-derived air-liquid interface cultures decipher Alzheimer’s disease-SARS-CoV-2 crosstalk in the olfactory mucosa. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azcue, N.; Gomez-Esteban, J.C.; Acera, M.; Tijero, B.; Fernandez, T.; Ayo-Mentxakatorre, N.; Pérez-Concha, T.; Murueta-Goyena, A.; Lafuente, J.V.; Prada, Á.; et al. Brain fog of post-COVID-19 condition and chronic fatigue syndrome, same medical disorder? J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Alonso, C.; Valles-Salgado, M.; Delgado-Alvarez, A.; Yus, M.; Gomez-Ruiz, N.; Jorquera, M.; Polidura, C.; Gil, M.J.; Marcos, A.; Matías-Guiu, J.; et al. Cognitive dysfunction associated with COVID-19: A comprehensive neuropsychological study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 150, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, R.; Dini, M.; Rosci, C.; Capozza, A.; Groppo, E.; Reitano, M.R.; Allocco, E.; Poletti, B.; Brugnera, A.; Bai, F.; et al. One-year cognitive follow-up of COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 2006–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, J.; Payne, M.; Cancian, E.; Plonka, A.; Dumas, L.E.; Chirio, D.; Demonchy, É.; Risso, K.; Askenazy-Gittard, F.; Guevara, N.; et al. Correlations between persistent olfactory and semantic memory disorders after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, R.F.; Neto, D.B.; Oliveira, J.V.R.; Magalhães Santos, J.; Alves, J.V.R.; Guedes, B.F.; Nitrini, R.; de Araújo, A.L.; Oliveira, M.; Brunoni, A.R.; et al. COVID-19 study group. Association between chemosensory impairment with neuropsychiatric morbidity in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: Results from a multidisciplinary cohort study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, G.; Monaghan, A.; Xue, F.; Duggan, E.; Romero-Ortuno, R. Comprehensive clinical characterisation of brain fog in adults reporting long COVID symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopishinskaia, S.; Lapshova, D.; Sherman, M.; Velichko, I.; Voznesensky, N.; Voznesenskaia, V. Clinical features in Russian patients with COVID-associated Parosmia/Phanthosmia. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Alemanno, F.; Houdayer, E.; Parma, A.; Spina, A.A.D.; Scatolini, A.; Angelone, S.; Brugliera, L.; Tettamanti, A.; Beretta, L.; Iannaccone, S. COVID-19 cognitive deficits after respiratory assistance in the subacute phase: A COVID rehabilitation unit experience. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 246590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, M.; Raggi, A.; Pilotto, A.; Cristillo, V.; Guastafierro, E.; Toppo, C.; Magnani, F.G.; Sattin, D.; Mariniello, A.; Silvaggi, F.; et al. Neurological and mental health symptoms associated with post-COVID-19 disability in a sample of patients discharged from a COVID-19 Ward: A secondary analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, I.H.; Magnus, P.; Trogstad, L. Excess risk and clusters of symptoms after COVID-19 in a large Norwegian cohort. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.D.; Yu, S.E.; Salvatore, B.; Goldberg, Z.; Bowers, E.M.R.; Moore, J.A.; Phan, B.; Lee, S.E. Olfactory and neurological outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 from acute infection to recovery. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 1019274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares-Júnior, J.W.L.; Oliveira, D.N.; da Silva, J.B.S.; Feitosa, W.L.Q.; Sousa, A.V.M.; Cunha, L.C.V.; de Brito Gaspar, S.; Pereira Gomes, C.M.; de Oliveira, L.L.B.; Moreira-Nunes, C.A.; et al. Long-Covid cognitive impairment: Cognitive assessment and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping correlation in a Brazilian cohort. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 947583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]