Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-based immunotherapy has shown considerable promise in cancer treatment by redirecting immune effector cells to recognize and eliminate tumor cells in an antigen-specific manner. While CAR-T cells bearing tumor-specific CARs have shown remarkable success in treating some hematological malignancies, their clinical application is limited by cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, and graft-versus-host disease. In contrast, CAR–natural killer (NK) cells retain their multiple forms of natural anti-tumor capabilities without the pathological side effects and are compatible with allogeneic “off-the-shelf” application by not requiring prior activation signaling. Despite CAR-NK therapies showing promising results in hematological malignancies, they remain limited as effector cells against solid tumors. This is primarily due to the complex, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), characterized by hypoxia, nutrient depletion, lactate-induced acidosis, and inhibitory soluble factors. Collectively, these significantly impair NK cell functionality. This review examines challenges faced by CAR-NK therapy in combating solid tumors and outlines strategies to reduce them. Barriers include tumor antigen heterogeneity, immune escape, trogocytosis-mediated fratricide, rigid structural and metabolic barriers in the TME, immunosuppressive factors, and defective homing and cell persistence of CAR-NK cells. We also emphasize the impact of combining other complementary immunotherapies (e.g., multi-specific immune engagers and immunomodulatory agents) that further strengthen CAR-NK efficacy. Finally, we highlight critical research gaps in CAR-NK therapy and propose that cutting-edge technologies are required for successful clinical translation in solid tumor treatment.

1. Introduction

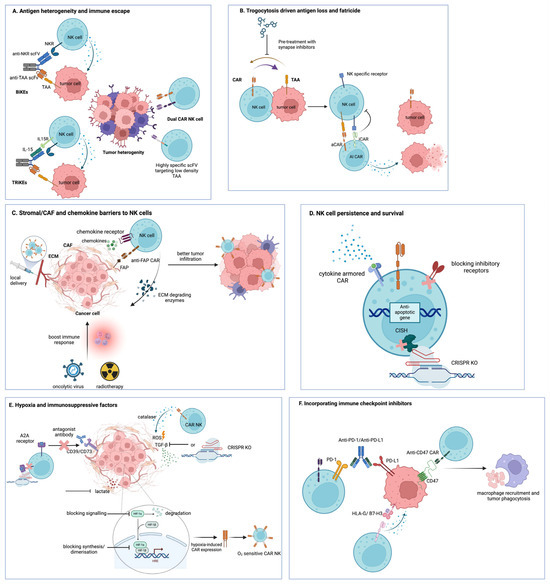

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–natural killer (NK) cells carry lower risks of cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, and graft-versus-host disease than CAR-T cells and are compatible with allogeneic, off-the-shelf production. However, efficacy in solid tumors remains constrained by the immunosuppressive and physically restrictive tumor microenvironment (TME) [1]. This review discusses the main barriers that limit the effectiveness of CAR-NK cells in the solid TME, including antigen heterogeneity, immune evasion, metabolic suppression, trogocytosis-induced fratricide, and inadequate cell persistence We also outline novel engineering and combinatorial strategies designed to reduce these hurdles and advance CAR-NK therapy towards successful clinical application in solid tumor settings (summarized in Table 1 and Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the major TME barriers and resistance mechanisms impairing CAR-NK cell function, the corresponding engineering strategies to reduce them, and their reported outcomes, which are all derived from preclinical studies *.

Table 2.

Current CAR-NK trials in solid tumors *.

Figure 1.

Summary of CAR-NK engineering strategies to overcome major TME barriers in solid tumors. (A) Antigen heterogeneity and antigen-low tumor cells are addressed by NK cell engagers (BiKEs and TriKEs), which bridge NK receptors to tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and, in the case of TriKEs, deliver IL-15 to support NK survival, as well as dual-CAR-NK cells and highly specific scFvs that broaden target recognition of low-density TAAs. (B) Trogocytosis-driven antigen loss and CAR-NK fratricide are limited by AI-CARs based on NK-specific inhibitory receptors and by pharmacological inhibition of immune synapse formation. (C) Stromal, CAF, and chemokine barriers are targeted using FAP-specific CAR-NK cells, ECM-degrading enzymes, chemokine receptor engineering, oncolytic viruses, radiotherapy, and local delivery strategies to remodel stroma and enhance NK cell infiltration. (D) Hypoxia and metabolite-mediated suppression in the TME are countered by hypoxia-inducible CAR-NK designs, antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase, and the blockade of adenosine-generating pathways (CD39/CD73) or A2A receptors. (E) CAR-NK persistence and survival are enhanced by CISH knockout and cytokine-armored CARs that provide more sustained cytokine signaling. (F) Inhibitory checkpoint pathways are overcome by antibody blockade or CAR-mediated targeting of PD-1/PD-L1, HLA-G, B7-H3, and CD47, promoting tumor cell clearance, including macrophage-mediated phagocytosis. Created with BioRender.com (https://www.biorender.com/).

2. NK Cells in the TME

The TME represents a complex, highly immunosuppressive environment that leads to significant challenges to the function and therapeutic efficacy of NK cells. The hostile TME comprises various immunosuppressive cells, including regulatory T cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). Together, these populations limit immune cell infiltration into tumors and dampen their cytotoxic activity through inhibitory cytokines, nutrient depletion, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [84,85,86,87]. Furthermore, the TME contains numerous inhibitory factors, such as immunosuppressive cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-10 [87], transforming growth factor (TGF)-β [53], metabolic inhibitors, like prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [88], adenosine [89], and enzymatic suppressors, such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), that converts tryptophan into immunosuppressive L-kynurenine metabolites [90,91]. All of these collectively contribute to the immunosuppressive TME, which is further characterized by hypoxia, nutrient depletion, and lactate-induced acidosis. These factors significantly impair NK cell function through several mechanisms, such as downregulation of activation receptors, including NKG2D (natural killer group 2, member D), and the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46). They also upregulate inhibitory checkpoints such as CD94/NKG2A, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing-3 (TIM-3), T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein-4, lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3), and interleukin 1 receptor 8 [92,93]. In addition, they suppress the production of granzyme B, perforin, and interferon (IFN)-γ [94,95]. They also alter cellular metabolism, inhibiting glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation [96]. Furthermore, via chemokine expression modulation, the TME promotes the recruitment of less cytotoxic CD56bright NK cells over the more potent CD56dim NK cells, and the stromal cells create a physical barrier that further prevents the infiltration and trafficking of NK cells towards the tumor targets [97]. Therefore, extensive research has been carried out to understand these immunosuppressive mechanisms in order to engineer CAR-NK cells to better equip them to tackle TME-mediated inhibition and enhance immunotherapeutic potential against solid tumors.

3. Targeting Antigen Heterogeneity in Solid Tumors and Overcoming Immune Escape

Unlike most hematological malignancies, solid tumors are highly heterogeneous in their antigen expression [98], where they often evade immune surveillance by downregulating their targeted antigens [99]. To reduce these challenges, CAR-NK cells can be designed to either increase the binding affinity of the CAR to the low-expression antigens or co-target multiple tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) (Figure 1A). Various techniques, including directed evolution [2], computational modeling [3,4], and phage display [5,6], have been utilized in CAR-T cell studies to design single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) highly specific to these low-density TAAs, resulting in enhanced efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicities. These platforms can also be leveraged for CAR-NK construct optimization. On the other hand, multi-targeting strategies using two independent “dual” CAR-NK cells have been shown to reduce tumor resistance. Dual CAR-NK cells targeting programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2) have shown enhanced cytotoxicity across diverse cancer cell lines, including breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and gastric cancer cells, when compared to mono-specific variants [7]. Similarly, dual CAR-NK cells against CD44-CD24 and CD44–mesothelin illustrated superior killing against triple-negative breast cancer cells, reducing tumor survival to 4–10% compared to 18–25% with single-target CARs [8]. NK cells expressing dual CARs targeting GD2 and NKG2D ligands showed improved recognition of glioblastoma (GBM) cells, achieving a ~2-fold reduction in tumor volume and weight compared to single CAR-treated mice [9]. Similarly, dual-targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and EGFRvIII CAR-NK cells improved the killing of GBM compared to mono-specific CARs [10] (Table 1).

Additionally, multi-specific engagers can be administered along with CAR-NK therapy to address antigenic heterogeneity in solid tumors (Figure 1A). Bispecific killer engager (BiKE) molecules are engineered to simultaneously bind tumor antigens and activate NK receptors such as CD16, NKp30, NKp46, and NKG2D. Building on the BiKEs concept, trispecific killer cell engagers (TriKEs) incorporate an additional functional domain, such as the cytokine IL-15, which further promotes activation, proliferation, and persistence, improving their efficacy in the TME [11]. Various studies have shown the improved cytolytic activity of NKG2D CAR-NK cells when incorporated with BiKEs, achieving over 60% lysis in HER2 breast carcinoma cells [12] and increasing glioblastoma cell killing from 11–13% to 32–43% in EGFR/HER2-targeted models [13]. Current CAR-NK clinical trials show activity against broad/stress-induced targets (for example, PD-L1 and NKG2D) and include multi-antigen recognition strategies (Table 1 and Table 2). In addition to antigen recognition, the CAR construct influences the quality of NK cell function. Incorporating NK cell-specific signaling and adaptor domains, such as 2B4, DNAM-1, DAP10, and DAP12, in combination with NKG2D, enhances activation signaling pathways, promotes degranulation, increases IFN-γ secretion, and improves overall cytotoxicity (Table 1) [14,15].

4. Modulating Trogocytosis to Enhance CAR-NK Function

Trogocytosis refers to the transfer of surface proteins, membrane fragments, or cytoplasmic components from another cell via direct cell-to-cell contact without cell fusion or death [100]. Trogocytosis-mediated immune escape has been documented in CAR-NK therapy [17] and occurs in two major ways. Firstly, it involves the transfer of cell surface receptors from cancer targets to the CAR-expressing effector cells, which leads to the downregulation of target antigens on the tumor cells. Secondly, it involves the transfer of CAR molecules to the tumor targets, resulting in antigen masking and depletion of CAR molecules on the engineered immune cells [101]. Furthermore, trogocytosis mediates fratricide, as CAR-bearing cells may target one another due to acquiring the target antigen, thereby reducing cell viability and anti-tumor efficacy.

Trogocytosis of tumor antigens on CAR-bearing cells can upregulate inhibitory molecules, such as LAG-3 and TIM-3, resulting in CAR cell exhaustion and dysfunction [16]. Trogocytosis in CAR-NK cells also causes metabolic dysregulation, leading to a significant suppression of glycolysis [17]. Addressing these challenges, Li and colleagues [17] designed a dual CAR (AI-CAR) with an activating CAR (aCAR) recognizing tumor antigens (ROR1 or CD19) and an inhibitory CAR (iCAR) targeting an NK-specific antigen (CS1) (Table 1; Figure 1B). When NK cells encounter their trogocytosed antigens, the inhibitory CAR sends out a “don’t-eat-me” signal, preventing fratricide, while the activating CAR ensures the effective recognition and elimination of tumor targets. Additionally, studies have shown that pretreatment of CAR-NK cells with immunological synapse inhibitors, such as Latrunculin A [18] and Cytochalasin D [19], prevents trogocytosis (Table 1; Figure 1B). While metabolic impairment following trogocytosis has been documented, strategies aimed at metabolic rescue have not yet been specifically investigated in detail in CAR-NK cells. However, studies in NK cells more broadly have examined metabolic dysregulation and potential modulatory pathways, which are discussed in more detail later in this review.

5. Addressing Tumor Stroma and Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Resistance

The TME consists of tumor cells, immunosuppressive immune cells, CAFs, complex stromal components, including ECM, basement membranes, and endothelial networks [85,86]. While the initial migration of immune cells towards the tumor targets is mediated via cytokine and chemokine gradients, their infiltration is substantially barricaded by the rigidity of the ECM [102]. CAFs, constituting 80% of the total tumor mass in certain malignancies [103], are the primary contributors of ECM deposition and TME remodeling. These cells secrete various mediators, including IL-6, PGE2, IDO, TGF-β, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), all of which significantly impair NK cell cytotoxicity [20]. Administration of Nintedanib, an anti-fibrotic agent, significantly enhances CAR-NK tumor infiltration and cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer models by suppressing CAF activation, increasing cancer cell killing from ~32% to ~42% (p < 0.0001) [21]. Engineering of CAR-NK cells targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a serine protease overexpressed by CAFs (Figure 1C), has been shown to inhibit tumor progression in non-small cell lung cancer models [104] and cervical cancer models, where anti-FAP CAR-NK-92 cells demonstrated an 1.5-fold increase in CD107a expression and reduced CAF spheroid fluorescence by 50–83% within 34–72 h compared to controls (p < 0.05) [105]. Additionally, designing CAR-NK cells to secrete ECM-degrading enzymes such as heparanase [22], hyaluronidase [23,24], MMP [25], or collagenase [26] may overcome the stromal barriers and enhance CAR-NK penetration in the TME (Figure 1C). Several clinical trials are testing regional delivery of CAR-NK cells via the hepatic artery or intraperitoneally, which aligns with strategies to bypass stromal barriers (Table 2).

6. Enhancing CAR-NK Cell Infiltration and Homing to Tumors

Infiltration of NK cells is mediated via chemokine gradients generated by tumor, stromal, and immune cells within the TME; however, their infiltration remains suboptimal due to the chemokine system dysregulation [27]. Therefore, designing CAR-NK cells expressing tumor-matched chemokine receptors may enhance CAR-NK infiltration (Figure 1C). Studies reported that anti-mesothelin CAR-NK cells with CXCR2 showed enhanced pancreatic tumor infiltration [28], while NKG2D CAR-NK cells co-expressing CXCR1 showed improved migration and infiltration in xenograft models, resulting in a 20% increase in median survival compared to NKG2D CAR-NK cells lacking CXCR1 [29]. Similarly, EGFRvIII-targeting CAR-NK cells with CXCR4 demonstrated superior GBM infiltration and cytotoxicity in vivo, increasing intratumoral accumulation from 10–15 cells/field to around 35 cells/field [30]. Other chemokine receptors, such as CCR5 [31], CCR7 [32,106], and CCR4 [19], have been successfully engineered to enhance NK cell migration (Table 1).

Beyond genetic modification, chemokine receptor profiles can be drastically influenced during the ex vivo expansion of NK cells with specific cytokines. IL-2 and/or IL-15-mediated NK expansion upregulates CXCR3 expression [33,107]. While IL-2 alone upregulates CCR2 expression [34], combining it with glucocorticoids and IL-15 upregulates CXCR3 levels [108]. Finally, IL-18 in culture upregulates CCR7 expression [35]. Again, trogocytosis can also alter chemokine receptor expression; co-culturing of NK cells with CCR7+ K562 cells can lead to the transfer of CCR7 on NK cells, thereby facilitating their migration towards CCL19 and CCL21 ligands [109] (Table 1).

Trafficking of CAR-NK cells can be further enhanced through combination therapies and sophisticated delivery methodologies designed to optimize the TME for lymphocyte recruitment [110]. Approaches to modify the TME include using immunomodulatory agents, such as oncolytic viruses [36] or radiotherapy [25], which can boost tumor inflammation, stimulate immune responses, and improve CAR-NK cell efficacy. Finally, local injection of CAR-NK cells to the tumor sites is a strategic delivery route that has consistently demonstrated to be both safe and effective in preclinical and clinical investigations [37,38] (Table 1 and Table 2). Current clinical studies adopting local delivery/injection routes to enhance trafficking and exposure are listed in Table 2.

7. Modulating Hypoxia and Immunosuppressive Factors in the TME

Tumor hypoxia critically impairs NK cell function, where the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), comprising oxygen-sensitive alpha subunits (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, HIF-3α) and constitutive beta subunits (HIF-1β), triggers detrimental cellular changes [39]. HIF-1α downregulates activating ligands, like MICA and MICB, on tumor cells through MMP-mediated shedding [111] and suppresses the expression levels of critical NK activation markers, including NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 [40], resulting in reduced NK cell cytotoxicity. It further suppresses the production of the degranulation marker CD107a and the secretion of cytotoxic molecules, including granzyme B and perforin, by inhibiting the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 [41]. Therefore, blocking HIF-1α signaling in NK cells has been shown to improve their anti-tumor efficacy [44]. Furthermore, therapeutic agents targeting HIFs, such as those that inhibit their synthesis, dimerization formation, or trigger degradation, are currently being evaluated [112,113] with the potential to be integrated with CAR-NK therapy (Figure 1E). As shown in CAR-T cell studies, engineering CAR-NK cells with a hypoxia-response element [114,115] or oxygen-sensitive subdomains derived from HIF-1α [116,117] only ensures specificity in hypoxic conditions and reduces off-target effects in normoxic environments (Table 1; Figure 1E).

Hypoxic conditions force NK cells to switch to glycolysis from oxidative phosphorylation, which limits their energy availability and impairs their cytotoxicity. The shift towards glycolysis leads to the accumulation of lactate, which suppresses IFN-γ production, downregulates the expression of NKp46, CD107a, and granzyme B, and triggers mitochondrial damage and NK cell apoptosis [42]. Currently, glycolytic inhibitors and lactate dehydrogenase blockers that may counteract these metabolic challenges are being investigated (Figure 1E) [43]. Another way to improve the metabolic dysregulation is simultaneously integrating metabolic regulators, including adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), which enhances mitochondrial function and oxidative phosphorylation capacity [118]. While strategies aimed at metabolic rescue have been primarily investigated in NK cells, there remains a research gap in exploring these approaches within CAR-NK cells. Hypoxia also impairs NK cell functionality by modulating the immunosuppressive cells, such as regulatory T cells, M2 TAMs, and MDSCs, within the TME. CAR-NK cells have been engineered to directly target these immunosuppressive populations, particularly MDSCs [119] and TAMs [120], to enhance their anti-tumor activity (Table 1).

Hypoxia-driven expression of CD39 and CD73 by tumor and regulatory T cells elevates adenosine levels, which further reduces NK cell activity via the adenosine A2A receptor [45]. Blocking of CD73 with antagonist antibodies has been shown to improve CAR-NK efficacy (Figure 1E) [46]. Chambers and colleagues [47] also showed that engineering CAR-NK cells targeting CD73 not only exhibited improved infiltration and cytotoxicity against CD73+ tumor cells but also significantly reduced adenosine production (~0 µM), lowering it below the baseline levels observed in cancer cells cultured alone. Furthermore, deletion of the A2A receptor via genetic editing has shown enhanced CAR-NK mediated killing in preclinical models [48,121,122] (Table 1; Figure 1E).

The secretion of TGF-β from the immunosuppressive cells within the TME downregulates the expression of NK activation receptors NKG2D, DNAM-1, and NKp30 and reduces IFN-γ production [49]. Multiple strategies have been explored to block the immunosuppressive effects of TGF-β, including the silencing of TGFβ-induced miR-27a-5p in vivo [50], the deletion of the TGF-β receptor (TGFβR)-2 [51], and the administration of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor [52], all of which led to enhanced NK cell functionality (Figure 1E). Furthermore, by engineering CAR-NK cells with high affinity, dominant-negative TGF-β receptors have been shown to resist the suppressive effects of TGF-β while maintaining their therapeutic potency [53,123]. TGF-β also reduces NK cell activity via the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [54]. Addressing this issue, Liu and colleagues [55] designed a CAR-NK cell targeting HER1 to co-express catalase that successfully neutralized the accumulated ROS hydrogen peroxide in the TME and enhanced CAR-NK cell functionality (Table 1; Figure 1E).

Hypoxia-induced loss of NK cytotoxicity can also be rescued by treating CAR-NK cells with cytokines, like IL-2, IL-15, IL-18, and IL-21, which improve survival, proliferation, and cytotoxic activity [44,56,124,125,126,127]. Additionally, BiKEs and TriKEs have been designed to further boost CAR-NK cell activity by simultaneously targeting tumor antigens and engaging CD16 on NK cells, with TriKEs additionally delivering IL-15 to support NK cell persistence and proliferation [56,128]. These approaches largely benefit CAR-NK anti-tumor efficacy, as the activation of BiKEs and TriKEs depends on CD16, and hypoxia has been shown not to impact CD16-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [125]. Furthermore, research is being conducted on novel NK cell engagers that can activate receptors, like NKp46, NKp30, and NKG2D, which are significantly suppressed under hypoxic conditions [129,130] (Table 1).

8. Improving NK Cell Persistence and Survival

The inherent short lifespan and high turnover rates in vivo constrain NK cell persistence in solid tumors compared to other lymphocytes [131]. Their sustained functionality is dependent on the maintenance of the homeostatic balance between activating and inhibitory signaling, as overstimulation often leads to NK cell exhaustion [132]. This can be reduced by blocking the inhibitory receptors such as KIRs, PD-1, TIGIT, NKG2A, and TIM-3 (Figure 1D) [84,133]. Extensive research is being carried out investigating various checkpoint blockade therapies targeting NK cell inhibitory receptors (Section 9).

Another strategy to boost CAR-NK cell proliferation, persistence, and survival is by supplementing various cytokines such as IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18. Armoring CAR-NK cells with IL-15 in their construct enhances their in vivo persistence and improves their metabolic fitness, leading to enhanced anti-tumor activity (Figure 1D) [57,126]. Another strategy to enhance their persistence is by targeting the negative regulators of cytokine signaling, such as the cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CIS). CIS is a negative regulator of both IL-2 and IL-15 signaling, and knocking out of the cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein gene (CISH) using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated nuclease 9 (Cas9) in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived CAR-NK cells have been shown to significantly improve metabolic fitness through enhanced mitochondrial activity and mTOR signaling, resulting in overall improvement of NK performance and persistence (Figure 1D) [58]. Additionally, co-expressing anti-apoptotic genes, such as BCL-2 or BCL-XL, may also improve CAR-NK cell survival (Figure 1D) [59]. Another approach to ensure enhanced metabolic adaptation of CAR-NK cells within the TME is to increase the essential amino acid uptake. Increased expression of specific amino acid transport molecules, particularly SLC1A5 and the SLC3A2/SLC7A5 transporter complex, facilitates growth, proliferation, and persistence of CAR-NK cells (Table 1) [60].

9. Incorporating Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

9.1. PD-1

Immune checkpoint inhibitors play a crucial role in regulating persistent immune responses. In the TME, the tumor cells exploit immune checkpoint pathways to suppress NK cell function, predominantly through the PD-1/PD-L1 axis (Figure 1F). PD-1 is abundantly expressed on activated NK cells, and upon ligation with the PD-L1 receptor overexpressed in tumor cells, leads to immunosuppression, thereby impairing NK cell functionality [134]. To counteract this, CAR-NK cells have been engineered with chimeric costimulatory converting receptors that convert the PD-1 inhibitory signals into activation. Combining the extracellular domain of PD-1 with NKG2D signaling components, along with the 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain, has demonstrated robust in vitro cytotoxicity in various cancer cell models [61] and induced significant gasdermin E-dependent pyroptosis in lung cancer models [62]. A dual CAR incorporating PD-1 and NKG2D recognition domains with DAP10 signaling showed an approximate 27% and 50% increase in TNF-α and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) production, respectively, enhanced cytotoxicity, and triggered apoptosis in gastric cancer cells [63]. Another innovative engineering of CAR-NK-92, combining IL-15Rα-sushi/IL-15 complexes with PD-1 signal inverters, demonstrated superior persistence and cytotoxicity against pancreatic cancer cells [64]. Additionally, using CRISPR/Cas9 to KO inhibitory genes, such as a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17 (ADAM-17) and PD-1, enhances NK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine production [65] (Table 1).

9.2. PD-L1

Similarly, CAR-NK cells targeting PD-L1 have demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity across multiple solid tumor models. High-affinity NK (haNK) cells engineered NK-92 cells expressing endoplasmic reticulum-retained IL-2, with PD-L1 CAR effectively recognized and eliminated various tumor targets, including triple-negative breast cancer and lung, urogenital, gastric, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [66,135]. Furthermore, these engineered CAR-NK cells significantly reduced immunosuppressive macrophages and MDSCs expressing high PD-L1 levels [66,135]. Integrating these PD-L1 haNK cells with anti-PD1 and N-803, an IL-15 super agonist, demonstrated superior tumor growth control in preclinical models [66]. Fourth-generation PD-L1 CAR-NK cells co-expressing IL-15 further enhanced the persistence and functionality of CAR-NK cells against various tumor cell lines [68] (Table 1).

In heterogeneous tumor models, PD-L1 CAR-NK cells successfully eliminated resistant populations that escaped T cell-mediated killing due to antigen presentation defects and PD-L1 upregulation [67]. A novel atezolizumab-based PD-L1 CAR-NK cell showed potent activity against tumors overexpressing PD-L1 and exhibited a self-amplifying effect by inducing PD-L1 expression on PD-L1 low tumor cells, thereby enhancing cytotoxicity [69]. CAR-NK cells derived from hematopoietic progenitor cells and human pluripotent stem cells targeting PD-L1 showed enhanced anti-tumor activity both in vitro and in vivo. In addition to lysing tumors expressing high levels of PD-L1, they also revived exhausted T cells, thereby promoting a stronger immune response [136,137]. Dual CAR-NK cells targeting PD-L1 and folate receptor alpha showed enhanced cytotoxicity and promoted the development of a memory-like phenotype in NK cells [138]. Similarly, another dual CAR-NK construct targeting PD-L1 and HER2 demonstrated superior therapeutic efficacy against multiple solid tumors, including breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and gastric cancer cell lines, while minimizing immune escape through antigen loss [7] (Table 1).

Lastly, combining PD-L1 CAR-NK cells with immune checkpoint inhibitors may further enhance anti-tumor activity, as reported in CAR-T studies involving engineered CARs to secrete anti-PD-1 scFvs [70], co-transduction with PD-1 short hairpin ribonucleic acid (RNA) [71], or adenine base editing to downregulate PD-1 expression [72]. All these approaches reduced exhaustion and improved the cytotoxic function of CAR-T cells, and similar strategies can be explored in CAR-NK therapies (Table 1).

9.3. Human Leukocyte Antigen-G (HLA-G)

HLA-G is a non-classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule that binds with immunoglobulin-like transcript 2 (ILT2) and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) DL4 on NK cells. This triggers an immunosuppressive microenvironment by encouraging the expansion of immunosuppressive cells, like regulatory T cells and MDSCs, and by diminishing NK cell functionality, resulting in immune evasion of tumor cells [73]. HLA-G targeting CAR-NK cells with a DAP12 intracellular signaling domain demonstrated significant cytotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo against several solid tumor models, including breast, brain, pancreatic, and ovarian cancer cells (Figure 1F) [74]. Co-culture of the anti-HLA-G CAR-NK cells with tumor cells led to the activation of the Syk/Zap70 signal transduction cascade of NK cells, thereby reversing the HLA-G-mediated immunosuppressive signals [74] (Table 1).

9.4. B7-H3 (CD276)

The overexpression of the B7 homologous 3 protein (B7-H3) immune checkpoint molecule in several cancers has been shown to suppress NK-mediated cell lysis [139]. Anti-B7-H3 CAR-NK-92 cells demonstrated significantly higher cytotoxic potential and elevated cytotoxic markers, including perforin, granzyme B, and CD107a, against tumor targets both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 1F) [75]. Similarly, Grote and colleagues [76] developed a second-generation B7-H3 CAR-NK-92 cell line, which showed high specificity by lysing neuroblastoma cells expressing high B7-H3 levels while sparing B7-H3-negative cell populations. The same study investigated the resilience of the engineered CAR-NK cells against the TME challenges, including low pH, hypoxia, and diverse immunosuppressive factors. The B7-H3 CAR-NK cells exhibited remarkable therapeutic potential by overcoming the TME-mediated immunosuppression and successfully lysing melanoma cells [76] (Table 1).

9.5. CD47/Signal Regulatory Protein Alpha (SIRPα)

CD47 is an inhibitory ligand overexpressed in multiple cancer cells. It binds with SIRPα on innate immune cells, which triggers “don’t-eat-me” signaling, ultimately leading to tumor immune evasion. This interaction suppresses macrophage phagocytosis [77] and NK cell cytotoxicity against tumor cells [78]. Additionally, elevated CD47 messenger RNA levels correlate with poor patient survival outcomes across multiple solid malignancies [77,79]. Therefore, various approaches have been investigated to disrupt this CD47/SIRPα axis, including blocking antibodies, recombinant SIRPα proteins, and strategic CAR designs. Anti-CD47 antibodies combined with CAR-NK cells demonstrated robust anti-tumor activity in gastrointestinal cancer models [80]. While limited studies are available on anti-CD47 CAR-NK cells, CAR-T cells targeting CD47 show great efficacy against ovarian [81], pancreatic [140], lung [141], and osteosarcoma models (Figure 1F). [82]. CAR immune cells have also been engineered to secrete soluble CD47/SIRPα-blocking agents, including chimeric monoclonal CD47 antibodies [142], SIRPα-Fc fusion proteins [83], and high-affinity CD47 blockers, like CV1 [80,143] and SIRPγ-derived protein (SGRP) [144]. Disrupting the CD47-SIRPα axis enables macrophage phagocytosis, induces phenotype switch from M2 to M1 TAMs [77,83,145], reduces CAR cell therapy resistance, and improves NK cell anti-tumor activity [78] (Table 1). Clinically, CD47 targeting is constrained by on-target, off-tumor toxicity since CD47 is expressed on normal cells, posing safety risks. For example Magrolimab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks CD47, causes anemia in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome [146].

10. Clinical Translation and Ongoing Trials

To highlight the strategies reviewed above, we compiled a table of current CAR-NK clinical trials in solid tumors, summarizing CAR constructs, targets, and phases (Table 2). These trials show first-in-human studies targeting TROP2, PD-1, PD-L1, NKG2D, and others as indicated, with several testing intraperitoneal delivery, hepatic artery transfusion, or combinations with checkpoint blockades and cytokine agonists. A phase II trial of irradiated PD-L1 CAR-NK plus pembrolizumab and N-803 in gastroesophageal and head and neck cancers (NCT04847466, Table 2) reflects emphasis on using CAR-NK cells with immune modulation. Additionally, TROP2 CAR-NK studies, including IL-15 transduced NK cells, aim to enhance persistence, and NKG2D CAR-NK cells may mitigate antigen heterogeneity by recognizing multiple stress ligands (Table 2). In solid tumors, both CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies remain largely confined to early phase I/II studies with modest response rates compared with hematological malignancies. Direct comparisons between CAR-T and CAR-NK in the same indications are not yet available, and cross-trial comparisons are complicated by differences in targets, constructs, and trial design. At present, the rationale for prioritizing CAR-NK engineering in solid tumors rests mainly on their favorable safety profile, off-the-shelf potential, and encouraging preclinical data in TME-relevant models rather than on proven clinical superiority over CAR-T cells [147].

11. Manufacturing Challenges and Limitations of CAR NK Therapy

Despite showing fewer severe toxicities than CAR-T cells due to their shorter lifespan, limited in vivo expansion, and lower cytokine secretion, CAR NK cells still possess some limitations. Off-target binding and on-target, off-tumor toxicity remain a major concern, as few tumor-associated antigens are exclusively expressed on malignant cells. Therefore, it is crucial to develop CAR constructs that can strictly discriminate between malignant and healthy cells. Emerging computation and AI-based antigen discovery tools may help design scFvs with greater tumor specificity while reducing off-target cytotoxicity. Additionally, to improve their persistence, CAR NK cells are often armored with cytokines, such as IL-15, which may lead to systemic toxicity, immune dysregulation, or uncontrolled proliferation [148]. The most common side effects reported after CAR NK transfusion include fever and fatigue, arising from the increase in IL-6 and C-reactive protein [1]. To address these concerns, inducible or logic-gated CAR NK cells (“on-switch” AND/OR-gated CARs) have been designed to control unintended activation or include safety switches, such as inducible caspase-9, that allow selective depletion of CAR-NK cells in cases of severe toxicity [149].

Although CAR NK therapy has shown promising results in preclinical and early clinical studies, clinical-scale manufacturing of CAR NK cells remains a significant barrier to widespread adoption, largely due to the lack of standardization. Various allogeneic sources have been used to generate CAR NK cells, including peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood, NK cell lines (such as NK-92), and iPSCs, each with distinct advantages and limitations previously reviewed in detail [150]. The diverse sources of NK cells, while advantageous, introduce production challenges as different sources exhibit highly varying transduction and expansion efficacy, persistence, and cytotoxic activity, leading to varying performances of the product. Furthermore, unlike other cells, the transduction and transfection efficiency is much lower in NK cells [151], therefore making it much more difficult to generate high levels of genetically modified NK cells. In addition, the batch variability in titer and purity often seen in clinical-grade lentiviral and retroviral vectors ultimately impacts the gene transduction efficiency [152]. Moreover, gene transduction via viral vectors may lead to insertional mutagenesis, which poses the risk of genome instability and secondary malignancies [153]. iPSC-derived NK cells address many of these limitations by providing a renewable, genetically defined, and clonally stable source. iPSCs can be precisely genetically engineered at the pluripotent stage using CRISPR-Cas9 and then cloned to generate uniform, fully functional NK cells with stable CAR expression, therefore eliminating the need to virally transduce mature NK cells. Moreover, these cloned, genetically edited iPSCs allow the generation of CAR-engineered master cell banks that can be expanded, differentiated into defined effector NK cells, cryopreserved, and distributed as standardized “off-the-shelf” products, greatly reducing production time, cost, and variability while ensuring improved persistence and cytotoxicity [154]. The lack of a standardized CAR design, along with significant variation in genetic engineering methods, vector systems, expression strategies, and NK cell sources across different research institutions, further adds to the challenges for clinical application. Therefore, further research determining which genetic engineering approaches and combinations work best for producing effective CAR-NK therapies is required. While advanced genetic engineering strategies, such as quadruple gene-engineered CAR NK cells, have shown durable anti-tumor activity in preclinical studies [155], each genetic modification further adds to the manufacturing complexity. Finally, generating consistent product quality under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions requires strict control of GMP-grade cytokines, serum-free media, and seed cell thawing protocols. Feeder-free expansion systems in bioreactors often fail to achieve yields comparable to feeder-based protocols while maintaining regulatory compliance [156]. Furthermore, cryopreservation impairs CAR NK cell activity [157]; therefore, research addressing this and post-thaw viability is crucial. For off-the-shelf use, it is essential to develop a standardized, scalable, and reproducible manufacturing pipeline ensuring the safety, efficacy, and accessibility of next-generation CAR-NK therapies.

12. Conclusions

Effective solid tumor control with CAR-NK therapy will require addressing TME barriers (summarized in Figure 1). This consists of broadening target recognition, preventing antigen loss, limiting fratricide, overcoming stromal barriers, hypoxia, and metabolic stress, enhancing homing, sustaining cell persistence, and blocking inhibitory checkpoints. Early clinical data support the feasibility of these strategies, including multi-antigen targeting, engineered cytokine support, and regional delivery of CAR-NK cells. The future of CAR NK therapy lies in addressing these limitations using innovative approaches and combination strategies. Artificial intelligence has been integrated into CAR therapy, where deep learning approaches enable multi-antigen targeting and antigen escape prevention, natural language processing facilitates clinical data extraction from reports and the literature, computer vision analyzes CAR cell morphology and phenotypes, reinforcement learning optimizes dosing schedules, and predictive algorithms assess therapeutic efficacy and toxicity profiles [158]. Although emerging artificial intelligence and machine learning tools may aid CAR-NK design in the future, their current use in solid tumors is still exploratory.

Prioritizing CAR-NK combinations should be driven by the main barrier in each tumor. In desmoplastic, stroma-rich cancers, pairing CAF/ECM targeting or anti-stroma approaches with multi-antigen targeting may best improve both access and specificity. In hypoxic TMEs, combinations that couple metabolic or mitochondrial support (for example, cytokine armoring or metabolic re-programming) with persistence tools and checkpoint modulation may provide impact, whereas in checkpoint or soluble factor-driven settings, multi-antigen targeting, checkpoint blockade, and cytokine support may provide better efficacy. Additionally, combination strategies such as administering immune checkpoint inhibitors, kinase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, STING agonists, oncolytic viruses, and photothermal therapy that can regulate or reshape the TME present opportunities to improve CAR NK homing, persistence, and cytotoxicity [159].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roland Shu for earlier scientific input and Graham Jenkin for valuable editorial assistance. Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors, except F.I., are paid employees of Cartherics Pty Ltd. and hold options and/or equity in the company. R.L.B and A.O.T are key Cartherics executives.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2B4 | CD244; SLAM family co-receptor on NK and T cells |

| 5T4 | oncofetal trophoblast glycoprotein |

| A2A | adenosine A2A receptor |

| ADAM | a disintegrin and metalloproteinase |

| AI-CAR | dual CAR (activating ROR1/CD19 CAR and CS1 inhibitory CAR) |

| AMPK | adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| AXL | AXL receptor tyrosine kinase |

| B7-H3 | B7 homolog 3 |

| BCL-2 | B cell lymphoma 2 |

| BCL-XL | B cell lymphoma-extra large |

| BiKE | bispecific killer engager |

| CAFs | cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CAR | chimeric antigen receptor |

| Cas9 | CRISPR-associated nuclease 9 |

| CCR | CC motif chemokine receptor |

| CD | cluster of differentiation |

| CIS | cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein |

| CISH | cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein gene |

| CRISPR | clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat |

| CXCR | CXC motif chemokine receptor |

| DAP10, 12 | adaptor proteins for activating NK receptors |

| DLL3 | delta-like ligand 3 |

| DNAM-1 | DNAX accessory molecule 1 |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| FAP | fibroblast activation protein |

| GD2 | disialoganglioside GD2 |

| GBM | glioblastoma |

| GPC3 | glypican-3 |

| haNK | high-affinity NK cell |

| HER2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HIFs | hypoxia-inducible factors |

| HLA-G | human leukocyte antigen-G |

| ICD | intracellular domain |

| IDO | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IFN | interferon |

| IL | interleukin |

| ILT2 | immunoglobulin-like transcript 2 |

| KIR | killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor |

| KO | knockout |

| LAG-3 | lymphocyte activation gene 3 |

| MDSCs | myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MICA/B | major histocompatibility complex class I-related protein A/B |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteinases |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| MUC1 | mucin-1 |

| NK | natural killer |

| NKp30, 44, 46 | natural cytotoxicity receptors |

| NKG2A | natural killer group 2 member A |

| NKG2D | natural killer group 2 member D |

| NSCLC | non-small cell lung cancer |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | programmed death ligand 1 |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| PSMA | prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| ROBO1 | roundabout homolog 1 |

| ROR1 | receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| scFvs | single-chain variable fragments |

| SIRPα/γ | signal regulatory protein-alpha/gamma |

| SLC1A5/SLC3A2/SLC7A5 | amino acid transporters |

| STING | stimulator of interferon genes |

| TAAs | tumor-associated antigens |

| TAMs | tumor-associated macrophages |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| TGFβR | TGF-β receptor |

| TIGIT | T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains |

| TIM-3 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing-3 |

| TM | transmembrane domain |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TriKEs | trispecific killer cell engagers |

| TROP2 | trophoblast cell surface antigen-2 |

References

- Balkhi, S.; Zuccolotto, G.; Di Spirito, A.; Rosato, A.; Mortara, L. CAR-NK cell therapy: Promise and challenges in solid tumors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1574742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Yang, H.; Xiong, H.; Luo, K.Q. NK cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1303605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalej, K.M.; Merhi, M.; Inchakalody, V.P.; Mestiri, S.; Alam, M.; Maccalli, C.; Cherif, H.; Uddin, S.; Steinhoff, M.; Marincola, F.M.; et al. CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: Current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.A.; Nilsson, M.B.; Yang, Y.; Le, X.; Tran, H.T.; Elamin, Y.Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, F.; Poteete, A.; Ren, X.; et al. IL6 Mediates Suppression of T- and NK-cell Function in EMT-associated TKI-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 1292–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Jin, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Chang, Y.; Xu, J. Immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages expressing interlukin-10 conferred poor prognosis and therapeutic vulnerability in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, K.; Geiger, A.; Dowlati, E.; Lang, H.; Sohai, D.K.; Hwang, E.I.; Lazarski, C.A.; Yvon, E.; Holdhoff, M.; Jones, R.; et al. Co-transducing B7H3 CAR-NK cells with the DNR preserves their cytolytic function against GBM in the presence of exogenous TGF-beta. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 27, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, C.; Hazime, K.S.; Zelenay, S.; Davis, D.M. Prostaglandin E2 impacts multiple stages of the natural killer cell antitumor immune response. Eur. J. Immunol. 2024, 54, e2350635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Dalai, P.; Agrawal-Rajput, R. Metabolic crosstalk: Extracellular ATP and the tumor microenvironment in cancer progression and therapy. Cell Signal 2024, 121, 111281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caforio, M.; Sorino, C.; Caruana, I.; Weber, G.; Camera, A.; Cifaldi, L.; De Angelis, B.; Del Bufalo, F.; Vitale, A.; Goffredo, B.M.; et al. GD2 redirected CAR T and activated NK-cell-mediated secretion of IFNgamma overcomes MYCN-dependent IDO1 inhibition, contributing to neuroblastoma cell immune escape. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Guo, L.; Xing, Z.; Shi, L.; Liang, H.; Li, A.; Kuang, C.; Tao, B.; Yang, Q. IDO1 can impair NK cells function against non-small cell lung cancer by downregulation of NKG2D Ligand via ADAM10. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 106132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F.R.; Quatrini, L.; Munari, E.; Vacca, P.; Moretta, L. Innate Lymphoid Cells: Expression of PD-1 and Other Checkpoints in Normal and Pathological Conditions. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, S.; Trabanelli, S.; Di Vito, C.; Greppi, M.; Obino, V.; Guolo, F.; Minetto, P.; Bozzo, M.; Calvi, M.; Zaghi, E.; et al. Cancer Immunotherapy by Blocking Immune Checkpoints on Innate Lymphocytes. Cancers 2020, 12, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagala, J.; Lachota, M.; Klopotowska, M.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; Domagala, A.; Zhylko, A.; Soroczynska, K.; Winiarska, M. The Tumor Microenvironment-A Metabolic Obstacle to NK Cells’ Activity. Cancers 2020, 12, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Sharabi, A. Targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cells to enhance natural killer cell-based immunotherapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 235, 108114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaiu, O.; Lucarini, V.; Cifaldi, L.; Fruci, D. Influence of the Tumor Microenvironment on NK Cell Function in Solid Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castriconi, R.; Dondero, A.; Bellora, F.; Moretta, L.; Castellano, A.; Locatelli, F.; Corrias, M.V.; Moretta, A.; Bottino, C. Neuroblastoma-derived TGF-beta1 modulates the chemokine receptor repertoire of human resting NK cells. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 5321–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, P.S.; Chen, D.S. Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity 2020, 52, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Fu, W.; Li, T.; Zhao, J.; Lei, C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S. CAR-T-cell products in solid tumors: Progress, challenges, and strategies. Interdiscip. Med. 2024, 2, e20230047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywa, T.; Mehta, N.; Cossette, B.; Romanov, A.; Paruzzo, L.; Ramasubramanian, R.; Cozzone, A.; Morgan, D.; Sukaj, I.; Bergaggio, E.; et al. Directed evolution-based discovery of ligands for in vivo restimulation of CAR-T cells. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martarelli, N.; Capurro, M.; Mansour, G.; Jahromi, R.V.; Stella, A.; Rossi, R.; Longetti, E.; Bigerna, B.; Gentili, M.; Rosseto, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Powered Molecular Docking and Steered Molecular Dynamics for Accurate scFv Selection of Anti-CD30 Chimeric Antigen Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, P.S.; Premkumar, T.; Sundararajan, V.; Hussain, M.S.; Arumugam, S. Design and development of dual targeting CAR protein for the development of CAR T-cell therapy against KRAS mutated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma using computational approaches. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, R.K.A.; Studart, I.C.; Bezerra, M.R.L.; Pontes, L.Q.; Barbosa, A.M.A.; Brigido, M.M.; Furtado, G.P.; Maranhao, A.Q. Progress on Phage Display Technology: Tailoring Antibodies for Cancer Immunotherapy. Viruses 2023, 15, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kim, D.; Kang, S.; Jung, J.U. A Detailed Protocol for Constructing a Human Single-Chain Variable Fragment (scFv) Library and Downstream Screening via Phage Display. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitler, J.; Freudenberg, K.; Montero, P.O.; Rackwitz, W.; Wels, W.; Tonn, T. 216 Dual targeting of CAR-NK cells to PD-L1 and ErbB2 facilitates specific elimination of cancer cells of solid tumor origin and overcomes immune escape by antigen loss. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, A230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, Y.E.; Frolova, E.I.; Chumakov, S.P. Dual CAR-Targeted Natural Killer Cell Lines Demonstrate Potent Cytotoxic Properties Towards Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Appl. Exerc. Physiol. 2020, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Toregrosa-Allen, S.; Elzey, B.D.; Utturkar, S.; Lanman, N.A.; Bernal-Crespo, V.; Behymer, M.M.; Knipp, G.T.; Yun, Y.; Veronesi, M.C.; et al. Multispecific targeting of glioblastoma with tumor microenvironment-responsive multifunctional engineered NK cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2107507118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genβler, S.; Burger, M.C.; Zhang, C.; Oelsner, S.; Mildenberger, I.; Wagner, M.; Steinbach, J.P.; Wels, W.S. Dual targeting of glioblastoma with chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer cells overcomes heterogeneity of target antigen expression and enhances antitumor activity and survival. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1119354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, T.; Guan, B.; Li, H.; Tu, X.; Zhang, C.; Tang, B. Principles and current clinical landscape of NK cell engaging bispecific antibody against cancer. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2256904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Roder, J.; Scherer, A.; Bodden, M.; Pfeifer Serrahima, J.; Bhatti, A.; Waldmann, A.; Muller, N.; Oberoi, P.; Wels, W.S. Bispecific antibody-mediated redirection of NKG2D-CAR natural killer cells facilitates dual targeting and enhances antitumor activity. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, A.; Prufer, M.; Roder, J.; Pfeifer Serrahima, J.; Bodden, M.; Kuhnel, I.; Oberoi, P.; Wels, W.S. Dual Targeting of Glioblastoma Cells with Bispecific Killer Cell Engagers Directed to EGFR and ErbB2 (HER2) Facilitates Effective Elimination by NKG2D-CAR-Engineered NK Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, E.; Lee, E.; Park, H.J.; Lee, H.H.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.S. A chimeric antigen receptor tailored to integrate complementary activation signals potentiates the antitumor activity of NK cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, K.E.; Fricke, S.; Kohl, U.; Schmiedel, D. Taking Lessons from CAR-T Cells and Going Beyond: Tailoring Design and Signaling for CAR-NK Cells in Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 822298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoutrop, E.; Renken, S.; Micallef Nilsson, I.; Hahn, P.; Poiret, T.; Kiessling, R.; Wickstrom, S.L.; Mattsson, J.; Magalhaes, I. Trogocytosis and fratricide killing impede MSLN-directed CAR T cell functionality. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2093426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Basar, R.; Wang, G.; Liu, E.; Moyes, J.S.; Li, L.; Kerbauy, L.N.; Uprety, N.; Fathi, M.; Rezvan, A.; et al. KIR-based inhibitory CARs overcome CAR-NK cell trogocytosis-mediated fratricide and tumor escape. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2133–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudrisier, D.; Aucher, A.; Puaux, A.L.; Bordier, C.; Joly, E. Capture of target cell membrane components via trogocytosis is triggered by a selected set of surface molecules on T or B cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 3637–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.S.; Boulifa, A.; Radecke, C.; Stintzing, S.; Raftery, M.J.; Pecher, G. Next-Generation CEA-CAR-NK-92 Cells against Solid Tumors: Overcoming Tumor Microenvironment Challenges in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.E.; Go, G.Y.; Koh, E.Y.; Yoon, H.N.; Seo, M.; Hong, S.M.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, J.C.; Cho, D.; Kim, T.S.; et al. Synergistic therapeutic combination with a CAF inhibitor enhances CAR-NK-mediated cytotoxicity via reduction of CAF-released IL-6. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, I.; Savoldo, B.; Hoyos, V.; Weber, G.; Liu, H.; Kim, E.S.; Ittmann, M.M.; Marchetti, D.; Dotti, G. Heparanase promotes tumor infiltration and antitumor activity of CAR-redirected T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Xi, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Yue, S.Y.; Shi, L.; Rong, Y. Co-expression of IL-7 and PH20 promote anti-GPC3 CAR-T tumour suppressor activity in vivo and in vitro. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, S.; Lv, J.; Wu, Q.; Long, Y.; Wang, S.; Yao, Y.; Wei, W.; et al. Human Hyaluronidase PH20 Potentiates the Antitumor Activities of Mesothelin-Specific CAR-T Cells Against Gastric Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 660488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, H.; Xing, L. Synergistic treatment strategy: Combining CAR-NK cell therapy and radiotherapy to combat solid tumors. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1298683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolor, A.; Szoka, F.C., Jr. Digesting a Path Forward: The Utility of Collagenase Tumor Treatment for Improved Drug Delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Guo, M.; Luo, J. CAR-armored-cell therapy in solid tumor treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.H.; Yoon, H.N.; Kang, H.J.; Yoo, H.; Choi, M.J.; Chung, J.Y.; Seo, M.; Kim, M.; Lim, S.O.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. Empowering pancreatic tumor homing with augmented anti-tumor potency of CXCR2-tethered CAR-NK cells. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2024, 32, 200777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.Y.; Tay, J.C.K.; Wang, S. CXCR1 Expression to Improve Anti-Cancer Efficacy of Intravenously Injected CAR-NK Cells in Mice with Peritoneal Xenografts. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2020, 16, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, N.; Michen, S.; Tietze, S.; Topfer, K.; Schulte, A.; Lamszus, K.; Schmitz, M.; Schackert, G.; Pastan, I.; Temme, A. Engineering NK Cells Modified with an EGFRvIII-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor to Overexpress CXCR4 Improves Immunotherapy of CXCL12/SDF-1alpha-secreting Glioblastoma. J. Immunother. 2015, 38, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Sheng, Y.; Hou, W.; Sampath, P.; Byrd, D.; Thorne, S.; Zhang, Y. CCL5-armed oncolytic virus augments CCR5-engineered NK cell infiltration and antitumor efficiency. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Huang, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, D.; Gao, L.; Ge, Z.; Su, M.; et al. Overexpressed CXCR4 and CCR7 on the surface of NK92 cell have improved migration and anti-tumor activity in human colon tumor model. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2020, 31, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, S.; Conlon, K.C.; Muller, J.R.; Hsu-Albert, J.; Beltran, N.; Bryant, B.R.; Waldmann, T.A. IL15 Infusion of Cancer Patients Expands the Subpopulation of Cytotoxic CD56(bright) NK Cells and Increases NK-Cell Cytokine Release Capabilities. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polentarutti, N.; Allavena, P.; Bianchi, G.; Giardina, G.; Basile, A.; Sozzani, S.; Mantovani, A.; Introna, M. IL-2-regulated expression of the monocyte chemotactic protein-1 receptor (CCR2) in human NK cells: Characterization of a predominant 3.4-kilobase transcript containing CCR2B and CCR2A sequences. J. Immunol. 1997, 158, 2689–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailliard, R.B.; Alber, S.M.; Shen, H.; Watkins, S.C.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Herberman, R.B.; Kalinski, P. IL-18-induced CD83+CCR7+ NK helper cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, Z.; Chiocca, E.A.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Yu, J. The emerging field of oncolytic virus-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, W.K.; Lee, B.C.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.J.; Chung, I.J.; Cho, S.B.; Koh, Y.S. A Phase I Study of Locoregional High-Dose Autologous Natural Killer Cell Therapy with Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 879452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Cen, D.; Gan, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, N.; Xiong, H.; Jin, Q.; Su, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; et al. Adoptive Transfer of NKG2D CAR mRNA-Engineered Natural Killer Cells in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, B.; Deng, M.; Wang, W.; Mi, X.; et al. Breakthrough of solid tumor treatment: CAR-NK immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces-Lazaro, I.; Kotzur, R.; Cerwenka, A.; Mandelboim, O. NK Cells Under Hypoxia: The Two Faces of Vascularization in Tumor and Pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 924775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, R.; Wang, Y.; Lv, N.; Zhang, D.; Williamson, R.A.; Lei, L.; Chen, P.; Lei, L.; Wang, B.; Fu, J.; et al. Hypoxia Impairs NK Cell Cytotoxicity through SHP-1-Mediated Attenuation of STAT3 and ERK Signaling Pathways. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 4598476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, Z.; Huang, Y.; Seth, P.; Sukhatme, V.P. Tumor-derived lactate modifies antitumor immune response: Effect on myeloid-derived suppressor cells and NK cells. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, T.J.; Biederstadt, A.; Rezvani, K. Natural killer cells in antitumour adoptive cell immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wang, X.; Stojanovic, A.; Zhang, Q.; Wincher, M.; Bühler, L.; Arnold, A.; Correia, M.P.; Winkler, M.; Koch, P.-S.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Tumor-Infiltrating NK Cells Reveals that Inhibition of Transcription Factor HIF-1α Unleashes NK Cell Activity. Immunity 2020, 52, 1075–1087.e1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinsky, N.; Williams, K.; Watkins, D.; Adams, M.; Stanbery, L.; Nemunaitis, J. Regulatory role of CD39 and CD73 in tumor immunity. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lupo, K.B.; Chambers, A.M.; Matosevic, S. Purinergic targeting enhances immunotherapy of CD73+ solid tumors with piggyBac-engineered chimeric antigen receptor natural killer cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.M.; Lupo, K.B.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.; Utturkar, S.; Lanman, N.; Bernal-Crespo, V.; Jalal, S.; Pine, S.R.; Torregrosa-Allen, S.; et al. Engineered natural killer cells impede the immunometabolic CD73-adenosine axis in solid tumors. Elife 2022, 11, e73699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, L.; Sek, K.; Henderson, M.A.; Lai, J.; Chen, A.X.Y.; Meyran, D.; Todd, K.L.; Petley, E.V.; Mardiana, S.; Molck, C.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of the adenosine A2A receptor enhances CAR T cell efficacy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaiatz-Bittencourt, V.; Finlay, D.K.; Gardiner, C.M. Canonical TGF-beta Signaling Pathway Represses Human NK Cell Metabolism. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 3934–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.D.; Lee, S.U.; Yun, S.; Sun, H.N.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, H.M.; Park, S.K.; Lee, C.W.; Yoon, S.R.; et al. Human microRNA-27a* targets Prf1 and GzmB expression to regulate NK-cell cytotoxicity. Blood 2011, 118, 5476–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraj, J.L.; Coffey, M.; Lopez, E.; Kaufman, D.S. Disruption of TGF-b; signaling pathway is required to mediate effective killing of hepatocellular carcinoma by human iPSC-derived NK cells. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 1327–1343.e1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaim, H.; Shanley, M.; Basar, R.; Daher, M.; Gumin, J.; Zamler, D.B.; Uprety, N.; Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; Gabrusiewicz, K.; et al. Targeting the alphav integrin/TGF-beta axis improves natural killer cell function against glioblastoma stem cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e142116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, K.; Woods, E.; Zaiatz-Bittencourt, V.; Marks, S.; Chew, S.; Conroy, M.; Goggin, C.; MacEochagain, C.; Kennedy, J.; Lucas, S.; et al. TGFbeta drives NK cell metabolic dysfunction in human metastatic breast cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Tian, J.; Hao, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, L. Engineered CAR-NK Cells with Tolerance to H2O2 and Hypoxia Can Suppress Postoperative Relapse of Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2024, 12, 1574–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.R.; Arvindam, U.S.; Phung, S.K.; Ettestad, B.; Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Kile, Q.M.; Hinderlie, P.; Khaw, M.; Huang, R.S.; et al. Metabolic programs drive function of therapeutic NK cells in hypoxic tumor environments. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, A.; Gehrcken, L.; Verhezen, T.; Lau, H.W.; Hermans, C.; Lambrechts, H.; Flieswasser, T.; Quatannens, D.; Roex, G.; Zwaenepoel, K.; et al. IL-15-secreting CAR natural killer cells directed toward the pan-cancer target CD70 eliminate both cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Blum, R.H.; Bernareggi, D.; Ask, E.H.; Wu, Z.; Hoel, H.J.; Meng, Z.; Wu, C.; Guan, K.L.; Malmberg, K.J.; et al. Metabolic Reprograming via Deletion of CISH in Human iPSC-Derived NK Cells Promotes In Vivo Persistence and Enhances Anti-tumor Activity. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 224–237.e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, R.; Ryan, J.; Pan, D.; Wucherpfennig, K.W.; Letai, A. Augmenting NK cell-based immunotherapy by targeting mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell 2022, 185, 1521–1538.e1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachef, M.; Ali, A.K.; Almutairi, S.M.; Lee, S.-H. Targeting SLC1A5 and SLC3A2/SLC7A5 as a Potential Strategy to Strengthen Anti-Tumor Immunity in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 624324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhi, L.; Lv, T.; Li, M.; Lu, C.; Zhu, W. Structure-based rational design of a novel chimeric PD1-NKG2D receptor for natural killer cells. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 114, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Guo, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhi, L.; Lv, T.; Li, M.; Niu, Z.; Lu, P.; Zhu, W. A novel chimeric PD1-NKG2D-41BB receptor enhances antitumor activity of NK92 cells against human lung cancer H1299 cells by triggering pyroptosis. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 122, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhi, L.; Yin, M.; Guo, C.; Zhang, H.; Lu, C.; Zhu, W. A novel bispecific chimeric PD1-DAP10/NKG2D receptor augments NK92-cell therapy efficacy for human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cell. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 523, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.L.; He, Y.Q.; Xiao, B.; Si, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, X.A.; Tian, L.; Ren, Q.; Wu, Y.S.; Zhu, Y. A Novel Sushi-IL15-PD1 CAR-NK92 Cell Line with Enhanced and PD-L1 Targeted Cytotoxicity Against Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 726985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, E.J.; Hunzeker, J.T.; Kluesner, M.G.; Lahr, W.S.; Smeester, B.A.; Crosby, M.R.; Lonetree, C.L.; Yamamoto, K.; Bendzick, L.; Miller, J.S.; et al. A Genetically Engineered Primary Human Natural Killer Cell Platform for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, K.P.; Padget, M.R.; Donahue, R.N.; Solocinski, K.; Robbins, Y.; Allen, C.T.; Lee, J.H.; Rabizadeh, S.; Soon-Shiong, P.; Schlom, J.; et al. PD-L1 targeting high-affinity NK (t-haNK) cells induce direct antitumor effects and target suppressive MDSC populations. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Robbins, Y.; Sievers, C.; Friedman, J.; Abdul Sater, H.; Clavijo, P.E.; Judd, N.; Tsong, E.; Silvin, C.; Soon-Shiong, P.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor engineered NK cellular immunotherapy overcomes the selection of T-cell escape variant cancer cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah-Samani, M.; Ramezani, A.; Sheikhi, A.; Mostafavi-Pour, Z.; Erfani, N. Anti-PD-L1 chimeric antigen receptor natural killer cell: Characterization and functional analysis. APMIS 2024, 132, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajor, M.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; Marhelava, K.; Burdzinska, A.; Muchowicz, A.; Goral, A.; Zhylko, A.; Soroczynska, K.; Retecki, K.; Krawczyk, M.; et al. PD-L1 CAR effector cells induce self-amplifying cytotoxic effects against target cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e002500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Siriwon, N.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Jin, T.; He, F.; Kim, Y.J.; Mac, J.; Lu, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy by Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells Engineered to Secrete Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 6982–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, L.; Morello, A.; Villena-Vargas, J.; Feng, Y.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Jones, D.R.; Sadelain, M.; Adusumilli, P.S. Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3130–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xuan, Y.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, Y. Targeting glycosylation of PD-1 to enhance CAR-T cell cytotoxicity. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carosella, E.D.; Rouas-Freiss, N.; Tronik-Le Roux, D.; Moreau, P.; LeMaoult, J. HLA-G: An Immune Checkpoint Molecule. Adv. Immunol. 2015, 127, 33–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, C.I.; Huang, S.W.; Canoll, P.; Bruce, J.N.; Lin, Y.C.; Pan, C.M.; Lu, H.M.; Chiu, S.C.; Cho, D.Y. Targeting human leukocyte antigen G with chimeric antigen receptors of natural killer cells convert immunosuppression to ablate solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cao, B.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Kwok, H.F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Q. Targeting B7-H3 Immune Checkpoint with Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered Natural Killer Cells Exhibits Potent Cytotoxicity Against Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grote, S.; Chan, K.C.-H.; Baden, C.; Bösmüller, H.; Sulyok, M.; Frauenfeld, L.; Ebinger, M.; Handgretinger, R.; Schleicher, S. CD276 as a novel CAR NK-92 therapeutic target for neuroblastoma. Adv. Cell Gene Ther. 2021, 4, e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willingham, S.B.; Volkmer, J.-P.; Gentles, A.J.; Sahoo, D.; Dalerba, P.; Mitra, S.S.; Wang, J.; Contreras-Trujillo, H.; Martin, R.; Cohen, J.D.; et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6662–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuse, T.; Hu, X.; Agbor-Enoh, S.; Jang, M.K.; Alawi, M.; Saygi, C.; Gravina, A.; Tediashvili, G.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. The SIRPalpha-CD47 immune checkpoint in NK cells. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20200839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Soliman, A.; Joehlin-Price, A.; Abdul-Karim, F.; Rose, P.G.; Mahdi, H. Immune cells and signatures characterize tumor microenvironment and predict outcome in ovarian and endometrial cancers. Immunotherapy 2021, 13, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Ding, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Shi, G.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; et al. CDH17-targeting CAR-NK cells synergize with CD47 blockade for potent suppression of gastrointestinal cancers. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2559–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, R.; Evtimov, V.J.; Hammett, M.V.; Nguyen, N.N.; Zhuang, J.; Hudson, P.J.; Howard, M.C.; Pupovac, A.; Trounson, A.O.; Boyd, R.L. Engineered CAR-T cells targeting TAG-72 and CD47 in ovarian cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2021, 20, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, A.N.; Chockley, P.; Pruett-Miller, S.M.; Nguyen, P.; Vogel, P.; Sheppard, H.; Krenciute, G.; Gottschalk, S.; DeRenzo, C. CD47 expression is critical for CAR T-cell survival in vivo. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yu, B.; Huang, Z. Delivery of CD47 blocker SIRPalpha-Fc by CAR-T cells enhances antitumor efficacy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettadapur, A.; Miller Hannah, W.; Ralston Katherine, S. Biting Off What Can Be Chewed: Trogocytosis in Health, Infection, and Disease. Infect. Immun. 2020, 88, e00930-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Du, Y.; Li, G.; Yu, M.; Hu, H.; Pan, C.; Wang, D.; Shi, Z.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; et al. Trogocytosis of CAR molecule regulates CAR-T cell dysfunction and tumor antigen escape. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, E.; Nandigama, R.; Ergun, S. Extracellular Matrix in the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Impact on Cancer Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gascard, P.; Tlsty, T.D. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts: Orchestrating the composition of malignancy. Genes. Dev. 2016, 30, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhao, H.L.; Huang, X.; Fang, Y.N.; Chen, W.Y.; Han, R.Z.; Zhao, A.; Gao, J.M. Development of FAP-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor NK-92 Cells for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Discov. Med. 2023, 35, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polten, R.; Kutle, I.; Stalp, J.L.; Hachenberg, J.; Seyda, A.K.; Neubert, L.; Kamp, J.C.; von Kaisenberg, C.; Schaudien, D.; Hillemanns, P.; et al. Anti-FAP CAR-NK cells as a novel targeted therapy against cervical cancer and cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncoimmunology 2025, 14, 2556714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsten, M.; Levy, E.; Karambelkar, A.; Li, L.; Reger, R.; Berg, M.; Peshwa, M.V.; Childs, R.W. Efficient mRNA-Based Genetic Engineering of Human NK Cells with High-Affinity CD16 and CCR7 Augments Rituximab-Induced ADCC against Lymphoma and Targets NK Cell Migration toward the Lymph Node-Associated Chemokine CCL19. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennerberg, E.; Kremer, V.; Childs, R.; Lundqvist, A. CXCL10-induced migration of adoptively transferred human natural killer cells toward solid tumors causes regression of tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2015, 64, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaki, A.; Argyropoulos, K.V.; Baxevanis, C.N.; Papamichail, M.; Perez, S.A. Effect of the simultaneous administration of glucocorticoids and IL-15 on human NK cell phenotype, proliferation and function. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2011, 60, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somanchi, S.S.; Somanchi, A.; Cooper, L.J.; Lee, D.A. Engineering lymph node homing of ex vivo-expanded human natural killer cells via trogocytosis of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Blood 2012, 119, 5164–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.G.; Goy, H.E.; Rose, A.J.; McLellan, A.D. Controlling Cell Trafficking: Addressing Failures in CAR T and NK Cell Therapy of Solid Tumours. Cancers 2022, 14, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y. Hypoxic tumor microenvironment: Destroyer of natural killer cell function. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 36, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, B.P.; Nguyen, P.L.; Lee, K.; Cho, J. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1: A Novel Therapeutic Target for the Management of Cancer, Drug Resistance, and Cancer-Related Pain. Cancers 2022, 14, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qannita, R.A.; Alalami, A.I.; Harb, A.A.; Aleidi, S.M.; Taneera, J.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; El-Huneidi, W.; Saleh, M.A.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Semreen, M.H.; et al. Targeting Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) in Cancer: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Pathway Regulation. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Liao, Q.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, C.; Feng, M.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ding, X.; Yuan, M.; et al. Conditioned CAR-T cells by hypoxia-inducible transcription amplification (HiTA) system significantly enhances systemic safety and retains antitumor efficacy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Shan, J.; Hong, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Ma, J.; Shen, J.; et al. Hypoxia-Responsive CAR-T Cells Exhibit Reduced Exhaustion and Enhanced Efficacy in Solid Tumors. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juillerat, A.; Marechal, A.; Filhol, J.M.; Valogne, Y.; Valton, J.; Duclert, A.; Duchateau, P.; Poirot, L. An oxygen sensitive self-decision making engineered CAR T-cell. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosti, P.; Opzoomer, J.W.; Larios-Martinez, K.I.; Henley-Smith, R.; Scudamore, C.L.; Okesola, M.; Taher, M.Y.M.; Davies, D.M.; Muliaditan, T.; Larcombe-Young, D.; et al. Hypoxia-sensing CAR T cells provide safety and efficacy in treating solid tumors. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthana, C.K.; Rayginia, T.P.; Shifana, S.C.; Anto, N.P.; Kalimuthu, K.; Isakov, N.; Anto, R.J. The role of AMPK in cancer metabolism and its impact on the immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parihar, R.; Rivas, C.; Huynh, M.; Omer, B.; Lapteva, N.; Metelitsa, L.S.; Gottschalk, S.M.; Rooney, C.M. NK Cells Expressing a Chimeric Activating Receptor Eliminate MDSCs and Rescue Impaired CAR-T Cell Activity against Solid Tumors. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, S.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wen, C.; Hu, S.; An, G.; Meng, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Effects of CSF1R-targeted chimeric antigen receptor-modified NK92MI & T cells on tumor-associated macrophages. Immunotherapy 2018, 10, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Ngiow, S.F.; Barkauskas, D.S.; Sult, E.; Hay, C.; Blake, S.J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Takeda, K.; Teng, M.W.L.; et al. Co-inhibition of CD73 and A2AR Adenosine Signaling Improves Anti-tumor Immune Responses. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.; Ngiow, S.F.; Gao, Y.; Patch, A.M.; Barkauskas, D.S.; Messaoudene, M.; Lin, G.; Coudert, J.D.; Stannard, K.A.; Zitvogel, L.; et al. A2AR Adenosine Signaling Suppresses Natural Killer Cell Maturation in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvon, E.S.; Burga, R.; Powell, A.; Cruz, C.R.; Fernandes, R.; Barese, C.; Nguyen, T.; Abdel-Baki, M.S.; Bollard, C.M. Cord blood natural killer cells expressing a dominant negative TGF-beta receptor: Implications for adoptive immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Germeraad, W.T.V.; Rouschop, K.M.A.; Steeghs, E.M.P.; Gelder, M.v.; Bos, G.M.J.; Wieten, L. Hypoxia Induced Impairment of NK Cell Cytotoxicity against Multiple Myeloma Can Be Overcome by IL-2 Activation of the NK Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, M.; Manzini, C.; Pietra, G.; Raggi, F.; Blengio, F.; Mingari, M.C.; Varesio, L.; Moretta, L.; Bosco, M.C.; Vitale, M. Hypoxia downregulates the expression of activating receptors involved in NK-cell-mediated target cell killing without affecting ADCC. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 2756–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]