Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Telomere parameters, such as telomere number, intensity, aggregates, and spatial organization, were identified as prognostic biomarkers in multiple myeloma (MM).

- Changes in the three-dimensional telomeric organization may predict risk of relapse in newly diagnosed MM and risk of progression in smoldering MM, with similar profiles in bone marrow and peripheral blood cells.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- 3D telomere profiling may enable minimally invasive monitoring of MM status and measurable residual disease using liquid biopsies.

- This approach potentially addresses an unmet clinical need by improving risk stratification and guiding personalized treatment strategies in multiple myeloma.

Abstract

A crucial role of genome instability and telomeric dysfunction was demonstrated in multiple cancers, including multiple myeloma (MM). MM accounts for approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies and includes asymptomatic pre-malignant monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). Due to the highly heterogeneous nature of the disease, there is an ongoing need for precise risk stratification and subsequent development of risk-adapted treatment strategies at every stage of disease and during disease progression. Telomere numbers, intensity, aggregates, and spatial arrangement within the nucleus were identified as prognostic biomarkers. Recent studies demonstrated that the three-dimensional (3D) analysis of key telomeric parameters is a reliable marker of the high risk of relapse in newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) patients and can predict the risk of progression of SMM patients. Telomeric parameters of malignant MM cells from the peripheral blood and bone marrow were similar, suggesting that 3D telomere profiling may assess MRD in liquid biopsies of MM patients. This review focuses on the prognostic value of 3D telomere profiling in MM. 3D spatial telomere analysis may potentially address a critical unmet clinical need in managing MM and, if incorporated into current guidelines, help to accurately predict disease status, progression risk, overall survival, and response to treatment.

1. Introduction

Telomere dysfunction is considered one of the critical genome alterations contributing to genomic instability, which is a hallmark of cancer [,]. Tumor cells display an altered telomere organization that manifests in telomeric aggregates, breakage-fusion-bridge cycles, changes in gene expression, and genome destabilization [,]. A crucial role of genome instability and telomeric dysfunction was demonstrated in solid tumors, as well as in multiple hematological malignancies, including multiple myeloma (MM), which accounts for approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies, with more than 35,000 new cases and 13,000 deaths reported in the United States alone each year []. This clonal plasma cell proliferative disorder is characterized by the abnormal increase of monoclonal immunoglobulins, leading over time to end-organ damage, such as renal dysfunction, hypercalcemia, anemia, and bone pain, accompanied by lytic lesions [,,]. MM is considered an advanced stage of a whole range of monoclonal gammopathies, which progress from asymptomatic monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) to smoldering MM (SMM), and finally, to fully symptomatic MM [].

An asymptomatic precursor stage of MM, MGUS, is present in approximately 5% of the population over the age of 50 []. MGUS is diagnosed based on the presence of a serum monoclonal protein (M protein) at a concentration < 3 g/dL, a bone marrow with <10 percent monoclonal plasma cells, absence of end-organ damage, such as lytic bone lesions, anemia, hypercalcemia, etc., and lack of B-cell lymphoma or other M-protein-producing disease []. As MGUS is clinically silent, many patients may have the condition for over a decade before detection, and treatment for MGUS is currently not recommended. However, in around 1% of MGUS patients, the disease progresses to the intermediate stage, SMM, which represents a more advanced but still asymptomatic form of MM []. Compared with MGUS, SMM is characterized by higher serum monoclonal protein concentrations (≥3 g/dL) in the absence of end-organ damage []. SMM is considered a heterogeneous disease with high variability in the risk of progression to symptomatic MM []. High-risk SMM carries ~50% risk of progressing to MM at 2 years from SMM diagnosis [].

While MM is considered an incurable disease, with the average overall survival (OS) of high-risk patients of only 3–5 years, current advances in therapeutic approaches, such as quadruplet induction and immune-based therapies, have increased the median OS of low-risk MM patients to over 10 years [,]. However, despite novel therapies, even patients who achieve complete remission (CR) often have measurable minimal residual disease (MRD), a small population of residual malignant plasma cells []. This further underscores the ongoing need for precise risk stratification and subsequent development of risk-adapted treatment strategies throughout the entire spectrum of monoclonal gammopathies.

Complexity and heterogeneity are hallmarks of the MM. Over 50 identified mutated genes are significantly associated with the disease, encoding proteins involved in signaling pathways, DNA repair, transcription, cell cycle regulation, plasma cell differentiation, and cellular adhesion, among other processes []. Furthermore, the mutational landscape of MM changes with the progression of the disease, and after therapy [,]. Early stages of MM involve significant karyotypic changes in the malignant plasma cells, such as chromosomal gains or losses, translocations, and rearrangements, including translocations in the telomeric IGH locus (14q32.33) []. Telomere numbers, intensity, aggregates, and the three-dimensional arrangement of telomeres within the nucleus were identified as prognostic biomarkers in several cancers, including MM [,,]. Recently, telomere-based analysis of the three-dimensional (3D) nuclear architecture of myeloma cells has gained increasing attention. Spatial telomere profiling using TeloView, a software specifically designed to quantify key 3D telomeric parameters on a single-cell level [] has emerged as a valuable prognostic tool in MM, as it addresses a critical unmet clinical need in managing MM and can accurately predict the disease status and progression risk, overall survival, and response to treatment []. Furthermore, telomere profiling of cells in liquid biopsies [] was shown to be a promising and effective method for risk-stratification and the prospective long-term monitoring of disease stability in MM patients who underwent therapy and/or bone marrow transplantation. This review will discuss telomere dysfunction, genomic instability, and their relevance in MM, with future impact on the clinic.

2. Telomeres and Genomic Instability

Studies of higher-order chromatin arrangements and their dynamic interactions demonstrated that chromosomes are compartmentalized into discrete territories, and such compartmentalization directly impacts the access of genes to the transcription and splicing factors [,]. The influence of three-dimensional (3D) nuclear chromosomal organization on gene expression and genome stability became a focus of substantial research, especially in the context of cancer. In the early stages of carcinogenesis, changes in chromosomal stability, DNA folding, and transcription are considered the main triggers of the malignant transformation []. Indeed, extensive chromosome rearrangements and overall genomic instability are regarded as hallmarks of cancer [,,,,,,]. While these rearrangements may stem from several possible mechanisms [], numerous studies have clearly demonstrated the crucial role of telomere dysfunction in promoting genomic instability in malignancies [,,,,].

Telomeres cap the ends of the chromosomes, preventing end-to-end fusions, averting inappropriate DNA damage response, and protecting chromosomal ends from degradation []. Telomeres are composed of long tracts of double-stranded TTAGGG repeats with a single-stranded G-tail, protruding in the 3′ direction [], and organized into a loop-like structure (T-Loop) that protects the telomere from the DNA damage response machinery []. This protection is enabled by the proteins of the shelterin complex, consisting of Telomeric Repeat binding Factors TRF1 and TRF2, the Repressor/Activator Protein 1 (RAP1), the bridging molecules TPP1 and TRF1 Interacting protein (TIN2), and the Protector of Telomeres 1 (POT1) []. The shelterin complex plays a crucial role in regulating telomere length and telomere protection, and acts as an anchoring factor for enzymes and effector proteins of various signaling cascades []. While somatic cells lack telomere length maintenance mechanisms, resulting in progressive shortening of the telomeric sequence with each cell cycle, in stem and germ cells, as well as in some cancer cells, telomere attrition is reversed by adding telomeric repeats de novo by the telomerase enzyme complex []. Indeed, telomere length changes have long been recognized as a critical mechanism in cancer pathogenesis, with a complex correlation between telomere length and the risk of various cancers [,,,,,]. Critical shortening of the telomeres (often transient) at the early stages of transformation has been shown to lead to a telomere crisis, a state of extensive genomic instability [,]. Loss of telomeric protection was shown to lead to McClintock’s breakage-fusion-bridge cycles, chromosomal abnormalities, and aneuploidy []. The resulting accumulation of mutations, in turn, triggers an increase in telomerase expression, which is necessary for continued cell proliferation and transition to malignancy []. Reactivation of the telomerase is observed in over 80% of all cancers [], allowing the cell to avoid DNA damage signaling pathways []. Indeed, studies showed that activation of telomerase in cells that entered breakage-fusion cycles and have lost tumor suppressive pathways such as p53 and pRb, results in stabilization of telomeres and immortality, and, accompanied by genome instability, is a driving force of tumorigenesis [,,,].

The remaining cancers use the alternative telomere lengthening pathway (ALT) [,]. With the development of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), a tool for visualizing genomes, ranging from the level of chromosome territories to the level of specific chromatin structures [,] it became apparent that telomere length is not the only marker of genomic instability during tumorigenesis. The quantification of digital FISH images (quantitative FISH or QFISH) using a fluorescent peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe confirmed, for the first time, that telomere intensity correlates with telomere length []. QFISH enabled molecular cytogenetic analysis at the single-cell level, allowing the study of telomeric imbalances in interphase nuclei.

3. Three-Dimensional Spatial Organization of Telomeres as a New Tool for Single-Cell Analysis

Combining QFISH, which paved the way for exploring the unique features of telomeres in single cells, with spatial telomere analysis enabled moving from mere assessment of telomere length to analyzing telomere distribution in the nucleus throughout the cell cycle [,]. In particular, TeloView®, a software that utilizes the 3D analysis of six key parameters generated from the telomeres of a single cell, allowed for identification and quantification of several crucial parameters of genomic instability (Table 1), such as the number of telomeres as an indicator of aneuploidy, their length as measured by relative fluorescent intensity, number of aggregates, the spatial distribution of telomeres throughout the cell cycle (axial or a/c ratio), nuclear volume, and the telomere numbers to the nuclear volume ratio [,,].

Table 1.

Telomeric parameters and their biological significance.

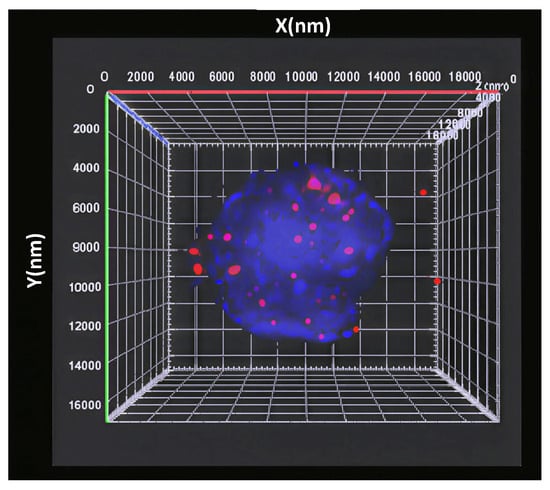

Spatial analysis revealed that the telomeres of the normal interphase nucleus exhibit a distinct 3D organization (Figure 1) that is cell-cycle-dependent [,]. In the G0/G1 and S phases, they demonstrate spherical-like volume distribution throughout the nucleus, and an axial (a/c) ratio, a measure of spatial telomeric distribution throughout the nucleus, close to 1.0. In contrast, the G2 phase of the cell cycle is associated with the 3D reorganization of telomeres into a flat telomeric disk, and a markedly higher a/c ratio [].

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional distribution of the telomeres, labelled by the fluorescent probe (red), in the nucleus (DAPI, blue).

Another characteristic feature of tumor cells is the presence of telomeric aggregates. These telomeric clusters cannot be further separated into individual telomeres at a resolution of 200 nm, and are characterized by a larger volume and stronger integrated intensity []. Studies showed that formation of telomeric aggregates is a multifactorial event that is linked to the deregulation of c-Myc, increased incidence of breakage-fusion-bridge cycles [], down-regulation of the telomere repeat binding protein (TRF2) [,], essential for telomere capping and genome stability [], changes in the expression of nuclear matrix and nucleoskeletal proteins [,] and viral infections (such as Epstein-Barr virus) [,,].

Spatial telomere analysis has demonstrated its unique utility in assessing genomic instability in several solid and hematological cancers, including Hodgkin lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute myeloid leukemia, glioblastoma, neuroblastoma, and prostate cancer [,,,,,,,,,]. In 2013, a proof-of-concept study by Klewes et al. [] analyzed for the first time the 3D telomeric structure of plasma cells from patients at various stages of multiple myeloma (MM), ranging from the early precursor stage to active disease and relapsed MM. The study showed that disease progression was associated with an increased number of aggregates and t-stumps (very short telomeres) [], accompanied by an increase in the nuclear volume of plasma cells. This was the first indication that the 3D reorganization of telomeres in myeloma cells may be potentially used for patient classification, paving the way for a growing body of research focused on the value of telomere profiling in risk-stratifying MM patients. This study is also the first to compare blood and bone marrow of MM patients and found no significant differences, thus suggesting that telomere profiling of cells in liquid biopsies can be used to assess MM status.

4. Risk-Stratification in MM: Current Advances and Challenges

A high heterogeneity of MM, along with its diverse genetic, molecular, and clinical profiles, drives variable disease behavior and treatment responses. Therefore, the ability to stratify patients by risk and monitor disease progression, both in the transition from precursor states to active MM, and as a measure of treatment response, plays a critical role in managing this heterogeneity.

4.1. Risk Assessment in Precursor States

Due to the increased risk of progression to lymphoproliferative malignancy, MGUS requires long-term follow-up, guided by risk stratification. MGUS patients are initially followed up six months after diagnosis, with subsequent visits scheduled according to the estimated risk of progression []. This risk is currently determined by the disease burden and the underlying cytogenetic type of the disease [,]. SMM is a heterogeneous disease with a significantly higher risk of progression: nearly 40% of SMM patients progress to MM within the first 5 years []. This makes SMM a critical stage for studying early intervention strategies and for developing sensitive risk-stratification models. Currently, risk stratification of SMM in clinical practice primarily relies on circulating plasma cell counts, the presence of M protein, serum biomarkers, and the percentage of bone marrow plasma cells (BMPC). For instance, a widely used 20/2/20 risk-stratification by Mayo Clinic classifies SMM patients into risk groups (low-, intermediate-, and high-risk) based on serum M-protein > 2 g/dL, BMPC > 20%, and an involved/uninvolved free light chain ratio > 20 []. These criteria were further refined by incorporating specific cytogenetic abnormalities, such as t(4;14), del(17p), hyperdiploidy with +1q, or t(14;16) []. Genomic profiling enabled the stratification of SMM into two categories: a more stable disease resembling MGUS and a more aggressive one, molecularly similar to MM []. In low-risk patients, early treatment with lenalidomide, either alone or in combination with dexamethasone, can delay progression and improve survival outcomes [,]. Based on the 20/2/20 criteria combined with cytogenetic assessment, a 2-year progression risk for patients with 2 or more risk factors is 44%. High-risk SMM patients are likely to progress to MM within 29 months [].

Early risk-stratification models in MM relied solely on the disease burden [] or the levels of serum albumin and β2-microglobulin []. The development of FISH technology enabled more sensitive genomics-based risk stratification, leading to the gradual integration of genomic profiling into existing clinical risk-assessment models [,,,]. In 2024, the International Myeloma Society (IMS) and IMWG incorporated chromosomal abnormalities, such as del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation, biallelic del(1p32), and two or more intermediate-risk rearrangements, such as 1q21+, t(4;14), t(14;16), and monoallelic del(1p32), into the MM scoring model, which allowed to classify 20% of newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) patients as high-risk []. In addition to predicting disease progression or patient survival, risk stratification of MM is crucial for developing personalized risk-adapted therapies, both in NDMM and in relapsed MM.

4.2. Minimal Residual Disease

Achievement of MRD negativity emerged as a strong and independent prognostic factor in the real-world setting []. While MRD assessment has become a validated endpoint in clinical trials [], its impact on treatment decisions is evolving. The current International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and MRD assessment require quantifying tumor burden after therapy in the bone marrow using highly sensitive methods, such as next-generation sequencing, next-generation flow cytometry, and imaging-based techniques (PET/CT, MRI) []. However, evaluating tumor burden alone cannot account for the inherent heterogeneous nature of MM, nor can it assess the development of treatment-resistant clones. It also fails to address clinically relevant questions that are essential for establishing a standard of care, such as whether it is safe to discontinue treatment with sustained MRD or whether MRD positivity justifies a new treatment. In NDMM patients who are candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), induction treatment combines the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab (D) with the triplet regimen of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTd) or bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRd), followed by transplantation []. However, in patients who are not high-risk, the ASCT may be delayed until the first relapse. Furthermore, while standard-risk patients may benefit from lenalidomide maintenance, some studies show that high-risk MM patients may require a bortezomib plus lenalidomide maintenance regimen []. At relapse, a triplet regimen is usually needed, and the choice of regimen varies with each successive relapse. In cases of heavily relapsed/refractory (R/R) patients, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell and T-cell redirecting bispecific antibody (BsAb) therapies have been shown to significantly improve response rates and durations []. In this setting, assessing treatment response and detecting high-risk MRD become crucial.

Clinically recognized MRD detection approaches, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), mass spectrometry (MS), and multiparametric next-generation flow cytometry (NGF) are limited to mere quantification of plasma cell sequences or plasma cells, respectively, in the bone marrow sample, without providing information on genomic instability present in single myeloma cells [,]. This further emphasizes that currently used risk-stratification approaches fail to identify the diversity of individual tumor cells and cannot distinguish between biologically different subclones associated with aggressive or indolent behavior. Given the heterogeneous nature of MM, developing single-cell–based approaches may enable more accurate identification of high-risk cellular populations and truly personalized disease monitoring.

5. Telomere Maintenance in Multiple Myeloma: Beyond Telomeric Length

Numerous studies demonstrated that the risk of developing MM is influenced by genetic variability [,,,,,,]. Karyotypic changes, including chromosomal gains or losses, translocations, and complex genomic rearrangements in malignant plasma cells, are considered a classical hallmark and an essential prognostic factor of MM [,,,,]. Of them, translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain region at chromosome 14q32 are most common in B-cell malignancies and are observed in approximately 40% of patients with MM []. The locus is positioned at the distal end of chromosome 14, within the telomeric region. Notably, several partner loci that participate in recurrent translocations (such as 4p16, 6p25, and 16q23) are also positioned at telomeric or subtelomeric regions, further confirming the potential role of spatial telomeric and chromosomal organization in these chromosomal alterations [].

5.1. Telomere Length in MM

Mounting evidence links MM risk to defects in telomere biology. Alterations in telomere length and architecture have been documented in plasma cell disorders []. In MM, malignant plasma cells exhibit increased telomerase activity and sustain short but stable telomeres [,,]. A 2012 study by la Guardia et al. [] used conventional methods of telomere assessment, such as cytogenetic analysis, telomere FISH, and spectral karyotyping (SKY), to show a high incidence of chromosomal translocations in chromosomes with loss of telomeric signals as a result of telomere shortening in MGUS and MM patients. Furthermore, telomeric attrition inversely correlated with the increase in the percentage of telomeric aggregates []. Hyatt et al. [] employed Single Telomere Length Analysis (STELA), a high-resolution technology for detecting telomeres within the telomeric fusion length ranges, to generate telomere length profiles of MGUS MM patients. The study revealed that both MGUS and MM bone marrow cohorts exhibited considerable heterogeneity in telomere length []. Similarly, Wu et al. [] evaluated the telomere length in bone marrow of 115 MM patients by TRF Southern blot analysis to report a significant positive correlation of telomerase activity and a negative correlation of telomere length with poor prognosis features of MM, suggesting that telomeric length is a prognostic marker in MM [,]. However, a specific subset of MM patients present with unusually long telomeres, related to the Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT) pathway during disease progression [,,,,]. This phenomenon of ALT involves inter-telomeric homologous recombination, reported primarily in carcinoma-derived cell lines [], and further emphasizes the high inherent heterogeneous genetic landscape of MM.

5.2. Spatial Telomere Organization in MM

The development of more advanced QFISH technology led to a more accurate assessment of the clonal diversity inherent to MM. Single-cell analysis using QFISH enabled the early detection of treatment-resistant, metastatic clones, indicative of clonal evolution and aggressiveness []. When Klewes et al. [] looked at the single-cell 3D telomere profiles of blood and bone marrow samples of patients diagnosed with MGUS and MM, as well as of patients who went into relapse (MMrel), they were able to show that during disease progression from MGUS to MM and MMrel, the number of aggregates and t-stumps, and the nuclear volume of plasma cells increased. Furthermore, disease progression from MGUS to MM to MMrel was associated with a gradual increase in telomere attrition. The average number of telomeric aggregates was also increased in myeloma cells that survived treatment (MMrel), thus suggesting an association with relapsed myeloma. However, the difference in the number of aggregates between MM and MMrel was not significant, which implies clone expansion of malignant plasma cell survivors or a constant level of dynamic 3D telomere remodeling without further increase in aggregates. This was the first study to demonstrate the utility of telomere profiles and 3D nuclear architecture of MM cells in patient stratification, considering the high heterogeneity of MM. The study was also the first to describe automated analysis of telomeric features to detect minimal residual disease (MRD). This study paved the way to a plethora of subsequent studies of spatial telomere organization in the context of MM.

A 2019 study by Yu et al. [] analyzed blood and bone marrow samples from 37 patients diagnosed with MGUS and 25 newly diagnosed with MM, and demonstrated a significant decrease in the average signal intensity (indicative of shorter telomere lengths), substantially shorter telomeres, an absence of very long telomeres, and an increased number of telomeres in MM cells compared to MGUS. MM plasma cells also had somewhat lower a/c ratio. A 2021 study by Rangel-Pozzo et al. [] compared different 3D telomere parameters from bone marrow samples of 214 untreated patients (54 MGUS, 24 SMM, and 136 MM) with a clinical follow-up of at least 60 months to investigate a potential prognostic role of telomere assessment in the spectrum of myeloma at diagnosis. The results demonstrated that the number of telomeres, their intensity, the number of aggregates, and the a/c ratio differed significantly across the MM spectrum. Moreover, the degree of genomic instability correlated with the disease stage, with the highest combined telomere changes found in the SMM and MM subgroups. Stratifying SMM patients based on 5-year clinical follow-up data (progression and survival) revealed that telomere profiles were a sensitive marker of disease aggressiveness, identifying two distinct groups of SMM patients: biologically inactive MGUS-like and malignant MM-like. SMM patients in the second group had higher telomere numbers and intensity, more telomeric aggregates, a higher a/c ratio, and a greater nuclear volume.

The study also showed that MM patients with progressive disease exhibited increased telomere signals, a higher number of telomere aggregates, and a higher a/c ratio, along with a decrease in nuclear volume, compared to MM patients with stable disease.

Furthermore, total and average telomere intensities were associated with shorter OS in the SMM and MM groups, confirming that telomere-related genomic instability correlates with disease aggressiveness and can assist in identifying high-risk patient populations.

Notably, in MM, the average intensity (telomere length below 13,500 arbitrary units) and an increased number of telomere aggregates (≥3) emerged as prognostic factors to identify high-risk patients with the progressive disease. This study [] provided the first evidence that prediction modes based on the single-cell analysis of telomeric parameters may be a potentially valuable tool if incorporated into existing risk stratification guidelines in clinical practice.

6. 3D Telomere Profile-Based Prediction Models for MM

Quantitative telomere analysis demonstrated that in both SMM and MM patients, differential telomere parameters enable the identification of stable or progressive disease and stratification of patients into high-risk and low-risk groups, and paved the way to incorporating telomere profiling into clinical scoring models. Such risk prediction models, developed based on telomere parameters and the 3D architecture of the nucleus, can be potentially used to guide evidence-based treatment decisions for MM patients at every stage of the disease progression, from MGUS to SMM to MM. Furthermore, telomere profiling may potentially predict the risk of relapse in MM patients post-treatment.

A proof-of-concept prospective study of 21 SMM patients revealed notable differences in telomeric parameters between SMM patients who progressed to MM within 2 years and those who remained stable for over 5 years []. The disease progression of high-risk SMM patients was confirmed clinically by MM-caused morbidity. SMM patient groups demonstrated distinct telomere profiles in the stable patients compared to those who progressed to full-stage MM across five independent telomeric parameters. A follow-up clinical validation study used an expanded cohort of 168 SMM patients, with 53 patients who progressed to symptomatic MM within 24 months (i.e., short progression) and 35 patients who remained in the SMM stage for 5+ years (i.e., long progression) []. Telomere length, the a/c ratio, the distribution of telomeres in the spatial volume of the nucleus, and nuclear volume were identified as predictors suitable for regression modeling. A developed predictive scoring model was able to stratify individual SMM patients based on the risk of progression to active MM. The highest sensitivity and specificity were achieved using 3 predictors, including the total telomere length, a/c ratio, and distribution of telomeres in the nuclear space. The predictive scoring model of the training set demonstrated superior accuracy of 80%, with sensitivities and specificities of 0.75 and 0.70, respectively. Furthermore, blind validation of the model using an additional cohort of 41 patients with short progression and 25 patients with long progression achieved a positive predictive value of 85% and a negative predictive value of 73%, with corresponding sensitivity and specificity of 83% and 76%, respectively. For the first time, a scoring model based on 3D telomere profiling was used as an accurate prognostic tool to stratify SMM patients into their respective risk groups. This scoring model, thus, may potentially contribute to evidence-based decision-making regarding treatment approaches for “high-risk” SMM patients and enable confident monitoring of “low-risk” SMM patients without therapeutic intervention.

Identifying NDMM patients with a high risk of developing drug resistance remains an important clinical need. Therefore, identifying newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) patients who will develop resistance to treatment before relapse may allow switching these patients to another treatment regimen to potentially prevent the relapse. A 2023 study [] of 178 NDMM patients who were followed longitudinally for up to 5 years, identified several MM risk groups, suggesting a clinical relevance of telomere profiling in predicting the risk of developing drug resistance and relapse up to ~13 months before the relapse itself.

The developed predictive scoring model that included telomeric parameters, such as telomere length, number of detectable telomeres, % of telomere stumps and the a/c ratio was able to predict the risk of relapse at the level of the individual patient with a specificity of 85% and sensitivity of 72%. Spatial telomere profiling, thus, emerged as a practical and accurate prognostic biomarker of the risk of NDMM patients to develop resistance to first-line therapy combinations.

The demonstrated utility of telomeric profiling in risk-stratification of MM and SMM strongly suggests that developing a similar scoring model for post-treatment patients with MRD may allow us to move beyond merely detecting and enumerating plasma cells, which are currently used in clinical practice. Telomere characteristics of residual MM clones may enable the identification of MRD positivity or negativity, concomitant with profiling the level of aggressiveness of the cells and clones identified. Furthermore, current technologies, such as NSG, flow cytometry, and mass spectroscopy, are predominantly applicable to bone marrow specimens [,]. This limits their applicability to monitor patients continuously, and does not take into account the heterogeneity of the MM. These limitations may be overcome by blood-based MRD evaluation. Levels of CTCs in the peripheral blood of myeloma patients are increasingly recognized as a prognostic biomarker for risk stratification in MM [] and identified as an independent prognostic factor in the context of the most effective standard of care for transplant-eligible NDMM [,]. A recent proof-of-concept study demonstrated concordance between 3D telomere profiles of myeloma plasma cells isolated from marrow samples or circulating myeloma plasma cells isolated from peripheral blood (liquid biopsy) of transplant-eligible MM patients []. These results demonstrated the potential of the 3D telomere profiling to monitor MRD in MM patients based on peripheral blood samples, liquid biopsies, from the point of diagnosis, without the need for marrow samples, potentially presenting a new generation of a minimally invasive assessment of disease stability or progression that will rely on assessing genomic instability for risk stratification beyond simple enumeration.

7. Incorporating Telomere Profiling into Current MM Risk-Stratification Frameworks: Future Perspectives

In light of the demonstrated value of 3D telomere profiling as a prognostic biomarker in MM, combining telomere profiling with currently accepted MM and SMM risk-stratification guidelines may offer a major advancement toward biologically informed, precision medicine. Telomere architecture on a single-cell level captures cellular heterogeneity that conventional models overlook. Therefore, integrating 3D telomere biomarkers with established clinical parameters may allow for better identification of high-risk patients likely to progress to symptomatic MM, refine monitoring strategies and treatment timing, bridge molecular and clinical risk assessment, and enhance early detection of aggressive disease.

The 2024 study by Kumar et al. [] assessed the correlation between the newly developed SMM scoring model based on 3D telomere profiling and the Mayo 20-2-20 scoring model currently used in clinical practice. The SMM cohort of 110 patients included 71 patients who were scored as high and 39 as low risk by the 20-2-20 model. The overall concordance between the telomere-based prediction and the 20-2-20 score was 53% (58/160) for the entire cohort, and 49% and 59% for short progression and long progression cohorts, respectively.

In a continuing analysis, 88 SMM patients from the original modeling cohort (low/intermediate and high risk of progression) were used to combine the SMM model. Developed based on the telomere profiling (which included parameters, such as a/c ratio, the total number of telomeric signals, and average distance of telomeres to the nuclear center) with the risk assessment of 2/20/20. The combination was able to identify high-risk SMM patients better than each scoring model alone. The reported receiver operator characteristics (ROC) for the 2/20/20 and the telomeric SMM scoring models were 0.64 and 0.77, respectively, whereas the ROC for the combined scoring was 0.80 []. The results clearly demonstrated that combining both scoring methods may considerably improve risk assessment and strongly suggest that telomere profiling has clinical value for future inclusion in SMM guidelines.

8. Conclusions

Three-dimensional telomere profiling represents a promising prognostic biomarker in MM, addressing a critical unmet need for more precise disease assessment. Quantitative telomere profiling evaluates spatial and structural dynamics of telomeres at the single-cell level, provides valuable insights into genomic instability and clonal evolution of MM, enables prediction of disease stage, progression risk, overall survival, and treatment response, and is potentially valuable for evidence-based treatment decisions. Including 3D telomere profiling in currently accepted models of MM risk stratification could enhance prognostic precision and support the development of personalized, risk-adapted therapeutic strategies.

Funding

S.M. is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Y.S. is employed by Telo Genomics Corp. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jafri, M.A.; Ansari, S.A.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Shay, J.W. Roles of telomeres and telomerase in cancer, and advances in telomerase-targeted therapies. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbe, L.; Jauch, A.; Naeger, C.M.; Holtgreve-Grez, H.; Karlseder, J. Telomere dysfunction as a cause of genomic instability in Werner syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.G.; Graves, H.A.; Guffei, A.; Ricca, T.I.; Mortara, R.A.; Jasiulionis, M.G.; Mai, S. Telomere-centromere-driven genomic instability contributes to karyotype evolution in a mouse model of melanoma. Neoplasia 2010, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.M.; Jamur, V.R.; Merfort, L.W.; Pozzo, A.R.; Mai, S. Three-dimensional nuclear telomere architecture and differential expression of aurora kinase genes in chronic myeloid leukemia to measure cell transformation. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albagoush, S.A.; Shumway, C.; Azevedo, A.M. Multiple Myeloma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abduh, M.S. An overview of multiple myeloma: A monoclonal plasma cell malignancy’s diagnosis, management, and treatment modalities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, D.J.; Kotb, R.; Louzada, M.L.; Sutherland, H.J.; Tavoularis, S.; Venner, C.P. Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma and Related Disorders: Recommendations of the Myeloma Canada Research Network Consensus Guideline Consortium. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020, 20, e352–e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Staging System for Multiple Myeloma. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2016, 35, e418–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaseb, H.; Annamaraju, P.; Babiker, H.M. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, R.A.; Rajkumar, S.V. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2010, 5, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R.A.; Remstein, E.D.; Therneau, T.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kurtin, P.J.; Hodnefield, J.M.; Larson, D.R.; Plevak, M.F.; Jelinek, D.F.; Fonseca, R.; et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2582–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R.A.; Rajkumar, S.V. Management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). Oncology 2011, 25, 578–586. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, N.H.; Lakshman, A.; Kumar, S.K.; Cook, J.; Binder, M.; Kapoor, P.; Dispenzieri, A.; Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Hayman, S.R.; et al. Mode of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma: A study of 406 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Bergsagel, P.L.; Kumar, S. Smoldering Multiple Myeloma: Observation Versus Control Versus Cure. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 38, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, N.S.; Kaufman, J.L.; Dhodapkar, M.V.; Hofmeister, C.C.; Almaula, D.K.; Heffner, L.T.; Gupta, V.A.; Boise, L.H.; Lonial, S.; Nooka, A.K. Long-Term Follow-Up Results of Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone Induction Therapy and Risk-Adapted Maintenance Approach in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Herrera, A.; Sarasquete, M.E.; Jiménez, C.; Puig, N.; García-Sanz, R. Minimal Residual Disease in Multiple Myeloma: Past, Present, and Future. Cancers 2023, 15, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenova, A.Y.; Zhuk, A.S.; Lada, A.G.; Zotova, I.V.; Stepchenkova, E.I.; Kostroma, I.I.; Gritsaev, S.V.; Pavlov, Y.I. Genome Instability in Multiple Myeloma: Facts and Factors. Cancers 2021, 13, 5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maura, F.; Bergsagel, P.L.; Ziccheddu, B.; Kumar, S.; Maclachlan, K.; Derkach, A.; Garces, J.J.; Firestone, R.; Braggio, E.; Asmann, Y.; et al. Genomics Define Malignant Transformation in Myeloma Precursor Conditions. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, Jco2501733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustad, E.H.; Yellapantula, V.; Leongamornlert, D.; Bolli, N.; Ledergor, G.; Nadeu, F.; Angelopoulos, N.; Dawson, K.J.; Mitchell, T.J.; Osborne, R.J.; et al. Timing the initiation of multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsagel, P.L.; Nardini, E.; Brents, L.; Chesi, M.; Kuehl, W.M. IgH translocations in multiple myeloma: A nearly universal event that rarely involves c-myc. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1997, 224, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.C.; Moshir, S.; Garini, Y.; Chuang, A.Y.; Young, I.T.; Vermolen, B.; van den Doel, R.; Mougey, V.; Perrin, M.; Braun, M.; et al. The three-dimensional organization of telomeres in the nucleus of mammalian cells. BMC Biol. 2004, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewes, L.; Vallente, R.; Dupas, E.; Brand, C.; Grün, D.; Guffei, A.; Sathitruangsak, C.; Awe, J.A.; Kuzyk, A.; Lichtensztejn, D.; et al. Three-dimensional Nuclear Telomere Organization in Multiple Myeloma. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 6, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wark, L.; Quon, H.; Ong, A.; Drachenberg, D.; Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Mai, S. Long-Term Dynamics of Three Dimensional Telomere Profiles in Circulating Tumor Cells in High-Risk Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Androgen-Deprivation and Radiation Therapy. Cancers 2019, 11, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermolen, B.J.; Garini, Y.; Mai, S.; Mougey, V.; Fest, T.; Chuang, T.C.; Chuang, A.Y.; Wark, L.; Young, I.T. Characterizing the three-dimensional organization of telomeres. Cytometry A 2005, 67, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Jevremovic, D.; Kyle, R.A.; Shifrin, Y.; Nguyen, M.; Husain, Z.; Alikhah, A.; Jafari, A.; Mai, S.; et al. Three-dimensional telomere profiling predicts risk of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaedbey, R.; Knecht, H.; Anderson, K.C.; Mai, S.; Louis, S. Preliminary results of 3D telomeres profiling for myeloma MRD and evaluation of concordance between blood and marrow. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, e19560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, T.; Cremer, C. Rise, fall and resurrection of chromosome territories: A historical perspective. Part II. Fall and resurrection of chromosome territories during the 1950s to 1980s. Part III. Chromosome territories and the functional nuclear architecture: Experiments and models from the 1990s to the present. Eur. J. Histochem. 2006, 50, 223–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, T.; Cremer, C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001, 2, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, H.; Ma, H.; Jiang, W.; Mela, C.A.; Duan, M.; Zhao, S.; Gao, C.; Hahm, E.R.; Lardo, S.M.; et al. Super-resolution imaging reveals the evolution of higher-order chromatin folding in early carcinogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Dai, W. Genomic Instability and Cancer. J. Carcinog. Mutagen. 2014, 5, 1000165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaninejad, A.; Ilkhani, K.; Marzban, H.; Navashenaq, J.G.; Rahimirad, S.; Radnia, F.; Yousefi, M.; Bahmanpour, Z.; Azhdari, S.; Sahebkar, A. Genomic Instability in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potentials. Curr Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 3161–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, A.; Schukken, K.M.; Sausville, E.L.; Girish, V.; Adebambo, O.A.; Sheltzer, J.M. Aneuploidy as a promoter and suppressor of malignant growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Shih, J.; Ha, G.; Gao, G.F.; Zhang, X.; Berger, A.C.; Schumacher, S.E.; Wang, C.; Hu, H.; Liu, J.; et al. Genomic and Functional Approaches to Understanding Cancer Aneuploidy. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 676–689.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, N.A.; Rass, E.; Scully, R. Deciphering the Code of the Cancer Genome: Mechanisms of Chromosome Rearrangement. Trends Cancer 2015, 1, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejowski, J.; de Lange, T. Telomeres in cancer: Tumour suppression and genome instability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, R.C.; Chang, S.; Maser, R.S.; Mohan, R.; Artandi, S.E.; Chin, L.; DePinho, R.A. Telomere dysfunction provokes regional amplification and deletion in cancer genomes. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoli, T.; Denchi, E.L.; de Lange, T. Persistent telomere damage induces bypass of mitosis and tetraploidy. Cell 2010, 141, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, T. Telomere-related genome instability in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2005, 70, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S. Initiation of telomere-mediated chromosomal rearrangements in cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010, 109, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, A.; Bryan, T.M. Telomere maintenance and the DNA damage response: A paradoxical alliance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1472906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdun, R.E.; Karlseder, J. Replication and protection of telomeres. Nature 2007, 447, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.D.; Comeau, L.; Rosenfield, S.; Stansel, R.M.; Bianchi, A.; Moss, H.; de Lange, T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell 1999, 97, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, W.; de Lange, T. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 301–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Déjardin, J.; Kingston, R.E. Purification of proteins associated with specific genomic Loci. Cell 2009, 136, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greider, C.W.; Blackburn, E.H. Telomeres, telomerase and cancer. Sci. Am. 1996, 274, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, C.P.; Codd, V. Genetic determinants of telomere length and cancer risk. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2020, 60, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Hou, S. The Association between Telomere Length and Cancer Prognosis: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, N.; Rachakonda, S.; Kumar, R. Telomeres and Telomere Length: A General Overview. Cancers 2020, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dratwa, M.; Wysoczańska, B.; Łacina, P.; Kubik, T.; Bogunia-Kubik, K. TERT-Regulation and Roles in Cancer Formation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 589929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Han, W.; Xue, W.; Zou, Y.; Xie, C.; Du, J.; Jin, G. The association between telomere length and cancer risk in population studies. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Qu, K.; Pang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C. Association between telomere length and survival in cancer patients: A meta-analysis and review of literature. Front. Med. 2016, 10, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.T.; Cesare, A.J.; Rivera, T.; Karlseder, J. Cell death during crisis is mediated by mitotic telomere deprotection. Nature 2015, 522, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciejowski, J.; Li, Y.; Bosco, N.; Campbell, P.J.; de Lange, T. Chromothripsis and Kataegis Induced by Telomere Crisis. Cell 2015, 163, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, M.A.; Lee, H.W.; Hande, M.P.; Samper, E.; Lansdorp, P.M.; DePinho, R.A.; Greider, C.W. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 1997, 91, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holesova, Z.; Krasnicanova, L.; Saade, R.; Pös, O.; Budis, J.; Gazdarica, J.; Repiska, V.; Szemes, T. Telomere Length Changes in Cancer: Insights on Carcinogenesis and Potential for Non-Invasive Diagnostic Strategies. Genes 2023, 14, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbini, E.; Trovesi, C.; Cassani, C.; Longhese, M.P. Telomere uncapping at the crossroad between cell cycle arrest and carcinogenesis. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2014, 1, e29901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Khoo, C.M.; Naylor, M.L.; Maser, R.S.; DePinho, R.A. Telomere-based crisis: Functional differences between telomerase activation and ALT in tumor progression. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, S.; Maolan, A.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Geer, E.; Pu, Z.; Hua, B.; et al. Telomeres, telomerase, and cancer: Mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutics. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A.; Tusell, L. Telomeres: Implications for Cancer Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artandi, S.E.; Chang, S.; Lee, S.L.; Alson, S.; Gottlieb, G.J.; Chin, L.; DePinho, R.A. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature 2000, 406, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Kacher, R.; Cuceu, C.; Al Jawhari, M.; Morat, L.; Frenzel, M.; Shim, G.; Lenain, A.; Hempel, W.M.; Junker, S.; Girinsky, T.; et al. The Transition between Telomerase and ALT Mechanisms in Hodgkin Lymphoma and Its Predictive Value in Clinical Outcomes. Cancers 2018, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vitis, M.; Berardinelli, F.; Sgura, A. Telomere Length Maintenance in Cancer: At the Crossroad between Telomerase and Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic, S.; Bubendorf, L. Common Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Applications in Cytology. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, G.H.; Khan, W.A. Utility of Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization in Clinical and Research Applications. Clin. Lab. Med. 2022, 42, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, S.S.; Martens, U.M.; Ward, R.K.; Lansdorp, P.M. Telomere length measurements using digital fluorescence microscopy. Cytometry 1999, 36, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.F.; Vermolen, B.J.; Garini, Y.; Young, I.T.; Guffei, A.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Kuttler, F.; Chuang, T.C.; Moshir, S.; Mougey, V.; et al. c-Myc induces chromosomal rearrangements through telomere and chromosome remodeling in the interphase nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9613–9618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermler, S.; Krunic, D.; Knoch, T.A.; Moshir, S.; Mai, S.; Greulich-Bode, K.M.; Boukamp, P. Cell cycle-dependent 3D distribution of telomeres and telomere repeat-binding factor 2 (TRF2) in HaCaT and HaCaT-myc cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 83, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, V.; Lemieux, B.; Sawan, B.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Wellinger, R.; Mai, S.; Knecht, H. LMP1 mediates multinuclearity through downregulation of shelterin proteins and formation of telomeric aggregates. Blood 2015, 125, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steensel, B.; Smogorzewska, A.; de Lange, T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell 1998, 92, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaha, N.; Hawkins, A.L.; Griffin, C.A.; Isaacs, W.B.; Coffey, D.S. High mobility group protein I(Y): A candidate architectural protein for chromosomal rearrangements in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, P.C.; Frank, S.R.; Wang, L.; Schroeder, M.; Liu, S.; Greene, J.; Cocito, A.; Amati, B. Genomic targets of the human c-Myc protein. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Brüderlein, S.; Mai, S.; Möller, P.; Sawan, B. 3D structural and functional characterization of the transition from Hodgkin to Reed-Sternberg cells. Ann. Anat. 2010, 192, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, H.; Johnson, N.A.; Haliotis, T.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Mai, S. Disruption of direct 3D telomere-TRF2 interaction through two molecularly disparate mechanisms is a hallmark of primary Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, H.; Mai, S. The Use of 3D Telomere FISH for the Characterization of the Nuclear Architecture in EBV-Positive Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1532, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadji, M.; Adebayo Awe, J.; Rodrigues, P.; Kumar, R.; Houston, D.S.; Klewes, L.; Dièye, T.N.; Rego, E.M.; Passetto, R.F.; de Oliveira, F.M.; et al. Profiling three-dimensional nuclear telomeric architecture of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia defines patient subgroups. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadji, M.; Fortin, D.; Tsanaclis, A.M.; Garini, Y.; Katzir, N.; Wienburg, Y.; Yan, J.; Klewes, L.; Klonisch, T.; Drouin, R.; et al. Three-dimensional nuclear telomere architecture is associated with differential time to progression and overall survival in glioblastoma patients. Neoplasia 2010, 12, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadji, M.; Vallente, R.; Klewes, L.; Righolt, C.; Wark, L.; Kongruttanachok, N.; Knecht, H.; Mai, S. Nuclear remodeling as a mechanism for genomic instability in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2011, 112, 77–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Yu, P.L.I.; La, L.S.; Asbaghi, Y.; Sisdelli, L.; Tammur, P.; Tamm, A.; Punab, M.; Klewes, L.; Louis, S.; et al. Telomere Architecture Correlates with Aggressiveness in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wark, L.; Danescu, A.; Natarajan, S.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, S.Y.; Hombach-Klonisch, S.; Mai, S.; Klonisch, T. Three-dimensional telomere dynamics in follicular thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2014, 24, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Sisdelli, L.; Cordioli, M.I.V.; Vaisman, F.; Caria, P.; Mai, S.; Cerutti, J.M. Genetic Landscape of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma and Nuclear Architecture: An Overview Comparing Pediatric and Adult Populations. Cancers 2020, 12, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caria, P.; Dettori, T.; Frau, D.V.; Lichtenzstejn, D.; Pani, F.; Vanni, R.; Mai, S. Characterizing the three-dimensional organization of telomeres in papillary thyroid carcinoma cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5175–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drachenberg, D.; Awe, J.A.; Rangel Pozzo, A.; Saranchuk, J.; Mai, S. Advancing Risk Assessment of Intermediate Risk Prostate Cancer Patients. Cancers 2019, 11, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Dos Santos, F.F.; Dettori, T.; Giulietti, M.; Frau, D.V.; Galante, P.A.F.; Vanni, R.; Pathak, A.; Fischer, G.; Gartner, J.; et al. Three-dimensional nuclear architecture distinguishes thyroid cancer histotypes. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 153, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Blackburn, E.H. Human cancer cells harbor T-stumps, a distinct class of extremely short telomeres. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, W.I.; Rajkumar, S.V. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, Itc177–Itc192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Gupta, V.; Fonseca, R.; Dispenzieri, A.; Gonsalves, W.I.; Larson, D.; Ketterling, R.P.; Lust, J.A.; Kyle, R.A.; Kumar, S.K. Impact of primary molecular cytogenetic abnormalities and risk of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1738–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neben, K.; Jauch, A.; Hielscher, T.; Hillengass, J.; Lehners, N.; Seckinger, A.; Granzow, M.; Raab, M.S.; Ho, A.D.; Goldschmidt, H.; et al. Progression in smoldering myeloma is independently determined by the chromosomal abnormalities del(17p), t(4;14), gain 1q, hyperdiploidy, and tumor load. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4325–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshman, A.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Buadi, F.K.; Binder, M.; Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Dispenzieri, A.; Dingli, D.; Fonder, A.L.; Hayman, S.R.; et al. Risk stratification of smoldering multiple myeloma incorporating revised IMWG diagnostic criteria. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.V.; Kumar, S.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; González-Calle, V.; Kastritis, E.; Hajek, R.; De Larrea, C.F.; Morgan, G.J.; Merlini, G.; Goldschmidt, H.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group risk stratification model for smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, N.; Maura, F.; Minvielle, S.; Gloznik, D.; Szalat, R.; Fullam, A.; Martincorena, I.; Dawson, K.J.; Samur, M.K.; Zamora, J.; et al. Genomic patterns of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Hussein, M.; Swern, A.S.; Weber, D. Impact of lenalidomide dose on progression-free survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2011, 25, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.V.; Hernández, M.T.; Giraldo, P.; de la Rubia, J.; de Arriba, F.; López Corral, L.; Rosiñol, L.; Paiva, B.; Palomera, L.; Bargay, J.; et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanwar, S.; Rajkumar, S.V. Current risk stratification and staging of multiple myeloma and related clonal plasma cell disorders. Leukemia 2025, 39, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durie, B.G.; Salmon, S.E. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma. Correlation of measured myeloma cell mass with presenting clinical features, response to treatment, and survival. Cancer 1975, 36, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greipp, P.R.; San Miguel, J.; Durie, B.G.; Crowley, J.J.; Barlogie, B.; Bladé, J.; Boccadoro, M.; Child, J.A.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Kyle, R.A.; et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3412–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, M.; Lauwers-Cances, V.; Hulin, C.; Leleu, X.; Caillot, D.; Escoffre, M.; Arnulf, B.; Macro, M.; Belhadj, K.; Garderet, L.; et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, W.J.; Dispenzieri, A.; Chim, C.S.; Fonseca, R.; Goldschmidt, H.; Lentzsch, S.; Munshi, N.; Palumbo, A.; Miguel, J.S.; Sonneveld, P.; et al. IMWG consensus on risk stratification in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2014, 28, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Oliva, S.; Lokhorst, H.M.; Goldschmidt, H.; Rosinol, L.; Richardson, P.; Caltagirone, S.; Lahuerta, J.J.; Facon, T.; et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2863–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, M.; Cairns, D.A.; Lahuerta, J.J.; Wester, R.; Bertsch, U.; Waage, A.; Zamagni, E.; Mateos, M.V.; Dall’Olio, D.; van de Donk, N.; et al. Second Revision of the International Staging System (R2-ISS) for Overall Survival in Multiple Myeloma: A European Myeloma Network (EMN) Report Within the HARMONY Project. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3406–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avet-Loiseau, H.; Davies, F.E.; Samur, M.K.; Corre, J.; D’Agostino, M.; Kaiser, M.F.; Raab, M.S.; Weinhold, N.; Gutierrez, N.C.; Paiva, B.; et al. International Myeloma Society/International Myeloma Working Group Consensus Recommendations on the Definition of High-Risk Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 2739–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plasma Cell Disease Group, Chinese Society of Hematology, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Myeloma Committee-Chinese Hematology Association. Expert consensus on the comprehensive management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma in China (2025). Chin. J. Hematol. 2025, 46, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.C.; Auclair, D.; Adam, S.J.; Agarwal, A.; Anderson, M.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Bustoros, M.; Chapman, J.; Connors, D.E.; Dash, A.; et al. Minimal Residual Disease in Myeloma: Application for Clinical Care and New Drug Registration. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5195–5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Paiva, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Durie, B.; Landgren, O.; Moreau, P.; Munshi, N.; Lonial, S.; Bladé, J.; Mateos, M.V.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e328–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Lipe, B.; Ocio, E.M.; Usmani, S.Z. Induction Therapy for Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, e176–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Shi, L.; Zou, D.; Feng, R.; Tian, W.W.; Yu, H.; Dong, F.; Liao, A.; Ma, Y.; et al. Lenalidomide or bortezomib as maintenance treatment remedy the inferior impact of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities in non-transplant patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A real-world multi-centered study in China. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1028571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, S.A.; Grant, S.J.; Wildes, T.M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell and Bispecific Antibody Therapy in Multiple Myeloma: Moving Into the Future. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4416–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Xu, J.; Lin, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Luo, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhai, X.; et al. Minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma: Current status. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, I.V.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Tsitsilonis, O.E.; Terpos, E. Minimal Residual Disease in Multiple Myeloma: Current Landscape and Future Applications With Immunotherapeutic Approaches. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, P.; Chubb, D.; Johnson, D.C.; Weinhold, N.; Försti, A.; Lloyd, A.; Olver, B.; Ma, Y.; Dobbins, S.E.; Walker, B.A.; et al. Common variation at 3p22.1 and 7p15.3 influences multiple myeloma risk. Nat. Genet. 2011, 44, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campa, D.; Martino, A.; Sainz, J.; Buda, G.; Jamroziak, K.; Weinhold, N.; Vieira Reis, R.M.; García-Sanz, R.; Jurado, M.; Ríos, R.; et al. Comprehensive investigation of genetic variation in the 8q24 region and multiple myeloma risk in the IMMEnSE consortium. Br. J. Haematol. 2012, 157, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chubb, D.; Weinhold, N.; Broderick, P.; Chen, B.; Johnson, D.C.; Försti, A.; Vijayakrishnan, J.; Migliorini, G.; Dobbins, S.E.; Holroyd, A.; et al. Common variation at 3q26.2, 6p21.33, 17p11.2 and 22q13.1 influences multiple myeloma risk. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, A.; Campa, D.; Buda, G.; Sainz, J.; García-Sanz, R.; Jamroziak, K.; Reis, R.M.; Weinhold, N.; Jurado, M.; Ríos, R.; et al. Polymorphisms in xenobiotic transporters ABCB1, ABCG2, ABCC2, ABCC1, ABCC3 and multiple myeloma risk: A case-control study in the context of the International Multiple Myeloma rESEarch (IMMEnSE) consortium. Leukemia 2012, 26, 1419–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, A.; Campa, D.; Jamroziak, K.; Reis, R.M.; Sainz, J.; Buda, G.; García-Sanz, R.; Lesueur, F.; Marques, H.; Moreno, V.; et al. Impact of polymorphic variation at 7p15.3, 3p22.1 and 2p23.3 loci on risk of multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2012, 158, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, N.; Johnson, D.C.; Chubb, D.; Chen, B.; Försti, A.; Hosking, F.J.; Broderick, P.; Ma, Y.P.; Dobbins, S.E.; Hose, D.; et al. The CCND1 c.870G>A polymorphism is a risk factor for t(11;14)(q13;q32) multiple myeloma. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, E.; Dean, E.; Hu, D.; Martino, A.; Serie, D.; Curtin, K.; Campa, D.; Aftab, B.; Bracci, P.; Buda, G.; et al. Corrigendum: Genome-wide association study identifies variants at 16p13 associated with survival in multiple myeloma patients. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manier, S.; Kawano, Y.; Bianchi, G.; Roccaro, A.M.; Ghobrial, I.M. Cell autonomous and microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression in precursor states of multiple myeloma. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2016, 23, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozin, I.B.; Pavlov, Y.I.; Goncearenco, A.; De, S.; Lada, A.G.; Poliakov, E.; Panchenko, A.R.; Cooper, D.N. Mutational signatures and mutable motifs in cancer genomes. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 1085–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flactif, M.; Zandecki, M.; Laï, J.L.; Bernardi, F.; Obein, V.; Bauters, F.; Facon, T. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as a powerful tool for the detection of aneuploidy in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 1995, 9, 2109–2114. [Google Scholar]

- Drach, J.; Schuster, J.; Nowotny, H.; Angerler, J.; Rosenthal, F.; Fiegl, M.; Rothermundt, C.; Gsur, A.; Jäger, U.; Heinz, R.; et al. Multiple myeloma: High incidence of chromosomal aneuploidy as detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 3854–3859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Han, K.; Drut, R.M.; Harris, C.P.; Meisner, L.F. Use of fluorescence in situ hybridization for retrospective detection of aneuploidy in multiple myeloma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1993, 7, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalff, A.; Spencer, A. The t(4;14) translocation and FGFR3 overexpression in multiple myeloma: Prognostic implications and current clinical strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2012, 2, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottliar, A.; Pedrazzini, E.; Corrado, C.; Engelberger, M.I.; Narbaitz, M.; Slavutsky, I. Telomere shortening in patients with plasma cell disorders. Eur. J. Haematol. 2003, 71, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.-D.; Orme, L.M.; Shaughnessy, J., Jr.; Jacobson, J.; Barlogie, B.; Moore, M.A.S. Telomerase and telomere length in multiple myeloma: Correlations with disease heterogeneity, cytogenetic status, and overall survival. Blood 2003, 101, 4982–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panero, J.; Arbelbide, J.; Fantl, D.B.; Rivello, H.G.; Kohan, D.; Slavutsky, I. Altered mRNA expression of telomere-associated genes in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple myeloma. Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiratsuchi, M.; Muta, K.; Abe, Y.; Motomura, S.; Taguchi, F.; Takatsuki, H.; Uike, N.; Umemura, T.; Nawata, H.; Nishimura, J. Clinical significance of telomerase activity in multiple myeloma. Cancer 2002, 94, 2232–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de la Guardia, R.; Catalina, P.; Panero, J.; Elosua, C.; Pulgarin, A.; López, M.B.; Ayllón, V.; Ligero, G.; Slavutsky, I.; Leone, P.E. Expression profile of telomere-associated genes in multiple myeloma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 3009–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, S.; Jones, R.E.; Heppel, N.H.; Grimstead, J.W.; Fegan, C.; Jackson, G.H.; Hills, R.; Allan, J.M.; Pratt, G.; Pepper, C.; et al. Telomere length is a critical determinant for survival in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 178, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, D.R.; Adams, A.M.; Berg, C.D.; Black, W.C.; Clapp, J.D.; Fagerstrom, R.M.; Gareen, I.F.; Gatsonis, C.; Marcus, P.M.; Sicks, J.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, D.; Martino, A.; Varkonyi, J.; Lesueur, F.; Jamroziak, K.; Landi, S.; Jurczyszyn, A.; Marques, H.; Andersen, V.; Jurado, M.; et al. Risk of multiple myeloma is associated with polymorphisms within telomerase genes and telomere length. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E351–E358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campa, D.; Mergarten, B.; De Vivo, I.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Racine, A.; Severi, G.; Nieters, A.; Katzke, V.A.; Trichopoulou, A.; Yiannakouris, N.; et al. Leukocyte telomere length in relation to pancreatic cancer risk: A prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 2447–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, J.O.; Keegan, J.; Flynn, R.L.; Heaphy, C.M. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: Mechanism and the pathogenesis of cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 18, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, J.D.; Neumann, A.A.; Yeager, T.R.; Reddel, R.R. Alternative lengthening of telomeres in mammalian cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Ory, B.; Lamoureux, F.; Heymann, M.F.; Heymann, D. Tumour Heterogeneity: The Key Advantages of Single-Cell Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.L.I.; Wang, Y.; Tammur, P.; Tamm, A.; Punab, M.; Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Mai, S. Distinct Nuclear Organization of Telomeresand Centromeres in Monoclonal Gammopathyof Undetermined Significance and Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2019, 8, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.; Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Knecht, H.; Mai, S. Three-Dimensional Telomere Analysis Using Teloview® Technology Identifies Smouldering Myeloma Patients with High Risk of Progression to Full Stage Multiple Myeloma in a Proof of Concept Cohort. Blood 2020, 136 (Suppl. S1), 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rajkumar, V.; Jevremovic, D.; Kyle, R.; Mai, S.; Louis, S. P975: THREE-DIMENSIONAL TELOMERE PROFILING PREDICTS RISK OF RELAPSE IN NEWLY DIAGNOSED MULTIPLE MYELOMA PATIENTS. Hemasphere 2023, 7 (Suppl. S3), e07945f9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foureau, D.; Bhutani, M.; Guo, F.; Rigby, K.; Leonidas, M.; Tjaden, E.; Fox, A.; Atrash, S.; Paul, B.; Voorhees, P.M.; et al. Comparison of mass spectrometry and flow cytometry in measuring minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 6933–6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, I.V.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Rousakis, P.; Malandrakis, P.; Panteli, C.; Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou, E.; Angelis, N.; Spiliopoulou, V.; Syrigou, R.E.; Bakouros, P.; et al. Low circulating tumor cell levels correlate with favorable outcomes and distinct biological features in multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertamini, L.; Oliva, S.; Rota-Scalabrini, D.; Paris, L.; Morè, S.; Corradini, P.; Ledda, A.; Gentile, M.; De Sabbata, G.; Pietrantuono, G.; et al. High Levels of Circulating Tumor Plasma Cells as a Key Hallmark of Aggressive Disease in Transplant-Eligible Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3120–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).