Abstract

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a class of respiratory viruses with the potential to cause severe respiratory diseases by infecting cells of the upper respiratory tract, bronchial epithelium, and lung. The airway cilia are distributed on the surface of respiratory epithelial cells, forming the first point of contact between the host and the inhaled coronaviruses. The function of the airway cilia is to oscillate and sense, thereby defending against and removing pathogens to maintain the cleanliness and patency of the respiratory tract. Following infection of the respiratory tract, coronaviruses exploit the cilia to invade and replicate in epithelial cells while also damaging the cilia to facilitate the spread and exacerbation of respiratory diseases. It is therefore imperative to investigate the interactions between coronaviruses and respiratory cilia, as well as to elucidate the functional mechanism of respiratory cilia following coronavirus invasion, in order to develop effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of respiratory viral infections. This review commences with an overview of the fundamental characteristics of airway cilia, and then, based on the interplay between airway cilia and coronavirus infection, we propose that ciliary protection and restoration may represent potential therapeutic approaches in emerging and re-emerging coronavirus pandemics.

1. Introduction

Mucociliary clearance (MCC) is a key self-protection mechanism in the human respiratory tract that functions to remove foreign pathogens from the airways. The function of the MCC depends primarily on the ciliated epithelial cells (CECs), as well as the mucus layer, which traps foreign pathogens, and a low-viscosity periciliary layer (PCL), which lubricates airway surfaces and facilitates ciliary beating for efficient mucus clearance [1]. As one of the essential components of the respiratory MCC, cilia beat in metachronous waves to expel pathogens and inhaled particles trapped in the mucus layer from the airways, thus playing an important role in defending the respiratory system against the invasion of pathogens and pollutants [2].

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are the major cause of respiratory infections. Seven known CoVs, namely HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, have been identified as human pathogens, with the latter three being highly pathogenic and capable of causing severe respiratory disease and even life-threatening illness [3]. The binding receptors for different coronaviruses can vary. For example, MERS-CoV uses dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), SARS-CoV employs angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), and SARS-CoV-2 utilizes both ACE2 and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2). Both ACE2 and TEMPRSS2 have been observed to localize extensively to the ciliary membranes of the respiratory tract [4]. Upon viral entry into the airways, the virus targets cilia or epithelial cells, leading to the disruption of ciliary motility and ultrastructure, and the dysfunction of mucociliary clearance, thereby facilitating host infection [5,6]. Concomitantly, the expression of cilia-associated cytoskeletal proteins undergoes substantial alterations. For instance, the ciliary structural proteins dynein axonemal heavy chain 7 (DNAH7), dynein axonemal intermediate chain 2 (DNAI2), and intraflagellar transport 27 (IFT27) have been demonstrated to exhibit a significant reduction in expression levels [5]. In particular, the intraflagellar transport (IFT) family has been shown to possess immunomodulatory functions, and the downregulation of IFT88 can affect the NF-κB signaling pathway and the expression of several downstream inflammatory cytokines [7]. In addition, upon viral entry into the respiratory tract, ciliated sensory receptors, including bitter taste receptors (T2Rs) and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, also respond. Of these, taste 2 receptor member 38 (TAS2R38) has been associated with the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, while transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is acutely activated by the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein, promoting apoptosis [8,9].

In conclusion, respiratory cilia fulfill a multitude of functions. In addition to their role in mucociliary clearance, airway cilia also engage in immunoregulatory and chemosensory activities. However, these functions of the cilia are frequently overlooked when investigating the prevention and treatment of respiratory viruses. Despite the fact that cilia represent the first point of contact between the respiratory tract and coronaviruses, there is still a need to gain a deeper understanding of how ciliary function and expression are altered during viral infection, as well as which cellular pathways are involved. This review will provide advanced insight into the dynamic relationship between cilia and coronaviruses, with the aim of elucidating the functions and regulatory mechanisms of airway cilia during coronavirus infection.

2. Airway Cilia

2.1. Structure and Distribution of Airway Cilia

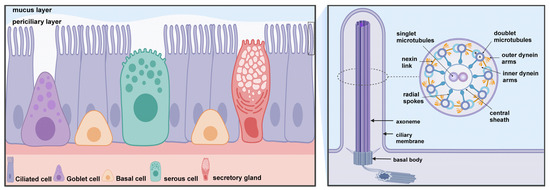

The epithelial surface of the respiratory tract is exposed to dust and pathogens on a daily basis, which presents a significant challenge to the respiratory system. Normal MCC plays a pivotal role in the prevention of damage caused by dust and pathogens and in the maintenance of respiratory defenses. The respiratory MCC consists of a motor system (cilia), a mucus blanket (mucus and periciliary layer), and mucus-secreting cells (goblet cells, serous cells, and secretory glands) [10].

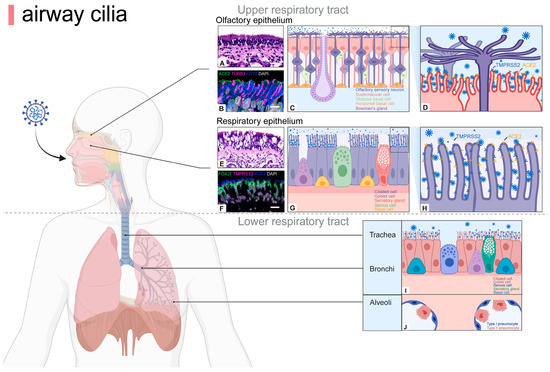

As a crucial component of the MCC, ciliated cells exhibit ubiquitous distribution along the entire respiratory epithelium, from the nasal cavities, sinuses, and pharynx to the epithelium of the trachea and bronchi (Figure 1). Cilia are morphologically tiny protrusions on the surface of cells, measuring 5 to 10 μm in length and approximately 0.2 μm in diameter. Each cell exhibits a cilia count of approximately 200–300, in addition to a considerable number of microvilli that extend from the respiratory epithelium [11]. The cilia are encapsulated by the cytoplasmic membrane and contain a basal body, axoneme, and ciliary matrix within their interior (Figure 2). The basal body represents the structure situated at the base of the cilium, serving as the anchor point for the cilium and playing a critical role in the formation and maintenance of the cilium. The axoneme constitutes a microtubular skeleton within the cilium. Cilia can be classified according to their axial structure, which distinguishes between motile cilia (“9 + 2” structure) and immotile cilia (“9 + 0” structure) [12]. The respiratory cilia follow the “9 + 2” pattern, comprising nine groups of microtubule doublets and a pair of single microtubules in the center. Each peripheral microtubule doublet is connected by a complete microtubule A and a “C”-shaped microtubule B, and is connected by a nexin-dynein regulatory complex (N-DRC), with microtubule A extending a radial spoke to connect the outer microtubule doublet to the central microtubule [13]. Meanwhile, two force arms, the outer dynein arm and the inner dynein arm, extended outward from microtubule A to adjacent microtubules B. These are bridging molecules between microtubules that allow adjacent microtubules to slide relative to each other, thereby providing the force for cilia oscillation. Moreover, the central microtubule, the radial spoke, and the N-DRC enable the regulation of the oscillatory form [14]. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a major source of energy to support the ciliary beat by facilitating relative sliding between microtubule dimers, thereby generating anteroposterior propulsion and causing the cilia to bend [15]. This suggests that the coordinated action of microtubules, ATP-driven dynein motors, and regulatory complexes generates ciliary movement.

Within the upper respiratory tract, the nasal epithelium is composed of two distinct types of nasal epithelium: respiratory epithelium (RE) and olfactory epithelium (OE), both of which contain basal cells (Figure 1). Basal cells can be divided into two types: horizontal basal cells (HBCs) and globular basal cells (GBCs). HBCs specifically express keratin 5/6/14 (KRT5/6/14), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), paired box 6 (PAX6), and SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2); while GBCs express SOX2 and mammalian achaete-scute homologue 1 (MASH1) [16]. Typically for the respiratory mucosa, ciliated cells express forkhead box protein J 1 (FOXJ1), epithelial cells express epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM), and the mucin-5AC (MUC5AC) labels goblet cells; while in the olfactory mucosa, olfactory marker protein (OMP) and tubulin beta 3 class III (TUBB3) are markers for mature olfactory neurons whose dendrites form cilia that specifically express acetyl-alpha tubulin and adenylate cyclase 3 (ADCY3), and sustentacular cells express KRT8, secretory cells specifically express BPI fold containing family A member 1 (BPIFA1) [17,18]. Despite the presence of cilia with a “9 + 2” structure in the olfactory sensory neurons (OSN) of the OE, the absence of dynein arms, which are necessary for movement, renders them incapable of movement. Consequently, their function is limited to odor detection through the interaction of receptors on dendritic cilia [19]. In the lower respiratory tract, the proportion of ciliated cells increases with the number of airway branches, from 47 ± 2% of the tracheal epithelium to 73 ± 1% of the small airway epithelium [20]. However, with the formation of the succeeding airways in the peripheral lungs, the length of the cilia gradually shortens [21].

Figure 1.

Airway cilia are distributed on the apical epithelial surface of upper and lower respiratory tracts. The nasal epithelium is divided into a RE and OE, whose functions and cell types differ. In the OE, cilia extend over the dendrites of mature olfactory neurons and are responsible for odor detection, whereas ciliated cells in the RE mainly play a role in cleaning pathogens. Moreover, the coronavirus-binding receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are markedly expressed on the cilia of respiratory epithelial cells and the microvilli of olfactory epithelial sustentacular cells, though not specifically localized on olfactory cilia (A–H). Brightfield images of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (A,E), confocal images of sections stained fluorescently with RNAscope and IHC (B,F) [18]. Thus, cilia at different sites may play different roles during viral infection. In the lower airways, ciliated cells are distributed in the epithelium of the trachea and bronchi for pathogen clearance (I,J). ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; FOXJ1, forkhead box protein J 1; KRT8, keratin 8; OE, olfactory epithelium; RE, respiratory epithelium; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2; TUBB3, tubulin beta 3 class III. Scale bars: 20 µm (A,F), 10 µm (B), 50 µm (E). Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 2.

Mucociliary clearance (MCC) consists of two primary components: motile cilia and mucus blanket (mucus and periciliary layer). MCC is a critical defense of the airways and is dependent on a highly coordinated ciliary function. Ciliary kinetic function is dependent on the special structure of the cilia. The core structure of the cilium is a highly conserved “9 + 2” axoneme that extends from the basal body in the apical region of ciliated cells into the periciliary layer, with the cilia tips reaching the mucus layer of the airway lumen. The ciliary axoneme consists of 9 groups of microtubule doublets and a pair of central single microtubules. Cilia contain a variety of protein complexes, including dynein arms, nexin link, radial spokes, and central sheath that connect the microtubules to each other. Created with BioRender.com.

Airway cilia have components typical of motile cilia. To investigate the structure and regulation of motile cilia, Chlamydomonas and Paramecium are often chosen as analogous models. It has been proven that motile cilia and eukaryotic flagella share the same basic biochemical mechanisms of motion generation and control [22]. Proteins from purified flagella of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii were identified by mass spectrometry, of which 360 proteins were identified with high confidence and a further 292 with moderate confidence [23]. Interestingly, homologues of these Chlamydomonas proteins have been identified by human genome sequencing [24]. In addition, proteomic analysis of cilia isolated from human airway epithelial cells in in vitro air-liquid interface (ALI) culture identified over 200 axonemal proteins, some of which are conserved with those found in other motile cilia [24], and a few proteins, such as sperm autoantigenic protein 17 (SPA17), sperm associated antigen 6 (SPAG6), and retinitis pigmentosa protein 1 (RP1), which is associated with photoreceptor axonemal structures, are unique [24]. Furthermore, characterization of the transcriptome of murine tracheal epithelial cells has revealed similarities between components of motile and primary cilia, and many of the genes identified as part of the mouse ciliary cell transcriptome correspond to human airway ciliary proteins, indicating the high degree of conservation of ciliary molecules across species [25].

2.2. Development and Function of Airway Cilia

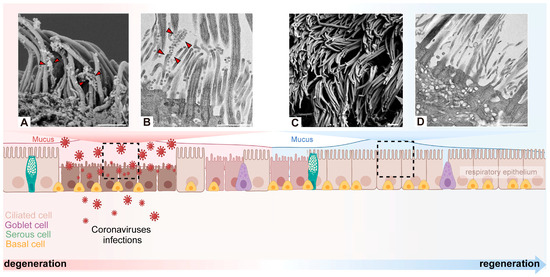

The development of respiratory cilia is a complex process that involves multiple stages, beginning with the embryonic phase and developing to the adult stage, where cilia undergo continuous renewal. In mice, the movement ciliary system, which is responsible for the clearance of amniotic fluid from the lungs, initiates on the third day of life [26]. The process of human airway ciliogenesis commences in the seventh week of embryonic development and ends prior to birth. Abnormal cilia at this stage have been associated with respiratory distress in newborns [27]. Specific genetic disorders, such as primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), also impact the development and functionality of the cilia. In this condition, the cilia are either absent or exhibit structural abnormalities that impede their ability to vibrate effectively, thereby impairing their capacity to clear the airways [28]. Previous studies have shown that airway cilia are mature and terminally differentiated after birth [29]. A defect in airway motile cilia may impair mucociliary clearance during the transition from fetal to neonatal life, leading to atelectasis and lobar collapse and causing neonatal respiratory distress [30]. More than 80% of neonates with primary ciliary dyskinesia develop symptoms within 1–2 days of birth [31]. Moreover, ciliated cells are capable of self-renewal. This indicates that aged cilia are replaced by new ones, a process that depends on the activity of basal stem cells to guarantee the continuity and efficacy of cilia function. Furthermore, damage to the cilia may occur when the respiratory tract is compromised, for instance, as a result of infection or the inhalation of pollutants. In such instances, ciliated cells initiate repair mechanisms with the objective of restoring the normal structure and function of the cilia [32] (Figure 3).

As constituent elements of the respiratory epithelium, cilia perform a variety of vital physiological functions. In addition to the aforementioned functions, airway cilia play a pivotal role in maintaining the function of mucus cilia as an “escalator” to ensure the airway remains unobstructed and clean [33]. Mucus is secreted by goblet cells and by mucous cells in the submucosal glands and is the primary line of defense for trapping particles [34]. The oscillatory movement of the cilia propels the mucus layer in a direction towards the oropharynx, thereby maintaining the cleanliness of the airways [35]. At the apical end of the respiratory cilia, there is a high concentration of mitochondria, which provide the energy necessary for ciliary movement and maintain the ability of the respiratory cilia to move autonomously [36]. Respiratory cilia are capable of oscillating and beating across multiple cells, thereby creating wave-like motions on the epithelial surface [37]. The speed of cilia movement is considerable, with the typical frequency of cilia oscillation being in the range of 10–20 Hz. The movement of cilia can facilitate the replacement of the mucus layer on the mucosal surface at a specific speed, with the mucosal layer being replaced two or three times per hour [38]. Ciliary movement also occurs in a specific direction. The ciliary movement of the upper respiratory tract expels mucus containing dust and pathogens from the nasal cavity into the nasopharynx. In the trachea and bronchi, the direction of ciliary movement is towards the throat, then slightly to the pharynx. Subsequently, the mucus mass is either swallowed or coughed out, resulting in a cleansing effect on the airways [39].

In addition to their function of cleaning the airways, respiratory cilia are also capable of sensing the presence of harmful substances entering the airways. In microarray expression data from primary cultures of differentiated human airway epithelia, the T2R family (such as T2R4, T2R43, T2R38, and T2R46) and T2R pathway-related proteins (such as α-gustducin, phospholipase C-β2 (PLC-β2), and transient receptor potential melastatin 5 (TRPM5) were found to be expressed in ciliated cells and specifically localized to cilia. Following the activation of T2R by the bitter compound denatonium, ciliary activity is stimulated, and the clearance of harmful substances is accelerated [40]. This suggests that respiratory cilia are capable of detecting signals and that the T2R signaling system may also be involved in the infection of respiratory pathogens. For instance, in cystic fibrosis, the lungs are typically infected with P. aeruginosa, which produces lactone quorum sensing molecules that can activate certain bitter receptors [41]. The expression of the bitter receptor TAS2R38, which is a modifier gene for cystic fibrosis, has been shown to correlate with the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This suggests that stimulating the expression of TAS2R38 may present a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection [9]. In addition, previous studies have indicated that a category of channel proteins that are responsible for sensory responses, namely TRP channel proteins, exhibit high levels of expression in the respiratory epithelium. For instance, TRPV4 is expressed on the ciliary membrane of airway epithelial cells and responds to mechanical loading, shear stress, and osmotic pressure by altering ciliary beat frequency [42]. In conclusion, the primary functions of airway cilia can be summarized as follows: first, they maintain respiratory cleanliness; second, they serve as sensors of the external environment. This enables them to play a crucial role in maintaining the homeostasis of the airway microenvironment and effectively clearing invading pathogens.

Figure 3.

Degeneration and regeneration of cilia after coronavirus infection. Coronavirus binds to the motile cilia during early viral infection. Representative images of virions attaching to motile cilia and causing extensive cilia lodging and axoneme rupture as observed by scanning electron microscope (A) or transmission electron microscopy (B) [43]. After coronavirus infection causes the loss of cilia, it triggers basal cells to differentiate into ciliated cells in order to maintain the homeostasis of the airway epithelium. Through scanning electron microscope and transmission electron microscope, it was observed that the normal cilia were densely arranged, protruding from the epithelial cells, with a diameter of about 250–500 nm and a length of 5–10 µm (C,D) [43]. Arrowhead: virus particles. Scale bars: 1 µm (A–D). Created with BioRender.com.

4. Therapeutic Measure

4.1. Targeting Viral Infection as Therapeutics

Over the past decade, three major outbreaks of coronaviruses have been documented. The first of these was SARS-CoV in 2002, followed by MERS-CoV in 2012 and then SARS-CoV-2 in 2019. Notwithstanding the advances in health infrastructure and the knowledge to control infectious diseases, the emergence and re-emergence of coronavirus pandemics may be precipitated by environmental and climate change. In order to be adequately prepared for the next global virus outbreak, it is imperative that broad-spectrum antivirals against highly pathogenic coronaviruses are developed. Despite the structural diversity of coronaviruses, the viral life cycle exhibits a number of common features, including entry, replication, assembly, and release. The design of antiviral drugs based on the different segments of the viral life cycle has yielded notable therapeutic outcomes (Table 2).

Firstly, to prevent viral entry, antivirals have been designed to target host viral receptors, including ACE2, TMPRSS2, NRP1, and DPP4. Drugs currently in development include ACE2 inhibitors, such as human recombinant soluble ACE2 (hrsACE2), which competitively binds to the S protein, thereby reducing damage to the lungs, kidneys, and heart [131]. Inhibitors of TMPRSS2, such as the serine protease inhibitor camostat mesylate (Ono Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan), have been demonstrated to impede the activity of TMPRSS2, thereby blocking the infection of lung cells by SARS-CoV-2 [132]. Pruxelutamide (Kintor, Suzhou, China), an androgen receptor antagonist, has been demonstrated to reduce the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and to inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines. This consequently prevents the onset of cytokine storms [133]. Inhibitors of NRP1, such as EG 00229 trifluoroacetate (Adooq Bioscience, Irvine, CA, USA), are small-molecule antagonists that have been shown to inhibit the binding of NRP1 to the S protein and diminish infectivity in vitro [134]. With regard to the DPP4 inhibitor, the amino acid residues responsible for binding DPP4 to SARS-CoV-2 were found to be identical to those that facilitate binding of DPP4 to MERS-CoV. Further investigation is required to ascertain the potential role of DPP4 inhibitors in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 [135]. Subsequent to the binding of coronaviruses to receptors, coronaviruses enter the cell by endocytosis. During this process, compounds such as apilimod (LAM Therapeutics, Livermore, CA, USA) and colchicine have been demonstrated to prevent viral entry by interfering with the transport and maturation of endosomes to lysosomes [136]. Chloroquine (CQ, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ, Sanofi, Paris, French) are antimalarial drugs that have been demonstrated to increase the pH of lysosomes and trans-Golgi network vesicles, thereby inhibiting viral invasion [137].

Secondly, a number of enzymes are involved in the synthesis of viral RNA, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), the 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), the papain-like Protease (PLpro) and the viral helicase. Drugs developed against these enzymes include RdRp inhibitors, such as remdesivir (Gilead Sciences), sofosbuvir (Gilead Sciences), and azvudine (Genuine Biotech, Pingdingshan, China). The inhibition of viral replication is achieved by blocking the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which results in the cessation of the process of reverse transcription [138,139,140]. Inhibitors of 3CLpro, such as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer, New York, NY, USA), have been demonstrated to effectively inhibit the replication of coronaviruses [141]. HL-21, a small molecule inhibitor of PLpro, has been shown to exhibit potent inhibitory activity against a number of coronaviruses [142]. Inhibitors of the helicase enzyme, such as SSYA10-001, aryl diketone acid (ADK), and dihydroxychromone, have the potential to disrupt the function of non-structural protein 13 (NSP13), which may result in the restriction of viral replication [143].

The final stage of the viral life cycle is viral assembly, which occurs after the complete viral genome has been translated into structural proteins. Inhibitors that target structural proteins can also exert an antiviral effect at this stage. Inhibitors of the E protein, including hexamethylene amiloride (HMA) and amantadine (AMT), as well as their combinations, have been identified as potential antiviral agents [144]. The N protein inhibitors PJ34 and 5-benzyloxylamine [145] and the S protein-neutralizing antibody 2G1 have been shown to exhibit antiviral properties [146].

4.2. Promoting Cilia Recovery as Therapeutics

In view of the fact that damage to the airway cilia caused by the coronavirus results in MCC dysfunction, there is a clear requirement for the development of drugs that enhance MCC and improve lung function (Table 2). For example, Bronchitol® (Pharmaxis Ltd., Sydney, Australia) is an inhaled mannitol dry powder preparation that has been demonstrated to enhance mucociliary clearance function by increasing the osmotic pressure of airway surface fluid [147]. The β-adrenergic agonists and cholinoids (such as acetylcholine and pilocarpine) can increase the frequency of airway ciliary beating and improve the efficiency of mucociliary clearance [148,149]. It has been observed that terbutaline (Sanofi) affects Cl− transport in the airway epithelium, thereby improving MCC [150]. Amiloride (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), a Na+ channel blocker, has been demonstrated to improve the viscosity of sputum and facilitate mucus clearance over an extended period, thereby protecting the airways from intraluminal obstruction and improving airflow [151]. The β-agonists such as salmeterol (GSK, London, UK) and salbutamol (GSK), have been shown to elevate intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, which in turn enhances the frequency of ciliary beating [152].

In addition to viral pathogenicity, ciliary dysfunction caused by the inflammatory response constitutes a significant contributory factor in the development of ARDS. It is therefore of the utmost importance to control cytokine production and the inflammatory response in cases of COVID-19. A number of immunomodulatory drugs have shown considerable therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of severe cases of the virus. For example, glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone (Merck), hydrocortisone (Merck), prednisolone (Merck), and methylprednisolone (Upjohn, Cecil Township, PA, USA) have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. However, the timing and dose of treatment must be considered during application [153]. Janus kinase inhibitors, such as baricitinib (Incyte, Wilmington, DE, USA), fostamatinib (RIGL, South San Francisco, CA, USA), nezulcitinib (TBPH, South San Francisco, CA, USA), ruxolitinib (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), and pacritinib (CTI BioPharma, Seattle, WA, USA), have been demonstrated to reduce inflammation by inhibiting the JAK-STAT pathway [154]. Interleukin receptor antagonists, including tocilizumab (CHGCY, Tokyo, Japan), sarilumab (Sanofi), and anakinra (Sobi, Stockholm, Sweden) have been demonstrated to reduce the inflammatory response by blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1 [155]. Interferons, such as IFN-α and IFN-β, are crucial in the antiviral immune response to viral infections [156]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as topotecan (GSK) and vilobelimab (InflaRx, Jena, Germany), have been shown to provide relief from hyperinflammatory symptoms and to prevent their progression [157].

Table 2.

Therapeutic measures.

Table 2.

Therapeutic measures.

| Viral Life Cycle | Potential Therapeutics | Direct and Indirection Associations with Cilia during Infection | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus ad-sorption Virus ad-sorption | 1 Human Recombinant Soluble ACE2 | ACE2 competes with S protein, thereby reducing the damage caused by the coronavirus to organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and heart. | [131] |

| 2 Camostat Mesilate | Inhibiting the activity of TMPRSS2 can block the infection of lung cells by SARS-CoV-2. | [132] | |

| 3 Pruxelutamide | Lowering the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2, while suppressing the production of inflammatory cytokines through activation of the NRF2 pathway. | [133] | |

| 4 EG 00229 trifluoroacetate | Inhibition of NRP1-S protein binding and reduction in virus infectivity. | [134] | |

| Virus entry | 1 Apilimod/Colchicine | Impacting the trafficking and maturation of lysosomes, thereby preventing the entry of viruses. | [136] |

| 2 Chloroquine (CQ)/Hydr-oxychloroquine (HCQ) | Increasing the pH of lysosomes and trans-Golgi network vesicles, thereby inhibiting virus assembly. | [137] | |

| Virus synthesis | 1 Remdesivir/Sofosbuvir/Azvudine | Inhibition of the virus RdRP leads to termination of the virus during the reverse transcription process, thereby inhibiting virus replication. | [138,139,140] |

| 2 Paxlovid | A potent inhibitor of 3CLpro can effectively inhibit the in vitro activity of coronavirus. | [142] | |

| 3 SSYA10-001/ADK/5,7-Dihydroxychromone | Inactivating NSP13 thereby inhibiting virus replication. | [143] | |

| Virus assembly | 1 PJ34/5-benzyloxygramine | N protein inhibitor. | [144] |

| 2 Hexamethylene amiloride (HMA)/Amantadine (AMT) | E protein inhibitor. | [145] | |

| 3 2G1 | S protein neutralizing antibody. | [146] | |

| 4 Glucocorticoid | Having anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. | [153] | |

| Cilium recovery | 1 Bronchitol® (Pharmaxis Ltd.) | By increasing the permeability of bile, enhancing the mucociliary clearance function. | [157] |

| Cilium recovery | 2 β-adrenergic receptor agonists | Increasing the frequency of ciliary beats in the respiratory tract to improve the efficiency of mucociliary clearance. | [148] |

| 3 Terbutaline | Influencing the transport of Cl− in the airway epithelium to enhance mucociliary clearance. | [150] | |

| 4 Amiloride | Long-term inhalation can improve the viscosity of sputum and mucociliary clearance, protecting the respiratory tract from intrapulmonary obstruction and improving airflow. | [151] | |

| 5 Acetylcholine/Pilocarpine | Increase in ciliary beat frequency. | [149] | |

| 6 Baricitinib/Fostamatinib/Nezulcitinib/Ruxolitinib/Pacritinib | Inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling pathway to alleviate inflammation. | [154] | |

| 7 Tocilizumab/Sarilumab /Anakinra | Blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1 to alleviate the inflammatory response. | [155] | |

| 8 IFN-α/IFN-β | Play a crucial role in the antiviral immune response against viral infections. | [156] | |

| 9 Topotecan/Vilobelimab | It can alleviate super-inflammatory symptoms to prevent them from becoming worse. | [157] |

Abbreviations: 3CLpro, 3-chymotrypsin like protease; ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; AMT, amantadine; CQ, chloroquine; E, envelope; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; HMA, hexamethylene amiloride; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; NRF2, nuclear respiratory factor 2; NRP1, neuropilin 1; N, nucleocapsids; NSP13, non-structural protein 13; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; S, spike; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2.

5. Conclusions

In summary, airway cilia play a pivotal role in the regulation of coronaviruses, which are involved in all stages of the viral life cycle and are controlled by multiple molecular mechanisms. Firstly, respiratory cilia constitute the primary line of defense in the airways, with the function of clearing pathogen-containing mucus through rhythmic beating. Secondly, the ciliary membrane expresses receptors that bind to viruses. Following the invasion of the airways by coronaviruses, specific targeting of cilia ensues, resulting in disruption to all aspects of cilia biology. These include alterations to motility, beat coordination, ultrastructure. and gene expression, which collectively lead to the rapid destruction of the MCC, thereby facilitating further spread. In addition, respiratory cilia are involved in the processing of sensory receptor responses, the regulation of inflammatory pathway signaling, and the monitoring of immune surveillance. Cilia are capable of detecting foreign substances, such as viruses, and initiating an immune response, which in turn triggers the release of inflammatory mediators. This attracts immune cells to the site of infection, where they can clear the infection. Nevertheless, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the mechanical and signaling sensing functions of cilia, as well as the molecular mechanisms promoting the development of respiratory disease following the loss of these functions due to ciliary damage, remain unclear and require further investigation. It can thus be proposed that the maintenance of respiratory cilia health and functionality represents a significant strategy for the prevention and treatment of coronaviruses. Further elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of coronavirus-induced ciliary damage may facilitate the development of novel treatment options for respiratory infections. The appropriate pharmacological targeting of respiratory cilia, such as the enhancement of their sensing function to increase their mechanical clearance ability, may improve the clearance of viruses and prevent their entry into cells.

In addition, in the context of the relationship between upper and lower respiratory cilia and coronaviruses, it has been established that the nasal cavity contains two distinct types of cilia: respiratory cilia and olfactory cilia (Figure 1). The primary function of the respiratory cilia is to assist in the clearance of foreign particles and microorganisms, including dust, bacteria, and viruses. Olfactory cilia are primarily responsible for the detection of odor molecules in the air and are involved in the formation of olfactory perception. Nevertheless, the coronavirus-binding receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are markedly expressed on the cilia of respiratory epithelial cells and the microvilli of olfactory epithelial sustentacular cells, though not specifically localized on olfactory cilia. Thus, various types of cilia may have different roles to play in the process of coronavirus entering the respiratory tract. In addition, following a respiratory infection, the upper and lower respiratory tract cilia move in different directions to transport mucus containing dust and pathogens to the pharynx, where the mucus ball is either swallowed or coughed out to clear the airway. However, the specific regulatory mechanisms and functional differences between upper and lower airway cilia remain unclear. Further studies of respiratory cilia are required to gain insight into the potential heterogeneity of cilia, both between different regions of the respiratory tract and within the same region. This will enable an investigation of whether heterogeneity in respiratory cilia is associated with the symptoms of different respiratory infections caused by coronaviruses and facilitate the development of specific treatments for the symptoms of different respiratory infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and R.X.; methodology, N.L., R.X. and X.D.; software, X.D.; validation, N.L., R.X. and X.D.; writing—original draft preparation, X.D.; writing—review and editing, N.L. and R.X.; visualization, X.D.; supervision, N.L. and R.X.; project administration, N.L.; funding acquisition, N.L. and R.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The laboratory of the authors benefits from ongoing support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82141220 and 82104672); TCM Theory Inheritance and Innovation Project of CACMS Innovation Fund (KYG-202405); the Scientific and Technological Innovation Project, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CI2021A00609 and CI2021A00112); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (YPX-202301).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhenji Li from World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies for his support and valuable input.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; ATP5F1E, ATP synthase F1 subunit epsilon; ATP5MC2, ATP synthase membrane subunit C locus 2; ATP5MG, ATP synthase membrane subunit G; AHI1, Abelson helper integration site 1; ADCY3, adenylate cyclase 3; ADK, aryl diketone acid; AMT, amantadine; ALI, air-liquid interface; BPIFA1, BPI fold containing family A member 1; CoVs, coronaviruses; CECs, ciliated epithelial cells; 3CLpro, 3-chymotrypsin like protease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CSF3, colony-stimulating factor 3; CCDC, coiled-coil domain containing; CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1; CCR, C-C motif chemokine receptor; CNGA2, cyclic nucleotide gated channel subunit alpha 2; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; CD, cluster of differentiation; CQ, chloroquine; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; CRHR1, corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; DNAH, dynein axonemal heavy chain; DNAI, dynein axonemal intermediate chain; DNAAF, dynein axonemal assembly factor; DNAJB13, dnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member B13; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; EPCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; EVs, extracellular vesicles; E, envelope; FOXJ1, forkhead box protein J 1; GBCs, globose basal cells; HBECs, human bronchial epithelial cells; HBCs, horizontal basal cells; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; HMA, hexamethylene amiloride; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; hrsACE2, human recombinant soluble ACE2; ICAM1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IFT, intraflagellar transport; IFN, interferon; IL, Interleukin; KRT, keratin; LRRC56, leucine-rich repeat containing 56; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; LKB1, liver kinase B1; LZTFL1, leucine zipper transcription factor like 1; MCC, mucociliary clearance; MCT, mucociliary transport; MASH1, mammalian achaete-scute homologue 1; MUC, mucin; N-DRC, nexin-dynein regulatory complex; NRF2, nuclear respiratory factor 2; NRP1, neuropilin 1; N, nucleocapsids; NEK10, NIMA related kinase 10; NSF, N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor; NSP13, non-structural protein 13; OE, olfactory epithelium; OSN, olfactory sensory neurons; OMP, olfactory marker protein; ODAD2, outer dynein arm docking complex subunit 2; ORF10, open reading frame 10; PCL, periciliary layer; PAX6, paired box 6; PIVs, parainfluenza viruses; PCD, primary ciliary dyskinesia; PLC-β2, phospholipase C-β2; PLAC8, placenta associated 8; PLpro, papain-like Protease; PKD1, Polycystin 1; RBD, receptor-binding domain; RE, respiratory epithelium; RP1, retinitis pigmentosa protein 1; RVs, rhinoviruses; RSVs, respiratory syncytial viruses; RFX3, regulatory factor X3; RSPH, radial spoke head Component; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; S, spike; STK36, serine/threonine kinase 36; SIT1, signaling threshold regulating transmembrane adaptor 1; SPA17, sperm autoantigenic protein 17; SPAG6, sperm associated antigen 6; SOX2, SRY-box transcription factor 2; SLC6A20, solute carrier family 6 member 20; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2; T2Rs, bitter taste receptors; TRP, transient receptor potential; TAS2R38, taste 2 receptor member 38; TRPV4, transient receptor potential vanilloid 4; TRPM5, transient receptor potential melastatin 5; TUBB3, tubulin beta 3 class III; TMIE, transmembrane inner ear; UGT, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase.

References

- Knowles, M.R.; Boucher, R.C. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuek, L.E.; Lee, R.J. First contact: The role of respiratory cilia in host-pathogen interactions in the airways. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2020, 319, L603–L619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J.S.; Chu, C.M.; Cheng, V.C.; Chan, K.S.; Hung, I.F.; Poon, L.L.; Law, K.I.; Tang, B.S.; Hon, T.Y.; Chan, C.S.; et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: A prospective study. Lancet 2003, 361, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, T.; Lee, I.T.; Jiang, S.; Matter, M.S.; Yan, C.H.; Overdevest, J.B.; Wu, C.T.; Goltsev, Y.; Shih, L.C.; Liao, C.K.; et al. Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication in airway mucosal tissue and susceptibility in smokers. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinot, R.; Hubert, M.; de Melo, G.D.; Lazarini, F.; Bruel, T.; Smith, N.; Levallois, S.; Larrous, F.; Fernandes, J.; Gellenoncourt, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces the dedifferentiation of multiciliated cells and impairs mucociliary clearance. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cai, S.; Feng, H.; Cai, B.; Lin, L.; Mai, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, A.; Huang, H.; Shi, J.; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals bronchoalveolar epithelial dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. Protein Cell 2020, 11, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Fie, M.; Koneva, L.; Collins, I.; Coveney, C.R.; Clube, A.M.; Chanalaris, A.; Vincent, T.L.; Bezbradica, J.S.; Sansom, S.N.; Wann, A.K.T. Ciliary proteins specify the cell inflammatory response by tuning NFκB signalling, independently of primary cilia. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs239871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Liu, S.; Yan, H.; Lu, W.; Shan, X.; Chen, H.; Bao, C.; Feng, H.; Liao, J.; Liang, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain perturbates intracellular calcium homeostasis and impairs pulmonary vascular endothelial cells. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, M.A.; Hall, C.A.; Shortess, C.J.; Rathbone, R.F.; Barham, H.P. Treatment Protocol for COVID-19 Based on T2R Phenotype. Viruses 2021, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitsett, J.A. Airway Epithelial Differentiation and Mucociliary Clearance. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, S143–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, M.; Dong, D.; Xie, S.; Liu, M. Environmental pollutants damage airway epithelial cell cilia: Implications for the prevention of obstructive lung diseases. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klena, N.; Pigino, G. Structural Biology of Cilia and Intraflagellar Transport. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 38, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horani, A.; Ferkol, T.W. Understanding Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia and Other Ciliopathies. J. Pediatr. 2021, 230, 15–22.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, J.; Meng, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Lu, G.; Lin, G.; Liu, M.; Tan, Y.Q. DRC3 is an assembly adapter of the nexin-dynein regulatory complex functional components during spermatogenesis in humans and mice. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Okada, K.; Raytchev, M.; Smith, M.C.; Nicastro, D. Structural mechanism of the dynein power stroke. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z. The microRNA/TET3/REST axis is required for olfactory globose basal cell proliferation and male behavior. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e49431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifton, C.; Niemeyer, B.F.; Novak, R.; Can, U.I.; Hainline, K.; Benam, K.H. BPIFA1 is a secreted biomarker of differentiating human airway epithelium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1035566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Yoo, S.J.; Clijsters, M.; Backaert, W.; Vanstapel, A.; Speleman, K.; Lietaer, C.; Choi, S.; Hether, T.D.; Marcelis, L.; et al. Visualizing in deceased COVID-19 patients how SARS-CoV-2 attacks the respiratory and olfactory mucosae but spares the olfactory bulb. Cell 2021, 184, 5932–5949.e5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbacher, K.; Fleischer, J.; Breer, H. Formation and maturation of olfactory cilia monitored by odorant receptor-specific antibodies. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 123, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, T.; O’Connor, T.P.; Hackett, N.R.; Wang, W.; Harvey, B.G.; Attiyeh, M.A.; Dang, D.T.; Teater, M.; Crystal, R.G. Quality control in microarray assessment of gene expression in human airway epithelium. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, R.; Turk, M. Cellular structure, function and organization in the lower respiratory tract. Environ. Health Perspect. 1984, 55, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satir, P. CILIA: Before and after. Cilia 2017, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazour, G.J.; Agrin, N.; Leszyk, J.; Witman, G.B. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrowski, L.E.; Blackburn, K.; Radde, K.M.; Moyer, M.B.; Schlatzer, D.M.; Moseley, A.; Boucher, R.C. A proteomic analysis of human cilia: Identification of novel components. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2002, 1, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoh, R.A.; Stowe, T.R.; Turk, E.; Stearns, T. Transcriptional program of ciliated epithelial cells reveals new cilium and centrosome components and links to human disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, R.J.; Chatterjee, B.; Loges, N.T.; Zentgraf, H.; Omran, H.; Lo, C.W. Initiation and maturation of cilia-generated flow in newborn and postnatal mouse airway. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009, 296, L1067–L1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moscoso, G.J.; Driver, M.; Codd, J.; Whimster, W.F. The morphology of ciliogenesis in the developing fetal human respiratory epithelium. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1988, 183, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.; Hogg, C. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Recent advances in epidemiology, diagnosis, management and relationship with the expanding spectrum of ciliopathy. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2012, 6, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, A.E.; Walters, M.S.; Shaykhiev, R.; Crystal, R.G. Cilia dysfunction in lung disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2015, 77, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, H. Formation and function of multiciliated cells. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202307150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machogu, E.; Gaston, B. Respiratory Distress in the Newborn with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Children 2021, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, T.; Allnoch, L.; Beythien, G.; Marek, K.; Becker, K.; Schaudien, D.; Stanelle-Bertram, S.; Schaumburg, B.; Mounogou Kouassi, N.; Beck, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Dysregulates Cilia and Basal Cell Homeostasis in the Respiratory Epithelium of Hamsters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicioni, G.; Ceppe, A.; Ford, A.A.; Alexis, N.E.; Barr, R.G.; Bleecker, E.R.; Christenson, S.A.; Cooper, C.B.; Han, M.K.; Hansel, N.N.; et al. Airway mucin MUC5AC and MUC5B concentrations and the initiation and progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Ehre, C.; Abdullah, L.H.; Sheehan, J.K.; Roy, M.; Evans, C.M.; Dickey, B.F.; Davis, C.W. Munc13-2−/− baseline secretion defect reveals source of oligomeric mucins in mouse airways. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 1977–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleigh, M.A.; Blake, J.R.; Liron, N. The propulsion of mucus by cilia. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1988, 137, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkawa, M. Big steps toward understanding dynein. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, E.R.; Wallingford, J.B. Multiciliated cells. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R973–R982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mall, M.A. Role of cilia, mucus, and airway surface liquid in mucociliary dysfunction: Lessons from mouse models. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2008, 21, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Hamblett, N.; Ramsey, B.W.; Kronmal, R.A. Advancing outcome measures for the new era of drug development in cystic fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2007, 4, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.S.; Ben-Shahar, Y.; Moninger, T.O.; Kline, J.N.; Welsh, M.J. Motile cilia of human airway epithelia are chemosensory. Science 2009, 325, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.R.; Shoemark, A.; Palau, H.L.; Murphy, R.A.; Simbo, A.; Bush, A.; Alton, E.; Davies, J.C. 93 Determining the impact of the T2R38 bitter taste receptor on P. aeruginosa infection in the cystic fibrosis airway. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, Y.N.; Fernandes, J.; Lorenzo, I.M.; Arniges, M.; Valverde, M.A. Frontiers in Neuroscience the TRPV4 Channel in Ciliated Epithelia. In TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades; Liedtke, W.B., Heller, S., Eds.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group, LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.T.; Lidsky, P.V.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, R.; Lee, I.T.; Nakayama, T.; Jiang, S.; He, W.; Demeter, J.; Knight, M.G.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 replication in airway epithelia requires motile cilia and microvillar reprogramming. Cell 2023, 186, 112–130.e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.I.; Barclay, W.S.; Zambon, M.C.; Pickles, R.J. Infection of human airway epithelium by human and avian strains of influenza a virus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8060–8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Bukreyev, A.; Thompson, C.I.; Watson, B.; Peeples, M.E.; Collins, P.L.; Pickles, R.J. Infection of ciliated cells by human parainfluenza virus type 3 in an in vitro model of human airway epithelium. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.S.; Ong, H.H.; Yan, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Ong, Y.K.; Thong, K.T.; Choi, H.W.; Wang, D.Y.; Chow, V.T. In Vitro Model of Fully Differentiated Human Nasal Epithelial Cells Infected with Rhinovirus Reveals Epithelium-Initiated Immune Responses. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Peeples, M.E.; Boucher, R.C.; Collins, P.L.; Pickles, R.J. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human airway epithelial cells is polarized, specific to ciliated cells, and without obvious cytopathology. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5654–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reznik, G.K. Comparative anatomy, physiology, and function of the upper respiratory tract. Environ. Health Perspect. 1990, 85, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vogalis, F.; Hegg, C.C.; Lucero, M.T. Ionic conductances in sustentacular cells of the mouse olfactory epithelium. J. Physiol. 2005, 562, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungnak, W.; Huang, N.; Bécavin, C.; Berg, M.; Queen, R.; Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-López, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Sampaziotis, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinskey, J.M.; Franks, N.E.; McMellen, A.N.; Giger, R.J.; Allen, B.L. Neuropilin-1 promotes Hedgehog signaling through a novel cytoplasmic motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15192–15204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essaidi-Laziosi, M.; Brito, F.; Benaoudia, S.; Royston, L.; Cagno, V.; Fernandes-Rocha, M.; Piuz, I.; Zdobnov, E.; Huang, S.; Constant, S.; et al. Propagation of respiratory viruses in human airway epithelia reveals persistent virus-specific signatures. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, M.A.; McKean, M.; Rutman, A.; Myint, B.S.; Silverman, M.; O’Callaghan, C. The effects of coronavirus on human nasal ciliated respiratory epithelium. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 18, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrich, B.M.; Goshtasbi, K.; Raad, R.A.; Ganti, A.; Papagiannopoulos, P.; Tajudeen, B.A.; Kuan, E.C. Aggregate Prevalence of Chemosensory and Sinonasal Dysfunction in SARS-CoV-2 and Related Coronaviruses. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 163, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerkin, R.C.; Ohla, K.; Veldhuizen, M.G.; Joseph, P.V.; Kelly, C.E.; Bakke, A.J.; Steele, K.E.; Farruggia, M.C.; Pellegrino, R.; Pepino, M.Y.; et al. Recent Smell Loss Is the Best Predictor of COVID-19 among Individuals with Recent Respiratory Symptoms. Chem. Senses 2021, 46, bjaa081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menni, C.; Valdes, A.M.; Freidin, M.B.; Sudre, C.H.; Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Ganesh, S.; Varsavsky, T.; Cardoso, M.J.; El-Sayed Moustafa, J.S.; et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brann, D.H.; Tsukahara, T.; Weinreb, C.; Lipovsek, M.; Van den Berge, K.; Gong, B.; Chance, R.; Macaulay, I.C.; Chou, H.J.; Fletcher, R.B.; et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodoulian, L.; Tuberosa, J.; Rossier, D.; Boillat, M.; Kan, C.; Pauli, V.; Egervari, K.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Landis, B.N.; Carleton, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptors and Entry Genes Are Expressed in the Human Olfactory Neuroepithelium and Brain. iScience 2020, 23, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfì, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniasiaya, J.; Islam, M.A.; Abdullah, B. Prevalence of Olfactory Dysfunction in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Meta-analysis of 27,492 Patients. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazhytska, M.; Kodra, A.; Hoagland, D.A.; Frere, J.; Fullard, J.F.; Shayya, H.; McArthur, N.G.; Moeller, R.; Uhl, S.; Omer, A.D.; et al. Non-cell-autonomous disruption of nuclear architecture as a potential cause of COVID-19-induced anosmia. Cell 2022, 185, 1052–1064.e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Yan, W.; Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Ma, K.; Xu, D.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. BMJ 2020, 368, m1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victores, A.J.; Chen, M.; Smith, A.; Lane, A.P. Olfactory loss in chronic rhinosinusitis is associated with neuronal activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.J.; Lee, A.C.; Chu, H.; Chan, J.F.; Fan, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, S.; Poon, V.K.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infects and Damages the Mature and Immature Olfactory Sensory Neurons of Hamsters. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e503–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, J.B.; Brann, D.H.; Abi Hachem, R.; Jang, D.W.; Oliva, A.D.; Ko, T.; Gupta, R.; Wellford, S.A.; Moseman, E.A.; Jang, S.S.; et al. Persistent post-COVID-19 smell loss is associated with immune cell infiltration and altered gene expression in olfactory epithelium. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eadd0484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, J.F.; Shastri, A.J.; Fletez-Brant, K.; Aslibekyan, S.; Auton, A. The UGT2A1/UGT2A2 locus is associated with COVID-19-related loss of smell or taste. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgoz Karaosmanoglu, A.; Ozgen, B. Anatomy of the Pharynx and Cervical Esophagus. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2022, 32, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, K.; Yoshimoto, S.; Nishi, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Ohno, J.; Yoshimura, M.; Hiromatsu, K.; Yamano, T. Epipharyngeal Abrasive Therapy Down-regulates the Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors ACE2 and TMPRSS2. In Vivo 2022, 36, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, K.; Yoshimoto, S.; Nishi, S.; Nishi, T.; Nishi, R.; Tsunoda, T.; Morita, H.; Tanaka, H.; Hotta, O.; Yasumasu, S.; et al. Epipharyngeal Abrasive Therapy Down-regulates the Expression of Cav1.2: A Key Molecule in Influenza Virus Entry. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnari, G.; Sanfilippo, C.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Imbesi, R.; Li Volti, G.; Barbagallo, I.; Musumeci, G.; Di Rosa, M. Network perturbation analysis in human bronchial epithelial cells following SARS-CoV2 infection. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 395, 112204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaofi, A.L. Exploring structural dynamics of the MERS-CoV receptor DPP4 and mutant DPP4 receptors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 752–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajkowska, J.M.; Hermanowska-Szpakowicz, T.; Pancewicz, S.; Kondrusik, M.; Grygorczuk, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)--new, unknown disease? Pol. Merkur. Lek. 2004, 16, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, L.M.; Duff, A.; Brennan, C. Airway Clearance Techniques for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia; is the Cystic Fibrosis literature portable? Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2018, 25, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.C.; Geoghegan, L.; Arbyn, M.; Mohammed, Z.; McGuinness, L.; Clarke, E.L.; Wade, R.G. The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.J.; Hui, C.K.M.; Hull, J.H.; Birring, S.S.; McGarvey, L.; Mazzone, S.B.; Chung, K.F. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: Role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajiri, T.; Kawachi, H.; Yoshida, H.; Noguchi, S.; Terashita, S.; Ikeue, T.; Horikawa, S.; Sugita, T.; Niimi, A. The causes of acute cough: A tertiary-care hospital study in Japan. J. Asthma 2021, 58, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Zhou, W.; Sun, J.; Li, C.; Zhong, B.; Lai, K. IFN-γ Enhances the Cough Reflex Sensitivity via Calcium Influx in Vagal Sensory Neurons. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesenak, M.; Durdik, P.; Oppova, D.; Franova, S.; Diamant, Z.; Golebski, K.; Banovcin, P.; Vojtkova, J.; Novakova, E. Dysfunctional mucociliary clearance in asthma and airway remodeling—New insights into an old topic. Respir. Med. 2023, 218, 107372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.R.; Matthay, M.A. Acute lung injury: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2010, 23, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, M.; Marino, A.; Pulvirenti, S.; Coco, V.; Busà, B.; Nunnari, G.; Cacopardo, B.S. Bacterial and Fungal Co-Infections and Superinfections in a Cohort of COVID-19 Patients: Real-Life Data from an Italian Third Level Hospital. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 14, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Garcia, M.A.; Aksamit, T.R.; Aliberti, S. Bronchiectasis as a Long-Term Consequence of SARS-COVID-19 Pneumonia: Future Studies are Needed. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 739–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retuerto-Guerrero, M.; López-Medrano, R.; de Freitas-González, E.; Rivero-Lezcano, O.M. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria, Mucociliary Clearance, and Bronchiectasis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, J.F.; Leroux, M.R. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Yang, B.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 impairs cilia by enhancing CUL2ZYG11B activity. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, e202108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.; van Putten, J.P.M.; Strijbis, K. Defensive Properties of Mucin Glycoproteins during Respiratory Infections-Relevance for SARS-CoV-2. mBio 2020, 11, e02374-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.S.L.; Goutaki, M.; Harris, A.L.; Dixon, L.; Manion, M.; Rindlisbacher, B.; Patient Advisory Group, C.P.; Lucas, J.S.; Kuehni, C.E. SARS-CoV-2 infections in people with primary ciliary dyskinesia: Neither frequent, nor particularly severe. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2004548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhaddou, M.; Memon, D.; Meyer, B.; White, K.M.; Rezelj, V.V.; Correa Marrero, M.; Polacco, B.J.; Melnyk, J.E.; Ulferts, S.; Kaake, R.M.; et al. The Global Phosphorylation Landscape of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell 2020, 182, 685–712.e619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. A first update on mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 2022, 608, E1–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. A second update on mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 2023, 621, E7–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.T.; Nakayama, T.; Wu, C.T.; Goltsev, Y.; Jiang, S.; Gall, P.A.; Liao, C.K.; Shih, L.C.; Schürch, C.M.; McIlwain, D.R.; et al. ACE2 localizes to the respiratory cilia and is not increased by ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.H.; Kim, J.; Hong, S.P.; Choi, S.Y.; Yang, M.J.; Ju, Y.S.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, H.M.; Rahman, M.D.T.; Chung, M.K.; et al. Nasal ciliated cells are primary targets for SARS-CoV-2 replication in the early stage of COVID-19. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e148517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, R.; Yan, R. Structures of ACE2-SIT1 recognized by Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.C.; Scheller, R.H. SNAREs and NSF in targeted membrane fusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997, 9, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Promchan, K.; Jiang, H.; Awasthi, P.; Marshall, H.; Harned, A.; Natarajan, V. Depletion of BBS Protein LZTFL1 Affects Growth and Causes Retinal Degeneration in Mice. J. Genet. Genom. 2016, 43, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink-Baldauf, I.M.; Stuart, W.D.; Brewington, J.J.; Guo, M.; Maeda, Y. CRISPRi links COVID-19 GWAS loci to LZTFL1 and RAVER1. eBioMedicine 2022, 75, 103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacentine, I.V.; Nicolson, T. Subunits of the mechano-electrical transduction channel, Tmc1/2b, require Tmie to localize in zebrafish sensory hair cells. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockx, M.; Gouwy, M.; Ruytinx, P.; Lodewijckx, I.; Van Hout, A.; Knoops, S.; Pörtner, N.; Ronsse, I.; Vanbrabant, L.; Godding, V.; et al. Monocytes from patients with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia show enhanced inflammatory properties and produce higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viau, A.; Bienaimé, F.; Lukas, K.; Todkar, A.P.; Knoll, M.; Yakulov, T.A.; Hofherr, A.; Kretz, O.; Helmstädter, M.; Reichardt, W.; et al. Cilia-localized LKB1 regulates chemokine signaling, macrophage recruitment, and tissue homeostasis in the kidney. Embo J. 2018, 37, e98615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, K.A.; Song, C.J.; Gonzalez-Mize, N.; Li, Z.; Yoder, B.K. Primary cilia disruption differentially affects the infiltrating and resident macrophage compartment in the liver. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 314, G677–G689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zha, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Lv, W. Transcriptomic and Lipidomic Profiles in Nasal Polyps of Glucocorticoid Responders and Non-Responders: Before and After Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 814953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnapaiyan, S.; Parira, T.; Dutta, R.; Agudelo, M.; Morris, A.; Nair, M.; Unwalla, H.J. HIV Infects Bronchial Epithelium and Suppresses Components of the Mucociliary Clearance Apparatus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Barbosa, T.; Alves, Â.; Santos, R.; Oliveira, J.; Sousa, M. Unveiling the genetic etiology of primary ciliary dyskinesia: When standard genetic approach is not enough. Adv. Med. Sci. 2020, 65, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, J.H.; Li, W.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: A functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 2738–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Berardi, M.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Dormitzer, P.R.; Harrison, S.C. Conformational states of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein ectodomain. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6794–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Hui, D.S.; Perlman, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015, 386, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazour, G.J.; Witman, G.B. The vertebrate primary cilium is a sensory organelle. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.M.; Yang, C.X.; Tam, A.; Shaipanich, T.; Hackett, T.L.; Singhera, G.K.; Dorscheid, D.R.; Sin, D.D. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: Implications for COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverkamp, A.K.; Lehmbecker, A.; Spitzbarth, I.; Widagdo, W.; Haagmans, B.L.; Segalés, J.; Vergara-Alert, J.; Bensaid, A.; van den Brand, J.M.A.; Osterhaus, A.; et al. Experimental infection of dromedaries with Middle East respiratory syndrome-Coronavirus is accompanied by massive ciliary loss and depletion of the cell surface receptor dipeptidyl peptidase 4. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, J.M.; Poon, L.L.; Lee, K.C.; Ng, W.F.; Lai, S.T.; Leung, C.Y.; Chu, C.M.; Hui, P.K.; Mak, K.L.; Lim, W.; et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Subbarao, K. The Immunobiology of SARS. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 443–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Zheng, J.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. SARS-CoV-2 infection of sustentacular cells disrupts olfactory signaling pathways. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e160277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkard, C.; Verheije, M.H.; Wicht, O.; van Kasteren, S.I.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.; Haagmans, B.L.; Pelkmans, L.; Rottier, P.J.; Bosch, B.J.; de Haan, C.A. Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieczkarski, S.B.; Whittaker, G.R. Dissecting virus entry via endocytosis. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, P.; Liu, K.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla-Herman, A.; Ghossoub, R.; Blisnick, T.; Meunier, A.; Serres, C.; Silbermann, F.; Emmerson, C.; Romeo, K.; Bourdoncle, P.; Schmitt, A.; et al. The ciliary pocket: An endocytic membrane domain at the base of primary and motile cilia. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugalde, A.P.; Bretones, G.; Rodríguez, D.; Quesada, V.; Llorente, F.; Fernández-Delgado, R.; Jiménez-Clavero, M.; Vázquez, J.; Calvo, E.; Tamargo-Gómez, I.; et al. Autophagy-linked plasma and lysosomal membrane protein PLAC8 is a key host factor for SARS-CoV-2 entry into human cells. Embo J. 2022, 41, e110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Shen, H.M. Targeting the Endocytic Pathway and Autophagy Process as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy in COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeboom, R.G.H.; Worlock, K.B.; Dratva, L.M.; Yoshida, M.; Scobie, D.; Wagstaffe, H.R.; Richardson, L.; Wilbrey-Clark, A.; Barnes, J.L.; Kretschmer, L.; et al. Human SARS-CoV-2 challenge uncovers local and systemic response dynamics. Nature 2024, 631, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zuo, K.; Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, F.; Lai, Y.; Shi, J. WDPCP regulates the ciliogenesis of human sinonasal epithelial cells in chronic rhinosinusitis. Cytoskeleton 2017, 74, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Jawdat, D.; Hajeer, A.H.; Sadat, M.; Jose, J.; Vishwakarma, R.K.; Almashaqbeh, W.; Al-Dawood, A. Inflammatory Response and Phenotyping in Severe Acute Respiratory Infection From the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus and Other Etiologies. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J.; Jiang, B.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Imported Cases of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Jiangsu Province: A Multicenter Descriptive Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josset, L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Agnihothram, S.; Sova, P.; Carter, V.S.; Yount, B.L.; Graham, R.L.; Baric, R.S.; Katze, M.G. Cell host response to infection with novel human coronavirus EMC predicts potential antivirals and important differences with SARS coronavirus. mBio 2013, 4, e00165-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faure, E.; Poissy, J.; Goffard, A.; Fournier, C.; Kipnis, E.; Titecat, M.; Bortolotti, P.; Martinez, L.; Dubucquoi, S.; Dessein, R.; et al. Distinct immune response in two MERS-CoV-infected patients: Can we go from bench to bedside? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacon-Heszele, M.F.; Choi, S.Y.; Zuo, X.; Baek, J.I.; Ward, C.; Lipschutz, J.H. The exocyst and regulatory GTPases in urinary exosomes. Physiol. Rep. 2014, 2, e12116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Q.; Zhou, J. Ciliary ectosomes: Critical microvesicle packets transmitted from the cell tower. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 2674–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, K.; Ijaz, F. Current understandings of the relationship between extracellular vesicles and cilia. J. Biochem. 2021, 169, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoufaly, A.; Poglitsch, M.; Aberle, J.H.; Hoepler, W.; Seitz, T.; Traugott, M.; Grieb, A.; Pawelka, E.; Laferl, H.; Wenisch, C.; et al. Human recombinant soluble ACE2 in severe COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Wotring, J.W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Pretto, C.D.; Eyunni, S.; Parolia, A.; He, T.; et al. Proxalutamide reduces SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221809120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Miller, S.; Patek, M.; Moutal, A.; Duran, P.; Cabel, C.R.; Thorne, C.A.; Campos, S.K.; Khanna, R. Novel Compounds Targeting Neuropilin Receptor 1 with Potential To Interfere with SARS-CoV-2 Virus Entry. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Lian, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Xin, S.; Cao, P.; Lu, J. The MERS-CoV Receptor DPP4 as a Candidate Binding Target of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike. iScience 2020, 23, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, P.; Mi, D.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Guo, R.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Rhodes, A.; Cheng, A.C.; Peacock, S.J.; Prescott, H.C. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Tian, L.; Liu, Y.; Hui, N.; Qiao, G.; Li, H.; Shi, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Xie, X.; et al. A promising antiviral candidate drug for the COVID-19 pandemic: A mini-review of remdesivir. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 201, 112527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jácome, R.; Campillo-Balderas, J.A.; Ponce de León, S.; Becerra, A.; Lazcano, A. Sofosbuvir as a potential alternative to treat the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Chang, J. The first Chinese oral anti-COVID-19 drug Azvudine launched. Innovation 2022, 3, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Ma, P.; Wang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ye, L.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, C. Efficacy and safety of Paxlovid for COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2023, 86, 66–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Weber, G.; Khoury, J.; Amar, M.; Stein, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Saliba, W. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in Reducing Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Mortality in High-Risk Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, A.N.; Gallazzi, F.; Quinn, T.P.; Lorson, C.L.; Sönnerborg, A.; Singh, K. Coronavirus helicases: Attractive and unique targets of antiviral drug-development and therapeutic patents. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, R.; Lee, I.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Meng, X. Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 E Protein: Sequence, Structure, Viroporin, and Inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Du, N.; Lei, Y.; Dorje, S.; Qi, J.; Luo, T.; Gao, G.F.; Song, H. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. Embo J. 2020, 39, e105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Guo, Y.; Tang, H.; Tseng, C.K.; Wang, L.; Zong, H.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Broad ultra-potent neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants by monoclonal antibodies specific to the tip of RBD. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.D.; Daviskas, E.; Brannan, J.D.; Chan, H.K. Repurposing excipients as active inhalation agents: The mannitol story. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 133, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, W.D. Effect of beta-adrenergic agonists on mucociliary clearance. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 110, S291–S297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iravani, J.; Melville, G.N. [Effects of drugs and environmental factors on ciliary movement (author’s transl)]. Respiration 1975, 32, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, B.; Marin, M.G.; Yee, J.W.; Nadel, J.A. Effect of terbutaline on movement of Cl− and Na+ across the trachea of the dog in vitro. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1979, 120, 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.R.; Church, N.L.; Waltner, W.E.; Yankaskas, J.R.; Gilligan, P.; King, M.; Edwards, L.J.; Helms, R.W.; Boucher, R.C. A pilot study of aerosolized amiloride for the treatment of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devalia, J.L.; Sapsford, R.J.; Rusznak, C.; Toumbis, M.J.; Davies, R.J. The effects of salmeterol and salbutamol on ciliary beat frequency of cultured human bronchial epithelial cells, in vitro. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1992, 5, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, R.S.; Raza, K.; Cooper, M.S. Therapeutic glucocorticoids: Mechanisms of actions in rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbing, J.; Sánchez Nievas, G.; Falcone, M.; Youhanna, S.; Richardson, P.; Ottaviani, S.; Shen, J.X.; Sommerauer, C.; Tiseo, G.; Ghiadoni, L.; et al. JAK inhibition reduces SARS-CoV-2 liver infectivity and modulates inflammatory responses to reduce morbidity and mortality. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, C.M.; Rénia, L.; MacAry, P.A.; Ng, L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Moreira Silva, E.A.S.; Medeiros Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Campos, V.H.S.; Ferreira, T.S.; Santos, C.V.Q.; Nogueira, A.M.R.; Almeida, A.; Savassi, L.C.M.; et al. Early Treatment with Pegylated Interferon Lambda for COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perico, N.; Cortinovis, M.; Suter, F.; Remuzzi, G. Home as the new frontier for the treatment of COVID-19: The case for anti-inflammatory agents. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, e22–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).