Abstract

Sweet corn (Zea mays var. saccharata) is a widely cultivated crop valued for its sweet flavor and high nutritional content. Over the past decade, the area devoted to sweet corn grain production has increased substantially, driven by both its nutritional qualities and its economic value. In this context, we aimed to evaluate the impact of three genotypes (Royalty F1, Hardy F1 and Deliciosul de Bacau,) under two fertilization types (chemical and organic) compared with a control version on yield, biometrical, biochemical, and quality parameters. This research was carried out between 2022 and 2023 at an experimental station situated in the North-East region of Romania. The results revealed significant influences of cultivar, fertilization method, and the interaction between these two experimental factors on most of the analyzed indicators. Regardless of the fertilization type, the genotype Hardy F1 showed higher levels of photosynthetic activity, polyphenols (2.22 mg/g d.w.) and sucrose (6.7 g/100 g d.w.), leading to greater yield (13,995 kg/ha) than that of Deliciosul de Bacau and Royalty F1. Research on fertilization has shown that sweet corn grains under an organic method have higher levels of lycopene, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total phenolic content (TPC), and fructose. In contrast, chemical fertilization more effectively supported growth, photosynthetic activity, yield, and the content of antioxidants and tannins. Regarding the combined influence of these factors, most of the nutritional characteristics of Royalty F1 were enhanced by organic fertilization, whereas those of the Hardy F1 genotype were improved by chemical fertilization. These findings provide practical guidance for selecting appropriate genotype–fertilization combinations to optimize the yield and nutritional quality of sweet corn and highlight key priorities for further research on sustainable fertilization strategies under climate change conditions.

1. Introduction

Corn is the most widely cultivated crop worldwide, followed by rice and wheat. In 2024/2025, the global corn production exceeded 1.2 billion tons [1], reflecting its critical role in food security [2], industrial applications, and biofuel production [3,4]. Sweet corn, a type of common corn, plays a significant role in the overall market due to increasing consumer demand for nutritious and convenient vegetables [5,6]. Sweet corn is widely cultivated globally because of its unique taste and versatility in human diets. It is rich in compounds with antioxidant effects, such as glutathione and linoleic acid [7]. Field-grown corn is primarily used for industrial processing, harvested at the milk stage when its sugar content peaks, resulting in a sweeter taste and softer texture, making it also suitable to be consumed fresh, in addition to canned or frozen, as a staple food in diets worldwide, particularly in North and South America, Europe, and, increasingly, some areas in Asia [8].

Sweet corn is particularly appreciated for its substantial carbohydrate content, mainly consisting of soluble sugars and starch, which supply readily available energy as well as a sustained energy release following consumption [9,10,11,12]. In addition to these energy-yielding primary metabolites, sweet corn contains significant amounts of dietary fiber, supporting a healthy microbiome, contributing to overall digestive health [13]. Sweet corn is an excellent source of vitamin C, an essential nutrient that acts as a powerful antioxidant, protecting cells from oxidative stress and supporting immune function [14]. It also provides significant amounts of B-complex vitamins, including thiamine (B1), niacin (B3), and folate (B9), which are indispensable for energy metabolism, red blood cell formation, and maintaining neurological health [15,16]. From a mineral perspective, sweet corn supplies magnesium, potassium, and phosphorus, each of which plays a vital role in cardiovascular health, muscle contraction, and bone health maintenance [17]. Additionally, sweet corn is recognized for its high content of bioactive compounds, particularly carotenoids and polyphenols. These compounds exhibit strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, making sweet corn a functional food with the potential to reduce the risk of chronic diseases [18]. Carotenoids, such as lutein and zeaxanthin, are well known for their oxidative role, particularly in terms of eye health, where they help reduce the risk of degeneration [19]. Beta-carotene serves as a precursor to vitamin A, which is essential for maintaining vision, supporting immune function, promoting skin health, and regulating reproductive processes. Additionally, it acts as an antioxidant, protecting cells from damage caused by free radicals. This protective role may reduce the risk of chronic diseases, including cancer and cardiovascular conditions [20,21]. The polyphenols present in sweet corn further contribute to its antioxidant capacity, help neutralize free radicals and reduce inflammation, a precursor to many chronic conditions, including cardiovascular diseases and certain types of cancer [22,23].

Although sweet corn nutritional quality is strongly influenced by genotype and agronomic management, including fertilization and irrigation [24,25], differences between organic and conventional systems may affect both yield and the accumulation of bioactive compounds. Organic production is often associated with higher antioxidant and secondary metabolite contents due to enhanced natural defense responses and slower, more sustainable nutrient uptake [26,27,28], promoting the accumulation of polyphenols and carotenoid pigments [29,30,31,32]. In contrast, conventional agriculture generally supports higher yields but may negatively affect soil quality and product composition under intensive chemical input use, raising concerns regarding long-term sustainability under climate change conditions [33,34,35]. While the effects of organic fertilization on secondary metabolites are well documented, limited information is available regarding genotype-specific responses and genotype × fertilization interaction effects on sweet corn nutritional quality and biochemical composition.

Furthermore, current recommendations from international organizations such as the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), EEA (European Environment Agency), and others encourage farmers to select cultivars adapted to the climatic conditions of their growing areas to better adjust agricultural systems to the challenges posed by climate change. This approach enhances yield stability, resilience to environmental stress, and resource-use efficiency. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate both varieties adapted to regional conditions and locally developed varieties whose genetic and physiological characteristics are intrinsically suited to the agroclimatic conditions of the selected area [36,37,38,39].

Sweet corn cultivation has increased significantly across Europe, driven by growing consumer demand for fresh, high-quality products and the introduction of resilient cultivars adapted to diverse climatic conditions [40,41]. However, its cultivation requires high levels of nutrients, as shown by various studies, with chemical fertilization generally being used [42,43]. In 2019, the European Commission introduced the European Green Deal (EGD) to promote sustainability, clean energy, and biodiversity. This initiative includes the Farm to Fork strategy, which aims to reduce pesticide use by 50% and chemical fertilizer use by 20% [44]. As a result, efforts are currently focused on finding optimal crop fertilization options that comply with European standards. Thus, the growing popularity of sustainable farming methods in Romania reflects current global trends, as consumers and farmers have become increasingly aware of the health and environmental benefits associated with organic products [45].

Despite the increasing interest in sustainable fertilization systems, limited information is available on the combined effects of genotype and fertilization strategy on the nutritional quality and productivity of sweet corn under Eastern European pedoclimatic conditions. In particular, comparative data regarding locally adapted genotypes under organic and chemical fertilization are scarce. For example, in Romania, Royalty F1 and Hardy F1 are commercial sweet corn hybrids frequently cultivated, whereas Deliciosul de Bacău is a locally adapted genotype traditionally grown.

Given the above considerations, to enhance the sustainability of sweet corn production in Eastern Europe, this study examined the morphology, physiology, and nutritional quality of three genotypes (Royalty F1, Hardy F1, and Deliciosul de Bacau) adapted to Romanian climatic conditions.

This research evaluated the effects of genotype and fertilization regime (chemical and organic fertilizers), individually and in interaction, on key traits associated with sweet corn development and quality. Additionally, comprehensive statistical analyses were conducted to identify and establish interdependencies among agro-morphological, physiological, and quality traits. Consequently, the findings contribute to the optimization of sweet corn production in both conventional and organic farming systems while highlighting the influence of cultivation practices on the crop’s nutritional composition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Experimental Conditions

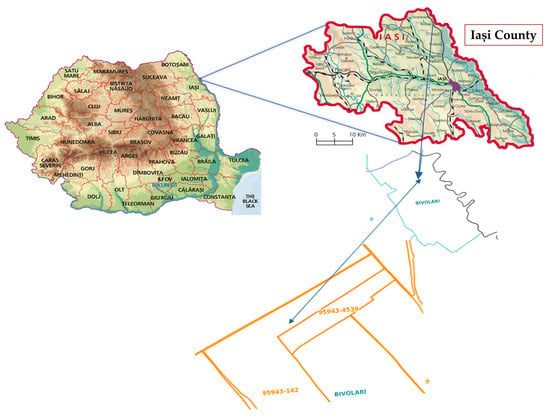

This research was carried out in an open field at the Semtop Farm experimental station, spanning 8600 m2 (47°34′34″ N, 27°22′24″ E, 152 m elevation), from 2022 to 2023 (Figure 1). The soil of the experimental field was classified as cambic chernozem and presented adequate characteristics for efficient nutrient absorption and optimal plant development [46]: pH of 7.10, electrical conductivity (EC) of 497 µS/cm, CaCO3 content of 0.64%, organic matter (OM) content of 2.98%, total nitrogen (N) content of 2.95 g/kg, phosphorus (P) content of 54.28 mg/kg, potassium (K) content of 287 mg/kg, sodium (Na) content of 49.23 mg/kg, sulphur (S) content of 17.89 mg/kg, and zinc (Zn) content of 0.28 mg/kg. Soil samples were collected before sowing from the 0–30 cm soil layer.

Figure 1.

Localization of experimental site in Romania.

The data presented in Table 1 indicate that during the vegetation period (April–August), the average temperature ranged from 11.5 °C in April to 33.6 °C in August, as the means of the two research years; precipitation levels differed between 2022 (220 mm) and 2023 (280 mm).

Table 1.

Climatic conditions in 2022–2023.

2.2. Biological Material and Experimental Design

The experimental protocol was based on the factorial combination between three varieties (Royalty F1, Hardy F1 and Deliciosul de Bacau—DBc) and two fertilization types (organic and conventional), plus an untreated control. The experiment was conducted as a split-plot design arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replications. Each replicate covered an area of 900 m2. Plant spacing within the row was 40 cm, with 70 cm between rows, resulting in a planting density of 35,700 plants/ha.

The sweet corn varieties used in this study were selected not only for their adaptation to local climate conditions but also for their variability in biochemical composition and different reactions to agricultural practices. Owing to the climatic conditions in the experimental years, two irrigations were applied by sprinkling with a total volume of 250 m3/ha.

The experiment investigated fertilization as a main factor with three levels: (i) control (no fertilizer application), (ii) organic fertilization, and (iii) chemical fertilization. The control treatment did not receive any organic or chemical fertilizers during the growing season, serving as a baseline to assess genotype responses to different fertilization methods. The doses of fertilizers were calculated by taking into account the following: the chemical composition of each formulate; that 60% of nitrogen (N), phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), and potassium oxide (K2O) contents of the organic fertilizer is available for plant assimilation in the year of application; and that 15% of nitrogen leaching is expected upon the chemical fertilizer supply, as the rate of nutrient release is much lower compared to simple nitrate fertilizers [13,47]. All fertilizer doses are expressed in kg/ha or L/ha, while nutrient concentrations are reported as % w/w or mg/L, according to the manufacturers’ specifications.

In the case of organic fertilization, products such as Naturcomplet G (400 kg/ha, produced by Daymsa, Zaragoza, Spain), and Pleniflor (3 L/ha, with 9% boron, 1% molybdenum and algae extract—Ascophyllum nodosum produced by Daymsa, Zaragoza, Spain) were supplied for stimulating soil health and accumulating essential nutrients naturally [48,49]. Naturcomplet G is a certified organic soil improver containing 1.5% N, 5% K2O, 35% organic matter (OM), 30% humic acids, and 5% fulvic acids. Iron content (Fe) is 1%, the carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio is 20.3, and the electrical conductivity (EC) is 2.5 dS/m. Approximately one month before crop establishment, 1000 kg/ha of chicken manure (4% organic N, 4% P, 4% water-soluble K, 72% OM) was applied to the plots designated for organic fertilization as a basal fertilizer. In particular, the organic fertilizer was supplied before sowing to allow for the onset of the nitrification process, thus preventing the initial ammonium accumulation that may cause toxicity and enhancing the total nitrate amount released to plants over the entire crop cycle [47]. During the growing season, two additional root fertilizations were performed using granulated chicken manure at a rate of 400 kg/ha per application: the first application at 8–10 leaves (BBCH 19) and the second at stem elongation (BBCH 71).

The chemical fertilization consisted of NPK (200 kg/ha: 16% N, 16% P2O5, 16% K2O produced by Azomureș SA, Târgu Mureș, Romania) during soil preparation and supplemented with KSC I (100 kg/ha: 14% N, 40% P2O5, 5% K2O, produced by Timac Agro, Orcoyen, Navarra, Spain) in two rounds at the BBCH 19 and BBCH 71 stages, during the vegetation period on the ground. Cropmax (2 L/ha, with 0.2% N, 0.4% P, 0.02% K, 220 mg/L Fe, 550 mg/L Mg, 70 mg/L B, 49 mg/L Zn, 54 mg/L Mn, 35 mg/L Cu, 10 mg/L Ca, 10 mg/L Mo, 10 mg/L Co, 10 mg/L Ni and amino acids, vitamins, and plant hormones like auxin, cytokinin, and gibberellin, produced by Holland Farming B.V., Groenekan, The Netherlands) was applied foliar and provides a quick supply of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, essential for rapid plant growth [50,51].

2.3. Chlorophyll Content in Leaves

The chlorophyll content was determined at the BBCH 73 growth stage. Measurements were performed on the basal leaf located immediately below the first ear. Chlorophyll readings were taken using the portable CCM 200plus device (Opti-Sciences, ADC BioScientific Ltd., Birmingham, UK) in the middle portion of the leaf blade, avoiding the main vein. The readings are expressed as a chlorophyll content index (CCI, unitless).

2.4. Harvesting and Sample Preparation

Sweet corn samples were harvested at commercial maturity, stage 73–75 according to the BBCH scale, thus ensuring the consistency of the data obtained [52]. After harvesting, the samples were lyophilized via an ECO EVO freeze-dryer (Tred Technology S.R.L., Ripalimosani, Italy), which preserved the bioactive compounds and prevented their degradation. Then, each freeze-dried sample was ground and stored at −80 °C until subsequent biochemical analyses were performed [53].

2.5. Analytical Methods

The antioxidant activity was evaluated via two methods, the ABTS test and the DPPH test, according to the methods of Ordóñez-Díaz et al. [53]. ABTS measures the antioxidant capacity by reducing free radicals, and the values are expressed in Trolox equivalents (TE). In the DPPH test, the capacity of the samples to neutralize free radicals was similarly expressed in μmol TE per g dry weight (dw) [54].

The total polyphenol content was determined via the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent according to the methods described by Slinkard and Singleton [55]. This measurement allowed for the quantification of polyols by spectrophotometric absorption at 765 nm, with the result being expressed in mg Gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per g dry weight (dw) [54].

2.6. Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Pigments in Kernels

Chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments were determined from dry biomass using spectrophotometric methods as described by Nagata and Yamashita [56]. The contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, lycopene, and β-carotene were determined by measuring the absorbance at wavelengths specific to each pigment. The results were expressed in mg per 100 g dry weight (dw).

2.7. Sugar Analysis in Kernels

Sweet corn samples were extracted following the method described by Moreno-Ortega et al. [54]. A total of 0.5 g of the sample was mixed with 1 mL of a 20:80 (v/v) ethanol/deionized water solution and homogenized for 2 min, followed by sonication and centrifugation. The process was repeated twice using the residue. The supernatants were then frozen at −80 °C until analysis. The identification and quantification of glucose, fructose, and sucrose in the sweet corn samples were performed using an HPLC-RID system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a 250 × 4.6 mm i.d. Luna 5 μm NH2 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Sugars were identified by comparing their retention times with those of pure reference standards, and quantification was achieved via calibration curves for fructose (0.3–50.0 mg/mL), glucose, and sucrose (0.3–10.0 mg/mL).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained were statistically analyzed via one-way ANOVA, upon checking their normality and the homogeneity of variance by the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s test, respectively, and mean separation was performed using Duncan’s test at p ≤ 0.05, using the SPSS v26 software package (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The data presented represent the mean values of the two experimental years.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the quality dynamics of sweet corn cultivars under the different fertilizers, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Pearson’s correlation analysis were applied using the free trial of OriginPro 2024b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). These methods enable an in-depth examination of patterns and relationships within the data from multiple perspectives and provide a robust framework for analyzing and interpreting the complex interactions in sweet corn quality under varied fertilization systems [57].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Cultivar and Fertilization Regime on Yield and Quality Characteristics

3.1.1. Influence of Cultivar and Fertilization Regime on Morphological, Physiological Parameters and Yield Parameters

The main effects of variety and fertilization regime on yield, biometrical, biochemical and quality parameters of sweet corn are presented in Table 2. The data revealed no significant effect of cultivar on the chlorophyll content index, number of stalks, or number of ears per plant. These findings suggest that the F1 hybrids developed in the USA adapt well to Romanian production conditions, regardless of the year of cultivation. However, plant height and ear insertion on the plant significantly differed between cultivars, with a positive correlation between these two factors. The tallest plants and the greatest number of ear insertions were observed in the local cultivar DBc. Concerning ear weight, the hybrid cultivars, especially the Hardy F1 cultivar, demonstrated superior performance, with an increase of 24.4% compared with DBc. Similarly, for the number of kernel rows per ear, Hardy F1 also outperformed the other methods, with statistically significant differences noted at p ≤ 0.05.

Table 2.

Effects of sweet corn variety and fertilization type on morphological and physiological parameters.

The morphological indicators examined, such as plant height, ear insertion, number of stalks, and ear weight, showed no significant differences between the fertilization treatments.

The highest chlorophyll content index in leaves was recorded under chemical fertilization, followed by organic nutrition, with an increase of 16.4% compared with that of the unfertilized control. Additionally, the lowest average number of kernel rows was observed in the control group, with an 11.9% difference compared with the chemically fertilized treatment.

The results regarding the influence of sweet corn variety and fertilization regime on production parameters are presented in Table 3. Cultivar did not significantly affect rachis weight, dry matter, or humidity, regardless of genotype or cultivation year. Data of ear length indicate better stability for hybrid cultivars, greater kernel weight, and significantly increased production. For example, the difference in kernel weight ranged from 95.9 g to 146.6 g, representing an increase by 52.9% of the highest value compared to the lowest. The yield values varied widely, from 7628 kg/ha for DBc to 13,995 kg/ha for Hardy F1 (+82.2%).

Table 3.

Effects of sweet corn variety and fertilization type on yield parameters.

These results emphasize the good performance of Hardy F1, which demonstrated significantly lower production costs and higher efficiency due to its biological value. Furthermore, this study confirms that morphological parameters, including rachis weight, kernel weight, ear length, and yield capacity, are primarily determined by the plant genotype. These characteristics are inherited through the genetic makeup of the cultivar and are less influenced by external factors such as environmental conditions or cultivation practices. Similar findings have been reported in studies conducted by Islam et al. [58], Mahato et al. [59], Subaedah et al. [60], and Niji et al. [61].

With respect to the effects of fertilization on production indicators, no statistically significant differences were observed for most indicators, except for yield, which was increased by 57.6% by the chemical fertilization compared to the untreated control, with statistically significant differences also between chemical and organic fertilization.

Multiple studies have highlighted the evident positive effects of chemical fertilization on the morphological parameters of sweet corn compared to organic and biological fertilization. For instance, Laskari et al. [42] reported that chemical fertilization stimulated plant height, leaf area index, leaf greenness index (SPAD) and silage yield more in the Pioneer 1291 and Dekalb 6777 maize hybrids compared to the cattle manure. Similarly, chemical fertilization led to greater improvements in plant height, number of leaves per plant, leaf area, stem diameter, plant biomass, and chlorophyll content index in Zea mays var. saccharata L. compared to poultry manure [62]. According to Jiang et al. [63], the notable positive effect of chemical fertilization on the biometrical and physiological parameters of sweet corn, compared to organic fertilization, is primarily due to the immediate availability of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in chemical fertilizers. The organic fertilizers must first be transformed and decomposed before they can be absorbed by plants. Therefore, as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are essential for the healthy growth and development of plants, their availability in relation to the plant’s immediate needs is a crucial factor for maintaining the optimal growth, productivity, and overall plant status. Nitrogen is particularly effective in promoting cell elongation and division, leading to taller plants and stronger stems, while also playing a direct role in chlorophyll synthesis, which is vital for photosynthesis and biomass production [64]. Phosphorus is essential for enhancing root growth and branching, improving plant anchorage and nutrient uptake. A phosphorus deficiency can hinder the absorption of critical nutrients like nitrogen, potassium, and calcium, leading to shorter, thicker stems instead of elongated ones [63]. Additionally, phosphorus and potassium are crucial for energy transfer and the movement of carbohydrates during the grain-filling process [65].

3.1.2. Influence of Cultivar and Fertilization Regime on Quality Characteristics

The effects of the sweet corn cultivar and fertilization regime on the antioxidant capacity, TPC, chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments, and tannins are shown in Table 4. Data on the influence of cultivar on antioxidant capacity and chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments highlight differences between the three varieties used. The data indicate the absence of β-carotene and statistically insignificant differences in antioxidant capacity between the varieties, regardless of the method used.

Table 4.

Effects of sweet corn variety and fertilization type on antioxidant compounds, chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments, and tannins.

The highest content of TPC was recorded in Hardy F1, with a 24.7% difference compared with that in Royalty F1.

Concerning chlorophyll pigments, a higher content of chlorophyll b than a was observed in all varieties, by up to 60%. For the two pigments, a higher content was noted in DBc, attributed to its better adaptation to environmental conditions as a local cultivar. Lycopene content fluctuated depending on the variety, with higher levels recorded in the Royalty F1 and DBc groups, by up to 118%. Tannin content also differed between varieties, with the highest levels found in Hardy F1 compared with the other two genotypes.

The β-carotene content was under the detectable threshold corresponding to the fertilization treatments and no significant effect was observed on the TPC either. Antioxidant activity, as determined by both methods, was greater in the fertilized samples than in the control samples, like the chlorophyll pigment content in the kernels. The lycopene content varied widely, ranging from 1.35 mg/100 g d.w. in the unfertilized control to 2.16 mg/100 g d.w. in the organically fertilized (+60%). Additionally, the tannin content was up to 67% greater in both fertilized treatments compared to the control.

The obtained concentration of β-carotene below the detection limit was also found by Păcurar et al. [66] in Estival and Deliciul Verii sweet corn hybrids. In contrast, hybrids like Prima, Jubilee, and Delicios showed detectable β-carotene levels ranging from 0.21 to 1.00 µg/100 g. Song et al. [67] investigated the carotenoid composition of two sweet corn varieties, “Jingtian 3” and “Jingtian 5”, revealing that the predominant carotenoids were represented by lutein (ranging from 4.70 to 9.80 μg/g d.w.), zeaxanthin (0.83 to 10.86 μg/g d.w.), and all-trans-α-cryptoxanthin (1.8 to 6.4 μg/g d.w.). In comparison, β-carotene, expressed as all-trans-β-carotene, was found in lower concentrations, ranging from 0.12 μg/g d.w. to 0.71 μg/g d.w., which highlights that genetics plays a significant role in determining the nutritional profile of crops.

Although β-carotene was below the detection limit in the kernels of the analyzed sweet corn varieties, lycopene, which is a lipophilic carotenoid compound, was detected in relatively high concentrations, if compared with the levels found in lycopene-rich food such as tomato, guavas, bell peppers, grapefruit, and apricots [32,33,68]. For instance, Rusu et al. [33] reported contents of 9.0 and 10.2 mg/100 g d.w. of lycopene in Cristal and Siriana tomato cultivars, while Pavlović et al. [69] reported a content between 4.2 and 6.1 mg/100 g in dried tomato samples.

The obtained concentrations of TPC in the tested sweet corn varieties are consistent with previous findings. Ledenčan et al. [70] reported values ranging from 1.59 mg GAE/g d.w. to 2.86 mg GAE/g d.w. in five su1 sweet corn hybrids, while Cai et al. [71] recorded levels between 0.91 mg GAE/g d.w. and 1.58 mg GAE/g d.w. in corn grains from 23 cultivars. Zhang et al. [72] noted that the TPC content in fresh kernels of eight sweet corn varieties ranged from 38.01 mg GAE/100 g to 57.04 mg GAE/100 g, emphasizing the lower phenolic content in fresh biomass. Further supporting this, Das et al. [73] demonstrated that TPC levels in fresh biomass are not only lower but also influenced by the fertilization regime. Their study reported phenolic levels of 55.1 mg/100 g under vermicompost treatment, compared to 51.4 mg/100 g with chemical fertilization and 40.6 mg/100 g in the absence of fertilization. Furthermore, the study conducted by Hu et al. [74] revealed that phenolic content is higher in mature sweet corn stalks compared to those harvested at an earlier stage. For example, the YT16 sweet corn hybrid exhibited a phenolic content of 74.7 mg GAE/100 g FW when harvested 10 days after pollination, which increased to 124.7 mg GAE/100 g FW when harvested 30 days after pollination.

The ABTS and DPPH values detected in the sweet corn varieties are consistent with the findings of Cai et al. [71] and Bae et al. [75], who also reported that ABTS values were higher than those of DPPH, aligning with the trend observed in this analysis. Furthermore, similar to our findings, Dragičević et al. [76] reported a higher DPPH radical scavenging activity in maize genotypes under chemical fertilization compared to organic and unfertilized regimes.

The content of tannins determined in the tested sweet corn varieties, compared to those reported by Feregrino-Pérez et al. [77] in Mexican native maize (1.16–4.99 mg/100 g) and by Elemosho et al. [78] in Striga-resistant yellow-orange maize hybrids (2.1–7.3%), is significantly lower. This lower tannin content makes the tested sweet corn varieties more enjoyable and versatile for both culinary and feed applications.

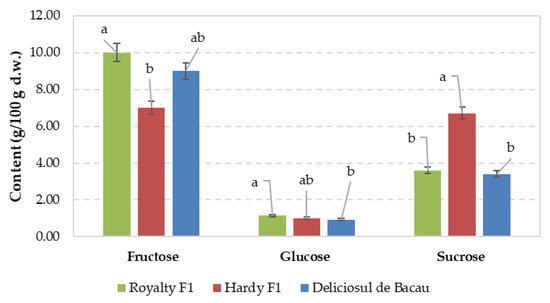

The effects of sweet corn cultivar and fertilization regime on sugar compounds are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The data concerning the influence of the cultivar on the sugars content and quality highlight differences between the three varieties used. The fructose content increased from 7.00 g/100 g d.w. in the Hardy F1 cultivar to 10.00 g/100 g d.w. in Royalty F1, which have the same genetic origin. This finding highlights the genetic characteristics of the fructose content of Royalty F1 compared with those of Hardy F1.

Figure 2.

Effect of sweet corn variety on sugar compounds. Values are means ± standard error (SE). Values associated with the same lower-case letters are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 according to Duncan’s test.

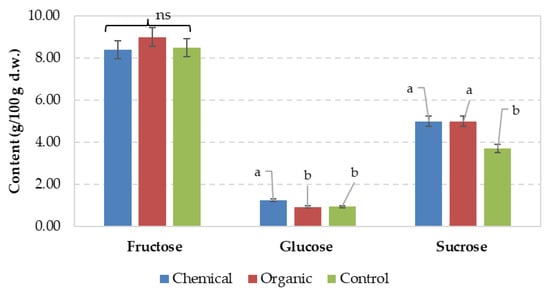

Figure 3.

Effect of fertilization type on sugar compounds. Values are means ± standard error (SE). Values associated with the same lower-case letters are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 according to Duncan’s testș; ns—not significant difference between means.

Small differences were recorded between the treatments referring to the glucose content, with the highest values for cultivar Royalty F1, whereas the latter and DBc hybrids showed up to 97% higher values of sucrose content than Hardy F1.

Considering the results obtained in this study, along with those reported by Ledenčan et al. [70], it can be concluded that the sugar content in sweet corn is influenced by genetics of the sweet corn variety. Furthermore, Ledenčan et al. [70] highlighted that the harvest date plays a significant role in determining sugar content. In corn harvested 17 days after pollination, the sugar content in the five su1 sweet corn hybrids tested ranged from 16.5 to 21.3 mg/g d.w. in 2018 and from 18.8 to 28.7 mg/g d.w. in 2019. In contrast, corn harvested 25 days after pollination had a sugar content ranging from 7.5 to 15.5 mg/g in 2018 and from 9.4 to 11.5 mg/g in 2019.

Both fructose and sucrose were positively influenced by organic fertilization (Figure 3), whereas the chemical treatment resulted in higher overall glucose and sucrose contents than the unfertilized control.

Das et al. [73] reported a total sugar content of 13.5% in the sweet corn control sample, closely aligning with the 13.1% recorded in our study. However, unlike our findings, i.e., 14.6% under chemical fertilization and 14.9% under organic fertilization, they detected the highest sugar content under chemical fertilization (19.56%), followed by a combination of 50% vermicompost and 50% Soligro (Ascophyllum nodosum) granular (19.33%), and vermicompost alone (15.13%). Ragheb [79] reported that the highest sugar content in sweet corn was observed under fertilization with chicken manure (10.29–10.85%), followed by cattle manure (8.80–9.05%) and mineral fertilizer (7.30–7.80%).

3.2. Interactions Between Variety and Fertilization Regime on Yield, Biometrical, Biochemical and Quality of Sweet Corn

3.2.1. Interactions Between Variety and Fertilization Regime on Morphological, Physiological Parameters and Yield Parameters

The results of the interaction of sweet corn variety and fertilizer on biometrical and physiological parameters are presented in Table 5. In this respect, no significant differences were found regarding the number of stems per plant. The chlorophyll index values ranged from 30.3 in the unfertilized cultivar RoyaltyF1 to 39.9 under the chemically fertilized Hardy F1 hybrid, which is positively correlated with the number of ears per plant, ear weight and number of kernel rows per ear, and led to greater yield; no significant differences were recorded upon the organic fertilization. Plant height varied between 176.5 cm for organically fertilized Hardy F1 and 238.4 cm (+35.1%) for unfertilized Royalty. Rather high values of plant height were found in the unfertilized control, regardless of the cultivar, which indicates a stimulation of cell elongation to the detriment of reproduction in sweet corn plants, as confirmed by the negative correlation with the yield indicators. Ear insertion on the plant is an important characteristic, especially for harvesting, because it greatly facilitates the technological process. The lowest ear insertion was found in the cultivar Hardy regardless of fertilization, which highlights the genetic influence, with values varying between 51.6 cm and 64.9 cm, whereas the highest values, up to 96.2 cm, were recorded in the organically fertilized DBc.

Table 5.

Effects of sweet corn variety and fertilization type interactions on morphological and physiological parameters.

The lowest number of ears per plant (1.3) was generally recorded in Hardy and DBc without fertilization, whereas the highest (2.1, +61.5%) was observed in Hardy under chemical fertilization. Ear weight varied significantly depending on the cultivar and the fertilization regime. The average mean ear weight ranged from 171.2 g in the unfertilized control to 263.7 g (+54%) under fertilization in the hybrid Royalty. In the Hardy hybrid, significantly higher values were recorded in the unfertilized control, with a negative correlation with the number of ears per plant. The number of kernel rows per ear was significantly influenced by the two experimental factors, with differences up to 46.3%. The interaction between sweet corn variety and fertilization regime was significant on all yield parameters (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effects of the interaction of sweet corn variety and fertilization type on yield parameters.

The ear length varied between 19.1 cm for the cultivar DBc and 22.1 cm for Royalty under the chemical fertilization (+15.83%).

The rachis weight ranged from 78.4 g for the hybrid Royalty F1 to 106.4 g for Hardy F1 in the unfertilized plants. The weight of grains per ear is essential for productivity, as it significantly influences the final production, especially since these varieties are intended for fresh grain consumption at the milk-wax stage. The kernel weight ranged from 88.1 g per ear for the variety DBc to 161.2 g per ear for Royalty under chemical fertilization (+83%). Both parameters mentioned are primarily influenced by the genetic factor.

The yield varied greatly, from 6853 kg/ha for the unfertilized DBc to 17,510 kg/ha for the chemically fertilized Hardy F1 (+255%). The interaction between variety and fertilization regime was also significant on yield, with the hybrid Royalty showing differences by 86.6% between chemical fertilization and the control and 61.2% between chemical and organic fertilization.

The dry matter content of sweet corn kernels varied significantly, from 19.4% in the organically fertilized Hardy F1 to 30.2% in chemically fertilized RUE. Interestingly, the unfertilized Hardy F1 also reached a high dry matter content of 30.0%. Notably, in Royalty and DBc, chemical fertilization elicited a higher dry matter content than the organic one, which is not common with most species.

3.2.2. Interactions Between Variety and Fertilization Regime on Quality Characteristics

The interaction between sweet corn variety and fertilization regime was significant on the antioxidant activity and pigment content (Table 7). In this respect, the total content of polyphenolic compounds varied from 1.37 mg/g in the unfertilized control to 2.88 mg/g in the chemically fertilized hybrid Hardy F1. Significant differences in the TPC were observed between all the cultivars, depending on the type of fertilization applied.

Table 7.

Effects of the interaction of variety and fertilization type on the contents of antioxidant compounds, chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments and tannins.

Antioxidant activity was measured using two methods, ABTS and DPPH. In the case of ABTS, no significant interactions were recorded, with the values varying from 1.45 μM TE/g dw in the organically fertilized to 1.93 μM TE/g dw in the chemically fertilized DBc (+33.1%); higher average values were recorded for both chemically fertilized hybrids. The antioxidant capacity determined by DPPH ranged from 0.98 μM TE/g dw for unfertilized Hardy F1 to 1.67 μM TE/g dw for chemically fertilized Royalty F1.

Chlorophyll a varied from 1.3 mg/100 g d.w. for the hybrid Hardy F1 to 7.6 mg/100 g d.w. for Royalty under organic fertilization, whereas the highest value for DBc was recorded in the two years with chemical fertilization (5.5 mg/100 g d.w.).

The lowest value of chlorophyll b (2.0 mg/100 g d.w.) was recorded for Hardy F1 and the highest for Royalty under organic fertilization, whereas DBc showed the highest values with chemical fertilization (8.7 mg/100 g d.w.).

The effects of the interactions between the two experimental factors resulted in the variation in lycopene from 0.56 mg/100 g d.w. in Hardy F1 to 3.96 mg/100 g dw in Royalty with organic fertilization, with significant differences compared to the other treatments.

The tannin content increased from 0.075 mg CE/100 g d.w. in the unfertilized Royalty cultivar to 0.225 mg CE/100 g d.w. in the organically fertilized Hardy.

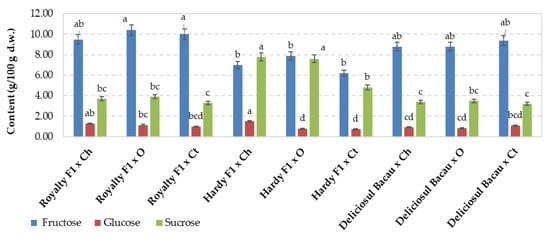

The effects of the interaction between sweet corn variety and fertilization regime on sugar contents are shown in Figure 4. The latter parameter varied from 11.7% in the case of the unfertilized cultivar Hardy F1 to 16.3% (+39.1%) for the same organically fertilized variety. In hybrid Royalty, organic fertilization resulted in an increase in the total sugar content by up to 15.5%, compared with that of the unfertilized variety. In the local variety DBc, no significant differences were found compared with the other two variants. In terms of sugar quality, the highest values were found for fructose, ranging from 6.20 g/100 g d.w. for the unfertilized Hardy F1 to 10.4 g/100 g d.w. for the organically fertilized Hardy F1. Large differences in sucrose were found between the experimental treatments, varying between 3.20 g/100 g d.w. in the unfertilized DBc and 7.9 g/100 g d.w. in the organically fertilized Hardy F1; no significant differences were detected between Royalty and DBc, regardless of fertilization.

Figure 4.

Effect of sweet corn variety and fertilization type on sugar compounds. Values are means ± standard error (SE). Ch—chemical, O—organic; Ct—control. Values associated with the same lower-case letters are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 according to Duncan’s test.

Among sugars, glucose presented the lowest values, varying between 0.73 g/100 g d.w. in the unfertilized hybrid Hardy F1 and 1.51 g/100 g d.w. in the same chemically fertilized hybrid; in the case of the Royalty hybrid, the chemical fertilization resulted in higher values of glucose content. We can state that organic fertilization favored fructose, whereas chemical fertilization resulted in a higher content of glucose content. No significant effects of fertilization were recorded on sucrose, regardless of the cultivar.

The data obtained showed that DBc and Royalty F1 are two sweet corn varieties with significantly higher fructose content compared to glucose and sucrose, regardless of the fertilization regime, similarly to previous reports [70].

The higher accumulation of certain secondary metabolites under organic fertilization may be associated with mild nutrient-related stress conditions that stimulate plant defense metabolism.

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction and Exploratory Causal Statistical Analysis of Data

To comprehensively analyze the quality of sweet corn under different fertilization systems, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to simplify complex datasets related to the biochemical, physiological and productivity responses of sweet corn genotypes. In addition, Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to gain a deeper understanding of the relationships between different traits and to explore how these traits collectively respond to different fertilization strategies. PCA and Pearson’s correlation coefficient methods were used to analyze the entire dataset and specific subsets, which were distinguished by fertilization type and sweet corn genotype.

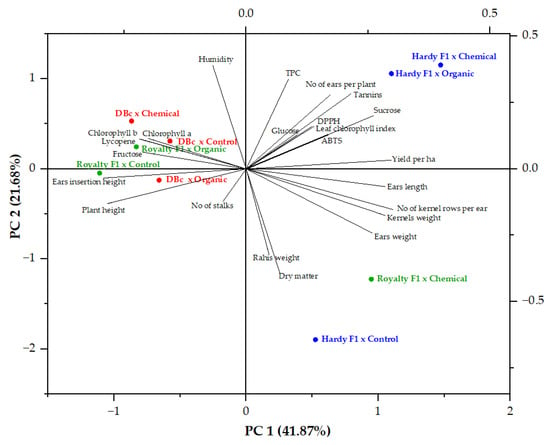

PCA was applied to the entire dataset (Figure 5), regardless of the fertilization type or sweet corn species, allowing for an overview of the relationships between variables and an identification of the principal components that explain most of the variability in the data. The results of this analysis revealed that out of the eight independent principal component axes identified, only six presented eigenvalues greater than 1, indicating that these six components are significant in explaining the dataset’s structure (Table S1). Together, these six components account for 93.83% of the total variability. However, PC1 and PC2 have the highest eigenvalues, 9.631 and 4.986, respectively, and explain 63.55% of the total variability, meaning that they capture most of the information contained in the dataset.

Figure 5.

Biplot of PCA applied to the entire dataset collected from the cultivation of the Royalty F1, Hardy F1, and Deliciosul de Bacau (DBc) sweet corn genotypes in organic, chemical, and unfertilized regimes.

The data presented in Table 8 highlight several significant positive contributors to PC1, with eigenvalues exceeding 0.2. These contributors include traits such as ear weight (0.2595), the number of kernel rows per ear (0.3007), ear length (0.2860), kernel weight (0.2858), yield per hectare (0.2981), tannins (0.2147), and sucrose content in kernels (0.2608). These traits are likely related to the productivity and nutritional quality of sweet corn, suggesting that PC1 may represent a dimension focused on these aspects. In contrast, the negative contributors to PC1 were plant height (−0.2857), ear insertion height (−0.2927), kernel chlorophyll a content (−0.2012), kernel chlorophyll b content (−0.2199), kernel lycopene content (−0.2153), and kernel fructose content (−0.2127). The negative loading values indicate that these traits vary inversely with the yield and quality traits represented by the positive contributors to PC1. This inverse relationship suggests that higher values of plant height and ear insertion height are associated with lower values of kernel yield and quality. For PC2, the significant positive contributors included the number of ears per plant (0.2790), moisture (0.3911), total phenolic content (TPC) (0.3378), tannins (0.2823), and sucrose (0.2000). In contrast, the most significant negative contributors to PC2 were ear weight (−0.2424), rachis weight (−0.3222), and dry matter (−0.3911).

Table 8.

Eigenvalues of the correlation matrix showing the affinity of different PCs against the yield, biometrical, biochemical and nutritional quality traits of the sweet corn genotypes under different fertilization systems.

The PCA biplot shows that the Hardy F1 × Organic treatment is positioned close to sucrose, tannins, and total phenolic content (TPC), suggesting an association with higher values of these traits. Hardy F1 × Chemical is located near yield per hectare and number of ears per plant, indicating its relationship with higher productivity. In contrast, Deliciosul de Bacău × Chemical is positioned close to kernel chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and lycopene, suggesting a stronger association with pigment accumulation.

Both Deliciosul de Bacău × Organic and Royalty F1 × Control are positioned on the left side of the plot and are closer to plant height and ear insertion height vectors, indicating an association with vegetative growth traits and a negative correlation with yield-related variables such as ear weight, kernel weight, and yield per hectare located on the positive side of PC1. Thus, PC1 differentiates treatments with high yield and improved kernel quality from those characterized mainly by vegetative growth and pigment accumulation. PC2 represents a moisture–phenolic metabolism axis, showing positive associations with moisture content, total phenolic content, tannins, sucrose, and number of ears per plant, and negative associations with ear weight, rachis weight, and dry matter. Therefore, PC2 separates treatments according to kernel moisture status and phenolic compound accumulation.

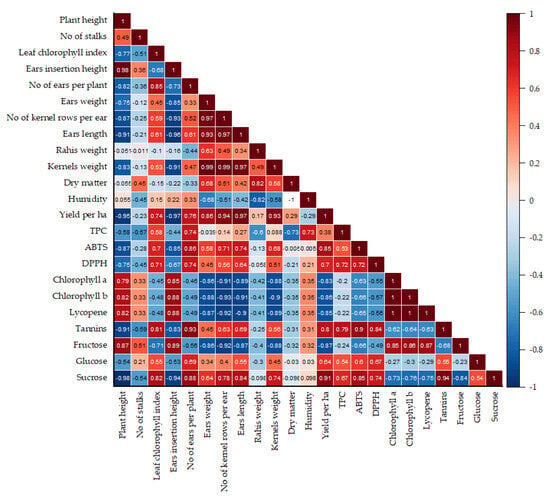

By integrating principal component analysis (PCA) with Pearson’s correlation analysis, our approach not only highlights the individual effects of genotype and fertilization type on sweet corn quality but also reveals interdependencies among agro-morphological, physiological, and nutritional traits. The data presented in Figure 6 indicate a strong positive correlation between plant height and ear insertion height, suggesting that as corn plant height increases, the position of the ear on the plant also increases proportionally.

Figure 6.

Pearson’s correlation diagram of the yield, biometrical, biochemical and nutritional quality traits of the Royalty F1, Hardy F1, and Deliciosul de Bacau sweet corn genotypes cultivated in organic, chemical, and unfertilized regimes.

This plot indicates a significant negative relationship between plant height growth and several key traits, including the leaf chlorophyll index (r = −0.77), number of ears per plant (r = −0.82), ear weight/length ratio (r = −0.75/−0.91), number of kernels per ear (r = −0.87), kernel weight (r = −0.83), and yield per hectare (r = −0.95). In addition, there were negative correlations with the total phenolic compound (TPC) content (r = −0.58), ABTS (r = −0.87), DPPH (r = −0.75), tannin (r = −0.91), glucose (r = −0.54), and sucrose content in the kernels (r = −0.98). These negative associations between plant height and these traits may arise from a trade-off in resource allocation. It is well established that taller plants tend to expend more energy and resources to maintain structural stability and reach greater heights, potentially limiting the nutrients and energy available for chlorophyll production, reproductive structures, and seed development. As a result, the lower levels of sugars, phenolic compounds, and antioxidants found in the kernels of taller plants could reflect a shift in focus away from kernel quality and nutrient storage, instead favoring structural and vegetative growth. Furthermore, a strong negative correlation was identified between ear insertion height and various factors, including the number of ears per plant, ear weight, and length, as well as the number of grains per ear, grain weight, and yield per hectare. This correlation also applies to the contents of TPC, ABTS, DPPH, tannins, glucose, and sucrose in the kernels (Figure 6). The correlations found between morphological parameters in this study were also reported by Stansluos et al. [80], who found a positive correlation between plant height and ear insertion height, and a negative correlation with the number of ears per plant/the yield.

Furthermore, plants with smaller ear sizes, lower ear weight-to-length ratios, and fewer rows of kernels per ear tended to present higher levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, lycopene, and fructose. Furthermore, the content of these compounds in the kernels is negatively correlated with the levels of TPC, ABTS, DPPH, tannins, and sucrose. However, TPC content and antioxidant activity, as measured by the ABTS and DPPH assays, show a positive correlation, a relationship also observed by Cruz et al. [81] in a super-sweet corn hybrid. Thus, the strong correlation is a natural consequence of the chemical properties of polyphenols and the assay mechanisms that directly measure their antioxidant potential [82]. A positive correlation between tannins content and ABTS scavenging activity was also established by Feregrino-Pérez et al. [77] in Mexican native maize. The positive correlation reflects the direct role of tannins as efficient radical scavengers due to their phenolic nature, which aligns well with the mechanism of the ABTS assay [83].

The PCA and Pearson’s correlation analysis of subsets of data distinguished by the fertilization system and sweet corn genotype highlighted several important associations. According to the data presented in Figure S1a, Royalty F1 has different associations depending on the fertilization method used. Under organic fertilization, Royalty F1 is associated with relatively high levels of lycopene, chlorophyll a and b, total phenolic content (TPC), and fructose. In contrast, when chemical fertilization is applied, F1 is associated with traits such as DPPH and ABTS antioxidant activity, the leaf chlorophyll index, dry matter content, kernel weight, ear weight, yield per hectare, and the number of kernel rows per ear. In the no-fertilization system, the Royalty F1 variety presented the greatest plant height, ear insertion height, and ear moisture levels. The Hardy F1 plants treated with chemical fertilizers presented relatively high levels of chlorophyll a and b, lycopene, leaf chlorophyll index, total phenolic content (TPC), DPPH antioxidant activity, glucose, ear length, yield per hectare, and number of ears per plant. In contrast, Hardy F1 plants grown via organic methods are more closely associated with higher levels of tannins, humidity, ABTS antioxidant capacity, and fructose. Additionally, the Hardy F1 plants grown under control conditions are positioned in the opposite quadrant of most of these traits, indicating that fewer traits are enhanced under these conditions than under organic or chemical fertilization (Figure S2a). Figure S3a reveals that Deliciosul de Bacau cultivated under organic fertilization is positioned positively along both PC1 and PC2, indicating associations with variables such as the number of kernel rows per ear, ear weight, and DPPH levels. Under chemical fertilization, Deliciosul de Bacau is positively positioned along PC1 but close to the origin of PC2, which is correlated with variables such as the number of stalks, tannins, and ABTS content. Under the control regime, Deliciosul de Bacau is closely associated with humidity, TPC, fructose, and glucose content.

Considering the effects of the cultivation system, the PCA results presented in Figures S4a, S5a, and S6a show that, under both the organic and chemical fertilization systems, the Hardy F1 variety had the greatest number of ears per plant. In the non-fertilized system, the Royalty F1 variety presented the greatest number of ears per plant. However, regardless of the fertilization system used for cultivating Hardy F1 sweet corn, the highest yield per ha was achieved. With respect to the nutritional quality of sweet corn kernels, the Hardy F1 variety presented the highest levels of tannins and TPC when grown with both chemical and organic fertilization. In contrast, the DBc genotype exhibited the highest values of tannins and TPC when grown without fertilization. The highest levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and lycopene in kernels were detected under chemical fertilization in DBc, whereas Royalty F1 presented the highest levels under organic fertilization and no fertilization.

The Pearson’s correlation diagrams presented in Figures S1b, S2b, and S3b show that the relationships between some of the considered traits depended on the sweet corn genotype. For example, plant height and the number of stalks are strongly positively correlated for Deliciosul de Bacau (r = 0.67) and Hardy F1 (r = 0.64), whereas for Royalty F1, the correlation between the two traits is very low (r = 0.031). Additionally, an increase in plant height has a strongly negative impact on the number of ears per plant and yield for the Royalty F1 and Hardy F1 genotypes. In contrast, for Deliciosul de Bacau, plant height was positively correlated with these traits. However, regardless of the sweet corn genotype, there was a significant negative correlation between plant height and ear length or a weak-to-strong positive correlation with chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and lycopene contents in kernels. The Pearson’s correlation diagrams presented in Figures S4b, S5b, and S6b indicate that, in the control and organic fertilization systems, plant height and the number of stalks are strongly positively correlated. In contrast, in the chemical fertilization system, a very low negative correlation was observed between these two traits (r = −0.035). Furthermore, the relationships between plant height and ear weight, the number of kernel rows per ear, ear length, kernel weight, and yield per hectare revealed strong negative correlations. Regardless of the sweet corn genotype, plant height was significantly positively correlated with the levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, lycopene, and fructose in the kernels. The results of the PCA and Pearson’s correlation analyses indicate that certain parameters analyzed in this study are predominantly influenced by genetic predisposition. This conclusion aligns with findings reported by Mesarović et al. [84], further emphasizing the role of genetics in determining key traits in sweet corn.

These genotype-dependent response patterns provide an important framework for interpreting fertilization efficiency under sustainable management conditions. In this context, the present findings are highly relevant to current European Union strategies promoting sustainable agriculture, including the Green Deal and Farm to Fork initiatives, which emphasize reduced synthetic fertilizer use and the adoption of environmentally friendly inputs. Our results demonstrate that genotype selection strongly modulates responses to fertilization systems, highlighting the need for breeding programs focused on genotypes adapted to low-input and organic farming systems under Eastern European pedoclimatic conditions. These findings support the development of integrated genotype–fertilization strategies to maintain productivity while improving nutritional quality under sustainable management practices.

4. Conclusions

Our findings highlight the significant influence of the Hardy F1 hybrid on yield and antioxidant capacity and the significant correlation between the contents of glucose and sucrose with chlorophyll. Notably, the local variety DBc, under chemical or organic fertilization, showed higher levels of chlorophyll pigments and lycopene, indicating better adaptation to climatic conditions, albeit with lower productivity. Furthermore, organically fertilized DBc was associated with increased plant height and ear insertion height, and showed a negative association with ear and grain weight.

The results of this study demonstrate that each sweet corn variety, depending on the intended end use of the grains, requires an appropriate fertilization strategy, thereby responding positively to both conventional and organic cultivation systems under comparable climatic conditions across the two research years. Based on the data presented, improvements in cultivar performance—in terms of yield, biometric, physiological, biochemical, and qualitative indicators—can be achieved by adopting suitable strategies for the production and management of sweet corn according to its intended use. Moreover, the data obtained, particularly with respect to the nutritional quality of corn grains, open new research perspectives that should also focus on carbohydrate content and quality under the influence of agronomic and environmental factors.

From a practical perspective, Hardy F1 is recommended for production systems aiming at high yield, particularly under chemical fertilization, and the local variety DBc is more suitable for low-input and organic farming systems focused on enhanced pigment accumulation and nutritional quality. These genotype–fertilization combinations provide practical guidance for selecting appropriate cultivation strategies according to specific production objectives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16030313/s1, Figure S1. (a) Bi-plot of PCA analysis and (b) Pearson’s correlation diagram of the agro-morphological, physiological and nutritional quality traits of the Royalty F1 cultivated in organic, chemical, and no-fertilization systems; Figure S2. (a) Bi-plot of PCA analysis and (b) Pearson’s correlation diagram of the agro-morphological, physiological and nutritional quality traits of the Hardy F1 cultivated in organic, chemical, and no-fertilization systems; Figure S3. (a) Bi-plot of PCA analysis and (b) Pearson’s correlation diagram of the agro-morphological, physiological and nutritional quality traits of the Deliciosul de Bacau cultivated in organic, chemical, and no-fertilization systems; Figure S4. (a) Bi-plot of PCA analysis and (b) Pearson’s correlation diagram of the agro-morphological, physiological and nutritional quality traits of the Royalty F1, Hardy F1, and Deliciosul de Bacau sweet corn genotypes cultivated in no-fertilization systems; Figure S5. (a) Bi-plot of PCA analysis and (b) Pearson’s correlation diagram of the agro-morphological, physiological and nutritional quality traits of the Royalty F1, Hardy F1, and Deliciosul de Bacau sweet corn genotypes cultivated in chemical fertilization systems; Figure S6. (a) Bi-plot of PCA analysis and (b) Pearson’s correlation diagram of the agro-morphological, physiological and nutritional quality traits of the Royalty F1, Hardy F1, and Deliciosul de Bacau sweet corn genotypes cultivated in organic fertilization systems; Table S1. Eigenvalues of the correlation matrix.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S. and P.-L.N.; methodology, P.-L.N., J.L.O.-D., M.S.-P., J.M.M.-R. and V.S.; validation, V.S., G.C., M.R., J.M.M.-R. and O.-R.R.; formal analysis, V.S. and M.R.; investigation, P.-L.N., G.R., S.M.A.E., J.L.O.-D., M.S.-P. and O.-R.R.; data curation, P.-L.N., V.S., O.-R.R., G.R., G.C. and J.M.M.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S., M.R., O.-R.R. and S.M.A.E.; writing—review and editing, V.S., J.M.M.-R. and M.R.; visualization, V.S., M.R. and O.-R.R.; supervision, J.M.M.-R. and V.S.; funding acquisition, V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The experimental field was provided by SC Semtop Groupe LTD, which also ensured crop maintenance throughout the growing season. Part of the laboratory analyses were supported by the “Ion Ionescu de la Brad” Iași University of Life Sciences through its PhD program, as well as by the Andalusian Institute of Agricultural and Fisheries Research and Training (IFAPA). During the preparation of this work, the authors used a generative AI tool to improve the readability and language of this manuscript. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Grain Production Worldwide by Type 2024/25, by type (in million metric tons)*. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263977/world-grain-production-by-type/?srsltid=AfmBOooal7aBJTuXX495-p2vDyNnNqdXcAYLkSh0DNRNnH1KvpGipVdq (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Tanumihardjo, S.A.; McCulley, L.; Roh, R.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Palacios-Rojas, N.; Gunaratna, N.S. Maize agro-food systems to ensure food and nutrition security in reference to the sustainable development goals. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 25, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global Maize production, consumption and trade: Trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, S.R.; Jat, S.L.; Mishra, P.; Darjee, S.; Saini, S.; Padhan, S.R.; Radheshyam; Ranjan, S. Corn for Biofuel: Status, Prospects and Implications. In New Prospects of Maize; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-83768-632-2. [Google Scholar]

- Soare, R.; Dinu, M. Effect of biofertilizers on quality of sweet corn. Sci. Papers. Ser. B Hortic. 2023, LXVII, 696–702. [Google Scholar]

- Sidahmed, H.; Vad, A.; Nagy, J. Advances in sweet corn (Zea mays L. Saccharata) research from 2010 to 2025: Genetics, agronomy, and sustainable production. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Gironés, S.; Masztalerz, K.; Lech, K.; Issa-Issa, H.; Figiel, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. Impact of osmotic dehydration and different drying methods on the texture and sensory characteristic of sweet corn kernels. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, A. The nutritional value and health benefits of sweet corn kernels (Zea mays ssp. Saccharata). Health Probl. Civiliz. 2023, 17, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, F.; Aydemir, S.K. Grain yield and nutritional values of sweet corn (Zea mays var. Saccharata) in produced with good agricultural practices. Nutr. Food Sci. Int. J. 2018, 7, 555710. Available online: https://juniperpublishers.com/nfsij/NFSIJ.MS.ID.555710.php (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Mishra, U.; Tyagi, S.; Gadag, R.; Elayaraja, K.; Pathak, H. Analysis of water soluble and insoluble polysaccharides in kernels of different corns (Zea mays L.). Curr. Sci. 2016, 111, 1522–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Sanchez, F.; Taylor, G. Reducing post-harvest losses and improving quality in sweet corn (Zea mays L.): Challenges and solutions for less food waste and improved food security. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whent, M.M.; Childs, H.D.; Cheang, S.E.; Jiang, J.; Luthria, D.L.; Bukowski, M.R.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Yu, L.; Pehrsson, P.R.; Wu, X. Effects of blanching, freezing and canning on the carbohydrates in sweet corn. Foods 2023, 12, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canatoy, R.C.; Daquiado, N.P. Fertilization influence on biomass yield and nutrient uptake of sweet corn in potentially hardsetting soil under no tillage. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, F.J.; Pradas, I.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.J.; Arroyo, F.T.; Perez-Romero, L.F.; Montenegro, J.C.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Effect of organic and conventional management on bio-functional quality of thirteen plum cultivars (Prunus salicina Lindl.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; Beatty, E.R.; Kingman, S.M.; Bingham, S.A.; Englyst, H.N. Digestion and Physiological properties of resistant starch in the human large bowel. Br. J. Nutr. 1996, 75, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Jhariya, A.N. Nutritional, medicinal and economical importance of corn: A mini review. Res. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 2, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dragomir, V.; Brumă, I.S.; Butu, A.; Petcu, V.; Tanasă, L.; Horhocea, D. An overview of global maize market compared to romanian production. Rom. Agric. Res. 2022, 39, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertek, A.; Kara, B. Yield and quality of sweet corn under deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Lutein and zeaxanthin and their roles in age-related macular degeneration—Neurodegenerative disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.; Grune, T. The contribution of β-carotene to vitamin A supply of humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.N.; Illes, A.; Bojtor, C.; Miar, Y.; Shojaie, S.H.; Nagy, J.; Szeles, A. Effect of harvest time on sugar content and carotenoid composition in different sweet maize hybrids. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, R.; Reboredo, F.; Guerra, M.; Ressurreição, S.; Alvarenga, N. Elemental composition and some nutritional parameters of sweet pepper from organic and conventional agriculture. Plants 2020, 9, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillioja, S.; Neal, A.L.; Tapsell, L.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Whole grains, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hypertension: Links to the aleurone preferred over indigestible fiber. BioFactors 2013, 39, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.-F.; Chang, Y.-T.; Lai, J.-M.; Chou, K.-L.; Tai, S.-F.; Tseng, K.-C.; Chow, C.-N.; Jeng, S.-L.; Huang, H.-J.; Chang, W.-C. Long-term effects of fertilizers with regional climate variability on yield trends of sweet corn. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, P.; Anibas, C.M.; Tracy, W.F. Sweet corn research around the world 2015–2020. Agronomy 2021, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, Z.; Khalil, S.; Iqbal, A.; Islam, B.; Shah, W.; Ahmad, A.; Arif, M.; Sajjad, M.; Shah, F. Growth attributes of sweet corn under different planting regimes. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2018, 27, 6945–6951. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.C.; Angelis-Pereira, M. Effect of Organic versus conventional agricultural systems on bioactive compounds of fruits and vegetables: An integrative review. Cad. Ciênc. Tecnol. 2022, 39, 27072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Gamage, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Kodikara, N.; Suraweera, P.; Merah, O. Role of organic farming for achieving sustainability in agriculture. Farming Syst. 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Jaafar, H.Z.E.; Karimi, E.; Ghasemzadeh, A. Impact of organic and inorganic fertilizers application on the phytochemical and antioxidant activity of Kacip Fatimah (Labisia pumila Benth). Molecules 2013, 18, 10973–10988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapałowska, A.; Jarecki, W. The Impact of using different types of compost on the growth and yield of corn. Sustainability 2024, 16, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, A.; Halim, R.A.; Ghasemzadeh, A.; Ramlan, M.F.; Sakimin, S.Z. Impact of organic and inorganic fertilizers on the yield and quality of silage corn intercropped with soybean. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, V.; Mangalagiu, I.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Teliban, G.-C.; Cojocaru, A.; Rusu, O.-R.; Burducea, M.; Mihalache, G.; Rosca, M.; Caruso, G.; et al. Enhancing the nutritional value of sweet pepper through sustainable fertilization management. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1264999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, O.-R.; Mangalagiu, I.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Teliban, G.-C.; Cojocaru, A.; Burducea, M.; Mihalache, G.; Roșca, M.; Caruso, G.; Sekara, A.; et al. Interaction effects of cultivars and nutrition on quality and yield of tomato. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Nadeem, M.; Ashiq, W.; Zaeem, M.; Gilani, S.S.M.; Rajabi-Khamseh, S.; Pham, T.H.; Kavanagh, V.; Thomas, R.; Cheema, M. The effects of organic and inorganic phosphorus amendments on the biochemical attributes and active microbial population of agriculture podzols following silage corn cultivation in boreal climate. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, P.; Thakur, N. Sustainable farming practices and soil health: A pathway to achieving sdgs and future prospects. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change Adaptation in the Agriculture Sector in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/cc-adaptation-agriculture (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- OECD. Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2023: Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change; Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-99827-8. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Climate Smart Agriculture Sourcebook. Available online: https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture-sourcebook (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Use of Adapted Crops and Varieties. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/adaptation-options/use-of-adapted-crops-and-varieties (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Hutuliac, R.; Precupeanu, C.; Vasilachi, I.C.; Cojocaru, A.; Rosca, M.; Stoleru, V. Response of sweet corn varieties to plant density and tiller removal: Preliminary studies. J. Appl. Life Sci. Environ. 2024, 57, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apahidean, A.I.; Hoza, G.; Dinu, M.; Soare, R.; Mitre, V.; Sima, R.; Buta, E.; Rózsa, S. Qualitative changes occurred at several sweet corn (Zea mays convar. Saccharata var. Rugosa) cultivars in different agrotechnical conditions. Acta Hortic. 2024, 1391, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskari, M.; Menexes, G.C.; Kalfas, I.; Gatzolis, I.; Dordas, C. Effects of fertilization on morphological and physiological characteristics and environmental cost of maize (Zea mays L.). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauziah, L.; Anggraeni, L.; Latifah, E.; Istiqomah, N.; Khamidah, A. Increased yield and quality of corn by inorganic fertilizers and utilization of corn as food to support food security. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1253, 012129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttinelli, R.; Zhu, X. Reducing chemical fertilisers under the European Union’s farm to fork strategy: Implications for Italian processing tomatoes. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 520, 146070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, T. Phytosterols in cereal by-products. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2005, 82, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Redondo, J.M.; Montenegro, J.C.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Using nitrogen stable isotopes to authenticate organically and conventionally grown vegetables: A new tracking framework. Agronomy 2022, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, V.; Munteanu, N.; Sellitto, V.M. New Approach of Organic Vegetable Systems; Aracne Publising House: Rome, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-548-7847-1. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Iglesias, L.; Puig, C.G.; Revilla, P.; Reigosa, M.J.; Pedrol, N. Faba bean as green manure for field weed control in maize. Weed Res. 2018, 58, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Rozo, J.; Galvis-López, J.; Manjarres, E.; Merchán-Castellanos, N. Biosolids as fertilizer in the tomato crop. Rev. Fac. Agron. Univ. Zulia 2022, 39, e223931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, A.E.; Slabu, C.; Covasa, M.M.; Motrescu, I.; Jitareanu, C.D. Comparative analysis of the influence of different biostimulators on the germination and sprouting behaviour of four wheat varieties. J. Appl. Life Sci. Environ. 2023, 55, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chețan, F.; Rusu, T.; Chețan, C.; Șimon, A.; Vălean, A.-M.; Ceclan, A.O.; Bărdaș, M.; Tărău, A. Application of unconventional tillage systems to maize cultivation and measures for rational use of agricultural lands. Land 2023, 12, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, M.; Smoleń, S.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Grzanka, D. Synthesis of organic iodine compounds in sweetcorn under the influence of exogenous foliar application of iodine and vanadium. Molecules 2022, 27, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Díaz, J.L.; Hervalejo, A.; Pereira-Caro, G.; Muñoz-Redondo, J.M.; Romero-Rodríguez, E.; Arenas-Arenas, F.J.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Effect of rootstock and harvesting period on the bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of two orange cultivars (‘Salustiana’ and ‘Sanguinelli’) widely used in juice industry. Processes 2020, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ortega, A.; Pereira-Caro, G.; Ordóñez, J.L.; Muñoz-Redondo, J.M.; Moreno-Rojas, R.; Pérez-Aparicio, J.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Changes in the antioxidant activity and metabolite profile of three onion varieties during the elaboration of ‘black onion’. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinkard, K.; Singleton, V.L. Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1977, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, M.; Yamashita, I. Simple method for simultaneous determination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 1992, 39, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, A.; Carbune, R.-V.; Teliban, G.-C.; Stan, T.; Mihalache, G.; Rosca, M.; Rusu, O.-R.; Butnariu, M.; Stoleru, V. Physiological, morphological and chemical changes in pea seeds under different storage conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ferdausi, A.; Sweety, A.Y.; Das, A.; Ferdoush, A.; Haque, M.A. Morphological characterization and genetic diversity analyses of plant traits contributed to grain yield in maize (Zea mays L.). J. Biosci. Agric. Res. 2020, 25, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, A.; Shahi, J.P.; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, M. Genetic Diversity of sweet corn inbreds using agro-morphological traits and microsatellite markers. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subaedah, S.; Edy, E.; Mariana, K. Growth, yield, and sugar content of different varieties of sweet corn and harvest time. Int. J. Agron. 2021, 2021, 8882140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niji, M.S.; Ravikesavan, R.; Ganesan, K.; Chitdeshwari, T. Genetic variability, heritability and character association studies in sweet corn (Zea mays L. Saccharata). Electron. J. Plant Breed. 2018, 9, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.O.; Al-Obaidy, K.S. Response of sweet corn (Zea mays Saccharata L.) to different levels of organic and inorganic fertilizer. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1252, 012065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Dong, C.; Bian, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of different fertilization practices on maize yield, soil nutrients, soil moisture, and water use efficiency in Northern China based on a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Yang, L.; Ahmad, S.; Farooq, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Khan, A.; Zeeshan, M.; Elshikh, M.S.; Abbasi, A.M.; Zhou, X.-B. Nitrogen fertilizer modulates plant growth, chlorophyll pigments and enzymatic activities under different irrigation regimes. Agronomy 2022, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Cheng, L. Phosphorus partitioning contribute to phosphorus use efficiency during grain filling in Zea mays. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1223532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păcurar, L.; Apahidean, M.; Has, V.; Apahidean, A. Morpho-productive and chemical composition of local and foreign sweet corn hybrids grown in the conditions of Transylvania Plateau. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca. Hortic. 2017, 74, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, D.; He, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Comparison of carotenoid composition in immature and mature grains of corn (Zea mays L.) varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.M.; Sevindik, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Nami, M.; Ozdemir, B.; Kaplan, D.N.; Selamoglu, Z.; Hasan, M.; Kumar, M.; Alshehri, M.M.; et al. Lycopene: Food sources, biological activities, and human health benefits. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2713511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, R.; Mladenović, J.; Pavlović, N.; Zdravković, M.; Josic, D.; Zdravković, J. Antioxidant nutritional quality and the effect of thermal treatments on selected processing tomato lines. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2017, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledenčan, T.; Horvat, D.; Marković, S.Š.; Svečnjak, Z.; Jambrović, A.; Šimić, D. Effect of harvest date on kernel quality and antioxidant activity in su1 sweet corn genotypes. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Mao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Huang, B.; He, Z.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Tang, M.; Chen, J. Carotenoid and phenolic compositions and antioxidant activity of 23 cultivars of corn grain and corn husk extract. Foods 2024, 13, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, L.; Deng, Y.; Chi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, M. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of eight representative sweet corn varieties grown in South China. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 3043–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Murmu, K.; Mitra, B.; Bandopadhyay, P.; Kundu, R.; Roy, M.; Alfarraj, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Brestic, M.; Hossain, A. Various organic nutrient sources in combinations with inorganic fertilizers influence the yield and quality of sweet corn (Zea mays L. Saccharata) in new alluvial soils of West Bengal, India. Phyton 2024, 93, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, G.; Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Guo, X.; Liu, R.H. Accumulation of Phenolics, antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of sweet corn (Zea mays L.) during Kernel Maturation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]