Abstract

Fertilization management is crucial mainly during the walnut training phase in order to obtain good plant formation, which is essential for guaranteeing future optimal yield. The aim of the present experiment was to evaluate the effect of different organic amendments on plant nutritional status and soil fertility in young bearing walnut trees. The experiment was conducted in 2023 and 2024 on walnut trees of the cultivar Chandler grafted on Juglans regia, planted in 2021. Since 2023, plants were yearly treated as follows: 1. non-fertilized control; 2. mineral fertilization; 3. application of municipal solid waste compost; and 4. application of compost from agri-food chain scraps. Soil amendments were supplied at the same rate as mineral fertilizer (120 kg N ha−1) in spring on the tree row on a 1.5 m wide strip, while mineral fertilizer was split in two applications (50% in spring and 50% in summer). Plant growth, measured with trunk diameter and pruning wood weight, was enhanced by mineral fertilization, followed by compost, in comparison to the control. Soil mineral N was too high in relation to plant needs, with a consequent increase in the risk of nitrate leaching. Organic amendments increased soil nutrient availability, microbial activity, and carbon concentration, which, in the long term, could provide a positive environmental effect related to its sequestration into the soil.

1. Introduction

Walnut (Juglans regia L.) is a commercially significant tree species, highly prized for the nutritional quality of its nuts [1] and its valuable timber. The top producing countries are China, the USA, and Chile [2]; Europe is in fourth place, with Italy cultivating 6130 ha [3], with an increasing trend [4] linked to the necessity of finding alternatives to traditional fruit species like peach and kiwifruit that are suffering from economic and pathological problems. In Italy, walnut is cultivated across the entire peninsula, from the Alps to Sicily, from sea level to 1000–1200 m elevation, and the species is well adapted to the range of environmental conditions characteristic of the country [5].

Walnut is a species with medium–high nutritional requirements, and the correct management of fertilization is essential both during the growing phase, in order to obtain good plant formation, and during the production phase, to ensure both high yields and good fruit quality during the adult phase.

The intensification of cultivation practices such as weeding, tillage, and excessive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides has resulted in various widely recognized negative environmental impacts such as degraded soil health, environmental pollution, decreased biodiversity and soil fertility, with organic matter (OM) often showing values below 2%. The supply of OM could be a possible solution for guaranteeing good plant nutritional status and, at the same time, restore soil fertility. Indeed, it is well known that the application of organic amendments improves physical, chemical, and biological properties of soils by increasing soil water retention, the concentration of organic carbon (C), microbial biomass, cation exchange capacity, and biological activities [6]. From a chemical point of view, OM has both a direct and indirect effect on the availability of nutrients for plant growth: Besides serving as a source of nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P), sulphur (S), and other macro- and micronutrients through its mineralization, OM has chelating properties that prevent the insolubilization of elements [6]. An optimal OM content, therefore, is the necessary prerequisite to ensure optimal plant development in the first years of cultivation and to manage production performance in the subsequent phases. In addition, OM supply is able to enhance soil microbial biodiversity and enzyme activity. Furthermore, the increase in humic substances affects several biochemical pathways in plants, such as increases in root growth [6] and hormone-like activity [7,8].

In this context, the increasing availability of organic waste from urban and agro-industrial origin represents an important source of material with fertilizing properties for agriculture. The composting of organic waste and the use of such amendments in cultivated soils would, on the one hand, activate virtuous mechanisms of the circular economy of the territory and, on the other hand, help the restoration of soil fertility and the saving of water resources due to the increase in OM in the soil. In addition, the use of organic matrices would reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and, in the long term, could become an effective action to fight against climate change through the sequestration of C in the soil [9]. The hypothesis underlying this experiment is that the supply of organic amendments is able to improve soil properties, resulting in fertilization effects similar to those of mineral fertilizers. The aim of the present experiment was thus to evaluate the effect of different types of organic amendments on plant nutritional status and soil fertility in a bearing walnut orchard.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Orchard Description and Treatments

The experiment was conducted in 2023 and 2024 on a commercial farm, named “Soc. Agr. Agro Noce”, located in the eastern part of the Po Valley in northeastern Italy (44°51′ N, 11°23′ E). Plants of the cultivar Chandler grafted onto Juglans regia rootstock were planted in the winter of 2020–2021, with a spacing of 5 m within the row and 7 m between rows, for a total of 286 plants ha−1. The soil is characterized by a clay-loam texture, alkaline pH (7.5–8), and high limestone content (active limestone > 7%). The climate in the area is temperate, with an annual precipitation of 664 mm (in the period 1961–2020) and an average temperature of 13.3 °C [10]. Soil management includes spontaneous grassing in the inter-row and mechanical weeding on the row, supplemented, when needed, by chemical weeding. Since 2023, the following treatments were compared, according to a randomized block design with 5 replications: (1) unfertilized control (CK); (2) mineral fertilization (MIN) at a rate of 120 kg N ha−1 supplied yearly in two stages (spring and early summer) using urea (N 46%); (3) municipal solid waste compost (MSW) at a rate of 120 kg N ha−1; and (4) compost from agri-food chain scraps (AFCS) at a rate of 120 kg N ha−1. The main properties of the two composts are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main physical and chemical properties of the amendments used during the experiment.

Theoretically, the quantity of N supplied with the amendment was the same as that of mineral fertilization, since it was calculated considering a mineralization coefficient (i.e., the annual percentage of mineralization of the total N in the soil conditioner) of 0.3 for MSW [11] and 0.4 for AFCS. Treatments were applied to an entire row over a soil strip approximately 1.5 m wide and buried in the soil profile corresponding to the first 20 cm. Along each row, five blocks of 10 plants each were created. The application of composts was made on 21 June 2023 and 5 May 2024, while mineral fertilization was split into two annual applications: on 21 June and 19 July in 2023 and on 17 May and 9 July in 2024.

2.2. Soil Sampling and Analysis

Soil was sampled in March 2023 (time 0) and monthly from June 2023 to assess biological and chemical parameters of soil fertility. The microbial component of the soil was assessed by sampling at a depth of 0.10 m. Samples were then sieved (2 mm mesh), and 30 g of fresh soil was then weighed, placed into a jar, and mixed with 0.2 g of glucose. Jars were then hermetically sealed to prevent any gas exchange with the atmosphere, and the CO2 produced by the system was measured after 3 h of incubation with an infrared gas analyzer (Inova 1302, Luma Sense Technologies A/S, Ballerup, Denmark). The concentration of CO2 was converted to microbial C according to the formula of Anderson and Domsch [12].

The mineral N fraction (Nmin), calculated as the sum of nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+) nitrogen, was measured on soil sampled in the profile between 0.10 and 0.40 m depth. For the determination of NO3−-N and NH4+-N, 10 g of fresh fine soil was mixed with 100 mL of 2 M potassium chloride solution and shaken for 1 h at 100 rpm; the solution was then decanted for 30 min, and the supernatant was frozen until analysis with a discrete automatic analyzer (Easychem Plus; Systea S.p.A., Anagni (FR), Italy).

Every other month, pH and available macronutrients were also determined on the same soil sample used for the mineral N analysis. Macronutrients in the soil solution were extracted as described for mineral N using ultrapure water as the extracting solution. The analyses were carried out with a plasma emission spectrometer (Ametek Spectro, Acros, Kleve, Germany). In addition, in the same soil solution, pH was measured with a pH meter (Titralab AT1102; HACH, Manchester, UK).

In March and September 2023, and in March, July, and September 2024, a sub-sample of the soil used for mineral analysis was dried to constant weight, sieved, and cleaned of visible plant residue, milled, and analyzed for total organic carbon (TOC) and total N by an elemental analyzer (Flash 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled with an isotopic ratio mass spectrometer (Delta V Advantage Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), after a pre-treatment with a few drops of 6 M HCl to eliminate the carbonates.

2.3. Plant Measurements, Organ Sampling, and Analysis

At the beginning of August of both years, leaf samples were taken from the middle part of shoots; only the terminal leaflet was used for analysis. Leaves were then washed, oven-dried, milled, and analyzed for the concentration of N, P, potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), S, boron (B), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and zinc (Zn). A sub-sample of 0.3 g was mineralized (US EPA Methods 3052; [13]) in an Ethos TC microwave lab station (Milestone, Bergamo, Italy) with a mixture of 8 mL of HNO3 (65%) and 2 mL of H2O2 (30%), and analyzed for macro- (P, K, Ca, Mg, S) and micronutrient (B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn) content by a plasma spectrometer (ICP-OES; Ametek Spectro, Arcos, Kleve, Germany). Nitrogen was measured by Schumann [14] by mineralizing 0.5 g of dry sample, with 8 mL of H2SO4 and one catalyst tablet (3.5 g K2SO4 + 0.5 g CuSO4 × 5H2O) at 420 °C with an infrared digestion unit (TURBOTHERM TTs, Gerhardt Gmbh&Co; Königswinter, Germany), followed by distillation with 32% (v/v) NaOH and automated titration with 0.05 M H2SO4 (95%) (Vapodest 450, Gerhardt Gmbh&Co; Königswinter, Germany).

Even though plants were still in the training phase, at the end of September 2024, some fruits (3–5 fruits plant−1) were harvested, and fresh weight was recorded. Fruits were then hulled (the green husk was removed) and dried for 24 h at 40°C to reach 7% moisture, and their weight was measured. A sample of dried kernel, husk, and shell was milled and analyzed for macro- and micronutrients as described above.

In March and December 2023 and in December 2024, the diameter of the trunk was measured at 20–25 cm from ground level, taking two orthogonal measurements. In February 2024 and February 2025, winter pruning was carried out, and the amount removed from each plant was weighed. A sub-sample of wood was then dried, ground, and used to determine macro- and micronutrient content.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Nutrient concentrations of leaves and pruned wood were statistically analyzed in a factorial experimental design with two factors: treatments (4 levels: CK, MIN, MSW, and AFCS) and sampling year (2023 and 2024).

All other data were analyzed in a complete randomized block design with 4 treatments (CK, MIN, MSW, and AFCS) and 5 replicates. Preliminary analyses indicated that replicate effects were not statistically significant; therefore, replicates were not included in the final model. When analysis of variance showed a statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) effect of treatment, the Student Newman–Keuls (SNK) test (P ≤ 0.05) was used to separate the means.

Data on microbial biomass and soil pH were analyzed using the R (version 4.4.3) statistical software (candisc package), according to canonical discriminant analysis (CDA). CDA is a dimension-reduction technique related to principal component analysis and canonical correlation and determines the best way to separate or discriminate two or more treatment groups, given quantitative measurements of different variables for each treatment [15].

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Treatments on Soil Biological and Chemical Fertility

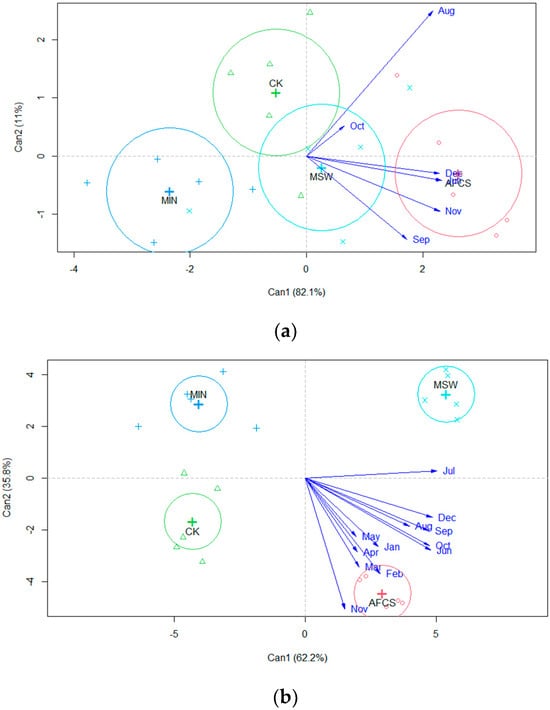

Soil microbial activity in both 2023 (Figure 1a) and 2024 (Figure 1b) was enhanced by the application of composts, with a more pronounced effect of AFCS on soil microbial activity than MSW (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Discriminant canonical analysis of soil microbial biomass in 2023 (a) and in 2024 (b). Data measured in March 2023 were not included since treatments were not yet applied.

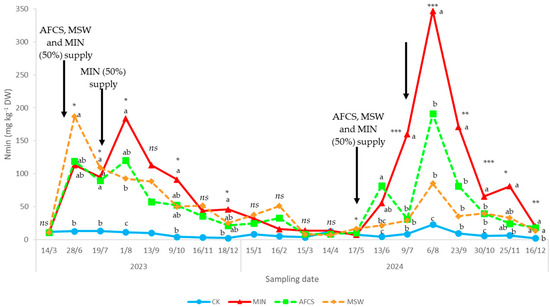

MIN and organics amendments supply in 2023 induced a sharp increase in mineral N availability that was higher than the control (Figure 2). On 19 July, all fertilization treatments induced an increase in mineral N availability in comparison to the control, while in August, October, and December, mineral fertilization induced a significant increase in mineral N in comparison to the control and AFCS (only in August). MSW and AFCS showed similar and intermediate values (Figure 2). In September and November 2023, no significant differences were observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of fertilization treatment (CK = unfertilized control; MIN = mineral fertilization; MSW = municipal solid waste compost; AFCS = compost from agri-food chain scraps) on mineral N availability during the experiment. ns, *, **, ***: effect not significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, 0.01, and P ≤ 0.001, respectively. Within the same date, values followed by the same letter are not statistically different according to the SNK test (P = 0.05).

From January to April 2024, no significant differences between treatments were observed (Figure 2). After the application of composts and 50% of mineral, a sharp increase in mineral N availability was measured, with MSW showing the highest values in June. From July until the end of October, MIN showed the highest values, while AFCS and MSW showed similar values higher than the control (Figure 2). In November, MIN showed higher values than the control, while MSW and AFCS showed intermediate values. In December, all fertilization treatments showed higher values than the control (Figure 2).

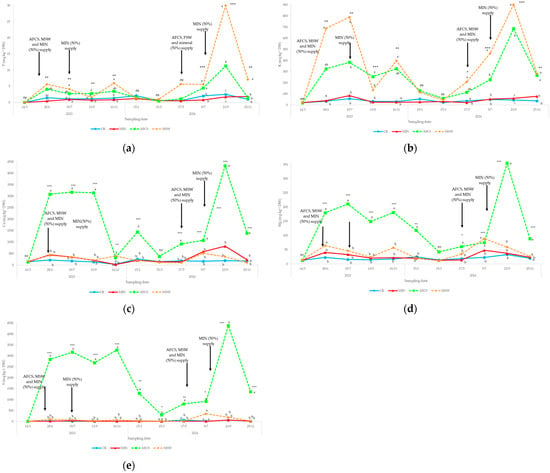

In 2023, P availability in the soil solution was increased by the supply of MSW in comparison to MIN and the control, while AFCS showed intermediate values not different from the other treatments. In 2024, with the exclusion of the first sampling dates, both composts enhanced P availability, with a more evident effect of MSW than AFCS (Figure 3a). Potassium soil availability was also higher in MSW than other treatments with AFCS, often showing values higher than mineral and the control (Figure 3b). Calcium (Figure 3c), Mg (Figure 3d), and S (Figure 3e) soil availability was increased, in both sampling years, by the application of AFCS.

Figure 3.

Effect of fertilization treatments (CK = unfertilized control; MIN = mineral fertilization; MSW = municipal solid waste compost; AFCS = compost from agri-food chain scraps) on P (a), K (b), Ca (c), Mg (d), and S (e) availability in soil solution in 2023 and 2024. ns, *, **, ***: effect not significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, 0.01, and P ≤ 0.001, respectively. Within the same date, values followed by the same letter are not statistically different according to the SNK test (P ≤ 0.05).

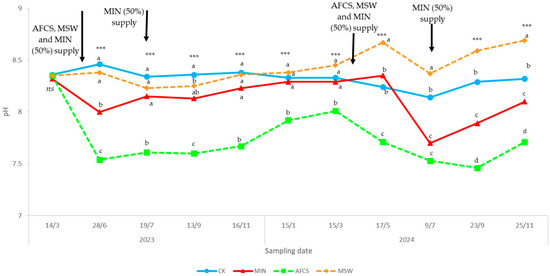

The supply of AFCS induced, during the entire experiment, the lowest soil pH values. MIN showed a pH lower than MSW and the control in June 2023 and in July, September, and November 2024; in the latter sampling date, MSW also showed values lower than the control (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of fertilization treatments (CK = unfertilized control; MIN = mineral fertilization; MSW = municipal solid waste compost; AFCS = compost from agri-food chain scraps) on soil pH in 2023 and 2024. ns, ***: effect not significant or significant at P ≤ 0.001, respectively. Within the same date, values followed by the same letter are not statistically different according to the SNK test (P ≤ 0.05).

In September 2023, three months after the first amendment supply, MSW induced a significant increase in total N and C in comparison to MIN and CK, while AFCS showed, for both elements, intermediate values not different from the other treatments (Figure 5). From March 2024, both amendments, induced a significant increase in soil total N (Figure 5a) and C, which, in July 2024, was significantly higher in MSW than in AFCS (Figure 5b). In September 2024, MIN and MSW showed significantly higher total C and N soil concentrations than AFCS and CK (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of fertilization treatments (CK = unfertilized control; MIN = mineral fertilization; MSW = municipal solid waste compost; AFCS = compost from agri-food chain scraps) on total N (a) and C (b) in 2023 and 2024. ns, *, **, ***: effect not significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, 0.01, and P ≤ 0.001, respectively. Within the same date, values followed by the same letter are not statistically different according to the SNK test (P ≤ 0.05).

3.2. Effect of Treatments on Plant Growth and Nutritional Status

In December 2023, plants fertilized with MIN and MSW showed higher trunk diameter than AFCS and the control. In December 2024, the highest values were measured in MIN plants (Table 2). Pruned wood in 2023 was higher in MIN than in all other treatments, while in 2024, MIN was significantly higher than the control, while the two composts had similar and intermediate values (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of fertilization treatment on trunk diameter and pruning wood weight during the experiment.

In Table 3 and Table 4, the effect of main factor is reported. Phosphorous concentration in the leaf was higher in the control than MIN and MSW, while K was higher in AFCS and the control than in MSW, while MIN showed intermediate values not different from the other treatments (Table 3). Magnesium concentration in the leaf was higher in MIN and MSW than in the other treatments, while S concentration was enhanced by MSW supply (Table 3). Nitrogen and Ca concentrations in the leaf were not significantly influenced by fertilization treatment. All nutrients, with the exception of Mg, showed higher concentrations in 2024 than in 2023 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of fertilization treatment and sampling year on leaf macronutrient concentration (g 100 g−1 DW).

Table 4.

Effect of fertilization treatment and sampling year on leaf micronutrient concentration (mg kg−1 DW).

Micronutrient concentrations in the leaf was not influenced by fertilization treatment; the only exception was Mn, which was higher in MIN than in AFCS and the control, while MSW showed intermediate values (Table 4). Copper concentration was higher in 2023 than in 2024, while the opposite was measured for Fe and Mn; B, Cu, and Zn were not significantly influenced by the sampling year (Table 4).

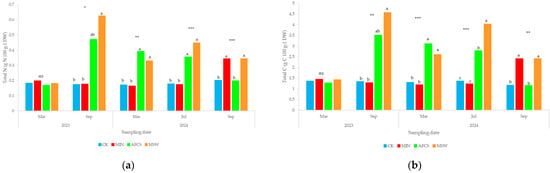

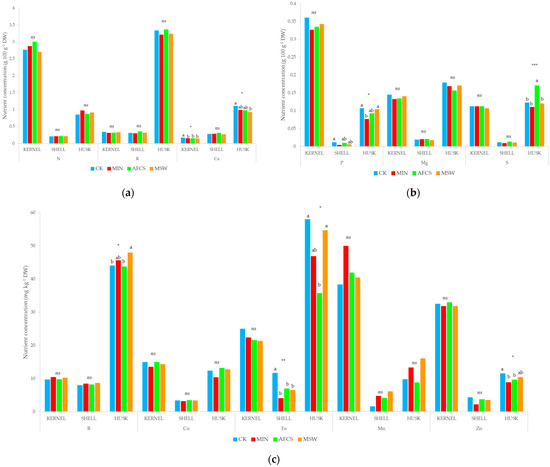

Nitrogen (Figure 6a) and P (Figure 6b) were mainly accumulated in the kernel, followed by the husk and the shell. While no significant differences between treatments were observed in organs’ N concentration, P concentration in the husk was higher in MSW and CK than MIN, while shell P was higher in CK than in MIN, with MSW and AFCS showing intermediate concentrations (Figure 6b). Potassium, Ca, and S were mainly accumulated in the husk, while smaller concentrations were measured in the kernel and the shell (Figure 6a,b). Potassium concentration in all fruit parts, as well as Ca in the shell and S in the kernel and the shell, was not influenced by fertilization treatment (Figure 6a,b). Calcium concentration in the husk was higher in CK than in MSW, with MIN and AFCS showing intermediate values; the concentration of this nutrient in the kernel was higher in CK than in all other treatments (Figure 6a). Sulfur concentration in the husk was higher in AFCS than in all other treatments, while no significant differences were observed in the kernel and shell S concentrations (Figure 6b). Magnesium concentration in the kernel and husk was almost similar, and in all fruit parts analyzed, no significant difference between treatments was observed (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Effect of fertilization treatments (CK = unfertilized control; MIN = mineral fertilization; MSW = municipal solid waste compost; AFCS = compost from agri-food chain scraps) on total kernel, shell, and husk concentrations of N, K, and Ca (a); P, Mg, and S (b); and B, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn (c) in 2024. ns, *, **, ***: effect not significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, 0.01, and P ≤ 0.001, respectively. For each nutrient, within the same fruit part, values followed by the same letter are not statistically different according to the SNK test (P ≤ 0.05).

Most of B was accumulated in husks, with a higher concentration in MSW than in AFCS and the CK; no significant differences between treatments were observed in the kernel and shell (Figure 6c). Copper concentration in the kernel and husk was almost similar, and no significant differences between treatments were observed in all fruit parts (Figure 6c). The husk accounted for the highest Fe concentration, which increased in MSW and CK in comparison to AFCS. Fe shell concentration was higher in CK than in all other treatments, while no significant differences were observed in Fe concentration in the kernel (Figure 6c). Manganese was mainly accumulated in the kernel, followed by the husk and the shell, with no significant differences between treatments (Figure 6c). The kernel showed the highest concentration of Zn, followed by the husk and the shell. While Zn concentration in the kernel and shell was not influenced by treatments, the concentration of this nutrient in the husk was higher in CK than in MIN, with MSW and AFCS showing intermediate values (Figure 6c).

Pruned wood accounted for low macro- and micronutrient concentration (Tables S1 and S2), which were, for some nutrients (N, Mg, S, Mn, and Zn) higher in 2024 than in 2023, with little influence of fertilization treatments (Tables S1 and S2).

4. Discussion

Unlike other fruit crops, walnut requires large amounts of energy to produce nuts and maintain normal growth; therefore, a healthy soil environment and good soil fertility are crucial for walnut trees. The supply of amendments has positively affected soil microbial biomass, which increased shortly after application according to a well-known mechanism [16]. Similar results were observed both in the long- [17] and short-term [18], indicating the beneficial effect of organic matter addition on soil quality [19]. In an experiment on walnut, after one year, a strong correlation was observed between the soil quality index and the supply of organic fertilizers [19]. Furthermore, the addition of organic fertilizers also enhanced the enrichment of microorganisms beneficial to soil fertility, crop growth (Bacillus spp.), and soil bioremediation (Solicoccozyma spp.) and decreased the amounts of Fusarium spp. in soil [19]. In the present experiment, no microbiome analysis was performed; however, in a rhizobox experiment with soil fertilized with the same amendments, it was observed that MSW was the most effective in promoting microbial biodiversity, increasing phylum such as Bacillota, Pseudomonata, and Bacteroidota, while AFCS promoted Nitrosospherota and Chitinophaga [20]. The capacity of amendments to select different microorganisms could become a valuable tool to modify soil microbial biomass according to plant and soil needs. Using multiple fertilizer blends could become an innovative management strategy for enhancing crop production by improving the content of soil microbial keystone taxa in intensified agricultural ecosystems.

Fertilization of young-bearing trees aims at building the plant’s structure and preparing them to yield; thus, in this phase, N plays a crucial role, since it has a fundamental role in plant growth and development [21]. In previous experiments [22,23], it was observed that the requirement of walnut trees is about 160–180 kg N ha−1 year−1 during the full production phase (yielding approximately 6 t ha−1), which can be satisfied by a concentration of mineral N in the soil between 25 and 30 mg N ha−1 during the season. Since N is accumulated mainly in the kernel and, in the present experiment, plants still have very low nut production, the optimal level of mineral N in the soil should be even lower. In this trial, the values of mineral N remained in line with the needs of the walnut tree only in autumn, winter, and the beginning of spring of both years (with the exception of a winter peak of about 50 mg NO3−N kg−1); however, fertilization, whether mineral or organic, induced a strong increase, reaching values higher than 150 mg NO3−N kg−1, which are too high for bearing plants. The main issue with excess nitrate in soil is related to the fast oxidation of ammonium and release of the nitrate ion, which is not withheld by the soil’s holding capacity; consequently, nitrate could be lost through water percolation, promoting groundwater pollution. The release of nutrients from organic matter and the consequent timing and rate of mineral fertilization must be controlled to avoid possible negative environmental impacts if the availability of N in the soil is not synchronized with plant uptake. This value corresponds approximately to 840 kg N ha−1, which largely exceeds crop N uptake capacity and therefore represents a strong risk of nitrate leaching. If such mineral N is mainly present as nitrate and mobilized in the soil solution, concentrations would likely exceed the 50 mg NO3− L−1 limit established by the EU Nitrates Directive [24]. Although soil mineral N concentrations cannot be directly equated to leachate concentrations due to dilution, transport, and plant uptake processes; such a quantity indicates a substantial risk of nitrate losses to groundwater, justifying its negative environmental impact.

Nutrient release through the mineralization process depends on several variables, such as soil moisture and temperature, which cannot always be controlled. Consequently, splitting compost applications between spring and autumn (post-harvest) may help better synchronize nutrient availability with plant demand and reduce the risk of nutrient losses. This approach was previously tested in a long-term experiment on peach with positive results on nitrate release [25].

The application of organic matrices showed a positive effect on soil fertility by increasing the macronutrient availability as a consequence of MSW (P and K) and AFCS (Ca, Mg, and S) supply. It is well known that organic amendments are an important source of nutrients that are released slowly during the mineralization process. These nutrients, in combination with soil microorganisms and fauna, can contribute significantly to improving soil fertility and favourable plant-growing conditions [26,27]. AFCS also induced a decrease in soil pH, which could, especially in the long term, improve the uptake of micronutrients (such as Fe, Mn, etc.) [28,29]. The enhancement of soil fertility induced a slight increase in stem diameter and pruning wood; however, walnut is a slow-growing plant, and two years of measurements are not sufficient to define the effect of the treatments on the plant’s vegetative status.

Kernel, shell, and husk mineral composition was hardly ever influenced by treatments, probably due to the short duration of the experiment. However, the knowledge of the quantity of nutrients allocated in each fruit part could give important information on nutrient removal from the orchards and thus on nutrient requirements of plants. This calculation has little importance in bearing plants, since less than 100 g of walnuts were harvested per plant, but it could gain importance in adult plants. The data on the allocation of nutrients in different fruit parts evidenced that the kernel consistently exhibited the highest concentrations of N, P, Mn, and Zn, highlighting its metabolic activity and role in nutrient accumulation [29]. The shell generally showed the lowest nutrient levels, while the husk demonstrated elevated levels of K, Ca, B, and Fe. The application of organic compounds had little impact on the concentration of nutrients in walnut leaves. This may be because organic compounds generally release nutrients more slowly than mineral fertilizers [30]. This means that the nutrients may not have been available in sufficient quantities (or at times of high crop demand for nutrients) to be absorbed by the walnut trees.

The supply of amendments, no matter the type, induced an increase in total C, a direct effect of organic fertilizer application with high-carbon matrices. In the long run, C storage in walnut orchards could have an important role in climate regulation, triggering, at an ecosystem level, biological and ecological mechanisms that interact to capture atmospheric carbon dioxide [31]. The carbon dynamics in orchard soils are crucial in alleviating climate change, functioning as a carbon sink [32]. In a study on peach, it was observed that, after 14 years, the amount of C fixed into the soil by application of compost at 10 Mg ha−1 came approximately 60% from the amendment source and 40% from NPP (tree and grass), with a net increase in both C fractions compared to mineral fertilization [18]. Walnut, due to its relevant dimension when adult and the long duration of orchards, could provide, compared to conventional agricultural systems, higher C sequestration potential. Preliminary data on the C fluxes measured using eddy covariance in the orchard of the present experiment indicate that walnut is able to absorb C [33].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of organic fertilization in the sustainable management of bearing walnut orchards. The application of organic amendments improved soil fertility by increasing the availability of macro- and micronutrients and enhancing microbial biomass; however, attention should be paid to the rates and timing to avoid excessive nutrient availability, with possible negative environmental consequences. The data from this experiment lay the foundations for the definition of correct fertilization strategies in walnut groves at the bearing stage; however, it would be necessary to acquire information over the long term in order to intensify the crop’s productive potential and minimize negative impacts on the environment.

The supply of amendments, and consequently the increase of soil organic matter, is therefore a cornerstone of building sustainable agricultural systems that balance plant buildup and productivity with soil fertility. In addition, the potential C storage capacity of walnut orchards and the possibility of reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers while maintaining optimal nutrient levels are promising strategies for mitigating environmental impacts in intensive agricultural systems.

However, this study was conducted over only two growing seasons with a single soil type; consequently, the results could not be generalized to other environments and management systems. In addition, although high soil mineral N availability suggested an increased risk of nitrate leaching, N losses were not directly measured. The continuation of this research in the future should include direct assessments of nitrate leaching and testing split applications in order to improve nutrient use efficiency while minimizing environmental risks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020262/s1, Table S1. Effect of fertilization treatment and sampling year on pruned wood macronutrient concentration (g 100 g-1 DW); Table S2. Effect of fertilization treatment and sampling year on pruned wood micronutrient concentration (mg kg−1 DW).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and M.T.; methodology, E.B., M.Q., and M.T.; validation, M.T.; formal analysis, E.B. and M.Q.; investigation, M.M., F.B., and A.T.; resources, E.B., M.M., and F.B.; data curation, E.B.; M.M., and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.; writing—review and editing, M.Q., M.T., and A.T.; supervision, M.T.; project administration, E.B.; funding acquisition, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the REGION EMILIA-ROMAGNA project OTTIM.A.NOCE—Optimization of walnut agronomic management of walnut in regional environments through digitization of fruit-growing techniques; Rural Development Programme (Regional, Italy)—PSR 2014–2020. Operation 16.1.01; Focus area 4b.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset will be open access after 4 February 2026 at https://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/amsacta/8607.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the farm “Soc. Agr. Agro Noce” for hosting the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, C.; Zhang, M.; Wei, S.; Yang, Z.; Pan, X. Study of walnut brown rot caused by Botryosphaeria dothidea in the Guizhou Province of China. Crop Prot. 2023, 163, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Production–Walnuts. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0577901 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Crop Production in EU Standard Humidity. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/APRO_CPSH1__custom_4641514/default/bar?lang=en (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Frutta in Guscio. Available online: https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/files/1/1/d/D.65d07c3c5ae07fa72379/2024_v01_Scheda_Frutta_Guscio_Maggio.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Di Pierro, E.A.; Franceschi, P.; Endrizzi, I.; Farneti, B.; Poles, L.; Masuero, D.; Khomenko, I.; Trenti, F.; Marrano, A.; Vrhovsek, U.; et al. Valorization of Traditional Italian Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Production: Genetic, Nutritional and Sensory Characterization of Locally Grown Varieties in the Trentino Region. Plants 2022, 11, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. The central role of soil organic matter in soil fertility and carbon storage. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L. Physiological responses to humic substances as plant growth promoter. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, S.; Ertani, A.; Francisco, O. Soil-root crosstalking: The role of humic substances. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2017, 180, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioacchini, P.; Baldi, E.; Montecchio, D.; Mazzon, M.; Quartieri, M.; Toselli, M.; Marzadori, C. Effect of long-term compost fertilization on the distribution of organic carbon and nitrogen in soil aggregates and textural fractions. Catena 2024, 240, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabelle Climatologiche. Available online: https://www.arpae.it/it/temi-ambientali/clima/dati-e-indicatori/tabelle-climatiche (accessed on 19 January 2026).

- Hadas, A.; Portnoy, R. Nitrogen and carbon mineralization rates of composted manures incubated in soil. J. Environ. Qual. 1994, 23, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Domsch, K. A physiological method for the quantitative measurement of microbial biomass in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1978, 10, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, H.M. Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Siliceous and Organically-Based Matrices, Method 3052; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1988.

- Schumann, G.E.; Stanley, M.A.; Knudsen, D. Automated total nitrogen analysis of soil and plant samples. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1973, 37, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Castillo, J.G.; Ganeshanandam, S.; MacKay, B.R.; Lawes, G.S.; Lawoko, C.R.O.; Woolley, D.J. Applications of canonical discriminant analysis in horticultural research. HortScience 1994, 29, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparling, G.P. Ratio of microbial biomass carbon to soil organic carbon as a sensitive indicator of changes in soil organic matter. Soil Res. 1992, 30, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, E.; Cavani, L.; Margon, A.; Quartieri, M.; Sorrenti, G.; Marzadori, C.; Toselli, M. Effect of compost application on the dynamics of carbon in a nectarine orchard ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.Y.; He, H.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, L.; Mao, W.J.; Zhai, M.Z. Positive effects of organic fertilizers and biofertilizers on soil microbial community composition and walnut yield. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 175, 104457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ni, T.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Fang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Li, R.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q. Effects of organic–inorganic compound fertilizer with reduced chemical fertilizer application on crop yields, soil biological activity and bacterial community structure in a rice–wheat cropping system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 99, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarelli, G.; Sangiorgio, D.; Pastore, C.; Filippetti, I.; Buyukfiliz, F.; Baldi, E.; Toselli, M. Soil application of urban waste-derived amendments increased microbial community diversity in the grapevine rhizosphere: A rhizobox approach. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.A.; Vega, A.; Bouguyon, E.; Krouk, G.; Gojon, A.; Coruzzi, G.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Nitrate transport, sensing, and responses in plants. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, M.; Sorrenti, G.; Quartieri, M.; Marangoni, B.; Marcolini, G.; Baldi, E. Il noce guadagna spazio al Nord. Frutticoltura 2014, 5, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Manfrini, L.; Perulli, G.D.; Bortolotti, G.; Boini, A.; Bonora, A.; Anconelli, S.; Solimando, D.; Gentile, S.; Baldi, E.; Polidori, G.; et al. Noce, ridurre asporti idrici e nutrizionali senza danneggiare la produzione. Frutticoltura 2021, 9, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- The Council of the European Communities. Council directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 concerning the protection of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 1991, 375, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Toselli, M.; Baldi, E.; Cavani, L.; Mazzon, M.; Quartieri, M.; Sorrenti, G.; Marzadori, C. Soil-plant nitrogen pools in nectarine orchard in response to long-term compost application. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldan, E.; Nedeff, V.; Barsan, N.; Culea, M.; Panainte-Lehadus, M.; Mosnegutu, E.; Tomozei, C.; Chitimus, D.; Irimia, O. Assessment of manure compost used as soil amendment—A review. Processes 2023, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.S.; Naresh, R.K.; Mandal, A.; Walia, M.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Singh, R.; Dhaliwal, M.K. Effect of manures and fertilizers on soil physical properties, build-up of macro and micronutrients and uptake in soil under different cropping systems: A review. J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 42, 2873–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, B.; Szulc, W.; Sosulski, T.; Stępień, W. Soil micronutrient availability to crops affected by long-term inorganic and organic fertilizer applications. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.; Sui, J.; Zhang, J. Metabolomics reveals significant variations in metabolites and correlations regarding the maturation of walnuts (Juglans regia L.). Biol. Open 2016, 5, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaji, H.; Chandran, V.; Mathew, L. Organic fertilizers as a route to controlled release of nutrients. In Controlled Release Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture; Lewu, F.B., Volova, T., Thomas, S., Rakhimol, K.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.I.D.; Brito, L.M.; Nunes, L.J.R. Soil carbon sequestration in the context of climate change mitigation: A review. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzfeld, T.; Heinke, J.; Rolinski, S.; Müller, C. Soil organic carbon dynamics from agricultural management practices under climate change. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 1037–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardino, M.; Brilli, L.; Carotenuto, F.; Famulari, D.; Fiorini, L.; Gioli, B.; Zaldei, A.; Chieco, C. Greenhouse gases emission and absorption in an extensive young walnut orchard (Juglans regia L.) in Italy. In Proceedings of the ICOS Science Conference 2024, Versaielles, France, 10–12 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.