Abstract

Accurate weed detection in crop fields remains a challenging task due to the diversity of weed species and their visual similarity to crops, especially under natural field conditions where lighting and occlusion vary. Traditional methods typically attempt to directly identify various weed species, which demand large-scale, finely annotated datasets and often suffer from low generalization. To address these challenges, this study proposes a novel dual-model framework that simplifies the task by dividing it into two tractable stages. First, a crop segmentation network is used to identify and remove cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. ssp. pekinensis) regions from field images. Since crop categories are visually consistent and singular, this stage achieves high precision with relatively low complexity. The remaining non-crop areas, which contain only weeds and background, are then subdivided into grid cells. Each cell is classified by a second lightweight classification network as either background, broadleaf weeds, or grass weeds. The classification model achieved F1 scores of 95.1%, 91.1%, and 92.2% for background, broadleaf weeds, and grass weeds, respectively. This two-stage approach transforms a complex multi-class detection task into simpler, more manageable subtasks, improving detection accuracy while reducing annotation burden and enhancing robustness under the tested field conditions.

1. Introduction

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. ssp. pekinensis) is a nutritionally valuable crop, rich in essential minerals such as iron, calcium, and potassium, as well as vitamins C and E [1,2]. Its well-recognized health benefits and high nutritional content have contributed to a significant global expansion in its cultivation. However, weed infestation remains a major constraint in cabbage production, as weeds compete with crops for vital resources such as light, water, and nutrients [3]. Consequently, effective weed management is a critical component of sustainable cabbage farming. Herbicide application is a common approach to weed control in cabbage fields. However, as with many minor crops, the number of herbicides registered for use in cabbage is limited. Currently, bensulide, clomazone, DCPA, oxyfluorfen, and trifluralin are approved for preplant incorporated applications, while clethodim, clopyralid, DCPA, napropamide, and sethoxydim are used for post-emergent, over-the-top treatments [4,5]. Excessive or non-targeted herbicide use not only increases production costs but also increases the likelihood of pesticide residues in vegetable products [6,7]. To address these challenges, precision herbicide application—enabled by advancements in sensing and automation technologies—has emerged as a promising solution to reduce herbicide input, weed control cost, pesticide residues, and minimize environmental impact [8,9].

Traditional weed detection methods have primarily relied on machine vision and image processing techniques to automate weed identification in agricultural fields. For instance [10] utilized texture features, such as uniformity, local homogeneity, and contrast, to differentiate weeds from grasses with similar coloration in turf environments. However, the reliability of texture-based approaches is limited, as these features can vary significantly with lighting conditions and weed growth stages, thereby reducing detection accuracy and consistency. Similarly [11] employed color-based techniques, leveraging the distinct red stems of certain weed species to distinguish them from the green stems of wheat (Triticum turgidum L.) and soybean (Glycine Max L. Merr.) plants. While effective in specific cases, this color-based method lacks generalizability to weed species with different stem pigmentation. Additionally, shape descriptors and spectral signatures have also been explored for weed detection [12,13]. However, shape-based methods often perform poorly when plant leaves overlap or are occluded, and spectral-based approaches are particularly sensitive to lighting variability [14]. These limitations highlight the inherent challenges associated with traditional image processing-based weed detection and underscore the need for more robust and adaptive methods capable of maintaining high accuracy under diverse and complex field conditions.

In recent years, deep learning models have been increasingly investigated for weed detection [15,16,17,18,19,20], including You Only Look Once (YOLO) [21], Region-Based Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNN) [22], and Faster R-CNN [23]. These methods typically rely on manually annotated weed data and use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to learn the features of weeds for detection. However, the diversity of weed species and their considerable morphological variation across developmental stages make it highly challenging and prohibitively expensive to construct a comprehensive detection dataset that fully captures this variability. To overcome the limitations of relying solely on deep learning, some researchers have explored hybrid approaches that integrate deep learning with image processing techniques to improve weed detection accuracy [24]. For example, [25] proposed an indirect detection method, where a deep learning model first identifies vegetable crops, and the remaining green areas in the image are then considered as weeds. The optimal confidence thresholds for this method were 0.4, 0.5, and 0.4/0.5 for YOLOv3, CenterNet, and Faster R-CNN, respectively. This approach avoids the need to construct a large-scale weed detection dataset by focusing on crop identification; however, it still heavily depends on the reliability of image processing. Specifically, the method is vulnerable to variations in lighting and color features, and it may misclassify other green objects—such as green-appearing soil surface materials or moss—as weeds. This issue limits its robustness and overall accuracy under natural field conditions [14,26].

To overcome the limitations of relying solely on deep learning and its integration with image processing methods, while reducing the cost of constructing large-scale datasets and enhancing weed detection accuracy, this study proposes a dual-model strategy for weed detection. The method employs two independent models to achieve more efficient weed detection in cabbage fields. First, an image segmentation model is used to identify cabbage. Given the morphological uniformity of vegetable crops, this study focuses on building a cabbage segmentation dataset, thereby significantly reducing annotation workload and cost. The identified cabbage regions are then masked out in the original image to eliminate interference during weed detection. As herbicide selectivity differs across weed types—for instance, Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase)-inhibiting herbicides (e.g., clethodim or sethoxydim) versus synthetic auxin herbicides (e.g., 2,4-D or dicamba) [27,28,29]—a pre-trained classification network is then employed. This network divides the processed image into grid regions aligned with sprayer nozzles and classifies each grid as background, broadleaf weeds, or grass weeds. Moreover, to reduce the complexity of the dual-model approach, a lightweight segmentation model based on YOLO11n-seg is developed. Therefore, the objectives of this study are twofold: (1) to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed dual-model approach for weed detection in cabbage fields, and (2) to optimize a lightweight, efficient segmentation model for accurate and robust cabbage segmentation.

2. Method

2.1. Overview

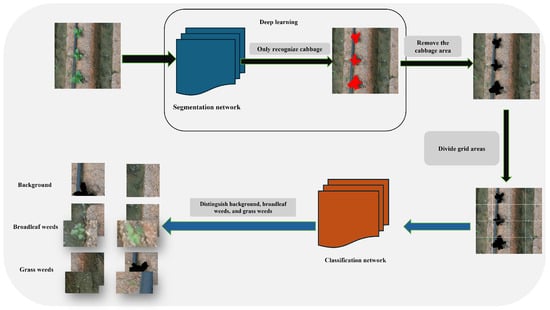

The overall workflow of this study is illustrated in Figure 1. The proposed approach involves the pre-training of two distinct neural networks: a segmentation network designed to delineate cabbage crops, and a classification network tasked with discriminating among background, broadleaf weeds, and grass weeds. By leveraging two independent networks, this strategy effectively mitigates parameter interference and streamlines the processing pipeline, enabling each network to focus exclusively on a dedicated task. The principal steps of the proposed methodology are as follows:

- Develop a cabbage segmentation training dataset and optimize a lightweight, efficient segmentation network based on YOLO11n-seg to enhance the accuracy of cabbage region extraction from images.

- Construct a classification training dataset comprising background, broadleaf weeds, and grass weeds, and independently train a high-performance classification model to accurately execute weed classification tasks.

- Apply the segmentation network to detect and delineate cabbage regions, followed by the use of image processing techniques to remove these regions from the original images. Subsequently, partition the processed images into an n × n grid, where n corresponds to the effective coverage area of the herbicide sprayer nozzle.

- Employ the classification network to categorize each grid cell, thereby providing a foundation for targeted herbicide application.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Dual-Model weed detection in cabbage fields.

2.2. Dataset and Experimental Setup

Images used for training, validation, and testing of the segmentation and classification models were collected from cabbage fields at the Peking University Institute of Advanced Agricultural Sciences, located in Weifang, Shandong Province, China (36.1° N, 119.1° E). A DJI Phantom 4 RTK SE drone (DJI, Shenzhen, China), equipped with a 20-megapixel camera, was used to acquire nadir-view images (vertical angle of 90°) at a flight altitude of 3 m. The original image resolution was 5472 × 3648 pixels. To ensure consistency and facilitate efficient computation, all images were resized to 1824 × 1824 pixels.

For the segmentation task, a total of 2145 images were manually annotated with pixel-level cabbage masks. The dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and testing subsets using an 8:1:1 ratio, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of images used for network segmentation and dataset partitioning.

For the classification task, each resized segmentation image was divided into a 4 × 4 grid, resulting in 16 non-overlapping sub-images per original image. A total of 8817 grid images were selected and categorized into three classes: broadleaf weeds, grass weeds, and weed-free (background). To prevent data leakage, dataset splitting was performed at the original image level, such that all grid patches derived from the same resized image were assigned to the same subset (training, validation, or testing), following an 8:1:1 ratio, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of images used for network classification and dataset partitioning.

The segmentation and classification experiments in this study were conducted on the same device running Ubuntu 20.04.1. The system was equipped with an Intel Core i9-10920X processor (3.50 GHz, Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Python 3.8 and PyTorch 1.12.0 were used for model development and training. For YOLO model training, each experiment was run for 100 epochs with a learning rate of 0.01, using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer and a batch size of 8. The classification network was trained for 30 epochs with the same learning rate of 0.01.

2.3. Segmentation Model

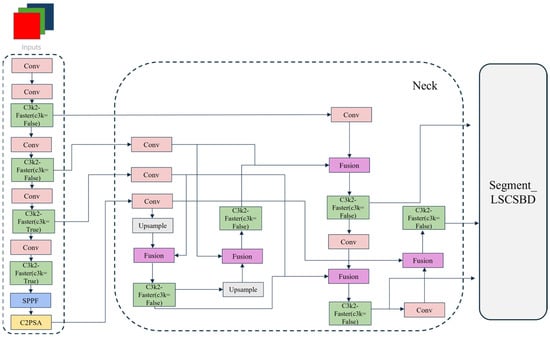

To improve the segmentation accuracy of cabbage while reducing model complexity, this study proposes an enhanced lightweight and efficient cabbage crop segmentation network, FBL-YOLONet (Faster-Block_BiFPN_LSCSBD_YOLONet). The network is developed based on YOLO11n-seg, incorporating the Faster Block module into the C3k2 module to form the C3k2-Faster module, replacing the original Neck architecture with a BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network) structure, and adopting LSCSBD (Lightweight Shared Convolutional Separator Batch-Normalization Detection Head) as the segmentation head. Furthermore, corresponding adjustments and optimizations were applied to the channel configurations within the architecture. In particular, the backbone’s output channels were reduced from 1024 to 512, thereby decreasing the computational burden while maintaining segmentation performance. This design enables the model to achieve more efficient outcomes with reduced resource consumption. The overall improved architecture is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

FBL-YOLONet overall network structure. Abbreviations: C2PSA, Convolutional block with parallel spatial attention; C3k2, Cross stage partial with kernel size 2; LSCSBD, Lightweight shared convolutional separator batch-normalization detection head; SPPF, Spatial pyramid Pooling–Fast.

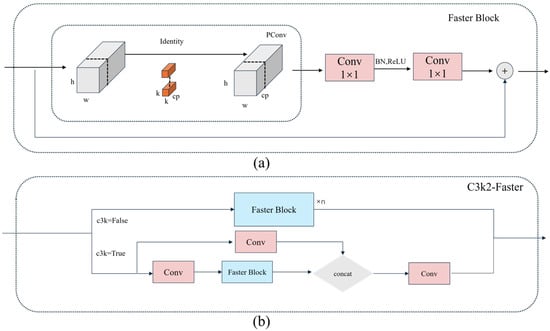

2.3.1. C3k2-Faster

In previous lightweight CNN architectures, including MobileNet [30], ShuffleNet [31], and GhostNet [32], depthwise separable convolution (DWConv) and group convolution (GConv) are commonly used to reduce FLOPs. However, these operations tend to increase memory access overhead, which may negatively affect practical inference speed. The FLOPs of DWConv are calculated as:

Since DWConv often needs to be paired with pointwise convolution, the actual memory access during its use can be expressed as:

This is generally considered the minimal memory cost. However, it is still higher than:

In contrast, the Faster Block module utilizes PConv combined with pointwise convolution to replace the traditional depthwise separable convolution [33]. This approach allows both spatial feature extraction and efficient channel information fusion. The memory access cost of the Faster Block can be approximated as:

This leads to improved real-time performance. Figure 3a illustrates the structure of the Faster Block module, while Figure 3b depicts the C3k2-Faster module formed by integrating it into the C3k2 architecture. The PConv proposed in the module effectively reduces redundant computations and optimizes memory access, thereby significantly enhancing the inference speed of the neural network. This makes it highly suitable for the real-time requirements of weed detection.

Figure 3.

(a) is the structure diagram of the Faster Block module, and (b) is the structure diagram of the C3k2-Faster module. Abbreviations: C3k2, Cross-stage partial with kernel size 2; PConv, Partial convolution.

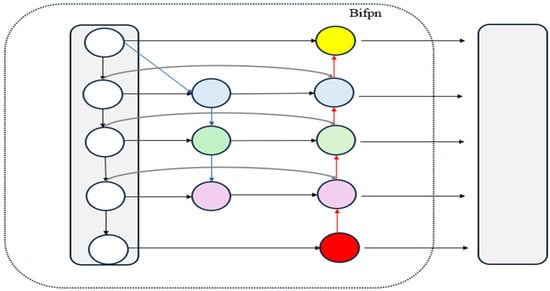

2.3.2. BiFPN

The BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network) is a multi-scale network structure designed for efficient feature fusion [34]. Traditional methods typically treat input features equally, whereas BiFPN introduces learnable weights to allow the network to perform weighted fusion based on the importance of each feature. Reference [34] proposed three weighted feature fusion strategies to enhance the network’s expressive capability and computational efficiency: (1) Unbounded fusion:

where is a learnable weight, which can be a scalar for the entire feature, a vector for each channel, or a multidimensional tensor for each pixel. (2) Softmax-based fusion:

where Softmax normalization transforms all weights into probability values between 0 and 1, representing the importance of each input feature. However, this method requires additional exponential calculations, which may increase computational overhead and affect inference speed. (3) Fast normalized fusion:

where and is a small constant to prevent numerical instability. This method ensures that the weight values remain between 0 and 1, but due to the absence of Softmax operations, it offers higher computational efficiency.

The BiFPN architecture is shown in Figure 4. Compared to the traditional Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [35], the BiFPN incorporates the following improvements: (1) If a node has only one input edge, it is considered to contribute minimally to information aggregation and is therefore removed to reduce computational redundancy. (2) For features at the same level, BiFPN adds extra connections between the original input and output nodes to enable more comprehensive information fusion without significantly increasing computational cost. (3) BiFPN employs a bidirectional feature propagation method, featuring both top-down and bottom-up paths, enabling information to flow efficiently across multiple scales. In the BiFPN structure, each bidirectional cross-scale path can be considered a feature network layer, and these layers can be repeated multiple times to further enhance feature expression. Thus, we have incorporated the BiFPN into our Neck structure to improve performance.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of BiFPN structure. Abbreviations: BiFPN, Bidirectional feature pyramid network.

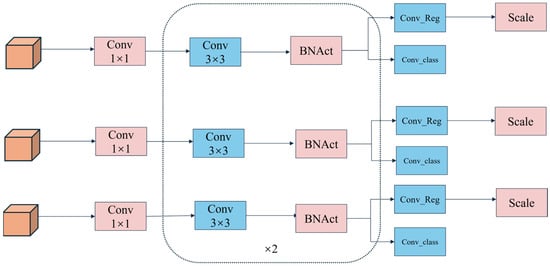

2.3.3. Segment_LSCSBD

To improve the efficiency and adaptability of weed detection models in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) fields, [36] proposed a lightweight shared convolutional separator batch-normalization detection head, LSCSBD, to replace traditional detection heads. Unlike the independent detection branches used in conventional YOLO series models, LSCSBD adopts shared convolutional layers to increase parameter utilization and reduce the risk of overfitting. Inspired by the design principles of NAS-FPN, this method computes batch normalization separately for each detection layer while sharing convolutional layers, thereby enhancing computational efficiency. Additionally, the method introduces scale-layer dynamic adjustments to feature maps, addressing the issue of inconsistent target scales between different detection heads. These optimizations reduce both the number of parameters and computational costs while minimizing accuracy loss, making the model more robust and better suited for deployment in real-world agricultural scenarios. We applied this structure as the segmentation head in YOLO11n-seg, resulting in the Segment_LSCSBD. Figure 5 illustrates the LSCSBD structure.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of LSCSBD structure. Abbreviations: BNAct, batch normalization followed by activation function; Conv_Reg, a convolutional layer responsible for bounding box regression prediction.

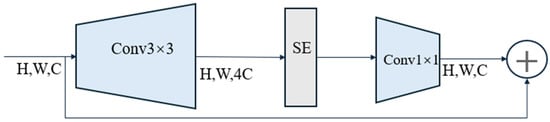

2.4. Classification Model

This study uses EfficientNetV2 [37] as the classification network. The model optimizes training speed and parameter efficiency through training-aware neural architecture search and progressive learning. Compared to EfficientNet [38], EfficientNetV2 utilizes the Fused-MBConv structure shown in Figure 6, which enhances computational efficiency in the early layers of the model. Additionally, EfficientNetV2 further improves training speed and generalization ability by dynamically adjusting image sizes and regularization strategies. Furthermore, EfficientNetV2 incorporates a progressive learning strategy, allowing for faster high-quality model training within the same computational resources. [37] demonstrated through experiments that EfficientNetV2 significantly outperforms existing state-of-the-art models in training speed and can reduce the parameters by up to 6.8 times. EfficientNetV2 is selected as the classification network to balance inference efficiency and accuracy for real-time field applications.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of Fused-MBConv structure. Abbreviations: SE, Squeeze-and-Excitation networks.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

YOLO11n-seg separates objects through masks. To better evaluate the improved segmentation model, we used the following metrics: mask precision, mask recall, and mask mAP50. The Precision-Recall (P-R) curve illustrates the relationship between Precision and Recall for the samples, while AP50 represents the area under the P-R curve at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 50. mAP refers to the mean average precision across different categories. The classification network is primarily evaluated using the F1 score. The formula for the F1 score is as follows:

where refers to the number of positive samples that are correctly identified, refers to the number of negative samples incorrectly classified as positive, and refers to the number of positive samples incorrectly classified as negative.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cabbage Segmentation

3.1.1. Ablation Experiment

To evaluate the contribution of each module to the overall model performance, extensive ablation experiments were conducted, with the results presented in Table 3. The baseline YOLO11n-seg network contains 2,834,763 parameters and has a model size of approximately 6.0 MB. Based on this architecture, several enhancements were introduced: (1) integration of the Faster Block module; (2) optimization of the neck structure using the BiFPN mechanism; (3) improvement of the segmentation head; and (4) lightweight modifications to the channel configurations throughout the network. These refinements effectively reduced both the parameter quantity and model size, while simultaneously enhancing segmentation performance. The proposed FBL-YOLONet outperformed the original YOLO11n-seg in key metrics such as mask mAP50 and mask recall, and achieved shorter inference times. Although minor decreases were observed in mask mAP50–95 (%) and mask precision (%), it is noteworthy that the improved model—occupying only 2.6 MB—achieved a higher mask mAP50 than the baseline, while reducing the overall size by more than 50%. These findings demonstrate that FBL-YOLONet achieved a favorable balance between segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency. Its significantly reduced complexity and stable performance make it particularly suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Table 3.

Comparison of ablation experiment results.

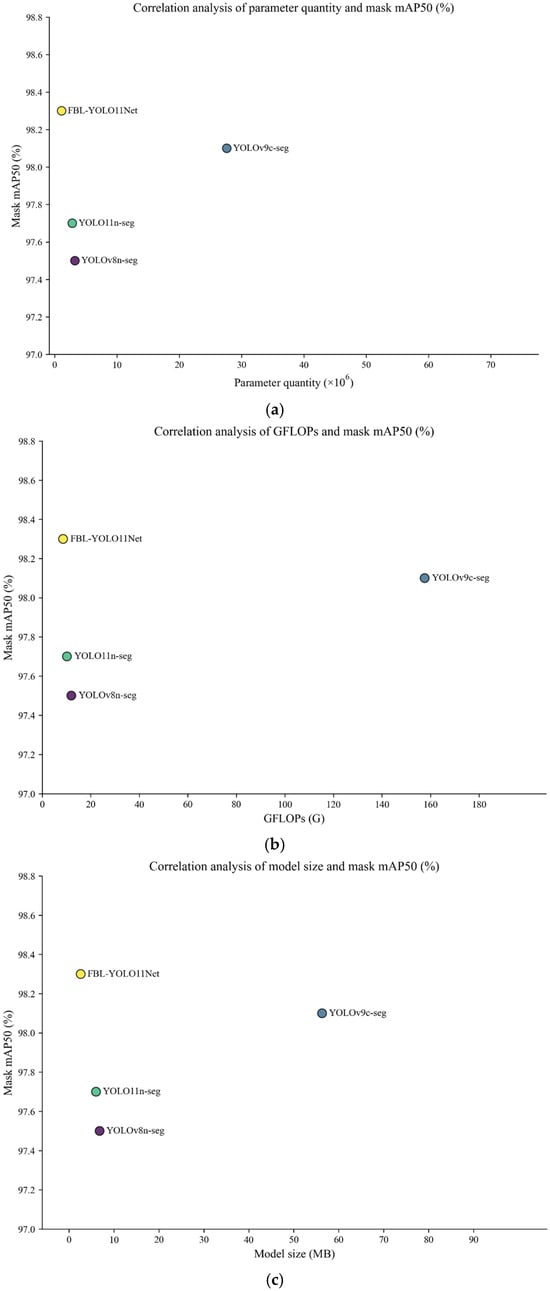

3.1.2. Comparative Experiment

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed segmentation model, comparative experiments were conducted using the cabbage dataset. The results are summarized in Table 4. As illustrated in Figure 7, the improved network demonstrated significant advantages in metrics related to lightweight (parameter quantity, GFLOPs, and model size), while achieving the best mask mAP50 (98.3%). Although the optimized network exhibited marginally lower mask precision and inference speed compared to the top performer in these specific metrics, its performance remained highly competitive. Specifically, the proposed network achieved a mask precision of 97.0% and an inference speed of 6.4 ms. In contrast, YOLOv8n-seg attained the highest mask precision (98.0%) and the fastest inference speed (6.1 ms). However, its model size is 6.8 MB with 3,258,259 parameters, consuming significantly more resources than the proposed network in this study. Remarkably, the proposed segmentation network achieved the optimal mask mAP50 (98.3%) and mask recall (95.5%), while maintaining a compact model size of only 2.6 MB and a parameter quantity of 1,117,200. These results demonstrate that the proposed model achieves an effective balance between lightweight design and segmentation performance, making it well suited for deployment on resource-constrained mobile devices.

Table 4.

Comparison of model experimental results.

Figure 7.

Scatter plot showing (a) the Relationship between parameter count and mask mAP50 across different YOLO models; (b) the relationship between GFLOPs and mask mAP50; and (c) the relationship between model size and mask mAP50.

The YOLO series is widely used in real-time object detection tasks due to its efficiency and inference speed [39,40]. YOLO11n-seg, in particular, extends the YOLO11 architecture to segmentation tasks. Building upon this structure, the proposed model integrates further enhancements. The results of both ablation and comparative experiments demonstrate that the improved model delivers the most stable performance on the cabbage dataset, while achieving the smallest model size and the fewest parameters among the models tested.

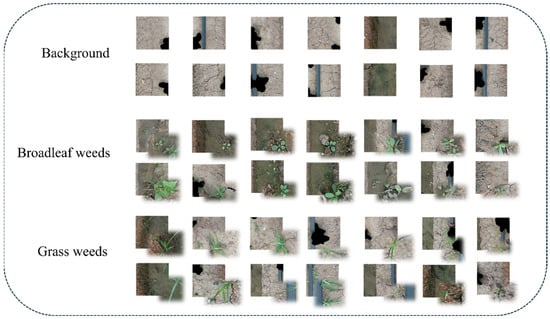

3.2. Classification Experiment

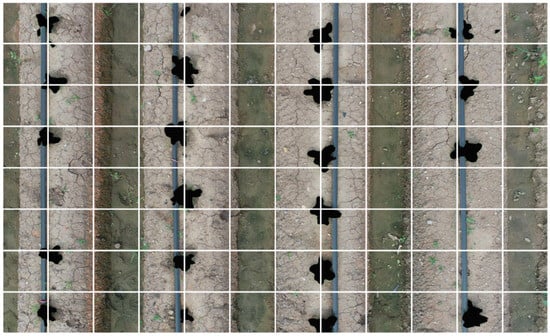

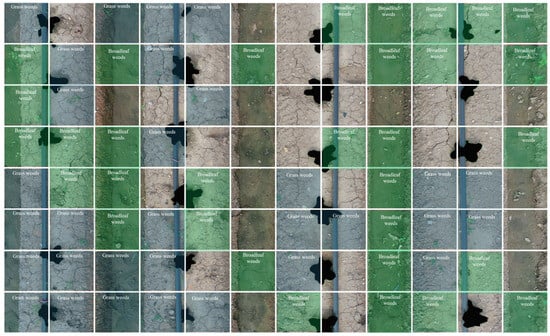

After cabbage regions are identified, the corresponding pixels are masked out in the original image. The remaining image is then divided into multiple grid regions based on the coverage area of the sprayer nozzle. A classification model is then employed to predict the category of each grid region, as illustrated in Figure 8. The categories include background, broadleaf weeds, and grass weeds. By removing the cabbage regions in advance, the model avoids the challenging task of directly distinguishing between cabbage and weeds, thereby enhancing the discriminative capability of the classification model.

Figure 8.

Example of images used for training the classification network.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted training and inference experiments under two conditions: with cabbage regions retained and with them removed. The results, presented in Table 5, indicate that removing the cabbage regions resulted in notable improvements in weed recognition performance. Specifically, the F1 score for broadleaf weed detection increased from 89.4% to 91.1%, and for grass weed detection from 90.4% to 92.2%. These results demonstrate that our method significantly enhances weed detection performance compared to direct classification. Notably, despite employing a dual-model strategy, the inference speed remains sufficient for real-time applications. Specifically, the segmentation model requires 6.4 ms and the classification model 6.7 ms per image, resulting in a total inference time of 13.1 ms, as shown in Table 6, which meets the requirements of real-time operation. It should be noted that all 16 grid tiles from each image are processed in a single batch forward pass during classification; therefore, the reported classification latency is measured per image and is not accumulated across individual tiles. In addition, the grid tiles are generated by in-memory tensor slicing without file-level cropping; the overhead of grid partitioning is negligible compared to network inference. Accordingly, all reported timings correspond to GPU-side per-image inference under the described experimental setup.

Table 5.

Classification network results.

Table 6.

Comparison of representative deep learning–based weed detection studies and methodological paradigms.

Table 6 compares the proposed method with representative deep learning–based weed detection approaches reported in the literature. Most existing methods rely on direct weed detection or segmentation and therefore require multi-species weed datasets. In contrast, the proposed framework only requires annotation of the relatively uniform crop class and subsequently performs grid-level weed-type classification after crop removal, substantially reducing annotation effort. Compared with crop-first approaches based on green-pixel extraction, the proposed method mitigates sensitivity to illumination variations and naturally aligns with sprayer nozzle layouts. As shown in Table 6, the proposed approach achieves competitive weed recognition performance, demonstrating its practical suitability for precision herbicide spraying applications.

3.3. Weed Detection

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 visually demonstrate the overall recognition process of the proposed method at different stages. First, the FBL-YOLONet network is used to segment the cabbage from the original image, accurately identifying and extracting the cabbage region. Subsequently, these regions are removed from the image, with their pixels set to black. The image is subsequently divided into grid regions based on the operational coverage area of the herbicide sprayer nozzle, as shown in Figure 10. Within each grid, a pre-trained classification network performs weed detection, categorizing the regions as shown in Figure 11. Each grid region is ultimately classified as background, broadleaf weeds, or grass weeds.

Figure 9.

Original aerial image of a cabbage field captured by a drone.

Figure 10.

Cabbage regions removed by FBL-YOLONet; residual areas divided into nozzle-sized grids for precision weed spraying.

Figure 11.

Final classification results generated by FBL-YOLONet, where blue grids indicate grass weeds, green grids denote broadleaf weeds, and the remaining grids represent background areas.

It is worth noting that when both broadleaf and grass weeds coexist within the same grid, the antagonistic effects of herbicides generally make their combined use impractical [42]. For example, studies have reported that tank-mixing Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase)-inhibiting herbicides (e.g., clethodim or sethoxydim) with synthetic auxin herbicides (e.g., 2,4-D or dicamba) can reduce weed control efficacy due to antagonism [43,44]. Therefore, in most operations, only one type of herbicide is applied during a single pass. In this study, regions containing both weed types are not differentiated further during classification; herbicide application is carried out once the presence of any weed type is detected within a grid, ensuring operational simplicity and consistent weed control. However, [45] documented that in some cases, such antagonism can be avoided by adopting the separate boom (SPB) application method. The SPB method significantly increased herbicide efficacy by physically separating herbicide applications, allowing the active ingredients to function optimally. Such approaches may provide valuable guidance for future precision herbicide application strategies based on dual-model weed detection.

The dual-model weed detection method proposed in this study effectively addresses several limitations commonly associated with existing deep learning-based weed detection approaches. Traditional methods often require the construction of datasets covering varying weed species, growth stages, ecotypes, and varying densities [46,47,48]. This greatly increases the cost, complexity, and time required for training dataset construction. In contrast, our approach leverages the relative uniformity of crops by requiring only a dataset for cabbage segmentation, thereby substantially reducing the burden of dataset preparation.

The proposed framework employs two independently trained models: the first performs cabbage segmentation, and the second classifies the pre-defined grid regions. This division of tasks simplifies the function of each model, improving training efficiency. Unlike conventional deep learning frameworks that typically rely on bounding boxes for weed detection, our method introduces a grid-based partitioning strategy applied to the output of the segmentation model. This design aligns with the operational pattern of precision sprayers, which use rows of nozzles to treat predefined areas. The image is partitioned into grids corresponding to the physical coverage of each nozzle. When weeds are detected within a grid, the associated nozzle is activated for targeted herbicide application. This grid-based strategy not only facilitates precise and efficient weed control but also enables the method to dynamically adapt to the operational range of different spraying systems [49].

The final experimental results highlight the remarkable performance of the proposed dual-model strategy. The improved segmentation model achieved a mask mAP50 of 98.3% for cabbage segmentation, confirming its superiority in accurately identifying crop regions. In addition, the classification model attained impressive F1 scores of 91.1% for broadleaf weeds and 92.2% for grass weeds, demonstrating its strong capability to distinguish between different weed types. It is worth noting that in the classification experiments, weeds were categorized into two major types: grass weeds and broadleaf weeds. This classification reflects the distinct herbicide selectivity required for effective control of these weed types. By distinguishing weeds in this manner, herbicide application can be more precisely targeted, minimizing unnecessary usage and ultimately reducing overall herbicide consumption.

Comparative experiments further demonstrate that, compared to approaches relying solely on classification networks, our dual-model strategy significantly enhances recognition performance. Unlike conventional direct weed detection methods, our approach not only reduces the cost and complexity of dataset construction but also markedly enhances recognition accuracy. Notably, while previous deep learning–based weed detection studies often combined image processing techniques that rely on the extraction of green pixels [41], such methods are highly sensitive to variable lighting conditions, which likely compromise detection accuracy in natural field environments. In contrast, our dual-model framework does not rely on image processing for weed detection and was trained on images collected under diverse lighting environments, and thus it likely better accommodates natural variations in brightness and shadows and enhances robustness under the tested field conditions.

It should be noted that, while the dataset includes natural variations in acquisition dates, illumination conditions, and crop growth stages within a single field site, future work will focus on validating the proposed framework using more diverse, multi-site datasets under broader environmental conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes a dual-model strategy for weed detection in cabbage fields, effectively addressing the challenges faced by traditional deep learning methods. Specifically, we developed a lightweight FBL-YOLONet segmentation network based on YOLO11n-seg, capable of accurately distinguishing cabbage crops from the background. To facilitate precision spraying, a network-based image partitioning method was employed on images with cabbage crops removed, enabling dynamic segmentation of the target area to align with the coverage of the weeding actuator. Additionally, a dedicated classification network was used to further distinguish between broadleaf and grass weeds. Compared to conventional deep learning approaches that directly detect weeds, the dual-model strategy proposed in this study reduces the cost of constructing training datasets while improving weed detection accuracy. Moreover, unlike recent methods that combine deep learning with traditional image processing, our approach overcomes the sensitivity of pixel-based algorithms to lighting variations by improving robustness across diverse field conditions. Future work will validate the proposed framework with more diverse datasets collected across multiple field sites, extend it to other vegetable crops, and explore its integration into field-deployable precision spraying or robotic platforms for end-to-end evaluation under real operational conditions. Overall, the dual-model strategy presented in this work greatly improved accuracy and provided stronger technical support for achieving precise and efficient weed control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and X.J.; methodology, X.J.; software, W.Z.; validation, M.L., X.Z. and X.J.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, Y.J.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing, X.J. and A.L.; visualization, M.L.; supervision, A.L.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, X.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Weifang Science and Technology Development Plan Project (Grant No. 2024ZJ1097), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. SYS202206), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32072498), and the Taishan Scholar Program.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACCase | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| AP50 | Average Precision at IoU = 50 |

| BiFPN | Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| C2PSA | Convolutional block with parallel spatial attention |

| C3k2 | Cross-stage partial with kernel size 2 |

| DCPA | dimethyl tetrachloroterephthalate |

| DWConv | Depthwise Separable Convolution |

| FBL-YOLONet | Faster-Block_BiFPN_LSCSBD_YOLONet |

| FLOPs | Floating Point Operations |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| GConv | Group Convolution |

| GFLOPs | Giga floating-point operations per second |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| LSCSBD | Lightweight Shared Convolutional Separator Batch-Normalization Detection Head |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| MB | Megabyte |

| PConv | Partial Convolution |

| PM | Proposed method |

| P-R | Precision-Recall |

| R-CNN | Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| SPB | Separate Boom |

| SPPF | Spatial pyramid Pooling–Fast |

| TP | True Positive |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Moreb, N.; Murphy, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Cabbage. In Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Fruits and Vegetables; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.K.; Sharma, S.R.; Singh, B. Variation in mineral concentrations among cultivars and germplasms of cabbage. J. Plant Nutr. 2009, 33, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kaur, R.; Chauhan, B.S. Understanding crop-weed-fertilizer-water interactions and their implications for weed management in agricultural systems. Crop Prot. 2018, 103, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Boyd, N.S.; Dittmar, P.J. Evaluation of herbicide programs in Florida cabbage production. HortScience 2018, 53, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotarelli, L.; Dittmar, P.J.; Dufault, N.; Wells, B.; Desaeger, J.; Noling, J.W.; McAvou, E.; Wang, Q.; Miller, C.F. Cole crop production. Veg. Prod. Handb. Fla. 2019, 2020, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kocourek, F.; Stará, J.; Holý, K.; Horská, T.; Kocourek, V.; Kováčová, J.; Kohoutková, J.; Suchanová, M.; Hajšlová, J. Evaluation of pesticide residue dynamics in Chinese cabbage, head cabbage and cauliflower. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2017, 34, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Y.; Liu, X.-J.; Yu, X.-Y.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Hong, X.-Y. Pesticide residues in the spring cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata) grown in open field. Food Control 2007, 18, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.; Pereira, G.; Pucci, L.; Alves, D.; Gomes, C.; Reis, M. Tolerance of cabbage crop to auxin herbicides. Planta Daninha 2020, 38, e020218387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yura, W.; Muhammad, F.; Mirza, F.; Maurend, Y.; Widyantoro, W.; Farida, S.; Aziz, Y.; Desti, A.; Edy, W.; Septy, M. Pesticide residues in food and potential risk of health problems: A systematic literature review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 894, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U.; Kondo, N.; Arima, S.; Monta, M.; Mohri, K. Weed detection in lawn field using machine vision utilization of textural features in segmented area. J. Jpn. Soc. Agric. Mach. 1999, 61, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- El-Faki, M.S.; Zhang, N.; Peterson, D. Weed detection using color machine vision. Trans. ASAE 2000, 43, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Xu, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, J.; Shen, B. Weed identification from winter rape at seedling stage based on spectrum characteristics analysis. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, P.; He, Y. Velocity representation method for description of contour shape and the classification of weed leaf images. Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 109, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, B.; Kang, X.; Ding, Y. Review of weed detection methods based on computer vision. Sensors 2021, 21, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Han, K.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. Detection and coverage estimation of purple nutsedge in turf with image classification neural networks. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3504–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razfar, N.; True, J.; Bassiouny, R.; Venkatesh, V.; Kashef, R. Weed detection in soybean crops using custom lightweight deep learning models. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.U.; Eesaar, H.; Abbas, Z.; Seneviratne, L.; Hussain, I.; Chong, K.T. Advanced drone-based weed detection using feature-enriched deep learning approach. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 305, 112655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sharpe, S.M.; Schumann, A.W.; Boyd, N.S. Deep learning for image-based weed detection in turfgrass. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 104, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Weng, G.; Chen, Y. An overview of industrial image segmentation using deep learning models. Intell. Robot 2025, 5, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingting, Z.; Xunru, L.; Bohuan, X.; Xiaoyu, T. An in-vehicle real-time infrared object detection system based on deep learning with resource-constrained hardware. Intell. Robot. 2024, 4, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zu, Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Maity, A.; Sun, J.; Li, M.; Jin, X.; Yu, J. CD-YOLO-Based deep learning method for weed detection in vegetables. Weed Sci. 2025, 73, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Sun, Y.; Che, J.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y. A novel deep learning-based method for detection of weeds in vegetables. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Shu, L.; Xie, Q.; Song, M.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Ni, J. Precision weed detection in wheat fields for agriculture 4.0: A survey of enabling technologies, methods, and research challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K. Auxin herbicides: Current status of mechanism and mode of action. Pest Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2010, 66, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, P.E.; Yu, J.; Raymer, P.L.; Chen, Z. First report of ACCase-resistant goosegrass (Eleusine indica) in the United States. Weed Sci. 2016, 64, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; McCullough, P.E.; Czarnota, M.A. First report of acetyl-CoA carboxylase–resistant southern crabgrass (Digitaria ciliaris) in the united states. Weed Technol. 2017, 31, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. Shufflenet: An extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6848–6856. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1580–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.-h.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.-H.; Chan, S.-H.G. Run, don’t walk: Chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Chengao, Z.; Lu, L.; Yan, Y.; Jun, W.; Wei, X.; Ke, X.; Jun, T. Star-YOLO: A lightweight and efficient model for weed detection in cotton fields using advanced YOLOv8 improvements. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnetv2: Smaller models and faster training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 10096–10106. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv1 to YOLOv10: The fastest and most accurate real-time object detection systems. APSIPA Trans. Signal Inf. Process. 2024, 13, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Gao, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H. Recognition of the behaviors of dairy cows by an improved YOLO. Intell. Robot. 2024, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Jin, X.; Li, A.; Yu, J. Efficient crop segmentation net and novel weed detection method. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 161, 127367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, G.F.; Young, B.G.; Dayan, F.E.; Streibig, J.C.; Takano, H.K.; Merotto, A., Jr.; Avila, L.A. Herbicide mixtures: Interactions and modeling. Adv. Weed Sci. 2023, 40, e020220051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero-Alvarado, R.; Appleby, A.P.; Armstrong, D.J. Antagonism of haloxyfop activity in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) by dicamba and bentazon. Weed Sci. 1991, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipe, J.B.; de Oliveira Júnior, R.S.; Constantin, J.; Braga, G.; Braz, P.; Takano, H.K.; Biffe, D.F. Interaction of dicamba or 2,4-D with acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibiting herbicides to control fleabane and sourgrass. J. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2021, 3, 220–237. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, L.H.; Ferguson, J.C.; Brown-Johnson, A.E.; Reynolds, D.B.; Tseng, T.-M.; Lowe, J.W. Reduced herbicide antagonism of grass weed control through spray application technique. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Lu, Y.; Xu, J. Weed database development: An updated survey of public weed datasets and cross-season weed detection adaptation. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krestenitis, M.; Raptis, E.K.; Kapoutsis, A.C.; Ioannidis, K.; Kosmatopoulos, E.B.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. CoFly-WeedDB: A UAV image dataset for weed detection and species identification. Data Brief 2022, 45, 108575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameski, P.; Zdravevski, E.; Trajkovik, V.; Kulakov, A. Weed detection dataset with RGB images taken under variable light conditions. In Proceedings of the ICT Innovations 2017: Data-Driven Innovation. 9th International Conference, ICT Innovations 2017, Skopje, Macedonia, 18–23 September 2017; Proceedings 9. pp. 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Liu, T.; Yang, Z.; Xie, J.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Hong, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y. Precision weed control using a smart sprayer in dormant bermudagrass turf. Crop Prot. 2023, 172, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.