Crop Growth and Yield in Three-Crop Mixtures and Sole Stands in an Organic System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

2.2. Sampling and Measurements

2.3. Calculations and Indices

2.4. Weather Conditions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

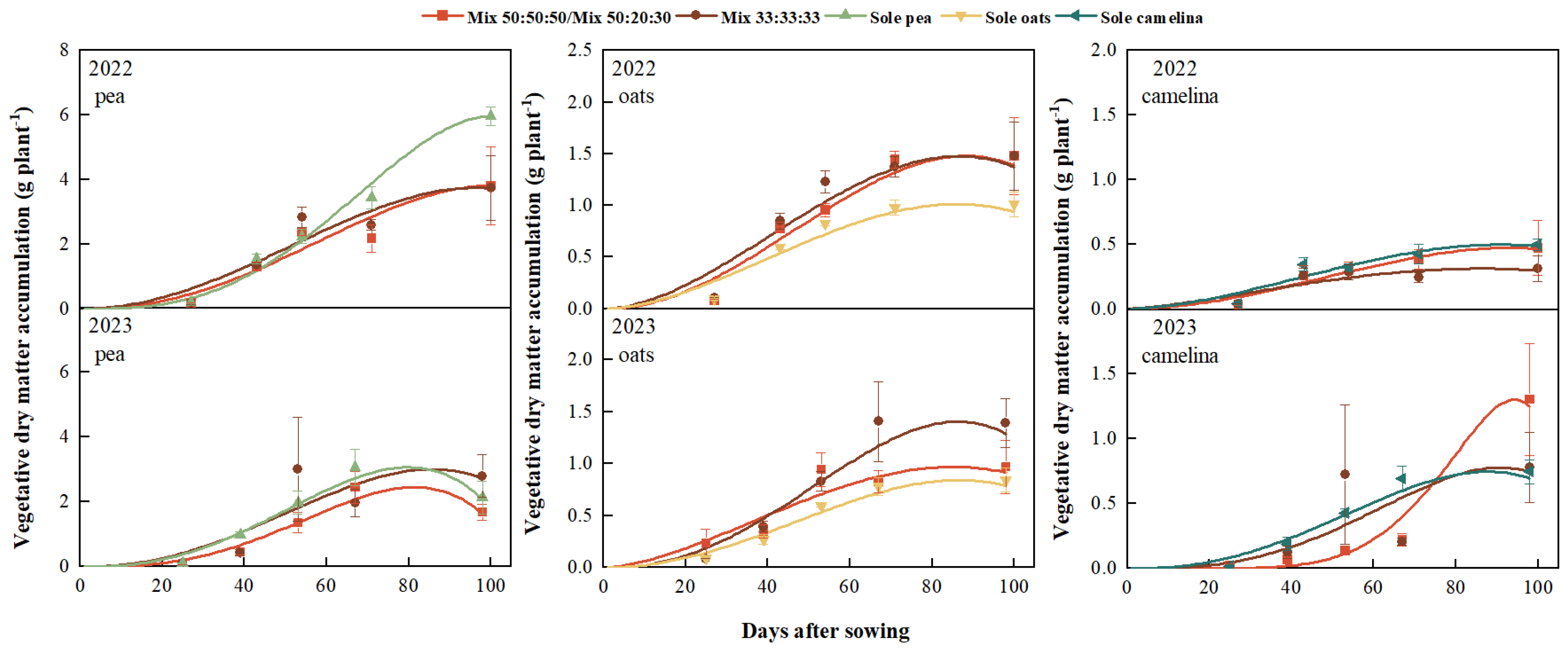

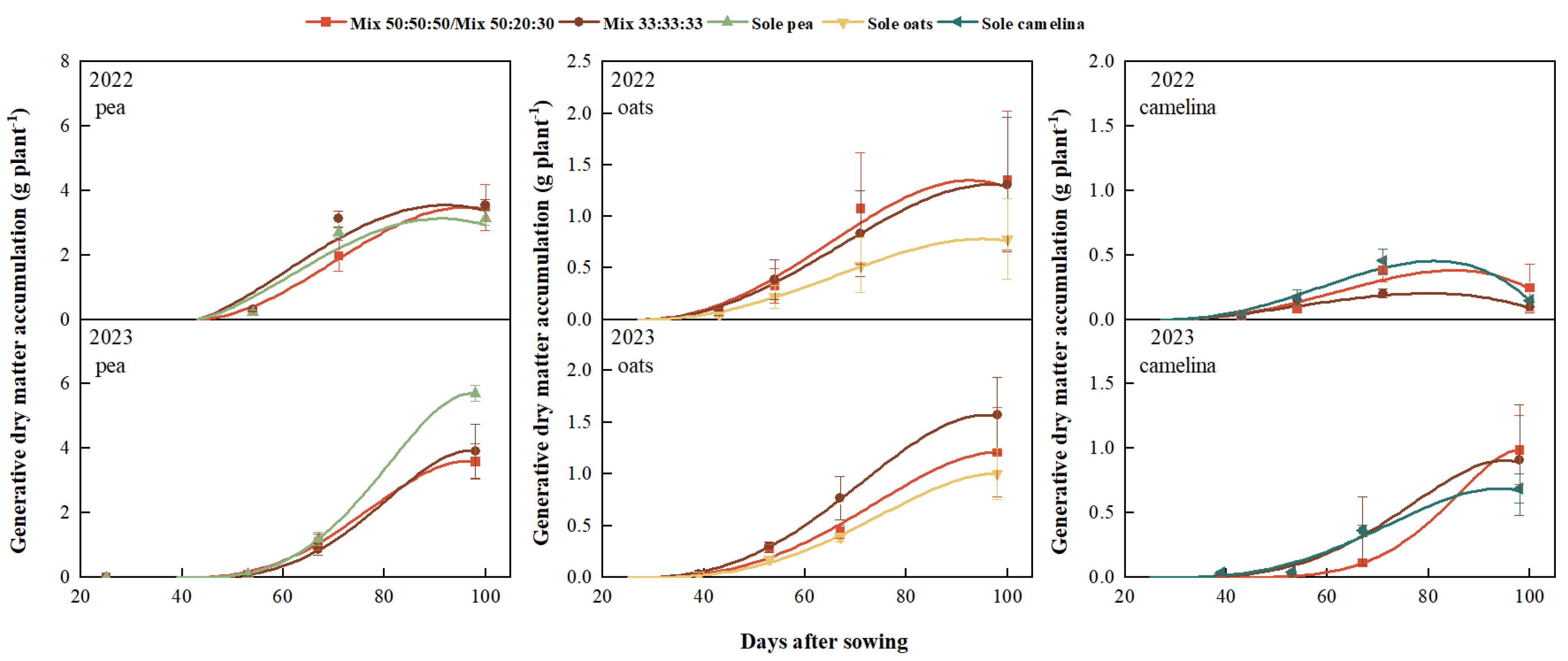

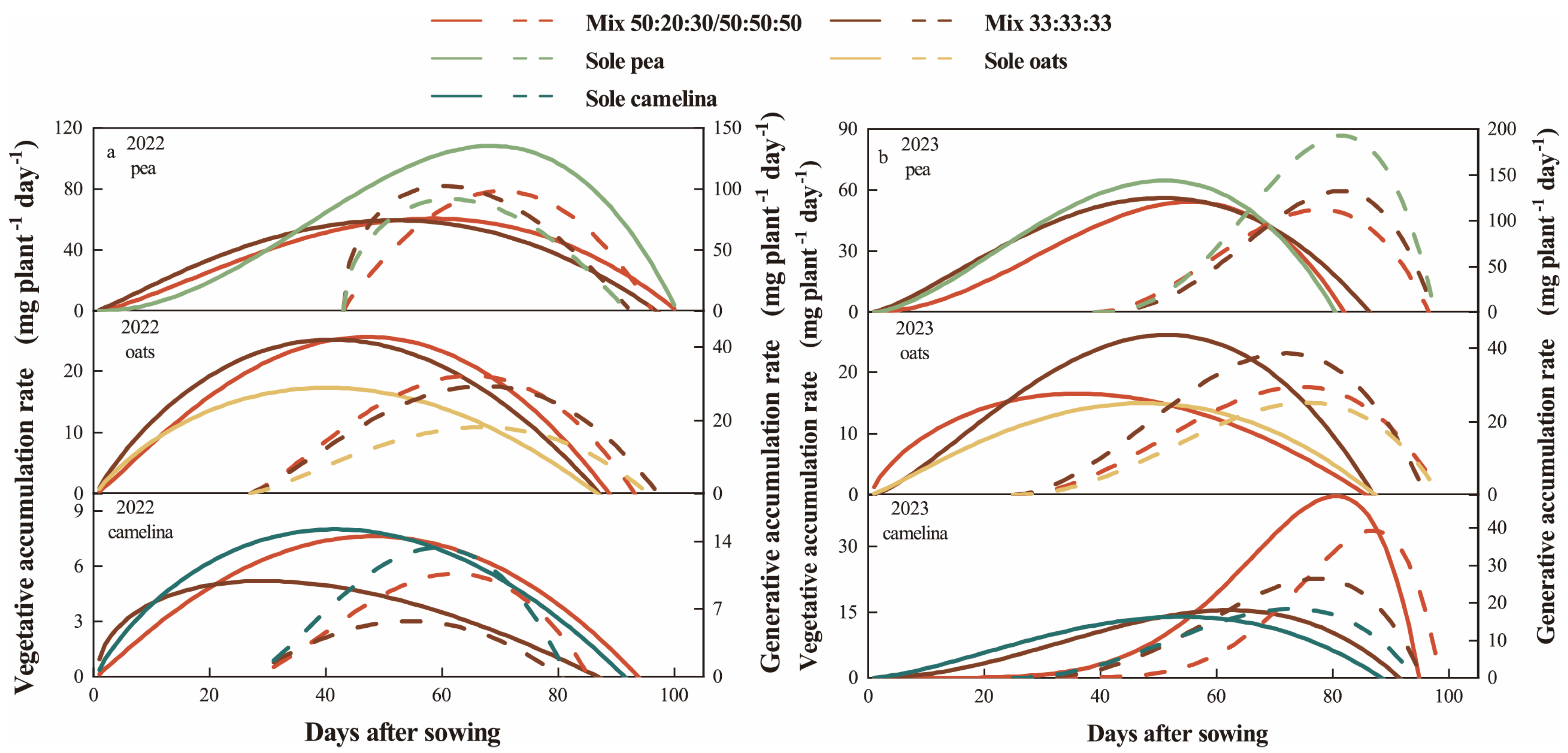

3.1. Dry Matter Accumulation

3.2. Seed Yield and Seed Quality

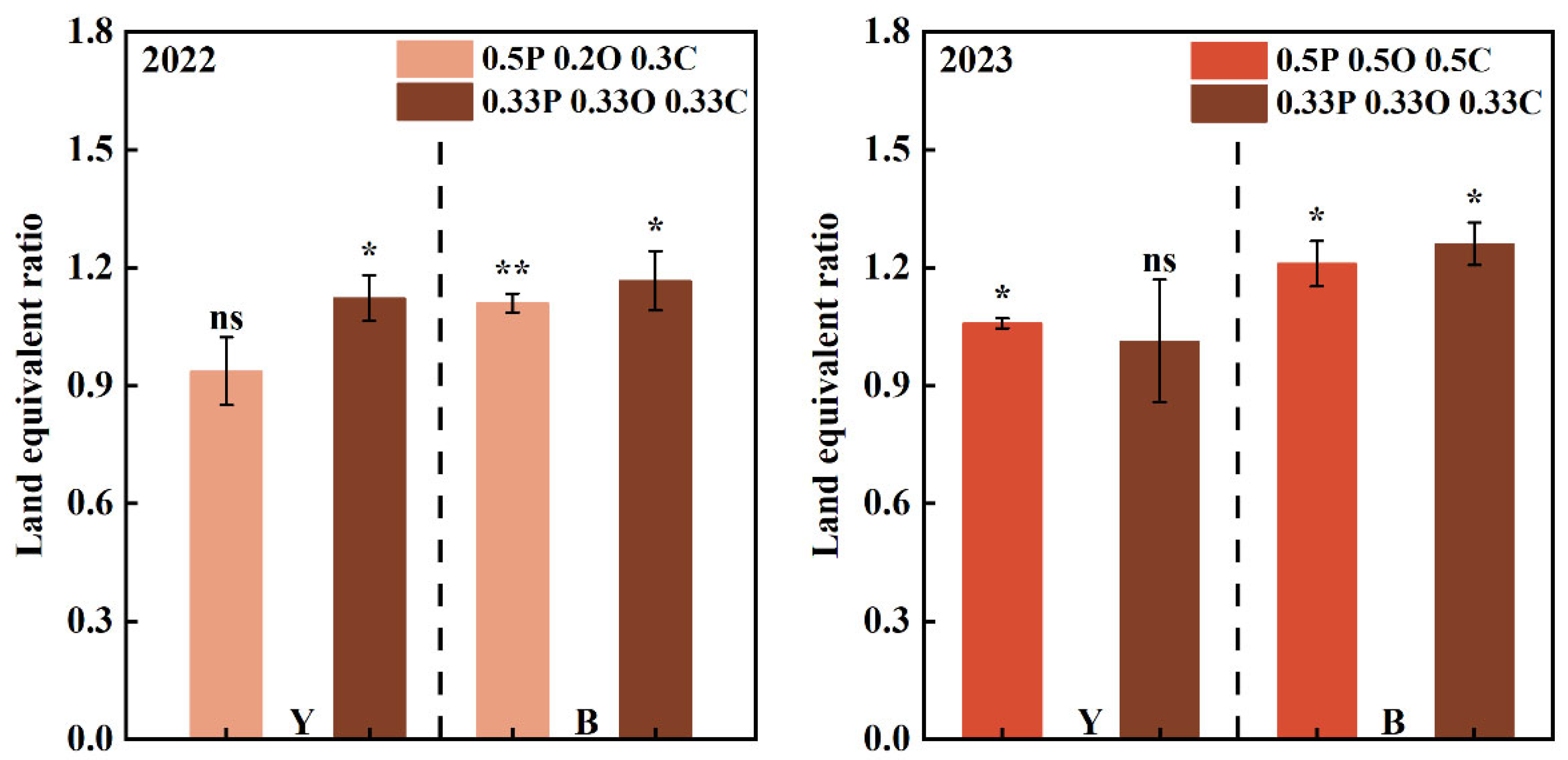

3.3. Land Equivalent Ratio and Relative Interaction Index of Crop Mixtures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Derpsch, R.; Kassam, A.; Reicosky, D.; Friedrich, T.; Calegari, A.; Basch, G.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, E.; dos Santos, D.R. Nature’s laws of declining soil productivity and Conservation Agriculture. Soil Secur. 2024, 14, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, J.; Gómez-Limón, J.A.; Arriaza, M. Conversion to organic farming: Does it change the economic and environmental performance of fruit farms? Ecol. Econ. 2024, 220, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Economic; Social Committee. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Policy Framework for Climate and Energy in the Period from 2020 to 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Grzelak, A.; Staniszewski, J. Relative return on assets in farms and its economic and environmental drivers. Perspective of the European Union and the Polish region Wielkopolska. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S.; Maxwell, B.D. Optimizing crop seeding rates on organic grain farms using on farm precision experimentation. Field Crops Res. 2024, 318, 109593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Yao, X.; Wu, K.; Guo, A.; Yao, Y. Response of the rhizosphere soil microbial diversity to different nitrogen and phosphorus application rates in a hulless barley and pea mixed-cropping system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 195, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintl, A.; Smeringai, J.; Sobotková, J.; Huňady, I.; Brtnický, M.; Hammerschmiedt, T.; Elbl, J. Mixed cropping system of maize and bean as a local source of N-substances for the nutrition of farm animals. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 154, 127059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chai, Q.; Yin, W.; Guo, Y.; Fan, Z.; Hu, F.; Wang, Q.; Mao, S. Mixed cropping green manure can simultaneously improve nutrition production and quality of spring wheat grain under reduced chemical nitrogen supply. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerquist, E.; Vogeler, I.; Kumar, U.; Bergkvist, G.; Lana, M.; Watson, C.A.; Parsons, D. Assessing the effect of intercropped leguminous service crops on main crops and soil processes using APSIM NG. Agric. Syst. 2024, 216, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Liu, D.L.; Li, G.; Wang, B.; Anwar, M.R.; Crean, J.; Lines-Kelly, R.; Yu, Q. Incorporating grain legumes in cereal-based cropping systems to improve profitability in southern New South Wales, Australia. Agric. Syst. 2017, 154, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuperus, F.; Ozinga, W.A.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A.; Croijmans, L.; Rossing, W.A.H.; van Apeldoorn, D.F. Effects of field-level strip and mixed cropping on aerial arthropod and arable flora communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 354, 108568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguizamón, Y.; Goldenberg, M.G.; Jobbágy, E.; Whitworth-Hulse, J.I.; Satorre, E.; Paolini, M.; Martini, G.; Micheloud, J.R.; Garibaldi, L.A. Crop diversity enhances drought tolerance and reduces environmental impact in commodity crops. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 385, 109585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.S.; Rasmussen, J.; Eriksen, J. Grassland carbon sequestration and emissions following cultivation in a mixed crop rotation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 153, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithourgidis, A.S.; Vlachostergios, D.N.; Dordas, C.A.; Damalas, C.A. Dry matter yield, nitrogen content, and competition in pea–cereal intercropping systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 34, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enesi, R.O.; Mbanyele, V.; Shaw, L.; Holzapfel, C.; Nybo, B.; Gorim, L.Y. Pea-oats intercropping: Agronomy and the benefits of including oats as a companion crop. Field Crops Res. 2025, 326, 109863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoad, S.P.; Russell, G.; Lucas, M.E.; Bingham, I.J. The management of wheat, barley, and oat root systems. Adv. Agron. 2001, 74, 193–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronle, A.; Heß, J.; Böhm, H. Weed suppressive ability in sole and intercrops of pea and oat and its interaction with ploughing depth and crop interference in organic farming. Org. Agric. 2015, 5, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C.; Rossi, A.; Angelini, L.G.; Villalba, R.G.; Moreno, D.A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Tavarini, S. Effect of environmental conditions on seed yield and metabolomic profile of camelina (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) through on farm multilocation trials. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzuini, S.; Zanetti, F.; Alberghini, B.; Leon, P.; Prieto, J.; Herreras Yambanis, Y.; Trabelsi, I.; Hannachi, A.; Udupa, S.; Monti, A. Assessing the productivity potential of camelina (Camelina sativa L. Crantz) in the Mediterranean basin: Results from multi-year and multi-location trials in Europe and Africa. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Staden, J. South African Association of Botanists—Annual Meeting 2011. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 510–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, E.; Zanetti, F.; Ferioli, F.; Facciolla, E.; Monti, A. Camelina intercropping with pulses a sustainable approach for land competition between food and non-food crops. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselá, A.; Duongová, L.; Münzbergová, Z. Plant origin and trade-off between generative and vegetative reproduction determine germination behaviour of a dominant grass species along climatic gradients. Flora 2022, 297, 152177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.J.; Cano, M.G.; Fanello, D.D.; Tambussi, E.A.; Guiamet, J.J. Extended photoperiods after flowering increase the rate of dry matter production and nitrogen assimilation in mid maturing soybean cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2021, 265, 108104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono-and Dicotyledonous Plants; Blackwell Wissenschafts: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Kropff, M.J.; McLaren, G.; Visperas, R.M. A nonlinear model for crop development as a function of temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 77, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas, C.; Ordiales, R.; Pugnaire, F.I. Measuring plant interactions: A new comparative index. Ecology 2004, 85, 2682–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, R.; Willey, R.W. The Concept of a ‘Land Equivalent Ratio’ and Advantages in Yields from Intercropping. Exp. Agric. 1980, 16, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corre-Hellou, G.; Brisson, N.; Launay, M.; Fustec, J.; Crozat, Y. Effect of root depth penetration on soil nitrogen competitive interactions and dry matter production in pea–barley intercrops given different soil nitrogen supplies. Field Crops Res. 2007, 103, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begam, A.; Pramanick, M.; Dutta, S.; Paramanik, B.; Dutta, G.; Patra, P.S.; Kundu, A.; Biswas, A. Inter-cropping patterns and nutrient management effects on maize growth, yield and quality. Field Crops Res. 2024, 310, 109363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, R.J.; Otegui, M.E.; Collino, D.J.; Dardanelli, J.L. Environmental effects on seed yield determination of irrigated peanut crops: Links with radiation use efficiency and crop growth rate. Field Crops Res. 2007, 103, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Mauromicale, G. Crop Allelopathy for Sustainable Weed Management in Agroecosystems: Knowing the Present with a View to the Future. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshev, N.; Marcheva, M.; Zorovski, P.; Stanchev, G.; Yordanov, Y.; Popov, V.H. Growth, development, and weed suppression capacity of Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz grown as sole and mixed crop with legumes: Preliminary results. Sci. Papers Ser. A Agron. 2023, 66, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Ambus, P.; Jensen, E.S. Interspecific competition, N use and interference with weeds in pea–barley intercropping. Field Crops Res. 2001, 70, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannoura, R.; Joergensen, R.G.; Bruns, C. Organic fertilizer effects on growth, crop yield, and soil microbial biomass indices in sole and intercropped peas and oats under organic farming conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 52, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, J.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Hu, H. Physiological diversity of orchids. Plant Divers. 2018, 40, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremer, E.; Ellert, B.H.; Pauly, D.; Greer, K.J. Variation in over-yielding of pulse-oilseed intercrops. Field Crops Res. 2024, 305, 109190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Hu, T.; Lu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J. Reduced irrigation combined with nitrification inhibitor enhances grain yield and water-nitrogen use efficiency of winter wheat by improving the physiological characteristics. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 23, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordas, C.A.; Vlachostergios, D.N.; Lithourgidis, A.S. Growth dynamics and agronomic-economic benefits of pea–oat and pea–barley intercrops. Crop Pasture Sci. 2012, 63, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo-Foo, K.; Liu, K.; Knight, J.D. Enhanced biological nitrogen fixation in pea-canola intercrops quantified using 15N isotopic analysis. Field Crops Res. 2026, 337, 110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Elkin, W.; Carkner, M.; Entz, M.H.; Beres, B. Intercropping organic field peas with barley, oats, and mustard improves weed control but has variable effects on grain yield and net returns. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 102, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.K.; Minkey, D.; Desbiolles, J.; Clarke, G.; Allen, R.; Noack, S.; Schmitt, S.; Amougis, A. Responses to precision planting in canola and grain legume crops. Field Crops Res. 2024, 315, 109451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lv, Z.-C.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, H.-Z.; Chen, M.; Kim, D.-S.; Lim, S.-H.; Yan, X.; Zhang, C.-J. Agronomic performance of camelina [Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz] intercropped in temperate orchard-based agroforestry systems in eastern China. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 170, 127747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugschwandtner, R.W.; Kaul, H.-P. Sowing ratio and N fertilization affect yield and yield components of oat and pea in intercrops. Field Crops Res. 2014, 155, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ayuso, M.; Franco-Luesma, S.; Lafuente, V.; Bielsa, A.; Álvaro-Fuentes, J. Cereal-maize vs. legume-maize double-cropping: Impact on crop productivity and nitrogen dynamics under flood-irrigated Mediterranean conditions. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature, °C | Precipitation, mm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | 2022 | 2023 | 1991–2020 | 2022 | 2023 | 1991–2020 |

| May | 13.1 | 13.2 | 10.2 | 39 | 16 | 40 |

| June | 17.7 | 17.0 | 14.5 | 33 | 46 | 65 |

| July | 18.2 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 55 | 92 | 70 |

| August | 18.6 | 16.7 | 15.5 | 44 | 225 | 75 |

| September | 8.6 | 14.3 | 10.5 | 37 | 72 | 54 |

| October | 7.6 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 9 | 62 | 67 |

| Estimates for Vegetative Growth | Estimates for Generative Growth | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Stand | Species | Wmax | tm | te | ra | rm | R2 | Tmax | Tm | Te | Ra | Rm | R2 |

| 2022 | |||||||||||||

| Mixture 50:20:30 | Pea | 1.48 | 88.08 | 46.91 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 1.35 | 66.72 | 38.67 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| Oats | 3.81 | 99.93 | 58.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.89 | 3.49 | 53.85 | 27.87 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.99 | |

| Camelina | 0.47 | 93.03 | 48.07 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.38 | 58.94 | 35.83 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.92 | |

| Mixture 33:33:33 | Pea | 1.48 | 86.96 | 41.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.9 | 1.31 | 70.76 | 40.78 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| Oats | 3.75 | 95.92 | 51.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.88 | 3.56 | 49.11 | 17.93 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.93 | |

| Camelina | 0.31 | 86.01 | 29.05 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 53.98 | 28 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.9 | |

| Sole crop | Pea | 1.01 | 86.09 | 39.98 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 69.11 | 40.38 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.99 |

| Oats | 5.95 | 100.09 | 68.05 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.98 | 3.14 | 49.4 | 18.91 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.94 | |

| Camelina | 0.5 | 90.93 | 41.03 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 55.13 | 32.76 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.97 | |

| Estimates for Vegetative Growth | Estimates for Generative Growth | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Stand | Species | Wmax | tm | te | ra | rm | R2 | Tmax | Tm | Te | Ra | Rm | R2 |

| 2023 | |||||||||||||

| Mixture 50:20:30 | Pea | 0.97 | 85.09 | 36.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.83 | 1.21 | 73.65 | 50.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| Oats | 2.45 | 81.09 | 54.93 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 3.59 | 58.08 | 39.36 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.99 | |

| Camelina | 1.3 | 94 | 79.91 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 73.99 | 62.43 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.99 | |

| Mixture 33:33:33 | Pea | 1.4 | 85.93 | 50.91 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 1.57 | 71.54 | 47.41 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.99 |

| Oats | 3.01 | 86.06 | 49.96 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.69 | 3.92 | 58.89 | 42.71 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.99 | |

| Camelina | 0.78 | 90.98 | 61.92 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.9 | 70.99 | 52.82 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 | |

| Sole crop | Pea | 0.84 | 87.06 | 47.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 1 | 74.06 | 51.08 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| Oats | 3.07 | 80.08 | 50.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.96 | 5.7 | 47.13 | 25.69 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.99 | |

| Camelina | 0.74 | 88.09 | 53.96 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 69.76 | 48.55 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.98 | |

| 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea | Oats | Camelina | ||||

| Crop Stand | V-R | V/R | V-R | V/R | V-R | V/R |

| Mixture 50:20:30/50:50:50 | 0.32 b | 1.06 b | 0.13 a | 1.24 a | 0.22 a | 3.55 a |

| Mixture 33:33:33 | 0.19 b | 1.04 b | 0.17 a | 1.61 a | 0.22 a | 3.66 a |

| Sole crop | 2.82 a | 1.91 a | 0.23 a | 1.41 a | 0.34 a | 3.30 a |

| p-value | 0.046 | 0.016 | 0.978 | 0.83 | 0.232 | 0.901 |

| 2023 | ||||||

| Pea | Oats | Camelina | ||||

| Crop stand | V-R | V/R | V-R | V/R | V-R | V/R |

| Mixture 50:20:30/50:50:50 | −1.91 a | 0.48 ab | −0.24 a | 0.90 a | 0.32 a | 1.23 a |

| Mixture 33:33:33 | −1.13 a | 0.71 a | −0.18 a | 1.07 a | −0.13 a | 1.00 a |

| Sole crop | −3.56 b | 0.38 b | −0.16 a | 1.04 a | 0.06 a | 1.11 a |

| p-value | 0.013 | 0.044 | 0.98 | 0.916 | 0.174 | 0.324 |

| 2022 | 2023 | p-Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Species | Mixture 50:20:30 | Mixture 33:33:33 | Sole Crop | Mixture 50:50:50 | Mixture 33:33:33 | Sole Crop | Year (Y), df = x | Crop Stand (CS), df = x | Y x CS, df = x |

| Seed yield, g m−2 | Pea | 809 b | 711 b | 1824 a | 540 b | 704 b | 3450 a | 0.051 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Oats | 1320 c | 2192 b | 4078 a | 3491 ab | 2903 b | 4143 a | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | |

| Camelina | 107 b | 109 b | 606 a | 44 b | 812 b | 749 a | 0.771 | <0.001 | 0.329 | |

| 1000-seed weight, g | Pea | 293.94 b | 296.18 b | 309.83 a | 203.03 a | 201.88 a | 221.84 a | <0.001 | 0.044 | 0.909 |

| Oats | 47.20 a | 47.80 a | 48.05 a | 40.04 a | 38.75 a | 39.31 a | <0.001 | 0.873 | 0.496 | |

| Camelina | 1.20 a | 1.22 a | 1.15 a | 1.11 a | 1.07 ab | 1.00 b | <0.001 | 0.026 | 0.5 | |

| TFC, g kg−1 | Camelina | 392.4 a | 403.5 a | 422.3 a | 343.3 b | 325.1 b | 398.2 a | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.102 |

| TW, kg hl−1 | Oats | 49 a | 50 a | 50 a | 48 a | 47 a | 48 a | 0.017 | 0.992 | 0.614 |

| Protein content, g kg−1 | Pea | 0.25 a | 0.25 a | 0.25 a | 0.31 a | 0.30 ab | 0.29 b | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.074 |

| Oats | 0.10 a | 0.10 a | 0.09 b | 0.11 a | 0.11 a | 0.10 a | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.671 | |

| Camelina | 0.21 a | 0.22 a | 0.20 a | 0.21 b | 0.21 b | 0.23 a | 0.028 | 0.064 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, C.; Koli, I.; Samiraja, S.; Juvonen, S.; Alakukku, L.; Simojoki, A.; Mäkelä, P.S.A. Crop Growth and Yield in Three-Crop Mixtures and Sole Stands in an Organic System. Agronomy 2026, 16, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010094

Xiao C, Koli I, Samiraja S, Juvonen S, Alakukku L, Simojoki A, Mäkelä PSA. Crop Growth and Yield in Three-Crop Mixtures and Sole Stands in an Organic System. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Chao, Ilja Koli, Shiromi Samiraja, Saku Juvonen, Laura Alakukku, Asko Simojoki, and Pirjo S. A. Mäkelä. 2026. "Crop Growth and Yield in Three-Crop Mixtures and Sole Stands in an Organic System" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010094

APA StyleXiao, C., Koli, I., Samiraja, S., Juvonen, S., Alakukku, L., Simojoki, A., & Mäkelä, P. S. A. (2026). Crop Growth and Yield in Three-Crop Mixtures and Sole Stands in an Organic System. Agronomy, 16(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010094