Abstract

Sometimes, crop breeding varieties demonstrate high resistance to target insects under laboratory conditions but exhibit significantly low resistance in the field. This research aimed to explain this phenomenon based on inter-species interactions among insects, as herbivory by one insect species can trigger physiological changes in plants that enhance their attraction to other insect species. The striped stem borer (SSB), Chilo suppressalis (Walker), and the brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens (Stål), are pests of rice (Oryza sativa L.) that cause major losses in grain production. In this study, we investigated BPH performance and behavior on the planthopper-resistant rice variety “Mudgo” with pre-feeding of SSB. BPHs showed better growth and development, as well as feeding behavior, on SSB-damaged plants compared to undamaged plants. Then, gene expression and phytohormone analysis revealed that jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis was induced by SSB feeding. The JA pathway is a central defense signaling hub in rice responding to chewing herbivores like SSB; however, our findings reveal that its induction can have contrasting ecological consequences, inadvertently reducing resistance to a subsequent piercing-sucking pest (BPH). Finally, we discovered that volatile emissions induced by SSB damage attracted BPH and benefited its development. In summary, we found that JA biosynthesis triggered by SSB herbivory played a vital role in rice defense against BPH. This provides insight into the molecular and biochemical mechanisms underlying BPH preferences for SSB-damaged rice plants. Our study emphasizes the crucial role of inter-species interactions in enhancing host plant resistance to insect pests and evaluating germplasm resistance. These findings can serve as a basis for controlling BPH.

1. Introduction

New breeds of agricultural crops show high resistance to insects in the laboratory; however, they sometimes show low resistance in the field. This research used rice and two insect pest species as an example to understand this phenomenon. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) serves as a primary food source for over fifty percent of the global population [1]. However, yields are frequently reduced by various species of herbivorous insects belonging to different feeding guilds [2]. Lepidopteran stem borers are major pests in all rice ecosystems, with the striped stem borer (SSB), Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) being one of the most destructive in temperate regions in Asia [3]. SSB is a chewing herbivore whose larvae bore into and feed within rice stems, causing damage to plants such as withered sheaths, weak stems, “dead hearts,” and “whiteheads” (empty panicles with a few filled grains). This pest is particularly harmful in China due to the widespread use of hybrid rice varieties [4]. Another important pest of rice is the brown planthopper (BPH) Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) (Hemiptera: Delphacidae), for which its outbreaks in China have increased since the adoption of hybrid rice cultivars in the 1980s [5]. BPH is a phloem-feeding insect that sucks the phloem sap from the base of the tillers, causing a reduction in growth, vigor, and the number of productive tillers. BPH can infest rice plants at all stages of growth, and its feeding causes yellowing of the leaves and, in severe cases, can lead to plant death. Such damage results in significant losses to farmers yearly [6,7]. Therefore, developing insect-resistant rice varieties and pest control strategies has become a crucial focus of rice breeding and production.

Recently, two genetically modified rice plants have been developed to control populations of the two pests: One harbors an overexpressed Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Cry protein to control SSB [8], while the other carries planthopper-resistant genes, such as Bph1, Bph2, and Bph3, to control BPH [9]. Studies have been conducted to understand the mechanisms underlying each rice variety’s resistance to SSB and BPH [6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], but a new variety has shown mixed results when tested in both lab and field settings. This has raised the question of whether non-target insects affect a plant’s resistance to targeted insects, making it essential to assess interspecific insect interactions when evaluating rice germplasm resistance.

Mutually beneficial interactions among herbivorous insect species have been established [17,18]. BPH has a strong preference for transgenic Bt rice plants that have been pre-infested by SSB [19]. BPH is insensitive to the Bt insecticidal Cry protein, but its population diminishes when it spreads to a neighboring non-Bt rice field from a Bt rice field due to the significantly reduced activity of the targeted SSB. This led to the concept of “ecological resistance” of Bt rice to non-target insects. This interaction involving two different insect species may be highly significant in evaluating germplasm resistance. The objectives of this study were to answer the following two questions: (1) Will newly-introduced resistance traits in rice varieties to BPH be reduced by SSB damage? (2) How do rice plants mediate the physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms underlying BPH preference for SSB-damaged rice plants?

For our study, we selected the rice type “Mudgo”, which has been identified as resistant to BPH [20,21,22]. We aimed to uncover the physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms that influence BPH’s feeding habits. We began by conducting a series of preference tests to confirm that BPH prefers SSB-damaged rice plants over undamaged ones. We also evaluated whether SSB damage to rice caused any changes in the expression of the Bph1 gene in rice. To gain further insights, we analyzed the transcriptome and phytohormone levels in rice to identify any alterations in gene expression and JA, JA-Ile, SA, and ABA metabolite levels in response to SSB feeding. Additionally, we analyzed the volatile profile of SSB-damaged stems. Our metabolomic analyses revealed changes in jasmonic acid signaling pathway metabolites, and BPH behaviorally responded to rice volatiles. Overall, our study, which integrated transcriptomes with metabolic profiles of phytohormones and volatiles of a resistant rice variety, revealed how SSB damage reduces resistance to subsequent feeding by the brown planthopper in rice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Growth

For this study, we selected two types of rice: Mudgo, which has high resistance to BPH, and TN1, which is highly susceptible to BPH. We pre-germinated the seeds of both types of rice in water for 2–3 days, changing the water twice a day. After this, we planted the seeds in a mixture of peat and vermiculite (3:1) and waited until the seedlings were 15 days old. We then transplanted each seedling into an individual plastic pot (diameter of 8 cm and height of 10 cm). After 40–50 days of growth and at the jointing stage, we used the plants for experiments. Throughout the process, we cultivated all plants in a greenhouse without pesticides, maintaining a temperature of 27 ± 3 °C, relative humidity of 65 ± 10%, and a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle.

2.2. Insect Colonies

Specimens of BPH were maintained on the conventional rice plant TN1 for >20 generations. In addition, specimens of SSB were introduced and maintained on an artificial diet for >70 generations [23]. Both insect colonies were kept at 27 ± 2 °C, 70–80% RH, and a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark cycle at the Anyang Institute of Technology, China.

2.3. Behavioral and Biological Characteristics Studies of Caterpillars and Planthoppers

2.3.1. Insect Bioassay

Forty-eight hours after the specimen plants were transferred to a greenhouse growth cabinet for experiments (27 ± 1 °C, 75 ± 5% RH, 16 L: 8 D photoperiod), the Mudgo or TN1 rice plants were individually infested with one 3rd-instar larva of SSB that had been starved for at least 3 h. After three days, visible damage caused by SSB caterpillars was observed, as indicated by drillings into the stems. These plants were classified as “damaged” treatment throughout the experiment. Plants that remained undamaged during the experiment were referred to as the “healthy” treatment. The caterpillars remained on the plants for the full duration of the experiments.

2.3.2. Host Preference of Planthoppers

To study the BPH preference of choice in host plants, we compared four pairs of rice hosts infested with BPH using the “H” equipment described by Wang et al., 2018 [19]. The four plant pairs included the following: (i) healthy Mudgo rice plants versus healthy TN1 rice plants; (ii) damaged Mudgo rice plants versus healthy Mudgo rice plants; (iii) damaged TN1 rice plants versus healthy TN1 rice plants; (iv) damaged Mudgo rice plants versus damaged TN1 rice plants. For each test, the main stems of the two rice plants were contained in a cylindrical plastic tube (diameter of 8.0 cm and length of 19.0 cm). Then, twenty 3rd instars of BPH were released in the middle of the “H” equipment, and the number of planthoppers per plant was recorded for seven consecutive days. Each paired-choice test was repeated 20–23 times (replicates).

2.3.3. Bioassays of Planthoppers

To study BPH development in healthy or damaged TN1 or Mudgo rice, we conducted two bioassays. The first bioassay was carried out to determine the survival rate of BPH. The second bioassay was performed to establish other BPH life parameters such as rate of development, weight and body length, sex ratio, and brachypterous ratios. In this experiment, damaged and healthy rice plants were treated as described above in the choice study. After the 48 h wait following plant transfer to the greenhouse, yellow leaves were removed, and the main stem of a single living plant from each treatment was enclosed in a plastic cylindrical tube (diameter of 8.0 cm; height of 9.5 cm). Lastly, a single first-instar BPH nymph was introduced into the cylindrical tube. Thereafter, we checked the BPH every day, removing the molting and recording life parameters until the adult stage. Alive adults were then weighed on an electronic balance (CPA2250, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany, readability = 0.01 mg) and photographed with a digital camera (DP73, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) mounted on a microscope (SZX7, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to determine their body length. The procedures for both bioassays were identical. Each bioassay test was repeated 55–140 times (in replicates).

2.3.4. Monitoring of BPH Feeding Behavior

We selected adult brachypterous females for this experiment. The electrical penetration graph (EPG) technique was used to monitor the feeding behavior recorded using a GIGA-8 DC EPG (Wageningen University) amplifier system [24,25]. To improve monitoring, we first slowed insect activity by cooling BPH to −20 °C for 60 s and then quickly and carefully connected a 3 cm length of 18.5 mm diameter gold wire with conductive silver glue to their dorsum. Following a 2 h starvation period, the BPH with gold wire was attached to a DC-EPG amplifier. To complete the electronic circuit, they were also connected to the stem area of each rice plant, 5–8 cm above the soil. Throughout the experiment, the devices were placed around a Faraday cage to encourage clear electrical signals. BPH behavior was recorded for six hours continuously with 26–33 replicates per treatment. Data gathering, data analysis, and calculated total time of each waveform were attained using the Stylet + d Software (Version: v01.34 (08-04-2020)/B33, W.F. Tjallingii, Wageningen, the Netherlands).

2.3.5. Quantification of Bph1 Gene Expression

Specific primers designed using Beacon Designer (Premier Biosoft, version 7.0) and synthesized by Sangon Biotech were used to measure the change in Bph1 gene [22] expression in healthy Mudgo or SSB-damaged rice. For the negative control, the same method above was used on TN1. Information on primer sequences is shown in Table S1. The housekeeping gene, ubiquitin 5 [26], was used as an internal control in quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The plant stem samples were collected from SSB-damaged rice at different time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to reverse transcribe 500 ng total RNA, and DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for digestion. Then, the cDNA 50X was diluted for qPCR. The qRT-PCR reaction was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq Ready Mix with ROX reference dye (Takara Biotech, Kyoto, Japan) and an ABI life Real-time PCR Q6 instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). PCR amplification program reactions were all carried out under the following conditions: one cycle at 30 s at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 34 s at 60 °C. Cycle threshold (Ct) values for the ubiquitin 5 gene were used to normalize the expression patterns of the analyzed genes from 0 h and other time points. The relative fold changes of gene expression were calculated using the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method [27].

2.4. Transcriptome Analyses

2.4.1. RNA Extraction, Library Preparation, RNA-Sequencing, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Potted Mudgo rice plants were housed in a cylindrical plastic tube and infested with one 3rd-instar larva of SSB per plant. The larvae were starved for 3 h before they were caged with the rice plants. After 72 h, the main rice stems, 8–10 cm around the area damaged by the larvae, were cut off and split in the middle to take out SSB. The control healthy rice was also housed in a cylindrical plastic tube, but without SSB, and harvested at the same time. All plant samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for later analyses. Three replicate samples were collected and used for transcriptome analyses.

Total RNA was extracted from the rice stem samples using a TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA degradation and contamination were validated using electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel with 180 V voltage for 16 min, and concentrations were quantified using the NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, Calabasas, CA, USA). An RNA library was constructed with 3 μg of RNA per sample using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Index codes were added to attribute sequences for each sample. The library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq platform (Illumina Hiseq 4000; Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and 125–150 bp paired-end reads were generated.

To validate the results of RNA-seq, 17 genes were selected based on the signaling of phytohormones, primary metabolism, and secondary metabolism for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses. The plant stem samples for qRT-PCR were collected from the same split stem, which was sampled for RNA-seq experiments, and by the same method.

2.4.2. RNA-Sequencing Data Analysis

The transcriptome data analysis was conducted according to the description by Liu et al., 2016 [28]. Differential expression analysis of damaged and healthy groups was performed using the DESeq R package (1.18.0) [29] and filtered with the following thresholds: p-value < 0.05 and |log2 (fold change)| ≥ 2 using Benjamini and Hochberg’s approach for controlling the false discovery rate [30].

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was carried out with the GOseq R package, in which gene length bias was corrected [31]. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of the DEGs was conducted using the clusterProfiler package in R and KOBAS software (version 3.0) to test the statistical enrichment of differential expression genes in KEGG pathways [32].

2.5. Quantification of Phytohormones and Related Gene Expression

To measure the amount of JA, JA-Ile, SA, and ABA phytohormones, tissue was collected from rice stems at different time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h). The phytohormones were extracted and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS, LCMS-8040 system, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) following the method of Wu et al., 2007 [33]. Each phytohormone was quantified by comparing its peak area with the peak area of its respective internal standard. Four replicate stem samples for each time point were analyzed.

To further verify the genes that were expressed in response to SSB feeding, we conducted a qRT-PCR analysis to quantify the expression of 19 genes involved in JA biosynthesis and signaling in rice stems at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of SSB infestation. The qRT-PCR method was as described above, and the primers are shown in Table S10.

2.6. Volatile Analysis

2.6.1. Collection and Analysis of Rice Plant Volatiles

Damaged Mudgo or TN1 rice plants were individually infested with one 3rd-instar larva of SSB for 3 days. Healthy plants were the same batch without being infested. Volatile compounds were collected using a dynamic headspace collection system as described by Jiao et al., 2018 [34]. In brief, five plants as a treatment group were transferred into a glass bottle. Next, the air was filtered utilizing a combination of activated charcoal, molecular sieves (5 Å, beads, 8–12 mesh, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), and silica gel Rubin (cobalt-free drying agent, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Airflow was regulated by a calibrated flowmeter to maintain a constant rate of 400 mL/min, which was verified prior to each collection to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Volatiles from the headspace were then drawn through a glass tube (5 mm inner diameter; 8 cm length) packed with 30 mg of Super Q adsorbent (80/100 mesh, Alltech Associates, Deerfield, IL, USA) over a period of 4 h.

The gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis method was described by Hu et al., 2020 [35]. A quantity of 500 ng of nonyl acetate was added to the samples as an internal standard for the relative quantification of compounds based on areas [36]. The collection of plant volatiles was repeated seven or eight times for each treatment.

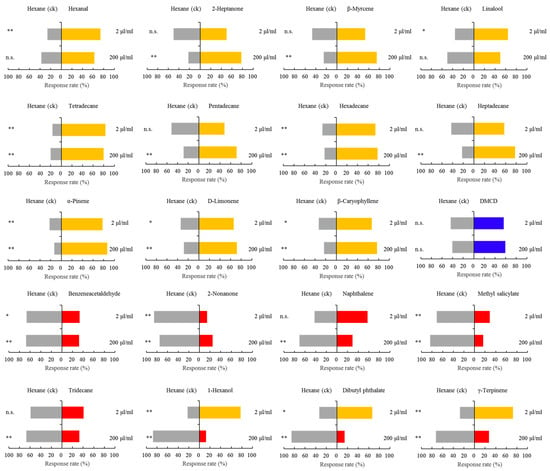

2.6.2. Choice Bioassay Using a Y-Tube Tube Olfactometer

Based on the GC-MS results, 16 volatiles, including heptadecane, benzeneacetaldehyde, β-myrcene, naphthalene, dibutyl phthalate, pentadecane, tridecane, hexanal, linalool, hexadecane, 1-hexanol, 2-heptanone, 2-nonanone, dibutyl phthalate, tetradecane, and methyl salicylate, were selected for further experiments to determine their effects on BPH behavior. These compounds had shown significant induction or were newly produced in response to SSB damage. Compounds with analytical-grade purity were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

To investigate the behavioral responses of BPH females to the selected compounds, a Y-tube (10 cm stem; 10 cm arms at 75° angle; 1.5 cm internal diameter) was used. The olfactometer was connected to an air delivery system consisting of an air pump, a charcoal filter (for air purification), a humidifier (to maintain appropriate humidity), and flowmeters. This system provided a continuous, clean, and controlled airstream that carried volatiles from the odor sources through the Y-tube arms, preventing stagnation and odor saturation. One arm contained the testing odor, and the other arm contained the control odor, hexane. The testing volatile compounds were individually dissolved in pure hexane. Each compound was tested at a high dose of 200 μL per 1 mL of pure hexane and a low dose of 2 μL/mL. Then, 10 μL of the volatile solution or 10 μL of pure hexane (control) was loaded on the filter papers (1 cm × 2 cm), and they were, respectively, inserted into two glass jars (diameter of 10.5 cm; height of 25 cm) as a pair of odor sources. All behavioral trials were conducted in a darkened room. To eliminate any potential phototaxis bias, the setup was illuminated from below by a uniform light-emitting panel, ensuring that no directional light gradient could influence insect choice. Sixty insects were tested for each compound.

2.7. Metabolic Analyses

2.7.1. Collection and Analysis of Rice Metabolites

The treatment of rice was identical to the transcriptome analyses. Metabolic samples were analyzed using liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC-MS) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) platforms by Metabolon and performed using the automated Microlab STAR® system (Hamilton Company, Bonaduz, Switzerland). The method used was as described by Liu et al., 2016 [28]. In brief, stem samples were divided into four portions for the analysis used: (i) LC-MS with positive ion mode electrospray ionization, (ii) LC-MS with negative ion mode electrospray ionization, (iii) GC-MS, and (iv) reserved for backup. The quantitative values of the metabolites were derived from integrated raw detector counts of the mass spectrometers. Those with great variations due to instrument-integrated tuning differences were normalized on a similar graphical scale. The relative abundances of each metabolite were log-transformed before analysis to meet normality. Student’s t-test was used to compare the abundance of each metabolite between damaged and healthy rice plants. Ten samples were collected and used for each treatment.

2.7.2. Identification of Metabolite Toxicity to BPH Using Artificial Diet

To examine whether an artificial diet that contained a metabolite affected the normal development and survival rate of BPH, two tests were performed. To study development, we measured the mean relative weight gain for newly brachypterous females. For evaluating the survival rate, a fitness bioassay was carried out on newly hatched nymphs of BPH. Both were fed an artificial diet described by Fu et al. (2001) [37]. A primary stock solution of linoleate, linoleate 9(S)-HOTrE, jasmonic acid, 9(S)-HpOTrE, and 9(S)-HpODE was prepared with acetone. Varying concentrations of these compounds in the diet (0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 mmol/L) were obtained by gradient dilution. β-Sitosterol and stigmasterol were prepared with distilled absolute ethyl alcohol. Varying concentrations of β-Sitosterol in the diet (0, 0.031, 0.063, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL) and of stigmasterol (0, 0.0008, 0.004, 0.02, 0.1, 0.5, and 2.5 mg/mL) were obtained via gradient dilution. Glass tubes (2.5 cm diameter; 15 cm length) with smooth openings at both ends were used as feeding devices. One end was covered with double-deck stretched paraffin film (Parafilm M, Bemis Company, Inc., Neenah, WI, USA) containing the artificial diet (10 μL), while the other end was secured with an 80-mesh nylon net. (1) For relative weight gain calculation, a newly brachypterous female of BPH was starved for 2 h and weighed as “weight 1”. Then, they were randomly selected and introduced into the tube for 48 h of feeding and subsequently weighed as “weight 2”. Relative weight gain = weight 2 − weight 1. (2) For survival fitness rate calculation, a newly hatched BPH nymph was introduced into the tube and checked daily, the ecdysis was removed, and the artificial diet was renewed. The feeding container was covered with a black, wet cotton cloth, except at the ends where the food bag opened to a light source. Their development and mortality were recorded daily. Twenty insects were tested in each treatment for relative weight gain, and fifty insects for survival rate.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

Before conducting any statistical analysis, we ensured to check the normality and equality of variances for all data to validate the assumptions of the parametric tests used. The selection of specific statistical tests was based on standard biostatistical principles and the experimental design of our study [38]. Paired t-tests were used to compare planthopper feeding choices. We used independent Student’s t-tests to analyze body weight, body length, development time, EPG activities, volatiles, and metabolome composition [39]. To compare the survival rates of planthoppers, sex ratios, and brachypterous ratios, we carried out a chi-square test [40]. We also used Dunnett’s tests to compare genes in the JA pathway and the total amount of phytohormone in rice stems that had been damaged by SSB larvae for 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, or 72 h relative to the undamaged control (0 h). Additionally, we conducted Dunnett’s tests to compare the BPH relative growth gain with different concentrations of metabolome composition [39]. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS 22.0 software package.

3. Results

3.1. BPH Preferentially Feeds on Caterpillar-Damaged Rice Plants

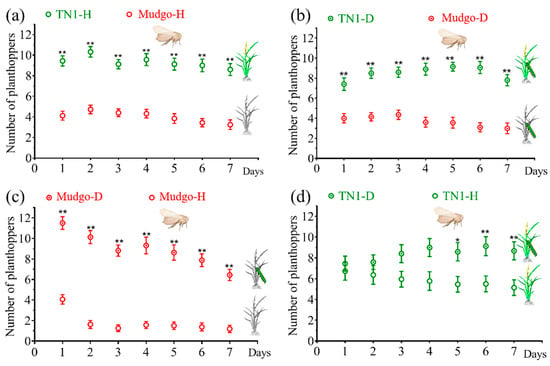

We investigated the feeding preferences of BPH by utilizing two-way choice tests that compared healthy and SSB-damaged Mudgo (BPH-resistant) and TN1 (BPH-susceptible) rice plants in four different scenarios. It was observed that the planthoppers showed a strong preference for the TN1 line when given a choice between healthy Mudgo and TN1 rice plants (p < 0.001) (Figure 1a). When both Mudgo and TN1 plants were damaged by caterpillars, the planthoppers chose to feed on TN1 (p < 0.001) (Figure 1b). However, when the Mudgo was damaged by SSB, the planthoppers preferred the damaged rice plants over the undamaged ones (p < 0.001) (Figure 1c). In the case of SSB-damaged or undamaged TN1 line (Figure 1d), no feeding preference was evident among planthoppers in the first 1–4 days (p > 0.05), but on days 5–7, they preferred the damaged rice plants over undamaged TN1 rice plants (p < 0.05). These findings indicate that planthoppers prefer to feed on damaged plants rather than on undamaged plants.

Figure 1.

Preference of N. lugens for feeding on undamaged or caterpillar-damaged plants of “Mudgo” or TN1 rice over 7 days. The caterpillar symbol indicates damage by a single 3rd-instar Chilo suppressalis larva. In panel labels, (D) represents SSB-damaged (herbivore-induced) plants, and (H) represents healthy/undamaged control plants. Each choice test contained 16–25 replicates with a group of 20 N. lugens per replicate. (a) Healthy TN1 vs. Healthy “Mudgo” rice plants; (b) damaged TN1 vs. damaged “Mudgo” rice plants; (c) damaged “Mudgo” vs. healthy “Mudgo” rice plants; (d) damaged TN1 rice plants vs. damaged TN1. Asterisks indicate significant difference within a choice test: * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 (paired sample t-test).

3.2. Effects on BPH from Feeding on Damaged and Healthy Rice

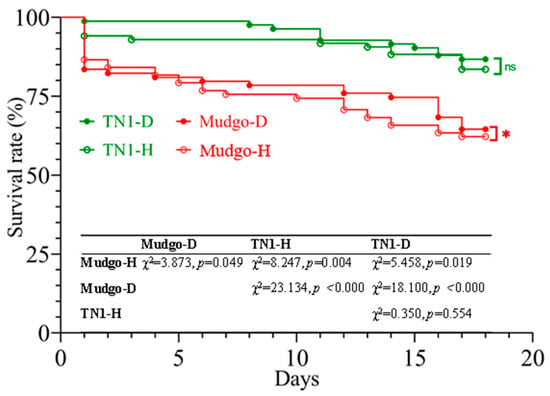

3.2.1. Fitness of BPH from Feeding on SSB-Damaged and Healthy Mudgo and TN1 Rice Plants

Based on the results obtained from the previous experiments, we then evaluated the effects on BPH survival when it fed on damaged plants (either the “Mudgo” resistant or “TN1” susceptible varieties) compared to when it fed on undamaged plants (Figure 2). The results showed that BPH had higher survival rates on damaged Mudgo rice plants than on the other rice plants (log-rank test; χ2 = 3.873; p = 0.049). To further confirm the effects of feeding on the damaged plants on BPH, we measured the duration of each BPH instar stage, including adulthood, as well as the length and weight of emerging adults (Table 1). The results showed that the number of instar days of BPH nymphs was markedly shorter on TN1 than on Mudgo regardless of whether plants were damaged or undamaged. However, adult males emerged significantly earlier with markedly greater weight than those that fed on SSB-damaged versus undamaged Mudgo (p < 0.01). Collectively, these results from survival rate and developmental parameters demonstrate that prior SSB herbivory generally improved host plant quality for BPH across both susceptible and resistant rice varieties.

Figure 2.

Survival rates of N. lugens feeding on “Mudgo” and TN1 rice plants that were undamaged or damaged by C. suppressalis feeding. N. lugens nymphs were allowed to feed continuously on damaged or undamaged rice plants for 18 days until they had almost developed into adults. There were no significant differences between damaged and undamaged TN1 plants, but survival rates were significantly different between “Mudgo” (p < 0.01) (n = 79–123).

Table 1.

Performance of Nilaparvata lugens feeding on “Mudgo” (BPH-resistant) and TN1 (BPH-susceptible) rice plants that were undamaged or damaged by a single 3rd-instar C. suppressalis caterpillar.

3.2.2. Characterization of EPG Waveform of BPH Feeding Rice

To characterize the differences in BPH feeding behavior between SSB-damaged and undamaged plants, we recorded the DC-EPG waveform patterns produced by BPH feedings as established in previous studies [41,42,43]. We focused on six typical EPG waveforms, designated as non-penetration (NP), N1, N2, N3, N4, and N5. The NP waveform correlated to zero feeding. The next feeding phase began with BPH inserting its stylet into the plant and generating irregular but relatively high-amplitude EPG waveforms. The N1 waveforms were also generated by the stylet probing the rice epidermis and appeared for a few seconds. Immediately after the N1 probing phase, the salivary stage began to create the N2 waveforms. The N2 waveforms consisted of regular cycles of small, rapid spikes that gradually increased in overall amplitude but decreased in spike size, followed by an overall dip into a trough. The subsequent N3 waveform was characterized by higher amplitude and less regularity, indicating that the stylet was moving outside the phloem cells. Next, the N4 waveform generated by sucking phloem sap was characterized by frequent, variable waves, while the N5 waveform, in which water was taken up from the xylem, appeared more stable with frequent, uniform waves (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Comparison of electrical penetration graph (EPG) characteristic parameters of N. lugens. (a) Feeding behavior of N. lugens for the total duration of waveforms in 6 h waveforms: NP, non-penetration; N1, probed the rice epidermis; N2, salivation into the sieve element; N3, moving outside the phloem cells; N4, sieve element salivation in the phloem; N5, intake xylem water phase. Each choice test contained 26–33 replicates. (b) Total duration time of probing times was examined in healthy or damaged Mudgo and TN1. * p values < 0.05 and ** p values < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

To identify differences in feeding patterns that are potentially related to herbivory resistance, the total duration of probing times was examined in undamaged or damaged resistant (Mudgo) and susceptible (TN1) varieties. In accordance with the experiments above, the sum of the NP waveform’s total duration was significantly higher in undamaged Mudgo plants than in the other plants (Figure 3b). N1, N2, and N3 waveforms showed no differences between healthy and damaged rice. N4, in which nutrients are acquired, showed a significantly longer duration in the damaged Mudgo rice than in undamaged Mudgo rice (Figure 3b). Taken together, these results indicated that BPH consumed fewer phloem nutrients from undamaged rice than from damaged.

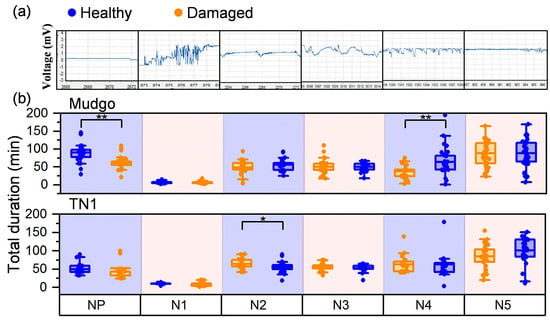

3.2.3. Bph1 Gene Expression in SSB-Damaged Rice

Bph1 gene expression levels were measured at different time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h) in rice plants. qRT-PCR detected no significant change in Bph1 gene expression after SSB damage (Figure 4a), and all data were normalized against the expression of the housekeeping gene ubiquitin 5. Bph1 gene expression was stable in Mudgo but not detected in TN1, whereas ubiquitin 5 was stably expressed in both Mudgo and TN1 genes at all time points (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Bph1 gene expression levels at different time points on Mudgo or TN1. (a) qRT-PCR detected Bph1 gene expression at different time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h). ubiquitin 5, as the housekeeping gene, was used at each time point. (b,c) RT-PCR detected Bph1 and ubiquitin 5 gene expression at different time points in Mudgo and TN1. White arrows indicate the Ubq5 housekeeping gene bands.

3.3. Transcriptomic Changes in Response to BPH Feeding

3.3.1. Overview of the Transcriptome in Rice Plants During SSB Infestation

Global changes in the rice transcriptome were quantified by high-throughput RNA sequencing analysis (RNA-seq) of damaged and undamaged Mudgo stem samples after 72 h feeding by SSB. In total, approximately 56 million clean reads were obtained with a GC content of 55–58% (Table S2). On average, >77% of the reads were mapped to the rice IRGSP-1.0 reference genome, and >95% of the mapped reads were distributed in exons (Table S3).

The differential expression patterns of 17 genes related to phytohormone signaling, primary metabolism, and secondary metabolism were confirmed by qRT-PCR using the stem samples from the same batch of rice plants as those used for RNA-seq. The qPCR expression profiles of these genes were largely consistent with those observed by RNA-seq (Figure S1).

3.3.2. Analyses of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

In total, 32,322 genes were detected in all samples (Table S4), among which 2342 were differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (p < 0.05 corrected for false discovery rate and |fold-change| > 2 or <0.05) (Table S5). Gene ontology (GO) analysis showed that 1220 of the DEGs that exhibited upregulation were mainly involved in cell wall, lipid, and secondary metabolism. Meanwhile, 1122 of the DEGS that showed downregulation were mainly involved in cellular components. Pearson correlation analysis showed high similarity between replicates in each treatment group (0.949–0.967), indicating good reproducibility between samples (Table S6). A Venn diagram illustrating the data revealed that 1077 genes were distinctly expressed in damaged rice plants.

3.3.3. Focus of Analysis of Transcriptomic Changes on Transcription Factors (TFs)

The rice genome is known to contain at least 2000 transcription factor genes, including 63 families [44]. TF-encoding genes were analyzed by searching the Plant Transcription Factor Database (PlantTFDB, V5.0) (https://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/, accessed on 20 December 2025) [45]. The search revealed 188 TFs, including 75 (39.9%) up- and 113 (60.1%) downregulated, spanning 36 families among the 2342 total DEGs (Table S7). We particularly focused on the myeloblastosis (MYB) TF family, which plays a key role in coping with biological stresses and adversity. A total of 23 MYB genes were differentially expressed, among which 13 genes were upregulated (the OS12G0564100 gene was 6.02-fold upregulated), and 10 genes were downregulated. Moreover, the expressions of 15 WRKY TF family genes were affected by the treatments. Among them was OsWRKY7, with its level reported to be upregulated in rice upon SSB infestation and positively correlated with the jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) pathways [46]. Genes from the apetala2-ethylene-responsive element binding protein (AP2-EREBP) TF family, which play an important role in stress response to biotic and abiotic factors in rice, were modified [47]. Out of the 10 genes, OsERF3, which is involved in the induced response in rice to chewing and piercing mouthpart insects, was upregulated [48]. In summary, SSB feeding caused a remarkable enriching effect on rice by inducing genes involved in the defense signaling pathways and upregulation of JA production.

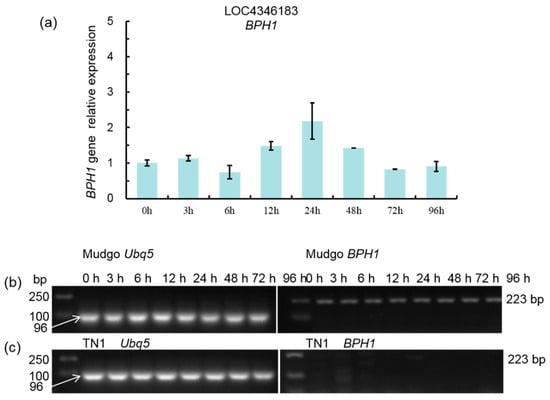

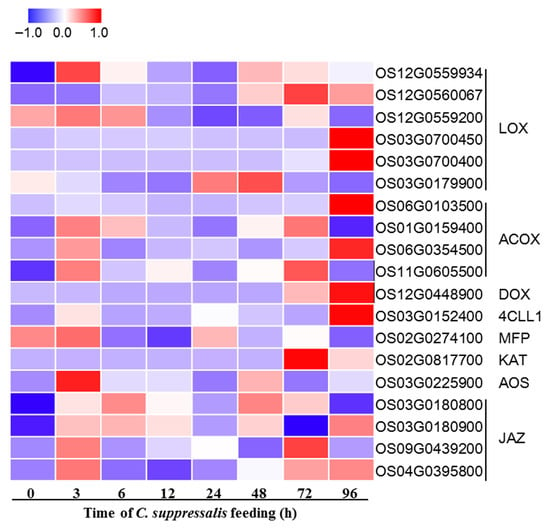

3.3.4. SSB Feeding Induces Plant Hormone and Related Gene Expression

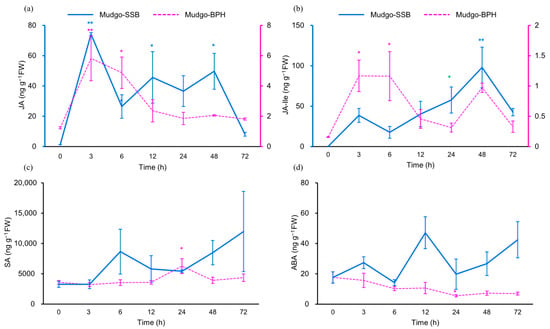

To determine phytohormone changes, we analyzed the concentrations of JA, JA-isoleucine conjugate (JA-Ile), SA, and ABA in rice stems at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h of SSB and BPH infestation (Figure 5). In Mudgo, JA and JA-Ile accumulated significantly after 3 and 48 h, respectively, of SSB feeding. BPH feeding induced JA and JA-Ile accumulation peaks at 3 and 6 h, respectively. SA and ABA levels were not increased except for 24 h of BPH feeding. With the exception of LOX6 (OS03g0179900) and AOS2 (OS03g0225900), all other genes involved in the JA pathway, including lipoxygenases (LOX), allene oxide synthase (AOS), allene oxide cyclase (AOC), oxo-phytodienoate reductase (OPR), and jasmonate resistant (JAR), were significantly upregulated following SSB herbivory (Figure 6). GO, KEGG pathway enrichment, and hierarchical clustering analyses revealed that SSB feeding differentially affected rice phytohormone signaling pathways. Infestation induced a high expression of JA signaling-dependent genes and moderate expression of genes associated with other phytohormone signaling pathways. The genes involved in the JA synthesis pathway were upregulated, with the exception of LOX (OS03G0179900) and AOS (OS03G0225900). In addition, four genes involved in JA signal transduction and JAZ homologs were also differentially upregulated (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Phytohormone contents (ng/g FW) in rice stems. (a) JA, (b) JA-Ile, (c) SA, and (d) ABA contents. The solid blue lines indicate rice plants damaged by C. suppressalis, and dashed pink lines indicate rice plants damaged by N. lugens. Values are mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to time zero: * p values < 0.05; ** p values < 0.01 (Dunnett’s test).

Figure 6.

C. suppressalis-induced responses of genes in the jasmonic acid (JA) pathway. The heat map shows the relative expression of genes associated with the JA pathway in rice plants in response to feeding by C. supressalis. Color coding represents the intensity of induction (red) or suppression (blue) of gene expression by insect feeding.

To investigate the involvement of the JA pathway in response to SSB feeding, we conducted qRT-PCR analysis on 19 genes involved in JA biosynthesis and signaling in rice stems at different time points of SSB infestation, specifically at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of SSB infestation (Figure 6). Our results indicated that the majority of these genes participated in JA and JA-Ile biosynthesis and signaling, with key genes such as LOC (OS12G0559934) induced within 3 h of SSB infestation (Figure 6). These results suggest that JA pathway-associated genes were most strongly activated by SSB infestation and likely contributed to changes leading to preferential herbivory by BPH. This is consistent with the finding that JA signaling is central to mediating BPH’s preference for SSB-damaged rice plants [49]. Furthermore, other studies have linked herbivory-induced JA signaling with the production of fatty acid metabolites and other volatiles [49,50]. Specifically, JA-mediated reprogramming of lipid and other metabolic profiles can alter host plant quality for piercing–sucking insects like BPH [50].

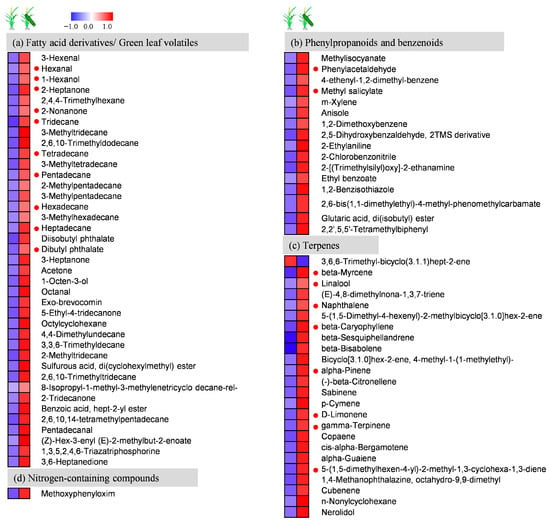

3.4. Volatile Compounds Production and Metabolomic Response to BPH

Differential Production of Plant Volatiles Following Caterpillar Herbivory of Rice

In light of the RNA-seq showing activation of JA-related pathways following herbivory, we next measured volatile emissions from Mudgo and TN1 rice using GC-MS. We detected a total of 115 compounds in the headspace of Mudgo and TN1 rice plants that were undamaged or damaged by SSB (Table S8). In Mudgo, 107 volatiles, of which 34 showed significant emission (e.g., 3-hexenal, 2-heptanone, 1-hexanol, beta-myrcene, 2-nonanone, methyl salicylate, beta-caryophyllene, beta-sesquiphellandrene, and beta-bisabolene), were identified in the headspace of damaged plants, and 47 compounds (such as α-pinene, γ-terpinene, and 3-heptanone) were not found in healthy Mudgo samples. Only one volatile, 3,6,6-trimethyl-bicyclo (3.1.1) hept-2-ene, was decreased in Mudgo (Figure 7). Overall, in response to caterpillar infestation, the production of 31 compounds was significantly elevated, and 1 was reduced in Mudgo plants.

Figure 7.

Volatiles collected from the headspace above rice plants subjected to feeding by C. suppressalis. Heat map presentation of the relative levels of volatile compounds released by damaged or healthy plants of ”Mudgo” after feeding by one 3rd-instar larva of C. suppressalis for 72 h. Each line in the heat map represents one volatile compound. The color code indicates each metabolite’s content relative to the median metabolite concentration. Values were generated by normalizing directly on a similar graphic scale to their median values. Red indicates a higher metabolite content, and blue indicates a lower content in the sample. The red dots are Y-tube verification volatiles.

Next, we conducted two-choice Y-tube assays to assess BPH’s response to 20 volatile compounds at low doses (2 μL/mL) and high doses (200 μL/mL) of each compound. Eleven volatiles in this panel significantly attracted BPH. These were tetradecane, alpha-pinene, hexadecane, beta-caryophyllene, D-limonene, heptadecane, beta-myrcene, pentadecane, 2-heptanone, hexanal, and linalool. By contrast, five compounds were significantly repellent to BPH at high or both doses; these included methyl salicylate, benzeneacetaldehyde, 2-nonanone, tridecane, and naphthalene. Interestingly, only low doses of 1-hexanol, dibutyl phthalate, and gamma-terpinene were attractive to female BPH, but they were repelled by high doses. These results strongly suggest that the emission of volatiles following herbivory attracted BPH to feed on damaged Mudgo rice plants (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

N. lugens responses to individual herbivore-induced volatile compounds at low or high concentrations. Response of N. lugens (Y-tube assay) to selected key rice volatile compounds that were induced by plant damage. The compounds shown were repellent at either a low (2 μL/mL) or high (200 μL/mL) dose. Columns with asterisks indicate that the test volatiles significantly attracted or repelled N. lugens. Asterisks indicate significant difference within a choice test: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 (paired sample t-test) (n = 60). n.s. indicates no significance.

3.5. Metabolome Composition Following Caterpillar Herbivory of Rice

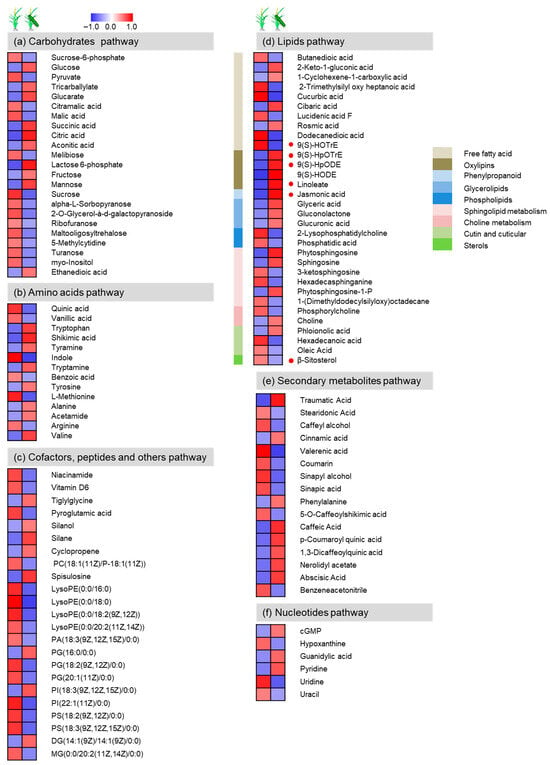

In addition to volatiles, this study also examined the metabolome composition of rice using LC-MS and GC-MS. A total of 114 known metabolites were detected as significantly different between damaged and undamaged Mudgo rice plants and were grouped into nine classes by mapping the general biochemical pathways based on KEGG and the plant metabolic network (PMN). The greatest enrichment was found in carbohydrates (23), lipids (32), amino acids (14), nucleotides (6), phenolic acids (61), cofactors (2), peptides (2), secondary metabolites (16), and others (19) (Table S9). Overall, more metabolites increased than decreased in response to SSB infestation (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Metabolic profiles of rice plants damaged by C. suppressalis. (a) carbohydrates; (b) amino acids; (c) cofactors, peptides and others; (d) Lipids; (e) secondary metabolites; (f) nucleotides. Heatmap presentation of the volatile compounds in Mudgo after infestation by one 3rd instar of Chilo suppressalis for 72 h or undamaged. Each line in the heatmap represents one volatile. The color code indicates each metabolite’s content relative to the median metabolite concentration. Red indicates a higher metabolite content, and blue indicates a lower content in the sample (n = 10).

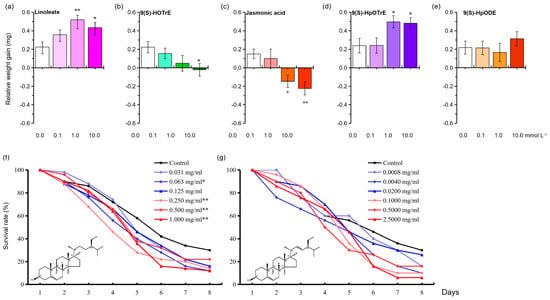

To investigate the effect of metabolites on the development and survival of BPH, we selected five metabolites: (9(S)-HOTrE, 9(S)-HpOTrE, 9(S)-HpODE, linoleate, and jasmonic acid) for relative weight gain and beta-sitosterol for the survival rate (Figure 10). We also tested stigmasterol, which is similar in structure to beta-sitosterol and reported to have negative effects on BPH [51]. We found the following three trends: A) 9(S)-HpOTrE and linoleate increased the relative weight gain of BPH, B) 9(S)-HpOTrE and jasmonic acid inhibited BPH feeding, and C) 9(S)-HpODE had no effect on BPH feeding (Figure 10a–e). In addition, increasing the dietary amount of beta-sitosterol reduced the number of surviving BPH nymphs. Pairwise correlation analysis further revealed that increasing concentrations of beta-sitosterol at 0.063, 0.250, 0.500, or 1.000 mg/mL diet led to a dose-dependent decrease in survival rates compared to that of the control (χ2 =6.294, df = 1, p = 0.012; χ2 = 8.466, df = 1, p = 0.004; χ2 = 15.924, df = 1, p < 0.000 and χ2 = 11.762, df = 1, p = 0.001, respectively) (Figure 10f). Stigmasterol did not affect BPH survival compared to planthoppers on a holidic diet (Figure 10g).

Figure 10.

Relative growth and survival rates of N. lugens larvae fed on an artificial diet containing different concentrations of metabolite. (a–e) Linoleate, 9(S)-HOTrE, jasmonic acid, 9(S)-HpOTrE, and 9(S)-HpODE affected N. lugens relative growth gain. (f,g) Beta-sitosterol and stigmasterol affected BPH survival rates. Asterisks denote significant differences between the treatment and the control. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 (Dunnett’s test).

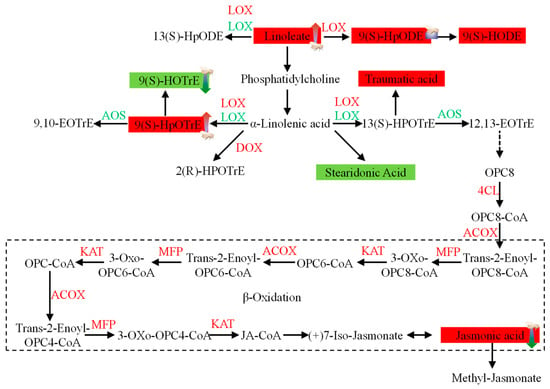

In summary, our transcriptome and metabolome analyses revealed that SSB activated the JA pathway, which in turn impacted BPH feeding (Figure 11). We show that the transcriptional upregulation of genes was accompanied by the elevation of key metabolites in the pathways. Volatiles or metabolites that elicited or had a positive or negative response or effect on BPH were also identified. For example, linoleate, 9(S)-HpOTrE, and jasmonic acid were increased after SSB infestation, which increased the relative weight gain of BPH.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram showing the synthesis of jasmonic acid in rice. 4CL, 4-coumarate-CoA ligase-like 1; ACOX, peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1; AOS, allene oxide synthase 2; DOX, alpha-dioxygenase; KAT, 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase-like protein; LOX, lipoxygenase; MFP, peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation multifunctional protein. The concentrations of metabolites shaded in colors were measured. Solid arrows represent established biosynthetic steps, while broken arrows indicate the involvement of multiple enzymatic reactions. Green indicates downregulation, and red indicates upregulation.

4. Discussion

Our study provides a clear mechanistic explanation for the perplexing phenomenon where crop varieties exhibiting high resistance in controlled laboratory environments show significantly compromised resistance in the field. By integrating behavioral assays, transcriptomics, phytohormone profiling, and metabolomics, we demonstrate that prior herbivory by the striped stem borer (SSB) Chilo suppressalis disrupts the resistance of the rice variety “Mudgo” against the brown planthopper (BPH) Nilaparvata lugens. This disruption is orchestrated by SSB-induced jasmonate (JA) signaling, which reprograms the rice plant’s physiology and biochemistry, inadvertently enhancing its suitability for the subsequent piercing–sucking pest. These findings underscore the critical importance of evaluating insect resistance within the complex network of multi-species interactions that characterize agricultural ecosystems.

Our experiments showed a clear example of how a breeding variety of crops (Mudgo, resistance to BPH) loses its resistance to target insects because of non-target (SSB) infestation. BPH individuals preferred to feed on rice plants that had been previously damaged by SSB over healthy/undamaged rice plants. This aligns with previous research showing that non-Bt rice fields contain more BPH than Bt rice fields due to the significant caterpillar damage sustained by non-Bt rice plants [19,52]. Our research identifies key factors contributing to the loss of BPH resistance in the rice variety “Mudgo” due to SSB damage, which may be evident in germplasm evaluation programs.

4.1. SSB Infestation Overrides BPH Resistance in “Mudgo”

Our initial experiments confirmed that BPH preferred SSB-infested rice plants regardless of their resistance to BPH (Figure 1). More critically, this behavioral preference translated into significant physiological gains: BPH survival rates increased, and adult males emerged earlier and with greater weight on damaged “Mudgo” plants (Figure 2, Table 1), in line with previous studies [53,54,55,56]. A study of a “Mudgo” variety that carries the gene Bph1, which provides moderate resistance to the brown planthopper, showed similar results with respect to the upregulation of genes involved in the synthesis of amino sugars, nucleotide sugars, and carbohydrate metabolism [57].

The EPG technique allows for detailed tracking of stylet activities during insect feeding [43]. In line with our findings, Sogawa and Pathak (1970) found that the brown planthopper took longer to probe the susceptible rice variety TN1 than the resistant variety Mudgo [53] (Figure 3). This phenomenon was also observed in aphids probing wheat. They probed more frequently and for longer periods on sensitive plants during feeding [24]. In tea and melon plants, the duration of waveform E2 was negatively correlated with the resistance of different cultivars to aphids [58,59]. This suite of findings represents a fundamental shift in the host–pest relationship for a conventionally resistant variety. Crucially, this loss of resistance was contingent upon the prior activation of plant defense pathways by SSB, as the expression of the major resistance gene Bph1 itself remained unchanged (Figure 4). This indicates that the resistance breakdown occurs downstream of the initial recognition event, mediated by a modulation of the plant’s inducible response rather than the resistance gene itself.

4.2. JA-Mediated Transcriptional and Metabolic Reprogramming as the Core Mechanism

The central finding of our multi-omics approach is that SSB herbivory acts as a powerful trigger, initiating a JA-dominated signaling cascade that extensively reshapes the rice plant’s state. We observed a rapid and sustained accumulation of JA and its bioactive conjugate JA-Ile (Figure 5), accompanied by the upregulation of nearly the entire JA biosynthesis pathway (Figure 6). The transcriptome analysis revealed that more DEGs were upregulated than downregulated in response to SSB larval feedings. This is consistent with previous findings on MH63 rice [28] and maize [60,61,62]. This JA burst functioned as a master regulator, driving the differential expression of 2342 genes. Transcription factors (TFs) play a crucial role in how plants respond to herbivory by regulating gene expression [46,47,63]. More specifically, TFs regulate plant defenses both upstream and downstream of phytohormone signaling. Our qRT-PCR analysis on 19 key JA pathway genes confirmed their strong activation, with some, like LOC_Os12g0559934, induced within 3 h of SSB infestation (Figure 6). Among these, key transcription factor families pivotal for stress responses were prominently affected, including WRKY, AP2/EREBP, and MYB. This suggests that WRKYs play a crucial part in plant development and in responses to biotic stressors [46,47,60,64,65]. WRKYs are involved in JA and SA signaling pathways and herbivore-induced defense responses [65,66]. For example, it has been shown that OsWRKY70 mediates the prioritization of defense over growth by positively regulating cross-talk between JA and SA when rice is attacked by SSB [46], while OsWRKY53 is induced upstream of the JA pathway but negatively regulates the ethylene pathway [65]. This pattern aligns with the established role of these TFs in regulating JA-dependent defense responses and suggests a broad rewiring of the plant’s regulatory network towards a specific defense output.

Our study found that damage caused by SSB led to the activation of JA-associated genes, consistent with prior research [63] (Figure 7). In our study, SSB feeding was observed to activate genes related to the KEGG pathway “alpha-linolenic acid metabolism”. The levels of both JA and JA-Ile increased significantly at all seven time points, with the most notable elevations occurring at 3 h, 12 h, and 48 h after SSB damage to “Mudgo” rice plants. Applying methyl JA externally to rice plants had a negative impact on the performance of two root herbivores—the cucumber beetle (Diabrotica balteata) and the rice water weevil (Lissorhoptrus) [67]—and induced the release of volatiles that attract parasitoids [68]. This integrated response—comprising the suppression of certain direct defenses and the emission of attractive volatiles—illustrates how the SSB-induced JA signal reconfigures the host plant into a more favorable niche for BPH.

4.3. Reconciling the Paradox and Implications for Resistance Breed

The most intriguing implication of our work is the paradoxical outcome: an activated defense hormone pathway leads to enhanced susceptibility to a subsequent herbivore. We propose that SSB herbivory and subsequent JA pathway activation facilitate BPH feeding through a multi-pronged mechanism. This includes JA-mediated alterations in the host plant’s nutritional profile, physical structure, and, most clearly demonstrated here, its volatile and non-volatile metabolic emissions. These changes collectively create a more favorable feeding environment for BPH.

We compared the volatiles emitted by healthy/damaged Mudgo and TN1 rice plants to understand the biochemical mechanisms that cause BPH to prefer caterpillar-damaged plants. Our hypothesis was that herbivory-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) were responsible for the different behavioral responses of planthoppers toward damaged and undamaged rice plants. HIPVs are known to have a significant impact on insect community composition in the field [69], and changes in their composition may significantly increase their appeal [70]. Indeed, we found that when both BPH-resistant varieties, the Mudgo and TN1 plants, were damaged by SSB, Mudgo emitted a higher number of volatiles than TN1 (Figure 8). GC-MS analyses revealed that the concentrations of the rice volatiles, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene were significantly increased by caterpillar damage in Mudgo plants. These volatiles have been previously shown to be attractive to planthoppers [69,71,72]. Several other compounds, including tetradecane, hexadecane, D-limonene, heptadecane, beta-myrcene, pentadecane, 2-heptanone, hexanal, and linalool, have also been identified to have a considerable attraction effect on BPH. The release of these volatile compounds is under the control of the JA signaling pathway [73], which is widely recognized as the mechanism that regulates plants’ defense response against herbivores [74]. According to a recent study, the JA synthesis pathway and esters are interconnected and overlap [49]. By contrast, sterols, such as beta-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and campesterol, have been reported to inhibit BPH feeding [51]. Our analysis of the metabolome revealed that herbivory by SSB larvae led to a reduction in the beta-sitosterol levels in rice tissues. This can be attributed to the function of fatty acids as primary building blocks for the production of jasmonic acid and esters, which then transform into 13(S)-hydroperoxylinolenic acid (13 S-HPOT) via the lipoxygenase pathway [75]. Moreover, 13 S-HPOT is a key intermediate in the JA synthesis pathway. We also found that as the concentrations of beta-sitosterol in the diet increased, progressively fewer BPH nymphs developed into adults (Figure 11). This is similar to studies that demonstrated how BPH development was inhibited by decreasing levels of toxic beta-sitosterol [19,51]. We infer that TFs are responsible for changing the levels of JA in response to SSB damage. This, in turn, triggers the JA signaling pathway, which regulates plant defense via a complex metabolic network. The network involves the release of HIPVs to attract BPH while decreasing the levels of sterols to promote BPH development.

These findings have direct and significant implications for crop resistance breeding and integrated pest management (IPM). They underscore that varietal resistance evaluated against a single pest in isolation may not hold in the field where sequential pest attacks are the norm. Therefore, future germplasm evaluation programs, especially for crops like rice facing multiple pests, should consider incorporating sequential multi-pest infestation scenarios as a critical testing parameter. From an IPM perspective, our study reveals a critical linkage in pest population dynamics: An outbreak of a primary pest like SSB could create “hotspots” for secondary pest (BPH) outbreaks through this plant-mediated interaction. This emphasizes the importance of managing the “initiator” pest not only for its direct damage but also for its role in potentially inducing secondary pest outbreaks.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study elucidates the molecular and biochemical mechanisms by which SSB herbivory compromises rice resistance to BPH. Our study delved into the differences in volatiles released by damaged and healthy Mudgo and TN1 rice plants. We infer that the JA signal pathway regulates plant defense through a complex metabolic network, as evidenced by the release of HIPVs to attract BPH and a decrease in metabolite contents that help improve BPH development, which collectively create a more favorable host environment for BPH, leading to enhanced feeding, survival, and development. Our study showed that rice resistance to BPH feeding was reduced by SSB damage, which initiated the JA signaling pathway to counter rice plant defense responses. Our findings align with previous research, which showed that mealybugs (Phenacoccus solenopsis) thrived on cotton plants that were previously damaged by P. solenopsis but were negatively impacted when plants were induced with JA [76]. Our research shows how interactions between two insect species can impact the evaluation of germplasm resistance. Both species utilize the rice plant’s defense responses, indicating a cooperative interaction that defies traditional interspecific competition theory. These findings highlight the intricate and complex dynamics present in the interplay between plants and insects and call into question traditional methods of evaluating germplasm resistance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16010091/s1, Figure S1: Comparison of mRNA expression levels detected by RNA-seq analysis for 17 selected genes. All qRT-PCR data were normalized against the expression of the housekeeping gene ubiquitin 5. Values are means ± SE; n = 3 for RNA-seq and n = 4 for qRT-PCR; Table S1: Genes and primer pairs used for quantitative real-time PCR; Table S2: Quality evaluation of sequencing; Table S3: Comparison statistics of reads on reference genome; Table S4: Total genes were detected in all samples; Table S5: Analyses of differentially expressed genes; Table S6: Person correlation inspection; Table S7: Total transcription factors (TFs) were detected in all samples; Table S8: Volatile compounds released by C. Suppressalis damaged rice plants; Table S9: Metabolic profiles by C. suppressalis damaged rice plants; Table S10: Genes and primer pairs used for JA pathway by C. suppressalis damaged rice plants at different point time.

Author Contributions

X.W. conceived the idea. X.W. and J.W. designed the research; X.W., X.Z., Y.Z., and K.Z. performed research; V.T., L.H., and X.W. analyzed the data; all authors were involved in writing this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

China Scholarship Council (Grant No.202108410242); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31802007); Henan Province Post-Doctoral Research Program (Grant No. 201902042); Anyang Institute of Technology Post-Doctoral Program (Grant No. BHJ2019002); Anyang Major Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2025A02NY001); Henan Scientific Research Grant for Returned Scholars (Grant No. 2025ZYZZ010).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khush, G.S. What it will take to feed 5.0 billion rice consumers in 2030. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.G.; Zhang, G.R.; Zhang, W.Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J. Biological control of rice insect pests in China. Biol. Control 2013, 67, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.B.; Chen, M.; Bentur, J.; Heong, K.; Ye, G. Bt rice in Asia: Potential benefits, impact, and sustainability. In Integration of Insect-Resistant Genetically Modified Crops Within IPM Programs; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Sogawa, K.; Liu, G.J.; Shen, J.H. A review on the hyper-susceptibility of Chinese hybrid rice to insect pests. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2003, 17, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shelton, A.; Ye, G.Y. Insect-resistant genetically modified rice in China: From research to commercialization. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Kang, H.; Sun, Z.; Pan, G.; Wang, Q.; Hu, J.; et al. A gene cluster encoding lectin receptor kinases confers broad-spectrum and durable insect resistance in rice. Nat. Biotech. 2015, 33, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Sarao, P.S.; Bhatia, D.; Neelam, K.; Kaur, A.; Mangat, G.S.; Brar, D.S.; Singh, K. High-resolution genetic mapping of a novel brown planthopper resistance locus, Bph34 in Oryza sativa L. X Oryza nivara (Sharma & Shastry) derived interspecific F2 population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hallerman, E.M.; Liu, Q.; Wu, K.; Peng, Y. The development and status of Bt rice in China. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhu, L.; He, G. Towards understanding of molecular interactions between rice and the brown planthopper. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Wu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Cai, B.; Liu, X.; Jing, S.; et al. Bph6 encodes an exocyst-localized protein and confers broad resistance to planthoppers in rice. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Murai, H.; Takumi, S.; Mori, N.; Nakamura, C. Bph9, a dominant brown planthopper resistance gene, is located on the long arm of chromosome 12. Rice Genet. Newsl. 2000, 17, 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Kaur, P.; Kishore, A.; Vikal, Y.; Singh, K.; Neelam, K. Recent advances in genomics-assisted breeding of brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) resistance in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Breed. 2020, 139, 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Kuai, P.; Chen, S.; Lin, N.; Ye, M.; Hu, L.; Lou, Y. Silencing a simple extracellular leucine-rich repeat gene OsI-BAK1 enhances the resistance of rice to brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, F.; Huang, F.; Qiu, Y.; Li, R.; Lou, X. Map-based cloning and characterization of BPH29, a B3 domain-containing recessive gene conferring brown planthopper resistance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 6035–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Jing, S.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Cai, B.; Xin, X.-F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Allelic diversity in an NLR gene BPH9 enables rice to combat planthopper variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12850–12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Gao, F.; Wu, X.; Lu, X.; Zeng, L.; Lv, J.; Su, X.; Luo, H.; Ren, G. Bph32, a novel gene encoding an unknown SCR domain-containing protein, confers resistance against the brown planthopper in rice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, R.; Badenes-Pérez, F.R.; Broekgaarden, C.; Zheng, S.-J.; David, A.; Boland, W.; Dicke, M. Plant-mediated facilitation between a leaf-feeding and a phloem-feeding insect in a brassicaceous plant: From insect performance to gene transcription. Funct. Ecol. 2012, 26, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Li, Y. Can herbivores sharing the same host plant be mutualists? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Meissle, M.; Peng, Y.; Wu, K.; Romeis, J.; Li, Y. Bt rice could provide ecological resistance against nontarget planthoppers. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Weilin, Z. Genetic and biochemical mechanisms of rice resistance to planthopper. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, B.; Ma, R.; Huang, F.; Wang, C.; Hu, H.; Li, C.; Yan, C.; et al. Small brown planthopper resistance loci in wild rice (Oryza officinalis). Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk-Man, K.; Jae-Keun, S. Identification of a rice gene (Bph 1) conferring resistance to brown planthopper (Nilaparvata Iugens Stal) using STS markers. Mol. Cells 2005, 20, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.Z.; Li, S.B.; Liu, P.L.; Peng, Y.F.; Hou, M.L. New artificial diet for continuous rearing of Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2012, 105, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-H.; Kang, Z.-W.; Tan, X.-L.; Fan, Y.-L.; Tian, H.-G.; Liu, T.-X. Physiology and defense responses of wheat to the infestation of different cereal aphids. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T. Evolving ideas about genetics underlying insect virulence to plant resistance in rice-brown planthopper interactions. J. Insect Physiol. 2016, 84, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Nijhawan, A.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. Validation of housekeeping genes as internal control for studying gene expression in rice by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tzin, V.; Romeis, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y. Combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses to understand the dynamic responses of rice plants to attack by the rice stem borer Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Hettenhausen, C.; Meldau, S.; Baldwin, I.T. Herbivory rapidly activates MAPK signaling in attacked and unattacked leaf regions but not between leaves of Nicotiana attenuata. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1096–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Hu, X.; Peng, Y.; Wu, K.; Romeis, J.; Li, Y. Bt rice plants may protect neighbouring non-Bt rice plants against the striped stem borer, Chilo suppressalis. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20181283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Su, S.; Liu, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Turlings, T.C.J. Caterpillar-induced rice volatiles provide enemy-free space for the offspring of the brown planthopper. eLife 2020, 9, e55421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, E.S.; Laplanche, D.; Guo, H.; Xu, W.; Vlimant, M.; Erb, M.; Ton, J.; Turlings, T.C.J. Spodoptera frugiperda caterpillars suppress herbivore-induced volatile Emissions in Maize. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.; Lai, F.; Sun, Z. A chemically defined diet enables continuous rearing of the brownplanthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stal) (Homoptera: Delphacidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool 2001, 36, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, S. Statistical Analysis of Empirical Data: Methods For applied Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.K. A discussion and evaluation of statistical procedures used by JIMB authors when comparing means. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.C. Chi-Square Test: Analysis of Contingency Tables. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 250–252. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, B.Y.; Kwon, Y.-H.; Jung, J.K.; Kim, G.-H. Electrical penetration graphic waveforms in relation to the actual positions of the stylet tips of Nilaparvata lugens in rice tissue. J. Asia-Pacif. Entomol. 2009, 12, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losel, P.M.; Goodman, L.J. Effects on the feeding behaviour of Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) of sublethal concentrations of the foliarly applied nitromethylene heterocycle 2-nitromethylene-1, 3-thiazinan-3-yl-carbamaldehyde. Physiol. Entomol. 1993, 18, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, M.B.A.; Pritchard, J.; Ford-Lloyd, B. Brown planthopper (N. lugens Stal) feeding behaviour on rice germplasm as an indicator of resistance. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, A.; Zhu, Q.; Tang, W.; Zheng, W.; Gu, X.; Wei, L.; Luo, J. DRTF: A database of rice transcription factors. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1286–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Riaño-Pachón, D.M.; Corrêa, L.G.G.; Rensing, S.A.; Kersten, B.; Mueller-Roeber, B. PlnTFDB: Updated content and new features of the plant transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D822–D827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Q.; Bian, W.; Erb, M.; Lou, Y. Prioritizing plant defence over growth through WRKY regulation facilitates infestation by non-target herbivores. eLife 2015, 4, e04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, M.K.; Swain, S.; Gautam, J.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Bhattacharjee, L.; Nandi, A.K. The Arabidopsis thaliana At4g13040 gene, a unique member of the AP2/EREBP family, is a positive regulator for salicylic acid accumulation and basal defense against bacterial pathogens. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ju, H.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, C.; Erb, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Lou, Y. An EAR-motif-containing ERF transcription factor affects herbivore-induced signaling, defense and resistance in rice. Plant J. 2011, 68, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, X.; Su, S.; Ning, Y.; Peng, Y.; Ye, G.; Lou, Y.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Li, Y. Cooperative herbivory between two important pests of rice. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Du, B.; He, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, J. Lipid profiles reveal different responses to brown planthopper infestation for pest susceptible and resistant rice plants. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, Y.; Murofushi, N.; Ito, K.; Kaneda, C.; Kawabe, S.; Takahashi, N. Sterols and asparagine in the rice plant, endogenous factors related to resistance against the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens). Agric. Biol. Chem. 1982, 46, 2877–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ye, G.; Hu, C.; Tu, J.; Datta, S. Effect of transgenic Bt rice on dispersal of planthoppers and leafhoppers as well as their egg parasitic wasps. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric. Life Sci.) 2003, 29, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sogawa, K.; Pathak, M.D. Mechanisms of brown planthopper resistance in mudgo variety of rice (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool 1970, 5, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Han, Z.J. Individual virulence index of Nilaparvata lugens on a resistant variety of rice Mudgo. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2003, 46, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-X.; Zheng, X.-S.; Yang, Y.-J.; Tian, J.-C.; Fu, Q.; Ye, G.-Y.; Lu, Z.-X. Changes in endosymbiotic bacteria of brown planthoppers during the process of adaptation to different resistant rice varieties. Environ. Entomol. 2015, 44, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Wang, Z.J.; Liao, Z.H.; Deng, J.Y.; Zhu, X.D.; Zhou, G.X. Functional analysis of rice OsLecRK1 in resistance to rice brown planthopper. J. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 43, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Yu, H.; Fu, Q.; Chen, H.; Ye, W.; Li, S.; Lou, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis of salivary glands of two populations of rice brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, that differ in virulence. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzo, E.; Soria, C.; Gómez-Guillamón, M.L.; Fereres, A. Feeding behavior ofAphis gossypii on resistant accessions of different melon genotypes (Cucumis melo). Phytoparasitica 2002, 30, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.-Y.; Liu, L.-F.; Yu, X.-P.; Han, B.-Y. Evaluation of the resistance of different tea cultivars to tea aphids by EPG technique. J. Integr. Agric. 2012, 11, 2028–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzin, V.; Fernandez-Pozo, N.; Richter, A.; Schmelz, E.A.; Schoettner, M.; Schafer, M.; Ahern, K.R.; Meihls, L.N.; Kaur, H.; Huffaker, A.; et al. Dynamic maize responses to aphid feeding are revealed by a Time series of transcriptomic and metabolomic assays. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1727–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Sun, G.; Wang, L.; Zhao, C.; Hettenhausen, C.; Schuman, M.C.; Baldwin, I.T.; Li, J.; Song, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Oral secretions from Mythimna separata insects specifically induce defense responses in maize as revealed by high-dimensional biological data. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Qi, J.; He, K.; Wu, J.; Bai, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z. The Asian corn borer Ostrinia furnacalis feeding increases the direct and indirect defence of mid-whorl stage commercial maize in the field. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, X.; Yan, F.; Li, R.; Cheng, J.; Lou, Y. Genome-wide transcriptional changes and defence-related chemical profiling of rice in response to infestation by the rice striped stem borer Chilo suppressalis. Physiol. Plant. 2011, 143, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-Z.; Chen, J.-Y.; Xiao, H.-J.; Xiao, Y.-T.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.-X.; Zhou, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Guo, Y.-Y. Dynamic transcriptome analysis and volatile profiling of Gossypium hirsutum in response to the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Ye, M.; Li, R.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Q.; Lu, J.; Lou, Y. The rice transcription factor WRKY53 suppresses herbivore-induced defenses by acting as a negative feedback modulator of mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2907–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Ryu, C.M.; Kim, Y.C.; Cho, B.H.; Yang, K.Y. Involvement of the OsMKK4-OsMPK1 cascade and its downstream transcription factor OsWRKY53 in the wounding response in rice. Plant Pathol. J. 2014, 30, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Robert, C.A.; Riemann, M.; Cosme, M.; Mene-Saffrane, L.; Massana, J.; Stout, M.J.; Lou, Y.; Gershenzon, J.; Erb, M. Induced jasmonate signaling leads to contrasting effects on root damage and herbivore performance. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1100–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.-G.; Du, M.-H.; Turlings, T.C.; Cheng, J.-A.; Shan, W.-F. Exogenous application of jasmonic acid induces volatile emissions in rice and enhances parasitism of Nilaparvata lugens eggs by theParasitoid Anagrus nilaparvatae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 1985–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Erb, M.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Ge, L.; Hu, L.; Li, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, T.; Lu, J.; et al. Specific herbivore-induced volatiles defend plants and determine insect community composition in the field. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blubaugh, C.K.; Asplund, J.S.; Eigenbrode, S.D.; Morra, M.J.; Philips, C.R.; Popova, I.E.; Reganold, J.P.; Snyder, W.E. Dual-guild herbivory disrupts predator-prey interactions in the field. Ecology 2018, 99, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xin, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, L.; Lou, Y.; Lu, J. (E)-β-caryophyllene functions as a host location signal for the rice white-backed planthopper Sogatella furcifera. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 91, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, M.I.; Younas, A.; Adeel, M.M.; Duan, S.-G.; Quershi, S.R.; Kaleem Ullah, R.M.; Wang, M.-Q. The role of chemosensory protein 10 in the detection of behaviorally active compounds in brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Insect Sci. 2020, 27, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenbucher, S.; Olson, D.; Ruberson, J.; Wäckers, F.; Romeis, J. Resistance mechanisms against arthropod herbivores in cotton and their interactions with natural enemies. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2013, 32, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, M.; Reymond, P. Molecular interactions between plants and insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 527–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pare, P.W.; Tumlinson, J.H. Plant volatiles as a defense against insect herbivores. Plant Physiol. 1999, 121, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, X.; Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Ruan, Y. Suppression of jasmonic acid-dependent defense in cotton plant by the mealybug Phenacoccus solenopsis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.