Abstract

Spring frost poses a major threat to grape-producing regions, severely reducing grape yield and quality. Grafting rootstocks is an effective strategy for enhancing scion resistance to spring frost and mitigating damage. In this study, the two wine grape cultivars (‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’) grafted onto three rootstocks (‘Beta’, ‘Kober 5BB’, and ‘3309 Couderc’) were evaluated for their spring frost resistance on one-year-old vines. The scion–rootstock combinations exhibited significantly less photosynthetic impairment under frost stress compared with own-rooted vines. Rootstock also showed lower levels of proline accumulation in the roots and APX activities in the leaves under frost conditions. Compared with own-rooted vines, VvCBF1 gene expression were significantly upregulated in the grafted combinations under frost stress conditions. Among the tested rootstocks, ‘Kober 5BB’ markedly improved the spring frost resistance of both cultivars. CH/5BB exhibited the highest activities of POD and APX activity and the greatest induction of VvCBF genes, along with the lowest relative electrical conductivity and H2O2 content. These results highlight the critical role of rootstocks in improving scion spring frost resistance and provide important guidance for selecting suitable rootstocks to mitigate the impact of late frosts.

1. Introduction

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the most widely cultivated fruit crops worldwide and holds significant economic value in agriculture. Spring frost poses a significant threat to grape production in key viticultural regions, such as Europe, North America, Australia, and Asia. During early spring, grapevines emerge from dormancy, and the young tissues become particularly vulnerable to late spring frosts. With the continuous rise in global temperature, the climatic characteristics of grape-producing regions have changed markedly. Such climatic shifts often advance grapevine phenology and increase the risk of late spring frost events, leading to substantial economic losses [1]. For example, Ningxia grape-producing regions in China suffered severe spring frost damage in 2020 with the lowest temperature reaching −6 °C for four consecutive days, which led to a yield reduction of 30–60% [2]. Currently, the primary frost prevention and mitigation measures include physical interventions, such as wind machines and sprinklers, and chemical regulators, such as FrostShield®. Therefore, developing efficient and sustainable strategies to prevent and control late frost damage has become an urgent issue in grape cultivation and production worldwide.

Spring frost frequently inflicts severe damage on the fruitful primary buds of grapevines, leading to their death or dysfunction and forcing the subsequent sprouting of less fruitful secondary buds, which directly compromises grape yield and quality [3,4]. This abiotic stress disrupts stomatal function, water vapor exchange, and chlorophyll biosynthesis, while also damaging the thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts, leading to reduced photosynthetic efficiency and impaired carbon assimilation [5]. Spring frost typically triggers excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, membrane lipid peroxidation, and photosynthetic impairment in grapevines [6,7], with key physiological processes, such as the antioxidant defense pathway (e.g., superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX)-mediated H2O2 scavenging), and osmotic adjustment (via soluble sugar and proline accumulation), playing pivotal roles in alleviating spring frost-induced damage [8,9,10].

Grapevine cultivars of diverse origins respond differently to spring frost: European Vitis vinifera cultivars are generally sensitive to extreme winter freezing conditions [11], yet their delayed dormancy release in spring makes them less prone to spring frost injury than fast-deacclimating interspecific hybrids. Rootstocks are developed to enhance the adaptability, resilience, and overall performance of cultivated plants under diverse environments [12]. Studies have shown that spring frost resistance was different among the rootstock genotypes. The rootstock cultivar ‘Beta’ demonstrated a higher level of frost stress resistance, followed by ‘Kober 5BB’, ‘110 Richter’, and ‘3309 Couderc’ [13]. Rootstocks are selected in grafting grapevine for their contribution to scion growth, fruit composition, and stress resistance [14]. Rootstock influences the performance of scion through complex physiological and molecular mechanisms, such as water and nutrient uptake, hormone, transcriptional regulation, antioxidant defense, osmotic adjustment, and the induction of secondary metabolic pathways in the scion [15,16,17]. However, different studies report variable results, with some indicating little difference between grafted and own-rooted vines, while others revealed that specific rootstocks substantially enhanced vine resilience and productivity under stress conditions [18,19]. The variability highlights the importance of matching rootstock genotype, scion cultivar, and environmental conditions to achieve optimal vine performance.

Although numerous studies have evaluated the frost resistance among grape cultivars, few have investigated the effects of grafting combinations on the response of scion new shoots to late spring frost [20,21,22]. This study examines the bidirectional influence of grafting, focusing on the effect of rootstock on improving scion spring frost resistance and scion-driven modifications of rootstock physiological responses. The objective of the study was to provide a better understanding of graft-mediated environmental adaptation and a strategy of rootstock selection to prevent spring frost damage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘Chardonnay’, ‘Kober 5BB’ (Vitis berlandieri × Vitis riparia), ‘Beta’ (Vitis riparia × Vitis labrusca), and ‘3309 Couderc’ (Vitis riparia × Vitis rupestris) were planted separately and own-rooted in the experimental vineyard of Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China. One-year-old canes were collected in the winter of 2023, and they were then stored at 4 °C until March 2024. All cuttings were grown in a greenhouse at 25 °C in 3 L pots filled with a substrate composed of sandy-loam soil. Own-rooted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘Chardonnay’, ‘Beta’, ‘Kober 5BB’, and ‘3309 Couderc’ were designated as CS, CH, Beta, 5BB, and 3309C, respectively. To establish grafting combinations, CS was used as the scion and grafted onto the rootstocks Beta, 5BB, and 3309C. The resulting grafted vines were designated as CS/Beta, CS/5BB, and CS/3309C. Similarly, the grafted vines with CH as the scion were designated as CH/Beta, CH/5BB, and CH/3309C. All grafted grapevines were one-year-old seedlings purchased from a professional nursery (Yuquanying Seedling Center, Yongning County, Ningxia).

Uniform and healthy grapevines with five-to-six fully expanded leaves were selected for the experiment. The vines were exposed to −2 °C for 3.5 h for the freezing treatment, while CK (control check, ambient temperature control) was kept at 25 °C for the same duration (25 °C, the optimal growth temperature for grapevines, without low-temperature stress). Each treatment consisted of three replicates, with five pots per replicate. After the treatment, leaves from the third and fourth basal nodes were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately, and subsequently stored in a deep freezer at −80 °C.

For the evaluation of the root response, the vines were taken out of the pot. Roots were washed and dried on filter paper. The vines were kept at −6 °C for 8 h. CK was maintained at 25 °C. Each treatment included three replicates with five vines in each replicate. After the treatment, all roots were cut, mixed, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently stored in a deep freezer at −80 °C.

2.2. Determination of Relative Electrical Conductivity (REL), Chlorophyll Fluorescence, and Chlorophyll Content

The relative electrical conductivity was determined as described by Zhang et al. [23]. For chlorophyll fluorescence measurement, each treatment included three replicates with three leaves per replicate, and the minimal fluorescence (F0) and maximal fluorescence (Fm) of PSII were determined; from these parameters, the maximum photochemical quantum yield of PSII (Fᵥ/Fₘ, calculated as (Fm − F0)/Fₘ) was derived, which is an indicator that reflects the integrity and functional efficiency of the photosystem II complex under frost stress. The third expanded leaf from the shoot apex was sampled for chlorophyll fluorescence determination. Each sample was first dark-treated for 20 min and then photographed with the plant chlorophyll fluorescence imaging system FC800-C/1010 (PSI, Brno, Czech Republic). The determination of the chlorophyll content was conducted as described by Su et al. [24].

2.3. Determination of Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content, Soluble Sugar Content, and Proline Content

The leaf or root samples (0.5 g) were ground in a pre-cooled mortar on an ice bath. Then, 8 mL of pre-cooled 50 mmol·L−1 pH 7.8 phosphate buffer solution (PBS) containing 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was added and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (1 mL) was mixed with 2 mL of thiobarbituric acid. Next, 1 mL of pH = 7.8 phosphate buffer and 2 mL of thiobarbituric acid was served as a blank control. Supernatant was then boiled in a water bath for 15 min. The absorbance was determined at wavelengths of 450 nm, 532 nm, and 600 nm, with 532 nm representing the MDA–TBA complex, 450 nm correcting for soluble sugar interference, and 600 nm correcting for turbidity from insoluble impurities.

The total soluble sugars were determined by using a colorimetric method [25]. The determination of the proline content and the preparation of standard curve were conducted following the methods described by Madebo et al. [26].

2.4. Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

Leaf samples (0.2 g) were taken, mixed with pre-cooled acetone, ground into a homogenate, and the volume was adjusted to 5 mL with acetone. The mixed sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was taken as a plant extract. Then, 1 mL of the sample extract was mixed with 0.1 mL of 5% titanium sulfate and 0.2 mL of concentrated ammonia water, followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The sediment was washed using acetone until the pigment was removed. Next, 5 mL of 2 mol·L−1 sulfuric acid was added to the sediment. The supernatant was measured at a wavelength of 415 nm by UV-visible spectrophotometry (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany).

Leaf samples (0.1 g) were mixed with 4 mL of pre-cooled PBS (pH 7.8). The mixture was thoroughly ground under ice bath conditions until the tissue was completely disrupted. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for enzyme analysis.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was quantified using the photochemical nitroblue tetrazolium-riboflavin assay. Plant extract (20 μL) was mixed with 1.5 mL of 0.05 mol·L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 300 μL of 65 mmol·L−1 methionine, 300 μL of 1 mmol·L−1 EDTA-Na2 solution, 300 μL of distilled water, 300 μL of 500 nmol·L−1 nitroblue tetrazolium, and 300 μL of 100 μmol·L−1 riboflavin. Absorbance was recorded at 560 nm immediately following the reaction. One unit (U) of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to inhibit 50% of the photochemical NBT reduction. Peroxidase (POD) activity was assayed using a reaction mixture containing 100 mL of 0.05 mol·L−1 PBS (pH 7.0), 37 μL of 0.05 mol·L−1 guaiacol, and 56 μL of 30% H2O2. The reaction was initiated by adding 20 μL of the enzyme extract. PBS was added instead of enzyme extract in the control. Absorbance at 470 nm was recorded at 30 s intervals for 3 min. One unit (U) of POD activity was defined as an increase in the absorbance of 0.01 per minute. The CAT reaction mixture consisted of 110 μL of 30% H2O2 and 100 mL of PBS (pH 7.0). Absorbance at 240 nm was measured every 20 s for 2 min. One unit (U) of CAT activity was defined as a change in absorbance of 0.01 per minute. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) reaction mixture was prepared by dissolving 0.04718 g of ascorbic acid and adding 11.2 μL of 30% H2O2 to 500 mL of PBS (pH 7.0). Plant extract (20 μL) was added to the CAT and APX reaction system. Absorbance at 240 nm was measured at 20 s intervals for 2 min. One unit (U) of APX activity was defined as a decrease in the absorbance at 0.01 per minute.

2.5. Determination of the Expression Levels of VvCBF-Related Genes in Leaves

The primers used for quantitative PCR of the CBF gene were designed according to Fang et al. [27] (Table S1). VvActin was used as the internal reference gene. Total RNA was extracted from leaves using an RNA extraction kit (Bioteke, Beijing, China). The extracted total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA templates using the HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Then, a 10 μL reaction mixture consisting of 5 μL 2 × ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix, 1.5 μL diluted cDNA, 0.25 μL forward or reverse primer (10 μmol·L−1), and 3 μL sterile water was used. The reaction program included pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s for annealing. Each cDNA sample was tested in triplicate, and the relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method [28].

2.6. Date Analyses

One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used for data analysis between different cultivars using SPSS Statistics 25.0 software, and multiple comparisons were performed by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). In addition, data from different temperature treatments were subjected to multiple paired t-tests, and the false discovery rate (FDR) method was used to correct multiple comparisons (threshold Q = 0.05). Charts were generated with GraphPad Prism 9.5.0. A correlation heatmap was generated using the OmicStudio tool (https://www.omicstudio.cn, accessed on 21 December 2025), with the Spearman correlation coefficient method applied for calculations. All experiments were conducted with three biological replicates, and the data represent the mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) of the three biological replicates.

The membership function method was used to comprehensively evaluate and rank the relevant indicators. The original data was standardized based on the method of Huang et al. [29]. The relative value data of each index were converted by the membership degree formula of fuzzy mathematical function.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Frost Stress on Photosynthetic Parameters

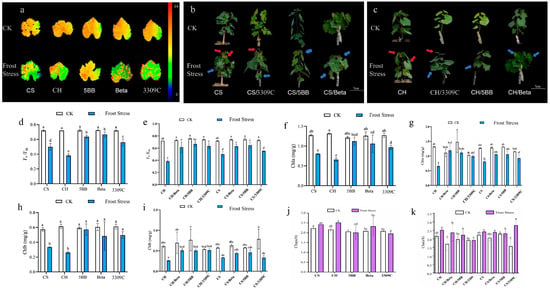

Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging of leaves from different own-rooted vines (Figure 1a), with the color scale (0 to 0.8, right panel), was conducted. The leaves of all own-rooted vines (CS, CH, 5BB, Beta, and 3309C) exhibited predominantly orange-yellow to yellow-green fluorescence signals, with values concentrated near 0.8. This suggests that, under ambient conditions, the PSII complexes of all tested grapevines maintained intact functions. Under frost stress, for grapevines like CS and CH, leaf fluorescence signals decreased sharply indicating severe frost-induced damage to their PSII complexes. In contrast, leaves of the Beta grapevine retained mostly yellow-green fluorescence, implying its PSII function was less affected by frost stress, thereby reflecting stronger resistance to spring frost. Leaf damage was assessed and compared between the own-rooted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ vines, as well as when these cultivars were grafted onto ‘Kober 5BB’, ‘Beta’, and ‘3309 Couderc’ under ambient and frost stress (Figure 1b,c). Results show that the shoot tips of own-rooted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ vines wilted and drooped under frost stress. In addition, yellow patches and necrotic lesions appeared on the leaves of this own-rooted CS and CH vines in response to frost stress. A similar response also occurred when CS and CH were grafted onto 3309C. In contrast, grafting CS and CH onto Beta and 5BB minimized the impact of frost stress on the shoots and leaves.

Figure 1.

Effect of frost stress on the chlorophyll fluorescence of own-rooted vines, as well as on the morphology and photosynthesis of own-rooted and grafted vines. CS: grape cultivar ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. CH: grape cultivar ‘Chardonnay’. 5BB: grape cultivar ‘Kober 5BB’. Beta: grape cultivar ‘Beta’. 3309C: grape cultivar ‘3309 Couderc’. CK: all vines were kept at 25 °C as a temperature control. For frost stress, all vines were kept at −2 °C for 3.5 h. (a) Chlorophyll fluorescence of own-rooted vines, (b,c) the morphology of grafted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’, red arrows indicate leaves showing distinct water-soaked lesions; blue arrows indicate the wilting of new shoots, (d,e) Fv/Fm, (f,g) chlorophyll a, (h,i) chlorophyll b, and (j,k) the chlorophyll a/b ratio. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test; the same lowercase letters indicate no significant differences.

The chlorophyll fluorescence parameter, Fv/Fm, was used to evaluate the impact of frost stress on photosynthesis in the leaves of own-rooted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘Chardonnay’, ‘Kober 5BB’, ‘Beta’, and ‘3309 Couderc’ vines. The Fv/Fm values in the leaves of these cultivars were between 0.7–0.75 at 25 °C (Figure 1d,e). The Fv/Fm values for these cultivars at −2 °C were significantly lower than chlorophyll fluorescence at 25 °C. Chlorophyll fluorescence of CH leaves decreased by 46.76% in response to frost stress. However, frost stress had less impact on the chlorophyll fluorescence in the leaves of the three rootstocks, 5BB, Beta, and 3309C, compared to a 25 °C temperature. In addition, the Fv/Fm values of Beta and 5BB under frost stress were significantly higher than those of the other cultivars. Frost stress led to a significant reduction in chlorophyll fluorescence (as indicated by Fv/Fm values) for own-rooted CS and CH vines, as well as for these cultivars when grafted onto Beta, 5BB and 3309C. While own-rooted CH vines displayed a marked decline in Fv/Fm under frost stress, grafting CH onto Beta, 5BB, and 3309C mitigated this effect; for CS, the frost-induced reduction in Fv/Fm was minimized when grafted onto the same three rootstocks compared to own-rooted plants.

Frost stress significantly reduced the levels of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b in the leaves of CS and CH, as well as 3309C (Figure 1f,h). Meanwhile, the frost stress-induced reduction in chlorophyll a and b led to a notable elevation in the chlorophyll a/b (Chl a/b) ratio, and CH leaves showed the highest Chl a/b ratio under frost stress (Figure 1j). In contrast, the Chl a/b ratio of Beta and 5BB remained relatively stable under frost stress, and their chlorophyll a and b levels were significantly higher than those of CH and CS, indicating less damage to their light-harvesting systems. Frost stress significantly reduced the chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b contents of own-rooted vines, accompanied by a marked increase in the Chl a/b ratio (Figure 1g,i,k). The elevated Chl a/b ratio in own-rooted vines corresponded to their low Fv/Fm values, suggesting impaired photosynthetic function. There was no significant difference observed in the chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b contents of the CH-grafted vines under frost stress. In terms of the Chl a/b ratio, CS/3309 exhibited the highest value among all grafted combinations under frost stress, which was significantly higher than most other combinations. These results confirm that appropriate rootstocks can effectively alleviate the damage of frost stress to the photosynthetic system of scions by regulating the Chl a/b ratio and maintaining chlorophyll a and b stability.

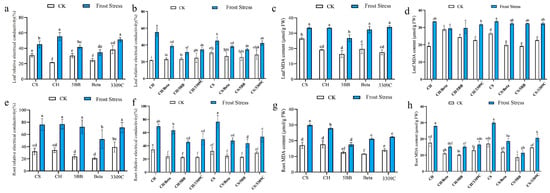

3.2. Cell Membrane Stability in Response to Frost Stress

Relative electrical conductivity (REL) was used to evaluate the impact of frost stress on the stability of cell membranes in the leaves and roots of the own-rooted CS, CH, 5BB, Beta, and 3309C vines. Results show that, compared with cell membrane stability at 25 °C, the REL of the leaves and roots significantly increased under frost stress (Figure 2a,e). Under frost stress, the REL of CH was the highest, at 55.33% stress, while Beta was the lowest, at 34.65%. Further, the REL of Beta roots at frost stress was significantly lower than the other grape cultivars used in this study. Results also show that frost stress significantly increased the MDA content in the leaves and roots of the cultivars examined in this study compared to vines grown at 25 °C. Overall, the MDA content in the roots of 5BB, Beta, and 3309C was lower than the levels in the CH and CS roots under low-temperature stress (Figure 2c,g).

Figure 2.

The effect of frost stress on the relative electrical conductivity (REL) and malondialdehyde (MDA) content in the leaves and roots of the own-rooted and grafted vines. The (a,b) REL in leaves, (c,d) MDA content in leaves, (e,f) REL in roots, and (g,h) MDA in roots. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test; the same lowercase letters indicate no significant differences.

Frost stress significantly increased the REL and MDA content of both leaves and roots in the scion and rootstock combinations (Figure 2b,d,f,h). The REL in both leaves and roots of own-rooted vines under frost stress was higher than those of the grafted combinations. The use of 5BB rootstock decreased, relative to the other scion–rootstock combinations, the REL in both leaves and roots when grafted with CS or CH. The MDA in the leaves of CH own-rooted vines under frost stress was the highest, reaching 49.20 μmol·g−1, indicating the frost stress resulted in severe damage to the leaf cell membrane. The MDA of CH/Beta leaves was not affected by frost stress. There was no significant difference in the leaf MDA content of the CS-grafted combinations under frost stress. The changes in MDA differed between roots and leaves. No significant difference in MDA accumulation was found between CH/Beta and CH/5BB in the roots or leaves. In contrast, CS/5BB significantly reduced the MDA level in roots under frost stress, which highlighted the rootstock roles in mitigating oxidative stress.

3.3. Effects of Frost Stress on the Osmotic Adjustment Substances in the Leaves

Quantification of total soluble sugars and proline were used as a proxy to evaluate the impact of frost stress on the osmotic stress in the leaves and roots of the own-rooted CS, CH, 5BB, Beta, and 3309C vines. Compared to 25 °C, frost increased the total soluble sugar content in the leaves and roots of CS, CH, Beta, and 3309C. The total soluble sugar of CH leaves increased 44.5% compared with the control group in response to frost stress (Figure 3a). There was no significant difference among the total soluble sugar content of different grape cultivar leaves under frost stress. The proline content of CH leaves under frost stress increased by 1.56 times compared with the control group, while the contents of 5BB had no significant difference compared with the control group (Figure 3c). The content of total soluble sugar in CS roots under frost stress was 10.68 μg·g−1 FW, which was significantly higher than that of the other cultivars. The content of total soluble sugar content in 5BB roots under frost stress was the smallest, at 3.82 μg·g−1 FW, which was significantly reduced compared to Beta and 3309C (Figure 3e). The proline content of CH roots under frost stress was significantly higher than the others. Roots of the three rootstocks maintained lower proline levels than CS and CH under frost stress (Figure 3g).

Figure 3.

The effect of frost stress on the soluble sugar content and proline in the leaves and roots of the own-rooted and grafted vines. The (a,b) soluble sugar content in leaves, (c,d) proline in leaves, (e,f) soluble sugar content in roots, and (g,h) proline in leaves. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test; the same lowercase letters indicate no significant differences.

There was no significant difference in the leaf soluble sugar content among all vines at 25 °C (Figure 3b). The 5BB-grafted vines had a significant decrease in soluble sugar content in the scion leaves compared with the own-rooted vines. Leaf soluble sugar was not affected under frost stress between the own-rooted vines and scions grafted with Beta or 3309C. Rootstocks exerted different effects on the leaf proline content in different scion–rootstock combinations (Figure 3d). Compared to 25 °C, frost significantly increased the proline content in the leaves of all combinations. Moreover, 3309C decreased the proline content of CH leaves at 25 °C. The proline content in the leaves of CS/5BB under frost was the highest among all the CS-rootstock combinations. There was no significant difference in the proline content in the leaves of CS own-rooted vines, CS/Beta, and CS/3309C under frost stress.

The root soluble sugar contents varied depending on the scion cultivars (Figure 3f). The soluble sugar of CH/3309C roots was higher than other CH–rootstock combinations under frost stress. However, the soluble sugar of CS roots was significantly higher than those of CS–rootstock combinations under frost stress. There was no significant difference in the proline content in the roots of all combinations under CK growing conditions (Figure 3h). Compared with other grafted vines, the increase in proline content in the 5BB roots was affected by scions under frost stress.

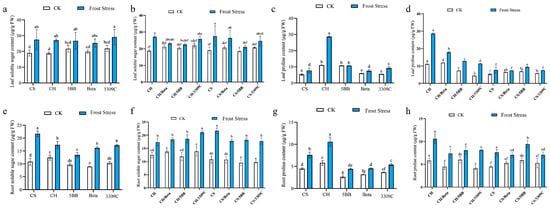

3.4. Effects of Frost Stress on Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

The impact of frost stress on the production of reactive oxygen species and antioxidants was evaluated in the ungrafted CS, CH, 5BB, Beta, and 3309C vines. At 25 °C, H2O2 was detected in the leaves and roots of these cultivars (Figure 4a,c). Overall, H2O2 significantly increased in both roots and leaves under frost stress compared to growth at 25 °C. In response to frost stress, the leaves and roots of ‘Chardonnay’ produced the greatest amount of H2O2 compared to the other cultivars examined. On the other hand, a lower level of H2O2 production was observed in the leaves and roots of 5BB and Beta, respectively, under frost stress. Compared with CK, frost significantly increased the hydrogen peroxide content in both leaves and roots (Figure 4b,d). Different rootstock cultivars significantly reduced the increase in H2O2 content in both scion leaves and roots under frost stress. The change in H2O2 contents of CH roots after frost stress were 61.94%, which was the largest among all the vines. Moreover, the 3309C rootstock–scion combination displayed markedly higher H2O2 contents in both the roots and leaves than the other two rootstocks.

Figure 4.

The effect of frost stress on the H2O2 content, POD enzyme activity, SOD enzyme activity, CAT enzyme activity, and APX enzyme activity of the own-rooted and grafted vines. The (a,b) H2O2 content in leaves, (c,d) H2O2 content in roots, (e,f) POD enzyme activity in leaves, (g,h) SOD enzyme activity in leaves, (i,j) CAT enzyme activity in leaves, and (k,l) APX enzyme activity in leaves. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test; the same lowercase letters indicate no significant differences.

Compared with the vines at 25 °C, frost stress increased the POD, CAT, and APX activities in the CS leaves. The POD of CS and Beta increased 80.1% and 77.08% after frost stress (Figure 4e,i,k). The SOD enzyme activities of all the three rootstocks increased, while the SOD enzyme activities of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ under frost stress were similar to 25 °C, (Figure 4g). A clear variation in the CAT enzyme activities was observed between CS and CH, with CS showing the highest activity and CH exhibiting levels similar to the three rootstock cultivars (Figure 4i). The variation range of APX activities in CS and CH were significantly higher than those in the rootstock cultivars, reaching 5.9 times and 3.4 times higher than the enzyme activities at 25 °C, respectively (Figure 4k). The SOD activity was least affected by frost and scion–rootstock combinations, whereas APX activity exhibited the greatest change (Figure 4h,l). Enzyme activities of POD, SOD, and CAT in ‘Chardonnay’ own-rooted vines were not affected by the temperature change. POD, CAT, and APX of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ own-rooted vines fluctuated upward in response to temperature changes. Then, 5BB and Beta markedly increased all antioxidant enzyme activities of CS leaves in response to temperature changes.

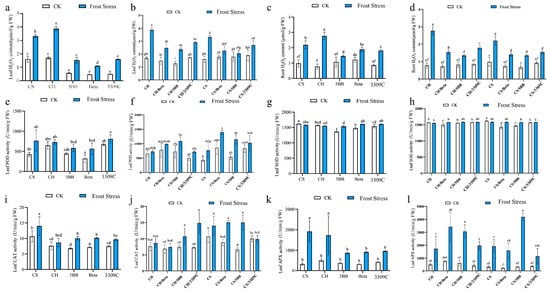

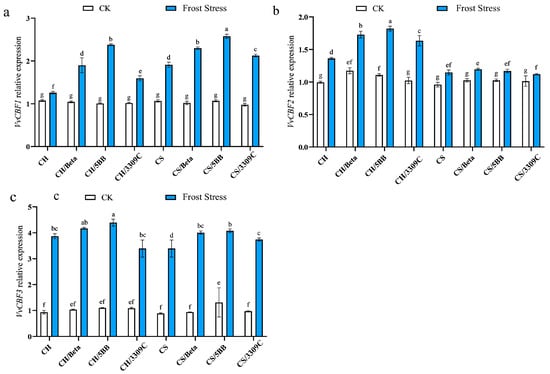

3.5. Effects of Rootstocks on CBF-Related Genes in the Leaves of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’

To better understand how rootstocks may increase frost response in grafted Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, the relative expressions of VvCBF1, VvCBF2, and VvCBF3 were assessed at ambient and frost stress. The expression of VvCBF1 was not statistically different between the own-rooted and grafted CH and CS vines at 25 °C (Figure 5a). However, a significant increase in the VvCBF1 expression occurred in own-rooted and grafted CH and CS vines in response to frost stress. Moreover, the upregulation of VvCBF1 was more substantial in the grafted compared to own-rooted CH and CS vines. But the variations were affected by scion and rootstock cultivars. There was no significant difference in the expression levels of the CBF genes between the CS own-rooted vines and CS-grafted vines under normal growth. The expressions of VvCBF2 were higher in the CH and rootstock combinations than the CS combinations (Figure 5b). VvCBF3 was three times upregulated after frost stress (Figure 5c). The relative expression of the CS-grafted vines was significantly higher than that of CS own-rooted vines. Moreover, 5BB affected the VvCBF expressions in both the scion cultivars under frost stress.

Figure 5.

The VvCBF gene expression in the leaves of the ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ scions grafted on different rootstocks under frost stress. The (a) VvCBF1 expression in the leaves, (b) VvCBF2 expression in the leaves and (c) VvCBF3 expression in the leaves. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test; the same lowercase letters indicate no significant differences.

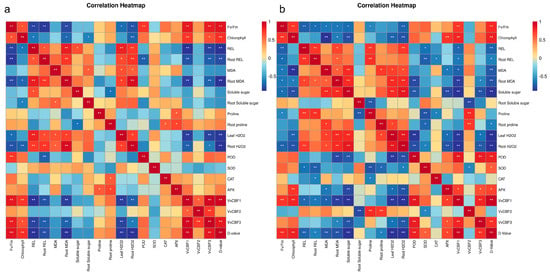

3.6. Heatmap

As shown in Figure 6a, the correlation heatmap was generated based on the Spearman method, with data presented as the mean of three technical replicates per group for a total of four groups: own-rooted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and three rootstock–scion grafting combinations. The membership function value was significantly positively correlated with the REL, Fv/Fm, root H2O2, and VvCBF1. Leaf REL and MDA were positively correlated with the Fv/Fm value, chlorophyll content, superoxide anion, and H2O2; in terms of antioxidant enzymes, APX was positively correlated with POD and SOD, and these three antioxidant enzymes were positively correlated with the leaf and root REL, MDA, H2O2, and leaf superoxide anion, and they were negatively correlated with osmotic adjustment substances. Leaf soluble sugar was positively correlated with leaf proline and negatively correlated with the remaining indicators.

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of the ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ scions grafted on different rootstocks under frost stress. (a) Correlation heatmap of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. (b) Correlation heatmap of ‘Chardonnay’. All values are the mean of three biological replicates per group, including the own-rooted vines and three rootstock–scion grafting combinations. The color gradient represents the Spearman correlation coefficient (red: positive correlation; blue: negative correlation). Asterisks indicate the significance of the correlation: *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01.

As shown in Figure 6b, the correlation heatmap was generated based on the Spearman method, with data presented as the mean of three technical replicates per group for a total of four groups: own-rooted ‘Chardonnay’ and three rootstock–scion grafting combinations. The membership function value was significantly positively correlated with REL, Fv/Fm, superoxide anion, and VvCBF2, and it was significantly negatively correlated with leaf soluble sugar. Leaf REL was significantly positively correlated with superoxide anion, Fv/Fm, and VvCBF2. Leaf H2O2 was positively correlated with leaf MDA, leaf superoxide anion, root H2O2, and root MDA. The four antioxidant enzymes were strongly correlated with each other and negatively correlated with leaf and root osmotic adjustment substances. Leaf soluble sugar was positively correlated with leaf proline, root soluble sugar, and root proline, and it was negatively correlated with the remaining indicators.

4. Discussion

4.1. Variation in Stress Adaptation Among Grapevine Cultivars

Grape cultivars exhibit differences in stress adaptation, which can be the result of breeding processes, and they are shaped by genotype and environment interactions [30]. Frost stress dramatically decreased the minimal fluorescence, maximal fluorescence, and the maximum photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II, especially in ‘Chardonnay’, in this study. Stress exposure is frequently associated with excessive ROS generation, heightened membrane lipid peroxidation, and a greater risk of photosynthetic impairment [7]. The stress responses are closely linked to the regulation of antioxidant defense pathways, such as H2O2 and APX. APX catalyzes the reduction in H2O2 to water using ascorbate as an electron donor, effectively limiting H2O2 accumulation and protecting cellular membranes from oxidative damage [31]. Our results demonstrate that ‘Chardonnay’ accumulates excessive H2O2 under frost stress while 5BB and Beta maintain low H2O2 levels, a pattern that is consistent with the ROS metabolism characteristics of spring frost-susceptible and spring frost-resistant grape varieties reported in previous studies [32]. This finding further confirms that ROS homeostasis is a key determinant of spring frost resistance in grape rootstocks and scions.

The accumulation characteristics of the total soluble sugars and proline in grape roots under frost stress in this study are highly consistent with previous findings on grape spring frost resistance. The CS roots showed a significantly higher increase in soluble sugars (10.68 μg·g−1 FW) than other materials, reflecting the typical spring frost resistance strategy of wine grape cultivars to cope with frost stress via rapid soluble sugar accumulation for osmotic adjustment [33]. The minimal increase in soluble sugars in ‘5BB’ roots (3.82 μg·g−1 FW) aligns with the spring frost resistance trait of ‘5BB’ rootstock, which maintains stable accumulation of osmotic regulators under frost stress [34].

Proline plays several protective functions under stress conditions, such as scavenging ROS, stabilizing cell membranes, and enzyme activities [9]. Metabolomic profiling demonstrated greater proline accumulation in V. amurensis than in V. vinifera under frost stress, supporting a metabolic basis for species-level tolerance differences [10]. V. amurensis, as the most cold-resistant Vitis species, is a key germplasm resource for cold-resistant grape breeding, which is used in interspecific hybridization (e.g., to develop ‘Beibinghong’) and molecular breeding (via cloning cold-responsive genes like VaCBF1) to enhance frost resistance in new grape varieties [35,36]. The activation or suppression of proline synthesis and catabolism interacts closely with cellular homeostasis and environmental adaptation [37]. CH roots exhibited significantly higher proline content, confirming that CH has a more active amino acid metabolic response to frost stress compared to other cultivars. In contrast, the three rootstocks (‘5BB’, ‘Beta’, and ‘3309C’) maintained lower proline levels than CS and CH, further verifying the differential frost stress response mechanisms between grape cultivars and rootstocks. Frost-tolerant rootstock maintain more stable membrane integrity, antioxidant capacity, and metabolic balance, therefore accumulating less proline to cope with stress [9].

4.2. Rootstocks Improved the Frost Stress Resistance of Scion

Rootstocks play a pivotal role in enhancing the frost stress resistance of grapevine scions, especially in ‘Chardonnay’, which was more susceptible to frost stress than ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ [38]. In our study, we showed that ‘Beta’ and ‘Kober 5BB’ enhanced the adaptation of both ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ to frost stress. Moreover, ‘3309 Couderc’ exerted a stronger beneficial effect on ‘Chardonnay’ than on ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. The selection of appropriate rootstocks mitigates the adverse effects of frost stress on scion growth and development.

Rootstocks impact the photosynthetic efficiency of scion, which impacts carbon assimilation and translocation [39]. For example, ‘Chardonnay’ vines grafted onto ‘1103P’ exhibit higher photosynthesis, which ensures more efficient carbon assimilation that supported vine vigor and fruit quality [40]. The rootstock genotype modulates the expression and activity of sugar metabolism and transport enzymes in the scion, thereby influencing soluble sugar accumulation patterns [41]. Here, the root soluble sugar levels of grafted ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ were lower than the own-rooted one under frost stress. The decline of soluble sugars may be due to a coordinated reallocation of resources under stress, which leads to a shift in the balance between carbon assimilation and carbon consumption [42]. The soluble sugar may be rapidly consumed through respiration to supply ATP and carbon skeletons for defense metabolite biosynthesis, or they could be diverted for cell wall reinforcement [43,44].

CBF-dependent signaling pathway is a central regulator of grapevine response and helps the plant cope with frost stress [28]. In this study, VvCBF1 expression was significantly influenced by rootstock type after low-temperature frost stress, whereas VvCBF2 expression varied according to the scion cultivar. CBF genes are subject to temporal regulation: CBF1 and CBF3 act as primary activators of cold responsive genes, while CBF2 serves as a negative regulator that fine tunes their expression. CBFs have been shown to positively regulate APX gene expression and significantly enhance AOX activity in Arabidopsis, rapeseed, and tomato, thereby improving ROS-scavenging activity. CBF also acts upstream of proline biosynthesis genes, which catalyzes the rate-limiting step in proline production and modulates the proline accumulation of grapevine [39,45].

4.3. Impact of Scion on the Tolerance of Rootstock and Practical Rootstock Selection

Although the rootstocks significantly influenced scion frost stress resistance, the effect of scion on rootstock performance is also noteworthy. In this study, the roots of scion and ‘Kober 5BB’ combinations maintained low levels of REL, MDA, and H2O2 under frost stress. The root systems of scion and ‘3309 Couderc’ combinations exhibited a higher degree of frost-induced injury. Scions modulate the rootstock stress responses through alterations in photoassimilate supply, hormonal cross talk, and signaling molecules [17,46]. Scion-derived molecular signals mediate root metabolic activity and resource allocation. Scion controls carbohydrate partitioning and source-sink dynamics, thereby affecting root growth and energy availability for stress defense in the rootstock [47]. Scion-derived signals, such as abscisic, microRNA, and small peptides, travel through the phloem and regulate rootstock gene expression related to stress responses [46]. The more stress-tolerant scions usually improved homeostasis in the rootstock, highlighting a reciprocal contribution of the scion to whole-plant stress acclimation. Scion genotype was involved in the recruitment of rhizosphere and root endophyte microbiomes, although its influence was less pronounced than that of the rootstock in determining plant growth and environmental adaptability [48].

Understanding the interactions between scion and rootstock is essential for developing strategies to enhance spring frost resistance in grapevines. Both scion and rootstock genotypes, as well as their interactions, are essential for the selection of optimal combinations. From a practical viticultural perspective, when selecting rootstocks, the compatibility between rootstocks and scion cultivars also needs to be considered. CS exhibits broad and favorable compatibility with 5BB, Beta, and 3309C, which aligns with its widespread application in viticultural grafting practice. In contrast, certain other grape varieties show severe incompatibility with ‘110R’ rootstock, which is characterized by delayed scion growth; reduced nutrient transport, such as ‘Riesling’; and ‘Pinot Noir’, which also exhibits poor compatibility with ‘SO4’ rootstock, leading to stunted vine development and lower photosynthetic efficiency [49,50].

Also, soil, as a key component of the vineyard ecosystem, plays a crucial role in mitigating frost stress on grapevines under field conditions. Loamy soils with high organic matter content can slow the rate of soil temperature decline and maintain a stable root-zone microclimate, reducing the risk of root frost damage [51]. This soil–rootstock interaction provides clear guidance for rootstock selection in cold-prone regions: in sandy soils with poor temperature buffering capacity, prioritizing rootstocks with strong spring frost resistance (e.g., 5BB) is essential to compensate for the limited mitigating effect of soil; in loamy soils with high organic matter, rootstocks with moderate spring frost resistance, such as 3309C, can be paired with organic amendment applications to achieve effective cold protection [52].

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the physiological, biochemical indices, and spring frost resistance of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (CS) and ‘Chardonnay’ (CH) grafted onto three rootstocks under frost stress. The rootstocks showed lower frost sensitivity, maintaining stable photosynthesis with an Fv/Fm decrease of less than 25% compared to 46.76% in own-rooted CH; intact cell membranes, with Beta exhibiting the lowest REL of 34.65%; and reduced ROS accumulation and robust antioxidant activity, with ‘Kober 5BB’ SOD activity increasing by over 130 U/g·min FW. Grafting enhanced scion spring frost resistance, with ‘Kober 5BB’ combinations performing best: CS/5BB exhibited the smallest increases in leaf REL and H2O2 content, with values of 34.76% and 9.28%, respectively; and CH/5BB showed no frost damage and the lowest O2− accumulation, with 12.64-fold APX elevation in CS/5BB and 3-fold higher VvCBF3 in grafted plants. Membership function evaluation ranked spring frost resistance as follows: CS/5BB > CS/Beta > CS/3309 > CS; CH/5BB > CH/Beta > CH/3309 > CH.

Grafting mediates the rootstock–scion interactions that modulate grape spring frost resistance. These findings guide viticulturists in cold-prone regions, such as northern China or temperate European vineyards, to select CS/5BB and CH/5BB for frost-resistant cultivation. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of rootstock–scion signaling will further facilitate breeding varieties with enhanced resilience to spring frost stress, improving vineyard resilience under climate change.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16010090/s1. Table S1: List of the primers used in this study; Tables S2–S4: Fv/Fm and the chlorophyll parameters of own-rooted and grafted vines and two-way ANOVA results; Tables S5–S7: The REL and MDA content of own-rooted and grafted vines and two-way ANOVA results; Tables S8–S10: The soluble sugar and proline content of own-rooted and grafted vines and two-way ANOVA results; Tables S11–S13: The H2O2 content and enzyme activity of own-rooted vines and two-way ANOVA results; Tables S14 and S15: The spring frost resistance affiliation function values for different grafted vines; and Table S16: The estimated survival rate of own-rooted and grafted vines under frost stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X., X.W. (Xianhang Wang), and X.W. (Xuefei Wang); methodology, C.H., Y.W., X.W. (Xianhang Wang), and H.L.; validation, C.H., W.Z., H.S. and H.L.; formal analysis, C.H., H.S., X.W. (Xianhang Wang), and H.L.; data curation, C.H., H.S. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H., H.L., W.Z., Y.W., X.W. (Xuefei Wang), and W.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.S., X.W. (Xuefei Wang), X.W. (Xianhang Wang), and Z.X.; visualization, C.H. and H.L.; supervision, Z.X.; funding acquisition, Z.X. and X.W. (Xuefei Wang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (grant number 2025BBF01005), Yunnan Association for Science and Technology Academician Expert Workstation (grant number 4050425138), Chinese Government Scholarships Program (grant number 202406300066), and the earmarked fund for CARS-grape (grant number CARS-29-ZP-06).

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable requests.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistants of Yuqiang Li from Shangri-La Winery Co., Ltd., Shangri-La, China and Numan Khan from College of Enology, Northwest A&F University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CBFs | C-repeat binding factors |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

References

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhai, Y.J.; Li, H.Y. Study on the temporal regularity of spring frost in wine grape planting areas of the eastern foot of Helan Mountain, Ningxia. J. Nat. Disasters 2017, 26, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.P.; Zhang, X.Y.; Cui, P.; Feng, Y.B.; Su, L.; Li, R.P.; Lou, S.H.; Xu, Z.H. Investigation on late spring frost of wine grapes in the eastern foot of Helan Mountain in 2020. Ningxia J. Agric. For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 61, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Del Zozzo, F.; Canavera, G.; Pagani, S.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S.; Frioni, T. Post-spring frost canopy recovery, vine balance, and fruit composition in cv. barbera grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpou, A.; Arvaniti, O.S.; Afratis, N.; Athanasiou, G.; Binard, F.; Zahariadis, T. Sustainable solutions for mitigating spring frost effects on grape and wine quality: Facilitating digital transactions in the viniculture sector. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, M.M.; Han, B.; Yin, Y.G.; Zhao, S.J.; Guo, Z.J. Identification and comprehensive evaluation of cold resistance of roots in six grape varieties. North. Hortic. 2021, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, M.G.; Teixeira, M.; Fontes, N.; Silva, S.; Graça, A. Climate impacts on vines in the upper Douro valley: Cold air pooling and unprecedented rainfall. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 68, 01035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahed, K.R.; Saini, A.K.; Sherif, S.M. Coping with the cold: Unveiling cryoprotectants, molecular signaling pathways, and strategies for cold stress resilience. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1246093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, W.K.; Gao, X.T.; He, L.; Yang, X.H.; He, F.; Wang, J. Rootstock-mediated effects on Cabernet Sauvignon performance: Vine growth, berry ripening, flavonoids, and aromatic profiles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadi, A.; Karimi, R.; Mahdei, K.N. Freezing tolerance and its relationship with soluble carbohydrates, proline and water content in 12 grapevine cultivars. Acta Physiol. Plant 2016, 38, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, F.; Liu, W.; Xiang, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, X.; Cheng, C.; Li, S. Comparative metabolic profiling of Vitis amurensis and Vitis vinifera during cold acclimation. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindric, P.; Korac, N. Frost Resistance of Grapevine Cultivars of Different Origin. Vitis 1990, 29, 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Warschefsky, E.J.; Klein, L.L.; Frank, M.H.; Chitwood, D.H.; Londo, J.P.; von Wettberg, E.J.; Miller, A.J. Rootstocks: Diversity, domestication, and impacts on shoot phenotypes. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.L.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, L.J. Study on cold resistance differences of shoots between Cabernet Sauvignon and Flame Seedless grapes with different rootstocks. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine 2014, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, R.P.; Pérez-Alfocea, F.; Cookson, S.J.; Ollat, N.; Vitale, A. Physiological and molecular aspects of plant rootstock-scion interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 852518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, K.; Yağcı, A.; Sucu, S.; Tunç, S. Responses of grapevine rootstocks to drought through altered root system architecture and root transcriptomic regulations. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitarra, W.; Perrone, I.; Avanzato, C.G.; Minio, A.; Boccacci, P.; Santini, D.; Gilardi, G.; Siciliano, I.; Gullino, M.L.; Delledonne, M.; et al. Grapevine grafting: Scion transcript profiling and defense-related metabolites induced by rootstocks. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, W.; Zheng, C. Interactions between rootstock and scion during grafting and their molecular regulation mechanism. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 308, 111554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Zeng, F.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mao, J.; Chen, B. Physiological, biochemical and molecular responses associated with drought tolerance in grafted grapevine. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, C.; Campbell, A.; Dumont, F. Rootstocks impact yield, fruit composition, nutrient deficiencies, and winter survival of hybrid cultivars in eastern Canada. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatini, P.; Howell, G.S. Rootstock Scion Interaction and Effects on Vine Vigor, Phenology, and Cold Hardiness of Interspecific Hybrid Grape Cultivars (Vitis spp.). Int. J. Fruit. Sci. 2013, 13, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert-Hache, A.; Inglis, D.; Kemp, B.; Willwerth, J.J. Clone and rootstock interactions influence the cold hardiness of vitis vinifera cvs. riesling and sauvignon blanc. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2021, 72, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, E.; Montague, T.; Kar, S. Secondary Bud Growth and Fruitfulness of Vitis vinifera L. ‘Grenache’ Grafted to Three Different Rootstocks and Grown within the Texas High Plains AVA. Int. J. Fruit. Sci. 2022, 22, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Wu, L.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xi, Z. Screening of efficient antifreeze agents to prevent low-temperature stress in vines. Agronomy 2024, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.Z.; Li, G.X.; Zhu, Q.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, C.J. Effects of phthalic acid on seed germination and seedling growth of pepper. North. Hortic. 2021, 24, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, A.; Pereira, S.; Bernardo, S.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.T. Biochemical analysis of three red grapevine varieties during three phenological periods grown under Mediterranean climate conditions. Plant Biol. 2024, 26, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madebo, M.P.; Li, W.A.; Zheng, Y.H.; Peng, J.I. Melatonin treatment induces chilling tolerance by regulating the contents of polyamine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and proline in cucumber fruit. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 3060–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, C.; Pervaiz, T.; Wang, X.; Luo, H.F.; Fang, J.G.; Shangguan, L.F. Whole genome identification of CBF gene families and expression analysis in Vitis vinifera L. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed 2023, 59, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Xi, Z. An AP2/ERF transcription factor VvERF63 positively regulates cold tolerance in Arabidopsis and grape leaves. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 205, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yan, L.; Lü, Y.; Ding, X.Y.; Cai, J.S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.K.; Zou, X.L. Evaluation and material screening of low-temperature tolerance during germination stage in Brassica napus. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2019, 41, 723–734. [Google Scholar]

- Baltazar, M.; Castro, I.; Gonçalves, B. Adaptation to Climate Change in Viticulture: The Role of Varietal Selection—A Review. Plants 2025, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.A.; Sharma, P.; Gill, S.S.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Khan, E.A.; Kachhap, K.; Mohamed, A.A.; Thangavel, P.; Devi, G.D.; Vasudhevan, P.; et al. Catalase and ascorbate peroxidase—Representative H2O2-detoxifying heme enzymes in plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 19002–19029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Zhu, Y.F.; Gao, B.; Hao, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of shoot cold hardiness of 12 grape rootstock varieties. Subtrop. Plant Sci. 2024, 53, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.Y.; Lei, T.X.; Li, W.; He, B. Changes in sugar content and cell structure of different tissues of Beta and Cabernet Sauvignon grape under low temperature stress. J. Fruit. Sci. 2015, 32, 604–611. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.D.; Chen, B.H.; Wang, L.J.; Mao, J.; Zhao, X. Screening and evaluation of physiological indexes for cold resistance of grape. Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occid. Sin. 2010, 30, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Song, R.G.; Lu, W.P.; Shen, Y.J.; Jin, R.H.; Li, X.H.; Guo, Z.G.; Liu, J.K.; Lin, X.G. Breeding of ‘Beibinghong’, a new ice wine grape cultivar. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine 2008, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Li, X.W.; Li, H.Y. Cloning and expression analysis of VaCBF1 transcription factor gene from Vitis amurensis. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 41, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Ashraf, M. Proline alleviates abiotic stress-induced oxidative stress in plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 4629–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, N.A.; Takale, S.R.; Patil, N.M.; Gat, S.D.; Nikumbhe, P.H.; Banerjee, K. Optimizing rootstock choice for enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant activity and yield of grapes under semi-arid climate. Appl. Fruit. Sci. 2025, 67, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Deng, L.; Huang, S.; Xiong, B.; Ihtisham, M.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, W.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, M.; Sun, G.; et al. Genetic relationship, SPAD reading, and soluble sugar content as indices for evaluating the graft compatibility of citrus interstocks. Biology 2022, 11, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Hu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.P. Effects of different rootstocks on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of one-year-old Chardonnay grapevines. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2016, 44, 213–215. [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens, S.; Ma, J.; Hanson, J.; Rolland, F. Sugar signals and molecular networks controlling plant growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, F.; Baena-Gonzalez, E.; Sheen, J. Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: Conserved and novel mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 675–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, T.L.; Wang, Z.X.; He, Y.F.; Xue, S.; Zhang, S.Q.; Pei, M.S.; Liu, H.N.; Yu, Y.H.; Guo, D.L. Proline synthesis and catabolism-related genes synergistically regulate proline accumulation in response to abiotic stresses in grapevines. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 305, 111373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete, A.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Martínez-Pérez, A.; Thompson, A.J.; Dodd, I.C.; Pérez-Alfocea, F. Unravelling rootstock × scion interactions to improve food security. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2211–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; Fan, P.G.; Li, S.H.; Liang, Z.C. Advances in understanding cold tolerance in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1733–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallaku, G.; Rewald, B.; Sanden, H.; Balliu, A. Scions impact biomass allocation and root enzymatic activity of rootstocks in grafted melon and watermelon plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 949086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lailheugue, V.; Darriaut, R.; Tran, J.; Morel, M.; Marguerit, E.; Lauvergeat, V. Both the scion and rootstock of grafted grapevines influence the rhizosphere and root endophyte microbiomes, but rootstocks have a greater impact. Environ. Microbiome 2024, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, S.N.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Höfle, R.; Kicherer, A.; Salles, J.F. Interactive Effects of Scion and Rootstock Genotypes on the Root Microbiome of Grapevines (Vitis spp. L.). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.P.; Howell, G.S.; Striegler, R.K. Cane and Bud Hardiness of Own-Rooted White Riesling and Scions of White Riesling and Chardonnay Grafted to Selected Rootstocks. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1988, 39, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascuñán-Godoy, L.; Franck, N.; Zamorano, D.; Sanhueza, C.; Carvajal, D.E.; Ibacache, A. Rootstock effect on irrigated grapevine yield under arid climate conditions are explained by changes in traits related to light absorption of the scion. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 218, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-L.; Du, Y.-P.; Duan, Q.-Y.; Zhai, H. Root temperature regulated frost damage in leaves of the grapevine Vitis vinifera L. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, B.; Bieniasz, M.; Błaszczyk, J.; Banach, P. The effect of rootstocks on the growth, yield and fruit quality of hybrid grape varieties in cold climate condition. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 49, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.