Abstract

Potassium (K) is crucial for global maize (Zea mays L.) production, yet the issue of “high K fertilizer input but low utilization efficiency” in K-rich soils of Xinjiang remains underexplored. A three-year field experiment (2020, 2021, 2024) in Xinjiang evaluated the effects of reduced K application on maize growth, grain yield (GY), and K-use efficiency. Five treatments were tested: K100 (136.0 kg K2O·ha−1), K60 (83.5 kg K2O·ha−1), K40 (55.6 kg K2O·ha−1), K0 (no K), and CK (no fertilizer). The research shows that K60 significantly outperforms K100 in terms of physiological parameters (plant height + 2.7–34.7%, leaf area index (LAI) + 6.3–26.8%, dry matter + 22.0–28.8%); GY and thousand kernel weight (TKW) improved by 6.9–15.1% and 9.3–30.3%, respectively. The potassium fertilizer productivity (PFPK) and potassium fertilizer agronomic efficiency (AEK) increased by 78–112.3% and 176.4–2085% compared to the K100. During the three-year period, the maximum net income of K60 reached 28,206 CNY·ha−1, which was 18.9–20.7% higher than that of K100. Regression analysis identified an optimal K rate of 82.2–85 kg·ha−1 for maximum yield. Least squares structural equation mode (PLS-SEM) and correlation analyses revealed that moderate K reduction enhanced vegetative growth and optimized yield structure, indirectly boosting yield, thereby directly driving net income. Thus, reducing K input can achieve “lower input with higher efficiency”, offering a practical basis for optimizing K management in arid-region maize systems.

1. Introduction

Potassium (K) is one of the three primary macronutrients essential for crop growth and plays a critical physiological role in agricultural production [1,2,3]. Maize (Zea mays L.) is a K-demanding crop whose growth and development are heavily dependent on adequate K supply [4,5,6]. K activates key enzymes such as starch synthase, facilitating the translocation of photosynthates to developing grains, thereby significantly influencing thousand kernel weight (TKW) and final yield [5,7,8]. Moreover, sufficient K nutrition enhances stem mechanical strength and reduces lodging risk, particularly during the jointing to grain-filling stages [9]. However, in current agricultural practice, K fertilizer is often applied excessively in pursuit of high yields [10,11,12]. Such over-application not only wastes finite K resources but also triggers a range of ecological and agronomic problems [13]. For instance, long-term application of K fertilizer at rates exceeding 62.5 kg·ha−1 in North China has been shown to decrease crop yield, reduce K use efficiency, and deplete soil available K and organic matter [14]. To address these challenges, modern technologies such as drip irrigation combined with fertilization offer effective strategies to improve resource use efficiency [15,16]. Qu et al. [17]. reported that drip irrigation can increase K fertilizer use efficiency by 14.2% compared to conventional irrigation methods. By adopting such precision nutrient management approaches, we are able to substantially reduce fertilizer waste, mitigate environmental pollution, and lower production costs in maize cultivation.

However, with the development of drip irrigation technology, many farmers still adhere to traditional fertilization concepts and fail to adjust the application rate of K fertilizer in accordance with the crop growth [15,16,18,19]. This contradiction is particularly prominent in regions such as Xinjiang, where the soil background value of K content is relatively high (1.99% in the 0–20 cm depth) [20]. In this region, the previously applied K rate often exceeds the actual needs of crops. This continuous excessive fertilization exacerbates the waste of resources and the adverse impact on soil; for instance, the excessively applied K fertilizer could be fixed by soil colloids or lost via leaching [21,22,23]. Moreover, it inhibits the absorption of other nutrients by crops through mechanisms such as ion antagonism, ultimately affecting the normal growth and yield formation of maize [2]. Additionally, there is ample research on reducing the application of nitrogen and phosphorus [24,25,26,27], but scarce research exists on the optimal rate of K fertilizer in the drip irrigation system of maize in Xinjiang. Therefore, clarifying the effect of decreasing K fertilizer application in this area is of great theoretical and practical significance for achieving the goal of “reducing fertilizer application without reducing yield” in this maize production area.

This study proposes the hypothesis that a moderate reduction in the use of K fertilizer will not significantly affect plant growth and maize yield. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a three-year replicated field experiment: (1) to explore the effects of different degrees of K fertilizer reduction on maize growth, yield components, and K fertilizer utilization efficiency; (2) to determine the optimal application threshold of K fertilizer using the yield-economic benefit model in Xinjiang, and to provide a quantitative basis for the formulation of precise fertilizer management strategies in this arid region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

Field experiments were conducted in 2020, 2021, and 2024. In 2020 and 2021, the experiments were located in the Xinjiang Agricultural Reclamation Academy’s Crop Water Use Efficiency Research Station (45°38′ N, 86°09′ E) in Shihezi City, on a piedmont alluvial plain at the northern foot of the Tianshan Mountains, with a typical temperate continental climate. In 2024, the experiment was conducted in the Cocodala of Ili River Valley (80°61′ E, 43°75′ N), which is also characterized by a temperate continental climate similar to that of Shihezi. The specific climatic conditions and soil properties of both sites are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Climatic conditions and soil properties of experiment sites in Shihezi and Cocodala.

2.2. Materials

The maize variety of this experiment was ZD985 (green maize), which was provided by Beijing Denong Seed Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The used commercial fertilizers including: urea (N ≥ 46.4%, granular; Xinjiang Xinlianxin Co., Ltd., Changji, China), monoammonium phosphate (N ≥ 12%, P2O5 ≥ 61%, powder; Guizhou Kai Phosphorus Group Co., Ltd., Guizhou, China), and potassium sulfate (K2O ≥ 51%, granular; Xinjiang Lop Nur Potassium Salt Co., Ltd., Ürümqi, China).

The source of the irrigation water was a deep well with a depth of 100 m; the salinity of the water was 0.2–0.3 g·L−1. The type of drip irrigation belt was a single-wing labyrinth drip irrigation belt (WDF16/2.6–100) produced by Xinjiang Tianye Company (Shihezi, China). The wall thickness was 0.18 mm, inner diameter of 16 mm, drip hole spacing of 300 mm, rated flow of 2.0 L·h−1, and the working pressure of 0.1–0.15 MPa. The pressure differential fertilizer applicator was produced by Laiwu Fenghuaxingnong Water-saving Irrigation Equipment Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China).

2.3. Experimental Design

In this experiment, both sites in Shihezi and Cocodala employed a randomized complete block design with three replications. The five K fertilizer treatments were as follows: 100% K (136.0 kg K2O·ha−1, K100, this implies the conventional K application rate by local farmers), 60% K (83.5 kg K2O·ha−1, K60), 40% K (55.6 kg K2O·ha−1, K40), 0% K (K0) and no fertilizer (Control, CK). Except for CK, the application rates of the other treatments (including K0) were the same, at 419.3 kg·ha−1 for N and 166.3 kg·ha−1 for P2O5. The 15 plots were separated from adjacent plots by 2.2 m-wide isolation strips, and each plot (110 m2) was 20 m long and 5.5 m wide. The irrigation and fertilization levels in each growth period are shown in Table 2. Maize sowing, harvesting, and sampling time are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

The irrigation volume and fertilization rate of experiment sites during maize growth stages.

Table 3.

Maize sowing, harvesting, and sampling time.

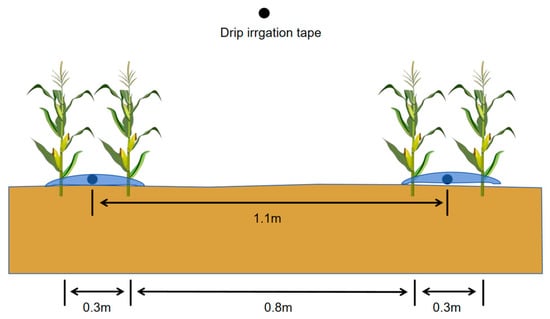

This experiment used the subsurface drip irrigation method. A combined seeder performed three synchronized operations: (1) laying drip tapes, (2) applying plastic film mulch, and (3) sowing maize seeds. Drip tapes were spaced 110 cm apart, and each plot had independent water meters and fertilizer tanks for precise irrigation and fertilization control. Maize was planted in alternating wide–narrow rows (80 cm wide, 30 cm narrow), achieving a target density of 1.26 × 105 plants·ha−1 with a within-row spacing of 14.4 cm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of cultivation mode for maize.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Plant Height

During the flowering stage of maize, the height of 10 maize plants was measured from the soil surface to the top of the male inflorescence, and then which were calculated the average value of plant height [28].

2.4.2. Leaf Area Index (LAI)

During the flowering stage, the 10 maize plants with consistent growth conditions were selected in each plot and the lengths and widths of their leaves were measured. The related parameters were calculated as follows [29]:

where ∑ represents the sum of leaf areas, L is leaf length, B is leaf width, LAP is leaf area per plant, N is number of plants per unit area, Aland is unit land area.

LAP = ∑ (L × B) × 0.75

LAI = LAP × N ÷ Aland

2.4.3. Dry Matter

Aboveground biomass (leaves, stems, and reproductive organs) was harvested at the flowering and maturity stages. The samples were dried in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min and then at 75 °C until they reached a constant weight, and were weighed and recorded on a balance with an accuracy of 0.01 [30].

2.4.4. Yield and Yield Composition

Yield was measured on 5 October 2020, 6 October 2021. and 3 October 2024, respectively. For each plot, 20 ears were randomly selected, weighed for fresh weight, then dried to constant weight and reweighed. Yield per unit area was calculated based on a standard moisture content of 14%. Meanwhile, the following yield-related traits were recorded: (1) Ear length: measured along the grain axis from the ear base to the tip using a vernier caliper; (2) Ear width: measured at the thickest part of the middle ear, perpendicular to the grain axis; (3) Rows per ear: counted as the total number of complete grain rows per ear; (4) Kernel number per row: counted as the number of complete grains from the base to the top of 2–3 randomly selected representative complete rows per ear, with the average value taken; (5) Thousand Kernel Weight (TKW): Three random sets of 1000 grains from this mixture were weighed. The mean value of these three measurements represented the plot’s TKW. Subsequently, the yield-determining factors were analyzed [31].

2.4.5. Fertilizer Agronomy Efficiency and Fertilizer Specific Productivity

The calculation formulas of fertilizer agronomic efficiency and fertilizer specific productivity were as follows [32]:

where FPFK represents the agronomic efficiency of K fertilizer, AEK represents the partial productivity of K fertilizer, Y represents the grain yield of the K fertilizer application treatment, and Y0 represents the grain yield of the non- K fertilizer application plot. KA indicates the amount of K fertilizer applied per unit area.

PFPK = Y/KA

AEK = (Y − Y0)/KA

2.4.6. Economic Benefit

The economic benefits of maize production were calculated as follows [33]:

where GR is grain revenue, GY is grain yield, Pg is grain price, SR is straw revenue, SW is straw fresh weight, Ps is straw price, NER is net economic return, TC is total production cost. Yuan stands for Currency of a country.

GR = GY × Pg

SR = SW × PS

NER = (GR + SR) − TC

The grain price is 1.5 CNY·kg−1 (average of three markets). Straw is priced at 0.35 CNY·kg−1. Fertilizer N costs 2.2 CNY·kg−1, fertilizer P costs 6.8 CNY·kg−1, and fertilizer K costs 4.6 CNY·kg−1. Other production costs, excluding fertilizers, are 11,850 CNY·ha−1.

2.5. Data Analysis

A one-way ANOVA using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 was conducted to assess the significant impact levels of fertilizer application rates on yield components and growth indicators. The LSD test was used to examine the significance of mean values under each treatment at p < 0.05. Image mapping, data fitting, and calculation of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) were performed using Origin Pro 2025. The potential relationships among fertilization, growth shape, yield and economy were identified using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM) constructed by the “plspm” R package (R v3.4.0). Given the significant differences in climatic conditions and soil properties among the experimental sites in different years (Table 1), year was treated as a repeated validation factor in the statistical analysis to verify the consistency and stability of the effects of different potassium fertilizer application rates.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Reduced K Fertilizer on Maize Growth Parameters

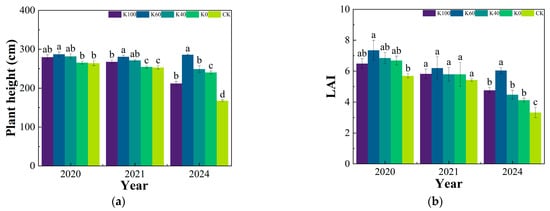

During a three-year trial period, both the plant height and leaf area index (LAI) of maize showed a trend of “first increase then decrease” as the amount of K fertilizer decreased (Figure 2). The K60 treatment showed the best growth performance in all treatments and experimental years. In 2020 and 2021, there was not any significant difference in the maize growth parameters (plant height and LAI) between the K60 and the K100 treatment. In 2024, these growth parameters in the K60 treatment were markedly higher than those of the K100, K40, K0 and CK treatments (p < 0.05). Specifically, in 2024, the plant height of K60 treatment (269.5 cm) was 19.7% higher than that of K100 treatment (212.1 cm), and the LAI of K60 treatment (6.0) was 20% higher than that of K100 treatment (4.8). The LAI in 2024 was the lowest of all the treatments in three years. Compared to the CK treatment in 2024, the relative increase in LAI was 82.1% in the K60 treatment and 43.6% in the K100 treatment; and similarly, compared with CK treatment in 2020 and 2021, the relative increase of LAI was 19.7–49.1% in the K60 treatment and 7.4–38.1% in the K100 treatment. These results indicate that, compared with CK treatment, the relative increase in the K60 treatment was significantly higher than that in the K100 treatment, and the 2024 K100 value was also significantly higher than in the previous two years (2020 and 2021). This experiment demonstrated that relative to conventional K application method (K100 treatment), moderate reduction in K fertilization rate could enhance the maize growth, and the reduced amount of 83.5 kg·ha−1 (K60 treatment) may be the appropriate K fertilization rate.

Figure 2.

Effect of potassium application rate on (a) plant height, and (b) leaf area index (LAI) of maize. Note: The error bars represent the standard error (SE), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the various treatment methods for each indicator within the same year. All comparisons were determined to be significant at the p < 0.05 level by the LSD test.

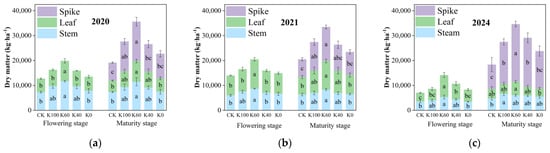

3.2. Effect of Reduced K Fertilizer Application on the Accumulation and Distribution of Dry Matter in Maize

Dry matter (DM) is a critical indicator for assessing crop growth status and yield potential, and it is closely correlated with final economic yield. With decreasing K fertilizer application, the DM accumulation in the experimental field exhibited a parabolic trend, which was characterized by an initial increase followed by a decline (Figure 3). The application of K fertilizer has a significant impact on the accumulation and distribution of DM at each growth stage. At the flowering stage in 2020, K60 treatment totally accumulated 18,890 kg·ha−1 of DM, which was 18.5% higher than that of the K100 treatment (p < 0.05). The DM of leaf and stem, respectively, reached 8174 kg·ha−1 and 11,716 kg·ha−1, and the sum accumulation of leaf and stem DM was significantly higher than other treatments. These results demonstrated that moderate reduction in K fertilizer may enhance the assimilation and accumulation of DM in vegetative organs.

Figure 3.

Effect of potassium application rate on (a) 2020, (b) 2021, and (c) 2024 dry matter of maize. Note: different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments for each index within the same growth period. All comparisons were considered significant at p < 0.05 in the LSD test unless noted.

At maturity, the total DM for the K60 treatment was 35,603 kg·ha−1, with ear DM at 15,857 kg·ha−1 (44.5% of the total), 28.8% higher than that of the K100 treatment. The K60 treatment thus showed a pronounced advantage in partitioning DM into reproductive organs, thus laying the foundation for high yield. The results of DM in 2020 were similar to those in 2021. In 2024, the total DM of K60 treatment reached 14,176 kg·ha−1 at the flowering period, which was significantly increased by 64% compared to the K100 treatment. Additionally, the total DM of K60 treatment was 34,640 kg·ha−1 at maturity, which was 25.9% higher than that of the K100 treatment.

In summary, the K60 treatment demonstrated a significant advantage over the K100 treatment in terms of DM accumulation. During the flowering stage, it significantly promoted the accumulation of photosynthetic products in leaves and stems, and it was more effective at translocating DM to the ear during the maturity stage.

3.3. Yield and Its Components

Over the three-year experiment, TKW and GY consistently ranked highest among all treatments (Table 4). In the Shihezi region in 2020, the K60 treatment achieved a TKW of 445.0 g, which was 13.3% higher than that of K100 (392.7 g), corresponding to a yield increase of 9.3% compared to K100. In 2021, the TKW of K60 in the same region reached 406.0 g, marking a 15.1% increase over K100 (352.8 g), with a synchronized yield increase of 16.2%. In 2024, in the Cocodala region, the K60 treatment recorded a TKW of 591.8 g, 6.9% higher than that of K100 (553.3 g), and the yield showed a significant increase of 30.3% compared to K100.

Table 4.

Changes in maize yield and yield components under different K fertilizer treatments.

A quadratic model was fitted to the relationship between maize yield (y, kg·ha−1) and K fertilizer application rate (x, kg·ha−1) across the three-year study (Table 5). The model showed that maize yield peaked at 15,971.7 kg·ha−1 when the K application rate was 82.2 kg·ha−1.

Table 5.

Establishment of K fertilizer application rate equation and analysis of yield estimation results.

3.4. K Fertilizer Utilization Efficiency

There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in K fertilizer utilization efficiency among the K reduction treatments. A three-year pooled analysis showed that partial factor productivity (PFPK) increased monotonically as K application declined. The K60 regime consistently outperformed K100, registering gains of 78.0%, 88.9% and 112.5% in 2020, 2021 and 2024, respectively (Table 6). The K fertilizer agronomic efficiency (AEK) followed the same pattern, with K60 exceeding K100 by 176.4%, 300.9% and 2085% in 2020, 2021, and 2024; all differences were statistically significant. Therefore, under the experimental conditions of this study, the K60 treatment simultaneously increased PFPK and AEK, achieving higher K-use efficiency.

Table 6.

Potassium fertilizer productivity and agronomic efficiency under different K fertilizer treatments.

3.5. Economic Benefits

Across the three-year trial, net income exhibited a unimodal response to decreasing K rates, peaking under the K60 regime (Table 7). Net income for K60 was 28,206 CNY·ha−1 in 2020, 22,916 CNY·ha−1 in 2021 and 19,129 CNY·ha−1 in 2024, representing 20.7–23.6% increases over the K100 treatment. Furthermore, this indicates that excessive application of K fertilizer does not guarantee an increase in final yield. Moderate reduction in K fertilizer thereby enhanced net income for farmers in arid and semi-arid regions.

Table 7.

Economic benefits analysis under different K fertilizer treatments.

Based on the quadratic regression model of the average economic benefits over three years, y = −1.0784x2 + 183.2441x + 14,480.3748 (R2 = 0.930), when the K fertilizer application rate x is 85.0 kg·ha−1, the net income peaks at 22,261 CNY·ha−1. Therefore, applying an appropriate amount of K fertilizer is the key to improving the economic benefits of maize in Xinjiang.

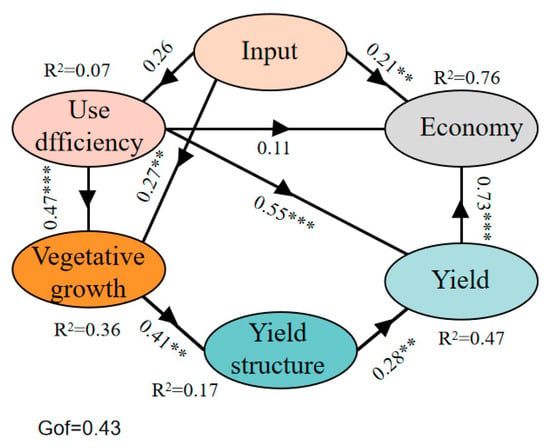

3.6. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model Analysis

The partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) revealed the key pathways and driving mechanisms of maize growth and yield formation under different K application levels (Figure 4). The results show that the efficiency of K fertilizer utilization has a significant positive effect on both vegetative growth and yield structure, and the path coefficients are 0.47 (p < 0.001) and 0.27 (p < 0.01), respectively, indicating that improving the efficiency of K fertilizer utilization can enhance plant growth vigor, promote the synthesis and accumulation of photosynthetic products, and facilitate the redistribution of DM to the reproductive organs, thereby optimizing yield composition. Additionally, yield structure had a significant positive impact on final yield, with a path coefficient of 0.28 (p < 0.01), suggesting that yield formation was directly driven by the grain filling capacity and grain weight. The model also indicated that yield was the most critical factor for economic benefit improvement, with a path coefficient of 0.73 (p < 0.001), indicating that changes in yield can directly determine production income.

Figure 4.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling showing the pathways through which K fertilizer use efficiency influences vegetative growth, yield structure, grain yield, and economic benefit. Ellipses denote latent variables, and arrows indicate standardized path coefficients. Significance levels: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Model fit: Gof = 0.43.

3.7. Spearman Correlation Between Maize Yield and Key Growth Parameters

The Spearman correlation analysis further verified the close relationship between maize growth indicators and yield factors at the statistical correlation level (Figure 5). The results showed that maize yield was significantly positively correlated with total biomass (TB), TKW, plant height, and LAI. Among them, the correlation between TKW and yield was the highest (r = 0.99, p < 0.01), indicating that the grain filling capacity had the most direct impact on the final yield, and showing that sufficient growth potential and DM accumulation is the basis for high yield formation. Furthermore, both plant height and leaf area index showed a highly significant positive correlation with yield (r = 0.93, p < 0.01). This indicates that appropriate K application can enhance the photosynthetic area of plants and increase photosynthetic efficiency, thereby promoting the accumulation of DM and increasing yield. The overall correlation results are highly consistent with the path model of PLS-SEM: enhancing growth potential, expanding photosynthetic area and increasing DM accumulation are the core processes for achieving high yield. TKW was the most crucial factor determining yield. Reasonable K application is an effective way to improve these indicators.

Figure 5.

The relationship between maize yield and key growth parameters. Note: TB: total biomass; EL: ear length; SW: spike width; KN: kernel number; RN: row number; TKW: thousand kernel weight; GY: grain yield. Each circle represents the correlation between two variables. The color of the circle indicates the direction of the relationship, while the size of the circle reflects the strength of the correlation. Statistical significance levels are indicated by asterisks.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Reduced K Fertilizer Application on the Growth Characteristics of Maize

Appropriate reduction in K fertilizer application can significantly promote the growth of maize. K is one of the three major nutrients essential for plant growth [34]. Its supply significantly impacts various physiological processes and overall development [35,36]. Our research has revealed that as the amount of K applied decreased, the plant height, LAI and aboveground DM of maize all showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. Specifically, the K60 treatment increased plant height, LAI, and aboveground DM by 2.7–19.7%, 6.9–20% and 18.5–25.9%, respectively, compared to the K100 treatment. This indicates that although K application is beneficial to maize growth, excessive application of K does not provide additional benefit and may even have an inhibitory effect. This finding aligns with the earlier research results of Wang et al. [37], whose study indicates that excessive K application reduces K fertilizer utilization efficiency and yield, leading to K surplus in the soil. This may be because excessive K application strongly inhibits root absorption and root-shoot transport of magnesium, leading to magnesium deficiency, which in turn disrupts key physiological processes such as photosynthesis, carbohydrate distribution, and nitrogen metabolism, ultimately reducing plant biomass and yield [2].

Notably, LAI differed between the two study regions. The LAI of maize in Cocodala is generally lower than that in Shihezi (Figure 2b). The research conducted by Alfaro et al. [38] indicates that an increase in precipitation can enhance soil drainage flow, strengthen the priority flow and large-pore flow processes, accelerate the migration of soluble K and exchangeable K in the soil, and thereby promote the leaching loss of K. The research conducted by Xu et al. [8] revealed that in areas with intense leaching, only when the K fertilizer input reaches the compensation threshold can it effectively promote leaf expansion and biomass accumulation. Therefore, in K-rich areas of Xinjiang, appropriately reducing the amount of K fertilizer not only does not inhibit growth but also promotes the accumulation of DM in maize.

4.2. Effect of Reducing K Fertilizer Usage on Yield, K Utilization Efficiency, and Economic Benefits

Beyond growth traits, the impact of K reduction on yield and resource economics is equally critical. Wang et al. [39] indicated that an appropriate application rate of K fertilizer can better achieve a synergistic balance between maize yield and K use efficiency. In this study, the K60 treatment not only achieved the highest grain yield but also had significantly higher PFPk and AEk than the conventional high-rate K application (K100), indicating that moderate reduction in application did not sacrifice yield but instead improved resource utilization efficiency. This result is consistent with that of Niu et al. [40]: they observed that when K input exceeded the maximum demand threshold of the crop, yield no longer increased, and K utilization efficiency significantly decreased. Similarly, Liu et al. [41] also reported in their experiments that as the application rate increased, yield showed a trend of increasing initially and then decreasing, while fertilizer utilization rate continuously decreased. The main reason for this phenomenon is that excessive application of K can reduce the effectiveness of nitrogen and phosphorus through ion competition and interfere with the absorption of calcium, magnesium, and other cations through antagonistic effects, ultimately leading to a simultaneous decline in nutrient utilization efficiency and yield [42,43]. It is worth noting that this study further found that excessive application of K (K100) not only failed to increase yield but instead led to a 6.9–15.1% decrease in yield compared to the K60 treatment, which is consistent with the trend of Yang et al.’s [44] results on winter wheat.

4.3. Analysis of the Production Mechanism Based on PLS-SEM and Spearman Correlation

To unravel the underlying mechanisms linking K efficiency to yield, we employed PLS-SEM and correlation analyses. This study further clarified the physiological and ecological pathways through which the utilization efficiency of K fertilizer affects the formation of maize yield: K use efficiency does not directly drive yield but indirectly enhances it by regulating vegetative growth and yield structure. Coskun et al. [45] proposed that K indirectly affects the grain filling process of cereal crops by regulating the distribution of photosynthetic products and the carbon-nitrogen metabolic balance. The results of this study are consistent with this mechanism: the PLS-SEM model shows that the utilization efficiency of K fertilizer significantly promotes vegetative growth (such as plant height and LAI) and optimizes the yield structure (such as TKW), thereby indirectly enhancing the final yield. At the same time, the Spearman’s analysis indicates that the correlation coefficient between TKW and yield was as high as 0.99, and the correlation coefficient between total biomass and yield was 0.98, further supporting the decisive role of efficient dry matter transport during the grain-filling period in the formation of yield. This discovery also supports the conclusion of Yang et al. [46] that K increases LAI and extends the photosynthetic functional period, increasing total biomass accumulation and optimizing harvest index. It is worth noting that under drip irrigation conditions in the arid region of Xinjiang, the K60 treatment can maintain or even enhance these physiological processes while reducing inputs, indicating that moderate K reduction does not weaken the physiological regulatory function of K, but achieves the coordinated optimization of resources and yield by improving utilization efficiency.

5. Conclusions

Optimizing the K application rate can effectively enhance maize growth, DM, GY, and net income. In maize production in high-K areas of Xinjiang, the K fertilizer application rate is strongly recommended to be 82.2–85 kg·ha−1. Compared with the local conventional fertilization, this optimal rate reduces the K application rate by 35.7–37.8%. Additionally, the integration of PLS-SEM and Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed that enhancing K use efficiency boosts grain yield primarily by promoting vegetative growth and optimizing yield-related traits such as TKW and total DM. In the high-K areas of Xinjiang, reducing the application of K fertilizer can minimize resource waste, enhance the efficiency of K fertilizer utilization, and provide strong technical support for precise fertilization of maize in the arid regions of Xinjiang.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and F.L.; methodology, L.Z. and F.L.; software, G.C.; validation, L.Z.; formal analysis, G.C.; investigation, G.W. and J.Z.; resources, J.Z. and F.L.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. and F.L.; visualization, G.C.; supervision, J.Z., G.W. and F.L.; project administration, G.W.; funding acquisition, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Tian chi Talent Project (Grant No. 2025QNBS012) from the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32360444); the Key Research and Technology Development Special Project of Yili Prefecture (Grant No. YZD2024A02) from the Science and Technology Department of Yili Prefecture; the High-Level Talents Project of Yili Normal University (Grant No. 2023RCYJ01) and the Yili Normal University High-Level Talents Project (Grant No. 2023RCYJ18) from Yili Normal University.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets obtained during this study are accessible from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Duan Tianjiang, Tian Yuxin, Liu Mengjie, Wang Zhenjia, Liu Dao and other colleagues who contributed to the field experiment. We are also extremely grateful to the reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jiliang Zheng was employed by the company Xinjiang Xinlianxin Energy Chemical Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Damalas, C.A.; Koutroubas, S.D. Potassium supply for improvement of cereals growth under drought: A review. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 3368–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Cakmak, I.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Guo, S. Synergistic and antagonistic interactions between potassium and magnesium in higher plants. Crop J. 2021, 9, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, G.; Pei, Y.; Chen, J.; Song, X.; Sun, J. Transcriptional and Metabolic Responses of Maize Shoots to Long-Term Potassium Deficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 922581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Agus, F.; Susanti, Z.; Buresh, R.; Cassman, K.G.; Dobermann, A.; Agustiani, N.; Aristya, V.E.; Batubara, S.F.; Istiqomah, N.; et al. Potassium limits productivity in intensive cereal cropping systems in Southeast Asia. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasaya, A.; Yasir, T.A.; Sarwar, N.; Farooq, O.; Rehman, A.U.; Mubeen, K.; Ali, M.; Affan, M.; Aziz, A. Foliage applied potassium improves stay green, photosynthesis and yield of maize (Zea mays L.) under rainfed condition. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2021, 26, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.A.; Wang, X.; Zafar, S.A.; Noor, M.A.; Hussain, H.A.; Azher Nawaz, M.; Farooq, M. Thermal stresses in maize: Effects and management strategies. Plants 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Du, X.; Wang, F.; Sha, J.; Chen, Q.; Tian, G.; Zhu, Z.; Ge, S.; Jiang, Y. Effects of potassium levels on plant growth, accumulation and distribution of carbon, and nitrate metabolism in apple dwarf rootstock seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lai, T.Z.; Li, S.; Si, D.X.; Zhang, C.C. Effective potassium management for sustainable crop production based on soil potassium availability. Field Crops Res. 2025, 326, 109865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Guo, D.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Zheng, C.; Li, X.; He, F.M.; Tang, Q.Q.; Yu, J.; Ren, H. Optimising potassium levels improved the lodging resistance index and soybean yield in maize-soybean intercropping by enhanced stem diameter and lignin synthesis enzyme activity. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Yuan, X.H.; Zhang, Z.X.; Yang, X.Y.; Ai, C.; Wang, Z.H.; Fan, Q.L.; Xu, X.P. Revisiting potassium-induced impacts on crop production and soil fertility based on thirty-three Chinese long-term experiments. Field Crops Res. 2025, 322, 109732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Liu, Y.; Hou, L.; Geng, Z.C.; Hu, F.A.; Xu, C.Y. Impact of organic fertilizer substitution and chemical nitrogen fertilizer reduction on soil enzyme activity and microbial communities in an apple orchard. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.W.; Niu, X.X.; Chen, B.Z.; Pu, S.H.; Ma, H.H.; Li, P.; Feng, G.P.; Ma, X.W. Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and diversity and yield of cotton. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1295722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Qiu, L.X.; Zhang, T.J.; Gaoyang, E.; Zhang, L.L.; Wang, L.L.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.F.; Dong, J.; et al. Long-term application of controlled-release potassium chloride increases maize yield by affecting soil bacterial ecology, enzymatic activity and nutrient supply. Field Crops Res. 2023, 297, 108946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Z.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.L.; Bai, Y.L. Identifying the critical potassium inputs for optimum yield, potassium use efficiency and soil fertility through potassium balance in a winter wheat-summer maize rotation system in North China. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 254, 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Nie, J.X.; Yin, H.L.; Luo, Y.H.; Shu, C.H.; Cheng, Q.Y.; Fu, H.; Li, B.; Li, L.Y.; Sun, Y.J.; et al. Can the integration of water and fertilizer promote the sustainable development of rice production in China? Agriculture 2024, 14, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Wang, R.P.; Kang, S.Z.; Du, T.S.; Tong, L.; Kang, J.; Gao, J.; Ding, R.S. Quantifying the differences in the effects of management practices on maize yield and water use efficiency in the North China Plain and Northwest China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yin, S.; Feng, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, C. Effects of drip irrigation coupled with controlled release potassium fertilizer on maize growth and soil properties. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 301, 108948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Yang, X.-Y.; He, X.-H.; Xu, M.-G.; Huang, S.-M.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.-R. Effect of long-term potassium fertilization on crop yield and potassium efficiency and balance under wheat-maize rotation in China. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Liu, W.F.; Parsons, D.; Du, T.S. Optimized irrigation and fertilization can mitigate negative CO2 impacts on seed yield and vigor of hybrid maize. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 952, 175951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China, E.M. Background Values of Soil Elements in China; China Environment Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1990; pp. 356–357. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.Y.; Shen, C.Y.; Chen, S.H.; Tang, G.M.; Li, Q.J.; Yan, C.X.; Geng, Q.L.; Fu, G.H. Yield of wheat and maize and utilization efficiency of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in Xinjiang. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2022, 14, 2762–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.M.; Wu, Z.C.; Li, J.X.; Lu, Z.L.; Luan, S.X.; Hu, S.X.; Liu, X.Y.; Li, N.; Han, X.R. A nine-year study: Continuous application of biochar achieves efficient potassium supply by modifying soil clay mineral composition and its potassium adsorption sites. J. Soils Sediments 2025, 25, 1829–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, T.; Wall, D.P.; Casey, I.A.; Humphreys, J.; Forrestal, P.J. Integrating soil potassium status and fertilisation strategies to increase grassland production and mitigate potassium management induced metabolic disorders in grazing livestock. Soil Use Manag. 2025, 41, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.F.; Tang, J.H.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zhang, N.; Luo, X.Y.; Hu, D.P.; Xu, W.X. Manure in combination with optimal topdressing with nitrogen fertiliser improved growth, grain yields and the efficiencies of water and nitrogen use in winter wheat in the Xinjiang Oasis drylands. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.X.; Riaz, M.; Xia, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Jiang, C.C. Effect of biochar and nitrogen fertilizers on maize seedling growth and enzyme activity relating to nitrification. Soil Use Manag. 2023, 39, 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.Y.; Wang, C.J.; Wang, H.T.; Yao, Z.L.; Qiu, X.F.; Wang, J.D.; He, W.Q. Biogas slurry topdressing as replacement of chemical fertilizers reduces leaf senescence of maize by up-regulating tolerance mechanisms. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Qiang, R.; Lu, E.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Q. Response of soil microbial community structure to phosphate fertilizer reduction and combinations of microbial fertilizer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 899727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, H.; Ren, Y.; Liu, H.; Du, W. Effects of nitrogen fertilization rate and seeding density on the forage yield and quality of autumn-sown triticale in an alpine grazing area of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Grass Forage Sci. 2024, 79, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Shi, W.; Liu, L.; Jing, B. Poly-γ-glutamic acid enhances corn nitrogen use efficiency and yield by decreasing gaseous nitrogen loss and increasing mineral nitrogen accumulation. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 249, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.-D.; Liu, J.-L.; Zhu, L.; Luo, S.-S.; Chen, X.-P.; Li, S.-Q.; Lee Hill, R.; Zhao, Y. The effects of mulching on maize growth, yield and water use in a semi-arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 123, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Malhi, S.S.; Vera, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of rainfall harvesting and mulching technologies on water use efficiency and crop yield in the semi-arid Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, R.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, F. The effect of nutrient deficiencies on the annual yield and root growth of summer corn in a double-cropping system. Plants 2024, 13, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, N.; Gao, W.; Jiang, C.Z.; Ma, R.S.; Usman, S.; Yang, X.L. Optimizing nitrogen fertilization for forage maize production to maximize profit and minimize environmental costs in a rainfed region in China. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 2569–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, H.; et al. Quantitative effects of potassium application on potato tuber yield, quality, and potassium uptake in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Zhao, X.-H.; Xia, L.; Jiang, C.-J.; Wang, X.-G.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.-Q. Effects of potassium deficiency on photosynthesis, chloroplast ultrastructure, ROS, and antioxidant activities in maize (Zea mays L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustr, M.; Soukup, A.; Tylova, E. Potassium in root growth and development. Plants 2019, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Hu, W.H.; Ning, X.L.; Wei, W.W.; Tang, Y.J.; Gu, Y. Effects of potassium fertilizer and straw on maize yield, potassium utilization efficiency and soil potassium balance. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, M.A.; Alfaro, M.A.; Jarvis, S.C.; Gregory, P.J. Factors affecting potassium leaching in different soils. Soil Use Manag. 2004, 20, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ai, Z.P.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Leng, P.F.; Qiao, Y.F.; Li, Z.; Tian, C.; Cheng, H.F.; Chen, G.; Li, F.D. Impacts of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) fertilizers on maize yields, nutrient use efficiency, and soil nutrient balance: Insights from a long-term diverse NPK omission experiment in the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2024, 318, 109616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, K.; Assaraf, M.; Imas, P. Potassium fertilization on maize under different production practices in the north China plain. Agron. J. 2011, 103, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, M.; Cui, J.; Li, B.; Fang, C. Effects of straw carbon input on carbon dynamics in agricultural soils: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveen, A.; Singh, S. The role of potassium under salinity stress in crop plants. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 52, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, S.T. Nutritional disorders between potassium, magnesium, calcium, and phosphorus in soil. In Optimization of Plant Nutrition: Refereed Papers from the Eighth International Colloquium for the Optimization of Plant Nutrition, Lisbon, Portugal, 31 August–8 September 1992; Fragoso, M.A.C., Van Beusichem, M.L., Houwers, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. Optimized application of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium enhances yield and quality by improving nutrient uptake dynamics in winter wheat with straw return. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 5028–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, D.; Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. The nitrogen–potassium intersection: Membranes, metabolism, and mechanism. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 40, 2029–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yu, W.; Li, Q.; Zhong, D.; He, J.; Dong, H. Latitude, planting density, and soil available potassium are the key driving factors of the cotton harvest index in arid regions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.