Abstract

Canopy configuration affects crop yields by optimizing radiation interception and/or use efficiency in greenhouses. Although tomato metrics have been reported, the effects of row spacing on growth, yield and radiation for different cultivars are not well documented. Here, we examined tomato growth, yield, radiation interception and use efficiency in a greenhouse with four row spacing patterns (T1: 50 cm, T2: 60 cm, T3: 70 cm and T4: 80 cm) and two tomato cultivars (Aomeila1618 and Zhefen202) over a two-year period. A constructed intermediate model was used to simulate tomato radiation interception. Although there were great differences in the genotypes between the two selected cultivars, 50 cm (T1) was the optimal row spacing to produce a larger leaf area per unit of land area, intercept more radiation and ultimately achieve higher yield than the other three row spacing patterns (T2, T3 and T4). The mean total radiation interception across years and cultivars was 559.43 MJ m−2 in T1, 2.8–3.8% higher than in the other three row spacing patterns. Despite similar dry matter and RUE to Aomeila1618, Zhefen202 in the narrow strip used light more efficiently. These results will help to optimize canopy structures by taking cultivar-specific responses in RUE and growth traits into consideration for high-efficiency tomato production in greenhouses.

1. Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) is one of the most widely cultivated crops, both in China and globally, owing to its distinctive flavor and high nutrient content [1,2]. Due to the low temperatures in early spring, tomato—a warm-loving plant—is cultivated in greenhouses in southeastern China. For convenient field management, tomatoes are often cultivated in strips with two or more rows separated by empty paths. These canopies not only reduce intraspecies interactions but also increase light interception through the empty paths. Piao et al. [3] have shown that strip canopies can increase radiation utilization by 1% compared to uniform spacing. The effect of row spacing on light interception is more evident than that of spacing between plants [4,5]. However, excessively dense planting can cause shading within the canopy, thereby limiting light absorption by old leaves in the lower canopy [6]. Therefore, a suitable distance between rows is necessary for healthy tomato production.

The yield of tomato crops is determined by the total biomass production, the distribution of this biomass and the dry matter of fruits. The main factors that affect tomato productivity are the accumulated light interception, climatic conditions, management and the production period. Therefore, improvements in the above aspects should be implemented to achieve increases in productivity, such as light interception and plant configuration. Row spacing is a key factor that directly affects the micro-environment within the canopy, including light distribution, air circulation and nutrient competition. Moderate row spacing can provide adequate space for tomato plant growth, adjust resource allocation within the canopy and have a profound impact on plant morphology, physiological metabolism, and ultimately, yield and quality [7].

Leaf area and plant height are critical morphological traits that reflect plant growth status and resource capture capacity. The leaf area determines the amount of solar radiation intercepted by the canopy, which is the primary energy source for photosynthesis. Plant height, on the other hand, affects the vertical distribution of leaves within the canopy and the competition for light among neighboring plants. Studies have shown that row spacing can significantly alter the growth dynamics of leaf area and plant height for crops such as maize [8]. A narrower row spacing may lead to increased competition for light, resulting in taller plants and smaller individual leaf areas, while a wider row spacing may provide more space for leaf expansion but could reduce the overall plant density and, thus, the total light interception at the canopy level [9]. However, the effects of row spacing on leaf area and plant height may vary depending on cultivars. Therefore, there is a need to quantify the responses of these key growth parameters to variations in row spacing across different cultivars.

Light is the primary energy source in greenhouses, affecting the growth and development of tomatoes [10]. Numerous studies have shown that light intensity can affect tomato growth [11,12,13]. Higher light intensity leads to greater dry weight and stem diameter, but results in a decrease in height [11]. Moreover, within a certain range, higher light intensity leads to improved photosynthesis [11], although excessive light intensity causes photoinhibition [13,14]. Radiation use efficiency (RUE) is a good indicator to evaluate radiation utilization by plants [15] and to quantify crop production in relation to photosynthesis, as it combines both the radiation intercepted by crops and dry matter. Well-designed row spacing can optimize the spatial arrangement of leaves to maximize radiation capture, while also ensuring sufficient light penetration to the lower canopy layers to maintain photosynthetic activity [9,16]. Changes in radiation interception, in turn, can influence the RUE, as excessive light interception in the upper canopy may lead to light saturation and photoinhibition, while insufficient interception may result in the underutilization of solar radiation [17]. Studies have shown that the RUE varies with row spacing, but the direction and magnitude of this effect depend on factors such as cultivar, environmental conditions and management practices [9]. However, studies on the effects of row spacing on the radiation interception and RUE between different cultivars remain scarce, limiting our ability to develop comprehensive resource-efficient greenhouse tomato production systems.

To calculate the fraction of radiation interception in homogeneous canopies, either a single optical probe or a linear quantum sensor equipped with multiple optical probes can be used to measure light intensity across different canopy layers, which are either affected by measurement location or do not allow for the continuous recording of radiation intensity. However, due to light from the empty paths in strip canopies, the above methods are inadequate in calculating the fraction of radiation interception and, consequently, the radiation interception in heterogeneous canopies directly. In recent years, many plant models have been constructed to aid in our understanding of the interactions among genotypes, the environment and management. In these models, radiation interception is one of the most important functions as it drives photosynthesis and, therefore, growth. For homogeneous crop canopies, the fraction of intercepted radiation can simply be estimated using the Lambert–Beer law, which is a function of the leaf area index (LAI) and light extinction coefficient (k) [18]. For heterogeneous canopies, Goudriaan [19] developed a “block model”, based on a few equations, to estimate daily radiation interception under a uniform overcast sky. The block model has been widely used to estimate radiation interception and utilization in cotton [20], maize/peanut strip intercropping [21], wheat/maize relay strip intercropping [22] and maize/soybean strip intercropping [23].

The functional–structural plant (FSP) model is a widely used model for simulating radiation interception in all kinds of crop canopies. In addition to high computational demands, FSP models have many parameters to be estimated, resulting in high data requirements. However, they are able to simulate realistic plant architectures and canopy structures, consider three-dimensional (3D) daily incoming light from the sky and typically use a ray-tracing algorithm to quantify the 3D distribution of light interception at leaf level. Li et al. [24] developed an “intermediate model” without using k. This approach represents the crop canopy as a “block” and calculates radiation interception using a ray-tracing algorithm to simulate the radiation intercepted by heterogeneous canopies. The intermediate model considers the light environment, canopy structure and also the optical properties of leaves and film. Despite the absence of plant architecture, the intermediate model has a goodness of approximation comparable to Goudriaan’s block model and FSP models in calculating radiation interception in heterogeneous canopies. Due to the lack of plant architecture estimation, k estimation in tomato homogeneous canopies, here, we used the intermediate model to simulate tomato radiation interception. Therefore, we conducted a tomato experiment with four row spacing patterns and two cultivars to quantify (1) the row spacing effects on the growth of the leaf area and plant height and (2) the yield, radiation interception and radiation use efficiency of each tomato cultivar in response to row spacing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Greenhouse Experiments

The single-span greenhouse experiments were conducted in 2023 and 2024 in Jiashan, Zhejiang, southeast China (30°49′ N, 120°52′ E). The altitude of the experimental site is 3.7 m. The region has a typical subtropical monsoon climate, with an annual mean temperature of 15.6 °C, 1978.3 h of annual mean sunshine and 236 frost-free days. The soil is clay loam with a bulk density of 1.23 g cm−3, a total nitrogen content of 2.25 g kg−1, available phosphorus content of 38 mg kg−1, available potassium content of 204 mg kg−1 and a pH of 6.75 in the topsoil (0–20 cm).

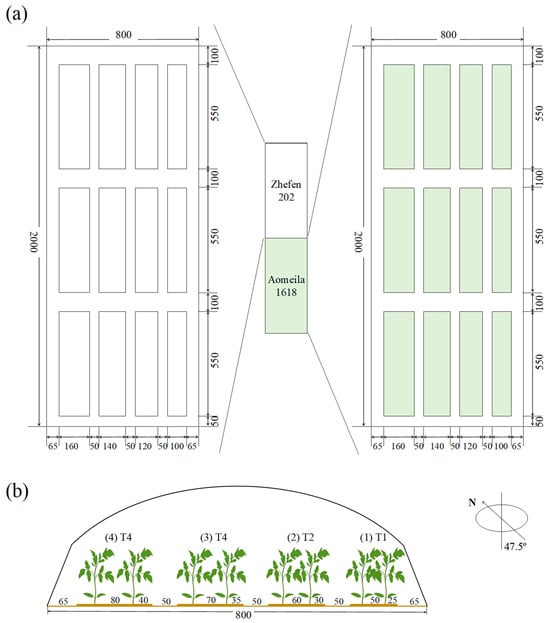

To determine how row spacing affects the yield and radiation use of tomato and the difference between cultivars, eight treatments comprising four row spacing patterns and two tomato cultivars (Aomeila1618 and Zhefen202 were from Zhejiang Yinong Seed Industry, Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) were conducted, with three replicates per treatment. The tomato strip was a canopy with strips consisting of two tomato rows. The layout of the plots and strips was separated by empty paths (Figure 1). For convenient drip irrigation and to ensure tomato vine support, the block design was not completely randomized. However, the positions of cultivars and row spacing treatments were alternated between years, resulting in opposite positioning; for instance, the block of Aomeila1618 in 2023 changed to Zhefen202 in 2024. The order of treatments was T1, T2, T3 and T4 from right to left in 2023, and this changed to T4, T3, T2 and T1 from right to left in 2024. In the crop strips, the row spacing patterns were 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4). The plant distance in the row was 35 cm. The empty path width was 50 cm. Therefore, the plant density per m2 of the whole area (strip area + path area) was 3.8 plants m−2 for T1, 3.4 plants m−2 for T2, 3.0 plants m−2 for T3 and 2.7 plants m−2 for T4.

Figure 1.

Layout of plots (a) and row configurations of four row spacing patterns (b) in the single-span greenhouse in 2023 (unit: cm). The treatment position was opposite in 2024, including the position of cultivars and row spacing patterns. The row spacing patterns are 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4). The plant distance in the row is 35 cm. The empty path width between two tomato strips is 50 cm.

Tomato plants were transplanted into a single-span greenhouse. The greenhouse size was 8 m × 40 m × 2.5 m (width × length × height) with southwest–northeast row orientation in both years. The crop strip size was 1.0 m × 5.5 m for T1, 1.2 m × 5.5 m for T2, 1.4 m × 5.5 m for T3 and 1.6 m × 5.5 m for T4. Plastic films were used on the tomato strip before transplanting to keep them warm in the early spring, and to prevent weeds and water evaporation. Tomato cultivars “Aomeila1618” and “Zhefen202” were transplanted on 20 March in 2023 and 28 March in 2024. These two cultivars were indeterminate growth plants. Aomeila1618 has larger plant coverage, longer internodes and leaves [25]. However, Zhefen202 has small plant coverage, shorter internodes and small leaves, compared to Aomeila1618 [26]. The top bud was cut by hand after three leaves had grown above the fifth fruit cluster to avoid unlimited tomato growth. Lateral buds were also cut to maintain only one shoot. Plants were uprooted after all fruits were harvested on 8 July in 2023 and on 11 July in 2024. Basal organic fertilizer was applied in all plots and in both years before transplanting at a rate of 30 t ha−1 to ensure healthy tomato growth. Two top dressings of 67.5 kg K ha−1 each were applied at fruit setting and swelling stages. One top dressing of 78 kg P ha−1 was applied at fruit setting stage. Chemical fertilizers of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and potassium sulfate were used as sources of P and K. Irrigation was applied following local management and farmers’ practice. Pests and diseases were controlled chemically according to farmers’ practice. Due to the plastic films used in the whole growing season, there were no weeds in the field.

2.2. Measurements

Leaf area and plant height of the tomato plants were determined seven times in 2023 (7 April, 24 April, 6 May, 19 May, 2 June, 19 June and 8 July) and eight times in 2024 (28 March, 12 April, 28 April, 11 May, 24 May, 6 June, 21 June and 11 July). Three plants were sampled in each plot. These sample plants were selected from both rows for T2 and T3, and only from the inner row for T1 and T4, to avoid any border row effects. The sampled plants were selected randomly to represent the average level of the plot, while maintaining a distance of at least 1 m between gaps in the canopy formed by the previous sampling.

The length (distance from the base of leaf vein to the leaf tip) and width (at the widest point) of each leaf were measured. The leaf area was calculated as leaf length × leaf width × 0.5468 [27]. Leaf area index (LAI) in whole occupied land area was calculated as the ratio of leaf area per plant to total land use of the plant (strip area + path area). LAI in the pure strip area was inferred by the ratio of leaf area to strip area to identify the effect of density from the path’s geometry effect. The plant height was recorded along with the natural height, i.e., the height from the soil surface to the highest point in the field.

The photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) intensity above the strip canopy and at the bottom of the canopy was measured seven times at noon in 2024 (28 April, 11 May, 24 May, 6 June, 21 June, 2 July and 11 July) by using an LP-80 linear quantum sensor (AccuPAR, Decagon, Pullman, WA, USA). For all plots, the horizontal measurement positions were placed between the two tomato rows in the strips. The vertical positions between the two tomato rows were placed 20 cm above the canopy and 1 cm above the soil surface. The relative light intensity was calculated as the ratio of light intensity at the bottom of the strip canopy to the value above the canopy.

In the two years studies, a total of ten plants from three replicate plots in each treatment were selected to determine the fruit yield, where each plot contained three or four plants. These sample plants were selected from both rows with T2 and T3 only taken from the inner row with T1 and T4 to avoid border row effects. Because of the plants’ different maturity times, tomato fruits were harvested when the color turned pink or red according to the farmer’s knowledge and experience. All sample plants in both years represented the average plant status in the plots. Using these plants, we determined the yield components, including fruit number per plant, single-fruit weight and fruit shape index (fruit length/fruit diameter). The aboveground dry matter, which was used to calculate the radiation use efficiency (RUE), was calculated as the sum of the dry matter of the internodes, leaves and fruits. We recorded the dry weight of the matured fruits at different maturity times for the plants and used these values to determine the aboveground dry matter. The samples used to determine dry matter were oven-dried at 105 °C for 30 min and then at 85 °C until constant weight was reached.

2.3. Radiation Calculation

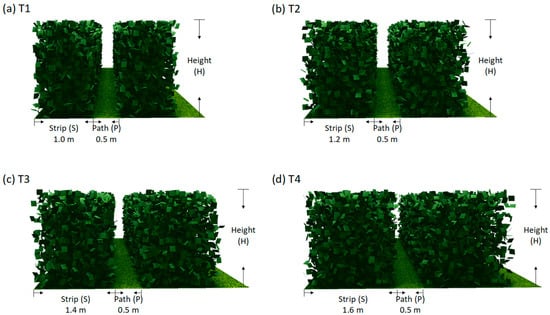

The cumulative radiation interception of tomatoes during the growing season was estimated using an intermediate model, which was implemented in the GroIMP platform version 1.5 (https://www.sourceforge.net/projects/groimp/ (accessed on 29 August 2025)) [24,28]. In the model, the strip canopy was similar to block, which was composed of small square leaves (Figure 2) [23]. The leaf area for the single leaf in the block was set to 100 cm2 [24,29]. The number of leaves in the strip canopy was calculated as the strip canopy leaf area divided by the size of a single leaf. Using a spherical distribution, the leaves were randomly distributed within the canopy, meaning that the x, y and z coordinates were each drawn from a uniform distribution [24]. We used a spherical distribution to specify the leaf elevation angles and a uniform distribution relative to north to specify the azimuth angles [24]. Strip height dynamics were modeled using plant height as the input.

Figure 2.

Cross-sections through the tomato strip crop canopy in the intermediate model with row spacing patterns of 50 cm ((a), T1), 60 cm ((b), T2), 70 cm ((c), T3) and 80 cm ((d), T4) at 70 days after transplanting (unit: cm). The empty path was 50 cm in each treatment.

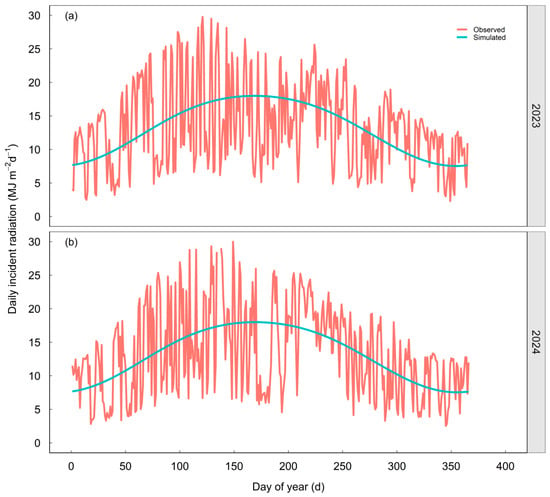

The latitude and day of the year were used to calculate the daily course of incident radiation intensity, achieving a pure effect of row spacing design and tomato cultivars without the influence of weather data variations (Figure 3) [30,31]. The observed daily incident radiation data were obtained via a radiometer (ET007, Insentek Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) located in 30.82° N and 120.87° E. The incident radiation data were recorded every 30 min. An array of 24 directional light sources was used to simulate direct radiation. An array of 72 directional light sources in a hemisphere was used to simulate diffuse radiation [31,32]. This diffuse radiation dome was randomly rotated at each time step. The relative light intensity of each diffuse radiation source depended on its position in the dome. The reverse Monte Carlo ray-tracing algorithm in GroIMP was used to simulate radiation interception in different treatments [28].

Figure 3.

Comparison of observed and simulated daily incident radiation in the whole year of 2023 (a) and 2024 (b). Simulated radiation values were calculated based on Spitters [30] with mean atmospheric transmissivity (τ) of 0.332, which was calculated based on the incident radiation data at a weather station from 2023 to 2024. The calculation equations of simulation values were programmed on GroIMP platform. The simulated values also took the cloud effect into consideration.

For all model simulations, the starting day was set to day 80 in 2023 and day 88 in 2024; the ending day was set to day 190 in 2023 and day 194 in 2024. The latitude was set to 30.82° N, which determines the angle of the light sources. Based on the incident radiation data during 2023 and 2024, 0.332 was set as the atmospheric transmissivity. The transmissivity of the greenhouse film was set to 0.78. The angle between row orientation and geographic north was set to 47.5°. In daily radiation, the proportion of diffuse radiation was 0.675 [33]. The leaf optical property parameters were set to a reflectance of 0.145 and a transmittance of 0.045 for PAR [34].

In the intermediate model, the simulations were run with 2 × 10 plants (one tomato strip) in the experiment. The plot size was set to 3.5 m × 1.5 m for T1, 3.5 m × 1.7 m for T2, 3.5 m × 1.9 m for T3 and 3.5 m × 2.1 m for T4. To minimize border effects related to the incoming light, the replicator functionality in GroIMP was used to copy plots 40 times in both the x and y directions. Each simulation was run three times.

2.4. Data Analysis

To simulate tomato growth, a flexible sigmoid function [35] was used to determine the dynamics of leaf area per plant in each treatment.

where LA is the value of tomato leaf area (m2), LAm is the maximum value of LA (m2), te is the time at which this maximum LAm was reached (d) and tm is the time at which the maximum growth rate was reached (d).

Because the tomato plants had an initial height prior to transplanting, a flexible sigmoid function with a vertical offset was used to determine the dynamics of plant height in each treatment.

where H is the value of tomato plant height (m), a + Hm is the maximum value of H (m), te is the time at which this maximum, a + Hm, was reached (d) and tm is the time at which the maximum growth rate was reached (d).

Radiation use efficiency (RUE, g MJ−1) was calculated as the ratio of final aboveground dry matter (DM, g m−2) to total accumulated radiation interception (RI, MJ m−2) during the growing season.

Nested models (mle2) in the ‘bbmle’ package (v1.0.25.1) of R version 4.5.1 [36] were used to avoid overfitting and to analyze the differences in leaf area and plant height. Equations (1) and (2) were fitted to the data of the four row spacing patterns and two tomato cultivars. Multiple models were fitted to represent different assumptions on the parameters across different treatments [37,38]. Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was used to determine which model was the best fitted [39]. Based on the selected model, leaf area and plant height were determined to be different or the same among treatments. The fitted parameter values are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

The list of fitted parameter values for the growth of leaf area (LA) per plant for greenhouse tomatoes across different row spacing patterns during the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons.

Table 2.

The list of fitted parameter values for the growth of plant height (H) for greenhouse tomatoes across different row spacing patterns during the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant differences (LSD) tests in the ‘stats’ (v4.5.1) and ‘agricolae’ package (v1.3-7) of R version 4.5.1 to assess the effects of row spacing on yield, yield components, dry matter, radiation interception and use efficiency in each year at the 5% (p = 0.05) level. Mixed-effect models were used to analyze row spacing and cultivar effects on the yield components, dry matter, radiation interception and RUE. The analysis of these indicators was conducted at the plot level, which was three in each treatment. The ‘ggplot2’ package (v3.5.2) [40] was used to produce figures. The values presented in the figures and tables are means ± SEs.

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Yield Components

Row spacing and tomato cultivar both affected tomato yield (p < 0.05) (Table 3). When the row spacing was 50 cm (T1), the tomato crops had the highest yield with 115.9 ± 3.9 t ha−1 for Aomeila1618 and 102.9 ± 3.8 t ha−1 for Zhefen202 in 2023, and 105.6 ± 7.8 t ha−1 for Aomeila1618 and 137.7 ± 9.5 t ha−1 for Zhefen202 in 2024. There was no yield difference for Aomeila1618 in the other three row spacing treatments (T2, T3 and T4). There was also no yield difference for Zhefen202 when row spacing was 70 cm or 80 cm (T3 and T4).

Table 3.

Fruit yield and yield components for greenhouse tomatoes in different row spacing patterns during the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons.

Except for Zhefen202 in 2024, row spacing had no effect on tomato single-fruit weight. The single-fruit weight of Zhefen202 was heavier than that of Aomeila1618. Although row spacing did not affect the fruit shape index (p > 0.05), a difference was observed for the fruit shape index between tomato cultivars (Table 3). The fruit shape index for Zhefen202 ranged from 0.81 ± 0.01 to 0.89 ± 0.01, which was higher than for Aomeila1618 (ranging from 0.77 ± 0.01 to 0.82 ± 0.01). Overall, Zhefen202 had heavier and larger fruits than Aomeila1618. Fruit number per plant ranged from 20.4 ± 0.9 to 30.0 ± 2.0 for Aomeila1618 and ranged from 17.9 ± 0.6 to 24.1 ± 0.7 in different row spacing patterns in the two years, with significantly more fruits with T4 (row spacing was 80 cm).

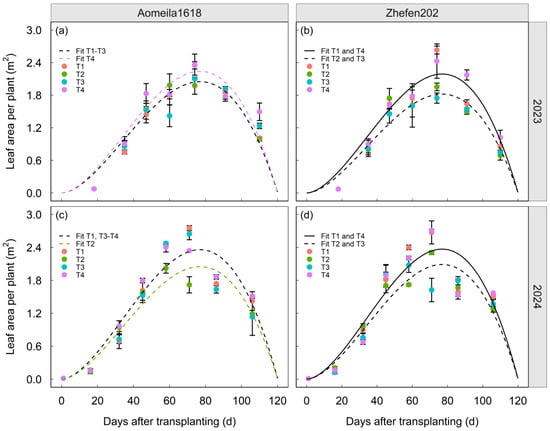

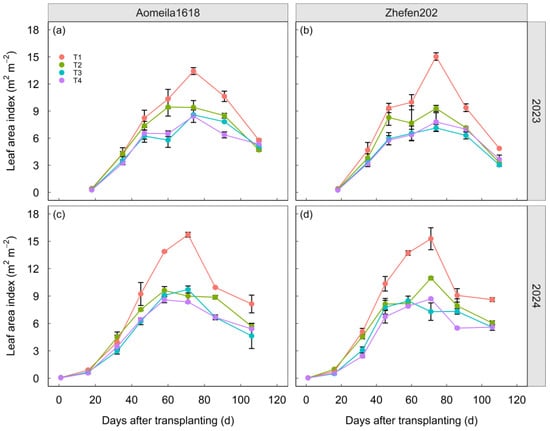

3.2. Plant Leaf Area

Tomato leaf area per plant reached the highest in the 80 cm row spacing (T4) and the lowest in the 60 cm row spacing (T2) for Aomeila1618 (Figure 4a,c). Across the two years, the maximum plant leaf area (LAm) for Aomeila1618 was 2.30 m2 with T4, which is 1.12 times to that in T2 (2.05 m2, Table 1). The plant leaf area for Zhefen202 was higher in T1 (row spacing was 50 cm) and T4 (row spacing was 80 cm) than that in T2 (row spacing was 60 cm) and T3 (row spacing was 70 cm) (Figure 4b,d). The LAm across years was 2.28 m2 for T1 and T4 and 1.96 m2 for T2 and T3 (Table 1).

Figure 4.

The tendency of leaf area per plant for greenhouse tomatoes in different row spacing patterns during 2023 and 2024 growing seasons: (a) Aomeila1618 in 2023; (b) Zhefen202 in 2023; (c) Aomeila1618 in 2024; (d) Zhefen202 in 2024. The regression data were calculated using Equation (1). Values are the means ± SE. (n = 3) The row spacing patterns are 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4).

The time taken to reach LAm (te) was 77 days after transplanting and the time taken to reach the maximum growth rate (tm) was 34 days after transplanting, which were not significantly different among the row spacings, cultivars and years (Table 1).

Row spacing affected the leaf area index in the pure strip area (Figure 5). Tomatoes in the 50 cm row spacing (T1) had the largest LAI for both cultivars and years. When taking the path into consideration, the results were similar to that in the pure strip area (Figure S1). The LAI for tomatoes in the 60 cm row spacing (T2) was slightly higher than that in T3 and T4. There was no LAI difference between T3 and T4.

Figure 5.

Leaf area index in pure strip area for greenhouse tomatoes with different row spacing patterns during 2023 and 2024 growing season: (a) Aomeila1618 in 2023; (b) Zhefen202 in 2023; (c) Aomeila1618 in 2024; (d) Zhefen202 in 2024. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). The row spacing patterns are 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4).

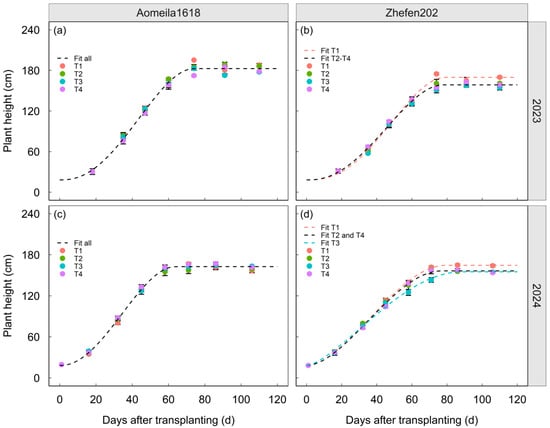

3.3. Plant Height

Plant height was not affected by row spacing for Aomeila1618 (p > 0.05) (Table 2, Figure 6a,c). The maximum plant height (a + Hm) was 182.61 ± 0.39 cm in 2023 and 162.61 ± 0.32 cm in 2024. For Aomeila1618, the duration it took to reach a + Hm (te) was 74 days after transplanting in 2023, which was 10 days later than in 2024. The time taken to reach the maximum growth rate (tm) was in 44 days after transplanting in 2023, which was also 10 days later than in 2024.

Figure 6.

The tendency of plant height for greenhouse tomatoes in different row spacing patterns during 2023 and 2024 growing seasons: (a) Aomeila1618 in 2023; (b) Zhefen202 in 2023; (c) Aomeila1618 in 2024; (d) Zhefen202 in 2024. The regression data were calculated using Equation (2). Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). The row spacing patterns are 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4).

Row spacing affected plant height for Zhefen202 in both years (Figure 6b,d) (p < 0.01). Plants in T1 (row spacing was 50 cm) had the highest height, which was 169.67 ± 1.27 cm in 2023 and 164.56 ± 1.09 cm in 2024 (Table 2). Over the years, the final plant height was 157.49 ± 0.59 cm in T2 (row spacing was 60 cm) and T4 (row spacing was 80 cm) and 156.83 ± 1.01 cm in T3 (row spacing was 70 cm). The duration it took to reach the maximum plant height (te) across the two years was 79 days after transplanting in T1, which was two days later than in T2 and T4 and four days earlier than in T3. The time taken to reach the maximum growth rate (tm) across the row spacing patterns was 46 days after transplanting in 2023, which was 12 days later than in 2024.

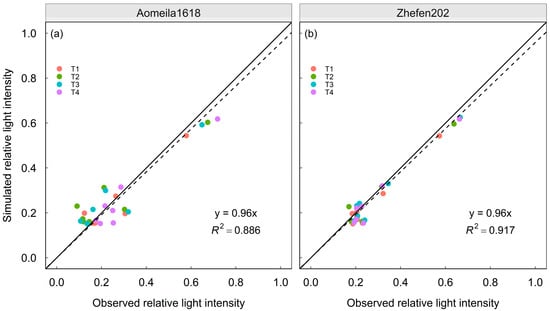

3.4. Radiation Interception

Across the row spacing treatments, simulated and observed relative light intensity for the two tomato cultivars showed good agreement (Figure 7). Overall, the intermediate model underestimated the relative light intensity slightly by 4% for both Aomeila1618 and Zhefen202.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of simulated and observed relative light intensity in different row spacing patterns during 2024 growing season: (a) Aomeila1618; (b) Zhefen202 (n = 28). The dashed line was the regression observed and simulated relative light intensity. The row spacing patterns are 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4).

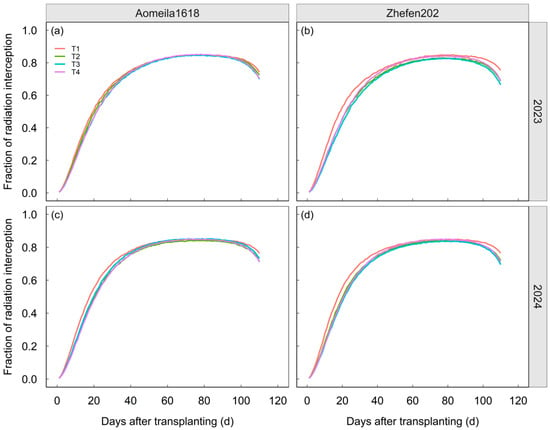

The fraction of radiation interception in response to row spacing was weaker in both years (Figure 8). The fraction of radiation interception in T1 (row spacing was 50 cm) was higher than that in the other three row spacing patterns (T2, T3 and T4), especially in the early and late growing season. The average fraction of radiation interception during the whole growing season across the years and cultivars was 0.70 for T1 and 0.67 for the other three row spacing patterns (ranging from 0.65 to 0.69).

Figure 8.

The fraction of radiation interception for greenhouse tomatoes in different row spacing patterns during 2023 and 2024 growing seasons: (a) Aomeila1618 in 2023; (b) Zhefen202 in 2023; (c) Aomeila1618 in 2024; (d) Zhefen202 in 2024. The row spacing patterns are 50 cm (T1), 60 cm (T2), 70 cm (T3) and 80 cm (T4).

The tomato plants intercepted the highest radiation at the 50 cm row spacing (T1), but lowest radiation at the 70 cm row spacing (T3), except for Aomeila1618 in 2024 (Table 4). In both years, the total radiation interception varied from 539.16 ± 0.22 MJ m−2 to 562.72 ± 0.07 MJ m−2 for Aomeila1618 and from 528.66 ± 0.12 MJ m−2 to 562.84 ± 0.11 MJ m−2 for Zhefen202. Across the years and cultivars, row spacing reduced tomato radiation interception in T2–T4 by 2.02–5.24%, compared to tomatoes in T1.

Table 4.

Aboveground dry matter, radiation interception and radiation use efficiency (RUE) of greenhouse tomatoes in 2023 and 2024.

3.5. Radiation Use Efficiency

The highest aboveground dry matter was reached in the 50 cm row spacing (T1) for both Aomeila1618 and Zhefen202, even though there was no significant difference for Aomeila1618 (Table 4). Tomato RUE showed significant differences among row spacing patterns, except for Aomeila1618. There was no significant RUE difference for Aomeila1618 in both years. However, the maximum RUE for Zhefen202 was reached in T1. There was no RUE difference for Zhefen202 in the other three row spacing patterns (T2, T3 and T4). Tomato cultivar affected the RUE (p < 0.05). Across the years, the maximum RUE was 1.94 g MJ−1 for Aomeila1618 and 2.04 g MJ−1 for Zhefen202.

4. Discussion

This study aimed at quantifying the yield, radiation interception and RUE of tomato, and relates this to row spacing effects and cultivar effects. Taking occupied land area into consideration, tomatoes in the 50 cm row spacing (T1) had a higher leaf area index, larger radiation interception and greater fruit yield than in the 60 cm, 70 cm and 80 cm row spacing patterns (T2, T3 and T4) (Table 3 and Table 4, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure S1). Due to cultivar characteristics, although Aomeila1618 had smaller aboveground dry matter and RUE advantage in the 50 cm row spacing (T4), row spacing had no effect on them (Table 4). Zhefen202 had larger aboveground dry matter and greater RUE in the 50 cm row spacing (T1) (Table 4).

In this study, we focused on row spacing with a fixed plant distance, which limits the interactive effects between plant distance and row spacing. For convenient drip irrigation and to ensure tomato vine support, the experiment did not use a completely randomized design. Even though plants in the border rows of T1 and T4 were not sampled, greenhouse border location may also influence the growth and yield formation of plants in the inner rows. If land and labor are both sufficient in the greenhouse, it is better to arrange the blocks completely randomly. Our current model does not contain the plant architecture that affects light transmission in the canopy, which slightly underestimated the relative light intensity by 4% (Figure 7). However, a previous study indicated that models without plant architecture are also adequate for calculating the radiation intercepted by strip canopies [24]. In subsequent modeling studies, it is necessary to construct a tomato FSP model with a plant architecture to predict the effects of canopy configurations and cultivars, and assess the trait plasticity response.

4.1. Yield and Growth Among Different Row Spacing Patterns

Tomatoes were cultivated in strips composed of two rows, which reduced the plant density per unit area compared to homogeneous canopies without empty paths. The fruit yield per unit area is decided by single-fruit weight × fruit number per plant × plant number per unit area (plant density). In this study, row spacing affected tomato yield, single-fruit weight and fruit number per plant (p < 0.05), regardless of year and tomato cultivar (Table 3). Suitable canopy configurations can improve canopy light interception. However, too large row spacings would cause excessive light energy loss and ultimately be detrimental to the total yield [9]. Although plant density in the whole land area decreased with the increase in row spacing, the fruit yield was not reduced in T4, compared to T3 (Table 3). This phenomenon may be attributed to the row orientation. Due to the sun rising from the east and setting in the west, plants in the north–south orientation could more strongly compete for light than in northeast–southwest orientation, leading to greater effects of row spacing to yield [7,41]. The highest fruit yield was achieved in T1 across the years and cultivars. The high plant density in T1 increased the total number of fruit-bearing plants per unit area, compensating for any potential reduction in individual plant yield [42]. Row spacing had no effect on the tomato fruit shape index, which was decided by genotype [43].

Leaf area and plant height are fundamental indicators of canopy development, which directly affect radiation interception and resource utilization. The maximum leaf area showed variations across row spacing patterns and cultivars over the two growing seasons (Table 1 and Figure 4). Tomatoes in the 50 cm (T1) and 80 cm row spacing patterns (T4) across the years and cultivars had larger leaf areas per plant than in T2 and T3. In the narrow crop strip (T1), plants’ shade avoidance response prompts tomatoes to expand their leaf area to capture limited light; however, reduced intraspecies competition in wide crop strips, allowing for more photosynthates to reach the leaves [44]. The time taken to reach the maximum LAm (te) and maximum growth rate (tm) remained constant across all treatments, suggesting that row spacing primarily affects the magnitude of LA growth rather than the time of developmental stages, which is consistent with Heuvelink’s [45] TOMSIM model simulations, predicting stable phenological time under various spacing regimes.

Due to intense intraspecific competition, plants in high densities have longer internodes, leading to higher final plant height [7]. The maximum plant height differed between cultivars but showed minimal variation across row spacing patterns for the same cultivar. Aomeila1618 maintained a consistent value of 182.61 cm in 2023 and 162.61 cm in 2024 across the row spacing patterns, while Zhefen202 showed a reduced height in T2–T4 compared to T1 in the two years (Table 2 and Figure 6). This cultivar-specific response may be attributed to genetic differences in architectural plasticity: Aomeila1618 has a more fixed growth cycle, whereas Zhefen202 often prioritizes vertical growth to compete for light. The time taken to reach the maximum growth rate (tm) also showed cultivar differences, indicating that row spacing has a weaker influence on height growth than genetic factors.

4.2. Radiation Interception and Use Efficiency Among Different Row Spacing Patterns

Radiation interception is one of the key factors affecting the photosynthetic efficiency of plants. Previous studies have shown that planting patterns, such as plant spacing, row spacing and row orientation, lead to different inter- and/or intra-row shading micro-environments, which affect light distribution during the day [7,46,47]. The effects of row spacing on radiation interception directly reflected the differences in canopy structure (Table 4 and Figure 8). In the 50 cm row spacing treatment (T1), high plant density led to earlier and more complete canopy closure, reducing light transmission to the soil surface [48,49]. In contrast, the wider row spacing in T2–T4 left gaps between canopies, leading to lower radiation interception. In this study, we used the same daily incident radiation intensity calculation method to avoid the effect of incident radiation differences between the years on the radiation interception. Therefore, although the tomatoes had larger leaf areas in 2024, the plants had shorter plant heights and an overall shorter growing season than in 2023, which led to lower radiation interception (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 4; Figure 4 and Figure 6). Comparing the plants in the early stages, when the plants were small (0–60 days after transplanting), plants were found to be higher in 2024 than in 2023; this was because the larger leaf area helped to intercept more radiation. However, after 60 days, the shorter plant height in 2024 limited radiation interception as the high leaf area was concentrated inside a small cube, which limited radiation transmission. Row spacing and orientation both lead to alterations in the internode size, leaf size, leaf inclination angle, plant height and leaf area, which are important input parameters in the FSP models [7,31,37]. Even though plant architecture increases radiation interception in strip canopies, the difference in estimated radiation interception between models with and without plant architecture is acceptable [24]. Therefore, the intermediate model can be used to simulate radiation interception in strip canopies.

Radiation use efficiency refers to the efficiency of plants converting the intercepted light energy into chemical energy through photosynthesis, which is an important indicator to measure the photosynthetic capacity of plants [50]. For different tomato cultivars, RUE showed different performances (Table 4). Narrow crop strips led to low light transmission in the canopy. Leaves in the bottom part of the canopy were unable to intercept enough radiation. However, light is one of the limiting resources in natural conditions, and plants grown under low light intensity would adapt to capture light efficiently [51]. Therefore, Zhefen202 in the 50 cm row spacing (T1) had a higher RUE than in the other three row spacing patterns (T2, T3 and T4). In this study, the effect of row spacing on the RUE for Aomeila1618 was small. The high RUE helped the tomatoes to produce more biomass. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the character of RUE when choosing tomato cultivars to achieve high yield and good quality.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we quantified the effects of row spacing on tomato growth, yield, radiation interception and radiation use efficiency in a single-span greenhouse at the cultivar level. Although there were significant differences in genotype performance between the two selected cultivars (Aomeila1618 and Zhefen202), the results showed that tomatoes in the 50 cm row spacing (T1) had a larger leaf area per unit land area, more radiation interception and ultimately higher yield than in the other three row spacing patterns (T2, T3 and T4). Row spacing did not affect tomato leaf and internode expansion time, except for the internode expansion time in Zhefen202. Despite similar dry matter and RUE for Aomeila1618, Zhefen202 in the narrow strip used light more efficiently. The row spacing effect on dry matter and RUE for Aomeila1618 was smaller than that for Zhefen202. These findings provide important insights into the role of genotype performance in relation to row configuration. It would be interesting to explore additional plant distance in future studies in relation to differences in environment, management and genotypes. Our results are able to help researchers to understand the mechanisms of intraspecific competition in the optimization of strip canopy design for sustainable agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16010006/s1, Figure S1. Leaf area index in whole land area (strip + path) for greenhouse tomatoes with different row spacing patterns during 2023 and 2024 growing seasons.

Author Contributions

S.L., data analysis, funding acquisition, creation of models, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. M.X., experiment management for water, greenhouse operation and data analysis. K.H., data collection, digitalization and writing for introduction. S.T., deep data analysis and methodology. Y.Z., writing—review and editing. C.Z., experiment design and management for diseases and insect pests. S.H., conceptualization and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32201658) and the Hangzhou Science and Technology Development Project from Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 20231203A02).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alejandro Morales for sharing the code for the intermediate model, Jochem B. Evers for modifying the code for the intermediate model and Wopke van der Werf for the idea to combine Goudriaan’s block mode and FSP model.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RUE | Radiation interception and use efficiency |

| PAR | Photosynthetically active radiation |

| LA | Leaf area |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| RI | Radiation interception |

| k | Light extinction coefficient |

| DM | Dry matter |

| FSP | Functional–structural plant |

References

- Li, J.M.; Xiang, C.Y.; Wang, X.X.; Guo, Y.M.; Huang, Z.J.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Du, Y.C. Current situation of tomato industry in China during ‘The Thirteenth Five-year Plan’ period and future prospect. Chin. Veg. 2021, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E.J.; Bowyer, C.; Tsouza, A.; Chopra, M. Tomatoes. An extensive review of the associated health impacts of tomatoes and factors that can affect their cultivation. Biology 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Yan, J.Y.; Xiang, T.X.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Gu, W.R. Contribution of fertilizer, density and row spacing practices for maize yield and efficiency enhancement in northeast China. Plants 2022, 11, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-del-Campo, M.; Connor, D.J.; Trentacoste, E.R. Long-term effect of intra-row spacing on growth and productivity of super-high density hedgerow olive orchards (cv. Arbequina). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-del-Campo, M.; Trentacoste, E.R.; Connor, D.J. Long-term effects of row spacing on radiation interception, fruit characteristics and production of hedgerow olive orchard (cv. Arbequina). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel-Muguet, S.; Beauclair, P.; Bataillé, M.-P.; Avice, J.-C.; Trouverie, J.; Etienne, P.; Ourry, A. Light restriction delays leaf senescence in winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Henke, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Wei, M. Optimized tomato production in Chinese solar greenhouses: The impact of an east-west orientation and wide row spacing. Agronomy 2024, 14, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, G.; Xie, R.; Hou, P.; Ming, B.; Xue, J.; Wang, K.; Li, S. Optimizing row spacing increased radiation use efficiency and yield of maize. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 4806–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, J. Effects of row spacing and irrigation amount on canopy light interception and photosynthetic capacity, matter accumulation and fruit quality of tomato. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2023, 56, 2141–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, A.; Wang, M.; Jahan, M.S.; Wen, Y.; Liu, X. The positive effects of increased light intensity on growth and photosynthetic performance of tomato seedlings in relation to night temperature level. Agronomy 2022, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.X.; Xu, Z.G.; Liu, X.Y.; Tang, C.M.; Wang, L.W.; Han, X.L. Effects of light intensity on the growth and leaf development of young tomato plants grown under a combination of red and blue light. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 153, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Guo, X.; Chen, X.; Zheng, L.; Kholsa, C.S. Dynamic temperature integration with temperature drop improved the response of greenhouse tomato to long photoperiod of supplemental lighting. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1170, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Carrigan, A.; Hinde, E.; Lu, N.; Xu, X.Q.; Duan, H.; Huang, G.; Mak, M.; Bellotti, B.; Chen, Z.H. Effects of light irradiance on stomatal regulation and growth of tomato. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 98, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.C.; Amâncio, S. Antioxidant defence system in plantlets transferred from in vitro to ex vitro: Effects of increasing light intensity and CO2 concentration. Plant Sci. 2002, 162, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.A.; Loomis, R.S.; Lepley, C.R. Vegetative growth of corn as affected by population density. I. Productivity in relation to interception of solar radiation1. Crop Sci. 1965, 5, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Li, T.; Gao, Y.; Li, J. Effects of different row spacing allocation on fruit classification and canopy characteristics of tomato planted in plastic greenhouse based on combination of agricultural machinery and agronomy. Acta Agric. Boreali Occident. Sin. 2020, 29, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J.; Sastri, C.V.S. PAR distribution and radiation use efficiency in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) crop canopy. J. Agrometeorol. 2003, 5, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsi, M.; Saeki, T. On the factor light in plant communities and its importance for matter production. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudriaan, J. Crop micrometeorology: A simulation study. In Simulation Monographs; PUDOC: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1977; 249p. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Han, S.; Wang, Q.; Evers, J.; Liu, J.; van der Werf, W.; Li, L. Plant density affects light interception and yield in cotton grown as companion crop in young jujube plantations. Field Crops Res. 2014, 169, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Bai, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; van der Werf, W.; Evers, J.B.; Stomph, T.J.; Guo, J.; et al. Light interception and use efficiency differ with maize plant density in maize-peanut intercropping. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oort, P.A.J.; Gou, F.; Stomph, T.J.; van der Werf, W. Effects of strip width on yields in relay-strip intercropping: A simulation study. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 112, 125936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Rahman, T.; Yang, F.; Song, C.; Yong, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, W. PAR interception and utilization in different maize and soybean intercropping patterns. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; van der Werf, W.; Gou, F.; Zhu, J.; Berghuijs, H.N.C.; Zhou, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, Y.; Evers, J.B. An evaluation of Goudriaan’s summary model for light interception in strip canopies, using functional-structural plant models. Silico Plants 2024, 6, diae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, R.; Ruan, M. ZheFen 202 and its cultivation technology. Beijing Agricul. 2003, 8, 6–7. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X84Xx1LLloKyalZPBpWKFJ2H7L5PLGVQrdUbLrRV-g71tlFAEL61l_gp4InlzTuELnxncTCPvM6zJ_TIMdeBoas-u8g6v2PPEwlOS0pKr3wzkMafdsdwrJzK2mLnh1teptKZdoTzlMNjofCtk9g9McTyCZxEf_gMyXWE8NelMeIdlQGgWW8j0A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Wang, R.; Zhou, G.; Ye, Q.; Yao, Z.; Ruan, M. Breeding of tomato variety Aomeila1618 for resistance to tomato yellow leaf curl virus disease (TYLCVD). J. Zhejiang Agr. Sci. 2020, 61, 846–847+851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xue, X. Influences of shading on plant growth and dry matter distribution of tomatoes at flowering and fruit stage. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmerling, R.; Kniemeyer, O.; Lanwert, D.; Kurth, W.; Buck-Sorlin, G. The rule-based language XL and the modelling environment GroIMP illustrated with simulated tree competition. Funct. Plant Biol. 2008, 35, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A. Dynamic Photosynthesis Under a Fluctuating Environment: A Modelling-Based Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spitters, C.J.T. Separating the diffuse and direct component of global radiation and its implications for modeling canopy photosynthesis. Part II. Calculation of canopy photosynthesis. Agr. Forest Meteorol. 1986, 38, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, J.B.; Vos, J.; Yin, X.; Romero, P.; van der Putten, P.E.L.; Struik, P.C. Simulation of wheat growth and development based on organ-level photosynthesis and assimilate allocation. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 2203–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck-Sorlin, G.; de Visser, P.H.; Henke, M.; Sarlikioti, V.; van der Heijden, G.W.; Marcelis, L.F.; Vos, J. Towards a functional–structural plant model of cut-rose: Simulation of light environment, light absorption, photosynthesis and interference with the plant structure. Ann. Bot. 2011, 108, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Yan, G. Estimation of daily diffuse solar radiation in China. Renew. Energ. 2004, 29, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlikioti, V.; de Visser, P.H.B.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Exploring the spatial distribution of light interception and photosynthesis of canopies by means of a functional-structural plant model. Ann. Bot. 2011, 107, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Goudriaan, J.; Lantinga, E.A.; Vos, J.; Spiertz, J.H.J. A flexible sigmoid function of determinate growth. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; van der Werf, W.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, Y.; Evers, J.B. Estimating the contribution of plant traits to light partitioning in simultaneous maize/soybean intercropping. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 3630–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Evers, J.B.; van der Werf, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, Y. Estimating the differences of light capture between rows based on functional-structural plant model in simultaneous maize-soybean strip intercropping. Smart Agric. 2022, 4, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B.M. Ecological Models and Data in R; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhong, P.; Li, S.; Ma, Y. Quantification of row orientation effects on radiation distribution in maize-soybean intercropping based on functional-structural plant model. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 1882–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, K.; Makino, R.; Akihiro, T.; Nishijima, T. Planting density influence yield, plant morphology and physiological characteristics of determinate ‘Suzukoma’ Tomato. J. Applied Hortic. 2018, 20, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Abriham, A.; Kefale, D. Effect of intra-row spacing on plant growth, yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum mill) varieties at mizan-aman southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Agric. Ext. 2020, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, A.J.; Chapin, F.S.; Mooney, H.A. Resource limitation in plants—An economic analogy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1985, 16, 363–392. [Google Scholar]

- Heuvelink, E. TOMSIM: A dynamic simulation model for tomato crop growth and development. In ISHS Second International Symposium on Models for Plant Growth, Environment Control and Farm Management in Protected Cultivation, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1997; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS): Leuven, Belgium, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer, M.; de Visser, P.H.B.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Row orientation affects the uniformity of light absorption, but hardly affects crop photosynthesis in hedgerow tomato crops. Iilico Plants 2021, 3, diab025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentacoste, E.R.; Gómez-del-Campo, M.; Rapoport, H.F. Olive fruit growth, tissue development and composition as affected by irradiance received in different hedgerow positions and orientations. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 198, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenijevic, N.; DeWerff, R.; Conley, S.; Ruark, M.; Werle, R. Influence of integrated agronomic and weed management practices on soybean canopy development and yield. Weed Technol. 2022, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cui, J.; Tian, L.; Guo, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.; Zhang, N.; Ali, S.; et al. Reducing irrigation and increasing plant density enhance both light interception and light use efficiency in cotton under film drip irrigation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George-Jaeggli, B.; Jordan, D.R.; van Oosterom, E.J.; Broad, I.J.; Hammer, G.L. Sorghum dwarfing genes can affect radiation capture and radiation use efficiency. Field Crops Res. 2013, 149, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Graham, R. Leaf optical properties of rainforest sun and extreme shade plants. Am. J. Bot. 1986, 73, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.