Abstract

Greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural crops remain a critical challenge for climate change mitigation. This review synthesizes evidence on cropland management interventions and global N2O mitigation potential. Agricultural practices such as cover cropping, agroforestry, reduced tillage, and diversification show promise in reducing CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions, yet uncertainties in measurement, verification, and socio-economic adoption persist. This review highlights that biochar application reduces N2O emissions by 16.2% (95% CI: 9.8–22.6%) in temperate systems, demonstrating greater consistency compared to no-till agriculture, which shows higher variability (11% reduction, 95% CI: −19% to +1%). Legume-based crop rotations reduce N2O emissions by up to 39% through improved nitrogen efficiency and increase soil organic carbon by up to 18%. However, reductions in synthetic fertilizer use (65% lower in legume vs. cereal systems) can be offset by the effects of biological nitrogen fixation. Optimized nitrogen fertilization, when combined with enhanced-efficiency fertilizers, can reduce N2O emissions by 55–64%. Complementing this, global-scale analysis underscores the dominant role of optimized nitrogen fertilization in curbing N2O emissions while sustaining yields. To bridge gaps between practice-level interventions and global emission dynamics, this paper introduces the ICEMF, a novel approach combining field-based management strategies with spatially explicit emission modeling. Realistic implementation currently achieves 25–35% of technical potential, but bundled interventions combining financial incentives, training, and institutional support can increase adoption to 40–60%, demonstrating ICEMF’s value through integrated, context-adapted approaches. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English between 1997 and 2025 were selected to ensure recent and reliable findings. This review highlights knowledge gaps, evaluates policy and technical trade-offs, and proposes ICEMF as a pathway toward scalable and adaptive mitigation strategies in agriculture.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is widely recognized as a major contributor to anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHG), emitting carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) through soil degradation, livestock-related processes, and intensive crop management [1]. Recent global assessments indicate that agricultural emissions have continued to rise, with food systems responsible for approximately one-third (34%) of total anthropogenic GHG emissions and agricultural emissions increasing by 9.3% between 2000 and 2018, driven primarily by synthetic fertilizer use and livestock expansion in developing regions [1,2]. The agricultural sector now accounts for 10–14% of direct anthropogenic GHG emissions globally, with significant regional disparities. Emissions in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have doubled since 1990, while developed nations show modest declines [2]. These emissions account for a substantial share of global warming, with croplands serving both as significant sources and potential sinks of GHG through soil carbon sequestration and improved land management [2]. The need to mitigate these emissions has grown increasingly urgent, as agriculture faces mounting pressures from climate change, food security concerns, and sustainability goals [3,4]. Emerging evidence from 2024 to 2025 emphasizes that agricultural systems must simultaneously achieve emission reductions, climate adaptation, and enhanced productivity, a “triple challenge” requiring integrated strategies that move beyond single-objective interventions [3,5].

Various agronomic interventions have been identified to reduce emissions, including cover cropping, reduced tillage, crop diversification, agroforestry, and organic amendments [6,7]. These practices enhance soil organic carbon stocks, reduce erosion, and improve resilience to extreme weather events [8]. Recent meta-analyses from 2022 to 2025 have refined the understanding of practice-specific mitigation potentials with greater precision. Meta-analysis of 119 paired observations from 18 studies demonstrated that biochar application consistently reduced N2O emissions by 16.2% (95% CI: 9.8–22.6%) in temperate agricultural systems, with moderate-to-high heterogeneity (I2 = 72%) and no evidence of publication bias (Egger’s test, p = 0.18) [9]. Effectiveness was maintained over 4–6 years in long-term trials [10], with greater reductions in acidic soils (pH < 6.5) due to the liming effect [9]. However, effectiveness was lower in tropical systems (8–12% reduction) where validation data remain limited [11]. This demonstrates superior consistency compared to no-till agriculture, which shows high variability (meta-analysis of 212 observations from 40 studies: mean −11%, 95% CI: −19% to −1%; I2 = 89%) with effects ranging from 19% reductions to 70% increases depending on soil texture, climate, and moisture regime [12].

Legume-based crop rotations reduce N2O emissions by up to 39% through improved nitrogen efficiency while increasing soil organic carbon by 18% compared to monoculture systems. However, the net benefits of such interventions are context-dependent, often influenced by soil type, climate, and farming system design [13]. Emerging integrated practices, such as recoupled crop–livestock systems, demonstrate potential for over 40% emission reductions when properly designed, though adoption barriers remain substantial [14]. In addition, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks face methodological inconsistencies that limit the reliability of estimates. Recent assessments from 2025 highlight that measurement uncertainties of ±30–50% in field-based emission factors and inconsistent life cycle assessment boundaries (creating 2–5-fold variations in reported emissions for identical crops) continue to undermine verification systems essential for carbon credit markets and climate policy implementation [15].

Nitrous oxide emissions are of particular concern because of their high global warming potential (GWP) (265 times that of CO2 over 100 years) and direct link to nitrogen fertilizer application [16]. Global analyses indicate that N2O emissions from croplands have quadrupled over the last six decades, with hotspots in Asia and intensive horticultural systems [17]. Strategies such as the “4R” nutrient stewardship (right source, rate, time, and placement) and precision irrigation have been highlighted as effective measures to reduce N2O by 55–64% when combined with enhanced-efficiency fertilizers (EEFs) while sustaining yields [3,18]. Crop-specific assessments show maize, rice, wheat, and vegetable systems to be the most significant contributors and therefore prime targets for mitigation [19].

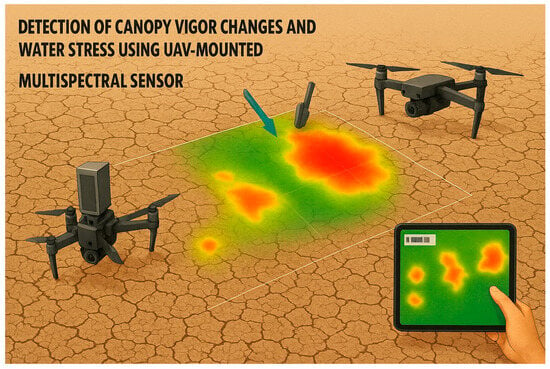

The integration of digital technologies with nutrient management has emerged as a transformative approach since 2022, marking a shift toward “agriculture 4.0” paradigms. Artificial intelligence-driven decision support systems now enable real-time optimization of fertilizer application, with demonstrated N2O reductions of 20–30% compared to conventional practices in field trials across South Asia and East Africa [20]. Remote sensing combined with machine learning models allows spatially explicit identification of emission hotspots at field-to-regional scales, enabling targeted interventions that account for within-field heterogeneity in soil properties and crop nitrogen demand [21]. Internet of Things (IoT) sensors integrated with precision irrigation systems further optimize water–nitrogen interactions, reducing both CH4 emissions in rice systems and N2O emissions in upland crops [22]. However, adoption of these digital technologies remains below 15% in smallholder systems due to high upfront costs (USD 15,000–50,000 per farm for equipment) and limited digital literacy [20].

Despite promising technical potentials, adoption of mitigation strategies remains constrained by persistent socio-economic realities, with realistic implementation limited to 25–35% of technical potential across diverse farming systems [23]. Recent surveys from 2023 to 2024 reveal that capital constraints affect 65–80% of smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, preventing investment in proven practices such as biochar application (USD 200–400 ha−1 initial cost with 5–7-year payback periods) despite documented emission reductions [23]. Barriers include land tenure insecurity (affecting 60% of farmers in sub-Saharan Africa), lack of capital, risk perception, and compatibility with traditional practices [24].

Gender disparities compound these barriers significantly, as women farmers control 43% of agricultural labor in developing regions but access only 10–20% of agricultural extension services and 5–15% of agricultural credit, reducing adoption rates of climate-smart practices by 20–35% in female-headed households [25]. Inadequate extension service ratios (1 agent per 1000–2000 farmers in many developing regions) further limit knowledge diffusion and technical support for practice adoption [24].

Policy frameworks, incentive structures, and market-based mechanisms, such as carbon credits, influence adoption rates but bring additional challenges of equity and verification [26]. As a result, biophysical estimates often overstate mitigation potential without accounting for the socio-economic conditions of real farming systems [27]. Emerging evidence from 2024 indicates that bundled interventions combining financial incentives (subsidies, low-interest credit), training programs, secure land rights, and gender-responsive extension services can increase adoption rates by 40–60% compared to single-factor approaches, suggesting that integrated socio-economic support is essential for scaling mitigation practices [28].

The climate-smart agriculture (CSA) paradigm has evolved significantly since 2022, with increased emphasis on integrated, context-specific solutions that address mitigation, adaptation, and productivity simultaneously. Recent frameworks prioritize regenerative practices, including regenerative agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and integrated crop–livestock systems, that enhance soil health, biodiversity, and farmer resilience while reducing emissions [6]. However, implementation challenges persist at scale. A 2024 global assessment found that CSA adoption varies varying substantially across regions (from 5% in some sub-Saharan African countries to over 50% in parts of Europe and North America) due to policy mismatches between national climate strategies and local agricultural realities. Notably, majority of surveyed farmers across Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia were unaware of national climate-smart agricultural policies, despite their proven effectiveness, highlighting a disconnect between policy design and implementation at the farmer level [29].

Market-based mechanisms, particularly carbon trading schemes, have gained prominence in 2023–2024 as tools to incentivize agricultural GHG mitigation. Recent analyses demonstrate that carbon credit systems can reduce agricultural emissions through innovation in low-carbon technologies, renewable energy adoption, and ecosystem restoration, with documented transaction volumes increasing by 45% annually in voluntary agricultural carbon markets [30]. However, equity concerns persist regarding smallholder participation, as transaction costs for (MRV) average USD 50–150 ha−1, often exceeding the carbon revenue potential (USD 20–80 ha−1 year−1) for small-scale farmers, effectively excluding them from market benefits [15,30]. The integrity of carbon accounting frameworks remains contested, with 2025 studies highlighting that methodological inconsistencies and measurement uncertainties undermine credibility and risk creating “carbon greenwashing” rather than genuine emission reductions [15].

Emerging paradigms in 2024–2025 emphasize system-level integration and circular economy principles in agriculture. Recoupled crop–livestock systems, for instance, demonstrate potential for over 40% emission reductions in China through optimized nutrient cycling, manure valorization, and reduced reliance on synthetic inputs [14]. Similarly, regenerative agroforestry approaches combining carbon sequestration (74–320 Mg C ha−1 depending on system age) with biodiversity conservation and climate-resilient landscapes show promise, though adoption timelines span 10–15 years before full benefits materialize [31]. These integrated approaches align with recent calls for “agriculture 4.0” that leverages digital technologies to optimize both productivity and environmental outcomes, representing a paradigm shift from single-practice interventions to holistic farm system redesign [22].

To address these complexities, this review introduces the ICEMF, a novel synthesis approach that couples practice-level evidence with spatially explicit modeling of N2O and Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) outcomes. The framework integrates empirical data, regional modeling, and socio-economic adoption pathways, offering a decision-support tool for scalable interventions [32]. By combining technological, agronomic, and policy perspectives, ICEMF provides a roadmap for reducing agricultural GHG while maintaining productivity [33,34,35].

1.1. Global Imperatives and the Need for Integrated Frameworks

1.1.1. The Urgency of Agricultural Climate Action

The need for transformative agricultural GHG mitigation has never been more urgent. Climate change is already reducing global crop yields, with temperature increases projected to decrease wheat yields by 6.0% and maize by 7.4% per degree Celsius without CO2 fertilization, effective adaptation, and genetic improvement [36,37]. Simultaneously, agricultural systems must feed 9.8 billion people by 2050, requiring a 50–70% increase in food production from 2010 levels, while reducing absolute GHG emissions [38,39]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that limiting warming to 1.5 °C requires agricultural emission reductions of approximately 1 gigaton CO2-equivalent per year by 2030, with agriculture potentially contributing 3.9–4.0 gigatons of annual emission reductions by 2050 through technical mitigation and dietary changes [40,41].

Yet, current trajectories are moving in the opposite direction. Food systems contributed 34% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2015, totaling 18 gigatons of CO2-equivalent per year [2]. Total food system emissions reached approximately 16 gigatons CO2eq in 2018, representing one-third of global anthropogenic emissions, with an 8% increase since 1990 [42]. While emissions from land-use change have declined by 29% since 2000, farm-gate agricultural emissions increased by 13% over the same period, and pre- and post-production emissions grew by 45%. Regional disparities are striking: between 2000 and 2020, agrifood system emissions increased by 35% in Africa and 20% in Asia, driven by expanding livestock production and intensified fertilizer use [43,44]. Without transformative interventions across production systems, demand management, and supply chains, agricultural emissions are projected to reach 15 gigatons CO2eq by 2050, fundamentally undermining Paris Agreement goals and requiring closure of an 11-gigaton mitigation gap [45].

1.1.2. The Food Security–Climate Mitigation Nexus

The imperative of food security compounds the challenge. Global food insecurity affects populations overwhelmingly concentrated in regions where agriculture is both the primary livelihood and most vulnerable to climate change [46,47]. Smallholder farmers, who produce 35% of the world’s food on farms smaller than 2 hectares, face simultaneous pressures from climate adaptation (increased droughts, floods, and pests) and mitigation expectations, while lacking access to essential resources [48,49]. These farmers are particularly vulnerable to climate impacts that threaten both their production capacity and livelihoods [50].

This creates a critical equity dimension: the populations least responsible for historical emissions (smallholder farmers in developing nations) are most vulnerable to climate impacts and face the most significant barriers to adopting mitigation practices. Systemic constraints limit their capacity to respond: 65–80% lack access to formal credit necessary for investing in climate-smart technologies [51], 60% face insecure land tenure that discourages long-term soil improvement investments [52], and extension service ratios of 1 agent per 1000–2000 farmers in many regions severely restrict knowledge transfer and technical support [53]. Gender disparities compound these barriers significantly, as women farmers control 43% of agricultural labor in developing regions but access only 10–20% of agricultural extension services and 5–15% of agricultural credit, reducing adoption rates of climate-smart practices by 20–35% in female-headed households [54,55]. Any viable framework must therefore address not only technical emission reduction potential but also the socio-economic justice dimensions of enabling equitable participation in climate solutions while ensuring food security and livelihoods.

1.1.3. Why Existing Frameworks Are Insufficient for Agricultural GHG Mitigation and Climate Adaptation

Current frameworks for agricultural GHG mitigation operate in silos, addressing either technical potential or policy implementation, but rarely integrating both with socio-economic realities:

Technical frameworks (e.g., 4R nutrient stewardship, conservation agriculture protocols) provide scientifically validated practices but lack mechanisms to scale adoption. The 4R framework, despite demonstrating 55–64% N2O reductions in field trials, achieves limited adoption globally after 20 years of promotion, with studies documenting low adaptation despite effectiveness in key agricultural regions, revealing fundamental disconnects between technical recommendations and farmer realities [18,56,57]. No-till agriculture shows similarly low uptake, approximately 12–25% of cropland globally, despite proven soil carbon benefits, because recommendations fail to account for region-specific challenges such as soil compaction in tropical systems, herbicide costs, and incompatibility with smallholder crop–livestock integration [58,59].

Policy frameworks (e.g., climate-smart agriculture, low-emission development strategies) set ambitious national targets but struggle with implementation. A 2025 assessment found that approximately 70% of farmers in Kenya with comprehensive CSA policies were unaware these policies existed, highlighting a fundamental disconnect between policy design and farmer-level action [29]. Moreover, these frameworks rarely specify how national emission reduction targets translate to farm-level practices across heterogeneous landscapes, with implementation varying substantially across regions due to weak scaling mechanisms and insufficient attention to context-specific barriers [60,61].

Modeling frameworks (e.g., Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), life cycle assessments) operate at scales mismatched to farmer decision-making. IAMs aggregate agricultural systems into large regions (e.g., “sub-Saharan Africa”), obscuring substantial within-region variation in soil types, rainfall patterns, farmer resources, and market access that determine whether a mitigation practice succeeds or fails [62,63]. These models inadequately capture the behavioral, institutional, and socio-economic factors that govern farmer technology adoption, limiting their utility for designing implementable interventions. Life cycle assessments provide detailed emission accounting but suffer from methodological inconsistencies; emission estimates for identical crops can vary two- to five-fold depending on unreported differences in system boundaries, allocation methods, and regional assumptions [64,65].

Carbon market mechanisms promise to incentivize adoption through payments for verified emission reductions but face critical credibility gaps. Measurement uncertainties of ±30–50% in field-based emission factors undermine the integrity of carbon accounting systems [15], while standardized MRV protocols remain absent or inadequate for the majority of agricultural interventions [66,67]. High transaction costs for MRV activities often exceed potential carbon revenue for smallholder farmers, effectively excluding them from market benefits and raising concerns about equity and genuine versus “greenwashed” mitigation [68,69,70].

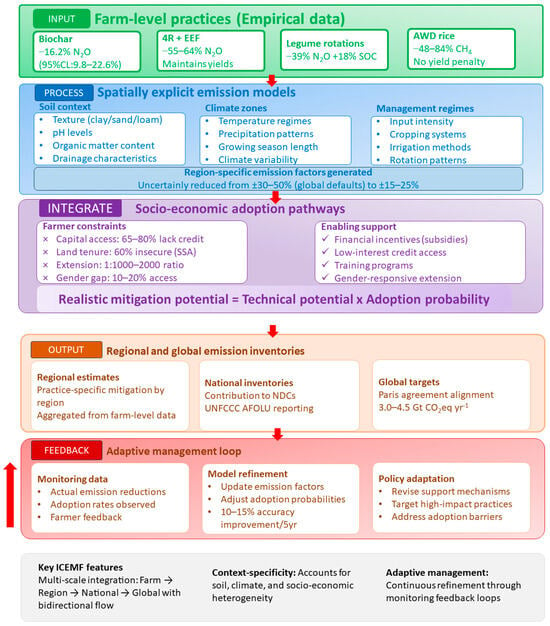

In summary, ICEMF is essential because it provides the integrated, scalable, and equitable methodology that agriculture urgently requires to simultaneously address climate mitigation, food security, and farmer resilience in the critical decade ahead. Without such integration, agricultural systems risk continuing trajectories that exacerbate rather than solve the interconnected crises of climate change and food insecurity. The framework directly responds to recent calls from global policy processes including the UN Food Systems Summit’s emphasis on integrated transformation [71], the IPCC AR6’s identification of agriculture as a “critical near-term opportunity” constrained by implementation gaps [72], and the Paris Agreement Global Stocktake’s revelation that most national climate commitments lack specific, verifiable agricultural emission reduction pathways [73,74] (Figure 1). The novel contributions of this study are as follows:

- Proposes the ICEMF as a hybrid approach that unites field-level management practices with global-scale emission modeling.

- Provides a dual synthesis of practice-based interventions and spatially explicit N2O mitigation assessments, highlighting synergies often overlooked in single-focus reviews.

- Identifies critical policy–practice trade-offs and socio-economic adoption barriers, offering a roadmap for aligning climate targets with farmer-centric solutions.

Figure 1.

ICEMF data flow and feedback mechanisms. The framework integrates five operational layers: (1) INPUT—farm-level practices provide empirical emission data with quantified reduction potentials; (2) PROCESS—spatially explicit models account for soil, climate, and management contexts, reducing uncertainty from ±30–50% to ±15–25%; (3) INTEGRATE—socio-economic adoption pathways adjust technical potential by realistic adoption probabilities (baseline 5–25%, improving to 40–60% with bundled support); (4) OUTPUT-regional estimates aggregate to national inventories (NDCs) and global targets (3.0–4.5 Gt CO2eq yr−1); (5) FEEDBACK—monitoring data enables continuous refinement of emission factors and policy mechanisms, improving accuracy by 10–15% over 5 years. Downward information flow (green → blue → purple → orange) translates carbon budgets to farm-level guidance; upward feedback loop (red) continuously improves framework performance through observed field data.

1.2. Review Context and Objectives

The literature on GHG emissions in agriculture highlights both the scale of the problem and the diverse mitigation strategies proposed to balance productivity with sustainability. Table 1 shows summary of research gaps. Ullah, Farooque [75] reviewed biochar production processes and demonstrated its potential to reduce soil-based GHG emissions by enhancing carbon storage, soil quality, and microbial activity. Zhu and Miller [76] found that tomato production systems vary widely in emissions, highlighting precision agriculture and low-carbon energy as key interventions. Ref. [77] applied a harmonized methodology to soybean production studies, finding significant variability in GHG emissions driven by fertilizer use, irrigation, and regional differences. Yuan, Lian [78] examined GHG emissions from constructed wetlands, emphasizing the role of planting strategies and management practices in reducing secondary pollution. Kabato, Getnet [3] assessed climate-smart agriculture strategies, underscoring the benefits of integrated practices like biochar application, agroforestry, and regenerative agriculture for soil health and emission mitigation. Ref. [79] synthesized evidence on converting cropland to grassland in peat soils, concluding that effects on CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions remain ambiguous and context-dependent. Kukah, Jin [30] reviewed the role of carbon trading, finding that it reduces GHG emissions through innovations in low-carbon technologies, renewable energy, and ecosystem restoration. The study demonstrated that recoupled crop–livestock systems in China could reduce agricultural GHG emissions by over 40%, highlighting their potential for sustainable intensification [14].

Table 1.

Summarizes the main research gaps.

Agricultural crop systems are central to global food security but simultaneously represent a major source of GHG emissions, particularly CO2, CH4, and N2O. Despite extensive research on individual mitigation practices, the sector continues to face significant challenges in balancing productivity with climate goals. Measurement uncertainties, limited socio-economic adoption of climate-smart practices, and policy–practice mismatches hinder the scalability of effective solutions. Moreover, most existing approaches focus narrowly on either technical interventions or emission inventories, leaving a gap in integrated frameworks that connect farm-level practices with regional and global mitigation outcomes. This disconnect underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive synthesis that not only reviews emission sources and mitigation strategies but also provides a structured pathway for practical, verifiable, and context-specific solutions to reduce agricultural GHG emissions.

Across the reviewed studies, several recurring gaps emerge. Many mitigation strategies such as biochar application, climate-smart agriculture, and crop–livestock integration show strong potential yet lack long-term field validation and region-specific performance data. Methodological inconsistencies in life cycle assessments of crops like tomatoes and soybeans limit comparability, highlighting the need for standardized boundaries and harmonized reporting. Ecosystem-based solutions such as constructed wetlands and land-use shifts provide valuable insights, but their GHG outcomes remain context-dependent and uncertain, requiring more robust monitoring frameworks. Socio-economic and policy barriers, including adoption constraints, insufficient incentives, and integration challenges with existing farming systems, are also insufficiently addressed, limiting scalability. Addressing these gaps through interdisciplinary, multi-scalar studies will be critical to designing effective, verifiable, and farmer-centered GHG mitigation strategies in agriculture.

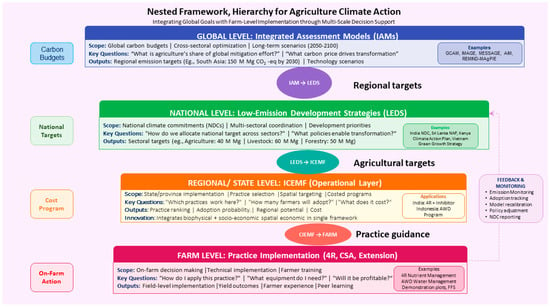

ICEMF is a conceptual framework proposed in this review to address critical gaps in existing agricultural GHG mitigation approaches. Unlike the 4R nutrient stewardship framework, which provides agronomic guidance without scaling mechanisms [18,80], Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA), which sets national targets without farm-level implementation pathways [81,82], or (IAMs), which aggregate agriculture at regional scales that obscure local heterogeneity [62,63], ICEMF operates at the critical “middle layer” between national policy and farm practice (Figure 2), addressing what [83] identified as the fundamental challenge of cross-scale governance: linking local actions to global outcomes while maintaining context specificity.

Figure 2.

ICEMF nested hierarchy for agricultural climate action. The framework operates through four complementary layers: (1) global level—IAMs allocate carbon budgets; (2) national level—LEDS translate targets into sectoral commitments; (3) regional/state level—ICEMF (highlighted) operationalizes targets through practice selection, adoption modeling, and costed programs; (4) farm level—4R and CSA practices enable implementation. Downward information flow (blue/green/orange arrows) delivers carbon budgets to farm guidance; upward monitoring data (purple dashed arrow) enables adaptive management. ICEMF occupies the critical operational middle layer, bridging aspirational national targets with implementable farm programs.

(1) Spatially explicit emission modeling with practice-level integration: ICEMF connects field-validated effectiveness data (e.g., biochar reduces N2O by 16.2% in temperate systems [9] but 8–12% in tropical systems [11]) with spatially explicit models that account for soil texture, climate zone, moisture regime, and management intensity. This enables context-specific emission predictions rather than applying universal effect sizes. For example, no-till agriculture exhibits a variability of −19% to +70% in N2O responses, depending on soil–climate conditions [12]; ICEMF’s spatial modeling captures this heterogeneity to guide where practices will succeed versus fail. ICEMF’s spatially explicit modeling approach recognizes that agricultural land use outcomes are fundamentally determined by spatial context [84], requiring models that account for local soil–climate management interactions rather than applying universal coefficients

(2) Socio-economic adoption pathway integration: ICEMF incorporates adoption probability functions based on empirical farmer typologies. Systematic review of 35 years of adoption literature [85] demonstrates that adoption is influenced by multidimensional factors beyond economic calculations, including risk perception, information access, social networks, and institutional support. Technical potential (e.g., precision fertilization: −55–64% N2O [18]) is adjusted by adoption factors including capital access (affecting 65–80% of smallholders [23]), land tenure security (60% in sub-Saharan Africa [24]), extension service ratios (1:1000–2000 in many regions [53]), and gender disparities (women access only 10–20% of extension services [25]). This translates technical potential to realistic scenarios: 25–35% implementation without support, increasing to 40–60% with bundled interventions [28]. No existing framework quantitatively links biophysical effectiveness with adoption probability at operational scales.

Together, these contributions enable ICEMF to answer the following question: “If we implement practice X in region Y with farmer support level Z, what emission reduction will actually occur and contribute to national/global targets?” This operational specificity distinguishes ICEMF from conceptual frameworks (CSA), agronomic guidelines (4R), or macro-scale models (IAMs). The novel objectives of this study are as follows:

- To systematically review GHG emissions from agricultural crop systems and evaluate the effectiveness of diverse management practices.

- To assess the global mitigation potential of N2O emissions through optimized nitrogen fertilization and complementary agronomic interventions.

- To develop and propose the ICEMF framework as a novel, scalable strategy for integrating technical, environmental, and socio-economic dimensions of GHG mitigation in agriculture.

1.3. Evaluating the Limitations of Current Agricultural GHG Mitigation Frameworks and the Potential of ICEMF to Bridge the Gaps

While the ICEMF offers a novel approach to bridging field-based practices with global emission reduction targets, several existing frameworks share similar goals of mitigating GHG emissions in agriculture. However, these frameworks often face significant challenges related to adoption, scalability, and integration of socio-economic factors. Below, we discuss a few of these frameworks and explain how ICEMF is positioned to overcome their limitations.

1.3.1. The 4R Nutrient Stewardship

The 4R nutrient stewardship framework: Right source at right rate, right time, and right place has been widely adopted globally as a science-based approach to optimize nitrogen fertilizer use [80], with documented potential to reduce N2O emissions by 55–64% when combined with EEF and improve nitrogen recovery efficiency [18,86]. While effective in many commercial farming contexts, the 4R framework faces significant challenges in context-specific adoption, as implementation is highly site-specific and regional challenges vary considerably across continents and farming systems [3,87]. The application of precision fertilization techniques aligned with 4R principles is often limited by technology access and knowledge gaps, especially in smallholder farming systems where farmers face barriers including limited resources, training, and financial support [88]. These constraints are particularly acute in sub-Saharan Africa, where low digital literacy, high equipment costs, and weak extension services impede implementation [89]. Additionally, the benefits of nutrient use efficiency optimization can be inconsistent across different soil types and climatic conditions, as regional environmental factors often equal or exceed the effects of specific fertilizer management practices on N2O emissions and nutrient losses [86]. Soil emissions occur in spatially and temporally variable “hot spots” and “hot moments,” driven by complex interactions among soil properties, weather, and microbial processes, making outcomes difficult to predict and generalize across regions [90,91]. ICEMF integrates spatially explicit emission models and considers socio-economic adoption pathways, ensuring that practices like precision fertilization are scalable and adaptable to local conditions. ICEMF’s inclusion of farmer decision-making factors, including financial incentives and training programs, helps overcome adoption barriers seen in the 4R framework.

1.3.2. Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA)

CSA aims to integrate climate adaptation, mitigation, and food security in a single framework [81,82]. While CSA has promoted practices such as agroforestry, crop diversification, and conservation tillage [60,92], it often lacks a clear mechanism for scaling these practices across diverse agricultural systems [93]. The climate-smart village approach has attempted to provide an integrative strategy for scaling adaptation options, yet implementation remains challenging across heterogeneous farming contexts [93]. Moreover, CSA’s emphasis on climate resilience sometimes overlooks the socio-economic conditions that influence farmers’ willingness to adopt these practices [94,95]. Recent evidence demonstrates that adoption barriers extend beyond technical feasibility to include economic constraints, limited extension access, and institutional factors [96,97]. Studies across West Africa reveal that while farmers recognize benefits of CSA practices, barriers such as high initial investment costs, lack of credit access, insufficient labor, and inadequate knowledge significantly impede widespread adoption [98]. Similarly, research from southern Ethiopia and European food supply chains confirms that socio-economic factors including household wealth, market access, cooperative membership, and policy support critically determine technology adoption and farm sustainability outcomes [99,100]. The gap between indigenous knowledge systems and Western scientific approaches further complicates effective adaptation strategies, suggesting that CSA frameworks must better integrate local contexts and traditional practices to achieve meaningful impact [101]. ICEMF provides a more integrated approach by combining technical practices with spatially explicit emission modeling and socio-economic adoption data. This makes ICEMF more actionable at the farm level, particularly in addressing barriers to farmer adoption and economic feasibility in low-resource regions.

1.3.3. Low-Emission Development Strategies (LEDS)

LEDS are national frameworks integrating climate mitigation with development planning across sectors, including agriculture [102]. While valuable for macro-level policy coordination, LEDS face substantial implementation challenges in agriculture. Critical gaps exist between policy objectives and farm-level realities, particularly regarding the technical feasibility and economic viability of mitigation strategies for smallholder systems [28,103]. Research in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrates that, despite progressive CSA policies, adoption remains constrained by limited access to technology, inadequate extension services, insufficient financial resources, and weak institutional capacity [29,104]. Agricultural mitigation policies face socio-political barriers including competing priorities around food security and affordability, organized lobby pressures, and redistributive effects [103]. Studies across Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Rwanda reveal persistent challenges in operationalizing LEDS locally due to trade-offs between agricultural expansion and environmental goals, donor dependence, and insufficient integration of local knowledge [104]. The effectiveness of agricultural LEDS is fundamentally constrained by disconnects between national goals and farm-level adoption realities, with conventional top-down systems inadequate for promoting equitable access to climate-smart practices [28,29]. ICEMF fills the gap by integrating farm-level interventions with regional and global emission models, offering a scalable and adaptive solution that bridges the gap between national policies and local agricultural practices. Its focus on farmer-centered solutions and policy incentives ensures that emission reduction strategies are both practical and achievable.

1.3.4. Integrated Assessment Models

IAMs are global frameworks that integrate economic, energy, land-use, agricultural, and climate systems to evaluate the impacts of climate policies on agricultural emissions [63,105]. While valuable for global policy analysis and identifying cost-effective mitigation pathways [106], IAMs face substantial limitations for real-world agricultural implementation. Critical gaps exist in capturing local specificities essential for farm-level adoption, as these models rely on highly aggregated regional representations that obscure within-region heterogeneity of farming systems, soil conditions, and farmer capacities [107,108]. IAMs have been criticized for problematic assumptions that underestimate transformation urgency and inadequately incorporate behavioral, institutional, and socio-political barriers to technology adoption [109]. Specifically, IAMs represent agricultural mitigation through technology diffusion functions assuming rational economic optimization, without adequately capturing complex socio-economic factors driving farmer decisions, including risk aversion, cultural compatibility, perceived usefulness, financial constraints, extension service access, and social network influences [110,111,112]. Research demonstrates that farmer technology adoption depends on multidimensional factors beyond economic calculations, with psychological dimensions (environmental values, innovation aversion), socio-demographics (age, education, farm size), resource endowments (land, labor, capital), and institutional contexts (extension services, policy incentives) all playing critical yet under-represented roles in IAM frameworks [113,114]. Consequently, while IAMs provide important macro-scale strategic insights, their agricultural projections lack the granularity and behavioral realism needed for context-specific implementation, necessitating complementary bottom-up approaches explicitly incorporating farmer heterogeneity and socio-institutional adoption determinants [108,113]. ICEMF offers a more granular approach by integrating field-level practices with global emission models. Unlike IAMs, ICEMF accounts for regional variations in soil types, climate, and farming systems, making it more relevant for on-the-ground implementation. Furthermore, ICEMF’s inclusion of socio-economic adoption pathways ensures that mitigation strategies are not only technically feasible but also economically viable for farmers.

Unlike existing frameworks that operate primarily at either field-level (4R, CSA) or macro-scale (LEDS, IAMs), ICEMF uniquely bridges these scales through three interconnected components: (1) empirical data integration from diverse field practices, (2) spatially explicit emission modeling that captures regional heterogeneity, and (3) socio-economic adoption pathways that ensure practical scalability. This multi-scalar integration enables ICEMF to translate local agricultural interventions into quantifiable contributions toward global emission reduction targets (Supplementary Table S1).

1.4. The Integrated Crop Emission Mitigation Framework

To address the complexities of bridging field-level practices with global emission targets while accounting for socio-economic realities, this review introduces ICEMF as a novel synthesis framework that operationalizes multi-scale agricultural GHG mitigation.

Framework architecture: ICEMF operates through four hierarchical layers (Figure 2): (1) global level—Integrated Assessment Models allocate carbon budgets across regions and sectors; (2) national level—low-emission development strategies translate global targets into sectoral commitments; (3) regional/state level—ICEMF occupies this critical operational layer, bridging national targets with farm implementation through practice selection, adoption modeling, and costed programs; (4) farm level—specific practices (4R nutrient stewardship, CSA practices) enable on-ground implementation.

Data flow and feedback mechanisms: The framework integrates three data streams (Figure 1): (1) empirical data from field trials provide practice-specific emission factors (e.g., biochar: 16.2% N2O reduction [9]; 4R + EEF: 55–64% reduction [18]); (2) spatially explicit emission models account for soil types, climate zones, and management regimes to generate region-specific mitigation potentials; and (3) socio-economic adoption pathways incorporate farmer constraints (capital access, and tenure, extension service availability) to adjust technical potential by realistic adoption probabilities. Information flows downward from carbon budgets to farm-level guidance, while monitoring data feeds upward (purple dashed arrow, Figure 2), enabling adaptive management that continuously refines emission factors, practice recommendations, and policy mechanisms based on observed field performance.

Operational distinctiveness: Unlike existing frameworks that operate primarily at field-level (4R, CSA) or macro-scale (LEDS, IAMs), ICEMF uniquely bridges these scales through three interconnected components: (1) empirical data integration from diverse field practices; (2) spatially explicit emission modeling capturing regional heterogeneity in soil, climate, and farming systems; and (3) socio-economic adoption pathways ensuring practical scalability by adjusting technical potential (e.g., biochar’s 16.2% N2O reduction) by realistic adoption rates (5–10% baseline, increasing to 40–60% with bundled support [28]. This multi-scalar integration enables ICEMF to translate local agricultural interventions into quantifiable contributions toward global emission reduction targets while maintaining farmer-centered feasibility.

Implementation pathway: ICEMF is currently in a conceptual stage, with application potential illustrated through schematic representations (Figure 1 and Figure 2) and validated through five regional case studies demonstrating how the framework adapts to diverse agricultural systems, from Indonesian agroforestry (74–320 Mg C ha−1 sequestration) to German biochar application (consistent 16.2% N2O reduction) to Indian precision fertilization (12–20% emission reductions).

2. Materials and Methods

The literature search was conducted using major academic databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Springer, MDPI, Taylor & Francis, Cambridge Journals, and Google Scholar to ensure comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed studies on GHG emissions from agricultural crops and mitigation strategies. These databases were specifically selected for their extensive archives of peer-reviewed academic journals in agricultural sciences, environmental sciences, climate change mitigation, and precision agriculture. This approach ensured that sourced articles were of high academic and scientific rigor and directly relevant to our research themes.

This review covers research papers published from 1997 to 2025. The selected articles were organized and discussed within the relevant thematic sections of the manuscript. Search terms employed in the database queries included various combinations of keywords such as “greenhouse gas emissions,” “agricultural crops,” “mitigation,” “management practices,” “climate-smart agriculture, “digital agriculture technologies,” “monitoring and verification,” and “socio-economic adoption.” This specific selection of keywords aimed to encompass a broad spectrum of research topics within the scope of agricultural practices and their environmental impacts. Additional references were traced through citation tracking of key articles to capture significant contributions not directly retrieved in the initial search. Studies were included if they focused on GHG emissions from agricultural crop systems and examined mitigation or management strategies with relevance to CO2, CH4, or N2O. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were selected to ensure recent and reliable findings. Exclusion criteria comprised studies that addressed emissions unrelated to crops (e.g., purely livestock systems), articles without empirical or methodological relevance, non-English publications, and gray literature such as reports or opinion pieces.

From the eligible studies, key information such as author details, year of publication, study location, crop type, greenhouse gases assessed, and mitigation practices investigated was extracted. Over 350 studies were initially identified and screened for their relevance. After screening for relevance, 244 studies met the inclusion criteria and were thoroughly analyzed and included in the final review. Studies were categorized according to thematic domains relevant to the ICEMF: (1) GHG emission sources and quantification: papers reporting emission measurements, emission factors, or spatial–temporal variability of CO2, CH4, and N2O from crop systems. (2) Practice-level mitigation strategies: research on specific interventions including biochar application, precision nutrient management, conservation tillage, crop rotation, agroforestry, cover cropping, crop diversification, and crop–livestock integration. (3) Digital agriculture technologies: studies addressing IoT sensors, remote sensing, precision agriculture platforms, wireless sensor networks (WSN), satellite monitoring, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and AI/machine learning applications. (4) MRV systems: papers on emission measurement protocols, carbon accounting methodologies, life cycle assessments, and verification frameworks. (5) Socio-economic adoption and implementation: research on farmer adoption barriers, cost-effectiveness analyses, policy frameworks, and extension service delivery. A narrative synthesis approach was adopted to integrate findings across diverse study designs, with emphasis on identifying common trends, contradictions, and knowledge gaps. Where possible, comparisons were drawn between regional and global perspectives to highlight context-specific variations in emission sources and mitigation outcomes. While this framework supports a comprehensive synthesis, several limitations remain. Variability in study designs, life cycle assessment boundaries, and measurement techniques restrict direct comparability of results. In addition, regional disparities in data availability create potential biases toward well-studied systems, while socio-economic dimensions are often underreported. These limitations underscore the need for standardized methodologies and long-term, context-specific studies to strengthen the evidence base.

This review synthesizes evidence on agricultural GHG mitigation practices and proposes ICEMF as a conceptual framework to integrate dispersed knowledge into an operational decision-support approach. The review is structured to (1) evaluate practice-level effectiveness across diverse interventions, (2) identify critical gaps in existing frameworks, and (3) propose ICEMF’s novel integration of spatial modeling with adoption pathways as a solution to bridge field-to-policy scales (Figure 2). Unlike previous reviews focusing on single practices or policy frameworks, this review’s novelty lies in synthesizing cross-scale evidence to demonstrate how ICEMF’s two core innovations (spatially explicit modeling + adoption integration) address the operational gap between technical potential and achievable impact (Figure 2).

2.1. Meta-Analysis Interpretation and Quality Assessment

We report effect sizes from published meta-analyses, including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), sample sizes (both the number of observations and the number of studies), heterogeneity measures (I2 statistic), and assessments of publication bias. Heterogeneity interpretation follows standard guidelines: I2 values of 0–25% indicate low heterogeneity, 25–50% moderate, 50–75% substantial, and >75% considerable heterogeneity requiring careful interpretation of context-specific factors.

Quality assessment of meta-analytic evidence considered:

- (1)

- Sample size (>50 observations considered high quality)

- (2)

- Heterogeneity assessment and subgroup analyses

- (3)

- Publication bias testing (funnel plots, Egger’s test)

- (4)

- Climate and soil stratification

- (5)

- Duration of included studies (>2 years preferred for agricultural practices). Practices were assigned quality scores of HIGH (meeting 4–5 criteria), MODERATE (2–3 criteria), or LOW (0–1 criteria) to guide the interpretation of evidence strength (Supplementary Table S2).

2.2. Limitations of Meta-Analytic Evidence

Several limitations constrain the interpretation of the meta-analytic findings presented in this review: (1) High heterogeneity (I2 > 75% for several practices) indicates substantial context-dependency, requiring careful extrapolation beyond the specific soil–climate management conditions of original studies. (2) Publication bias, where detected, may lead to overestimation of effect sizes as studies with null or negative results are less likely to be published. (3) Long-term field validation (>10 years) remains limited for many practices, with most studies spanning 1–6 years, creating uncertainty about persistence of mitigation effects. (4) Tropical and semi-arid systems are underrepresented relative to temperate zones in meta-analytic datasets, limiting confidence in global extrapolation. (5) Interaction effects between practices (e.g., biochar combined with precision fertilization) are rarely quantified in existing syntheses, preventing assessment of synergistic or antagonistic outcomes. These limitations underscore ICEMF’s emphasis on spatially explicit modeling that accounts for local context rather than applying universal effect sizes.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

We evaluated evidence quality using a structured rubric assessing experimental design (randomization, replication), study duration, GHG measurement methods, statistical power, and context reporting. Meta-analyses were additionally evaluated for sample size (≥100 observations preferred), heterogeneity assessment (I2), publication bias testing, and climate/soil stratification. Studies were classified as high (8–10 points), moderate (5–7 points), or low quality (0–4 points). Five primary bias sources were identified: publication bias (positive results are preferentially published), measurement bias (high coefficient of variation in GHG fluxes: 30–300%), duration bias (most studies < 3 years), geographic bias (temperate regions overrepresented), and interaction bias (single-practice focus). Key meta-analyses cited for quantitative effect sizes varied in quality. High-quality meta-analyses (biochar [9], cover crops [115]) scored ≥ 8/10 with >100 observations, formal bias testing, and climate stratification. Additional meta-analyses (no-till [115]) provided moderate-quality evidence with context-specific findings. Complete quality assessment rubrics, scoring criteria, individual study evaluations, coefficient of variation analysis, and detailed bias mitigation strategies are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

2.4. Synthesis of Context-Specific Effectiveness

To enable systematic comparison of mitigation practice effectiveness across diverse agroecological contexts, we organized extracted data into a comprehensive impact matrix structured by three dimensions: (1) climatic zone (temperate, tropical, subtropical, humid, semi-arid), (2) soil texture and characteristics (acidic soils, clay, sandy, paddy soils, various textures), and (3) cropping system (rice, wheat, corn/maize, vegetables, mixed systems, general cropland).

For each practice-context combination, we compiled quantitative impacts on N2O, CH4, and CO2 emissions, soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration, yield effects, and practice durability. We extracted heterogeneity measures (I2 statistics) from meta-analyses to assess consistency of effects across studies, with I2 values of 0–25% indicating low heterogeneity, 25–50% moderate, 50–75% substantial, and >75% considerable heterogeneity. Where available, we reported 95% CI to quantify estimation uncertainty.

Evidence quality for each practice-context combination was rated using a structured rubric assessing: (i) sample size (≥100 observations preferred for high quality), (ii) formal heterogeneity assessment and subgroup analyses, (iii) publication bias testing (funnel plots, Egger’s test), (iv) climate and soil stratification, and (v) study duration (≥2 years for agricultural practices). Practices were assigned quality scores of HIGH (8–10 points, meeting 4–5 criteria), MODERATE (5–7 points, meeting 2–3 criteria), or LOW (0–4 points, meeting 0–1 criteria) to guide interpretation of evidence strength and generalizability.

This matrix structure enables identification of (1) context-specific effectiveness patterns informing spatially explicit implementation strategies, (2) practices with consistent versus variable responses across contexts, (3) knowledge gaps requiring additional research investment, and (4) mechanistic insights into soil–climate management interactions determining mitigation outcomes. The synthesis directly supports ICEMF’s first core innovation, spatially explicit emission modeling that accounts for local context rather than applying universal effect sizes across heterogeneous landscapes.

2.5. Baseline Specification and Sequential Accounting for Nitrogen Management

All nitrogen optimization mitigation estimates in ICEMF use standardized baselines to ensure comparability and prevent double counting. For intensive temperate cereal systems, the reference baseline is 165–190 kg N ha−1 synthetic fertilizer application (representative of US Corn Belt maize and European wheat), corresponding to 1.8–4.6 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 depending on soil texture, water-filled pore space, and climate [18,86,91]. Regional baselines vary substantially: 200–250 kg N ha−1 in intensive Asian rice-wheat systems [116], 120–160 kg N ha−1 in moderate-input temperate systems [117], and 40–80 kg N ha−1 in smallholder African systems [118].

ICEMF incorporates region-specific N2O emission factors (percentage of applied nitrogen emitted as N2O-N) ranging from 0.5–1.5% in temperate dry climates to 1.5–3.0% in temperate humid climates, accounting for soil–climate interactions affecting denitrification and nitrification processes [18,86,119]. These emission factors scale field-level nitrogen management interventions to regional mitigation estimates while capturing non-linear emission responses at high nitrogen application rates (exponential increase, β = 1.6–2.0) [119].

To prevent double-counting when multiple nitrogen management practices are combined, ICEMF employs sequential accounting where the first practice modifies the baseline for subsequent interventions. For example, legume-based crop rotation reduces synthetic nitrogen requirements from 180 to 63 kg N ha−1 and decreases N2O emissions by 39% [120,121]; applying precision fertilization (4R stewardship) to this reduced nitrogen baseline achieves an additional 55–64% reduction in remaining emissions [18], yielding a total sequential reduction of 70–75% rather than an impossible additive 94–103%. Similarly, biochar application (16.2% N2O reduction) [9] combined with precision fertilization targets overlapping nitrogen transformation pathways; field validation studies document combined reductions of 38.8% [122] rather than the theoretical additive 71%, confirming the necessity of sequential accounting. This approach ensures ICEMF provides conservative, verifiable mitigation estimates for bundled practice scenarios.

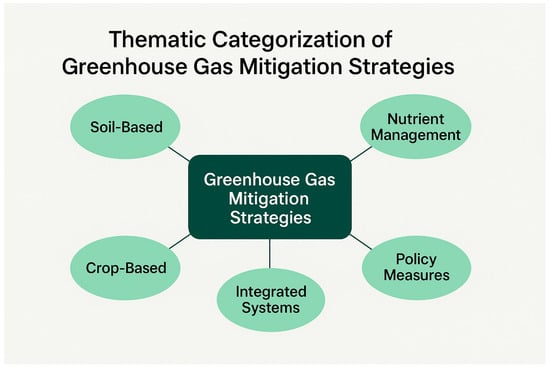

3. Thematic Analysis

Figure 3 shows thematic analysis of the reviewed literature which reveals that mitigation strategies in agricultural crop systems can be broadly grouped into five categories: soil-based approaches (e.g., biochar application, conservation tillage), crop-based practices (e.g., diversification, agroforestry, cover cropping), nutrient management (e.g., precision fertilization, 4R stewardship), integrated systems (e.g., crop–livestock recoupling, constructed wetlands), and policy or socio-economic interventions (e.g., carbon trading, CSA policies). This categorization highlights both the diversity and interconnectedness of approaches, with many practices offering co-benefits such as enhanced soil health, improved productivity, and resilience to climate variability. However, adoption remains uneven, and their effectiveness is often context-specific, emphasizing the need for adaptive frameworks like the ICEMF to harmonize local practices with global climate targets.

Figure 3.

Thematic categorization of GHG mitigation strategies in agricultural crop systems (soil-based, crop-based, nutrient management, integrated systems, and policy measures).

3.1. Sources and Trends of GHG Emissions in Agriculture

Agricultural systems contribute significantly to global GHG emissions, primarily through CO2, CH4, and N2O [123]. Soil organic matter degradation, excessive fertilizer use, and land-use change release CO2, while enteric fermentation and flooded rice fields are major sources of CH4, and N2O arises mainly from nitrogen fertilizer application and manure management, with its high GWP making it a critical focus for mitigation [124]. Recent studies indicate that global agricultural emissions have steadily increased over the past decades, with hotspots in Asia, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa driven by crop intensification and rising fertilizer demand [125,126]. Seasonal variations, cropping intensity, and irrigation practices further influence emission patterns, underlining the complexity of agricultural GHG dynamics [127,128].

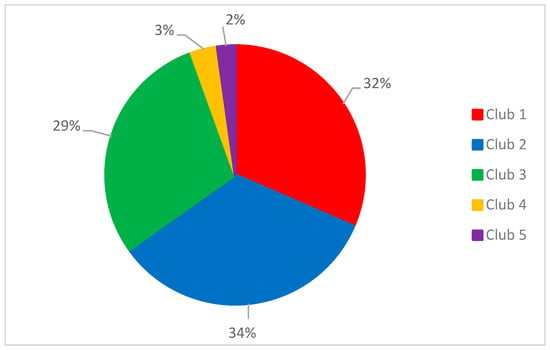

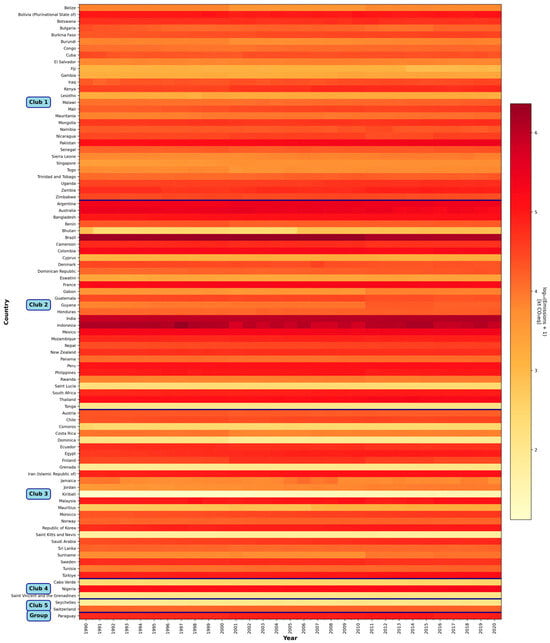

The study by Akram and Ali [129] examines the convergence hypothesis of GHG emissions across 93 countries from 1980 to 2017. Using the Phillips and Sul test [130], the study finds evidence of divergence in emission trends, suggesting that countries follow different convergence paths. Clustering algorithms identify five distinct convergence clubs, indicating the need for region-specific policies. Figure 4 presents the GHG emissions in the agriculture sector across 93 countries (1980–2017), as a group, based on the Phillips and Sul Panel Club Convergence Test [130]. Figure 4 presents the GHG emission trajectories for each convergence club, revealing striking disparities in emission patterns. Club characteristics: Club 1 (n = 29) exhibits high emission variability with countries predominantly from sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and South Asia. Club 2 (n = 31) includes major agricultural producers with moderate emission trajectories (India, Brazil, Australia, France). Club 3 (n = 27) demonstrates declining trends, featuring industrialized nations and emerging economies (China, Republic of Korea, European countries). Club 4 (n = 3) represents a transition phase with heterogeneous characteristics. Club 5 (n = 2: Seychelles, Switzerland) shows the lowest emissions, providing policy models for other clubs. Paraguay (n = 1) forms a separate group with unique emission characteristics not conforming to the five club patterns. The findings emphasize the importance of considering these divergent paths when designing GHG mitigation strategies and the impact of policy transfers across countries. The study suggests that countries in Clubs 1–4 should adopt agricultural policies from Club 5, where GHG emissions are lower, particularly focusing on cleaner energy. Strategies to reduce GHG emissions include improving sector efficiency, fostering innovation, reducing deforestation, and using cleaner energy with subsidies. Additionally, addressing poverty and adopting low-cost energy technologies in agriculture are key to sustainable development in lower- and middle-income countries.

Figure 4.

Global disparities in agricultural greenhouse gas emissions across 93 countries grouped by convergence clubs (1980–2017). Countries were assigned to five convergence clubs based on [130] panel club convergence test, as reported by [129]. Data source: FAO statistics division (FAOSTAT) emissions—agriculture database (accessed 15 June 2020; database version: June 2020 release). Dataset: “emissions totals” (domain code: GT), element: “emissions (CO2eq)” aggregated from all agricultural sources, item: “agricultural total,” unit: kilotonnes CO2 equivalent (source: [129]).

Building on the study by [129], which examines the convergence hypothesis of GHG emissions across 93 countries from 1980 to 2017, we have generated heatmaps for each of the identified convergence clubs, showing total emissions from 1990 to 2020. The heatmaps visually represent the emissions trends within each club, highlighting the divergent paths observed in the study. These visualizations support the need for region-specific GHG mitigation strategies, emphasizing the importance of targeted policies that reflect the unique emission patterns of each club. The findings underscore the role of tailored interventions to address the emission disparities across countries. The data for these heatmaps is sourced from the FAOSTAT Database (FAO, 2020). Figure 5 presents heatmaps illustrating the total GHG emissions (in kilotons) across five regional convergence clubs, as identified through the Phillips and Sul convergence test [129]. These heatmaps visually represent emissions trends from 1990 to 2020, highlighting the disparities in emission patterns across regions. This regional analysis underscores the need for context-specific mitigation strategies and informs the ICEMF framework by emphasizing the importance of spatially explicit emission modeling.

Figure 5.

Comprehensive heatmap of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions across 91 countries grouped by convergence clubs (1990–2020). Total agricultural GHG emissions (kilotonnes CO2 equivalent) for 91 countries organized into convergence clubs based on the [130] panel club convergence test as reported by [129]. Countries are grouped and displayed by convergence club: Club 1 (n = 29), Club 2 (n = 31), Club 3 (n = 25), Club 4 (n = 3), Club 5 (n = 2), and Paraguay (n = 1, an independent group). Within each club, countries are arranged alphabetically. Navy horizontal lines separate convergence clubs. Color gradient represents log10-transformed emission values: light yellow (low emissions) to dark red (high emissions), enabling visualization across a four-order magnitude range (31 to 1,412,572 kt CO2 eq in 2020). Emission values in kilotons CO2 equivalent from agricultural activities. White cells indicate missing data for specific country-year combinations. Data source: FAOSTAT emissions—agriculture database (FAO of the United Nations, 2023 release, accessed 25 September 2025). Dataset: domain GT (emissions–agriculture), element: emissions (CO2eq) (AR5), item: agrifood systems total, Unit: kilotonnes CO2 equivalent.

Mukwada, Taylor [131] reported that the trends also reveal significant regional disparities. Developed countries have shown modest declines in emissions due to improved nutrient-use efficiency, conservation tillage, and climate-smart practices, while developing nations continue to face steep increases as agricultural expansion meets food security demands. Studies highlight that rice and maize systems dominate CH4 and N2O contributions, respectively, while wheat and soybean systems contribute substantial CO2 through soil- and land-use-related emissions [132]. Moreover, climate change feedback loops, including rising temperatures and extreme weather events, exacerbate emission rates and reduce the mitigation capacity of soils [133]. Although progress has been made in quantifying emissions, gaps remain in capturing indirect sources such as post-harvest processes and regional variability in emission factors, emphasizing the need for refined monitoring frameworks and targeted interventions [21]. Table 2 presents a summary of key studies highlighting the sources and trends of GHG emissions in agriculture, their drivers, and regional or system-specific notes.

Table 2.

Global sources and drivers of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

3.2. Evaluation of Crop and Soil Management Practices

Crop and soil management practices are central to reducing GHG emissions from agriculture. Conservation tillage, cover cropping, and crop diversification have been shown to enhance soil organic carbon stocks and reduce CO2 release by minimizing soil disturbance and improving residue retention [7,134,135]. Agroforestry systems contribute to long-term carbon sequestration while also providing ecosystem services such as biodiversity support and microclimate regulation [136]. Biochar application has emerged as a promising soil amendment, capable of enhancing soil structure, microbial activity, and long-term carbon storage while mitigating CH4 and N2O fluxes [137]. In temperate agricultural regions, biochar demonstrates substantially more consistent and predictable soil CO2 emissions mitigation effects compared to no-till agriculture, which exhibits high climate and soil-dependent variability [138]. Biochar application increases soil organic carbon sequestration by 61% (95% CI: 36–90%) across temperate zones based on meta-analysis with high heterogeneity (I2 = 85%), indicating substantial variation by soil type, application rate, and biochar feedstock [9], though tropical system data remain limited, and decreases annual CO2 emissions by 13.0–17.6% within 1–2 years [139], whereas no-till effectiveness in temperate regions depends critically on soil texture, organic carbon content, and precipitation patterns [140], with future projections showing declining mitigation potential of only 1.4–1.7 Mg ha−1 over 30 years under climate change scenarios [141]. The superior consistency of biochar in temperate climates stems from its intrinsic recalcitrance, with 97% of biochar carbon persisting in stable form. Modeled mean residence times average 556 years, with ranges from 102 years (low-temperature pyrolysis of labile feedstocks) to 107,000 years (high-temperature pyrolysis of woody biomass), making biochar largely independent of temperate climate fluctuations in temperature and precipitation [142]. However, these estimates derive primarily from laboratory incubations and modeling extrapolations; field validation beyond 10–15 years remains limited, and long-term persistence under diverse agricultural conditions requires further empirical verification [142], rendering it largely independent of temperate climate fluctuations in temperature and precipitation. In contrast, no-till effectiveness in temperate regions is fundamentally constrained by soil-specific properties and temporal dynamics of seasonal carbon fluxes [143], making it a less reliable climate mitigation strategy compared to biochar application. Biochar reduced N2O emissions by 16.2% (95% CI: 9.8–22.6%) based on meta-analysis of 119 paired observations from 18 studies with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 72%) and no publication bias detected [9], whereas global systematic analysis of 106 studies across 372 sites demonstrates that cover crops reduce nitrogen leaching and net greenhouse gas balance by 2.06 Mg CO2-eq ha−1 yr−1 without significantly affecting direct N2O emissions [144]. Meta-analysis shows that alternate wetting and drying (AWD) reduces CH4 emissions by 53% and GWP by 44% in rice systems, though N2O emissions increase by 105%, and the net effect remains beneficial [145]. Systematic review of 11,768 yield observations from 462 field experiments reveals legume-based crop rotations increase subsequent crop yields by 20%, with greater benefits (32%) in low-yielding environments [146] (Table 3) (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis evidence for key mitigation practices for N2O mitigation in temperate agricultural regions.

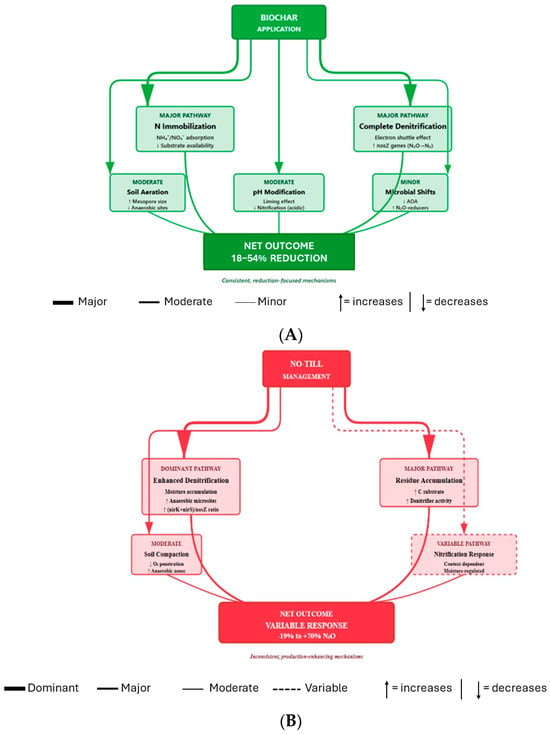

Research has identified multiple interconnected mechanisms through which biochar reduces soil N2O emissions in agricultural systems. Rather than operating through a single pathway, biochar’s effectiveness derives from synergistic interactions among several primary mechanisms, each contributing differentially to overall N2O reduction (Figure 6A).

Nitrogen immobilization and adsorption represent a major mechanism, operating through direct adsorption of NH4+ and NO3− onto biochar’s aromatic carbon surface with high cation exchange capacity, thereby reducing substrate availability for nitrification and denitrification pathways that produce N2O [10]. Complete denitrification enhancement represents another dominant mechanism, functioning through biochar’s electron shuttle effect that facilitates electron transfer to soil denitrifying microorganisms and promotes the final reduction of N2O to N2 through upregulation of nosZ genes encoding N2O reductase [149].

Several secondary mechanisms contribute additional mitigation effects: soil physical modification through increases in mesopore size and specific surface area that enhance aeration and reduce anaerobic microsites; soil pH modification through the liming effect that reduces nitrification rates in acidic soils; and microbial community shifts that reduce ammonia-oxidizing archaea populations while promoting N2O-reducing bacteria [10,150]. These interconnected mechanisms produce consistent field-observed N2O reductions ranging from 18% to 54%, with substantially greater reductions (up to 84%) when biochar is combined with nitrogen fertilization [122,148,151].

In contrast, the high variability in no-till N2O responses ranging from 19% reductions to 70% increases [12,115] stems from the fundamentally production-enhancing nature of its primary mechanisms (Figure 6B). Unlike biochar, which operates through multiple N2O reduction pathways, no-till’s mechanisms predominantly create conditions favorable for N2O production. Enhanced denitrification through moisture accumulation represents the dominant mechanism, creating anaerobic microsites where incomplete denitrification predominates. No-till significantly increased soil denitrification by 85% compared to conventional tillage, with a 33% increase in the (nirK + nirS)/nosZ gene ratio, indicating that N2O is released rather than being further reduced to N2 [152]. This moisture-induced denitrification is particularly problematic in humid temperate regions where water-filled pore space frequently exceeds 70%, creating sustained anaerobic conditions that favor N2O production over complete reduction to N2.

Substrate availability from residue accumulation further promotes N2O production by providing readily available carbon sources for denitrifying microorganisms, while soil compaction effects restrict oxygen penetration and create additional anaerobic zones favorable for denitrification [152,153]. Nitrification responses add complexity, as they vary considerably depending on local moisture regimes and soil conditions, making outcomes difficult to predict [153]. The mechanistic basis for no-till’s inconsistency contrasts fundamentally with biochar’s reliability. Where biochar’s mechanisms actively convert N2O to N2 and immobilize nitrogen substrates, no-till’s mechanisms create environmental conditions that favor N2O production. This mechanistic divergence explains why meta-analyses show that conservation tillage increased N2O emissions by 17.8% on average (95% CI: 8.5–27.1%) based on meta-analysis of 154 observations from 35 studies with high heterogeneity (I2 = 76%), with greater emission increases in humid temperate regions (25–35%) compared to semi-arid systems (−5% to +10%) [115], despite some individual studies reporting reductions. The consistency of outcomes depends on whether the dominant mechanisms promote N2O reduction (as in biochar application) or N2O production (as in no-till management). For temperate regions prioritizing consistent and reliable N2O mitigation, biochar’s reduction-focused mechanisms represent a more dependable approach than no-till’s production-enhancing pathways, though local conditions and proper application rates remain critical considerations for both practices.

Figure 6.

Conceptual framework comparing mechanisms driving contrasting N2O emission responses between biochar and no-till management systems. (A) Biochar reduces N2O through multiple reduction-focused pathways, including nitrogen immobilization, complete denitrification enhancement (N2O → N2), improved aeration, pH modification, and microbial shifts, producing consistent 18–54% emission reductions [10,148,149]. (B) No-till creates production-enhancing conditions through dominant moisture accumulation effects, residue-derived substrate availability, compaction, and variable nitrification responses, resulting in inconsistent outcomes from −19% to +70% [12,115,152]. Arrow thickness indicates relative mechanistic importance (thick = dominant/major; medium = moderate; thin = minor; dashed = variable). The fundamental difference in mechanism directionality reduction focused versus production enhancing explains biochar’s superior reliability for N2O mitigation in temperate agricultural systems compared to no-till management.

Crop rotation is a key practice in sustainable farming, involving the sequence of planting various crops in the same field over multiple seasons to enhance soil fertility and productivity. It is distinct from other methods, such as intercropping and monoculture (monocropping) [154]. Crop rotation increases soil carbon sequestration and lowers CO2 emissions [155]. The case study by Lötjönen and Ollikainen [156] outlines the environmental benefits of crop rotation over monoculture, particularly in terms of reduced fertilization needs, lower nitrogen runoff, and decreased GHG emissions. Rotating legumes, like clover-wheat, also lowers GHG emissions and nitrogen runoff [156,157]. Crop rotation helps reduce CO2 emissions by improving soil organic matter (SOM) and minimizing the need for tillage and fertilizers. Systems that incorporate legumes and perennials enhance carbon input and sequestration over time [158,159]. Al-Musawi, Vona [7] highlights the significance of various crop rotation systems for both agricultural and environmental sustainability. The authors explain that crop rotation can notably improve soil structure and organic matter levels, as well as boost nutrient cycling. Additionally, when legumes are incorporated into rotations instead of monoculture systems in Europe, soil organic carbon increases by up to 18%. This practice also helps reduce GHG emissions, promote carbon sequestration, and lower nutrient leaching and pesticide runoff. Legume-based rotations also influence other greenhouse gases. By improving nitrogen efficiency, legume-based rotations decreased N2O emissions by 39% (range: 28–51%) in long-term field trials in temperate corn systems (Monmouth, IL, USA) [120], though comprehensive meta-analysis across diverse agroecological zones is not yet available, limiting generalizability [120]. In flooded rice systems, rotating with upland crops like maize or sorghum can reduce CH4 emissions by up to 84% by interrupting anaerobic soil conditions [160]. Similarly, improved irrigation techniques, such as an AWD in rice systems, have demonstrated the potential to lower CH4 emissions without reducing yields [161]. These strategies underscore the technical viability of soil- and crop-based interventions, though their outcomes are often highly context-specific and influenced by environmental and management factors [162].

Despite their potential, significant challenges limit the widespread adoption of these practices. Research indicates variability in mitigation outcomes due to soil type, climate conditions, and crop management intensity, making generalized recommendations difficult [163]. For example, while no-till farming may enhance soil carbon in temperate zones, its benefits in tropical systems remain inconsistent [164]. Economic and social barriers, including high costs of inputs, lack of farmer awareness, and limited access to technologies, also hinder uptake [165]. Moreover, long-term impacts are not always well documented, with short-term studies dominating the literature and leaving uncertainties about sustainability over decades [166]. Addressing these gaps requires integrative approaches that combine technical innovations with enabling policies, financial incentives, and knowledge-sharing networks to promote scalable, farmer-centered solutions [167]. Table 4 summarizes key studies on crop and soil management practices, highlighting their potential for GHG mitigation along with associated challenges and limitations.

Table 4.

Evaluation of crop and soil management practices for GHG mitigation.

Context-Dependent Effectiveness: A Systematic Comparison

The Supplementary Table S3 presents a comprehensive matrix synthesizing practice-specific impacts across climatic zones, soil textures, and cropping systems. This systematic organization reveals several critical patterns:

Climate zone dependency: Practice effectiveness varies substantially by climate. Biochar achieves 16.2% N2O reduction (95% CI: 9.8–22.6%, I2 = 72%) in temperate systems based on 119 observations from 18 studies, nearly double the 8–12% reduction in tropical systems with limited validation (<30 observations) [9,137,185]. This reflects differences in moisture regimes, decomposition rates, and microbial communities, with temperate benefits sustained over 4–6 years [10].

No-till shows extreme variability (212 observations from 40 studies, I2 = 89%): effects range from −19% to +1% depending on conditions, with humid temperate regions showing increases while semi-arid systems show modest reductions [115,152]. AWD in rice systems demonstrates climate-appropriate design: −53% CH4 but +105% N2O, achieving net −44% GWP with no yield penalty [145,179].