Abstract

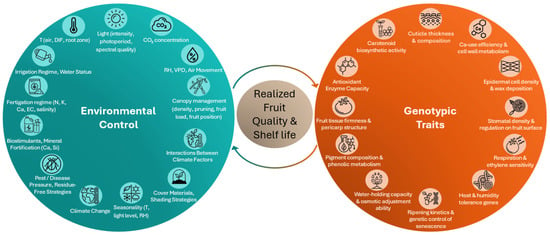

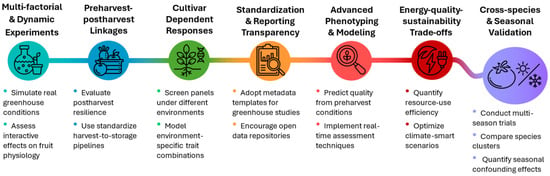

This review integrates current knowledge on how greenhouse conditions regulate the nutritional quality and shelf life of tomato, cucumber, and sweet pepper. Preharvest environmental factors jointly shape fruit composition, firmness, and storage performance through their control of photosynthesis, assimilate partitioning, and structural stability. Across all variables, light intensity and fruit temperature emerge as the dominant determinants of overall quality and shelf life potential. Relative air humidity (RH), irrigation regime, and nutrient balance primarily affect firmness, water loss, and physiological disorders, while CO2 enrichment, shading, and mineral or biostimulant inputs exert secondary yet consistent effects. Comparative evaluation shows that tomato is most sensitive to temperature and RH, cucumber to water status and epidermal stress, and sweet pepper to radiation for color and antioxidant development. These distinctions confirm that no single climatic optimization can be universally applied, and management must therefore target species-specific physiological constraints to sustain both nutritional excellence and storage performance. Major knowledge gaps remain, particularly regarding the combined effects of interacting environmental drivers and the integration of physiological responses with postharvest behavior. Future research should adopt multifactorial designs and predictive modeling to support climate-smart greenhouse strategies that optimize quality and storability under variable growing conditions.

1. Introduction

Preharvest environmental conditions strongly influence both the nutritional composition and storability of vegetables [1,2]. In greenhouse cultivation, the microclimate [i.e., temperature, light, relative air humidity (RH), CO2 concentration, and the supply of water and nutrients] can be precisely regulated. Although these parameters are typically adjusted to maximize yield, they also affect fruit physiology and biochemical composition, and thereby determine postharvest performance [3,4]. Understanding how controlled environmental factors shape fruit metabolism and structure is therefore essential for achieving both productivity and product integrity. Consumer acceptance further depends on aroma-related volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are also influenced by preharvest climate but are beyond the primary scope of this review.

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) and sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) were selected as model crops because they dominate greenhouse vegetable production globally. These species differ markedly in fruit physiology [5,6,7], offering an opportunity to explore how similar cultivation environments lead to distinct nutritional and structural outcomes. Their wide genetic diversity, continuous year-round cultivation, and sensitivity to environmental variation make them ideal indicators for assessing the effects of microclimate management on fruit quality and shelf life [8,9,10].

Only studies conducted under greenhouse conditions were included, ensuring that the evaluated responses reflect the complex but controllable environments encountered in commercial production. Climate-chamber studies were excluded because they do not capture the combined and fluctuating stresses typical of real cultivation systems, while field studies were omitted due to limited capacity for environmental manipulation. Priority was placed on recent literature (the last five years), complemented by landmark earlier studies where relevant. By focusing on greenhouse experiments, this review evaluates responses to directly controlled environmental drivers [2,11], enabling mechanistic interpretation and facilitating the translation of findings into practical cultivation guidelines.

Despite extensive studies on individual environmental factors, a mechanistic, cross-species synthesis linking preharvest microclimate to postharvest outcomes remains incomplete. The objective of this work is to integrate current evidence on how greenhouse cultivation conditions influence the nutritional, structural and physiological quality of tomato, cucumber and sweet pepper fruits, both at harvest and during storage. The review aims to identify the most decisive environmental factors, quantify their relative impact across species, and outline management strategies that improve nutritional value, enhance fruit resilience and prolong shelf life. By linking cultivation environment with fruit physiology, the present study contributes to the design of climate-smart greenhouse systems that sustain high yield and superior postharvest performance.

2. Concepts and Metrics

2.1. Nutritional Quality: Definitions, Compounds, and Analytical Endpoints

The nutritional quality of greenhouse-grown vegetables reflects the concentration and balance of biochemical constituents with health-promoting and sensory properties [12,13]. These include soluble carbohydrates, organic acids, vitamins, pigments, phenolic compounds, and minerals [12,13]. Their concentrations are strongly influenced by environmental factors, regulating primary and secondary metabolism [12,13]. Quantification is typically achieved through physicochemical analyses such as refractometry [soluble solids (°Brix)], titration (acidity), spectrophotometric assays (pigments and antioxidants), and chromatographic or mass spectrometric methods (detailed profiling).

In tomato, nutritional quality is shaped by sweetness, acidity, and color (Table 1) [14,15]. Soluble sugars and organic acids contribute substantially to flavor [15,16], while carotenoids, primarily lycopene and β-carotene, define red coloration and respond to light and temperature [15,17]. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C), phenolics and minerals [e.g., potassium (K) and calcium (Ca)] contribute to antioxidant capacity and tissue stability [14,17,18]. Analytical endpoints include total soluble solids, titratable acidity (TA), lycopene, ascorbic acid, and phenolics [15,19].

In cucumber, nutritional quality is characterized by high water content (WC), moderate levels of reducing sugars, and low concentrations of acids and secondary metabolites (Table 1) [20]. The main determinants of quality are crisp texture, refreshing flavor, and the maintenance of chlorophyll and green coloration [20,21]. Ascorbic acid and phenolics are present at low levels but respond to environmental cues such as light or mild stress [20,22,23]. Nutritional assessment focuses on soluble solids, firmness, ascorbic acid, and total chlorophyll, reflecting both compositional and textural traits [20,24].

Sweet pepper is rich in ascorbic acid and carotenoids, which accumulate during ripening (Table 1) [23,25]. Ascorbic acid concentrations can exceed most vegetables, while carotenoids (e.g., capsanthin, capsorubin, and β-carotene) contribute to pigmentation and antioxidant potential [23,25,26]. Phenolics and flavonoids enhance the total antioxidant capacity [23,26]. Analytical endpoints include ascorbic acid, total carotenoids, phenolics, and soluble solids [23]. Because these metabolites are responsive to temperature, light, and nutrient balance during growth, their accumulation provides a sensitive indicator of how preharvest conditions affect nutritional quality [2,25].

Table 1.

Key physiological and compositional traits determining nutritional quality and shelf life (SL) in greenhouse-grown tomato, cucumber, and sweet pepper. ascorbic acid = vitamin C; a*, green (–) → red (+) axis; b*, blue (–) → yellow (+) axis; β-carotene, beta-carotene; °Brix, soluble solids content; FW, fresh weight; RH, relative air humidity; T, temperature; TA, titratable acidity; WC, water content. Arrows indicate direction of projected change (↓ decrease). Definitions of physiological disorders are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Key physiological and compositional traits determining nutritional quality and shelf life (SL) in greenhouse-grown tomato, cucumber, and sweet pepper. ascorbic acid = vitamin C; a*, green (–) → red (+) axis; b*, blue (–) → yellow (+) axis; β-carotene, beta-carotene; °Brix, soluble solids content; FW, fresh weight; RH, relative air humidity; T, temperature; TA, titratable acidity; WC, water content. Arrows indicate direction of projected change (↓ decrease). Definitions of physiological disorders are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

| Trait Category | Tomato | Cucumber | Sweet Pepper | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ripening physiology | Climacteric; strong ethylene & respiration peaks; ripening continues after harvest | Non-climacteric; quality fixed at harvest; high respiration | Non-climacteric; biochemical color transition (green → red/yellow); no ethylene burst | [6,27,28,29] |

| Dominant quality determinants | Soluble sugars, organic acids, lycopene + β-carotene, ascorbic acid, phenolics | WC, firmness, chlorophyll, ascorbic acid (moderate), phenolics (low) | Ascorbic acid (very high), carotenoids (capsanthin, capsorubin, β-carotene), phenolics/flavonoids | [14,24,25] |

| Typical analytical endpoints | °Brix, TA, lycopene, ascorbic acid, phenolics | °Brix, firmness, ascorbic acid, chlorophyll, color (a*/b*) | °Brix, ascorbic acid, total carotenoids, total phenolics, antioxidant capacity | [20,23,24] |

| Major nutritional compounds affected by environment | Sugars, acids, carotenoids, ascorbic acid, phenolics | Sugars, chlorophyll, ascorbic acid, firmness-related polysaccharides | Ascorbic acid, carotenoids, phenolics; influenced by light & nutrient balance | [15,22,30] |

| Primary SL limitations | Softening, water loss, cracking, blotchy ripening, decay | Rapid turgor loss, yellowing, chilling injury, decay | Shriveling, firmness loss, color fading, chilling injury, decay | [31,32,33] |

| Key kinetic/end-point indicators | Firmness ↓ (20–30%), % weight loss, lycopene stability, visible defects | % weight loss, firmness retention, color stability, absence of pitting | % weight loss, firmness decline, retention of ascorbic acid & carotenoids, visual shrivel index | [34,35,36] |

| Cuticle & epidermis | Moderately thick cuticle; prone to micro-cracking under RH fluctuations | Thin epidermis with stomata; waxy but permeable; high transpiration | Thick pericarp with robust cuticle; permeability modulated by light & cultivar | [37,38,39] |

| Anatomical/structural factors affecting storability | Locular gel tissue promotes softening when cell walls weaken | High surface-to-volume ratio; limited barrier to water loss | Multi-layered pericarp confers mechanical strength & ↓ desiccation | [39,40,41] |

| Typical storage T threshold | 10–12 °C (below: chilling injury) | 10–12 °C (high sensitivity to chilling) | 7–10 °C (moderate chilling sensitivity) | [21,31,42] |

| Indicative nutritional highlights (per 100 g FW) | Ascorbic acid 20–40 mg; lycopene 3–10 mg | Ascorbic acid 10–15 mg; low carotenoids | Ascorbic acid 80–150 mg; carotenoids 2–6 mg | [20,23,43] |

| Overall postharvest resilience | Moderate; manageable with careful ripeness & RH control | Low; highly perishable even under optimal storage | Relatively high; strong tissues but sensitive to low T | [21,44,45] |

2.2. Shelf Life: Operational Definition, Kinetic Endpoints, and Disorder Metrics

Shelf life represents the duration during which harvested produce maintains acceptable commercial, nutritional, and sensory attributes [46]. It is driven by the postharvest environment and the physiological state of the product at harvest [46]. Operationally, shelf life is assessed through kinetic endpoints such as weight loss, firmness decline, color change, decay incidence, or quality degradation beyond a defined threshold of marketability [47,48].

In tomato, shelf life is governed by the rate of softening and the evolution of color and flavor, processes closely linked to ethylene production and respiration (Table 1) [28,33,40]. Firmness loss reflects underlying cell-wall disassembly processes, while excessive transpiration accelerates wrinkling and decay [40]. The onset of physiological disorders (e.g., blotchy ripening or postharvest cracking) is often traced back to preharvest imbalances in temperature, RH, or Ca nutrition [7,18,49]. Definitions of all physiological disorders treated in this review are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Quantitative metrics include the time required to reach a 20–30% firmness reduction, percentage weight loss, lycopene and acidity stability, and the incidence of visible defects [33,50].

Cucumber fruit exhibits one of the shortest shelf lives among greenhouse vegetables due to its high WC and delicate epidermis (Table 1) [21,32]. Postharvest deterioration is characterized by rapid loss of turgor, yellowing of the peel, and the appearance of chilling injury symptoms when stored below 10–12 °C [21,33,35]. Surface stomata further promote transpiration and infection under high RH [38,41]. Shelf life evaluation in cucumber therefore emphasizes water loss rate, firmness retention, color stability, and the absence of pitting or decay [35,41]. The influence of preharvest environment is particularly evident through its effects on cuticle formation, fruit epidermal strength, and stomatal density [2,38,41].

In sweet pepper, shelf life is determined by firmness retention, color stability, and the development of shriveling or decay (Table 1) [31,34]. Water loss is the principal cause of quality decline, while chilling injury may occur when storage temperatures drop below 7 °C [31,34,45]. Fruits that develop under optimal light and Ca nutrition tend to have thicker pericarp walls and stronger cuticular barriers, which slow postharvest softening and desiccation [8,39]. Kinetic indicators commonly include weight loss percentage, firmness decline, visual scoring for shriveling, and retention of ascorbic acid and carotenoids over storage time [34]. These metrics provide an integrated view of both physical and biochemical stability.

2.3. Crop Biology Relevant to Postharvest Behavior

The biological characteristics of each crop largely explain their contrasting responses to preharvest and postharvest environments.

Tomato is a climacteric fruit that exhibits a pronounced respiratory and ethylene peak during ripening (Table 1) [28], allowing ripening to continue after harvest. Harvest maturity therefore strongly influences postharvest performance. Its relatively thick cuticle provides moderate protection against dehydration, although susceptibility to cracking and physiological disorders such as blossom-end rot (BER) remains high under fluctuating RH or Ca deficiency [18,37]. The internal gel-rich locular tissue further accelerates softening when cell wall integrity declines [40].

Cucumber is non-climacteric, and its quality is largely fixed at harvest (Table 1) [27,29]. The fruit epidermis is thin and partially covered by stomata, resulting in high transpirational water loss and extreme sensitivity to low-temperature injury [38,41]. The cuticular layer is smooth and waxy but not sufficiently thick to prevent rapid desiccation under low RH [38]. Because cucumber fruits continue to respire intensely, even small imbalances in temperature or RH accelerate senescence, color loss, and microbial decay.

Sweet pepper, although non-climacteric, undergoes marked biochemical transformations during ripening, including the degradation of chlorophyll and the accumulation of carotenoids and ascorbic acid (Table 1) [6,25]. The fruit wall is composed of a thick pericarp that contributes to firmness and water retention [8,39]. The cuticle is relatively well developed, but its permeability can be influenced by light exposure, cultivar, and nutrient regime during cultivation [39,51]. Postharvest longevity therefore depends heavily on the pericarp and the mechanical or physiological stress encountered during growth and harvest [2,7,8].

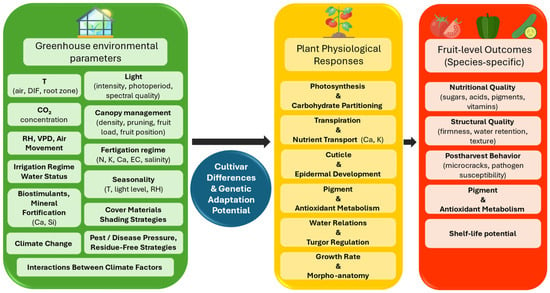

Understanding these biological principles is essential for interpreting species-specific responses and for contextualizing the pathways summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating the cascade from greenhouse environmental parameters to physiological processes and fruit-level outcomes determining quality and shelf life. Ca, calcium; CO2, carbon dioxide; DIF, day–night temperature difference; EC, electrical conductivity; K, potassium; N, nitrogen; RH, relative air humidity; Si, silicon; T, temperature; VPD, vapor pressure deficit.

3. Environmental Factors During Greenhouse Cultivation

3.1. Air Temperature

Temperature is one of the most influential factors determining fruit quality and shelf life in greenhouse vegetables [2,11]. It controls development and metabolism. The optimal thermal window for quality is narrower than for growth. Even moderate deviations affect nutritional and structural traits [2,45,52].

In tomato, optimal fruit-development temperatures are 18–24 °C, with day temperatures ~25 °C and night temperatures ~17 °C [53,54]. When means exceed 28–30 °C, lycopene synthesis declines and fruit shows orange coloration from β-carotene accumulation (Table 2) [55,56,57]. Elevated night temperatures accelerate respiration, reduce acidity, and promote softening, shortening shelf life [56,58,59]. Low night temperatures delay ripening and increase blotchy coloration [7,60]. The day–night temperature difference (DIF) is important. A positive DIF improves color development and firmness, whereas small or negative DIFs, common in poorly ventilated summer greenhouses, produce softer fruit with reduced soluble solids [57,58]. Maintaining temperature uniformity within the canopy is essential, as canopy gradients cause uneven ripening and inconsistent quality.

Table 2.

Effects of environmental factors during greenhouse cultivation on major quality traits and shelf life (SL) in tomato. B, blue (spectra); BER, blossom-end rot; C, carbon; Ca, calcium; CO2, carbon dioxide; DIF, day–night temperature difference; DLI, daily light integral; DM, dry matter; EC, electrical conductivity of the nutrient solution; IPM, integrated pest management; K, potassium; N, nitrogen; R, red (spectra); RH, relative air humidity; Si, silicon; T, temperature; TSS, total soluble solids; VPD, vapor pressure deficit; °Brix, soluble solids content. Arrows indicate direction of projected change (↑ increase, ↓ decrease). Definitions of physiological disorders are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Cucumber requires a warmer thermal environment than tomato for sustained growth, with optimal fruit-setting temperatures ~25–28 °C during the day and 18–20 °C at night [98,99]. High mean temperatures accelerate fruit enlargement but can reduce firmness and increase curvature, especially under high RH (Table 3) [99,100]. Excessive heat impairs chlorophyll retention, producing paler fruit [95,100,101]. Night temperatures below 15 °C slow growth and induce irregular shape and weak epidermal development [99,102]. Large DIF amplitudes favor elongation and epidermal reinforcement, whereas small DIFs promote soft texture and greater postharvest water loss [99,103]. The thin pericarp makes cucumber highly sensitive to short heat or chilling episodes during expansion, later expressed as accelerated yellowing or loss of glossiness after harvest [100,104,105].

Table 3.

Effects of environmental factors during greenhouse cultivation on major quality traits and shelf life (SL) in cucumber. B, blue (spectra); Ca, calcium; CO2, carbon dioxide; DIF, day–night temperature difference; DM, dry matter; EC, electrical conductivity of the nutrient solution; IPM, integrated pest management; K, potassium; N, nitrogen; RH, relative air humidity; Si, silicon; T, temperature; UV-A, ultraviolet A radiation; VPD, vapor pressure deficit. Arrows indicate direction of projected change (↑ increase, ↓ decrease). Definitions of physiological disorders are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Sweet pepper exhibits a slightly higher optimal temperature range than tomato, with 24–28 °C during the day and 18–20 °C at night promoting yield and pigment accumulation [95,141]. At moderate temperatures, ascorbic acid and carotenoid synthesis increase, enhancing nutritional quality and coloration (Table 4) [142,143]. However, prolonged temperatures above 32 °C cause flower abortion, sunscald, and irregular pigmentation, while sustained night temperatures above 22 °C promote softening and ascorbic acid loss [144,145,146,147]. When temperatures fall below 16 °C for extended periods, growth slows and fruit surface defects (e.g., microcracking) become more frequent [145,146]. A distinct diurnal rhythm, with sufficiently cool nights, improves tissue elasticity and supports thicker cuticle formation, contributing to extended shelf life [144,145,148].

Table 4.

Effects of environmental factors during greenhouse cultivation on major quality traits and shelf life (SL) in sweet pepper. ascorbic acid = vitamin C; B, blue (spectra); Ca, calcium; CO2, carbon dioxide; DIF, day–night temperature difference; DLI, daily light integral; EC, electrical conductivity of the nutrient solution; IPM, integrated pest management; K, potassium; N, nitrogen; R, red (spectra); RH, relative air humidity; Si, silicon; T, temperature; VPD, vapor pressure deficit. Arrows indicate direction of projected change (↑ increase, ↓ decrease). Definitions of physiological disorders are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Across species, moderate day temperatures with cooler nights (i.e., positive DIF) support firmer, better-colored fruit, whereas excessive heat or warm nights accelerate deterioration.

3.2. Root-Zone Temperature

Root-zone temperature (RZT) also affects fruit quality by controlling nutrient uptake, water absorption, and root-to-shoot hormonal signaling [180,181]. In hydroponic and substrate-based systems, RZT can be decoupled from the aerial climate, enabling targeted manipulation to improve nutritional quality and stress tolerance.

In tomato, root zones maintained between 18 and 22 °C are generally considered optimal for root activity and nutrient absorption [182,183]. RZT below 15 °C limits water uptake and promotes Ca-related disorders (e.g., BER) [182,184]. Conversely, RZT above 25 °C favors vegetative over reproductive growth and reduces color and °Brix [185,186,187]. Seasonal RZT control (i.e., heating in cool periods and moderate cooling during heat) stabilizes nutrient flow, enhances lycopene and °Brix, and reduces blotchy ripening [188,189].

Cucumber roots are highly sensitive to thermal fluctuations because of their shallow distribution and high transpiration demand [190,191]. Optimal RZT is ~22–25 °C, supporting steady growth and fruit firmness [190,191,192]. Cooling below 18 °C reduces water uptake, causing dull fruit appearance and slower growth, whereas RZT above 28 °C increases respiration and promotes watery texture [191,192,193]. Warm root zones can ease chilling stress, but chronic overheating accelerates senescence. Studies using localized root-zone heating or cooling show that stable temperatures near 24 °C improve epidermal development and delay yellowing, highlighting the importance of thermal homogeneity [192,194].

Sweet pepper tolerates a slightly broader RZT range, with optimum values between 20 and 25 °C [195,196,197]. Cooler root zones delay growth and limit K and Ca uptake, reducing pericarp firmness, whereas warmer conditions promote rapid fruit enlargement but may lower dry matter (DM) and ascorbic acid content [195,197,198]. Root-zone heating in winter improves fruit set and enhances color uniformity, yet sustained high RZT in summer increases susceptibility to soft rot and shortens shelf life [195,196,197]. Balanced root-zone thermal management thus supports nutrient supply, pericarp thickness, and improved storage performance.

Across all three crops, stable moderate RZT complements optimal air temperature to maintain nutritional and structural quality [162,180], highlighting the root zone’s central role in regulating growth, nutrition, and fruit integrity.

3.3. Light Intensity, Photoperiod, and Spectral Quality

Light drives photosynthesis and regulates development, metabolism, and morphology. In greenhouses, its intensity and duration (together expressed as the daily light integral, DLI), along with spectral quality, shape both yield and fruit quality [65,85]. Modern glazing, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and shading allow targeted control of these components to balance productivity and quality.

In tomato, moderate to high light integrals are associated with improved nutritional quality (Table 2) [59,64,199]. An increase in DLI enhances assimilate production, leading to higher soluble solids, sugars, and DM that support fruit flavor and firmness [61,63]. High irradiance also promotes lycopene and β-carotene accumulation through enhanced phytoene synthase activity and faster chloroplast-to-chromoplast conversion during ripening [55,64,86]. Conversely, light limitation caused by seasonal low radiation or excessive shading reduces pigment synthesis, lowers sugar-to-acid ratio, and produces pale, watery fruit [61,200]. Photoperiod effects are secondary, but extended daylength accelerates ripening and improves color uniformity [65,199]. Spectral composition further refines these responses: blue (B) light enhances ascorbic acid and phenolics, strengthens cuticle deposition, and improves firmness, whereas red (R) light boosts photosynthetic productivity and lycopene formation [64,201,202]. A balanced R–B ratio is widely regarded as optimal for both yield and quality. Far-red (FR) light influences plant morphology and assimilate partitioning by altering the R to FR ratio [203,204,205]. When FR is dominant, it can elongate stems and reduce fruit firmness, while moderate FR may enhance color development by facilitating chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition [202,204,205]. Ultraviolet-A (UV-A) exposure within safe limits may increase phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity, although excessive UV causes surface damage and shortens shelf life [96].

Cucumber shows a distinct light response due to its thin pericarp and high WC [38]. Adequate light intensity during fruit development is essential to maintain firmness and avoid overly elongated or pale fruits (Table 3) [109]. Under low DLI conditions, fruits tend to be larger yet less dense, with reduced mechanical strength and shorter shelf life [206,207]. In contrast, high light, particularly with moderate B or UV-A enrichment, promotes epidermal chlorophyll retention and increases phenolics, enhancing green color and delaying yellowing during storage [108,109]. Spectral manipulation further modulates epidermal traits. B light generally promotes thicker cuticle and stronger cell adhesion, whereas R-dominant light accelerates elongation and can result in thinner pericarps [208,209,210]. FR supplementation increases fruit length and overall yield but may reduce firmness [211]. Moderate UV induces defensive secondary metabolites, improving resistance to postharvest decay, while excessive UV causes surface scalding and accelerated chlorophyll degradation, highlighting the narrow window between beneficial and damaging light regimes [108,193].

In sweet pepper, light intensity and spectrum strongly influence pigmentation and antioxidant status (Table 4) [143,149]. High DLI enhances photosynthetic activity and supports ascorbic acid and carotenoid accumulation, key determinants of nutritional quality and visual appeal [212]. Insufficient light, as in winter in low-tech greenhouses, delays ripening and leads to dull coloration and reduced sugar content [143,149,151]. B light enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and phenolic synthesis, contributing to higher radical-scavenging capacity, while R light favors carotenoid biosynthesis, particularly capsanthin and capsorubin during the red-ripening phase [212,213]. Supplemental R + B lighting improves color saturation and nutritional value compared with natural light alone [213,214]. FR radiation accelerates color transition but may cause softening when overapplied, whereas UV-A can boost phenolic and flavonoid concentrations without detrimental effects when carefully controlled [153,212]. The photoperiod effect is minor but can influence ascorbic acid retention by modulating the daily duration of photosynthetic activity [215].

Across all three crops, light intensity has a stronger influence on nutritional composition than on shelf life, though both are linked. High DLI improves DM and firmness via greater assimilate supply, while B and UV-A light enhance antioxidant metabolism and slow deterioration. By contrast, low or imbalanced light produces softer, poorly pigmented fruits with reduced storability. Integrated management of DLI, R−B balance, and limited FR or UV-A exposure yields produce with high nutritional value and improved postharvest stability.

3.4. CO2 Enrichment

CO2 enrichment is widely used in greenhouses to enhance photosynthesis and yield, but it also influences fruit composition, firmness, and postharvest behavior [114,216,217]. Its effects depend on CO2 concentration and exposure duration, as well as interacting factors such as light, temperature, RH, and species-specific physiology.

In tomato, CO2 enrichment from ~400 to 700–1000 µmol mol−1 enhances photosynthesis and increases carbohydrate availability for fruit growth [59,66]. Elevated CO2 generally raises soluble solids, sugars, and DM, improving flavor and density (Table 2) [59,62,66]. This effect reflects greater source strength and enhanced assimilate translocation to the fruits [59]. Several greenhouse studies report improved firmness and slower softening under moderate enrichment due to better cell wall integrity and reduced respiration rate at harvest [58,62,114]. At the biochemical level, CO2 enrichment may dilute organic acids, raising the sugar-to-acid ratio and altering flavor balance. Lycopene and β-carotene are typically maintained or modestly increased under adequate light, whereas excessive CO2 under high temperature or low radiation can limit pigment synthesis via feedback constraints on carbon (C) metabolism [59,62,66]. Ascorbic acid levels sometimes decline under high CO2, possibly due to lower oxidative stress and reduced need for antioxidant synthesis, although this response is inconsistent across cultivars [62,67]. Overall, elevated CO2 combined with sufficient light and balanced nutrition produces firmer, well-colored tomatoes with improved shelf life.

Cucumber shows a pronounced yield response to CO2 enrichment, reflecting its high photosynthetic demand and rapid fruit growth rate [218,219]. Concentrations of ~800–1000 µmol mol−1 increase fruit number and size, while maintaining or slightly improving firmness and DM (Table 3) [113]. Enhanced C assimilation accelerates cell expansion and cuticle formation, contributing to smoother, more uniform surfaces. However, when CO2 enrichment occurs under high RH or low light, the rapid enlargement may lead to watery tissue and thinner epidermis, reducing postharvest firmness and increasing decay susceptibility [112,113,220]. Studies indicate that moderate CO2 levels with adequate light and ventilation improve epidermal structure, lower transpiration rates, and reduce postharvest water loss. Effects on antioxidant compounds (e.g., ascorbic acid and phenolics) are variable, but can show mild increases when CO2 enrichment is paired with moderate light and balanced nutrition [112,221]. Under excessive enrichment or poor ventilation, internal CO2 buildup may alter pH and accelerate yellowing, emphasizing the need for tight control [218,222].

In sweet pepper, CO2 enrichment supports both productivity and nutritional quality [156,157]. Increased C availability boosts carbohydrate concentration and stimulates ascorbic acid and carotenoids, especially under strong light and moderate temperature (Table 4) [155,156]. Fruits grown under elevated CO2 typically exhibit thicker pericarp, higher DM, and improved firmness, traits associated with longer shelf life [151,155]. The mechanism involves more efficient photosynthesis and greater assimilate allocation to fruit tissues, enhancing cell wall deposition and turgor. However, as in tomato, excessive enrichment without sufficient light can cause carbohydrate dilution and lower pigment accumulation [59,223]. Postharvest responses are generally positive: lower respiration, delayed softening, and reduced water loss have been observed in CO2-enriched fruits [154,224]. Moreover, higher ascorbic acid levels increase antioxidant capacity, slowing oxidative degradation during storage [151,156].

Across all three crops, CO2 enrichment at 700–1000 µmol mol−1 under adequate light and ventilation improves nutritional and structural quality, increasing sugars, firmness, and sometimes antioxidants to extend shelf life. Responses, however, depend on conditions: under low light or high RH, yield gains may be accompanied by poorer tissue quality. Thus, effective CO2 management must be integrated with light and temperature control to ensure both high productivity and strong postharvest performance.

3.5. Relative Air Humidity, Vapor Pressure Deficit, and Air Movement

Greenhouse humidity, expressed as RH or its functional equivalent, the vapor pressure deficit (VPD), strongly regulates transpiration, nutrient transport, and fruit surface development, thereby shaping both growth and postharvest quality. Because RH control depends on ventilation and heating, it is difficult to manage and directly affects nutritional composition, firmness, and shelf life [225,226].

In tomato, moderate VPD levels (~0.5–1.0 kPa) promote balanced transpiration and adequate Ca transport to developing fruits (Table 2) [68,70,71]. Under such conditions, normal cuticle formation supports firm fruit with low susceptibility to cracking or BER. When RH is excessively high (above 85–90%), transpiration declines, Ca distribution becomes uneven, and the cuticle softens, increasing susceptibility to microcracks and pathogen infection [69,227]. High RH also suppresses the synthesis of structural epidermal waxes, producing a thinner and more permeable surface that accelerates postharvest water loss [116,227]. In contrast, very low RH (high VPD > 1.2–1.5 kPa) increases transpiration and mechanical stress, resulting in smaller fruits, tougher skin, and sometimes reduced sugar accumulation [70,71]. Moderate air circulation enhances boundary-layer exchange, stabilizes transpiration, and prevents condensation, which otherwise encourages fungal decay. Greenhouse studies consistently show that maintaining moderate VPD and gentle airflow results in thicker cuticles, firmer texture, and improved shelf life without compromising yield [69,71,227].

Cucumber responds more acutely to RH fluctuations because of its high transpiration rate and thin epidermis [115,228]. High RH during fruit expansion produces glossy, tender fruits with fragile epidermal layers prone to postharvest shrinkage and decay (Table 3) [117,118]. Under persistently humid conditions, Ca and boron transport to the fruit surface declines, weakening cell adhesion and promoting cuticle microfissures [228,229]. These defects subsequently manifest as accelerated yellowing and water loss during storage. Conversely, very low RH (<60%) increases transpiration beyond the plant’s hydraulic capacity, leading to localized wilting and roughened skin [220,230]. Greenhouse experiments demonstrate that maintaining VPD ~0.8–1.0 kPa ensures adequate water transport without compromising epidermal integrity [231,232]. Active airflow mitigates condensation on fruit surfaces, reduces microbial colonization, and improves uniform cooling at night, collectively contributing to extended shelf life. Some studies also link slightly higher VPD with elevated concentrations of soluble solids and phenolics, indicating that mild evaporative demand may stimulate secondary metabolism and improve nutritional quality when properly managed [120,233].

Sweet pepper shows greater tolerance to high RH compared with tomato and cucumber, yet it remains sensitive to prolonged saturated conditions [159,160]. When RH exceeds 90%, pollen viability declines, Ca transport becomes irregular, and the resulting fruits often exhibit softer pericarps and reduced firmness (Table 4) [159,160,161]. High RH also favors cuticle disorder, producing wrinkled or dull surfaces [160,234]. Conversely, very low RH increases transpiration and can cause microcracks at the fruit shoulder, leading to higher postharvest water loss. Maintaining intermediate VPD (~0.7–1.0 kPa) supports pericarp strength and uniform cuticular deposition, enhancing firmness and water-retention capacity [160,235]. Studies in greenhouse environments show that peppers grown under moderate VPD accumulate more soluble solids and ascorbic acid compared with those under extreme dryness or excessive RH [160,236]. Gentle but continuous air movement reduces local RH pockets in dense canopies, improves leaf cooling, and limits fungal contamination on fruit surfaces, thereby extending shelf life.

RH and VPD influence postharvest behavior mainly by regulating water relations and Ca distribution. High RH produces smooth but weak fruit, while moderate evaporative demand promotes denser tissues and thicker cuticles. With adequate air movement, moderate VPD and proper nutrition together support high nutritional quality and storage stability across all three crops.

3.6. Irrigation Regime and Water Status

Water management strongly influences crop physiology and the traits that determine postharvest longevity. Irrigation governs hydration, assimilate allocation, and nutrient transport, allowing precise control of yield and quality [237,238]. Regulated deficit irrigation (RDI), which applies mild, stage-specific water limitation, is increasingly used to enhance fruit nutritional density without causing lasting stress [238,239].

In tomato, greenhouse studies show that moderate irrigation reductions during fruit expansion or ripening increase soluble solids, sugars, organic acids, and DM, yielding fruit with improved flavor and a higher sugar-to-acid ratio (Table 2) [72,74]. The underlying mechanism reflects lower fruit WC and stimulated osmolyte and sugar synthesis under mild water deficit [74,238]. Phenolics and ascorbic acid often rise, indicating enhanced antioxidant metabolism [12]. However, when water deficit is too severe or imposed early, it restricts Ca transport and cell expansion, producing smaller fruit, softening, and higher BER susceptibility [240,241]. Thus, proper timing and intensity are critical: moderate RDI late in the cycle improves quality, whereas prolonged or erratic deficits compromise yield and shelf life. Overirrigation, in contrast, promotes vegetative growth, dilutes soluble solids, and leads to watery, fragile fruits that deteriorate rapidly after harvest [59,75]. Slight root-zone tension produces firmer fruit with thicker cuticle and reduced postharvest water loss [72,242].

Cucumber is particularly sensitive to fluctuations in water availability because of its high transpiration rate and limited osmotic buffering (Table 3) [38,95]. Consistent moisture is required to maintain steady fruit enlargement and epidermal turgor. Even short-term deficits result in curvature, reduced size, and roughened surface texture [120]. Severe water limitation causes pitting, dull coloration, and accelerated yellowing [243,244]. Nonetheless, mild deficit regimes (~10–20% irrigation reduction) can modestly increase DM and firmness without yield loss, provided that RH and nutrients remain favorable [119,120]. These slight restrictions enhance cuticle deposition and reduce internal voids, improving water retention [119]. Overirrigation, by contrast, produces fruits with high WC and low structural density, prone to rapid softening and decay [119,120,121]. Thus, while cucumber benefits less from RDI than tomato, maintaining near-saturated but uniform moisture remains essential for firm, durable fruits.

In sweet pepper, controlled irrigation deficits can enhance nutritional and sensory quality when properly timed (Table 4) [162,165]. Moderate reductions in irrigation during maturation elevate soluble solids, ascorbic acid, and phenolics, indicating activation of antioxidant pathways [162,164,165]. Mild water stress enhances assimilate partitioning to the fruits and can increase pericarp thickness, improving firmness and reducing postharvest water loss [162,165,245]. However, strong or prolonged deficits impair Ca transport, leading to soft pericarps and BER–like symptoms, particularly under high evaporative demand [151,164,165]. Overirrigation dilutes sugars and acids, producing bland-tasting fruits with thin walls and short shelf life [163,164]. Thus, optimal irrigation maintains near field-capacity moisture during flowering and fruit set, followed by moderate deficits during ripening.

Across the three species, balancing adequate water with mild stress is essential for maintaining yield and postharvest quality. Well-timed RDI enhances soluble solids, antioxidants, and firmness, while excessive deficits or overirrigation weaken structure and reduce storability. Sensor-based irrigation that maintains slight root-zone tension offers the most consistent quality and water-use efficiency [239,246].

3.7. Fertigation: Nitrogen, Potassium, Calcium, Electrical Conductivity, and Moderate Salinity

Nutrient management via fertigation strongly influences fruit composition and postharvest stability. The supply of nitrogen (N), K, Ca, and the electrical conductivity (EC) of the solution determine the balance between vegetative growth and quality [200,247]. Moderate salinity can enhance flavor, firmness, and antioxidants, whereas excessive or unbalanced fertilization leads to nutrient disorders and reduced storability.

In tomato, the interplay between N and K is central to fruit quality (Table 2) [80]. High N availability promotes vigorous vegetative growth and large fruit size but dilutes soluble solids and acids, producing fruit of inferior flavor and texture [248,249]. Conversely, moderate N reduction near ripening concentrates sugars and improves the sugar-to-acid ratio [249,250]. K enhances sweetness, color, and firmness by facilitating carbohydrate translocation and activating carotenoid and organic acid enzymes [76]. High K supply increases lycopene content and TA, while improving tissue strength through osmotic regulation [76,251]. Ca stabilizes cell walls and membranes [252], and adequate Ca transport during fruit development is essential to prevent BER and maintain firmness [253]. Ca-deficient fruits show localized tissue collapse and reduced shelf life due to weakened pectin cross-linking [18]. Optimal EC generally ranges from 2.5 to 4.0 dS m−1 [254], within which moderate salinity acts as a beneficial stress, reducing water uptake and increasing DM, sugars, acids, and phenolics [255,256]. When EC exceeds ~5 dS m−1, yield losses and physiological disorders outweigh quality gains [256,257]. Greenhouse trials show that controlled salinity and balanced K/Ca ratios produce tomatoes with higher °Brix, stronger pericarp, and longer shelf life [59,258].

Cucumber responds differently to nutrient concentration because of its high water demand and osmotic sensitivity. High N promotes rapid growth and large fruits but results in excessive WC and soft texture, with diluted sugars and reduced firmness [259]. Slight N reduction can increase DM and firmness without yield loss when K and Ca are sufficient [122,123]. K enhances color intensity and firmness, while maintaining turgor [260,261]. Ca supplementation strengthens the epidermis and cuticle, improving resistance to postharvest water loss [262]. Optimal EC for cucumber fertigation is ~2.0–2.5 dS m−1 [263,264]. Moderate salinity within this range can enhance structural density and reduce decay incidence, but higher salinity (>3.5 dS m−1) impairs water uptake, induces bitterness through cucurbitacin accumulation, and shortens shelf life [265,266]. Nitrate balance also affects fruit quality, as excess nitrate favors rapid elongation but produces pale, watery tissue [267,268]. Thus, fertigation regimes emphasizing K and Ca relative to N are essential for yield and postharvest resilience.

Sweet pepper responds strongly to nutrient balance, particularly to K and Ca availability. K enhances fruit firmness, color development, and ascorbic acid/carotenoid synthesis, while Ca ensures mechanical strength and limits softening [269,270]. High N during fruit development encourages vegetative growth and delays ripening, producing fruit with lower sugar and vitamin content [167,271]. Lowering N and increasing the K/N ratio near maturity often improves flavor and nutritional quality. Ca deficiency causes localized tissue collapse at the blossom end or pericarp, severely reducing marketability and storage life [159,272]. Maintaining adequate Ca in the nutrient solution and avoiding excessive RH that restricts transpiration are key to consistent uptake. The ideal EC for pepper fertigation is ~2.0–3.0 dS m−1 [273]. Moderate salinity enhances ascorbic acid and DM, whereas excessive salt stress reduces fruit size and firmness [274]. Balanced K– and Ca-rich fertigation under moderate EC produces fruit of higher nutritional density and improved keeping quality.

Optimal fertigation balances N, K, Ca, and moderate EC to impose mild, beneficial stress that boosts soluble solids, pigments, and antioxidants, producing firmer, denser fruit with better shelf life. Excessive N or low EC leads to dilute, soft fruit, while moderate salinity strengthens tissues and reduces postharvest water loss.

3.8. Canopy Management: Density, Pruning, Fruit Load, and Fruit Position

Canopy structure and management strongly influence fruit nutritional quality and postharvest performance. Plant density, pruning, and fruit load regulate light distribution, source–sink balance, and microclimate, thereby affecting assimilate supply and fruit maturation. Fruit position within the canopy further alters light and temperature exposure, contributing to variability in composition and shelf life.

In tomato, plant density and pruning strongly affect light interception and assimilate partitioning. High planting densities increase overall yield per unit area but reduce light penetration and elevate RH, producing softer fruits with lower soluble solids and greater decay susceptibility [275,276]. Reduced light also limits lycopene accumulation, leading to paler fruit and lower nutritional value [64,277]. Moderate plant density combined with systematic pruning maintains an open canopy, improves airflow, and supports uniform fruit development. Pruning to a single or double stem promotes efficient source–sink balance, yielding larger, sweeter, and firmer fruits [278,279]. Over-pruning can limit photosynthesis, leading to unbalanced ripening and lower antioxidant content [280,281]. Fruit load management is also critical. Excessive fruiting dilutes assimilates per fruit, lowering sugar and acid content, while moderate load improves compositional density and firmness [64,282]. The order of fruit within the truss affects quality. Basal fruits, which develop earlier and under stronger assimilate competition, often reach larger size but show lower DM and shorter shelf life than distal fruits [283,284]. Maintaining uniform cluster load and regular removal of side shoots helps standardize fruit quality across harvests.

Cucumber production relies on continuous fruiting along indeterminate vines, making canopy management essential for balancing vegetative vigor with fruit quality. High plant densities promote mutual shading and reduce airflow, leading to elongated, less firm fruits with thinner epidermis [24,285]. Lower densities improve light penetration and photosynthetic efficiency, producing firmer fruits with more uniform color [285,286]. Pruning mainly involves removing lateral shoots and old leaves to keep light reaching developing fruits. Excess foliage increases RH and disease incidence, thereby reducing shelf life [287,288]. Fruit load regulation is crucial because each fruit is a dominant sink. Allowing too many fruits reduces individual growth rate and firmness, whereas moderate load increases DM and structural integrity [289,290]. Fruit position also affects quality. Basal fruits often have thicker cuticle and higher firmness but may show curvature, whereas upper-node fruits, exposed to higher irradiance, retain better color and postharvest appearance [285,290]. Maintaining a steady harvest rhythm through consistent pruning and leaf renewal helps stabilize quality across harvests.

Sweet pepper, characterized by a more compact canopy, is sensitive to plant spacing and load management. Dense planting reduces airflow and light availability to lower leaves and fruits, resulting in thin-walled peppers with lower ascorbic acid and carotenoid contents [291,292]. Wider spacing improves light penetration and promotes thicker pericarp and higher pigment levels, though very low density can reduce yield [170,293]. Moderate pruning to remove shaded or senescent leaves improves microclimate and limits condensation-related disorders. Fruit load regulation strongly affects nutritional quality and shelf life. High load increases assimilate competition and delays ripening, producing fruits with lower sugars and vitamins, whereas moderate thinning enhances sweetness, firmness, and color uniformity [294,295]. Fruit position also creates compositional gradients. Upper-canopy fruits exposed to stronger irradiance accumulate more ascorbic acid and carotenoids but are more prone to sunscald, whereas inner-canopy fruits have paler color and softer texture but retain water better during storage [149,153]. A balanced canopy that provides partial shading under high light optimizes both quality and longevity.

Canopy management links greenhouse conditions to fruit physiology. Optimal plant density, pruning, and fruit load ensure uniform light and microclimate, enhancing sugars, acids, antioxidants, and firmness. Poorly structured canopies create uneven light and RH, causing variable ripening and inconsistent postharvest quality. Positional effects highlight the need for uniform exposure and balanced load. Thus, optimizing canopy structure is essential not only for yield but also for nutritional value and shelf life.

3.9. Seasonality: Temperature, Light Level, and Relative Air Humidity

Seasonal shifts in temperature, light, and RH strongly affect greenhouse vegetable quality. Cool, low-light periods slow growth and sugar/pigment formation but produce firmer, longer-lasting fruit, whereas summer heat and high radiation accelerate ripening, improving color and sweetness but reducing firmness and shelf life. RH further modulates these outcomes via transpiration and Ca mobility.

Tomato responds strongly to seasonal changes in temperature, light and RH. Under winter conditions (i.e., low radiation and moderate to high RH), ripening proceeds slowly, producing fruits with lower soluble solids, reduced lycopene, and higher acidity [64,282]. Such fruits retain greater firmness and storability due to slower respiration and cell-wall degradation. In contrast, summer conditions (i.e., high radiation and fruit temperatures > 30 °C) accelerate sugar and pigment accumulation but reduce firmness and shelf life [56,296]. RH fluctuations further modify these outcomes. High RH during cool periods impedes Ca transport and predisposes fruits to cracking, while low RH in hot months increases water loss and cuticular stress [242,297]. The magnitude of these seasonal contrasts depends on greenhouse technology level. Low-technology structures track ambient conditions, producing firm but pale fruits in winter and brightly colored yet short-lived fruits in summer [298,299,300]. Medium-technology greenhouses with partial heating and shading moderate these differences, while high-technology systems with full climate control largely eliminate them [298,301,302]. Across all systems, fruit temperature, driven by radiation load, remains the primary factor explaining seasonal differences in nutritional composition and shelf life.

Cucumber exhibits pronounced seasonal sensitivity because of its thin epidermis and high WC. During the cool season, low radiation and temperature slow growth, producing smaller but denser fruits with darker green color, higher firmness, and improved water retention [289,303]. These fruits store longer but contain lower soluble solids. In summer, abundant radiation and high air temperature accelerate fruit elongation, producing larger, lighter-colored fruits with higher initial sweetness but faster postharvest softening and yellowing [105,304]. Seasonal changes in RH strongly influence epidermal integrity. High RH during winter promotes smooth skin but favors decay after harvest, whereas the lower RH of hot periods enhances firmness but may cause surface roughness [104,305]. In low-technology greenhouses, these patterns are amplified, leading to greater variability in fruit firmness and shape [95,306]. Medium-technology systems reduce this variability through better ventilation and shading, while high-technology facilities maintain stable conditions that largely eliminate seasonal contrasts [307,308]. As with tomato, radiation-driven fruit temperature remains the dominant factor determining seasonal variation, controlling both firmness development and water-loss rate during storage.

In sweet pepper, seasonality governs both pigment biosynthesis and postharvest behavior. Winter fruits under low radiation accumulate less ascorbic acid and carotenoids but maintain high firmness and thick pericarps, supporting superior shelf life [142,146,309]. Summer fruits ripen rapidly under intense radiation and high temperature, achieving vivid coloration and elevated antioxidant content but undergo faster softening and higher water loss after harvest [142,310]. Seasonal RH differences compound these effects. High RH in cool months favors smooth surface texture but restricts Ca transport, whereas drier summer air increases transpirational stress and microcracking risk [116,160]. In low-technology greenhouses, summer fruits are visually attractive but short-lived, while winter fruits are mechanically strong yet less colorful [95,166]. Medium-technology systems with adjustable shading and ventilation improve microclimate stability and reduce heterogeneity in fruit size and maturity [95,311]. High-technology environments with automated temperature and RH regulation produce more uniform fruits throughout the year, minimizing seasonal variability [307,312]. For sweet pepper, as for tomato and cucumber, the primary determinant of seasonal quality differences is fruit-surface temperature, which integrates the effects of radiation intensity and RH on metabolic and structural processes.

Across all three crops, seasonal variation in quality is driven mainly by radiation load and the resulting fruit temperature, which regulate pigment and sugar formation as well as respiration, softening, and water loss. RH plays a secondary role. Seasonal contrasts are strongest in low-technology greenhouses, reduced in medium-technology systems, and minimal in high-technology facilities with stable climate control. Maintaining steady fruit temperature through shading, ventilation, and heating is key to achieving uniform year-round quality.

3.10. Cover Materials and Shading Strategies

Greenhouse cover properties control light transmission and internal temperature, strongly shaping fruit microclimate and quality. Shading reduces excess radiation in hot regions, while high transmission is essential in low-light periods to sustain pigment and sugar formation. The impact of these strategies varies with crop species, canopy structure, and greenhouse technology level.

Tomato benefits from cover materials that balance radiation transmission and heat control. Transparent polyethylene (PE) films with high light transmittance enhance photosynthesis in winter but can cause summer overheating [83,313]. Excessive radiation and fruit surface temperature above 30 °C reduce lycopene accumulation and increase softening, shortening shelf life [314,315]. The use of diffusive films, which scatter light without major loss of transmission, improves canopy light uniformity and reduces localized overheating [83,316]. Fruits under diffusive covers show higher lycopene and β-carotene, better color uniformity, and lower cracking incidence [317]. In high-radiation seasons, movable shading screens or reflective nets reduce fruit temperature and prevent sunscald while maintaining adequate photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) [300,318]. Studies show that moderate shading (~20–30%) preserves firmness and reduces postharvest decay without significantly decreasing soluble solids [87,300]. In low-radiation seasons, retracting shading materials or using high-transmission films enhances light interception and compensates for low DLI [83,319]. Thus, dynamic shading systems combining diffusive covers and adjustable screens provide the best balance of color development, firmness, and storability in greenhouse tomato.

Cucumber is particularly sensitive to high radiation and temperature due to its tender epidermis and rapid water loss. Cover materials that moderate radiation load and temperature are therefore critical to maintaining postharvest quality [127,320]. In low-tech structures, non-diffusive transparent films often permit excessive solar gain, resulting in elevated fruit temperature, curvature, and reduced firmness [304,321]. The adoption of diffusive PE films or white shading nets during summer lowers internal radiation by 20–40%, reducing heat stress and fruit yellowing [322,323]. Under diffusive light, canopy photosynthesis becomes more homogeneous, and fruits develop smoother surfaces with stronger cuticle integrity. However, excessive shading (>50%) reduces assimilate supply, leading to soft, watery fruits and diminished sugar content [322,324]. In winter, high-transmission films improve light penetration, maintaining green color retention [325,326]. The introduction of anti-drip coatings further enhances quality by preventing condensation, which otherwise promotes fungal infection and uneven epidermal development [327,328]. Overall, optimal cucumber management combines moderate diffusive shading in high-radiation periods with high-transmission films in low-radiation periods, ensuring balanced temperature control and consistent firmness.

Sweet pepper production benefits from controlled light diffusion and thermal moderation to prevent sunscald while maintaining pigment formation. In summer, direct radiation on exposed fruits can raise surface temperature above 40 °C, leading to bleaching and tissue collapse [329,330]. Diffusive films and aluminized shading nets reduce direct light, improve radiation distribution, and lower canopy temperature, preventing such injuries [149,170,331]. Fruits grown under diffusive light display improved color uniformity and higher carotenoid and ascorbic acid concentrations, likely due to reduced photooxidative stress and more uniform energy distribution within the canopy [149]. Moderate shading preserves firmness and limits water loss, extending shelf life, whereas heavy shading reduces sugar and pigment accumulation, producing dull-colored fruits with lower nutritional value. During winter, transparent or anti-reflective covers maximize radiation input, maintaining photosynthesis and promoting pigment synthesis [95,332]. Dynamic shading systems in mid- and high-technology greenhouses enable finer control of light intensity and reduce quality heterogeneity.

Across all three crops, effective optical management of covers and shading is essential for stabilizing microclimate, fruit composition, and shelf life. Diffusive films enhance light uniformity and lower fruit temperature, while moderate shading limits heat and oxidative stress during high-radiation periods. High-transmission covers in low-light seasons support assimilation and pigment formation, whereas excessive shading reduces sugars and carotenoids. Overall, the benefits of optimized optical materials stem from their ability to regulate fruit surface temperature, making adaptive shading and diffusion key components of climate-smart greenhouse design.

3.11. Biostimulants and Mineral Fortification

Beyond conventional fertilization, biostimulants and mineral fortifiers are increasingly used to improve fruit nutritional quality and postharvest resilience in greenhouse vegetables. Biostimulants (e.g., seaweed extracts, protein hydrolysates, humic substances, microbial inoculants, and chitosan) enhance nutrient uptake, modulate physiology and activate antioxidant defenses [333]. Mineral fortification with Ca or silicon (Si) strengthens cell walls and cuticular barriers, improving firmness and stress resistance. These inputs operate at the intersection of nutrition and stress physiology, complementing environmental control, although their effects vary among species.

In tomato, preharvest application of biostimulants and Ca fortification enhances nutritional and structural quality attributes [77,334]. Foliar or root applications of Ca salts increase membrane stability and reduce BER by improving Ca partitioning to the fruit [241,335]. Higher Ca concentrations in pericarp tissue correlate with slower softening and reduced postharvest decay [336,337]. Si supplementation strengthens epidermal tissues and improves tolerance to oxidative and thermal stress [338,339], resulting in firmer fruits and lower weight loss during storage. Biostimulants (e.g., chitosan, seaweed extracts, and amino-acid-based formulations) stimulate phenolic metabolism and elevate antioxidant capacity, increasing total phenolics, ascorbic acid, and lycopene [340]. Chitosan also forms a semi-permeable coating that reduces transpiration and respiration, thereby prolonging shelf life [341,342]. Studies show that biostimulants enhance antioxidant enzyme activity (superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase), delaying senescence and improving color stability during storage [343,344]. Thus, combining biostimulants with mineral fortification provides synergistic gains in nutritional density and mechanical resilience.

Cucumber responds markedly to Si and Ca supplementation, reflecting its high WC and thin cuticle [345,346]. Ca fortification during fruit development enhances epidermal strength and cohesion, reducing postharvest softening and surface collapse [299,347]. Adequate Ca supply also diminishes tipburn and localized pitting, disorders linked to uneven Ca distribution under fluctuating RH [348,349]. Si application improves resistance to biotic and abiotic stress by reinforcing the cuticular–cell wall complex and stimulating phenolic synthesis [135,350], producing firmer fruits with lower water loss and higher antioxidant capacity. Biostimulants (e.g., seaweed extracts and humic substances) promote root activity and improve mineral uptake, supporting turgor and chlorophyll maintenance [132,351]. Chitosan treatments delay postharvest yellowing by suppressing chlorophyll-degrading enzymes and enhancing antioxidant defense [352]. However, excessive or frequent biostimulant use can cause cuticular roughness or altered surface color, indicating the need for precise dosing. Overall, balanced Ca–Si nutrition combined with mild biostimulant use enhances both physical and biochemical stability of greenhouse-grown cucumber.

In sweet pepper, mineral fortification and biostimulant treatments strongly influence firmness, color development, and antioxidant status [353,354]. Ca supplementation, particularly during rapid fruit expansion, enhances pericarp thickness and firmness while preventing localized tissue collapse [269,272]. Adequate Ca also reduces physiological softening and postharvest decay. Si fortification increases cell-wall silicification and strengthens the antioxidant system, leading to higher ascorbic acid and carotenoid retention during storage [355]. Foliar Si sprays mitigate heat and light stress, resulting in brighter color and delayed senescence [355]. Biostimulants (e.g., seaweed extracts and protein hydrolysates) stimulate phenylpropanoid metabolism and ascorbic acid synthesis, enhancing nutritional quality [356,357]. Chitosan and microbial inoculants promote systemic resistance and reduce disease incidence, extending postharvest life [356,357,358]. Treated fruits typically display greater firmness, lower transpiration losses, and more uniform pigmentation [358]. These benefits are most evident in mid- and late-season crops under elevated radiation and temperature. Thus, integrating biostimulant and mineral treatments supports structural integrity and nutritional value under variable environmental conditions.

Across all three crops, biostimulants and mineral fortifiers improve fruit quality by enhancing physiological resilience rather than supplying nutrients. Ca strengthens membranes and cell walls, Si reinforces the epidermis and antioxidant systems, and biostimulants stimulate secondary metabolism. These actions increase firmness, antioxidant capacity, and shelf life, with best results under balanced fertigation and moderate stress. Combined Ca–Si fortification and periodic biostimulant use reliably improve structural integrity, nutritional value, and postharvest performance in greenhouse production.

3.12. Pest and Disease Pressure and Residue-Free Strategies Affecting Quality

Pest and disease management affects fruit quality both directly and indirectly. Pest pressure reduces photosynthesis, assimilate flow, and water balance, producing irregular fruits with weaker structure and altered composition. Conversely, excessive chemical control risks residue accumulation and may disrupt normal metabolism. Modern greenhouse production therefore relies on residue-free integrated pest management (IPM), combining biological control, natural elicitors, and cultural or physical measures to maintain plant health while supporting fruit quality and shelf life. The effectiveness of these strategies varies with species and their specific pest and pathogen sensitivities.

In tomato, pest and disease pressure affects fruit quality primarily through its influence on photosynthesis and vascular transport. Infestation by whiteflies, thrips, or spider mites reduces leaf assimilation area and induces stress responses that divert resources from fruit growth to defense [359,360]. Such stress often produces smaller fruits with elevated phenolic and flavonoid content [361]. While moderate biotic stress can enhance antioxidant capacity, severe or chronic infestation causes nutrient depletion and reduced firmness. Pathogenic infections (e.g., Botrytis cinerea or Cladosporium fulvum) reduce yield and accelerate postharvest decay by increasing fungal inoculum on the fruit surface [362,363]. Residue-free strategies based on biocontrol agents (e.g., Trichoderma harzianum, Bacillus subtilis) and elicitor compounds (e.g., chitosan, salicylic acid, seaweed extracts) strengthen plant defense and improve fruit biochemical profile [364,365]. Chitosan induces phenylpropanoid metabolism, enhancing phenolic and lycopene accumulation, while microbial biocontrol treatments stimulate systemic resistance [364,365]. These approaches reduce postharvest decay and maintain firmness by reinforcing cuticular and cell-wall structures. Thus, IPM-based, residue-free regimes often produce fruits with equal or superior nutritional quality compared with conventional chemical control while ensuring consumer safety.

Cucumber is highly susceptible to fungal and arthropod pests (e.g., powdery mildew, downy mildew, and whiteflies), which thrive under the humid greenhouse conditions [366,367]. Pest-induced stress decreases photosynthetic efficiency and disrupts water relations, producing irregular fruits with reduced firmness and shorter shelf life [368,369]. Infections by Pseudoperonospora cubensis or Sphaerotheca fuliginea also increase ethylene production, accelerating postharvest yellowing [370]. Residue-free management strategies using biological antagonists, essential oil formulations, and microbial inoculants help mitigate these effects [371,372]. Beneficial fungi and bacteria (e.g., Trichoderma spp. and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) colonize roots or leaves, inducing systemic resistance and improving nutrient uptake [373,374]. Treated plants often show higher antioxidant and phenolic levels, indicating that mild induced defense enhances nutritional quality [374,375]. Physical measures (e.g., insect-proof screens and the introduction of predatory mites) further reduce pests without residues [376,377], though excessive shading from dense netting can limit light penetration. Cucumbers produced under residue-free regimes are typically firmer, less prone to decay, and retain green color longer during storage, reflecting enhanced physiological robustness and lower pathogen load.

In sweet pepper, pest pressure from aphids, thrips, and whiteflies, along with diseases (e.g., Botrytis, Alternaria, and bacterial leaf spot), can substantially reduce quality through direct damage and altered metabolism [378]. Infested plants divert assimilates to defense, resulting in smaller fruits with uneven coloration and thinner pericarps. Chemical pesticide overuse can leave residues and interfere with carotenoid accumulation [379,380]. Residue-free strategies centered on biological control (e.g., releasing Encarsia formosa, Amblyseius swirskii, and Orius laevigatus) maintain pest populations below thresholds while preserving conditions favorable to fruit development [176,381]. Elicitor treatments, including chitosan and microbial consortia, induce defense enzymes and enhance ascorbic acid and carotenoid synthesis, improving nutritional and antioxidant profiles [382,383]. These fruits also show delayed softening and reduced postharvest decay. The absence of residues facilitates colonization by beneficial epiphytic microflora, which may contribute to natural protection during storage [384]. Overall, residue-free regimes improve firmness and visual appeal without compromising flavor or safety, meeting consumer expectations for residue-free produce.

Across all three crops, pest and disease pressure strongly influence fruit quality. Severe infestation impairs photosynthesis and assimilate flow, weakening structure and reducing compositional value, while eliminating all stress can limit antioxidant formation. Residue-free biological control provides the best balance by maintaining plant health and inducing mild defenses that enhance phenolics and vitamins. Biocontrol agents and elicitors also strengthen epidermal and cell-wall integrity, reducing water loss and decay. Thus, residue-free IPM improves both food safety and the nutritional and postharvest performance of greenhouse vegetables.

3.13. Major Interactions Between Climate Factors

Greenhouse climate factors interact rather than act independently, and these interactions ultimately shape fruit nutritional quality and shelf life. Temperature, light, RH, CO2, and water or nutrient supply jointly influence photosynthesis, transpiration, and stress metabolism, producing either synergistic or antagonistic effects. Recognizing these interactions is essential for interpreting experimental variability and optimizing climate control for both yield and postharvest performance.

In tomato, temperature and light interact most strongly because they jointly regulate pigment synthesis and fruit metabolism. High light increases lycopene and β-carotene only when fruit temperature stays below ~30 °C [60,62]. Above this threshold, heat suppresses carotenoid biosynthesis and produces orange rather than red fruits [60,296]. Elevated CO2 enhances sugar accumulation only when light is sufficient to sustain the extra photosynthetic demand [58,62,71,241]. RH–Ca interactions are equally important. High RH limits transpiration and Ca transport, predisposing fruits to BER despite adequate soil Ca [71,241], especially when combined with high temperature and rapid fruit growth [184,241]. In contrast, moderate VPD and stable irrigation improve Ca allocation and firmness [71,74,241]. Mild water deficit under strong light can raise soluble solids and phenolics, but high temperature shifts this response towards faster softening [59,62,164,241]. Thus, the effect of any single environmental factor depends on its interaction with others, underscoring the need for integrated rather than isolated climate control.

In cucumber, strong interactions among light, RH, and temperature govern growth and epidermal development. High radiation at moderate temperature supports firm, well-colored fruits, whereas the same radiation under high temperature causes excessive elongation and soft texture [99,100]. High RH reduces transpiration and cuticle deposition, but this becomes critical mainly under high temperature, producing fruits with fragile skin and poor postharvest behavior [117,118]. The combination of low RH and high temperature induces excessive water stress and curvature [120,220,230]. Interactions between CO2 enrichment and RH are also important. Elevated CO2 improves growth and firmness under moderate RH but loses effectiveness when condensation or high RH limits gas diffusion [113,220]. Water status further modifies these outcomes. Under bright, dry conditions, even mild irrigation deficits reduce yield and firmness, while the same deficit under high RH increases DM and phenolics [119,120]. Thus, microclimate interactions determine whether stress enhances quality or creates structural weakness.

In sweet pepper, interactions among light, temperature, and RH control pigment accumulation, firmness, and water loss. Carotenoid synthesis is stimulated by high radiation but suppressed by excessive heat [253,329]. Thus, shading or diffusive films that moderate fruit temperature improve color and antioxidant levels [149,153,170]. High RH with elevated temperature delays Ca transport and weakens pericarp strength, whereas moderate RH at similar temperature supports uniform color development and firmness [159,160]. Water–nutrient interactions are equally important. Mild water deficit under moderate radiation increases ascorbic acid and phenolics, but when combined with high temperature it causes softening and irregular ripening [142,166]. Elevated CO2 enhances yield and ascorbic acid only when temperature and light are optimal. Otherwise, assimilate accumulation outpaces structural reinforcement, producing large but fragile fruits [151,156]. Overall, pepper quality reflects the combined effects of these factors on sink strength, pigment biosynthesis, and tissue integrity rather than any single variable.

Greenhouse climate factors influence fruit quality through tightly linked pathways. Temperature shapes how light drives pigment and antioxidant synthesis, while RH and VPD interact with Ca and water relations to determine firmness and disorder risk. CO2 and light regulate carbohydrate accumulation, and water or salinity stress modifies these responses. Across crops, fruit temperature is the main integrator of radiation, air temperature, and RH, predicting both compositional and structural outcomes. Synergistic combinations improve quality, whereas antagonistic ones accelerate softening. Thus, optimal management relies on coordinated control of radiation, ventilation, RH, and fertigation to maintain moderate fruit temperature and ensure consistent quality.

3.14. Climate Change Implications

Projected climate change will intensify heat, alter VPD dynamics, and increase radiation loads, challenging microclimate stability even in greenhouses. Despite their buffering capacity, greenhouses remain vulnerable to heat and moisture imbalances that alter physiological and biochemical processes [95], ultimately affecting fruit composition, firmness, and storability.

Tomato cultivation in a warmer climate will face greater risks of elevated fruit temperature. Temperatures above 30 °C suppress lycopene and favor β-carotene synthesis, producing paler, less antioxidant-rich fruits [55,314]. Warm nights accelerate respiration and reduce acidity, shortening shelf life. Although higher CO2 (up to 800–1000 µmol mol−1) can support yield and soluble solids, these gains decline once heat and VPD exceed optimal thresholds [221,223]. Higher VPD can also impair Ca transport, increasing susceptibility to BER and microcracking [7,184,241]. Future production will therefore require improved cooling strategies (shading, evaporative or hybrid systems) and heat-tolerant cultivars that preserve pigment stability and firmness [95].

Cucumber is highly sensitive to warming and RH fluctuations due to its high transpiration rate and delicate epidermis. Higher temperature and radiation accelerate fruit elongation and water uptake, producing larger but softer fruits with shorter postharvest life [99,100]. Extreme heat can impair chlorophyll retention and trigger premature yellowing, while high VPD or water deficits intensify turgor loss [104]. Elevated CO2 may enhance photosynthesis and yield, but under excessive RH or low light, it can lead to watery texture and thin cuticles [112]. Climate change will therefore increase within-crop variability and reduce storability unless mitigated by effective cooling, diffusive covers, and precise irrigation. Adaptive measures such as dynamic shading, RZT control, and sensor-based RH management will be essential to maintain epidermal integrity and firmness [95].

Sweet pepper is more heat-tolerant than tomato or cucumber, yet extreme thermal and radiative stress still disrupts pigment and vitamin synthesis. Day temperatures above 32 °C or intense radiation can cause sunscald and uneven coloration, while warm nights accelerate softening and ascorbic acid loss [149,253,329]. Moderate CO2 enrichment may enhance sugars, ascorbic acid, and carotenoids, but these gains diminish when heat or water stress restricts photosynthesis [155,156,157]. Under dry conditions, higher transpiration and reduced Ca mobility lead to thinner pericarps and reduced firmness [160,161,195], whereas excessive RH in closed systems promotes soft tissue and pathogen development [116,160,234]. Increasing climatic variability will therefore require integrated control of temperature, RH, and air movement to maintain pigment development and shelf life [95]. Breeding for stronger pericarps and improved oxidative-stress tolerance will also enhance resilience.