1. Introduction

Wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) is the world’s second most produced cereal after maize, and its production and consumption are central to global food and feed systems. In recent years, global challenges such as climate change, population growth, and the COVID-19 pandemic have intensified pressures on food security and sustainable agricultural production [

1]. Wheat farming is a complex, dynamic sector of global agriculture, shaped by environmental and human factors. Achieving sustainable and productive wheat systems is crucial for meeting growing food and feed demands while minimizing environmental impacts.

Wheat is a nutritionally rich, containing carbohydrates, proteins, fibers, and minerals [

2,

3]. It serves as both a human staple and a key livestock feed resource [

4,

5]. As forage, wheat provides energy that supports healthy animal growth and metabolism through highly digestible proteins and carbohydrates. Whole-crop wheat forage, which utilizes leaves, stems, and spikes, offers a sustainable and resource-efficient feed option within integrated crop–livestock systems [

6].

Whole-crop wheat is typically preserved as silage. Proper ensiling involves chopping fresh biomass into small pieces, compacting to remove oxygen, and maintaining adequate moisture to promote anaerobic fermentation. During ensiling, soluble sugars convert to organic acids, such as lactic acid, which reduce pH and stabilize the material. Excess moisture can impair fermentation and yield undesirable by-products. Under optimal conditions, well-fermented silage retains nutritional quality for months and ensures long-term feed preservation [

7].

Colored wheat cultivars have garnered attention for their nutritional and functional benefits compared with conventional white wheat. Pigmented lines, such as purple, blue, or black wheat, contain high concentrations of anthocyanins (potent antioxidants that help support human and animal health) and are often rich in other phytochemicals, including dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals [

8,

9,

10]. Black wheat with high anthocyanin content can act as a natural colorant, adding color and health-promoting value in food processing [

11]. Consumers are increasingly drawn to unique products, and colored wheat-based foods have the potential to gain market advantage. These cultivars are also expected to influence future crop improvement and dietary innovation in plant breeding.

Although wheat is a valuable feed crop, the coarse awns on spikes reduce livestock palatability, limiting its direct forage use. Radiation breeding, a long-established technique, accelerates cultivar development using physical mutagens to induce useful mutations affecting traits such as flower and color, beneficial metabolite production, maturity, and adaptability to cultivation environments [

12,

13]. In bread wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.), gamma irradiation has generated novel phenotypes with altered morphology, enhanced metabolite profiles, and improved agronomic traits without requiring transgenic modification [

14,

15]. Such mutagenesis shortens breeding cycles and broadens genetic diversity by creating beneficial mutations associated with morphology, metabolism, and stress tolerance. Therefore, radiation breeding offers an efficient strategy for generating phenotypic diversity and expanding crop improvement potential.

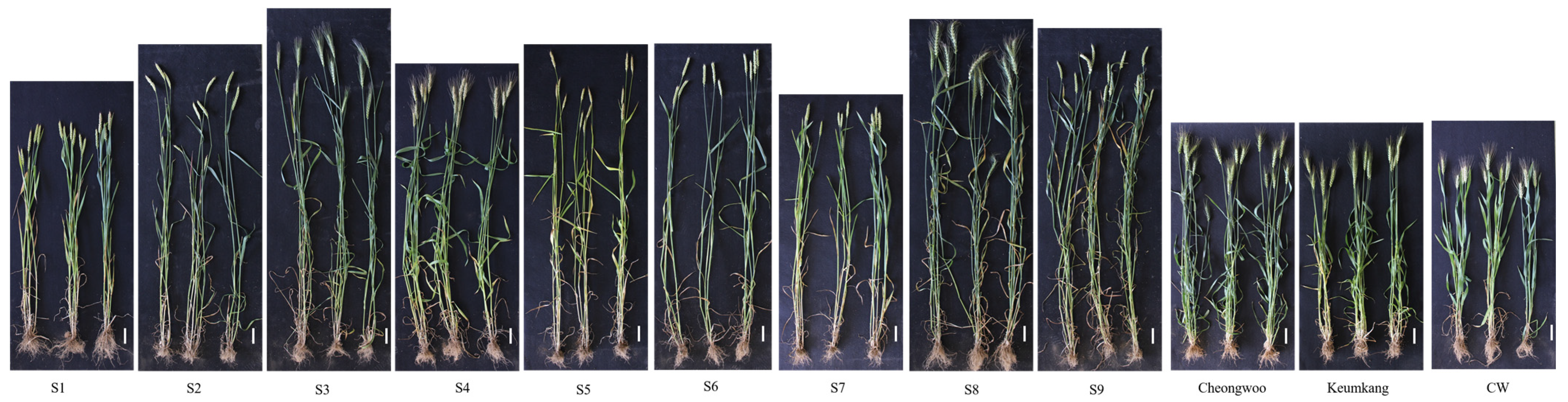

In this study, colored wheat mutant lines were developed through gamma irradiation and field selection, displaying diverse phenotypes favorable for forage use. Two commercial cultivars served as benchmarks: ‘Cheongwoo’, a forage-type wheat bred for high biomass, and ‘Keumkang’, a bread-type wheat widely cultivated in Korea. The study aimed to evaluate the forage potential of colored wheat mutants through comparative analyses of agronomic traits, chemical composition, silage fermentation characteristics, and antioxidant capacity. Overall, this research provides an initial assessment of the potential of colored wheat mutants as novel feed resources combining nutritional functionality with acceptable forage quality. Although the study is exploratory, its findings will help identify promising genetic materials for the improvement of functional forage wheat, with broader implications for enhancing livestock nutrition, optimizing feed formulation, and guiding future breeding strategies for dual-purpose cereal crops. future improvement of functional forage wheat.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the forage and silage potential of gamma irradiation-induced colored wheat mutant lines through an integrated assessment of agronomic performance, compositional traits, fermentation quality, and antioxidant capacity. Gamma irradiation is a proven mutagenic approach for increasing genetic variability and accelerating novel phenotype development in cereal crops, including wheat. The mutant population examined in this study displayed diverse morphological and biochemical variations relevant to whole-crop utilization. Compared with the forage-type control cultivar ‘Cheongwoo’, several mutants showed equal or superior performance in biomass accumulation and compositional quality while maintaining acceptable fermentation and antioxidant profiles. These results demonstrate that physical mutagenesis derived from gamma irradiation can induce marked phenotypic diversity without transgenic modification, offering a valuable resource for developing functional forage wheat germplasm that combines nutritional and agronomic advantages. Unlike chemical mutagens or targeted genome-editing approaches, gamma irradiation generates a wide spectrum of random mutations with relatively stable inheritance, enabling the discovery of novel allelic variations that may not be accessible through conventional breeding. Although the approach requires extensive phenotypic screening to identify desirable traits, its non-transgenic nature and broad mutational coverage make it a practical and environmentally acceptable tool for crop improvement, particularly in developing functional forage wheat lines.

The pronounced variation in fresh and dry biomass among the colored wheat mutants reflects genetic and physiological heterogeneity caused by gamma irradiation. Consistent with previous studies on radiation-mutagenized cereals, gamma treatment can create considerable variability in vegetative growth- and structural development-related traits [

21,

22]. Several mutant lines achieved dry matter yields equal to or exceeding the forage-type control ‘Cheongwoo’, suggesting that mutagenesis did not compromise biomass productivity. Notably, S8 accumulated significantly greater DW relative to the controls, likely due to enhanced stem robustness and increased assimilate partitioning to structural tissues. Similar observations were made in soybean, where Rogers et al. [

23] reported that forage-type genotypes produced significantly more stem biomass compared with grain-type cultivars.

The lower FW/DW ratio observed in S8 further indicates a higher structural dry matter proportion and reduced water content, traits desirable for silage production, as excessive moisture can hinder fermentation [

24,

25]. Conversely, ‘Cheongwoo’ and ‘Keumkang’ exhibited higher FW/DW ratios, reflecting greater moisture retention and softer tissue composition, which favor palatability in fresh forage but reduce long-term silage stability. Therefore, variation in water retention and tissue density among mutants may indicate distinct utilization potential, i.e., lines with higher DW and lower FW/DW ratios may suit silage production, whereas those with higher FW may be better suited for green-forage systems. Overall, these findings suggest that gamma irradiation-induced variation in biomass productivity and dry matter composition provides a foundation for selecting highly adaptable colored wheat mutants with biomass traits suited to forage or silage applications.

To further evaluate the mutants’ potential as hay-type whole-crop forage resources, proximate and fiber compositions were analyzed relative to the forage-type control ‘Cheongwoo’ and bread-type control ‘Keumkang’. Substantial differences in crude protein levels, fiber fractions, and mineral content among genotypes indicated that gamma irradiation effectively induced metabolic and structural diversity within the colored wheat background. Crude protein content strongly influences forage nutritional value and digestibility [

25]. Several mutants, particularly S9, exhibited crude protein concentrations comparable to or higher than those of ‘Cheongwoo’, implying that certain radiation-induced lines can maintain adequate protein content despite altered plant architecture. Similar protein variation has been reported among gamma irradiation-induced cereal mutants, where mutagenesis affects nutrient uptake, utilization efficiency, and storage protein allocation [

22,

26,

27].

S8 exhibited the highest crude fiber and NDF levels, along with elevated cellulose and hemicellulose contents, indicating increased structural carbohydrate accumulation. Although high fiber levels can reduce digestibility, moderate increases in NDF and cellulose contents have been linked to improved standability and biomass stability in whole-crop forage systems. Prior studies have shown that NDF digestibility depends on cell wall composition and lignin biosynthesis [

28,

29]. The high cellulose and lignin concentrations observed in several mutants (e.g., S3, S7, and S8) suggest carbon partitioning toward secondary cell wall formation, potentially linked to delayed senescence and enhanced biomass resilience. These compositional modifications may influence forage digestibility and silage fermentation, as cellulose and lignin determine fiber-bound nutrient availability and microbial degradation [

30].

‘Cheongwoo’ maintained balanced fiber and crude protein levels, yielding a high RFV, consistent with its known forage performance. Conversely, mutants with elevated structural fiber content (e.g., S8) displayed reduced RFVs but higher dry matter concentrations, improving their ensiling suitability. The similarity in TDNs and stable forage pH across all lines indicates that radiation-induced modification of structural carbohydrate composition did not negatively affect overall nutritional balance or fermentability. Collectively, these findings show that gamma irradiation generates valuable variation in forage-related traits, ranging from high-protein to high-fiber phenotypes, thereby broadening the genetic base for developing colored wheat cultivars optimized for specific forage purposes.

To determine whether gamma-irradiated colored wheat lines could also serve as silage resources, their nutrient composition, fermentation characteristics, and buffering capacities were compared with those of ‘Cheongwoo’ and ‘Keumkang’. Overall, the mutants maintained silage nutritional profiles similar to control cultivar profiles, indicating that radiation-induced mutations did not compromise ensiling potential. Crude protein and carbohydrate levels were largely consistent across genotypes; thus, substrates essential for fermentation, primarily soluble sugars and degradable nitrogen, remained within an optimal range for lactic acid fermentation [

7,

31]. Some mutants, such as S3 and S6, exhibited elevated crude protein levels that may enhance microbial activity during early fermentation, whereas S5, despite slightly higher structural fiber fractions (NDF and ADF), maintained acceptable RFVs. These findings align with previous reports that adequate fermentable carbohydrate and nitrogen availability ensures efficient lactic acid fermentation and stable silage quality in forage crops [

32,

33].

Fermentation acid profile analysis revealed clear genotype-specific patterns. S2–S4 showed higher lactic acid accumulation comparable to that of ‘Cheongwoo’, indicating efficient fermentation and adequate sugar supply [

34,

35]. In contrast, S6 and S8 exhibited higher silage pH and lower lactic acid content, highlighting slower acidification and reduced microbial efficiency [

36]. ‘Cheongwoo’ produced abundant acetic acid, often linked to improved aerobic stability, whereas most mutants generated lower levels, consistent with a more homofermentative profile favoring short-term preservation but offering less protection against aerobic spoilage [

37,

38]. These findings align with prior studies showing that lactic acid bacteria inoculation or inherent genotype differences can shape organic acid balance and stability in wheat and corn silage.

Buffering capacity measurements supported these interpretations. S6 and S8 showed markedly higher aBC, reflecting greater resistance to pH change that could slow acidification during early fermentation. Similar outcomes have been reported for fermented feedstuffs, where higher buffering capacity delayed pH decline [

39]. Conversely, most mutants, including S1, S4, and S9, showed near-zero aBC values comparable to those of ‘Cheongwoo’ and ‘Keumkang’, indicating lower resistance to acid change and faster pH reduction, favoring more stable preservation. This finding is supported by prior research showing that lower forage buffering capacity is associated with faster pH decline during ensiling [

40]. Collectively, these results indicate that most gamma-irradiated colored wheat lines retained desirable silage fermentation characteristics, although some physiological differences were evident. S3 and S6 combined higher crude protein content with stable fermentation, showing potential for dual-use systems, whereas lines with elevated buffering capacity, e.g., S8, may require co-ensiling with more fermentable crops. Nevertheless, considering the broader objective of identifying whole-crop forage candidates, most mutants (particularly those with high dry matter and moderate fiber content) appear better suited for fresh or dried forage rather than silage-specific applications.

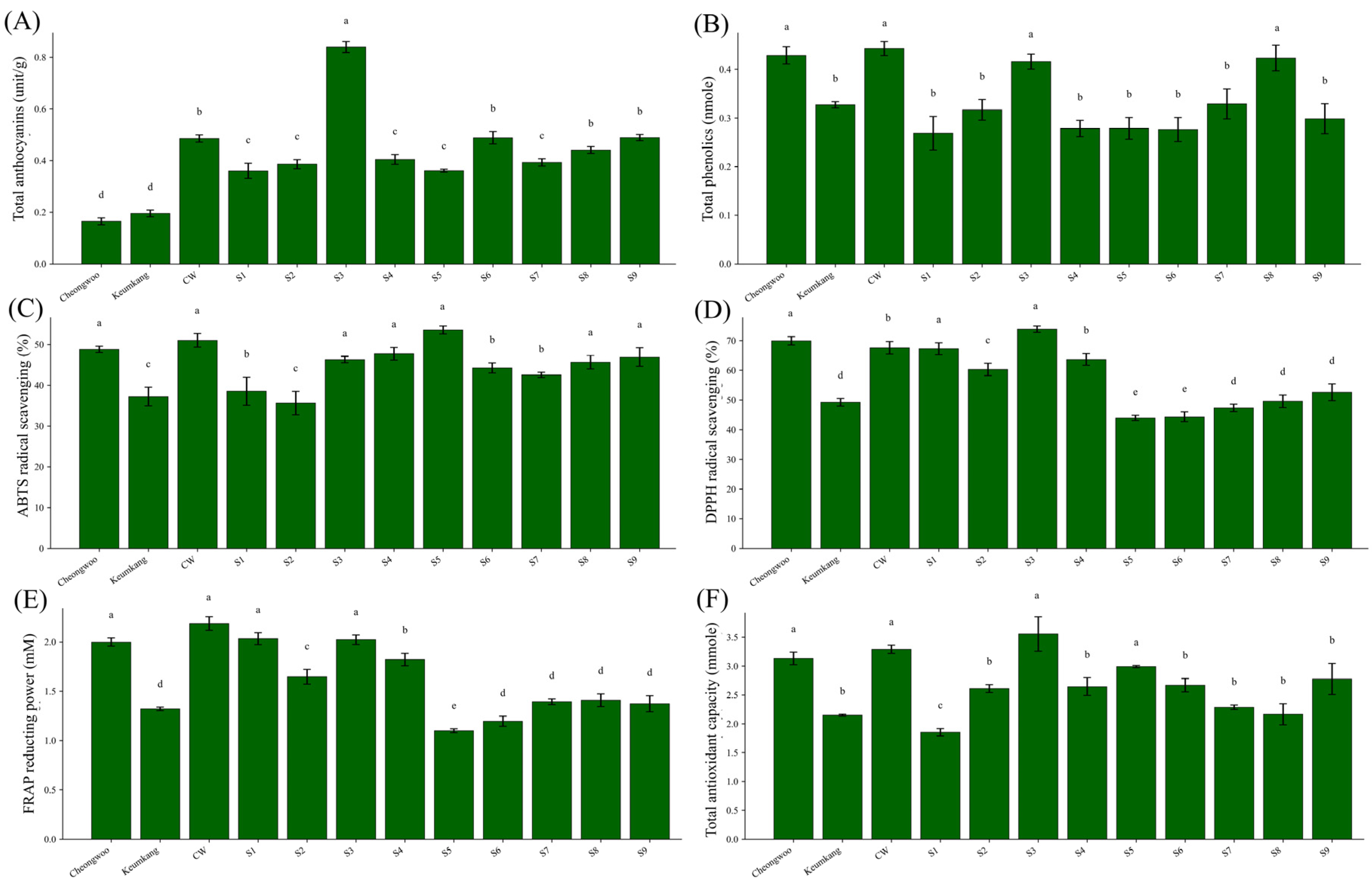

Analysis of antioxidant profiles among the gamma-irradiated colored wheat lines revealed marked genotypic variation in anthocyanin accumulation, phenolic content, and radical scavenging activity, reflecting substantial mutation-induced metabolic diversification. All colored wheat lines, including the original line and its derived mutants, were clearly separated from nonpigmented control cultivars, confirming stable expression of pigmentation through successive mutation generations. This is consistent with reports that seed color and anthocyanin-rich phenotypes remain heritable in wheat. Retention of anthocyanin biosynthetic capacity aligns with previous findings showing that colored wheats maintain stable anthocyanin profiles and that processing or environmental factors may alter quantitative phenolic levels without suppressing pigment pathways [

41,

42].

Moreover, studies in cereals have further demonstrated that gamma irradiation can alter grain phenolic composition, increasing bound phenolic acids or modifying phenolic fractions while leaving anthocyanin biosynthesis largely intact, indicating that irradiation primarily changes quantitative profiles rather than eliminating pigmentation potential [

43,

44]. Among the mutants, S3 exhibited the highest total anthocyanin and phenolic levels, along with superior antioxidant activity across ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP assays. These results suggest that S3 underwent metabolic reprogramming favoring enhanced synthesis or accumulation of phenylpropanoid-derived antioxidants. Consistent with prior research, higher TPC correlates strongly with increased antioxidant activity in crops [

45,

46]. Conversely, several mutants (e.g., S5–S9) displayed reduced DPPH and FRAP activities despite moderate pigment intensity, indicating that qualitative differences in phenolic composition, rather than pigment concentration alone, govern antioxidant capacity. Such genotype-specific antioxidant patterns are typical among colored wheat accessions differing in their acylation and flavonoid composition [

47]. ‘Cheongwoo’, although nonpigmented, displayed unexpectedly high TPC and antioxidant values, likely owing to the accumulation of nonanthocyanin phenolics, such as ferulic acid and flavones, common in lignified tissues. Therefore, forage-type morphology and antioxidant metabolism may be partially linked, as lignin biosynthesis shares upstream precursors with the phenylpropanoid pathways responsible for antioxidant formation [

48,

49].

Practically, mutants with high antioxidant potential, especially S1 and S3, offer added value beyond forage productivity. Their elevated phenolic and anthocyanin contents may enhance feed oxidative stability and support functional feed or food applications. Thus, incorporating such lines into whole-crop forage systems could provide dual benefits: high-yield with nutrient-rich biomass production and natural antioxidant capacity to improve feed quality and animal health. Although this study primarily examined the forage value, fermentation characteristics, and antioxidant traits of colored wheat mutant lines, several physiological and nutritional aspects warrant further investigation. Future controlled-environment studies should evaluate the mutants’ sensitivity to UV exposure, particularly during germination, to clarify whether pigment accumulation contributes to photoprotection or DNA repair. In addition, comparative analyses of trace elements (e.g., selenium, zinc) and antioxidant metabolites such as glutathione between mutant and control lines would help reveal potential nutritional advantages and their relevance to climate-related stress tolerance. Such work would further elucidate the functional value of colored wheat germplasm for both agricultural and human health applications.