Abstract

Spatially quantifying the soil carbon sequestration potential (SCSP) is crucial for targeting climate change mitigation strategies like carbon farming. However, static mapping approaches often fail by assuming that the drivers of soil organic carbon (SOC) are stationary. We hypothesized that the hierarchy of SOC controllers is fundamentally non-stationary, shifting from intrinsic stabilization capacity (pedology) in stable ecosystems to extrinsic flux kinetics (climate) in dynamic systems. We tested this by developing a land-use-specific (LULC; Cropland, Forest land, Grassland) ensemble machine learning (ML) framework to quantify the soil carbon saturation deficit (SCSD) across Croatia’s pedologically diverse landscape on 622 soil samples. The LULC-stratified ensemble models (SVM, RF, CUB) achieved moderate to good predictive accuracy under cross-validation (R2 = 0.41–0.60). Crucially, the feature importance analysis (permutation MSE loss) proved our hypothesis: in Forest land, SOC was superiorly controlled by intrinsic capacity (Soil CEC, Soil pH), defining the mineralogical C-saturation “ceiling”; in Grasslands, control shifted to extrinsic C-input kinetics (Precipitation: Bio19, Bio12), which “fuel” the microbial carbon pump (MCP) via root exudation; and in Croplands, the model revealed a hybrid control, limited by remaining intrinsic capacity (CEC, Clay) but strongly influenced by C-loss kinetics (Temperature: Bio08), which regulates microbial carbon use efficiency (CUE). This study demonstrates that LULC-specific dynamic modeling is a prerequisite for accurately mapping SCSP. By identifying soils with both high intrinsic capacity (high CEC/Clay) and high degradation (high SCSD), our data-driven assessment provides a critical tool for spatially targeting carbon farming interventions for maximum climate mitigation return on investment (ROI).

1. Introduction

Soil is a fundamental natural capital that provides essential ecosystem services critical for human sustainability. These services underpin global stability by securing over 95% of food production, regulating hydrological cycles through water purification and storage, harboring more than a quarter of planetary biodiversity, and mitigating climate change via massive carbon storage [1,2]. A primary symptom of widespread soil degradation is the drastic loss of native soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks, estimated at 30–70% compared to their natural state. This historical carbon debt, emitted as CO2, has created what is known as the “Soil Carbon Saturation Deficit” (SCSD) [3,4]. This deficit redefines how we view these degraded soils: they are “carbon-hungry” and operate far below their maximum storage capacity, which is controlled by their intrinsic properties (e.g., clay content) [5]. Therefore, the sequestration potential of agricultural soils is not their current state, but rather their potential to reverse this degradation [6].

By implementing regenerative or conservation agriculture practices (e.g., no-till, cover cropping), organic matter inputs can be managed to exceed mineralization losses. Sequestration, in this context, is a process of re-accumulation restoring this historical carbon debt [7]. This restoration of SOC is central to reversing degradation: it simultaneously rebuilds soil as a functional, living system, restores the foundation of soil fertility for food production, and transforms the soil into a vital carbon sink for climate change mitigation [8]. A soil’s capacity for SOC sequestration is complex, depending on internal properties and external drivers that together control the balance between C inputs and mineralization rates [9]. The intrinsic storage capacity is primarily controlled by physico-chemical properties, particularly soil texture, where the high specific surface area (SSA) of the clay fraction drives stabilization by adsorbing organic molecules to form stable organo-mineral associations (OMAs) [10,11]. The effectiveness of this binding depends on clay mineralogy: soils rich in 2:1 phyllosilicates (e.g., smectite) with a high cation exchange capacity (CEC) are much more effective at stabilizing SOC than those dominated by 1:1 minerals (e.g., kaolinite) [12,13,14]. This chemical stabilization is strengthened by polyvalent cations (e.g., Ca2+, Fe3+, Al3+) acting as cation bridges between negatively charged mineral surfaces and organic functional groups [15,16].

SOC dynamics are governed by both soil-specific factors, such as CaCO3-derived Ca2+ flocculation enhancing physical protection in alkaline soils, and dominant climatic drivers, where temperature exponentially controls microbial respiration (Q10) and precipitation dictates C inputs via net primary production (NPP) [17]. Locally, moisture regimes can override climate and poorly drained soils (e.g., Gleysols) develop anoxic conditions that drastically inhibit microbial decomposition, favoring the extreme C accumulation that forms Histosols (peat) [18]. Finally, biological factors are the engine of the process with vegetation type determines the quantity and quality (e.g., C:N ratio, lignin content) of inputs where grassland ecosystems, with their high root:shoot ratio, are exceptionally effective at building SOC [19,20]. The microbial community’s composition (e.g., fungal:bacterial ratio) and its carbon use efficiency (CUE) ultimately determine how much C is respired versus transformed into stable microbial necromass [21]. While traditional models focused on the recalcitrance of plant-derived inputs (e.g., lignin), recent evidence shows that this microbial necromass is the dominant precursor to long-term, mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) [22].

Land use (e.g., forest, grassland, cropland) directly controls the relative contribution of the two primary sequestration pathways: (1) the litter pathway, which primarily forms short-lived particulate organic matter (POM); (2) the microbial carbon pump (MCP), which forms persistent MAOM from microbial necromass [23,24]. In forest systems, above-ground litter inputs (high C:N) fuel a fungal-dominated decomposition pathway, leading to slow C release and the formation of a surface POM pool. In contrast, grasslands are characterized by high-turnover root networks that release large quantities of labile C via rhizodeposition. These exudates fuel a rapid, bacterial-dominated metabolism the MCP which efficiently transforms labile plant C into stable, mineral-associated microbial necromass [22]. Conventional tillage is a chronic physical disturbance that compromises both pathways and it not only reduces C inputs via residue removal but also physically disrupts soil aggregates, exposing previously occluded POM and, critically, the stable MAOM fraction to microbial oxidation. A significant challenge for digital soil mapping of SOC is the implicit assumption of stationarity that the hierarchical importance of SOC drivers (e.g., climate vs. pedology) is uniform across a landscape [25,26]. This assumption is biogeochemically deficient. The factors controlling C accumulation under a stable forest (e.g., mineral stabilization capacity) are fundamentally different from those controlling C flow in a dynamic grassland (e.g., precipitation-driven C-inputs) or a chronically disturbed cropland (e.g., temperature-driven C-loss) [27]. This implies that the very hierarchy of SOC controllers is itself non-stationary, shifting based on the dominant C-cycling pathway (POM vs. MCP) dictated by land use. While these mechanisms (SCSD, MAOM vs. POM) are conceptually well-understood, a spatial quantification of sequestration potential at a national scale one that integrates intrinsic soil properties with external land-use pressures is critically lacking. Such mapping is essential for the targeted deployment of effective climate mitigation strategies. This study uses digital soil mapping and machine learning to bridge this methodological gap, providing the first comprehensive machine learning assessment of soil carbon sequestration potential for Croatia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area—Sampling Data, Pedology and Climate

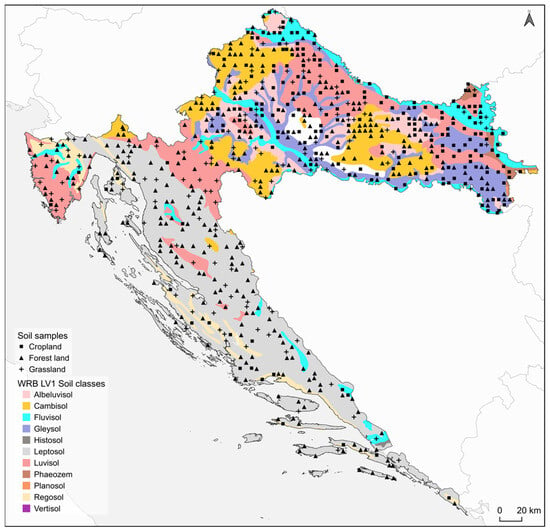

The study area includes the Republic of Croatia (56,594 km2), a Southeastern European country located at the junction of the Pannonian Basin, the Dinaric Alps, and the Adriatic Sea (Figure 1). Croatia is characterized by exceptional pedodiversity resulting from a complex interplay of geological substrate (dominated by karstic carbonate bedrock in the Dinaric region), variable relief, and three distinct climate zones (continental, mountain, and mediterranean). This complexity yields one of Europe’s highest soil type densities, with 25 of the 32 World Reference Base (WRB) Reference Soil Groups (RSGs) present in Croatia. Dominant soil groups vary significantly by pedogeographical region. The Pannonian lowland region is dominated by productive Stagnosols, Luvisols, Fluvisols (along river valleys), and Chernozems in the east [28,29]. The mountainous Dinaric region is characterized by shallow Leptosols (including Rendzinas) on karstic bedrock and extensive Cambisols. The narrow Adriatic coastal belt features predominantly Terra Rossa (often classified as Rhodic Cambisols) and Calcocambisols [30]. The soil dataset was obtained from the Croatian Agency for the Environment and Nature (CAEN) Web Feature Service (WFS), sourced from a 2016 national field campaign. All samples were collected from the 0–30 cm topsoil layer. Field sampling for each Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) category followed a modified version of the Joint Research Centre (JRC) protocol for monitoring soil organic carbon stocks in the EU [31,32]. The study area, Croatia, possesses a highly diverse climate, characterized by a Mediterranean coast, a temperate continental interior, and distinct mountain regions. All high-resolution (1 km) climatic data used for this analysis, including bioclimatic variables based on temperature and precipitation averages, were obtained from the CHELSA v2.1 dataset [33]. In the laboratory, soil sample pre-treatment (drying, crushing, sieving) followed ISO 11464:2006 [34]. SOC content was determined by elemental analysis (dry combustion) according to ISO 10694:1995 [35], presumably after accounting for carbonates [34,36,37].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area (Croatia) showing the spatial distribution of dominant soil types (according to WRB LV1 classification) and the locations of the collected soil samples. Symbols indicate the three main LULC categories: Cropland (■), Forest land (▲), and Grassland (+).

2.2. Physical and Chemical Soil Properties

The dataset provided a comprehensive suite of laboratory analyses for all samples. Dried samples were analyzed for: pH (in H2O and CaCl2 solution), coarse fragments, Particle Size Distribution (PSD), CaCO3 content, CEC and SOC. All soil analyses followed standard procedures; specifically, particle size distribution (separating sand, silt, and clay fractions) was determined using the sieving and sedimentation method (ISO 11277) [34,36,37,38]. For this modeling study, the key pedological covariates selected were SOC, CaCO3, pH, CEC, and soil texture (clay, silt, and sand fractions). SOC content is expressed as a mass fraction in g kg−1. The outliers were removed using the interquartile range (IQR) method, eliminating all samples with SOC values outside of the 1.5 IQR above the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartile. The IQR method was specifically chosen to filter out organic soils (Histosols) and focus the analysis strictly on the stabilization mechanisms of mineral soils, as organic soils operate under distinct hydrological drivers not targeted by this framework.

2.3. Prediction of SOC Content Based on Machine Learning and Feature Importance Calculation

Four machine learning algorithms, including random forest (RF), cubist (CUB), support vector machine regression (SVM) and Bayesian regularized neural networks (BRNN) were evaluated for prediction of SOC content for each of three LULC classes. Input covariates for SOC prediction included seven soil properties (clay, silt, sand content, soil pH, CEC, CaCO3 and WRB level 1 soil class) and 19 bioclimatic variables from CHELSA dataset. Although clay, silt, and sand sum to 100%, tree-based ensemble algorithms (RF, Cubist) are non-parametric and robust to multicollinearity, handling redundant features through recursive partitioning. Therefore, all three fractions were retained to preserve the interpretability of textural splitting rules. These covariates were preprocessed based on correlation analysis, with all covariates achieving Pearson’s correlation coefficient with another covariate higher than 0.95 being excluded from the prediction. Hyperparameter optimization was performed using a random search in 10 repetitions within each cross-validation fold to prevent data leakage, while predictor importance was assessed using permutation feature importance. Feature importances for each covariate were calculated using the model-agnostic approach based on mean square error (MSE) loss, estimating the contribution of a single feature to model performance by permuting the feature values at random and measuring the change in model performance.

The RF regression algorithm builds an ensemble of decision trees, integrating the concepts of bootstrap aggregating and random feature selection [39]. Each tree within the forest is trained on a different bootstrap sample of the original dataset [40]. During tree construction, at each internal node, the algorithm selects the best split from a random subset of predictors (defined by the ‘mtry’ hyperparameter) rather than from all available features [41]. The final prediction is the average of the results from all constituent trees, a mechanism that effectively reduces prediction variance. This dual randomization makes RF robust, allowing it to maintain predictive power and generalization even when dealing with high-dimensional datasets containing correlated or irrelevant features where traditional regression models might overfit.

CUB regression is a rule-based algorithm that generates model trees, utilizing linear regression models at the leaf nodes to capture localized linear patterns [42]. It employs a boosting-like strategy (‘committees’), where subsequent models are built to correct the residual errors of the preceding ensemble [43]. CUB then applies an instance-based correction (‘neighbors’), which refines the rule-based prediction by averaging the weighted residuals of the k-most similar training cases, thereby integrating global rule patterns with local neighborhood adjustments [43].

SVM projected input features into a high-dimensional space to identify linear relationships [44]. The algorithm determines an optimal hyperplane based on a subset of training points known as support vectors. We utilized the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, where the σ hyperparameter regulates the influence radius of samples [45]. The regularization parameter ‘C’ manages the trade-off between minimizing prediction errors and controlling model complexity [45]. Predictions are generated by evaluating the kernel function between the test instance and the support vectors, which are weighted by their corresponding Lagrange multipliers [46].

BRNN integrate a multilayer perceptron architecture with Bayesian inference principles [47]. This approach treats network weights as random variables with prior probability distributions rather than fixed parameters. We used a three-layer architecture, with the ‘neurons’ hyperparameter defining the hidden layer size [48]. The Bayesian framework provides inherent regularization by updating weight distributions via Bayes’ theorem during training, which mitigates overfitting without requiring a validation set for early stopping. Consequently, predictions are derived by marginalizing the posterior weight distribution, a process that uniquely yields both a point estimate and an associated measure of uncertainty [47].

The accuracy assessment of predicted SOC content was performed using the nested cross-validation with 5-fold outer cross-validation and 10-fold inner cross-validation. The coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) were used as statistical metrics to quantify prediction accuracy, with higher R2 and lower RMSE and MAE indicating higher prediction accuracy.

In this study, the SCSD was not calculated via a deterministic geospatial formula per pixel, but rather defined statistically as the difference between the median SOC stocks of the “saturation reference” (Forest/Grassland) and the current stocks in Cropland for corresponding soil types (as visualized in the results).

3. Results

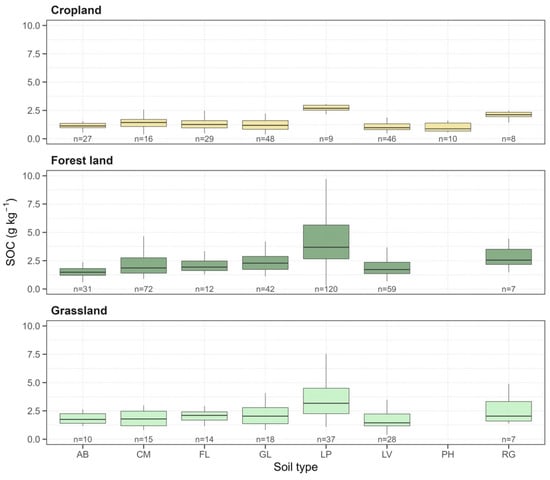

The distribution of SOC across land-use categories and soil types is presented in Figure 2. The results clearly indicate that land use has a dominant effect on SOC concentrations. Forest land consistently shows the highest median SOC values compared to the other two categories. Within forest soils, the Leptosol (LP) soil type (n = 120) is highly distinct, exhibiting the highest median (approx. 4.0 g kg−1) and the largest IQR, spanning from ~2.5 to 5.5 g kg−1. This indicates both high variability and a high capacity for carbon accumulation. Other soil types in this category (e.g., CM, GL, LV) show lower, yet still significant, medians, generally clustered between 1.8 and 2.7 g kg−1. Grassland soils exhibit moderate SOC levels, generally lower than those in forests but significantly higher than in cultivated soils. Paralleling the forest data, Leptosols (LP) (n = 37) and Regosols (RG) (n = 7) display the highest median values within this category (LP median approx. 3.0 g kg−1). In stark contrast, Cropland soils show drastically low SOC concentrations irrespective of soil type. Median values for all soil types in this category are extremely low, generally below 1.5 g kg−1, and approach 1.0 g kg−1 for some types (e.g., LV, PH). The overall variability (i.e., the spread of the boxes and whiskers) within the Cropland category is considerably constrained compared to Forest land and Grassland, indicating a homogenization and general depletion of SOC under agricultural systems.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the soil organic carbon (SOC; g kg−1) distribution among three land-use categories (Cropland, Forest land, and Grassland) and eight soil types. The horizontal line within the box marks the median, while the box defines the interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentile). The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR. The number of samples (n) is displayed for each group. (WRB LV1 Soil classes: AB = Albeluvisol, CM = Cambisol, FL = Fluvisol, GL = Gleysol, LP = Leptosol, LV = Luvisol, PH = Phaeozem, RG = Regosol.)

The performance of the base machine learning algorithms was compared within each land-use category (Table 1). The cross-validation results clearly show that no single algorithm was universally superior; the optimal model was land-use specific. For Cropland, SVM showed the highest average performance, explaining 41.1% of the variance (R2 = 0.411) with the lowest mean RMSE (0.420 g kg−1). BRNN (R2 = 0.396) and RF (R2 = 0.376) had slightly lower performance, while CUB (R2 = 0.262) performed significantly worse. For Forest land, RF achieved the highest performance (R2 = 0.604) and the lowest error (RMSE = 0.871 g kg−1). CUB was highly competitive with a slightly lower R2 (0.586). For Grassland, CUB was clearly superior, explaining 59.1% of the variance (R2 = 0.591) and achieving the lowest error (RMSE = 0.654 g kg−1), significantly outperforming the other models. Based on these results, SVM (for Cropland), RF (for Forest land), and CUB (for Grassland) were selected as the optimal machine learning methods for feature importance assessment for their respective LULC classes.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of the base machine learning algorithms (BRNN, CUB, RF, SVM) from cross-validation within each land-use category. Values represent the mean and standard deviation (SD) for the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE; g kg−1), and mean absolute error (MAE; g kg−1).

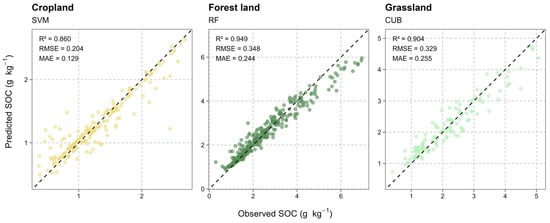

The performance evaluation of the selected best-performing models (SVM, RF, CUB) for each land-use category is presented in Figure 3. The validation scatterplots show high predictive accuracy and robustness for all three models. The RF model, applied to the Forest land data, demonstrated the highest performance, explaining 94.9% of the variance (R2 = 0.949) with an RMSE of 0.348 g kg−1 and an MAE of 0.244 g kg−1. The scatterplot (middle panel) confirms an exceptionally tight fit between predicted and observed SOC values across the entire range. High predictive power was also achieved by the CUB model for Grassland (right panel), which explained 90.4% of the variance (R2 = 0.904) with an RMSE of 0.329 g kg−1 and an MAE of 0.255 g kg−1. The SVM model for Cropland (left panel) explained 86.0% of the variance (R2 = 0.860). Notably, this model, despite a lower R2 (partially attributable to the significantly narrower range of observed SOC values in cropland), achieved the lowest absolute errors of all three models (RMSE = 0.204 g kg−1; MAE = 0.129 g kg−1). In all three cases, the observed values are evenly distributed around the 1:1 line (dashed line), indicating minimal model bias.

Figure 3.

Model fit scatterplots comparing observed (Observed SOC) and predicted (Predicted SOC) soil organic carbon values (g kg−1). Results are shown for the best-performing model within each land-use category: Cropland (SVM), Forest land (RF), and Grassland (CUB). The dashed line represents the 1:1 line. Performance metrics are displayed: coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE). These metrics represent the training fit accuracy to illustrate the algorithms’ learning capacity for rigorous generalization performance and cross-validation metrics, please refer to Table 1.

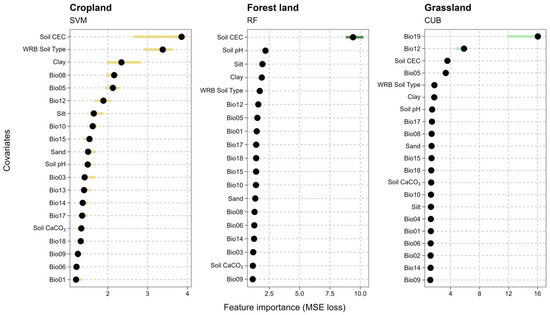

A feature importance analysis, assessed via permutation as the MSE loss, revealed that the hierarchy of key SOC controllers differs fundamentally across land-use categories (Figure 4). For the Forest land (RF) model, the results were unequivocal. Soil CEC was identified as the overwhelmingly dominant predictor (MSE loss > 9.0), exerting manifold greater influence than all other variables. It was followed by other intrinsic pedological factors: Soil pH, Silt, and Clay. Notably, all climatic (Bio) variables had a negligible or very low impact on SOC prediction within the forest system. In stark contrast, the Grassland (CUB) model exhibited a completely different hierarchy, one dominated by climatic factors. The most important predictors were Precipitation of Coldest Quarter (Bio19) and Annual Precipitation (Bio12). Pedological properties, while still relevant (Soil CEC, WRB Soil Type, Clay), played a secondary role relative to water availability. The Cropland (SVM) model revealed a hybrid influence from both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The most important predictors were intrinsic soil properties that define storage capacity: Soil CEC, WRB Soil Type, and Clay. However, unlike in the forest model, climatic variables, specifically Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter (Bio08), Max Temperature of Warmest Month (Bio05), and Annual Precipitation (Bio12), also showed a high degree of importance in explaining SOC variability in these agricultural systems.

Figure 4.

Feature importance for the three best-performing models per land-use category (Cropland—SVM, Forest land—RF, Grassland—CUB). Importance was quantified using permutation, calculated as the average loss in model accuracy (MSE loss) when the values of a single predictor were randomly shuffled. Longer bars indicate a greater impact of the covariate on SOC prediction.

4. Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to quantify the soil carbon sequestration potential (SCSP), defined as the difference between current SOC stocks and the soil’s intrinsic capacity the “Soil Carbon Saturation Deficit” (SCSD) [49,50]. Our results (Figure 2) provide clear visual evidence for this concept. High SOC concentrations in Forest land and Grassland do not represent high sequestration potential but rather serve as a critical benchmark. They indicate the approximate storage capacity a given soil type (e.g., Leptosol) can achieve at equilibrium (steady state) with its climate and native vegetation [51,52,53]. In contrast, the drastically low SOC concentrations in Cropland, regardless of soil type, directly visualize and quantify the SCSD. This gap for example, between the median Leptosol in forests (~4.0 g kg−1) and in cropland (<2.0 g kg−1) represents the achievable sequestration potential that can be targeted by regenerative agriculture. Figure 2 reveals a parallel pattern for SOC concentrations in Grassland and Forest land, with Leptosols consistently showing the highest concentrations in both. This paradoxical finding is a direct consequence of their intrinsic chemistry [27,54]. A significant portion of these soils is defined by high calcium carbonate content (CaCO3 > 40%) near the surface (FAO/ISRIC/ISSS 1998) [55]. The abundance of dissolved ions acts as a key stabilization agent, forming “cation bridges” that bind clay minerals and organic molecules [17,56]. This mechanism effectively protects Mineral-Associated Organic Matter (MAOM) from microbial mineralization, resulting in high SOC concentrations despite the low total soil volume [57,58]. The elevated SOC in Regosols (RG) follows a similar principle. Although they are weakly developed (AC-profiles), their parent material in Croatia is often carbonate-rich. Similarly to Leptosols, direct contact between organic matter and Ca2+ promotes efficient MAOM stabilization. However, these carbonate-soils represent a “double-edged sword”: their carbon is chemically stable but highly vulnerable to physical disturbance. Lacking the well-developed aggregate structure of deeper soils, their conversion to cropland via tillage catastrophically disrupts these weak bonds, exposing the stabilized MAOM to oxidation [59,60,61]. This explains the drastic C loss in these soils and highlights them as priority areas for conservation (no-till) practices.

Conversely, the consistently low SOC concentrations in Albeluvisols and Fluvisols across all three land uses (Figure 2) point to fundamental pedogenetic limitations rather than just tillage-induced degradation. For Albeluvisols, intensive eluviation (forming the diagnostic E horizon) results in extremely low natural fertility (low pH, nutrient-poor), which limits Net Primary Production (NPP) and thus C-inputs, even in native systems [62,63]. For Fluvisols, which are young AC-profile soils, the limitation is the lack of stabilization mechanisms. Their SOC capacity is purely lithological (texture-dependent) [64]. The low values observed indicate our sampled Fluvisols are likely dominated by coarser textures (sandy-silty), offering minimal mineral protection for MAOM and allowing rapid mineralization regardless of land use. Our machine learning models (Figure 4) further explain these patterns by revealing the hierarchy of drivers that define both the capacity and achievability of sequestration. SOC persistence is a dynamic equilibrium between C-inputs and stabilization controlled by both intrinsic (pedological) and extrinsic (climatic) factors, and intrinsic controllers (Clay, CEC) define the MAOM stabilization capacity [65,66,67]. We acknowledge a potential endogeneity in using Soil CEC as a predictor, as organic matter itself contributes to cation exchange capacity. However, the high feature importance of CEC in Forest models coincided with Clay and Silt, suggesting the model is largely capturing the mineralogical capacity for stabilization (i.e., clay activity) rather than solely the auto-correlation with organic matter. Thus, CEC should be interpreted here as a proxy for the combined organo-mineral complex capacity. Our results confirm that the clay fraction is a dominant predictor, defining the soil’s “C saturation capacity”. Its role extends beyond passive protection; the high SSA of clay provides reactive surfaces essential for adsorbing and stabilizing microbial-derived compounds, primarily microbial necromass (a product of the Microbial Carbon Pump, or MCP) [21]. This process forms the most persistent C pool, MAOM and simultaneously, CEC acts as an active mediator of physico-chemical stabilization, promoting microaggregate formation and the subsequent physical occlusion of SOC from enzymatic attack. Extrinsic controllers (BIO12, BIO8) regulate the C-flux and its thermodynamic efficiency. Annual precipitation (BIO12) primarily governs C-input, not just via NPP, but more critically, through the flux of rhizodeposits (DOM). These labile exudates are the “fuel” for the MCP [68].

In contrast, the mean temperature of the wettest quarter (BIO8) represents the period of maximum decomposition potential. When moisture (BIO12) is not limiting, BIO8 takes control of microbial metabolism (Q10). High BIO8 values exponentially accelerate respiration and, critically, reduce microbial carbon use efficiency (CUE). This “thermodynamic penalty” creates a “leaky” system where a larger fraction of C is catabolically lost as CO2 before it can be anabolically incorporated into microbial biomass, the precursor to MAOM [69]. This has direct implications for Carbon Farming: practices like no-till or mulching are successful not only because they increase C-inputs, but primarily because they modify the soil microclimate [70,71]. By buffering temperature extremes, they increase CUE, shifting the microbial metabolism away from C-loss and towards C-stabilization. Our ML-CUE framework mandates a shift from ‘one-size-fits-all’ to pedogenetically informed C-farming. Mitigation must align with intrinsic capacity: high-capacity soils (high clay/CEC) are C-input-limited (requiring manure/cover crops), whereas low-capacity soils (e.g., coarse Fluvisols) need transformative amendments (e.g., biochar) to create new stabilization pathways [72]. The vulnerable C stocks in carbonate-rich soils (Leptosols, Regosols) necessitate a dual strategy: (1) sequestering C in degraded croplands (targeting SCSD) and (2) conserving high-risk grassland/forest stocks. Policy must treat C-stock vulnerability as a key risk metric, incentivizing conservation (e.g., no-till) as aggressively as sequestration. Key limitations define future research. A critical limitation of this study is the lack of spatially explicit data on farm management practices, specifically tillage intensity, crop rotations, and organic fertilization. As SOC dynamics in croplands are strongly influenced by these anthropogenic factors, often overriding climatic controls, their absence restricts the interpretation of the pure climatic effect and likely contributes to the unexplained variance in the cropland models. Furthermore, we analyzed total SOC, failing to differentiate transient POM from persistent MAOM, the only pool representing true, long-term sequestration [69,73,74,75]. Finally, while our ensemble modeling approach provides robust point-based predictions, future implementation for public policy (e.g., carbon credit verification) will require the integration of spatial uncertainty analysis (e.g., confidence intervals via BRNN) to ensure transparent risk assessment.

5. Conclusions

This study quantitatively confirms that the hierarchy of pedogenetic SOC controllers is fundamentally non-stationary, shifting according to the dominant biogeochemical regime imposed by LULC. We thus demonstrate that static models, which assume uniform predictor effects, are inherently flawed when assessing SOC across heterogeneous landscapes. Our methodological approach of LULC stratification was essential for accurately modeling the dominant process in each system: (1) RF was superior in forests, successfully capturing the complex, non-linear relationships of intrinsic pedology (CEC/pH) that define stabilization capacity; (2) CUB excelled in grasslands, proving most effective at modeling the climatic thresholds (Bio12/19) that regulate C-input kinetics via the MCP; (3) SVM provided the most robust results for croplands, successfully balancing the hybrid influence of remaining soil CEC and C-loss kinetics (Bio08). The primary applied conclusion is that the soil “C-ceiling” is not uniform. Consequently, high sequestration potential (a high SCSD) is not a feature of all degraded croplands, but is specific to croplands on soils with high intrinsic capacity (high CEC/Clay), where current SOC stocks are far below their mineral-defined “ceiling”. Low-capacity soils (e.g., Fluvisols, Albeluvisols) inherently offer low sequestration potential. Our analytical framework therefore provides an essential tool for spatially targeting Carbon Farming interventions toward locations with the highest return on investment for climate change mitigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.; methodology, L.G. and D.R.; software, D.R.; validation, L.G. and D.R.; formal analysis, L.G., M.J. and I.P.; investigation, L.G.; resources, L.G. and D.R.; data curation, D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G. and D.R.; writing—review and editing, L.G., M.J., I.P. and D.R.; visualization, D.R.; supervision, M.J.; project administration, I.P.; funding acquisition, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the scientific project “Prediction of maize yield potential using machine learning models based on vegetation indices and phenological metrics from Sentinel-2 multispectral satellite images (AgroVeFe)—581-UNIOS-30”, which was funded by the European union–NextGenerationEU.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. State of Knowledge of Soil Biodiversity—Status, Challenges and Potentialities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corvalan, C.; Hales, S.; McMichael, A.J. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; ISBN 1597260401. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, W.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liang, J.; Chang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; et al. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Wetlands and Regulating Strategies Response to Climate Change. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.I.D.; Brito, L.M.; Nunes, L.J.R. Soil Carbon Sequestration in the Context of Climate Change Mitigation: A Review. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Sun, T.; Pan, Z.; Lv, J.; Peňuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Xiao, K.Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.G. Rethinking Organic Carbon Sequestration in Agricultural Soils from the Elemental Stoichiometry Perspective. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2025, 31, e70319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, A.; Haritash, A.K. Climate-Smart Agriculture, Enhanced Agroproduction, and Carbon Sequestration Potential of Agroecosystems in India: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2025, 15, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehberger, E.; West, P.C.; Spillane, C.; McKeown, P.C. What Climate and Environmental Benefits of Regenerative Agriculture Practices? An Evidence Review. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 052001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, A.; Seidel, F.; Leifeld, J.; Kätterer, T.; Martin, M.; Pellerin, S.; Emde, D.; Seitz, D.; Chenu, C. Carbon Sequestration in Soils and Climate Change Mitigation—Definitions and Pitfalls. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30, e16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, M.; Ros, G.H.; Young, M.D.; de Vries, W. Global Variation in Soil Carbon Sequestration Potential through Improved Cropland Management. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28, 1162–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhorst, B.; Ottner, F. Polycyclic Luvisols in Northern Italy: Palaeopedological and Clay Mineralogical Characteristics. Quat. Int. 2003, 106–107, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, T.; Jiménez-Millán, J.; Sipos, P.; Abad, I.; Jiménez-Espinosa, R.; Szalai, Z. Effect of Pedogenic Clay Minerals on the Sorption of Copper in a Luvisol B Horizon. Geoderma 2011, 160, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. Mineral-Microbe Interactions: A Review. Front. Earth Sci. China 2010, 4, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeldt, T.; Schuth, S.; Häusler, W.; Wagner, F.E.; Kaufhold, S.; Overesch, M. Iron Oxide Mineralogy and Stable Iron Isotope Composition in a Gleysol with Petrogleyic Properties. J. Soils Sediments 2012, 12, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Li, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, P.; Liu, J.; Kou, W.; Huang, D.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X. New Insights into Organic Carbon Mineralization: Combining Soil Organic Carbon Fractions, Soil Bacterial Composition, Microbial Metabolic Potential, and Soil Metabolites. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalyna, W. Distribution of various forms of aluminum, iron and manganese in the Orthic Gray Wooded, Gleyed Orthic Gray Wooded and related Gleysolic soils in Manitoba. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1971, 36, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A.; Cloy, J.M.; Graham, M.C.; Hamlet, L.E. A Microanalytical Study of Iron, Aluminium and Organic Matter Relationships in Soils with Contrasting Hydrological Regimes. Geoderma 2013, 202–203, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.B.; Zaleski, T.; Józefowska, A.; Mazurek, R. Soil Formation on Calcium Carbonate-Rich Parent Material in the Outer Carpathian Mountains—A Case Study. Catena (Amst) 2019, 174, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggar, S.; Yeates, G.W.; Shepherd, T.G. Cultivation Effects on Soil Biological Properties, Microfauna and Organic Matter Dynamics in Eutric Gleysol and Gleyic Luvisol Soils in New Zealand. Soil Tillage Res. 2001, 58, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America and American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2018; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltr, V.; Menšík, L.; Hlisnikovský, L.; Hruška, M.; Pokorný, E.; Pospíšilová, L. The Soil Organic Matter in Connection with Soil Properties and Soil Inputs. Agronomy 2021, 11, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Microbial Necromass Contribution to Soil Organic Matter–Research Square. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-473688/v1 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Kästner, M.; Miltner, A.; Thiele-Bruhn, S.; Liang, C. Microbial Necromass in Soils—Linking Microbes to Soil Processes and Carbon Turnover. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 756378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Růžek, L.; Voříšek, K.; Strnadová, S.; Nováková, M.; Barabasz, W. Microbial Characteristics, Carbon and Nitrogen Content in Cambisols and Luvisols. Plant Soil Environ. 2004, 50, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenzind, T.; Mason-Jones, K.; Mansour, I.; Rillig, M.C.; Lehmann, J. Formation of Necromass-Derived Soil Organic Carbon Determined by Microbial Death Pathways. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, M.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Alexandrov, V.; Boberg, F.; Boroneant, C.; Christensen, O.B.; Formayer, H.; Orlowsky, B.; Stepanek, P. Observational Evidence for Soil-Moisture Impact on Hot Extremes in Southeastern Europe. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąb, T.; Pużyńska, K.; Pużyński, S.; Palmowska, J.; Kowalik, K. Effect of Organic Farming on a Stagnic Luvisol Soil Physical Quality. Geoderma 2016, 282, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, T.G.; Teixeira, R.F.M.; Domingos, T. Detailed Global Modelling of Soil Organic Carbon in Cropland, Grassland and Forest Soils. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinić, V.; Galović, L.; Husnjak, S.; Durn, G. Climate vs. Parent Material—Which Is the Key of Stagnosol Diversity in Croatia? Geoderma 2015, 241–242, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galić, L.; Vinković, T.; Ravnjak, B.; Lončarić, Z. Agronomic Biofortification of Significant Cereal Crops with Selenium—A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. WRB-IUSS World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In World Soil Resources Reports 106; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; ISBN 9789251083697. [Google Scholar]

- Panagos, P.; Van Liedekerke, M.; Borrelli, P.; Köninger, J.; Ballabio, C.; Orgiazzi, A.; Lugato, E.; Liakos, L.; Hervas, J.; Jones, A.; et al. European Soil Data Centre 2.0: Soil Data and Knowledge in Support of the EU Policies. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolbovoy, V.; Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. Carbon Sink Enhancement in Soils of Europe: Data, Modeling, Verification; OPOCE: Luxembourg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, P.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Hari, C.; Pellissier, L.; Karger, D.N. Global Climate-Related Predictors at Kilometer Resolution for the Past and Future. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 5573–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11464:2006; Soil Quality—Pretreatment of Samples for Physico-Chemical Analysis. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37718.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ISO 10694:1995; Soil Quality—Determination of Organic and Total Carbon After Dry Combustion (Elementary Analysis). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/18782.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ISO 10390:1994; Soil Quality—Determination of PH. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/18454.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ISO 14235:1998; Soil Quality—Determination of Organic Carbon by Sulfochromic Oxidation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/23140.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ISO 11277:2020; Soil Quality—Determination of Particle Size Distribution in Mineral Soil Material—Method by Sieving and Sedimentation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/69496.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Genuer, R.; Poggi, J.-M. Random Forests with R; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Syam, N.; Kaul, R. Chapter 5: Random Forest, Bagging, and Boosting of Decision Trees. In Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Marketing and Sales: Essential Reference for Practitioners and Data Scientists; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L.; Cutler, A.; Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. RandomForest: Breiman and Cutlers Random Forests for Classification and Regression. CRAN: Contributed Packages. 2002. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForest/index.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- John, K.; Kebonye, N.M.; Agyeman, P.C.; Ahado, S.K. Comparison of Cubist Models for Soil Organic Carbon Prediction via Portable XRF Measured Data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule- and Instance-Based Regression Modeling • Cubist. Available online: https://topepo.github.io/Cubist/ (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Montesinos López, O.A.; López, A.M.; Crossa, J. Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9783030890100. [Google Scholar]

- Karatzoglou, A.; Smola, A.; Hornik, K. Kernel-Based Machine Learning Lab [R Package Kernlab Version 0.9-33]. CRAN: Contributed Packages. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=kernlab (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Zhang, F.; O’Donnell, L.J. Support Vector Regression. In Machine Learning: Methods and Applications to Brain Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullachery, V.; Khera, A.; Husain, A. Bayesian Neural Networks. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Rodriguez, P.; Gianola, D. Bayesian Regularization for Feed-Forward Neural Networks [R Package Brnn Version 0.9.4]. CRAN: Contributed Packages. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=brnn (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Kiran, K.K.; Pal, S.; Chand, P.; Kandpal, A. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Sustainable Agricultural Practices to Mitigate Climate Change in Indian Agriculture: A Meta-Analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, P.; Mahalingappa, D.G.; Kaushal, R.; Bhardwaj, D.R.; Chakravarty, S.; Shukla, G.; Thakur, N.S.; Chavan, S.B.; Pal, S.; Nayak, B.G.; et al. Biomass Production and Carbon Sequestration Potential of Different Agroforestry Systems in India: A Critical Review. Forests 2022, 13, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lv, Y.; Xie, B.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Mei, T.; Li, Y.; Yuan, N.; Shi, Y. Topography and Soil Organic Carbon in Subtropical Forests of China. Forests 2023, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Romero, M.L.; Lozano-García, B.; Parras-Alcántara, L. Topography and Land Use Change Effects on the Soil Organic Carbon Stock of Forest Soils in Mediterranean Natural Areas. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 195, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Forest Soils and Carbon Sequestration. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 220, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Du, H.; Song, T.; Yang, Z.; Peng, W.; Gong, J.; Huang, G.; Li, Y. Conversion of Farmland to Forest or Grassland Improves Soil Carbon, Nitrogen, and Ecosystem Multi-Functionality in a Subtropical Karst Region of Southwest China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Reference Base for Soil Resources; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Paradelo, R.; Eden, M.; Martínez, I.; Keller, T.; Houot, S. Soil Physical Properties of a Luvisol Developed on Loess after 15 Years of Amendment with Compost. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 191, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Khan, I.M.; Shah, T.I.; Bangroo, S.A.; Kirmani, N.A.; Nazir, S.; Malik, A.R.; Aezum, A.M.; Mir, Y.H.; Hilal, A.; et al. Soil Microbiome: A Treasure Trove for Soil Health Sustainability under Changing Climate. Land 2022, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Joia, J. Microbes as Potential Tool for Remediation of Heavy Metals: A Review. J. Microb Biochem. Technol. 2016, 8, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.R.G.; Salomon, M.J.; Lowe, A.J.; Cavagnaro, T.R. Microbial Solutions to Soil Carbon Sequestration. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Goswami, M.P.; Bhattacharyya, L.H. Perspective of Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture under Changing Climatic Scenario: A Review. J. Phytol. 2016, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhade, A.; Wilkinson, E.; Britt, D.W.; Kaundal, A. Plant-Microbe Interactions in the Rhizosphere and the Role of Root Exudates in Chemical Signaling and Microbiome Engineering. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, J.; Hagn, L.; Mittermayer, M.; Hülsbergen, K.J. After Effects of Historical Grassland on Soil Organic Carbon Content and Plant Growth in Croplands in Southern Germany Determined Using Satellite Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, D.; Ballabio, C.; Lugato, E.; Fasiolo, M.; Jones, A.; Panagos, P. Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in European Croplands and Grasslands: How Much Have We Lost in the Past Decade? Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30, e16992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajda, A.M.; Czyż, E.A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A. Effects of Different Tillage Intensities on Physicochemical and Microbial Properties of a Eutric Fluvisol Soil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soucémarianadin, L.N.; Cécillon, L.; Guenet, B.; Chenu, C.; Baudin, F.; Nicolas, M.; Girardin, C.; Barré, P. Environmental Factors Controlling Soil Organic Carbon Stability in French Forest Soils. Plant Soil 2018, 426, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BALL, D.F. Loss-on-Ignition As an Estimate of Organic Matter and Organic Carbon in Non-Calcareous Soils. J. Soil Sci. 1964, 15, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, T.B.; Elberling, B.; de Neergaard, A.; Magid, J. Organic Carbon Dynamics in Different Soil Types after Conversion of Forest to Agriculture. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 26, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Luo, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Liu, J.; Jian, Z.; Xie, S.; Thomas, H.; Herndl, G.J.; et al. The Microbial Carbon Pump and Climate Change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Deb, S.; Sahoo, S.S.; Sahoo, U.K. Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon Stock and Its Relation with Climatic and Other Environmental Factors in Forest Ecosystems: A Review. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Bartkowski, B.; Dönmez, C.; Don, A.; Mayer, S.; Steffens, M.; Weigl, S.; Wiesmeier, M.; Wolf, A.; Helming, K. Carbon Farming: Are Soil Carbon Certificates a Suitable Tool for Climate Change Mitigation? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kaushal, R.; Kaushik, P.; Ramakrishna, S. Carbon Farming: Prospects and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, L.; Huang, W.; Zhao, L.; Cao, X. Biochar-Amended Soil Can Further Sorb Atmospheric CO2 for More Carbon Sequestration. Commun Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obasi, S.N.; Peters, O.A.; Tenebe, V.A.; Obasi, C.C.; Omodara, M.A. Role of Soil Microbial Diversity in Mitigating Soil-Borne Diseases and Postharvest Losses. Niger. Agric. J. 2024, 55, 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- Vahedi, R.; Rasouli-Sadaghiani, M.H.; Barin, M.; Vetukuri, R.R. Effect of Biochar and Microbial Inoculation on P, Fe, and Zn Bioavailability in a Calcareous Soil. Processes 2022, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, J.K.; Munch, J.C.; Fischer, W.R. Soil Microbial Properties and the Assessment of Available Soil Organic Matter in a Haplic Luvisol after Several Years of Different Cultivation and Crop Rotation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.