Analysis of Disinfectant Efficacy Against Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Surface and Method Effects in Greenhouse Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental and Computational Workflow for Lesion and Disease Severity Analysis

2.2. Reactivation and Maintenance of the Inoculum Source

2.3. Experimental Bioassay Design and Randomization for Evaluating Disinfectant Efficacy Against ToBRFV

2.4. Quantification of Leaf Lesion Severity Using Image Processing

2.5. Descriptive Evaluation Prior to Model Fitting

2.6. Statistical Modeling of Surface–Method Interactions

2.7. Bioassays to Assess the Efficacy of Disinfectants in Preventing Mechanical Transmission of ToBRFV to Tomato Plants

3. Results

3.1. Bioassays Reveal Surface and Method-Specific Differences in Disinfectant Efficacy

3.2. Quantitative and Dose-Dependent Evaluation of Disinfectant Efficacy Against ToBRFV

3.2.1. Lesion Count and Symptom Severity as Indicators of Transmission Efficiency

3.2.2. Comparative Performance of Disinfectant Formulations and Application Doses

3.2.3. Dose–Response Relationships Between Disinfectant Concentration and ToBRFV Infection

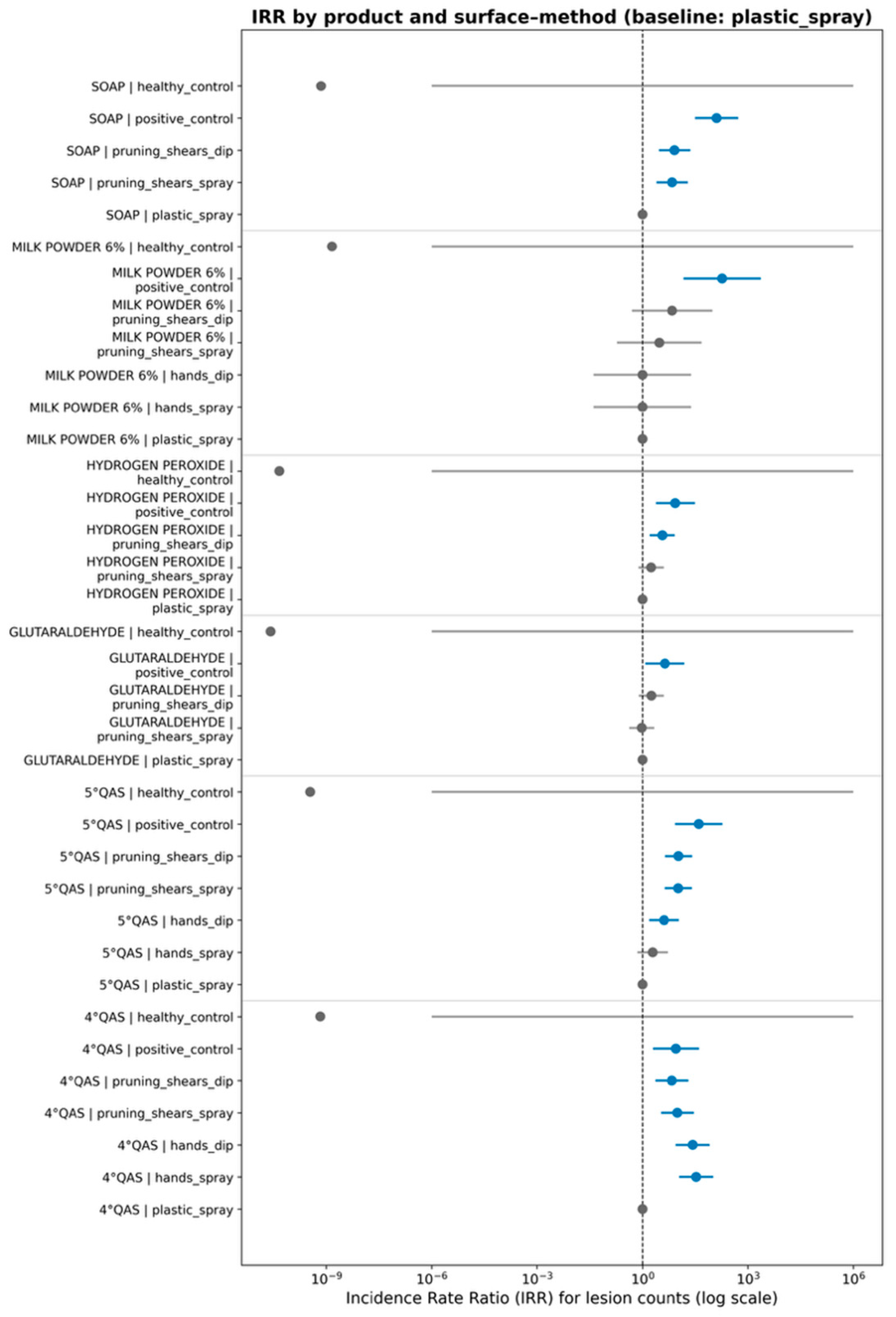

3.3. Multivariate Modeling of Surface–Method Interactions and Dose-Dependent Disinfection Dynamics

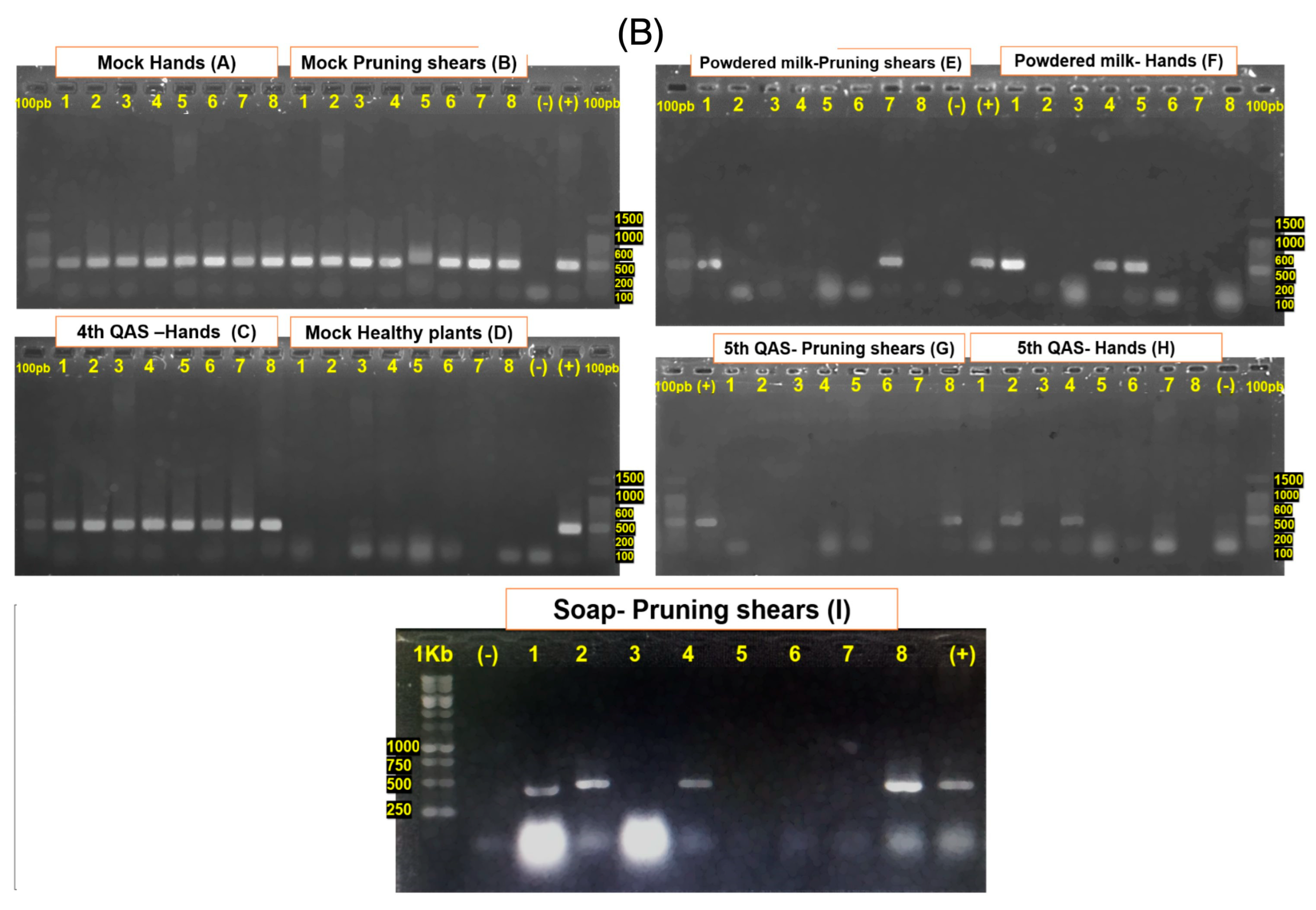

3.4. Bioassays to Evaluate the Efficacy of Disinfectant Products on Tomato Plants

4. Discussion

4.1. Glutaraldehyde and 5°QACs Achieve the Highest ToBRFV Inactivation, Driven by Surface and Application Method

4.2. Dose–Response Analysis Reveals Rapid Saturation for Glutaraldehyde and QACs with Extremely Low ED50 Values

4.3. Concordant Outcomes in Nicotiana rustica and Tomato Demonstrate Strong Predictive Power for Systemic ToBRFV Infections

4.4. Effective ToBRFV Control Requires Surface- and Method-Specific Sanitation Strategies in Greenhouse Systems

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salem, N.; Mansour, A.; Ciuffo, M.; Falk, B.W.; Turina, M. A new tobamovirus infecting tomato crops in Jordan. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidan, H.; Pelin, S.; Kübra, Y.; Bengi, T.; Gözde, E.; Özer, C. Robust molecular detection of the new Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in infected tomato and pepper plant from Turkey. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Da, L.D.; Panattoni, A.; Salemi, C.; Cappellini, G.; Bartolini, L.; Parrella, G. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Tomato and Pepper Seeds by RT-LAMP (real-time and visual) and Comparison with RT-PCR end-point and RT-qPCR methods. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 640932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrón-Crisantos, J.M.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, J.; Valencia-Luna, J.B.; Alcasio-Rangel, S.; García-Ávila, C.J.; López-Buenfil, J.A.; Ochoa-Martínez, D.L. Primer reporte de Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) en Michoacán, México. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2019, 37, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.M.; Sulaiman, A.; Samarah, N.; Turina, M.; Vallino, M. Localization and Mechanical Transmission of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Tomato Seeds. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mejía, P.; Rodríguez-Gómez, G.; Salas-Aranda, D.A.; García-López, I.J.; Pérez-Alfaro, R.S.; De Dios, E.Á.; Vučurović, A. Identification and management of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in greenhouses in Mexico. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandte, M.; Ehlers, J.; Nourinejhad, Z.S.; Büttner, C. A Combined Cleaning and Disinfection Measure to Decontaminate Tire Treads from Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus. Hygiene 2024, 4, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.; Frew, L.; Ward, R.; Hodgson, R.; Forde, S.; McDonough, S.; Webster, G.; Chisnall, K.; Mynett, M.; Buxton-Kirk, A.; et al. Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Survival and Disinfection Efficacy on Common Glasshouse Surfaces. Viruses 2023, 15, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molad, O.; Smith, E.; Luria, N.; Bakelman, E.; Lachman, O.; Reches, M.; Dombrovsky, A. Studying Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus Longevity in Soil and Virion Susceptibility to pH-Treatments Helped Improve Virus Control by Soil Disinfection. Plant Soil 2024, 505, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, F.H.H.; Becker, B.; Todt, D.; Steinmann, E.; Steinmann, J. Virucidal efficacy of glutaraldehyde for instrument disinfection. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2020, 15, Doc34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandie, C.E.; Ogunniyi, A.D.; Ferro, S.; Hall, B.; Drigo, B.; Chow, C.W.K.; Venter, H.; Myers, B.; Deo, P.; Donner, E.; et al. Disinfection options for irrigation water: Reducing the risk of fresh produce contamination with human pathogens. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 50, 2144–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.; Nourinejhad Zarghani, S.; Kroschewski, B.; Büttner, C.; Bandte, M. Decontamination of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV) on shoe soles: Efficacy of cleaning and disinfectant measures. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springthorpe, V.S.; Sattar, S.A. Carrier tests to assess microbicidal activities of chemical disinfectants for use on medical devices and environmental surfaces. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Lim, J.Y.C.; Xue, K.; Yew, P.Y.M.; Owh, C.; Chee, P.L.; Loh, X.J. Sanitizing agents for virus inactivation and disinfection. View 2020, 1, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Baysal-Gurel, F.; Abdo, Z.; Miller, S.A.; Ling, K.S. Evaluation of Disinfectants to Prevent Mechanical Transmission of Viruses and a Viroid in Greenhouse Tomato Production. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.-S.; Gilliard, A.C.; Zia, B. Disinfectants Useful to Manage the Emerging Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Greenhouse Tomato Production. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Shamimuzzaman, M.; Gilliard, A.C.; Ling, K.-S. Effectiveness of Disinfectants against the Spread of Tobamoviruses: Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus and Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.-H. Review of Disinfection and Sterilization–Back to the Basics. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 50, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kchaou, M.; Abuhasel, K.; Khadr, M.; Hosni, F.; Alquraish, M. Surface Disinfection to Protect against Microorganisms: Overview of Traditional Methods and Issues of Emergent Nanotechnologies. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.; Caruso, G.A.; Stefano, B.; Lo Bosco, G.; Ezequiel, R.A.; Salvatore, D. Spread of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in Sicily and evaluation of the spatiotemporal dispersion in experimental conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, N.; Bačnik, K.; Bajde, I.; Brodarič, J.; Fox, A.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, I.; Vučurović, A. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in aqueous environments—survival and significance of water-mediated transmission. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1187920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gilliard, A.C.; Ling, K.-S. Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus Is Transmissible through a Greenhouse Hydroponic System but May Be Inactivated by Cold Plasma Ozone Treatment. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelshafy, A.M.; Neetoo, H.; Al-Asmari, F. Antimicrobial activity of hydrogen peroxide for application against norovirus and other pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1456213. [Google Scholar]

- Copes, W.E.; Ojiambo, P.S. A Systematic Review and Quantitative Synthesis of the Efficacy of Quaternary Ammonium Disinfestants Against Fungal Plant Pathogens. Crop Prot. 2023, 164, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Kaur, K. Quaternary ammonium disinfectants: Current practices and future perspective. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 136, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghani, N.S.; Ehlers, J.; Monavari, M.; von Bargen, S.; Hamacher, J.; Büttner, C.; Bandte, M. Applicability of Different Methods for Quantifying Virucidal Efficacy Using MENNO Florades and Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus as an Example. Plants 2023, 12, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabenau, H.F.; Steinmann, J.; Rapp, I.; Schwebke, I.; Eggers, M. Evaluation of a virucidal quantitative carrier test for surface disinfectants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Evaluating the Virucidal Activity of Disinfectants According to European Union Standards. Viruses 2021, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, C.I.; Zamora-Macorra, E.J.; Ochoa-Martínez, D.L.; González Garza, R. Disinfectants effectiveness in Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) transmission in tobacco plants. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2022, 40, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Macorra, E.J.; Ochoa-Martínez, D.L.; Chavarín-Camacho, C.Y.; Hammond, R.W.; Aviña-Padilla, K. Genomic insights into host-associated variants and transmission features of a ToBRFV isolate from Mexico. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1580000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; Hamilton, P.W. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.; Silva, M.; Grácio, M.; Pedroso, L.; Lima, A. Milk Antiviral Proteins and Derived Peptides against Zoonoses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, E.; Terpstra, P.; Koopmans, M.; Duizer, E. Virucidal efficacy of hydrogen peroxide vapour disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 80, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintermantel, W.M. A comparison of disinfectants to prevent spread of potyviruses in greenhouse tomato production. Plant Health Prog. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, A.; Puscas, C.; Patrascu, I.; Lehene, M.; Ziebro, J.; Scurtu, F.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R. Stability of Glutaraldehyde in Biocide Compositions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, G.; Russell, A.D. Antiseptics and disinfectants: Activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerba, C.P. Disinfection. In Environmental Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Pepper, I.L., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, NL, USA, 2015; pp. 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; Thomas, B.C.; Conly, J.; Lorenzetti, D. Cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in hospitals and long-term care facilities for reducing hospital- and facility-acquired bacterial and viral infections: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 122, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Choi, D.H.; Choi, H.J.; Park, D.H. Risk of Erwinia amylovora transmission in viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state via contaminated pruning shears. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 165, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G. Efficacy of ethanol against viruses in hand disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 98, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, B.A.; Kehoe, M.A.; Jones, R.A.C. Zucchini yellow mosaic virus: Contact Transmission, Stability on Surfaces, and Inactivation with Disinfectants. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, I.M.; Lapidot, M.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Emerging viral diseases of tomato crops. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, H.R.; Blackwell, J.H. Survival of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus in Casein and Sodium Caseinate Produced from the Milk of Infected Cows. J. Food Prot. 1977, 40, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierska, K.; Kalinowska-Lis, U. Milk Proteins—Their Biological Activities and Use in Cosmetics and Dermatology. Molecules 2021, 26, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Pesticide Residues in Food: Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues—Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090187 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Holmes, F.O. Local Lesions in Tobacco Mosaic. Bot. Gaz. 1929, 87, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, L. Epidemiology and control of Tomato mosaic virus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1976, 14, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitzky, N.; Smith, E.; Lachman, O.; Luria, N.; Mizrahi, Y.; Bakelman, H.; Sela, N.; Laskar, O.; Milrot, E.; Dombrovsky, A. The bumblebee Bombus terrestris carries a primary inoculum of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus contributing to disease spread in tomatoes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R. Plant Virology, 5th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-384871-0. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Parrella, G.; Rizzo, R.; Davino, S.; Panno, S. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: A pathogen that is changing the tomato production worldwide. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2022, 181, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt, T.; Britz, B.; Kleinow, T.; Hipp, K.; Eber, F.J.; Wege, C. Getting Hold of the Tobamovirus Particle—Why and How? Purification Routes over Time and a New Customizable Approach. Viruses 2024, 16, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Griffiths, J.; Marchand, G.; Bernards, M.; Wang, A. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: An emerging and rapidly spreading plant RNA virus that threatens tomato production worldwide. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- kap8416. DisinfectantsToBRFV [GitHub Repository]. GitHub. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/kap8416/DisinfectantsToBRFV (accessed on 19 November 2025).

| Product | Virion Inactivation Percentage. Range and Average Values | Application Method with Highest Efficacy | Surface Type Retaining the Highest Active Virion Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powdered milk | 96–99.98% | Spraying | Pruning shears |

| Soap | 89–99.96% | Spraying | Pruning shears |

| 5°QAS | 47–97.85% | Spraying | Pruning shears |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | 13–98.75% | Spraying | Pruning shears |

| Glutaraldehyde | 9–97.71% | Spraying | Pruning shears |

| 4°QAS | 22–66.35% | Spraying | Hands |

| Treatment | First Symptom Appearance (dpi) | Number of RT-PCR Positive/Negative Plants at 25 dpi | Percentage of Infected Plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powdered milk 6%—Hands | 11 | 3/5 | 37.5% |

| Powdered milk 6%—Pruning shears | 11 | 2/6 | 25% |

| 4°QAS 150 ppm—Hands (Anglosan Cl®) | 11 | 8/0 | 100% |

| 5°QAS 150 ppm. Hands | 11 | 2/6 | 25% |

| 5°QAS 400 ppm. Pruning shears (Sany Green®) | 11 | 1/7 | 12.5% |

| Soap 15 mL/L. Pruning shears (Bio Any Gel®) | 11 | 4/4 | 50% |

| Infected. Mock-treatment. Hands | 6 | 8/0 | 100% |

| Infected. Mock-treatment. Pruning shears | 7 | 8/0 | 100% |

| Healthy. Mock-inoculated control | - | 0/8 | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zamora-Macorra, E.J.; Merino-Domínguez, C.L.; Ramos-Villanueva, C.; Mendoza-Espinoza, I.M.; Cadenas-Castrejón, E.; Aviña-Padilla, K. Analysis of Disinfectant Efficacy Against Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Surface and Method Effects in Greenhouse Production. Agronomy 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010015

Zamora-Macorra EJ, Merino-Domínguez CL, Ramos-Villanueva C, Mendoza-Espinoza IM, Cadenas-Castrejón E, Aviña-Padilla K. Analysis of Disinfectant Efficacy Against Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Surface and Method Effects in Greenhouse Production. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleZamora-Macorra, Erika Janet, Crystal Linda Merino-Domínguez, Carlos Ramos-Villanueva, Irvin Mauricio Mendoza-Espinoza, Elizabeth Cadenas-Castrejón, and Katia Aviña-Padilla. 2026. "Analysis of Disinfectant Efficacy Against Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Surface and Method Effects in Greenhouse Production" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010015

APA StyleZamora-Macorra, E. J., Merino-Domínguez, C. L., Ramos-Villanueva, C., Mendoza-Espinoza, I. M., Cadenas-Castrejón, E., & Aviña-Padilla, K. (2026). Analysis of Disinfectant Efficacy Against Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Surface and Method Effects in Greenhouse Production. Agronomy, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010015