Abstract

Distant hybridization between bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and wild Aegilops species is a valuable approach to take to broaden genetic diversity, but it is frequently impeded by reproductive barriers. This study evaluated crossability, pollen tube dynamics, meiotic behavior, somatic chromosome numbers, and pollen fertility in twelve Kazakh wheat cultivars crossed with Ae. triaristata Willd., Ae. cylindrica Host, Ae. triuncialis L., and Ae. squarrosa L. under field-based controlled pollination. Hybridization success varied significantly among combinations, with Ae. triaristata showing the highest compatibility (26.0% in Bezostaya 1 × Ae. triaristata), while Ae. squarrosa produced the lowest seed set. In compatible crosses, pollen tubes reached the ovary within 20–30 min, whereas delayed elongation (>60 min) was associated with fertilization failure. Meiotic analysis revealed incomplete homologous pairing (3–7 bivalents per PMC) and high abnormality rates (>90%). Somatic chromosome counts (2n) of selected F1 hybrids confirmed extensive aneuploidy and partial chromosome elimination. Pollen fertility was generally below 20%. These results identify Ae. triaristata as a promising donor species for pre-breeding in Kazakhstan and underscores the importance of integrating classical cytology with molecular approaches to overcome hybridization barriers.

1. Introduction

Kazakhstan is emerging as a major global wheat supplier, with its total wheat production reaching an estimated 18.6 million tons in 2024, marking a decade-high and approximately 40% above the five-year average [1]. Wheat exports are anticipated to reach approximately 10 million tons in 2024/25, highlighting the necessity of maintaining productivity and boosting resilience to climatic and biotic challenges. Furthermore, the wild relatives of wheat, particularly Aegilops species, offer crucial genetic resources for enhancing stress tolerance and disease resistance.

Aegilops tauschii—the donor of wheat’s D-genome—has contributed substantially to modern wheat improvement [2]. Other Aegilops species (e.g., Ae. triaristata, Ae. cylindrica, Ae. triuncialis, Ae. squarrosa) harbor additional drought, salinity, and pathogen-resistance traits, but exhibit strong reproductive incompatibility, limiting their use in breeding [3]. These incompatibilities arise from both prezygotic (pollen-pistil incompatibility) and postzygotic barriers (hybrid sterility and endosperm failure) [4].

Kazakhstan already has strong work on Aegilops-based introgressive forms and their agronomic/stress traits, but most of those studies start from later generations (F7–F10, 2n = 42 lines) and concentrate on productivity, quality, and stress tolerance.

The present study is one of the first to provide a systematic, multi-stage analysis of the reproductive barriers in F1 hybrids, specifically with Kazakh cultivars and multiple Aegilops species. We assessed key reproductive stages, including fertilization dynamics, meiotic behavior, somatic chromosome number, microsporogenesis, and pollen fertility to identify compatible combinations and support strategic pre-breeding approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The research involved distant hybridization between twelve winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars of Kazakh origin—Alma-Atinskaya semi-dwarf, Karlygash, Steklovidnaya 24, Mironovskaya 808, Bezostaya 1, Zhetisu, Progress, Dneprovskaya 221, Krasnovodopadskaya 210, Erythrospermum 350, Kharkovskaya 46, and Novomichurnika—and four wild Aegilops species: Ae. triaristata Willd., Ae. cylindrica Host, Ae. triuncialis L., and Ae. squarrosa L.

Seeds of the cultivated wheat varieties were obtained from the National Genebank, Kazakh Research Institute of Agriculture and Plant Growing (Almaty, Kazakhstan). Wild Aegilops accessions were obtained from the N.I. Vavilov All-Russian Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR), St. Petersburg, Russia, and were originally collected from Kazakhstan and neighboring Central Asian regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key morphological and ecological characteristics of wild Aegilops L. species in distant hybridization with Kazakh wheat varieties.

The table summarizes the key morphological and ecological characteristics of the Aegilops species examined in this study. Information was compiled from VIR germplasm descriptors, ICARDA genebank documentation, and FAO crop descriptor records. Morphological features include spikelet structure, awn arrangement, and phenology, while the ecological descriptors reflect the typical habitats of these taxa in Kazakhstan and surrounding regions.

Importantly, each Aegilops species carries valuable adaptive traits that are relevant to wheat improvement: Ae. triaristata provides drought tolerance, winter hardiness, and disease resistance, Ae. triuncialis contributes alleles for aridity adaptation and performance on nutrient-poor soils, Ae. cylindrica is a source of salinity and waterlogging tolerance, and Ae. squarrosa (syn. Ae. tauschii), the donor of the wheat D-genome, carries numerous disease resistance and abiotic stress-tolerance genes. These characteristics highlight their strategic importance for broadening the genetic base of Kazakh wheat and for evaluating compatibility in distant hybridization efforts.

2.2. Field Location and Climate

All field-grown wheat plants were cultivated at the experimental station of Kazakh Research Institute of Agriculture and Plant Growing in Almalybak (Almaty region, Kazakhstan—43.206° N, 76.708° E), which is in the foothills of the Alatau mountains (25 km west of Almaty city, with an altitude of 740 m above sea level). The site is characterized by a continental climate (Koppen BSk) and experiences snow cover in winter, which is 15–20 cm. In summer, the temperature rises to +40 °C. The annual precipitation is 332–645 mm. The period of abundant moisture occurs in March–June. The soil is classified as a gray-chestnut clay, with a 1.7 to 3.0% humus content. The total nitrogen content of the soil is 2%, the phosphorus content −0.16%, and the potassium content is 2.0%. The depth of groundwater varies from 5 to 30 m.

Planting and Growth Conditions

Seeds of all parental Triticum aestivum cultivars and Aegilops accessions were sown in open-field plots at the Almalybak Experimental Station in the middle of the autumn, coinciding with the regional planting window for winter wheat in the Almaty region. Sowing was carried out manually in 1.5 m × 2.0 m field plots, with 30 cm row spacing and 10–12 cm plant spacing within rows. Each cultivar × species combination was grown in three replicated plots under identical management conditions.

Supplemental irrigation was applied twice during early tillering (Zadoks 21–25) to ensure uniform establishment, while no irrigation was applied after stem elongation, following standard regional wheat management. No fertilizers were added during the growing season, in accordance with the experimental design of assessing hybridization performance under low-input field conditions. Weeds were removed manually every 2–3 weeks to prevent competition and maintain equal growing conditions across the replicates. No chemical pesticides or herbicides were used.

Plants entered stem elongation in late April, and heading occurred in the middle of May, depending on the genotype. Flowering and anthesis took place during Zadoks growth stages 60–65, typically close to the end of May, during which emasculation and controlled pollination were performed. Emasculation of wheat spikes was conducted when the spike had emerged approximately 2–3 cm from the flag leaf sheath (Zadoks 51–55), before anther dehiscence, while pollinations were carried out 2–3 days later during peak stigma receptivity.

2.3. Hybridization Procedure

Hybridization was performed under controlled pollination conditions at the Almalybak experimental station. The hybridization workflow followed the methodology of the N.I. Vavilov Institute (VIR). Emasculation and pollination were carried out in the open field, but spikes were covered with parchment isolation bags to prevent unintended cross-pollination. Spikes of the female parent were emasculated when they protruded 2–3 cm from the flag leaf sheath, a stage at which the male anthers were still green and underdeveloped, while the female florets were not yet receptive. From the central portion of each spike, three anthers were carefully removed from 20–22 florets by using sterilized tweezers to avoid damage to the pistils. After 2–3 days, pollen from the selected Aegilops donor was applied to the receptive stigmas. Pollinations were conducted in the morning between 09.00–11.00 am, when pollen viability was optimal [4,5,6,7].

2.4. Cytoembryological Studies

Pollinated florets were collected at defined intervals after fertilization for cytological analysis. The samples were fixed in Carnoy’s solution (absolute alcohol/chloroform/glacial acetic acid, 6:3:1 v/v/v) for 24 h and then transferred to 75% ethanol for storage until the start of the analysis. Charocco, Schiff’s reagent, and methyl green–pyronin methods were selected for their proven reliability in visualizing pollen tube growth, sperm cell differentiation, embryo sac structure, and early endosperm development. While more modern cytogenetic techniques, such as fluorescence and genomic in situ hybridization (FISH, GISH), offer high resolution, these classical methods remain affordable and accessible for the breeding process in the field or in the regional laboratory conditions. Staining and cytoembryological procedures followed established cytological protocols [8,9,10].

2.5. Chromosome Pairing and Meiosis Analysis

The chromosome pairing process was assessed in pollen mother cells at the first metaphase. The number of the bivalents in each cell was recorded, and the frequency of pairing classes (from 3 to 7 bivalents) was calculated. Chromosome lagging, genome loss, anaphase or telophase bridges, and irregular cytokinesis (pentads and hexads) abnormalities were quantified. Meiotic chromosome pairing and chromosome behavior at metaphase I were evaluated following established cytogenetic procedures for wheat × Aegilops hybrids [5,11,12].

2.6. Fertility Assessment

Pollen fertility was assessed by staining matured pollen grains with acetocarmine and scoring the proportion of commonly developed pollen against sterile pollen. After the anthers were stained, they were placed on a glass slide for examination. A drop of 25% acetic acid was added, covered with a coverslip, crushed, and placed on the microscope stage. Further studies were carried out using an MBI-6 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The percentage of the seed set was calculated as the number of grains that formed per total pollinated florets. Pollen viability was evaluated using acetocarmine staining based on standard cytological procedures [5,13].

2.7. Somatic Chromosome Number Analysis

Somatic chromosome counts were performed in root tip meristems of selected F1 hybrids to complement meiotic observations. Seeds of hybrids (Bezostaya 1 × Ae. triaristata; Karlygash × Ae. cylindrica; Progress × Ae. triaristata; Steklovidnaya 24 × Ae. cylindrica) were germinated on moist filter paper at 22 °C. Root tips (1–1.5 mm) were pre-treated in 0.002 M 8-hydroxyquinoline for 3 h at 4 °C, fixed in Carnoy’s solution (ethanol/acetic acid, 3:1 v/v) for 24 h, hydrolyzed in a 1N HCl at 60 °C for 7 min, then stained with Feulgen reagent, and squashed in 45% acetic acid. At least 25 well-spread metaphases per hybrid were examined at 1000× magnification (Leica DM 500, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Chromosome numbers were recorded and classified as euploid (expected 2n = 42), aneuploid (±1–10 chromosomes), or partial elimination (loss > 10 chromosomes) [5,14,15].

2.8. Microscopy and Data Collection

Pollen tube growth and fertilization stages were examined under a light microscope (Leica DM500) at magnifications of 70× and 400×, using methyl green–pyronin, Trevanne–Charocco, and Felgen–Fuchs acid stains. Meiotic stages were assessed in pollen mother cells at metaphase I, and the number of bivalents was recorded. At least 300 pollen mother cells per hybrid combination were analyzed for chromosome pairing and meiotic irregularities. Microscopic examination of the pollen tube growth, fertilization stages, and meiotic cells followed standard plant cytology protocols [5,16,17,18].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The experiment followed a completely randomized design (CRD), with three biological replicates per cross. Data received from the analysis were assessed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (HSD) for the mean separation at ρ ≤ 0.05. For each cross combination, emasculation and pollination were performed on 20–25 spikes per replicate, with three biological replicates. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA 14 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hybridization Success Rates

The process of distant hybridization in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) involves specific biological constraints due to strong pre- and post-fertilization barriers. Over several years, our hybridization program tested 10 Aegilops species that were sourced from diverse geographical origins: Ae. triaristata Willd., Ae. triuncialis L., Ae. cylindrica Host, Ae. ovata L., Ae. ventricosa Tausch, Ae. squarrosa L., Ae. crassa Boiss., Ae. aucheri L., Ae. tauschii Coss., and Ae. speltoides Tausch.

Despite the breadth of species examined, only four—Ae. triaristata Willd., Ae. triuncialis L., Ae. cylindrica Host, and Ae. squarrosa L.—produced viable hybrid seeds at levels suitable for further study. The viable hybrid seed set (%) was calculated as the proportion of pollinated florets that successfully formed grains, providing a direct measure of crossability for each Triticum aestivum × Aegilops combination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of hybridization of hexaploid (2n = 42) and tetraploid (2n = 28) cultivated wheat varieties with wild Aegilops species.

Hybridization success varied widely across combinations, with Ae. Triaristata showing the highest compatibility (up to 26% in Bezostaya 1 × Ae. triaristata) and Ae. Squarrosa showing the lowest (<7%).

A comparable compatibility was observed in Bezostaya 1 × Ae. cylindrica Host (24.3 ± 1.02%). Other combinations with Ae. triaristata, such as Karlygash, Alma-Atinskaya, and Novomichurinka, also produced a moderate seed set (17.2–20.8%), while Mironovskaya 808, Krasnovodopadskaya 210, and Steklovidnaya 24 showed much lower rates (6.2–7.8%).

For Ae. triuncialis, the most compatible combination was Novomichurinka × Ae. triuncialis (20.8 ± 1.7%), while Karlygash, Progress, and Bezostaya 1 also yielded high success rates (>18%). Conversely, Ae. squarrosa crosses generally resulted in a low seed set (<7%), reflecting strong postzygotic incompatibility, in agreement with cytogenetic studies showing limited homoeologous pairing between Ae. squarrosa chromosomes and wheat D-genome chromosomes [19,20].

These patterns align with global reports that show wide variations in crossability depending on the cultivar genotype, ploidy compatibility, and crossability genes (Kr1, Kr2) [21,22].

The superior performance of Ae. triaristata suggests that it may serve as a priority donor species for introducing stress tolerance and disease resistance traits into Kazakh wheat germplasm.

3.2. Pollen Tube Growth and Fertilization Anomalies

The elongation of the pollen sac along the tube is crucial in the process of producing future progeny from the wheat crop, with the formation of a fertilized grain being closely linked to this phase. As indicated in Table 2, the hybridization process between the generative cells of female and male plants did not yield a notably high percentage.

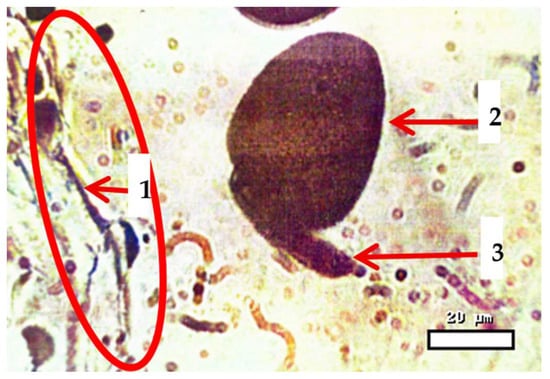

In compatible combinations, pollen tubes reached the ovary within 20–30 min (Figure 1), which is consistent with the optimal timeframe reported for successful fertilization in cereals [17].

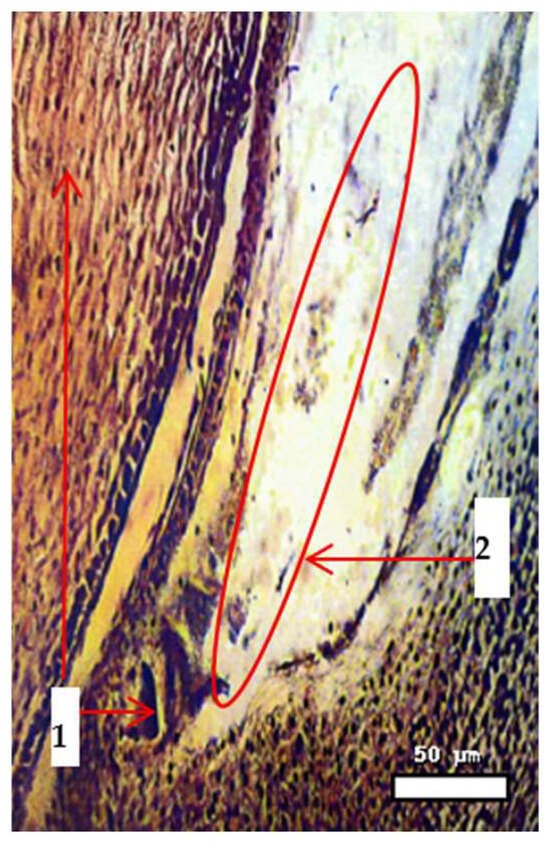

Figure 1.

Pollen tube growth of Aegilops triaristata Willd. in the Alma-Atinskaya semi-dwarf wheat variety, reaching the ovary 25 min after pollination. Stained with methyl green–pyronin; magnification 400×. Scale bar = 20 µm. Note: 1—mouth of the mother flower bud; 2—stamen pollen tube; 3—pollen tube growth.

Under microscopic examination, the growth of pollen tubes in a flower bud of wheat (Triticum aestivum) during distant hybridization can be observed. The entrance of the mother flower bud (left) is visible, with pollen tubes from the stamen infiltrating the maternal tissue. The growth of pollen tubes is oriented towards the ovule via the transmitting tissue, facilitating the transfer of sperm cells to the embryo sac. This phase is crucial for achieving successful fertilization and plays a key role in determining the efficiency of hybridization in wheat breeding initiatives.

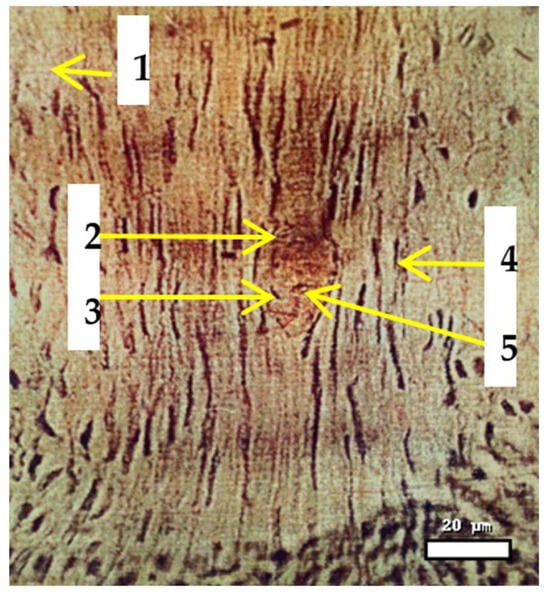

In incompatible combinations, elongation was significantly delayed, with some requiring more than 60 min to reach the ovary (Figure 2). This is often accompanied by swelling, branching, or stagnation.

Figure 2.

Pollen tube swelling of Aegilops triaristata Willd., 60 min after pollination of the wheat cultivar Karlygash. Stained with methyl green–pyronin; magnification 400×. Scale bar = 20 µm. Note: 1—pollen mouth (tissue); 2—pollen tube development; 3—vegetative sperm; 4—the stamen of a variety, through which the pollen tube passes; 5—generative sperm.

A microscopic examination reveals the development of pollen tubes and the differentiation of sperm cells in wheat (Triticum aestivum) during distant hybridization. The upper portion displays the pollen mouth (tissue), while the pollen tube traverses through the stamen tissue toward the ovule. Within the pollen tube, vegetative sperm and generative sperm cells can be identified, with the vegetative sperm facilitating the tube’s growth and the generative sperm dividing to create two male gametes for double fertilization. This specific structural configuration guarantees the precise targeting of sperm cells to the embryo sac, which is vital for successful fertilization in interspecific wheat crosses.

Delays resulted in the degeneration of the embryo sac before successful double fertilization—consistent with previous reports of pollen—pistil incompatibility in wheat × Aegilops crosses [23].

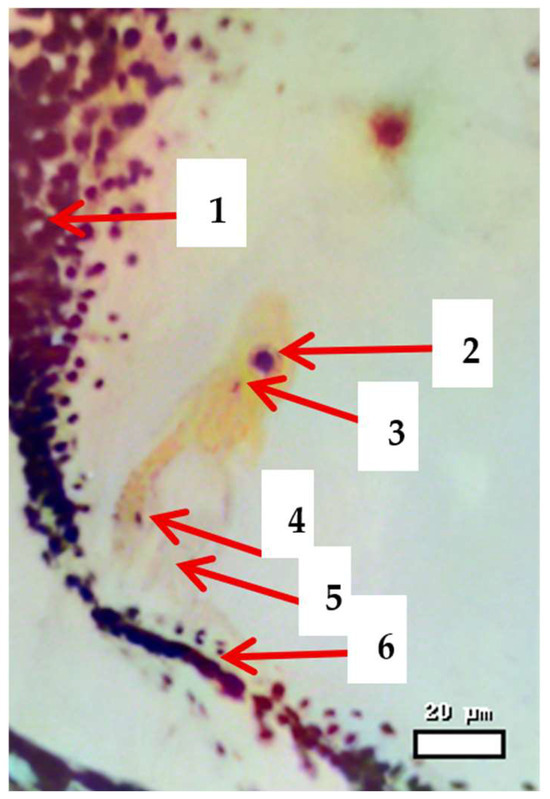

Abnormal fertilization patterns, such as incomplete double fertilization (fertilization of only the egg or central cell, or vice versa) and premature tube rupture, were observed in several wheat × Aegilops combinations. For example, in Progress × Ae. triaristata Willd., sperm entry into the embryo sac was delayed by 1.5 h, and the fusion of gametes occurred 2–3 h post-pollination (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of two spermatozoa in the egg cell and the central nucleus of the wheat variety Progress, 2 h 30 min after pollination. Stained with methyl green (Trevanne–Charocco method); magnification 400×. Scale bar = 20 µm. Note: 1, 6—the uterus; 2—the central core; 3—vegetative sperm; 4—generative sperm; 5—egg cell.

The illustration depicts the uterus (maternal tissue) surrounding the essential reproductive structures. The egg cell is located next to the entrance of the pollen tube, which carries the vegetative sperm and the generative sperm. The vegetative sperm directs the growth of the pollen tube, whereas the generative sperm is involved in double fertilization. One sperm fuses with the egg cell to create the zygote, and the other fuses with the central core to form the endosperm. This configuration emphasizes the collaborative interaction between male and female gametes that is necessary for successful seed development in interspecific crosses.

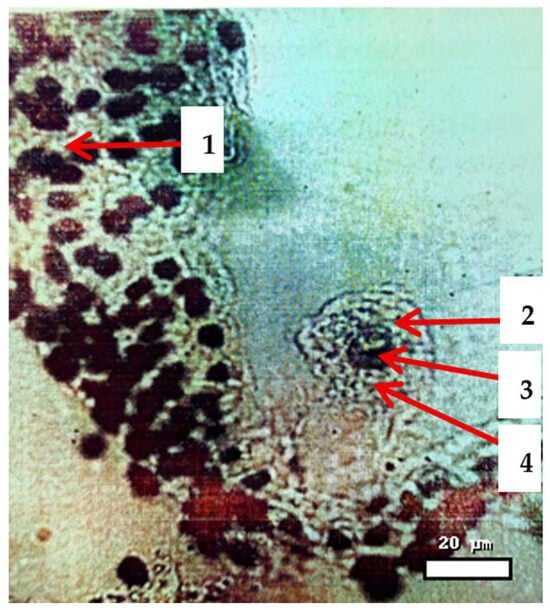

Similarly, in Steklovidnaya 24 × Ae. cylindrica Host crosses, only one sperm cell successfully fertilized the egg cell, with no fertilization of the central cell (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Penetration of sperm from Aegilops cylindrica into the egg cell of wheat variety Steklovidnaya 24, observed 2 h 30 min after pollination. Stained with Feulgen–Fuchs acid; magnification 400×. Scale bar = 20 µm. Note: 1—the uterus; 2—egg cells; 3—the nucleus of an egg cell; 4—sperm penetration into the nucleus of the egg cell.

These cases typically resulted in abnormal endosperm development and early embryo abortion. This is consistent with previous reports that disruptions in endosperm formation are a major cause of incompatibility in wheat × Aegilops crosses [5,7].

The development of the first endosperm cells was observed within 2–3 h under optimal conditions (18–20 °C), and the transition from the nuclear to the cellular state occurred by 4–5 h in Bezostaya 1 × Ae. cylindrica Host combinations. In Progress × Ae. triaristata Willd., this transition occurred sooner (Figure 5), suggesting genotype-specific differences in early endosperm development.

Figure 5.

Germ sac of Progress × Aegilops triaristata Willd., showing early endosperm development 4 h after pollination. Stained with Trevanne–Charocco; magnification 70×. Scale bar = 50 µm. Note: 1—mother flower; 2—delayed development of embryo and endosperm cells in the mother cell.

Microscopic examination reveals the penetration of sperm into the nucleus of the egg cell in wheat (Triticum aestivum) during distant hybridization. The uterus (maternal tissue) encases the reproductive structures, with the egg cell distinctly visible. Positioned centrally, the nucleus of the egg cell shows clear evidence of sperm entering, signaling the beginning of syngamy. This action triggers the formation of the zygote and is a vital step for successful fertilization and the development of hybrid seeds in interspecific wheat crosses.

Ultimately, many hybrid embryos and endosperms failed to develop due to postzygotic barriers. Cytological analysis indicates that poor chromosome pairing during meiosis in one or both parents leads to the production of aneuploid gametes, which are often inviable or produce plants with reduced fertility—an outcome frequently reported in wheat-wide hybridization studies [22,24].

3.3. Chromosome Pairing at Meiosis

The degree of homologous chromosome pairing at metaphase I in pollen mother cells (PMCs) is a critical cytogenetic parameter that influences the fertility and stability of wheat × Aegilops hybrids. In F1 plants derived from crosses between Triticum aestivum varieties (Karlygash, Bezostaya 1, Progress, and Krasnovodopadskaya 210) and Aegilops cylindrica Host, the number of bivalents per PMC ranged from 3 to 7, with corresponding univalent numbering between 7 and 15 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Degree of conjugation of chromosomes of the first generation (F1) of the hybrid plant.

Based on the bivalent distribution frequencies (Table 3), the mean number of univalents per PMC ranged from 7.7 to 10.6 across the combinations with complete datasets. No trivalents were detected in any of the hybrids examined, indicating that homoeologous pairing was extremely rare. Most bivalents were rod-shaped (open configurations), while ring bivalents occurred only occasionally, consistent with limited formation in distant hybrids.

The frequency of bivalent formation varied considerably among combinations. For instance, Bezostaya 1 × Ae. cylindrica exhibited 35.7% of cells with 3 bivalents, 55.7% with 5 bivalents, and only 8.5% with 7 bivalents. In contrast, Progress × Ae. cylindrica had a higher proportion of cells with 7 bivalents (25.1%), indicating greater chromosomal affinity between parental genomes. Similar variation was observed in Ae. triaristata crosses, where Progress × Ae. triaristata showed 15.0% of PMCs with 7 bivalents compared to 9.5% for Bezostaya 1 × Ae. triaristata.

Across all wheat × Ae. cylindrica combinations, the average frequency of 7 bivalents was 16.0%, while 5 and 6 bivalents were more frequent (45.4% and 33.6%, respectively). These patterns reflect partial homology between A-, B-, and D genomes of bread wheat and the C- and D genomes of Ae. cylindrica, which is consistent with earlier reports on the limited pairing efficiency of such combinations [5,24].

The cytogenetic profiles also revealed that most bivalents were open (2–5 per PMC), suggesting weaker chiasma formation, whereas closed bivalents (1–2 per PMC) occurred less frequently. Higher frequencies of 7 bivalents were generally correlated with an improved seed set in the same cross combinations (e.g., Bezostaya 1 × Ae. triaristata), supporting the established relationship between chromosome pairing and hybrid fertility [11,12].

Incomplete homologous pairing in many combinations likely stems from structural differences between parental chromosomes and the suppression of homoeologous recombination by the wheat Ph1 locus. Such barriers restrict introgression efficiency and necessitate strategies such as Ph1b mutants or irradiation-induced translocations to facilitate gene transfer from wild relatives [25].

3.4. Meiotic Abnormalities and Microsporogenesis Defects

A high incidence of meiotic irregularities was observed in all wheat × Aegilops hybrid combinations examined, with overall abnormality rates ranging from 82.0% to 98.3% across the three stages of analysis: first meiotic division, dyad formation, and tetrad formation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of defects in microsporogenesis of first-generation hybrid plants.

The highest abnormality rates were recorded in Krasnovodopadskaya 210 × Ae. cylindrica at the tetrad stage (98.3%), followed closely by Karlygash × Ae. cylindrica (96.3%) and Bezostaya 1 × Ae. triaristata (96.6%). Even in the lowest-scoring combination (Bezostaya 1 × Ae. cylindrica), abnormalities exceeded 82%, indicating severe reproductive barriers in all crosses studied.

The pollen cells from all analyzed combinations were nearly sterile, with percentages ranging from 82% to 98.3%. In every first-generation plant combination, the chromosomes remained unpaired during anaphase, and their movement toward the cell periphery was noted, leading to the formation of chromotype bridges. The unpaired chromosomes appeared in the dyad and tetrad stages, and in their place, micronuclei with varying degrees of distortion emerged during the pentad, hexa, and other stages (Figure 6).

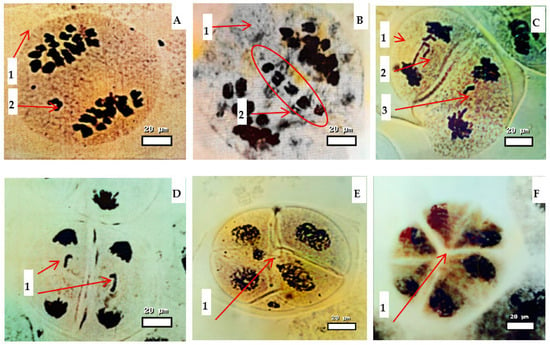

Figure 6.

Pollen cell disorders in Triticum aestivum × Aegilops hybrids observed during meiosis: (A) chromosome loss (1—anaphase; 2—chromosome aberration); (B) genome loss (1—anaphase; 2—genome omission); (C) anaphase bridge (1—telophase; 2—bridge in telophase; 3—chromosome aberration); (D) chromatin bridge (1—chromosome aberration); (E) pentad formation (1—cell division disorders (pentad)); (F) hexad formation (1—cell division disorders (in hexadecimal)). Magnification 400×. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Cytological examination revealed several recurrent abnormality types:

Chromosome loss during anaphase (Figure 6A), indicating incomplete spindle attachment and the univalent failing to segregate.

Genome loss (Figure 6B), where entire chromosome complements failed to migrate to poles, resulting in partial genome elimination and non-functional gametes.

Anaphase and chromatin bridges at telophase (Figure 6C,D), caused by an improper resolution of the recombination intermediates or structural chromosome rearrangements.

Irregular cytokinesis, pentad formation (Figure 6E), and hexads (Figure 6F), both associated with non-viable microspores.

These anomalies are consistent with poor homologous pairing at metaphase I (see Section 3.3), leading to asynchronous segregation, micronucleus formation, and the generation of genetically unbalanced gametes. Such defects directly reduce pollen viability and are a primary cause of the observed 82–98% sterility levels in the hybrids.

The cytogenetic abnormalities identified here closely align with previous studies on T. aestivum × Aegilops hybrids, where structural chromosome differences, asynapsis, and the action of the wheat Ph1 locus were shown to suppress homoeologous recombination [5,11].

The predominance of irreversible meiotic errors in these combinations suggests that even if fertilization occurs (Section 3.2), postzygotic barriers such as abnormal embryo and endosperm development will likely limit the production of viable progeny.

From a breeding perspective, identifying parental combinations with slightly lower meiotic abnormality rates may guide selection toward crosses with improved gamete viability and better prospects for stable introgression of adaptive traits from wild Aegilops species into cultivated wheat.

3.5. Somatic Chromosome Number in F1 Hybrids

To complete meiotic analysis, somatic chromosome numbers were examined in four representative F1 hybrids. The results are summarized below (Table 5).

Table 5.

Somatic chromosome numbers (2n) in F1 root tip cells of selected wheat × Aegilops hybrids (n = 25 metaphase per combination).

The results show that aneuploidy was extremely common (64–92%), which is typical of distant hybrids where univalent chromosomes fail to segregate normally in meiosis, leading to random gain or loss of chromosomes in somatic tissues. Among the four hybrids, those involving Ae. cylindrica were the most unstable. This reflects a greater genomic divergence between Ae. cylindrica (C+D genomes) and common wheat. By contrast, the Ae. triaritata crosses were relatively more stable. Their mean chromosome numbers (around 40–41) suggest less severe elimination, matching their higher hybrid seed set and better meiotic pairing. Considering that the somatic instability correlates strongly with low pollen fertility, high meiotic abnormality, and poor endosperm development, this combined evidence supports Ae. triaristata as the most genetically compatible donor species.

3.6. Pollen Fertility

Pollen viability assessments revealed consistently low fertility rates across most wheat × Aegilops combinations, with values generally below 20% and with the lowest recorded in Krasnovodopadskaya 210 × Ae. cylindrica (1.7%). The strong correlation between low chromosome pairing, abnormal meiosis, low pollen fertility, and somatic aneuploidy matches global observations in wheat × Aegilops F1 hybrids [5,11].

Among the wild relatives tested, Ae. triaristata Willd. emerged as the most compatible donor, consistently producing a higher seed set and better bivalents formation compared with Ae. cylindrica, Ae. triuncialis, and Ae. squarrosa. These results highlight Ae. triaristata as a priority species for pre-breeding programs aimed at introducing traits for stress tolerance and disease resistance into Kazakh wheat germplasm.

The strong association between complete bivalent formation and seed set suggests that cytogenetic screening can serve as a predictive tool to identify promising combinations before committing to large-scale field trials. To enhance trait introgression efficiency, integration of classical cytogenetics with molecular tools such as Genomic in Situ Hybridization (GISH) for alien chromatin detection and molecular marker analysis for locus-specific tracking is recommended. This combined approach can minimize linkage drag while facilitating the targeted transfer of desirable genes [11,26].

Due to the extremely low hybrid seed set in most combinations and the frequent abortion of embryos and endosperm, the number of harvested F1 seeds was insufficient to perform a systematic germination or seedling viability assessment. Similar limitations have been widely reported for early generation wheat × Aegilops hybrids [3,5,20,24].

Given the significant postzygotic barriers in most combinations, advanced breeding techniques such as embryo rescue, chromosome doubling, and manipulation of the Ph1 locus to promote homoeologous recombination should be explored. These methods have been shown to improve hybrid viability and allow the effective utilization of wild Aegilops germplasm in wheat improvement programs.

3.7. Comparison with Previous Studies

Aegilops-based introgressive lines and synthetic forms have been widely used in Kazakh wheat breeding. For example, several Kazakh scientists from two different organizations reported stable (2n = 42) advanced-generation hybrids of winter wheat × Ae. triaristata with improved grain quality and winter hardiness, while other authors evaluated wheat–Aegilops introgressive forms for heavy-metal tolerance [27,28,29,30]. Other studies examined the agronomic performance of introgressive lines under organic cropping conditions or assessed the grain mineral composition in advanced synthetic derivatives.

However, most existing work in Kazakhstan has focused on later-generation introgression lines (F7–F10) that have already stabilized chromosome numbers and agronomic traits. These studies do not describe the early stages of distant hybridization, including crossability, fertilization patterns, early embryo development, meiotic behavior in F1, somatic chromosome instability, and pollen fertility.

Globally, extensive research has documented Aegilops introgression, chromosome engineering, and synthetic hexaploid wheat development. Reviews by several researchers summarize the genome relationships and breeding potential of Aegilops species, but most analyses are based on international germplasm (CIMMYT, Europe, China) and rarely integrate multiple reproductive stages [3,31,32].

Thus, the novelty of the present study lies in providing the first integrated, multi-stage cytogenetic and reproductive analysis of early generation wheat × Aegilops hybrids involving Kazakh cultivars, covering hybridization success, pollen tube behavior, fertilization success, meiotic pairing, somatic chromosome number, and pollen fertility.

This integrative approach clarifies why certain combinations—particularly those involving Ae. triaristata—exhibit higher compatibility and thus provides guidance for selecting donor species for pre-breeding in Kazakhstan.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the reproductive barriers involved in distant hybridization between Kazakh wheat cultivars and four Aegilops species. Hybridization success, fertilization dynamics, meiotic behavior, somatic chromosome number, and pollen fertility all showed strong species- and genotype-specific patterns. Among the species tested, Ae. triaristata exhibited the highest genomic compatibility, producing the highest seed set, relatively faster pollen tube growth, more complete chromosomal pairing, and lower somatic instability. In contrast, Ae. cylindrica and Ae. squarrosa displayed severe postzygotic barriers and extensive genome elimination, resulting in very low fertility.

The strong correlation between meiotic stability, somatic chromosome retention, and hybrid seeds underscores the value of cytogenetic screening in predicting crossability outcomes. For breeding programs in Kazakhstan, Ae. triaristata emerges as a priority donor species for the introgression of stress tolerance and disease resistance traits. Future work integrating genomic in situ hybridization (GISH), molecular markers, embryo rescue, and manipulation of the Ph1 locus will be instrumental in overcoming hybrid sterility and enabling efficient transfer of desirable traits from wild Aegilops species into elite wheat germplasm.

Author Contributions

K.K. (Kenenbay Kozhakhmetov) and S.B.; Methodology, N.S.; Software, K.K. (Kasymkhan Koylanov) and Z.Z.; Validation, N.S. and K.K. (Kasymkhan Koylanov); Formal analysis, K.K. (Kenenbay Kozhakhmetov), S.B. and A.Z.; Investigation, N.S.; Resources, N.S., A.Z., K.K. (Kasymkhan Koylanov) and Z.Z.; Data curation, A.Z., K.K. (Kasymkhan Koylanov) and Z.Z.; Writing—original draft, K.K. (Kenenbay Kozhakhmetov) and S.B.; Writing—review & editing, A.Z.; Visualization, S.B., N.S., A.Z., K.K. (Kasymkhan Koylanov) and Z.Z.; Supervision, K.K. (Kenenbay Kozhakhmetov) and S.B.; Project administration, K.K. (Kenenbay Kozhakhmetov); Funding acquisition, S.B. and A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out within the framework of PCF BR 22885418 “Scientific support of technological development of organic production of agricultural production in the Republic of Kazakhstan,” financed by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the management of the Kazakh Research Institute of Agriculture and Plant Breeding for their support and for providing the necessary conditions for conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- FAO. GIEWS—Global Information and Early Warning System. Country Briefs. Kazakhstan. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/giews/countrybrief/country.jsp?code=KAZ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Awan, M.J.A.; Rasheed, A.; Saeed, N.A.; Mansoor, S. Aegilops Tauschii Presents a Genetic Roadmap for Hexaploid Wheat Improvement. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishii, M. An Update of Recent Use of Aegilops Species in Wheat Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Takumi, S.; Nasuda, S. Genetic Mechanisms of Allopolyploid Speciation Through Hybrid Genome Doubling. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 309, pp. 199–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár-Láng, M.; Ceoloni, C.; Doležel, J. (Eds.) Alien Introgression in Wheat: Cytogenetics, Molecular Biology, and Genomics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plekhanova, E.; Vishnyakova, M.A.; Bulyntsev, S.; Chang, P.L.; Carrasquilla-Garcia, N.; Negash, K.; Wettberg, E.V.; Noujdina, N.; Cook, D.R.; Samsonova, M.G.; et al. Genomic and phenotypic analysis of Vavilov’s historic landraces reveals the impact of environment and genomic islands of agronomic traits. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlovskaya, O.; Dubovets, N.; Solovey, L.; Leonova, I. Molecular cytological analysis of alien introgressions in common wheat lines derived from the cross of Triticum aestivum with T. kiharae. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20 (Suppl. S1), 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feulgren, R.; Rossenbeck, H. Mikroskopisch-chemischer Nachweis einer Nucleinsäure vom Typus der Thymonucleinsäure und die- darauf beruhende elektive Färbung von Zellkernen in mikroskopischen Präparaten. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1924, 135, 203–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, P. An Introduction to the Embryology of Angiosperms; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, M. Histological and Histochemical Methods—Theory and practice. Eur. J. Histochem. 2016, 60, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Friebe, B.; Zhang, P.; Gill, B.S. Homoeologous recombination, chromosome engineering and crop improvement. Chromosome Res. 2007, 15, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.-H.; Liu, W.; Friebe, B.; Gill, B.S. Homoeologous recombination in the presence of Ph1 gene in wheat. Chromosoma 2017, 126, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmage, D.H.; Dafni, A. Field tests for pollen viability: A comparative approach. Acta Hortic. 2001, 561, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochatt, S.J.; Patat-Ochatt, E.M.; Moessner, A. Ploidy level determination within the context of in vitro breeding. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2011, 104, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doležel, J.; Lucretti, S.; Molnár, I.; Cápal, P.; Giorgi, D. Chromosome analysis and sorting. Cytom. Part A 2021, 99, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiernan, J.A. Histological and Histochemical Methods: Theory and Practice, 5th ed.; Scion: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Zhang, D.; Jung, K.-H. Molecular Basis of Pollen Germination in Cereals. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggiogera, M.; Cavallo, M.; Casali, C. A brief history of the Feulgen reaction. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2024, 162, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gong, W.; Han, R.; Guo, J.; Li, G.; Li, H.; Song, J.; Liu, A.; Cao, X.; Zhai, S.; et al. Characterization, identification and evaluation of a set of wheat-Aegilops comosa chromosome lines. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyine, M.; Adhikari, E.; Clinesmith, M.; Jordan, K.W.; Fritz, A.K.; Akhunov, E. Genomic Patterns of Introgression in Interspecific Populations Created by Crossing Wheat with Its Wild Relative. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2020, 10, 3651–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goriewa-Duba, K.; Duba, A.; Wachowska, U.; Wiwart, M. An Evaluation of the Variation in the Morphometric Parameters of Grain of Six Triticum Species with the Use of Digital Image Analysis. Agronomy 2018, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugerotte, J.; Baumann, U.; Sourdille, P. Genetic control of compatibility in crosses between wheat and its wild or cultivated relatives. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 812–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, E.V.; Ulianov, A.I.; Golivanov, Y.Y.; Molchanova, T.P.; Orlova, Y.V.; Muratova, O.A. Pollen–Pistil Interaction During Distant Hybridization in Plants. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Han, R.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Guo, J.; Zi, Y.; Li, F.; et al. Characterization, Identification and Evaluation of Wheat-Aegilops sharonensis Chromosome Derivatives. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 708551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, M.-D.; Martín, A.C.; Smedley, M.; Hayta, S.; Harwood, W.; Shaw, P.; Moore, G. Magnesium Increases Homoeologous Crossover Frequency During Meiosis in ZIP4 (Ph1 Gene) Mutant Wheat-Wild Relative Hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Dundas, I.S.; Xu, S.S.; Friebe, B.; McIntosh, R.A.; Raupp, W.J. Chromosome Engineering Techniques for Targeted Introgression of Rust Resistance from Wild Wheat Relatives. In Wheat Rust Diseases; Periyannan, S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1659, pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulembayeva, K.K.; Chunetova, Z.Z.; Dauletbayeva, S.B.; Tokubayeva, A.A.; Omirbekova, N.Z.; Zhunusbayeva, Z.K.; Zhussupova, A.I. Some results of the breeding and genetic studies of common wheat in the south-east of Kazakhstan. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 7, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhahmetov, K.K.; Abugalieva, A.I.; Kazakh Research Institute of Agriculture and Plant Growing. Using gene fund of wild relatives for common wheat improvement. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 7, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhakhmetov, K.; Bastaubaeva, S.O.; Slyamova, N.D.; Zhakatayeva, A.N.; Bekbatyrov, M.B.; Zholdasbayuly, Z. Potential productivity of stable hybrid wheat varieties on organic cropping areas. Her. Sci. Seifullin Kazakh Agro Tech. Univ. 2025, 126, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazhibayeva, T. Resistance of wheat introgressive forms to heavy metals. In Proceedings of the 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM2017, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avni, R.; Lux, T.; Minz-Dub, A.; Millet, E.; Sela, H.; Distelfeld, A.; Deek, J.; Yu, G.; Steuernagel, B.; Pozniak, C.; et al. Genome sequences of three Aegilops species of the section Sitopsis reveal phylogenetic relationships and provide resources for wheat improvement. Plant J. 2022, 110, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaeva, E.D.; González Franco, M.J.; Razumova, O.; Tereshchenko, N.A.; Divashuk, M. Perspectives on the utilization of Aegilops species containing the U genome in wheat breeding: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1661257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.