Abstract

Biosynthesis of squalene in the plant chassis has broad application prospects, and identifying efficient enzymes is of great importance. Here, we analyzed the function of squalene synthase genes WsSQS and WsSQS2 from Withania somnifera for squalene biosynthesis in tobacco. WsSQS and WsSQS2 shared 93.7% amino acid (aa) similarity, with divergent residues related to catalysis, NADPH binding, and membrane anchoring. Heterologous expression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 in tobacco increased squalene content by 2.05-fold and 1.68-fold, respectively, with the OE-WsSQS lines reaching 3.19 μg/g DW and the OE-WsSQS2 lines reaching 2.58 μg/g DW, compared to the control plants. Further transcriptomic assays revealed that overexpression of WsSQS induced broader transcriptional changes in the squalene metabolic pathway than WsSQS2. Specifically, the overexpression of WsSQS up-regulated AACT, HMGS, MVD, IspE, FPPS1, FPPS2, and SQS upstream of squalene biosynthesis and down-regulated GGPPS3 downstream of FPP biosynthesis, which is the direct precursor of squalene biosynthesis, while WsSQS2 exerted a more targeted impact, primarily up-regulating HMGS and the key rate-limiting enzyme gene HMGR in the squalene biosynthesis pathway. These findings are consistent with the high efficiency of WsSQS in squalene biosynthesis in tobacco. In summary, this study provides fundamental molecular and biochemical insights into the utilization of heterologous SQSs for squalene production based on the tobacco chassis.

1. Introduction

Squalene is a triterpenoid composed of six isoprene units, which can be the precursor for the synthesis of tricyclic, tetracyclic, and pentacyclic triterpenes [1,2]. Beyond its fundamental role in metabolism, squalene has gained significant commercial and pharmaceutical interest due to its notable bioactive properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antitumor activities [3,4,5]. These attributes have positioned squalene as a high-value compound widely used in cosmetics and nutraceuticals and as an immunoadjuvant in vaccine formulations [6,7]. Traditionally, squalene has been extracted from shark liver oil, a practice that is increasingly viewed as ecologically unsustainable and economically limited in the face of growing global demand [8,9,10]. Consequently, developing sustainable and scalable biological production platforms has become a pressing research priority [11].

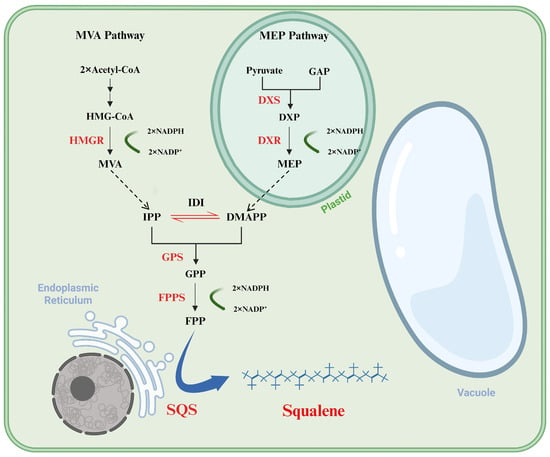

Squalene is biosynthesized through the isoprenoid pathway, with its precursors originating from both the cytoplasmic mevalonate (MVA) pathway and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway (Figure 1) [2]. In plants, the MVA pathway primarily generates isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), whereas the MEP pathway produces both IPP and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [12]. Condensation of two molecules of IPP with DMAPP, yielding farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), is catalyzed by geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPS) and farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS). Then, two molecules of FPP are condensed by squalene synthase (SQS) to form squalene [13]. Specifically, the synthesis of squalene from FPP involves two enzymatic steps. The first is the head-to-head condensation of two molecules of FPP to produce the 30-carbon intermediate presqualene diphosphate (PSPP), and the second is the NADPH-dependent reduction of PSPP to form squalene, which requires a divalent cation, Mg2+ or Mn2+, as a cofactor for catalysis [14]. Therefore, SQS can be employed as a key target in metabolic engineering aimed at enhancing squalene production.

Figure 1.

Squalene biosynthesis pathway in the cytoplasm (the MVA pathway) and plastid (the MEP pathway). HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl CoA; MVA, mevalonate; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; DXP, 1-deoxyd-xylulose 5-phosphate; MEP, 2-c-methylerythritol 4-phosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; GPP, geranyl pyrophosphate; FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate; HMGR, hydroxy methyl glutaryl CoA reductase; DXS, 1-deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase; DXR, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase; IDI, isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase; GPS, geranyl diphosphate synthase; FPPS, farnesyl diphosphate synthase; SQS, squalene synthase.

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) presents distinct advantages as a bioproduction platform, such as high biomass yield and robust secondary metabolism, which often makes it superior to other plant expression systems [15,16]. Several studies have successfully engineered tobacco for the production of carotenoids, astaxanthin, and even vaccine antigens, highlighting its versatility as a plant bioreactor [17,18,19,20]. Thus, tobacco should also be an appropriate chassis for squalene biosynthesis by expressing the highly efficient squalene synthase and manipulating metabolic pathways. However, the efficient heterologous production of squalene in tobacco remains underexplored, particularly with regard to the selection and functional characterization of high-activity SQS enzymes.

Plant SQSs have been isolated and identified from a variety of plants, including Nicotiana tabacum [21], Arabidopsis thaliana [22], Camellia oleifera [23], Panax ginseng [24], Ornithogalum caudatum [25], and Torreya grandis [26]. Most studies have demonstrated that SQS plays a crucial regulatory role in the phytosterol biosynthesis. In Withania somnifera, three squalene synthases had been identified [27,28,29]: the first was WsSQS (GenBank Acc.No.GU474427) [29], and overexpression of WsSQS demonstrated significant enhancement of squalene synthase activity and steroidal lactone phytocompound withanolide production in cell suspensions of W. somnifera [30], while silencing of W. somnifera squalene synthase negatively regulates sterol and defense-related genes, resulting in reduced withanolides and biotic stress tolerance [31]. Two distinct WsSQS cDNA clones, WsSQS and WsSQS2, were identified. Both were functionally characterized via in vitro enzyme assays, and their study provided insights into the regulation of the withanolide biosynthetic pathway [32]. However, the comparative efficiency and regulatory impact of WsSQS and WsSQS2 in a heterologous plant system remain unknown.

Although WsSQSs have been isolated and identified, their efficacy and functional mechanisms in squalene biosynthesis require further investigation. While the in vitro function and roles in withanolide biosynthesis of WsSQSs have been studied, their potential for heterologous production of squalene in a high-biomass plant chassis like tobacco and their distinct systemic effects on the host transcriptome remain unexplored. In this study, we selected and analyzed two SQS genes from W. somnifera and transformed these two genes in N. tabacum for the first time. The overexpression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 both enhanced squalene production in tobacco. Transcriptome analysis further revealed distinct molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying the two SQS genes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The plants of tobacco (N. tabacum L.) cultivar K326 were cultivated in a greenhouse at 25 °C with a photoperiod of 14 h light/10 h dark. Tobacco plants grown up to 15 cm were used for genetic transformation. The transgenic plants for further analyses were cultivated under the same condition. Tobacco seeds were surface sterilized with a disinfectant solution (containing 5% Liby® bleach and 0.05% Tween 20) for 7 min, followed by three rinses with sterile water. The sterilized seeds were then sown on MS solid medium and cultured in an indoor growth chamber.

In this experiment, three groups (WT, OE-WsSQS, and OE-WsSQS2) were established. Each group comprised three independent plants, and all subsequent experiments were performed with three biological replicates. All analyses in this study were performed using tobacco leaf samples collected at nine weeks post-germination.

2.2. Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis

Amino acid (aa) sequence alignment was conducted using BioEdit software (version 7.7.1.0). Phylogenetic analysis generated a bootstrap Neighbor-Joining (NJ) evolutionary tree using MEGA 6.0 with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.3. Vectors Construction and Transgenic Plant Development

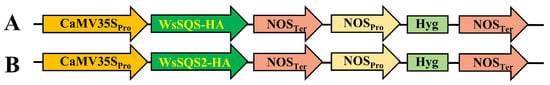

The coding sequences of WsSQS and WsSQS2 were synthesized, and the nucleotide sequences were initially cloned into the pENTR-D-TOPO® vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then integrated into the pBin19-attR-G14 (HA) vector by LR recombination with Gateway® LR Clonase™ (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) to obtain the gene overexpression vectors pBin19-WsSQS-HA and pBin19-WsSQS2-HA, which was driven by the CaMV 35S promoter (Figure 2A,B) [33]. Subsequently, the recombinant plasmid was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 using the freeze–thaw transformation method. Finally, transgenic calli and regenerated plantlets were obtained via the leaf-disk transformation method [34]. Throughout the experiment, uniform water and nutrient conditions were strictly maintained for three transgenic and wild-type (WT) plants.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of the vectors for tobacco transformation. (A) Schematic diagram of the T-DNA region of the pBin19-WsSQS-HA vector. (B) Schematic diagram of the T-DNA region of the pBin19- WsSQS2-HA vector. Hyg: hygromycin resistance gene; Pro: promoter; Ter: terminator.

2.4. Isolation and Characterization of Squalene

As for squalene isolation, fresh leaves from three transgenic lines were dried at 60 °C, ground, and sieved, respectively. Then, 0.5 g powder was saponified with 5 mL of KOH-ethanol (2 mol/L) at 75 °C and sonicated for 30 min. After cooling, 5 mL of water and 2.5 mL of n-hexane were added. The mixture was vortexed and then centrifuged at 4500 r/min for 4 min, and the supernatant was collected. This extraction was repeated four times. The combined supernatants were dried under nitrogen, redissolved in 400 µL of n-hexane, and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter.

Squalene characterization and quantification analysis was performed on an Agilent 8890 gas chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with a 5977C series mass spectrometer. Injection was performed at 280 °C with a 20:1 split ratio. The oven temperature was programmed from 80 °C (1 min hold) to 260 °C (20 min hold). Helium flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The EI ion source was set at 200 °C, and the mass range was m/z 40–610. A squalene standard stock solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared in n-hexane. Working standards (1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16.0 µg/mL) were obtained by serial dilution with n-hexane. An external standard method was used for quantification. This study employed the external standard method for quantification without the use of an internal standard. The calibration curve demonstrated good linearity (R2 > 0.999), and the sample concentrations all fell within the calibrated range.

2.5. Reference-Based Transcriptomics Analysis

Reference-based transcriptomics analysis was conducted by OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). In brief, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA purity and quantification were evaluated using a Nano Drop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Then the libraries were constructed using a VAHTS Universal V10 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Premixed Version) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2. Q value < 0.05 and fold change > 2 or fold change < 0.5 were set as the threshold for significant differential expression genes (DEGs). Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed using R (v 3.2.0) to evaluate the biological duplication of samples. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database was used for KEGG pathway analysis.

2.6. PCR and qRT-PCR Experiments

PCR experiments were performed using the Phire Plant Direct PCR Master Mix (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) rapid amplification system using transgenic leaf disks with a diameter of 0.3 mm as a template. The PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

As for qRT-PCR, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized from the RNA (500 ng) using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 5 s (denaturation) and 55 °C for 30 s (annealing). The qRT-PCR experiments were performed using the PerfectStart® Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The NtActin gene was used as the endogenous control [35]. The gene-specific primers were designed using primer premier 5.0 software (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and are listed in Table S2. The reaction mixture was 20 uL, containing 7.8 µL of ddH2O, 1 µL of cDNA templates, 0.4 µL of forward primers, 0.4 µL of reverse primers, 0.4 μL of Universal Passive Reference Dye (50×), respectively, and 10 μL of 2× PerfectStart Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen). The mixtures were added into 96-well plates with three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Amplification was performed using a Roche LightCycler 480 II System. The relative expression levels of the target genes were calculated according to the formula 2−ΔΔCT.

2.7. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses of the quantitative data were performed using Microsoft Excel (version 2511) and GraphPad Prism 9. Statistical significance was assessed using normality and log-normality tests followed by Student’s t-test. The differences between the values were assessed using the indicated test method, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant; each datum was derived from three biological replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Sequence Analysis of WsSQS Genes

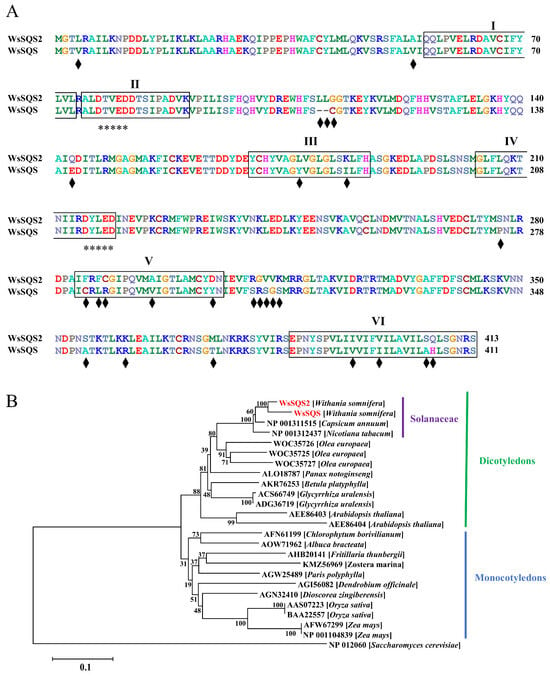

In the present study, WsSQS (GenBank Acc.No.GU474427) and WsSQS2 (GenBank Acc.No.GU732820) were selected for efficient identification of SQS. Results from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) conserved domain search revealed that both WsSQS and WsSQS2 belong to SQS (TIGR01559). The squalene synthase domains of WsSQS and WsSQS2 are from amino acids 35 to 367 and 35 to 369, respectively. Sequence alignment showed 93.7% identity similarity between WsSQS and WsSQS2, differing for only 26 residues. Both WsSQS and WsSQS2 have six highly conserved peptide domains (Figure 3A): domains I, II, and IV showed completely identical sequences, with two aspartate-rich motifs, DTVED and DYLED, while domains III, V, and VI showed less conservative sequences, with two, five, and four different amino acids, respectively, suggesting that the functional divergence might be caused by these three domains. Phylogenetic analysis of SQSs among known plant species showed that dicotyledons and monocotyledons were divided into two distinct evolutionary branches. WsSQS and WsSQS2 were clustered within the same clade with SQSs from Capsicum annuum and N. tabacum, indicating a close evolutionary relationship between SQSs in Solanaceae species (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Sequence analysis of WsSQSs. (A) Sequence alignment of the full-length aa sequences between WsSQS2 and WsSQS. The six conserved regions (I, II, III, IV, V, and VI) of squalene synthase are marked by black frames, and different residues between two sequences are marked by black diamonds. Two aspartate-rich motifs (DXXXD) associated with farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) binding were labeled with asterisks. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of WsSQSs across species. WsSQSs identified in Withania somnifera, Capsicum annuum, Nicotiana tabacum, Olea europaea, Panax notoginseng, Betula platyphylla, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Arabidopsis thaliana, Chlorophytum borivilianum, Albuca bracteate, Fritillaria thunbergii, Zostera marina, Paris polyphylla, Dendrobium officinale, Dioscorea zingiberensis, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are used in constructing the phylogenetic tree via the NJ method. The SQSs of yeast are outgroups, and the bootstrap is 1000.

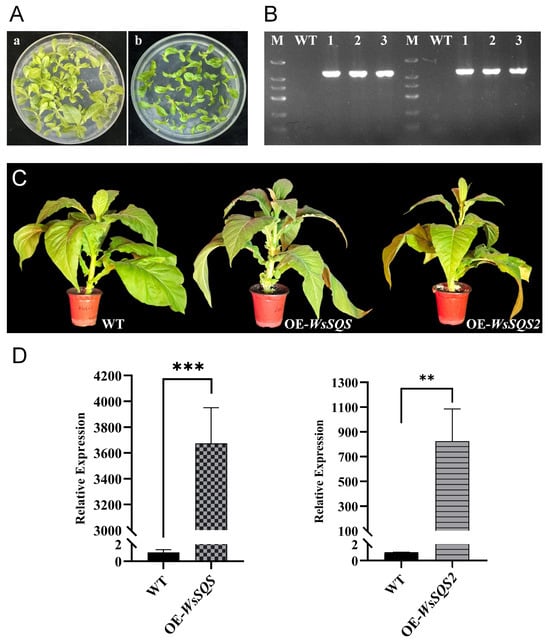

3.2. Development of WsSQS and WsSQS2 Gene-Overexpressing Plants

Overexpression vectors (35S:WsSQS and 35S:WsSQS2) were constructed and transformed into Nicotiana tabacum k326 to investigate the biological function of WsSQS and WsSQS2 in vivo. After the callus tissues and plantlets were grown on a hygromycin-resistant medium (Figure 4A), the transgenic plants were further identified through a genomic PCR experiment. PCR results showed that an expected 1.2 kb fragment could be amplified from the transgenic plants of WsSQS and WsSQS2, whereas the fragment could not be amplified from WT plants (Figure 4B). We obtained three WsSQS and WsSQS2 overexpression lines, respectively, and there was no obvious difference in appearance between the nine-week transgenic lines of two genes (Figure 4C). Moreover, qRT-PCR analysis was performed to determine the relative expression levels of the target genes in transgenic lines. Transgenic plants exhibited significantly higher expression levels of WsSQS and WsSQS2 compared to the WT (Figure 4D). These results demonstrate successfully heterologous overexpression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 in cultivated tobacco.

Figure 4.

Heterologous overexpression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 in tobacco. (A) Positive transgenic shoots in hygromycin-resistant medium. (a), WsSQS; (b), WsSQS2. (B) Detection of the target gene in the transgenic plants. M, DNA marker; WT, wild type; lanes 3–5, representative lines 1, 2, and 3 of WsSQS plants; lanes 8–10, representative lines 1, 2, and 3 of WsSQS2 plants. (C) Appearance of positive transgenic plants. The plants were photographed at nine weeks post-germination. (D) Relative expression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 between transgenic lines and WT plants. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. “**” indicates highly significant differences compared to WT plants (Student’s t-test, p < 0.01, n = 3); “***” represents extremely significant differences compared to WT plants (Student’s t-test, p < 0.001, n = 3).

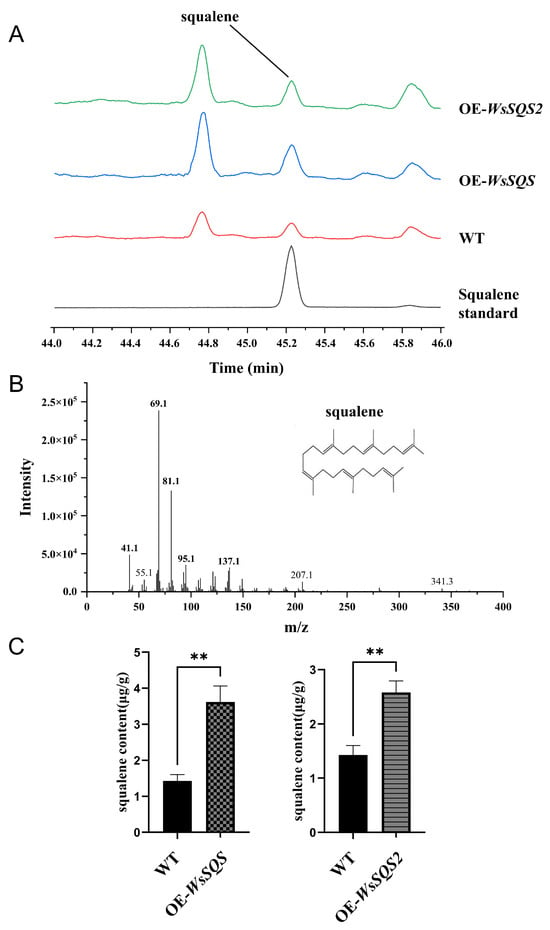

3.3. Overexpression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 Promotes Squalene Production in Tobacco

To confirm WsSQS and WsSQS2 as functional genes in vivo, the squalene in leaves was extracted among overexpression lines. The extracted samples were subjected to GC-MS analysis using a squalene standard (≥98% purity) as the reference and n-hexane as the blank control. The chromatogram showed peaks corresponding to the retention time of the squalene standard that were detected in both WT K326 and transgenic lines (Figure 5A), The mass spectrogram of the target peak showed characteristic ion fragments matching authentic squalene. These results demonstrate that all tested tobacco plants contained detectable levels of squalene. Quantitative analysis showed that OE-WsSQS lines contained 3.19 μg/g (DW, dry weight) squalene in leaves, which was significantly higher by 2.05 times than that in the WT plants, and OE-WsSQS2 lines contained 2.58 μg/g (DW) squalene in leaves, which was significantly higher by 1.68 times than that in the WT plants. These results revealed that overexpression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 promotes squalene accumulation in transgenic plants, suggesting that both WsSQS and WsSQS2 can function in tobacco.

Figure 5.

Extraction and quantification of squalene. (A) Chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) chromatograms of squalene standard, WT, OE-WsSQS, and OE-WsSQS2. The peak times of both the standard and sample are at 45.1 min. (B) GC-MS analysis of the sample. Characteristic ion fragments of squalene are 69, 81, 95, and 341 m/z. (C) Squalene contents in OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. “**” indicates highly significant differences compared to WT plants (Student’s t-test, p < 0.01, n = 3).

3.4. Transcriptome Sequencing of OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2 Plants

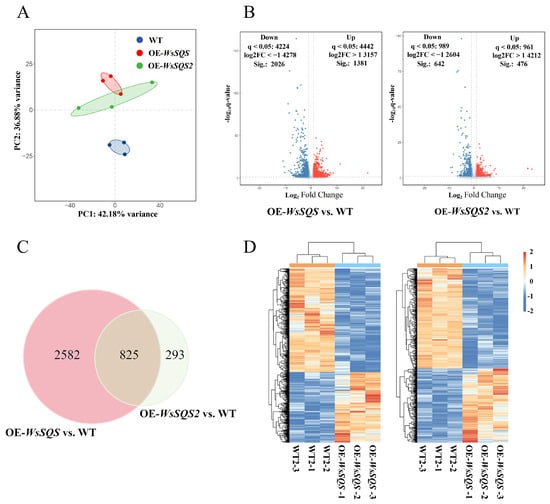

To understand the expression mechanism of squalene biosynthesis in OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2 lines, plant leaves were sampled to perform transcriptome sequencing. PCA results showed low variability among biological repeats, which indicated that there was a high correlation between repetitions (Figure 6A). The nine libraries produced an average of 6.93G clean bases per sample, with Q30 percentages (percentage of sequences with sequencing error rates < 0.1%) ranging from 96.54% to 97.14% (Table S3). On average, 97.35% of reads were mapped to the reference genome, with GC content ranging from 42.15% to 44.57%. These data showed that the RNA-seq was of high quality and could be used for further analysis.

Figure 6.

Global transcriptome analysis of transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing WsSQS and WsSQS2. (A) PCA plot of transcriptome data from WT and transgenic lines (OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2). (B) Volcano plot displaying DEGs in OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2 plants compared to WT. Significantly up-regulated genes (log2FC > 1, q-value < 0.05) are shown in red, and down-regulated genes (log2FC < −1, q-value < 0.05) are shown in blue. (C) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DEGs between the OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2 groups compared to WT. (D) Heat map DEGs, showing distinct gene expression patterns among WT, OE-WsSQS, and OE-WsSQS2 groups.

A total of 3407 DEGs were identified in OE-WsSQS compared with the WT, including 1381 up- and 2023 down-regulated genes. In the OE-WsSQS2 group, 1118 DEGs were identified, including 476 up- and 642 down-regulated genes (Figure 6B). Moreover, a total of 825 DEGs overlapped between two groups (Figure 6C), with 340 up-regulated genes and 485 down-regulated genes. Visualization of the expression levels of these genes via a heat map clearly demonstrated significant differences between the two sample groups of two genes (Figure 6D). These results indicated that there were more DEGs in the OE-WsSQS group, demonstrating that overexpression of WsSQS induced more pronounced transcriptional reprogramming compared to WsSQS2, suggesting a broader regulatory role in the plant metabolic or signaling networks.

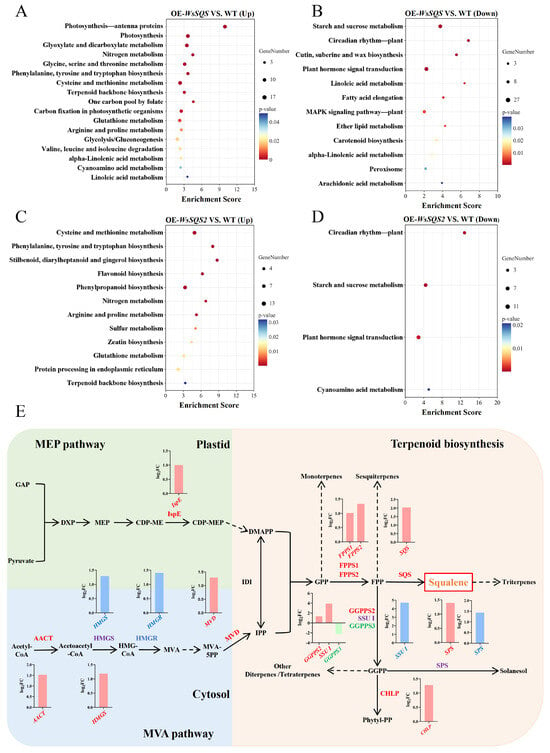

3.5. Overexpression of WsSQS and WsSQS2 Influenced Different Genes in Squalene Biosynthesis

The KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs between OE-WsSQS and WT showed that among all DEGs, 105 pathways were enriched, with 19 pathways significant enriched (Figure S1). As for up-regulated DEGs, 87 pathways were enriched, with 17 pathways significant enriched. Most pathways are involved in primary and secondary metabolism, such like cysteine and methionine metabolism (nta00270), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (nta00010), and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (nta00900) (Figure 7A). As for down-regulated DEGs, 93 pathways were enriched, with only 12 pathways significant enriched, such as starch and sucrose metabolism (nta00500), circadian rhythm—plant (nta04712), and plant hormone signal transduction (nta04075) (Figure 7B). All DEGs in OE-WsSQS2 were enriched in 81 pathways in KEGG database, with 11 pathways significant enriched (Figure S1). Among up-regulated DEGs, a total of 55 pathways were enriched, of which 8 pathways showed significant enrichment (Figure 7C). Although metabolism pathways such like cysteine and methionine metabolism (nta00270) and arginine and proline metabolism (nta00330) were also significant enriched by WsSQS2 up-regulated genes, different secondary metabolic pathways were affected, including phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (nta00940), flavonoid biosynthesis (nta00941), and zeatin biosynthesis (nta00908). Of these down-regulated DEGs, a total of 52 pathways were enriched, among which 4 pathways were significantly enriched, with 3 pathways overlapping those in OE-WsSQS, except for cyanoamino acid metabolism (nta00460) (Figure 7D). These findings indicate significant metabolic differences between the OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2 plants, suggesting that WsSQS and WsSQS2 might have distinct functional mechanisms.

Figure 7.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis and DEGs in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathway of OE-WsSQS and OE-WsSQS2 groups. Bubble plots show the significantly enriched KEGG pathways (p-value < 0.05) for DEGs identified in the comparisons of the OE-WsSQS group (A,B) and OE-WsSQS2 group (C,D). The bubble color represents the p-value, and the bubble size indicates the number of DEGs enriched in the pathway. (E) Expression profiles of DEGs in the terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathway. Genes up-regulated in the OE-WsSQS group are marked in red, those in the OE-WsSQS2 group are in blue, both up-regulated genes are in purple, and down-regulated genes are in green. In the bar chart, up-regulated genes in the OE-WsSQS group are shown in red, up-regulated genes in the OE-WsSQS2 group are in blue, and down-regulated genes in the OE-WsSQS group are represented in green. Key enzyme abbreviations: AACT, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; HMGS, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase; HMGR, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase; MVD, diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase; IspE, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase; CDP-ME, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol; CDP-MEP, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2-phosphate; FPPS, farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase; GGPPS, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase; CHLP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate reductase; SPS, solanesyl-diphosphate synthase; SQS, squalene synthase; GGPP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; SSU Ⅰ, small subunit of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase.

To further elucidate the mechanism of action and functional differentiation of WsSQS and WsSQS2, we analyzed DEGs in the entire terpenoid biosynthesis pathway, which is also related to squalene biosynthesis (Figure 7E). In the OE-WsSQS group, 11 genes were up-regulated in the terpenoid biosynthesis pathway, including IspE in the MEP pathway, AACT, HMGS, and MVD in the MVA pathway, and FPPS1/2, SQS, GGPPS2/3, SSU I, CHLP, and SPS in the terpenoid biosynthesis pathway. While only four genes were up-regulated in the OE-WsSQS2 group, including HMGS, HMGR in the MVA pathway, and SSU I and SPS in the terpenoid biosynthesis pathway, none of the MEP pathway genes were differently expressed. Notably, genes such as HMGS and SSU I were significantly up-regulated in both groups. HMGR, which encodes the rate-limiting enzyme of the MVA pathway, was more strongly up-regulated in the OE-WsSQS2 group. Interestingly, the expression of the endogenous SQS of tobacco was significantly enhanced in the OE-WsSQS group but not in the OE-WsSQS2 group. Moreover, only GGPPS3 in OE-WsSQS was down-regulated compared to the WT. The distinct transcriptional profile underscores a clear functional differentiation between WsSQS and WsSQS2, with the former exerting a broader stimulatory effect on squalene biosynthesis-related pathways.

To validate the reliability of transcriptomic data, qRT-PCR validation experiments were designed to detect the expression of five DEGs related to squalene biosynthesis. The qRT-PCR results showed that the gene expression trends of HMGS, HMGR, GGPPS3, SQS, and SPS were highly consistent with RNA-seq data (Figure S2), confirming the accuracy and reliability of transcriptomic sequencing data.

4. Discussion

Squalene, a key intermediate in triterpenoid biosynthesis, possesses significant commercial value in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries due to its diverse biological activities [2,8]. SQS catalyzes the enzymatic conversion of FPP to squalene, directing metabolic flux towards sterols and triterpenoids, which represents a critical branching point in the isoprenoid pathway [21]. In this study, we compared and analyzed two squalene synthase genes, WsSQS and WsSQS2, from W. somnifera to reveal the functional mechanisms of the two genes and to screen the efficiency of the genes in squalene biosynthesis.

Sequence analysis revealed that both WsSQS and WsSQS2 possess the characteristic features of plant SQS enzymes, including six conserved domains like other plant SQSs [26]. Despite their high sequence identity (93.7%), notable aa substitutions were observed in domains III, V, and VI. Since L177 (Leu) in WsSQS2 is highly conserved in plant SQSs, the mutation of Y175 (Tyr) in WsSQS might influence the first half-reaction of squalene formation in plants (Figure S3) [36,37]. Domain V is implicated in NADPH binding for the subsequent reduction step containing two conserved Phe residues (F285 and F287) [38], while the aa was substituted with C283 (Cys) and L285 (Leu) in WsSQS (Figure S3), which should be required for the conversion of PSPP into squalene [14]. Domain VI is involved in endoplasmic reticulum membrane anchoring and less conserved among plants [37], so the various mutants in this region of WsSQS and WsSQS2 might affect subcellular localization and access to the FPP pool. In general, the aa differences possibly affect the catalytic activity and efficiency of the two enzymes.

Although two genes (AtSQS1 and AtSQS2) with high sequence similarity have been isolated and characterized in A. thaliana, only AtSQS1 displayed the expected enzymatic activity [36]. To identifying the enzymatic activities of WsSQS and WsSQS2 in vivo, two genes were codon optimized and stably transformed into N. tabacum cv. K326 with the 35S promoter. Both WsSQS and WsSQS2 were significantly overexpressed in transgenic tobacco, and the squalene content were also significantly increased, demonstrating the successful channeling of the tobacco FPP pool towards SQS by the introduced enzymes and confirming the functional activity of both enzymes. Since the overexpression of WsSQS led to a higher accumulation of squalene (2.05-fold) than WsSQS2 (1.68-fold), functional redundancy and divergence between the two genes likely exist. The stark contrast in the number of DEGs, 3407 in OE-WsSQS versus 1118 in OE-WsSQS2, strongly implies distinct regulatory impacts of the two genes. More upstream pathways related to squalene were significantly activated by DEGs in the OE-WsSQS group, including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and cysteine and methionine metabolism, while only cysteine and methionine metabolism was significantly activated in the OE-WsSQS2 group. Moreover, DEGs in the OE-WsSQS group uniquely influenced pathways like cutin, suberine, and wax biosynthesis and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism. The down-regulation of cutin and suberin biosynthesis genes in OE-WsSQS plants suggests a possible competition for the cytosolic acetyl-CoA pool between the highly active squalene synthesis pathway and other native metabolic routes requiring similar precursors [34]. As for gene activation in terpenoid biosynthesis, the up-regulation of key genes in the MVA pathway (AACT, Nitab4.5_0006992g0070; HMGS, Nitab4.5_0009089g0020; Nitab4.5_0005622g0070, MVD) and the MEP pathway (IspE, Nitab4.5_0002300g0020) in OE-WsSQS plants suggests that WsSQS may have induced broader transcriptional reprogramming to support the increased demand for FPP. Two up-regulated FPPS genes (Nitab4.5_0003328g0080 and Nitab4.5_0005478g0020) may directly increase FPP biosynthesis. GGPP is an important precursor for diterpene biosynthesis, and the down-regulation of NtGGPPS3 (Nitab4.5_0004294g0030) might reduce the consumption of FPP, forming GGPP and other diterpenes [19]. The SSU without enzymatic activity serves to modify catalytic fidelity or to promote catalytic activity by binding LSU [39,40]. As NtGGPPS2 (Nitab4.5_0005314g0040) and NtSSU I (Nitab4.5_0003495g0010) both up-regulated in the OE-WsSQS group, NtGGPPS2 and NtSSU I might have combined into a heterodimer to increase the biosynthesis of GPP [41,42], which indirectly improved the supply of FPP precursors and increased the squalene production. Notably, a tobacco SQS gene (Nitab4.5_0001317g0110) was also significantly up-regulated in the OE-WsSQS group, potentially indicating a synergistic effect or specific regulatory cross-talk. In contrast, the OE-WsSQS2 group showed more focused up-regulation, primarily of HMGS, and a strong induction of HMGR (Nitab4.5_0000855g0140), the rate-limiting enzyme of the MVA pathway [38]. This suggests that WsSQS2 might rely more on enhancing the flux through a key regulatory node rather than broadly activating the entire pathway like WsSQS. The distinct transcriptomic profiles imply that WsSQS and WsSQS2, despite their sequence similarity, engage with the metabolic circuitry in unique ways, leading to different magnitudes of squalene yield and distinct global transcriptional outcomes. Downstream metabolites (e.g., sterols, carotenoids, and diterpenes) were not quantified, so conclusions about flux redirection are based on gene expression rather than metabolite profiles.

Squalene exhibits relatively stable chemical properties, and its extraction process is well controlled with good experimental reproducibility. More importantly, high-purity squalene standards are commercially available and easily accessible, providing a reliable basis for the preparation of an accurate calibration curve. Additionally, ideal internal standards are difficult to obtain or prohibitively expensive. For these reasons, the external standard method was selected for this study. Although the method has been validated to offer good precision and accuracy, future work could consider employing stable isotope-labeled internal standards to further improve control over variations during individual sample pretreatment and injection processes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study successfully characterized two functional SQS genes from W. somnifera and transformed them into tobacco for the first time. Their heterologous expression in tobacco effectively enhanced squalene accumulation, with WsSQS proving to be a more effective enzyme of squalene production. More importantly, our integrated approach, combining metabolic engineering with transcriptomic profiling, revealed that these highly homologous enzymes exert distinct influences on the host’s transcriptome and potentially on the regulation of the terpenoid biosynthesis network. These findings not only provide two valuable gene candidates for the metabolic engineering of squalene but also deliver critical molecular and biochemical insights. This study lays a solid foundation for the development of tobacco as an efficient bioreactor for the sustainable production of high-value squalene and underscores the importance of understanding gene-specific regulatory effects in plant synthetic biology. Looking ahead, scaling up cultivation to field conditions and employing tissue-specific or inducible expression strategies could further enhance squalene yields, advancing the industrial potential of engineered tobacco. Additionally, exploring squalene accumulation in other tissues and at different developmental stages will provide a more complete picture for application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16010012/s1. Figure S1. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of total DEGs. Figure S2. qRT-PCR validation of five DEGs related to squalene biosynthesis. Figure S3. Sequence alignment of plant and yeast squalene synthases. Table S1. Primer sequences for vector construction. Table S2. Primer sequences for qRT-PCR analysis. Table S3. Summary of transcriptome sequencing. Supplementary File. Amino acid sequences of genes relevant in squalene biosynthesis.

Author Contributions

X.L. and S.S. conceived this study, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors; Y.L., W.Z., and Z.D. performed the experiments, G.Q. and Y.Y. (Yinan Yang) analyzed the experimental data, and Y.Y. (Ying Yang) and T.T. carried out the transcriptional analyses. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Beijing Life Science Academy (BLSA), No. 2023000CC0150, the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP-TRIC-QH-2022C04), Project ZR2023QC327, supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, and the Qingdao Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology (25-1-5-xdny-19-nsh).

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptomics data are available in the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.cncb.ac.cn) under the accession number CRA033967 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. We will store the samples for three years after publication.

References

- Hillier, S.G.; Lathe, R. Terpenes, hormones and life: Isoprene rule revisited. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 242, R9–R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Ji, T.; Zhang, M.; Fang, B. Recent advances in squalene: Biological activities, sources, extraction, and delivery systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.Y.; Lin, Y.K.; Wang, P.W.; Alalaiwe, A.; Yang, Y.C.; Yang, S.C. The droplet-size effect of squalene@cetylpyridinium chloride nanoemulsions on antimicrobial potency against planktonic and biofilm MRSA. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 8133–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamani, K.; Thirugnanasambandan, S.S.; Natesan, C.; Subramaniam, S.; Thangavel, B.; Aravindan, N. Squalene deters drivers of RCC disease progression beyond VHL status. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2021, 37, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, N.; Xue, M.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, C.; Fan, Y.; Liu, W.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of squalene in copper sulfate-induced inflammation in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarkent, Ç.; Oncel, S.S. Recent Progress in Microalgal Squalene Production and Its Cosmetic Application. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2022, 27, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, D.; Singhania, R.R.; Bhatia, S.K.; Dong, C.D.; Patel, A.K. Squalene: A high-value compound for COVID-19 vaccine adjuvants and beyond pathways, production strategies, and market potential. IUBMB Life 2025, 77, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadinoto, S.; Idrus, S.; Smith, H.; Sumarsana; Radiena, M.S.Y. Characteristics Squalene of Smallfin Gulper Shark (Centrophorus moluccensis) Livers From Aru Islands, Mollucas, Indonesia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1463, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Bettiga, M.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P.; Matsakas, L. Microbial genetic engineering approach to replace shark livering for squalene. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, N.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Khambhati, K.; Braddick, D.; Singh, V. Engineering Strategies in Microorganisms for the Enhanced Production of Squalene: Advances, Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, A.; Azevedo-Silva, J.; Fernandes, J.C. From Sharks to Yeasts: Squalene in the development of vaccine adjuvants. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Concepción, M.; Boronat, A. Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. A metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Che, J.; Qi, Q.; Hou, J. Metabolic Engineering for Squalene Production: Advances and Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 27715–27725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, J.; Danley, D.E.; Schulte, G.K.; Mazzalupo, S.; Pauly, T.A.; Hayward, C.M.; Hamanaka, E.S.; Thompson, J.F.; Harwood, H.J., Jr. Crystal structure of human squalene synthase. A key enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 30610–30617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, E.; Vazquez-Vilar, M.; Orzaez, D. Engineering Conditional Transgene Expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, R.; Wang, D.; Jevnikar, A.M.; Ma, S. Tobacco, a highly efficient green bioreactor for production of therapeutic proteins. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N.; Wang, J.; Ju, F.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, T.; Zhang, H. Maximizing astaxanthin production in engineered tobacco by integrating metabolomics-directed cultivation improvement and optimized raw-material processing. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.; Tian, T.; Chai, M.; Wang, W.; Du, Y.; Zhao, S.; Timko, M.P.; Xue, Z.; et al. Engineering tobacco for efficient astaxanthin production using a linker-free monocistronic dual-protein expression system and interspecific hybridization method. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Qu, G.; Guo, J.; Wei, F.; Gao, S.; Sun, Z.; Jin, L.; Sun, X.; Rochaix, J.D.; Miao, Y.; et al. Rational design of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase enhances carotenoid production and improves photosynthetic efficiency in Nicotiana tabacum. Sci Bull. 2022, 67, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.J.; Diao, H.P.; Zhang, S.S.; Kang, S.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.; Yun, J.; Meng, H.X.; Moon, H.; Kim, W.Y.; et al. Natural peptidoglycan nanoparticles enable rapid antigen purification and potent delivery of plant-derived vaccines. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossart, N.; Berhin, A.; Sergeant, K.; Alam, I.; André, C.; Hausman, J.F.; Boutry, M.; Hachez, C. Engineering Nicotiana tabacum trichomes for triterpenic acid production. Plant Sci. 2023, 328, 111573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zheng, W.; Yu, J.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Lai, H. cDNA cloning, prokaryotic expression, and functional analysis of squalene synthase (SQS) in Camellia vietnamensis Huang. Protein Expr. Purif. 2022, 194, 106078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Du, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, R.; Ge, L.; Zhu, Z.; Li, C.; Tan, X. Light Regulated CoWRKY15 Acts on CoSQS Promoter to Promote Squalene Synthesis in Camellia oleifera Seeds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, T.; Deng, Q.; Luo, W.; Chang, R.; Zeng, D.; Tan, J.; Sun, T.; Liu, Y.G.; et al. Sustainable Production of Ginsenosides: Advances in Biosynthesis and Metabolic Engineering. Plants 2025, 14, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, L.N.; Pan, Y.T.; Kong, J.Q. cDNA isolation and functional characterization of squalene synthase gene from Ornithogalum caudatum. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 130, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Kong, C.; Ma, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Lou, H.; Wu, J. Molecular characterization and transcriptional regulation analysis of the Torreya grandis squalene synthase gene involved in sitosterol biosynthesis and drought response. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Liu, G.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Yang, Y. Isolation and functional analysis of squalene synthase gene in tea plant Camellia sinensis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 142, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, T.; Inoue, T.; Oka, A.; Nishino, T.; Osumi, T.; Hata, S. Cloning, expression, and characterization of cDNAs encoding Arabidopsis thaliana squalene synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2328–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, W.W.; Lattoo, S.K.; Razdan, S.; Dhar, N.; Rana, S.; Dhar, R.S.; Khan, S.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Molecular cloning, bacterial expression and promoter analysis of squalene synthase from Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal. Gene 2012, 499, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Samuel, G.; Bisaria, V.S.; Sundar, D. Enhanced withanolide production by overexpression of squalene synthase in Withania somnifera. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 115, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Dwivedi, V.; Rai, A.; Pal, S.; Reddy, S.G.; Rao, D.K.; Shasany, A.K.; Nagegowda, D.A. Virus-induced gene silencing of Withania somnifera squalene synthase negatively regulates sterol and defence-related genes resulting in reduced withanolides and biotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Sharma, P.; Santosh Kumar, R.J.; Vishwakarma, R.K.; Khan, B.M. Functional characterization and differential expression studies of squalene synthase from Withania somnifera. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 8803–8812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Sui, X.; Wang, J.; Tian, T.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Fang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. NtMYB305a binds to the jasmonate-responsive GAG region of NtPMT1a promoter to regulate nicotine biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsch, R.B.; Fry, J.E.; Hoffmann, N.L.; Wallroth, M.; Eichholtz, D.; Rogers, S.G.; Fraley, R.T. A Simple and General Method for Transferring Genes into Plants. Science 1985, 227, 1229–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Tian, T.; Gao, Y.; Guan, J.; Ju, F.; Bian, S.; Wang, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, B.; Liao, Z.; et al. Investigating the spatiotemporal expression of CBTS genes lead to the discovery of tobacco root as a cembranoid-producing organ. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1341324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets, A.; Keim, V.; Closa, M.; del Arco, A.; Boronat, A.; Arró, M.; Ferrer, A. Arabidopsis thaliana contains a single gene encoding squalene synthase. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.L.; Muñoz-Ocaña, C.; Posada, P.; Sicardo, M.D.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Gómez-Coca, R.B.; Belaj, A.; Moreda, W.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M. Functional Characterization of Four Olive Squalene Synthases with Respect to the Squalene Content of the Virgin Olive Oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 15701–15712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, T.; Long, R.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Z. Molecular Cloning and Functional Identification of a Squalene Synthase Encoding Gene from Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, C.Y.; Gutensohn, M.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Dudareva, N.; Lu, S. A recruiting protein of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase controls metabolic flux toward chlorophyll biosynthesis in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6866–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dixon, R.A. Heterodimeric geranyl(geranyl)diphosphate synthase from hop (Humulus lupulus) and the evolution of monoterpene biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9914–9919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, I.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Kish, C.M.; Gutensohn, M.; Maeda, H.; Varbanova, M.; Fridman, E.; Yamaguchi, S.; Hanada, A.; Kamiya, Y.; et al. The small subunit of snapdragon geranyl diphosphate synthase modifies the chain length specificity of tobacco geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase in planta. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 4002–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.L.; Wong, W.S.; Jang, I.C.; Chua, N.H. Co-expression of peppermint geranyl diphosphate synthase small subunit enhances monoterpene production in transgenic tobacco plants. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.