Transcriptome Analysis of the Response of Aphis glycines Feeding on Ambrosia artemisiifolia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aphid and Hosts

2.2. RNA Extraction and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.3. Transcriptome Assembly and Unigene Functional Annotation

2.4. Functional Annotation and Differential Expression Analysis

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.6. Bioassays

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. mRNA Sequencing, Assembly, and Functional Annotation

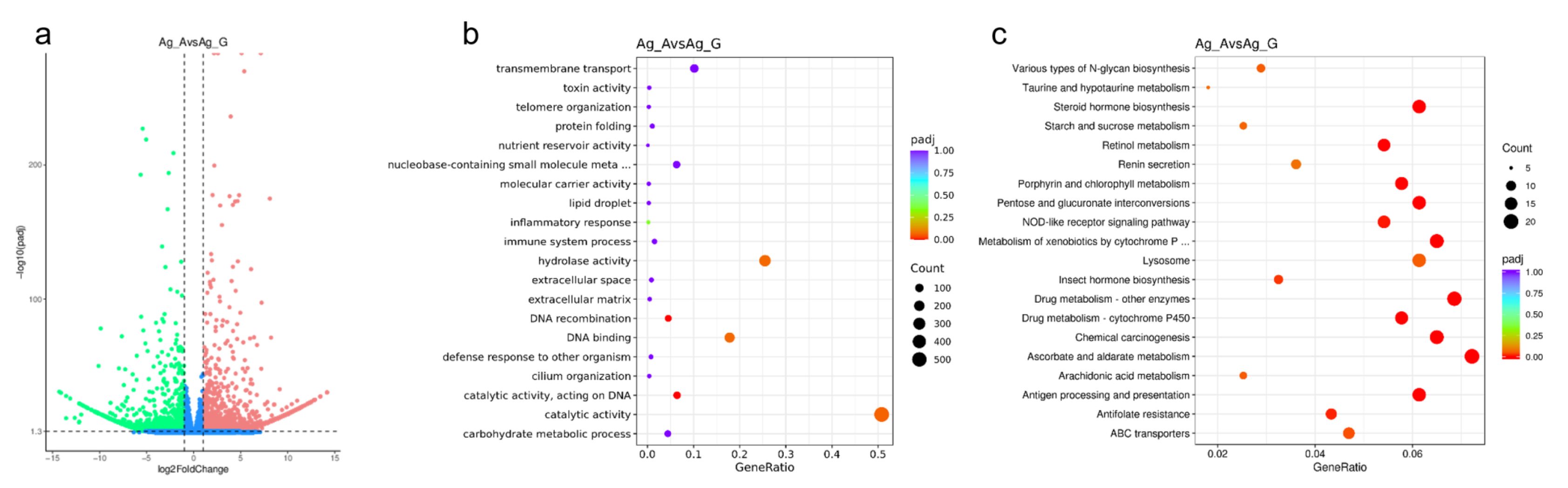

3.2. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

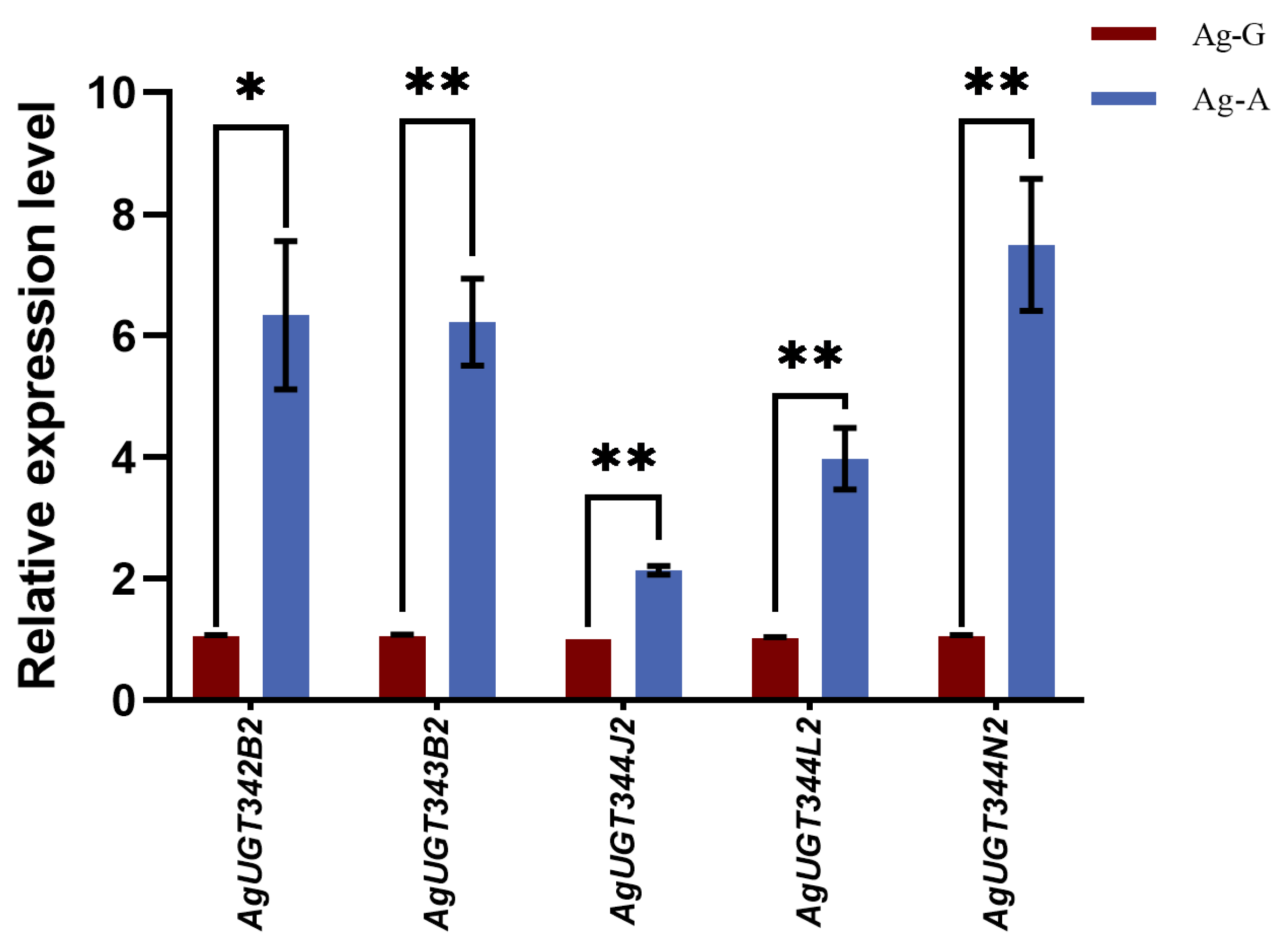

3.3. Data Validation by qRT-PCR

3.4. The Sensitivity of A. glycines to Insecticides After Feeding on A. artemisiifolia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ragsdale, D.W.; Landis, D.A.; Brodeur, J.; Heimpel, G.E.; Desneux, N. Ecology and management of the soybean aphid in North America. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Schenk-Hamlin, D.; Zhan, W.; Ragsdale, D.W.; Heimpel, G.E. The soybean aphid in China: A historical review. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2004, 97, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-Y.; Ghabrial, S.A. Effect of aphid behavior on efficiency of transmission of soybean mosaic virus by the soybean-colonizing aphid, Aphis glycines. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.H.; Alleman, R.; Hogg, D.B.; Grau, C.R. First report of transmission of soybean mosaic virus and alfalfa mosaic virus by Aphis glycines in the new world. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A.; Radcliffe, E.B.; Ragsdale, D.W. Soybean aphid, Aphis glycines Matsumura, a new vector of potato virus Y in potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essl, F.; Biró, K.; Brandes, D.; Broennimann, O.; Bullock, J.M.; Chapman, D.S.; Follak, S. Biological flora of the British Isles: Ambrosia artemisiifolia. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 1069–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.S.; Guo, J.Y.; Wan, F.H. Review on management of Ambrosia artemisiifolia using natural enemy insects. Chin. J. Biol. Control. 2015, 31, 657–665. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, F.H.; Wang, R. Occurrence, damage, and control of ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) in China. Agric. Sci. Technol. Commun. 1988, 5, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.L.; Zhu, X.Y. Research on allelopathy of Ambrosia artemisiifolia. Acta Ecol. Sin. 1996, 16, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Cecchi, L.; Skjøth, C.A.; Karrer, G.; Šikoparija, B. Common ragweed: A threat to environmental health in Europe. Environ. Int. 2013, 61, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Yang, D.M.; Liu, M.Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Control effect of 12 herbicides against ragweed. Agrochemicals 2023, 62, 933–936. [Google Scholar]

- Macel, M.; de Vos, R.C.H.; Jansen, J.J.; van der Putten, W.H.; van Dam, N.M. Novel chemistry of invasive plants: Exotic species have more unique metabolomic profiles than native congeners. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 2777–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Kurniadie, D. The invasive mechanisms of the noxious alien plant species Bidens pilosa. Plants 2024, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- War, A.R.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ahmad, T.; Buhroo, A.A.; Hussain, B.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Sharma, H.C. Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyereisen, R.; Dermauw, W.; Van Leeuwen, T. Genotype to phenotype, the molecular and physiological dimensions of resistance in arthropods. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 121, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Cui, J.; Yang, X.; Gao, X. Effects of host plants on insecticide susceptibility and carboxylesterase activity in Bemisia tabaci biotype B and greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 63, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y. Induction effects of host plants on insecticide susceptibility and detoxification enzymes of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyokhin, A.; Chen, Y.H. Adaptation to toxic hosts as a factor in the evolution of insecticide resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017, 21, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, P.I.; Bock, K.W.; Burchell, B.; Guillemette, C.; Ikushiro, S.; Iyanagi, T.; Miners, J.O.; Owens, I.S.; Nebert, D.W. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2005, 15, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Hopkins, T.L. Phenol β-glucosyltransferase and β-glucosidase activities in the tobacco hornworm larva Manduca sexta (L.): Properties and tissue localization. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1992, 21, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimunová, D.; Matoušková, P.; Podlipná, R.; Boušová, I.; Skálová, L. The role of UDP-glycosyltransferases in xenobiotic resistance. Drug Metab. Rev. 2022, 54, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krempl, C.; Sporer, T.; Reichelt, M.; Ahn, S.J.; Heidel-Fischer, H.; Vogel, H.; Heckel, D.G. Potential detoxification of gossypol by UDP-glycosyltransferases in the two Heliothine moth species Helicoverpa armigera and Heliothis virescens. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 71, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, P.J.; Zeng, X.C.; Liu, X.M.; Shang, Q.L. Characterization of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and the potential contribution to nicotine tolerance in Myzus persicae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israni, B.; Wouters, F.C.; Luck, K.; Seibel, E.; Ahn, S.J.; Paetz, C.; Reinert, M.; Vogel, H.; Erb, M.; Heckel, D.G. The fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda utilizes specific UDP-glycosyltransferases to inactivate maize defensive benzoxazinoids. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 604754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.-H.; Yin, C.; Gui, L.-Y.; Liang, J.-J.; Liu, S.-N.; Fu, B.-L.; He, C.; Yang, J.; Wei, X.-G.; Gong, P.-P.; et al. Over-expression of UDP-glycosyltransferase UGT353G2 confers resistance to neonicotinoids in whitefly (Bemisia tabaci). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 196, 105635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, P.; Lv, J.; Qiu, L. Knocking out of UDP–Glycosyltransferase gene UGT2B10 via CRISPR/Cas9 in Helicoverpa armigera reveals its function in detoxification of insecticides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 20862–20871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhaki, I. Emodin—A secondary metabolite with multiple ecological functions in higher plants. New Phytol. 2002, 155, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, M.S.J. Flavonoid–insect interactions: Recent advances in our knowledge. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Jia, Y.; Dai, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Tian, Z. Expression of Heat shock protein 90 genes induced by high temperature mediated sensitivity of Aphis glycines Matsumura (Hemiptera: Aphididae) to insecticides. Insects 2025, 16, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−∆∆CT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Malthankar, P.A.; Mathur, V. Insect-plant interactions: A multilayered relationship. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2020, 114, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, N.; Ma, K.; Li, R.; Liang, P.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Sublethal and lethal effects of the imidacloprid on the metabolic characteristics based on high-throughput non-targeted metabolomics in Aphis gossypii Glover. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 212, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, B.X.; Zhang, T.T.; Wang, W.X.; Zhang, Y.J. Effects of host plants on aphid feeding behavior, fitness, and Buchnera aphidicola titer. Insect Sci. 2024, 32, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Hou, J.; Guo, X.; Dong, D.; Li, X. Impact of maize nutrient composition on the developmental defects of Spodoptera frugiperda. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljbory, Z.; Chen, M.-S. Indirect plant defense against insect herbivores: A review. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, G.; Miao, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, B.; Guo, X. Nonanal modulates oviposition preference in female Helicoverpa assulta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) via the activation of peripheral neurons. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 3159–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J. Secondary metabolites and plant defense. In Plant Physiology, 4th ed.; Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Eds.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, UK, 2006; pp. 315–344. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.M.; Williams, R.S.; Swarthout, R.F. Distribution of the specialist aphid Uroleucon nigrotuberculatum (Homoptera: Aphididae) in response to host plant semiochemical induction by the gall fly Eurosta solidaginis (Diptera: Tephritidae). Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, S.; Croteau, R. Defensive resin biosynthesis in conifers. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 52, 689–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidel-Fischer, H.M.; Vogel, H. Molecular mechanisms of insect adaptation to plant secondary compounds. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, R.V.; Ghodke, A.B.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Edwards, O.R.; Walsh, T.K.; Oakeshott, J.G. Detoxifying enzyme complements and host use phenotypes in 160 insect species. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2019, 31, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, R.; Hussain, K.; Liu, N.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Ecotoxicity of cadmium along the soil-cotton plant-cotton bollworm system: Biotransfer, trophic accumulation, plant growth, induction of insect detoxification enzymes, and immunocompetence. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 14326–14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Schuler, M.A.; Berenbaum, M.R. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic resistance to synthetic and natural xenobiotics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenbaum, M.R.; Johnson, R.M. Xenobiotic detoxification pathways in honey bees. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 10, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, A.A.; Ranson, H.; Hemingway, J. Insect glutathione transferases and insecticide resistance. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005, 14, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, K.W. The UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) superfamily expressed in humans, insects and plants: Animal-plant arms-race and co-evolution. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 99, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, D.; Isayenkova, J.; Lim, E.K.; Poppenberger, B. Glycosyltransferases: Managers of small molecules. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005, 8, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckel, D.G. Insect detoxification and sequestration strategies. In Annual Plant Reviews; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 47, pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, P.I.; Gardner-Stephen, D.A.; Miners, J.O. The UDP-glucuronosyl-transferases. In Comprehensive Toxicology, 2nd ed.; McQueen, C.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 4, pp. 413–433. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Pan, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Peng, T.; Bi, R.; et al. Functional validation of key cytochrome P450 monooxygenase and UDP-glycosyltransferase genes conferring cyantraniliprole resistance in Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 176, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xiao, T.; Lu, K. Contribution of UDP-glycosyltransferases to chlorpyrifos resistance in Nilaparvata lugens. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 190, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wen, S.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Zeng, X.; Liu, X.; Tian, F.; Shang, Q. UDP-glycosyltransferases contribute to spirotetramat resistance in Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 166, 104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Zhao, Y.; He, L.; Ding, J.; Li, B.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Comparison of transcriptome profiles of the fungus Botrytis cinerea and insect pest Bradysia odoriphaga in response to benzothiazole. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, C.; Field, L.M. Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.J.; Vogel, H.; Heckel, D.G. Comparative analysis of the UDP-glycosyltransferase multigene family in insects. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 42, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Song, J.; Hunt, B.J.; Zuo, K.; Zhou, H.; Hayward, A.; Li, B.; Xiao, Y.; Geng, X.; Bass, C.; et al. UDP-glycosyltransferases act as key determinants of host plant range in generalist and specialist Spodoptera species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2402045121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.-B.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.-S.; Zhang, G.-Y.; Sang, Z.-Y.; Liu, J.-J.; He, C.-Y.; Zhang, J.-G. A chromosome-scale genome of Rhus chinensis Mill. provides new insights into plant–insect interaction and gallotannins biosynthesis. Plant J. 2024, 118, 766–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, X.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Shang, Z. Transcriptome profiling revealed potentially critical roles for digestion and defense-related genes in insects’ use of resistant host plants: A case study with Sitobion avenae. Insects 2020, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Giron, D.; Glevarec, G.; Mhamdi, M. Detoxification gene families in phylloxera: Endogenous functions and roles in response to the environment. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2021, 40, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermauw, W.; Wybouw, N.; Rombauts, S.; Menten, B.; Vontas, J.; Grbić, M.; Clark, R.M.; Feyereisen, R.; Van Leeuwen, T. A link between host plant adaptation and pesticide resistance in the polyphagous spider mite Tetranychus urticae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E113–E122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, R.V.; Walsh, T.K.; Pearce, S.L.; Jermiin, L.S.; Gordon, K.H.J.; Richards, S.; Oakeshott, J.G. Are feeding preferences and insecticide resistance associated with the size of detoxifying enzyme families in insect herbivores? Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2016, 13, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, M.S.; Snyder, W.E.; Hardy, N.B. Insect-plant relationships predict the speed of insecticide adaptation. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, F.C.; Reichelt, M.; Glauser, G.; Bauer, E.; Erb, M.; Gershenzon, J.; Vassão, D.G. Reglucosylation of the benzoxazinoid DIMBOA with inversion of stereochemical configuration is a detoxification strategy in lepidopteran herbivores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11320–11324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, F.; Köllner, T.G.; Gershenzon, J.; Tholl, D. Chemical convergence between plants and insects: Biosynthetic origins and functions of common secondary metabolites. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, Y.; Crowder, D.W.; Tabashnik, B.E. Evolutionary ecology of insect adaptation to Bt crops. Evol. Appl. 2010, 3, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.J.; Wright, D.J.; Dosdall, L.M. Diamondback moth ecology and management: Problems, progress, and prospects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Primer Sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| AgUGT329A3 | F: ACATTAACCGGCC TAGGCAC |

| R: ATTGCTTCGTCTCTGGTCCG | |

| AgUGT344N2 | F: TCACTGAAACAGCCTCGTCA |

| R: TTCGGCCCGTCTCCAAATAC | |

| AgUGT344L2 | F: GGTTGCCTCAACTGCACAAA |

| R: GCCATGCCTGACTCGACTAA | |

| AgUGT344M2 | F: AACGTCCGGATGATGTACCG |

| R: GATGCCGCCGATCTGTATCA | |

| AgUGT342B2 | F: AGATTTCTGGACCGTGCTCG |

| R: AGGATTTCCAAACTCGCCGT | |

| AgUGT344C5 | F: TGTCGTCGGAGTGTTCATCC |

| R: GGTGATCATCGGCGAAGGAA | |

| AgUGT344A12 | F: GTATGTCCGAGTGTGTGGCA |

| R: TCGCTCTGCAAACGTTTTGG | |

| AgUGT344J2 | F: CTTCGGATCAGTCGTAGCC |

| R: TGTGGAAACCAGTTGCCTGT | |

| AgUGT330A2 | F: AATCCGTCCCGAAAACGTCA |

| R: TTCCCATTAGACCACCGTGc | |

| AgUGT344A11 | F: CGACCCATGTCACCAACAGA |

| R: AACGAGACGACAAAGGCGAT | |

| AgUGT344D6 | F: CAGTCATTACGCCACCGAGT |

| R: CGTGGAACCGAGTGTGAAGA | |

| AgUGT341A4 | F: TATCCAAAAGGGGACGTGCC |

| R: CCGTTTTCATCATGGACCGC | |

| AgUGT345A2 | F: TGGTTACCGC AACGTGCTAT |

| R: TCCCG CGCTTACAGTTTCAT | |

| AgUGT343B2 | F: ACCTCTTGT CGAACCAGCTG |

| R: TGACAACTGGAGC GCTGAAT | |

| AgUGT343C2 | F: AATCCAGGCCTTCGCTTGAA |

| R: GGGCTCTTTGATGTGCATACC | |

| AgUGT349A2 | F: GCCCAGACAACCCTTCCTAC |

| R: TGCTGGCCATTCACTGTGAT | |

| AgUGT351A4 | F: AACGACACCCAAGGATTCCC |

| R: TTATGCCATGGATTCCCCCG |

| Sample | Raw Reads Number | Raw Bases (Gb) | Clean Reads Number | Clean Bases (Gb) | Error Rate | Q20 Ratio | Q30 Ratio | GC Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag-A1 | 21,869,722 | 6.56 G | 21,321,747 | 6.4 G | 0.01 | 99.41 | 97.14 | 38.77 |

| Ag-A2 | 23,145,145 | 6.94 G | 22,543,455 | 6.76 G | 0.01 | 99.42 | 97.31 | 39.15 |

| Ag-A3 | 22,872,388 | 6.86 G | 22,396,393 | 6.72 G | 0.01 | 98.98 | 96.96 | 38.45 |

| Ag-G1 | 20,623,371 | 6.19 G | 20,161,857 | 6.05 G | 0.01 | 99.28 | 97 | 38.57 |

| Ag-G2 | 20,122,630 | 6.04 G | 19,611,843 | 5.88 G | 0.01 | 99.4 | 97.12 | 39.12 |

| Ag-G3 | 22,025,254 | 6.61 G | 21,438,047 | 6.43 G | 0.01 | 99.39 | 97.19 | 39.15 |

| Sequencing/Annotation | Number |

|---|---|

| Total number of transcripts | 80,642 |

| Total number ofunigenes | 34,078 |

| Mean length of transcripts (bp) | 1846 |

| Mean length ofunigenes (bp) | 1272 |

| N50 length of transcripts (bp) | 2869 |

| N50 length of unigenes (bp) | 2149 |

| NR annotated | 15,418 |

| NT annotated | 33,676 |

| Pfam annotated | 10,343 |

| KOG annotated | 5799 |

| Swiss-Prot annotated | 8865 |

| KEGG annotated | 7347 |

| GO annotated | 10,343 |

| All annotated | 34,002 |

| Imidacloprid | Thiamethoxam | Lambda-Cyhalothrin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag-G | Slope (±SE) | 1.59 ± 0.33 | 2.90 ± 1.41 | 1.51 ± 0.42 |

| LC50 (mg/L) | 4.91 | 0.28 | 1.75 | |

| 95% FL | 2.60–8.54 | 0.17–0.40 | 0.55–3.18 | |

| df | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| χ2 | 1.78 | 1.11 | 0.45 | |

| R2 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Ag-A | Slope (±SE) | 0.90 ± 0.46 | 1.90 ± 0.74 | 1.62 ± 0.62 |

| LC50 (mg/L) | 28.56 | 0.70 | 6.36 | |

| 95% FL | 12.39–111.85 | 0.42–1.11 | 3.57–11.18 | |

| df | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| χ2 | 2.93 | 0.99 | 1.63 | |

| R2 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.95 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, X.; Dai, C.; Liu, J.; Tian, Z. Transcriptome Analysis of the Response of Aphis glycines Feeding on Ambrosia artemisiifolia. Agronomy 2026, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010011

Han X, Dai C, Liu J, Tian Z. Transcriptome Analysis of the Response of Aphis glycines Feeding on Ambrosia artemisiifolia. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Xue, Changchun Dai, Jian Liu, and Zhenqi Tian. 2026. "Transcriptome Analysis of the Response of Aphis glycines Feeding on Ambrosia artemisiifolia" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010011

APA StyleHan, X., Dai, C., Liu, J., & Tian, Z. (2026). Transcriptome Analysis of the Response of Aphis glycines Feeding on Ambrosia artemisiifolia. Agronomy, 16(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010011