Abstract

Cucurbita L. is a valuable gourd vegetable crop, with high nutritional and economic value. However, the lack of a molecular identification system and population genetic information has impeded the development of proper conservation strategies and marker-assisted genetic breeding for Cucurbita varieties. In this study, we developed a set of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers for distinguishing the main cultivated Cucurbita cultivars in China and providing technical support for domestic variety preservation, registration, and intellectual property protection. A total of 152 allelic variations and 308 genotypes were identified from 306 Cucurbita cultivars by using 24 SSR markers. Using 24 core markers, we successfully distinguished 300 varieties from 306 Cucurbita varieties, and the identification rate reached 98.36%. The PIC values of the 24 core markers ranged from 0.281 to 0.749, and the average value was 0.643, which was considered high genetic diversity. Based on the results of cluster analysis, principal component analysis, and population genetic structure analysis using 24 pairs of core primers for 306 Cucurbita varieties, the results were basically consistent, all categorized into three genetic clusters, corresponding to the three species: C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima. These results showed a certain correlation with phenotypic traits. DNA fingerprints were constructed for the 306 Cucurbita cultivars based on the core markers. Our research results provide a new tool for population genetic analysis, variety identification, and protection in Cucurbita cultivars with high efficiency, accuracy, and lower costs compared to conventional methods.

1. Introduction

Cucurbita belongs to the genus Cucurbita in the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae) in plant taxonomy. It has a long cultivation history and is cultivated worldwide. Currently, there are mainly three species widely cultivated in the world, namely Cucurbita maxima Duch., Cucurbita moschata Duch., and Cucurbita pepo Linn., with a chromosome number of 2n = 2x = 40 [1,2,3]. China is a major country in Cucurbita production and consumption, ranking first in the world in both the cultivation area and yield of Cucurbita. In 2022, the cultivation area of Cucurbita in China was approximately 398,700 hectares, and the yield was 7.3776 million tons, accounting for 26.2% and 32.4% of the world’s total, respectively [4]. As early as 2005, C. pepo was included in “The List of Agricultural Plant Varieties Protected in the People’s Republic of China (Sixth Batch)”; in 2016, C. moschata was included in “The List of Agricultural Plant Varieties Protected in the People’s Republic of China (Tenth Batch)” [5]; C. maxima has not yet been included in the list of new plant variety protection [6]. As of 5 August 2024, the total number of applications for C. pepo and C. moschata varieties reached 727, accounting for approximately 6.17% of the total number of vegetable applications (11,784). The total number of applications ranked 7th among the 41 vegetable genera and species, and the total number of authorized varieties reached 115, accounting for approximately 4.27% of the total number of authorized vegetable varieties (2695), with the total number of authorizations ranking ninth among the vegetable genera and species [7]. China has rich Cucurbita germplasm resources. However, for a long time, the frequent introduction of varieties and self-breeding between different regions have led to the interlacing of strains among the existing Cucurbita varieties and the complexity of their genetic relationships. Phenomena such as “the same name for different varieties” or “different names for the same variety” often occur. In addition, every year, breeders of C. pepo and C. maxima mistakenly apply for variety rights for their varieties as C. moschata. At the same time, the identification process needs to be carried out after the fruit morphology has fully developed, which will inevitably cause a huge waste of human and material resources [8]. Traditional variety identification methods mainly rely on morphological traits to distinguish varieties. Although the identification results are the most reliable, morphological traits are distributed throughout the whole growth period, and the identification cycle is long, making it difficult to meet the demand for rapid variety identification in market supervision. In addition, due to the insufficient genetic diversity of cultivated pumpkin varieties, a set of markers is more urgently needed for variety identification. Therefore, screening a set of SSR primers that meet the requirements for variety identification and are universally applicable to the Cucurbita genus and constructing a molecular identification system and SSR fingerprint database for Cucurbita varieties is of great significance. DNA molecular marker technology that directly detects the differences at the DNA level among varieties is not affected by environmental conditions, does not require field planting, and has the characteristics of being fast, efficient, and reproducible. Currently, research on constructing plant variety identification systems based on SSR markers has been widely reported in crops such as wheat, maize, rice, citrus, lettuce, non-heading Chinese cabbage, and bitter melon [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. With the rapid development of molecular biology, the completion of the whole-genome sequencing and assembly of C. maxima, C. moschata, and C. pepo has promoted the development of Cucurbita genomics and laid the foundation for the development of molecular markers [16,17]. Molecular marker technology has been widely applied in the identification of Cucurbita varieties. Yun [18] selected two primer combinations, each consisting of 4 primers, and was able to distinguish all 28 tested C. moschata varieties and constructed two ISSR-marker fingerprint maps. Sim [19] used 29 SSR markers to distinguish 160 Cucurbita varieties. Nguyen [20] used 192, 96, and 48 markers to identify 204 (discrimination rate: 91.5%), 190 (85.2%), and 141 (63.2%) out of 223 materials, respectively. Tao [21] used SRAP molecular markers to draw the DNA fingerprint maps of 88 Cucurbita materials, and 5 pairs of SRAP markers could distinguish all 88 Cucurbita materials. Liu [22] used SRAP and RSAP markers to construct the fingerprint map of Jinli Cucurbita, and the markers E1M5 and R1R7 could distinguish Hongli No. 2, Hongli, Jinli No. 2, and Jinli Cucurbita. Zhang [23] used 5 SSR markers to distinguish 48 seed-used C. pepo materials and constructed a DNA fingerprint map. SSR markers have the advantages of high polymorphism, simple operation, good repeatability, high stability, low cost, and co-dominance [24] and are one of the main recommended markers in the agricultural industry standard of China, “General Rules for DNA Molecular Marker Method for Plant Variety Identification” (NY/T 2594-2016) [25]. Establishing a molecular identification system and an SSR fingerprint database based on the fluorescence capillary electrophoresis platform has the advantages of high throughput, high resolution, and accurate data reading [26,27,28]. At present, there are few research reports on the establishment of a molecular identification system and SSR fingerprint database for Cucurbita varieties based on the fluorescence capillary electrophoresis platform. In this study, pumpkin germplasm resources were extensively collected, including cultivated varieties of the Cucurbita genus, varieties applied for variety right protection and their similar varieties, and market-sold or widely promoted varieties. Existing SSR molecular markers were gathered through a literature review, while publicly available genomes were used to develop new SSR molecular markers. A set of primers meeting the requirements for variety identification and universally applicable to the Cucurbita genus was screened using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorescent capillary electrophoresis platforms. Based on these primers, an SSR fingerprint database for Cucurbita varieties was constructed, providing technical support for rapid variety identification, genetic diversity analysis, market supervision, prompt resolution of variety disputes, protection of new varieties, and auxiliary screening of similar varieties for DUS (Distinctness, Uniformity, and Stability) testing in the Cucurbita genus.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was carried out from 2023 to 2024 at South China Agricultural University, the Science and Technology Development Center of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Yueyang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and the Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

2.1. Materials

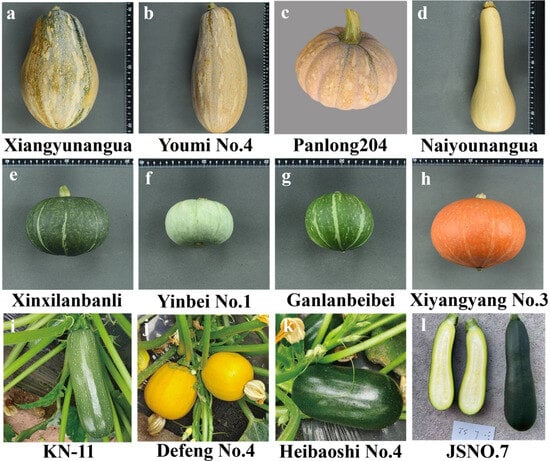

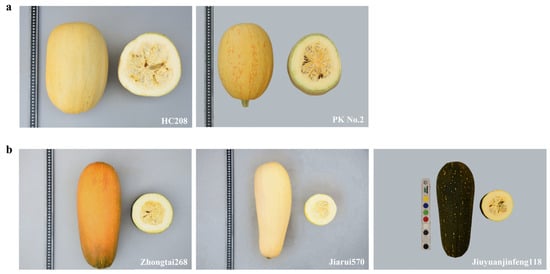

A total of 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita were included, consisting of 117 C. moschata varieties, 143 C. pepo varieties, and 46 C. maxima varieties. Among them, 252 varieties (No. 1–252) were sourced from the Plant New Variety Preservation Center of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; 32 varieties (No. 253–284) were from Guangdong Helinong Biotechnology Seed Industry Co., Ltd. (Shantou, Guangdong, China); 19 varieties (No. 285–303) were from Anhui Jianghuai Horticulture Co., Ltd. (Hefei, Anhui, China); and 3 varieties (No. 303–306) were from the Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Table A1). The collected Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita have a wide geographical origin, covering most provinces in China, and the variety types include hybrids and inbred lines. Twelve representative varieties (four in each of C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima) (Figure 1) with large phenotypic differences were selected from the collected Cucurbita species for primary screening of SSR markers.

Figure 1.

Twelve representative varieties: (a–d) C. moschata; (e–h) C. maxima; (i–l) C. pepo.

2.2. Source of SSR Primer

A total of 125 pairs of Cucurbita SSR primers were collected from the relevant literature [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Based on the publicly available whole-genome sequencing data of C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima in NCBI, the MISA v2.1 software was used to search for SSR loci. The search criteria were that the SSRs contained nucleotide repeats of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 nucleotides, with the minimum number of repeats being 6, 5, 5, 5, and 5, respectively [37]. The 200 bp sequences before and after the SSR loci were selected, and the software Primer 3.0 was used to design primers. The primer design parameters were as follows: primer length was 18–27 bp; GC content ranged from 40% to 60%; PCR product length was 100–280 bp; and the annealing temperature was 50–60 °C [38]. According to the positions of the primers on the chromosomes, 50 pairs of primers were selected from the designed primers. The above 175 pairs of SSR primers were entrusted to Shanghai Bioengineering Technology Service Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for synthesis (Table A2).

2.3. Field Planting and Traits Investigation

All the tested Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita were planted in the field at the Testing Sub-center of New Plant Varieties of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Yueyang) and the Testing Sub-center of New Plant Varieties of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Beijing). The investigation of traits referred to the “Guidelines for the Test of Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability of New Plant Varieties Cucurbita (C. moschata)” (NY/T 2762-2015) [39], the “Guidelines for the Test of Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability of New Plant Varieties Summer Squash” (NY/T 2343-2013) [40], and the “Guidelines for the Test of Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability of New Plant Varieties Summer Squash” (submitted for approval draft). The analysis was carried out by converting the traits into codes according to the trait classification range. Both Cucurbita moschata and Cucurbita maxima have 35 phenotypic traits, while Cucurbita pepo has 61 phenotypic traits. The specific trait names, types, and methods are detailed in Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5.

2.4. DNA Extraction

The collected Cucurbita seeds were soaked in water to promote germination. After germination, they were planted in seedling trays. After the true leaves emerged, in order to fully represent the genotypes of the population and eliminate the influence of individual mixed plants, 20–30 tender leaves were taken from each variety, and DNA was extracted using the improved CTAB method [41,42,43].

2.5. PCR Amplification

A 20 µL PCR reaction system was adopted, which included 2 µL of DNA template (with a concentration of 50 ng/µL), 0.5 µL of each of the upstream and downstream SSR primers (with a concentration of 0.25 µmol/L), 10 µL of 2 × Taq Plus Master Mix, and 7 µL of ultrapure water.

The PCR amplification program was as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s, for a total of 35 cycles; extension at 72 °C for 10 min’ and preservation at 4 °C for later use.

2.6. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE)

2.6.1. Gel Making

First, we washed the glass plates with a detergent and then rinsed them twice with distilled water. We wiped the glass plates clean with a cloth. After the glass plates were dry, we applied 0.8 mL of the affinity silane working solution to the inner side of the long glass plate and 0.8 mL of the stripping silane working solution to the inner side of the short glass plate. After the glass plates were completely dry, we placed 0.4 mm-thick plastic strips on both sides of the long glass plate, covered it with the short glass plate, fixed both sides with clips, and then placed it horizontally using a spirit level. In the preparation of the gel solution, we took 109.38 mL of distilled water, 46.725 mL of the PAGE solution, 12.50 mL of 10 × TBE, 687.50 µL of ammonium persulfate (APS), and 62.50 µL of tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and gently shook them to mix them evenly. We then poured the gel solution into the glass gel chamber along the glass groove at a uniform speed to avoid generating air bubbles. The shark tooth comb was gently inserted between the two glass plates, at about 4–6 mm, and left to stand at room temperature for 1–2 h. After the gel solution polymerized, we cleaned the gel solution overflowing on the surface of the glass plates, pulled out the comb, and rinsed it with clean water for later use.

2.6.2. Electrophoresis

The gel plate was installed on the electrophoresis tank and 1 × TBE buffer solution was added to both the positive and negative electrode tanks of the electrophoresis tank, ensuring that the electrode wires were submerged. Then, we performed pre-electrophoresis at a constant power of 80 W for 15 to 20 min. After that, we carried out the sample loading. We then added 2 µL of the DNA Marker and the PCR amplification products successively and used a pipette tip to load 1 to 1.5 µL of the PCR amplification product into each sample well.

2.6.3. Silver Staining

After the electrophoresis was completed, we placed the long glass plate with the attached gel into distilled water for washing. We gently shook the shaker to separate the gel plate from the glass plate. For the preparation of the staining solution and the developing solution, the staining solution consisted of 2 g of silver nitrate and 2 mL of formaldehyde, and the developing solution consisted of 12 g of sodium hydroxide and 2 mL of formaldehyde. We added them respectively to distilled water and to make up a volume of 1 L. The gel plate was placed into the staining solution and onto the shaker, where it was shaken slowly for 8 to 10 min. When the gel plate became translucent, we rinsed it with distilled water 2 to 3 times. After that, the gel plate was placed into the developing solution and gently shaken on the shaker for 8 to 10 min. When the bands on the gel plate were clear, we took out the gel plate and washed it with distilled water. After the gel plate was dried, we placed it on the gel plate observation lamp, observed and recorded the results, and took photos for preservation [44,45,46].

2.7. Fluorescent Capillary Electrophoresis

According to the lengths of the amplified fragments of each primer in the polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, one of the fluorescent dyes, including 6-FAM (blue), ROX (red), TAMRA (black), and HEX (green), is selected to label the 5′ end of the forward primer, and the fluorescent primer is synthesized. We diluted the PCR products 100 to 180 times. We used a 10 µL capillary electrophoresis system, which contains 1 µL of the PCR product, 0.1 µL of the molecular weight internal standard, and 8.9 µL of deionized formamide, which were mixed evenly, shaken, and then centrifuged. We then denatured the mixture at 94 °C for 5 min. After cooling, it was briefly centrifuged. Genotyping was performed using a genetic analyzer (ABI3730), and the results were calibrated on the SSR fingerprint analyzer according to the molecular weight internal standard, allowing us to read the data and save it [47,48,49].

2.8. Data Analysis

The SSR Analyser (V1.2.6) was used to read the data exported from the genetic analyzer [10]. For homozygous loci in the genotype data, they were represented as X/X, and for heterozygous loci, they were represented as X/Y, where X and Y were the two allelic variations at that locus, respectively, with the data of the smaller fragment in front and that of the larger fragment behind. The genotype data of the missing loci were recorded as 0/0. The software GenALEx 6.5 was used to calculate relevant genetic parameters such as the effective number of alleles (Ne), the number of alleles (Na), the expected heterozygosity (He), the observed heterozygosity (Ho), and Shannon’s diversity index (I) for each primer [50]. The software PowerMarker V3.25 was used to calculate the major allele frequency, the number of genotypes (GTs), the polymorphism information content (PIC) of each primer, and the genetic distances among the varieties [51]. The software MEGA 4.0 was used to construct an UPGMA clustering diagram based on the Nei’s genetic distances among the varieties [52,53]. The software RStudio v2024.12 was used to construct a two-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA) diagram for the 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita (the input data format is a “01 matrix” converted from genotype data, the PCA function used is dudi.pca, and the data preprocessing includes centering and scaling) [54]. The software Structure 2.3.4 was used to conduct a population genetic structure analysis of the 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita (Length of Burnin Period: 10,000; Number of MCMC Reps after Burnin: 100,000; Use Admixture Model, Initial Value of ALPHA (Dirichlet Parameter for Degree of Admixture): 1.0; Frequency Model Info: Allele Frequencies are Correlated among Pops; Set K from 1 to 10; Number of Iterations:15) [55].

3. Results

3.1. Primer Screening

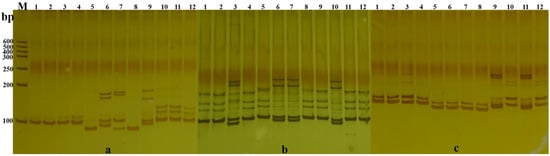

A total of 175 pairs of SSR primers were used to perform PCR amplification on 12 representative varieties. Subsequently, electrophoresis was carried out on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. As a result, 66 pairs of SSR primers with stable amplification, high polymorphism, and clear band patterns were preliminarily screened. Figure 2 shows the electrophoresis detection results of the amplified products of 3 pairs of primers in 12 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita. According to the lengths of the amplified fragments, one of the fluorescent dyes, namely 6-FAM, ROX, TAMRA, or HEX, was selected to label the 5′ end of the forward primer, and fluorescent primers were synthesized.

Figure 2.

Polymorphism of NW106, NW18, and NG2 primers in 12 representative varieties. Note: (a–c) were primers NW106, NW18, and NG2; 1–12 are Xiangyunangua, Youmi No.4, Panlong204, Naiyounnagua, Xinxilanbanlinangua, Yinbei No.1, Ganlanbeibei, Xiyangyang No.3, KN—11, Defeng No.4, Heibaoshi No.4, and JSNO.7; M: DNA Marker; bp: Size of amplified fragment.

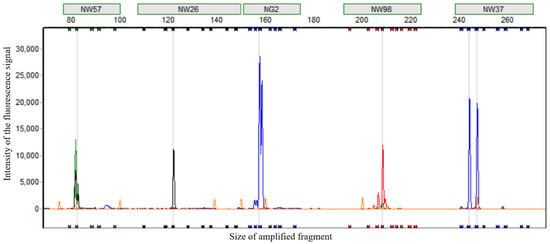

A subset of 86 varieties was selected from the 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita from different sources. Capillary electrophoresis detection was carried out using 66 pairs of fluorescent primers. Considering factors such as the ease of reading the peak patterns, high polymorphism, amplification stability, the discriminatory power of the primers, their distribution on the chromosomes, and the presence or absence of linkage effects among the primers, 24 pairs of core primers were finally determined for the identification of Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita (Table 1). To improve the detection efficiency, based on the sizes of the amplified fragments and the fluorescent colors of these 24 pairs of core primers, they were divided into 5 groups (Table 2). The primers in each group could be mixed for multiplex fluorescent capillary electrophoresis. Figure 3 shows the results of multiplex capillary electrophoresis of the five pairs of primers in Group 1 for the variety “Huangbeibei”. The interference among different primers within the group was minimal, with no abnormal peaks, and the peak patterns were easy to read.

Table 1.

Information of 24 pairs of SSR core primers.

Table 2.

Grouping of 24 pairs of core primers.

Figure 3.

Multiple capillary electrophoresis peak diagram of five pairs of primers in the first group on the variety “Huangbeibei”.

3.2. Analysis of Core Primers

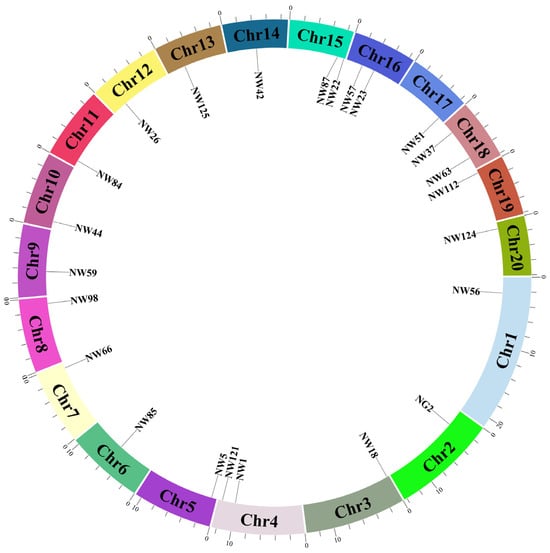

The 24 pairs of core primers were distributed across all 20 chromosomes (Figure 4), and there were no cases of equivalent identification. The primer sequences are shown in Table 2. These 24 pairs of core primers amplified a total of 152 allelic variations and 308 genotypes in 306 varieties. On average, each pair of primers produced 6.3 allelic variations and 12.8 genotypes. Among them, the primer NW56 had the largest number of allelic variations and genotypes, with 11 allelic variations and 22 genotypes, respectively, and a PIC value of 0.721 (Table 3). The PIC values of the core primers ranged from 0.281 to 0.749, with an average of 0.643. The 24 pairs of core primers exhibited rich polymorphism, which could effectively detect the genetic diversity among Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita and were suitable for variety identification.

Figure 4.

Chromosome mapping of 24 SSR core primers.

Table 3.

Genetic diversity parameters of 24 SSR core markers in 306 Cucurbita varieties.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the results based on microsatellites, this study conducted microsatellite quality control tests on 24 pairs of SSR primers. Microsatellite allele dropout and null allele detection were performed using Micro-Checker [56]. The results showed that the allele dropout rates of the 24 pairs of SSR primers ranged from 0 to 1.31%, and most primers had no dropout (Table A6). Our analysis revealed that all 24 pairs of SSR primers contained null alleles, which may be attributed to the presence of multiple alleles at SSR loci, and individual alleles might be affected by factors such as sample size, population genetic evolution, and narrow genetic background. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) tests were conducted using Genepop [57], and LD analysis was performed on all pairwise combinations (276 pairs in total) of the 24 SSR marker loci. Using r2 > 0.8 as the criterion for strong linkage, the results (Table A7) showed that only four marker pairs exhibited weak linkage (r2: 0.2–0.5), while the remaining marker pairs showed no significant linkage and had high independence. These findings indicate that the 24 SSR markers screened in this study have strong application capabilities, and the results based on SSR markers are valid and reliable.

3.3. Construction of DNA Fingerprint Database

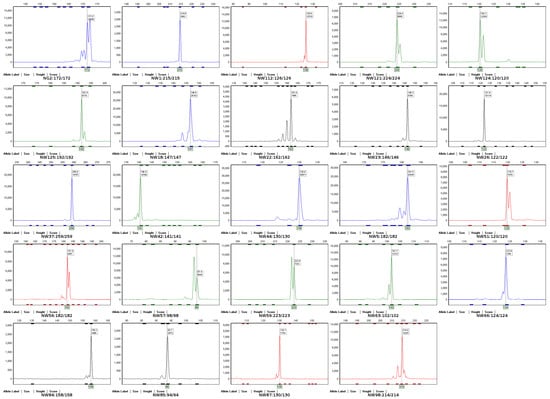

Based on the original data of capillary electrophoresis, the different amplified allelic variations were named by rounding. The fingerprint data of 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita at 24 SSR core loci were collected to construct a DNA fingerprint database for Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita. Figure 5 shows the DNA fingerprint of the variety “Nongren 91”. In addition, the fingerprint data of 306 Cucurbita varieties were converted into digital codes, and information such as their corresponding variety types and provenance was integrated. For specific information, see the website: https://kdocs.cn/l/cmkIiUYKH5Ng (accessed on 7 June 2025).

Figure 5.

DNA fingerprint database of the variety “Nongren91”.

3.4. Selection of Reference Varieties

To correct the systematic errors between different test batches or detection platforms, this study selected corresponding reference varieties for the main allelic variations detected by the core markers. Finally, 20 reference varieties were selected. Among them, 15 were from the Plant New Variety Preservation Center of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, 3 were from Anhui Jianghuai Horticulture Co., Ltd., (Hefei, Anhui, China) and 2 were from Guangdong Helinong Biotechnology Seed Industry Co., Ltd. (Shantou, Guangdong, China) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Information on 20 reference varieties.

3.5. Analysis of Genetic Diversity of Cucurbita Varieties

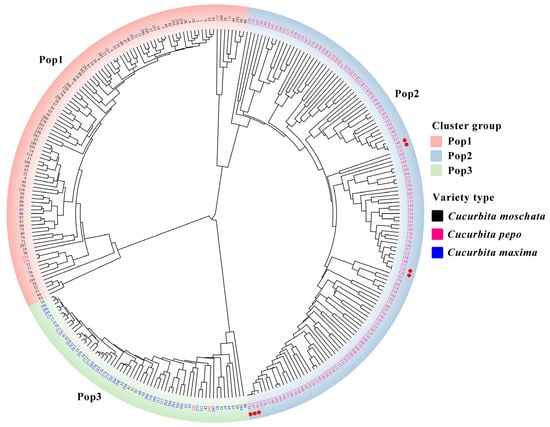

Nei’s genetic distances among 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita were calculated using PowerMarker V3.25, and a clustering diagram (Figure 6) was drawn using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means (UPGMA). The 306 varieties were divided into three main groups, namely Pop1, Pop2, and Pop3. Pop1 included 102 C. moschata varieties, 4 C. pepo varieties, and 1 C. maxima variety. Pop2 consisted entirely of C. pepo varieties. Pop3 included 45 C. maxima varieties, 15 C. moschata varieties, and 2 C. pepo varieties. This clustering could clearly distinguish most of the C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima varieties. The fact that 4 C. pepo varieties and 1 C. maxima variety were mixed in the C. moschata cluster, and 15 C. moschata varieties and 2 C. pepo varieties were mixed in the C. maxima cluster might be because these varieties were bred through hybridization between different cultivated Cucurbita species, resulting in their close genetic relationships with the cultivated species of one of their parents, thus clustering together. ‘Jinghu 36’ numbers 122 and 126 are varieties with the same name from different sources, and their genetic similarity coefficient is 1. Based on the traceability of parental relationships, it is speculated that they may be the same variety. ‘HC203’ and ‘PK No. 2’ numbers 146 and 152, as well as ‘Zhongtai 268’, ‘Jiarui 570’, and ‘Jiuyuan Jinfeng 118’ numbers 147, 154, and 170, are suspected to be the same variety or similar varieties. Further phenotypic identification is required to determine whether there are obvious differences among these varieties.

Figure 6.

Cluster analysis of 306 Cucurbita varieties by 24 SSR markers based on Nei’s distance. Note: ● Represents a variety combination with a difference point of 0 between varieties.

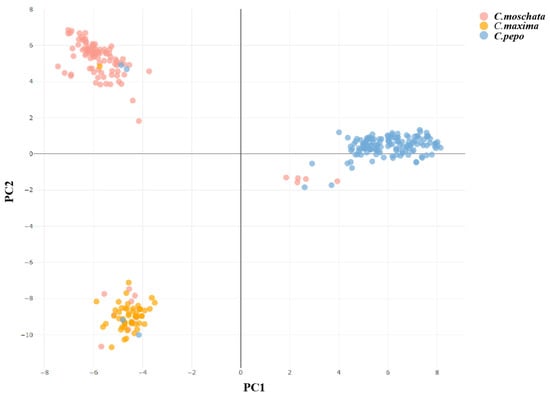

3.6. Principal Component Analysis

Dimensionality reduction analysis can intuitively reveal the genetic structure within the population. Based on the results of 24 SSR markers, the RSudio v2024.12 software was used to conduct a principal component analysis (PCA) on 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita, and a two-dimensional PCA plot for these 306 varieties was constructed (Figure 7). According to the principle that the distance between points in the two-dimensional PCA plot corresponds to the genetic relationship, it can be seen that the varieties are mainly divided into three groups, which is consistent with the clustering analysis. The upper-left part of the plot mainly consists of the C. moschata group, the lower-left part mainly consists of the C. maxima group, and the right part mainly consists of the C. pepo group. Some varieties are cross-distributed among the three major groups, indicating that these varieties have complex genetic backgrounds. They may be bred through hybridization between different cultivated Cucurbita species, resulting in their close genetic relationships with the cultivated species of one of their parents, thus clustering together. It is also possible that they contain the same gene fragments or phenotypes as other different types of Cucurbita.

Figure 7.

Two-dimensional scatter plot of principal component analysis of 306 Cucurbita varieties.

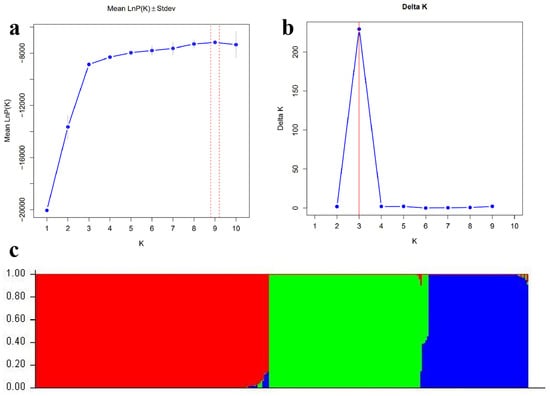

3.7. Analysis of Population Genetic Structure

In order to analyze the genetic structure present in the 306 Cucurbita materials in this study, the Structure 2.3.4 software was used to conduct a population genetic structure analysis of the 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita. When the value of K ranged from 1 to 10, the ln P(K) value continuously increased as the value of K increased (Figure 8a). Referring to the research method of Evanno [58], the optimal number of groups K was determined according to the ∆K value. As can be seen in Figure 8b, when K = 3, the likelihood value was the largest, and the 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita were genetically divided into three groups in terms of genetic structure (Figure 8c). Group I, the red part, was mainly the C. pepo group; Group II, the green part, was mainly the C. moschata group; and Group III, the blue part, was mainly the C. maxima group. The results of the population genetic structure analysis were basically consistent with those of the clustering analysis and the principal component analysis. Using the Q value analysis [59], the Q value of most varieties was greater than 0.6, indicating that the genetic relationships of most varieties in the large population were relatively simple. The genetic relationships of a very small number of varieties were complex, and there were hybridization situations among varieties from different regions.

Figure 8.

Population genetic structure analysis of 306 Cucurbita varieties based on 24 SSR markers. Note: (a) Line chart of Ln P(K) values varying with K values; (b) Line chart of ∆K values varying with K values; (c) Genetic structure of 306 Cucurbita genus varieties at K = 3; In (c), the red area represents the Cucurbita pepo group, the green area represents the Cucurbita moschata group, and the blue area represents the Cucurbita maxima group.

3.8. Analysis of Diversity of Cucurbita Varieties in Different Regions

According to the statistical analysis of the variety source regions in Appendix A, the 306 Cucurbita germplasm materials in this study are mainly distributed in regions such as East China, North China, South China, and Northwest China, while fewer varieties are found in Northeast China, Central China, Southwest China, and other regions. To better evaluate the diversity of pumpkin varieties in each region, Shannon’s Information Index and Expected Heterozygosity were calculated for varieties in each region (Table 5). The results show that pumpkin varieties in the Northwest region exhibit the highest Shannon’s Information Index and Expected Heterozygosity, indicating the richest genetic diversity and the largest intraspecific genetic variation in this region. In contrast, pumpkin varieties in the South China region have lower Shannon’s Information Index and Expected Heterozygosity values, suggesting relatively scarce genetic diversity and smaller intraspecific genetic variation in this region.

Table 5.

Diversity indices of Cucurbita varieties in different regions.

3.9. Phenotypic Identification of Molecular-Undifferentiated Varieties

Phenotypic identification is the most direct method for identifying the identity of plant varieties. When the results of molecular identification are inconsistent with those of phenotypic identification, the results of phenotypic identification shall prevail. A total of three groups, involving 7 varieties, which could not be distinguished by the 24 pairs of SSR core primers, all belonged to C. pepo varieties. Phenotypic identification was carried out for these varieties. Referring to the “Guidelines for the Test of Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability of New Plant Varieties Summer Squash” (NY/T 2343-2013), data from 61 basic traits were investigated, and the analysis was conducted by converting them into notes according to the trait classification range. The results were as follows: For the first group, the trait descriptions of the variety ‘Jinghu 36’ (122) and ‘Jinghu 36’ (126) were very similar, with no obvious differences, and they were determined to be the same variety. In the other two groups, there were some traits with significant differences among the varieties (Table 6), and comparison photos of the mature fruits were taken (Figure 9). In the second group, there were obvious differences in the secondary color (stripes) of the fruit surface and the stripe type of the mature fruits between the variety ‘HC203’ (146) and ‘PK No. 2’ (152). In the third group, there were obvious differences in the shape of the mature fruits and the secondary color (stripes) of the fruit surface between ‘Zhongtai 268’ (147) and ‘Jiarui 570’ (154). There were obvious differences in the shape of the mature fruits between ‘Zhongtai 268’ (147) and ‘Jiuyuan Jinfeng 118’ (170), and there were obvious differences in the secondary color (stripes) of the fruit surface of the mature fruits between ‘Jiarui 570’ (154) and ‘Jiuyuan Jinfeng 118’ (170). Among the three groups of varieties, the varieties within the second to third groups only had obvious differences in one to two traits, and they were very similar in phenotype, indicating that this molecular identification system can be used to assist in the screening of DUS test similar varieties.

Table 6.

The description of the distinctive traits in DUS testing among varieties with zero locus difference in the molecular markers within groups 2 to 3.

Figure 9.

The comparison photographs of ripe fruits among varieties exhibiting zero locus difference in groups 2 to 3. Note: (a) comparison between varieties ‘HC203’ and ‘PK No. 2’; (b) comparison among ‘Zhongtai268’, ‘Jiarui570’, and ‘Jiuyuanjinfeng118’.

4. Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of SSR Core Primer Polymorphism and Variety Identification Ability

The quality of molecular markers plays a decisive role, to a certain extent, in the establishment of a variety identification system. In this study, 24 pairs of core primers were screened out from 175 pairs of SSR primers. The PIC values of these core primers ranged from 0.281 to 0.749, with an average PIC value of 0.643, showing moderately high polymorphism. This value is higher than Zhang et al.’s 0.63 [23] and slightly lower than Sim et al.’s 0.674 [19]. Using these 24 pairs of core primers in this study, a total of 152 allelic variation sites were amplified from 306 collected varieties, which included C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima. On average, each pair of primers produced 6.3 allelic variation sites, which is higher than Zhang et al.’s 5.65 [23], Wang et al.’s 4.12 [60], and Liu et al.’s 2.09 [61] and slightly lower than Sim et al.’s 0.674 [19]. The test materials in Sim et al.’s study [19] included varieties of Cucurbita ficifolia type and some varieties bred through interspecific hybridization, while the test materials in this study were mainly the major cultivated C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima varieties in China. The genetic diversity of the materials in this study is relatively narrow, which may be the reason why the average number of allelic variations and the average PIC value of the core primers in this study are slightly lower.

The establishment of a variety identification system should use the optimal primer combination to distinguish the largest number of varieties, so as to achieve the best identification results. Su et al. [15] used 20 pairs of SSR core primers to distinguish 202 out of 208 bitter gourd varieties, with a distinguishing rate of 97.11%. Yin et al. [14] used 23 pairs of SSR core primers to distinguish 418 out of 423 non-heading Chinese cabbage varieties, with a distinguishing rate of 99.99%. Ling et al. [13] used 22 pairs of core primers to distinguish 221 out of 233 lettuce varieties, with a distinguishing rate of 96.09%. Among the 306 Cucurbita varieties of the genus Cucurbita in this study, there was a group of varieties with no obvious differences in field phenotypic identification, which were determined to be the same variety. Therefore, the actual number of varieties was 305. The 24 pairs of core primers can distinguish 300 out of 305 Cucurbita varieties. The actual discrimination rate reaches 98.36%, which is higher than the 97.11% reported by Su et al. [15] and 96.09% reported by Ling et al. [13]. It meets the requirement of a 95% variety discrimination rate stipulated in the “General Principles for DNA Molecular Marker Methods in Plant Variety Identification” [25]. These primers have a strong ability to distinguish varieties and can be effectively used for the rapid identification of Cucurbita varieties, authenticity testing, and the protection of variety rights.

4.2. Identification of Germplasm Resources and Varieties Combined with Molecular Markers and Phenotypes

In this study, 24 pairs of SSR core primers were used to cluster the potential varieties with the same name from different sources together and distinguish two groups of “varieties with the same name but different identities” within the genus Cucurbita. Applying this set of core primers to the collection and identification of Cucurbita germplasm resources can, on the one hand, avoid the repeated collection of Cucurbita germplasm resources, and on the other hand, prevent the omission of some excellent germplasm resources, especially the local varieties with the same name, so as to improve the efficiency of the collection, preservation, and identification of germplasm resources. In this study, 24 pairs of SSR core primers were screened based on the fluorescent capillary electrophoresis platform. According to the fragment sizes of the amplified products of each core primer and the colors of the fluorescent markers, these 24 pairs of core primers were divided into 5 groups for electrophoresis, which greatly improved the detection efficiency and reduced the detection cost. It is suitable for the large-scale identification of Cucurbita germplasm resources and varieties.

SSR markers are considered “neutral” markers, which do not have obvious biological functions and are usually located in the non-transcribed regions of the genome [62]. Therefore, SSR markers are very suitable for variety identification. However, not all varieties can be identified by molecular markers. Especially for some varieties with a very narrow genetic background, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them by molecular markers. Among the 306 varieties in this study, 7 varieties could not be distinguished by molecular markers, among which 2 belonged to the same variety, and the remaining 5 varieties could be distinguished by field phenotypic identification. This indicates that in variety identification, molecular markers still cannot completely replace morphological markers. Combining the two methods can effectively improve the accuracy of identification. The preliminarily screened varieties in this study are highly representative, and the screened molecular markers can better reflect the genetic diversity of the population. In general, varieties with a close molecular genetic distance also have very similar descriptions of their phenotypic traits. Among the three groups of seven varieties with a molecular genetic distance of zero in this study, there is one group of two varieties whose phenotypic traits are very similar and are judged to be the same variety. For varieties with obvious phenotypic differences, the number of different traits is small and the degree of difference in trait expression is generally small. This shows that the set of molecular markers in this study can be used as a technical means to assist the screening of DUS to test similar varieties.

5. Conclusions

In this study, 24 pairs of core primers screened using the polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorescent capillary electrophoresis platforms were employed to construct a fingerprint database for 306 varieties of the genus Cucurbita. A technical system for variety identification that is applicable to C. moschata, C. pepo, and C. maxima was established. The 24 pairs of core primers can distinguish 300 out of 305 varieties of the genus Cucurbita, with a discrimination rate of 98.36%, which meets the requirements for variety identification specified in the “General Principles for DNA Molecular Marker Methods in Plant Variety Identification”. This system can be used for the rapid identification of Cucurbita varieties, analysis of genetic diversity, market supervision, rapid identification in variety disputes arbitration, protection of new varieties, and auxiliary screening of similar varieties for DUS testing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and X.W.; methodology, Y.M.; software, S.L., W.X., H.H., and L.L.; validation, J.Z., X.L., and Y.M.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z., C.P., L.L., and B.T.; resources, J.Z. and Z.X.; data curation, J.Z., X.L., S.L., W.X., and H.H.; writing—original draft, J.Z., X.W., X.L., B.T., R.J., and Z.X.; writing—review and editing, J.Z., X.W., C.P., X.Z., X.Y., B.T., and Z.X.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, R.J.; project administration, X.W., X.L., X.Z., and X.Y.; funding acquisition, R.J. and Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Project for the Conservation of Species and Varietal Resources (h20230603); National Science and Technology Major Project for Agricultural Biological Breeding (2022ZD04019, 2022ZD040190203).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Information on 306 Cucurbita varieties.

Table A1.

Information on 306 Cucurbita varieties.

| NO. | Variety Name | Variety Type | Region | NO. | Variety Name | Variety Type | Region | NO. | Variety Name | Variety Type | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panlong204 A | C. moschata | Anhui | 103 | Xuelong A | C. maxima | Xinjiang | 205 | ZT17429 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 2 | Xinjiangmi2hao A | C. moschata | Anhui | 104 | Meiyaqiantu A | C. maxima | Anhui | 206 | ZT5816 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 3 | Jiangyimopan16005 A | C. moschata | Anhui | 105 | RCH2521 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 207 | ZT5818 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 4 | RWP93102 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 106 | RTCU9267 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 208 | ZT5886 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 5 | Jinyoumi1hao A | C. moschata | Hunan | 107 | Weiermixiaobei A | C. maxima | Shandong | 209 | Dingyan2202 A | C. pepo | Henan |

| 6 | Heliqihao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 108 | RCA2203 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 210 | Xinlü4306 A | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 7 | Youmi1hao A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 109 | Weiermihuangfei A | C. moschata | Shandong | 211 | Zhongtai16 A | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 8 | Tianmi A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 110 | Weiermijinling A | C. maxima | Shandong | 212 | Xiuyu916 A | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 9 | C128 B | C. moschata | Guangdong | 111 | Weiermiyihao A | C. maxima | Shandong | 213 | TBB9083 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 10 | Wawamiyihao A | C. moschata | Hunan | 112 | Jinpingguo33 A | C. maxima | Gansu | 214 | Dingyan2201 A | C. pepo | Henan |

| 11 | Xiaohei A | C. moschata | Beijing | 113 | Jinpingguo77 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 215 | Yuhu816 A | C. pepo | Hainan |

| 12 | Xingshudaguomiben A | C. moschata | Hunan | 114 | RCP21423 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 216 | Luhu3hao A | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 13 | Heliyihao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 115 | RCP21442 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 217 | Zifeng119 A | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 14 | Helisanhao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 116 | RCP1767 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 218 | ZT9092 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 15 | Tianli A | C. moschata | Sichuan | 117 | PK1582 B | C. maxima | Jiangsu | 219 | Zifeng49 A | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 16 | Jinbaoliyihao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 118 | Chunyu60 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 220 | Yuyan16 A | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 17 | Fulu333 A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 119 | Boshou410 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 221 | JH15835 B | C. pepo | Beijing |

| 18 | Xingshudaguo A | C. moschata | Hunan | 120 | Boshou607 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 222 | JH865 B | C. pepo | Beijing |

| 19 | Yunnan2hao-1-1 A | C. moschata | yunnan | 121 | Weikeduo A | C. pepo | Beijing | 223 | Bofeng A | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 20 | Panlong203 A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 122 | Jinghu36 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 224 | Baijiale A | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 21 | Youmi1hao A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 123 | Jinlierhao | C. pepo | Shanxi | 225 | Haojie9hao A | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 22 | RCP1730 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 124 | Kuaihulu A | C. pepo | Beijing | 226 | Suchengyihao A | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 23 | Guangzhoujinling A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 125 | 9794Xihulu A | C. pepo | Beijing | 227 | HS513 B | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 24 | Mitianxing A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 126 | Jinghu36 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 228 | Kairuite A | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 25 | Jinchuanmixiang A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 127 | Jiuyuanjinfeng68 A | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 229 | HS524 B | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 26 | Jinchuangaoming A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 128 | Jinfengerhao A | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 230 | HS512 B | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 27 | Jinchuanjinxiang A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 129 | Zhongzhongrekang5hao A | C. pepo | Beijing | 231 | Yuyan17 A | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 28 | Panlong211 A | C. moschata | Shandong | 130 | Zhongzhongrekang1hao A | C. pepo | Beijing | 232 | Yuyan112 A | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 29 | Nanmiyihao A | C. moschata | Tianjin | 131 | Zhongzhongzi2hao A | C. pepo | Beijing | 233 | HCA2 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 30 | Jibei A | C. moschata | Tianjin | 132 | Zhongzhongzi1hao A | C. pepo | Beijing | 234 | Farui A | C. pepo | Xinjiang |

| 31 | Runbei A | C. moschata | Tianjin | 133 | Cuiying108 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 235 | JP2102 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 32 | Fubei A | C. moschata | Tianjin | 134 | Zhongzhongz10 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 236 | JP2203 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 33 | Yinjueerhao A | C. moschata | Tianjin | 135 | P7 A | C. pepo | Beijing | 237 | TEQ3 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 34 | Yinzhu A | C. moschata | Tianjin | 136 | Lüfu95 A | C. pepo | Jiangsu | 238 | X066 B | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 35 | Guifeimi A | C. moschata | Hunan | 137 | Jinhui5hao A | C. pepo | Heilongjiang | 239 | Zhangfengerhao A | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 36 | Jinyuan A | C. moschata | Hunan | 138 | Younite928 A | C. pepo | Henan | 240 | HC0024 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 37 | Jiuyuanjinfeng108 A | C. moschata | Neimenggu | 139 | 8M03 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 241 | HCE674 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 38 | Panlong212 A | C. moschata | Anhui | 140 | Yuncui A | C. pepo | Shandong | 242 | Nongren22 | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 39 | PJB0012 B | C. moschata | Fujian | 141 | S736 B | C. pepo | Henan | 243 | Yuyan109 A | C. pepo | Gansu |

| 40 | Sizhuang17 A | C. moschata | Zhejiang | 142 | Shengrun817 A | C. pepo | Henan | 244 | HCA5 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 41 | Beiluli2hao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 143 | HC208 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 245 | Hongchangzhangfeng A | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 42 | Beiluli1hao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 144 | Hongchang212 A | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 246 | HCE671 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 43 | Madun2hao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 145 | Chuanqihongchang211 A | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 247 | HCE682 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 44 | Xiaojinbei A | C. moschata | Xinjiang | 146 | HC203 B | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 248 | Hongchangyihao A | C. pepo | Neimenggu |

| 45 | Zhengyuan3hao A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 147 | Zhongtai268 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 249 | Nongren91 B | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 46 | Sizhuang21 A | C. moschata | Zhejiang | 148 | Nongren518 A | C. pepo | Hebei | 250 | Nongren2230 B | C. pepo | Shandong |

| 47 | Zhengyuan1hao A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 149 | H020 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 251 | Donghu19hao A | C. pepo | Shanxi |

| 48 | PJB0092 B | C. moschata | Fujian | 150 | Donghu32hao A | C. pepo | Shanxi | 252 | Dingyan2205 A | C. pepo | Henan |

| 49 | Zhengyuan2hao A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 151 | Donghu No.16 A | C. pepo | Shanxi | 253 | Linong1haoxiangyunangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 50 | Sizhuang19 A | C. moschata | Zhejiang | 152 | PK No.2 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 254 | Zhengyuan1haomibennangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 51 | Deli327 A | C. moschata | Shandong | 153 | Jiarui600 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 255 | Chengxingmibennangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 52 | Dinglibahao A | C. moschata | Shandong | 154 | Jiarui570 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 256 | Shanhaimibennangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 53 | Deli902 A | C. moschata | Shandong | 155 | Huangbeibei A | C. pepo | Shanghai | 257 | Xiangxiangnangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 54 | Lüxiuer A | C. moschata | Xinjiang | 156 | Baibeibei A | C. pepo | Shanghai | 258 | Linonghuashengnangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 55 | Xinhuali A | C. moschata | Zhejiang | 157 | Nongren968 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 259 | Zajiaofaxinangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 56 | Fangfang A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 158 | Meihuicheng216 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 260 | V201 B | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 57 | Meimei A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 159 | Bulanding A | C. pepo | Shandong | 261 | Linongmopannangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 58 | Shilengmi1hao A | C. moschata | Anhui | 160 | Meixiu A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 262 | Xinxilanbanli A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 59 | Jinpingguo203 A | C. maxima | Gansu | 161 | Yuanbaosanhao A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 263 | Linongnennangua A | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 60 | Shengshengmi2hao A | C. moschata | Anhui | 162 | Qiusheng A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 264 | Linonglüguizunangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 61 | Jifeng77 A | C. moschata | Guangxi | 163 | Jialing A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 265 | Ganlanguizunangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 62 | Hongjianguizu A | C. maxima | Guangdong | 164 | Badao A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 266 | Linonghuipiduancuguizu2haonangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 63 | Lüyuan28hao A | C. maxima | Zhejiang | 165 | JR003CM B | C. pepo | Gansu | 267 | Linong3haobanlinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 64 | Chengzhang42hao A | C. maxima | Zhejiang | 166 | JR19D B | C. pepo | Gansu | 268 | Linong9haobanlinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 65 | Jifei A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 167 | ZTPK04 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 269 | Aibisibanlinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 66 | Jixianfeng A | C. moschata | Hebei | 168 | ZT2H B | C. pepo | Gansu | 270 | Yinlinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 67 | Fuwaxianfeng A | C. pepo | Gansu | 169 | Xiuyu160 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 271 | Beilishihaonangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 68 | Hongfenjiaren A | C. maxima | Guangdong | 170 | Jiuyuanjinfeng118 A | C. pepo | Neimenggu | 272 | Dabeinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 69 | RCP1257 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 171 | Zhenhu9hao A | C. pepo | Shandong | 273 | Huiyou1haobeibeinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 70 | RWP9402 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 172 | Shenghu11 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 274 | Huiyou2haobeibeinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 71 | RCP6321 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 173 | Luhu2hao A | C. pepo | Shandong | 275 | Huiyou3haobeibeinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 72 | RWP281 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 174 | Gangqinuo A | C. pepo | Shandong | 276 | Linong3haobeibeinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 73 | RWP297 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 175 | Dongdiou A | C. pepo | Shandong | 277 | Linong23haobeibeinangua A | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 74 | RCB2263 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 176 | Donghu688 A | C. pepo | Henan | 278 | G163 B | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 75 | RCB8N25 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 177 | Xiaboke A | C. pepo | Shandong | 279 | Q1174 B | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 76 | RWP286 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 178 | Maodun A | C. pepo | Shandong | 280 | Q1177 B | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 77 | Sizhuang11 A | C. moschata | Zhejiang | 179 | Jinyu1hao A | C. pepo | Gansu | 281 | V222 B | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 78 | Weiermiheizhenzhu A | C. maxima | Shandong | 180 | 9M13 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 282 | V224 B | C. moschata | Guangdong |

| 79 | Linongjinxiang A | C. moschata | Guangdong | 181 | Zhangfengyihao A | C. pepo | Gansu | 283 | V264 B | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 80 | RTSY671 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 182 | Ziguan12hao A | C. pepo | Shanxi | 284 | V379 B | C. maxima | Guangdong |

| 81 | Beili4Hao A | C. maxima | Anhui | 183 | Ziguan No.8 A | C. pepo | Shanxi | 285 | Xiangyunangua A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 82 | Fuwa808 A | C. maxima | Gansu | 184 | Sanruishuoguo A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 286 | Youmi No.4 A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 83 | RCP1734 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 185 | Haojie5hao A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 287 | Naiyounangua A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 84 | RTCU2534 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 186 | Sanruiyuguo A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 288 | Shengsheng1hao A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 85 | RTCU2530 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 187 | Gongxi518 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 289 | Shengsheng4hao A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 86 | RTDL6802 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 188 | Gongxi568 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 290 | Shilengmi3hao A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 87 | PK201 B | C. maxima | Neimenggu | 189 | SF2080D2 B | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 291 | Youmi18hao A | C. moschata | Anhui |

| 88 | PK529 B | C. moschata | Neimenggu | 190 | Haojie4hao A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 292 | Yinbei No.1 A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 89 | Sizhuang33 A | C. maxima | Zhejiang | 191 | Haojie1hao A | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 293 | Ganlanbeibei A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 90 | Sizhuang31 A | C. moschata | Zhejiang | 192 | SF2021XT B | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 294 | Xiyangyang No.3 A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 91 | Tianmi1hao A | C. moschata | Beijing | 193 | SF2025dapian B | C. pepo | Xinjiang | 295 | Beili4hao A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 92 | Jinpinyinbei2hao A | C. maxima | Fujian | 194 | 9X218 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 296 | Jiabei6hao A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 93 | RTCU8401 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 195 | 9M34 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 297 | Jinbei No.5 A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 94 | Z10 B | C. moschata | Beijing | 196 | ZT5133 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 298 | Yinbei2hao A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 95 | RTCU4767 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 197 | Jindianjiuhao A | C. pepo | Tianjin | 299 | Jiangli5hao A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 96 | RTCU6730 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 198 | Zhongtai266 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 300 | Yinli6hao A | C. maxima | Anhui |

| 97 | RTCU6457 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 199 | Zhongtai13 A | C. pepo | Gansu | 301 | JSNO.7 A | C. pepo | Anhui |

| 98 | RWP9604 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 200 | ZT3H B | C. pepo | Gansu | 302 | Mingzhu1hao A | C. pepo | Anhui |

| 99 | RCH3063 B | C. moschata | Shandong | 201 | Nongren818 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 303 | Mingzhu6hao A | C. pepo | Anhui |

| 100 | Meiyasihao A | C. maxima | Anhui | 202 | Nongren778 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 304 | KN-11 A | C. pepo | Beijing |

| 101 | Jindian A | C. moschata | Xinjiang | 203 | Youhulü058 A | C. pepo | Shandong | 305 | Defeng No.4 A | C. pepo | Beijing |

| 102 | Lüfeicui A | C. moschata | Xinjiang | 204 | ZT17428 B | C. pepo | Gansu | 306 | Heibaoshi No.4 A | C. pepo | Beijing |

Note: A: Hybrid; B: Inbred line.

Table A2.

Information on 175 pairs of SSR primers.

Table A2.

Information on 175 pairs of SSR primers.

| Primer No. | Forward Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Reverse Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Primer Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| NG1 | CACCAAAATGGCCGCTCAAA | AGCTGCGACGAATGTGAAGA | Independent development |

| NG2 | CAGCTTCTTCAATCTCGCGC | CCTCCACAACAACAAGCAGC | Independent development |

| NG3 | GTGACCCAACTGACAGAGGG | TCGACTTCGAACGCAACAGA | Independent development |

| NG4 | GTGCCTTGGTTCTGTCGGTA | GCGCGCGTAAATATGTGTGT | Independent development |

| NG5 | CTCGTCGGGTCTTCGATCAG | AACAGTTCGCGTGCAACTTC | Independent development |

| NG6 | TGTGAAACGCCTCCAGTACC | GAGATCCGGTAAGCCACGAG | Independent development |

| NG7 | ACCTACCCCAGCCATACCAT | GATCGGCTGACGTCAATTGC | Independent development |

| NG8 | CGCGGTTGATCATTGTCGTC | CCATGCTGTGTGTGTGTGTG | Independent development |

| NG9 | GAATGAGCTTCGTCGAACGC | GCTCTGATCGGGGCTAGTTC | Independent development |

| NG10 | TGCATAGGTATCGGCAGCTG | AGTGGGTTCCAAGTGCAACA | Independent development |

| NG11 | GGCTGAGCCCCTCTTCAATT | CATCGTCGCCATTGCTTCTG | Independent development |

| NG12 | CAGAGGCTTGTTGTGTTGGC | CCACACTCGGAATTCCACGA | Independent development |

| NG13 | CCCTGGTTTTGGCTCCCTAG | CATGATGCGCACGAACTGAG | Independent development |

| NG14 | GATCAACGCAATACACCGGC | CTAGGTCGTCTTCGTCGTCG | Independent development |

| NG15 | CGGAATCGCCTGCAATTCAG | GGGAATTGGCGCGAAGAATC | Independent development |

| NG16 | TCATCCCAGGCATTTGGACC | GAATTTGACTCCGCCGCATC | Independent development |

| NG17 | GAGGCTAACGACGATGCGTA | CGTTACGTATCGCCGTCAGA | Independent development |

| NG18 | CGTTTATCTGTTGCTCGGCG | GAGGGATTCCAGGAGAGGGT | Independent development |

| NG19 | AGACCAAGCTCTATCCGGGT | GTTCGACGCTGCATCCATTC | Independent development |

| NG20 | GCCGACGGATCTTTTTACGC | CTGCAAACACGTCGTTTCGT | Independent development |

| NG21 | CGCCGAGTTTGAGTAATGCG | CCAAACTCCTCGACAACGGA | Independent development |

| NG22 | GAAGACGCCGATTTCGTTCG | CCATCATACGAGTGAGCGCT | Independent development |

| NG23 | CGTAACGTGCGAATCGTTCC | GACCGTCCAACCACCATGAT | Independent development |

| NG24 | GCCATAACTTGCTCTTCGCG | TGTTCCATAGCCGCCATTGT | Independent development |

| NG25 | CGGACTCTAGCGTCGAGTTC | CAACTTCCGAGAACGTGGGA | Independent development |

| NG26 | CGGCGTATGGCTCAGTACAT | ACCACAGCGTTGAAATTGGC | Independent development |

| NG27 | GATTTGCATCGGAACTCGGC | TCTGTTTCTCCAGCGGACAC | Independent development |

| NG28 | CATAGTCGCCTGATTCCGCT | CTTCGATTTCGCAGTCGCAG | Independent development |

| NG29 | GTTGTGCCATGACGGTCCTA | GAAAGCGGCGTTGATAGCAG | Independent development |

| NG30 | GTGGCCTCTGTTTGCACTTG | GACGTGTGATGAACGATGCG | Independent development |

| NG31 | GGAGGAAGAGAAGATCGCCG | GAGGCGAAAATGGCGGATTC | Independent development |

| NG32 | CTAAGCAGTAGTCGGCCTCG | CGTGAACTTTTGCAGCGTCA | Independent development |

| NG33 | GCCGTGTGAAAGGTTGTGAC | CCGCGTTTCGTTTGACTTGT | Independent development |

| NG34 | TTCGCGACTCCTAATCGACG | CGCACTTGTCGCTAATCGTG | Independent development |

| NG35 | GCCGCAGAAAAAGCACTTCA | CCCTAGCCCCTCTTCTTCCT | Independent development |

| NG36 | CCAATGGCGTTGCTAATCCG | CGTTAATCGGTTCGACGCAC | Independent development |

| NG37 | TCGCTGTTGGAGCTGTGAAT | GGCAACGTGTCGATCGATTG | Independent development |

| NG38 | ATGCCGCGTCATTCAAATCG | CTCATTGCTCGATGGCGTTG | Independent development |

| NG39 | CGCTTTCTCGTGCTCAATCG | GATTTGAACCGTATGCGCCC | Independent development |

| NG40 | GAAGCGACGGATTCAATGGC | TCACGTCGTGTTTTCAACGC | Independent development |

| NG41 | CCATCAGCAATGTCGAAGCG | GTGTTGTCGGCACAGTTGAC | Independent development |

| NG42 | TGGGATAAGGGCAGCCAAAG | GCGACTAGCGTTCGGGAATA | Independent development |

| NG43 | ACGTCGAACAAGCAAACGTG | CAATTGCCGATCAAGCCTCG | Independent development |

| NG44 | CCTCTTGATTTGCATCGCCG | CTACCAAGAAAATCGCCGCG | Independent development |

| NG45 | CACAGCCCAACTCAACAACG | TTCATGTGTTTGCTGCAGGC | Independent development |

| NG46 | GCCGCGTTTTGATGAGATCC | GCTCCATATGCCAGCAAACG | Independent development |

| NG47 | CACCAAAATGGCCGCTCAAA | CCTCTGCAACTTCGTCTCGT | Independent development |

| NG48 | GCAGCTTCTTCAATCTCGCG | CCTCCACAACAACAAGCAGC | Independent development |

| NG49 | GGTGACCCAACTGACAGAGG | TCGACTTCGAACGCAACAGA | Independent development |

| NG50 | ACCAACTGGAGCTCGAAAGG | GCTCTCGCAAATACCGCTTG | Independent development |

| NW1 | GCTTGAACAGAGATGGAGGG | AAAGTCGCTGAGAGCTGGAG | [29] |

| NW2 | GGTGCATTGTCCAAACACAA | CCGCATCCATGAAAGAAAGT | [29] |

| NW3 | ATTTGCTTACCAAACAGCCG | GTTCAGAGGAGCTGGGTACG | [29] |

| NW4 | GGACTTGAGATGGAGGTGGA | TTTGTACGTTGTTCGTTGCC | [29] |

| NW5 | TCGCTTCACCGGTAATTTTC | GCGCTGAAGAATCCATGTTT | [29] |

| NW6 | ACAACGAAGCCTCAAAGGAA | GATGCAAAGGATGGAAAGGA | [29] |

| NW7 | CTCAGTGGAGGGACAAGCTC | CCGACTCCACCATGTCCTAT | [29] |

| NW8 | ACCTCTGCATTTCAACCCAC | ATACCCACCAAGCCCTTTCT | [29] |

| NW9 | CTGTTGCTGTTGTTGCTGGT | GCGCTTCTCTCAATGCTTCT | [29] |

| NW10 | AGCTACGCATGCCTGAATCT | TGCACCTGCTGTCATAGCTC | [29] |

| NW11 | CATACCCACCGTCGACTCCT | GGGCGAAGTGGAGGTTATGA | [30] |

| NW12 | GTTGCTCCAACTCGATCTTCA | TTTCAAACGAGCACAAGCAC | [30] |

| NW13 | TAGTCGAGAAGGCCGAGAAG | AAATTCGACGACCGCTTG | [30] |

| NW14 | AAATTCGACGACCGCTTG | TTTTTAAAGGGCTGAAAATAATTG | [30] |

| NW15 | AAAATTGCTAGGCTGTAGTGGTG | AAAATTGCTAGGCTGTAGTGGTG | [30] |

| NW16 | TGTCAGCTTCCTCAGTAGGG | TGAACTGGGAGAGAGGTTTG | [30] |

| NW17 | TCCCATCCTCTACTGTTGCAC | TAAGTTGTGGGTGGGGAAAC | [30] |

| NW18 | ACCCCACCAAATTAATGCAG | AGAGCCCACTGTGATGACCT | [30] |

| NW19 | TGATTTGCGCACAAACAAAC | GCCAAAGGTTCCAAATGACA | [30] |

| NW20 | GCCAAAGGTTCCAAATGACA | TGATCGAATTGTGGCTGGT | [30] |

| NW21 | TGATCGAATTGTGGCTGGT | GTGGCCGTAGGTTTGTCAGT | [30] |

| NW22 | CACCTGGCTGTTTTGTCTGA | ACATGGGCATACCTCGAATC | [30] |

| NW23 | TGAAATGAACGCAGAATTGC | ACTTGCGGACTTTCACACCT | [30] |

| NW24 | TTTTTGAAATTCTTTGCATCACT | AAGCCAAAGCCCCTTATCT | [30] |

| NW25 | GCCAAAGGTTCCAAATGAC | GCAACAAATTGTAGTTGCAAAG | [30] |

| NW26 | CACGAAGATTTGATGGCCTTA | GGATTGGGATGGTGAAGATG | [31] |

| NW27 | GCAGAGGAGAAGTGGGTTTG | CTTTATCCGACCAAGCGTTC | [31] |

| NW28 | AGCCTTTCAGAAGAACCAAG | GGCTTCAAACAAATACTAACCA | [31] |

| NW29 | ATTAAATGCTCCTCCCCACC | GGAGAGAGAGGGAAAAACGG | [32] |

| NW30 | AGTCCGACGAAGCTCAGGTA | TACATGTCTCTGCGAGCGTC | [32] |

| NW31 | TCAATGGATCTGCCTTTTCC | AGGGAAGGATGCTAAGGAGC | [32] |

| NW32 | GGTGGGTATGGAGGAGGTG | ACCGCCACGTGGATAACTAA | [32] |

| NW33 | CCTTTCAAAATGGCTTCCAA | TCTTCTTCCCAAGCTGCCTA | [32] |

| NW34 | CAGACGGCTTTTGAAGGAAG | TCGAAGAGCTCTGTTGGTGA | [33] |

| NW35 | TTCTCAGGTGCTGTTGATGC | TCCTTTCCTTCGCTTCCTCT | [33] |

| NW36 | GCTTTTGAAGATGAGGCGAG | CACTCAAGCAGATTGCCAAA | [33] |

| NW37 | CGGTCGTGAATACATCATGG | GCTCCACCAATGGGAAACTA | [33] |

| NW38 | CGATATGATGGAGCTGCTGA | CCAGCTCCCGAGCTTCTAAT | [33] |

| NW39 | GAAGAGGAAGAAGCAGCACG | TGTCCACGATCTCTGCTTTG | [33] |

| NW40 | AGAGACGAGAATGGGGGAGT | GCGAAATCGGTGCAATAAAT | [33] |

| NW41 | TTTCTTTTCTCCTCTGCCCA | AATCACACCTTGGGCACTTC | [33] |

| NW42 | ATCATAGTCGTCGTCGGGTC | GCCGATTCTTGAGGAACAGA | [33] |

| NW43 | TTCAAAGCTTCTCTGGTAAGGC | ACATCGCCCAAGAGAAGTTG | [33] |

| NW44 | GAAGGCGAGGTTTTGAGTTG | GGCGGAACCCTAAGAAATGT | [34] |

| NW45 | TCGGACCAAAGTACCCTCCA | TCATCGCCGGTTGTGATCT | [34] |

| NW46 | GCACTTGAATCTTCGTCAAC | CGAGAAAGAATTAACGAGCA | [34] |

| NW47 | ATGGCTTCCAAGCTCCTCTT | GTCGGCCATGAGCTTGAG | [34] |

| NW48 | GAAGGACCGTGAGTGAAAGG | ATCTTGTGCCAAAGCTCCAT | [34] |

| NW49 | CAGGCTATTCGCACCCTCTA | CCTCATGCATTTTGCGTGTA | [34] |

| NW50 | CGTGAACATTCGTTTGTTGG | TCATCCGTTTCCTTTTCAGC | [34] |

| NW51 | TCACTTTACAACCAGAAGCTGA | CACTTTGCTGCTCATCCAC | [34] |

| NW52 | GGCTGGCTCATAAAGAAAGC | GGGGTTTTTGAAGATGCTTG | [34] |

| NW53 | ATGATGGAGTCCCAGTCGAG | ACCCACACACCCTCTCCTC | [34] |

| NW54 | ATCCACAAACAAGGCACCTC | GTAGTGGAGGCTCGGGTGTA | [34] |

| NW55 | CACAAGCCATCACACAAACC | AGGTGGAGCTGACCGTAGTG | [34] |

| NW56 | TCTCACTCATCCACCACACC | CGTTTCGAGTCATTTGTTCG | [34] |

| NW57 | CCTCTCATTCTTCCCCATCTC | TGATCCGGTAGGGGTCTACTC | [34] |

| NW58 | GCCCAGAAGACAAAAGTTCG | TTTTTGTGTGCGTGTGTGG | [34] |

| NW59 | ATTGGTGCCGAAGCTATCAC | CCCACGTTATGGAGCAGAAT | [34] |

| NW60 | ATGCTCAGACATCCATGCAC | GCGAAAGATTACCGATGCTC | [34] |

| NW61 | AACACTCGGCCACAACATC | CTCCTTGTAAAACGGGTTGC | [34] |

| NW62 | CTCCATTCCCATGGCTTC | CCATGAGCTTGAGAGAGGTG | [34] |

| NW63 | CAAATTCAGACGCTTCTTTTGG | AGAATTGAGCAAAAAGGAGATGG | [34] |

| NW64 | TTAAGATAGTTTCAGGATTCCATGT | AGGAGTTTGAAACAAATGAAGG | [34] |

| NW65 | GAGTGATGTTTTGAGTAAACAG | CTTGTTCATCATCATCTGTG | [34] |

| NW66 | AGGTGGCATCTGTACACTGAG | TGAACAAACTCCACACCAATAG | [34] |

| NW67 | GACAGGACAGGTCAACACCTC | AACCCAATTGCACAGCTTCT | [34] |

| NW68 | TGTTCAGTAGCCATTGATCTATCC | TGGATGACTTCTGGGTTGGT | [34] |

| NW69 | TTATAAGAATGATGTTACTCGAT | CATCATCATACATCTTACATTG | [34] |

| NW70 | GAACTCTAATCCAGCCGTTG | TTAAAATAAATGGAGCAAATAATGAG | [34] |

| NW71 | GGTCAAATTCAAGGGCTTACC | AGGAGCATCCTTGTCGTTGT | [34] |

| NW72 | CTGGTTTTTCCACACAGAATCA | CCCAGAAGGGAATTGAAACA | [34] |

| NW73 | CCGCCACCACTGAACAACT | GGCTGTGGCCCTCCATAGT | [34] |

| NW74 | TCACAAAGTCAAAACAGACAAACA | TGTTTCAGGGAAATGAAGAGG | [34] |

| NW75 | GGCGAAAAGGAAGAACGAAT | TTTTTCTCCCCCTTCCACAT | [34] |

| NW76 | ACCTACCGTCACACCCACAT | CCACCTGAAAACAGGGCTAA | [34] |

| NW77 | GAACTTCGTGTGTGCGTGTC | TTGCTGGAACTTCCTCTCGT | [34] |

| NW78 | CTCTCCCCCTCCTCCACTC | GCGTTCTGCATTGTGGAAGT | [34] |

| NW79 | CAAATTTTCTTCTACAATTTGGT | GTGAATGAACATGCGTCTC | [34] |

| NW80 | ATGGAGACGCGCAAGTAGAT | ACCTCGAGGAAGCAAAAATG | [34] |

| NW81 | TATGTAGCGCTCTGCACAAT | CCTCAATGTAATGTTTTGAATCC | [34] |

| NW82 | TGAAACTACACTACATGACCTTGG | TGGGTTGGTAGACTTGTAGTTGA | [34] |

| NW83 | CATCAGGTTATTGAGTTTTACTCAGAC | TCGTCTGCCCCAATAATTC | [34] |

| NW84 | CGTGTTTGTGTTGGAAAAGC | AAGCAAACCCACAGAAGGAG | [34] |

| NW85 | ACGTTCTTTCTGCCTCCAT | ATGCCCATTATGCAATTCTC | [34] |

| NW86 | ACAATGGTTCTTTTGATCCTTGA | TGCAAACAATGTGTGTGTGTG | [34] |

| NW87 | TGTGGGGTTTTGCTTTTAGG | ATCCAAAATGGTGGTGCATT | [35] |

| NW88 | GCAAGCCCTAGCTGATTTTT | GGGCGAAAACAGAGTGAGAG | [35] |

| NW89 | AACAGAGAATCTGGTGCTGGA | GCCAATTCCTCCTTTTCTCC | [35] |

| NW90 | GGATTGCCTTGCTGGAGAG | CAAATCCAGGTGGAAGGCTA | [35] |

| NW91 | TCACCAACTTGCCATAGACG | CGCGCAACTGATAAGGATTT | [35] |

| NW92 | TGATCTGACAGCAACCGAAG | CCATTCCCTTAGTTTCTAAACCACT | [35] |

| NW93 | TGATGACAAAGAAGCCATCG | ATCTTATGCCGGAGCAGATG | [35] |

| NW94 | TTTCGTTGCAGAGAATGGTG | CCCATTTCTTTCTCGCTCAA | [35] |

| NW95 | AATTCTAACCGTTGGGGGTT | CCCAGAAACGAAAGAAGCAG | [35] |

| NW96 | ATGGCATAATCAGCCCTCAC | TTTGAAGAAGGGAAGAGGGG | [35] |

| NW97 | TCAAACTCTCAACTGGGTCG | TCCGATTGAGAGCTGGAGTT | [35] |

| NW98 | TCCTCGTCGGAACAGAACTT | TCTAACTTGGAGCCTGGAGC | [35] |

| NW99 | GAGCTTCTGGATGATAGCGG | GCTTCGAACTTTCGTTTGCT | [35] |

| NW100 | TGTAATTTGAAGATGAGATTATGAAGA | GGGTCTTGTTTCTCGAGCTG | [35] |

| NW101 | TTTCAAATTCGCTCGTTTCC | GAGTCGTCGATGTCGTCAAA | [35] |

| NW102 | TCTCGAATCCGAAGAAATCG | TGCGTTGCAGAATATCAAGC | [35] |

| NW103 | GGGTGAAGCTGTGGATTCAT | TCTCTAGTGCCACACTCAAGTACA | [35] |

| NW104 | GTGGGCTAAGTTCAAATCGTTC | GAACCCAATCTTCTCATTTCCA | [36] |

| NW105 | CAAGCCTTTACCAAAACCAAAC | ACGATCTTCCTCCTCCTCTTCT | [36] |

| NW106 | GAACCTCGTTGCTGGTTCTTCT | TCTAGCATCTTACGCACGCTTC | [36] |

| NW107 | TGTCAAATTCGCTTCCATCATC | ACGACTGTGAGAACGGTGAAAA | [36] |

| NW108 | TGGAATCCAGAGACTGATGAAG | CACGATTCCGATAACAACAAGA | [36] |

| NW109 | TGGAGGTATCCTTCCGTATGTT | CATACGGGAGTTTCGTTTTTCT | [36] |

| NW110 | ATCCCAGGTCCCAATTTTCTTC | CCATACCTGAGGGACCTGAAAC | [36] |

| NW111 | CGAATTTCTCCGAAAAGAAACC | CCTCGATCAATCCTCCTACACC | [36] |

| NW112 | CGACTACAGCTCAACAAAGACC | GAAGTCTATTACGCCCAATTCC | [36] |

| NW113 | CGAGTACGTTTACAACCATCCA | CAACTCTCAACAAGAACCCAAG | [36] |

| NW114 | TCTTCTCGGAGTTTGATGTCCA | TTTACCCTCATCGGAACCTCAT | [36] |

| NW115 | GACACTCACGAGCAAAATGACC | CGTGTGGAGCTTTCTCACAACT | [36] |

| NW116 | GCAGCACACTCGATTCCTCTTT | TAGGAAAAATGGCGGTGAAGAA | [36] |

| NW117 | AGACTTTGGGTTTGTAGGAAGG | GCTAAGCATTGTTAGGGCTTCT | [36] |

| NW118 | GACGAATACTTTCGCAATCAAG | CATGTGGAAGTTGTTGTTGTTG | [36] |

| NW119 | CTAATCAGGCTGGCCAAGAAGA | CGACGTTACCGACAAGATTTCC | [36] |

| NW120 | AGCACTGGGTTAACAGAGGAAA | ATGATACAGTAATCGGCGTCCT | [36] |

| NW121 | TGTGATTTGTTGGGCTCTCTGT | ACATGGAAATCCACCTCTTCGT | [36] |

| NW122 | TCCACACCAGTGGTTCTTTCGT | TTTCACCATCCGGACAATCATC | [36] |

| NW123 | GCCGGTGATTCTGGATGAAGTA | CAGGTAGAAGGTGGGGAGATGG | [36] |

| NW124 | TTGGACAATCTGAGGAAGTTGG | AAGGTTTGTCCTTCGACAAGGT | [36] |

| NW125 | CCCTCGGTAGCAATTTTGTAGT | TTTGGTGGGAGTGATACTGATG | [36] |

Table A3.

Detailed information on the phenotypic traits of Cucurbita moschata.

Table A3.

Detailed information on the phenotypic traits of Cucurbita moschata.

| No. | Trait Name | Observation Method | Trait Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cotyledon Shape | VG | PQ |

| 2 | Main Vine Length | MS | QN |

| 3 | Leaf Size | MS | QN |

| 4 | Degree of Leaf Margin Incision | VG | QN |

| 5 | Greenness of the Front Leaf Surface | VG | QN |

| 6 | Presence or Absence of White Spots on the Front Leaf Surface | VG | QL |

| 7 | Petiole Length | MS | QN |

| 8 | Petiole Thickness | MS | QN |

| 9 | Greenness of the Melon Rind | VG | QN |

| 10 | Fruit Longitudinal Diameter | MS/VG | QN |

| 11 | Fruit Transverse Diameter | MS/VG | QN |

| 12 | Ratio of Fruit Longitudinal Diameter to Transverse Diameter | MS/VG | QN |

| 13 | Position of the Maximum Transverse Diameter of the Fruit | VG | QN |

| 14 | Fruit Shape | VG | PQ |

| 15 | Prominence of the Melon Neck | VG | QN |

| 16 | Melon Neck Length | VG | QN |

| 17 | Degree of Fruit Curvature | VG | QN |

| 18 | Shape of the Fruit Stalk | VG | PQ |

| 19 | Shape of the Fruit Navel | VG | QN |

| 20 | Presence or Absence of Fruit Furrows | VG | QL |

| 21 | Spacing of Fruit Furrows | VG | QN |

| 22 | Depth of Fruit Furrows | VG | QN |

| 23 | Patterns on the Fruit Surface | VG | QN |

| 24 | Maturity Period | VG | QN |

| 25 | Main Color of the Fruit Peel | VG | PQ |

| 26 | Depth of the Main Color of the Fruit Peel | VG | QN |

| 27 | Presence or Absence of Wax Powder on the Fruit Surface | VG | QL |

| 28 | Presence or Absence of Fruit Nodules | VG | QL |

| 29 | Main Color of the Fruit Pulp | VG | PQ |

| 30 | Thickness of the Fruit Pulp | VG | QN |

| 31 | Diameter of the Fruit Navel | VG | QN |

| 32 | Seed Length | VG | QN |

| 33 | Ratio of Seed Width to Length | VG | QN |

| 34 | Color of the Outer Seed Coat | VG | PQ |

| 35 | Presence or Absence of the Outer Seed Coat | VG | QL |

Note: VG: visual assessment of a group; MS: measurement of individual; PQ: pseudo-qualitative characteristics; QN: quantitative characteristics; QL: qualitative characteristics.

Table A4.

Detailed information on the phenotypic traits of Cucurbita pepo.

Table A4.

Detailed information on the phenotypic traits of Cucurbita pepo.

| No. | Trait Name | Observation Method | Trait Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cotyledon Shape | VG | PQ |

| 2 | Cotyledon Cross-Section Shape | VG | PQ |

| 3 | Presence of Inner Corolla Wreath in Female Flowers | VG | QL |

| 4 | Color of Inner Corolla Wreath in Female Flowers | VG | PQ |

| 5 | Color Intensity of Inner Corolla Wreath in Female Flowers | VG | QN |

| 6 | Presence of Inner Corolla Wreath in Male Flowers | VG | QL |

| 7 | Color of Inner Corolla Wreath in Male Flowers | VG | PQ |

| 8 | Color Intensity of Inner Corolla Wreath in Male Flowers | VG | QN |

| 9 | Color of Male Flower Corolla | VG | PQ |

| 10 | Shape of Male Flower Tube | VG | PQ |

| 11 | Apex Shape of Male Flower Petals | VG | PQ |

| 12 | Shape of Male Flower Buds | VG | PQ |

| 13 | Length of Male Flower Sepals | VG | QN |

| 14 | Plant Growth Habit | VG | PQ |

| 15 | Presence of Plant Branches | VG | QL |

| 16 | Number of Plant Branches | MS | QN |

| 17 | Stem Color | VG | PQ |

| 18 | Greenness Intensity of Stem | VG | QN |

| 19 | Presence of Stem Patterns | VG | QL |

| 20 | Presence of Stem Tendrils | VG | QL |

| 21 | Leaf Shape | VG | PQ |

| 22 | Leaf Margin Shape | VG | PQ |

| 23 | Leaf Size | MS | QN |

| 24 | Degree of Leaf Sinus | VG | QN |

| 25 | Greenness Intensity of Leaf Adaxial Surface | VG | QN |

| 26 | Presence of White Spots on Leaf Adaxial Surface | VG | QL |

| 27 | Area of White Spots on Leaves | VG | QN |

| 28 | Size of Commercial Fruit | MS | QN |

| 29 | Presence of Fruit Neck in Commercial Fruit | VG | QL |

| 30 | Curvature of Fruit Neck in Commercial Fruit | VG | QL |

| 31 | Number of Fruit Surface Colors in Commercial Fruit | VG | QL |

| 32 | Primary Color of Commercial Fruit Surface | VG | PQ |

| 33 | Color Intensity of Primary Fruit Surface Color | VG | QN |

| 34 | Glossiness of Commercial Fruit Surface | VG | QN |

| 35 | Type of Fruit Surface Patterns | VG | PQ |

| 36 | Color of Primary Fruit Surface Patterns | VG | PQ |

| 37 | Size of Flower Scar on Commercial Fruit | VG | QN |

| 38 | Morphology of Flower Scar End | VG | QN |

| 39 | Length of Fruit Stalk | MS | QN |

| 40 | Color of Fruit Stalk | VG | PQ |

| 41 | Overall Shape of Mature Fruit | VG | PQ |

| 42 | Length of Mature Fruit | MS | QN |

| 43 | Maximum Diameter of Mature Fruit | MS | QN |

| 44 | Fruit Shape Index (Length/Diameter Ratio) | MS | QN |

| 45 | Primary Color of Mature Fruit Surface | VG | PQ |

| 46 | Color Intensity of Primary Mature Fruit Surface Color | VG | QN |

| 47 | Secondary Color of Mature Fruit Surface | VG | PQ |

| 48 | Type of Mature Fruit Surface Patterns | VG | PQ |

| 49 | Presence of Fruit Furrows | VG | QL |

| 50 | Depth of Fruit Furrows | VG | QN |

| 51 | Presence of Fruit Ridges | VG | QL |

| 52 | Color of Fruit Ridges | VG | QL |

| 53 | Presence of Fruit Nodules | VG | QL |

| 54 | Number of Fruit Nodules | VG | QN |

| 55 | Color of Fruit Pulp | VG | PQ |

| 56 | Structure of Fruit Pulp | VG | PQ |

| 57 | Seed Size | VG | QN |

| 58 | Seed Shape | VG | PQ |

| 59 | Presence of Outer Seed Coat | VG | QL |

| 60 | Color of Outer Seed Coat | VG | PQ |

| 61 | Color of Inner Seed Coat | VG | PQ |

Table A5.

Detailed information on the phenotypic traits of Cucurbita maxima.

Table A5.

Detailed information on the phenotypic traits of Cucurbita maxima.

| No. | Trait Name | Observation Method | Trait Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cotyledon Shape | VG | PQ |

| 2 | Main Vine Length | MS | QN |

| 3 | Main Vine Color | VG | PQ |

| 4 | Number of Lateral Branches | MS | QN |

| 5 | Leaf Size | MS | QN |

| 6 | Degree of Leaf Margin Incision | VG | QN |

| 7 | Greenness of Adaxial Leaf Surface | VG | QN |

| 8 | Density of White Spots on Adaxial Leaf Surface | VG | QN |

| 9 | Initial Flowering Stage | VG | QN |

| 10 | Yellowness of Female Flower Corolla | VG | QN |

| 11 | Length of Female Flower Sepals | MS | QN |

| 12 | Length of Male Flower Sepals | MS | QN |

| 13 | Fruit Longitudinal Diameter | MS/VG | QN |

| 14 | Fruit Transverse Diameter | MS/VG | QN |

| 15 | Ratio of Fruit Longitudinal to Transverse Diameter | MS/VG | QN |

| 16 | Fruit Shape | VG | PQ |

| 17 | Position of Maximum Fruit Transverse Diameter | VG | QN |

| 18 | Outline of Fruit Stalk End | VG | PQ |

| 19 | Outline of Flower Stalk End | VG | PQ |

| 20 | Presence/Absence of Fruit Furrows | VG | QL |

| 21 | Spacing of Fruit Furrows | VG | QN |

| 22 | Depth of Fruit Furrows | VG | QN |

| 23 | Number of Fruit Peel Colors | VG | QN |

| 24 | Primary Color of Fruit Peel | VG | PQ |

| 25 | Intensity of Primary Fruit Peel Color | VG | QN |

| 26 | Secondary Color of Fruit Peel | VG | PQ |

| 27 | Intensity of Secondary Fruit Peel Color | VG | QN |

| 28 | Distribution Pattern of Secondary Fruit Color | VG | PQ |

| 29 | Lignification Status of Fruit Peel | VG | PQ |

| 30 | Diameter of Flower Stalk Base | VG | QN |

| 31 | Primary Color of Fruit Pulp | VG | PQ |

| 32 | Seed Size | VG | QN |

| 33 | Seed Shape | VG | PQ |

| 34 | Seed Coat Color | VG | PQ |

| 35 | Surface Texture of Seed Coat | VG | PQ |

Table A6.

Allele dropout detection and null allele detection for 24 pairs of SSR primers.

Table A6.

Allele dropout detection and null allele detection for 24 pairs of SSR primers.

| Marker | Missing Rate | Null Alleles Detection |

|---|---|---|

| NG2 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW1 | 1.31% | Existence |

| NW112 | 1.31% | Existence |

| NW121 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW124 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW125 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW18 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW22 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW23 | 0.33% | Existence |

| NW26 | 0.33% | Existence |

| NW37 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW42 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW44 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW5 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW51 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW56 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW57 | 0.98% | Existence |

| NW59 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW63 | 0.00% | Existence |

| NW66 | 0.33% | Existence |

| NW84 | 0.98% | Existence |

| NW85 | 0.98% | Existence |

| NW87 | 0.33% | Existence |

| NW98 | 0.33% | Existence |

Table A7.

Detailed information on the four marker combinations with weak linkage relationships.

Table A7.

Detailed information on the four marker combinations with weak linkage relationships.

| Marker Pairs | r² Value | Linkage Strength |

|---|---|---|

| NW1 & NW121 | 0.46 | Weak linkage |

| NW5 & NW51 | 0.44 | Weak linkage |

| NW18 & NW22 | 0.42 | Weak linkage |

| NW37 & NW42 | 0.41 | Weak linkage |

References