Abstract

The soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines, SCN) is the leading pathogen causing economic losses in soybean production worldwide. Using resistant cultivars is the most sustainable control method, yet the molecular basis of this resistance remains unclear. Heinong 531 (HN531), a high-yield soybean variety rich in seed oil, shows broad resistance to multiple SCN races. In this research, we studied HN531’s resistance to SCN races 3 and 5 through phenotypic assessment and comparative transcriptomics. Although initial infection rates were similar between resistant HN531 and the susceptible Dongsheng 1 (DS1), HN531 limited later nematode development inside roots, with fewer progressing to the J2 stage and maturing females. RNA-seq at 5 days post-infection revealed 1459 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in HN531, mainly involved in secondary metabolite pathways, especially phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. We pinpointed a β-glucosidase gene (Glyma.12G053800, BGLU) upregulated after SCN infection and naturally more expressed in HN531 roots than DS1. Functional tests using Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation showed that overexpressing Glyma.12G053800 in the susceptible DS1 significantly decreased SCN development and adult female counts by around 65%, without affecting initial infection. These findings suggest Glyma.12G053800 contributes to SCN resistance via phenylpropanoid-driven secondary metabolism, offering new insights into nematode resistance pathways and a valuable genetic resource for breeding broad-spectrum resistant soybean varieties.

1. Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) is a vital global food and cash crop, but its yield and quality are affected by various biotic and abiotic stresses [1,2]. The soybean cyst nematode (SCN; Heterodera glycines Ichinohe) is the most economically damaging pathogen impacting soybean production worldwide [3]. In recent decades, SCN has become the leading cause of yield loss in U.S. soybean fields and remains a major threat to soybean farming in Brazil and China [4]. The subtle symptoms of SCN damage make disease management challenging. Unlike many pathogens that produce clear aboveground signs, fields infested with SCN often show few visible indications [5,6]. Plants with 5–10% yield losses usually look identical to healthy plants in height, greenness, and overall vigor, making visual detection very difficult [7,8].

The life cycle of SCN begins when second-stage juveniles (J2) hatch from cysts in the soil and migrate toward soybean roots, guided by chemical signals released by the host plant [9,10]. Upon locating a suitable penetration site, J2 larvae penetrate the root epidermis using their stylet, a needle-like mouthpart, and migrate intracellularly through the root cortex to reach the vascular cylinder [11,12]. Once positioned adjacent to the vascular tissues, the nematode selects an initial syncytial cell and injects effector proteins that reprogram the cell’s developmental fate, inducing it to undergo cell wall dissolution and fusion with neighboring cells to form a multinucleate syncytium [13,14]. This syncytium serves as the nematode’s sole nutrient source throughout its sedentary parasitic phase, during which the nematode undergoes three successive molts (J2 → J3 → J4 → adult) while remaining attached to the feeding site [15]. Female nematodes eventually develop into cyst-forming adults, each producing hundreds of eggs that remain protected within the cyst after the female dies, ensuring the pathogen’s persistence and dispersal [16]. Management of SCN has proven challenging due to the nematode’s wide host range, extended survival capacity in soil (up to 9 years within cysts), and rapid evolution of virulent populations capable of overcoming deployed resistance genes [17,18]. Cultural practices such as crop rotation with non-host plants can reduce nematode populations but are often insufficient for adequate control in heavily infested fields [19,20]. Chemical nematicides provide temporary suppression but raise environmental and economic concerns, making them impractical for large-scale application [21,22]. Consequently, the deployment of genetically resistant soybean cultivars represents the most effective, economical, and environmentally sustainable strategy for SCN management [23,24].

Natural resistance to SCN in soybean has been identified in several plant introductions (PIs), with PI 88788 and Peking among the two most widely used sources of resistance in commercial breeding programs [25,26,27]. Genetic and molecular analyses have revealed that SCN resistance in these sources is primarily conferred by two major quantitative trait loci (QTLs): rhg1 (resistance to Heterodera glycines 1) on chromosome 18 and Rhg4 on chromosome 8 [28,29]. The rhg1 locus has been extensively characterized and shown to harbor copy-number variations in three genes encoding an amino acid transporter, an α-SNAP protein, and a wound-inducible domain protein, which collectively contribute to resistance through mechanisms that disrupt vesicular trafficking and induce localized cell death at feeding sites [30,31]. The Rhg4 locus encodes a serine hydroxy methyltransferase that also contributes to resistance, with synergistic effects observed when both loci are present [30]. However, the extensive reliance on PI 88788-derived resistance in commercial soybean production has led to the emergence of virulent SCN populations capable of reproducing on previously resistant cultivars, a phenomenon documented in multiple soybean-growing regions [8,15]. This decline in resistance challenges sustainable SCN management and raises concerns about the durability of single-source resistance strategies [4,13]. Although the high copy number of the rhg1-b allele provides strong initial resistance, it becomes vulnerable under selection pressure when deployed across millions of hectares, leading to field populations that can evade this resistance [32]. To combat the decline of natural plant resistance, researchers have actively explored alternative and complementary control methods. One promising strategy is to create plant-incorporated protectants containing Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) delta-endotoxins with nematocidal properties [33]. For instance, transgenic soybean lines expressing the Cry 14 Ab protein, a Bt toxin effective against nematodes, have shown significant success against H. glycines in both greenhouse and field tests [34,35]. In comparative experiments, soybean plants that produce Cry 14 Ab had markedly fewer cysts and eggs than control plants with only the rhg 1-b allele, highlighting the potential of this biotechnological approach to address the limitations of natural resistance genes [36]. Additionally, other Bt proteins such as Cry 6 Aa and Cry 5 B have been found to be effective against plant-parasitic nematodes, broadening the scope of possible biocontrol agents [37]. Integrating these plant-incorporated protectants with natural resistance genes can lead to more durable, broad-spectrum defense by pyramiding resistance genes and deploying multiple, independent resistance mechanisms [38,39]. Overall, combining various plant-nematode interaction strategies presents a promising pathway toward sustainable management of SCN [21,40]. This adaptation highlights the urgent need to identify and characterize novel sources of SCN resistance with different genetic bases and mechanisms of action, which can be pyramided with existing resistance genes to develop more durable resistance [11,41]. Additionally, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying different types of resistance responses, including pre-penetration resistance that prevents nematode entry, post-penetration resistance that disrupts feeding site establishment or nematode development, and tolerance that maintains yield despite nematode infection, is essential for strategic resistance deployment [15,27]. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies and functional genomics have enabled comprehensive characterization of plant-nematode interactions at the molecular level [41]. Transcriptomic studies comparing resistant and susceptible soybean genotypes during SCN infection have revealed complex transcriptional reprogramming involving defense signaling pathways, reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism, cell wall modification, hormone signaling, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis [29,42].

In this study, we characterized the SCN resistance mechanisms in soybean line HN531, which exhibits strong resistance to multiple SCN races. Through integrated phenotypic analysis, comparative transcriptomics, and functional genomics approaches, we sought to determine the resistance type and identify the developmental stage at which nematode growth is arrested in HN531, to identify differentially expressed genes and enriched pathways associated with the resistance response through RNA-sequencing and bioinformatic analysis, and to identify and functionally validate candidate resistance genes through overexpression studies in susceptible soybean background. Our findings reveal that HN531 employs post-penetration resistance mechanisms involving extensive transcriptional reprogramming of defense-related pathways, and we identify Glyma.12G053800, encoding a beta-glucosidase, as a novel contributor to SCN resistance. These results provide new insights into the molecular basis of SCN resistance and offer valuable genetic resources for developing improved resistant soybean cultivars.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

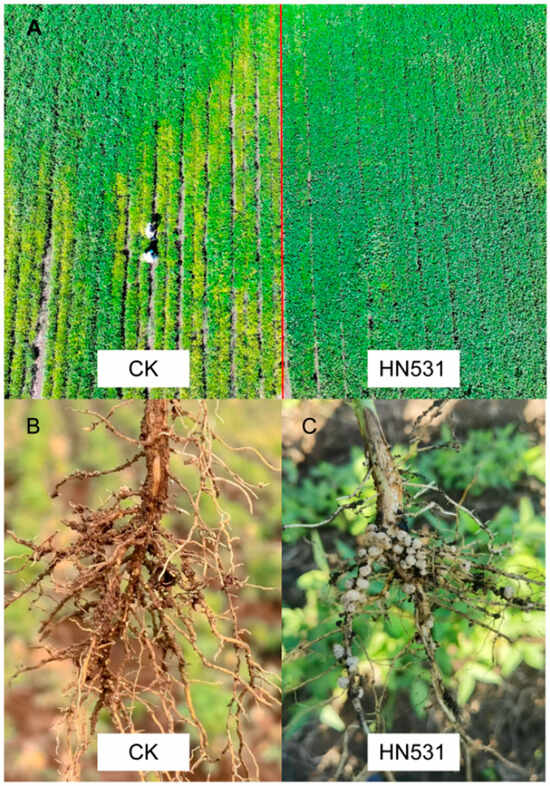

The soybean cultivars Dongsheng 1 (DS1) and Heinong 531 (HN531) used in this study were obtained from the Soybean Research Institute of the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Harbin, China. DS1 functions as a susceptible control, while HN531 is a resistant genotype carrying Peking-type resistance genes (Figure 1). Field evaluation of SCN resistance was conducted in a naturally infested field plot at the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences during the 2023 growing season. The test field was confirmed to contain SCN race 3 with a soil cyst density of 32 ± 5 cysts per 100 g dry soil. Seeds were sown on 6 May 2023, and cyst numbers on root systems were counted 25 days after seedling emergence. The highly susceptible cultivar Lee 68 was included as a negative control. For controlled environment experiments, plants were grown in individual plastic pots (10 cm diameter × 14 cm height) filled with a 1:1 (v/v) autoclaved sand-soil mixture. All plants were maintained in a growth chamber (Ningbo Jiangnan Instrument Factory, Ningbo, China) under the following conditions: 25 ± 2 °C, 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, 20,000 lux, and 60–70% relative humidity. After the first trifoliate leaves fully expanded (approximately 10 days after planting), seedlings were inoculated with either SCN race 3 or race 5 at a density of 500 s-stage juveniles (J2) per plant for resistance phenotyping or 200 J2 per plant for detailed developmental studies. Each treatment was replicated five times, with Lee 68 serving as the susceptible control.

Figure 1.

Field performance of HN531 and cyst numbers on roots in naturally infested soil. (A) Aerial view of field trial showing contrasting growth of the susceptible control variety (CK, left side) and resistant variety HN531 (right side) in SCN race 3-infested soil (32 ± 5 cysts per 100 g dry soil). (B) Root system of susceptible control (CK) showing extensive white female cyst formation. Numerous white, lemon-shaped cysts (mature females) are visible protruding from the root surface, particularly on lateral roots. The heavy cyst burden indicates successful nematode reproduction and severe infestation. (C) Root system of resistant variety HN531 showing dramatically reduced cyst formation under the same field conditions. Cream-colored structures on roots are SCN cysts.

2.2. SCN Populations and Maintenance

Soybean cyst nematode populations (races 3 and 5) were supplied by the Soybean Research Institute of Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun, China. Race identity was verified using the standard HG-type test on differential host lines [43]. SCN populations were continuously propagated on the susceptible soybean cultivar DS1 to maintain virulence. For nematode multiplication, three plants were grown per pot (18 cm diameter × 19 cm height) containing a 1:1 (v/v) sand-soil mix. Plants were kept in a controlled environment chamber at 25 ± 2 °C, with a light intensity of 20,000 lux and a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle. Inoculation was performed when the first trifoliate leaves fully expanded, and mature cysts were harvested 35 days post-inoculation (dpi) for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Extraction of Second-Stage Juveniles (J2)

Mature cysts were collected from both soil and root systems 35 days after inoculation using a modified wet-sieving and flotation method. Roots and associated soil were thoroughly washed over a series of nested sieves (750 μm, 190 μm, and 75 μm mesh). Cysts retained on the 190 μm sieve were collected, transferred to a 75 μm mesh, and carefully crushed with a rubber pestle. The resulting suspension containing eggs was passed through a 25 μm sieve to collect purified eggs. Egg quality and quantity were assessed microscopically with a hemocytometer. For J2 extraction, eggs were placed in a modified Baermann funnel lined with double-layered tissue paper (Kimwipes, Kimberly-Clark, Irving, TX, USA), suspended over sterile distilled water with 3 mM ZnSO4 to stimulate hatching. The hatching chambers were kept at 28 °C in darkness with daily water replenishment to maintain humidity. Second-stage juveniles were collected during the peak hatching period (72–120 h), and their viability was confirmed by observing motility under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX16, Tokyo, Japan). J2 concentration was determined using a counting chamber, and suspensions were diluted to the desired density (1000 J2/mL) immediately before inoculation.

2.4. Nematode Infection Rate Determination

To evaluate initial penetration efficiency, soybean seedlings were carefully uprooted 48 h after inoculation with J2. Roots were gently rinsed under running tap water to remove adhering sand and soil particles. Surface sterilization was performed by immersing roots in a 15% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution for 4 min, followed by thorough rinsing under running tap water for 5 min to remove residual chlorine. Next, roots were transferred to 50 mL conical flasks containing 35 mL of distilled water and 2 mL of acid fuchsin staining solution (3.5% acid fuchsin in 25% glacial acetic acid). The flasks were heated on a hot plate until boiling, maintained for 15 s, then cooled to room temperature. Excess stain was removed by rinsing roots multiple times with sterile distilled water until the wash water remained clear. Stained roots were examined under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX16, Tokyo, Japan), and the number of J2 nematodes within each root system was counted. The infection rate was calculated as: (number of J2 inside roots/number of J2 inoculated) × 100%. The experiment included three independent biological replicates, with at least 10 plants analyzed per treatment in each replicate.

2.5. Nematode Development Assessment

To monitor SCN developmental progression within host roots, plants were sampled at 5 and 12 dpi. Root systems were carefully excavated and gently washed with tap water to remove soil debris. Nematode staining was performed using the acid fuchsin method. After staining and destaining, roots were mounted on glass slides and examined under a compound light microscope (Olympus BX53, Tokyo, Japan) at 100× magnification. Nematode developmental stages were classified based on morphological features: J2 larvae (vermiform with undeveloped reproductive structures), J3 larvae (slightly swollen body, developing reproductive primordium visible), and J4 larvae (pronounced body swelling, well-developed reproductive structures). For each root system, at least 50 nematodes were examined and categorized by developmental stage. The proportion of each stage was calculated as a percentage of the total nematodes observed. Three independent biological replicates were performed, with at least 10 plants analyzed per treatment in each replicate.

2.6. Female Cyst Enumeration

At 21 days after inoculation, when nematodes develop into the white female stage, soybean roots were carefully dug out from the pots. They were gently rinsed with tap water to eliminate sand and soil, then blotted dry with absorbent paper to remove surface moisture. The number of white females—easily seen as white, lemon-shaped structures emerging from the roots—was counted using a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX16, Tokyo, Japan). The female index (FI) was calculated with the formula: FI = (average number of females on test cultivar/average number of females on the susceptible control Lee 68) × 100. According to the standard classification, FI < 10% indicates high resistance, 10–30% indicates moderate resistance, 30–60% indicates moderate susceptibility, 60–90% indicates moderate susceptibility, and >90% indicates susceptibility. The experiment was performed with three independent biological replicates, each including at least 20 plants per treatment.

2.7. RNA Extraction and Transcriptome Sequencing

For transcriptomic analysis, soybean roots were harvested at 5 dpi after SCN race 3 J2 infection. This time point was selected based on preliminary experiments showing significant differences in nematode development between HN531 and DS1. Main roots containing established nematodes were excised, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Non-inoculated control plants were processed identically. Total RNA was extracted using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was verified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 7.0 considered acceptable for library construction. Strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were constructed from 1 μg total RNA using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Library quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, and quantification was performed using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Three independent biological replicates were sequenced for each treatment group: DS1 control (DS1-CK), DS1 infected (DS1-SCN), HN531 control (HN531-CK), and HN531 infected (HN531-SCN).

2.8. Transcriptome Data Analysis

Raw sequencing reads were processed using fastp v0.20.1 [31] to remove adapter sequences, low-quality bases (Q < 20), and reads shorter than 50 bp. Ribosomal RNA sequences were identified and removed by mapping reads to the rRNA database using Bowtie2 v2.4.2 [44]. Clean reads were mapped to the Glycine max reference genome (Wm82.a4.v1) downloaded from Phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/, accessed on 18 May 2025) using HISAT2 v2.2.1 [45] with default parameters. Mapped reads were assembled and quantified using StringTie v2.1.4. Gene expression levels were calculated as Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) and raw read counts using RSEM v1.3.3. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 v1.30.0 [37] with the following criteria: |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. Genes meeting these criteria were designated as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the GOseq R. V 4.4.3. package with Wallenius non-central hypergeometric distribution to account for gene length bias. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was conducted using KOBAS 3.0. GO terms, and KEGG pathways with corrected p-value < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched.

2.9. Phylogenetic Analysis

The amino acid sequence of Glyma.12G053800 was retrieved from Phytozome v13 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/, accessed on 18 May 2025). Homologous β-glucosidase family members from Glycine max and Arabidopsis thaliana were identified using BLASTP version 2.17.0 searches with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5 (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins, accessed on 18 May 2025). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW implemented in MEGA X software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model was selected as the amino acid substitution model, and gaps were treated using the pairwise deletion method.

2.10. Gene Cloning and Vector Construction

The complete open reading frame (ORF) of Glyma.12G053800 was amplified from root cDNA of cultivar HN531 using gene-specific primers designed based on the reference genome sequence (Forward: 5′-ATGGCGGCGGTTCTTCTC-3′; Reverse: 5′-TCAAAGAGCAACCACAACAAC-3′). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using the HiScript III 1 st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). PCR amplification was performed using Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme) with the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 90 s; and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The amplified PCR product was gel-purified using a Universal DNA Purification Kit (Tiangen Biotech) and cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1302 containing a CaMV 35S promoter and GFP reporter gene using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). The recombinant plasmid (35S::Glyma.12G053800::GFP) was verified by Sanger sequencing (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and then introduced into Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K599 by electroporation.

2.11. Hairy Root Transformation and Phenotyping

Transgenic composite plants were generated using A. rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation as previously described [46]. Briefly, seeds of the susceptible cultivar DS1 were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol for 30 s, followed by 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min, and rinsed 5 times with sterile distilled water. Seeds were germinated on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium in darkness at 25 °C for 3 days. A. rhizogenes strain K599 harboring the overexpression construct or empty vector control was cultured in YEB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics at 28 °C until OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in liquid 1/2 MS medium to OD600 = 0.5. The hypocotyl of each germinated seedling was wounded using a sterile scalpel, and 10 μL of bacterial suspension was applied to the wound site. Inoculated seedlings were co-cultivated on 1/2 MS medium at 25 °C in darkness for 2 days, then transferred to 1/2 MS medium containing 400 mg L−1 cefotaxime to eliminate Agrobacterium. Plants were cultured under a 16 h/8 h light/dark photoperiod at 25 °C. Approximately 14 days post-transformation, transgenic hairy roots were identified by green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX16) equipped with a GFP filter set (excitation 470/40 nm, emission 525/50 nm). Composite plants with robust GFP-positive hairy roots were selected, and non-transgenic roots were excised. GFP-positive roots were sampled for RNA extraction and gene expression verification by RT-qPCR. For SCN resistance evaluation, composite plants with confirmed transgenic roots were transplanted to pots (10 cm × 14 cm) containing an autoclaved sand-soil mixture (1:1, v/v) and acclimated for 3 days before nematode inoculation. Each plant was inoculated with approximately 200 J2 of SCN race 3. Plants were maintained in a growth chamber under the same conditions described in Section 2.1. Infection rates were determined at 48 h post-inoculation, nematode developmental stages were assessed at 12 dpi, and female counts were recorded at 21 dpi using methods described in Section 2.4, Section 2.5, Section 2.6. Three independent biological replicates were performed with at least 20 composite plants per treatment in each replicate.

2.12. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from soybean roots using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using 1 μg total RNA with the HiScript III 1 st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting cDNA was diluted 6-fold with nuclease-free water before use as qPCR template. Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each 20 μL reaction contained 10 μL SYBR mix, 0.4 μL each primer (10 μM), 2 μL diluted cDNA template, and 7.2 μL nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling program consisted of 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Melting curve analysis was performed from 60 °C to 95 °C with 0.5 °C increments to verify amplicon specificity. Gene-specific primers for RT-qPCR were designed using Primer3 Plus (http://www.primer3plus.com/, accessed on 18 May 2025) with amplicon sizes of 100–200 bp (Forward: 5′-TTGACTCGCAACTCTTTC-3′, Reverse: 5′-TTCCTTGTAGCGGTGATA-3′). The GmACT11 (Glyma.18G290800) served as the internal reference gene for normalization. Three technical replicates were performed for each biological sample. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−∆∆CT method, and fold changes were expressed relative to the control treatment.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with a minimum of three independent biological replicates unless stated otherwise. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For field evaluation, cyst counts came from five replicate plots per cultivar. In controlled environment studies, infection rate assessments included at least 10 plants per treatment across three biological replicates. Nematode development assessments involved examining at least 50 nematodes per root system from at least 10 plants per treatment across three biological replicates. Female cyst counts were obtained from at least 20 plants per treatment across three biological replicates. For hairy root transformation experiments, at least 20 composite plants per treatment were analyzed in each of three biological replicates. All phenotypic data were tested for normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test and for equal variance with Levene’s test before statistical analysis. Nematode count data (including J2 penetration numbers, developmental stages, and female cysts), which often have non-normal distributions, were square-root-transformed [sqrt(x + 0.5)] to satisfy parametric test assumptions. Percentage data (infection rates, proportions at different developmental stages) were arcsine-square-root-transformed when needed to stabilize variance. After verifying normality and homogeneity of variance, two-group comparisons (e.g., HN531 vs. DS1, transgenic vs. control) used a two-tailed Student’s t-test. For comparisons across multiple groups or time points, a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test for post hoc analysis was employed. When data remained non-normal after transformation, non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U for two groups, Kruskal–Wallis for multiple groups) were used. Significance was set at p < 0.05. For figures and tables, means ± SD are shown in their original (back-transformed) form to preserve biological meaning. RT-qPCR analyses involved three technical replicates per biological sample (n = 3). Relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GmACT11 as the reference gene. Differences in gene expression between treatments were tested with Student’s t-test; p < 0.05 indicated significance. Differential expression used DESeq2 v1.30.0 with three biological replicates. Genes with |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.05 were deemed differentially expressed. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses considered p-values < 0.05 corrected for multiple testing as significant. All statistical tests were conducted with SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Graphs were created using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. HN531 Exhibits Post-Penetration Resistance to SCN Through Developmental Arrest at the J2-to-J3 Larval Transition

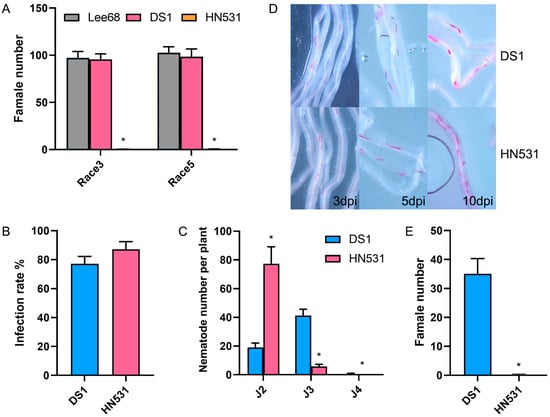

To evaluate the resistance of soybean lines HN531 and DS1 to soybean cyst nematode (SCN), both genotypes were challenged with SCN races 3 and 5. Prior to experimental use, the identity of SCN populations was confirmed through HG-type testing on standard differential host lines, which verified the cultures as HG Type 0 (race 3) and HG Type 2.5.7 (race 5), consistent with the expected race designations and ensuring the reliability of subsequent resistance evaluations. Female cyst counts at 35 dpi revealed that HN531 displayed robust resistance to both races, with virtually no female cysts formed, compared with the susceptible controls Lee 68 and DS1, which showed similar female cyst counts of approximately 100 per plant (Figure 2A). Despite this contrasting resistance phenotype, initial infection rate analysis showed that both HN531 and DS1 roots were similarly susceptible to nematode penetration, with infection rates of approximately 77% and 87%, respectively (Figure 2B), suggesting that HN531’s resistance operates post-penetration. To investigate the mechanism underlying this resistance, fuchsin staining was performed to visualize nematode development at 3, 5, and 10 dpi (Figure 2D). Quantification of larval stages revealed that while DS1 supported normal nematode development with approximately 18 J2, 41 J3, and minimal J4 larvae per plant, HN531 roots contained significantly more J2 larvae (approximately 77 per plant) but dramatically reduced J3 (approximately 6 per plant) and virtually no J4 larvae (Figure 2C), indicating developmental arrest at the J2-to-J3 transition. This arrested development resulted in nearly complete suppression of female cyst formation in HN531, with female numbers approaching zero at 35 dpi compared to approximately 35 females per plant in DS1 (Figure 2E), demonstrating that HN531 effectively prevents SCN from completing its life cycle through a post-penetration resistance mechanism.

Figure 2.

HN531 exhibits post-penetration resistance to SCN through developmental arrest at the J2-to-J3 larval transition. (A) Female cyst numbers on roots of Lee 68, DS1, and HN531 at 35 dpi with SCN races 3 and 5. (B) Infection rates of SCN race 3 in DS1 and HN531 at 48 h post-inoculation. (C) Quantification of nematode developmental stages (J2, J3, J4) in DS1 and HN531 roots at 5 dpi with SCN race 3. (D) Representative microscopy images showing nematode development in DS1 and HN531 roots at 3, 5, and 10 dpi. Nematodes were stained with acid fuchsin (pink/red). Scale bar = 200 μm. (E) Female cyst numbers on DS1 and HN531 roots at 21 dpi with SCN race 3. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates with at least 10 plants (B,C), 20 plants (A,E) per treatment. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to the susceptible control (DS1 or Lee 68) determined by Student’s t-test (* p < 0.05).

3.2. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Extensive Transcriptional Reprogramming in Response to SCN Infection

To investigate the molecular basis of differential SCN resistance between HN531 and DS1, RNA-sequencing was performed on root tissues collected at 5 dpi from both SCN-infected and mock-inoculated (CK) plants. Transcriptome sequencing generated high-quality data across all samples, with clean reads ranging from 37 to 62 million per sample, Q30 scores exceeding 95%, and mapping rates above 95% (Table S1). These quality metrics confirmed the reliability of the transcriptome data for subsequent differential expression analysis. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles revealed distinct transcriptional responses between the resistant and susceptible genotypes (Figure S1). In the DS1 susceptible line, comparison between mock and SCN-infected samples (DS1-CK–5d vs. DS1-SCN–5d) identified 546 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), comprising 351 upregulated and 195 downregulated genes. In striking contrast, the resistant HN531 line exhibited a much more robust transcriptional response to SCN infection, with 1459 DEGs identified between mock and infected samples (HN531-CK–5d vs. HN531-SCN–5d), including 741 upregulated and 718 downregulated genes. This approximately 2.7-fold increase in the number of DEGs in HN531 compared to DS1 suggests that the resistant genotype mounts a more extensive and comprehensive defense response upon nematode challenge. To identify candidate genes associated explicitly with SCN resistance in HN531, we employed a Venn diagram analysis to compare three differential expression datasets: genes responsive to SCN in DS1 (DS1-CK–5d vs. DS1-SCN–5d), genes responsive to SCN in HN531 (HN531-CK–5d vs. HN531-SCN–5d), and genes differentially expressed between the two genotypes under SCN infection (DS1-SCN–5d vs. HN531-SCN–5d) (Figure S2). This analysis revealed 1368 genes uniquely differentially expressed in the direct comparison between infected DS1 and HN531, representing the core set of genes distinguishing the resistant from the susceptible response. Additionally, 12 genes were commonly differentially expressed across all three comparisons, suggesting these represent key regulatory nodes in the resistance response. Notably, 531 genes were uniquely responsive to SCN infection in HN531, while 235 genes were uniquely responsive in DS1, further highlighting the distinct defense strategies employed by the two genotypes. These candidate gene sets provide valuable targets for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying post-penetration resistance to SCN in HN531.

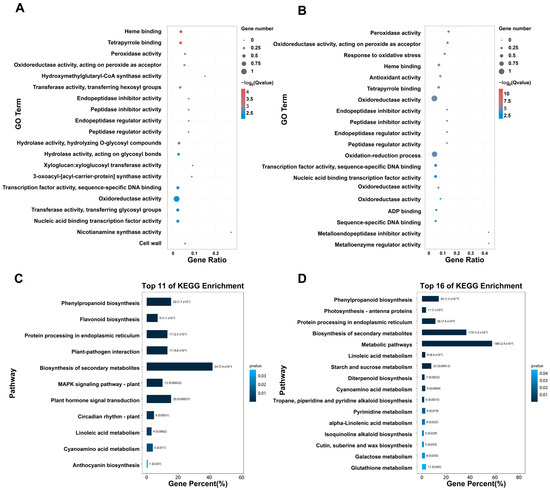

3.3. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Defense-Related Pathways Underlying SCN Resistance in HN531

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the contrasting SCN resistance phenotypes in HN531 and DS1, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified from transcriptomic profiling. GO enrichment analysis revealed significant overrepresentation of defense-related biological processes and molecular functions (Figure 3A,B). The most prominently enriched GO terms in the molecular function category included peroxidase activity and oxidoreductase activity, with particularly high gene counts for oxidoreductase activity acting on peroxide as acceptor and peroxidase activity, suggesting that reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism plays a central role in the resistance response. Additionally, terms related to heme binding, which is essential for peroxidase function, were highly enriched. In the biological process category, response to oxidative stress emerged as a significantly enriched term, consistent with the molecular function results and indicating that oxidative burst is a key component of HN531’s defense strategy. Other notable enriched terms included terpene/terpenoid biosynthesis, peptidase inhibitor activity, endopeptidase regulator activity, and various enzymatic activities related to secondary metabolism, collectively pointing to a multifaceted defense response involving both ROS signaling and the production of antimicrobial secondary metabolites.

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in HN531 and DS1 following SCN infection. (A) GO enrichment analysis of upregulated genes in HN531 after SCN infection. (B) GO enrichment analysis of upregulated genes in DS1 after SCN infection. Bubble size represents the number of genes enriched in each GO term, and color intensity indicates the statistical significance (−log10 of Q-value). Gene Ratio represents the proportion of DEGs annotated to each GO term relative to the total number of genes in that term. Only GO terms with Q-value < 0.05 are shown. (C) Top 11 significantly enriched KEGG pathways for upregulated genes in HN531. (D) Top 16 significantly enriched KEGG pathways for upregulated genes in DS1. Bar length represents the percentage of genes enriched in each pathway (Gene Percent), color intensity indicates p-value, and numbers in parentheses show gene counts. Only pathways with corrected p-value < 0.05 are displayed.

The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis provided further insights into the metabolic and signaling networks activated during the resistance response (Figure 3C,D). The top enriched pathways were dominated by secondary metabolite biosynthesis, with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis showing the highest gene percentage, followed by flavonoid biosynthesis and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum. These pathways are well-established components of plant defense responses and are known to produce antimicrobial compounds and strengthen cell walls. Additional significantly enriched pathways included plant pathogen interaction, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and the MAPK signaling pathway, indicating activation of classical defense signaling cascades. Metabolic reprogramming was also evident, with enrichment of metabolic pathways, starch and sucrose metabolism, and various amino acid biosynthesis pathways including linoleic acid metabolism, diterpenoid biosynthesis, cyanoamino acid metabolism, and pathways for tryptophan, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, alpha-linolenic acid, isoquinoline alkaloid, cutin/suberone/wax, galactose, and glutathione metabolism. This comprehensive metabolic reconfiguration suggests that HN531 redirects cellular resources toward the production of defense compounds and cell wall reinforcement to restrict nematode development.

Among the DEGs identified, Glyma.12G053800 emerged as a particularly promising candidate gene. It consistently exhibited increased expression in response to SCN infection in the resistant HN531 line, while showing a lower induction in the susceptible DS1 line, indicating a resistance-specific pattern. Its annotation as a beta-glucosidase suggests it may activate defense compounds by hydrolyzing glycosidic bonds, which supports the enrichment of phenylpropanoid and secondary metabolite pathways seen in our transcriptome data. Additionally, initial expression profiling revealed that Glyma.12G053800 is mainly expressed in roots, the primary site of nematode invasion, making it an ideal candidate for mediating defense responses. These features—differential expression in resistant and susceptible lines, functional ties to defense pathways, and tissue-specific expression—highlight Glyma.12G053800 as the top candidate for further validation. Bioinformatic analysis categorizes it within the BGLU (beta-glucosidase) gene family.

3.4. Identification of Candidate Resistance Genes Through Comparative Transcriptome Analysis

To systematically identify genes potentially involved in SCN resistance, we focused on DEGs that exhibited different expression patterns between the resistant HN531 and the susceptible DS1 lines after SCN infection. We selected 21 candidate genes based on their expression profiles across the comparisons DS1-CK–5d vs. DS1-SCN–5d and HN531-CK–5d vs. HN531-SCN–5d (Table 1). These genes showed log2 fold changes from 1.01 to 3.39, reflecting significant transcriptional responses to nematode infection in both genotypes, albeit with different magnitudes.

Table 1.

Candidate genes and their expression differences.

Among the candidate genes, several showed notably stronger induction in the resistant line HN531 compared to DS1. For instance, Glyma.19G104100 displayed the highest overall expression changes, with log2 fold changes of 2.44 in DS1 and 3.39 in HN531, representing approximately 40% greater induction in the resistant genotype. Similarly, Glyma.11G129700 showed log2 fold changes of 1.92 in DS1 versus 2.96 in HN531, and Glyma.12G054100 exhibited a striking difference with a log2 fold change of only 1.05 in DS1 but 2.71 in HN531, indicating more than 2.5-fold stronger induction in the resistant line. Other genes including Glyma.01G210400, Glyma.11G129500, and Glyma.14G053600 also showed substantially higher induction in HN531, with increases of 1.43, 1.29, and 0.79 log2 units, respectively, compared to DS1.

Conversely, some candidate genes exhibited higher induction in the susceptible DS1 line. Notably, Glyma.08G109400 and Glyma.08G110801 showed log2 fold changes of 1.58 and 1.62 in DS1, respectively, but only 1.01 and 1.03 in HN531, suggesting these genes may be more strongly activated in susceptible responses. Similarly, Glyma.09G281800 and Glyma.17G049900 displayed stronger induction in DS1 with log2 fold changes of 1.60 and 1.82 compared to 1.24 and 1.28 in HN531, respectively.

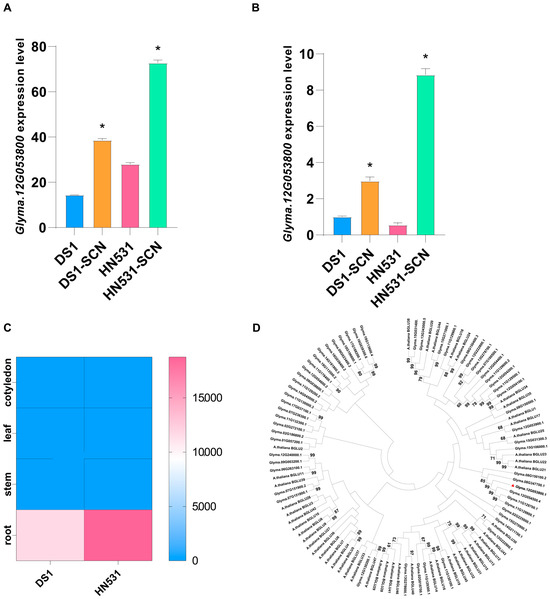

Interestingly, the previously identified candidate gene Glyma.12G053800 showed relatively similar log2 fold changes between both genotypes (1.42 in DS1 vs. 1.38 in HN531), suggesting that while this gene is responsive to SCN infection in both lines, the magnitude of transcriptional induction alone may not fully explain its role in resistance. However, the qRT-PCR validation (Figure 4B,C) revealed much more dramatic differences in absolute expression levels, indicating that Glyma.12G053800 likely functions through higher basal expression or sustained upregulation in HN531 rather than differential fold-change responses. The identification of these 21 candidate genes provides a valuable foundation for further functional characterization of the molecular mechanisms underlying SCN resistance in soybean.

Figure 4.

Expression analysis and phylogenetic characterization of Glyma.12G053800. (A,B) Quantitative RT-PCR validation of Glyma.12G053800 expression in resistant line HN531 and susceptible line DS1 under mock-inoculated (CK) and SCN-infected (SCN) conditions at [specify time points, e.g., 3 dpi and 5 dpi]. Relative expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene GmACT11 using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates, each with three technical replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between treatments (Student’s t-test, * p < 0.05). (C) Tissue-specific expression heatmap of Glyma.12G053800 across different soybean organs (root and shoot tissues). Expression values are shown as normalized FPKM values from publicly available transcriptome data. The color scale indicates relative expression levels from low (blue) to high (pink/red). (D) Phylogenetic tree of β-glucosidase (BGLU) family members from Glycine max and Arabidopsis thaliana. The tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA X. Glyma.12G053800 is highlighted with a red box or arrow and clusters with AtBGLU15 and related soybean homologs. Bootstrap values ≥ 50% are shown at branch nodes. The scale bar represents amino acid substitutions per site.

3.5. Glyma.12G053800 Shows Resistance-Specific Expression and Root Tissue Specificity

A comprehensive analysis of the evolution and expression of the resistance gene Glyma.12G053800 was conducted. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on root samples from resistant (HN531) and susceptible (DS1) lines under mock-inoculated (CK) and SCN-infected conditions to validate the transcriptome data and examine Glyma.12G053800’s response to SCN infection. The results confirmed the RNA-seq data and showed distinct genotype-specific expression patterns (Figure 4A,B). Under control conditions, Glyma.12G053800 was expressed at low, similar levels in both genotypes, with a slightly higher baseline in DS1. Post-SCN infection, Glyma.12G053800 was significantly upregulated in resistant HN531, with roughly 5- and 9-fold increases at different time points compared to its mock-inoculated control, reaching about 70 and 9 relative units, respectively. The susceptible DS1 showed a modest increase to approximately 15 and 3 units, with one instance where its expression under SCN was lower than HN531’s control level. This pronounced, resistance-specific induction suggests Glyma.12G053800 likely plays a crucial role in HN531’s defense against SCN. To identify its expression sites, we examined tissue-specific expression across various soybean organs. The heatmap showed Glyma.12G053800 mainly expressed in roots, at much higher levels than in shoots or aerial parts (Figure 4D). This root-specific expression aligns with the fact that roots are the primary site of SCN infection and plant-nematode interactions, supporting the hypothesis that Glyma.12G053800 acts as a defense gene activated in roots to counter nematode invasion and development. Phylogenetic analysis of the BGLU gene family in Arabidopsis and soybean revealed that Glyma.12G053800 clusters closely with Arabidopsis BGLU15 and several other soybean BGLU genes, forming a unique evolutionary group (Figure 4C). This points to potential functional similarity between Glyma.12G053800 and AtBGLU15 in defense mechanisms.

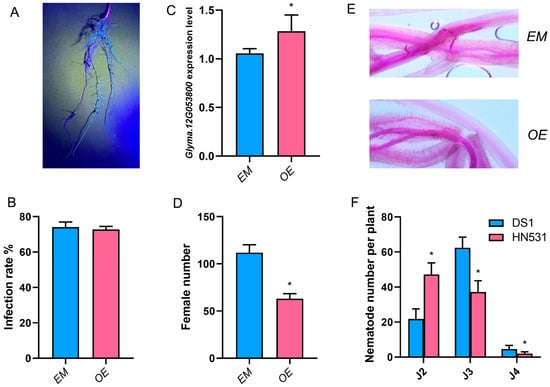

3.6. Overexpression of Glyma.12G053800 Enhances SCN Resistance in Susceptible Soybean

Transgenic hairy root composite plants overexpressing this gene in the susceptible DS1 background were created to validate Glyma.2G053800’s role in SCN resistance. Successful transformation was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy, showing strong blue fluorescent signals in the transgenic hairy roots, indicating high expression of the fluorescent marker. (Figure 5A). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis verified that Glyma.12G053800 transcript levels in overexpressing (OE) lines were significantly reduced compared to empty vector (EM) controls, with OE lines showing approximately 75% of the expression level observed in EM controls (Figure 5B), confirming the establishment of transgenic lines with altered gene expression. To assess whether Glyma.12G053800 overexpression affects SCN resistance, we first examined nematode infection rates in transgenic roots. The results showed no significant difference in infection rates between EM and OE lines, with both displaying approximately 73–75% infection rates (Figure 5C). This indicates that, similar to the resistant HN531 genotype, Glyma.12G053800 overexpression does not prevent initial nematode penetration, suggesting its role in post-penetration resistance mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Functional validation of Glyma.12G053800 in soybean cyst nematode resistance through hairy root transformation. (A) Fluorescence microscopy image of transgenic hairy roots expressing a blue fluorescent protein marker, confirming successful Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation. (B) Infection rates of SCN in empty vector control (EM) and Glyma.12G053800 overexpression (OE) transgenic roots at 48 h post-inoculation, showing no significant difference in initial nematode penetration. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR validation of Glyma.12G053800 expression levels in EM and OE transgenic lines, demonstrating successful overexpression. (D) Female cyst numbers at 35 days post-inoculation (dpi) in EM and OE lines, showing a significant reduction (~40%) in female development in OE lines. (E) Fuchsin-stained root sections showing nematode development at 12 dpi in EM (upper panel) and OE (lower panel) transgenic roots. (F) Quantification of nematode developmental stages (J2, J3, J4) at 12 dpi in susceptible DS1 and resistant HN531 backgrounds, comparing EM and OE lines. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates (n ≥ 20 composite plants per treatment). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test for panels (B–D); one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test for panel (F)). EM, empty vector control; OE, Glyma.12G053800 overexpression line; J2, J3, J4, second-, third-, and fourth-stage juveniles.

Despite similar infection rates, overexpression of Glyma.12G053800 resulted in significant reduction in female cyst formation. The number of female nematodes at 35 dpi was reduced by approximately 40% in OE lines (approximately 65 females per plant) compared to EM controls (approximately 110 females per plant) (Figure 5D), demonstrating that elevated expression of Glyma.12G053800 confers partial resistance to SCN even in the susceptible DS1 background.

To investigate the mechanism underlying this resistance enhancement, we performed fuchsin staining to visualize nematode development within transgenic roots at different time points (Figure 5E). Compared with the resistant HN531 and susceptible DS1 parental lines, distinct developmental patterns emerged (Figure 5F). At the J2 larval stage, EM control lines showed approximately 22 nematodes per plant, similar to the susceptible DS1 phenotype. In comparison, OE lines contained approximately 47 nematodes per plant, approaching the level observed in resistant HN531 (approximately 48 nematodes per plant based on previous data). At the J3 stage, OE lines maintained approximately 38 nematodes per plant, compared to approximately 62 in EM controls, and showed intermediate values between the resistant HN531 and susceptible DS1 patterns. Most strikingly, at the J4 stage, OE lines exhibited a dramatic reduction in nematode numbers with only approximately 3 nematodes per plant compared to approximately 5 in EM controls and nearly absent in HN531, indicating developmental arrest. These results demonstrate that overexpression of Glyma.12G053800 partially recapitulates the resistant HN531 phenotype by impeding nematode progression through larval stages, particularly affecting the transition from J3 to J4, ultimately resulting in reduced female cyst formation. Collectively, these functional analyses establish Glyma.12G053800 as a key contributor to post-penetration resistance against SCN in soybean.

4. Discussion

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) remains one of the most economically damaging pathogens affecting soybean production worldwide, resulting in annual yield losses of over $1.5 billion in the United States alone [5]. The development of SCN-resistant soybean cultivars represents the most effective and environmentally sustainable strategy for managing this persistent threat [5,7]. The molecular mechanisms behind SCN resistance, especially post-penetration resistance, are not fully understood. In this research, we examined the resistance mechanisms in the resistant soybean line HN531. Our comprehensive phenotypic, transcriptomic, and functional analyses revealed Glyma.12G053800, a beta-glucosidase gene, as a significant factor in post-penetration resistance.

4.1. HN531 Exhibits Post-Penetration Resistance Through Developmental Arrest

Our resistance screening showed that HN531 has strong resistance to both SCN races 3 and 5, with nearly complete suppression of female cyst formation. In contrast, the susceptible line DS1 supported normal nematode development, similar to the standard susceptible control, Lee68. Interestingly, despite this significant difference in resistance, both genotypes exhibited similar infection rates of about 77-87%, suggesting HN531’s resistance operates after nematode penetration rather than preventing initial invasion. This aligns with previous studies indicating post-penetration resistance in soybean, where nematodes can penetrate roots but cannot establish feeding sites or complete their life cycle [47,48]. The temporal analysis of nematode development using fuchsin staining revealed that resistance in HN531 is primarily mediated by developmental arrest at the J2-to-J3 larval transition. While susceptible DS1 roots supported progressive nematode development through the J2, J3, and J4 stages, HN531 roots accumulated significantly higher numbers of J2 larvae but dramatically reduced J3 and were virtually absent of J4 larvae. This developmental arrest pattern is reminiscent of resistance mechanisms reported in other SCN-resistant soybean lines carrying different resistance loci [4,49]. For instance, resistance mediated by the rhg1 locus has been associated with syncytium degeneration and arrested nematode development [50], while Rhg4-mediated resistance involves both pre- and post-penetration mechanisms [51]. The specific arrest at the J2-to-J3 transition observed in HN531 suggests that this genotype may employ unique molecular mechanisms or possess novel combinations of resistance genes that disrupt critical developmental processes required for nematode maturation.

4.2. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Complex Defense Networks Underlying Resistance

Comparison of transcriptomes between HN531 and DS1 after SCN infection showed extensive transcriptional changes, with HN531 displaying about 2.7 times more differentially expressed genes than DS1 (1459 vs. 546 DEGs). This much stronger transcriptional response in the resistant genotype indicates that effective SCN resistance relies on the coordinated activation of multiple defense pathways rather than localized or limited responses. Similar findings have been observed in other plant-nematode systems, where resistant genotypes produce more robust and complex transcriptional responses compared to susceptible ones [40,52]. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis highlighted the significance of oxidative stress-related processes, with peroxidase activity, oxidoreductase activity, and response to oxidative stress among the most significantly enriched terms. This supports the well-known role of ROS in plant defense mechanisms against various pathogens, including nematodes [42]. The ROS can function both as direct antimicrobial agents and as signaling molecules that trigger downstream defense responses, including hypersensitive response, cell wall reinforcement, and activation of defense gene expression [53]. Previous studies have demonstrated that SCN-resistant soybean lines exhibit elevated ROS accumulation at nematode feeding sites, which contributes to syncytium necrosis and nematode starvation [11,54]. The high abundance of peroxidase-related genes in our dataset indicates that HN531 relies on oxidative burst as a crucial part of its resistance mechanism. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis also showed that pathways for secondary metabolite biosynthesis, especially phenylpropanoid and flavonoid synthesis, were notably upregulated in HN531 during SCN infection. These compounds, phenylpropanoids and flavonoids, are vital plant defense chemicals with various antimicrobial and signaling roles [55,56]. These compounds can directly inhibit nematode development, reinforce cell walls through lignin deposition, and modulate plant hormone signaling pathways that regulate defense responses [57,58]. The enrichment of these pathways is consistent with reports showing that resistant soybean lines accumulate higher levels of phenolic compounds and exhibit increased lignification at nematode feeding sites compared to susceptible lines [59,60]. Additionally, the activation of MAPK signaling pathways and plant-pathogen interaction pathways indicates that classical defense signaling cascades are engaged during the resistance response, coordinating the expression of downstream defense genes [61].

4.3. Glyma.12G053800 Functions as a Key Resistance Gene Through Beta-Glucosidase Activity

Glyma.12G053800 emerged as a notable candidate resistance gene from our transcriptome analysis, supported by its expression profile, phylogenetic ties, and functional tests. Bioinformatics placed Glyma.12G053800 within the BGLU (beta-glucosidase) gene family, and phylogenetic studies revealed its close relationship to Arabidopsis BGLU15. Beta-glucosidases are enzymes that break down glycosidic bonds in substrates such as defense compounds, cell wall materials, and phytohormone conjugates [62]. In plants, these enzymes activate defense compounds stored as inactive glycosides, releasing bioactive aglycones that have antimicrobial or toxic effects [63]. Expression profiling of Glyma.12G053800 identified key features supporting its involvement in SCN resistance. It was significantly upregulated in the resistant HN531 line during SCN infection—about 5 to 9 times more than controls—while the susceptible DS1 showed only minor induction. Furthermore, Glyma.12G053800 was primarily expressed in roots, which are the main site of SCN infection and plant-nematode interaction. Notably, overexpressing Glyma.12G053800 in the susceptible DS1 background enhanced resistance, decreasing female cyst numbers by approximately 40% and partially replicating the developmental arrest observed in HN531. The resistance mechanism likely involves activating defense compounds by hydrolyzing their glycosylated precursors, as many plants store antimicrobial compounds as inactive glycosides that become active upon pathogen attack via beta-glucosidases [51,62]. Overexpressing Glyma.12G053800 affected nematode development after penetration, especially the transition from J2 to J3, indicating its activity is essential during feeding site formation, when nematodes depend on nutrient uptake from the syncytium. [8,28]. Its close phylogenetic link to Arabidopsis BGLU15 offers clues to its role. Although AtBGLU15’s role in nematode resistance is not clear, other Arabidopsis beta-glucosidases are tied to stress responses and defense [64]. The conservation of these genes suggests beta-glucosidase-based defense is an evolutionarily conserved strategy against pathogens and pests [62,65].

4.4. Integration of Multiple Defense Mechanisms in SCN Resistance

Although our study centered on characterizing Glyma.12G053800, it is essential to acknowledge that SCN resistance in HN531 probably results from the combined action of multiple genes and pathways. The discovery of 21 candidate genes with different expression patterns between resistant and susceptible lines, along with the significant enrichment of various defense-related pathways, indicates a complex resistance mechanism. In fact, most known SCN resistance in soybean is quantitative, involving multiple QTLs with different effect sizes [5,54]. The major resistance loci rhg1 and Rhg4 often work synergistically to confer strong resistance, and additional minor QTLs can further enhance resistance levels [15,41]. The transcriptome data revealed that genes involved in ROS metabolism, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, cell wall modification, protease inhibitors, and defense signaling were all notably enriched in HN531. This layered defense approach could be essential for effectively countering SCN, which has developed advanced strategies to weaken plant defenses and manipulate host cell functions for its advantage [26,27,28]. Nematodes secrete a diverse array of effector proteins that can suppress ROS production, modulate hormone signaling, and manipulate plant gene expression [42]. Therefore, effective resistance may require simultaneous activation of multiple independent or partially redundant defense mechanisms to overcome nematode counter-defenses.

4.5. Implications for SCN Resistance Breeding

Recognizing Glyma.12G053800 as a key factor in SCN resistance has essential implications for soybean breeding. It could introduce a new resistance source to combine with genes like rhg1 and Rhg4, resulting in more durable, broad-spectrum defense. Relying on a single resistance gene has often led to virulent SCN populations overcoming it; thus, stacking multiple resistance genes with different modes of action could delay resistance breakdown and promote long-lasting protection. Glyma.12G053800 might also serve as a marker for selecting resistant plants, since different alleles may differ in effectiveness. Additionally, the beta-glucosidase-based resistance mechanism could be helpful in other legumes, such as Meloidogyne spp., by identifying orthologous genes for nematode control. Although substantial evidence supports its role, further research is needed to clarify the enzyme’s substrates, its regulation during infection, its interactions with other resistance genes, and whether co-expression of additional genes could improve resistance beyond the current 40% reduction. Conducting biochemical, genetic, and breeding studies on these points could lead to the development of more effective nematode-resistant soybean varieties.

4.6. Potential Interactions of Glyma.12G053800 with Phenylpropanoid Pathway Components

The identification of Glyma.12G053800, a β-glucosidase involved in SCN resistance, raises essential questions about its interactions with other components of the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, one of the most enriched pathways in our transcriptome analysis. β-glucosidases typically function downstream in secondary metabolite pathways by hydrolyzing glycosidic bonds in substrates, thereby activating defense compounds stored as inactive glycosides [66,67]. In phenylpropanoid metabolism, several interaction points are possible. First, Glyma.12G053800 might target phenylpropanoid glycosides, such as flavonoid glucosides, isoflavone conjugates, or hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, which accumulate during nematode infection. KEGG pathway analysis revealed significant enrichment of genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, indicating that HN 531 produces higher flavonoid levels during SCN infection. The concurrent upregulation of Glyma.12G053800 and flavonoid biosynthetic genes supports a model where flavonoid aglycones are stored as glucosides and rapidly activated upon nematode attack via β-glucosidase activity. Second, Glyma.12G053800 may interact with enzymes responsible for producing its glycoside substrates, such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), chalcone synthase (CHS), and various glycosyltransferases, which showed differential expression in our RNA-seq data. The coordinated timing of glycosylated phenylpropanoid synthesis and β-glucosidase-mediated hydrolysis suggests a two-stage defense mechanism that allows plants to swiftly deploy bioactive compounds while minimizing autotoxicity during normal growth [68]. Third, Glyma.12G053800 activity might generate products that act as antimicrobial agents or signaling molecules, boosting defense responses. Phenylpropanoid aglycones released by β-glucosidase activity could enhance lignin deposition in cell walls around nematode feeding sites, physically limiting syncytium expansion and nutrient flow to the nematode [69]. These compounds may also promote the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activate MAPK signaling pathways, both of which were enriched in our analysis, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies multiple defense mechanisms. Future studies should utilize targeted metabolomics to identify Glyma.12G053800 substrates during SCN infection. Co-expression network analysis of our RNA-seq data could uncover correlated regulation with other genes in the phenylpropanoid pathway. Moreover, experiments using double mutants or overexpression of Glyma.12G053800, combined with key enzymes such as PAL or CHS, could provide definitive evidence of epistatic interactions and functional synergy. These investigations would clarify the resistance mechanism and support the development of strategies to stack resistance genes and enhance durable SCN resistance in crops.

5. Conclusions

Soybean cyst nematode continues to pose a significant threat to global soybean yields, emphasizing the need for resistant varieties with lasting, innovative defenses. In this study, we thoroughly investigated SCN resistance in the soybean line HN531, exploring its molecular foundation through combined phenotypic, transcriptomic, and functional genomic analyses. Results indicate that HN531 mainly resists SCN after penetration by stopping nematode development from J2 to J3 larva, rather than avoiding initial entry. This resistance is associated with widespread transcriptional changes related to oxidative stress, secondary metabolites, and defense signaling. Comparative transcriptomics identified 21 genes differentially expressed between resistant HN531 and susceptible DS1 after infection. Among them, Glyma.12G053800, encoding a beta-glucosidase similar to AtBGLU15, emerged as a key resistance gene. Overexpression in susceptible soybean roots confirmed its essential role, reducing female cysts by about 40%, identical to HN531’s developmental arrest. The gene showed resistance-specific upregulation and root-preferential expression, suggesting its role in activating defenses at feeding sites. Our research enhances understanding of post-penetration resistance to SCN and highlights beta-glucosidase-mediated defense as a new aspect of soybean immunity. The identified resistance mechanism and Glyma.12G053800 provide valuable resources for breeding durable SCN-resistant soybean varieties.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15112630/s1, Figure S1: The number of DEGs. Blue represent up regulated, and pink represent downregulated; Figure S2: Identify candidate genes through the application of Venn diagrams; Table S1: Quality control of transcriptome; Table S2: All gene information.

Author Contributions

J.Y.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. R.Z.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. Y.Y.: Investigation, Visualization. S.F.L.: Visualization, Writing—original draft. Y.H.: Formal analysis, Investigation. J.L.: Formal analysis, Investigation. H.L.: Investigation, Validation. J.W.: Funding acquisition, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Key Research and Development Program Project of Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (2022ZX02B06) and Nematode Control Post of National Soybean Industry Technology System (CARS-04-PS27).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singh, K.; Gupta, S.; Shivakumar, M.; Nataraj, V. Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] Breeding. In Fundamentals of Legume Breeding: A Text for Students and Practitioners; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.J.; Ali, M.L.; Beavis, W.D.; Chen, P.; Clemente, T.E.; Diers, B.W.; Graef, G.L.; Grassini, P.; Hyten, D.L.; McHale, L.K. Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] breeding: History, improvement, production and future opportunities. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Legumes: Volume 7; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 431–516. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, L.F.; Gage, K.L.; Pimentel, M.F.; Bond, J.P.; Fakhoury, A.M. Weeds hosting the soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines Ichinohe): Management implications in agroecological systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchum, M.G. Soybean resistance to the soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines: An update. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendimu, G.Y. Cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) problems in soybean (Glycine max L.) crops and its management. Adv. Agric. 2022, 2022, 7816951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Jiang, R.; Peng, H.; Liu, S. Soybean cyst nematodes: A destructive threat to soybean production in China. Phytopathol. Res. 2021, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissan, N.; Mimee, B.; Cober, E.R.; Golshani, A.; Smith, M.; Samanfar, B. A broad review of soybean research on the ongoing race to overcome soybean cyst nematode. Biology 2022, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, P. Soybean Cyst Nematode (Heterodera glycines Ichinohe) Virulence Assay Against Resistance Sources in Nebraska. Master Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA, December 2024. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/plantpathdiss/4/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Lee, D.L. Chapter 3. Life Cycles. In Biology of Nematodes; Taylor and Fransis: Abingdon, UK, 2002; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.L.; Tylka, G.L. Symptoms and Signs. Phytopathol. News 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, A.F. Exploring soybean resistance to soybean cyst nematode. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2022, 60, 379–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, M.I. Natural Genetic Diversity of the Nematode Meloidogyne hapla in Nematode-Plant Interaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal, P. Identification of Host Resistance in Dry Beans and Associated Genomic Regions Conferring Resistance Against Virulent Soybean Cyst Nematode Populations in North Dakota. Ph.D. Thesis, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kumawat, G.; Raghuvanshi, R.; Vennampally, N.; Maranna, S.; Rajesh, V.; Chandra, S.; Kumar, S.; Rajput, L.S.; Meena, L.K.; Choyal, P. Integrating germplasm diversity and omics science to enhance biotic stress resistance in soybean. In Genomics-Aided Breeding Strategies for Biotic Stress in Grain Legumes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 327–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerning, C.A. Evaluation of Soybean Cyst Nematode Development on the Winter Oilseeds Pennycress and Camelina. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, R.N.; Moens, M.; Jones, J.T. Cyst Nematodes; CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J.G.; Mundo-Ocampo, M. Heteroderinae, cyst-and non-cyst-forming nematodes. In Manual of Agricultural Nematology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991; pp. 275–362. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, S. Developmental Biology of Heterodera glycines (Soybean Cyst Nematode) and Other Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandra, N. Integrated Nematode Management in Crops. In Plant Disease Management; International Book Distributors: Dehradun, India, 2012; p. 647. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Ahamad, I.; Shah, M.H. Emerging important nematode problems in field crops and their management. In Emerging Trends in Plant Pathology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M. Integrated Nematode Management Strategies: Optimization of Combined Nematicidal and Multi-Functional Inputs. Plants 2025, 14, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M. Revolutionizing nematode management–nanomaterials as a promising approach for managing economically important plant-parasitic nematodes: Current knowledge and future challenges. In Nanotechnology and Plant Disease Management; Taylor and Fransis: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kenfaoui, J.; Goura, K.; Legrifi, I.; Seddiqi Khalil, N.; El Hamss, H.; Mokrini, F.; Amiri, S.; Belabess, Z.; Lahlali, R. Natural product repertoire for suppressing the immune response of Meloidogyne species. In Root-Galling Disease of Vegetable Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 163–197. [Google Scholar]

- Matthiessen, J.N.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Biofumigation and enhanced biodegradation: Opportunity and challenge in soilborne pest and disease management. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.B.; Lakhssassi, N.; Wan, J.; Song, L.; Zhou, Z.; Klepadlo, M.; Vuong, T.D.; Stec, A.O.; Kahil, S.S.; Colantonio, V. Whole-genome re-sequencing reveals the impact of the interaction of copy number variants of the rhg1 and Rhg4 genes on broad-based resistance to soybean cyst nematode. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Ghani, N.N.U.; Chen, L.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, J.; Han, S. Research progress on the functional study of host resistance-related genes against Heterodera glycines. Crop Health 2023, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, A.S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, J.; Feng, Y.; Huai, Y.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Azam, M.; Htway, H.T.P. The GmSNAP11 contributes to resistance to soybean cyst nematode race 4 in Glycine max. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 939763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Qin, R.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, J.; Chang, D.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Q.; Guo, X. Response of soybean genotypes from Northeast China to Heterodera glycines races 4 and 5, and characterisation of rhg1 and Rhg4 genes for soybean resistance. Nematology 2021, 24, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.J. Investigating Soybean Cyst Nematode Resistance: Efficacy of Rhg1 in Diverse Plant Species and the Identification of Novel Resistance Mechanisms from Wild Soybean. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bayless, A.M.; Zapotocny, R.W.; Han, S.; Grunwald, D.J.; Amundson, K.K.; Bent, A.F. The rhg1-a (Rhg1 low-copy) nematode resistance source harbors a copia-family retrotransposon within the Rhg1-encoded α-SNAP gene. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapotocny, R.W. Understanding the Mechanism and Epigenetic Regulation of Rhg1, a Major Soybean Cyst Nematode Resistance Locus. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, N.; Lee, T.G.; Rosa, D.P.; Hudson, M.; Diers, B.W. Impact of Rhg1 copy number, type, and interaction with Rhg4 on resistance to Heterodera glycines in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, Y.; Sheets, J.J.; Tan, S.Y.; Narva, K.E.; Escriche, B. Toxicity and binding studies of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac, Cry1F, Cry1C, and Cry2A proteins in the soybean pests Anticarsia gemmatalis and Chrysodeixis (Pseudoplusia) includens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00326-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengyella, L.; Yekwa, E.L.; Iftikhar, S.; Nawaz, K.; Jose, R.C.; Fonmboh, D.J.; Tambo, E.; Roy, P. Global challenges faced by engineered Bacillus thuringiensis Cry genes in soybean (Glycine max L.) in the twenty-first century. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, T.W.; Duck, N.B.; McCarville, M.T.; Schouten, L.C.; Schweri, K.; Zaitseva, J.; Daum, J. A Bacillus thuringiensis Cry protein controls soybean cyst nematode in transgenic soybean plants. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höss, S.; Menzel, R.; Gessler, F.; Nguyen, H.T.; Jehle, J.A.; Traunspurger, W. Effects of insecticidal crystal proteins (Cry proteins) produced by genetically modified maize (Bt maize) on the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, Y.; Galeano, M.; Baños-Salmeron, M.; Andrés-Antón, M.; Escriche, B. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5, Cry21, App6 and Xpp55 proteins to control Meloidogyne javanica and M. incognita. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramjeet; Jain, D.; Nama, C.P.; Mohanty, S.R. Evaluation of native Bacillus thuringiensis strains possessing nematicidal specific cry genes against Meloidogyne incognita. Folia Microbiol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Tang, Z.; Muhammad, S.; Zheng, J.; Wan, D.; Peng, D.; Ruan, L.; Sun, M. Dissimilar crystal proteins Cry5Ca1 and Cry5Da1 synergistically act against Meloidogyne incognita and delay Cry5Ba-based nematode resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e03505-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Chen, S.; Fatima, S.; Ahamad, L.; Siddiqui, M.A. Biotechnological tools to elucidate the mechanism of plant and nematode interactions. Plants 2023, 12, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Diers, B.W. Fine mapping of the SCN resistance QTL cqSCN-006 and cqSCN-007 from Glycine soja PI 468916. Crop Sci. 2013, 53, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, K.; Gogoi, H.; Borgohain, M.; Saikia, R.; Chikkaputtaiah, C.; Hiremath, S.; Basu, U. The molecular dynamics between reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and phytohormones in plant’s response to biotic stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, C.; Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Mao, Y.; You, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Tian, Z.; Wang, C. Identification of HG types of soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines and resistance screening on soybean genotypes in Northeast China. J. Nematol. 2018, 50, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-l.; Zhang, X.-h.; Zhong, L.-j.; Wang, X.-y.; Jin, L.-s.; Lyu, S.-h. One-step generation of composite soybean plants with transgenic roots by Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, N.; Inserra, R.N. Detection of resistance, susceptibility, tolerance, and virulence in plant–nematode interactions: Part I—Sedentary endoparasitic nematodes. In Plant-Nematode Interactions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 103–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, H.; Roberts, P.A.; Lopez-Arredondo, D. Combating Root-Knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.): From molecular mechanisms to resistant crops. Plants 2025, 14, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Baidoo, R. Current research status of Heterodera glycines resistance and its implication on soybean breeding. Engineering 2018, 4, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, D.; Srour, A.; Afzal, J.; Saini, N. The Multigeneic Rhg1 Locus: A Model For The Effects on Root Development, Nematode Resistance and Recombination Suppression. Nat. Preced. 2008, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.M.; Masonbrink, R.E.; Maier, T.R.; Gardner, M.N.; Severin, A.J.; Baum, T.J.; Mitchum, M.G. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of soybean cyst nematode inbred populations non-adapted or adapted on soybean rhg1-a/Rhg4-mediated resistance. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 2341–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M. Understanding molecular plant–nematode interactions to develop alternative approaches for nematode control. Plants 2022, 11, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]