Abstract

The classical Voorn-Overbeek thermodynamic theory of complexation and phase separation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes is generalized to account for the charge accessibility and hydrophobicity of polyions, size of salt ions, and pH variations. Theoretical predictions of the effects of pH and salt concentration are compared with published experimental data and experiments we performed, on systems containing poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) as the polyacid and poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) (PDMAEMA) or poly(diallyldimethyl ammonium chloride) (PDADMAC) as the polybase. In general, the critical salt concentration below which the mixture phase separates, increases with degree of ionization and with the hydrophobicity of polyelectrolytes. We find experimentally that as the pH is decreased below 7, and PAA monomers are neutralized, the critical salt concentration increases, while the reverse occurs when pH is raised above 7. We predict this asymmetry theoretically by introducing a large positive Flory parameter (= 0.75) for the interaction of neutral PAA monomers with water. This large positive Flory parameter is supported by molecular dynamics simulations, which show much weaker hydrogen bonding between neutral PAA and water than between charged PAA and water, while neutral and charged PDMAEMA show similar numbers of hydrogen bonds. This increased hydrophobicity of neutral PAA at reduced pH increases the tendency towards phase separation despite the reduction in charge interactions between the polyelectrolytes. Water content and volume of coacervate are found to be a strong function of the pH and salt concentration.

1. Introduction

When aqueous solutions of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes are mixed together, they often phase separate into distinct coacervate/precipitate and supernatant phases, rich and dilute in polymer, respectively [1]. Unlike the segregative phase separation often encountered in aqueous polymeric mixtures when the two polymers end up in (predominantly) different phases, the phase separation in aqueous mixtures of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes are found to be associative, meaning the two polyelectrolytes prefer to stay in the same phase. The resulting “dense phase” is referred as a coacervate or a precipitate, depending on its visual appearance and water content [2,3,4]. Coacervates have high water content and are reminiscent of a viscous liquid. Precipitates, on the other hand, are solid-like structures with less water content and are reminiscent of a polymer glass. Between the two extremes, cloudy phases with varying turbidities are sometimes observed [3]. Polyelectrolyte complexation is a general term used to describe phase separation in solutions of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes, where the resulting dense phase can be a coacervate/precipitate or a cloudy phase. Note that the precipitate and cloudy phases could be non-equilibrium structures, in contrast to coacervates, which are presumed to form through equilibrium phase separation. Scientific interest in polyelectrolyte complexation dates back to the pioneering experiments by the Dutch chemist, Bungenberg de Jong, in early twentieth century [5]. Since the complexity of coacervates showed a close resemblance with that of biological constructs in the protoplasm, Soviet biochemist Alexander Oparin asserted that these coacervates could have been precursors to the origin of life [6]. Oparin’s hypothesis has however been dismissed in modern theories of the origin of life, particularly after the discovery of DNA as the genetic material [7]. Most of the earlier studies on polyelectrolyte complexation focused on coacervation of natural polymers such as albumin and gelatin, but recent studies [2,3,8,9,10,11,12] have extended this to the complexation of synthetic polyelectrolytes. Renewed scientific interest in polyelectrolyte complexation is due, in part, to its use in polyelectrolyte assemblies and multilayer films [13,14], which have many technological applications [15,16].

The thermodynamic description of polyelectrolyte coacervation was first developed by Overbeek and Voorn [17] using a mean-field approach, henceforth referred as VO (Voorn-Overbeek) theory. They argued that the tendency toward phase separation is governed by the competition of entropic forces that favor a single-phase solution (no phase separation) and electrostatic correlations that favor phase separation accompanied by the formation of a dense phase containing polyelectrolyte complexes. The entropic forces were described using the Flory-Huggins theory of polymer solutions and the electrostatic correlations were described using the Debye-Hückel (DH) theory. Veis and Aranyi [18,19] suggested an alternate mechanism of coacervation as a two-step process, in which the electrostatic interactions between the polyions first drive the formation of neutral aggregates, followed by their coalescence into a coacervate phase due to hydrophobic interactions. Burgess [20] has reviewed the performance of these two theories and their subsequent modifications [21,22] for a range of systems containing gelatin, albumin, and acacia.

The main criticisms of the VO theory concern one or more of its four simplifying assumptions: (1) a macrophase separation results in distinct supernatant and coacervate phases, (2) charge connectivity of polyions is not considered and polyion charges and salt ions are uniformly distributed in the coacervate and supernatant phase, (3) pH and salt concentration are such that the DH approximation is valid, (4) polyion charges are constant and charge regulation effects due to the presence of other polyion molecules and salt ions are negligible. Recent theories have focused on more detailed treatment of electrostatics, including the effects of ion size and charge connectivity on the polyion [23,24], ion-pair formation and solute-solvent interactions [25], and charge regulation [26,27,28]. Moreover, the possibility of microstructure formation has also been explored [29]. Field-theoretical simulations [30], Langevin dynamics simulations [31,32], and atomistic molecular dynamics simulations [33], have also been used to study polyelectrolyte complexation. Despite these recent advances, VO theory continues to be used to explain experimental data because of its inherent simplicity and applicability for a wide range of systems. Recently, for example, Spruijt et al. [10] adapted the VO theory to describe complexation behavior of charge-stoichiometric compositions of synthetic polyelectrolytes, poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) and poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) (PDMAEMA), and obtained good agreement with experiments. Priftis et al. [34] have also used a modified version of the VO theory to explain complexation behavior in ternary systems composed of a polycation with two polyanions: (1) PAA with PDMAEMA and poly(allylamine) (PAH), and (2) PAA with PDMAEMA and poly(ethylenimine) (PEI).

In this paper, we study the complexation behavior of synthetic polyelectrolytes using a generalized version of the VO theory described in the next section. In particular, we focus on the effects of pH variations that result in changes in the degree of dissociation of polyions. We test the performance of the theory with experimental data borrowed from published literature [1,10,35] and our own experiments on systems containing PAA as the polyacid, and PDMAEMA or poly(diallyldimethyl ammonium chloride) (PDADMAC) as the polybase. For electrostatically-driven complexation, we expect that the critical salt concentration  for phase separation (phase separation regime) is maximum for intermediate pH (~ 6.5) conditions, when both PAA and PDMAEMA are highly charged. Surprisingly, we observe that the critical salt concentration for phase separation (phase separation regime) is maximum for low pH (≤ 4) conditions where PDMAEMA is highly charged but PAA is barely charged. We show that this could be explained by assuming a Flory parameter (χ+w = 0.75) between the PAA monomers and water, which is further justified by atomistic simulations. In the next section, we discuss the theoretical, experimental, and simulation approaches we have used to study pH and salt effects on polyelectrolyte complexation. In the “Results and Discussion” section, we show the comparison of theoretical and experimental results of the critical salt concentration of phase separation and water content and volume of the resulting dense phase, followed by a brief discussion of simulation results.

for phase separation (phase separation regime) is maximum for intermediate pH (~ 6.5) conditions, when both PAA and PDMAEMA are highly charged. Surprisingly, we observe that the critical salt concentration for phase separation (phase separation regime) is maximum for low pH (≤ 4) conditions where PDMAEMA is highly charged but PAA is barely charged. We show that this could be explained by assuming a Flory parameter (χ+w = 0.75) between the PAA monomers and water, which is further justified by atomistic simulations. In the next section, we discuss the theoretical, experimental, and simulation approaches we have used to study pH and salt effects on polyelectrolyte complexation. In the “Results and Discussion” section, we show the comparison of theoretical and experimental results of the critical salt concentration of phase separation and water content and volume of the resulting dense phase, followed by a brief discussion of simulation results.

2. Methods

2.1. Theory

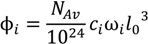

We model a representative polyelectrolyte complexation experiment, wherein aqueous solutions of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes prepared at the same pH and salt concentration (ionic strength) are mixed together. The net result is the formation of a phase-separated state under favorable conditions, or a single-phase solution when phase separation does not occur. The existence of phase separation and the concentration of different species in the dense and supernatant phases can be determined by minimizing the free energy difference of the system between the phase separated state and single-phase solution. Phase separation occurs when this free energy difference is negative. As pictured in Figure 1, the system consists of five species, namely, the polycations, polyanions, mobile cations, mobile anions, and water. Here, we assume that the counterions of polyions are identical to the salt ions of same charge and all ions are monovalent. Further reduction in the degrees of freedom is possible by assuming that the salt concentrations in the two phases are identical and that the polycation and polyanion have the same degree of polymerization, concentration, and net charge (but opposite sign). In that case, the onset of phase separation can be obtained from the inflection point in the plot of free energy versus polymer volume fraction and the binodal compositions can be obtained by the common tangent construction [10]. However, we are interested in the complexation behavior over the entire pH range, where the magnitude of the net charge of a polycation and a polyanion are not always comparable and the salt concentration can be substantially different in the two phases. Thus, we consider the more general case and numerically solve for compositions of all five species in the supernatant and dense phase. In the following, subscripts +, −, sp, sn, and w, denote the polycation, polyanion, mobile cation, mobile anion, and water, respectively. Also, the subscript after a polyion name indicates its average degree of polymerization.

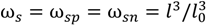

The volume fractions of the species, ϕi (i = +, −, sp, sn, w), can be related to their molar concentrations, ci, using the relation:

Here, NAv is the Avagadro number, l0 = 0.31 nm is the approximate size of a water molecule defined as the cube root of its molecular volume, and ωi is the ratio of molecular volume of species i to the molecular volume of water. The factor 1024 is a units conversion factor, as l0 is is nm, and ci is in Mol/L (M). In principle, ωi can be obtained using the actual molecular volume of each species, but such data are generally not available for polyions and often unnecessary given the approximate nature of the theory. In the original VO theory [17], all species were assumed to be of the same size as water molecules, i.e., ωi = 1 for all i. Spruijt et al. [10] also assumed that all species are of the same size but used that size as a fitting parameter instead of taking it equal to the size of water molecule. Both these studies also defined an “electrostatic length scale” that appeared in the prefactor of the DH term, which was again used as a fitting parameter and found to be roughly equal to 0.85 nm for the PAA-PDMAEMA system, close to the Bjerrum length of water at 20 °C (lB ≈ 0.71 nm). We propose a somewhat different approach that, in principle, can be used to generalize the theory to any pair of polyelectrolytes and any salt. ω+, ω−, and l are used as fitting parameters, representing the volume of a polycation monomer normalized by the molecular volume of water, the volume of a polyanion monomer normalized by the molecular volume of water, and the size of a salt ion, respectively. The volume of a salt ion normalized by the molecular volume of water is therefore given by  .

.

Figure 1.

Polyelectrolyte complexation in an aqueous mixture of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes, with their counterions and salt ions. Polycations, polyanions, and salt ions are represented with black lines, red lines, and symbols, respectively. A single-phase solution is observed when phase separation does not occur (top left) and distinct supernatant and dense phases are formed after phase separation (top right). A precipitate or a cloudy phase may also form instead of the coacervate phase shown in the picture. ν(c) and V are the volume fraction of dense phase and the total volume of the solution, respectively. Polyelectrolytes discussed in the paper are also shown in the figure.

Given the simplified nature of the theory, we do not seek to obtain ω+, ω−, and l, from first principles. Instead, these parameters are chosen such that the theoretical predictions of critical salt concentrations for different pairs of polyelectrolytes and different salts match with the corresponding experimental findings [1,35]. l is varied with the salt used and is found to be close to the cube root of average volume of unhydrated salt cation and salt anion. For example, we use l = 0.26 nm for KCl throughout this paper, which provides good agreement with experiments, while KCl has an average ion ion size (l) roughly equal to 0.262 nm. Here, the experimental l is taken to be the cube root of average volume of unhydrated ions, which in turn can be computed using their effective ionic radius [36]. ω+ (ω−) is varied with the choice of polycation (polyanion) and roughly characterizes the accessibility of charges on the monomer, with a higher magnitude signifying larger separation between charges. As an illustration of our fitting strategy for ω±, we consider the experimentally observed critical salt (KCl) concentrations of PAA147 with different polycations at pH ≈ 6.5 [1] (corresponding to f± ≈ 0.95) which increase in the order of polycation monomer size: poly(2-(N,N,N-trimethyl amino)-ethyl methacrylate (PTMAEMA95) < PDMAEMA151 < PAH80 [1]. Our calculation shows that the critical salt concentrations for these three systems can be fitted by using the same value of ω− = 1.2 for PAA and l = 0.26 nm for all systems, but different values of ω+ for three polycations: ω+ = 2.6 (PTMAEMA), ω+ = 1.8 (PDMAEMA), and ω+ = 0.1 (PAH). As we show later, small adjustments in ω± were further needed to precisely capture the experimentally observed critical salt concentrations for different chain lengths and polymer concentrations. Since we are mainly interested in the behavior of PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl system in this paper, we fix l = 0.26 nm and ω−(PAA) = 1.2 and use ω+ (PDMAEMA) and ω+ (PDADMAC) as fitting parameters.

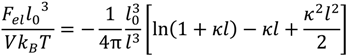

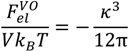

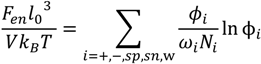

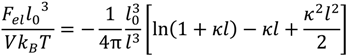

The free energy of the single-phase solution or the individual phases involves contributions from the translational entropies of various species and from electrostatic and van der Waals interactions between pairs of species. The entropic contribution to the free energy (Fen) is obtained using the Flory-Huggins theory, generalized to species of different molecular volume [37]:

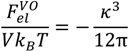

where N+ and N− are the degrees of polymerizations of polycation and polyanion, respectively. kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. We use the extended DH theory [38,39] to describe the electrostatic contribution to the free energy:

where N+ and N− are the degrees of polymerizations of polycation and polyanion, respectively. kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. We use the extended DH theory [38,39] to describe the electrostatic contribution to the free energy:

where κ is the inverse screening length. The DH term used in the original VO theory [17],

where κ is the inverse screening length. The DH term used in the original VO theory [17],  , can be obtained by taking the lowest order term of the Taylor’s expansion of Equation (3) for small κ, and is given by:

, can be obtained by taking the lowest order term of the Taylor’s expansion of Equation (3) for small κ, and is given by:

Although Equation (4) is an exact limiting law for κ → 0, it assumes point ions and its reliability is limited to very low salt concentrations (< 0.01 M). On the other hand, the extended DH theory accounts for the finite size of ions and outperforms DH theory for relatively higher salt concentrations, though being not strictly valid [38]. Note that both of these theories fail for very high salt concentrations (~2 M), where excluded volume effect of ions and higher-order electrostatic correlations are relevant.

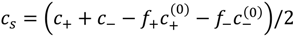

The inverse screening length κ appearing in Equations (3) and (4) is given by:

where f+ and f− are the fraction of charged monomers on the polybase and polyacid, respectively. We use lB = 0.71 nm (corresponding to Bjerrum length of water at 20 °C) throughout this paper, except in our discussion of the effect of dielectric constant variations in Section 3. Strongly charged polyelectrolytes such as PDADMAC have fi ≈ 1, but f+ and f− are affected by the pH and salt concentration for weakly charged polyelectrolytes (e.g., PAA, PDMAEMA). The Henderson–Hasselbalch equation relates f± to the pH and pKb (pKa) of the polybase (polyacid) as:

where f+ and f− are the fraction of charged monomers on the polybase and polyacid, respectively. We use lB = 0.71 nm (corresponding to Bjerrum length of water at 20 °C) throughout this paper, except in our discussion of the effect of dielectric constant variations in Section 3. Strongly charged polyelectrolytes such as PDADMAC have fi ≈ 1, but f+ and f− are affected by the pH and salt concentration for weakly charged polyelectrolytes (e.g., PAA, PDMAEMA). The Henderson–Hasselbalch equation relates f± to the pH and pKb (pKa) of the polybase (polyacid) as:

and:

and:

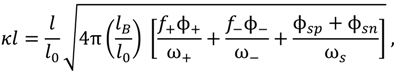

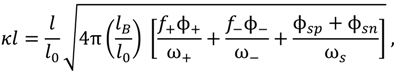

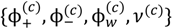

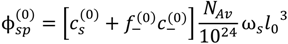

In general, pKa and pKb are functions of salt concentration, as shown for the case of PAA and PDMAEMA in Figure 2a. The empirical fits given in the plot are used to model f+ and f− as functions of pH and salt concentrations, using Equations (6) and (7). Here, cs in the empirical fit is taken as half of the difference between the total mobile ion concentration and overall counterion concentration, that is,  , such that cs = 0 for no added salt. Both f+ and f− increases with increase in salt concentration [40]. Also, as evident from Figure 2b, the magnitude of “charge asymmetry” (quantified by the absolute value of f+ − f−) at any fixed pH value away from the isoelectric point (f+ = f−) decreases with increase in salt concentration. It is important to point out that we have neglected the charge regulation effect of polycations (polyanions) due to the presence of oppositely charged polyanions (polycations), which would further decrease the magnitude of charge asymmetry. This is particularly relevant in the coacervate phase, where the polyion concentrations can be comparable to or larger than the salt concentration.

, such that cs = 0 for no added salt. Both f+ and f− increases with increase in salt concentration [40]. Also, as evident from Figure 2b, the magnitude of “charge asymmetry” (quantified by the absolute value of f+ − f−) at any fixed pH value away from the isoelectric point (f+ = f−) decreases with increase in salt concentration. It is important to point out that we have neglected the charge regulation effect of polycations (polyanions) due to the presence of oppositely charged polyanions (polycations), which would further decrease the magnitude of charge asymmetry. This is particularly relevant in the coacervate phase, where the polyion concentrations can be comparable to or larger than the salt concentration.

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental titration data [40] and best fitting functions for salt concentration dependence of pK for PAA500 and PDMAEMA527 solutions. (b) Difference between polycation and polyanion charge fractions (f+ − f−) for the PAA500-PDMAEMA527 system as a function of pH, evaluated using the fitting functions for PAA and PDMAEMA given in (a).

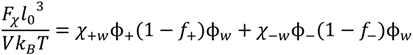

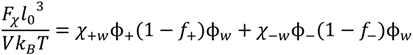

The non-electrostatic, solute-solute, and solute-solvent interactions between pairs of species i and j can be captured using the Flory parameter, χij. In this paper, we only consider these interactions between the neutral monomers and water with corresponding Flory parameters denoted as χ+w and χ−w for the neutral polybase and neutral polyacid monomers, respectively; we assume χij = 0 for all other pairs of species. That is, the non-electrostatic enthalpic contribution to the free energy, Fχ, is given by:

While this assumption that only the neutral monomers contribute to the above free energy is not necessarily valid, it is based on the reasoning that these interactions were not required by Spruijt et al. [10] at pH ≈ 6.5, where both PAA and PDMAEMA were highly charged (f± ≈ 1). Further, since the experimental measurements of χij are usually not available, we choose to keep fewer effective parameters to characterize the non-electrostatic interactions.

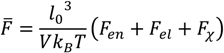

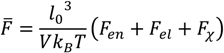

The free energy densities of the supernatant/dense phase or the single-phase solution can be obtained by summing the individual free energy contributions described above. That is, the dimensionless free energy density is given by:

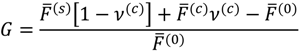

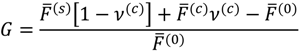

The condition of phase separation is determined by minimizing the function:

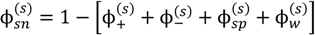

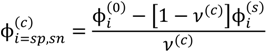

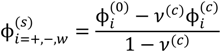

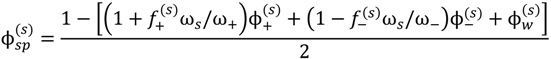

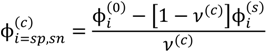

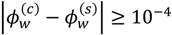

where minimization is performed with the constraints that the volume fraction of all species are in the range [0,1] and the sum of volume fractions of all species in a phase is unity. In this and the following, the superscripts (s), (c), and (0) refer to the supernatant phase, dense phase, and single-phase solution, respectively. Phase separation occurs if G < 0. G needs to be minimized with respect to four variables:  . Other variables can be found by using the species/overall mass balance and electroneutrality condition in the individual phases and are given by the following expressions:

. Other variables can be found by using the species/overall mass balance and electroneutrality condition in the individual phases and are given by the following expressions:

Minimization of G is performed using the simulated annealing method with additional constraints, vc ≥ 10(−6) and  , since a dense phase with very small volume or with nearly the same water content as the supernatant phase is difficult to resolve in experiments. Note that the free energy minimization approach we have employed to find the two phase equilibrium is equivalent to the standard approach of equating electrochemical potentials of components in the two phases [10], but is numerically more convenient for the present case.

, since a dense phase with very small volume or with nearly the same water content as the supernatant phase is difficult to resolve in experiments. Note that the free energy minimization approach we have employed to find the two phase equilibrium is equivalent to the standard approach of equating electrochemical potentials of components in the two phases [10], but is numerically more convenient for the present case.

The volume fractions of polyions in the single-phase solution,  and

and  , can be obtained from their overall molar concentrations,

, can be obtained from their overall molar concentrations,  and

and  , using Equation (1). The volume fractions of salt ions in the single-phase solution can also be given in terms of the overall salt concentration,

, using Equation (1). The volume fractions of salt ions in the single-phase solution can also be given in terms of the overall salt concentration,  , but also includes the concentrations of counterions of polyions. That is:

, but also includes the concentrations of counterions of polyions. That is:

and:

and:

where, l0 is in nm and concentrations are in M. The critical salt concentration is defined as the maximum value of

where, l0 is in nm and concentrations are in M. The critical salt concentration is defined as the maximum value of  at which phase separation occurs. Finally, the volume fraction of water in the single-phase solution is determined from the overall mass balance as:

at which phase separation occurs. Finally, the volume fraction of water in the single-phase solution is determined from the overall mass balance as:

2.2. Experiments

Experiments were performed for a range of pH (pH = 3–9 in increments of unity) and salt concentrations (0–3 M KCl in increments of 100 mM). PAA (Mn ≈ 43,000 g/mol, Mw/Mn ≈ 1.15) and PDMAEMA (Mn ≈ 82,700 g/mol, Mw/Mn ≈ 1.09) were purchased from Polymer Source as white powders; PDADMAC was purchased from Sigma Aldrich as a 35 wt% solution in water with average Mw less than 100,000 g/mol. A typical complexation experiment at a chosen pH and salt concentration was performed in two steps. First, stock solutions of both PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC were prepared at overall monomer concentration of 0.5 M in deionized Milli-Q water. The pH of stock solutions was adjusted to the desired value using 0.1 M KOH and 0.1 M HCl, while maintaining the monomer concentration of the stock solution at 0.5 M. Second, appropriate volumes of PDMAEMA/PDADMAC and PAA stock solutions were added to a vial containing the balance volume of deionized Milli-Q water and KCl, such that the total volume was V = 1.5 mL, monomer concentrations of PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC were 0.11 M each, and KCl concentration was at the desired level. After each addition step, the vial was vigorously shaken and well mixed. Complexation occurred immediately after addition of the last component to the vial. In some cases, we observed a white powder that settled to the bottom of the vial, which we refer as a “precipitate”. In some other cases, we observed a soft, clear, and transparent, gel-like polymer-rich phase that settled to the bottom of the vial, which we refer to as a “coacervate.” In between these two extremes, a dense, semi-transparent “cloudy phase” was also sometimes observed. The vials were then left to equilibrate for 5 days, followed by micro centrifugation at 2000 g for 15 min to fully separate the polymer-rich dense phase (bottom of the vial) from the polymer-depleted supernatant phase (top of the vial). The supernatant phase was pipetted out and discarded; the dense phase was carefully extracted from the vial and weighed. The wet dense phase was then dried in an oven at 100 °C, until all the water has evaporated, indicated by no change in weight on further drying. Weight measurements are performed on an analytical balance having a precision of 0.1 mg. The experimental yield of the wet (dry) dense phase is determined as the ratio of the weight of wet (dry) dense phase and total wet volume of both phases (V = 1.5 mL). The weight fraction of water in the coacervate, w(c), is computed as the difference between these weights divided by the weight of wet dense phase. This procedure is susceptible to errors arising from inaccuracies in pipetting out all of the supernatant phase from the vial and instrumental errors in measuring the weight of small volumes of the dense phase. It is worth noting that our experiments are performed by following a similar protocol as described in Spruijt et al. [10], by mixing equimolar amounts of PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC stock solutions prepared at the same pH, such that the pH of the final mixture can be considered to be the same as that of stock solutions. However, unlike Spruijt et al. [10] who considered only pH ≈ 6.5 case, we consider a wide range of pH values (pH = 3 − 9).

2.3. Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations were performed in GROMACS (Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations) using CHARMM27 force field at 298 K and 1 bar. PAA and PDMAEMA oligomers were constructed with Materials Studio® 6.5 and GROMACS-compatible topologies are generated using SwissParam [41] (Molecular modeling group, Swiss Insititute of Bioinformatics, Lausanne, Switzerland). 10-monomer chains of PAA and PDMAEMA were simulated with simple point charge (SPC) water molecules and K+ and Cl− ions in a cubic simulation box with periodic boundary conditions. The system was overall electroneutral. Both PAA and PDMAEMA were either fully neutral or fully ionized and the monomer concentration of both species was roughly equal to 0.11 M. Snapshots were taken after 10 ns of equilibrium simulations followed by 5 ns of production simulations. Thermodynamic properties were computed by averaging over production runs with a sampling frequency of 5 ps. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat was used for temperature control and the Parrinello-Rahman barostat for pressure control, both with a coupling constant of 0.5 ps. Electrostatic calculations were performed using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) scheme with a Fourier spacing of 0.12 nm and cubic interpolation. Bonds containing hydrogen atoms were constrained using a fourth-order LINCS (Linear Constraint Solver) algorithm. The number of hydrogen bonds between the two species is defined as the number of donor-acceptor pairs that are within a threshold distance (0.35 nm) and have the hydrogen-donor-acceptor angle less than 30 degrees.

3. Results and Discussion

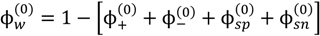

We test the generalized VO theory by comparing with experiments performed on aqueous PAA-PDMAEMA mixtures reported in [10,35], where both polyelectrolytes are of same concentration, are almost fully ionized (at pH ≈ 6.5), and are of similar degree of polymerization (N). As shown in Figure 3a for the PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl system, the critical salt concentration for phase separation (  ) first increases with N and plateaus to a nearly constant value for high N. This is explained by a reduction in the translational entropy of polyions with increase in N. For N ≫ 1, the entropic penalty of forming a polyion complex is minimal and the enthalpic gain on complexation (accounted by the DH term in our theory) dominates, thus leading to large magnitude of

) first increases with N and plateaus to a nearly constant value for high N. This is explained by a reduction in the translational entropy of polyions with increase in N. For N ≫ 1, the entropic penalty of forming a polyion complex is minimal and the enthalpic gain on complexation (accounted by the DH term in our theory) dominates, thus leading to large magnitude of  . Satisfactory agreement is found between the theory and experiment using ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 1.8, ω− (PAA) = 1.2, and l = 0.26 nm, but

. Satisfactory agreement is found between the theory and experiment using ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 1.8, ω− (PAA) = 1.2, and l = 0.26 nm, but  at small N is slightly underestimated by the theory (as also observed by Spruijt et al. [10]). One possible cause of this discrepancy is that the polyions with small N are not flexible enough for the validity of Flory-Huggins expression (Equation (2)) for the translational entropy of polyions. Note that the agreement can be improved by adjusting ω+ or ω− with changes in N, with some loss of generality. Figure 3b shows the magnitude of

at small N is slightly underestimated by the theory (as also observed by Spruijt et al. [10]). One possible cause of this discrepancy is that the polyions with small N are not flexible enough for the validity of Flory-Huggins expression (Equation (2)) for the translational entropy of polyions. Note that the agreement can be improved by adjusting ω+ or ω− with changes in N, with some loss of generality. Figure 3b shows the magnitude of  of the PAA500-PDMAEMA527 system for different salts as a function of the average ion size l (experimental data) and fitting parameter l (theory). In general, salts with small ion size (e.g., LiCl) have higher

of the PAA500-PDMAEMA527 system for different salts as a function of the average ion size l (experimental data) and fitting parameter l (theory). In general, salts with small ion size (e.g., LiCl) have higher  than salts with large ion size (e.g., KI), with some exceptions. In our theory, this effect is accounted by using a smaller value of l for smaller ions compared to larger ions, which in turn reduces the entropic penalty for phase separation and gives rise to a higher

than salts with large ion size (e.g., KI), with some exceptions. In our theory, this effect is accounted by using a smaller value of l for smaller ions compared to larger ions, which in turn reduces the entropic penalty for phase separation and gives rise to a higher  . In practice, an “effective” ion size l (reasonably close to the average ion size) can be chosen for any salt that allows a match to the experimental value of

. In practice, an “effective” ion size l (reasonably close to the average ion size) can be chosen for any salt that allows a match to the experimental value of  . However, the observed trend with different salts is often instead attributed to hydration effect of small ions not accounted in our theory [35]; small ions (e.g., Li+) have larger hydration shells than large ions (e.g., I−) and are therefore less effective in screening the electrostatic interactions between polyions.

. However, the observed trend with different salts is often instead attributed to hydration effect of small ions not accounted in our theory [35]; small ions (e.g., Li+) have larger hydration shells than large ions (e.g., I−) and are therefore less effective in screening the electrostatic interactions between polyions.

Figure 3.

(a) Critical salt concentration of PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl system against the average degree of polymerization of polyelectrolytes. Black line represents theoretical results with N+ = N− = N and the markers represent experimental results [10] with N+ ≈ N− and N = (N+ + N−)/2. The model parameters are  =

=  = 0.11 M, l = 0.26 nm, and ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 1.8. (b) Critical salt concentration of PAA500-PDMAEMA527 system for different salts against the average ion size l (experiments, given by markers) and fitting parameter l (theory, given by the line). The model parameters are

= 0.11 M, l = 0.26 nm, and ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 1.8. (b) Critical salt concentration of PAA500-PDMAEMA527 system for different salts against the average ion size l (experiments, given by markers) and fitting parameter l (theory, given by the line). The model parameters are  =

=  = 0.05 M, ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 2, and χ+w = χ−w = 0. In both (a) and (b), the charge fraction of polyelectrolytes are assumed to be constant, f+ = f− = 0.95.

= 0.05 M, ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 2, and χ+w = χ−w = 0. In both (a) and (b), the charge fraction of polyelectrolytes are assumed to be constant, f+ = f− = 0.95.

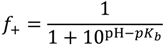

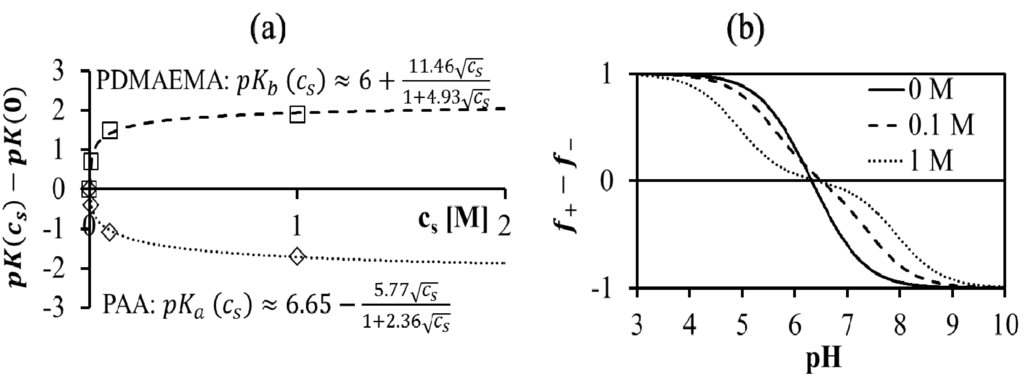

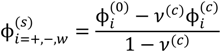

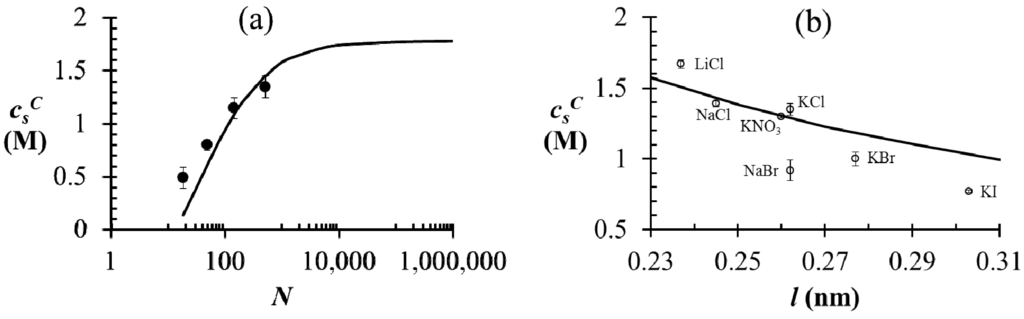

Now, we discuss our own experiments on PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl and PAA597-PDADMAC557-KCl systems, aimed at studying the effects of pH and salt concentration. Figure 4a shows the  of PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl mixtures against the mixture pH. For PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl system, the theory without additional hydrophobic effects (χ+w = χ−w = 0) predicts little or no coacervation (

of PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl mixtures against the mixture pH. For PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl system, the theory without additional hydrophobic effects (χ+w = χ−w = 0) predicts little or no coacervation (  ≈ 0 M) at low and high pH (pH < 4.5 and pH > 8), and maximum coacervation in the intermediate pH range (pH = 5 − 7.5). Overall, the profile is symmetric around pH ≈ 6.5. This is understandable since PAA at low pH and PDMAEMA at high pH are barely charged, thus resulting in vanishing of the electrostatic driving force for coacervation. However, the experimental results show a non-symmetric profile with

≈ 0 M) at low and high pH (pH < 4.5 and pH > 8), and maximum coacervation in the intermediate pH range (pH = 5 − 7.5). Overall, the profile is symmetric around pH ≈ 6.5. This is understandable since PAA at low pH and PDMAEMA at high pH are barely charged, thus resulting in vanishing of the electrostatic driving force for coacervation. However, the experimental results show a non-symmetric profile with  > 3 M for pH < 4.5. This necessitates the introduction of hydrophobic interactions (χ−w = 0.75), which satisfactorily captures this asymmetry in the profile of

> 3 M for pH < 4.5. This necessitates the introduction of hydrophobic interactions (χ−w = 0.75), which satisfactorily captures this asymmetry in the profile of  . This assumption appears to be justified for PAA, since PAA is relatively insoluble at low pH when most carboxylic groups are protonated and form intra-chain hydrogen bonds [42,43]. The PAA-PDADMAC-KCl system shows a non-symmetric profile even for the theory without additional hydrophobic effects, since PDADMAC is fully ionized at all pH values. However, additional hydrophobic interactions (χ−w = 0.75) are still needed to account for its high

. This assumption appears to be justified for PAA, since PAA is relatively insoluble at low pH when most carboxylic groups are protonated and form intra-chain hydrogen bonds [42,43]. The PAA-PDADMAC-KCl system shows a non-symmetric profile even for the theory without additional hydrophobic effects, since PDADMAC is fully ionized at all pH values. However, additional hydrophobic interactions (χ−w = 0.75) are still needed to account for its high  at low pH (pH < 5), since PAA is barely charged under those conditions. Note that, in both these cases, while the inclusion of additional hydrophobic interactions does capture the qualitative trend and theoretical predictions match well with experiments for intermediate and high pH, the quantitative agreement is relatively poor for low pH.

at low pH (pH < 5), since PAA is barely charged under those conditions. Note that, in both these cases, while the inclusion of additional hydrophobic interactions does capture the qualitative trend and theoretical predictions match well with experiments for intermediate and high pH, the quantitative agreement is relatively poor for low pH.

Figure 4.

(a) Critical KCl concentration against pH for mixtures of PAA597 with PDMAEMA526 (blue) and of PAA597 with PDADMAC557 (red) for lB = 0.71 nm. Symbols represent experimental data with error bars roughly the size of symbols. Symbols at  > 3 M imply phase separation over the entire experimental range (

> 3 M imply phase separation over the entire experimental range (  ≤ 3 M). Bold lines represent fits of the theory with no Flory interactions (χij = 0). Dashed lines are fits with additional Flory interactions between neutral PAA monomers and water, χ−w (PAA) = 0.7. In this and the following figures,

≤ 3 M). Bold lines represent fits of the theory with no Flory interactions (χij = 0). Dashed lines are fits with additional Flory interactions between neutral PAA monomers and water, χ−w (PAA) = 0.7. In this and the following figures,  =

=  = 0.11 M, ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 2, ω+ (PDADMAC) = 4.5, χ+w (PDMAEMA) = χ+w (PDADMAC) = 0, f− (PAA) and f+ (PDMAEMA) are determined using Equations (6) and (7) with pKa (PAA) and pKb (PDMAEMA) evaluated using the empirical equation given in Figure 2a, and f+ (PDADMAC) = 1. (b) Theoretical predictions of critical salt concentration against pH for PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl for different lB values and χ−w (PAA) = 0.75.

= 0.11 M, ω+ (PDMAEMA) = 2, ω+ (PDADMAC) = 4.5, χ+w (PDMAEMA) = χ+w (PDADMAC) = 0, f− (PAA) and f+ (PDMAEMA) are determined using Equations (6) and (7) with pKa (PAA) and pKb (PDMAEMA) evaluated using the empirical equation given in Figure 2a, and f+ (PDADMAC) = 1. (b) Theoretical predictions of critical salt concentration against pH for PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl for different lB values and χ−w (PAA) = 0.75.

One possible explanation for discrepancies at low pH is that we have neglected the effect of charge regulation due to other polyions and only accounted for the charge regulation due to salt ions; PAA might have substantially higher charge than that predicted by our theory due to the presence of PDMAEMA, which can regulate PAA charge. This however does not explain higher  at low pH compared to intermediate pH, where both polyions are almost fully charged. Another explanation could be the presence of additional, secondary interactions between polyions such as ion-dipole interactions speculated for the PAA-PDADMAC pair in an earlier study [43]. This effect could be included by using a non-zero Flory interaction between polyions χ+−, which is not considered here. Yet another, more reasonable, explanation is that even the extended DH approximation does not capture the electrostatic effects at salt concentrations > 2 M, where excluded volume effects of salt ions are expected to be important. If, in addition, polyion concentrations in the dense phase are also high (or equivalently, water content is low), the dielectric constant of the dense phase would be significantly smaller than the water dielectric constant used in the theory. The proper treatment of dielectric constant variations is complicated by the need to assume an expression for the concentration dependence of dielectric constant and account for the differences in the ion solvation energies between the coacervate and supernatant. However, we illustrate the effect of changes in dielectric constant in Figure 4b using a simplifying assumption that the dielectric constant is still same in the dense phase and supernatant, but less than that of water. This simplification ensures the applicability of our theory without extending it to include ion solvation effects and concentration dependence of dielectric constant. A decrease in dielectric constant indeed results in an increase in

at low pH compared to intermediate pH, where both polyions are almost fully charged. Another explanation could be the presence of additional, secondary interactions between polyions such as ion-dipole interactions speculated for the PAA-PDADMAC pair in an earlier study [43]. This effect could be included by using a non-zero Flory interaction between polyions χ+−, which is not considered here. Yet another, more reasonable, explanation is that even the extended DH approximation does not capture the electrostatic effects at salt concentrations > 2 M, where excluded volume effects of salt ions are expected to be important. If, in addition, polyion concentrations in the dense phase are also high (or equivalently, water content is low), the dielectric constant of the dense phase would be significantly smaller than the water dielectric constant used in the theory. The proper treatment of dielectric constant variations is complicated by the need to assume an expression for the concentration dependence of dielectric constant and account for the differences in the ion solvation energies between the coacervate and supernatant. However, we illustrate the effect of changes in dielectric constant in Figure 4b using a simplifying assumption that the dielectric constant is still same in the dense phase and supernatant, but less than that of water. This simplification ensures the applicability of our theory without extending it to include ion solvation effects and concentration dependence of dielectric constant. A decrease in dielectric constant indeed results in an increase in  as illustrated in Figure 4b for different lB (∝ 1/ϵr) values. Since the dielectric constant of polyelectrolytes (ϵr ∼ 1) is much smaller than water (ϵr ≈ 80), lB of a dense phase containing ~50 wt% water should be roughly twice (lB ∼ 1.4 at 20 °C) that of pure water (lB ≈ 0.71 nm at 20 °C), if the dielectric constant varies linearly with weight fraction of components. As we show later, water weight fractions at low pH (pH = 4 and pH = 5) are indeed low (∼ 50 wt%). Thus, we believe that the changes in dielectric constant on complexation could explain the behavior at low pH in Figure 4a, in addition to inclusion of hydrophobicity of neutral PAA monomers.

as illustrated in Figure 4b for different lB (∝ 1/ϵr) values. Since the dielectric constant of polyelectrolytes (ϵr ∼ 1) is much smaller than water (ϵr ≈ 80), lB of a dense phase containing ~50 wt% water should be roughly twice (lB ∼ 1.4 at 20 °C) that of pure water (lB ≈ 0.71 nm at 20 °C), if the dielectric constant varies linearly with weight fraction of components. As we show later, water weight fractions at low pH (pH = 4 and pH = 5) are indeed low (∼ 50 wt%). Thus, we believe that the changes in dielectric constant on complexation could explain the behavior at low pH in Figure 4a, in addition to inclusion of hydrophobicity of neutral PAA monomers.

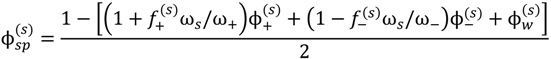

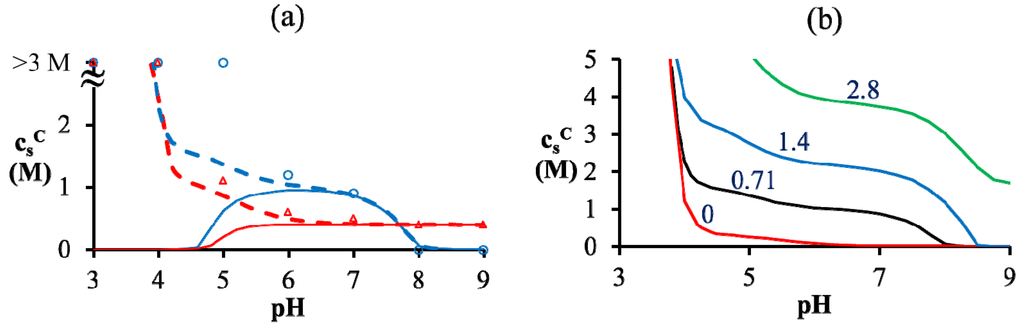

The variation in the degree of dissociation of polyelectrolytes due to pH changes gives rise to asymmetry in their binodal compositions as shown in Figure 5. For the PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl system at low pH (pH = 4 and pH = 5 in Figure 5a), PAA is only partially ionized but PDMAEMA is almost fully ionized, and therefore a larger amount of PAA is required to neutralize the relatively smaller amount of PDMAEMA in the dense phase. By species mass balance for the entire system, this corresponds to a smaller amount of PAA in the supernatant than compared to PDMAEMA, since the overall concentrations of PAA and PDMAEMA are identical. In other words, polycations (polyanions) try to compensate the charge on polyanions (polycations) in the dense phase through formation of a polyion complex, and the species mass balance dictates polyion concentrations in the supernatant. Moreover, since PAA is hydrophobic at low pH, it prefers to stay in the dense phase. Therefore, the concentration of PAA in the dense phase is higher than that of the PDMAEMA. A similar trend is observed for pH = 5 in the PAA-PDADMAC-KCl system (Figure 5b). Interestingly, a transition from associative to segregative phase separation with increase in salt concentration for pH = 4 occurs, where in segregative phase separation the dense phase is depleted of PDADMAC and mainly consists of PAA. This is evident from the unusual profile of the PDADMAC concentration in the dense phase (thick section of the bold green line in Figure 5b), which shows that the dense phase concentration of PDADMAC becomes smaller than its supernatant concentration after the crossover to segregative phase separation at around  ≈ 1 M. At intermediate pH (pH = 7 in the Figure 5a,b), both PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC are almost fully ionized, thus leading to almost equal concentration of the two polyions in the dense phase at high salt concentrations (> 1 M). However, the concentration of PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC in the supernatant/dense phase is significantly different for low salt concentrations (< 1 M). This can be attributed to the fact that the degree of dissociation of PAA and PDMAEMA (Figure 2b) at a given pH first increases with increase in salt concentration and then plateaus at high salt concentration, while the degree of dissociation of PDADMAC is always near unity. It is worth pointing out that Figure 5a,b are not binodal plots in a strict sense, since the concentrations of positive and negative salt ions are not assumed to be identical, cs+ ≠ cs−, and the salt concentrations in the supernatant and dense phases are not equal. While a quaternary phase diagram in terms of concentrations of polyions (c+ and c−) and salt ions (cs+ and cs−) could be more appropriate, we use a simpler representation in Figure 5a,b in terms of polyion concentrations, c+ and c−, and the total salt concentration,

≈ 1 M. At intermediate pH (pH = 7 in the Figure 5a,b), both PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC are almost fully ionized, thus leading to almost equal concentration of the two polyions in the dense phase at high salt concentrations (> 1 M). However, the concentration of PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC in the supernatant/dense phase is significantly different for low salt concentrations (< 1 M). This can be attributed to the fact that the degree of dissociation of PAA and PDMAEMA (Figure 2b) at a given pH first increases with increase in salt concentration and then plateaus at high salt concentration, while the degree of dissociation of PDADMAC is always near unity. It is worth pointing out that Figure 5a,b are not binodal plots in a strict sense, since the concentrations of positive and negative salt ions are not assumed to be identical, cs+ ≠ cs−, and the salt concentrations in the supernatant and dense phases are not equal. While a quaternary phase diagram in terms of concentrations of polyions (c+ and c−) and salt ions (cs+ and cs−) could be more appropriate, we use a simpler representation in Figure 5a,b in terms of polyion concentrations, c+ and c−, and the total salt concentration,  . Therefore, the polyion concentrations in the dense phase and supernatant do not appear to converge (c+ ≠ c−) at the critical salt concentration in some cases in Figure 5a,b as one might expect for a binodal plot. The convergence is particularly poor for the pH = 4 case, where larger hydrophobicity of PAA compared to PDMAEMA and PDADMAC results in a larger accumulation of PAA in the dense phase than required for neutralizing the polyanion charge. This, in turn, results in a larger accumulation of positive salt ions in the dense phase than compared to the supernatant phase,

. Therefore, the polyion concentrations in the dense phase and supernatant do not appear to converge (c+ ≠ c−) at the critical salt concentration in some cases in Figure 5a,b as one might expect for a binodal plot. The convergence is particularly poor for the pH = 4 case, where larger hydrophobicity of PAA compared to PDMAEMA and PDADMAC results in a larger accumulation of PAA in the dense phase than required for neutralizing the polyanion charge. This, in turn, results in a larger accumulation of positive salt ions in the dense phase than compared to the supernatant phase,  , in order to maintain charge neutrality in the dense phase. On the other hand,

, in order to maintain charge neutrality in the dense phase. On the other hand,  at the critical salt concentration for pH = 5 and pH = 7 cases in Figure 5a,b, which results in an apparent convergence (c+ ≠ c−) at the critical salt concentration.

at the critical salt concentration for pH = 5 and pH = 7 cases in Figure 5a,b, which results in an apparent convergence (c+ ≠ c−) at the critical salt concentration.

Figure 5.

Binodal compositions of polyelectrolytes in (a) PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl and (b) PAA597-PDADMAC557-KCl systems. The y-axes shows the total added salt concentration and the x-axis shows the concentrations of PAA (c−) and PDMAEMA/PDAMAC (c+) in the supernatant and dense phase. Dashed and bold lines represent concentrations of PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC, respectively. pH values are pH = 4 (green), pH = 5 (blue), and pH = 7 (red). Polyion concentration in the supernatant and dense phases are given by the left and right arm of the binodal, respectively, except for pH = 4 in (b), where the PDADMAC concentration in the supernatant and dense phases are represented using the thin and thick section of the bold line, respectively. χ−w (PAA) = 0.75 in both the figures.

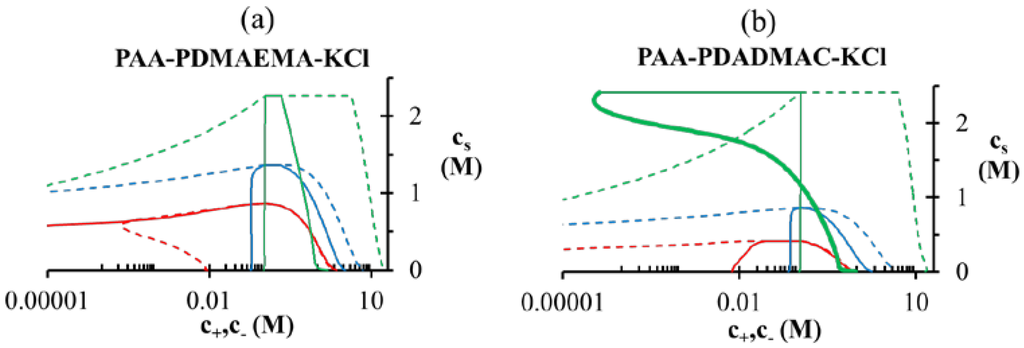

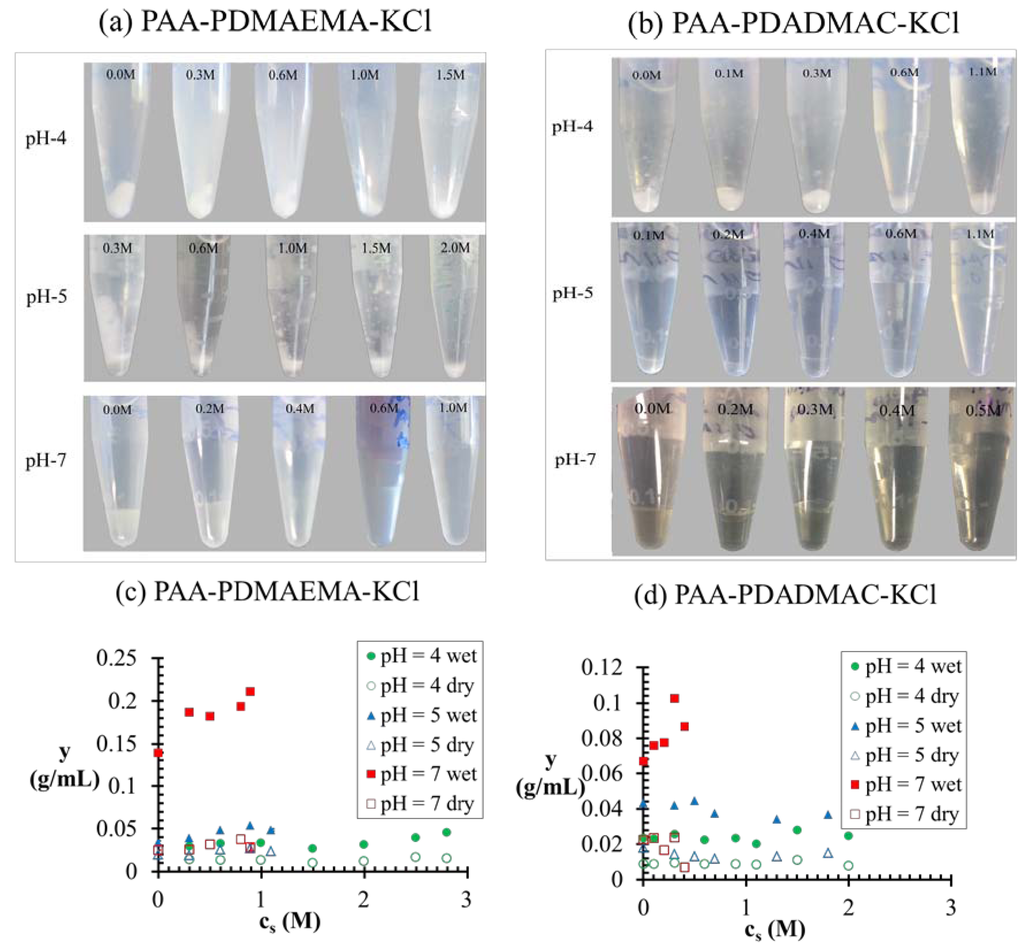

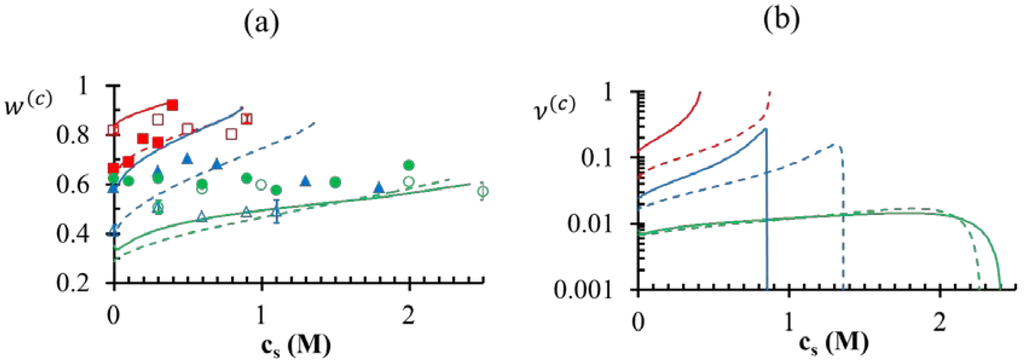

Figure 6a,b shows the pictures of vials containing polyelectrolyte complexes at different pH and salt concentrations for PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl, respectively. In general, we observe the transitions: precipitate → cloudy coacervate → clear coacervate with increase in pH and salt concentration for both these systems. Also, the dense phase formed for PAA-PDADMAC-KCl is generally more transparent and fluid (higher water content) than the coacervates formed by PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl under similar conditions. Moreover, the dense phase increases in volume with increase in salt concentration before the transition into a single-phase system at high salt concentration. The experimental yield of the wet/dry dense phase is shown in Figure 6c,d for the PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl systems, respectively. The maximum yield of wet dense phase is obtained for the pH = 7 case of both these systems, where we observe a clear coacervate. Figure 7 shows the comparison of experimental results with theoretical predictions of the weight fraction of water in the dense phase, w(c) (Figure 7a), and the theoretical predictions of the volume fraction of dense phase in the total volume, v(c) (Figure 7b). Given possible errors in the water content measurement outlined earlier (Section 2.2), we observe a reasonable agreement between predicted and experimental values of w(c), except at low salt concentrations (cs < 1 M) for pH = 4, plausibly due to the reasons stated in the descriptions of Figure 4. In addition, we observe that the minimum water content observed in experiments is ∼ 40 wt%, which may correspond to the maximum possible density of the polyion mixture. We use the theoretical results to explain general trends below. The dense phase with smallest w(c) and v(c) is predicted for pH = 4 (Figure 7a,b), with w(c) ≈ 0.4 for low salt concentration (< 0.5 M). This is the regime where the formation of precipitate/cloudy phase is expected since dense phases with less water are expected to have high relaxation times. However, since the theory does not differentiate between coacervate/precipitate/cloudy phases, it is not possible to predict directly from the calculations the precise location of the coacervate-to-precipitate transition. On the other hand, the polymer-rich phase is expected to be a clear coacervate at intermediate pH (pH = 7 in Figure 7a,b) and at high salt concentrations (> 0.5 M), since the theory does predict a high w(c) under these conditions. Also the volume fraction of the dense phase is considerably higher at pH = 7 than at pH = 4. Intermediate behavior is observed for pH = 5 for both systems (Figure 7a,b). It is worth pointing out that (in theory) we differentiate the dense phase from the supernatant phase by the volume fractions of water in these phases (  ). At the critical salt concentration, the volume fractions of the water in the two phases are equal (

). At the critical salt concentration, the volume fractions of the water in the two phases are equal (  ). Also, the maximum value of v(c) is generally attained at a salt concentration smaller than, but in the vicinity of, the critical salt concentration. Further increase in salt concentration beyond this point results in vanishing of the dense phase accompanied by a sharp decrease in the dense-phase volume (for pH = 4 and pH = 5 cases represented by green and blue lines, respectively, in Figure 7a,b) or the vanishing of the supernatant phase accompanied by a sharp increase in the dense phase volume (for pH = 7 case represented by red lines in Figure 7a,b).

). Also, the maximum value of v(c) is generally attained at a salt concentration smaller than, but in the vicinity of, the critical salt concentration. Further increase in salt concentration beyond this point results in vanishing of the dense phase accompanied by a sharp decrease in the dense-phase volume (for pH = 4 and pH = 5 cases represented by green and blue lines, respectively, in Figure 7a,b) or the vanishing of the supernatant phase accompanied by a sharp increase in the dense phase volume (for pH = 7 case represented by red lines in Figure 7a,b).

The differences between the phase behavior of PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl systems can be related to the relative strength of electrostatic interactions of PDMAEMA and PDADMAC. A recent study has shown that steric hindrance reduces the electrostatic interactions of quaternary amines in the case of PDADMAC [44]. Although PDADMAC is a strong polyelectrolyte, its quaternary nitrogen atom encounters greater steric hindrance to interaction with the carboxyl group on PAA, as compared to the tertiary nitrogen atom on PDMAEMA. Also, the nitrogen atom in a quaternary amine possesses less partial positive charge than do tertiary amines, because of the presence of four neighboring electron-donor alkyl groups in the former. In our theory, these steric effects are partly captured by using a larger ω+ value for PDADMAC (ω+ = 4.5) than compared to PDMAEMA (ω+ = 2.7). It is worth mentioning here the case of PAA-PAH-NaCl studied by Tirrell et al. [2,3]. Since PAH carries a charged primary amine group, it experiences little steric hindrance when compared with PDMAEMA and PDADMAC. Thus, the electrostatic interactions between PAA and PAH are much stronger than between PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC. While our experiments are performed on equimolar mixtures of PAA and PDMAEMA/PDADMAC both prepared at same pH (in the range 3 − 9), most of their experiments were performed on systems containing different molar ratios of PAA and PAH, where the PAA and PAH stock solutions were prepared at different pH values and the pH of the final mixture was a function of the molar ratio of PAA and PAH. They have however performed one set of experiments using equimolar mixtures of PAA and PAH [3] both prepared at the same pH (pH = 5 and pH = 7). In particular, they did not observe a single-phase solution for  ≤ 5 M for the pH = 5 case, which bears similarity to the low pH behavior we observe for the PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl systems. However, Priftis and Tirrell [9] observed a somewhat different trend in their experiments on polypeptide complexation. They observed that the critical salt concentration always increased with an increase in degree of dissociation of polyelectrolytes, as we find theoretically in the absence of hydrophobicity effects (χ+w = χ−w = 0) in Figure 4a. Further, all these studies [2,3,9] have reported a precipitate → coacervate transition with increase in salt concentration. The high critical salt concentrations at low pH observed in our experiments also shows resemblance to the increased stability of multilayer films containing weak polycarboxylic acids at low pH observed in an earlier experimental study [45], where the critical salt concentration required to dissolve the multilayers was found to increase dramatically at low pH.

≤ 5 M for the pH = 5 case, which bears similarity to the low pH behavior we observe for the PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl systems. However, Priftis and Tirrell [9] observed a somewhat different trend in their experiments on polypeptide complexation. They observed that the critical salt concentration always increased with an increase in degree of dissociation of polyelectrolytes, as we find theoretically in the absence of hydrophobicity effects (χ+w = χ−w = 0) in Figure 4a. Further, all these studies [2,3,9] have reported a precipitate → coacervate transition with increase in salt concentration. The high critical salt concentrations at low pH observed in our experiments also shows resemblance to the increased stability of multilayer films containing weak polycarboxylic acids at low pH observed in an earlier experimental study [45], where the critical salt concentration required to dissolve the multilayers was found to increase dramatically at low pH.

Figure 6.

Pictures of vials containing polyelectrolyte complexes for different pH and KCl concentrations for (a) PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl and (b) PAA597-PDADMAC557-KCl at salt concentrations indicated on the vials. The maximum salt concentration for each set of pictures is close to the critical salt concentration for that pH. The experimental yield (y) is defined as the weight of wet/dry dense phase divided by the total wet volume of both phases for the (c) PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl and (d) PAA597-PDADMAC557-KCl, as a function of salt concentration for different pH values.

Figure 7.

Theoretical and experimental predictions of (a) weight fraction of water in the coacervate and (b) volume fraction of coacervate, as a function of salt concentration for different pH values. Legends: PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl (dashed lines for theory and open symbols for experiments), PAA-PDADMAC-KCl (bold lines for theory and filled symbols for experiments), pH = 4 (green lines and symbols), pH = 5 (blue lines and symbols), and pH = 7 (red lines and symbols). χ−w (PAA) = 0.75 is used for theoretical predictions in (a) and (b). We expect an error up to 20% in the experimental results of w(c) (corresponding to ±5 water wt%), as estimated for some cases in Figure 7a using results from three independent experiments.

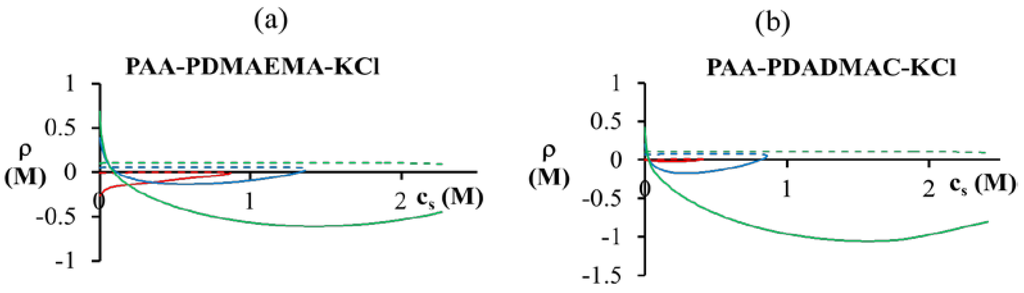

Since both the dense phase and supernatant are assumed to be electroneutral, the net charge due to polycations (polyanions) in the individual phases must be compensated either by polyanions (polycations) or by oppositely charged salt ions/counterions. If both polyions are hydrophilic (χ+w = χ−w = 0), the complexation of oppositely charged polyions drives the formation of an electroneutral complex due to a favorable entropic gain from counterion release. This explains why a higher concentration of barely charged polyion is generally present in the dense phase than of the almost fully ionized polyion (Figure 5). However, if the polyion is also hydrophobic (e.g., PAA at low pH), it may have even higher accumulation in the dense phase than that needed to compensate the PDMAEMA/PDADMAC charge. Further, the maximum accumulation of PAA in the dense phase is also limited by entropic considerations, since the supernatant phase cannot be completely devoid of PAA. These two competing tendencies are reflected in Figure 8 for pH = 4, where we plot the net charge imbalance between polycation and polyanion charges (ρ) against the overall salt concentration. At low salt concentrations (  < 0.1 M), PDMAEMA charges in the dense phase are not completely compensated (ρ > 0). The situation is reversed for high salt concentrations (

< 0.1 M), PDMAEMA charges in the dense phase are not completely compensated (ρ > 0). The situation is reversed for high salt concentrations (  > 0.1 M), where the PDMAEMA charges are overcompensated by PAA (ρ < 0). Some overcompensation by PAA in the dense phase is observed even at other pH values in the figure, but little or no overcompensation occurs in the supernatant phase (ρ ≈ 0).

> 0.1 M), where the PDMAEMA charges are overcompensated by PAA (ρ < 0). Some overcompensation by PAA in the dense phase is observed even at other pH values in the figure, but little or no overcompensation occurs in the supernatant phase (ρ ≈ 0).

Figure 8.

Net charge due to PDMAEMA or PDADMAC and PAA in the dense phase (bold lines) and supernatant (dashed lines) for (a) PAA597-PDMAEMA526-KCl and (b) PAA597-PDADMAC557-KCl. pH values are pH = 4 (green), pH = 5 (blue), and pH = 7 (red). χ−w (PAA) = 0.75 is used for both the figures.

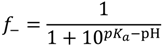

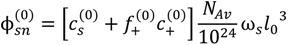

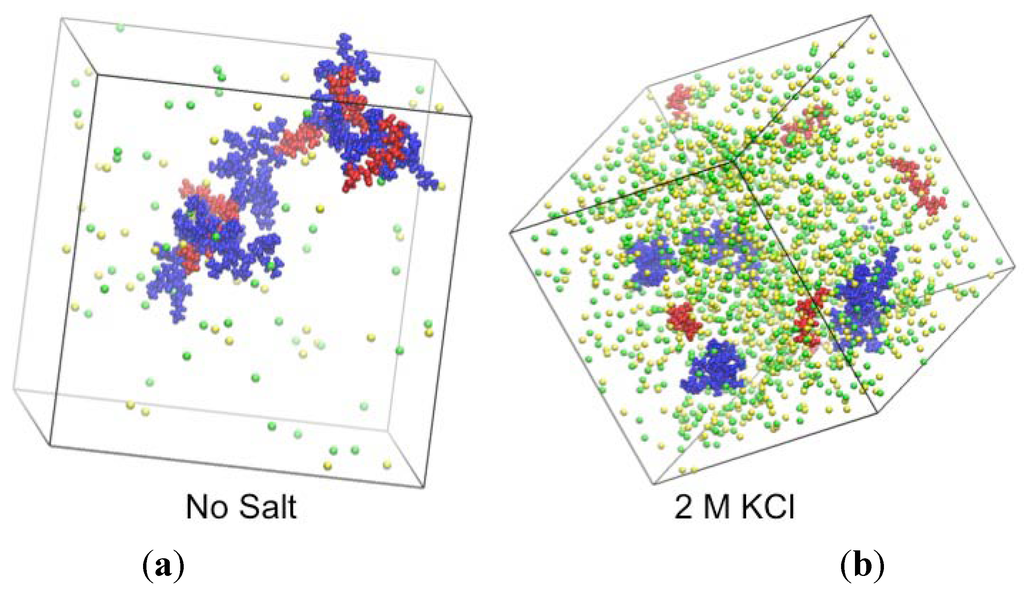

Finally, we perform atomistic simulations of a PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl aqueous mixture to confirm some of the findings of our theory. Since our simulations are performed with fixed-charge polyion models, pH effects related to protonation-deprotonation equilibria of polyions are not captured. Therefore, we consider the extreme case in which all polyions are fully ionized, representative of the intermediate pH range in Figure 2 ((pH = 5.5 − 7). As shown by snapshots in Figure 9, the simulations confirm the existence of phase separation in salt-free conditions and of a single-phase solution at 2 M KCl. The phase-separated state is identified as a fractal-like complex of PAA and PDMAEMA oligomers. This result is only an indication of likely phase separation, and the structure shown may not be representative of the actual coacervate structure in the much higher molecular weight polyelectrolytes of the experimental systems. Furthermore, the system size is too small to observe distinct supernatant and coacervate phases. Nevertheless, we observe that the polyion charges are mainly compensated by oppositely charged polyions, as predicted by the theory (Figure 8). We also compared the average numbers of PAA-water hydrogen bonds per monomer for fully ionized PAA and for neutral PAA. Similarly, we have computed the average numbers of hydrogen bonds for fully ionized and neutral PDMAEMA in separate simulations. Each neutral PAA monomer formed ≈ 2.5 hydrogen bonds with water, in contrast to each charged PAA monomer which formed ≈ 6 hydrogen bonds with water. This supports our assumption that neutral PAA monomers (χ−w = 0.75) present at low pH are much more hydrophobic than charged PAA present at high pH (χ−w = 0). On the other hand, both neutral and charged PDMAEMA monomers formed ≈ 2 hydrogen bonds with water. While the smaller number PDMAEMA-water hydrogen bonds compared to PAA-water justifies the use of a χ+w parameter for the PDMAEMA-water interactions, such a parameter would not necessarily be sensitive to pH changes. As we have shown previously, however, χ+w (PDMAEMA) = 0 provides a good fit for the critical salt concentration for the entire pH range, implying that this parameter is either not necessary or the effect of χ+w is captured by other fitting parameters. We also observed the formation of PAA-PAA hydrogen bonds (∼ 0.05 per monomer for 10-monomer chains at 0.11 M concentration of PAA) for neutral PAA oligomers but there was no hydrogen bonding between neutral PDMAEMA monomers. We believe that the hydrogen bonding between neutral PAA monomers will be more pronounced for longer PAA chains, which in fact may be crucial for the complexation behavior of aqueous polyelectrolyte mixtures containing PAA. This may account for the high critical salt concentration observed in our experiments with PAA at low pH. Further, it might explain the differences in the complexes formed at different pH values (Figure 6). At low pH (pH = 4 in Figure 6), the dense phase will be stabilized by both hydrogen-bonding between PAA monomers and electrostatic interactions between polyions. However, at intermediate and high pH (pH = 5 and pH = 6 in Figure 6), PAA monomers are charged, and the dense phase will be mainly stabilized by electrostatic interactions between polyions. The dense phase with additional hydrogen bonding formed at low pH might have lesser water content than compared to the purely electrostatic complexes formed at high pH (Figure 7a), since water molecules may be expelled from the dense phase in favor of PAA-PAA hydrogen bonds.

Figure 9.

Snapshots from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations of (a) aqueous PAA (red)-PDMAEMA (blue)-K+(yellow)-Cl−(green) mixture without salt and (b) with 2 M KCl. Water molecules are not shown. Fully ionized PAA and PDMAEMA chains (five chains each with 10-monomers per chain) are simulated in a cubic simulation box with length ≈ 9 nm, corresponding to a monomer concentration of ≈ 0.11 M for both PAA and PDMAEMA.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a generalized version of classical Voorn-Overbeek theory that describes the effects of pH and salt concentration on the complexation behavior of aqueous mixtures of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes. Theoretical predictions were found to be in reasonable agreement with experiments performed on PAA-PDMAEMA-KCl and PAA-PDADMAC-KCl mixtures with equimolar monomer concentrations for a range of pH and salt concentrations, after using fitting parameters for monomer/ion sizes and polyion hydrophobicity. In particular, we find that the critical salt concentration beyond which the mixture phase separates increases with an increase in the degree of dissociation and hydrophobicity of polyelectrolytes. Also, the binodal compositions of the two polyions become asymmetric for pH far away the isoelectric point, with substantial charge-overcompensation between the polyions. Interestingly, we find that the critical salt concentration is highest, not at neutral pH, where both polycation and polyanion are highly charged, but at low pH, where PAA is only slightly charged. We attribute this to the hydrophobicity of the neutral PAA monomers, which we account for in our model by a water-PAA Flory interaction parameter (χ), which is supported by atomistic simulations, showing fewer hydrogen bonds formed with water by neutral PAA monomers. Interestingly, for hydrophobic polyelectrolytes far from the isoelectric point, we predict that the phase separation shifts from associative to segregative, resulting in a dense phase with much smaller water-content. Further improvements to this theory should include the effects of charge regulation due to polyions, concentration dependence of dielectric constant and associated ion-solvation effects, higher-order electrostatic correlations and ion-size effects at high salt concentrations.

Acknowledgments

Prateek K. Jha thanks Jasper van der Gucht and Evan Spruijt for clarifications regarding the numerical scheme used in [1,10]. Authors thank Ali Salehi for stimulating discussions. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number OCI-1053575. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation, under grant DMR 0906587. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Author Contributions

Prateek K. Jha, Priyanka S. Desai, and Ronald G. Larson conceived the research. Prateek K. Jha and Ronald G. Larson developed the theory and molecular dynamics simulation protocol. Prateek K. Jha performed the theoretical calculations and molecular dynamics simulations, and analyzed theoretical and simulation results. Priyanka S. Desai and Ronald G. Larson designed the experiments. Priyanka S. Desai and Jingyi Li performed the experiments and analyzed experimental data. Prateek K. Jha, Priyanka S. Desai, and Ronald G. Larson wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Van der Gucht, J.; Spruijt, E.; Lemmers, M.; Cohen Stuart, M.A. Polyelectrolyte complexes: Bulk phases and colloidal systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 361, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollakup, R.; Beck, J.B.; Dirnberger, K.; Tirrell, M.; Eisenbach, C.D. Polyelectrolyte Molecular Weight and Salt Effects on the Phase Behavior and Coacervation of Aqueous Solutions of Poly(acrylic acid) Sodium Salt and Poly(allylamine) Hydrochloride. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 2376–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollakup, R.; Smitthipong, W.; Eisenbach, C.D.; Tirrell, M. Phase Behavior and Coacervation of Aqueous Poly(acrylic acid)−Poly(allylamine) Solutions. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhoud, S.; Cohen Stuart, M.A. Relaxation phenomena during polyelectrolyte complex formation. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2012, 255, 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungenberg de Jong, H.G.; Kruyt, H.R. Coacervation. (Partial Miscibility in Colloid Systems). Available online: http://www.dwc.knaw.nl/DL/publications/PU00015781.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2014).

- Oparin, A.I. The Origin of Life; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.L.; Schopf, J.W.; Lazcano, A. Oparin’s “Origin of Life”: Sixty Years Later. J. Mol. Evol. 1997, 44, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, D.; Megley, K.; Laugel, N.; Tirrell, M. Complex Coacervation of Poly(ethylene-imine)/Polypeptide Aqueous Solutions: Thermodynamic and Rheological Characterization. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 398, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, D.; Tirrell, M. Phase behaviour and complex coacervation of aqueous polypeptide solutions. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 9396–9405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruijt, E.; Westphal, A.H.; Borst, J.W.; Cohen Stuart, M.A.; van der Gucht, J. Binodal compositions of polyelectrolyte complexes. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6476–6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cohen Stuart, M.A.; van der Gucht, J. Phase Diagram of Coacervate Complexes Containing Reversible Coordination Structures. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 8903–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilay, E.; Kayitmazer, A.B.; Dubin, P.L. Complexation and coacervation of polyelectrolytes with oppositely charged colloids. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 167, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhishvili, S.A.; Kharlampieva, E.; Izumrudov, V. Where polyelectrolyte multilayers and polyelectrolyte complexes meet. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 8873–8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pristinski, D.; Zhuk, A.; Stoddart, C.; Ankner, J.F.; Sukhishvili, S.A. Linear versus Exponential Growth of Weak Polyelectrolyte Multilayers: Correlation with Polyelectrolyte Complexes. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 3892–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, B.M.; Engbersen, J.F. Responsive layer-by-layer materials for drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2012, 158, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Dell, E.J.; Freyer, J.L.; Campos, L.M.; Jang, W.D. Polymeric supramolecular assemblies based on multivalent ionic interactions for biomedical applications. Polymer 2014, 55, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, J.T.G.; Voorn, M.J. Phase separation in polyelectrolyte solutions. Theory of complex coacervation. J. Cell. Physiol. 1957, 49, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veis, A.; Aranyi, C. Phase separation in polyelectrolyte systems. I. Complex coacervates of gelatin. J. Phys. Chem. 1960, 64, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veis, A. A review of the early development of the thermodynamics of the complex coacervation phase separation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 167, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, D.J. Practical analysis of complex coacervate systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1990, 140, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Sato, H. Phase relationships of an equivalent mixture of sulfated polyvinyl alcohol and aminoacetalyzed polyvinyl alcohol in microsalt aqueous solution. Biopolymers 1972, 11, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tainaka, K.I. Effect of counterions on complex coacervation. Biopolymers 1980, 19, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlay, A.; Olvera de la Cruz, M. Precipitation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes in salt solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, M.; Joanny, J.F. Complexation between oppositely charged polyelectrolytes: Beyond the Random Phase Approximation. Eur. Phys. J. E 2001, 6, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlay, A.; Ermoshkin, A.V.; Olvera de La Cruz, M. Complexation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes: Effect of ion pair formation. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 9231–9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesheuvel, P.M.; Cohen Stuart, M.A. Cylindrical cell model for the electrostatic free energy of polyelectrolyte complexes. Langmuir 2004, 20, 4764–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesheuvel, P.M.; Cohen Stuart, M.A. Electrostatic free energy of weakly charged macromolecules in solution and intermacromolecular complexes consisting of oppositely charged polymers. Langmuir 2004, 20, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.L.B.; Lund, M.; Jönsson, B.; Åkesson, T. On the complexation of proteins and polyelectrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 4459–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskolkov, N.N.; Potemkin, I.I. Complexation in asymmetric solutions of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes: Phase diagram. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 8423–8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Popov, Y.O.; Fredrickson, G.H. Complex coacervation: A field theoretic simulation study of polyelectrolyte complexation. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Muthukumar, M. Entropy and enthalpy of polyelectrolyte complexation: Langevin dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Dobrynin, A.V. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Polyampholyte−Polyelectrolyte Complexes in Solutions. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 5300–5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoda, N.; Larson, R.G. Explicit-and implicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulations of complex formation between polycations and polyanions. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 8851–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, D.; Xia, X.; Margossian, K.O.; Perry, S.L.; Leon, L.; Qin, J.; de Pablo, J.J.; Tirrell, M. Ternary, Tunable Polyelectrolyte Complex Fluids Driven by Complex Coacervation. Macromolecules 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruijt, E. Strength, Structure and Stability of Polyelectrolyte Complex Coacervate. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Y. Thermodynamics of solvation of ions. Part 5—Gibbs free energy of hydration at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1991, 87, 2995–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.G. The Structure and Rheology of Complex Fluids; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McQuarrie, D.A. Statistical Mechanics; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T.L. An Introduction to Statistical Thermodynamics; Courier Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA,, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt, E.; Cohen Stuart, M.A.; van der Gucht, J. Linear Viscoelasticity of Polyelectrolyte Complex Coacervates. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoete, V.; Cuendet, M.A.; Grosdidier, A.; Michielin, O. SwissParam: A Fast Force Field Generation Tool for Small Organic Molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 2359–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmaljohann, D. Thermo- and pH-responsive polymers in drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1655–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litmanovich, E.A.; Chernikova, E.V.; Stoychev, G.V.; Zakharchenko, S.O. Unusual Phase Behavior of the Mixture of Poly(acrylic acid) and Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) in Acidic Media. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6871–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ankner, J.F.; Sukhishvili, S.A. Steric Effects in Ionic Pairing and Polyelectrolyte Interdiffusion within Multilayered Films: A Neutron Reflectometry Study. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 6518–6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumrudov, V.; Sukhishvili, S.A. Ionization-controlled stability of polyelectrolyte multilayers in salt solutions. Langmuir 2003, 19, 5188–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]