Abstract

This review provides a current status report of the field concerning preparation of fibrous mats based on biodegradable (e.g., aliphatic polyesters such as polylactide or polycaprolactone) and conducting polymers (e.g., polyaniline, polypirrole or polythiophenes). These materials have potential biomedical applications (e.g., tissue engineering or drug delivery systems) and can be combined to get free-standing nanomembranes and nanofibers that retain the better properties of their corresponding individual components. Systems based on biodegradable and conducting polymers constitute nowadays one of the most promising solutions to develop advanced materials enable to cover aspects like local stimulation of desired tissue, time controlled drug release and stimulation of either the proliferation or differentiation of various cell types. The first sections of the review are focused on a general overview of conducting and biodegradable polymers most usually employed and the explanation of the most suitable techniques for preparing nanofibers and nanomembranes (i.e., electrospinning and spin coating). Following sections are organized according to the base conducting polymer (e.g., Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 describe hybrid systems having aniline, pyrrole and thiophene units, respectively). Each one of these sections includes specific subsections dealing with applications in a nanofiber or nanomembrane form. Finally, miscellaneous systems and concluding remarks are given in the two last sections.

1. Introduction

There is a wide interest in the biomedical field to develop polymer systems with both biodegradable and electrically conducting properties. These systems have clear advantages like beneficial effects on wound healing (e.g., repair of damaged cranial, spinal and peripheral nerves, connective tissue and skin) and the absence of long-term health risk. In addition, the electrical response of conducting polymers makes feasible the local stimulation of desired tissue, time controlled drug release and the stimulation of either the proliferation or differentiation of various cell types. Nevertheless, it remains a considerable challenge to synthesize an ideal electroactive polymer that fulfills requisites of biocompatibility and biodegradability in order to minimize the inflammatory reaction in the host tissue that could be raised by the use of non-degradable particles.

One alternative strategy corresponds to the use of conducting polymer/biopolymer blends since unique properties that justify their potential technological applications in electrical, magnetic and biomedical devices can be achieved. Nanotechnology assists in the development of biocomposite nanofibrous scaffolds that can react positively to changes in the immediate cellular environment and stimulate specific regenerative events at molecular level to generate healthy tissues [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Recently, electrospinning has gained huge attention probably due to the great accessibility of fabrication of composites and incorporation of drugs, capability to prepare controlled and oriented nanofibers and feasibility to render scaffolds with the porosity required for effective tissue regeneration applications. Specifically, biopolymer-based conducting fibrous mats are of special interest for tissue engineering because they are able to stimulate specific cell functions or trigger cell responses in addition to the expected ability to physically support tissue growth [8]. Several properties are desired for tissue engineering applications and include conductivity, reversible oxidation, redox stability, biocompatibility, hydrophobicity, three-dimensional geometry and surface topography. Control over the surface properties of a biomaterial substrate is highly important because these properties determine the initial response of cultured cells. The modification of the surface of a biomaterial by distinct patterning can thus be used to mimic the native cellular environment. Micro- and nanofabrication technologies offer the capability to design a well-defined chemical composition and topology of the material substrate, suitable to control cell–substrate interactions [9].

Polymeric ultra-thin films are useful for several applications in biomedicine and specifically nanofilms can be used as plasters to be delivered, targeted and finely positioned in situ on surgical incisions, or to perform therapeutic or treatment tasks.

2. Base Materials

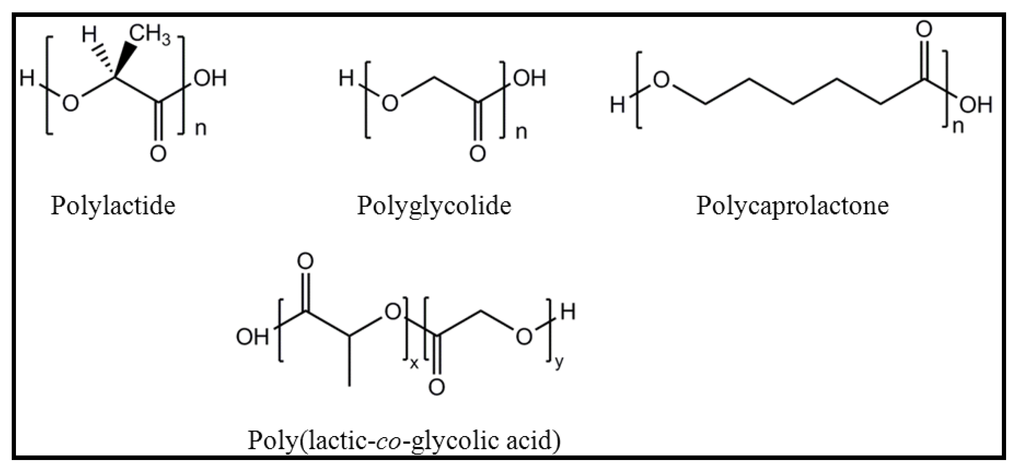

The requirements for a material to be used for tissue engineering purposes are biocompatibility and biodegradability since it should degrade with time and should be replaced with newly regenerated tissues. Polylactide (PLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), polyglycolide (PGL) and their copolymers [e.g., poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)] (Figure 1) are the synthetic polymers most usually employed, although continuous efforts are focused to design novel biomaterials with enhanced performance. The architecture of the biomaterial is also very important and specifically scaffolds constituted by electrospun nanofibers have promising features like big surface area for absorbing proteins and abundance of binding sites to cell membrane receptors. Different reviews are concerned with the formation of biodegradable nanomats by electrospinning and their potential use for tissue engineering applications [10,11], the generation of smart scaffolds [12] or the use of functional electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications [13].

Figure 1.

Scheme showing the chemical structure of main biodegradable polymer used in biomedicine.

Nanomembranes (NMs) constitute nowadays an interesting topic in the wide field of nanotechnologies. They can be defined as a freestanding or free-floating self-supported structure whose width-to-thickness and length-to-thickness aspect ratios both exceed 100 [14,15,16]. These quasi-2D structures have a thickness very close to the fundamental limits of the solid matter (they may be a few tens of atomic/molecular layers thick) and exhibit a host of unusual properties that make them useful for various applications in energy harvesting, sensing, optics, actuators, plasmonics and biomedicine [17,18,19]. The 2D geometry of such materials facilitates also integration into devices which can exploit quantum and other size-dependent effects.

Fabrication of nanofibers and membranes made of conductive electronic polymers has recently been demonstrated to be useful in the design and construction of nanoelectronic devices [20,21].

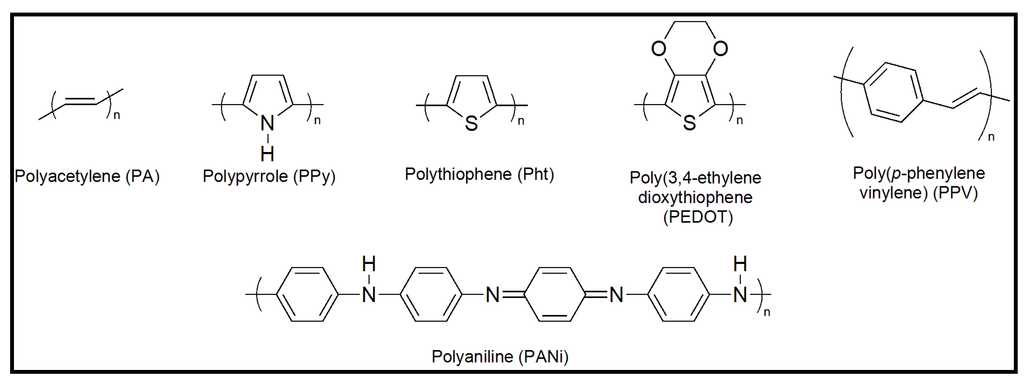

Common classes of organic conductive polymers (CPs) include polyacetylene (PA), polypyrrole (PPy), polythiophenes (PThs), polyaniline (PANi), and poly(p-phenylene vinylenes) (PPVs) (Figure 2), although not all have been considered for biomedical uses. Interestingly, different approaches have been formulated to synthesize nanofibers of conducting polymers (e.g., polyaniline nanofibers have recently been prepared by electrochemical polymerization using chronopotentiometery technique [22] and their surface subsequently modified by silver nanoparticles using cyclic voltametry [23]).

Figure 2.

Scheme showing the chemical structure of main conducting polymers.

Researchers have explored the utility of incorporating conducting polymers into biomaterials to take advantage of the beneficial effect of electrical stimulation on tissue regeneration such as nerve skeletal or other living tissues. For example, polyaniline and its derivatives were found to be able to function as biocompatible substrates, upon which both H9c2 cardiac myoblasts and PC12 pheochromocytoma cells can adhere, grow, and differentiate well [24,25]. Polypyrrole was shown to enhance the effect of nerve growth factor (NGF) in inducing neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells with electric stimulation [26]. Polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) and poled polytetrafluoro ethylene (PTFE) were found to promote enhanced neurite outgrowth in vitro and enhanced nerve regeneration in vivo as a consequence of either transient or static surface charges in the material [27].

3. Preparation of Nanofibers and Nanomembranes: Electrospinning and Spin Coating

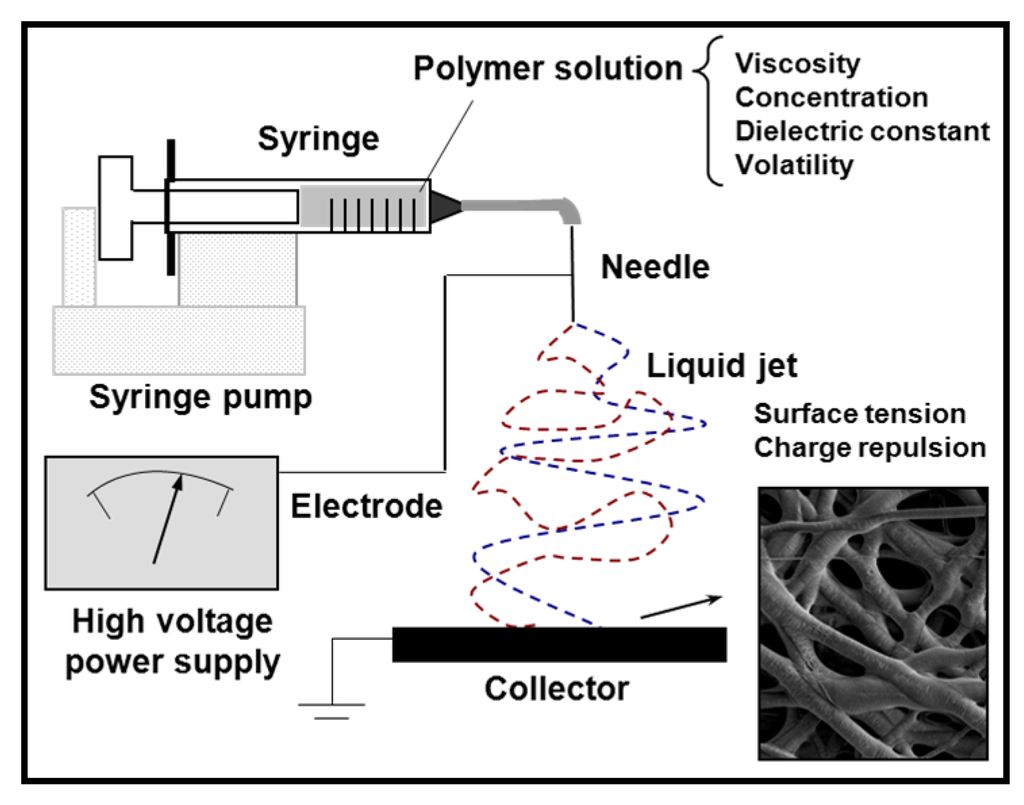

Ultrathin fibers from a wide range of polymer materials can be easily prepared by electrospinning [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] (Figure 3). This electrostatic technique involves the use of a high voltage field to charge the surface of a polymer solution droplet, held at the end of a capillary tube, and induce the ejection of a liquid jet towards a grounded target (collector).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram showing the electrospinning process.

The single jet initially formed is divided into multiple filaments by radial charge repulsion, which results in the formation of solidified ultrathin fibers as the solvent is evaporating. Morphology of fibers obtained onto the collector depends on the solution properties (e.g., viscosity, dielectric constant, volatility, concentration) and operational parameters (e.g., strength of the applied electrical field, deposition distance, flux) [30,32,33,34,35]. Electrospinning of some polymers may be problematic but in some cases experimental conditions can be properly adjusted. For example, it has recently been demonstrates that the application of a voltage of opposite polarity to the charges existing on a polyelectrolyte is an efficient solution that may significantly contribute to the development of new functional nanofiber materials [39].

Selection of the appropriate experimental conditions can lead to fibers with diameters that can range from several micrometers to few nanometers in an extremely rapid process (millisecond scale) [29]. The technique is also characterized by a huge material elongation rate (1000 s−1), high cross-sectional area reduction (105–106) that favors molecular orientation within the fiber, and becomes nowadays a simple one step approach for producing active matrices with high surface area [29]. The electrospun fibers can provide interconnected porous networks, which are interesting for drug gene/cell delivery, artificial blood vessels, wound dressings and substrates for tissue regeneration, immobilization of enzymes and catalyst systems.

Non-woven mats of electrospun nanofibers can mimic the extracellular matrices (ECM) since their architecture becomes similar to the collagen structure of the ECM (a 3D network of collagen nanofibers 50–500 nm in diameter). In addition, electrospun synthetic materials can offer several advantages for tissue regeneration: correct and controllable topography (e.g., 3D porosity, nanoscale size, and alignment), encapsulation and local sustained release of drugs (e.g., growth factors, antioxidants, anti-inflammatory agents), and surface functionalization. Electrospun nanofiber-mats can also be used for development of complex nanosensory systems to detect biomolecules (e.g., glucose-recognition) in a less than nanomolar concentrations [40].

Obtention of conductive nanofibers by electrospinning is not trivial and different strategies have been undertaken: (a) Incorporation of conductive particles [e.g., carbon nanotubes (CNT)] into the fibers, being usually necessary a surface treatment of particles in order to increase their affinity for the polymer matrix; (b) Direct electrospinning of conducting polymers with problems related to their stiffness and low solubility; (c) Blending the conducting polymer with another electrospinnable polymer (used as a carrier), being the detriment of the electronic properties the major inconvenience; and (d) Coating electrospun nanofibers with conductive materials.

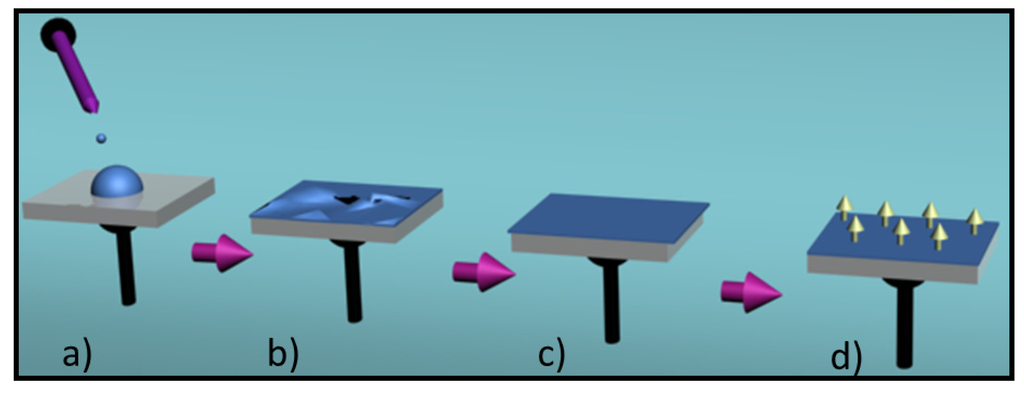

Spin coating is an useful technique for preparing uniform thin films with thicknesses below 10 nm. Basically a polymer solution is placed on a flat substrate, which is then rotated at high speed in order to spread the fluid by centrifugal force (Figure 4). The thickness of the film depends on the angular speed of spinning and the amount and concentration of the solution. Usually a sacrificial layer is deposited over the permanent support. The formed film is separated by destroying this layer after the fabrication procedure.

Figure 4.

Spin coating process involves the following steps: (a) Solution deposition; (b) Substrate acceleration; (c) Constant spinning rate; and (d) Drying and separation (not shown).

4. Conducting and Biodegradable Systems Based on Aniline Units

4.1. Development of Novel Biodegradable Samples Having Aniline Units

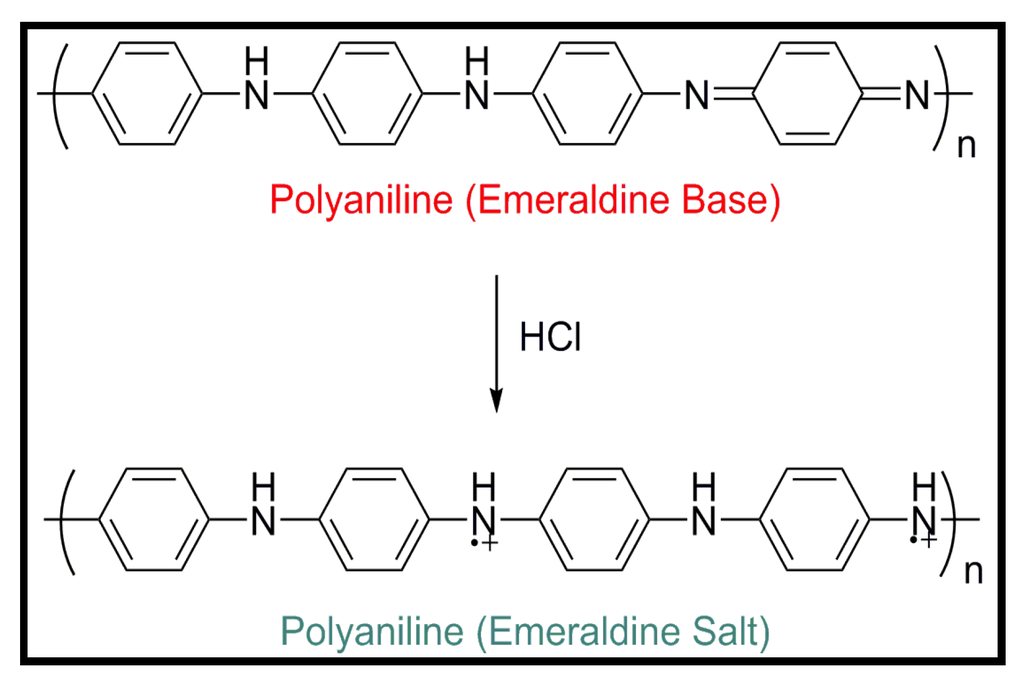

The primary chain of polyaniline consists of a combination of equal numbers of benzenoid-amine sites which react with oxydizing analytes and quinoid-imine sites which react with reducing and protonating analytes. This base form, known as emeraldine, is insulating but its conductivity can be tuned by doping from 10−1 up to 100 S/cm and more. Upon to exposure to aqueous protonic or functionalized acids, –N= sites become protonated, while maintaining the number of electrons in the polymer chain constant, and the conducting emeraldine salt form (PANiES) is achieved (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Chemical structure of polyaniline (emeraldine base) and transformation to a conductive salt by prototonation in an acid medium.

One strategy to get conductive and biodegradable polymers related to polyaniline is based on joining a biodegradable polymer (e.g., polyactide or chitosan) with heterocyclic oligomers of aniline. In fact, oligoanilines with well-defined chain lengths have been the model compounds for the electrical, magnetic, optical, and structural properties of PANi. Thus, many polymers containing oligoanilines as the side chains or even in the main chain have been designed and synthesized to obtain new electroactive materials. Different derivatives involving aniline trimers, tetramers and pentamers merit to be explained in a more detailed way.

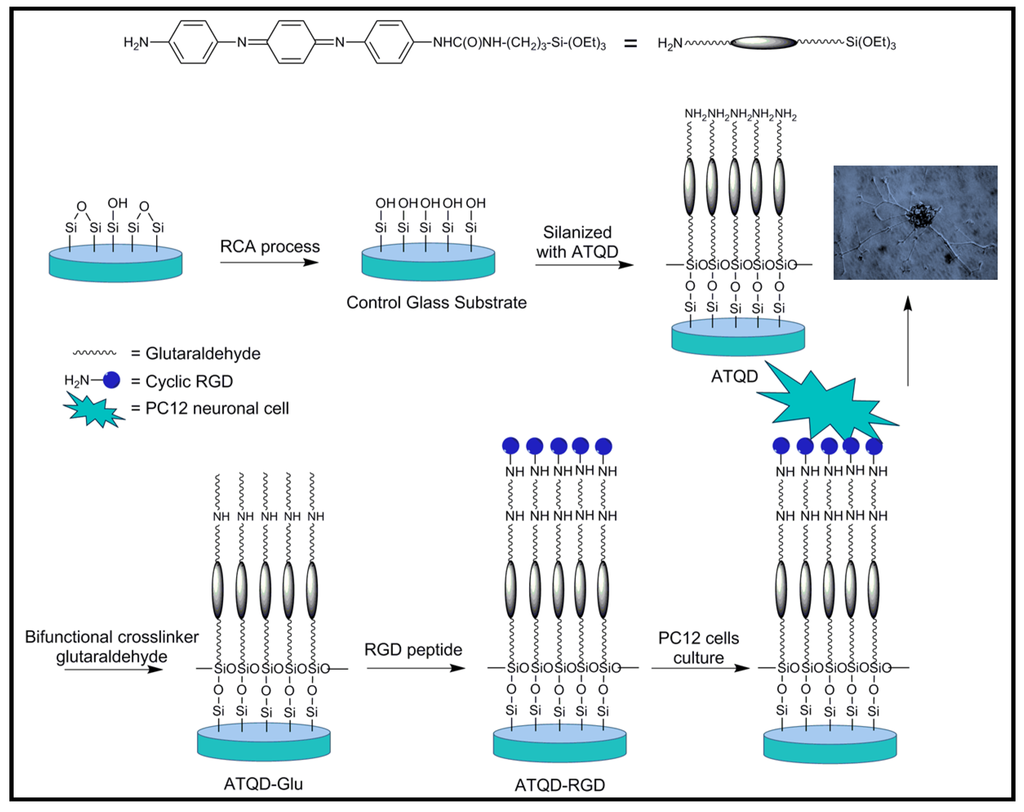

Wei et al. [41] demonstrated that an electroactive silsequioxane precursor containing an aniline trimer [i.e., N-(4-aminophenyl)-N′-(4′-(3-triethoxysilyl-propyl-ureido) phenyl-1,4-quinonenediimine) (ATQD)] could be a promising biomaterial for tissue engineering. To this end, self-assembled monolayers of ATQD on glass substrates were covalently modified with an adhesive oligopeptide, cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) (Figure 6). The mean height of the monolayer coating on the surfaces was ~3 nm, as measured by atomic force microscopy. The bioactive, derivatized electroactive scaffold material, ATQD-RGD, supported adhesion and proliferation of PC12 neuronal-like cells. Importantly, electroactive surfaces stimulated spontaneous neuritogenesis in PC12 cells, in the absence of neurotrophic growth factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF). Hence covalent grafting of bioactive molecules, such as adhesion peptides, appears as an effective strategy to improve the biocompatibility of conventionally non-biocompatible materials and consequently may allow to overcome the apparently poor cell biocompatibility of PANi.

Figure 6.

Scheme showing the preparation of self-assembled monolayers of ATQD-RGD, inset reproduced with permission from [41]. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.

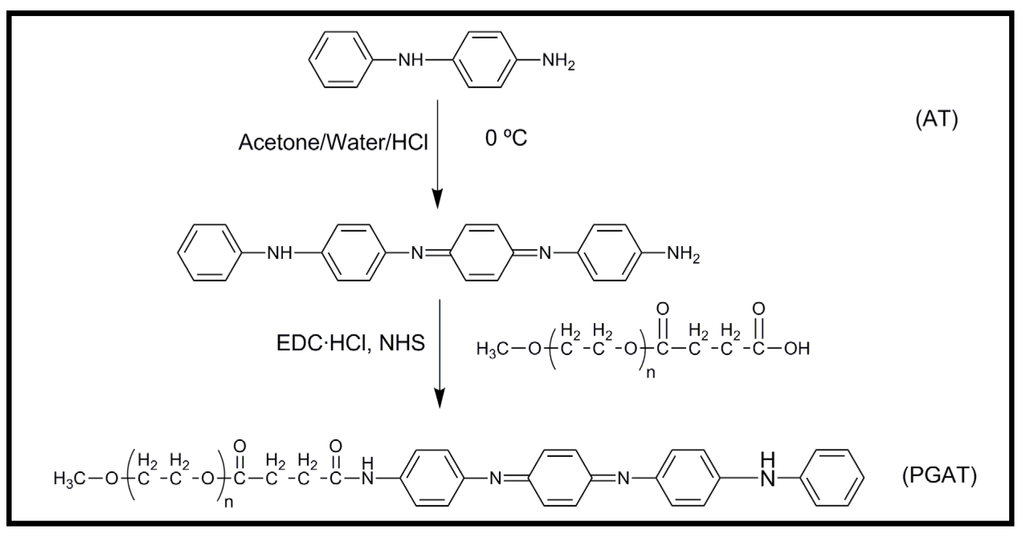

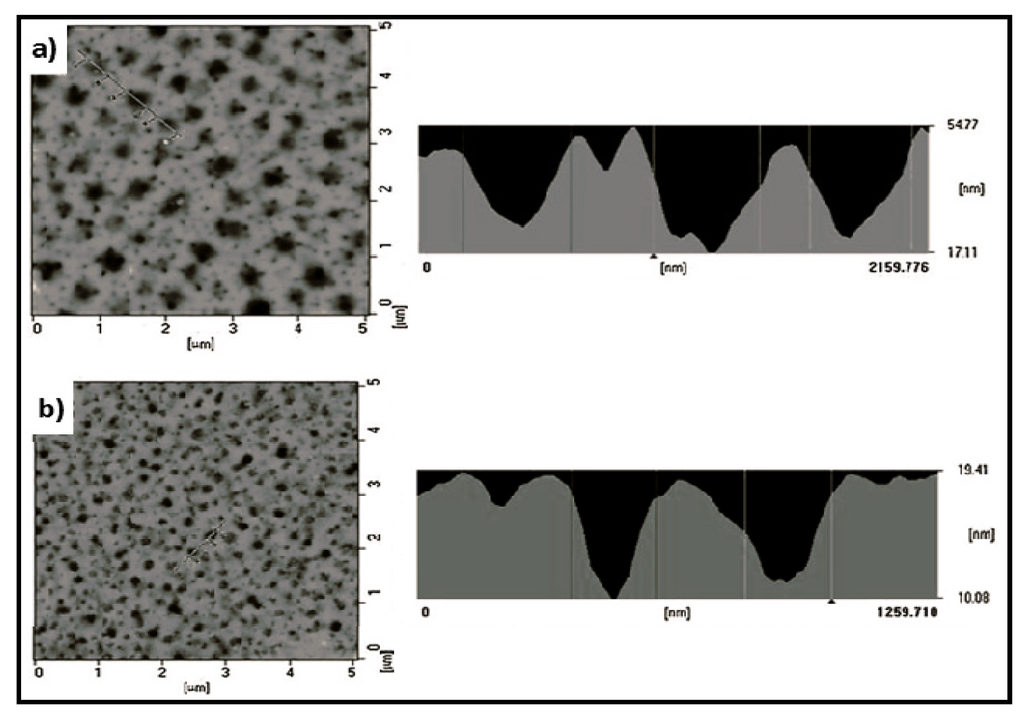

A novel diblock copolymer (mPEG-b-TEA, PGAT) was synthesized by conjugating the electroactive aniline tetramer (AT) and poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether (mPEG) (Figure 7). The advantage of this block copolymer was its relatively good solubility in water and in most organic solvents. The copolymer was also mixed with different ratios of poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA) in order to prepare biodegradable and electroactive PLLA/PGAT polymer blends [42]. Thin films (35–45 nm) of these materials were prepared by spin coating polymer blend chloroform solutions onto the surface of a silicon substrate. The surface topography of films changed with the composition of the blend (Figure 8), being observed large and regular micro-domains that expanded from 200 to 450 nm as the PGAT ratio increased. As the solvent evaporated during the process, micro-phase separation propagated throughout the film, and finally, a cylindrical micro-domain array was achieved. A large nanochannel structure was observed as a consequence of the flexibility and stronger affinity of mPEG chains to chloroform than that of PLLA. Therefore, chloroform served as a selective solvent and preferentially expanded the volume fraction of the mPEG microdomain. Blends exhibited reduced cytotoxicity as compared to AT due to the introduction of the biocompatible PLLA moiety. Blends showed an electroactivity that could accelerate the differentiation of rat C6 glioma cells.

Figure 7.

Synthesis scheme for the preparation of PGAT diblock copolymers.

Figure 8.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of PLLA/PGAT samples containing (a) 33 wt % and (b) 10 wt % of PGAT. Reprinted with permission from [42]. Copyright 2011 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.

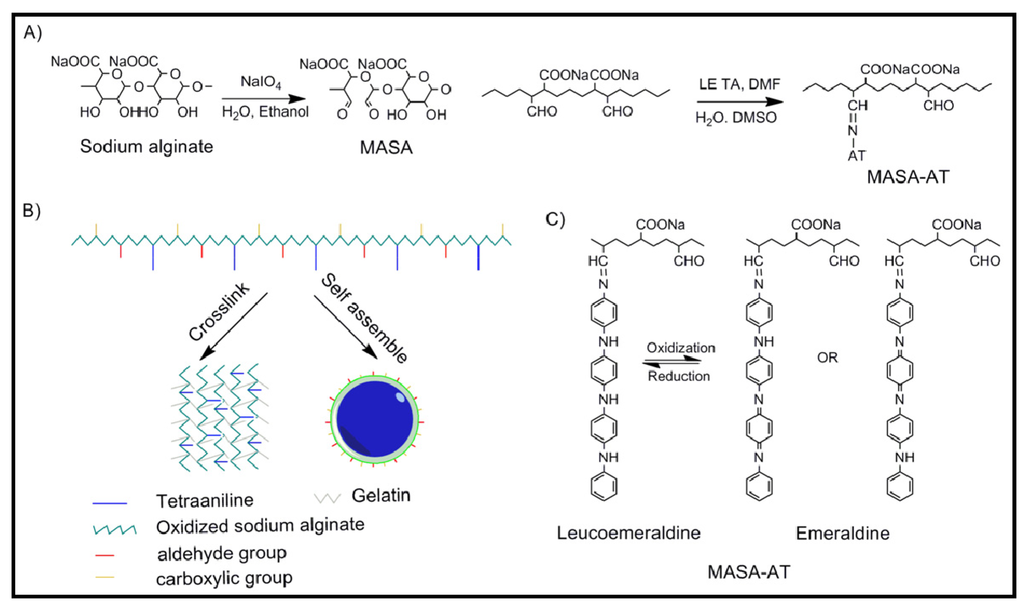

A polysaccharide crosslinker of tetraaniline grafting oxidized sodium alginate with a large amount of aldehyde and carboxylic groups (Figure 9a) has been synthesized by the condensation of terminal amino groups in phenyl/amino-capped tetraaniline (AT) with the aldehyde groups in multialdehyde sodium alginate (MASA) [43]. Copolymers can be obtained with different content of graft AT which is linked to the main chain through highly stable conjugated imine groups. The novel copolymer has interesting properties that justify its potential applications in biomedical fields such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, and nerve probes where electroactivity is required. Thus, the copolymer is water soluble under any pH, biodegradable, electroactive, and noncytotoxic. Furthermore, it can self-assemble into nanoparticles with large active functional groups on the outer surface and alternatively it can be used to crosslink materials with amino and aminoderivative groups like gelatin (via formation of Schiff base or amide through carbodiimide chemistry or electrostatic interaction) to form hydrogels (Figure 9b). MASA-AT only had one pair of reversible redox peaks (the mean redox potential was 0.48 V), which were ascribed to the conversion between leucoemeraldine state and emeraldine state (Figure 9c).

Figure 9.

(a) Scheme based on [43] showing the synthesis of the multialdehide sodium alginate (MASA) and the tetraaniline-graft-multialdehide sodium alginate (MASA-AT); (b) Self-assembling and crosslinking capabilities of MASA-AT molecules; and (c) Conversions of MASA-AT between different oxidation states. Copyright 2011 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.

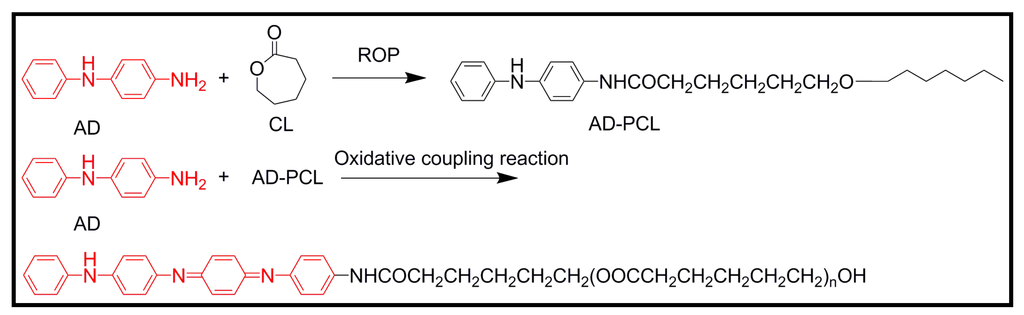

A universal strategy for the facile synthesis of degradable and electroactive block copolymers based on aniline oligomers and polyesters in a two-step approach has recently been reported [44]. Polyesters with an aniline dimer (AD) segment were first obtained by controlled ring opening polymerization (ROP) of a lactone (e.g., caprolactone) initiated by the amine group of AD. The postpolymerization modification via an oxidative coupling reaction between AD and a polyester was then used to form the electroactive segment AT in the copolymers (Figure 10). Thus, diblock copolymers with a controlled structure and molecular weight (i.e., 1300–2800 g/mol) were formed with a rigid AT segment at the chain end as one block and the long degradable flexible PCL as the other block. Furthermore, electrical conductivity of the block copolymers ranged from 6.3 × 10−7 to 1.03 × 10−5 S/cm depending on their AT content.

Figure 10.

Two-step approach to prepare degradable and conductive block copolymers having aniline tetramer end groups.

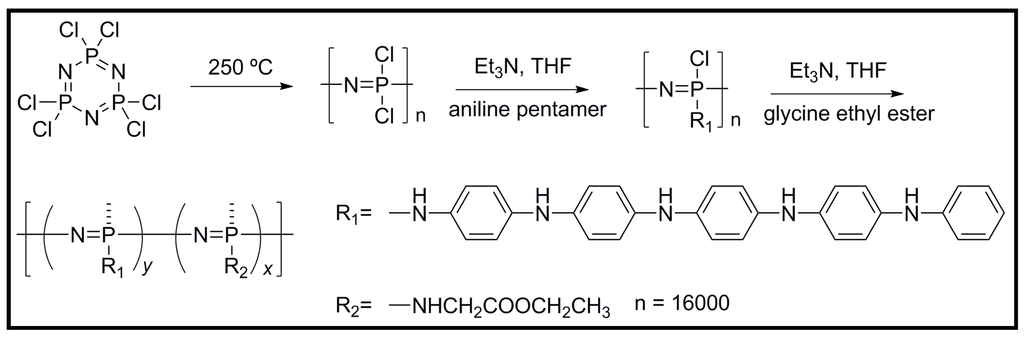

A novel electrically conductive biodegradable polyphosphazene polymer containing an aniline pentamer (AP) and glycine ethyl ester (GEE) as side chains was obtained by a nucleophilic substitution reaction (Figure 11) [45]. The electrical conductivity of the polymer was ~2 × 10−5 S/cm (i.e., in the semiconducting region) upon protonic-doped experiments. Furthermore, the polymer was proved to promote cell adhesion and proliferation according to in vitro assays with RSC96 Schwann cells. The as-synthesized polymer also showed good solubility in common organic solvents and good film-forming properties, and consequently potential applications as scaffolds for neuronal and cardiovascular tissue engineering were claimed [46].

Figure 11.

Structure and synthesis scheme for poly[(glycine ethyl ester)x(aniline pentamer)y phosphacene] (PGAP).

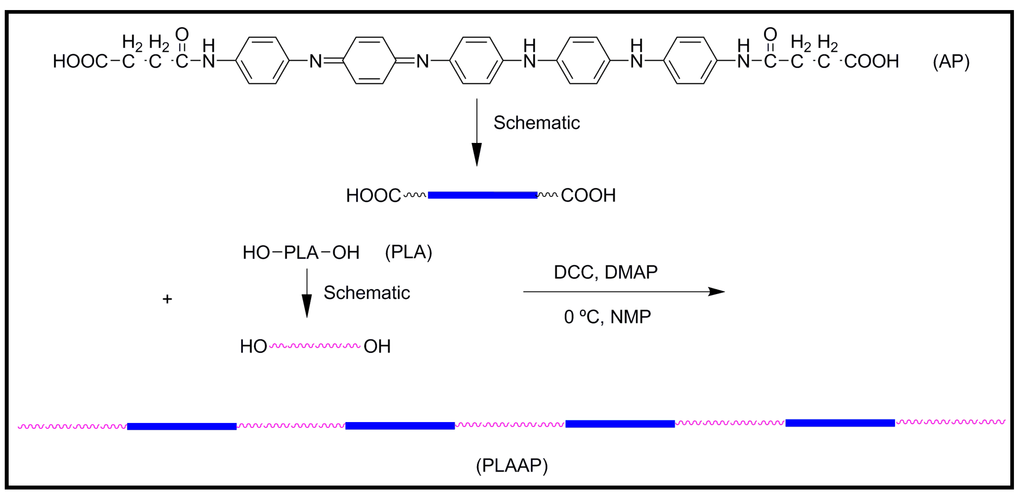

A multiblock copolymer (PLA-co-AP) was synthesized by the condensation of hydroxyl-capped poly(l-lactide) and carboxyl-capped aniline pentamer (Figure 12). The copolymer exhibited excellent electroactivity, solubility, and biodegradability. Mechanical properties appeared promising for its application as scaffold material with the tensile strength of 3 MPa, tensile Young’s modulus of 32 MPa, and breaking elongation rate of 95%. The compatibility of PLA-co-AP copolymer was assayed in vitro, being found that it was innocuous, biocompatible, and helpful for the adhesion and proliferation of rat C6 cells. Moreover, PLA-co-AP was able under stimulation by electrical signals to accelerate the differentiation of rat neuronal pheochromocytoma PC12 cells [47].

Figure 12.

Schematic synthesis route and structure of PLA-co-AP copolymer.

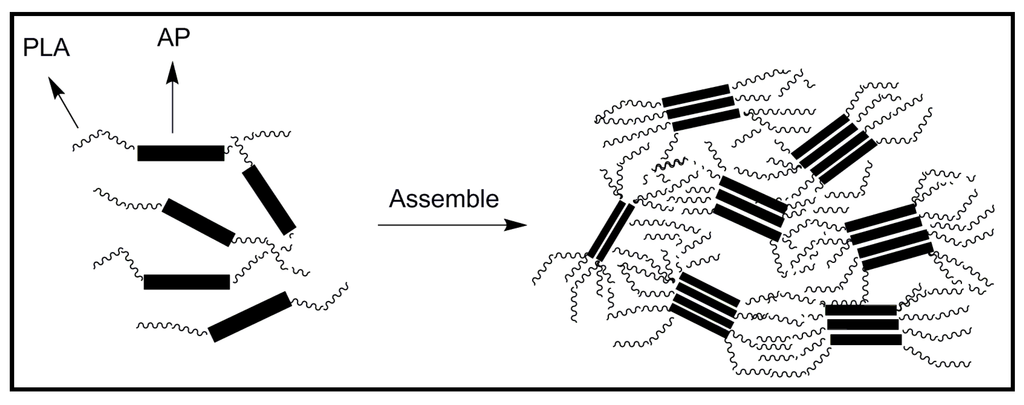

A PLA-b-AP-b-PLA triblock copolymer was also synthesized [48], being demonstrated that it posses electroactivity and good biodegradability. This type of block copolymers could undergo self-assembly and form micro-phase separation. Thus, the soft PLA segments tended to aggregate together to form a continuous matrix, while the AP hard segments formed discontinuous domains (Figure 13). Electric conduction was easy within the AP domains while between two adjacent domains conduction should occur by the tunnel effect through the PLA matrix and therefore, the apparent conductivity significantly decreased.

Figure 13.

Schematic representation of the self-assembling of PLA-b-AP-b-PLA triblock copolymers.

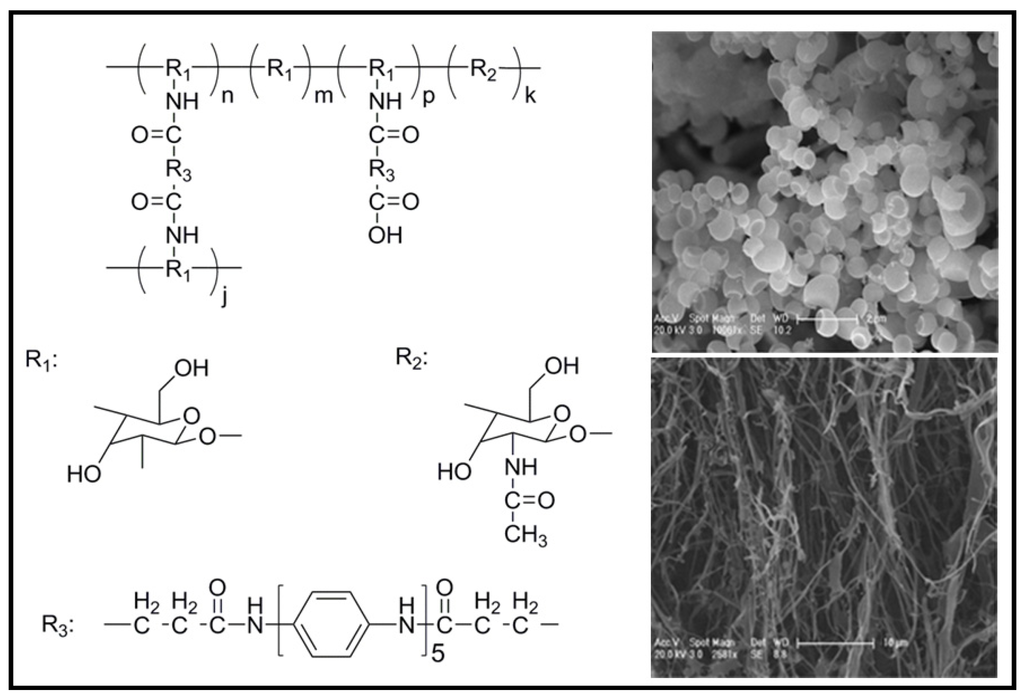

However, it was difficult to control the final oligoaniline content and hydrophilicity of the materials with the proposed procedure. It should be pointed out that most of these polymers were only soluble in organic solvents resulting in environmental concerns. Therefore, the development of electroactive polymers able to dissolve in nontoxic aqueous media is required. The incorporation of oligoaniline into water-soluble polymers [e.g., chitosan (CS)] is a challenging task (Figure 14) [49]. Specifically, an aniline pentamer with a terminal carboxylic group at each end was synthesized and subsequently activated with N-hydroxysuccinimide to allow the further condensation with amine groups of chitosan. The obtained amphiphilic polymers were able to self-assemble into 200−300 nm micelles by dialysis against deionized water from an acetic acid buffer solution. These micelles consisted of the hydrophobic AP block cores with the surface covered by soft and freely stretched CS chains. Self-assembling is highly interesting since enables the use of polymers in delivery applications. Moreover, AP, which has no bioproperties, becomes by self-assembly covered with a natural biomaterial. In this way, it was claimed that the biocompatibility of the polymer can be improved and may give also a change to remove the undegradable oligoaniline from the body. PC12 cells on these samples containing AP showed neurite extension and even were able to form intricate networks, being the best effect observed with samples containing 4.9 wt % of AP.

Figure 14.

Chemical structure of aniline pentamer cross-linking chitosan (AP-cs-CS) (left) and scanning micrographs (right) showing nanomicelles of AP-cs-CS and the typical morphology of CS. Reprinted with permission from [49]. Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society.

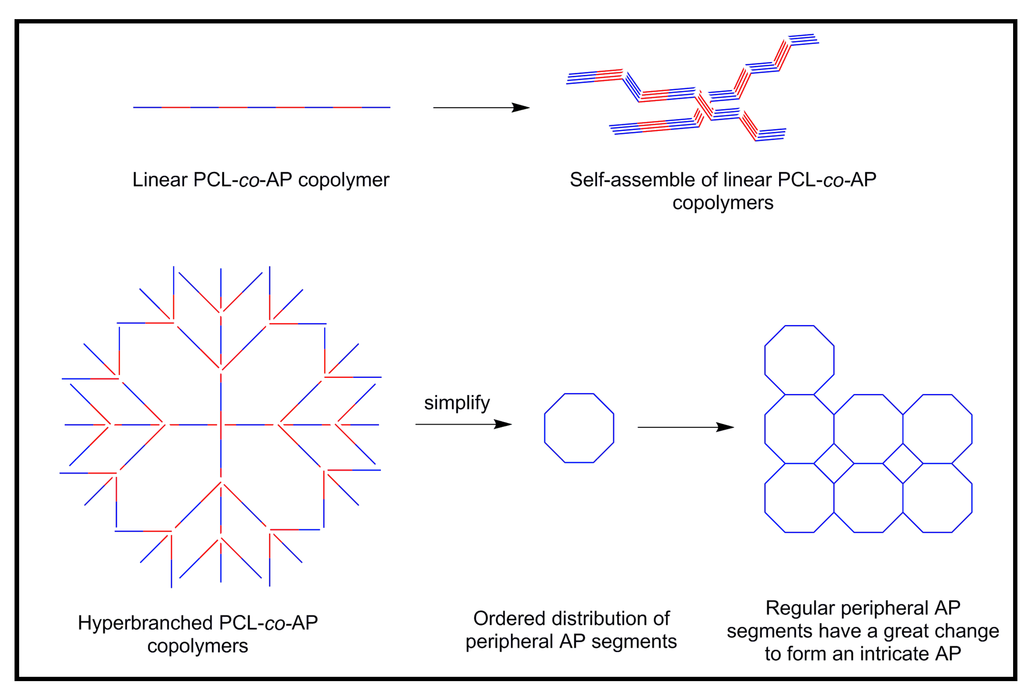

Linear and hyperbranched copolymers with electrical conductivity and biodegradability were also synthesized using a carboxyl-capped aniline pentamer and branched polycaprolactones by coupling reactions [50]. Copolymers were electroactive and showed three pairs of redox peaks. The hyperbranched copolymers had a higher conductivity than the linear ones, probably as a consequence of the ordered distribution of peripheral AP segments that more easily form a conductive network (Figure 15). In this way, it is clear that the conductivity of polymers could be improved and controlled by the macromolecular architecture.

Figure 15.

Model explaining the higher conductivity of hyperbranched copolymers than the linear ones with the same content of conductive units.

So far these hyperbranched degradable conducting copolymers have been blended with polycaprolactone to construct electroactive tubular porous nerve conduits by a solution-casting/particle-leaching method [51]. Thermal and mechanical properties, hydrophilicity, morphology, toxicity and conductivity (values between 3.4 × 10−6 and 3.1 × 10−7 S/cm were found depending on the composition) were determined for blends doped with (±)-10-camphorsulfonic acid. The results obtained supported their potential in neural tissue engineering applications.

4.2. Biodegradable Scaffolds Constituted by Nanofibers of Polyaniline

Composite materials are currently utilized as a temporary substrate to stimulate tissue formation by controlled electrochemical signals as well as continuous mechanical stimulation until the regeneration processes are completed.

First works providing novel conductive material well suited as biocompatible scaffolds for tissue engineering concern the development of PANi-gelatin blend nanofibers [52]. Both compounds were dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol and co-electrospun into nanofibers. SEM analysis of the blend fibers containing less than 3 wt % of PANi revealed uniform fibers with no evidence for phase segregation and with a substantial change on the physicochemical properties of gelatin. The average diameter size of fibers decreased from ~800 to ~60 nm by increasing the amount of PANi (from 0 to ~5 wt %) while the tensile modulus increased from ~500 to ~1400 MPa. PANi-gelatin blend fibers supported H9c2 rat cardiac myoblast cell attachment and proliferation to a similar degree as positive controls (i.e., tissue culture-treated plastic).

Picciani et al. [53] considered the use of poly(l-lactide) as the support polymeric matrix for the preparation of PANi-based conducting nanofibers and evaluated the influence of some operational parameters, such as the polymer concentration, applied voltage, and flow rate, on the morphology of electrospun fibers. Thus, ultrafine fibers (i.e., diameters ranging between 100 and 200 nm) consisting of blends of polyaniline doped with p-toluene sulfonic acid and PLA were prepared by electrospinning. The high interaction between both components and the rapid evaporation of the solvent during electrospinning resulted in nanofibers with a lower degree of crystallinity in comparison with cast films. The electrical conductivity of the electrospun fiber mats was also reported to be lower probably as a consequence of their lower crystallinity and the high porosity of the nonwoven mats.

Several polyaniline and poly(d,l-lactide) (PANi/PDLA) mixtures at different weight percentages were successfully electrospunned from 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol solutions and their conductivity and biocompatibility evaluated [54]. Promising results were only attained when the PANi content reached 25%. Specifically, this scaffold was able to conduct a current of 5 mA and had an electrical conductivity of 0.0437 S/cm. Calorimetric analysis indicated that fibers were a mixture of the two involved polymers rather than a blend as the Tg value was close to the Tg of PDLA alone. Primary rat muscle cells were able to attach and proliferate over all the new scaffolds although they degraded during the process. The polymer degradation and shrinkage may prevent the blend from being used as the primary component of a biomedical device, but it was claimed its usefulness as a biocompatible coating on devices such as sensors [54].

Composites from the blending of conductive (CPs) and biocompatible polymers are powerfully emerging as a successful strategy for the regeneration of myocardium due to their unique conductive and biological recognition properties able to assure a more efficient electroactive stimulation of cells.

Composite substrates made of synthesized polyaniline (sPANi) doped with camphorsulfonic acid and polycaprolactone (PCL) electrospun fibers were investigated as platforms for cardiac tissue regeneration [55]. In particular, conductibility tests indicated that sPANi short fibres provided a highly efficient transfer of electric signal due to the spatial organization of the electroactive needle-like phases up to form a percolative network. On the basis of this characterization, sPANi/PCL electrospun membranes have been optimized to mimic either the morphological and functional features of the cardiac muscle extracellular matrix. Biological assays (i.e., evaluation of cell survival rate and immunostaining of sarcomeric α-actinin of cardiomyocites-like cells) indicated that conductive signals offered by PANi needles, promoted the cardiogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into cardiomyocite-like cells. These preliminary results demonstrated that the development of electroactive biodegradable substrates opens the way towards a new generation of synthetic patches for the support of the regeneration of damaged myocardium.

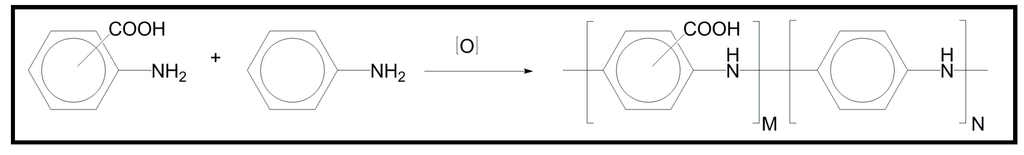

The insolubility of PANI, in most common solvents can be circumvented by copolymerizing aniline with substituted anilines that impart solubility to the resulting functionalized PANI copolymers (fPANIs). Copolymerization of aniline with aminobenzoic acids (ABAs) gives copolymers (Figure 16) that are soluble in basic aqueous media, and in polar solvents [e.g., N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] and consequently conducting samples that can be easily electrospun.

Figure 16.

Chemical structure of copolymers constituted by anyline and aminobenzoic units.

Nanofibrous blends of HCl-doped poly(aniline-co-3-aminobenzoic acid) (3ABAPANI) copolymer and poly(lactic acid) (PLA) were fabricated by electrospinning solutions of the polymers, in varying relative proportions, in a dimethyl sulfoxide/tetrahydrofuran mixture [56]. The conducting copolymer was synthesized from a comonomer mixture with equimolar proportions of aniline and 3ABA, using potassium iodate as oxidizing agent and hydrochloric acid. The nanofibrous electrospun 3ABAPANI-PLA blends gave enhanced cell growth (assayed with COS-1 fibroblast cells), potent antimicrobial capability against Staphylococcus aureus and electrical conductivity (e.g., 8.1 mS/cm was determined for the sample with 55 wt % of PLA). This new class of nanofibrous blends can potentially be employed as tissue engineering scaffolds, and in particular are promising as the basis of a new generation of functional wound dressings that may eliminate deficiencies of currently available antimicrobial dressings.

Combination of temperature responsive-conducting polymers together with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) has been revealed as an excellent smart matrix with outstanding cell viability and proliferation. Specifically, electrospun microfabric scaffolds of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)–CNT–polyaniline were studied [57]. The polymer was synthesized by coupling chemistry using polyaniline, HOOC-MWNT, and amine-terminated poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) and electrospun from 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol and N,N-dimethylformamide (8:2, v/v) solvent mixture. New scaffolds supported an excellent cell proliferation and viability that was attributed to the balanced hydrophilic functions, conductance, and mechanical strength provided by the poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), polyaniline, and MWNTs, respectively. Furthermore, a temperature dependent cells detachment behavior was observed by varying incubation at below lower critical solution temperature of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). Suitable three-dimensional conducting smart tissue scaffolds were also reported when poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-methacrylic acid) was employed as temperature responsive polymer component [58].

5. Conducting and Biodegradable Systems Related with Polypyrrole

Polypyrrole is one of the most widely investigated conductive polymers because of the aqueous solubility of the monomer, the low oxidation potential and the high conductivity. Furthermore, the easy synthesis and long-term ambient stability enhances its interest for many industrial applications (e.g., antistatic, electromagnetic shielding, actuators and polymer batteries) despite some uses may be limited by the inherently poor solubility in common solvents [59]. In its oxidized form, polypyrrole is a polycation with delocalized positive charges along its highly conjugated backbone. Charge neutrality is achieved by the incorporation of negatively charged ions termed “dopants”.

The interest of PPy for biomedical applications has been highlighted by Langer et al. [60] who showed that the electrical stimulation from the application of an external electrical field through a PPy film could significantly improve neurite extension from cultured neurons in vitro.

Polypyrrole can support in vitro attachment and differentiation of neuronal cell lines and primary nerve cell explants (e.g., PC12 cells). In addition, these neuronal-like cells extended longer neurites on PPy films compared to FDA approved polymers such as PLA and PLGA. Beneficial effects from PPy have also been demonstrated in animal implantation studies where PPy provoked little adverse tissue response compared to the PLGA and enhanced baseline nerve regeneration across gaps within silicone chambers.

5.1. Development of Novel Biodegradable Polymes and Blends Based on Pyrrole Units

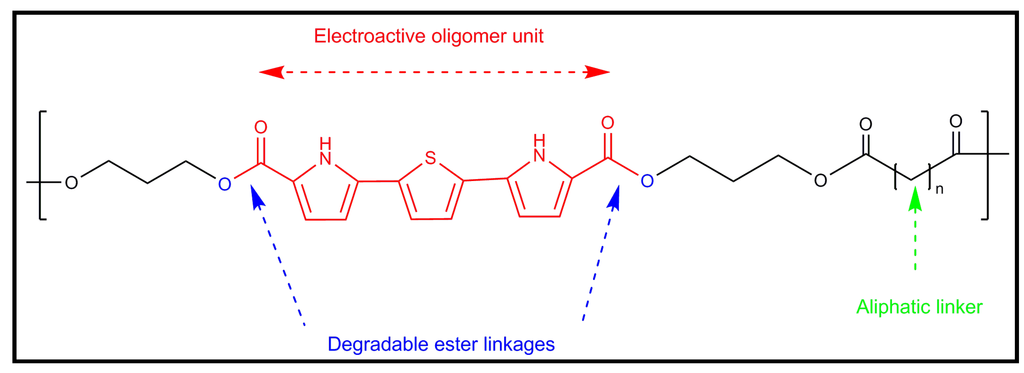

Although PPy is considered non-biodegradable and might remain in tissue for a relatively long period of time, its structure could be modified to make the polymer biodegradable [61]. Thus, a novel biodegradable conducting polymer, which combines mixed heteroaromatic conductive segments of pyrrole and thiophene with flexible aliphatic chains via degradable ester linkages, has recently been developed for biomedical applications (Figure 17). Specifically, its utility for peripheral nerve regeneration as well as spinal cord regeneration, wound healing bone repair and muscle tissue stimulation have been claimed [61,62].

Figure 17.

Scheme illustrating the key components of a novel biodegradable conducting polymer: conducting pyrrole-thiophene-pyrrole oligomer, degradable ester linkages and aliphatic linker.

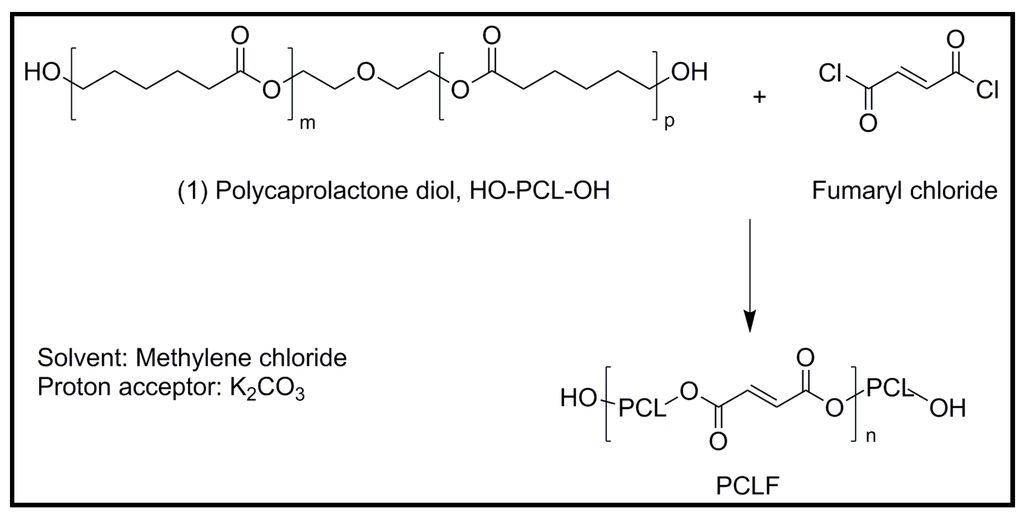

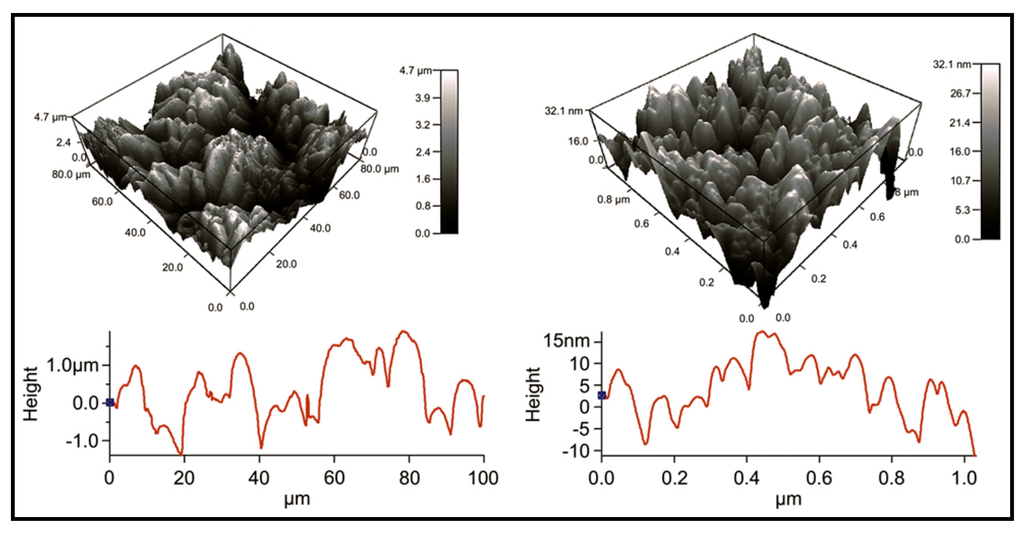

Electrically conductive polymer composites (PCLF-PPy) composed of polycaprolactone fumarate [63] (PCLF) and polypyrrole have been developed for nerve regeneration applications [64]. PCLF is a derivative of polycaprolactone (Figure 18) that can be easily processed into complex three-dimensional structures and exhibits biocompatibility, good mechanical properties, and tunable degradation rates that make it a promising base material for application as nerve guidance conduits [65]. PCLF-PPy interpenetrating networks were synthesized by polymerizing pyrrole in pre-formed PCLF scaffolds (Mn 7000 or 18,000 g/mol). PCLF-PPy composite materials had variable electrical conductivity up to 6 mS/cm with PPy bulk content ranging from 5 to 13.5 wt %. AFM and scanning electron microscope (SEM) characterization showed microstructures with a root mean squared (RMS) roughness of 1195 nm and nanostructures with RMS roughness of 8 nm (Figure 19). In vitro studies using PC12 neuronal-like cells and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) explants demonstrated that PCLF-PPy materials synthesized with naphthalene-2-sulfonic acid sodium salt or dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid sodium salt supported cell attachment, proliferation, neurite extension, and were promising materials for future studies involving electrical stimulation.

Figure 18.

Chemical structure and synthesis of polycaprolactone fumarate (PCLF).

Figure 19.

AFM micrographs of PCLF-PPy (PCLT molecular weight of 18,000 g∙mol−1) surface microstructure (left) with root mean squared (RMS) roughness of 1195 nm and nanostructure with an RMS roughness of 8 nm (right). Reprinted with permission from [64]. Copyright 2010 Elsevier Ltd.

Two novel biodegradable block copolymers of PPy with PCL and poly(ethyl cyanoacrylate) (PECA) were evaluated for nerve regeneration applications [66]. PPy-PCL and PPy-PECA copolymers showed essentially the same or greater conductivity (32 S/cm for PPy-PCL, 19 S/cm for PPy-PECA) compared to the PPy homopolymer (22 S/cm). The new conducting degradable biomaterials had good biocompatibility and support proliferation and growth of PC12 neuronal-like cells in vitro (with and without electrical stimulation) and neurons in vivo (without electrical stimulation).

Conducting polymers have stimulated the development of many biosensors for in vivo applications, including all-polymer integrated electronic circuits [67]. As general requirements the biomedical sensor implanted in the body should be biocompatible, passive, and wireless. A full biodegradability is also of great interest since avoids the need for an operation to remove the device after use and logically improves the patient's comfort and reduces the infection risks. Due to the difficulty of biodegradable PPy-based copolymers to maintain enough conductivity for electrical applications, composites made of a biodegradable polymer matrix and PPy conducting nanoparticles become a highly interesting approach. Thus composites based on PDLLA [68,69], PDLLA/GA [69], PDLLA/CL [70], PLLA [71,72] and PCL [71,72] matrices and PPy nanoparticles have been developed. Addition of a small percentage of PPy nanoparticles had no effect on the in vivo degradation behaviour of the biodegradable materials [68,69] and consequently a low enough concentration of PPy nanoparticles should not give an inflammatory response when the composite degrades, and the remaining PPy nanoparticles should be later evacuated by the body, in a similar process as described for the implanted biodegradable stents made of biodegradable metals.

Transformation of PPy into a mechanically manageable and processable form suitable for biomedical applications appears interesting in order to overcome the processability problems associated to PPy when it is used alone as structural material. Thus, a novel electrically conductive biodegradable composite material made of PPy nanoparticles and poly(d,l-lactide) (PDLLA) was prepared by emulsion polymerization of pyrrole in a PDLLA solution, followed by precipitation [68]. The advantages of chemical polymerization include the flexibility to combine with other polymers to form composites with various desired properties, the processability of the formed composite, and the large-scale low-cost production.

It was found that PPy particles formed aggregations and constituted microdomains and networks embedded in the PDLLA matrix that allowed getting conductive PPy/PDLLA composites with a very low PPy content. Thus, resistivity of composite samples exhibited typical percolation behavior, with a threshold at a PPy content of approximately 3 wt % and the surface resistivity varied from 2 × 107 to 15 Ω/square when the wt % of PPy increased from 1 to 17. It is well known that PPy underwent dedoping and deprotonation under the synergic action of water and current [69], and hence the exposure of samples to a physiological environment can eventually decrease the electrical conductivity. Interestingly, the electrical stability under a physiological environment (Eagle’s minimum essential medium) was significantly better in the PPy/PDLLA composite than in PPy-coated polyester fabrics (i.e., membranes having 5 wt % of PPy retained 80% and 42% of the initial conductivity in 100 and 400 h, respectively, compared to 5% and 0.1% for the PPy-coated polyester fabrics). In fact, under 100 mV, a biologically meaningful electrical conductivity could be sustained in a typical cell culture environment for 1000 h. Cellular activities were affected by the current applied through the conductive composite and specifically the growth of fibroblasts was up regulated under the electric stimulation.

From a general point of view, the contact between conducting polymers and metals is crucial to the integration of polymeric materials as conductors into electronic devices. The junction between PPy and metal electrodes or semiconducting materials may be problematic due to different factors (i.e., PPy polymerization conditions, layer thickness, and dopant used). In this sense, the junctions between newly developed biodegradable conducting polymers (PLLA-PPy and PCL-PPy) and metal electrodes (Au, Au/Cu, Ag, Ag/Cu, Cu, Cr/Au/Cu, Pd/Au/Cu, Pt/Au/Cu) were studied in order to determine the composite/metal combination having the lowest possible contact resistance and ohmic characteristics [71]. Furthermore, different surface treatments, adhesion and metal layers were tested in order to evaluate the contact resistance. Best results were attained with Pt/Au/Cu and Au/Cu electrodes for PLLA-PPy and PCL-PPy composites, respectively.

5.2. Biodegradable Scaffolds Constituted by Nanofibers that Incorporated Polypyrrole

Scaffold topographical features (i.e., fiber diameter and orientation) play an important role that affects the cellular behavior and merits great attention [73,74]. For example, Yang et al. [75] found that immortalized neural stem cells cultured on aligned polylactide nanofibers extended longer neurites than cells on random nanofibers and aligned microfibers of the same composition. Influence of morphology has also been considered in the study of materials for nerve regeneration based on electroconducting nanofibers.

Two different approaches have been applied to construct biodegradable nanofiber mats based on conductive polypyrrole: (a) By direct electrospinning of the conducting polymer and (b) By coating an electrospun mat of a well-known biocompatible and reabsorbable biomaterial with polypyrrole.

Scarce works concerns the electrospinning of polypyrrole alone or in mixtures with a carrier. Thus, electrospinning of polypyrrole was firstly achieved using chloroform soluble samples chemically synthesized using ammonium persulfate (APS) as the oxidant and dodecylbenzene sulfonic acid (DBSA) as the dopant source [76]. The PPy fibers exhibited circular cross-section, smooth surface and diameters about 3 µm. The electrical conductivity of the compressed PPy nonwoven web was about 0.5 S/cm, which was slightly higher than those of powder or cast films, possibly because of molecular orientation induced during the electrospinning.

Polypyrrole conductive nanofibers (70–300 nm) were firstly obtained by electrospinning organic solvent soluble polypyrrole [prepared using the functional doping agent di(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate sodium salt] or aqueous solutions using polyethylene oxide (PEO) as the carrier [77]. Nanofibers were obtained by both procedures with a well-defined morphology and physical stability. It appeared that the addition of PPy to the PEO solution has effect on the diameter of the electrospun fiber and specifically increased with increasing PPy concentration. Moreover, the electrical conductivity increased with PPy probably as a consequence of contacts established between conducting polymer regions which remained “less isolated” from non-conducting regions, and facilitated electrical conduction. It is worth to mention that pure (without carrier) PPy nanofibers with an extremely small average diameter of approximately 70 nm were formed using dimethylformamide solutions.

Cardiac tissue engineering is one of the most promising strategies to reconstruct infarct myocardium. One of the major challenges is to generate a bioactive substrate with suitable chemical, biological, and conductive properties that could mimick the extracellular matrix both structurally and functionally. Scaffolds constituted by polypyrrole/polycaprolactone (PCL)/gelatin nanofibers were obtained by electrospinning different concentrations of PPy to PCL/gelatin solution [78]. It was found that by increasing the concentration of PPy (0–30%) in the composite, the average fiber diameters reduced from 239 to 191 nm, and the tensile modulus increased from 7.9 to 50.3 MPa. Conductive nanofibers containing 15% PPy exhibited the most balanced properties of conductivity, mechanical properties, and biodegradability, matching the requirements for regeneration of cardiac tissue. Furthermore, the scaffold promoted cell attachment, proliferation, interaction, and expression of cardiac-specific proteins.

PPy deposition on fiber templates constitutes nowadays a simple method for producing conducting nanofibers [79,80]. This deposition can be achieved by in situ chemical oxidation of PPy in a polymerizing solution or by oxidation of monomers deposited on the substrates in vapor phase followed by oxidant treatment.

Scaffolds comprised of conductive core-sheath nanofibers have been prepared via in situ polymerization of pyrrole on electrospun PCL or PLA nanofibers [81]. Since PPy constitutes a thin coating on biodegradable nanofibers, the amount of PPy contained in a nerve conduit could be substantially reduced for in vivo applications. The in situ polymerization reaction for PPy involved in this case the use of Fe3+ as an oxidant and Cl− as a dopant. The PPy nanotubes had an outer diameter and a wall thickness of around 300–320 and 50 nm, respectively. PPy sheath deposited on the PCL nanofiber was much smoother than that on the PLA nanofiber, probably as a consequence of their different molecular structures. The extra methyl group on the side chain of PLA might make the surface of this polymer less wettable by PPy monomer than the surface of PCL. When explanted dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were cultured on the core-sheath nanofibers, the neurite extension could be uniaxially aligned and enhanced by 1.82-fold on uniaxially aligned nanofibers as compared with scaffolds consisting of random fibers. Furthermore, the maximum length of neurites could be increased by 1.83- and 1.47-fold on the random and aligned nanofibers, respectively, when an electrical stimulation was applied. The synergistic effect of topographic cue and electrical stimulation on axonal regeneration from cultured neuronal populations was probed and could consequently provide potential applications in neural tissue engineering.

Nano-thick PPy was also deposited onto PLGA nanofibers having random or oriented dispositions in order to evaluate the contact guidance (i.e., neurite/axon alignment) [82]. Two different types of neurons (i.e., PC12 neuronal-like cells and rat embryonic hippocampal neurons) were considered for in vitro studies, which demonstrated that compatible cellular interactions on the fabricated PPy-PLGA meshes were appropriate for neuronal applications and present topographies for modulating cellular interactions comparable to the PLGA control nanofibers. Furthermore, electrical stimulation of PC12 cells on the conducting nanofiber scaffolds improved neurite outgrowth compared to non-stimulated cells. In addition, further increases in neurite length and percentage of neurite-bearing cells were observed with electrical stimulation on aligned conducting nanofibers.

PPy has also been incorporated to electrospun polycaprolactone nanofibers by in situ polymerization via oxidization with ferric chloride from PCL/chloroform solutions containing Py [83]. PPy nanoparticles were effectively attached on the electrospun fiber surfaces, as deduced from the spectroscopic data, and influenced on the fiber morphology and final mechanical properties. Thus, the fiber diameter decreased gradually from 730 to 325 nm and showed narrower distribution with increasing the PPy content (from 0 to 20 wt %). The tensile modulus and tensile strength increased (i.e., from 25.7 and 2.48 MPa to 129 and 86.2 MPa, respectively) with PPy content whereas the elongation at break declined (i.e., from 120% to 86.2%).

Silk fibroin (SF) nanofiber-based scaffolds prepared by electrospinning have been extensively studied for their wide applications in biomedicine (e.g., tissue engineering in blood vessels, skin, bone and cartilage) [84]. SF is highly biocompatible and able to support appropriate cellular activity without eliciting rejection, inflammation or immune activation in the host [85]. Fibers of fibroin meshes have also been coated with PPy by chemical polymerization. Chemical linkages between both polymers were established as deduced by SEM and infrared spectroscopy (IR) [86]. Mechanical resistance of the meshes was clearly improved by the polypyrrole coating. Furthermore, coated meshes had better mechanical resistance than uncoated samples and presented a high electroactivity allowing anion storage and delivery during oxidation/reduction reactions in aqueous solutions. New materials were demonstrated also to support the adherence and proliferation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells (ahMSCs) or human fibroblasts (hFb).

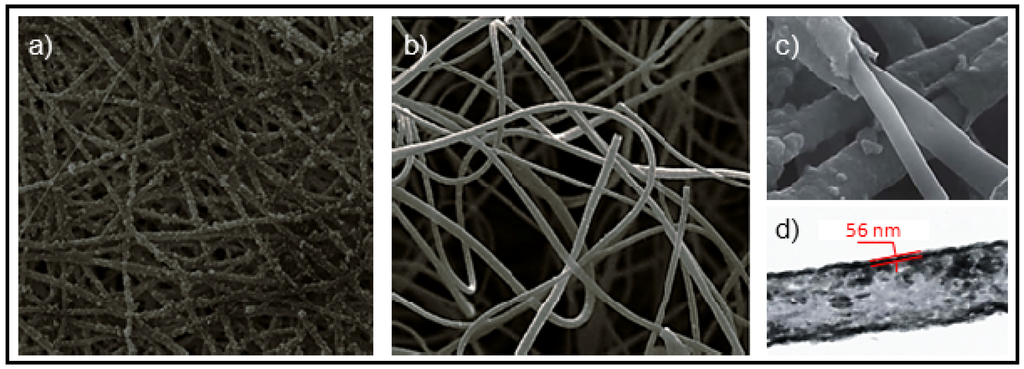

A novel fluffy-PPy scaffold, which was composed of discrete hollow PPy fibers with interconnected pores of ~100 µm, has recently been developed to support 3D cell culture in vitro [87]. Cardiomyocytes as model cells, were cultured in the fluffy-PPy scaffolds, being observed that they could enter into the interior of the scaffold smoothly with no extra help to achieve the 3D cell culture and formed integrated cell-fiber constructs after only three days in culture. Cell proliferation was found to be higher than that cultured on traditional electrospun mesh-PPy scaffolds and even on tissue culture plates. Results are meaningful since demonstrate that the 3D cell culture in fluffy fibrous scaffolds could improve cells’ survival in vitro compared to traditional 2D cell culture on electrospun fibrous meshes. The final scaffold was obtained by in situ surface polymerization of pyrrole with FeCl3 over a fluffy-PLLA scaffold (Figure 20). This was prepared by electrospinning using a special collector, which was crafted by embedding an array of stainless steel probes in a hemispherical plastic dish covered with aluminum foil.

Figure 20.

SEM micrographs of (a) mesh-PPy scaffold; (b) Novel fluffy-PPy scaffold; (c) PPy coated PLLA fibers; and (d) TEM image of a PPy hollow fiber. Reprinted with permission from [87]. Copyright 2012 Royal Society of Chemistry.

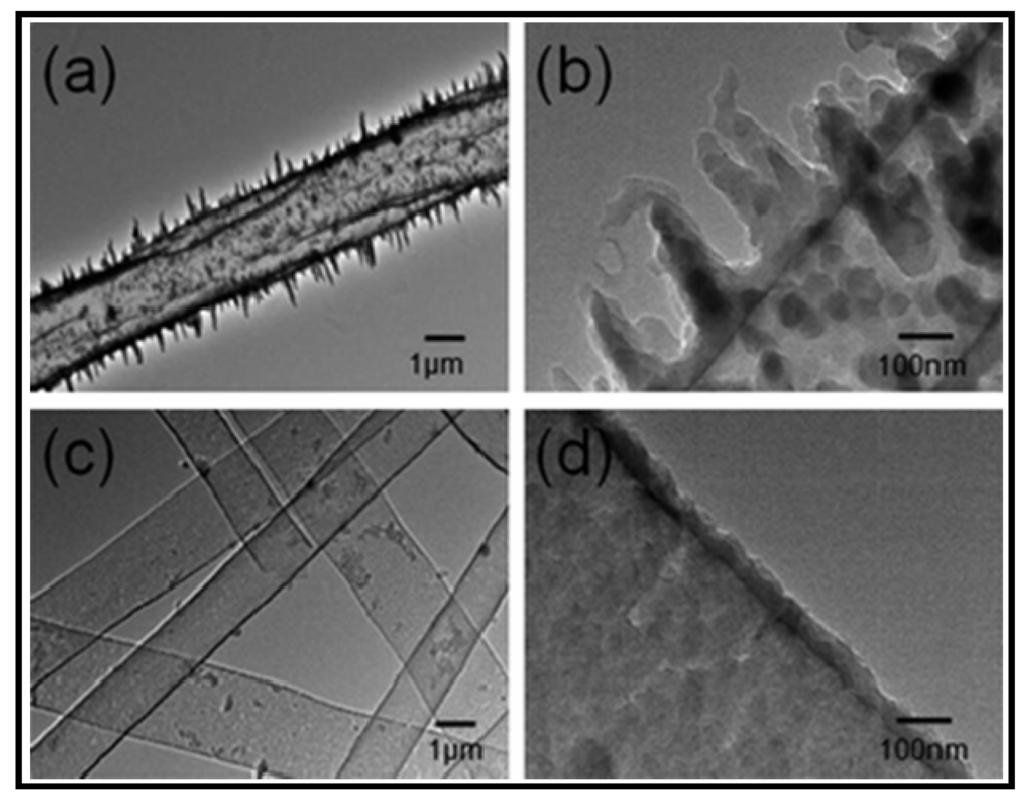

Conductive polymers have also attracted great interest for the extraction of polar compounds since they have several advantages: a high extraction efficiency for these compounds caused by their inherent and unusual multifunctionality (e.g., ion-exchange properties, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, acid-base properties, polar functional groups, and electroactivity) [88,89], and their switchable ion-exchange behavior [90]. A solid-phase extraction method based on conductive PPy hollow fibers, which were fabricated by electrospinning and in situ polymerization over electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) fibers, has been developed [76]. Polymerization was conducted in aqueous solution under different agitation conditions (i.e., mechanical stirring and ultrasonication) for shaping different surface morphology of PPy hollow fibers (Figure 21). The nanostructure of the PPy grains and the hollow internal structure provided a high surface area that allowed for improved adsorption capacity. Two important neuroendocrine markers of behavioral disorders, 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid and homovanillic acid, were successfully extracted with a recovery of 90.7% and 92.4%, respectively, in human plasma. Analysis of these neuroendocrine markers by conventional techniques is difficult because of their tendency to decompose and the fact that the complex biological matrix in which they are present has had to be cleaned up. Due to its simplicity, selectivity and sensitivity, the method seems useful to quantitatively analyze the concentrations of polar species in complex matrix samples.

Figure 21.

TEM images of (a,b) burr-shaped PPy hollow fibers polymerized under mechanical stirring and (c,d) PPy hollow fibers polymerized under ultrasonication. Reprinted with permission from [76]. Copyright 2012 Royal Society of Chemistry.

5.3. Biodegradable Nanomembranes that Incorporated Conducting Polypyrrole

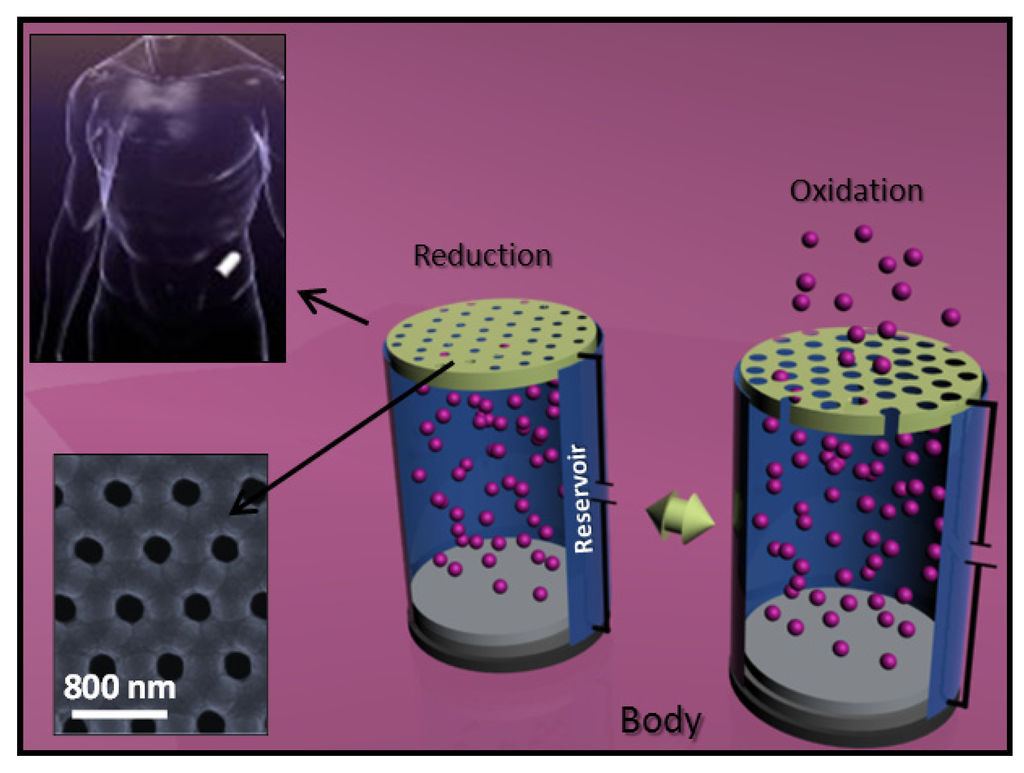

Pulsatile release of drugs based on electric stimulus for an extended period can be achieved by using nanoporous membranes with uniform pore sizes [91]. This pore size could be actuable with an electrical signal when the nanoporous membrane is made of an electrically responsive polymer. Based on this idea Kim et al. [92] constructed a nanoporous membrane by the electropolymerization of PPy doped with dodecylbenzenesulfonate onto the top and upper side wall of an anodized aluminium oxide (AAO) membrane. PPy/DBS was chosen as the electrically responsive material since it exhibits a very large volume change (up to 35 vol %) depending on the electrochemical state [93,94] and have also an excellent biocompatibility [95]. The actuation of the pore size was successfully realized by changing the electrochemical state (a driving potential of only 1.1 V was required): the pore size decreased at the reduction state while it increased at the oxidation state (Figure 22). Pulsatile drug release was successfully demonstrated using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled bovine serum albumin as a model protein drug. This device could be used for intermittent and fast administered drug delivery (i.e., new therapeutic methods of hormone related diseases such as infertility, dwarfism, osteoporosis and diabetes, as well as chronic diseases such as insomnia, angina pectoris, asthma and pain control). The use of a biodegradable polymer seems the next goal since surgery for removing the implant could be in this way avoided.

Figure 22.

Implant constituted by electrically actuable nanoporous membranes (based on [92]): nanoporous are closed at the reduction state due to PPy expansion whereas are open at the oxidation state making feasible the drug release.

A self-powered drug delivery system based on cellulose–polypyrrole composite film was also developed. The composite film was prepared by electrochemical deposition of drug-contained PPy film on the inner and outer surfaces of a porous cellulose film. The formed PPy film maintained the porous structure of cellulose and consequently possessed high specific surface area, which is very important to achieve high drug release efficiency. Furthermore, a conductivity of 1.58 mS/cm was measured. After coating the composite film by a thin layer (100–500 nm) of an active metal such as magnesium, the drug stored in the PPy film could be released autonomously upon exposure to an electrolyte solution, following the galvanic cell mechanism. The amount of the drug released [i.e., adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was assayed as a model drug] and the release rate were effectively controlled by adjusting the thickness and type of the active metal, respectively. Since the cellulose film is biodegradable and the system obtained was flexible and lightweight, it was therefore expected that this drug delivery system could find in vivo applications [96].

The incorporation of a negatively charged dopant molecules to PPy can be exploited to tailor its properties to a specific application. Thus, thin films pf PPy were prepared using hyaluronic acid (HA) as dopant and the cell and tissue responses evaluated [97]. HA is an extremely long, negatively charged, heavily hydrated glycosaminoglycan that is found in almost all extracellular tissue spaces in the body and that has a beneficial role in wound healing: Furthermore, it is involved in a number of complex cell signalling events including migration, attachment, and neuronal sprouting [98]. PPy/HA single-layer films (thickness between 0.15 and 2 µm) were electrochemically synthesized in an aqueous solution of 0.1 M pyrrole and 2 mg/mL HA (5 mM in carboxylate ions).

PPy/HA single-layer films polymerized slowly, had suppressed conductivity, had rough nodular surfaces, and were brittle and difficult to handle. To produce conductive, smooth films, PPy/HA bilayer films were synthesized with an underlying layer of PPy doped with poly(styrenesulfonate). These bilayer films were smooth, had good conductivity (8.02 S/cm), displayed HA on their surfaces and were not cytotoxic since supported PC12 cultures (as an example of a neuron-like cell line).

Different protein-rich PPy materials were prepared by water-in-oil emulsion polymerization of pyrrole in presence of either fibronectin (FN) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) [99]. The first compound is a cell-adhesive glycoprotein that is involved in multiple biological phenomena including cell adhesion and maintenance of normal cell morphology, cell migration, homeostasis and thrombosis, wound healing and oncogenic transformation, and the protection against programmed cell death or apoptosis. On the contrary, the second is a soft protein capable to inhibit cell attachment and to block nonspecific binding. In this way, these novel bioactivated PPy particles may be useful in tissue engineering to fabricate conducting biodegradable scaffolds with either improved or reduced cell adhesion properties for various cell culture and in vivo applications. Both the pure and protein-rich PPy showed a similar microporous morphology apparently made by the assembly of PPy rod-like nanoparticles (diameter ~100 nm). Proteins became entangled with the PPy macromolecules during emulsion polymerization and furthermore the negatively charged proteins and positively charged PPy were able to interact leading to the in situ doping of PPy by the proteins. The conductivity of all of the PPy particles measured in the (1–2) × 10−1 S/cm range. The lower values corresponded to particles that incorporated proteins. This slight decrease on the conductivity was more evident in the FN than in the BSA samples. In addition, this decreased conductivity was apparently dose-dependent for FN but not for BSA. It was also able to prepare conductive biodegradable membranes by addition of PPy particles to a PLA solution in CHCl3.

The fabrication of polymer structures with controlled dimensions is critical to the development of advanced platforms for cell culturing and tissue engineering. The nature of the tissue to be repaired or engineered and the potential of the polymer structure to promote appropriate growth of cells are some major concerns that should be taken into account. Muscle is an appropriate tissue to develop proper function, nano- and microstructured cell culture platforms since involves a characteristic ‘‘bundled tubular’’ structure and cell systems that respond to electrical stimulation. Thus, novel biosynthetic platforms supporting ex vivo growth of partially differentiated muscle cells in an aligned linear orientation that is consistent with the structural requirements of muscle tissue have been described [100,101]. These platforms consist of biodegradable PLA/PLGA fibers spatially aligned on a PPy conducting substrate with a thickness close to 200–900 nm (Figure 23). Long multinucleated myotubes could be formed from differentiation of adherent myoblasts, which align longitudinally to the fiber axis to form linear cell-seeded biosynthetic fiber constructs. The ability to remove the muscle cell-seeded polymer fibers when required provides the means to use the biodegradable fibers as linear muscle-seeded scaffold components suitable for in vivo implantation into muscle. In addition, the conducting substrate on which the fibers are placed provided the potential to develop electrical stimulation paradigms for optimizing the ex vivo growth and synchronization of muscle cells on the biodegradable fibers prior to implantation into diseased or damaged muscle tissue.

The designed scaffold is also proposed to promote directionally controlled axonal growth and Schwann cell migration, providing the basis of a device for controlled neuro-regenerative applications in vivo. Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) explants, grown on these platforms, demonstrate axonal and Schwann cell alignment with the fibers. In addition, enhanced neurite outgrowth and Schwann cell migration was achieved after direct electrical stimulation via the conductive polymer layer [102].

Figure 23.

Formation of linear cell-seeded biosynthetic fiber constructs. (a) The two-step fabrication of the hybrid platform involved: (1) wet spinning of PLA:PLGA fibers onto a substrate to create an aligned microfiber array pattern; and (2) electrochemical deposition on the substrate of the conducting PPy; (b) The compatibility of the hybrid platform toward skeletal muscle was assessed by: (1) Proliferation and adhesion of cells and (2) Cell differentiation; and (c) The hybrid scaffold can be removed from the substrate layer and manipulated into 3D structures for in vivo implantation as required. Reprinted with permission from [100] and [102]. Copyright 2009 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. and 2011 American Chemical Society.

Cellulose paper can be considered a smart material that can be employed as sensor and actuator [103,104]. The material has clear advantages concerning lightweight, dryness, low cost, biodegradability, biocompatibility, large deformation, low actuation voltage and low power consumption. Cellulose paper can be electrically activated due to a combination of ion migration and a piezoelectric effect originated from the crystal structure of cellulose and the dipolar orientation of molecules. The performance of cellulose can be improved by coating the paper with conductive polymers such as polypyrrole (PPy) and polyaniline [105,106]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that the ion migration effect can be enhanced by nanocoating the cellulose film with polypyrrole and ionic liquids (e.g., 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetra fluroborate) [107]. This hybrid nanocomposite exhibited durable bending actuation in an ambient humidity and temperature conditions. Results appear promising for developing cellulose based paper actuators for ultralight weight devices and biomedical applications.

6. Conducting and Biodegradable Systems Related with Polythiophenes

6.1. Development of Novel Biodegradable Samples Having Thiophenes

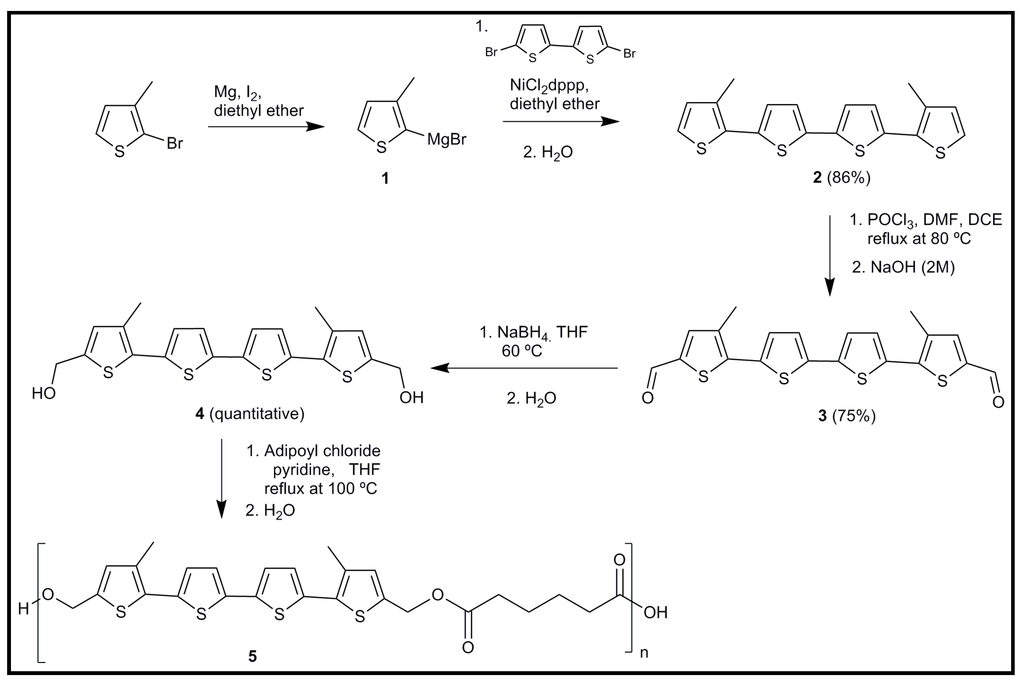

Guimard et al. [108] designed a novel biocompatible and biodegradable copolymer based on electroactive oligothiophene units (Figure 24) that overcomes some limitations of materials previously developed and based on pyrrole-thiophene-pyrrole oligomers with alternating ester linkers [61] (i.e., they could only be doped with iodine, which is toxic to cells and which resulted in a very low conductivity). The new system incorporated alternating electroactive quaterthiophene units and biodegradable ester units into one macromolecular framework. The polymer exhibited redox activity (according to cyclic voltammetry experiments) and a new red-shifted absorption peak upon doping, which provided support for the notion that the quaterthiophene units maintain electroactivity after incorporation into the polymer framework. Enzymatic degradation, through surface erosion, was confirmed as well as the short term (48 h) in vitro biocompatibility assayed with Schwann cells. Despite the promising results, it was also stated the necessity to develop new analogues that might be more readily doped, prove equally or more stable in the doped state, display higher conductivity or demonstrate improved degradation properties. These features could be achieved by using oligothiophene subunits of greater size (sexithiophene) and even different diacids.

Figure 24.

Synthesis of poly(5,5′′′-bis(hydroxymethyl)-3,3′′′-dimethyl-2,2′,5′,2′′,5′′,2′′′-quaterthiophene-co-Adipic Acid) (QAPE).

6.2. Applications of Biodegradable Constructs Based on Electrospun Nanofibers of Thiophene Derivatives

Electrochemical actuators are based on the expansion and contraction that experiments a polymer in an electrolyte solution as a consequence of the change on electronic charge [109,110,111]. This is produced by the exchange of ions being the extension and contraction effect dependent on the number and size of counterions that enter or exit the polymer [112]. CPs can be doped with bioactive drugs and used in actuators such as microfluidic pumps [113,114] that could lead to a controlled local release. For example, the treatment of the inflammatory response of neural prosthetic devices requires the release of anti-inflammatory drugs at desired points in time [115].

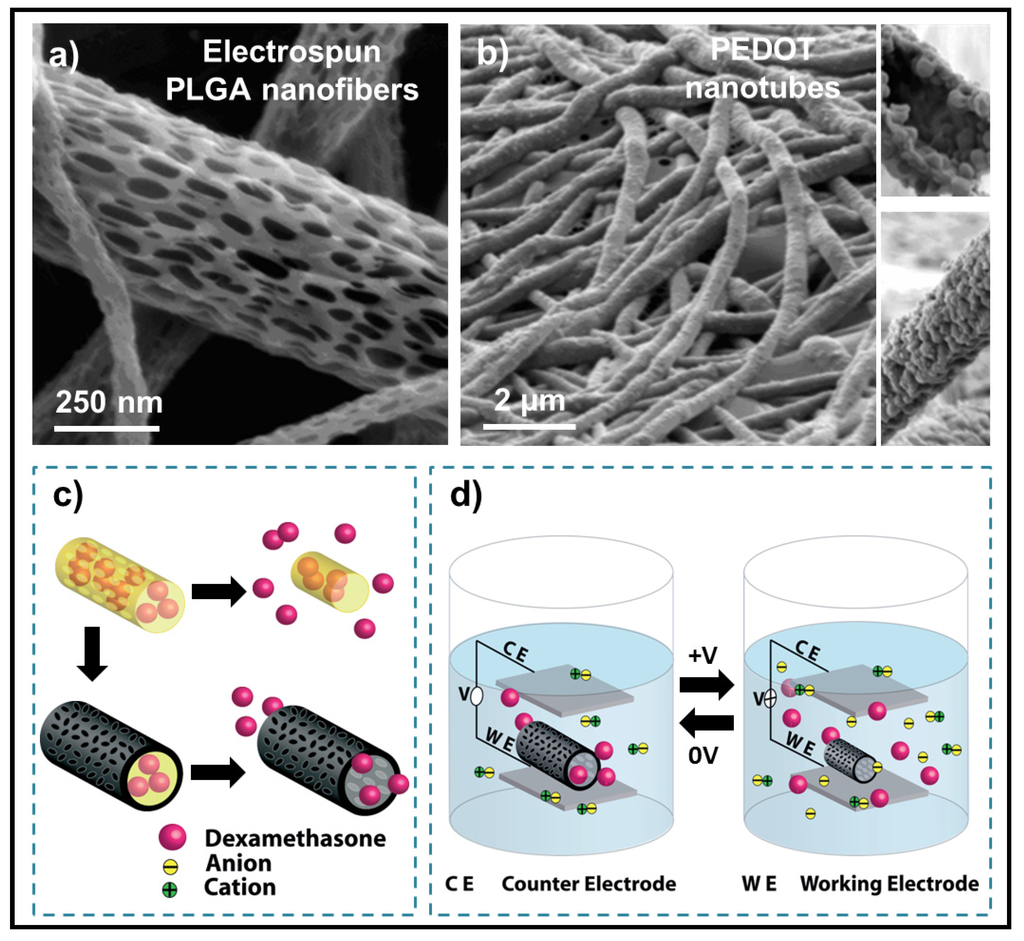

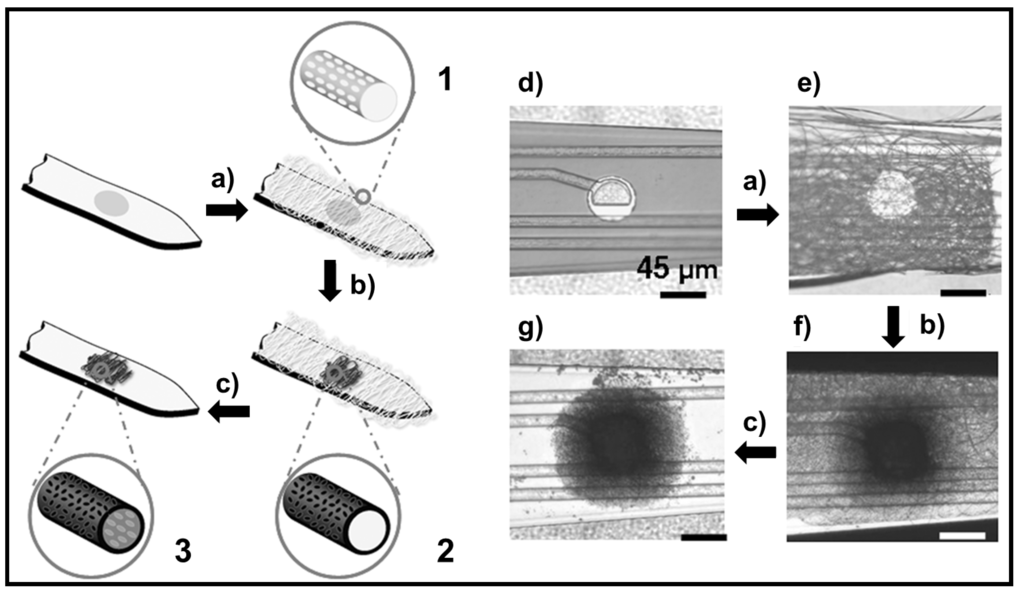

An interesting method to prepare conducting-polymer nanotubes that can be used for precisely controlled drug release has been reported by Abidian et al. [116] (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Scanning electron micrographs of (a) PLGA nanosfibers and (b) poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) nanotubes after removing the PLGA core fibers; Schematic illustrations of (c) the controlled release of dexamethasone and (d) the control of the release by applying an external electrical stimulation and positive charges in the polymer chains are compensated. To maintain overall charge neutrality, counterions are expelled towards the solution, nanotubes contract and drugs come out of the ends of tubes. Reprinted with permission from [116]. Copyright 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.

The fabrication process involved electrospinning of a biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA), into which a drug (e.g., dexamethasone) was incorporated. Subsequently, a conducting-polymer (e.g., PEDOT) was electrochemically deposited around the drug-loaded, electrospun nanofibers. The conducting-polymer nanotubes significantly decreased the impedance and increased the charge capacity of the recording electrode sites on microfabricated neural prosthetic devices. As the PLGA fibers degraded, dexamethasone molecules remained inside the PEDOT nanotubes. The drug could be released from the nanotubes in desired points in time by their electrical stimulation that promoted mass transport. Thus, during reduction of the PEDOT nanotubes, electrons were injected into the chains and positive charges in the polymer chains were compensated. To maintain overall charge neutrality, negatively charged counterions were expelled towards the solution and the nanotubes contract [112,117]. This contraction gave rise to a hydrodynamic force inside the nanotubes that caused expulsion of PLGA degradation products and dexamethasone.

The proposed method seems to provide a generally useful means for creating low impedance, biologically active polymer coatings, which should facilitate integration of electronically active devices with living tissues. Furthermore, these electrically active polymer nanotubes have other potential biomedical applications such as highly localized stimulation of neurite outgrowth and guidance for neural tissue regeneration, and spatially and temporally controlled drug delivery for ablation of specific cell populations.

Drug-delivery systems based on CPs are of immense scientific interest and give hope for the treatment of cancer and also minimum invasive techniques for several neural and cardiovascular applications. However, these systems have clear disadvantages such as a significant burst release effect and a great hydrophobic nature of polymer chains that limit applications.

Development of advanced neural interfaces may provide effective treatments for neurological conditions [118,119]. These interfaces should accomplish highly specific requirements that push towards the placement of a high density of small and biocompatible electrodes [120], which should remain functional for long period of time [121]. Nanostructured materials may reconcile the conflicting requirements for small electrode size, which is necessary to attain a high spatial selectivity, and favorable electrical characteristics, which are associated to low impedance. The PEDOT conducting polymer has been specifically revealed as an attractive material for neurological applications since shows favorable reactive tissue responses and enhanced integration and signaling of neuronal processes [122,123]. Abidian et al. [124] reported for the first time the use of PEDOT conducting nanotubes for highly selective, chronic neural recording at the microscale (Figure 26). It was demonstrated that PEDOT nanotubes enhanced quality of recording signals (i.e., electrodes modified with PEDOT registered higher signal-to-noise ratio and lower impedances than control electrodes). Tissue encapsulation of the electrode may mitigate the long-term benefit of reducing initial impedance [120] and consequently it has been proposed as an interesting strategy the control of the foreign body response to the implanted array of electrodes. PEDOT nanotubes can precisely provide a mechanism to address this issue through the controlled delivery of therapeutic agents explained above [116].

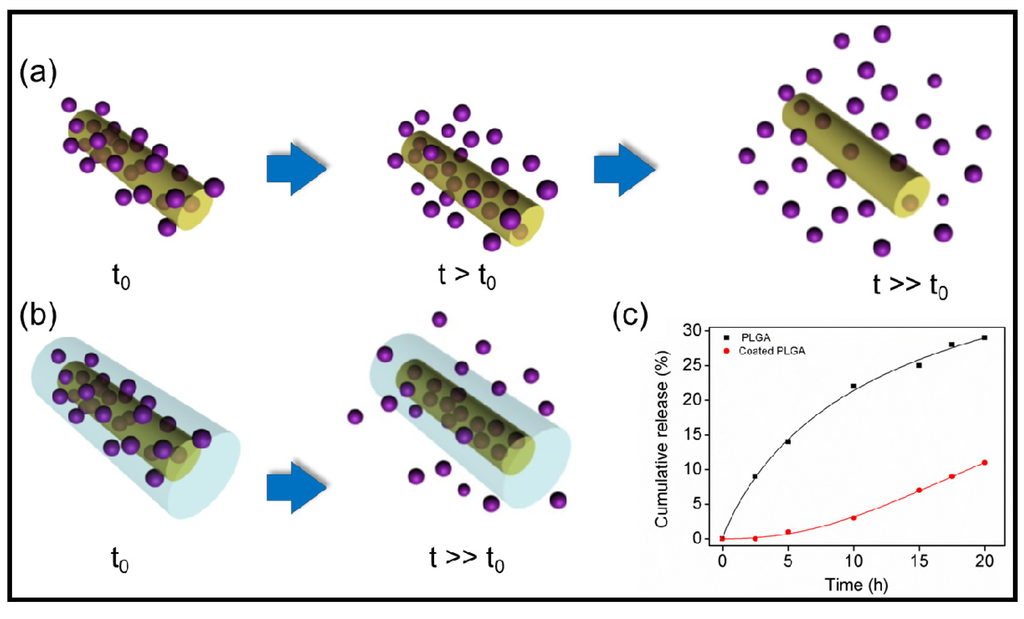

It has also been reported the fabrication of controlled releasing nanobiomaterials that can be used to stabilize the electrode/ tissue interface [125]. The fabrication process included electrospinning of anti-inflammatory drug-incorporated biodegradable nanofibers, encapsulation of these nanofibers by an alginate hydrogel layer, followed by electrochemical polymerization of a conducting polymer (i.e., PEDOT) around the electrospun drug-loaded nanofibers to form nanotubes and within the alginate hydrogel scaffold to form cloud-like nanostructures. Dexamethasone (DEX) was assayed as an example of anti-inflammatory drug while PLA and PLGA were employed as biodegradable polymers. The three-dimensional conducting polymer nanostructures were found to significantly decrease the electrode impedance and increase the charge capacity density. Specifically, after PEDOT deposition around drug loaded PLGA nanofibers and within the alginate hydrogel, the impedance at 1 kHz decreased by about two orders of magnitude from the unmodified electrode. Dexamethasone release profiles showed that the alginate hydrogel coating slowed down the release of the drug and significantly reduced the burst effect (Figure 27).

Figure 26.

Schematic illustration of conducting polymer (PEDOT) nanotube fabrication on neural microelectrodes: (a) Electrospinning of biodegradable PLGA template fibers with well-defined surface texture (1); (b) Electrochemical deposition of conducting polymer (PEDOT) around the electrospun fibers (2); (c) Dissolving the electrospun core fibers to create conducting polymer nanotubes (3); Optical microscopy images of (d) the entire microelectrode site before surface modification; The electrode site (e) after electrospinning of PLGA nanofibers; (f) After electrochemical deposition of PEDOT; and (g) After removing the PLGA core fibers. Reprinted with permission from [116]. Copyright 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.

Figure 27.

Schematic illustration showing the release of the anti-inflammatory drug from electrospun nanofibers (a) without and (b) with an alginate hydrogel coating; (c) Comparison of cumulative mass release profiles of DEX-loaded PLGA scaffolds with and without the alginate coating. Reprinted with permission from [125]. Copyright 2009 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.

6.3. Applications of Biodegradable Constructs Based on Films and Nanomembranes of Thiophene Derivatives

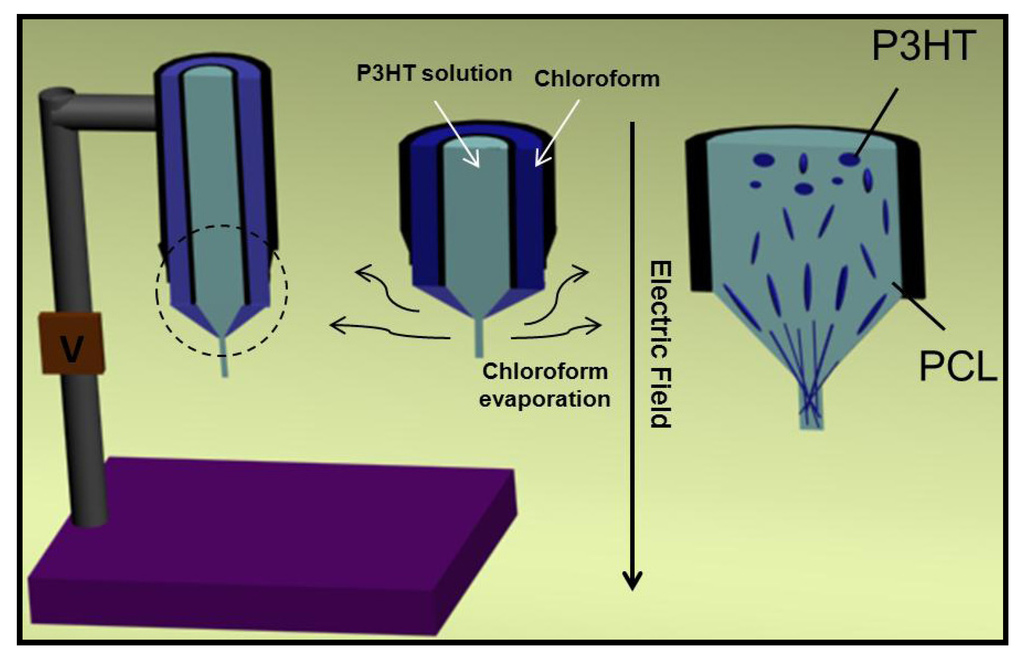

Electrospinning of semiconducting polymers have been scarcely carried out mainly because of their low solubility and fast crystallization that easily blocks the nozzle. Among the semiconducting polymers, poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) has been considered the best candidate since it has very high field effect mobilities (i.e., 0.1 cm2/V∙ s can be attained) [126]. A single nanofiber field-effect transistor (FET) made from electrospun P3HT has been reported and demonstrated that electrospinning offers a simple means of fabricating one-dimensional polymer transistors [127]. Nanofibers, with diameters of 100–500 nm, were deposited by electrospinning from chloroform solution onto electrodes on a SiO2/Si substrate. The transistor exhibited a hole field-effect mobility of 0.03 cm2/V∙s in the saturation regime, and a current on/off ratio of 103 in the accumulation mode. However, the morphology of the P3HT nanofibers was poor since they were not continuously produced and contained lots of beads along the fibers.

Jeong et al. [128] studied the way to avoid P3HT crystallization and the block of the nozzle tip in order to obtain continuous nanofibers with uniform thickness. Experiments were performed using chloroform, which is the best solvent for P3HT, and a coaxial setup (Figure 28) to continuously provide a small amount of additional solvent to the evaporating solution. This additional chloroform effectively maintained the concentration of P3HT low in the solution at the nozzle tip and consequently crystallization was late enough to allow continuous electrospinning without blocking at the nozzle tip.

Figure 28.

Schemes showing (left) the coaxial electrospinning setup for P3HT electrospinning and (right) the elongation of P3HT domains and formation of continuous P3HT fibrils from the elongation of P3HT domains in highly concentrated PCL solutions.

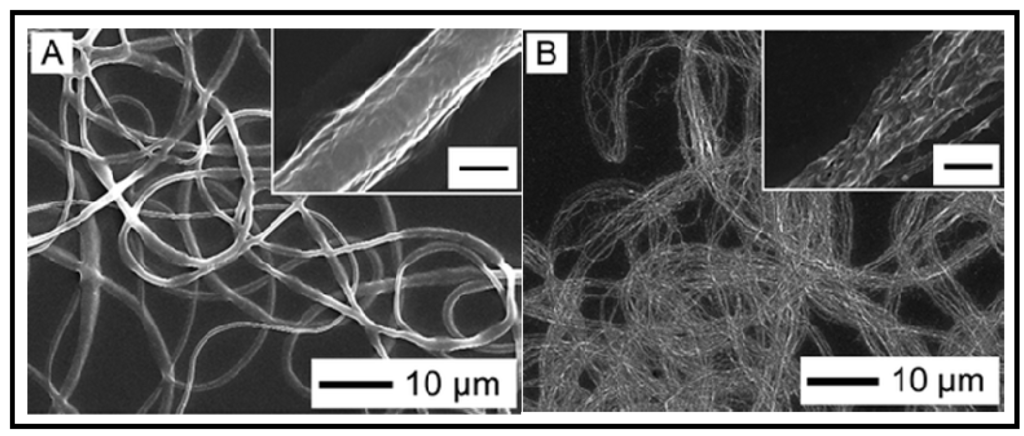

Blends of P3HT and polycaprolactone (PCL) were also electrospun into nanofibers to facilitate the production of continuous nanofibers even at low P3HT concentration (Figure 29). The effect of shear stress in P3HT was also used to fabricate very fine fibers which are not achievable with simple electrospinning. Specifically, P3HT domains in concentrated PCL solution were highly stretched from the electrode and formed fibrils with very small diameters (i.e., ~30 nm) embedded inside PCL composite fibers. Fibrils became connected to one another during the volume shrinkage of the solution by solvent evaporation and finally generate PCL composite fibers with continuous P3HT fibrils embedded inside. The obtained nanofibers were employed to fabricate FETs and the electrical properties were compared. The interfaces between P3HT fibrils and PCL domains can be considered as defect sites that degrade the whole mobility. Nevertheless, the mobility of nanofibers with 20 wt % PCL was found still acceptable (0.0012 cm2/V∙s) to fabricate electronic devices.

Figure 29.

Schemes showing (left) the coaxial electrospinning setup for P3HT electrospinning and (right) the elongation of P3HT domains and formation of continuous P3HT fibrils from the elongation of P3HT domains in highly concentrated PCL solutions. Reprinted with permission from [128]. Copyright 2009 Royal Society of Chemistry.

A mixture of PLGA and poly(3-hexylthiophene) (PHT) was electrospun into 2D random (196 nm) and 3D axially aligned nanofibers (80–200 nm). Aligned nanofibers showed lesser degradation rate and lower pore size (1.9 μm respect to 6.0 μm) and Young’s modulus than random nanofibers, whereas had the higher electrical conductivity (0.1 × 10−5 S/cm). Results of in vitro cell studies indicated that aligned PLGA-PHT nanofibers had a significant influence on the adhesion and proliferation of Schwann cells. The new electrically conducting axially aligned nanofibers provided both electrical and structural cues and could be potentially used as scaffolds for neural regeneration [129].

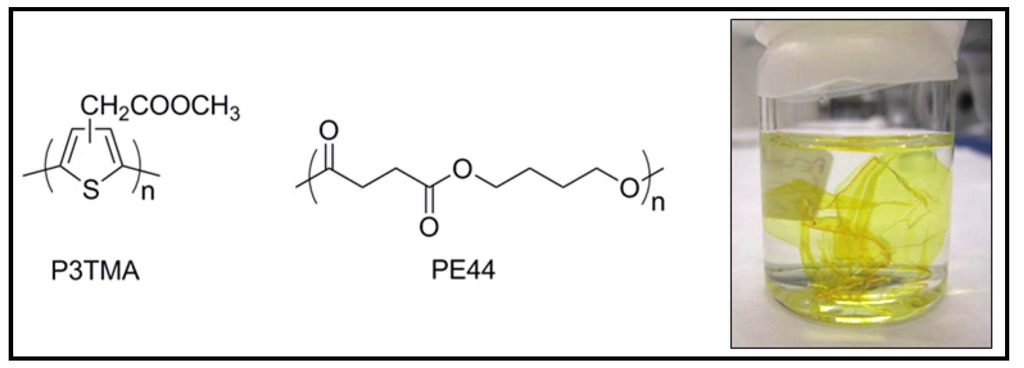

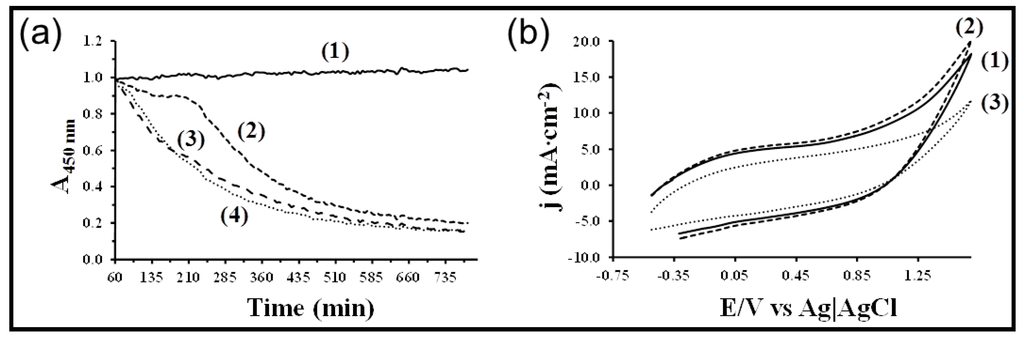

A very stable free-standing nanomembrane with semiconducting (~10−4 to 10−5 S/cm) and biodegradable properties was recently been prepared by combining poly(3-thiophene methyl acetate) (a polythiophene derivative bearing carboxylate substituents in the 3-position of the heterocyclic ring) and poly(tetramethylene succinate) (a commercial biodegradable polyester) (Figure 30) [130]. Both polymers were partially miscible as revealed by calorimetric data and gave rise to the morphology where P3TMA spherical nanoaggregates were embedded in the polyester matrix. The thickness and roughness of membranes could be easily controlled by modifying the spin-coater speed, being possible to attain lower values than 19 and 5 nm, respectively. Despite the low thickness, membranes could be easily manipulated due to good mechanical integrity and stability in air and in ethanol solution. Specifically, the outstanding flexibility and robustness of the nanomembranes floating in ethanol was demonstrated through aspiration in pipette/release/shape recovery cycles, which were repeated without cracking the film [131]. Enzymatic degradation assays indicated that the ultra-thin films were biodegradable due to the presence of the aliphatic polyester. Interestingly, adhesion and proliferation assays with epithelial cells revealed that the behavior of the blend as cellular matrix was superior to that of the two individual polymers, validating the use of the nanomembranes as bioactive substrates for tissue regeneration.

Figure 30.

Chemical structures of poly(3-thiophene methyl acetate) (P3TMA) (left), and poly(tetramethylene succinate) (PE44) (middle) and digital camera image of a P3TMA:PE44 (right) free-standing nanomembrane dispersed in ethanol.

Free-standing and supported nanomembranes have also been prepared by spin-coating mixtures of poly(3-thiophene methyl acetate) and a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) [132]. Partial miscibility between the two components was well demonstrated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and specifically the highest miscibility was found for the blend having 60 wt % of TPU. The thickness of ultra-thin films made with this blend ranged from 11 to 93 nm, while the average roughness was 16.3 nm. In these films the P3TMA-rich phase formed granules, which were dispersed throughout the rest of the film. Quantitative nanomechanical mapping was used to determine the Young’s modulus values, which were found to depend on the thickness of the films. Thus, values determined for the thicker (80–40 nm)/thinner (10–40 nm) regions of TPU, P3TMA and blend samples were 25/35 MPa, 3.5/12 GPa and 0.9/1.7 GPa, respectively. The utility of the nanomembranes for tissue engineering applications was proved by cellular proliferation assays, which showed that the blend was more active as cellular matrix than each of the two individual polymers.