Abstract

To tackle the critical challenges of silica dispersion and interfacial compatibility in natural rubber composites, this study investigated the dispersion behavior of 3-Octanoylthio-1-propyltriethoxysilane (NXT)-modified silica in natural rubber (NR) and the mechanism by which it affects mechanical properties. Three distinct models were constructed: an NR model, an NR composite model containing unmodified silica (SiO2), and an NR composite model containing NXT-modified silica (NXT-SiO2). The radial distribution function (RDF) was used to characterize the dispersion of fillers. The results of filler–filler interactions revealed a reduction in the number of hydrogen bonds between NXT-SiO2 fillers, weakening the filler network strength and enabling NXT-SiO2 to exhibit excellent dispersion. The results of filler–rubber interactions indicated that NXT-SiO2 exhibited stronger interaction forces and compatibility with natural rubber compared to SiO2. To verify the effect of NXT-SiO2 on the mechanical properties of natural rubber composites, uniaxial tensile deformation via molecular dynamics simulation was performed on the three models. The simulation results show that the addition of NXT-SiO2 significantly increases the tensile strength and fracture strain of the composite material, markedly enhancing its mechanical properties. Further studies indicate that NXT-SiO2 improves the overall mechanical properties of the material by altering the distribution of local natural rubber chains. This work elucidated the intrinsic mechanisms—on a molecular level—by which NXT silane coupling agent modifications enhance the dispersion of fillers and improve the mechanical properties of rubber, thereby providing a theoretical basis for the design of high-performance rubber composites.

1. Introduction

Natural rubber is one of the most commonly used elastomers in tire production [1,2]. To enhance the performance of composite materials, fillers are typically added for reinforcement [3,4,5], with carbon black and silica being the most commonly used reinforcing fillers [6,7,8,9,10,11]. With the development of “green tires”, silica has proven to be the preferred filler for manufacturing high-performance tires [12,13]. However, the inherent chemical dissimilarity between silica and natural rubber, characterized by the former’s polar surface and the latter’s non-polar backbone, typically results in poor compatibility in unmodified systems. Additionally, while external factors such as particle size and processing conditions can influence agglomeration, the primary mechanism driving silica clustering remains the hydrogen bonding between its surface polar hydroxyl groups. The abundance of these groups consequently results in poor dispersion within the non-polar rubber matrix. This undermines filler–rubber interfacial interactions and adversely affects the rubber compound’s processing characteristics and mechanical properties [14,15]. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance the dispersion and compatibility of silica fillers in natural rubber and optimize the interfacial interaction between them.

To improve the performance of silica fillers, a common method is to modify the silica surface by adding silane coupling agents, which can significantly enhance the interfacial properties between silica and polymers [16,17,18,19]. Surya et al. [20] reported that TESPT increased the minimum torque of silica-filled ENR compounds and affected the degree of silica dispersion. You et al. [21] reported that Si69 was grafted onto the surface of silica, thereby significantly improving the water contact angle and enhancing the mechanical properties of modified silica/natural rubber composites. The silane coupling agent modification method not only effectively reduces the abundance of hydroxyl groups on the silica surface, enhancing its dispersion in natural rubber, but also significantly improves the interface compatibility between silica and the natural rubber matrix [22,23]. 3-Octanoylthio-1-propyltriethoxysilane (NXT) is a commonly used bifunctional organosilane coupling agent in the rubber industry. Compared to other coupling agents, the octanoyl group as a blocking group of NXT silane results in the lower reactivity of silane during the mixing process, and NXT exhibits higher scorch safety [24,25]. However, the mechanisms by which NXT silane coupling agents enhance the dispersion of silica within rubber matrices and consequently improve mechanical properties remain poorly understood at the molecular level.

With the advancement of computational chemistry, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become a powerful tool for investigating the microscopic structure and properties of materials. At the molecular level, molecular dynamics simulations have been used to explain interactions between interfaces, reveal the interface mechanism between fillers and rubber molecular chains, and have also been proven to be an effective means of evaluating the mechanical properties of polymer materials [26,27]. Wang et al. [28] employed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the thermomechanical and tribological properties of graphene–nano-silica (GNS)-reinforced natural rubber (NR) and discussed the intrinsic interactions and wear mechanisms within polymer nanocomposites at the atomic scale. Liang et al. [29] employed molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the thermal conductivity of natural rubber (NR) and polybutadiene (PB) under varying temperature and pressure conditions, in addition to their interfacial heat transfer characteristics. Long et al. [30] comprehensively investigated the interaction behavior between natural rubber and lignin (NR-L) through molecular dynamics simulations. Liu et al. [31] employed molecular dynamics simulations to study the mechanism of enhancing the mechanical and tribological properties of nitrile rubber by adding nano-SiO2 at the molecular level. Jiang et al. [32] investigated the interfacial interaction mechanisms between SBR and GTR through tensile and shear behavior studies. Wang et al. [33] used molecular dynamics methods to establish a SiO2/cellulose model, grafting silane coupling agents onto the SiO2 surface to enhance the interfacial bonding strength between the filler particles and the matrix and thereby promoting close molecular bonding. The enhanced interfacial bonding reduces the thermal motion of the molecular chains, thereby improving the thermal stability and mechanical properties of the composite material. Therefore, using molecular dynamics simulation methods to study the interaction between rubber and fillers has become a feasible approach.

In this study, NR, NR/SiO2, and NR/NXT-SiO2 composite material models were constructed via MD simulations. This simulation focuses on equilibrium conditions, emphasizing the physical dispersion of fillers during the initial stage of compounding. The objective is to elucidate the mechanism governing the interactions of modified fillers within the natural rubber matrix. Mixing conditions, such as shear and complex temperature profiles, were not considered. In the investigated system, covalent bonds formed through silane coupling reactions between rubber and fillers have not yet been established at this stage [34,35,36]. Through molecular dynamics simulations, the mechanism by which NXT-modified silica enhances its dispersion and improves the mechanical properties of natural rubber at the molecular scale is evaluated. Radial distribution function (RDF) analyses substantiated the enhanced dispersion uniformity of NXT-SiO2 fillers within the rubber matrix. The interactions between filler–filler and filler–rubber interfaces were analyzed using hydrogen bond analysis, mean square displacement (MSD), free volume fraction (FFV), independent gradient model (IGM), and interaction energy calculations. Uniaxial tensile deformation was used to simulate the tensile process of the composite material, elucidating the mechanism by which modified fillers enhance mechanical properties and providing a theoretical basis for the design of high-performance rubber composites.

2. Simulation Methods and Details

2.1. Construction of the Simulation System

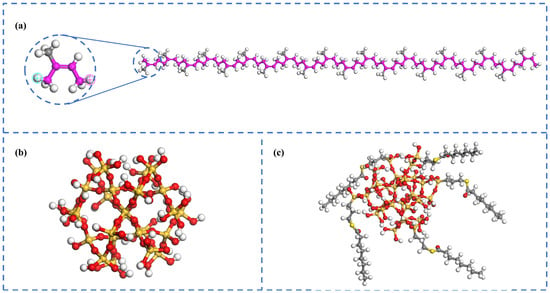

In molecular dynamics simulations, the construction of the model is critical to the simulation results. The monomer of natural rubber is 1,4-isoprene. Existing research indicates that the molecular chain of natural rubber can already exhibit the characteristics of a polymer chain at a polymerization degree of 20 [37,38]. Therefore, we used Materials Studio 2020 software to construct a non-crosslinked natural rubber molecular chain with a polymerization degree of 20. We represented silica fillers (SiO2) using spherical particles with a radius of 0.6 nm, and hydroxyl groups were introduced to eliminate the unsaturated boundary effect and impart genuine surface polarity. This treatment is crucial for accurately simulating the interfacial interactions between natural rubber and silica, as well as the agglomeration behavior of the filler. The silica filler’s surface underwent a typical silanization reaction with the NXT silane coupling agents. Accordingly, we developed a model of silica fillers modified with the NXT molecules (NXT-SiO2) [39]. The molecular models are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Molecular model diagram: (a) NR; (b) SiO2; (c) NXT-SiO2. Atomic color scheme is assigned as follows: H (white), C (gray), O (red), Si (orange), and S (yellow). Carbon atoms in the natural rubber backbone are colored purple herein for clarity; all subsequent figures depict carbon in gray for consistency, while other atomic colors remain unchanged.

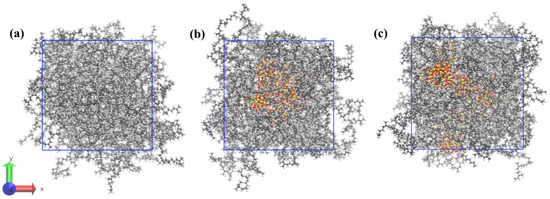

Three simulation systems were constructed, each containing 50 NR molecular chains. Two of these systems were supplemented with SiO2 and NXT-SiO2, respectively. First, the steepest descent method was used to minimize the energy of all composite models to eliminate unreasonable configurations. The systems were first equilibrated for 10 ns in the NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) ensemble. Subsequently, a 12 ns annealing simulation was conducted in the NPT (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) ensemble. Finally, the temperature was reduced to 298 K over 1 ns under the NPT ensemble, followed by a 200 ns run in the same ensemble. The total energy curves of the system converge and gradually flatten with increasing simulation time, indicating that the system of the model has reached equilibrium (Figure S1) [37,40]. The resulting composite models are shown in Figure 2. The parameters of each system are listed in Table 1. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that the radii of gyration (Rg) of the polymer chains in the three models are 26.93, 28.97, and 30.37 Å, respectively, all exceeding the radius of silica nanoparticles (6 Å) [41,42,43]. Consequently, when silica content is constant and the rubber chain length exceeds the length required to achieve fundamental polymer dynamics, the interaction between silica filler and natural rubber is primarily determined by the chemical structures of the filler and natural rubber. Therefore, the construction of the relevant molecular model is reasonable. In addition, the final density of the pure NR model was 0.91 g/cm3, which is consistent with the true density of the natural rubber polyisoprene of 0.92 g/cm3 [28].

Figure 2.

Composite models of each system after balancing: (a) NR; (b) NR/SiO2; (c) NR/NXT-SiO2.

Table 1.

Molecular composition and system density in three simulated systems. (“--” indicates that this component is not included in the simulated system).

2.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Details

The simulation carried out in this study was completed using the GROMACS 2022 software package [44], with the GROMOS54a7 force field [45]. The force field files for the simulated molecules were generated online using the ATB (Automatic Topology Builder) tool [46]. The potential energy functions included bonding interactions such as bond length, bond angle, and dihedral angle, as well as Coulombic interactions and Lennard–Jones potentials:

where rij is the distance between the i-th and j-th atoms, qi is the charge of the i-th atom, σij is related to the equilibrium distance between the i-th and j-th atoms, and εij is the interaction strength.

Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three dimensions of the simulation box. The simulation temperature under the NVT ensemble is controlled at 500 K. During the NPT annealing process, the composite model is subjected to five cycles of annealing at 500 K to 200 K to systematically eliminate unreasonable configurations that may arise from initial structural modeling, thereby rendering the material configuration more rational, which does not represent actual experimental conditions [41]. After annealing, the temperature of the simulated system was lowered to 298 K using the same temperature interval of 25 K and a cooling rate of 25 K/100 ps [47]. A simulation of 200 ns was then performed under NPT conditions at 298 K. The simulation process used the V-rescale thermostat method [48] to control the temperature, and the Berendsen method [49] was used for pressure control with a size of 1 atm. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method [50] was used to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions, and the truncation method was used to calculate the van der Waals interactions and to take into account the long-range corrections to the van der Waals interactions with a truncation radius of 1 nm. During the simulation, the LINCS algorithm was used to constrain all bonds connected to hydrogen atoms [51]. The simulation employed a simulation step size of 1 fs, with trajectories saved at a frequency of one frame every 5 ps. After the simulation calculation was completed, the visualization of the trajectory was generated using the VMD software 1.9.4 [52].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Filler Dispersibility

3.1.1. Radial Distribution Function Analysis

The radial distribution function (RDF) of molecules is a physical quantity that characterizes the microstructural properties of materials. It is the statistical average of the number of other particles at a distance r around a particle and is mainly used to analyze the structural state of a simulated system. In molecular simulations, gAB(r) can be used to characterize the dispersion of fillers [42,53]. The calculation of gAB(r) is shown in the following formula (in this study, particle A and particle B both represent the center of mass of the fillers within the same system. Here, A represents the center of mass of the reference group):

where nAB(r) is the average number of atom pairs between r and r + Δr, and ρAB is the average density of particle type B relative to particle type A.

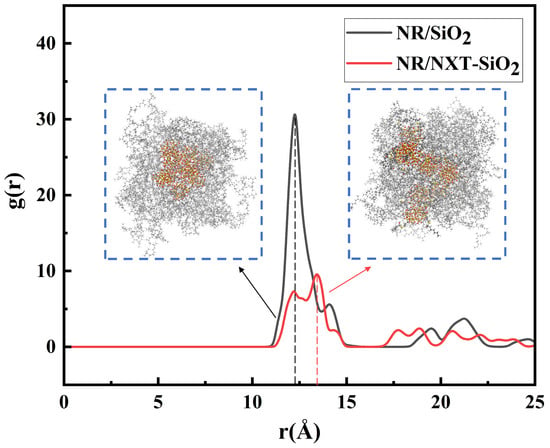

The dispersion of the fillers is determined by calculating the radial distribution function between the molecular centers of the fillers. In this study, the RDF between the centers of mass of the filler molecules in the NR/SiO2 and NR/NXT-SiO2 composite systems was calculated, with the results shown in Figure 3. The peak of g(r) indicates a high probability that the distance between two fillers falls within this range. A high and sharp first peak indicates a tendency for filler agglomeration. In contrast, the composite with NXT-SiO2 exhibits a significantly reduced peak intensity and a flatter g(r) profile, which signifies a more homogeneous, random dispersion state of the NXT-SiO2 fillers within the natural rubber matrix. At the same time, the authors of [42] also report that the larger the r value at the maximum peak, the greater the distance between the silica fillers, and the better the dispersion. It can be observed that the distance corresponding to the maximum peak in the NR/SiO2 system is smaller than that in the NR/NXT-SiO2 system. This indicates that the dispersion of NXT-SiO2 fillers in natural rubber is better than that of SiO2 fillers. This result is consistent with the observations made by Yang et al. using scanning/transmission electron microscopy (SEM/TEM): no significant agglomeration of fillers was observed in NXT-modified silica, indicating its excellent dispersion properties [54].

Figure 3.

Radial distribution function between the molecular centers of mass of the fillers.

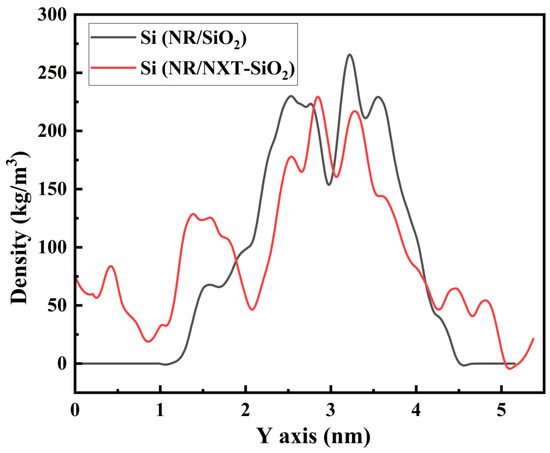

3.1.2. Atomic Density Distribution

Atomic density analysis enables the characterization of filler molecules’ dispersion within natural rubber matrices. The density distribution of silicon atoms in filler molecules along the y-axis is shown in Figure 4. As observed in the figure, there is a relatively long region with zero density for silicon atoms in the NR/SiO2 system, and in another region, their atomic density is relatively high, indicating that the filler may be aggregated in this area. Compared to the NR/SiO2 system, the density distribution of silicon atoms in the NR/NXT-SiO2 composite system is more uniform, indicating that the dispersion of the modified filler NXT-SiO2 is better, with the characteristic peak observed in the RDF in Figure 3 and the visualization in the images confirming this result.

Figure 4.

Density distribution of Si atoms along the y-axis in the filler molecules.

3.2. Filler–Filler Interactions

Analysis of Hydrogen Bonding Interactions

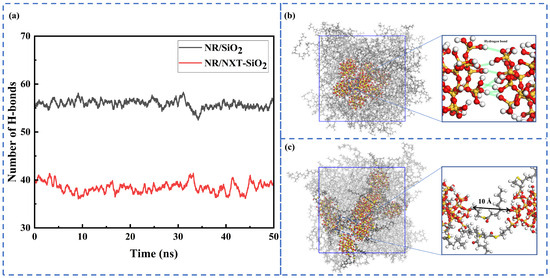

The surface of silica contains a large number of polar hydroxyl groups, which tend to aggregate under the influence of hydrogen bonds. This study calculated the number of hydrogen bonds between SiO2 and NXT-SiO2 fillers over time. Hydrogen bonds were identified using the default geometric criteria of GROMACS: the distance RDA between the donor and acceptor is less than 3.5 Å, and the angle αHB formed between the hydrogen atom donor and acceptor is less than 30°. As shown in Figure 5, it can be observed that the number of hydrogen bonds significantly decreases after modification. This indicates that the improved dispersion of the NXT-SiO2 filler in the rubber matrix is due to NXT silane coupling agents undergoing silanization reactions with silica surfaces, fundamentally altering the physicochemical properties of silica surfaces. The reduction in surface hydroxyl groups directly weakens hydrogen bond formation between fillers, effectively inhibiting their aggregation. Upon local magnifications of the filler molecules, it can be observed that SiO2 fillers form a larger number of hydrogen bonds, while NXT-SiO2 fillers, due to the grafting of NXT silane coupling agents, exhibit reduced surface polarity. Additionally, the presence of the silane coupling agent’s long chain hinders the aggregation of silica molecules, thereby enhancing the dispersion of fillers.

Figure 5.

Hydrogen bonding interactions: (a) changes in the number of hydrogen bonds between fillers over time; (b) localized enlargement of the SiO2 fillers; (c) localized enlargement of the NXT-SiO2 fillers.

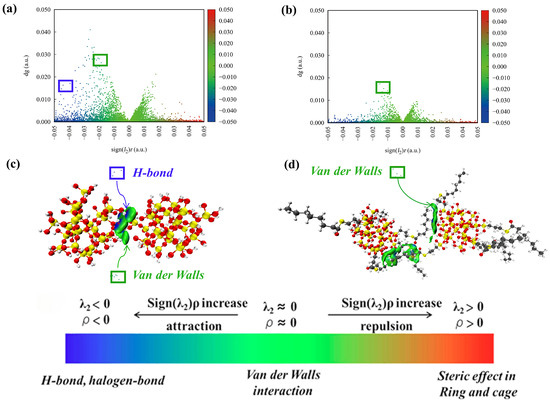

The independent gradient model (IGM) enables the qualitative identification and visualization of the types and spatial regions of non-covalent interactions present at the interfaces [55,56]. To better illustrate the interactions between filler molecules, an independent gradient model analysis was performed on the filler molecules using the Multiwfn software 3.8 [57,58]. The isosurface plots and scatter plots are shown in Figure 6. The blue region represents the presence of strong hydrogen-bonding interactions; the green region represents the presence of van der Waals interactions; the red region represents the presence of strong steric hindrance effects. It can be observed in Figure 6 that hydrogen bond interactions and van der Waals interactions exist between SiO2 fillers, while NXT-SiO2 fillers exhibit van der Waals interactions. Based on IGM visualization analysis, the reason for the improved dispersion of NXT-SiO2 is that the modification reduces the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the silica, and the long chains of the grafted silane coupling agents can form van der Waals interactions with the hydroxyl groups on the silica surface, thereby partially shielding them and weakening the ability of the molecules to form hydrogen bonds. Since hydrogen bonds are typically stronger than van der Waals interactions, the attractive forces between SiO2 fillers are stronger than those between NXT-SiO2 fillers. Therefore, SiO2 fillers are more likely to aggregate, while NXT-SiO2 fillers have better dispersibility.

Figure 6.

IGM between filler molecules: (a,c): SiO2; (b,d): NXT-SiO2.

3.3. Filler–Rubber Interaction

3.3.1. Mean Square Displacement (MSD) Analysis

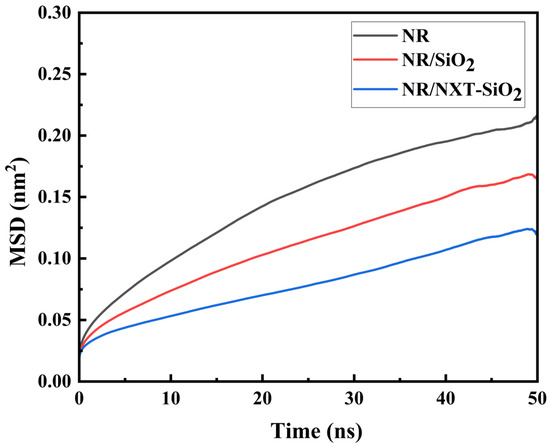

The mean square displacement (MSD) characterizes the motion trends of molecular chains in polymer composites. It is defined as the distance between a particle’s position at time t and its initial position [59]. As shown in the MSD curves of natural rubber molecular chains at 298 K in different composite models in Figure 7, the MSD of natural rubber molecular chains in the two systems with added filler molecules is smaller than that in the pure natural rubber system, with the lowest MSD observed in the system with added NXT-SiO2 fillers. This indicates that filler molecules hinder the movement of natural rubber molecular chains. Compared to SiO2, NXT-SiO2 exerts a stronger hindering effect on the movement of natural rubber molecular chains, resulting in a lower migration ability. This stronger hindering effect is likely due to a combination of stronger filler–rubber interfacial interactions and a more uniform spatial distribution of the NXT-SiO2 filler, both contributing to the more effective restriction of chain mobility [60]. The enhanced hindering effect of filler molecules on natural rubber molecular chains suggests the greater restriction of molecular motion at the atomistic scale, which is often an indicator of potentially improved material stability.

Figure 7.

MSD of natural rubber molecular chains.

3.3.2. Fractional Free Volume Analysis

Fractional free volume (FFV) characterizes the available movement space and mobility constraints for molecular chains within a material. It is closely correlated with material performance and serves as a critical parameter for predicting trends in the mechanical properties of composites [61]. The formula is as follows:

where Vf is the volume of the cavity within the system, and Vo is the volume occupied by the molecule in the system.

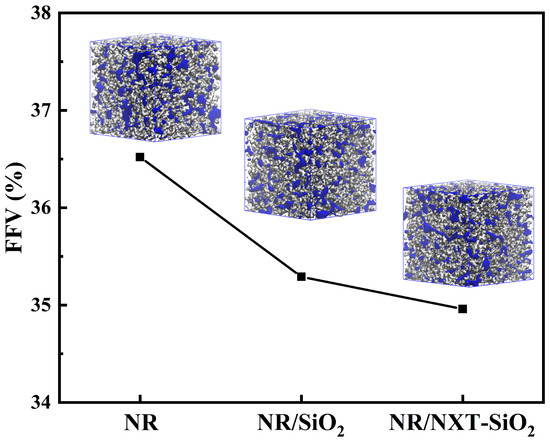

The FFV of the three models after NPT ensemble equilibration is presented in Figure 8, along with their Connolly volume shapes, where blue and gray denote free volume and occupied volume, respectively. The FFV of the models decreases with the addition of fillers. The FFV of the three composite systems reached 36.52%, 35.29%, and 34.96%. The FFV of the NR/SiO2 model is smaller than that of the NR model, and the NR/NXT-SiO2 model is the smallest. It can be concluded that in composite systems composed of filler and rubber matrices, the presence of fillers causes molecular chains to pack more tightly, thereby reducing FFV. The NR/NXT-SiO2 model shows the most compact structure. The reduced FFV suggests tighter molecular packing, which is expected to enhance stress transfer and potentially improve mechanical properties.

Figure 8.

Fractional free volume and Connolly volume morphology.

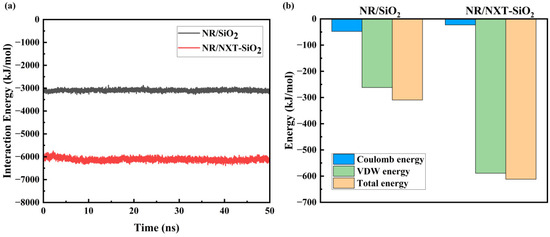

3.3.3. Interaction Energy Analysis

The interaction energy (Einter) between natural rubber and fillers in different composite models was calculated. The binding energy (Ebinding), defined as the negative value of the interaction energy between the two components, was also used as a metric to assess compatibility. High Ebinding values typically indicate strong interfacial adhesion and good compatibility [62]. The calculation formula is as follows:

where Einter represents the interaction energy; Ebinding represents the binding energy; Etotal is the total energy of the NR composite system; Efiller is the energy of the system containing only the filler; and ENR is the energy of the system containing only NR.

It can be observed in Figure 9a that the Einter between the NXT-SiO2 fillers and natural rubber is significantly greater than that between SiO2 fillers and natural rubber. The binding energy of the functionalized NXT-SiO2 fillers with natural rubber reached 6118.4 kJ mol−1, significantly higher than that of the unmodified SiO2 fillers (3096.7 kJ mol−1). This indicates that after modification, the ability of NXT-SiO2 fillers to bind with natural rubber molecules has increased, resulting in more natural rubber molecules aggregating around the NXT-SiO2 fillers and the enhanced stability of the composite model. The compatibility between NXT-SiO2 fillers and natural rubber is superior to that between SiO2 fillers and natural rubber. Additionally, the interaction energy of the final system remains essentially unchanged, indicating that the system has reached equilibrium, which indirectly reflects the feasibility and equilibrium of this computational model. Figure 9b shows the various interaction energies between a filler and natural rubber molecules in different systems. As can be seen, van der Waals interactions are the primary mode of interaction between filler and natural rubber. Additionally, compared to the SiO2 filler, the van der Waals interactions between NXT-SiO2 fillers and natural rubber are significantly enhanced, while electrostatic interactions are reduced. This typically implies improved interface compatibility between the filler and rubber, as well as enhanced filler dispersion. When van der Waals interactions increase, this indicates that the contact between filler and rubber molecules becomes more intimate, improving interfacial compatibility. The increase in van der Waals interactions also facilitates the dispersion of fillers in rubber, as stronger intermolecular forces promote a more uniform distribution of filler particles within the rubber matrix. Improvements in interface compatibility and filler dispersion generally have a positive impact on the performance of rubber composites, consistent with the results from MSD and FFV, as discussed earlier.

Figure 9.

The interaction energy between the filler and natural rubber: (a) time-dependent interaction energy; (b) interaction energy components between a single filler and natural rubber.

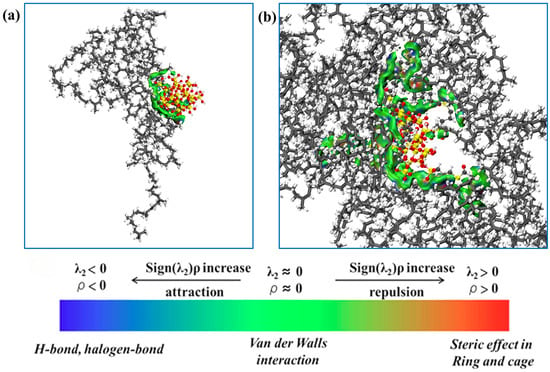

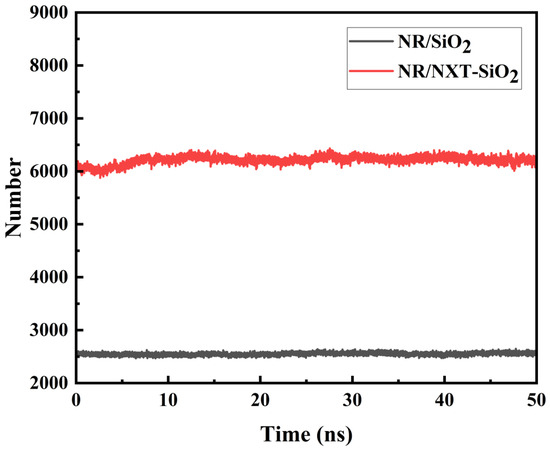

To demonstrate the interactions between filler molecules and rubber molecules, an analysis was conducted using the independent gradient method, with the results shown in Figure 10. The green areas indicate minimal electron density within the weak interaction region, signifying the predominance of dispersion interactions. This distribution demonstrates that van der Waals interactions dominate the binding mechanism at filler–natural rubber interfaces. This conclusion is consistent with the results of the interaction energy calculations. It can be observed that the interaction area between SiO2 fillers and natural rubber is smaller than that between NXT-SiO2 fillers and natural rubber, indicating that NXT-SiO2 fillers can bind with a greater number of natural rubber molecules. This phenomenon is due to SiO2 fillers tending to agglomerate, reducing the area available for contact with natural rubber molecules, while NXT-SiO2 fillers are more uniformly dispersed in natural rubber. Additionally, the organic long chains grafted onto the silica fillers can interact with natural rubber molecules, enhancing the compatibility between NXT-SiO2 fillers and natural rubber. To verify this conclusion, the number of natural rubber atoms in contact with filler molecules in the two composite systems was calculated, as shown in Figure 11. The number of natural rubber atoms in contact with NXT-SiO2 is significantly higher than that with SiO2, demonstrating that NXT-SiO2 can interact more effectively with natural rubber and thereby improve the material’s stability and mechanical properties.

Figure 10.

IGM between fillers and NR molecules: (a) NR/SiO2; (b) NR/NXT-SiO2.

Figure 11.

Number of rubber atoms in contact with fillers.

3.4. Mechanical Properties During the Stretching Process of Each Model

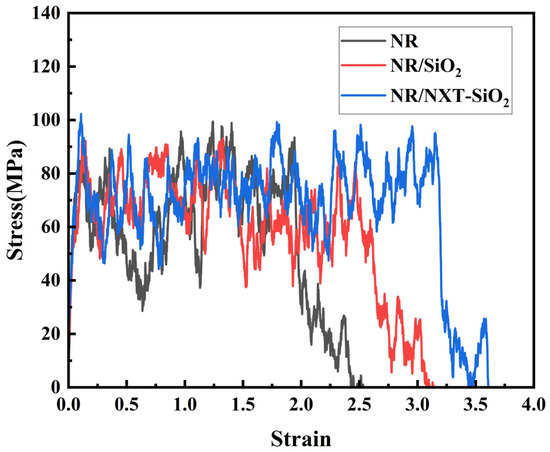

Study of Mechanical Properties During Stretching

A uniaxial tensile simulation was performed on the composite model at 298 K with a deformation rate of 0.005 nm·ps−1 along the y-axis [63]. The stress–strain curves of the three composite models along the y-axis are shown in Figure 12. The stress–strain curve of pure natural rubber conforms to the uniaxial tensile characteristic curve of polymer materials, and it is generally consistent with the simulation results [64,65]. Comparing these results with data from the literature reveals that the stress–strain behavior falls within a reasonable range of variation, thereby validating the reliability of using molecular dynamics simulations to calculate tensile behavior [28,47,66]. It can be observed that the addition of SiO2 fillers increases the fracture strain ε of the composite material model, indicating that the addition of fillers increases the fracture strain when the composite material is stretched to the point of complete separation at both ends. Additionally, the fracture deformation of the NR/NXT-SiO2 system is greater than that of the NR/SiO2 system, and the tensile strength is also enhanced. This is because NXT grafting improves the dispersion of fillers in the NR matrix, weakens the filler–filler network, and reduces stress concentration zones. On the other hand, NXT grafting enhances the strength of the filler–rubber interface interaction and suppresses the movement of molecular chains on the filler surface. From the tensile data, it can be seen that improved filler dispersion is beneficial to the mechanical properties of polymer materials, which is consistent with previous results [67].

Figure 12.

Stress–strain curves of the three models at 298 K.

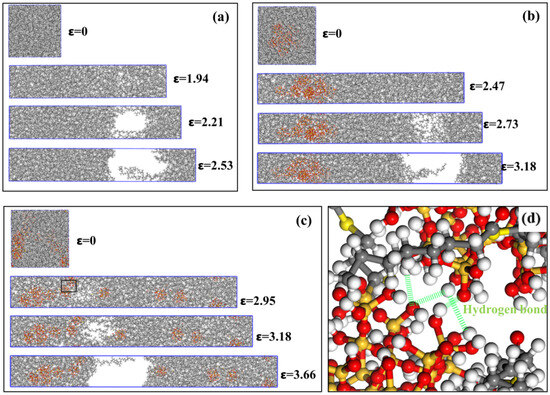

The states of various composite models at different stages of stretching are shown in Figure 13. Taking the NR model as an example, Figure 13a shows the state diagram of the NR model during the stretching process, where ε = 0 represents the computational model at the initial state of stretching. ε = 1.94 represents the tensile state of the model at the strength limit, after which noticeable fracture voids begin to form within the model. As tensile loading continues, the NR molecular chains begin to loosen at the voids. ε = 2.21 illustrates the gradual increase in fracture voids within the model during the neck-shrinkage fracture stage. During this process, the NR chains at the fracture voids gradually separate, and the tensile stress in the y-direction gradually decreases. ε = 2.53 represents the post-fracture state, where the NR molecular chains spanning the fracture interface are separated beyond the cutoff radius of intermolecular interactions, resulting in zero intermolecular forces between the chains and zero tensile stress. At this point, the NR model is completely ruptured. Figure 13b shows a schematic diagram of the stretching process of the NR/SiO2 model. Due to the addition of fillers, the fracture deformation of this model is greater than that of the pure natural rubber model. However, SiO2 fillers tend to aggregate, causing stress concentration at the aggregated particles and resulting in uneven stress distributions within the material. The fracture gap appears near the NR molecular chains, distant from the filler distribution. Figure 13c shows a schematic diagram of the stretching process of the NR/NXT-SiO2 model. The composite exhibits the highest fracture strain among all tested systems. This superior deformability is attributed to the NXT-SiO2 fillers being more uniformly dispersed in the natural rubber matrix. The better the dispersion of the fillers, the greater the stress that the composite material can withstand [68]. Analyses of the fracture interface of the NR/NXT-SiO2 model, as shown in Figure 13d, reveal that one side of the fracture interface (left) exhibits stronger interactions due to the formation of numerous hydrogen bonds between fillers, with a tendency to form filler clusters; in contrast, the other side (right) primarily consists of isolated individual fillers. The interface interactions between these isolated fillers and aggregates are relatively weak, making this area a relatively weak connection point in the model. The fracture occurs at this location primarily due to the significant stress concentration points formed at the interface between the clusters and the isolated fillers.

Figure 13.

States of various composite models at different stretching stages: (a) NR; (b) NR/SiO2; (c) NR/NXT-SiO2; (d) local enlargement of the NR/NXT-SiO2 model, which corresponds to the region designated by the black frame in (c).

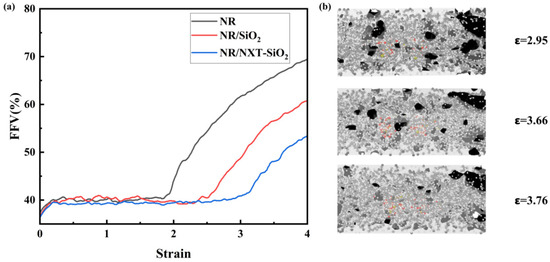

To understand the internal conditions of the material during stretching, the variation in the FFV with respect to stretch deformation was plotted [69]. The model’s molecular surface was visualized using the “construct surface mesh” module in the Ovito software 3.10.6 [70]. As shown in Figure 14a, during the initial stage of stretching, the FFV of all three systems increased proportionally. During the yield stage and strengthening stage, the FFV remained in a state of dynamic equilibrium, with little change in internal porosity. As stretching continued, the FFV continued to increase. It can also be observed that the FFV of the system with added NXT-SiO2 fillers overall decreases during the stretching process, indicating that the NXT-SiO2 fillers render the internal space distribution of the system more uniform during stretching, resulting in more uniform stress distribution in the material. To verify this conclusion, a molecular surface visualization analysis was performed on the NXT-SiO2 fillers and the surrounding natural rubber molecular chains. As shown in Figure 14b, during the neck-down fracture stage, while the overall FFV of the model increases, the NR chains around the NXT-SiO2 fillers exhibit a decreasing trend, indicating that these fillers locally constrain the polymer matrix and enhance mechanical performance.

Figure 14.

FFV curves and molecular visualization of model surfaces during stretching for each model: (a) the variation in the FFV with stretch deformations; (b) molecular surface visualization analysis of NXT-SiO2 fillers and surrounding natural rubber molecular chains.

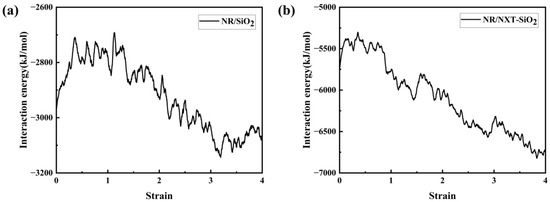

The interaction energy between filler molecules and rubber molecules during the stretching process of the two composite models was calculated, with the results shown in Figure 15. It can be observed that since the interaction is negative, a decrease in the absolute value of the interaction energy indicates a reduction in the interaction force. During the elastic stage, the interaction between the two decreases. After entering the yield stage, the interaction between the two increases sharply until the material gradually separates at both ends and breaks, at which point the interaction energy tends to stabilize. It can be observed that in the NR/NXT-SiO2 system, the interaction between the fillers and natural rubber molecular chains is significantly stronger than in the NR/SiO2 system. Specifically, the NXT-SiO2 filler exhibits a stronger ability to hinder the separation of natural rubber molecular chains, thereby enhancing the material’s mechanical properties.

Figure 15.

Interaction energy change curve during model stretching: (a) NR/SiO2; (b) NR/NXT-SiO2.

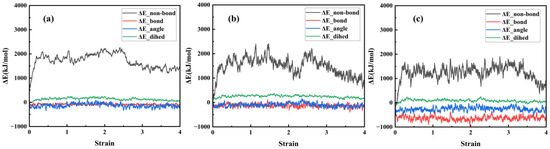

The non-bonded interaction energy, bond energy, angular energy, and dihedral angle energy were calculated for three composite models at 298 K under tensile deformation in the y-direction, with the results shown in Figure 16. The three composite models primarily adjust the system’s energy through non-bonding interaction energy, exhibiting a linear growth trend during the elastic stage and the initial phase of the yield stage. This is primarily due to the sliding mechanism of polymer molecular chains. Non-bonding interaction energy reaches its maximum value during the yield stage and then continuously decreases as the stretching process progresses until the model completely fractures.

Figure 16.

Four energy change curves during the stretching process of three models: (a) NR; (b) NR/SiO2; (c) NR/NXT-SiO2.

4. Conclusions

This study comprehensively explores the mechanism by which NXT improves the dispersion of fillers in an NR matrix and enhances the mechanical properties of NR through analyses of filler dispersion, filler–filler interactions, filler–rubber interactions, and tensile simulations. To effectively reveal the core physical mechanisms, our current model employs a fixed set of parameters and component ratios, but we did not systematically investigate the quantitative impact of varying parameters on simulation results. Future research will systematically examine how changes in key parameters affect the macroscopic properties of composite materials. The research findings are as follows:

- In NXT-SiO2 fillers, due to the silanization reaction between NXT silane coupling agents and the silica surface, the physicochemical properties of the silica surface are fundamentally altered. The number of hydroxyl groups on the filler surface is reduced in NXT-SiO2 fillers, and the organic long chains of the coupling agent molecules hinder the proximity of hydroxyl groups on the nano-silica surface, reducing the formation of hydrogen bonds between nano-silica particles. This weakens filler–filler interactions, resulting in the improved dispersion of fillers.

- NXT-SiO2 fillers exhibit good dispersion and contain grafted long organic chains. After modification, filler molecules can interact with more rubber molecules; this significantly increases the effective contact area, thereby enhancing the van der Waals interactions that dominate the filler–rubber interface and the interaction between fillers and rubber. Compared to unmodified SiO2 fillers, stronger interactions are observed. Additionally, the grafted coupling agent molecules on the surface contain long organic chains, enhancing the compatibility between filler molecules and rubber molecules.

- Uniaxial tensile deformation simulation of the composite model revealed that the addition of NXT-SiO2 fillers enhances the tensile strength limit and increases the fracture limit of the composite material, strengthening its mechanical properties. Analyses showed that, compared to SiO2 fillers, the improved dispersibility of NXT-SiO2 fillers allows them to distribute uniformly within rubber molecules, facilitating stress transfer. Additionally, it exhibits stronger interaction forces with NR chains, enhancing its ability to prevent NR chain separation. This is the key to improvements in mechanical properties. During the neck-down fracture stage, while the overall FFV of the model increases, the NR chains around the NXT-SiO2 fillers exhibit a decreasing trend, indicating that these fillers locally constrain the polymer matrix and enhance mechanical performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polym17243237/s1, Figure S1: Total energy of each system as a function of simulation time; Table S1: Rg of natural rubber molecular chains in various systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., R.J. and X.Z.; methodology, C.L., F.N. and L.L.; software, C.L.; validation, C.L., F.N., R.J., L.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, C.L., F.N. and R.J.; resources, F.N., R.J., Y.H. and L.L.; data curation, C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, C.L.; supervision, F.N., R.J., Y.H., L.L. and X.Z.; project administration, Y.H. and X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shandong Province Key Research and Development Program (No. 2024CXGC010402) and the Young Scholars Program of Shandong University (Zhang X. 11190082364061).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Shandong Province Key Research and Development Program (No. 2024CXGC010402) and the Young Scholars Program of Shandong University (Zhang X. 11190082364061).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors F.N., R.J., Y.H. and L.L. are employed by Tongli TyRE Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that this study was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yamashita, S.; Takahashi, S. Molecular mechanisms of natural rubber biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 821–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Liang, C.; Zhou, S.; Huang, J.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Y. Trans-1,4-poly(isoprene-co-butadiene) rubber enhances abrasion resistance in natural rubber and polybutadiene composites. Polymer 2025, 316, 127855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokobza, L. The reinforcement of elastomeric networks by fillers. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2004, 289, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medalia, A.I.; Kraus, G. Reinforcement of elastomers by particulate fillers. In Science and Technology of Rubber; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 387–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.-J. Effect of polymer-filler and filler-filler interactions on dynamic properties of filled vulcanizates. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1998, 71, 520–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöschl, M.; Vašina, M.; Zádrapa, P.; Měřínská, D.; Žaludek, M. Study of carbon black types in SBR rubber: Mechanical and vibration damping properties. Materials 2020, 13, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Qing, L. Significant influence of bound rubber thickness on the rubber reinforcement effect. Polymers 2023, 15, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Zhang, C.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Niu, L.; Ding, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z. Preparation of hexamethyl disilazane-surface functionalized nano-silica by controlling surface chemistry and its “agglomeration-collapse” behavior in solution polymerized styrene butadiene rubber/butadiene rubber composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 201, 108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neena, G.; Amrutha, S.R.; Rani, J.; Jose, P.M.; Mathiazhagan, A. Nano-silica as reinforcing filler in NR latex: Role of processing method on filler morphology inside the rubber and properties of the nanocomposite. Express Polym. Lett. 2021, 15, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaty, S.; Joseph, R. A novel accelerator combination for the low temperature curing of silica-filled NBR compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 5680–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Lu, J.; Song, W.; Hu, J.; Han, B. Interfacial interaction modes construction of various functional SSBR–silica towards high filler dispersion and excellent composites performances. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18888–18897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Yu, G.; Xie, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q. Effect of silane coupling agent on filler and rubber interaction of silica reinforced solution styrene butadiene rubber. Polym. Compos. 2013, 34, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoul, B.; Marfavi, Y.; Sadeghi, B.; Kowsari, E.; Sadeghi, P.; Ramakrishna, S. Investigating the potential of sustainable use of green silica in the green tire industry: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 51298–51317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Song, J.; Wang, H.; Kan, Z. Silica nanoparticles reinforced natural rubber latex composites: The effects of silica dimension and polydispersity on performance. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L. Silica reinforced epoxidized solution-polymerized styrene butadiene rubber and epoxidized polybutadiene rubber nanocomposite as green tire tread. Polymer 2023, 281, 126082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y. Thermal properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer modified by the silane coupling agent. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 267, 124655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Damodaran, A.; Vishvanathperumal, S. Effect of nano-silica surface-capped by bis [3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl] tetrasulfide on the cure behaviors, mechanical properties, swelling resistance and microstructure of styrene-butadiene rubber/acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber nanocomposites. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Noordermeer, J.W.M.; Dierkes, W.K.; Blume, A. The effect of silanization temperature and time on the marching modulus of silica-filled tire tread compounds. Polymers 2020, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, S. Reactive Processing of Silica-Reinforced Tire Rubber: New Insight into the Time-and Temperature-Dependence of Silica Rubber Interaction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Surya, I.; Hayeemasae, N. Effects of TESPT-silane coupling agent on torque properties and degree of filler dispersion of silica filled natural rubber and epoxidized natural rubbers compounds. Simetrikal J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 1, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Jin, S. Preparation of hydrophobic modified silica with si69 and its reinforcing mechanical properties in natural rubber. Materials 2024, 17, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumkrong, N.; Dittanet, P.; Saeoui, P.; Loykulnant, S.; Prapainainar, P. Properties of silica/natural rubber composite film and foam: Effects of silica content and sulfur vulcanization system. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuinu, P.; Sirisinha, C.; Suchiva, K.; Daniel, P.; Phinyocheep, P. Improvement of mechanical and dynamic properties of high silica filled epoxide functionalized natural rubber. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 2155–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of mixing conditions on the reaction of 3-octanoylthio-1-propyltriethoxysilane during mixing with silica filler and natural rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 94, 2295–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y. Effects of silane coupling agents on the vulcanization characteristics of natural rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 94, 1511–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, F.; Luo, Y.; Yu, X.; Wu, S. Grafting silica onto reduced graphene oxide via hydrosilylation for comprehensive rubber applications: Molecular simulation and experimental study. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 5332–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Xing, M. Enhancement of fracture properties of polymer composites reinforced by carbon nanotubes: A molecular dynamics study. Carbon 2018, 129, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, M.; Duan, X.; Yao, X.; Han, X.; Song, J.; Ma, L. Molecular dynamics simulation of the thermomechanical and tribological properties of graphene-reinforced natural rubber nanocomposites. Polymers 2022, 14, 5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wei, S.; Ma, N.; Li, T.; An, G. Molecular dynamics study on the thermal transport properties at the interface of natural rubber and polybutadi-ene. Langmuir 2025, 41, 15045–15053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Lei, J.; Liu, K.; Hu, G.; Chen, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Xiong, Q. Comprehensive investigation of the interactions between natural rubber and lignin by molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310, 143252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Kuang, F.; Zuo, H.; Huang, J. Mechanical and tribological properties of nitrile rubber reinforced by nano-SiO2: Molecular dynamics simulation. Tribol. Lett. 2021, 69, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhao, J.; Yang, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation of interfacial interaction mechanisms between ground tire rubber and styrene-butadiene rubber enhanced by nanomaterial incorporation. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tang, C.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W. Molecular dynamics simulation on the thermodynamic properties of insulating paper cellulose modified by silane coupling agent grafted nano-SiO2. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 125134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Jiang, T.; Qiu, R.; Lin, G.; Xie, C.; Bi, M. Effect of different silane coupling agent modified SiO2 on the properties of silicone rubber composites: Based on molecular dynamics. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 705, 135615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, X.; Ma, J.; Song, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Q. Interface of polyimide–silica grafted with different silane coupling agents: Molecular dynamic simulation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, C.; Xing, S.; Wang, P.; Zhou, X. Molecular dynamics simulations probing the effects of interfacial interactions on the tribological properties of nitrile butadiene rubber/nano-SiO2 under water lubrication. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Lu, S. Preparation and molecular dynamics simulation of 3-isocyanatopropyltrimethoxysilane-modified sisal microcrystalline cellulose/natural rubber composites. Cellulose 2024, 31, 1603–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qin, Z.; Huang, L.; Lin, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Lu, S. Modified boron nitride reinforced natural rubber composites and molecular dynamics simulation. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 5718–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, H.; Wu, Y. Computational thermomechanical properties of silica–epoxy nanocomposites by molecular dynamic simulation. Polymers 2017, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Zhou, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation in compatibility and mechanical properties of chloroprene rubber/polyurethane blends. Adv. Theory Simul. 2023, 6, 2300249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, H.; Xiang, B.; Chen, X.; Yang, W.; Luo, Z. Temperature dependence of the interfacial bonding characteristics of silica/styrene butadiene rubber composites: A molecular dynamics simulation study. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 40062–40071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qu, L.; Su, H.; Chan, T.W.; Wu, S. Effect of chemical structure of elastomer on filler dispersion and interactions in silica/solution-polymerized styrene butadiene rubber composites through molecular dynamics simulation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 14643–14650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Deng, J.; Zhang, G. Molecular-dynamics study on the thermodynamic properties of nano-SiO2 particle-doped silicone rubber composites. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 212, 111571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, N.; Eichenberger, A.P.; Choutko, A.; Riniker, S.; Winger, M.; Mark, A.E.; Van Gunsteren, W.F. Definition and testing of the GROMOS force-field versions 54A7 and 54B7. Eur. Biophys. J. 2011, 40, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroet, M.; Caron, B.; Visscher, K.M.; Geerke, D.P.; Malde, A.K.; Mark, A.E. Automated topology builder version 3.0: Prediction of solvation free enthalpies in water and hexane. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 5834–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ji, Q.; Hu, D.; Jiang, X.; Wang, R. Molecular dynamics simulation of ultraviolet aging effects on the mechanical and physical properties of natural rubber. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 10819–10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.v.; Van Gunsteren, W.F.; DiNola, A.; Haak, J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.C.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Cao, D.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Z. Nanoparticle dispersion and aggregation in polymer nanocomposites: Insights from molecular dynamics simulation. Langmuir 2011, 27, 7926–7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Han, D.; Huang, C.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X. Enhancing the performance and mechanism of nr/sbr composites by silane coupling agents: An experimental and machine learning study. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Rubez, G.; Khartabil, H.; Boisson, J.-C.; Contreras-García, J.; Hénon, E. Accurately extracting the signature of intermolecular interactions present in the NCI plot of the reduced density gradient versus electron density. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 17928–17936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Teng, F.; Su, B.; Wang, Y. Molecular dynamics study on tribological properties of EUG/NR composites. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 199, 110732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhu, H.; Hu, B.; Chen, H.; Yan, Y. Mechanism and characterization of bicomponent-filler-reinforced natural rubber latex composites: Experiment and molecular dynamics (md). Molecules 2025, 30, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Wu, J.; Su, B.; Wang, Y. Enhanced tribological properties of vulcanized natural rubber composites by applications of carbon nanotube: A molecular dynamics study. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Shi, R.; Zhang, H.; Han, R.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, C. Tetraphenylphenyl-modified damping additives for silicone rubber: Experimental and molecular simulation investigation. Mater. Des. 2021, 202, 109551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarychev, V.M.; Lyulin, A.V.; Larin, S.V.; Gurtovenko, A.A.; Kenny, J.M.; Lyulin, S.V. Molecular dynamics simulations of uniaxial deformation of thermoplastic polyimides. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 3972–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, D.; Tschopp, M.A.; Ward, D.K.; Bouvard, J.-L.; Wang, P.; Horstemeyer, M.F. Molecular dynamics simulations of deformation mechanisms of amorphous polyethylene. Polymer 2010, 51, 6071–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Singaravel, D.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, P.; Patel, P.R. Effect of functionalization and defects in carbon nanotube on mechanical properties and creep behavior of nitrile butadiene rubber composites: A molecular dynamics approach. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2023, 62, 1998–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.T.; Yasui, T.; Tanaka, R.; Masunaga, H.; Kabe, T.; Tsunoda, K.; Sakurai, S.; Urayama, K. Unraveling non-uniform strain-induced crystallization near a crack tip in natural rubber. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, D.; Ye, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, S. Development and molecular dynamics simulation of green natural rubber composites with modified sisal microcrystalline cellulose. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2023, 29, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, C.; Yan, Y.; Tao, Y.; An, G.; Li, T. Effect of noncovalent bonding modified graphene on thermal conductivity of graphene/natural rubber composites based on molecular dynamics approach. Langmuir 2025, 41, 6565–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Dong, Y.; Guo, H.; Yang, E.; Chen, Y.; Luo, M.; Pan, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, H. Minute-scale evolution of free-volume holes in polyethylenes during the continuous stretching process observed by in situ positron annihilation lifetime experiments. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 4748–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with ovito–the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2009, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).