An Euler Graph-Based Path Planning Method for Additive Manufacturing Thin-Walled Cellular Structures of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

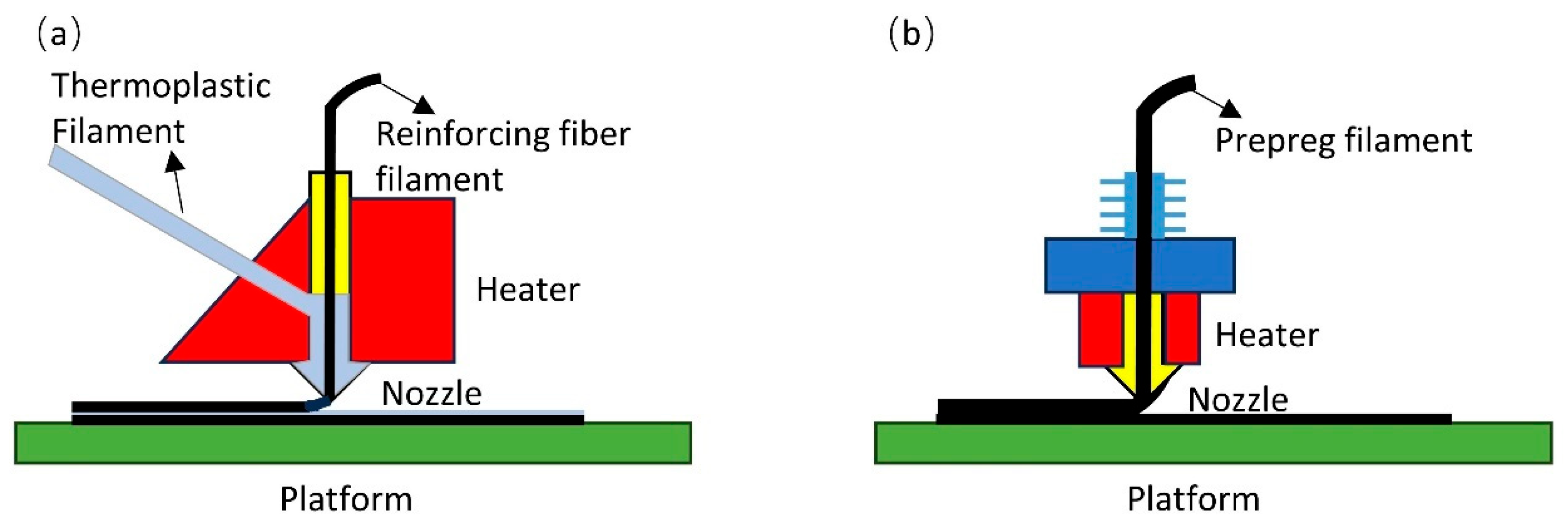

2. Materials and Methods

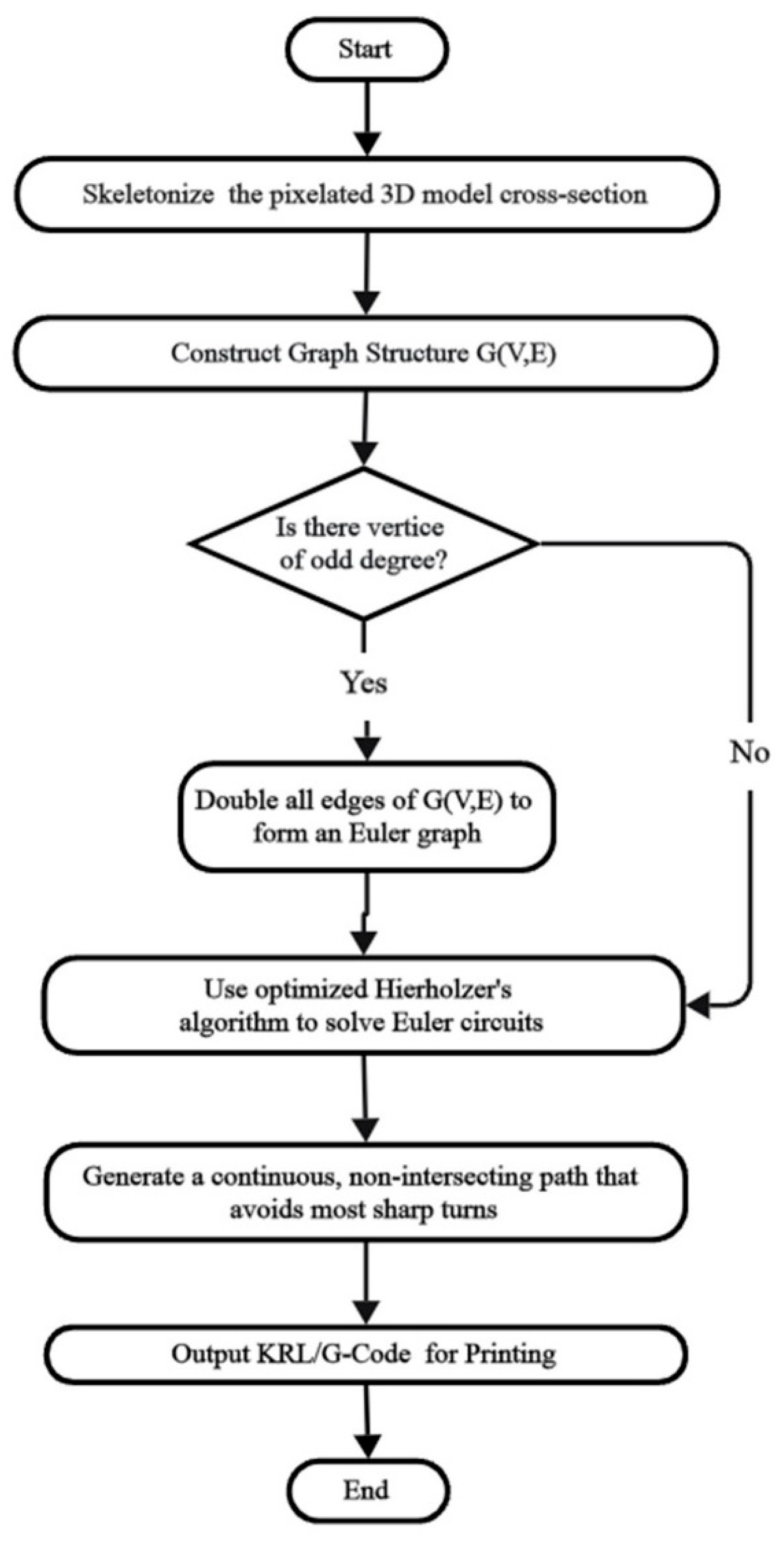

2.1. Algorithm Overview

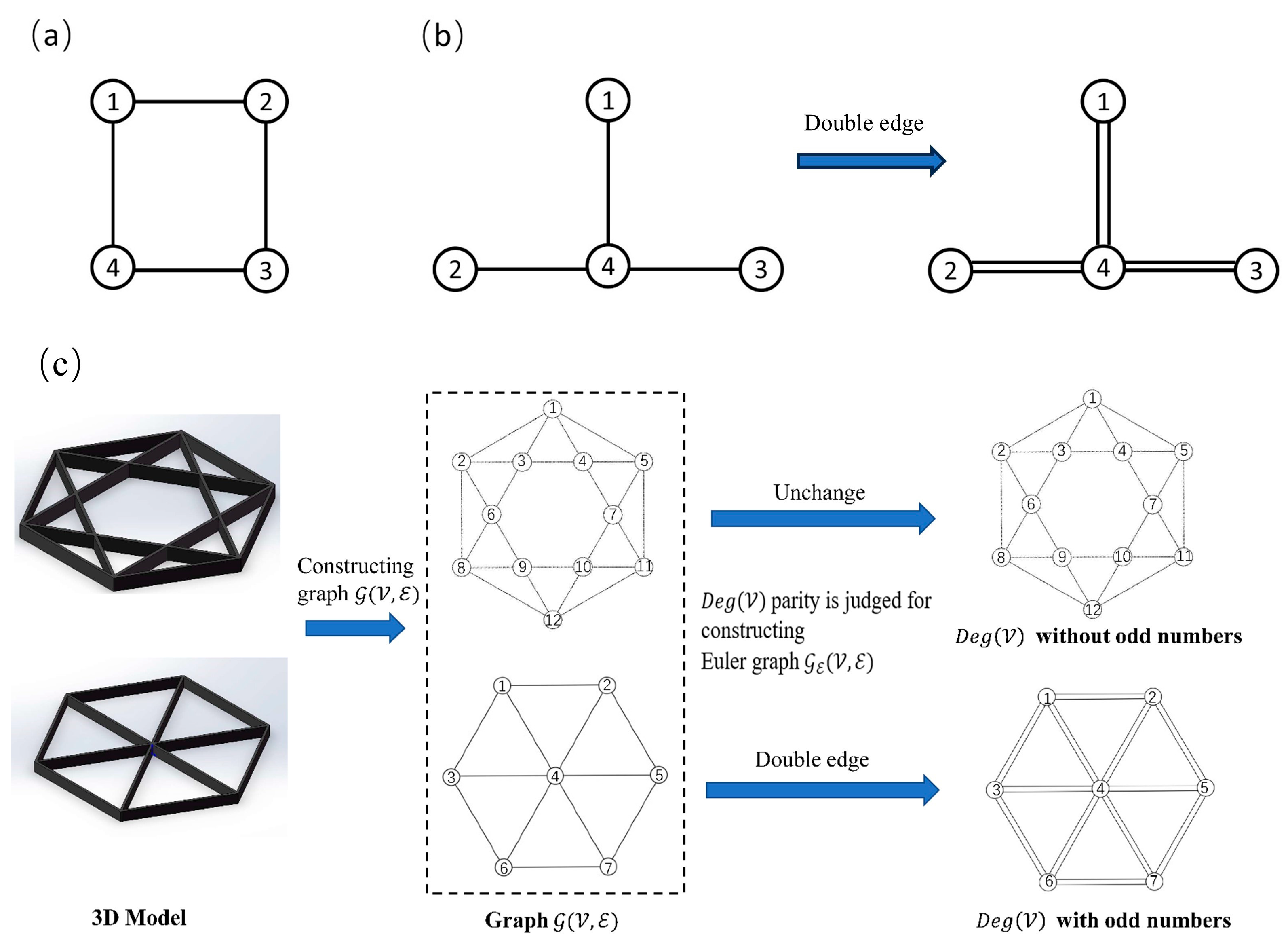

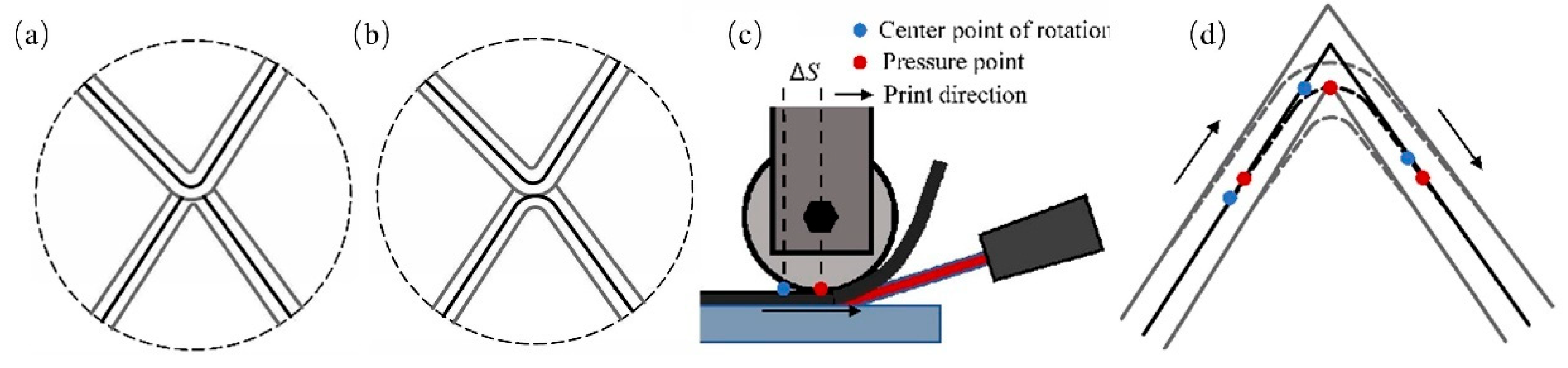

2.2. Construction of Euler Graph

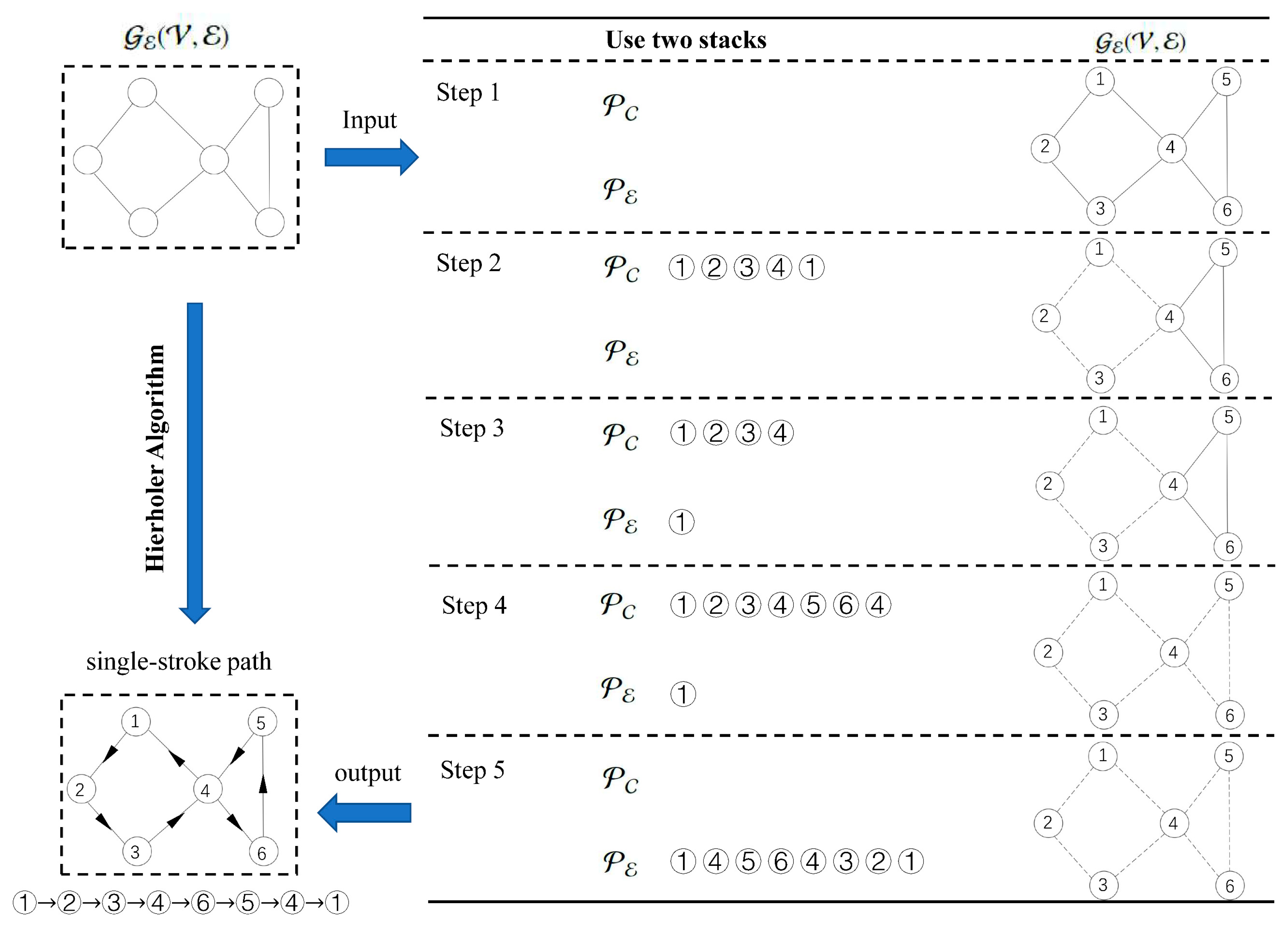

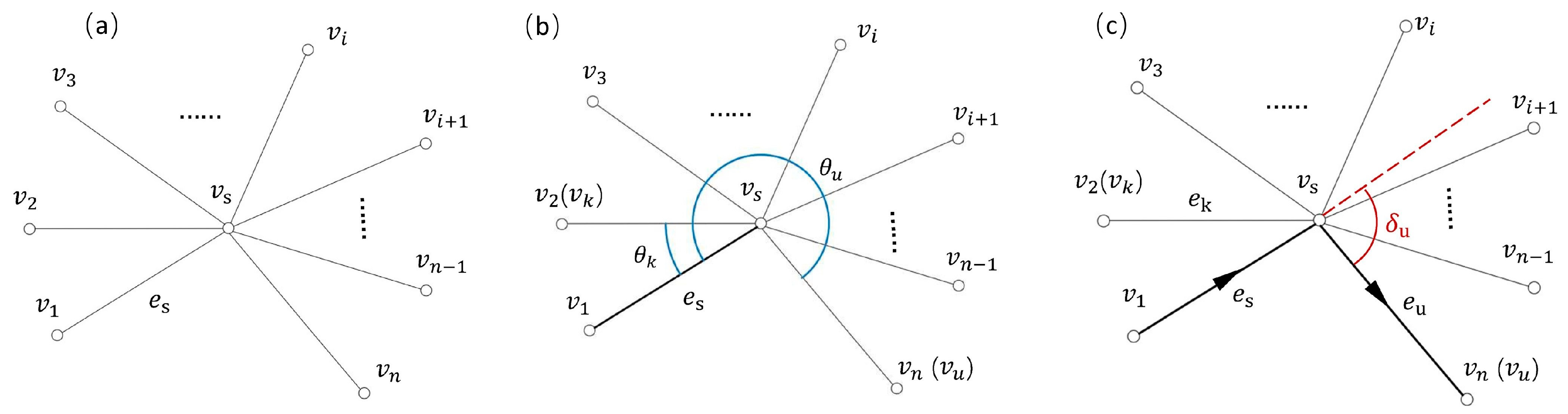

2.3. Solution of Euler Graphs

| Algorithm 1: Hierholzer’s Algorithm |

| Input: Undirected graph Output: Euler circuit 1: function Circular Path( Adjacent vertex list , Start vertex ) 2: Find an adjacent vertex of and remove from [] 3: Creat a stack 4: while and are unequal do 5: Creat a stack 6: Find an adjacent vertex of and remove from [] 7: 8: end while 9: return 10: end function 11: 12: function EulerCircuit() 13: Creat Adjacent vertex list from 14: CircularPath(, ) is a random vertex in 15: for Check each vertex in do 16: if Have any [] then 17: Circular Path(, ) 18: Insert in reverse order at of 19: end if 20: end for 21: return 22: end function |

| Algorithm 2: Non-crossing path algorithms for optimizing turning-Angle |

| 1: function OptimizationPath(Adjacent vertex list , Start vertex , Start edge ) 2: for Check each vertex in [] do 3: is the edge formed by and 4: if then 5: else 6: end if 7: 8: end for 9: 10: 11: 12: if then 13: else 14: end if 15: Creat a stack 16: while and are unequal do 17: Creat a vertex 18: Find an adjacent vertex of and remove from [] 19: 20: end while 21: return 22: end function |

3. Results and Discussion

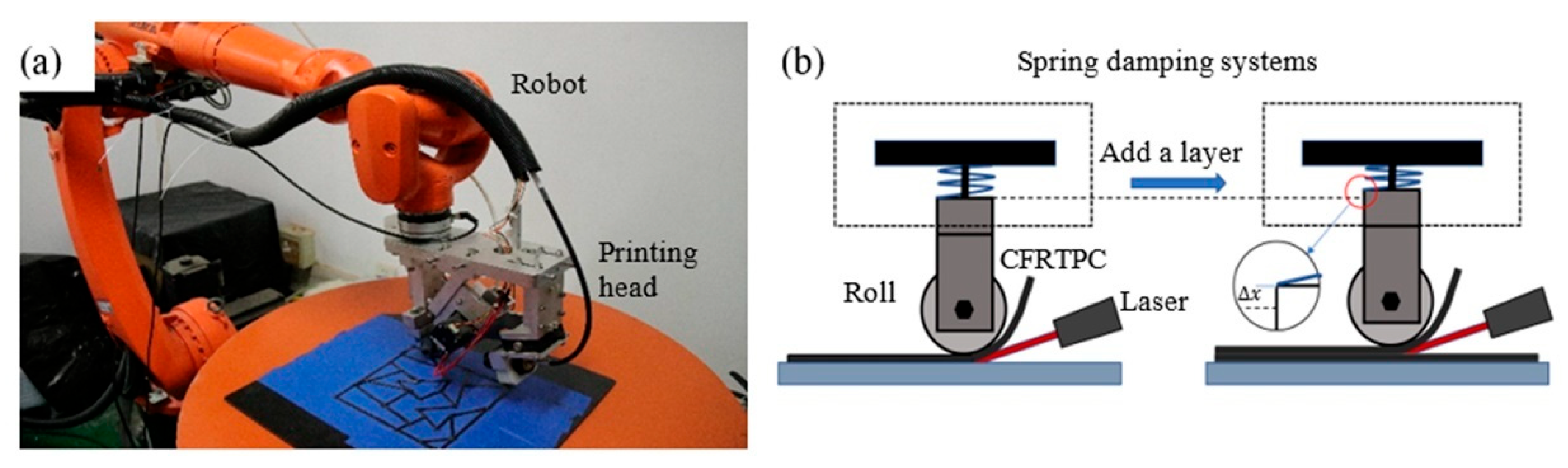

3.1. Robot-Assisted Additive Manufacturing System

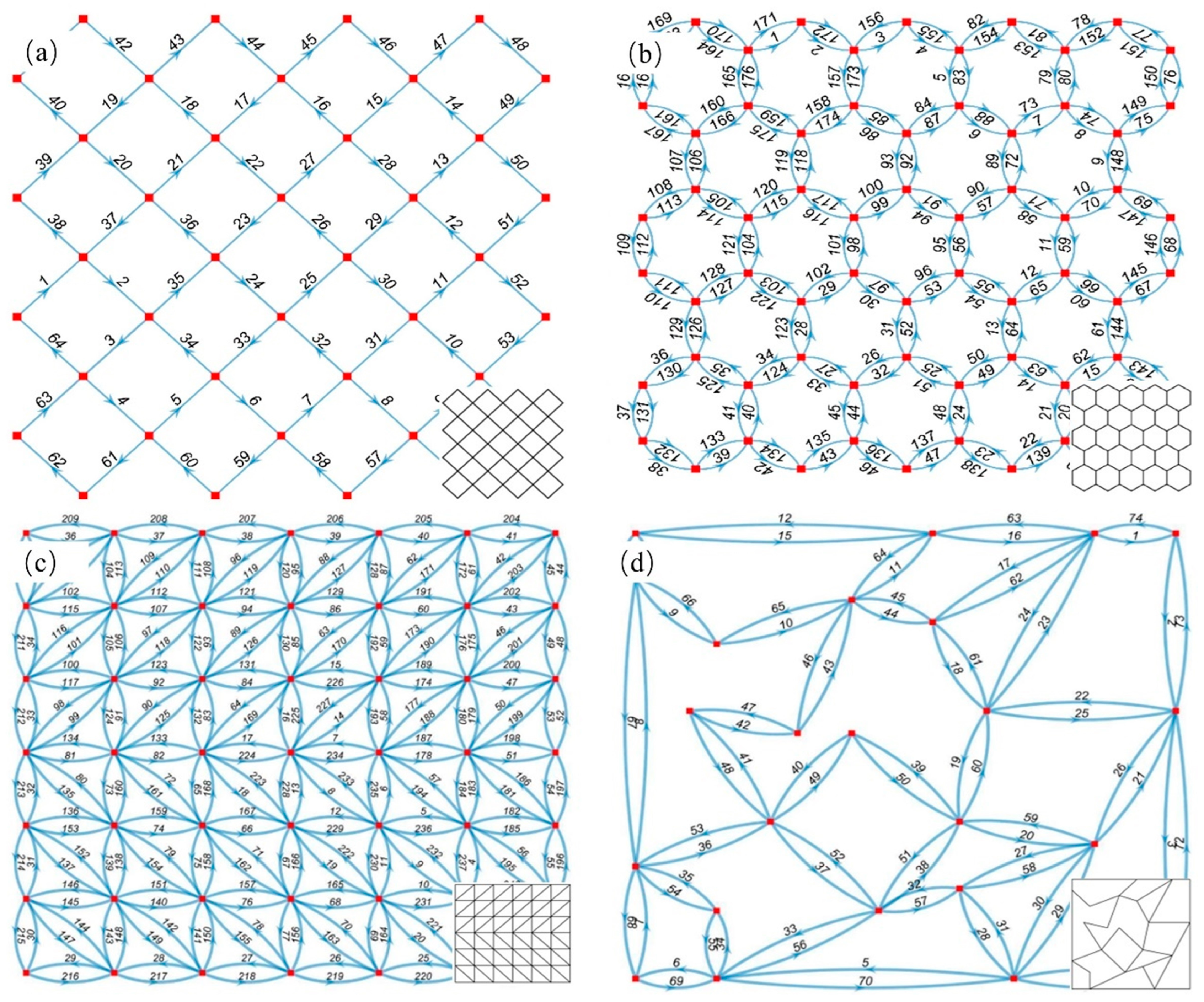

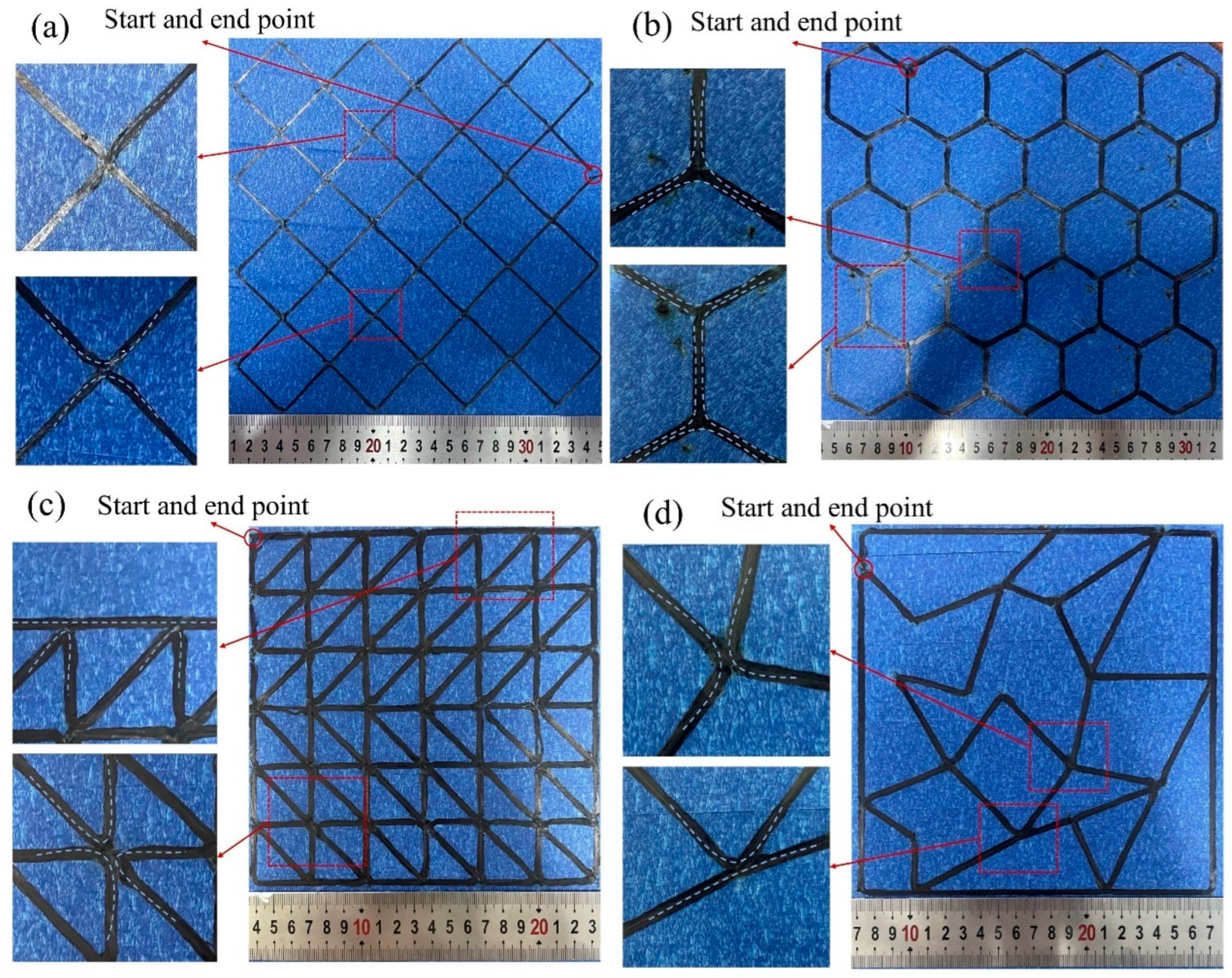

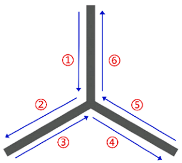

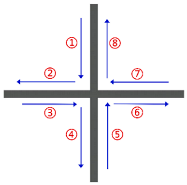

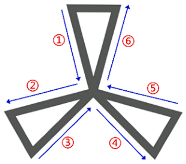

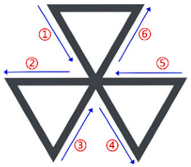

3.2. Visualization of Generated Paths

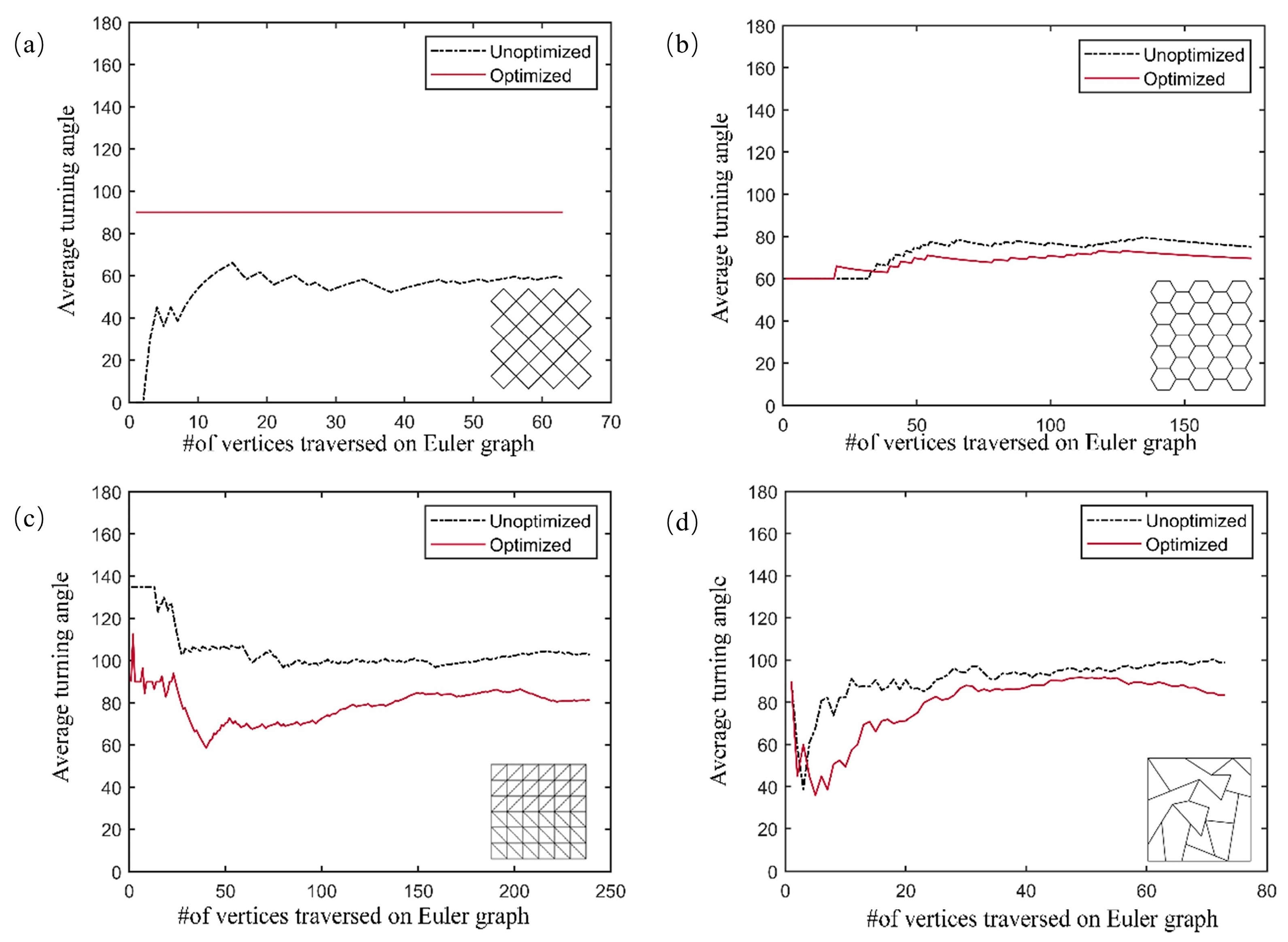

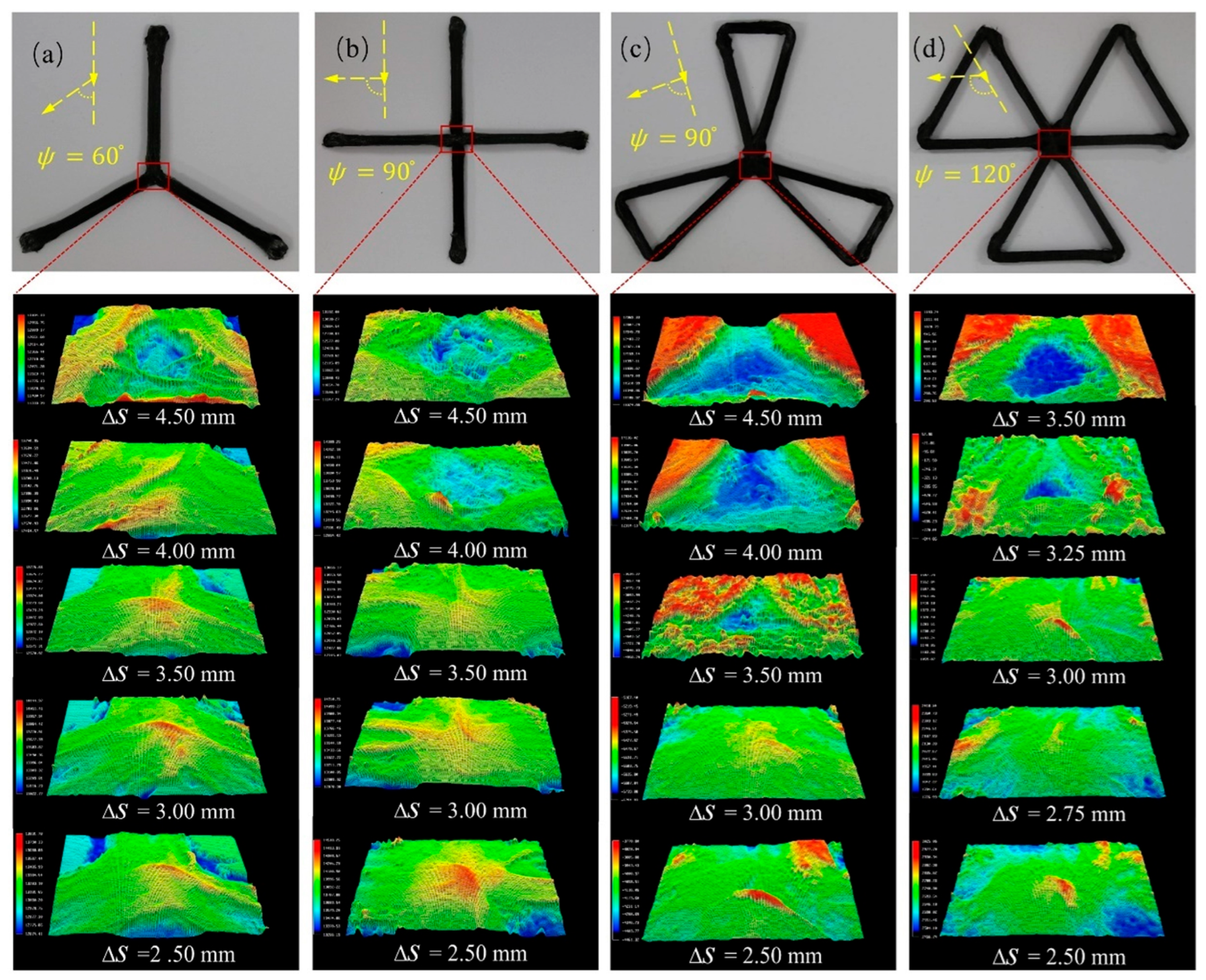

3.3. Quality Evaluation

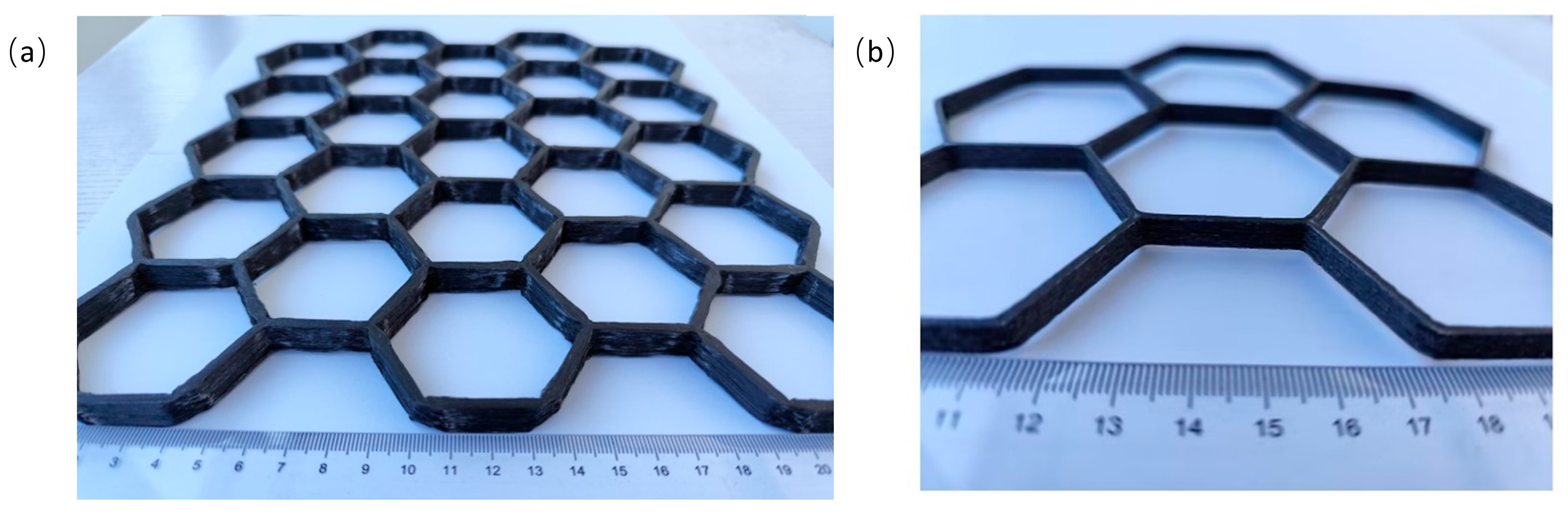

3.4. Experiment Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Tian, X.; Wu, L.; Akmal Zia, A.; Liu, T. Progressive concurrent topological optimization with variable fiber orientation and content for 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced polymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 255, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, P.; Li, S.; Ashcroft, I.; Jones, A. Material extrusion additive manufacturing of continuous fibre reinforced polymer matrix composites: A review and outlook. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 224, 109143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Cho, N.; Lee, Y.; Kim, C. Comprehensive parametric analyses on the mechanical performance of 3D printed continuous carbon fibre reinforced plastic. Compos. Struct. 2024, 329, 117804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J.; Li, A.; Liu, J.; Yang, D. 3D printing of continuous carbon fibre reinforced polymer composites with optimised structural topology and fibre orientation. Compos. Struct. 2023, 313, 116914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zou, B.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, X. Layer thickness and path width setting in 3D printing of pre-impregnated continuous carbon, glass fibers and their hybrid composites. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 83, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, P.; Alitta, G.; Sala, G.; Landro, L. Fused Deposition Technique for Continuous Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, J.; Távara, L.; García-Guzmán, L. Characterization of 3D printed long fibre reinforced composites. Compos. Struct. 2017, 185, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J. 3D Printed Continuous Fibre Reinforced Composite Corrugated Structure. Compos. Struct. 2017, 184, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, R.; Ueda, M.; Namiki, M.; Jeong, T.-K.; Asahara, H.; Horiguchi, K.; Nakamura, T.; Todoroki, A.; Hirano, Y. Three-dimensional printing of continuous-fiber composites by in-nozzle impregnation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. An investigation of preparation of continuous carbon fiber reinforced PLA prepreg filament. Compos. Commun. 2023, 39, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, B.; Ge, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Fang, D. Mechanical performances of continuous carbon fiber reinforced PLA composites printed in vacuum. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 225, 109277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, D.; Yan, B.; Peng, F. Manufacturing and 3D printing of continuous carbon fiber prepreg filament. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tian, X.; Liu, T.; Cao, Y. 3D printing for continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites: Mechanism and performance. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. High-pressure interfacial impregnation by micro-screw in-situ extrusion for 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced nylon composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 130, 105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usun, A.; Gümrük, R. The Mechanical Performance of the 3D Printed Composites Produced with Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced Filaments Obtained via Melt Impregnation. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminero, M.; Chacón, J.M.; García-Moreno, I.; Reverte, J.M. Interlaminar bonding performance of 3D printed continuous fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modelling. Polym. Test. 2018, 68, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuro, R.; Ueda, M.; Matsuzaki, R.; Todoroki, A.; Hirano, Y. Three-dimensional printing of continuous carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastics by in-nozzle impregnation with compaction roller. In Proceedings of the 21st ICCM International Conference on Composite Materials, Xi’an, China, 20–25 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, P.; Malhan, R.; Shembekar, A.; Yoon, Y.J.; Gupta, S. Expanding capabilities of additive manufacturing through use of robotics technologies: A survey. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 31, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bk, N.; Veeman, D.; Mahesh, V.; Kumar, K.P.; Chalawadi, D.; Sathish, T. Review on characterization and impacts of the lattice structure in additive manufacturing. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 21, 916–919. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Lu, G.; Liu, K. Quasi-static axial compression of thin-walled tubes with different cross-sectional Shapes. Eng. Struct. 2013, 55, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z. Energy absorption properties of non-convex multi-corner thin-walled columns. Thin-Walled Struct. 2011, 51, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Chen, D.; Xintao, H.; Zheng, G.; Li, Q. Experimental and Numerical Studies on Indentation and Perforation Characteristics of Honeycomb Sandwich Panels. Compos. Struct. 2018, 184, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Lu, G.; Ruan, D.; Wang, Z. Plastic Deformation, Failure and Energy Absorption of Sandwich Structures with Metallic Cellular Cores. Int. J. Prot. Struct. 2010, 1, 507–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.J.; Lu, G.; Yu, T. Dynamic behavior of graded honeycombs—A finite element study. Compos. Struct. 2013, 98, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Lu, G.; Yu, T. In-plane dynamic crushing of honeycombs—A finite element study. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2003, 28, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Matsuzaki, R.; Ueda, M.; Todoroki, A.; Hirano, Y. 3D printing of composite sandwich structures using continuous carbon fiber and fiber tension. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 113, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.G.; Ashraf, M.; Mines, R.A.W.; Hazell, P. Metallic microlattice materials: A current state of the art on manufacturing, mechanical properties and applications. Mater. Des. 2016, 95, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gu, F.; Huang, Q.X.; Garcia, J.; Chen, Y.; Tu, C.; Benes, B.; Zhang, H.; Cohen-Or, D.; Chen, B. Connected fermat spirals for layered fabrication. ACM Trans. Graph. 2016, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Jian, H.; Xiong, Y. A Graph-Based Path Planning Method for Additive Manufacturing of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Planar Thin-walled Cellular Structures. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2023, 29, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Hazell, P.; Wang, H.; Escobedo, J.; Ameri, A. Lessons from nature: 3D printed bio-inspired porous structures for impact energy absorption—A review. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Chen, F. Path Planning of a Type of Porous Structures for Additive Manufacturing. Comput.-Aided Des. 2019, 115, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Ma, G. Shearing algorithm and device for the continuous carbon fiber 3D printing. J. Adv. Mech. Des. Syst. Manuf. 2019, 13, JAMDSM0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Song, X.; Ding, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Ke, Y. Influence of fiber cutting at the composite grid intersection on the compressive performance of laminate. Compos. Struct. 2021, 267, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, D. Fibre misalignment and breakage in 3D printing of continuous carbon fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 38, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Liu, L.; Bian, W.; Leng, J.; Liu, Y. Compression behavior and energy absorption of 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced composite honeycomb structures with shape memory effects. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F.; Tan, Y.; Yi, R. Molding process and properties of continuous carbon fiber three-dimensional printing. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tian, X.; Zheng, Z.; Malakhov, A.; Polilov, A. Multiscale concurrent design and 3D printing of continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites with optimized fiber trajectory and topological structure. Compos. Struct. 2022, 285, 115241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Krishnamoorthy, B.; Dreifus, G. Continuous toolpath planning in a graphical framework for sparse infill additive manufacturing. Comput.-Aided Des. 2020, 127, 102880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Continuity Path Planning for 3D Printed Lightweight Infill Structures. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Telecommunications, Optics and Computer Science (TOCS), Shenyang, China, 10–11 December 2021; pp. 959–962. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K.; Salazar, J.; Shirasu, K.; Hoshikawa, Y.; Okabe, T.; Hirata, Y. A novel single-stroke path planning algorithm for 3D printers using continuous carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastics. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Fang, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.C.L. Turning-Angle Optimized Printing Path of Continuous Carbon Fiber for Cellular Structures. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 68, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Qiang, H.; Cai, G.; Tan, C.; Zhao, C. Detecting ripe fruits under natural occlusion and illumination conditions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | Average Turning-Angle (Deg) | 120° | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unoptimized | Optimized | Unoptimized | Optimized | |

| Quadrilateral grid | 58.57 | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| Honeycomb | 75.81 | 66.85 (↓ 11.82%) | 87.43 | 92 (↑ 5.227%) |

| Truss | 102.8 | 81.34 (↓ 20.88%) | 53.56 | 64.85 (↑ 21.08%) |

| RTWCS | 98.84 | 83.48 (↓ 15.54%) | 61.64 | 78.08 (↑ 26.67%) |

| Node Test Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 1.5 | 4.50 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 66.56% |

| 4.00 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 99.68% | |||

| 3.50 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 103.2% | |||

| 3.00 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 108.6% | |||

| 2.50 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 113.9% | |||

| 90 | 2 | 4.50 | 0.34 ± 0.17 | 62.70% |

| 4.00 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 78.39% | |||

| 3.50 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 97.03% | |||

| 3.00 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 107.2% | |||

| 2.50 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 126.1% | |||

| 90 | 3 | 4.50 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | 27.23% |

| 4.00 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 39.36% | |||

| 3.50 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 49.33% | |||

| 3.00 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 105.6% | |||

| 2.50 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 130.6% | |||

| 120 | 3 | 3.50 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 35.80% |

| 3.25 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 59.36% | |||

| 3.00 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 100.2% | |||

| 2.75 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 121.9% | |||

| 2.50 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 128.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, G.; Wang, F.; Tu, Q.; Hu, N.; Ouyang, Z.; Wei, W.; Yang, L.; Yan, C. An Euler Graph-Based Path Planning Method for Additive Manufacturing Thin-Walled Cellular Structures of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233236

Liu G, Wang F, Tu Q, Hu N, Ouyang Z, Wei W, Yang L, Yan C. An Euler Graph-Based Path Planning Method for Additive Manufacturing Thin-Walled Cellular Structures of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233236

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Guocheng, Fei Wang, Qiyong Tu, Ning Hu, Zhen Ouyang, Wenting Wei, Lei Yang, and Chunze Yan. 2025. "An Euler Graph-Based Path Planning Method for Additive Manufacturing Thin-Walled Cellular Structures of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233236

APA StyleLiu, G., Wang, F., Tu, Q., Hu, N., Ouyang, Z., Wei, W., Yang, L., & Yan, C. (2025). An Euler Graph-Based Path Planning Method for Additive Manufacturing Thin-Walled Cellular Structures of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers, 17(23), 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233236