Abstract

The incorporation of remineralizing additives into sealants has been considered as a feasible way to prevent caries by potential remineralization through ions release. Thus, this systematic review aimed to identify the remineralizing additives in resin-based sealants (RBS) and assess their performance. Search strategies were built to search four databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, Web of Science and Scopus). The last search was conducted in June 2020. The screening, data extraction and quality assessment were completed by two independent reviewers. From the 8052 screened studies, 275 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 39 laboratory studies matched the inclusion criteria. The methodologies used to assess the remineralizing effect included microhardness tests, micro-computed tomography, polarized-light microscopy, ions analysis and pH measurements. Calcium phosphate (CaP), fluoride (F), boron nitride nanotubes (BNN), calcium silicate (CS) and hydroxyapatite (HAP) were incorporated into resin-based sealants in order to improve their remineralizing abilities. Out of the 39 studies, 32 studies focused on F as a remineralizing agent. Most of the studies confirmed the effectiveness of F and CaP on enamel remineralization. On the other hand, BNN and CS showed a small or insignificant effect on remineralization. However, most of the included studies focused on the short-term effects of these additives, as the peak of the ions release and concentration of these additives was seen during the first 24 h. Due to the lack of a standardized in vitro study protocol, a meta-analysis was not conducted. In conclusion, studies have confirmed the effectiveness of the incorporation of remineralizing agents into RBSs. However, the careful interpretation of these results is recommended due to the variations in the studies’ settings and assessments.

1. Introduction

For many countries, oral diseases are considered to be a health burden because they affect people throughout their life, causing pain, discomfort and defacement. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017, oral diseases affect around 3.5 billion people globally, with caries of permanent teeth being the most frequent condition [1].

Dental caries are one of the most prevalent oral diseases. They are caused by interaction between bacterial acids and fermentable carbohydrates. The bacterial acids produced from the bacterial biofilm diffuse into the enamel and dentin, causing demineralization. Caries are considered to be a dynamic process that includes cycles of demineralization and remineralization [2,3]. Remineralization is a natural reparative mechanism for non-cavitated lesions. It depends on calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) ions, with the help of fluoride (F), to create a new surface on existing crystal remnants in the subsurface lesions that remain after demineralization. Thus, F increases Ca and P precipitation, as well as the development of Fluorhydroxyapatite in tooth tissues [4,5].

A white-spot lesion is the earliest form of dental caries. The continuity of the demineralization process will lead to cavitation. Once the cavitation takes place, preventive measures may not be effective [3]. If a good oral environment can be achieved before cavitation, the caries’ progression can be arrested or reversed [6]. Therefore, caries can be prevented when the remineralization process overcomes the demineralization by either reducing pathogenic factors or increasing protective factors [5]. The use of F can reduce the prevalence of dental caries and their progression rate. Thus, preventive and conservative management strategies such as the application of topical F, pit and fissure sealants, and the use of fluoridated toothpaste and mouth-rinses can help in caries prevention [7].

Pits and fissures of occlusal surfaces are more prone to caries, as they act as reservoirs for Streptococcus mutans [8]. Dental sealants on deciduous and permanent teeth act as a physical barrier between the pits and fissures and the oral environment. Thus, the pit and fissure sealants can effectively prevent caries and reduce the need for further restorations by inhibiting microorganisms and plaque accumulation [9]. Methyl cyanoacrylate was the first pit and fissure sealant to be introduced in the 1960s by Cueto. However, this sealant was susceptible to bacterial disintegration with time [10]. Afterward, Bowen developed a viscous resin known as BIS-GMA that effectively bonds with etched enamel and overcomes the bacterial disintegration that Cueto suffered [11].

Different materials are used in pit and fissure sealants, such as resin-based sealants (RBS) and glass ionomer (GI) sealants. RBS are categorized into four generations based on their method of polymerization. Nuva-Seal is an example of the first generation, which is polymerized by ultraviolet light. However, it is not used anymore. The second generation of the RBS are chemically cured by adding tertiary amine to their composition [6]. The third generation has a short setting time, as it is polymerized by light [12]. The last generation is the fluoride-releasing RBS. According to the RBS’ viscosity, RBS can be categorized into filled and unfilled sealants. Moreover, it can be categorized into opaque and transparent sealants [13].

The differences in the properties between the materials make the decision making difficult for the practitioner. Therefore, the choice of the appropriate pit and fissure sealants should be based on the patient’s age and behavior, and the timing of the tooth’s eruption [13]. Although RBSs are effective in caries prevention, they are moisture sensitive [14]. Therefore, when a tooth can’t be isolated or is partially erupted, a GI sealant is an alternative choice due to its moisture-tolerance property [15]. Several studies found that the RBS compete with the GI sealants in terms of long-term retention specifically when the application is performed in adequate isolation. However, the resin materials do not have the antibacterial properties and fluoride release that the GI sealants have [16,17]. Studies showed that the incorporation of remineralizing additives such as fluoride and calcium phosphate into RBSs may improve their therapeutic effect and caries prevention [18,19,20,21]. Therefore, the ideal pit and fissure sealants require good mechanical properties with antibacterial and remineralizing effects.

In the field of Dental Biomaterials, in vitro studies are helpful because they allow researchers to develop new materials and evaluate certain clinically relevant properties that may be difficult to evaluate otherwise. Consequently, this type of study may help in the evaluation of the materials’ properties before exposing patients to them and their possible side effects [22]. Thus, this systematic review aimed to summarize the findings of in vitro studies that assessed the remineralizing additives containing RBSs, in order to identify the remineralizing additives in RBSs and assess their remineralizing performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

The Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analysis were followed in this review [23]. A pre-determined, unpublished review protocol was used. The review question was “What are the remineralizing effects of RBSs that incorporate remineralizing additives in their compositions?”

2.2. Search Strategy

Comprehensive search strategies for four electronic databases were developed and performed by three authors (M.I.A., M.S.A. and M.S.I.). On 1 June 2020, PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS and OVID were queried for published records regardless of their language and date. The four searches resulted in a total of 4920, 2626, 2039, and 2518 potentially relevant references. The search strategies were explained in detail in a previously published review from group [24]. The databases were searched for keywords, text words and subject terms related to the remineralization effects of RBS.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The articles included in this review were in vitro studies that assessed the remineralization activities of RBS either by microhardness tests, micro-computed tomography or polarized-light microscopy (lesion depth). Moreover, studies that assessed ion-releasing ability and acid neutralization by pH changes were included. Meanwhile, studies that were not laboratory studies, intervention other than sealants, studies that did not have an RBS, studies that only assessed resin-modified glass ionomers, and studies that didn’t assess remineralizing activities were excluded.

2.4. Study Screening and Selection

The screening process was performed by three independent reviewers who were not blind to the identity of the authors or journal of the studies. The procedure included a title and abstract screening, then a full-text screening. A senior reviewer resolved disagreements among the reviewers (M.S.I.).

2.5. Data Extraction

The data were extracted by two independent reviewers using a customized data collection form. Qualitative and quantitative data were extracted from the included studies. The following data were extracted: details of the studied materials, sample size per group, sample type, curing type, remineralizing agent, and control and intervention groups. The outcomes including microhardness, lesion depth, acid neutralization and ion-releasing ability were also extracted.

2.6. Quality Assessment

The studies were assessed for their methodological quality by two independent reviewers (M.I.A. and M.S.I.) using a well-accepted quality assessment tool adapted from several published studies [25,26]. The sampling bias was appraised by assessing whether a study reported the sample size, and whether the samples underwent preparation and randomization. The sample preparation was reported when the study mentioned how the samples were cleaned and prepared. Moreover, the assessment bias was appraised by assessing whether a study had a control group, blind examiners, and more than one assessment method. The reporting bias was described when the study didn’t mention definitive values after the outcome measurements. However, in a study that utilized only qualitative measurement methods, the definitive value was not applicable. The studies were considered to have a low risk of bias when they contained one to three parameters. Studies containing four to five parameters were considered to have a medium risk of bias. Meanwhile, there was a high risk of bias when the studies had six to seven parameters.

2.7. Data Synthesis

Qualitative summaries of the included studies’ characteristics, assessment methods and findings were planned to be reported. A meta-analysis was planned to be conducted if no methodological heterogenicity or interventional heterogeneity were found.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

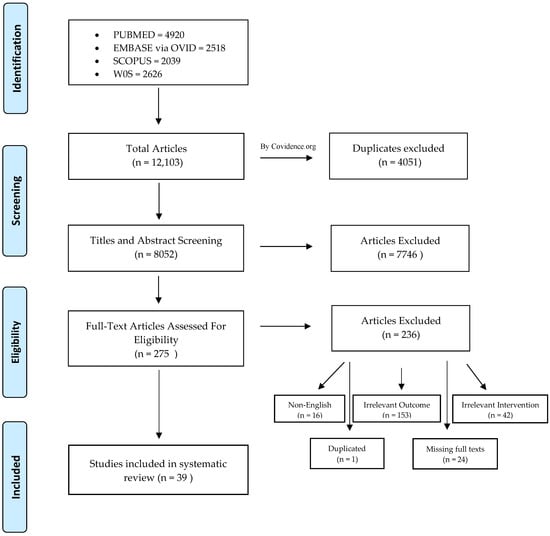

From the four databases (PubMed, OVID, SCOPUS and WOS), 12,103 studies were identified as being potentially relevant. Duplicated studies were removed. Thus, 8052 studies remained for the title and abstract screening. After the determination of the inclusion criteria and abstract screening, 7746 articles were excluded. Two hundred and fifty-seven studies were assessed for eligibility and full-text screening. A total of 39 in vitro studies that focused on the remineralizing activity of resin-based materials were included in this systematic review. This process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study screening and selection.

3.2. Risk of Bias Appraisal

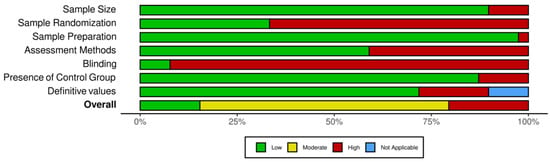

Most of the included studies showed a moderate risk of bias overall (Table 1). Only six studies out of the thirty-nine included studies were judged to have a low risk of bias [27,28,29,30,31,32] (Table 2). Randomization and blinding were not reported in most of the included studies, leading to a positive risk of bias (Figure 2). Almost all of the included studies reported the sample size per group and the sample preparation details.

Table 1.

Risk of bias appraisal.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 2.

Overall risk of bias for each parameter.

3.3. Study Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the 39 included studies. In general, the sample type was varied between the use of human non-carious teeth or samples made from the tested materials. Generally, most of the studied materials were light-cured, except for a few studies which used chemically cured materials [18,28,39,42,56,58,60]. The remineralizing agents in the tested materials included F, amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP), bioactive glass, strontium (Sr), hydroxyapatite (HAP), calcium silicate (CS), boron nitride nanotubes (BNNT), and calcium phosphate (CaP). The studies assessed the remineralizing abilities of the sealants using different methods, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis, polarized light microscopy analysis, and the measurement of the hardness change, surface roughness, acid neutralization, ion release, and lesion depth. Some studies assessed the general material properties, such as the flexural strength, curing depth, degree of conversion, surface free energy and color.

3.4. Remineralization Findings

Seven studies assessed the remineralizing abilities of the tested materials by measuring the hardness change [19,28,29,32,33,52,57]. There was a variation in the pH cycling method. Three studies used a 5-day cycle [28,32,33], one study used a 20-day cycle [52], and one study used a 4-day cycle [19] for pH cycling. All of the included studies that assessed the hardness change showed a significant difference between the remineralizing sealants and the non-remineralizing sealants, except for two studies [19,32]. However, when the hardness was measured only for the material without measuring the baseline and the change in the hardness, it was considered a physical property, and was not included in this review. Furthermore, the reminreliaizng abilities was assessed using SEM-EDX analysis in two studies [33,44], and seven studies used SEM imaging [20,27,35,36,48,51,54]. There was a variation in the results between the studies. Some of the studies showed that there were significant differences, and some showed no significant differences in the remineralizing abilities of the tested materials. Moreover, only six studies used PLM to assess the remineralizing abilities [30,31,33,37,45,57]. nACP containing a sealant, Pro-seal, Guardian SealTM, Fuji VIITM and GC Fuji Triage sealants showed a thinner enamel lesion. Moreover, only two studies assessed the remineralization using surface roughness. The BNNT-containing sealants and Clinpro sealants showed significantly lower roughness than the control groups [35,58]. Lastly, acid neutralization was used in two studies to measure the remineralization potential. The incorporation of CS, hCS and BAG into the RBS showed significantly higher acid-neutralization abilities [34,47]. A summary of the remineralization findings is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Remineralization ability findings.

3.5. Ions Release Findings

Out of the 39 included studies, almost 23 studies assessed F ion release. Mostly, the studies showed that the F stopped releasing or declined dramatically after a few days (7–9 days), which indicates a short-term release. Furthermore, it was observed that the GI-based sealants released more F than the RBS. Besides F, Ca and P ion release was assessed in a few studies, and it was observed that the release of these ions lasted longer than the F (21–70 days) [27,34,40]. Furthermore, a few studies assessed Sr, sodium (Na), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si) and boron (B) ion release [49,51]. It was noticed that these ions’ release was significantly high in the bioactive RBS (BeautiSealant) [20,38,43,49,51]. Nevertheless, one study reported that BeautiSealant released the lowest amount of fluoride [18], and another study stated that there was no significant difference between BeautiSealant and Teethmate F-1 sealants [20]. A summary of the ion release outcome findings is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ion release findings.

4. Discussion

Remineralizing agents have been incorporated into the composition of RBSs in order to improve their therapeutic bioactivity. This review included 39 laboratory in vitro studies that assessed the remineralization abilities of RBSs. The aim of this review was to map and summarize these studies, in order to help future in vitro studies to establish uniform laboratory protocols, and to translate the knowledge from the bench to the clinic.

Eight out of the thirty-nine included studies showed a high risk of bias, twenty-five showed a moderate risk of bias, and only six studies showed a low risk of bias. In general, it was observed that there were deficiencies in the areas of randomization and blinding. Randomization is well known in elimination bias through the use of the probability theory, and in maintaining a certain level of sample blinding [62]. It is suggested that future studies control these types of bias by using randomization and blinding whenever they are possible.

Different remineralizing agents were incorporated into the RBSs in order to improve their therapeutic bioactivity. Out of 39 studies, 32 studies focused on F as a remineralizing agent. Furthermore, bioactive glass, ACP, Sr, HAP, CS, BNNT and CaP were incorporated into RBSs. The effectiveness of F and CaP on enamel remineralization was confirmed in most of the included studies. BNNT and CS, on the other hand, had a small or insignificant effect on remineralization [34,35]. This notwithstanding, more laboratory studies are needed in order to confirm their effectiveness. Furthermore, most of the included studies focused on the short-term effects of these additives. Hence, studies with a longer experimental period may improve the understanding of the long-term effects of these additives.

Two of the included studies used bovine teeth [28,35], and fourteen studies used human teeth to assess the ion release and remineralizing abilities of the studied sealants. The majority used resin discs. The main concern with these findings is that in vitro results may be overestimated or underestimated in terms of their ion release and remineralizing abilities when compared to clinical performance in the dynamic oral environment.

Beyond the fact that most studies included control groups, seven studies did not include any control group (Table S1). Although they frequently produce predictable results, they are an important component of all experiments. Generally, there are two types of control groups: negative and positive controls. The negative control group is expected to demonstrate what occurs when the intervention is not applied. On the other hand, the positive control group is the one that is not subjected to the experimental treatment but is instead exposed to another treatment that is known to have a similar effect to the experimental treatment. When the control groups are used correctly, they not only validate the experiment but also offer the foundation for the analysis of the effect of the applied treatments [63]. Hence, they must be treated as any other experimental group in terms of preparation, randomization, blinding and other factors. It is recommended for future studies aiming to evaluate the remineralizing additives in RBSs to use both types of control groups. The positive control group will help as a benchmark for the effectiveness of the experimental treatment. In this vein, studies with this type of control group will aid us in the comparison of the effectiveness of the new RBSs with the conventional ones. Furthermore, the negative control group will help in the determination of the efficacy of the new RBSs in comparison to a lack of treatment.

Most of the included studies did not mention the sample size calculation. Researchers often use previous studies to determine the sample size, with little critical thinking regarding the sample calculation. However, it is critical to optimize the sample size, as it affects the power and impact of the study. For instance, a limited sample size can reduce the statistical power and lead to a type-II error (a false-negative), which occurs when the hypothesis test fails to reject a null hypothesis that is truly false. Furthermore, the larger the sample size, the more time and money is wasted [64]. Therefore, the researchers must be aware of its importance, and a scientific approach must be used to obtain it.

There are multiple qualitative and quantitative assessment methods that can be used to assess the remineralizing activities of resin-based dental sealants, such as tooth samples’ hardness change, SEM-EDX analysis, PLM imaging, lesion depth, and ion release assessment. The included studies showed some variations in this area. Sixteen of the included studies performed only one assessment, while the rest of the studies used more than one assessment to confirm their results. Hence, the use of multiple assessment methods is suggested in order to support the result of each tested materials with a different assessment.

PLM is a qualitative analysis of the mineral contents in the enamel lesions. The change in the backscatter for the enamel can be related to the chemically determined mineral loss [33,65]. As the included studies in this review used PLM to assess the lesions’ depth before and after the application of the sealants, smaller enamel lesions were found in the images when remineralizing sealants were used. This explains why a small amount of demineralization happens on the enamel surface. However, it should be recommended that PLM imaging must be accompanied by a quantitative analysis, such as SEM-EDX [31] or atomic absorption spectroscopy [66], in order to gain a clear description of the mineral volume.

The results showed that the sealants which had remineralizing agents in their compositions had a lower hardness change when compared to the non-remineralizing sealants. However, the protocols to create the lesions may actually affect the material’s performance [33]. The included studies had a maximum of 20 days of pH cycling. How will the performance be affected if the period exceeded that period? Will the materials be able to perform the same, or will we notice a decrease in the surface hardness? As such, we suggest that future studies assess the performance of remineralizing sealants in a longer pH-cycling process in order to ensure the long-term effect of the remineralization.

There was a diversity in the results of the remineralizing abilities when SEM-EDX analysis was used. SEM with EDX analysis is a quantitative analysis used to observe the material elements in a high-resolution image. One of the included studies [33] assessed the mineral content of teeth treated with different types of sealants after pH-cycling. It used PLM, which showed less demineralization around the enamel, and then it supported the results by SEM-EDX, which showed higher calcium and phosphate levels in the enamel.

In this review, an ion release test was performed in more than half of the included studies (26 studies). It was observed that the protocol varied between the studies (Table S2). The variations were observed in the immersion solution, the immersion time, and the pH of the solution. For instance, one study immersed the samples for only 1 day [51], while one study reached up to 180 days [60]. Furthermore, some studies used lactic acid as an immersion solution [34,56]. However, most of the studies used distilled water. These variations may affect the ion release findings. Therefore, standardization in the protocol is recommended in future studies in order to make fair comparisons between the studies.

The prolonged release of remineralizing ions over time from the sealant is required in order to optimize the probability of caries prevention, particularly in individuals at a high risk of caries [67]. Notwithstanding the foregoing, in almost all of the studies, the highest amount of fluoride release was observed on the first day, and then trended to decrease dramatically with time, which indicates a short-term effect. However, Ca and P ions showed longer promising effects regarding ion release [27,34,40]. Due to the fact that fluoride has a short-term release that decreases over time, recharging the dental materials with fluoride has been suggested as a way to maintain a constant amount of fluoride release [68,69]. However, only a few studies [18,32,39,41,46,49,53,61] assessed the fluoride recharging abilities of these sealants. Hence, it is suggested that we perform more studies to confirm the benefits of recharging in these sealants. Furthermore, the incorporation of other remineralizing agents that have longer promising effects, such as those containing Ca and P ions, could be another solution.

Only one of the new, commercially available, bioactive RBSs (BeautiSealant) was studied in the included in studies [18,20,38,43,49,51]. It was observed that this bioactive RBS released multiple ions, such as Na, Sr, Al, Si and B, which contributed to its strong enamel remineralization effect [49,51]. However, it is recommended that we study the other new bioactive dental sealants which have recently been introduced to the dental market in both laboratory and clinical studies.

After the qualitative analysis of the included studies, it was not possible to conduct a quantitative analysis. A meta-analysis was not conducted due to the methodological heterogeneity between the included studies. The careful interpretation of these results is recommended due to the variations of the studies’ settings, experimental protocols and assessment methods.

5. Conclusions

In summary, according to the findings of the included in vitro studies, the incorporation of remineralizing agents into RBSs may have promising remineralizing effects which may enhance the therapeutic effect of these sealants. However, this effect seems to diminish over time, and recharging via mouthwashes or toothpastes that contain remineralizing agents may be necessary in order to prolong the effect. For more homogenous studies and a lower risk of bias, a standardized protocol to follow while attempting an in vitro study is recommended.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polym14040779/s1, Table S1: The details of the control and intervention groups of all included studies, Table S2: The details of the protocol of all included studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.I.; methodology, M.I.A., M.S.A. and M.S.I.; covidence software, M.I.A., M.S.A., M.A.A. and M.S.I.; validation, M.S.I. and J.A.; formal analysis (data extraction), M.I.A., M.S.A., J.A.A. and M.A.A.; resources, M.S.I.; data curation, M.I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.A. and J.A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.S.I. and J.A.; visualization, M.I.A. and M.S.I.; supervision, M.S.I.; project administration, M.I.A.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators; Bernabe, E.; Marcenes, W.; Hernandez, C.R.; Bailey, J.; Abreu, L.G.; Alipour, V.; Amini, S.; Arabloo, J.; Arefi, Z.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Burden of Oral Conditions from 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Featherstone, J. Dental caries: A dynamic disease process. Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejerskov, O.; Nyvad, B.; Kidd, E. Dental Caries: The Disease and Its Clinical Management, 3rd ed.; Black Well Munksgaard: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cate, J.M.T. Current concepts on the theories of the mechanism of action of fluoride. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1999, 57, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Featherstone, J.D.B. The Continuum of Dental Caries—Evidence for a Dynamic Disease Process. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83 (Suppl. S1), C39–C42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J.R.; Kowolik, J.E.; Stookey, G.K. Dental Caries in the Child and Adolescent. In McDonald and Avery’s Dentistry for the Child and Adolescent, 10th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2016; pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.G.; Mass, W.R.; Malvitz, D.M.; Presson, S.M.; Shaddix, K.K. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2001, 50, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Khetani, P.; Sharma, P.; Singh, S.; Augustine, V.; Baruah, K.; Thumpala, K.V.; Tiwari, R.V.C. History and Selection of Pit and Fissure Sealants–A Review. J. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2017, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.J.; Christensen, J.R.; Mabry, T.R.; Townsend, J.A.; Wells, M.H. Pediatric Dentistry, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Chapter 12; pp. 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto, E.I.; Buonocore, M.G. Sealing of pits and fissures with an adhesive resin: Its use in caries prevention. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1967, 75, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R.L. Method of Preparing a Monomer Having Phenoxy and Methacrylate Groups Linked by Hydroxy Glyceryl Groups. U.S. Patent Application No. US119748A, 20 April 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, A.; Gallegos, I.T.; Felix, C.M. Photoinitiators in Dentistry: A Review. Prim. Dent. J. 2013, 2, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaman, R.; El-Housseiny, A.A.; Alamoudi, N. The use of pit and fissure sealants-a literature review. Dent. J. 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstone, L.M.; Hicks, M.J.; Featherstone, M.J. Oral fluid contamination of etched enamel surfaces: An SEM study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1985, 110, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsatto, M.C.; Corona, S.A.M.; Alves, A.G.; Chimello, D.T.; Catirse, A.B.E.; Palma-Dibb, R.G. Influence of salivary contamination on marginal microleakage of pit and fissure sealants. Am. J. Dent. 2004, 17, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ulusu, T.; Odabaş, M.E.; Tüzüner, T.; Baygin, Ö.; Sillelioğlu, H.; Deveci, C.; Gökdoğan, F.G.; Altuntaş, A. The success rates of a glass ionomer cement and a resin-based fissure sealant placed by fifth-year undergraduate dental students. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 13, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsabek, L.; AlNerabieah, Z.; Bshara, N.; Comisi, J.C. Retention and remineralization effect of moisture tolerant resin-based sealant and glass ionomer sealant on non-cavitated pit and fissure caries: Randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Dent. 2019, 86, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionysopoulos, D.; Sfeikos, T.; Tolidis, K. Fluoride release and recharging ability of new dental sealants. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 17, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawaideh, F.I.; Owais, A.I.; Kawaja, W. Ability of Pit and Fissure Sealant-containing Amorphous Calcium Phosphate to inhibit Enamel Demineralization. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 9, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Abe, S.; Minamikawa, H.; Yawaka, Y. Effect of fluoride-releasing fissure sealants on enamel demineralization. Pediatr. Dent. J. 2017, 27, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosior, P.; Dobrzyński, M.; Korczyński, M.; Herman, K.; Czajczyńska-Waszkiewicz, A.; Kowalczyk-Zając, M.; Piesiak-Pańczyszyn, D.; Fita, K.; Janeczek, M. Long-term release of fluoride from fissure sealants—In vitro study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 41, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulet, J.F. Is in vitro research in restorative dentistry useless? J. Adhes. Dent. 2012, 14, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShahrani, S.S.; AlAbbas, M.A.S.; Garcia, I.M.; AlGhannam, M.I.; AlRuwaili, M.A.; Collares, F.M.; Ibrahim, M.S. The Antibacterial Effects of Resin-Based Dental Sealants: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Materials 2021, 14, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.; Salloot, Z.; Alshaia, A.; Ibrahim, M.S. The Effect of Bioactive Glass-Enhanced Orthodontic Bonding Resins on Prevention of Demineralization: A Systematic Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Balhaddad, A.A.; Weir, M.D.; Lin, N.J.; Tay, F.R.; Oates, T.W.; Xu, H.H.K.; Melo, M.A.S. A Novel Dental Sealant Containing Dimethylaminohexadecyl Methacrylate Suppresses the Cariogenic Pathogenicity of Streptococcus mutans Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utneja, S.; Talwar, S.; Nawal, R.R.; Sapra, S.; Mittal, M.; Rajain, A.; Verma, M. Evaluation of remineralization potential and mechanical properties of pit and fissure sealants fortified with nano-hydroxyapatite and nano-amorphous calcium phosphate fillers: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2018, 21, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ei, T.Z.; Shimada, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Romero, M.J.R.H.; Sumi, Y.; Tagami, J. Comparison of resin-based and glass ionomer sealants with regard to fluoride-release and anti-demineralization efficacy on adjacent unsealed enamel. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantovitz, K.R.; Pascon, F.M.; Nociti, F.H.; Tabchoury, C.P.M.; Puppin-Rontani, R.M. Inhibition of enamel mineral loss by fissure sealant: An in situ study. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basappa, N.; Raju, O.; Dahake, P.T.; Prabhakar, A. Fluoride: Is It Worth to be added in Pit and Fissure Sealants? Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2012, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, D.V.; García-Godoy, F.; Flaitz, C.M.; Hicks, M.J. Potential inhibition of demineralization in vitro by fluoride-releasing sealants. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 138, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, M.M.; Pecharki, G.D.; Tengan, C.; da Silva, D.D.; Tagliaferro, E.P.D.S.; Napimoga, M.H. Fluoride-releasing capacity and cariostatic effect provided by sealants. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 47, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Balhaddad, A.A.; Garcia, I.M.; Collares, F.M.; Weir, M.D.; Xu, H.H.; Melo, M.A.S. pH-responsive calcium and phosphate-ion releasing antibacterial sealants on carious enamel lesions in vitro. J. Dent. 2020, 97, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Choi, J.-W.; Kim, K.-M.; Kwon, J.-S. Prevention of Secondary Caries Using Resin-Based Pit and Fissure Sealants Containing Hydrated Calcium Silicate. Polymers 2020, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohns, F.; DeGrazia, F.W.; de Souza Balbinot, G.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Samuel, S.M.W.; García-Esparza, M.A.; Sauro, S.; Collares, F.M. Boron Nitride Nanotubes as Filler for Resin-Based Dental Sealants. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohns, F.R.; Leitune, V.C.B.; de Souza Balbinot, G.; Samuel, S.M.W.; Collares, F.M. Mineral deposition promoted by resin-based sealants with different calcium phosphate additions. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrabad, Z.K.; Safari, E.; Alavi, M.; Shadkar, M.M.; Naghavi, S.H.H. Effect of a fluoride-releasing fissure sealant and a conventional fissure sealant on inhibition of primary carious lesions with or without exposure to fluoride-containing toothpaste. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2019, 13, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şişmanoğlu, S. Fluoride Release of Giomer and Resin Based Fissure Sealants. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2019, 21, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudanov, B.O.; Abdullaev, J.R.; Bottenberg, P.; Schulte, A.G. Evaluation of the Fluoride Releasing and Recharging Abilities of Various Fissure Sealants. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2018, 16, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; AlQarni, F.D.; Al-Dulaijan, Y.A.; Weir, M.D.; Oates, T.W.; Xu, H.H.K.; Melo, M.A.S. Tuning Nano-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Content in Novel Rechargeable Antibacterial Dental Sealant. Materials 2018, 11, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surintanasarn, A.; Siralertmukul, K.; Thamrongananskul, N. Fluoride Recharge Ability of Resin-Based Pit and Fissure Sealant with Synthesized Mesoporous Silica Filler. Key Eng. Mater. 2017, 751, 586–591. [Google Scholar]

- Munhoz, T.; Nunes, U.T.; Seabra, L.M.-A.; Monte-Alto, R. Characterization of Mechanical Properties, Fluoride Release and Colour Stability of Dental Sealants. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clínica Integr. 2016, 16, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scougall-Vilchis, R.J.; Salmerón-Valdés, E.N.; Alanis-Tavira, J.; Morales-Luckie, R.A. Comparative study of fluoride released and recharged from conventional pit and fissure sealants versus surface prereacted glass ionomer technology. J. Conserv. Dent. 2016, 19, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli-Hojjati, S.; Atai, M.; Haghgoo, R.; Rahimian-Imam, S.; Kameli, S.; Ahmaian-Babaki, F.; Hamzeh, F.; Ahmadyar, M. Comparison of Various Concentrations of Tricalcium Phosphate Nanoparticles on Mechanical Properties and Remineralization of Fissure Sealants. J. Dent. Tehran Univ. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 379–388. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Haffiez, S.H.; Zaher, A.R.; Elharouny, N.M. Effects of a filled fluoride-releasing enamel sealant versus fluoride varnish on the prevention of enamel demineralization under simulated oral conditions. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2013, 2, e133–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Townsend, J.; Wang, Y.; Lee, E.C.; Evans, K.; Hender, E.; Hagan, J.L.; Xu, X. Formulation and characterization of antibacterial fluoride-releasing sealants. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2013, 35, 13E–18E. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Piao, Y.-Z.; Kim, S.-M.; Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, K.-N.; Kim, K.-M. Acid neutralizing, mechanical and physical properties of pit and fissure sealants containing melt-derived 45S5 bioactive glass. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Ganesh, M.; Tandon, S.; Mehra, A. Evaluation of the remineralization potential of amorphous calcium phosphate and fluoride containing pit and fissure sealants using scanning electron microscopy. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2012, 23, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, K.; Ogata, K.; Karibe, H. Evaluation of the ion-releasing and recharging abilities of a resin-based fissure sealant containing S-PRG filler. Dent. Mater. J. 2011, 30, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaga, M.; Masuta, J.; Hoshino, M.; Genchou, M.; Minamikawa, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Yawaka, Y. Mechanical Properties and Ions Release of S-PRG Filler-containing Pit and Fissure Sealant. Nano Biomed. 2011, 3, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kaga, M.; Kajiwara, D.; Minamikawa, H.; Kakuda, S.; Hashimoto, M.; Yawaka, Y. Ion Release and Buffering Capacity of S-PRG Filler-containing Pit and Fissure Sealant in Lactic Acid. Nano Biomed. 2011, 3, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaffar, A.; Tantbirojn, D.; Versluis, A.; Beiraghi, S. Protective effect of pit and fissure sealants on demineralization of adjacent enamel. Pediatric Dent. 2011, 33, 491–495. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak, S.; Tunc, E.S.; Aksoy, A.; Ertas, E.; Guvenc, D.; Ozer, S. Fluoride Release and Recharge from Different Materials Used as Fissure Sealants. Eur. J. Dent. 2010, 4, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, N.-Z.; Anusavice, K.J. Fluoride and Chlorhexidine Release from Filled Resins. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuşgöz, A.; Tüzüner, T.; Ülker, M.; Kemer, B.; Saray, O. Conversion degree, microhardness, microleakage and fluoride release of different fissure sealants. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2010, 3, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, J.; Furukawa, S.; Shimoda, S.; Tsurumoto, A. Transition of Fluoride into Tooth Substance from Sustained Fluoride-Releasing Sealant-In vitro Evaluation. J. Hard Tissue Biol. 2010, 19, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, K.G.; Pedrini, D.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Ferreira, L.; Cannon, M. In situ evaluation of the remineralizing capacity of pit and fissure sealants containing amorphous calcium phosphate and/or fluoride. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2009, 68, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildir, S.K.; Sandalli, N. Compressive strength, surface roughness, fluoride release and recharge of four new fluoride-releasing fissure sealants. Dent. Mater. J. 2007, 26, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola-Rodriguez, J.P.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Antibacterial activity of fluoride release sealants on mutans streptococci. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 1996, 20, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.W.; Shern, R.J.; Kennedy, J.B. Evaluation of an autopolymerizing fissure sealant as a vehicle for slow release of fluoride. Pediatr. Dent. 1984, 6, 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, M.; Phillips, R.; Norman, R.; Elliason, S.; Rhodes, B.; Clark, H. Addition of Fluoride to Pit and Fissure Sealants-A Feasibility Study. J. Dent. Res. 1976, 55, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithikadatta, J.; Datta, M.; Gopikrishna, V. CRIS Guidelines (Checklist for Reporting In-vitro Studies): A concept note on the need for standardized guidelines for improving quality and transparency in reporting in-vitro studies in experimental dental research. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, P. Out of Control? Managing Baseline Variability in Experimental Studies with Control Groups. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 257, pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordzij, M.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C.; Jager, K.J. Sample Size Calculations. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2011, 118, c319–c323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, R.; Soares, J.; de Sousa, F. Natural enamel caries in polarized light microscopy: Differences in histopathological features derived from a qualitative versus a quantitative approach to interpret enamel birefringence. J. Microsc. 2012, 246, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimuszko, E.; Orywal, K.; Sierpinska, T.; Sidun, J.; Gołębiewska, M. Evaluation of calcium and magnesium contents in tooth enamel without any pathological changes: In vitro preliminary study. Odontology 2018, 106, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, H.; Kameyama, A.; Matsukubo, T.; Hirai, Y.; Takaesu, Y. Comparison of short-term in vitro fluoride release and recharge from four different types of pit-and-fissure sealants. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2004, 45, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A.J.; Higham, S.M.; Agalamanyi, E.A.; Mair, L.H. Fluoride recharge of aesthetic dental materials. J. Oral Rehabil. 1999, 26, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Cv, E.; Li, M.; Niwano, K.; Ab, N.; Okamoto, A.; Honda, N.; Iwaku, M. Effect of Fluoride Mouth Rinse on Fluoride Releasing and Recharging from Aesthetic Dental Materials. Dent. Mater. J. 2002, 21, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).