Abstract

We report the structures and the nonresonant Raman spectra of hybrid systems composed of carbon fullerenes ( and ) encased within single walled boron nitride nanotube. The optimal structure of these systems are derived from total energy minimization using a convenient Lennard-Jones expression of the van der Waals intermolecular potential. The Raman spectra have been calculated as a function of nanotube diameter and fullerene concentration using the bond polarizability model combined with the spectral moment method. These results should be useful for the interpretation of the experimental Raman spectra of boron nitride nanotubes encasing and fullerenes.

1. Introduction

The discovery of nanomaterials such as fullerenes [1], carbon nanotubes [2] and boron nitride nanotubes [3] prevails over science and technology at nanoscale levels and becomes a hot topic for researchers and industrialists. Single walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) filled with fullerenes are commonly called carbon peapods (). They have been firstly synthesized by Smith et al. in 1998 [4] and exhibit special physical properties with different potential applications [5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

Similar to SWCNTs, single walled boron nitride nanotubes (SWBNNTs) can also be filled with fullerene molecules such as and : they are so-called boron nitride peapods ( where 60 or 70). The system was first theoretically proposed by Okada et al. [12] and experimentally synthesized two years later [13,14]. This system has aroused great interest in BN peapods as an ideal model to study the atoms or molecules in 1D confined conditions [13,15]. Due to its unusual electronic structure, the is an interesting candidate to study a possible superconducting state.

It was theoretically stated [15,16,17] that (i) inside SWBNNT is energetically more stable and achieved faster than inside SWCNT and (ii) the suction force on the induced by SWBNNTs is higher than that induced by the SWCNTs [12,16]. The - intermolecular distance inside the SWBNNT is 0.9 nm [13,18], which is slightly smaller than the 1.0 nm intermolecular distance for carbon peapods [5,19]. This difference could be due to a stronger van der Waals attraction between the SWBNNT and the or possibly to commensurability effects [13,18]. Moon et al. [20] have demonstrated from molecular dynamics simulation that the (10,10) and (17, 0) SWBNNTs are the most favorable for encapsulation of molecules. Mickelson et al. [13] have shown that the ’s structure inside SWBNNTs is dependent of the tube diameter, as in the case of [21,22,23,24]. Compared to other nanostructures, nanopeapods have opened new applications such as storage materials with high capacity and stability [10,25] and considered to be potential materials for high-temperature superconductors [11]. The space inside the nanotube can be also regarded as a nanometer-sized container for chemical reactions [7].

Raman spectroscopy is the standard characterization technique for nanotubes. Raman spectrum of C@SWBNNT have been reported in the literature at different laser energies (488, 568 and 647 nm) [14]. All fundamental Raman lines of the encapsulated peas are observed and a structured peak at 268, 330, 355 and 466 cm is measured and assigned to the reaction products of the carbon fullerenes inside the BN nanotubes. The authors show that the radial breathing mode range reveals new spectral features which are not observed in the case of unfilled BN tubes.

The experimental Raman spectra measured on BN peapods are complex to analyze because experiments performed on macroscopic samples consist of a mixture of bundles of tubes of different diameters and chiralities. In this paper, in order to improve the comparison between the calculations and experimental data, we investigate theoretically the fullerene-fullerene and fullerene-tube interactions effect on the vibrations of and BN peapods. In contrast with molecules, the ellipsoidal shape of leads both the - and -SWBNNT interactions to be anisotropic. As a consequence, the electronic structure and the ground state energy of fullerene peapods depend on the configuration of the fullerene molecules inside the nanotubes. The analysis of the Raman spectra of peapods suggests that the observed shifts of the radial breathing mode (RBM) could be explained by a small increase of the tube diameter, resulting from the interaction between -electrons of the fullerene with the interior of the nanotube [26].

In previous works [23,27,28], we studied the different possible configurations of C and C molecules encapsulated into SWCNTs with diameter lower than 2.28 nm. Raman spectra of carbon peapods have been calculated for C linear, zigzag, double helix and layer of two molecules configurations within the bond-polarizability model. Our results were in qualitative agreement with the experimental ones. Here, we continue these studies in the case where the and molecules are now encapsulated into SWBNNTs. Our work addresses new questions as to the influence of the nanotube diameter and the and filling rate. In this context, we use a direct diagonalization of the dynamical matrix for small peapods (few hundred atoms) and the spectral moment method for larger ones. We report the structural organization of the C@SWBNNT and C@SWBNNT as a function of the diameter and the chirality of the BN nanotubes and we discuss the change in the Raman response of these hybrid systems including the influence of the fullerene concentration.

2. Models and Simulation Method

2.1. Structure and Dynamics of C@SWBNNT and C@SWBNNT Peapods

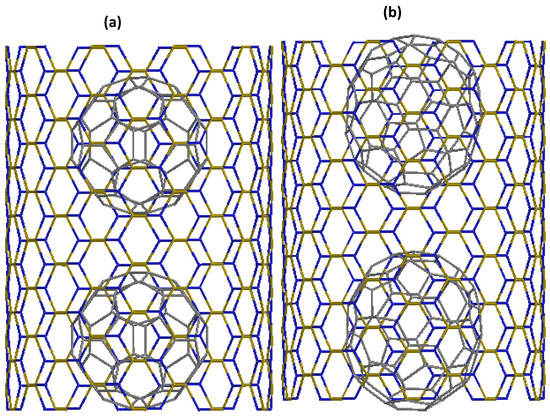

SWBNNTs are obtained by rolling a single hexagonal boron nitride sheet [29,30] and can be specified by integers (n, m) which define the translation vector between two equivalent points. A BN peapod consists of fullerene molecules trapped inside a SWBNNT host. Depending on the nanotube diameter, different configurations of and can certainly exist. Here, we restrict our study by considering only a linear chain of and confined inside SWBNNT. Considering a (10,10) SWBNNT, Figure 1 shows the structures of the encapsulated C and C. The configuration of the guest and molecules inside SWBNNTs is derived from total energy minimizations according to the procedure described in our previous works on carbon peapods [23].

Figure 1.

Structure of two SWBNNT peapods: (a) @(10,10) and (b) @(10,10).

The C-C interaction between carbon atoms belonging to non-bonded fullerenes, and between fullerenes and the surrounding nanotube, are represented by the Lennard-Jones potential, . For boron, nitrogen and carbon atoms, the -parameter is 0.004116, 0.006281 and 0.002635 eV, whereas the -parameter is 0.3453, 0.3365 and 0.3369 nm, respectively [16,31]. The parameters and between different atoms are calculated by the following Lorentz-Berthelot rules: and .

The intratube interactions at the surface of the SWBNNT are described by the same force constant model we recently used in the calculations of the infrared spectra of single walled boron nitride nanotubes [32]. The C-C intramolecular interactions between carbon atoms at the surface of molecules are modelized by the force constants model described by Jishi and Dresselhaus [33]. Interactions up to the fourth nearest neighbors are accounted to derive the dynamical matrix. The dynamical matrix of free molecule was calculated using the density functional theory (DFT) as implemented inside the SIESTA package [34]. The dynamical matrix (leading to the frequency of the Raman lines) is calculated by block using the previous intramolecular potentials and van der Waals potential (i.e., fullerene-SWBNNT and fullerene-fullerene interactions).

2.2. Methods

The time-averaged power flux of the Raman scattered light in a given direction, with a frequency between and within a solid angle , is related to the differential scattering cross section:

where

and is the Raman shift. In these equations, (i,j,k,l)-indices denote the Cartesian components, the star symbolizes the complex conjugation, c is the speed of light in the medium, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, (resp. ) is the frequency of incident (resp. scattered) light, (resp. ) is the polarization unit vector of the incident (resp. scattered) light, is the Bose factor, and is the frequency of the mth zone-center phonon mode. The Raman susceptibility tensor is defined as,

where the sum runs over all atoms and space directions , is the unit cell volume, is the () component of the mth phonon eigendisplacement vector, and is a third-rank tensor describing the changes of the first-order optical dielectric susceptibility () induced by individual atomic displacements. This latter quantity is defined as,

where corresponds to the displacement of the atom in the direction . As long as the phonon frequencies and eigendisplacements are known, is the central quantity to be determined to estimate Raman intensities. The first term of Equation (2), associated with the creation of a vibrational quantum, describes the Stokes scattering with a downshift in frequency . The second term, related to an annihilation of a vibrational quantum, describes the anti-Stokes scattering with an upshift frequency . The mth mode is Raman active if one component of the Raman susceptibility tensor, , is nonnull.

The Raman intensities can be calculated within the framework of the nonresonant bond polarizability model [35]. In this model, we consider that the optical dielectric susceptibility () of the crystal can be decomposed into individual contributions, arising only from the polarizability () of bonds b between nearest-neighbor atoms,

and the polarizability of a particular bond b is assumed to be given by the empirical equation:

where is the unit vector along the bond b. The parameters and correspond to the longitudinal and perpendicular bond polarizability, respectively. A further assumption is that the parameters of this model are functions of the bond lengths r only, so that the derivative of the polarizability tensor with respect to the displacement of atom in direction is given by:

where , and is the equilibrium bond distance. The values of these -parameters are usually fitted with respect to the experiments [35].

Raman spectra are calculated using a direct diagonalization of the dynamical matrix for small samples (few hundreds atoms). When the system contains a large number of atoms, the dynamical matrix is very large and its diagonalization fails or requires long computing time. In contrast, the spectral moments method allows to compute directly the Raman spectrum of very large harmonic systems without any diagonalization of the dynamical matrix [36,37,38,39].

In all our calculations, the nanotube axis is along the Z-axis and a carbon atom is along the X-axis of the nanotube reference frame. The laser beam is kept along the Y-axis of the reference frame. We consider that both incident and scattered polarizations are along the Z-axis to calculate the ZZ-polarized spectra.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimized Structure of C@SWBNNT and C@SWBNNT

The optimal configuration of the inserted fullerene molecules inside the tube is calculated by minimizing the energy of the SWBNNT and - interactions described by the Lennard-Jones potential. Results are listed in Table 1 for tubes whose diameter is between 1.30 and 1.45 nm. The linear chain is the optimal configuration for the tubes having a diameter , where R is the fullerene radius and d is the interlayer -SWBNNT distance. The optimal - gap inside SWBNNTs is calculated around nm for all optimized peapods. This value is larger than the one observed by Zettl et al. [18] (≃0.89 nm). This difference could be due to a stronger van der Waals attraction between the nanotube and the .

Table 1.

Optimized structural parameters of the molecules inside SWBNNT in diameter range where the molecules adopt a linear chain inside nanotubes.

In contrast with molecules, the ellipsoidal shape of leads both the - and -SWBNNT interactions to be anisotropic. In our calculations, we considered a number of molecules initially placed such that their long axis was parallel to the nanotubes axis. The energy minimization of the different @SWBNNTs is performed for any molecular orientation characterized by three Euler angles (following the terminology used by Bradley et al. [40]). Only the rotation angle over the tube-axis can vary during our structural relaxation procedures. Thus, the optimum packing can be characterized by the degree of inclination : for lying orientation, for standing orientation and for tilted orientation. Our calculations show that this angle increases with the diameter of nanotubes (see Table 2) and no correlation is clearly observed between this angle and their chirality.

Table 2.

Optimized structural parameters of the molecules inside BNNT in diameter range where the molecules adopt a linear chain inside nanotubes.

3.2. Raman Spectra of Completely Filled Peapods

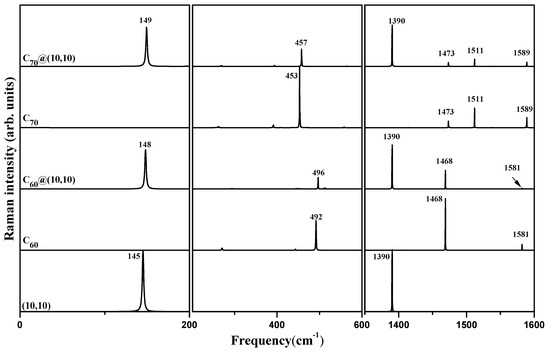

We study the Raman active modes in C@SWBNNTs and C@SWBNNTs. For this purpose, a peapod filled to saturation has been considered. The calculated ZZ-polarized Raman spectra of @(10,10) and @(10,10), with their corresponding unfilled (10,10) armchair SWBNNT (tube diameter close of 1.37 nm), and the unoriented and molecules are displayed in Figure 2. Raman lines can be divided into three frequency ranges: (i) below 200 cm where the breathing-like modes (BLM) dominate, (ii) an intermediate range between 200 and 600 cm, and (iii) above 1350 cm where the tangential-like modes (TLM) are located. Infinite peapods have been obtained by applying periodic conditions along the tube axis.

Figure 2.

Calculated ZZ-polarized Raman spectra of infinite @(10,10) and @(10,10) peapods. Spectra of infinite empty (10,10) SWBNNT, and molecules are also reported for references.

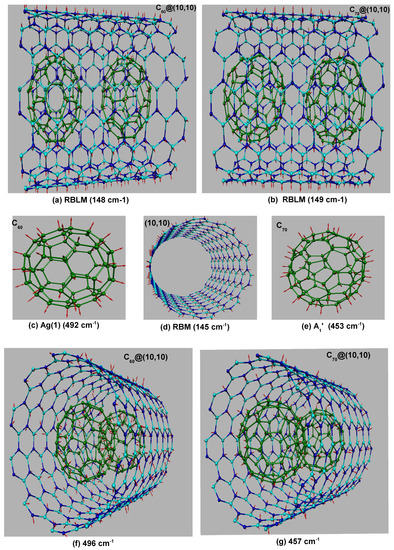

The main modes of the (10,10) SWBNNT, and the and molecules, are almost not affected by the encapsulation in the TLM region. Indeed, in this region, the position and the relative intensity of the Raman lines observed in peapods is a supperposition of the Raman lines of each of the sub-systems. For the BLM region, an upshift of the RBM of the tube is observed when the and molecules are encapsulated into the tube. For instance, the RBM of the unfilled (10,10) SWBNNT shifts from 145 cm in empty (10,10) to 148 and 149 cm in completely filled @(10,10) and @(10,10), respectively. In the two kinds of peapods, these modes are assigned to the radial breathing like mode (RBLM) of the tube where all atoms in the tube and in the surface of fullerene adjacent to the tube move in phase along the radial direction (see Figure 3a,b). In contrast, the atoms in adjacent surfaces of fullerenes move in counter-phase along the axial direction. In the intermediate range between 200 and 600 cm, only phonon modes of the and molecules can be observed. The line centered at 492 cm and assigned as the symmetric mode of shifts to 496 cm in @(10,10) peapod. Similarly, the line centered at 453 cm in and assigned as the symmetric mode shifts to 457 cm with the encapsulation. These calculated upshifts can be explained by the van der Waal intermolecular interactions acting between the fullerenes and the SWBNNTs. Concerning the atomic motions modified by the encapsulation, we displayed in Figure 3, the eigendisplacement vectors of these two Raman modes obtained in peapods (Figure 3f,g) from the direct diagonalization of the dynamical matrix, together with the RBM of the unfilled (10,10) SWBNNTs (Figure 3d) and the pure (Figure 3c) and (Figure 3e) molecules. We observe in peapods, a counter-phase coupled motion of the breathing modes of the encapsulated molecule and the tube, and all atoms of the and C molecules vibrate in-phase in the radial direction (see Figure 3f,g).

Figure 3.

Calculated atomic motions (eigendisplacement vectors) in , , (10,10) SWBNNT, @(10,10) and @(10,10). Arrows are proportional to the amplitude of the atomic motions.

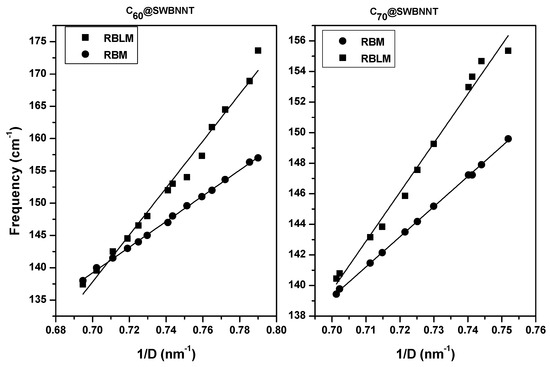

In the remainder of this paper, we focus on the low frequency range of the ZZ-polarized Raman spectrum of BN peapods. We investigated the dependence of some specific Raman active modes of infinite peapods as a function of the diameter of the nanotube. We already reported that the RBM is the most influenced mode by the nanotube filling. This mode is also the most appropriate for extracting structural and dynamical information of SWBNNT. A few years ago, we found [32,47], using the bond polarizability model combined with the spectral moments method, a relation for isolated tubes between their diameter D and their RBM frequency: , where 198 nm.cm. This relation was in agreement with the different approaches reported in the literature [48,49,50]. Figure 4 shows the RBM frequency in SWBNNTs and the RBLM frequency in @SWBNNTs and @SWBNNTs as a function of the inverse tube diameter. For the two kinds of peapods, the evolution of the RBLMs is qualitatively the same as those of the RBM: their frequencies decrease when the tube diameters increase. However, the RBLMs show deviation from the scaling law stated for the RBM frequency and this deviation is even more important when the diameter of the tubes is small (below 1.35 nm). Both for the peapods and peapods, we found that the frequency of the RBLM follows a law in with 363.6 nm.cm and −116.7 cm for peapods and 320.9 nm.cm and −85 cm for peapods.

Figure 4.

Calculated RBLM frequencies (squares) in isolated infinite nanopeapods and RBM (circles) frequencies in infinite isolated SWBNNTs. Only tubes with a diameter below 1.42 and 1.45 nm are considered for C@SWBNNT and C@SWBNNT, respectively.

3.3. Raman Spectra of Incompletely Filled Peapods

In real peapod samples, it is reasonable to consider that all the nanotubes are not completely filled with or and the highest filling rates range from 70 to 90% [51,52]. The exact degrees of filling is still under discussion and ranges from a certain percent to almost 100% filling. In this section, we make the hypothesis of partial filling of the tubes with a quasi infinite long chain. This hypothesis is supported by observations reported in Ref. [53]. Very long tubes are considered (more than 100 cells) and a defined number of molecules and are inserted. To avoid finite size effects, we applied periodic conditions along the tube axis.

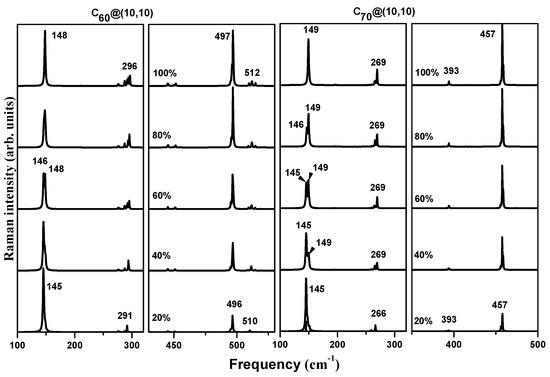

We found that the number of molecules inside the SWBNNT has no significant effect on the Raman spectrum except on the RBLM mode which is the most sensitive to the degree of filling of the SWBNNTs. Figure 5 displays the ZZ-polarized Raman spectra below 600 cm of C@(10,10) and C@(10,10) linear peapods as a function of their filling rate. Five values of the filling rate have been considered: F = 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100% corresponding to 2, 4, 8, 12 and 16 encapsulated molecules (C or C). We observe that all Raman lines undergo a frequency upshift more or less significant as the filling level increases. Similarly, the intensity of the C and C characteristic lines increases. A single RBLM peak characterizes all spectra for F = 20 and 100% of the filling factor. For F = 100% (tubes completely filled) the RBLM peak is located at 148 and 149 for @(10,10) and @(10,10) respectively and at 145 for F = 20% (low filling level). Let us call and the frequency of the heavy and light filling factor, the increase of Ffrom 20 to 100% leads to the appearance of two peaks at frequency close to and . The intensity of these peaks shifts from the one located around to that located around when increasing F. This last behaviour is observed for carbon peapods [54].

Figure 5.

ZZ-polarized Raman spectra in RBLM regions for infinite nanopeapods as a function of their filling rate: C@(10,10) (left) and C@(10,10) (right).

The lines at 291, 496 and 510 cm respectively upshifts to 296, 497 and 512 cm and increases in intensity from 20 to 100% for @(10,10). The same the lines centered at 266, 493 and 457 cm increases in intensity from 20 to 100% for@(10,10). The observed frequency shift can be associated with -SWBNNT, -SBNN, - and - van der Waals interaction effects.

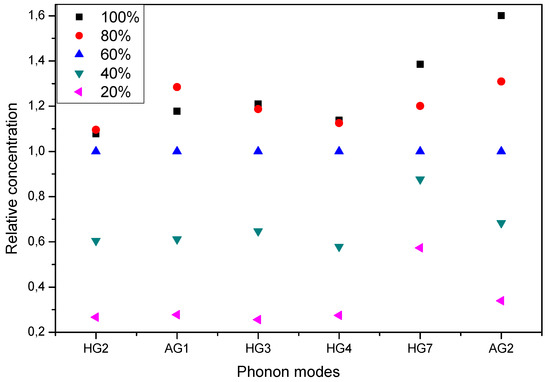

Using the spectral moment’s method, we investigate the evolution of the average nonresonant intensity ratios between Raman mode of molecules and BN nanotube as a function of the concentration of s inside the tubes. In the case of carbon peapods, we have found that the dependence of the Raman spectrum with the filling factor, the relative intensity ratio between a Raman mode of C and a mode of SWBNNT, normalized by the same ratio calculated for a reference filling factor, gives a useful method to derive from Raman experiments the relative concentration of C in peapods samples prepared with the same batch as that of the reference filling factor sample.

First, we calculate the Raman spectrum at different filling factors and for each filling factor. Then, for each filling factor, the integrated intensity ratios between Raman mode of molecules and the RBLM (for C phonon modes: Hg(2), Ag(1), Hg(3) and Hg(4)) or G-mode (for phonon modes: Hg(7) and Ag(2)) are calculated. These calculated intensity ratios are normalized with respect to the same intensity ratios calculated for the 60% filling factor sample. The obtained relative concentrations derived by this way in the case @(10,10) are shown in Figure 6. As expected, the relative concentrations calculated for each mode are close especially for low frequency modes expect the Hg(7) and Ag(2) high frequency modes that could showing a overestimated concentration.

Figure 6.

Calculated average intensity ratios, normalized on the 60% filling factor intensities, between modes of the in the @(10,10) peapod crystal and the RBLM (Hg(2), Ag(1), Hg(3), Hg(4)) or G-mode (Ag(2)) of the (10,10) BN nanotube.

4. Conclusions

We have calculated the nonresonant Raman spectrum of isolated boron nitride peapods. The and molecules adopt a linear arrangement for SWBNNTs diameter lower than 1.45 and 1.42 nm, respectively. Both for the obtained and peapods, the dependence of the Raman spectrum as a function of the tube diameter and the filling rate have been analyzed. We showed that the configuration of the and molecules significantly impact the Raman line frequency as well as their intensities in the BN peapod structure. In particular, the line position is modulated by both fullerene-fullerene and fullerene-SWBNNT interactions, whereas the angle dependence of ’s affects their intensities in polarized spectra. We found that the behaviour of the RBLM mode with the pod diameter was clearly modified in peapod. This involves that the linear relation linking the RBLM frequency and the inverse of the tube diameter found in SWBNNT has to be modified in the case of peapod sample. We discussed the Raman signatures of the and peapods according to their filling rate and for the RBLM in particular. The relative intensity ratio between a Raman mode of and and a mode of SWBNNT, normalized by the same ratio calculated for a reference filling factor, could be a useful method to derive from Raman experiments the relative concentration of fullernes in peapods samples prepared with the same batch as the reference filling factor sample. Finally, we think that the calculated Raman spectra reported in the present work can be useful to understand future Raman data.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the CNRS-France/CNRST-Morocco agreement.

Author Contributions

Brahim Fakrach, Fatima Fergani and Mourad Boutahir conceived and carried out the calculations. Abdelhai Rahmani and Hassane Chadli supervised the simulations and contributed to the text. Patrick Hermet and Abdelali Rahmani shared in the writing of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Brien, S.C.; Curl, R.F.; Smalley, R.E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1995, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, N.G.; Luyken, R.J.; Cherrey, K.; Crespi, V.H.; Cohen, M.L.; Louie, S.G.; Zettl, A. Boron nitride nanotubes. Science 1995, 269, 966–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.W.; Monthioux, M.; Luzzi, D. Encapsulated C60 in carbon nanotubes. Nature 1998, 396, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Luzzi, D.E. Formation mechanism of fullerene peapods and coaxial tubes: A path to large scale synthesis. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 321, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluznick, J.L.; Zou, D.J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Q.; Rodriguez-Gil, D.J.; Eisner, C.; Wells, E.; Greer, C.A.; Wang, T.; Firestein, S.; et al. Functional expression of the olfactory signaling system in the kidney. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, C.S.; Ito, Y.; Robertson, A.W.; Shinohara, H.; Warner, J.H. Two-dimensional coalescence dynamics of encapsulated metallofullerenes in carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrones, H. Beyond Carbon Nanopeapods. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13, 2273–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.K.; Tomanek, D.; Iijima, S. “Bucky Shuttle” memory device: Synthetic approach and molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.J.; Thamwattana, N.; Hill, J.M. Orientation of spheroidal fullerenes inside carbon nanotubes with potential applications as memory devices in nano-computing. Physica A 2008, 41, 235209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, R.F. Nanotube ’Peapods’ Show Electrifying Promise. Science 2001, 292, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, S.; Saito, S.; Oshiyama, A. Semiconducting form of the first-row elements: C60 chain encapsulated in BN nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 201303(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, W.; Aloni, S.; Han, W.Q.; Cumings, J.; Zettl, A. Packing C60 in boron nitride nanotubes. Science 2003, 5300, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasi, F.; Simon, F.; Kuzmany, H.; Arenal De La Concha, R.; Loiseau, A. Raman spectroscopy of boron nitride nanotubes and boron nitride-Carbon composites. AIP Conf. Proc. 2005, 786, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamwattana, N.; Hill, J.M. Continuum modelling for carbon and boron nitride nanostructures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 406209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kang, J.W.; Hwang, H.J. Comparison of C60 encapsulations into carbon and boron nitride nanotubes. J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 2004, 16, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trave, A.; Ribeiro, F.; Louie, S.; Cohen, M. Energetics and structural characterization of C60 polymerization in BN and carbon nanopeapods. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 205418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettl, A.; Cumings, J.; Weiqiang, H.; Mickelson, W. Boron nitride nanotube peapods. AIP Conf. Proc. 2002, 633, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burteaux, B.; Claye, A.; Smith, B.W.; Monthioux, M.; Luzzi, D.E.; Fischer, J.E. Abundance of encapsulated C60 in single-wall carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys, Lett. 1999, 310, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.H.; Son, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, H.J. Molecular dynamics simulation of C60 encapsulated in boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Status Solidi B 2004, 241, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodak, M.; Girifalco, L.A. Systems of C60 molecules inside (10,10) and (15,15) nanotube: A Monte Carlo study. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 085405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodak, M.; Girifalco, L.A. Ordered phases of fullerene molecules formed inside carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 075419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, H.; Rahmani, A.; Sbai, K.; Hermet, P.; Rols, S.; Sauvajol, J.-L. Calculation of Raman-active modes in linear and zigzag phases of fullerene peapods. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 205412–205419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, H.; Rahmani, A.; Sbai, K.; Sauvajol, J.L. Raman active modes in carbon peapods. Physica A 2005, 358, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Barraza, R.E.; Guirado-Lopez, R.A. Clustering of H2 molecules encapsulated in fullerene structures. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 155426–155437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Li, H.; Shi, Z.; You, L.; Gu, Z. Standing or lying C70s encapsulated in carbon nanotubes with different diameters. Solid State Commun. 2005, 133, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergani, F.; Chadli, H.; Belhboub, A.; Hermet, P.; Rahmani, A. Theoretical Study of the Raman Spectra of C70 Fullerene Carbon Peapods. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 5679–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergani, F.; Abdelkader, S.A.A.; Chadli, H.; Fakrach, B.; Rahmani, A.H.; Hermet, P.; Rahmani, A. C60 filling rate in carbon peapods: A nonresonant raman spectra analysis. Hindawi J. Nanomater. 2017, 2017, 9248153–9248159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Fujita, M.; Dresselhaus, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Electronic structure of graphene tubules based on C60. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, N.; Sawada, S.I.; Oshiyama, A. New one-dimensional conductors: Graphitic microtubules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 1579–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkrim, F. Levesque, Monte Carlo simulations of hydrogen adsorption in single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 19, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakrach, B.; Rahmani, A.; Chadli, H.; Sbai, K.; Bentaleb, M.; Bantignies, J.L.; Sauvajol, J.L. Infrared spectrum of single-walled boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 115437–115446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jishi, R.A.; Mirie, R.M.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Force-constant model for the vibrational modes in C60. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13685–13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.M.; Artacho, E.; Gale, J.D.; GarcÃ, A.; Junquera, J.; Ordejon, P.; Sanchez-Portal, J. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 2745–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Menendez, J.; Page, J.B.; Adams, G.B. Empirical bond polarizability model for fullerenes. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 13106–13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, C.; Royer, E.; Poussigue, G. The spectral moments method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1992, 4, 3125–13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.; Benoit, C.; Poussigue, G. Vibrational properties of random percolating networks. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1993, 5, 7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, H.; Rahmani, A.; Sauvajol, J.-L. Raman spectra of C60 dimer and C60 polymer confined inside a (10,10) single-walled carbon nanotube. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 145303–145312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, H.; Fergani, F.; Bentaleb, M.; Fakrach, B.; Sbai, K.; Rahmani, A.; Bantignies, J.-L.; Sauvajol, J.-L. Influence of packing on the vibrations of homogeneous bundles of C60 peapods. Physica E 2015, 71, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.J.; Cracknell, A.P. The Mathematical Theory of Symmetry in Solids: Representation Theory for Point Groups and Space Groups; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1972; ISBN-13: 978-0199582587. [Google Scholar]

- Golberg, D.; Bando, Y.; Kurashima, K.; Soto, T. Synthesis and characterization of ropes made of BN multiwalled nanotubes. Scr. Mater. 2001, 44, 1561–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.H.; Hsu, C.K.; Tang, T.P.; Kang, P.L.; Yang, F.F. Thermal-heating CVD synthesis of BN nanotubes from trimethyl borate and nitrogen gas. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008, 107, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Wang, J.; Kayatsha, V.K.; Huang, J.Y.; Yap, Y.K. Junctions between a boron nitridenanotube and a boron nitride sheet. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 455605–455616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.H.; Luo, J.; Wei, J.; Lin, J. Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes and its hydrogen uptake. Catal. Today 2007, 120, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.W.; Jordan, K.C.; Park, C.; Kim, J.W.; Lillehei, P.T.; Crooks, R.; Harrison, J.S. Very long single and few-walled boron nitride nanotubes via the pressurized vapor/condenser method. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 505604–505609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, W.; Dai, Y. Stability and electronic properties of small boron nitride nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 084312–084319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakrach, B.; Rahmani, A.; Chadli, H.; Sbai, K.; Sauvajol, J.L. Raman spectrum of single-walled boron nitride nanotube. Physica E 2009, 41, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.N. Lattice dynamics of single-walled boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 085408–085413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, L.; Rubio, A.; de la Concha, R.A.; Loiseau, A. Ab initio calculations of the lattice dynamics of boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 045425–045437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdim, R.; Pachter, R.; Xiaofeng, D.; Adams, W.W. Comparative theoretical study of single-wall carbon and boron-nitride nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 245404–245411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataura, H.; Kumazawa, Y.; Maniwa, Y.; Umezu, I.; Suzuki, S.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Achiba, Y. High-Yield Fullerene Encapsulation in Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Synth. Metals 2001, 121, 1195–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorro, M.; Delhey, A.; No, L.; Monthioux, M.; Launois, P. Orientation of C70 molecules in peapods as a function of the nanotube diameter. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 035416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pichler, T.; Knupfer, M.; Golden, M.S.; Fink, J.; Kataura, H.; Achiba, Y.; Hirahara, K.; Ijima, S. Filling factors, structural, and electronic properties of C60 molecules in single-wall carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 045419–045424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandow, S.; Takizawa, M.; Kato, H.; Okazaki, T.; Shinohara, H.; Iijima, S. Smallest limit of tube diameters for encasing of particular fullerenes determined by radial breathing mode raman scattering. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 347, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).