Abstract

Cancer ranks as a major cause of morbidity and mortality across the globe, notably in economically developed regions, and its incidence is predicted to rise in the coming decades. Metal-based compounds represent a particularly promising class of pharmaceuticals for the treatment of cancer. Following the success of platinum in cancer therapy, attention soon turned to other transition metals, particularly the platinum group metals such as ruthenium and palladium. Despite the high anticancer efficacy of many of its compounds, osmium remained one of the least investigated of these metals for a long time, partly due to concerns about its toxicity. However, there has been a recent resurgence in the preparation and evaluation of osmium complexes, which exhibit high structural variability and demonstrate promising anticancer activity. The present review aims to survey recent developments in this exciting field, focusing on osmium complexes of the non-arene type reported during the last decade.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, cancer has progressed to the second leading cause of death worldwide after cardiovascular disease. Cancer’s position in this regard reflects levels of social and economic development; thus, in developed countries, cancer already ranks first as a cause of death at ages below 70 years [1]. Based on GLOBOCAN estimates, approximately 8.2 million people died from cancer, and 14.1 million new cases were diagnosed worldwide in 2012. This negative trend is expected to continue also in the future, with an estimated 20 million new cancer cases annually anticipated by 2025 [2]. The reasons are complex, including aging of the population, lifestyle risk factors (environmental pollution, stress, tobacco smoking, overweight, physical inactivity, and improper diet patterns), but also genetic factors [3]. Despite considerable progress achieved in methods of cancer therapy, the therapeutic options are still, in the vast majority of cases, far from satisfactory.

The discovery of the anticancer activity of cisplatin represents a milestone in the evolution of chemotherapy. It shows marked activity in many tumor types. In some cases, like testicular and ovarian cancer, a complete cure is possible. Since then, a substantial number of metal complexes have been synthesized and examined for their potential antineoplastic properties in an effort to develop drugs with an enlarged spectrum of activity and diminished systemic toxicity. Already early on, the focus started to move towards complexes of metals other than platinum. Such complexes facilitate different mechanisms of anticancer activity, potentially providing drugs able to circumvent intrinsic and acquired resistance in cancer cells [4]. Metallodrugs offer unique possibilities for the development of pharmaceuticals, allowing variations in the type of the central metal atom, its oxidation state, redox potential, as well as in the type of ligands, rate of ligand exchange, and the three-dimensional coordination geometry of the resulting complex. Ruthenium, palladium, and gold are among the most popular metals, although several less common metals (including osmium) are also gaining attention.

Osmium, a relatively unfamiliar transition element, demonstrates potential not only in the treatment of cancer but also in the field of antimicrobial chemotherapy. The increased interest in this metal started around the turn of the millennium in connection with the role of osmium as a chemical congener of ruthenium. Ruthenium complexes represent a well-established group of experimental metallodrugs, with several complexes being tested in clinical trials [5]. Hence, among the first osmium complexes tested were osmium analogs of ruthenium complexes with known anticancer activity, especially the ruthenium compounds NAMI-A and KP1019. Many more osmium compounds have been investigated since, although wider progress in this area has been slowed down due to the low natural abundance of osmium (and, consequently, high price) as well as the toxicity of many of its compounds. Nevertheless, the number of reports on osmium metallodrugs has been increasing recently, with several articles attempting to provide a rationale for their development [6,7,8,9].

The objective of the present survey is to discuss the advancements in the development of osmium anticancer agents. A concise introduction to the chemistry and applications of osmium is followed by an examination of its synthesis, properties, and mechanism of biological action. The text then turns its attention to new osmium complexes with non-arene structures, that is, structures that do not involve the π-bonding ligands, as reported during the last decade.

2. Osmium—Its Chemistry, Applications, and Bioactivity

The discovery of osmium as a new element is closely related to the discovery of platinum and other metals belonging to the platinum group. It is associated with the name of the English chemist Smithson Tennant, who discovered it in 1803 while examining the insoluble residue after dissolving platinum in aqua regia [10]. The element derives its name from the Greek term for “smell”, “osme”, a reference to the pungent odor of the volatile osmium tetroxide that is produced in trace amounts during the oxidation of metallic osmium in the air. Osmium is one of the rarest stable elements, with an abundance of approximately 0.005 ppm in the Earth’s crust.

As a representative platinum group metal, the element demonstrates notable chemical inertness, exhibiting direct reactions primarily with fluorine, chlorine, and oxygen [11,12]. Compact metallic osmium exhibits a high degree of resistance to molecular oxygen at ambient temperature. In contrast, finely dispersed osmium undergoes a gradual process of oxidation, resulting in the formation of osmium tetroxide.

Osmium is known to form an extensive array of compounds, with oxidation states ranging from −IV to +VIII. The most prevalent oxidation states are +II, +III, and +IV. High oxidation states of Os are stabilized by strong σ- and π-donor ligands such as O2−, N3−, and F−. Low oxidation states are found in complexes with π-acceptor ligands (CO, PPh3, bipy, phen, etc.). The high oxidation states of Os are much less oxidizing (i.e., more stable) than the corresponding oxidation states of its congener ruthenium (e.g., OsO4 vs. RuO4). The coordination chemistry of Os is characterized by a high prevalence of octahedral geometry.

The most important compound of osmium is osmium tetroxide, noteworthy as one of the few compounds where the oxidation state +8 is observed [13]. It is a pale-yellow crystalline solid with a low melting and boiling point (40 °C and 130 °C, respectively). The compound is a strong oxidizing agent, with limited water solubility and significant solubility in numerous organic solvents. In addition to its synthesis from the elements, a multitude of other compounds of osmium can be readily oxidized to produce this substance. Consequently, it is also responsible for a significant proportion of their toxicity, given its volatility and high reactivity, which can lead to damage to the cornea of the human eye. OsO4 represents the most important starting material for the synthesis of other osmium compounds.

Of particular significance in the synthesis of biologically active compounds are osmium complexes in oxidation states II and III. Mixed valence compounds (OsII/III) are also frequently encountered. OsIII complexes exhibit paramagnetism, while OsII is diamagnetic [14,15,16]. The coordination of the π-acceptor dinitrogen ligand has been reported as well (e.g., [17]).

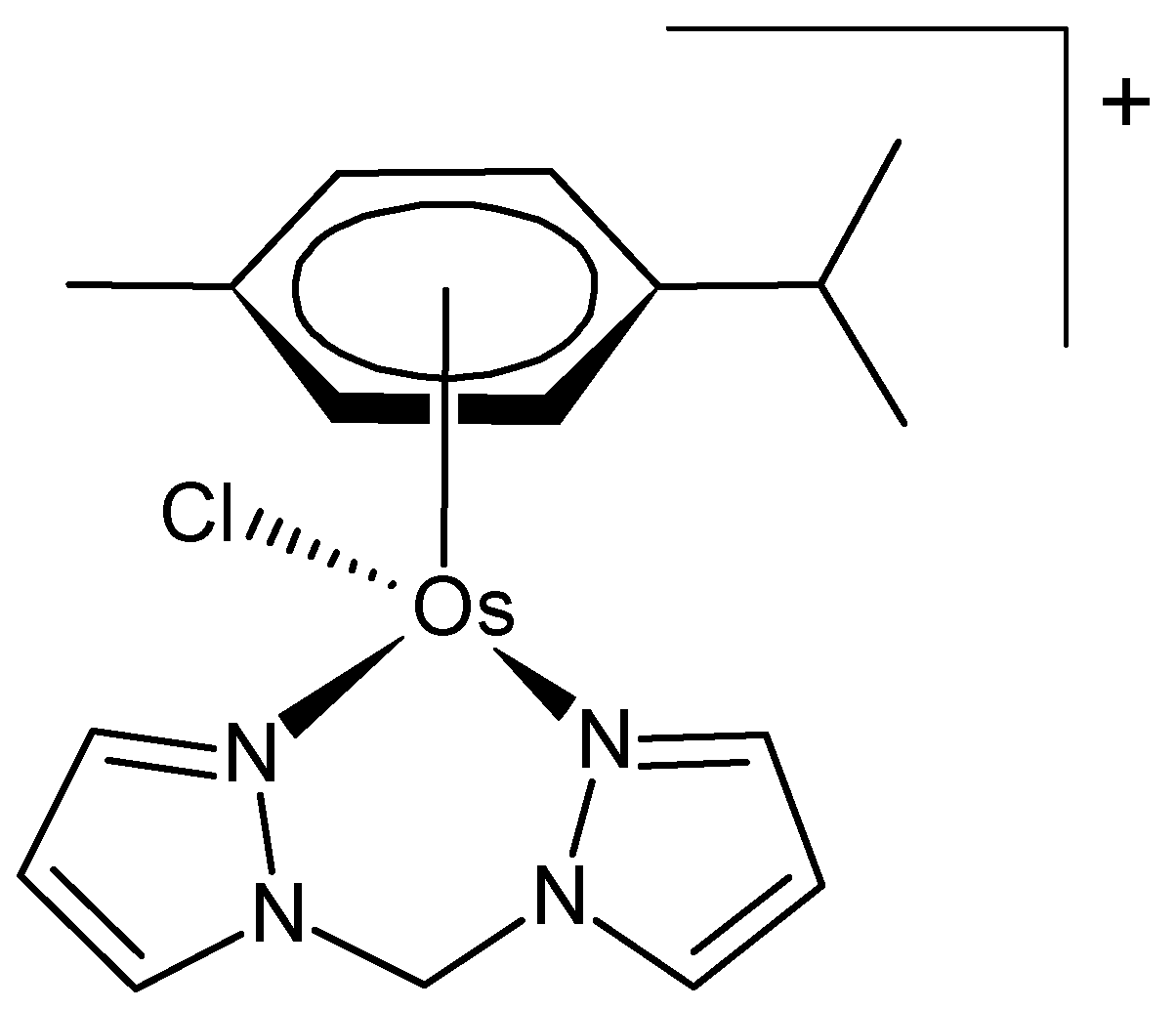

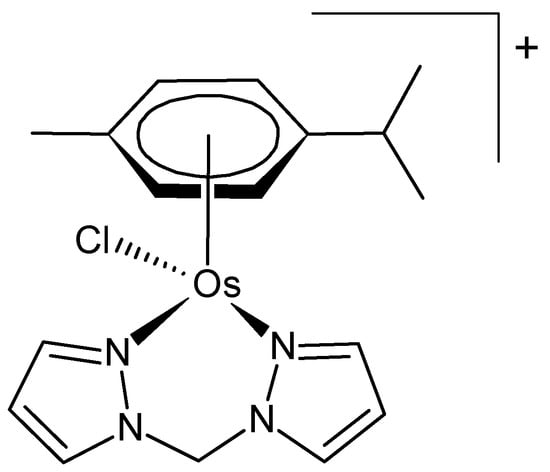

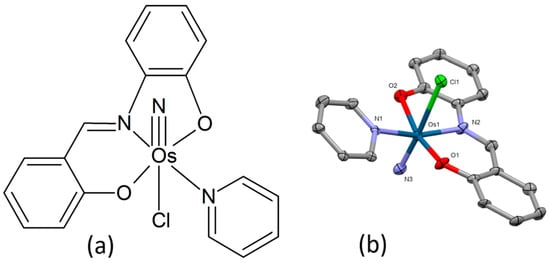

Osmium forms many mononuclear and polynuclear organometallic complexes, mainly in lower oxidation states. Much interest has been shown in organometallic complexes of osmium coordinated to the π-system of aromatic rings (sandwich and half-sandwich complexes). Prominent among these are metallocenes, a class of organometallic compounds that are distinguished by the attachment of two cyclopentadienyl [Cp] ligands, which form π-bonds with the central metal atom [18]. Numerous half-sandwich complexes of osmium bearing coligands have been reported; many of them exert interesting anticancer activity [9]. A particular type of these complexes incorporates the ‘piano-stool’ structural motif. They typically consist of an η5- or η6-coordinated arene ligand, a bidentate coligand (e.g., N-heterocycles), and a monodentate ligand (often halogens). The structure of a typical piano-stool osmium(II) complex is depicted in Figure 1 [19].

Figure 1.

Chemical formula of a piano-stool osmium(II) complex [19].

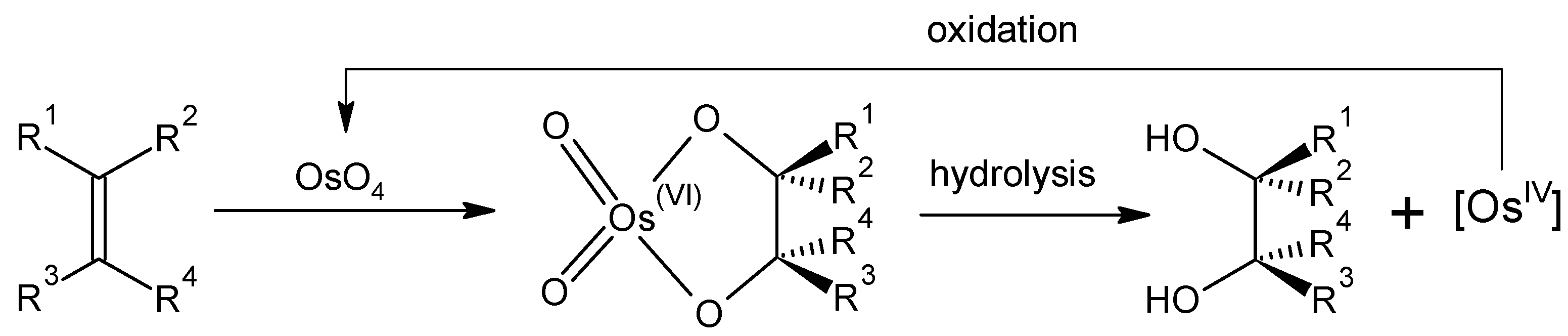

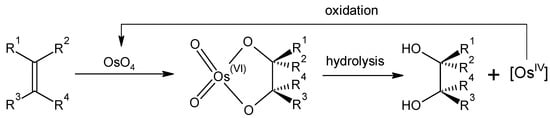

Thus far, the practical applications of elemental osmium and its compounds have been limited due to their cost and toxicity issues. The most significant of these is the use of osmium tetroxide in the dihydroxylation of olefins to cis diols [20,21]. The reaction is believed to occur via an osmate ester intermediate, with the resultant oxidative or reductive cleavage forming the cis-diol (Scheme 1). In this regard, OsO4 can be utilized either stoichiometrically or catalytically. An enantioselective variant of the reaction, the Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation, proceeds in the presence of chiral ligands [22]. OsO4 is often generated in situ from K2[OsO2(OH)4] due to its lower toxicity.

Scheme 1.

Catalytic cis-dihydroxylation of alkenes using OsO4 [12].

The utilization of osmium tetroxide solution as a biological stain has a longstanding history, particularly in the context of sample preparation for electron microscopy [23,24,25]. The effect is likely based on its lipid-selective chemical reactivity, promoting the formation of osmate esters of unsaturated fatty acids in lipid membranes. Osmium compounds have also been used as probes for DNA/RNA sensing and imaging [26,27,28,29,30].

In addition to their anticancer activities, osmium compounds have garnered significant attention for their antimicrobial properties, e.g., [31]. Recently, osmium complexes with group 13 analogs of N-heterocyclic carbene ligands were proposed as a potential antidote to reduce carbon monoxide poisoning [32].

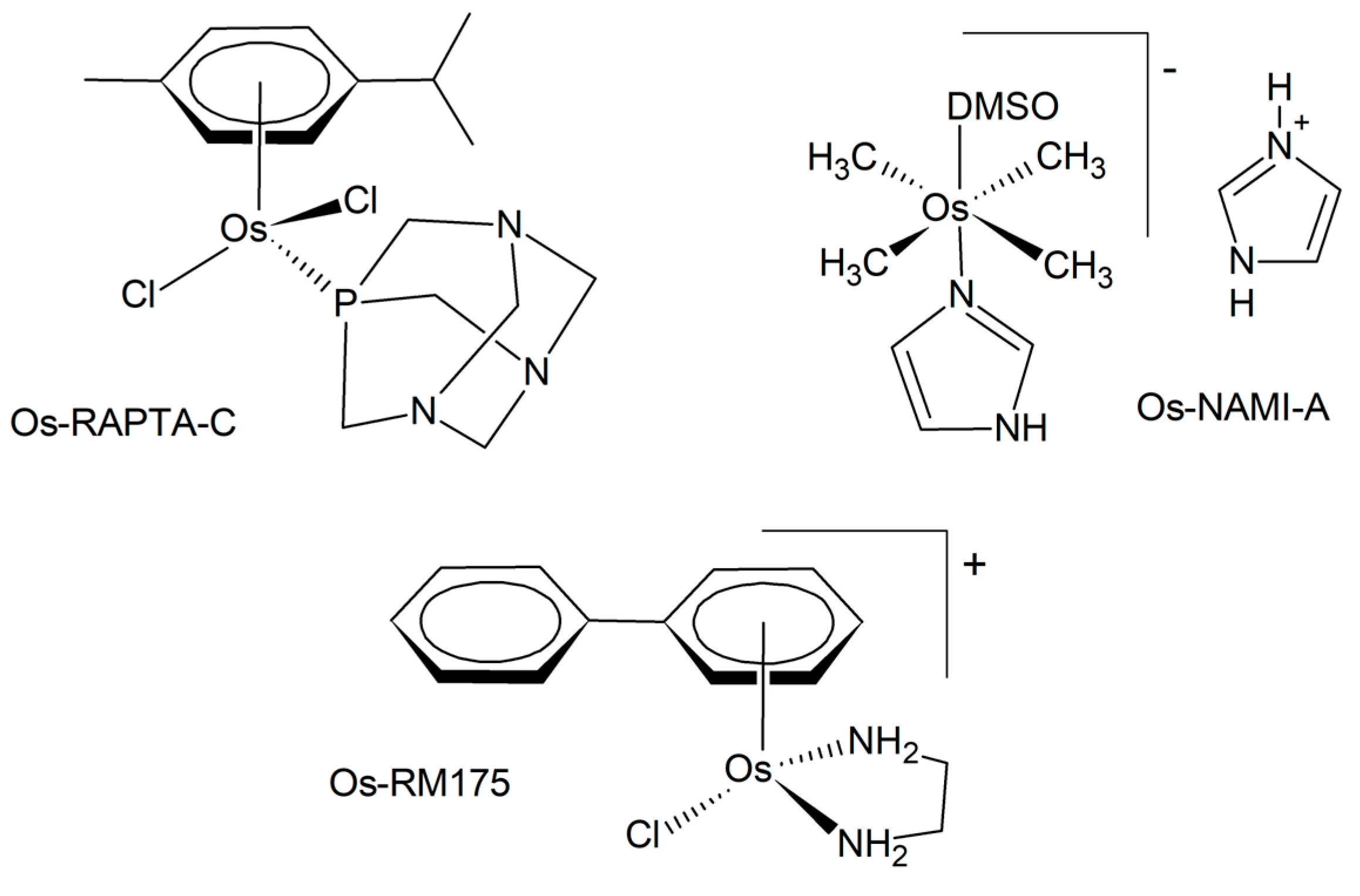

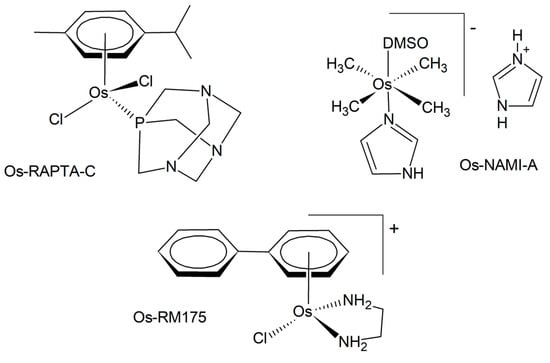

The first osmium anticancer agents were developed as congeners of the existing ruthenium lead structures, such as RAPTA-C, NAMI-A, or RM-175 (Figure 2) [9]. In comparison, they are often more inert and stable towards hydrolysis. According to the HSAB (Hard and Soft Acids and Bases) theory, osmium is comparatively softer than ruthenium, thus modifying its coordination behavior toward biomolecules. The mode of biological action of osmium compounds is intricate and has been the subject of numerous recent reports. A selection of these reports is presented below. It is probable that several mechanisms are implicated, including interactions with DNA, modulation of redox processes, and enzyme inhibition [6]. In the initial phase, metal complexes, including osmium, can be activated through the formation of an aquated complex in aqueous solution. This process enables subsequent interaction with biomolecular targets, including DNA and proteins [33]. This often involves the exchange of a chlorido-ligand or other halogen against water [34,35,36]. The complexes have also been observed to bind to human serum albumin in blood serum, thereby establishing a depot for osmium and modulating its biodistribution and transport processes [37]. Similarly to ruthenium, it has been suggested that for high-valent anticancer osmium complexes, their antiproliferative activity may depend on an initial reduction reaction with thiols that occurs within the cells [38]. While not entirely responsible for their activity, the binding of osmium complexes to the nucleobases of DNA may contribute to their anticancer properties [36]. Glutathione depletion was suggested as a distinct mechanism as well [39,40]. Target sites for an organo-osmium complex, a promising drug candidate, in human ovarian cancer cells were identified with the help of a synchrotron X-ray fluorescence nanoprobe [41]. The data indicate that Os is localized in the mitochondria rather than the nucleus, concomitant with calcium mobilization from the endoplasmic reticulum. This calcium mobilization serves as a signaling event that initiates cell death. The capability of different osmium anticancer complexes to generate reactive oxygen species was investigated in vitro and in a zebrafish model, demonstrating elevated levels of ROS [42]. Inhibition of antioxidant systems represents another way of increasing oxidative stress in cancer cells [43,44]. The results obtained lend support to the hypothesis that the observed cell apoptosis is a consequence of thioredoxin reductase inhibition. The ability of osmium complexes to induce the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway was also demonstrated [45]. Specific mechanisms are involved in the action of photoactive osmium complexes.

Figure 2.

Examples of the osmium analogs of anticancer ruthenium complexes.

3. Non-Arene Osmium Complexes for Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an antineoplastic treatment that uses a photosensitizer (PS), low-energy light, and oxygen to create photocytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damage cancer cells [46]. The application of metal complexes as photosensitizers in PDT can prove advantageous in terms of the amount of ROS generated, quantum emission efficiency, and phototoxic index [47]. This section primarily lists original studies on novel osmium complexes with reported photocytotoxic properties.

Osmium polyazine complex and its ruthenium analog, [(Ph2phen)2Ru(dpp)]2+ and [(Ph2phen)2Os(dpp)]2+, where (Ph2phen = 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline; dpp = 2,3-bis(2-pyridyl)pyrazine), were prepared and characterized in an effort to study their use as light-activated medications to combat malignant glioma F98 cells in a rat model [48]. Both complexes showed significant absorption in the visible spectral range, as well as DNA and BSA photocleavage mediated by oxygen. They also demonstrated substantial photocytotoxicity under blue light irradiation, with minimal activity observed in the dark. Additionally, the osmium complex exhibited encouraging photocytotoxicity in F98 rat malignant glioma cells when exposed to red light. The products were examined using elemental analysis, ESI-MS, electronic absorption, and electrochemical analysis, displaying a distorted octahedral coordination.

Recently, five polypyridyl Os(II) complexes with the general formula [(DIP)2OsL](PF6)2, where DIP = 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline and L are various substituted phenazine derivatives, were prepared and studied by 1H/13C NMR, HRMS, elemental analysis, electrochemistry, and DFT calculations [49]. All complexes showed marked photocytotoxicity in MGC-803 and HGC-27 human gastric cancer cells, demonstrating IC50 values as low as 0.37 µM and 0.32 µM, respectively, when exposed to blue LED light. An enhancement of 1O2 generation was observed upon elongation of the conjugated π system of the aromatic ligand. Subcellular localization of osmium in A549 human non-small cell lung cancer cells was investigated by confocal microscopy.

Lu and Chen investigated a dinuclear osmium(II) complex with a polypyridyl-type ligand as a new gastric cancer photosensitizer [50]. Spectroscopic measurements indicate the presence of the expected octahedral coordination. The complex was further studied by electrochemical cyclic voltammetry, density functional theory (DFT), and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT). Its photocytotoxicity was assessed in A549, Caco-2, MGC-803, and HGC-27 cancer cell lines. It exhibited moderate to great photocytotoxicity against HGC-27 human gastric cancer cells exposed to blue LED light, with the IC50 value as low as 1.83 μM, while being almost non-cytotoxic in the dark. Subcellular colocalization studies suggest that the complex was not enriched in the nucleus and was less likely to target mitochondria.

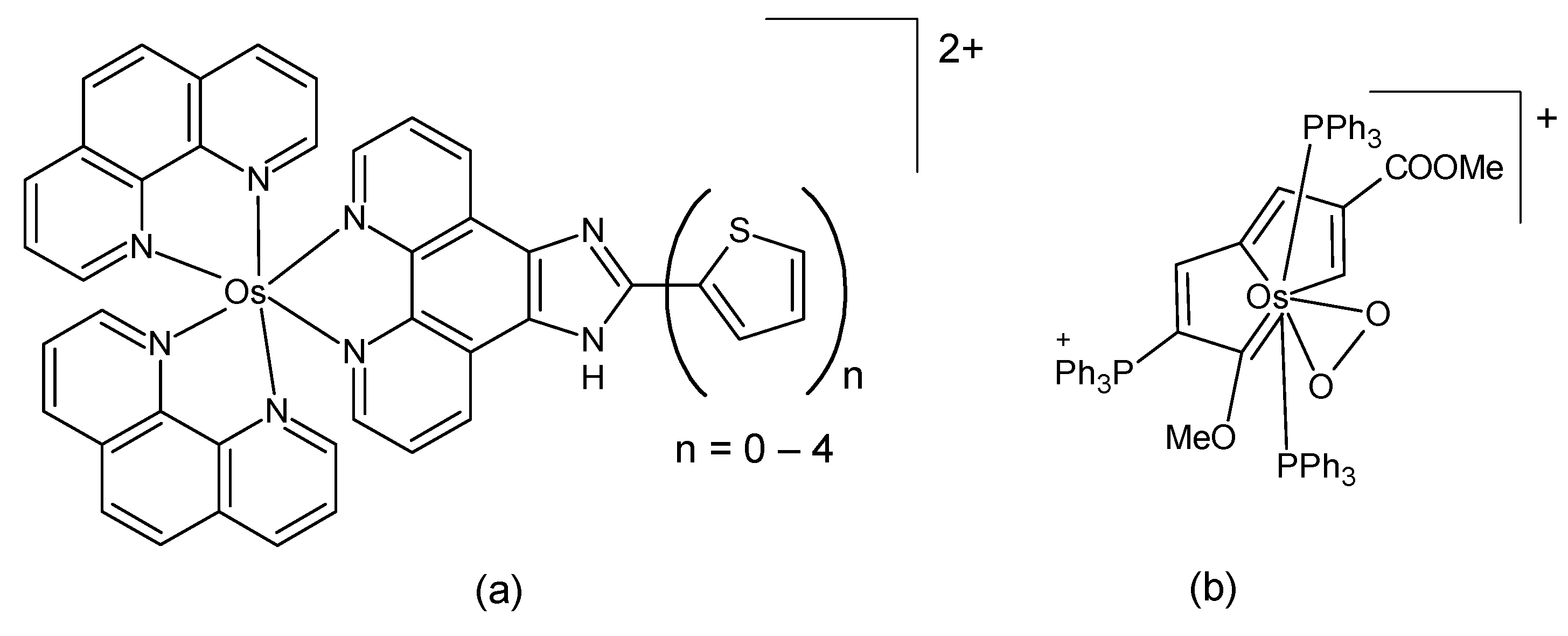

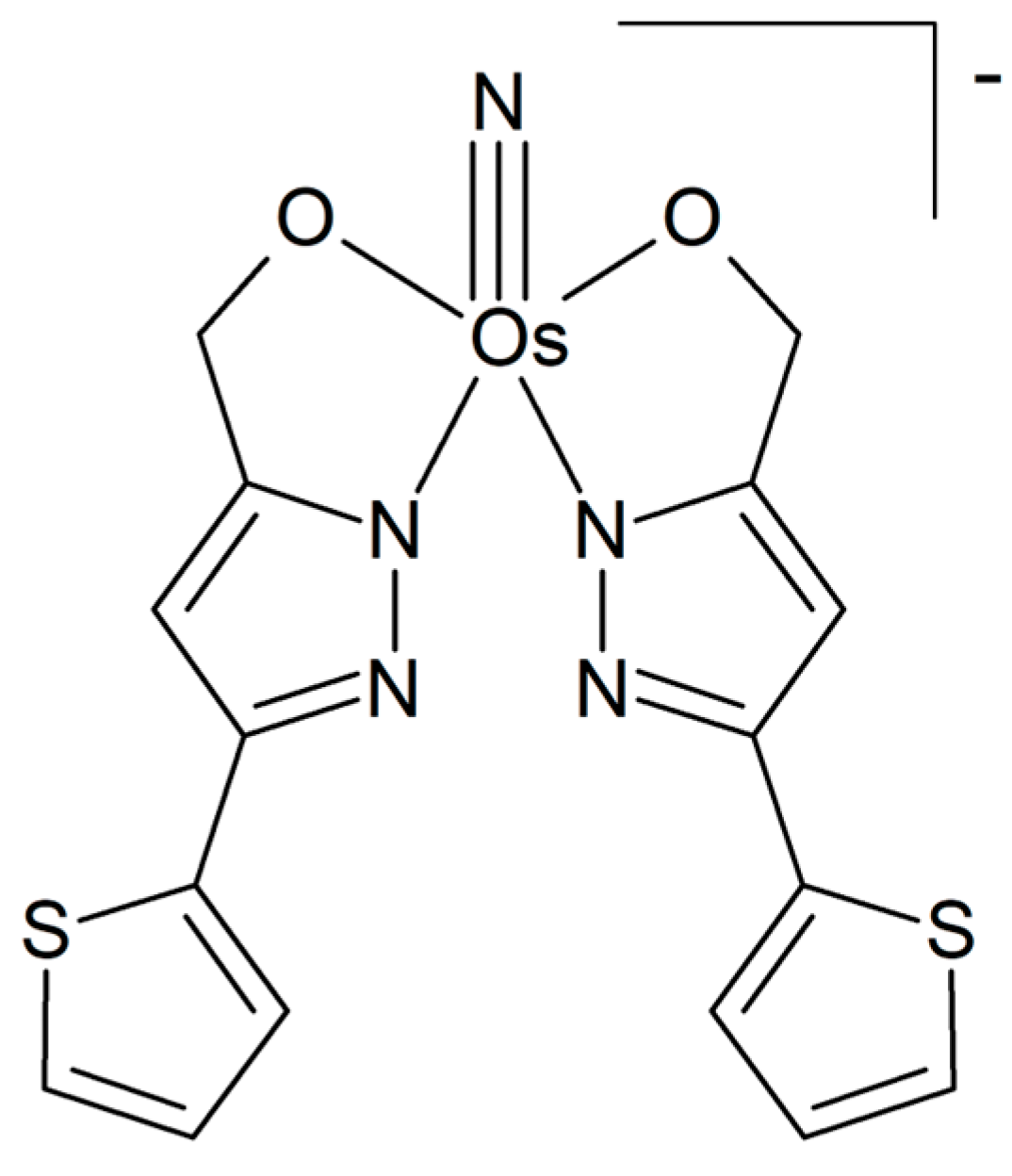

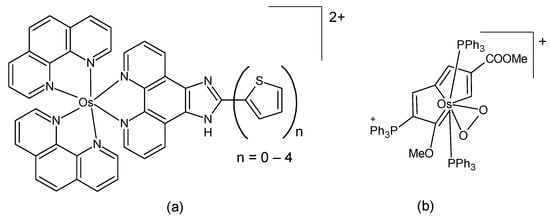

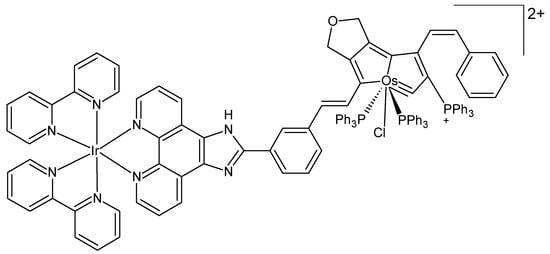

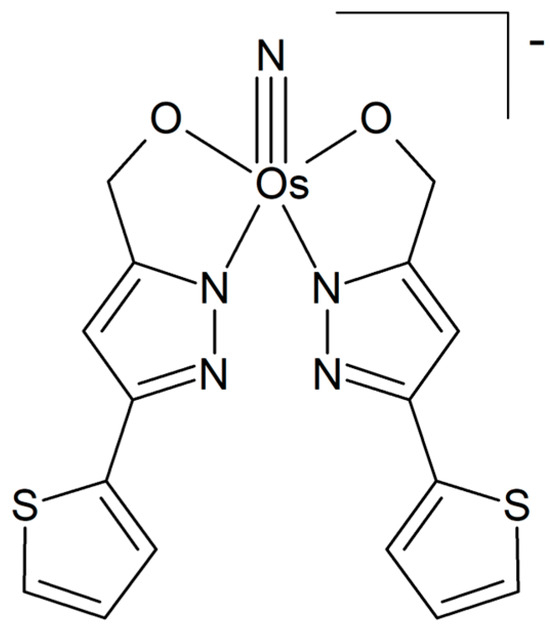

A series of hypoxia-responsive osmium-containing photosensitizers was synthesized as analogs of the established ruthenium complex TLD1433 [51]. Their composition corresponds to the general formula [Os(phen)2(IP-nT)]Cl2, where IP-nT is a polypyridyl ligand containing 0 to 4 thiophene units (Figure 3a). The structures of the compounds were confirmed by high-resolution ESI-MS and 1H-NMR. The compounds in the series exhibited relatively low in vitro toxicity in the dark; however, they demonstrated an increase in phototoxicity with the incorporation of additional thiophenes. These properties could be maintained even in hypoxia. The complex with the longest thiophene chain was identified as the most suitable candidate compound, exhibiting activity in the picomolar region and a favorable phototherapeutic index. It has been posited that the substitution of ruthenium(II) with the heavier osmium(II) center results in a shift in the optical window for activation to longer wavelengths, accompanied by higher quantum yields for triplet state generation. A report was also made on several structurally similar osmium(II) complexes in which bipyridine was used as a coligand instead of phenanthroline [52]. Again, the complex with four thiophene rings exerted the highest in vitro activity, with low nanomolar activity in normoxia and a sub-micromolar potency even in hypoxia. The authors also demonstrated that the identity of the coligand had a considerable influence on the photophysical and photobiological outcomes.

Figure 3.

The chemical formula of (a) the osmium analog of the ruthenium complex TLD1433 [51]; (b) an osmium-peroxo complex [53].

Lu et al. studied an osmium-peroxo complex (Figure 3b). This complex has the capacity to release the peroxo ligand O2•− when irradiated by visible light, even under anoxic conditions. Additionally, it undergoes transformation into another active osmium complex [53]. The light-activated osmium-peroxo complex has been shown to promote photocatalytic oxidation of endogenous 1,4-dihydronicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in cancer cells, resulting in ferroptosis. The dark- and photocytotoxicities of the osmium-peroxo complex and of the product of its photochemical decomposition were determined with an MTT method against HeLa cells. The osmium-peroxo complex demonstrated low dark cytotoxicity and high photocytotoxicity in both normoxic and hypoxic environments. The in vivo investigation of the aforementioned complex (in HeLa tumor-bearing Balb/c mice) revealed a suppression of tumor growth in mice upon treatment with the osmium-peroxo complex under light exposure.

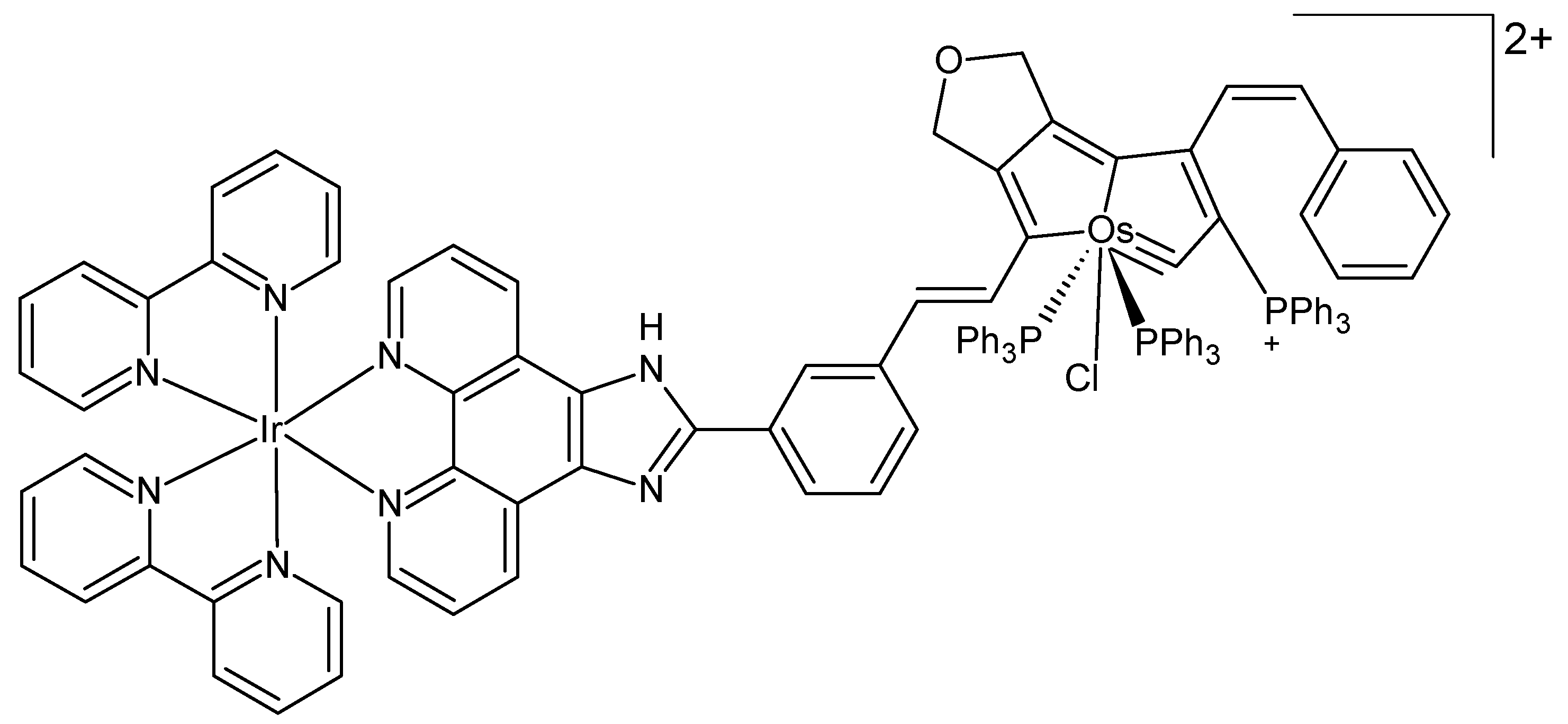

Recently, Wang et al. designed a heteronuclear iridium-osmium complex as a photosensitizer for PDT in melanoma cells irradiated by 550 nm LED light (Figure 4) [54]. The complex exhibited outstanding ROS production efficacy and enhanced photocatalytic oxidation of NADH under irradiation. Moreover, it was able to impede the synthesis of bioenergetic molecules within cancerous cells by targeting the glycolytic pathway, consequently inducing a state of ATP starvation and subsequent cell death. The results of both in vivo and in vitro experiments revealed the effective inhibition of melanoma cell growth, accompanied by notable photocytotoxicity.

Figure 4.

Chemical formula of a heteronuclear iridium-osmium complex [54].

Supramolecular coordination compounds have demonstrated considerable promise in the field of photodynamic cancer therapy. In a recent study, Qin et al. described the design of a novel heteroleptic/trimetallic OsII−RuII−ZnII Sierpiński triangle (a polypyridyl-type ligand) [55]. The synthesis was accomplished through coordination-driven self-assembly of bipyridyl osmium(II) building units and trinuclear terpyridyl ruthenium(II) building units with Zn2+ ions. The compound exhibited a notable capacity to produce reactive oxygen species. In vitro experiments revealed the remarkable efficacy of photodynamic therapy in all studied cancer cell lines, exhibiting low IC50 values in the subnanomolar range and high phototoxicity indices, even under hypoxic conditions. The structures of the complexes were established by 1D- and 2D-NMR as well as by ESI-MS.

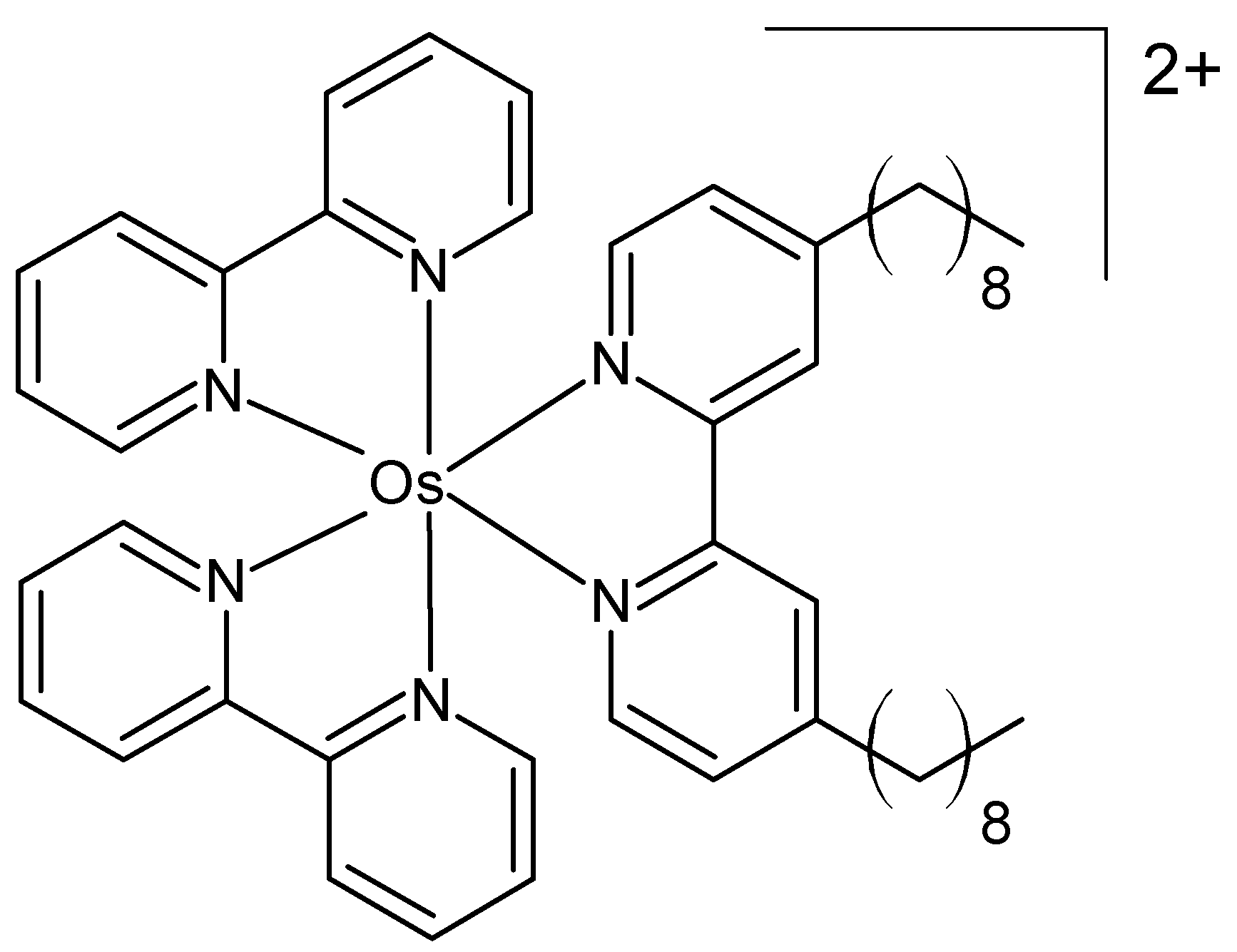

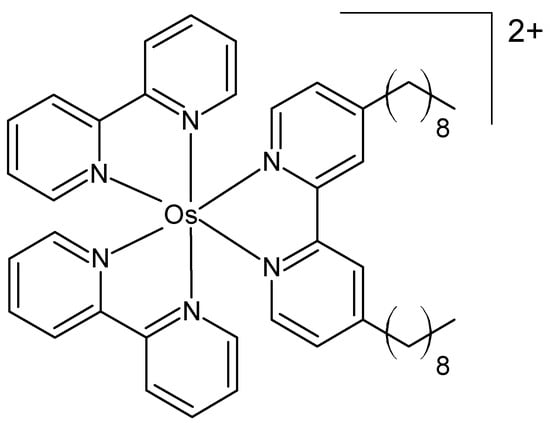

Zhou et al. prepared three osmium(II) complexes containing ligands with different alkyl chains as organelle-targeting photosensitizers, pursuing an aggregation-induced photosensitization strategy [56]. Their structure was confirmed by NMR and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. They exhibited full-wavelength absorption (350–700 nm) and near-infrared fluorescence (650–850 nm). The cytotoxicity was evaluated in MCF-7 cells and in a 4T1-tumor-bearing BALB/c mouse model. The complex depicted in Figure 5 exhibited superior PDT performance due to its efficient generation of superoxide anions and singlet oxygen.

Figure 5.

Chemical formula of an organelle-targeting photosensitizer [56].

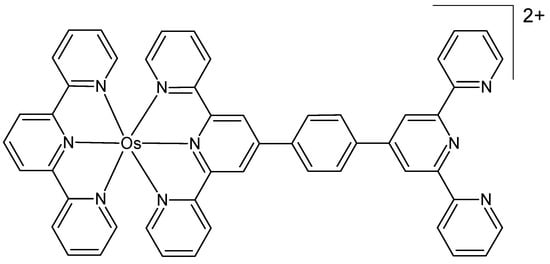

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) represent a significant target in antineoplastic therapy, as they are overexpressed in the cytoplasm or membrane of a variety of cancer cells [57,58]. In their study, Wang et al. presented a series of novel sulfonamide-based monopodal and dipodal ruthenium and osmium polypyridyl complexes with the capacity to target carbonic anhydrases, anticipating accumulation of the complexes in or outside cancer cells prior to irradiation and thus an improvement of the selectivity of the PDT treatment [59]. The complexes demonstrated a high affinity for CAs, accumulating in cancer cells that overexpress CA and inducing cancer cell death under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions following irradiation at 540 nm. The candidate compounds were investigated by 1H/13C NMR and HR-MS. They exhibited octahedral coordination and were isolated in the form of a racemic mixture of the Λ and Δ enantiomers. In the case of a non-symmetrical bipyridine ligand, this results in the formation of a mixture of diastereoisomers.

The combination of photodynamic (PDT) and photothermal (PTT) therapy has the potential to generate a synergistic effect, thereby enhancing the efficacy of cancer treatment [60,61,62]. In 2024, Xiong et al. reported the preparation of mono- and dinuclear Os complexes exhibiting dual PDT/PTT capabilities using a single excitation wavelength in the near-infrared (NIR) region [63]. The molecular structure of the products was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The structural analysis revealed the presence of a bisbenzoimidazolyl naphthyridine ligand within both complexes, exhibiting a cationic character with a Cl− counterion. The Os center was coordinated with two bipyridines, as well as a pyridyl and a benzimidazolyl group of the main ligand, to yield a regular octahedral geometry. Additionally, the authors prepared aptamer-conjugated cellulose nanoparticles (NPs) doped with the osmium complex, exhibiting an increased ability to target mitochondria. Following single NIR laser irradiation, the resultant NPs exhibited an apparent increase in singlet oxygen production and temperature, thereby substantiating their efficacy in PDT and PTT therapies.

Fluorophores that emit in the near-infrared (NIR) region can significantly reduce light scattering and background absorption due to the existence of an optical window in a biological system, minimizing photodamage to biological material [64]. Zhang et al. synthesized a pair of Os(II) and Ru(II) analogs as lysosome imaging and photodynamic therapy agents [65]. The products were examined using MS, NMR, and elemental analysis, supporting the putative octahedral coordination around the central atom. The osmium complex was found to be advantageous over its ruthenium analog in terms of photophysical characteristics, cellular imaging capability, and phototoxicity towards cancer cells. A549 cancer cells were highly susceptible to the toxicity of the studied osmium(II) polypyridyl complex upon 633 nm light irradiation. It also displayed activity against HeLa and Hep-G2 cells, but was nearly non-toxic towards MRC-5 normal cells.

In recent years, mitochondria have become a significant target for cancer therapy, with agents designed to target mitochondria frequently able to circumvent cell resistance mechanisms [66,67,68,69]. Ge et al. developed three NIR-active terpyridine Os(II) complexes targeted to mitochondria as photosensitizers for PDT, displaying strong NIR phosphorescence emission as well as long phosphorescence lifetime [70]. Their structure was confirmed by elemental analysis, NMR, and ESI-MS spectra. The compounds displayed specific staining ability directed towards mitochondria, generated singlet oxygen, converted NADH to NAD+, and showed marked phototoxicities against cancer cells upon both 465 nm and 633 nm light irradiation. The putative structure of the most cytotoxically active osmium complex is depicted in Figure 6. Ge and co-workers also prepared two novel osmium(II) complexes that exhibited outstanding NIR luminescence capability [71]. They were characterized by ESI-MS, elemental analysis, and NMR, supporting the expected octahedral coordination. The study revealed the distinct binding ability of both compounds to RNA, suggesting that RNA may represent a novel target for osmium compounds. The cytotoxicity of the complexes in the cell line A549 (human lung carcinoma), expressed as cell viability, was low.

Figure 6.

Mitochondria-targeted terpyridine osmium(II) complex [70].

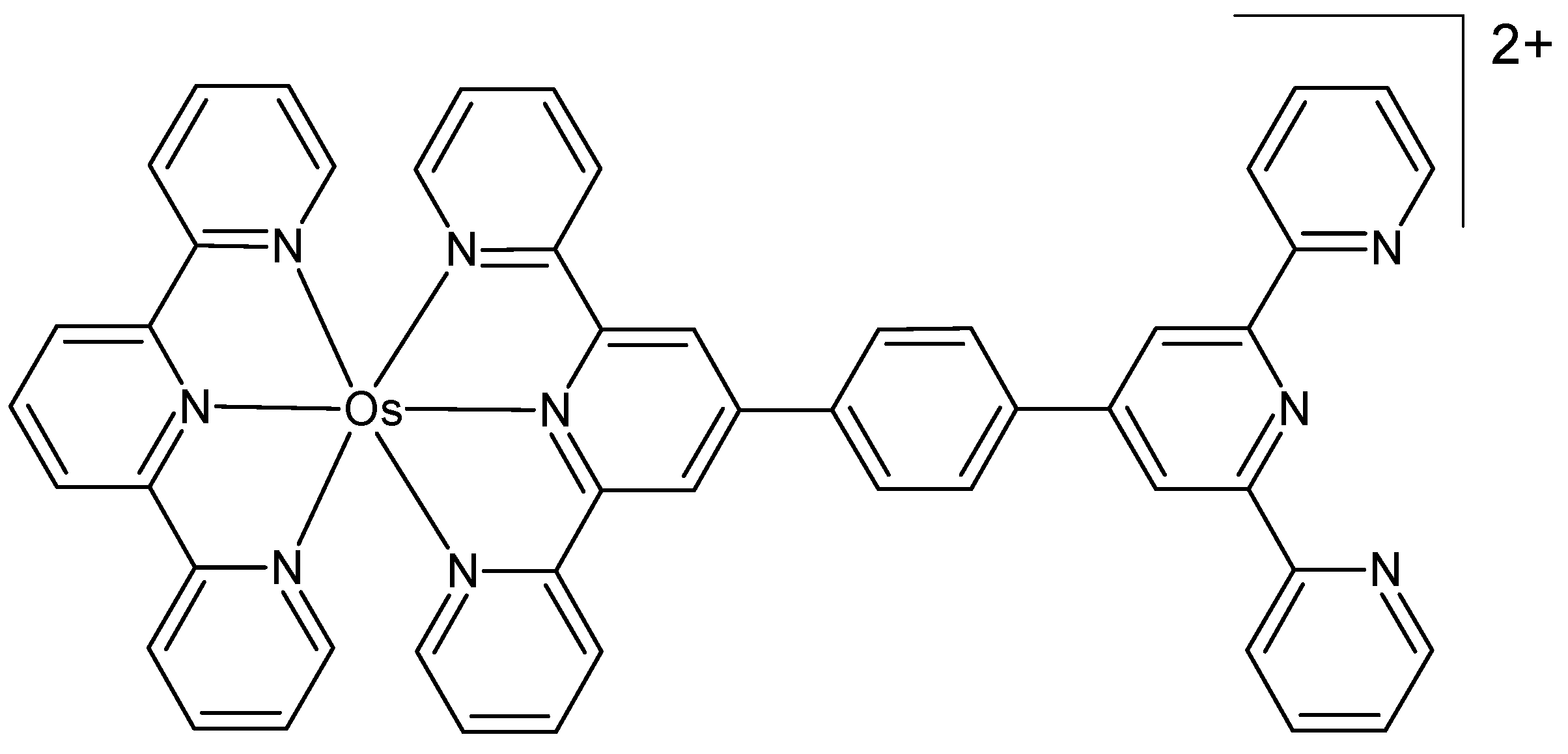

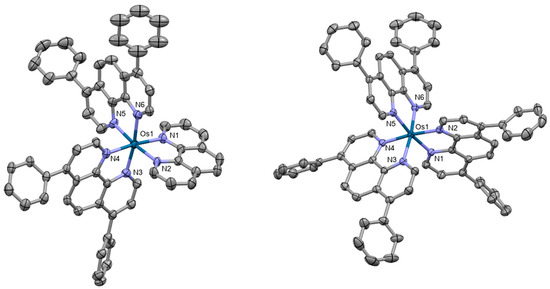

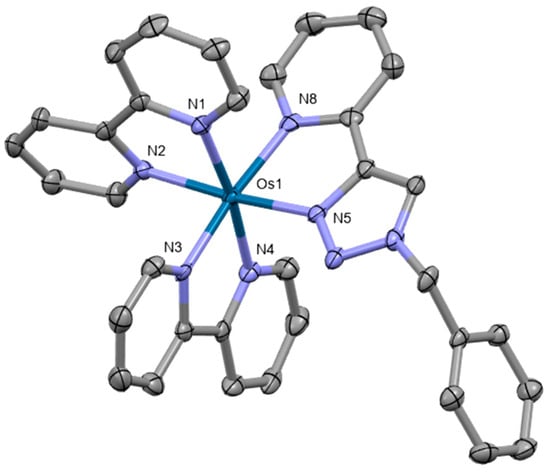

Five novel osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes with the general composition [Os(4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)2L]2+ were prepared as photosensitizers for PDT [72]. All complexes showed intense absorption in the NIR region. Single crystal X-ray diffraction studies of two of the complexes revealed distorted octahedral coordination with the central atom linked to two or three bathophenanthroline ligands (Figure 7). The complex [Os(4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)2(2,2′-bipyridine)]2+ exerted the highest activity in several cancer cell lines. These findings were further supported by experiments on CT26 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice.

Figure 7.

X-ray single-crystal structures of the complexes studied in [72] (CCDC 2175813, 2175814); partial numbering scheme, hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity, ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os green, N blue, C grey. Depiction of the structures with Mercury® software.

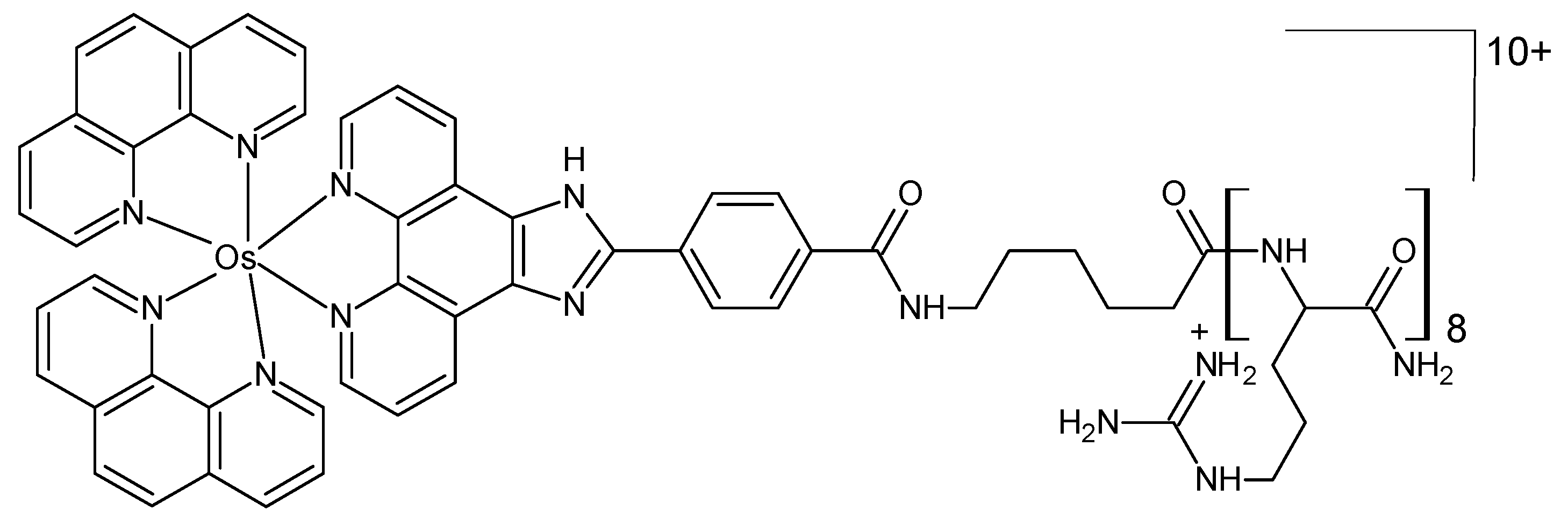

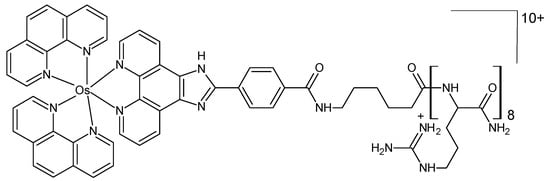

The complex osmium(II) (bis-2,2-bipyridyl)-2(4-carboxylphenyl)imidazo [4,5f][1,10] phenanthroline (Figure 8) was synthesized and linked to octaarginine, a cell-penetrating peptide [73]. A comparison was made between the properties and bioactivity of the osmium complex and those of its ruthenium analog. Neither the parent osmium complex nor its peptide conjugate was oxygen responsive. Their cytotoxicity in the Chinese hamster ovarian CHO and murine myeloma spleen SP2 cell lines was low in both complexes, in the dark as well as under irradiation with a continuous white light source.

Figure 8.

Chemical formula of the octaarginine conjugate complex [73].

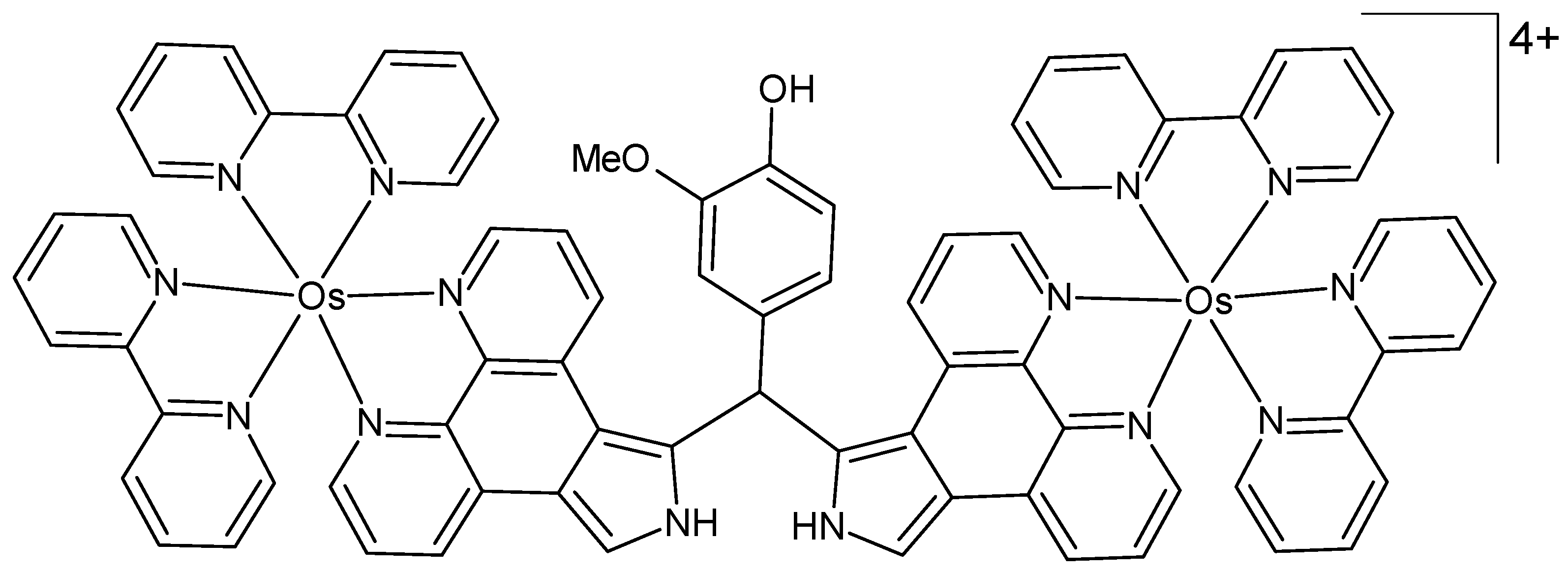

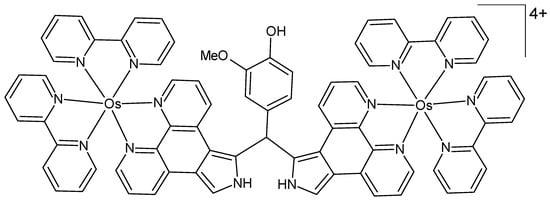

A new dinuclear osmium(II) polypyridyl-type complex bridged by (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)diphenanthropyrromethane was prepared as a potential phototherapeutic agent, and its binding to calf thymus DNA was investigated (Figure 9) [74]. The structure of the complex was characterized by UV/Vis spectroscopy, cyclic voltammetry, and elemental analysis. Photocleavage studies with circular plasmid DNA were performed under low-energy light irradiation, resulting in complete photocleavage of the DNA. Investigations on the mechanism of DNA photocleavage suggest that the activity arises from the formation of both 1O2 and oxygen radicals. The osmium(II) complex demonstrated significantly greater efficacy in photocleavage compared to its ruthenium analog.

Figure 9.

Chemical formula of the dinuclear osmium(II) complex described in [74].

Three new polypyridyl osmium-based photosensitizers were prepared, and their photophysical and photobiological properties were studied [75]. They are panchromatic (i.e., black absorbers), activable in the range of 200 to 900 nm, and show activity in normoxic and hypoxic conditions with both red and near-infrared light. Structural characterization by 1H NMR, ESI-MS, and HPLC was performed on their PF6 salts, followed by anion metathesis, which yielded the water-soluble Cl salts suitable for biological evaluation. The complexes were evaluated for their PDT efficacy in vitro using HT1376 and U87 cell lines. The inverse therapeutic ratio (Dark LD50/PDT LD50) was employed to compare the efficacy. Higher inverse therapeutic ratios were correlated with higher light-triggered efficacy and lower dark toxicity. These findings were further expanded upon by studies on CT26 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice.

Dröge et al. prepared a dinuclear osmium(II) complex, [{Os(TAP)2}2tpphz]4+, where tpphz = tetrapyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c:3″,2″-h:2‴,3‴-j]phenazine and TAP = 1,4,5,8-tetraazaphenanthrene [76]. The complex exhibited NIR emission within the biological optical window. Cell-based studies were conducted using the human ovarian cancer line A2780. These studies revealed that, in contrast to its ruthenium(II) analog, the new complex does not exhibit any significant levels of toxicity, either cytotoxic or photocytotoxic. The authors proposed it as a near-infrared cell imaging probe for optical microscopy due to its high photostability and cell permeability.

A symmetric osmium(II) [bis-(4′-(4-carboxyphenyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine)] complex was synthesized by Gkika et al. and linked to two mitochondrial-targeting peptide sequences [77]. The parent and conjugate complexes showed strong near-infrared emission. The complex was studied using confocal fluorescence imaging in HeLa and MCF-7 cells. Unlike the parent complex, the conjugated osmium (II) system was membrane permeable and demonstrated membrane permeation and the capacity to target mitochondria at concentrations below 50 μM. Gkika et al. also synthesized two polyarginine conjugates of an osmium(II) polypyridine complex [78]. The conjugates exhibited NIR emission, which was essentially oxygen-insensitive.

Pursuwani et al. reported the synthesis of osmium(IV) complexes based on a tetrazolo[1,5-a]quinoline ligand [79]. The proposed structure of the products was supported by elemental analysis and by NMR, IR, and MS spectra, suggesting a deformed octahedral geometry with the bidentate main ligand and four bromo-ligands surrounding the central atom. The complexes were evaluated for their photocytotoxicity in the HCT-116 cell line, with IC50 values of 121–342 μg/mL (in the dark) and 48–316 μg/mL upon irradiation. DNA binding and cleavage were studied as well.

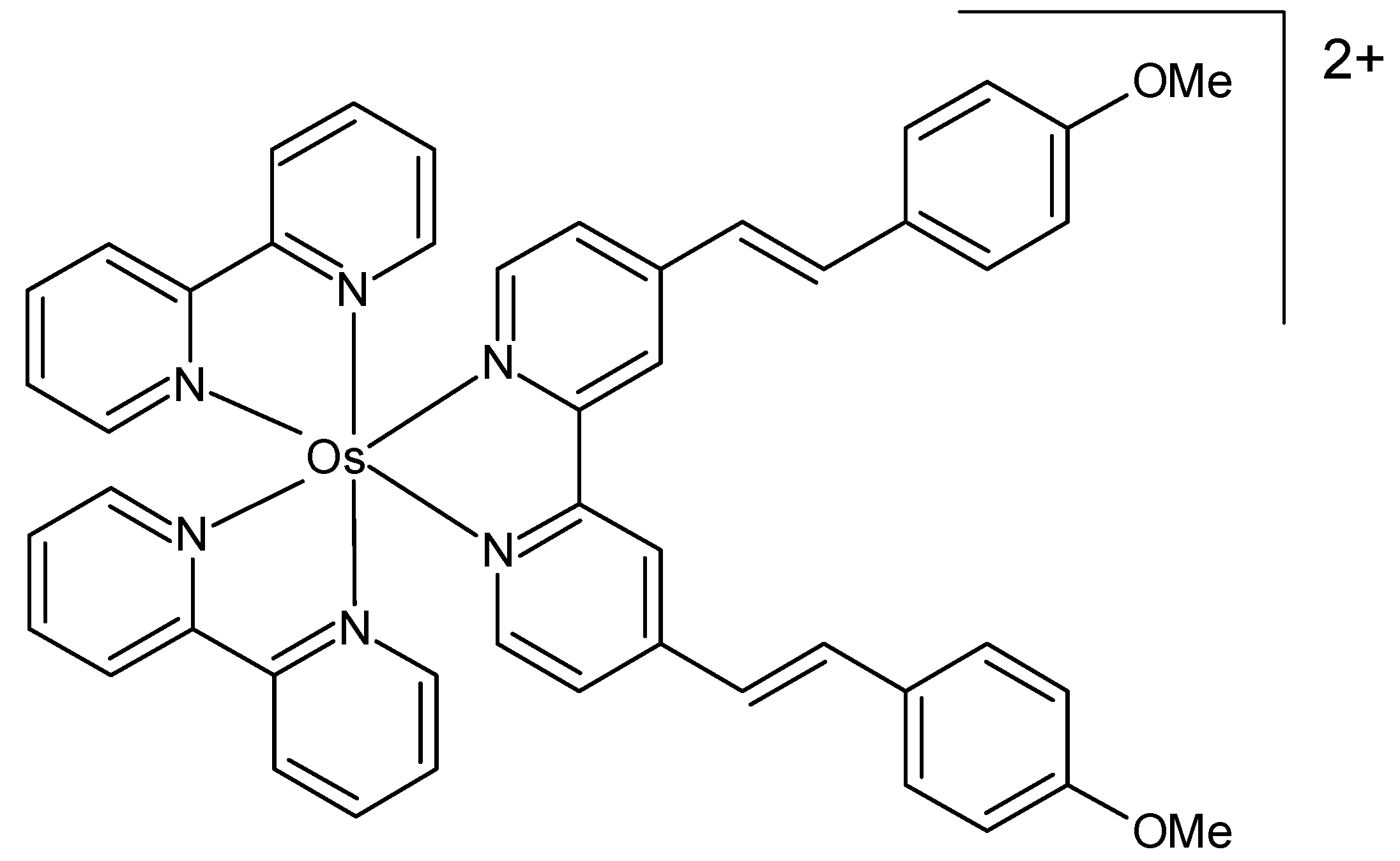

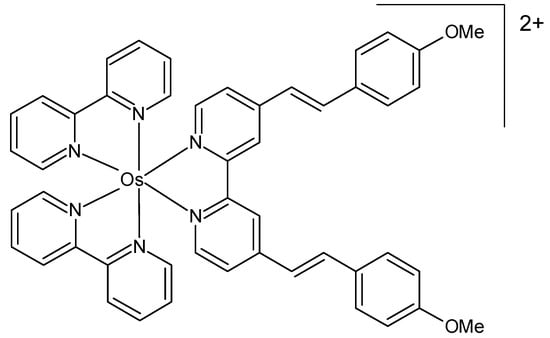

Eight new ruthenium(II) and osmium(II) complexes with substituted 4,4′-di(styryl)-2,2′-bipyridine ligands were designed as potential photosensitizers for PDT [80]. The identity of the complexes was verified by 1H and 13C NMR and HRMS, and their purity was confirmed by elemental analysis. An examination was conducted to ascertain the effect of modifications of the ligands on the spectroscopic, physical, and biological properties of the synthesized complexes. Slight alterations to the structure of the distyryl ligand demonstrated only a moderate effect on the visible light absorption and singlet oxygen quantum yield of the corresponding complexes, while having a considerable impact on the lipophilicity, cellular uptake, and phototoxicity of the compounds. Cytotoxicity in the dark and under light irradiation at 480 nm was studied in HeLa and RPE-1 cells. The osmium complex (Figure 10) was non-toxic in the dark and moderately phototoxic under irradiation.

Figure 10.

Chemical formula of a phototoxic osmium(II) complex described in [80].

In their report, Omar and colleagues described the preparation of a water-soluble theranostic osmium(II) complex targeting mitochondria, with the composition [Os(btzpy)2][PF6]2, where btzpy = 2,6-bis(1-phenyl-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)pyridine [81]. The complex exhibited phosphorescence at 595 nm. The structure of the compound was determined through spectroscopic methods and DFT calculations. The complex demonstrated a substantial quenching of luminescence intensity in the presence of oxygen, accompanied by a substantial quantum yield for singlet oxygen sensitization of luminescence intensity in the presence of oxygen and a high quantum yield for singlet oxygen sensitization. The cellular viability in HeLa cells was investigated in dark conditions, demonstrating no cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 100 μM.

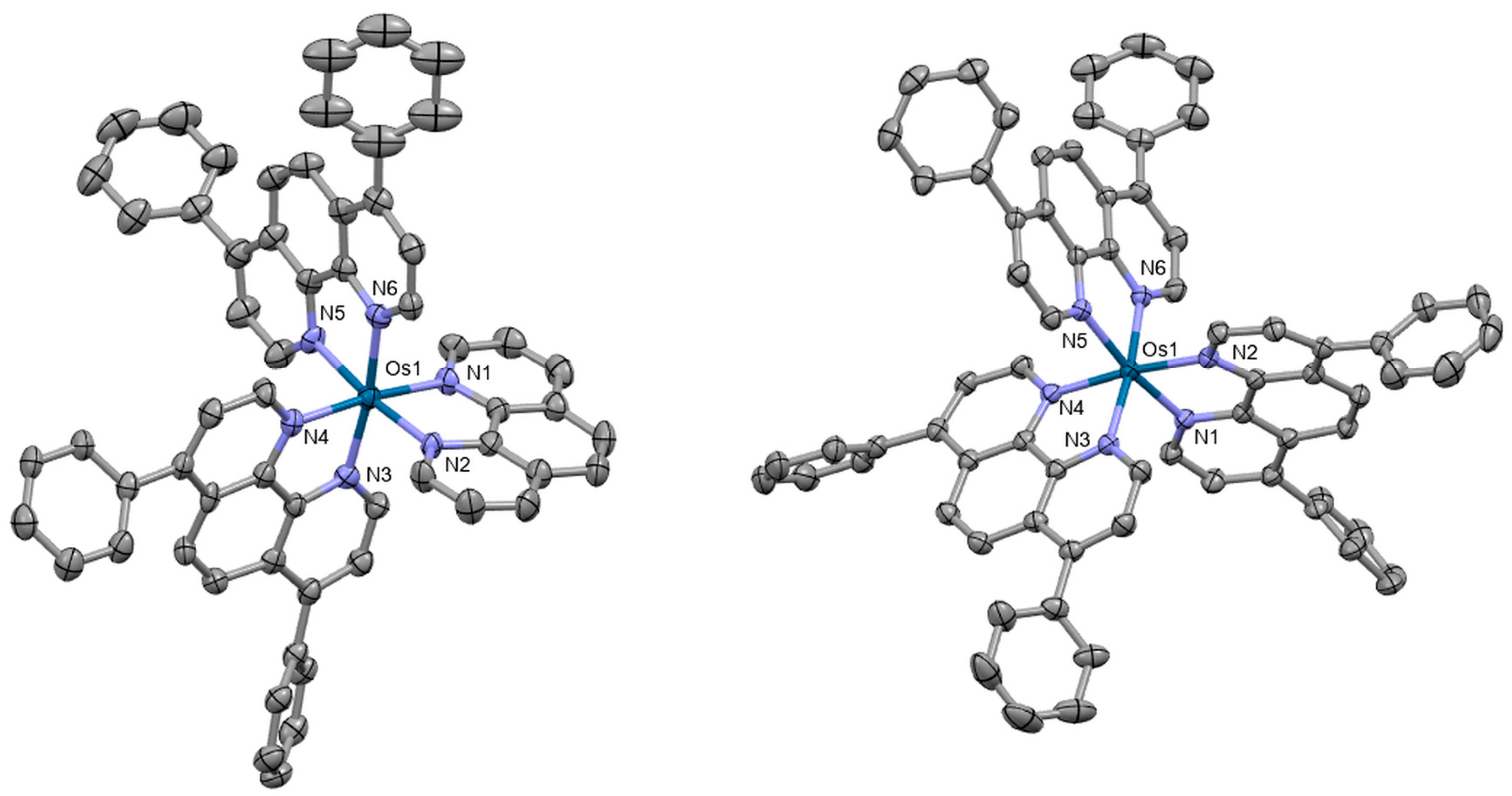

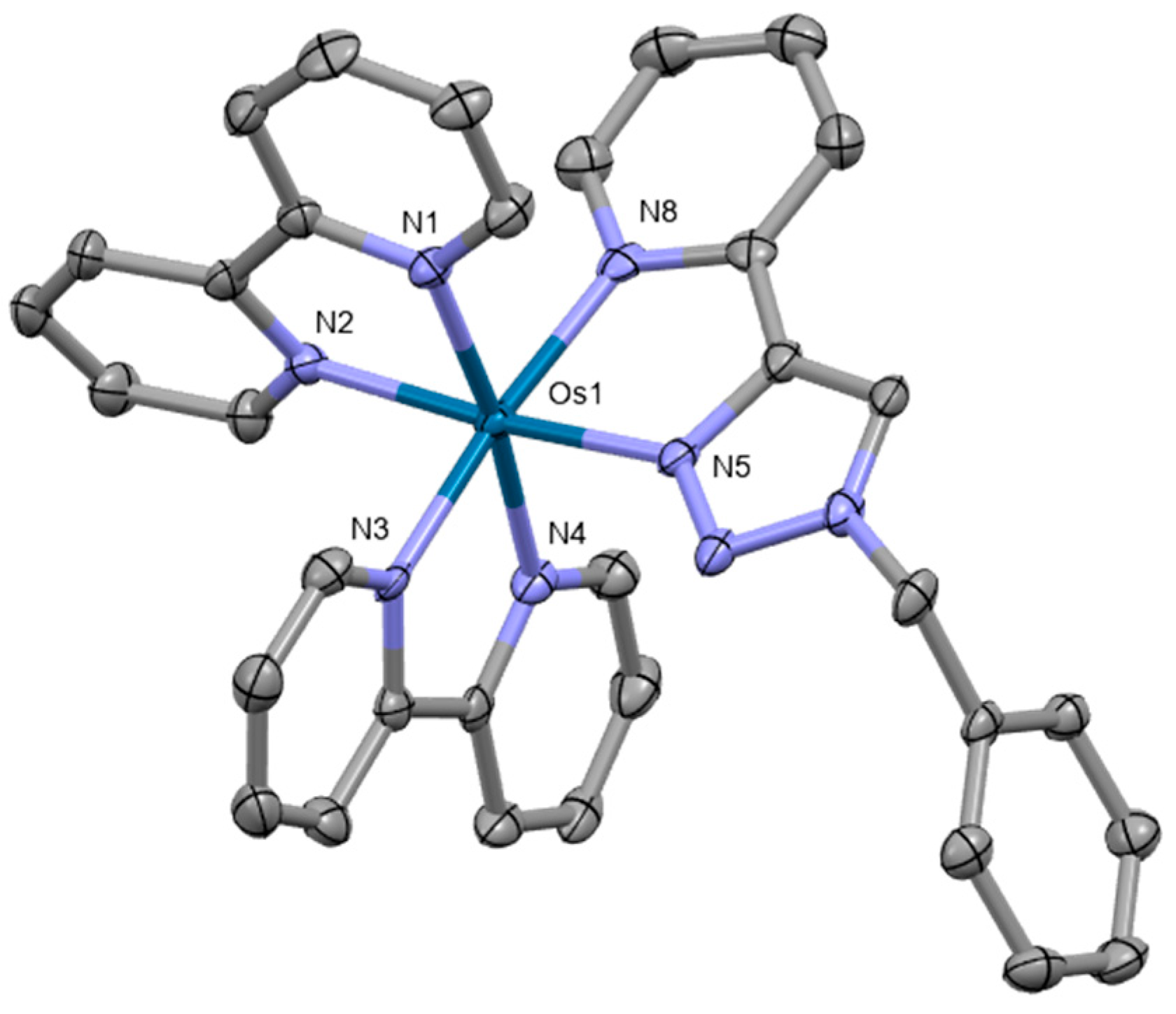

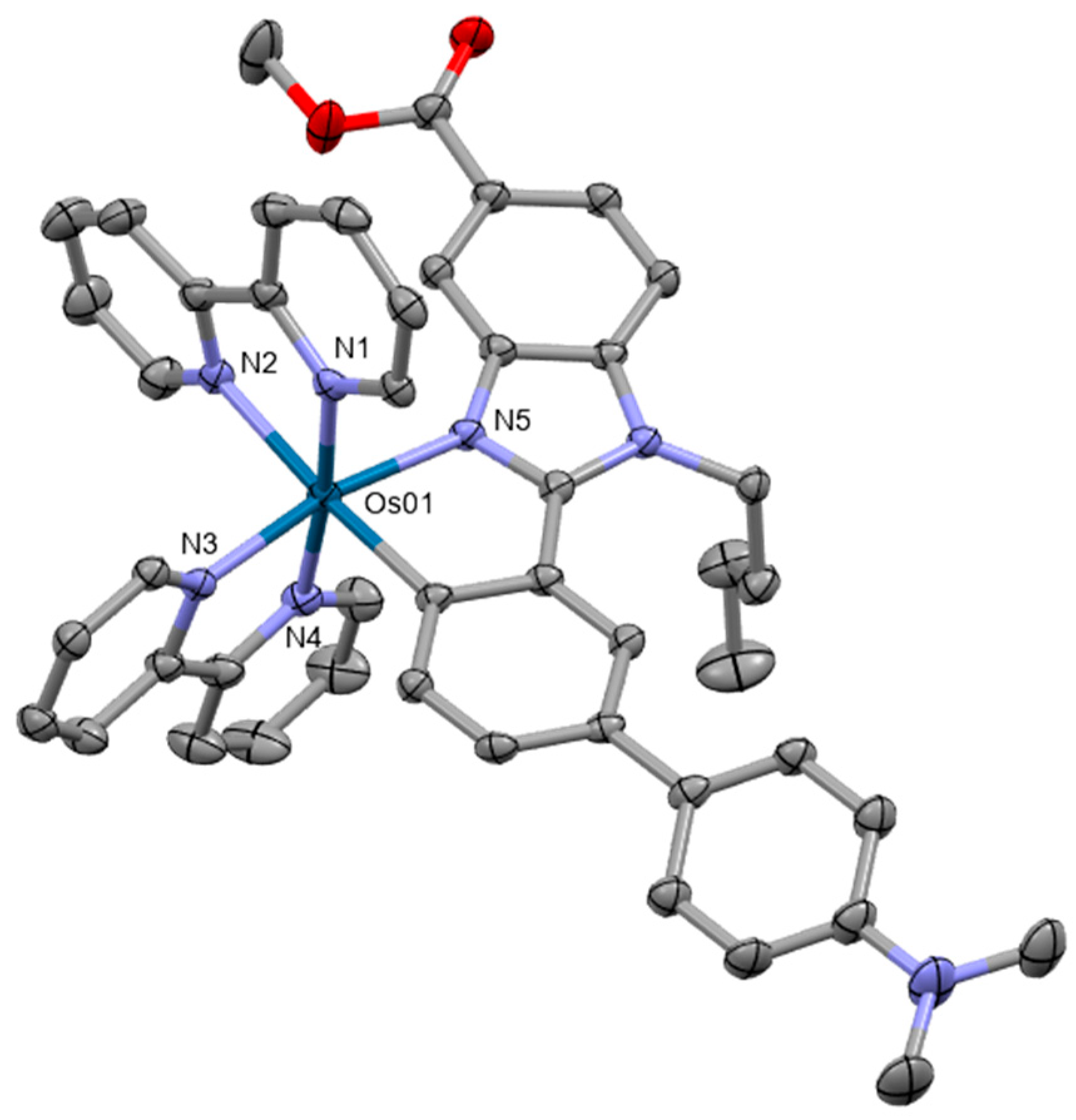

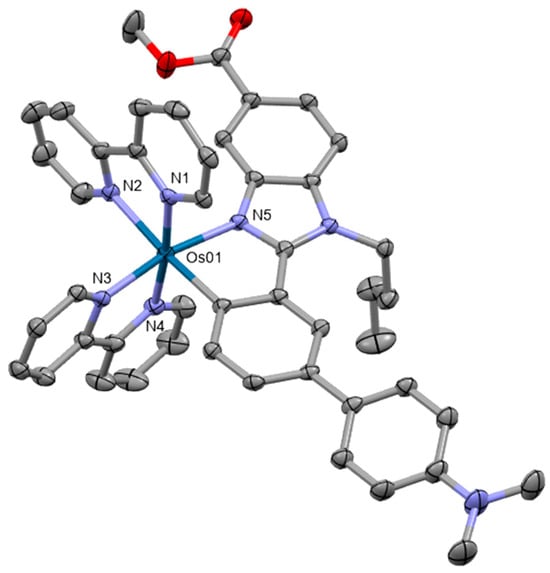

Osmium(II) pyridyltriazole complexes [Os(bpy)3−n(pytz)n][PF6]2 (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridyl, pytz = 1-benzyl-4-(pyrid-2-yl)-1,2,3-triazole, n = 0–3) were also prepared by Omar et al. [82]. Crystal structure was obtained for the compound [Os(bpy)2(pytz)]2+ (Figure 11). The complex crystallizes in the space group P21/n, adopting a distorted octahedral geometry. The complexes were investigated for their potential as phosphorescent cellular imaging agents. Cytotoxicity in the dark as well as long-term viability were evaluated in the bladder cancer (EJ) cell line and the HeLa cervical cancer cell line, indicating that the complexes have comparatively low dark toxicity levels in both cell lines. Preliminary experiments to assess photocytotoxicity were conducted upon 455 nm irradiation, demonstrating no photoactivated cytotoxicity.

Figure 11.

X-ray single-crystal structure of the complex studied by Omar et al. [82] (CCDC 1826209); partial numbering scheme, hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity, ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os green, N blue, C grey. Depiction of the structure with Mercury® software.

Cyclometalated complexes represent a noteworthy category of novel anticancer compounds [83,84]. They are organometallic complexes where a metal atom is directly bonded to a carbon atom in an organic ligand, forming a chelate ring through an intramolecular coordination with a heteroatom. Hernández-García reported the synthesis and characterization of six cyclometalated benzimidazole osmium(II) complexes [85]. They were thoroughly investigated by 1H and 13C or DEPT NMR and ESI-MS. The crystal structure of one of the complexes was examined by means of single-crystal X-ray analysis (Figure 12). The complex exhibits an octahedral geometry at the central atom. The phototoxic activity of Os complexes was determined in several cancer cell lines. The present investigation utilized two-dimensional monolayer cancer cell lines and three-dimensional multicellular tumor spheroids under dark conditions and green light irradiation. The complexes exhibited significantly higher potency compared to the standard cisplatin treatment. On the other hand, photoactivation under hypoxic conditions was only inferior.

Figure 12.

X-ray single-crystal structure of the osmium complex from [85], CCDC 2226215; partial numbering scheme; hydrogen atoms, counterions, and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity; ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os green, N blue, O red, C grey. Depiction of the structure with Mercury® software.

4. Other Cytotoxic Non-Arene Osmium Complexes

A novel series of osmium(III) complexes with pyrazinamide and its structural analogs has been synthesized by Biedulska et al. Mass spectrometry, FT-IR, 1H-NMR, elemental, and thermogravimetric analyses were used to confirm their structures [86]. Thus, the authors propose bidentate binding of selected pyrazine derivatives, as well as coordination to the central atom involving the azomethine and amine nitrogen atoms. The biological safety of OsIII complexes was evaluated by measuring their cytotoxicity in two non-cancerous cell lines: immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) and primary bovine fibroblasts. The MTS assay showed no significant cytotoxic activity against these healthy cell lines at the tested concentrations (1–1000 μM). Electroanalytical studies suggest that the complexes may be selectively reduced in hypoxic tumor environments, thus leading to selective cytotoxicity.

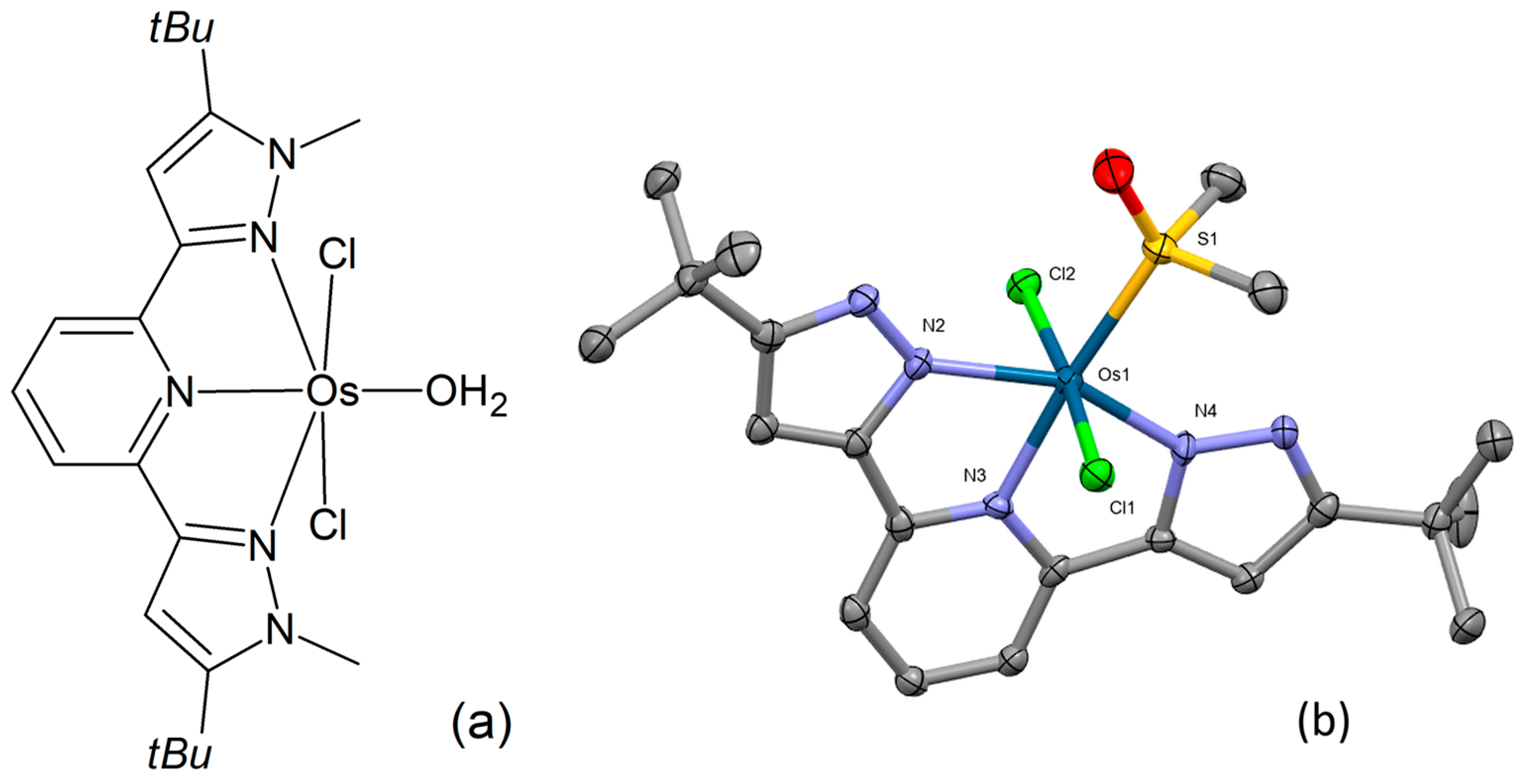

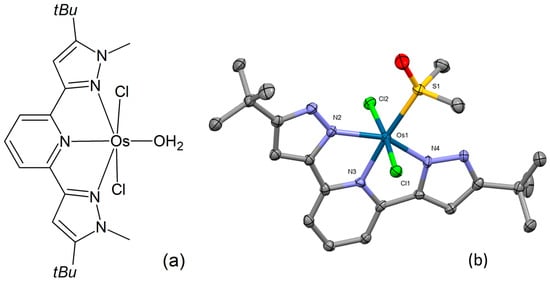

Preparation and structural characterization of three novel osmium(II) complexes were reported by Petrović and co-workers [87]. Their chemical composition corresponds to the general formula [OsIILCl2(H2O)], where L = 2,6-bis(5-tert-butyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)pyridine, 2,6-bis(5-tert-butyl-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)pyridine, and 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine, respectively. The chemical structure of one of the complexes (Figure 13a) was examined through single-crystal X-ray analysis (Figure 13b). This distorted octahedral complex features a nearly planar tridentate N,N,N-donor ligand in a mer arrangement. Crystallization from a DMSO/water mixture resulted in the replacement of the coordinated water molecule with DMSO. The osmium atom is located above the bis(pyrazolylpyridine)-ligand plane, while the sulfur donor atom of the coordinating DMSO resides within the ligand plane. The chlorides exhibit an axial orientation. The binding affinities of the complexes under examination to biologically significant molecules, CT-DNA, and HSA were investigated by means of UV-Vis spectrophotometry, fluorescence spectroscopy, and gel electrophoresis, showing moderate interaction. Substitution reactions with GSH, L-Met, and 5′-GMP were also examined. The evaluation of the complexes’ cytotoxicity in the HCT-116, SW-480, MRC-5, and HeLa cell lines demonstrated marked activity in several instances.

Figure 13.

Chemical formula (a) and X-ray single-crystal structure (b) of an osmium(II) complex with a bis(pyrazolylpyridine)-ligand [87], CCDC 2045190; partial numbering scheme; hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity; ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os dark green, Cl light green, N blue, O red, S yellow, C grey. Depiction of the structure with Mercury® software.

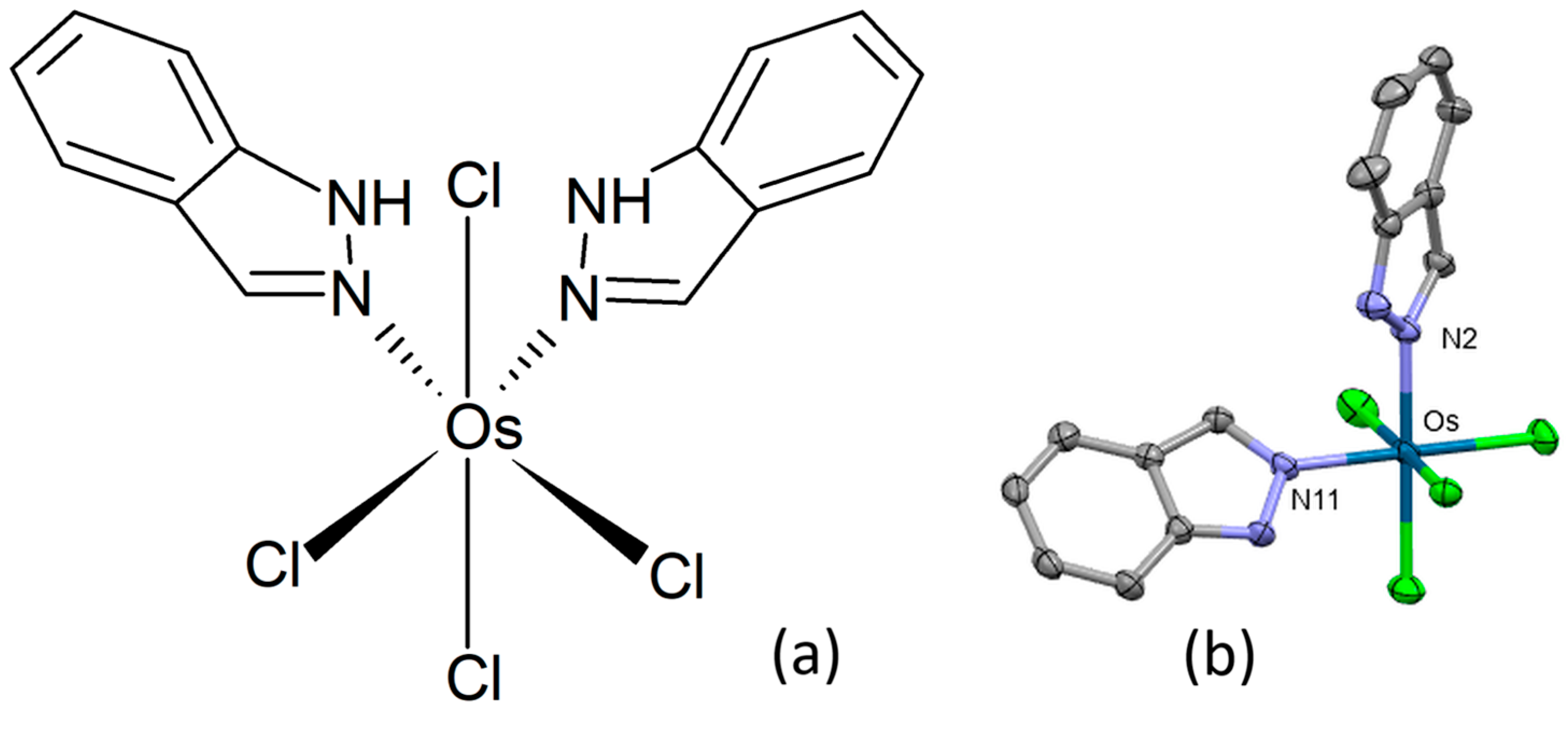

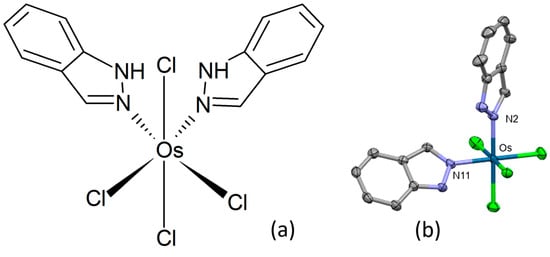

In order to investigate the effect of geometrical isomerism on anticancer activity of octahedral metal complexes, Büchel and co-workers prepared cis-tetrachlorido-bis(indazole)osmium(IV) (Figure 14a) and its osmium(III) congeners [88]. The title complex crystallized in the monoclinic centrosymmetric space group P21/c, the osmium atom displaying a distorted octahedral coordination geometry (Figure 14b). Two 1H-indazole ligands and two chlorido ligands were found in equatorial positions, with the remaining two chlorido ligands bonded axially. The title complex, its sodium salt, and a reduced congener showed antiproliferative effects in HT29 and 4T1 cancer cell lines. HT29 cells demonstrated a higher degree of susceptibility to treatment with osmium complexes compared to cisplatin, while the 4T1 cell line exhibited a reduced propensity for apoptosis induction by osmium complexes in comparison to cisplatin. A very high cytostatic activity was detected for the sodium salt of the cis-configured osmium(III) complex.

Figure 14.

Chemical formula (a) and X-ray single-crystal structure (b) of cis-tetrachlorido-bis(indazole)osmium(IV) complex [88], CCDC 1544885; partial numbering scheme, hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity, ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os dark green, Cl light green, N blue, C grey. Depiction of the structure with Mercury® software.

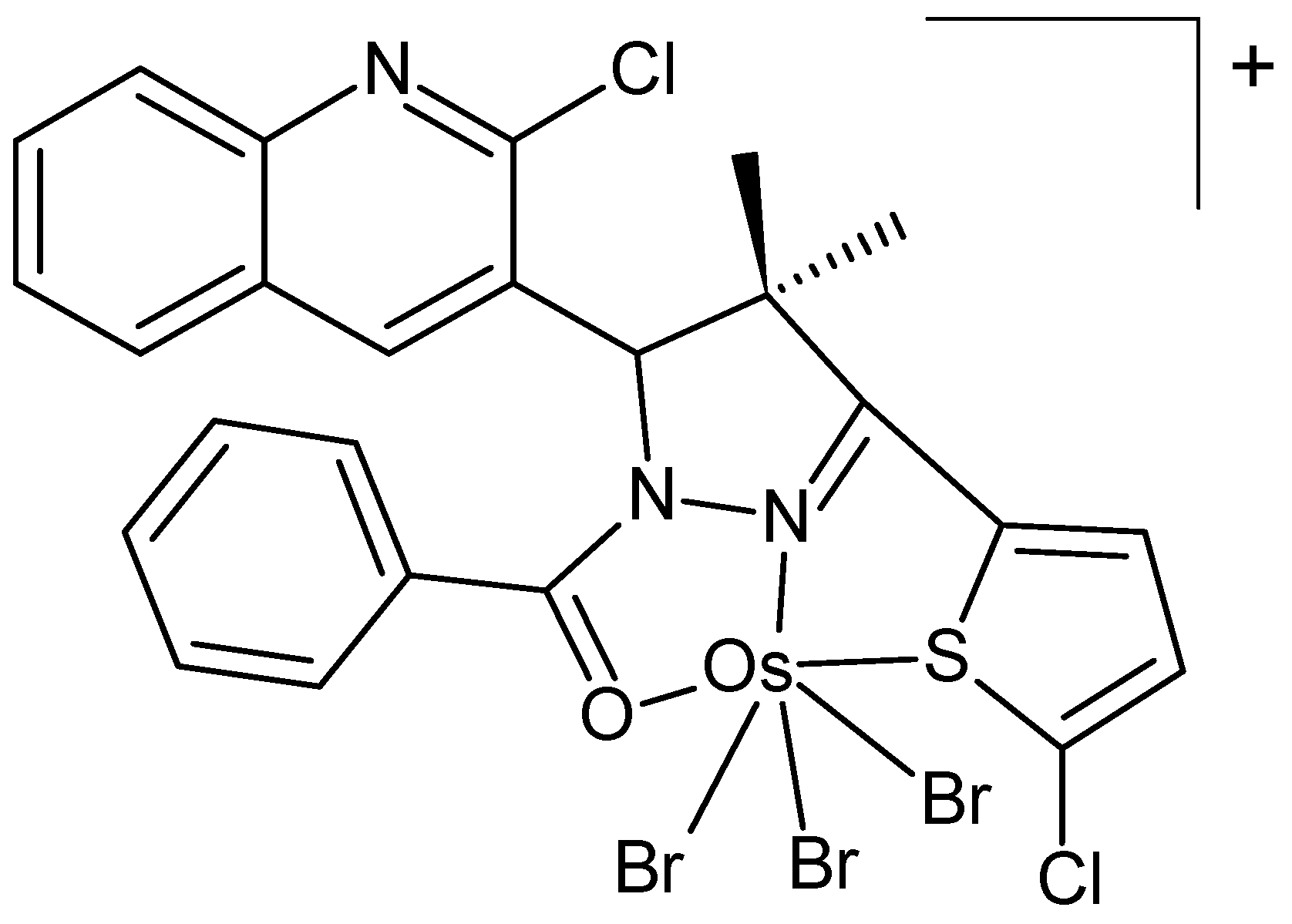

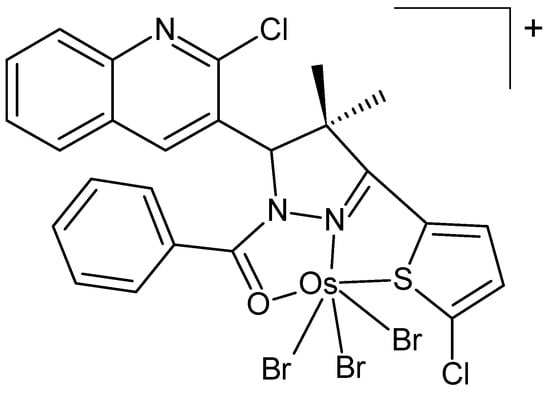

Osmium(IV) complexes with ligands containing the pyrazole moiety were developed by Pursuwani et al. [89]. Their structure was investigated by IR- and electronic spectroscopy, ESI-MS, ICP-OES, magnetic measurements, and conductance. All complexes were paramagnetic with octahedral geometry. Most complexes show only moderate IC50 values in the lung cancer cell line A549. However, the occurrence of the thiophene ring exerted a substantial influence on cytotoxic activity, with the complex depicted in Figure 15 demonstrating the best performance. Pursuwani et al. prepared similar osmium(IV) complexes based on pyrazole and quinoline moieties [90] and characterized them by common analytical techniques. Their cytotoxicities were measured using the HCT-116 cell line, showing moderate IC50 values.

Figure 15.

Chemical formula of an osmium (IV) complex with a pyrazole nucleus [89].

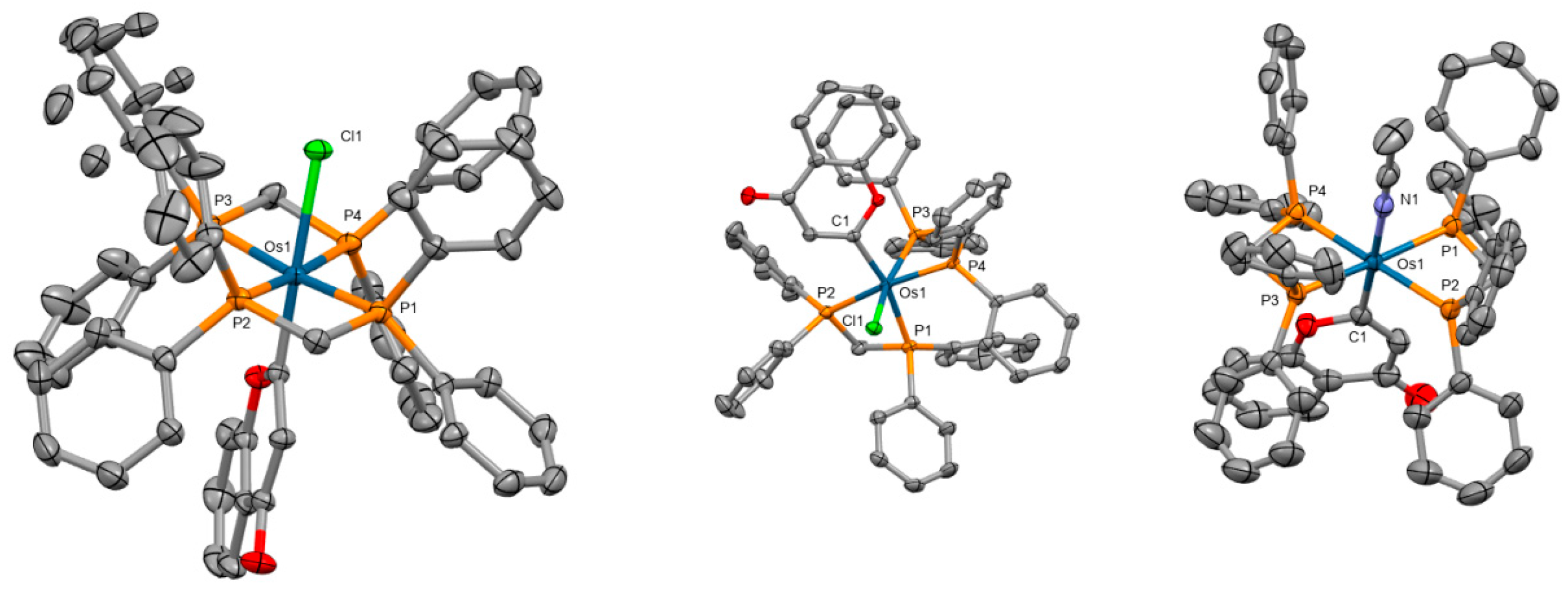

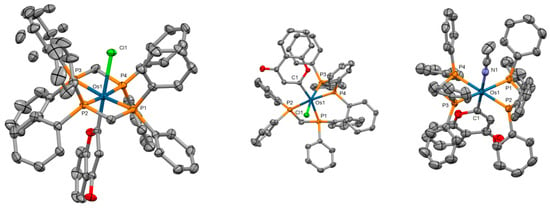

Diphosphine-containing osmium(II) and ruthenium(II)−chromene and chromone complexes were prepared, and their structure was investigated by single-crystal X-ray analysis [91]. The osmium atom displays a distorted octahedral geometry, binding to a Cl/CH3CN ligand, two κ2-dppm ligands, and a monodentate chromene/chromone ligand (Figure 16). The in vitro anticancer activities of the studied compounds were evaluated against cervical carcinoma (HeLa), breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), fibrosarcoma (HT1080), and lung adenocarcinoma (A549) human cell lines by means of the MTT assay. Most complexes possessed moderate to strong cellular toxicity towards the examined human cancer cell lines.

Figure 16.

X-ray single-crystal structures of the osmium complexes studied in [91] (CCDC 1979800–1979802); partial numbering scheme; hydrogen atoms, counterions, and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity; ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os dark green, Cl light green, N blue, P orange, O red, C grey. Depiction of the structures with Mercury® software.

Stitch et al. [92] designed two novel osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes, [Os(TAP)2dppz]2+ and [Os(TAP)2dppp2]2+, with dppz (dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) and dppp2 (pyrido[2′,3′:5,6]pyrazino[2,3-f][1,10]phenanthroline) intercalating ligands as well as TAP (1,4,5,8-tetraazaphenanthrene) ancillary ligands. These complexes were developed as novel cellular imaging agents designed to target DNA and were characterized by photophysical methods. The cytotoxicity of both complexes was measured in a cell viability assay on HeLa cells, with the IC50 values of 45 and 90 μM, respectively.

Mardanya and co-workers reported the preparation, characterization, and DNA binding affinities, as well as photophysical and electrochemical studies of two homobimetallic Ru(II) and Os(II) complexes [93]. They employed a novel bridging ligand composed of two pyridyl-imidazole coordinating units that were rigidly coupled with the central pyrene moiety. Only the diruthenium complex was structurally described by X-ray crystallography. The dinuclear osmium(II) complex demonstrated notably better binding properties in relation to its Ru(II) analog. The authors have also reported a mixed-ligand osmium(II) complex containing pyrenyl−pyridylimidazole and 2,2′-bipyridine ligands [94]. The complex was shown to efficiently intercalate calf-thymus DNA. An X-ray crystallographic study revealed that the complex crystallized in the triclinic system, with a distorted octahedral geometry and the central atom of osmium six-coordinated.

High-valent metal complexes represent an innovative category of potential anticancer metallodrugs. Among them, nitrido-osmium(VI) complexes [95,96] have been a subject of increasing research attention due to their distinctive and unconventional mode of action. Berger et al. studied the efficacy of osmium(VI) nitrido compounds on glioblastoma initiating cells in vitro and in vivo using conventional MTT and 3D cytotoxicity assays, indicating efficiency at low micromolar concentrations, as well as in mice bearing patient-derived glioma neurospheres extracted from malignant high-grade gliomas [97]. Both tested OsVI complexes exhibited marked therapeutic activity in vivo against glioblastoma, significantly increasing survival in mice. Cell cycle analysis, cellular distribution, and osmium uptake studies provided further insight into the anticancer properties of the complexes.

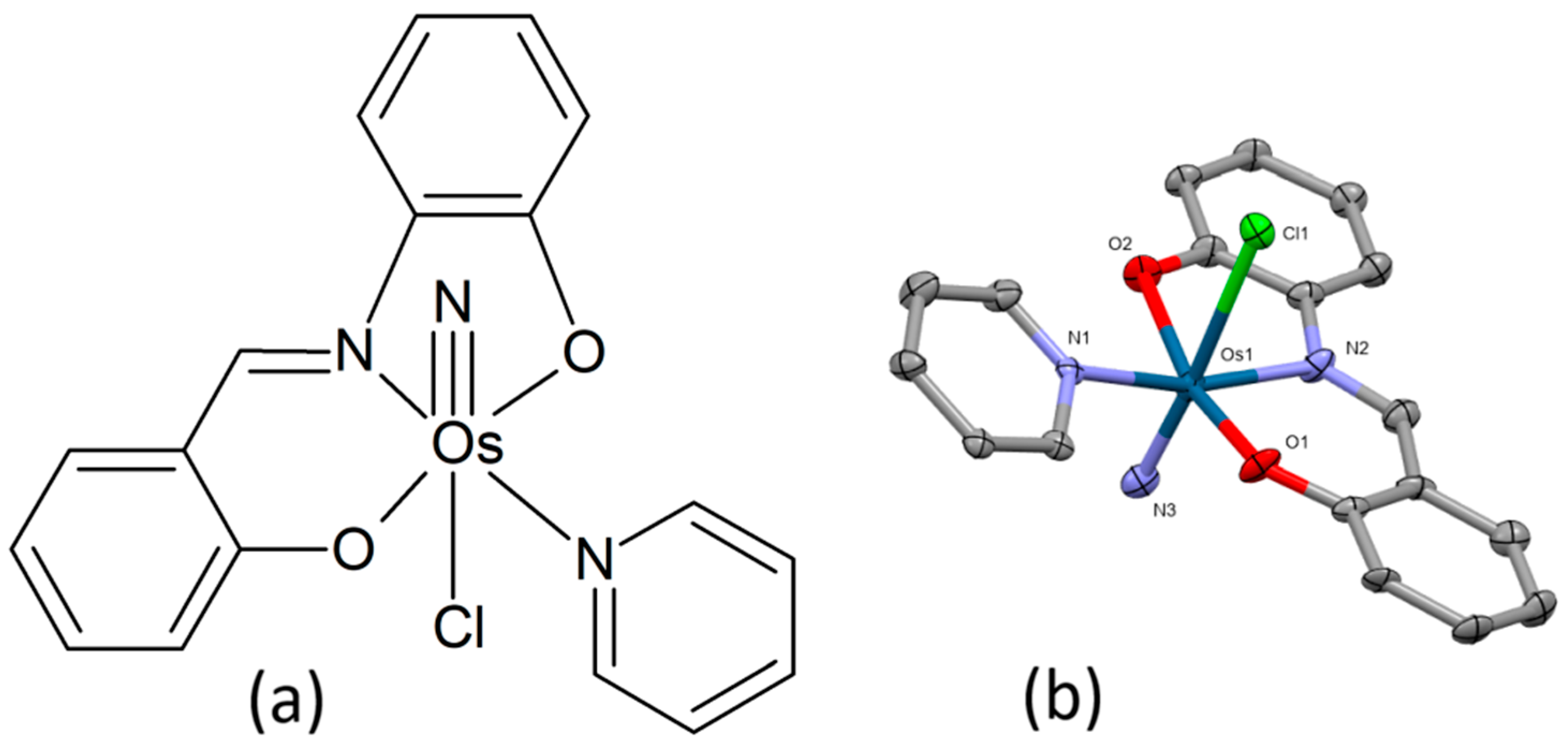

Huang et al. described the preparation of three nitrido-osmium(VI) complexes with the composition [OsVI(N)(sap)(py)Cl], [OsVI(N)(sap)(pz)Cl], and [OsVI(N)(sap)(MeIm)Cl] (sap = N-salicylidene-2-aminophenol, py = pyridine, pz = pyrazole, MeIm = 1-methylimidazole) [98]. Due to its favorable solubility and stability in water solution, [Os(N)(sap)(py)Cl] (Figure 17a) was selected as a potential anti-cancer candidate compound for a more thorough examination. Its molecular structure was examined using X-ray crystallography. The central atom displays a distorted octahedral geometry with the osmium atom linked to one tridentate sap ligand, one N3−, one Cl−, and one py ligand (Figure 17b). An evaluation of the in vitro antiproliferative activities was conducted using a panel of cancer cell lines, including cisplatin-resistant cells (IC50 values of 2.8–13.8 μM). The complex was also found to interfere with the induction of G2/M phase arrest, reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential, and induction of caspase-mediated apoptosis through the activation of mitochondrial (intrinsic) and death receptor (extrinsic) pathways in HepG2 cells. The antitumor efficacy in vivo of the osmium(VI) complex was studied in HepG2-bearing nude mice. Compared to cisplatin, the complex displayed good anti-cancer activity with a low propensity to toxic side effects.

Figure 17.

Chemical formula (a) and X-ray single-crystal structure (b) of the osmium(VI) nitrido-complex [98], CCDC 1982872; partial numbering scheme, hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules omitted for clarity, ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level. Color code: Os dark green, Cl light green, N blue, O red, C grey. Depiction of the structure with Mercury® software.

The osmium(VI) nitrido complex Na[Os(N)(tpm)2], where tpm = [5-(thien-2-yl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]methanol, was shown to have a more pronounced inhibitory effect on the cell viability than cisplatin for cervical, ovarian, and breast cancer cell lines [99]. It induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HepG2 cells. The observed activation of caspases and the occurrence of oxidative stress in the cells subsequent to treatment with the compound indicate that apoptosis involves intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways. Additionally, the study demonstrated a significant downregulation of DNA-metabolism-associated proteins and an upregulation of oxidative-stress-associated proteins. The findings indicate that the complex has the potential to reduce DNA repair capacity and augment DNA damage accumulation. The complex crystallizes in the orthorhombic crystal system (space group P212121), as determined by X-ray crystal structure analysis. The structure is based on the osmium center linked to two deprotonated tpm ligands and one nitrido ligand (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Chemical formula of the osmium(VI) nitrido-complex reported in [99].

The Os(VI) nitrido complex [OsN(PhenOH)Cl3] was designed and synthesized as an efficient radiosensitizer with low toxicity by Chen et al. The complex has been shown to promote G2/M cell cycle arrest by augmenting intracellular ROS levels. This, in turn, activates the mitochondrial pathway and prompts DNA damage in response to X-ray irradiation [100]. The complex showed low toxicity against human cervical cancer (Caski and HeLa) and particularly against normal cervical cell lines (E6E7/Ect). Subsequent to the combination treatment involving the Os drug and X-ray, there was a marked enhancement in the anticancer efficacy, with an observed increase exceeding 500%.

The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway has been identified as a promising target for cancer treatment, e.g., by the disruption of the HIF-1α–p300 protein–protein interaction. Yang et al. prepared seven polypyridyl osmium(II) complexes and subsequently identified the complex that exhibited the highest degree of potential as an inhibitor of the HIF-1α–p300 interaction, based on a methyl-substituted phenanthroline ligand [101]. The complex was found to inhibit hypoxia response element (HRE)-dependent expression, exhibiting an IC50 of approx. 1.22 μM in hypoxic MC3T3-E1 cells. Notably, it demonstrated a higher potency compared to chetomin, a known HIF-1α–p300 interaction inhibitor, under similar experimental conditions.

Another appealing therapeutic strategy for the treatment of hematologic malignancies and inflammation is the targeting of STAT5 (signal transducer and activator of transcription), a family of transcription factors activated by tyrosine kinases. Liu et al. reported on a novel osmium(II) complex as the first metal-based inhibitor of STAT5B dimerization [102]. The complex is based on chlorine-substituted dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (dppz) ligand and 2,2′-bipyridine coligands. Its structure was characterized by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and elemental analysis. The complex was able to inhibit in vitro STAT5B DNA-binding, STAT5B phosphorylation, STAT5 dimerization, and transcription inhibition in cellulo.

5. Conclusions

This brief review summarizes the research on cytotoxic complexes of osmium published during the last decade, focusing on non-arene complexes, which constitute a distinct category of compounds compared to complexes with π-bonding arene ligands. Depictions of their single-crystal X-ray structures were included where available. On the one hand, these complexes are of interest due to their general cytotoxic properties, analogous to the already established use of cytotoxic platinum complexes. They mainly contain central atoms of osmium in the oxidation state II, although a number of complexes with higher oxidation numbers (III, IV, VI) displayed very good cytotoxic activities. Of particular interest among the latter are osmium(IV) complexes containing the nitrido ligand, due to their potentially distinctive mechanism of action and, consequently, a broader spectrum of activity. An advantageous combination treatment involving an Os(VI) nitrido complex and X-ray treatment was also reported. Investigations have been conducted into the potential for a targeted therapy approach, involving the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT5) as possible targets.

Another current and promising research direction involves the application of osmium complexes in photodynamic therapy. These are mainly Os(II) complexes containing one or several polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives, often polypyridyl-type ligands. Comparisons could be drawn with the structurally and chemically analogous ruthenium complexes, which also demonstrate significant photocytotoxicities. A shift in the optical window for activation (the wavelength of the applied radiation) and a change in efficiency have been observed upon the transition from Ru(II) to the heavier Os(II). Several attempts have also been made to design osmium complexes that exhibit selective cytotoxicity in hypoxic conditions. Other innovative approaches involve the preparation of mitochondria-targeted compounds or the design of theranostic osmium complexes, which combine therapeutic efficacy with imaging capabilities. A notable category of osmium compounds, the cyclometalated complexes, has the potential to exhibit a distinct mechanism of anticancer action, making them a significant subject of interest in the field.

A brief summary of the research on mono- and oligonuclear osmium complexes presented in this review is given in Table 1, including the oxidation number of the central atom(s), the counterion (if present), the type of assay used to assess the cytotoxicity of the compounds, and the employed cell lines, as well as an indication of the availability of in vivo bioactivity studies and of single-crystal X-ray diffraction structural data.

Table 1.

Cytotoxic osmium complexes mentioned in this survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.; methodology, L.H.; validation, A.D.; investigation, L.H. and A.D.; resources, L.H.; data curation, L.H. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H.; writing—review and editing, L.H. and A.D.; visualization, L.H.; supervision, L.H.; project administration, L.H.; funding acquisition, L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Republic VEGA (Project No. 1/0661/24) and by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-23-0349.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The depictions of the single-crystal X-ray structures were prepared from the corresponding cif files (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre) using the program MERCURY [103].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Henneberg, M. Cancer incidence increasing globally: The role of relaxed natural selection. Evol. Appl. 2017, 11, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjos, K.D.; Orvig, C. Metallodrugs in medicinal inorganic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4540–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczynska, A.; Lewinski, A.; Pokora, M.; Paneth, P.; Budzisz, E. An overview of the potential medicinal and pharmaceutical properties of Ru(II)/(III) complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Babak, M.V.; Hartinger, C.G. Development of anticancer agents: Wizardry with osmium. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, H. Future potential of osmium complexes as anticancer drug candidates, photosensitizers and organelle-targeted probes. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 14841–14854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkankit, C.C.; Marker, S.C.; Knopf, K.M.; Wilson, J.J. Anticancer activity of complexes of the third row transition metals, rhenium, osmium, and iridium. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 9934–9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Menches, S.M.; Gerner, C.; Berger, W.; Hartinger, C.G.; Keppler, B.K. Structure-activity relationships for ruthenium and osmium anticancer agents—Towards clinical development. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 909–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D. The discovery of iridium and osmium. Platin. Met. Rev. 1961, 5, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enghag, P. Platinum Group Metals. In Encyclopedia of the Elements; WILEY-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson, S.R.; Schröder, M. Osmium: Inorganic and Coordination Chemistry. In Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, R.J.; O’Farrelly, J. Platinum-Group Metals. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, W.P. Osmium and its compounds. Q. Rev. Chem. Soc. 1965, 19, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, S.A. Chemistry of Precious Metals; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S.E. The Chemistry of Ruthenium, Rhodium, Palladium, Osmium, Iridium and Platinum; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Albertin, G.; Antoniutti, S.; Baldan, D.; Bordignon, E. Preparation and properties of new dinitrogen osmium(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 6205–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, I. Anticancer metallocenes and metal complexes of transition elements from groups 4 to 7. Molecules 2024, 29, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambanda, A.; Kanyora, A.K.; Ongoma, P.; Gichumbi, J.; Omondi, R.O. Chlorido-(η6-p-cymene)-(bis(pyrazol-1-yl)methane-κ2N,N′)osmium(II) tetrafluoroborate, C17H22BClF4N4Os. Molbank 2022, 2022, M1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M. Osmium tetraoxide cis hydroxylation of unsaturated substrates. Chem. Rev. 1980, 80, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, W.P. Organic oxidations by osmium and ruthenium oxo complexes. Trans. Met. Chem. 1990, 15, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.C.; VanNieuwenhze, M.S.; Sharpless, K.B. Catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2483–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, K.R.; Kallman, F. The properties and effects of osmium tetroxide as a tissue fixative with special reference to its use for electron microscopy. Exp. Cell Res. 1953, 4, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wildenberg, G.; Boergens, K.; Yang, Y.; Weber, K.; Rieger, J.; Arcidiacono, A.; Klie, R.; Kasthuri, N.; King, S.B. OsO2 as the contrast-generating chemical species of osmium-stained biological tissues in electron microscopy. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Laserstein, P.; Helmstaedter, M. Large-volume en-bloc staining for electron microscopy-based connectomics. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrones Reyes, J.; Kuimova, M.K.; Vilar, R. Metal complexes as optical probes for DNA sensing and imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 61, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Murchie, A.I.H. Osmium tetroxide as a probe of RNA structure. RNA 2017, 23, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Delile, S.; Jabri, M.; Adamo, C.; Fave, C.; Marchal, D.; Perrier, A. Interaction of osmium(II) redox probes with DNA: Insights from theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 30029–30039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Feng, F.P.; Huang, C.H.; Mao, L.; Tang, M.; Yan, Z.Y.; Shao, B.; Qin, L.; Xu, T.; Xue, Y.H.; et al. Chiral Os(II) polypyridyl complexes as enantioselective nuclear DNA imaging agents especially suitable for correlative high-resolution light and electron microscopy studies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 3465–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havranová-Vidláková, P.; Krömer, M.; Sýkorová, V.; Trefulka, M.; Fojta, M.; Havran, L.; Hocek, M. Vicinal diol-tethered nucleobases as targets for DNA redox labeling with osmate complexes. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Coverdale, J.P.C.; Guy, C.S.; Bridgewater, H.E.; Needham, R.J.; Fullam, E.; Sadler, P.J. Osmium-arene complexes with high potency towards Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Metallomics 2021, 13, mfab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, S.; Kar, R. Sandwich complexes of ruthenium, and osmium with group 13 analogues of N-heterocyclic carbene ligands: Efficient future complexes to reduce carbon monoxide poisoning. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2021, 1198, 113179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.K.; Shyam, A.; Mondal, P. A detailed quantum chemical investigation on the hydrolysis mechanism of osmium(III) anticancer drug, (ImH)[trans-OsCl4(DMSO)(Im)] (Os-NAMI-A; Im = imidazole). New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 5682–5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, R.J.; Sanchez-Cano, C.; Zhang, X.; Romero-Canelón, I.; Habtemariam, A.; Cooper, M.S.; Meszaros, L.; Clarkson, G.J.; Blower, P.J.; Sadler, P.J. In-cell activation of organo-osmium(II) anticancer complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 1017–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Tadeo, S.; Rodríguez-Fanjul, V.; Vequi-Suplicy, C.C.; Pizarro, A.M. Fast hydrolysis and strongly basic water adducts lead to potent Os(II) half-sandwich anticancer complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 18970–18978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Jena, N.R.; Shukla, P.K. A theoretical characterization of mechanisms of action of osmium(III)-based drug Os-KP418: Hydrolysis and its binding with guanine. Struct. Chem. 2023, 34, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dömötör, O.; Rathgeb, A.; Kuhn, P.S.; Popović-Bijelić, A.; Bačić, G.; Enyedy, E.A.; Arion, V.B. Investigation of the binding of cis/trans-[MCl4(1H-indazole)(NO)](-) (M = Ru, Os) complexes to human serum albumin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 159, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, G.; Wach, A.; Sá, J.; Szlachetko, J. Reduction mechanisms of anticancer osmium(VI) complexes revealed by atomic telemetry and theoretical calculations. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 6663–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ponte, F.; Borfecchia, E.; Martini, A.; Sanchez-Cano, C.; Sicilia, E.; Sadler, P.J. Glutathione activation of an organometallic half-sandwich anticancer drug candidate by ligand attack. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 14602–14605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Pan, C.; Huang, Y.; Huang, T.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, H.; Lau, T.; Man, W.; Ni, W. (Salen)osmium(VI) nitrides catalyzed glutathione depletion in chemotherapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Cano, C.; Romero-Canelón, I.; Geraki, K.; Sadler, P.J. Microfocus x-ray fluorescence mapping of tumour penetration by an organo-osmium anticancer complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 185, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coverdale, J.P.C.; Bridgewater, H.E.; Song, J.I.; Smith, N.A.; Barry, N.P.E.; Bagley, I.; Sadler, P.J.; Romero-Canelón, I. In vivo selectivity and localization of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induction by osmium anticancer complexes that circumvent platinum resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 9246–9255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.; Deepak, R.J.; Karvembu, R. Interweaving catalysis and cancer using Ru- and Os-arene complexes to alter cellular redox state: A structure-activity relationship (SAR) review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 491, 215230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.X.; Coppo, L.; Holmgren, A.; Kong, J.W.; Leong, W.K. Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase by triosmium carbonyl clusters. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 2441–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiddon, C.; Gross, I.; Meng, X.; Sidhoum, M.; Mellitzer, G.; Romain, B.; Delhorme, J.-B.; Venkatasamy, A.; Jung, A.C.; Pfeffer, M. Bypassing the resistance mechanisms of the tumor ecosystem by targeting the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway using ruthenium- and osmium-based organometallic compounds: An exciting long-term collaboration with Dr. Michel Pfeffer. Molecules 2021, 26, 5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allamyradov, Y.; ben Yosef, J.; Annamuradov, B.; Ateyeh, M.; Street, C.; Whipple, H.; Er, A.O. Photodynamic therapy review: Past, present, future, opportunities and challenges. Photochem 2024, 4, 434–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobłocki, K.; Drzeżdżon, J.; Kostrzewa, T.; Jacewicz, D. Coordination complexes as a new generation photosensitizer for photodynamic anticancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dominijanni, A.; Rodríguez-Corrales, J.Á.; Prussin, R.; Zhao, Z.; Li, T.; Robertson, J.L.; Brewer, K.J. Visible light-induced cytotoxicity of Ru, Os–polyazine complexes towards rat malignant glioma. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2017, 454, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Cui, K.; Si, S.; Liu, Y.; Xue, S.; Wang, G.; Liang, X.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Q.Y. Polypyridyl Os(II) complexes as efficient human non-small cell lung cancer photosensitizers with enhanced singlet oxygen generation via the fused π-ring elongation. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2025, 578, 122537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, F. Synthesis and spectroscopic study of a homogenous bimetallic Os(II) complex as a new gastric cancer photosensitizer. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, J.A., 3rd; Barrett, P.C.; Cole, H.D.; Lifshits, L.M.; Shi, G.; Monro, S.; von Dohlen, D.; Kim, S.; Russo, N.; Deep, G.; et al. Breaking the barrier: An osmium photosensitizer with unprecedented hypoxic phototoxicity for real world photodynamic therapy. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 9784–9806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, J.A., 3rd; Barrett, P.C.; Cole, H.D.; Lifshits, L.M.; Bradner, E.; Shi, G.; von Dohlen, D.; Kim, S.; Russo, N.; Deep, G.; et al. Os(II) oligothienyl complexes as a hypoxia-active photosensitizer class for photodynamic therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 16341–16360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, N.; Deng, Z.; Gao, J.; Liang, C.; Xia, H.; Zhang, P. An osmium-peroxo complex for photoactive therapy of hypoxic tumors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Cao, F.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Xia, H. Unlocking the potential of iridium-osmium carbolong conjugates: A high-performance photocatalyst for melanoma therapy. Sci. China Chem. 2025, 68, 3689–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Su, H.; Huang, X.; Dong, Q.; Chen, M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. A heteroleptic/trimetallic OsII-RuII-ZnII Sierpiński triangle for efficient photodynamic therapy of hypoxic tumors mainly through type I mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 23957–23971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Ding, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, X. Aggregation-induced photosensitization of long-chain-substituted Osmium complexes for lysosomes targeting photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 3464–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Qun, Z.; Xian-Li, M.; Ariffin, N.S. The potential of carbonic anhydrase enzymes as a novel target for anti-cancer treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 976, 176677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.C.; Chafe, S.C.; Supuran, C.T.; Dedhar, S. Cancer therapeutic targeting of hypoxia induced carbonic anhydrase IX: From bench to bedside. Cancers 2022, 14, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mesdom, P.; Purkait, K.; Saubaméa, B.; Burckel, P.; Arnoux, P.; Frochot, C.; Cariou, K.; Rossel, T.; Gasser, G. Ru(ii)/Os(ii)-based carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as photodynamic therapy photosensitizers for the treatment of hypoxic tumours. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 11749–11760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Chai, T.; Nguyen, W.; Liu, J.; Xiao, E.; Ran, X.; Ran, Y.; Du, D.; Chen, W.; Chen, X. Phototherapy in cancer treatment: Strategies and challenges. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Chen, X. Combined photodynamic and photothermal therapy and immunotherapy for cancer treatment: A review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 6427–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Wang, S.; Guo, Q.; Zhong, R.; Chen, X.; Xia, X. Anti-tumor strategies of photothermal therapy combined with other therapies using nanoplatforms. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Luo, X.; Zhao, C.; Hu, N.; Fang, J.; Zhang, E.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, B.; Li, Y.; et al. Design of dinuclear osmium complex doped antifouling cellulose nanoparticles for targeting and dual photodynamic/photothermal therapy under near infrared irradiation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.; Wu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhao, L.; Xu, F.; Hu, Y. Application of near-infrared dyes for tumor imaging, photothermal, and photodynamic therapies. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, K.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, R.; He, C.; Zhang, Q.; Chao, H. A NIR phosphorescent osmium(ii) complex as a lysosome tracking reagent and photodynamic therapeutic agent. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12341–12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erxleben, A. Mitochondria-targeting anticancer metal complexes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 694–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottani, E.; Brunetti, D. Advances in mitochondria-targeted drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Vidal, C.; Dey, S.; Zhang, L. Mitochondria targeting as an effective strategy for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olelewe, C.; Awuah, S.G. Mitochondria as a target of third row transition metal-based anticancer complexes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 72, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, C.; Zhu, J.; Ouyang, A.; Lu, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, P. Near-infrared phosphorescent terpyridine osmium(II) photosensitizer complexes for photodynamic and photooxidation therapy. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 4020–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Q. Near-infrared luminescent osmium(II) complexes with an intrinsic RNA-targeting capability for nucleolus imaging in living cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A.; Feng, T.; Gandioso, A.; Vinck, R.; Notaro, A.; Gourdon, L.; Burckel, P.; Saubaméa, B.; Blacque, O.; Cariou, K.; et al. Structurally simple osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes as photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy in the near infrared. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Dolan, C.; Moriarty, R.D.; Martin, A.; Neugebauer, U.; Forster, R.J.; Davies, A.; Volkov, Y.; Keyes, T.E. Osmium(II) polypyridyl polyarginine conjugate as a probe for live cell imaging; a comparison of uptake, localization and cytotoxicity with its ruthenium(ii) analogue. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 14323–14332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swavey, S.; Li, K. A dimetallic osmium(II) complex as a potential phototherapeutic agent: Binding and photocleavage studies with plasmid DNA. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 5551–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazic, S.; Kaspler, P.; Shi, G.; Monro, S.; Sainuddin, T.; Forward, S.; Kasimova, K.; Hennigar, R.; Mandel, A.; McFarland, S.; et al. Novel osmium-based coordination complexes as photosensitizers for panchromatic photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dröge, F.; Noakes, F.F.; Archer, S.A.; Sreedharan, S.; Raza, A.; Robertson, C.C.; MacNeil, S.; Haycock, J.W.; Carson, H.; Meijer, A.J.H.M.; et al. A dinuclear osmium(II) complex near-infrared nanoscopy probe for nuclear DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20442–20453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkika, K.S.; Byrne, A.; Keyes, T.E. Mitochondrial targeted osmium polypyridyl probe shows concentration dependent uptake, localisation and mechanism of cell death. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 17461–17471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkika, K.S.; Noorani, S.; Walsh, N.; Keyes, T.E. Os(II)-bridged polyarginine conjugates: The additive effects of peptides in promoting or preventing permeation in cells and multicellular tumor spheroids. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 8123–8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pursuwani, B.H.; Bhatt, B.S.; Vaidya, F.U.; Pathak, C.; Patel, M.N. Tetrazolo[1,5-a]quinoline moiety-based Os(IV) complexes: DNA binding/cleavage, bacteriostatic and photocytotoxicity assay. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 2894–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinck, R.; Karges, J.; Tharaud, M.; Cariou, K.; Gasser, G. Physical, spectroscopic, and biological properties of ruthenium and osmium photosensitizers bearing diversely substituted 4,4′-di(styryl)-2,2′-bipyridine ligands. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 14629–14639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.A.E.; Scattergood, P.A.; McKenzie, L.K.; Bryant, H.E.; Weinstein, J.A.; Elliott, P.I.P. Towards water soluble mitochondria-targeting theranostic osmium(II) triazole-based complexes. Molecules 2016, 21, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.A.E.; Scattergood, P.A.; McKenzie, L.K.; Jones, C.; Patmore, N.J.; Meijer, A.J.H.M.; Weinstein, J.A.; Rice, C.R.; Bryant, H.E.; Elliott, P.I.P. Photophysical and cellular imaging studies of brightly luminescent osmium(II) pyridyltriazole complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 13201–13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Camacho, R.; Roque-Ramires, M.A.; Ryabov, A.D.; Le Lagadec, R. Cyclometalated osmium compounds and beyond: Synthesis, properties, applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutillas, N.; Yellol, G.S.; de Haro, C.; Vicente, C.; Rodríguez, V.; Ruiz, J. Anticancer cyclometalated complexes of platinum group metals and gold. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2784–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, A.; Marková, L.; Santana, M.D.; Prachařová, J.; Bautista, D.; Kostrhunová, H.; Novohradský, V.; Brabec, V.; Ruiz, J.; Kašpárková, J. Cyclometalated benzimidazole osmium(II) complexes with antiproliferative activity in cancer cells disrupt calcium homeostasis. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 6474–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedulska, M.; Królicka, A.; Lipińska, A.D.; Krychowiak-Maśnicka, M.; Pierański, M.; Grabowska, K.; Nidzworski, D. Physicochemical profile of Os (III) complexes with pyrazine derivatives: From solution behavior to DNA binding studies and biological assay. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 316, 113804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, A.Z.; Cocic, D.C.; Bockfeld, D.; Zivanovic, M.; Milivojevic, N.; Virijevic, K.; Jankovic, N.; Scheurer, A.; Vranes, M.; Bogojeski, J.V. Biological activity of bis(pyrazolylpyridine) and terpiridine Os(II) complexes in the presence of biocompatible ionic liquids. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 2749–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchel, G.E.; Kossatz, S.; Sadique, A.; Rapta, P.; Zalibera, M.; Bucinsky, L.; Komorovsky, S.; Telser, J.; Eppinger, J.; Reiner, T.; et al. cis-Tetrachlorido-bis(indazole)osmium(iv) and its osmium(iii) analogues: Paving the way towards the cis-isomer of the ruthenium anticancer drugs KP1019 and/or NKP1339. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 11925–11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursuwani, B.H.; Bhatt, B.S.; Raval, D.B.; Thakkar, V.R.; Sharma, J.; Pathak, C.; Patel, M.N. Synthesis, characterization, and biological applications of pyrazole moiety bearing osmium(IV) complexes. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2021, 40, 593–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursuwani, B.H.; Bhatt, B.S.; Vaidya, F.U.; Pathak, C.; Patel, M.N. Fluorescence, DNA interaction and cytotoxicity studies of 4,5-dhydro-1H-pyrazol-1-Yl moiety based Os(IV) compounds: Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation. J. Fluoresc. 2021, 31, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W.; Tse, S.-Y.; Yeung, C.-F.; Chung, L.H.; Tse, M.K.; Yiu, S.-M.; Wong, C.-Y. Ru(II)- and Os(II)-induced cycloisomerization of phenol-tethered alkyne for functional chromene and chromone complexes. Organometallics 2020, 39, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitch, M.; Boota, R.Z.; Chalkley, A.S.; Keene, T.D.; Simpson, J.C.; Scattergood, P.A.; Elliott, P.I.P.; Quinn, S.J. Photophysical properties and DNA binding of two intercalating osmium polypyridyl complexes showing light-switch effects. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 14947–14961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanya, S.; Mondal, D.; Baitalik, S. Bimetallic Ru(II) and Os(II) complexes based on a pyrene-bisimidazole spacer: Synthesis, photophysics, electrochemistry and multisignalling DNA binding studies in the near infrared region. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 17010–17024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanya, S.; Karmakar, S.; Maity, D.; Baitalik, S. Ruthenium(II) and osmium(II) mixed chelates based on pyrenyl-pyridylimidazole and 2,2′-bipyridine ligands as efficient DNA intercalators and anion sensors. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eikey, R.A.; Abu-Omar, M.M. Nitrido and imido transition metal complexes of Groups 6–8. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 243, 83–124. [Google Scholar]

- Dehnicke, K.; Strähle, J. Nitrido complexes of transition metals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 955–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Grauwet, K.; Zhang, H.; Hussey, A.M.; Nowicki, M.O.; Wang, D.I.; Chiocca, E.A.; Lawler, S.E.; Lippard, S.J. Anticancer activity of osmium(VI) nitrido complexes in patient-derived glioblastoma initiating cells and in vivo mouse models. Cancer Lett. 2018, 416, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Q.; Wang, C.X.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.X.; Pan, C.; Chen, Y.Z.; Lian, X.; Man, W.L.; Ni, W.X. A cytotoxic nitrido-osmium(VI) complex induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in HepG2 cancer cells. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 17173–17182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, W.; Ji, P.; Song, F.; Liu, T.; Li, M.; Guo, H.; Huang, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, C.; et al. A pyrazolate osmium(VI) nitride exhibits anticancer activity through modulating protein homeostasis in HepG2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Lai, J.; Ma, L.; Chen, T. Substituent-regulated highly X-ray sensitive Os(VI) nitrido complex for low-toxicity radiotherapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, G.D.; Zhong, H.J.; Dong, Z.Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Kwong, D.W.; Ma, D.L.; Leung, C.H. Anticancer osmium complex inhibitors of the HIF-1α and p300 protein-protein interaction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.J.; Wang, W.; Kang, T.S.; Liang, J.X.; Liu, C.; Kwong, D.W.J.; Wong, V.K.W.; Ma, D.L.; Leung, C.H. Antagonizing STAT5B dimerization with an osmium complex. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Cryst. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.