Abstract

High-entropy coatings based on CoCrFeNiMn obtained by thermal spraying have demonstrated the potential to improve the wear resistance of traditional materials used in extreme conditions. The aim of the work was to study the effect of the oxygen/fuel ratio when using kerosene as fuel in the HVOF process on the microstructural characteristics of CoCrFeNiMn coatings, including phase composition, microhardness, elastic modulus, and wear resistance. Phase and microstructural transformations in gas-atomized powder during HVOF spraying were analyzed using XRD, SEM, and EDS methods. The tribological and mechanical properties of the coatings obtained were also evaluated. The results obtained are consistent with thermodynamic predictions based on the Scheil model for non-equilibrium conditions. The data obtained indicate the high potential of high-entropy CoCrFeNiMn alloys for use as protective coatings for industrial purposes. In addition, the results of the study emphasize the promise of using thermodynamic prediction of high-entropy alloys using Thermo-Calc software. The best mechanical and tribological properties were obtained in the HVOF 1 regime, which provided a maximum microhardness of 783.8 HV and a minimum wear rate of 7.45 × 10−5 mm3 × N−1 × m−1.

1. Introduction

The performance characteristics of materials in industry are largely determined by their surface properties. Modern surface modification technologies make it possible to economically improve the reliability of products by replacing or supplementing the base material with a coating with improved characteristics. Such coatings are particularly in demand in corrosive environments, conditions of increased wear, high temperatures, and heavy loads. However, increasing operational requirements and more complex working conditions have significantly increased the demand for advanced coatings with improved functional properties. In recent years, the concept of developing multicomponent alloys and coatings based on them has attracted considerable interest. There is particular interest in systems prone to the formation of ordered solid solutions, known as high-entropy alloys (HEA) [1]. These materials are considered promising solutions for use in extreme temperatures and loads, as they possess a range of unique performance characteristics, including high strength and impact toughness [2,3], resistance to oxidation and corrosion [4,5,6], increased wear resistance [7,8,9], and specific electrical and magnetic properties [10,11]. Consequently, HEA-based coatings have high potential for application in industrial and aerospace fields [12,13,14].

Among the various systems developed for wind turbines, particular attention is drawn to the CoCrFeNiMn alloy, also known as the Cantor alloy [15,16], which demonstrates high stability and hardness [17], exceptional fracture toughness [18], and a favorable combination of strength and ductility [19,20]. In addition, a number of studies [21,22,23] have shown that modifying the chemical composition of these alloys significantly affects their microstructure, phase composition, and mechanical characteristics.

Among the technologies for obtaining high-entropy coatings, thermal spraying (TS) methods occupy an important place as a universal and actively developing method. The metallurgical and materials science approach has highly evaluated the effectiveness of thermal spraying coating technologies. Wind turbine coatings obtained [7,24] by atmospheric plasma spraying show that the CoCrFeNiMn coating, consisting of a FCC phase and a significant amount of MnCr2O4 oxides, forms a protective tribological layer on the surface, ensuring high wear resistance under various conditions. Liao et al. [12] used detonation spraying to obtain a CoCrFeNiMn-based coating, which is characterized by a dense FCC structure with nanoparticles of multicomponent oxides and has a significantly higher microhardness and excellent abrasive wear resistance compared to coatings obtained by direct casting or SPS. A Patel et al. [25,26] used fuel/oxygen ratio control in the HVOF spraying process, which allowed them to form coatings with reduced porosity and oxidation when using propylene as fuel. The results obtained by HVOF methods show that CoCrFeNiMn-based coatings range from 400 to 490 HV.

Of the listed thermal spray methods, high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) spraying attracts considerable attention due to its ability to form dense, low-porosity coatings with high adhesion and mechanical properties [27,28,29]. High particle velocities and intensive cooling ensure the formation of a fine-grained microstructure, which contributes to increased strength, corrosion resistance, and wear resistance of coatings. Due to its high productivity, cost-effectiveness, and low level of by-products, the HVOF process is widely used to protect components operating in aggressive environments, including oxidation, hot corrosion, and intense friction [25,30]. Despite the existence of studies on the use of this method for obtaining HVOF coatings, the use of kerosene as a fuel remains insufficiently studied. This is one of the reasons for the need to study the effect of changing the oxygen/fuel ratio of HVOF parameters to obtain coatings with predictable and improved functional properties.

It should also be noted that the HVOF spraying process is characterized by high cooling rates typical of thermal spraying processes. This allows us to use specialized phase formation modeling methods. One of these is the modified CALPHAD approach—the Scheil simulation, based on the Scheil–Gulliver equation and assuming no diffusion in the solid phase—which allows for more realistic prediction of phase evolution during rapid solidification [31]. A number of studies have confirmed the applicability of this approach for AlCoCrFeNi HEA during HVOF and HVAF spraying [32,33]. However, the application of Scheil simulation for CoCrFeNiMn HEA remains insufficiently studied.

The aim of this study is to determine the influence of the O/F ratio when using kerosene as fuel in the HVOF process on the microstructural characteristics of CoCrFeNiMn coatings, including phase composition, microhardness, elastic modulus, and wear resistance. In addition, the paper evaluates the applicability of classical Scheil simulation as a tool for predicting phases in HVOF-applied CoCrFeNiMn HEA coatings. The phase formations and their compositions predicted by Scheil simulation were compared and confirmed by experimental data obtained for HVOF-applied HEA coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of CoCrFeNiMn HEA Coatings

CoCrFeNiMn powder obtained by gas atomization was used as the starting material. For the experiments, fractions with a size of 32–45 μm were selected using sieves on an AS 200 basic (Retsch, Haan, Germany) sieving machine; the starting powder had good flowability.

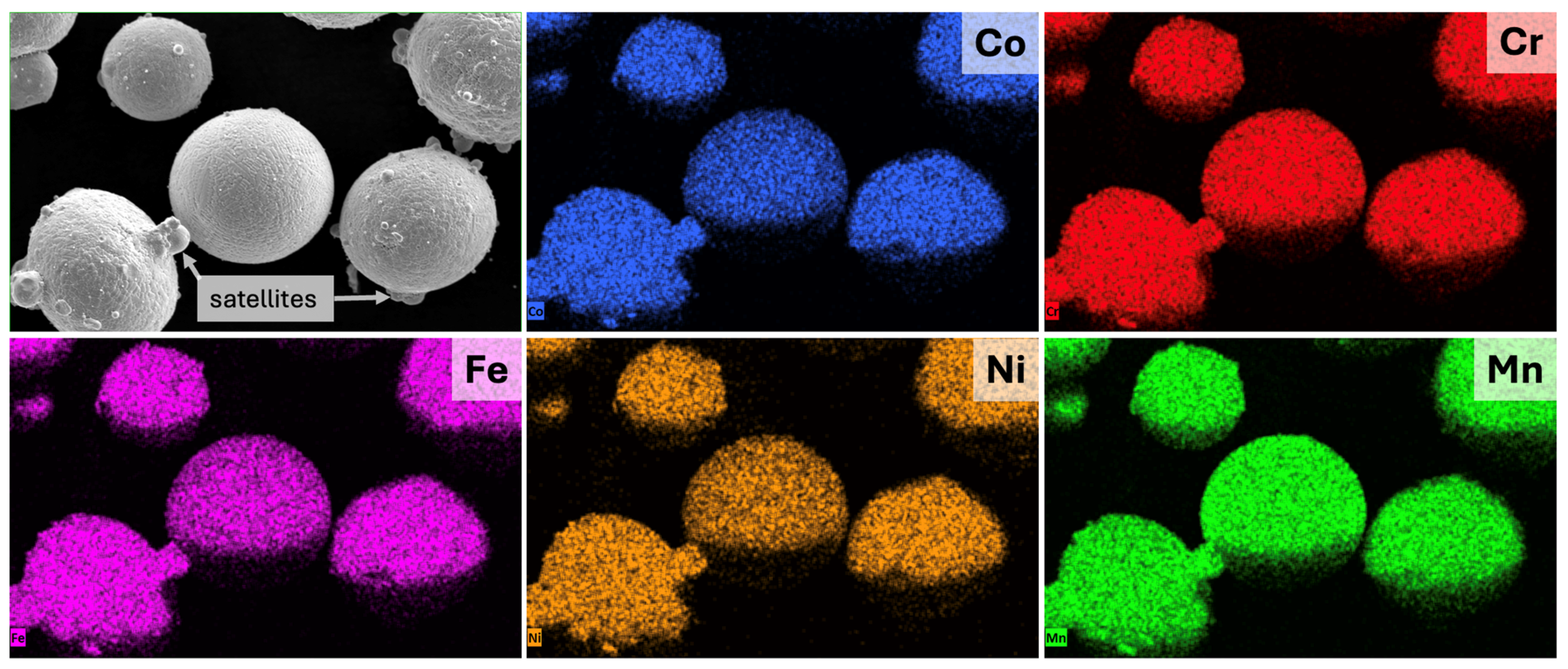

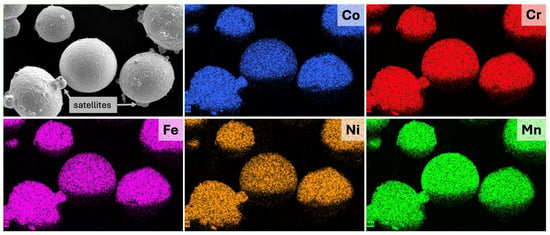

Morphological analysis of gas-atomized CoCrFeNiMn, shown in Figure 1, revealed that most powder particles are nearly spherical in shape. In addition, several satellites attached to large spherical particles were also observed. The chemical composition of the powder (Table 1), measured by EDX, is close to the nominal equiatomic composition of the CoCrFeMnNi system. Elemental mapping shown in Table 1 (EDS) indicates a uniform distribution of the main elements throughout the particle volume without significant segregation.

Figure 1.

Microstructure and elemental distribution of CoCrFeNiMn powder.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (EDX) for powder CoCrFeNiMn.

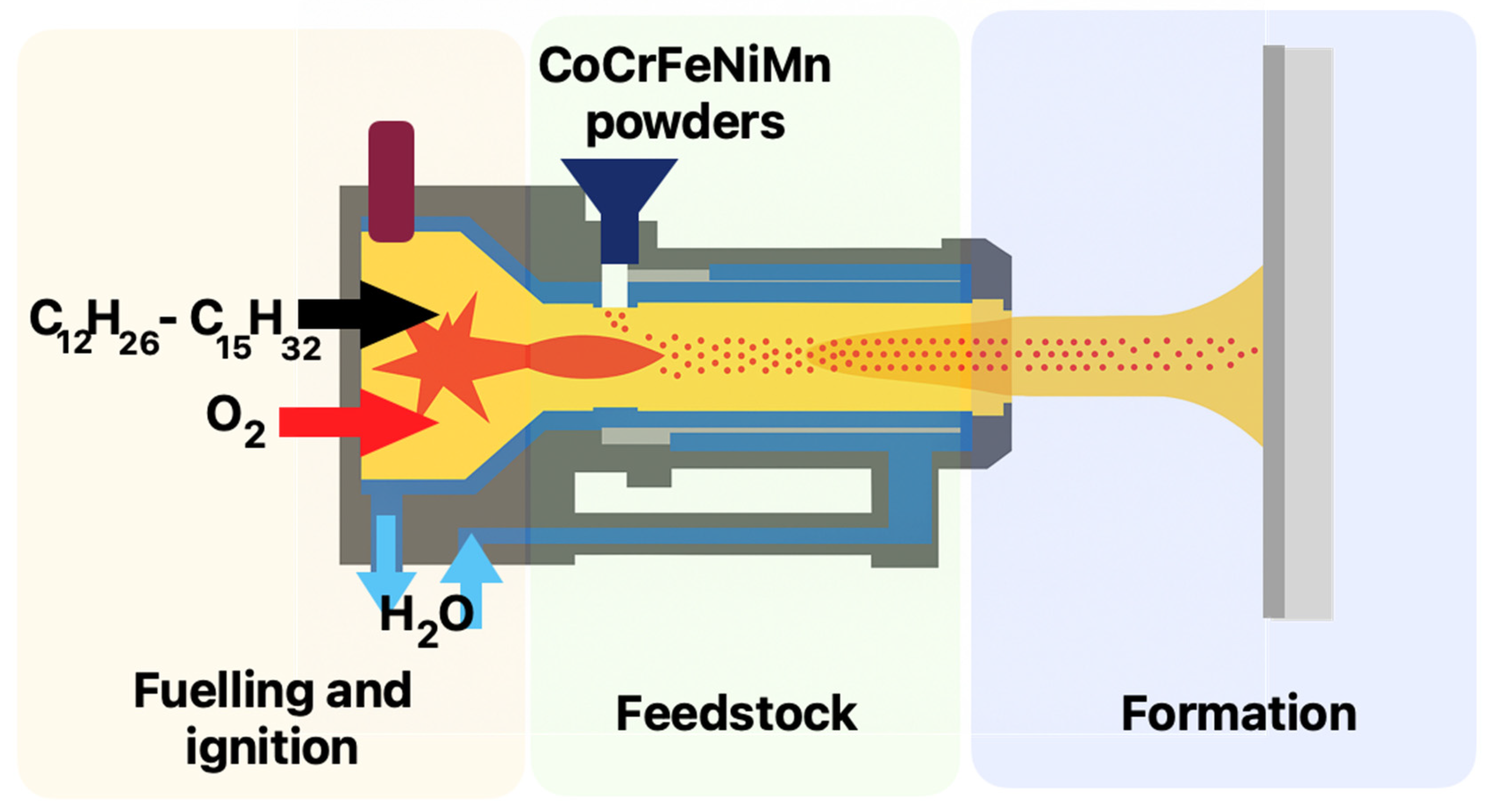

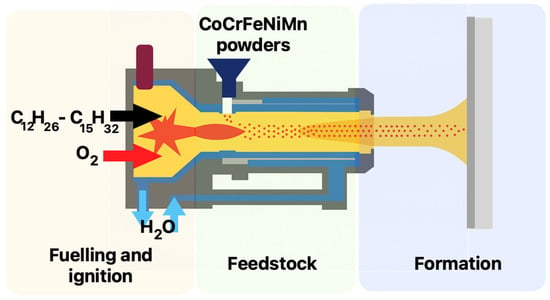

Rectangular plates with a thickness of 3 mm and dimensions of 25 × 45 mm made of stainless steel (SS316L) were used as substrates. Before spraying, all substrates were sandblasted to obtain a rough surface and then ultrasonically cleaned in a bath using 97% isopropyl alcohol to remove residual particles on the substrate surface. High-entropy coatings (HEC) of CoCrFeNiMn were obtained by HVOF at various conditions. A JP 5000 gun (Praxair TAFA, Danbury, CT, USA) was used for high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) spraying. A schematic diagram and parameters of the process of obtaining CoCrFeNiMn HEC by the HVOF method are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of CoCrFeNiMn HEC prepared by HVOF.

Table 2.

Parameters of HVOF regimes for CoCrFeNiMn HEC.

2.2. Thermo-Calc Predictions

Thermodynamic calculations were performed using Thermo-Calc software based on CALPHAD (version 2025a, Thermo-Calc Software, Stockholm, Sweden) [34], integrated with a database of high-entropy alloys (TCHEA7.0). To understand the stability and distribution of phases, a non-equilibrium diagram was constructed using the Scheil–Gulliver model [35] to simulate the rapid cooling rates characteristic of gas thermal spraying methods, and a prediction of the equilibrium phase of CoCrFeNiMn as a function of temperature was made. This model assumes that there is no diffusion in the solid state, while in the liquid state, diffusion is infinitely fast [35]. The CALPHAD predictions were then compared with the experimental results obtained for the CoCrFeNiMn HVOF coatings.

2.3. Microstructure and Chemical Analysis

The phase composition of the powders and the coatings obtained under various HVOF conditions was investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using an X’PertPRO (PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154056 nm). The measurement was performed in the range of 20–90° at a scanning speed of 0.02°/s. The results obtained were further analyzed using HighScore Plus v.5.2.0 software (XRD analysis software, USA) to determine the crystal lattice parameters.

Microstructural analysis of the CoCrFeNiMn HEC cross-sections was performed using a SEM3200 scanning electron microscope (CIQTEK, Hefei, China) with autoemission at an accelerating voltage of 15 keV and a working distance of 10 mm. Chemical composition analysis was performed using an XFlash 730M-300 energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) (Bruker, Hamburg, Germany).

2.4. Mechanical Properties

The microhardness and elastic modulus measurements of the polished cross-sections of CoCrFeNiMn HEC were performed on a Fisherscope HM2000 universal microdynamic microhardness tester (Helmut Fischer GmbH, Sindelfingen, Germany) at a load of 1000 mN and an exposure time of 10 s, in accordance with ASTM E2546. The tests were performed using a Vickers diamond indenter. To determine the elastic modulus (E), the device uses the depth-sensing indentation (DSI) method. During the measurement, the depth of indentation is recorded as a function of the applied load during loading and unloading. The indentation points were arranged in a 3 × 3 matrix with a 50 μm pitch between adjacent measurements.

The wear resistance of CoCrFeNiMn HEC obtained by gas thermal spraying methods under dry sliding conditions was evaluated using a ball-on-disk tribometer TRB3 (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) at room temperature, in accordance with ASTM G99. Balls made of 100Cr6 bearing steel with a 6 mm diameter and a hardness of 743 ± 12 HV were used as the counterbodies. The radius of the friction track was 5 mm. The normal load applied to the sample was constant and equal to 10 N. The tests were stopped after reaching a total friction path of 500 m. All experiments were performed under the same conditions, which ensured the reproducibility of the results obtained. The loss of coating material volume was determined by scanning with a Surtronic S-100 profilometer (Taylor Hobson, Leicester, UK).

3. Results and Discussion

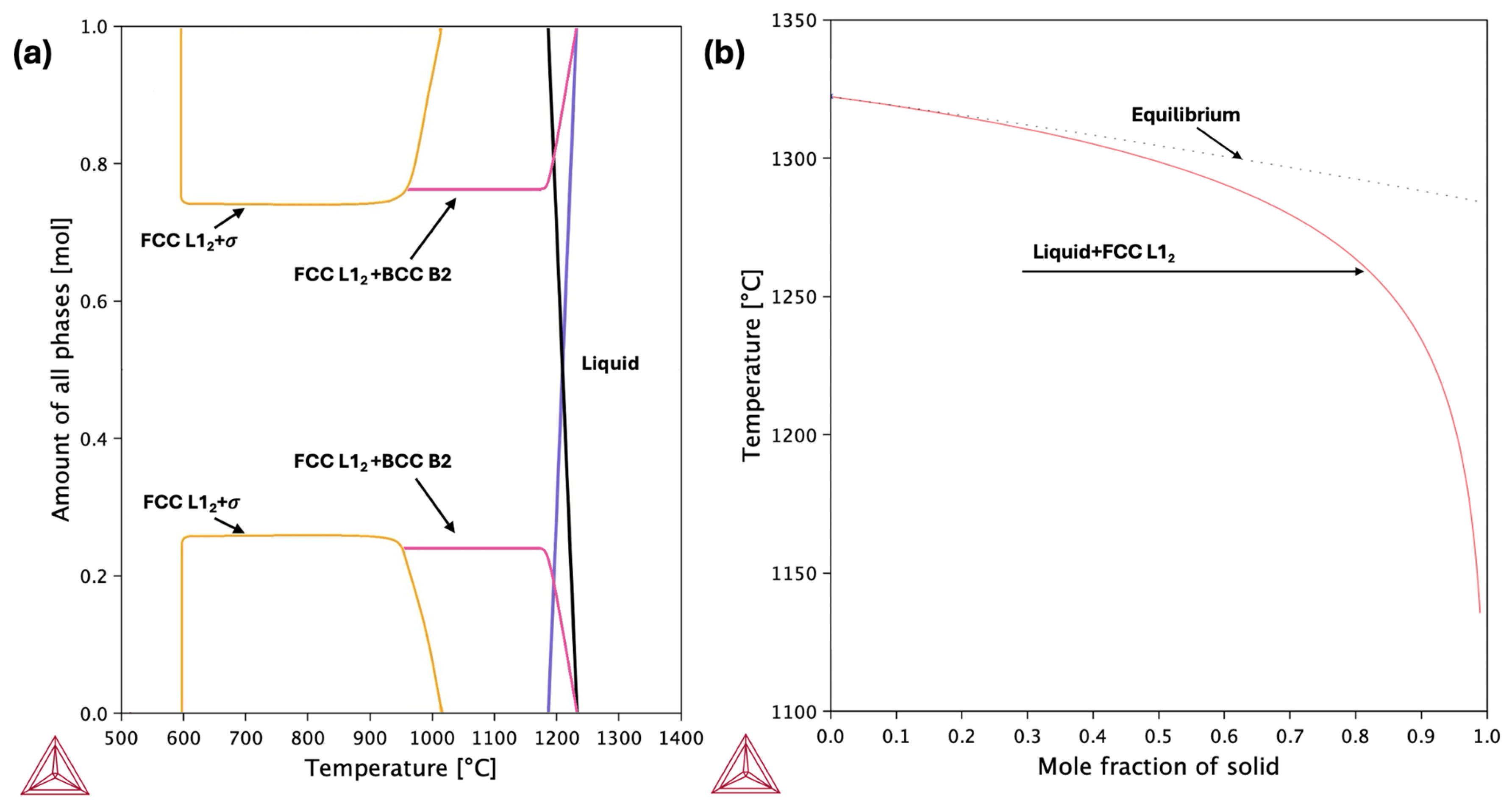

3.1. Thermo-Calc Phase Projections

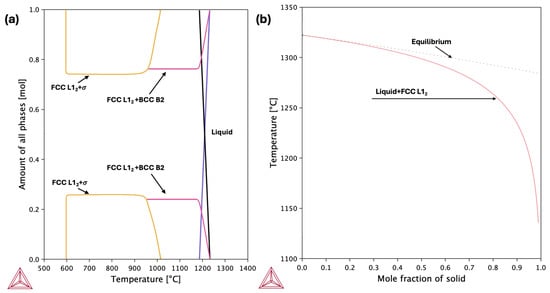

The equilibrium phase diagram for the CoCrFeNiMn alloy is shown in Figure 3a, and the Scheil–Gulliver model diagram for analyzing alloy solidification processes is shown in Figure 3b. Figure 3a shows that the main phase is the disordered FCC_L12 phase, which dominates over a wide temperature range. The FCC_L12 phase coexists with the SIGMA phase in the range of approximately 726 °C to 986 °C and with the BCC_B2 phase in the range of 1060 °C to 1073 °C. Scheil’s model for the CoCrFeNiMn alloy (Figure 3b) shows that unlike the equilibrium phase diagram where the SIGMA and BCC_B2 phases are present, under non-equilibrium conditions the only phase that forms is the FCC_L12 phase. Thus, the Scheil–Gulliver model calculation indicates that the CoCrFeNiMn alloy is prone to non-equilibrium crystallization with the formation of a single-phase microstructure. The results obtained are consistent with the phase composition results of [25].

Figure 3.

Simulations of (a) the equilibrium phase and (b) the Scheil phase diagram for CoCrFeNiMn HEC obtained using Thermo-Calc software.

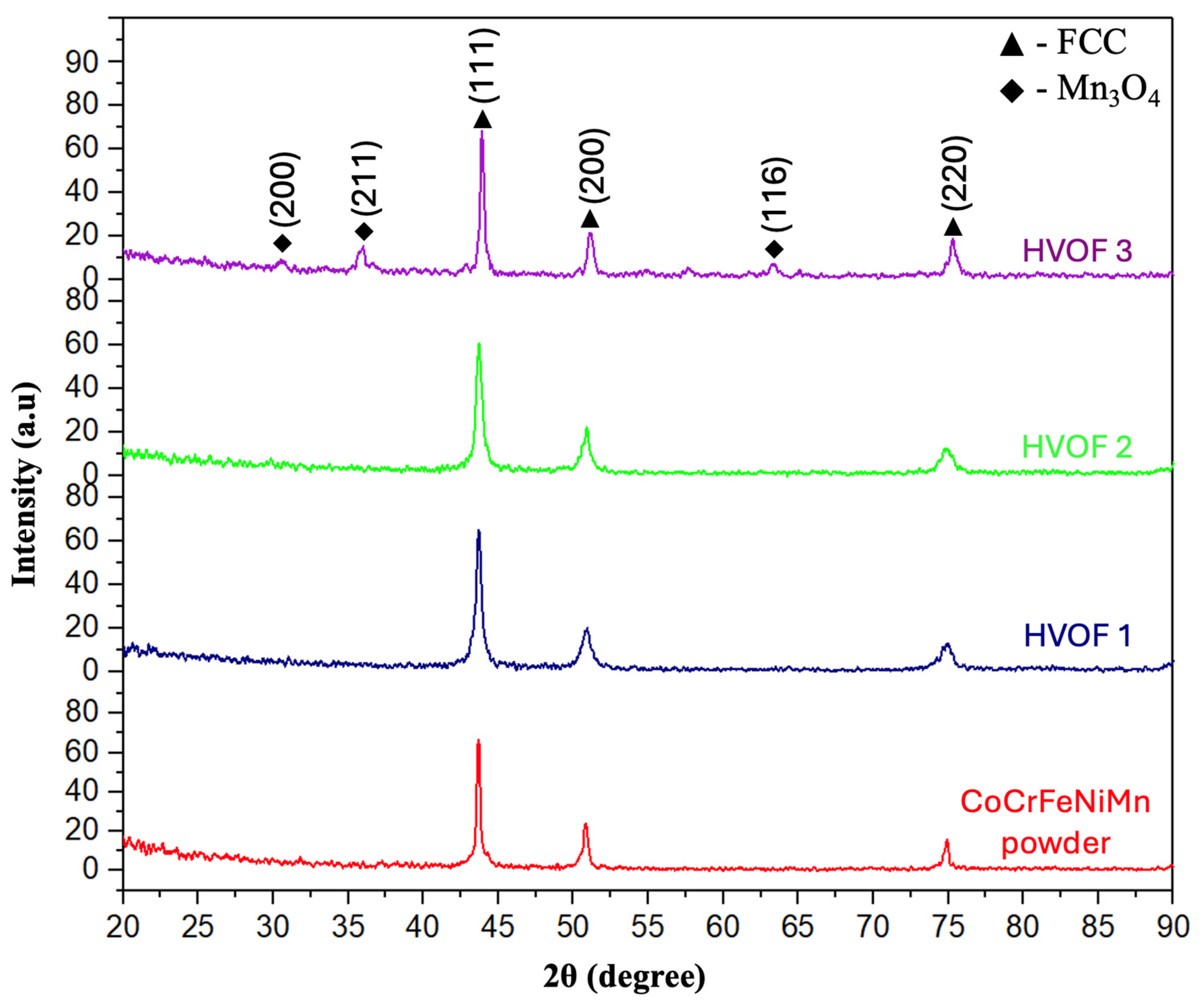

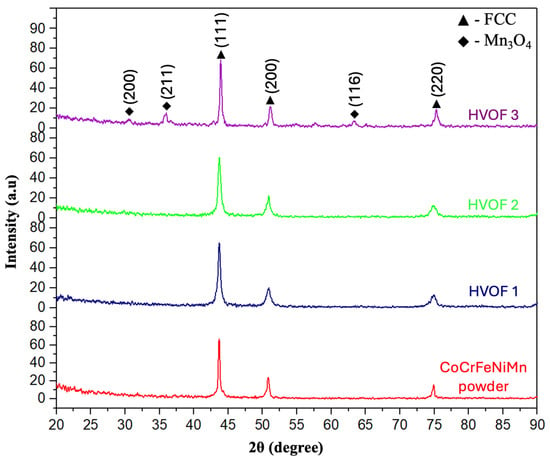

X-ray diffraction patterns of the CoCrFeNiMn powder and HVOF coatings obtained under various conditions are shown in Figure 4. The starting powder is characterized by a single-phase structure with a face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice, which corresponds to the typical phase stability of the equiatomic CoCrFeNiMn alloy system.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the CoCrFeNiMn HEA powders and the coatings.

After applying coatings using the HVOF method in all the regimes studied, the phase with a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal lattice dominates, which indicates high phase stability of the main phase during the gas thermal spraying process. This indicates the absence of significant structural transformations during spraying and the preservation of the original crystal structure of the alloy.

For the HVOF 3 regime, additional peaks corresponding to manganese oxide Mn3O4 are observed in the diffraction patterns, indicating an intensification of oxidation processes. The formation of this phase is probably due to the increased flame temperature and particle velocity, which promote the oxidation of manganese during the spraying process.

Diffraction maxima located near 2θ ≈ 43.95°, 51.12°, and 75.34° were indexed as reflections from the crystallographic planes (111), (200), and (220) of the FCC structure, respectively. Additional peaks at 2θ ≈ 30.65°, 35.93°, and 63.36° are attributed to the (200), (211), and (116) planes of the Mn3O4 phase in accordance with reference PDF No. 01-089-4837.

Thus, the XRD results demonstrate that under HVOF 1 and HVOF 2 regimes, the coating structure is practically identical to the initial powder and is represented by single-phase FCC, while with an increase in process energy, the system’s tendency toward partial oxidation with Mn3O4 release increases. The quantitative phase composition of the CoCrFeNiMn gas-atomized powder and the HVOF coatings obtained, determined by Rietveld analysis, is presented in Table 3. The results obtained indicate the absence of significant structural transformations during spraying and the preservation of the original crystalline structure of the alloy. The presence of oxide inclusions can have a dual effect on the operational properties of coatings: on the one hand, they can contribute to strengthening, and on the other hand, they can lead to brittleness. Consequently, optimization of HVOF spraying regimes is a key factor in obtaining CoCrFeNiMn coatings with a favorable combination of structure and performance characteristics. The X-ray diffraction pattern of the coating (Figure 4) is consistent with the results of modeling according to the Scheil diagram shown in Figure 3b.

Table 3.

Phase composition of gas-atomized CoCrFeNiMn powder and HVOF coatings, determined by Rietveld quantitative analysis.

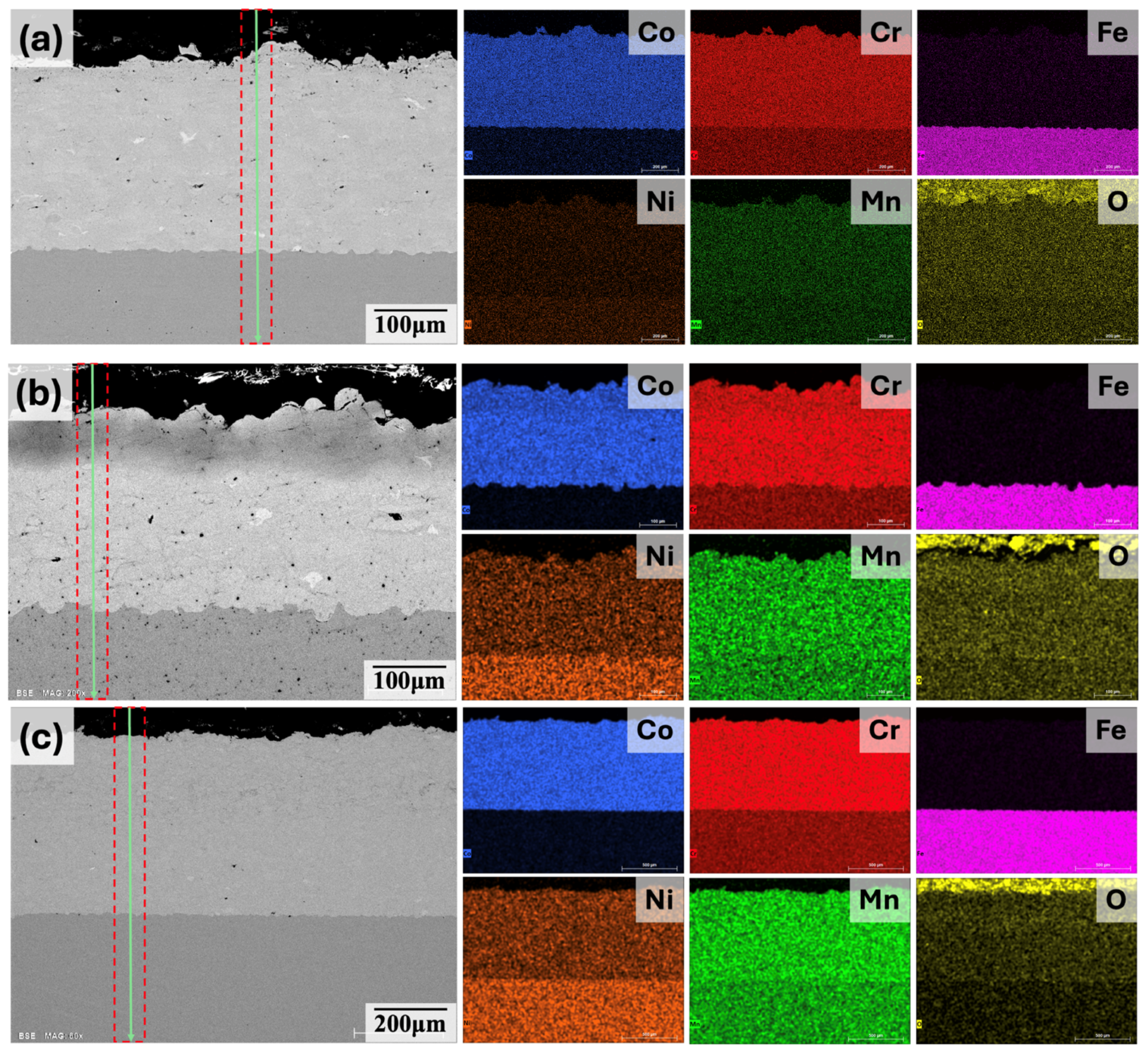

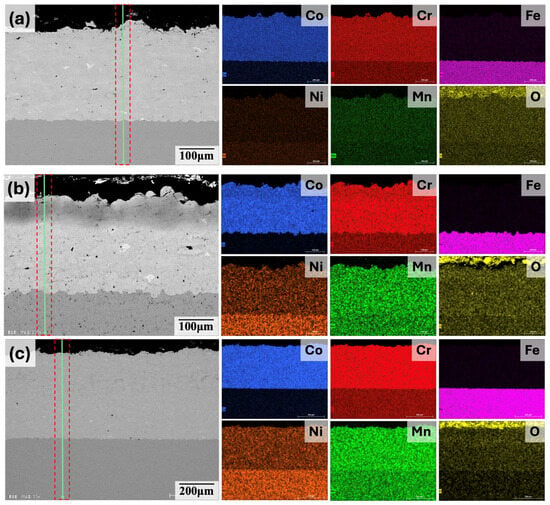

The results of BSE-SEM cross-section analysis of samples shown in Figure 5 indicate that all coatings obtained by the HVOF method demonstrate good adhesion to the stainless steel substrate (SS316L), with an average coating thickness of 263.89 μm for the HVOF 1 regime, 251.63 μm for the HVOF 2 regime, and 521.13 μm for the HVOF 3 regime. No significant cracks, pores, or other defects are observed at the boundary between the coating and the substrate. EDS analysis shows that all elements are distributed uniformly throughout the coating thickness, with no accumulation of individual elements. This uniformity indicates effective flattening and mixing of particles upon impact, as well as rapid solidification, which suppresses long-range diffusion during deposition. It is important to note that no continuous oxide films are observed between the plates. The results of analysis using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), presented in Table 4, demonstrate the distribution of the atomic concentrations of the main elements in the coatings obtained under various HVOF regimes. For each regime, both the values obtained from the distribution maps (map) and from the linear scanning of the cross-section (line) are given. This is consistent with the inherently low degree of oxidation inherent in the HVOF process, where particles travel in a relatively cold flame at high velocities, limiting their exposure to oxidative conditions.

Figure 5.

SEM images and EDS mapping of the cross-section of the CoCrFeNiMn HECs (a) HVOF 1 (b) HVOF 2 (c) HVOF 3.

Table 4.

The quantitative elemental composition obtained by EDS corresponds to the elemental maps and line (green line shown inside red dashed rectangle) profiles presented in Figure 5.

3.2. Mechanical Properties and Wear Resistance

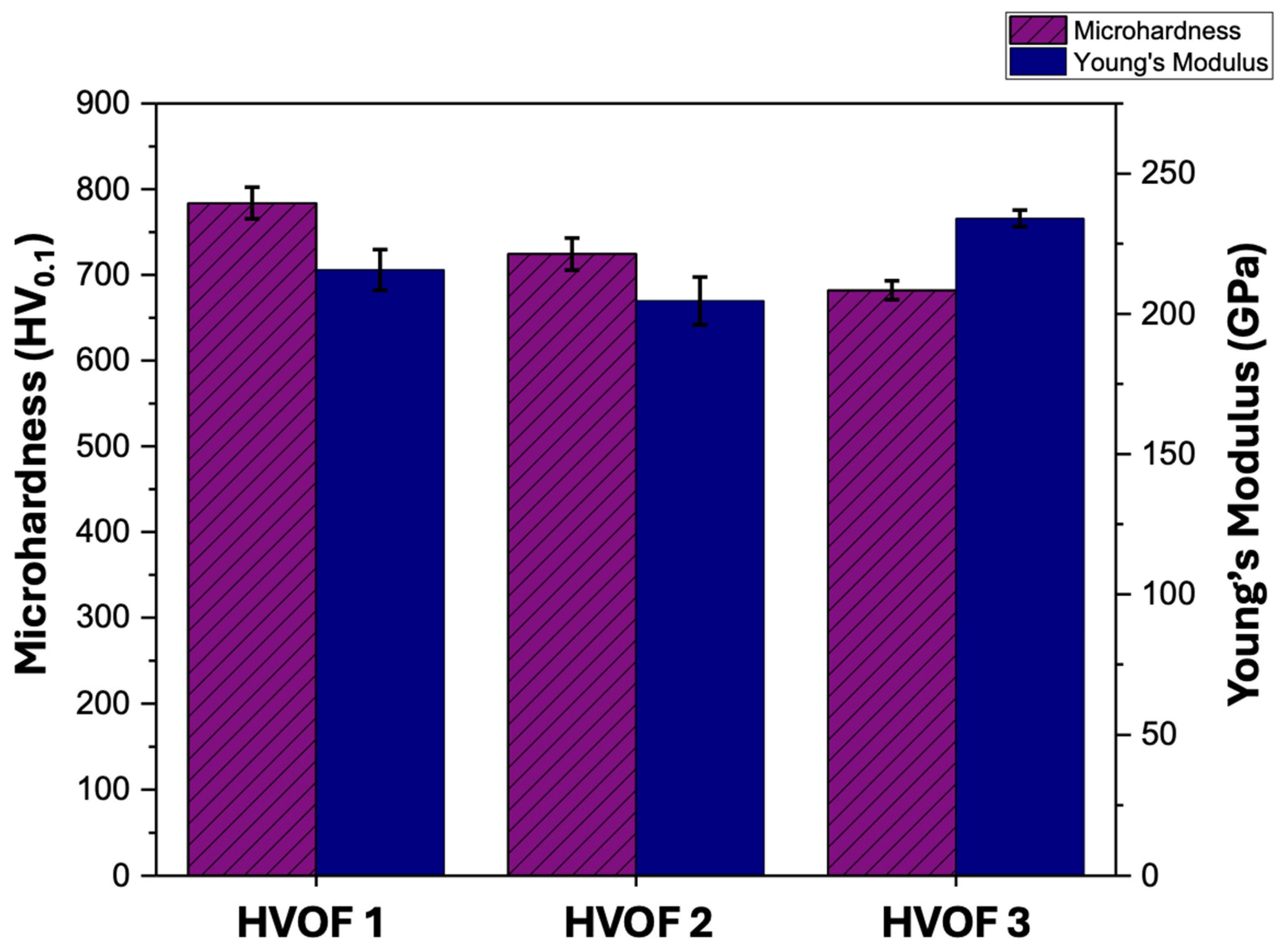

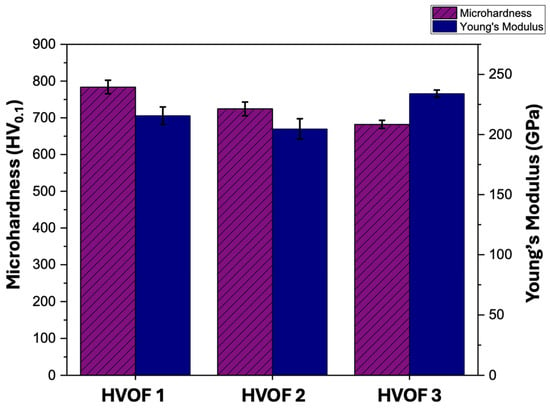

The microhardness and elastic modulus of HVOF-sprayed coatings obtained by three HVOF spraying regimes are shown in Figure 6. The coatings demonstrate high hardness values typical for dense layers of high-entropy alloys with limited porosity and strong interlamellar adhesion. The highest microhardness was recorded for the HVOF 1 regime, reaching 783.8 ± 18.5 HV0.1, while the HVOF 2 and HVOF 3 regimes showed slightly lower values of 724.3 ± 18.7 HV0.1 and 682.0 ± 11.1 HV0.1, respectively.

Figure 6.

Average microhardness and Young’s modulus of CoCrFeNiMn coatings.

The reduced elastic modulus follows a slightly different trend. HVOF 1 shows a value of 215.7 ± 7.2 GPa, HVOF 2 shows the lowest modulus of 204.6 ± 8.6 GPa, while HVOF 3 shows the highest value of 234.0 ± 2.9 GPa. This inverse relationship between hardness and modulus indicates that HVOF 3 coatings, despite their lower hardness, have a more rigid lamellar structure, possibly due to the proportion of oxides in the distribution.

The presence of the fragile Mn3O4 oxide phase has a pronounced effect on the mechanical response of the coating. In particular, an increase in the elastic modulus is observed. The elastic modulus is a structure-sensitive parameter determined by the rigidity of interatomic bonds, with oxide phases characterized by higher modulus values compared to the metal matrix. Their presence in the form of dispersed inclusions or at the boundaries of splats leads to an increase in the overall elastic modulus of the HEC.

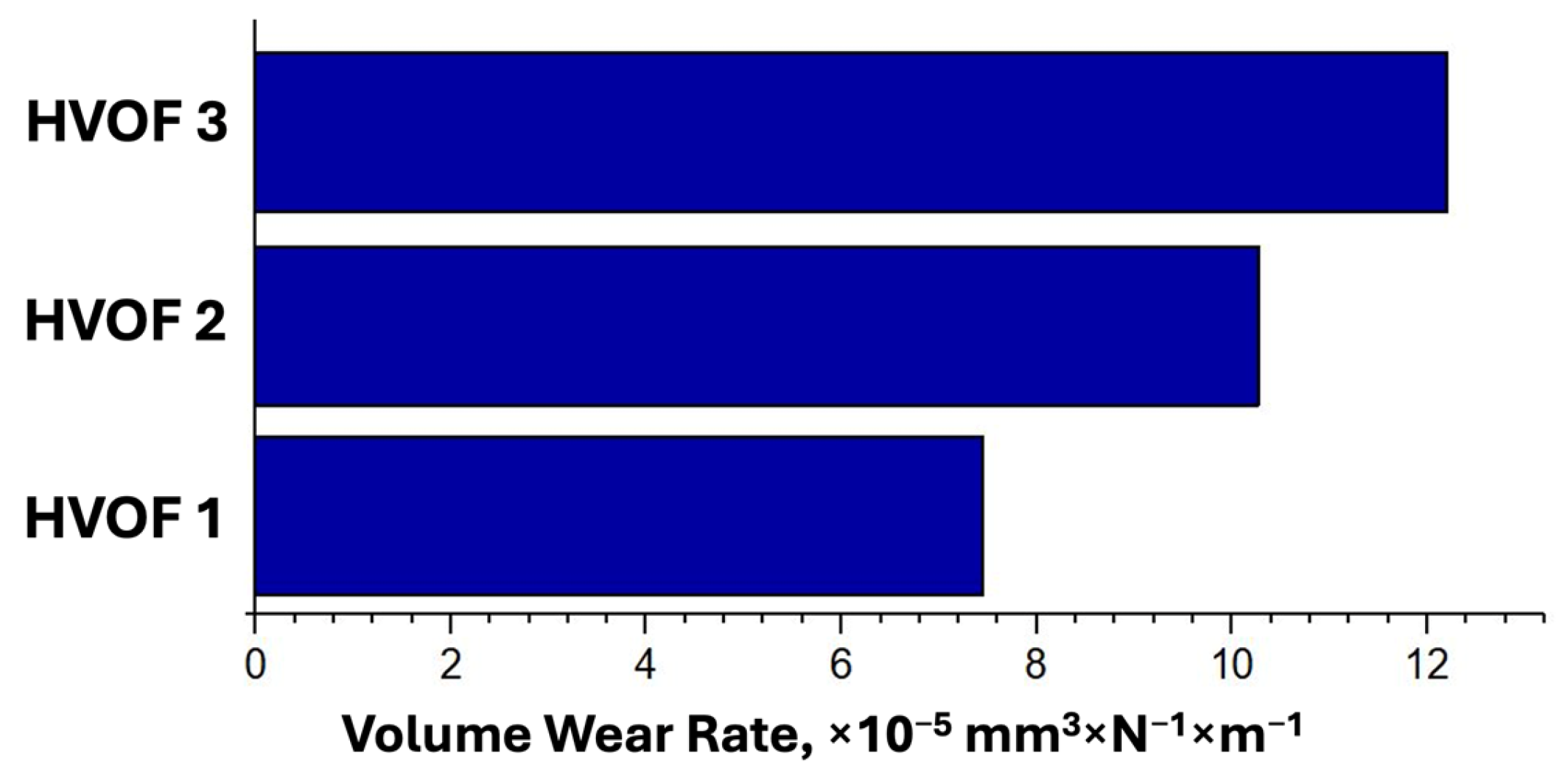

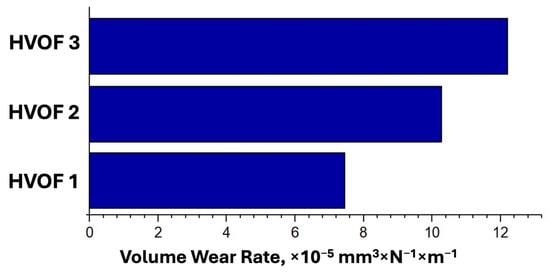

The volume wear rate values for the HVOF spraying regimes (HVOF 1, HVOF 2, and HVOF 3) are shown in Figure 7. The data obtained clearly demonstrate that the wear resistance of coatings largely depends on the spraying parameters, which determine the degree of particle heating, their adhesion, and the microstructure formed. The lowest wear rate is demonstrated by the HVOF 1 coating, for which a value of 7.45 × 10−5 mm3 × N−1 × m−1 was obtained. This result is consistent with the microhardness measurement data (see Table 2), where the HVOF 1 coating also showed one of the highest values, and confirms the classic correlation between hardness and abrasive wear resistance for dense metal coatings. The wear rate of the HVOF 2 and HVOF 3 coatings was higher, at 10.27 × 10−5 mm3 × N−1 × m−1 and 12.20 × 10−5 mm3 × N−1 × m−1, respectively.

Figure 7.

Volume wear rate of CoCrFeNiMn HEC.

The results clearly demonstrate that the wear resistance of coatings strongly depends on the spraying parameters, which affect particle heating, particle adhesion, and the microstructure formed. The HVOF 1 regime provides the lowest wear rate, which is consistent with the microhardness measurement results.

4. Conclusions

CoCrFeNiMn alloy coatings were successfully applied using three HVOF regimes to an SS 316L substrate and their microstructure, phase composition, and mechanical and tribological properties were studied. It was shown that the selected spraying parameters significantly affect the structure and performance characteristics of the coatings. The main conclusions are as follows:

The coatings of all three regimes are characterized by a dense lamellar structure and uniform distribution of elements, and the rapid cooling rate in HVOF leads to the formation of a supersaturated solid solution of the FCC phase in the melt solidification zone. Thermo-Calc simulations under non-equilibrium cooling conditions using the Scheil model predicted the formation of FCC phases during rapid cooling, which coincides with the experimental XRD data.

The microhardness and wear resistance of the coating under the HVOF 1 regime showed the highest hardness of 783.8 ± 18.5 HV0.1 and the lowest wear rate of 7.45 × 10−5 mm3 × N−1 × m−1. Meanwhile, regimes HVOF 2 and HVOF 3 show lower hardnesses and increased wear rates, which is associated with a lower degree of particle melting and a reduced density of interlamellar bonds. The observed changes in different regimes highlight the sensitivity of mechanical properties to particle temperature, oxidation level, and crystallization dynamics during spraying.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and Z.S.; methodology, L.S.; investigation, A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and P.K.; writing—review and editing, Z.S.; project administration, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP22787411).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, M.T.; Pantawane, M.V.; Joshi, S.; Gantz, F.; Ley, N.A.; Mayer, R.; Spires, A.; Young, M.L.; Dahotre, N. Laser-coated CoFeNiCrAlTi high entropy alloy onto a H13 steel die head. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 387, 125473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A.S.M.; Berndt, C.C.; Sesso, M.L.; Anupam, A.; Kottada, R.S.; Murty, B.S. Plasma-sprayed high entropy alloys: Microstructure and properties of AlCoCrFeNi and MnCoCrFeNi. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Z.S.; Lei, Y.N.; Zhu, J.C. Wear and oxidation resistances of AlCrFeNiTi-based high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2018, 101, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Yu, Y.; Xiong, N.; Liu, M.; Qiao, Z.; Yi, G.; Yao, Q.; Zhao, G.; Xie, E.; Wang, Q. Microstructure and tribological behavior of a novel atmospheric plasma sprayed AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy matrix self-lubricating composite coatings. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Tang, L. Design and evaluation method of erosion-resistant and wear-resistant CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy coating based on molecular dynamics simulation and machine learning. Corros. Sci. 2025, 254, 113048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.K.; Tan, H.; Wu, Y.Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C. Microstructure and wear behavior of FeCoNiCrMn high entropy alloy coating deposited by plasma spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 385, 125430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, K.; Zhao, G.-L.; Guo, S.M. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of high entropy AlCoCrFeNi alloy powder laden composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 734, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, P.; Li, D.; Hao, J.; Yang, H.; Yu, G. Hierarchical heterogeneous microstructure for enhanced wear resistance of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy coatings via in-situ rolling assisted laser cladding. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 141, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, S.; Öztürk, B.; Alptekin, F.; Sünbül, S.E.; Öztürk, S.; İçin, K. The role of mechanical alloying on the phase structure and magnetic properties of Ni-doped CoFeAlMn high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1041, 183597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, H. Electromagnetic wave absorption properties of mechanically alloyed FeCoNiCrAl high entropy alloy powders. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 1128–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.B.; Wu, Z.X.; Lu, W.; He, M.; Wang, T.; Guo, Z.; Huang, J. Microstructures and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy coatings by detonation spraying. Intermetallics 2021, 132, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bobzin, K.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, L.; Öte, M.; Königstein, T.; Tan, Z.; He, D. Wear behavior of HVOF-sprayed Al0.6TiCrFeCoNi high entropy alloy coatings at different temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 358, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Yan, C.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, D. Microstructure and tribological properties of plasma-sprayed Al0.2Co1.5CrFeNi1.5Ti–Ag composite coating from 25 to 750 °C. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 1640–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. Multicomponent high-entropy Cantor alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 120, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. The thermodynamics of multicomponent high-entropy materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 1750–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, B.; Mendez-Martin, F.; Völker, B.; George, E.P.; Clemens, H.; Pippan, R.; Hohenwarter, A. Mechanical properties, microstructure and thermal stability of a nanocrystalline CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 2015, 96, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mao, M.M.; Wang, J.; Gludovatz, B.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, S.X.; George, E.P.; Yu, Q.; Ritchie, R.O. Nanoscale origins of the damage tolerance of the high-entropy alloy CrMnFeCoNi. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.E.; Kim, Y.K.; Yoon, S.H.; Lee, K.A. Tuning the microstructure and mechanical properties of cold sprayed equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy coating layer. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 2406–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.G.; Nguyen, Q.B.; Ng, F.L.; An, X.H.; Liao, X.Z.; Liaw, P.K.; Nai, S.M.L.; Wei, J. Hierarchical microstructure and strengthening mechanisms of a CoCrFeNiMn high entropy alloy additively manufactured by selective laser melting. Scr. Mater. 2018, 154, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, M.E.; Christofidou, K.A.; Monni, F.; Yang, Q.; Hang, M.; Jones, N.G. The influence of Fe variations on the phase stability of CrMnFexCoNi alloys following long-duration exposures at intermediate temperatures. Intermetallics 2021, 131, 107108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofidou, K.A.; Pickering, E.J.; Orsatti, P.; Mignanelli, P.M.; Slater, T.J.A.; Stone, H.J.; Jones, N.G. On the influence of Mn on the phase stability of the CrMnxFeCoNi high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2018, 92, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviot, A.; Sallamand, P.; Cazottes, S.; Danlos, Y.; Herbst, F.; de Lucas, M.D.C.M.; Le Gallet, S. Influence of the starting powder and ball milling on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al0.3CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy, obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 50, 114500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambarov, Y.Y. Effect of spraying regime and vacuum annealing on the microstructure and wear resistance of plasma-sprayed CoCrFeNiMn high entropy coatings. Vestn. Univ. Shakarima Seriya Tekhnicheskie Nauki 2025, 3, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Munagala, V.N.V.; Sharifi, N.; Roy, A.; Alidokht, S.A.; Harfouche, M.; Moreau, C. Influence of HVOF spraying parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of FeCrMnCoNi high-entropy coatings. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 4293–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Alidokht, S.A.; Sharifi, N.; Roy, A.; Harrington, K.; Stoyanov, P.; Moreau, C. Microstructural and tribological behavior of thermal spray CrMnFeCoNi high entropy alloy coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2022, 31, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Luna, H.; Lozano-Mandujano, D.; Alvarado-Orozco, J.M.; Valarezo, A.; Poblano-Salas, C.A.; Trápaga-Martínez, L.G.; Espinoza-Beltrán, F.J.; Muñoz-Saldaña, J. Effect of HVOF processing parameters on the properties of NiCoCrAlY coatings by design of experiments. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2014, 23, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, L. The Science and Engineering of Thermal Spray Coatings; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Zho, Z.; Li, S.; Mao, W. Influence of HVOF spray parameters on tribological behavior in CoCrFeNiMo high-entropy alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 518, 132856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, A.; Singh, S.; Anupam, A.; King, H.J.; Schulz, C.; Hall, C.; Ang, A.S.M. Nano- and micro-mechanical properties and corrosion performance of a HVOF sprayed AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coating. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 912, 165000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.W.; Lu, X.G.; Chang, Y.A. Solidification simulation using Scheil model in multicomponent systems. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2009, 30, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, A.; Bosi, E.; Anupam, A.; Hall, C.; Björklund, S.; Joshi, S.; Ang, A.S.M. Microstructure, multi-scale mechanical and tribological performance of HVAF sprayed AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coating. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 175962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, E.; Meghwal, A.; Singh, S.; Luzin, V.; Roccisano, A.; Hall, C.; Ang, A.S.M. Quantitative phase prediction in a eutectic AlCoCrFeNi2.1 high-entropy alloy HVOF coating using Scheil simulation. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1037, 182275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo-Calc Software. High-Entropy Alloys Database. Available online: https://thermocalc.com/products/databases/high-entropy-alloys/ (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Pelton, A.D. Equilibrium and Scheil–Gulliver Solidification. In Phase Diagrams and Thermodynamic Modeling of Solutions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.