Abstract

ABO3 perovskite oxides are a versatile class of materials whose surfaces and interfaces play essential roles in sustainable energy technologies, including catalysis, solid oxide fuel and electrolysis cells, thermoelectrics, and energy-relevant oxide electronics. The interplay between point defects and surface reconstructions strongly affects interfacial stability, charge transport, and catalytic activity under operating conditions. This review summarizes recent progress in understanding how oxygen vacancies, cation nonstoichiometry, and electronic defects couple to atomic-scale surface rearrangements in representative perovskite systems. We first revisit Tasker’s classification of ionic surfaces and clarify how defect chemistry provides compensation mechanisms that stabilize otherwise polar or metastable terminations. We then discuss experimental and theoretical insights into defect-mediated reconstructions on perovskite surfaces and how they influence the performance of energy conversion devices. Finally, we conclude with a perspective on design strategies that leverage defect engineering and surface control to enhance functionality in energy applications, aiming to connect fundamental surface science with practical materials solutions for the transition to sustainable energy.

1. Introduction

To meet global sustainability goals, much effort focuses on developing materials that can efficiently convert, store, and transport energy in harsh chemical and thermal environments [1,2,3,4]. Complex oxides, particularly ABO3 perovskites, are central to this effort. Owing to their chemical flexibility, electronic tunability, and thermal robustness, ABO3 perovskites are used in a wide range of energy technologies, including solid oxide fuel and electrolysis cells, photoelectrocatalysis, thermoelectrics, and energy-relevant oxide electronics [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Functional responses depend not only on bulk chemistry but also on the atomic-scale structure and stoichiometry at surfaces and interfaces, where broken coordination creates new structural and electronic states.

At such surfaces and interfaces, point defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies, cation nonstoichiometry, electronic carriers) and surface reconstructions are not merely imperfections but critically determine material stability and functionality. For instance, oxygen vacancies at surfaces strongly influence oxygen exchange kinetics in solid oxide fuel cells [7,11], redox chemistry in photoelectrocatalysis [12,13], and band alignment in oxide heterojunctions [14,15]. Similarly, surface reconstructions can stabilize polar terminations, modulate electronic transport, and create catalytically active sites [16]. Compared with bulk oxides, our understanding of surfaces has advanced more slowly, owing to the difficulty of preparing well-controlled single-crystal terminations. Recent advances in pulsed-laser deposition (PLD) [17,18,19,20] and molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE) [21,22,23,24,25] now provide atomically precise epitaxial templates, enabling systematic study and control of oxide surfaces. PLD is widely used for complex oxides because it readily accommodates multicomponent targets and controlled growth parameters such as oxygen partial pressure and substrate temperature, whereas MBE enables independent control of cation fluxes and oxygen activity with monolayer precision.

Along the <001> directions, ABO3 perovskites contain alternating AO and BO2 planes. Depending on the valence states of A and B-site cations, surfaces can be polar with charged (AO)+ or (AO)− and (BO2)− or (BO2)+ layers or non-polar with neutral (AO)0 and (BO2)0 layers. Ideally, cut surfaces of ABO3 are generally energetically unstable as bond breaking at the surface incurs a high surface energy [26]. Polar terminations are especially unstable due to a non-zero repeat-unit dipole. Consequently, oxide surfaces undergo relaxation, rumpling, and reconstruction to minimize surface energy and achieve stabilization [27]. Reconstructions, in particular, change surface periodicity, symmetry, and stoichiometry relative to the bulk, and therefore strongly govern functional properties.

Surface reconstructions in ABO3 oxides depend sensitively on preparation conditions such as chemical etching and annealing. Buffered hydrofluoric acid (BHF) etching with post-annealing is widely used to create an atomically ordered surface on single crystal oxide substrates [28], such as SrTiO3 (STO) and LaAlO3 (LAO). However, diverse reconstructions still emerge as a function of temperature and oxygen partial pressure (pO2) [29,30,31]. For TiO2-terminated STO (001), for example, reconstruction phase fields correlate strongly with temperature and pO2 [32].

Nevertheless, the influence of these factors on the surface reconstructions in perovskite oxides remains controversial. Such controversies mainly originate from insufficient consideration of surface cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry. Stoichiometric changes are central to polar compensation and surface stabilization. Modulating the A/B cation ratio can redistribute plane charges and neutralize dipoles on polar surfaces [33], while temperature and pO2 control the surface oxygen chemical potential, yielding families of reconstructions through oxygen nonstoichiometry [34]. Because polar terminations are intrinsically prone to compensation, their reconstructions are often highly sensitive and metastable, leaving open questions about structure–property relationships under realistic environments.

Several prior reviews have addressed complementary aspects of this problem, including polarity classification and electrostatic compensation in ionic crystals, atomically flat substrate preparation and termination control, and more general defect-engineering strategies in perovskites for catalysis and electrochemical energy conversion [35,36,37,38]. However, these works typically focus either on idealized single-crystal surfaces or on bulk defect chemistry and do not systematically organize the field around stoichiometry-driven surface reconstructions in epitaxial ABO3 films and their direct impact on energy-device performance. This review focuses on how cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry drive specific surface reconstructions in epitaxial ABO3 perovskites and how these reconstructions couple to sustainable-energy functions. We use epitaxial thin films and heterostructures as a common platform where growth conditions, strain, and stoichiometry can be precisely controlled, enabling direct links between reconstruction motifs, near-surface defect chemistry, and properties such as oxygen surface exchange, interfacial conductivity, and catalytic activity.

In this review, we adopt a simple unified framework in which cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry are treated as defect-mediated compensation mechanisms that act to minimize the surface free energy under given cation and oxygen chemical potentials. Oxygen nonstoichiometry (controlled mainly by temperature and pO2) tunes the concentration and distribution of oxygen vacancies and associated electronic carriers, while cation nonstoichiometry (set by growth fluxes, segregation, and volatility) modifies the A/B ratio and effective cation valence, redistributing charge between AO and BO2 planes. Different combinations of these parameters select distinct reconstruction motifs that stabilize polar terminations and create specific local bonding environments. In the following sections, we interpret experimental observations in titanates, aluminates, cobaltates, manganites, vanadates, and stannates within this defect–reconstruction framework, rather than developing a full quantitative theory, which is beyond the scope of this review.

2. Properties of Oxide Surfaces

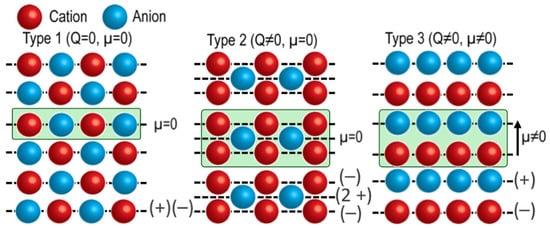

According to the classical surface model proposed by Tasker [39], oxide surfaces are classified into three types based on the net charge (Q) of planes parallel to the surface and the dipole moment (μ) of a neutral repeat unit perpendicular to the surface (Figure 1). Type-1 (non-polar) surfaces consist of neutral planes (Q = 0), and therefore have μ = 0. Type-2 (quadrupolar) surfaces consist of charged planes (Q ≠ 0) that can be grouped into a mirror-symmetric three-plane repeat unit, for example (−q, +2q, −q), so that μ = 0 and no long-range dipole forms. Type-3 (polar) surfaces consist of alternating positively and negatively charged planes, for example (+q, −q), yielding μ ≠ 0 and, in the ideal ionic limit, a diverging electrostatic energy unless compensated by reconstruction, electronic charge rearrangement, or defects. This divergence is often referred to as the polar catastrophe and is avoided by electrostatic compensation mechanisms that reduce the net dipole, including atomic rearrangements, defect formation, charge transfer, and adsorption. In ABO3 perovskites, for example, along the ⟨001⟩ direction, alternating AO and BO2 planes can form non-polar or polar terminations depending on their formal charges. The simplest non-polar case corresponds to neutral (AO)0 and (BO2)0 planes, which represents a Type-1 surface in Tasker’s classification, whereas Type-2 surfaces in perovskites involve charged planes arranged in a quadrupolar sequence with zero net dipole per repeat unit. Here, we focus on polar compensation through cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry and the associated surface reconstructions.

Figure 1.

Schematics of Type 1 (Q = 0, μ = 0), Type 2 (Q ≠ 0, μ = 0) and Type 3 (Q ≠ 0, μ ≠ 0).

The surface energies of Type-1 and Type-2 terminations are typically much lower than those of Type-3 terminations. However, polar surfaces can be stabilized by modifying the charge or stoichiometry of the outermost layers relative to the bulk [36]. For example, deviations of the surface composition from bulk stoichiometry can compensate for excess or deficient surface charge via structural reconstruction, while nominally stoichiometric polar surfaces may be stabilized by electronic charge redistribution driven by the built-in electrostatic field. Because polar perovskite surfaces are highly unstable and reactive, adsorption of atoms or ions can also provide charge compensation. In energy-related oxides, these different compensation mechanisms determine which surface terminations are accessible under operating conditions and, in turn, influence surface activity and interfacial charge transport in devices.

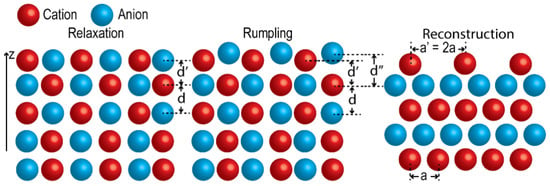

In principle, cleaving a crystal along any crystallographic plane yields an ideal termination preserving bulk atomic positions. In practice, only selected cleavage planes result in stable surfaces. For example, certain orientations, such as (111) surfaces of perovskite oxides, are polar, and thus exhibit high surface energies [40]. The number and type of cation–oxygen bonds also influence surface stability. Breaking these bonds generates forces that displace atoms from their ideal bulk positions, resulting in structural distortions, commonly described as relaxation, rumpling, and reconstruction (Figure 2) [27].

Figure 2.

Schematics of surface relaxation, rumpling and reconstruction.

All of these distortions are driven by surface energy minimization. Relaxation modifies the interlayer spacing of near-surface layers. Rumpling occurs when cations and anions in the same plane are displaced in opposite directions normal to the surface, driven by different electrostatic forces. Both relaxation and rumpling change interatomic distances but preserve the bulk periodicity. In contrast, reconstruction produces a new periodicity and often a modified stoichiometry relative to the bulk. Reconstructions are especially prevalent in ABO3 perovskites and can extend several unit cells (up to ~10 layers) into the subsurface. Because reactions and transport in many energy devices are governed within a few nanometers of the surface [41,42,43,44], such reconstructions can strongly affect local electronic structure, adsorption energetics, and ion exchange pathways.

In discussing reconstructions, it is useful to distinguish thermodynamic and kinetic control. At a given temperature and set of chemical potentials, for example, the oxygen chemical potential set by pO2, the thermodynamically stable structure is the one that minimizes the surface free energy. In practice, however, atomic diffusion, defect migration, and cation redistribution can be slow, so as-grown films or rapidly cooled samples may retain metastable reconstructions that reflect the growth rate, annealing time, and cooling history rather than the equilibrium phase diagram. Extended annealing at elevated temperature and controlled pO2 tends to drive surfaces toward thermodynamic ground states, whereas non-equilibrium growth conditions often stabilize kinetically trapped reconstruction motifs.

Density functional theory (DFT) has been widely used to analyze stoichiometry-driven reconstructions in ABO3 perovskites. Most of the studies cited here employ slab models with explicit AO and BO2 terminations and vary the oxygen chemical potential and cation configuration to obtain surface energies and defect formation energies as functions of cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry. These calculations identify stable and metastable reconstructions at given chemical potentials and link oxygen vacancy formation energies and cation segregation tendencies to the reconstruction phase fields observed experimentally. For correlated systems such as cobaltates, manganites, and vanadates, DFT+U or hybrid functionals are often used to capture changes in B-site valence. We draw on these theoretical results where they clarify the role of cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry in reconstruction.

3. Influence of Cation and Oxygen Nonstoichiometry on Surface Reconstructions of Perovskite Oxides

Oxygen nonstoichiometry provides a powerful degree of freedom for tuning the structural and functional properties of perovskite oxides. Since no oxide surface is ideally infinite or defect-free, oxygen vacancies are prevalent and often dominate surface chemistry. In ABO3 perovskites, oxygen vacancies are key point defects that strongly influence structural, electronic, optical, and electrochemical behavior [45,46,47,48,49]. Ordered arrangements of surface oxygen vacancies can serve as charge compensating configurations and directly drive surface reconstructions [50]. Oxygen vacancies also modify the surface electronic structure, which in turn affects surface polarity and stability [51].

Cation nonstoichiometry plays an equally important role. Unlike oxygen defects, which can often be annihilated or replenished by O2 annealing, deviations in cation stoichiometry are much more difficult to compensate in perovskites. Small cation deviations may be accommodated by point defects such as cation vacancies, whereas larger deviations commonly generate extended defects or even new surface phases [52,53,54]. Film growth conditions, such as temperature, pO2, and cation flux, govern cation nonstoichiometry, and certain A-site cations (e.g., Sr2+, Ba2+, Pb2+) are particularly prone to segregate to the surface, modulating termination and thereby inducing reconstruction [55]. For example, La1-xSrxMnO3 (LSM) often exhibits surface Sr enrichment that modifies the near-surface stoichiometry and induces new reconstruction phases. Similarly, adjusting the Ti/Sr ratio in STO (110) surfaces yields different reconstructions and terminations [33]. Although cation nonstoichiometry is frequently invoked to stabilize polar surfaces, it can also alter reconstructions even on nominally non-polar terminations.

Thus, oxygen and cation nonstoichiometry should be understood and controlled jointly to manipulate surface behavior and stability in ABO3 oxides. In practice, oxygen vacancy concentration and cation ratios can be tuned by thermal treatments and epitaxial growth parameters such as temperature, laser fluence, and pO2, enabling access to a wide variety of reconstructions and terminations. In the following subsections, the effects of stoichiometric control on surface reconstructions are discussed for representative perovskite oxide systems that are particularly relevant to renewable energy applications.

3.1. Titanate Surfaces

Titanate perovskites, especially STO, are widely used as photocatalysts [56,57,58], dielectrics [59,60,61] and oxide electronic platforms, and substrates for complex-oxide heterostructures [62,63,64,65,66,67]. In these contexts, control over oxygen vacancies and cation stoichiometry is essential for optimizing light absorption, charge separation, and interfacial stability.

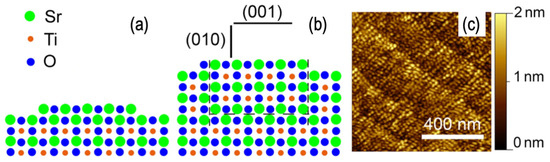

On single-crystal STO (001), oxygen nonstoichiometry and A-site volatility couple strongly to surface reconstructions. BHF etching followed by thermal annealing is commonly used to obtain TiO2-terminated (001) surfaces. A recent study demonstrated that (2 × 2) reconstructions on STO (001) can also be stabilized through pO2-controlled CO2-laser annealing at ~1300 °C without BHF etching over a pO2 range of 7.5 × 10−3 to 7.5 × 10−2 Torr [68]. Homoepitaxial STO films grown on these substrates inherit the same reconstruction, indicating that high-temperature annealing fixes the surface termination and stoichiometry prior to growth. O2-annealed STO (001) surfaces exhibiting the (√13 × √13)R33.7° reconstruction show negligible Sr segregation and are close to a stoichiometric TiO2-terminated state [31], whereas CO2-laser annealing followed by homoepitaxial growth at pO2 = 7.5 × 10−2 Torr leads to a progressive evolution from (√13 × √13)R33.7° to (2 × 2) reconstructions as the near-surface Sr content increases [69]. Above a critical thickness (~38 nm), rock-salt-type SrO double-layer islands form, creating SrO-rich domains embedded in a TiO2-terminated matrix and establishing a direct link between Sr nonstoichiometry and the (2 × 2) reconstruction (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic of (a) surface rock-salt-type SrO double layer island surrounded by a SrO single layer and (b) formation of antiphase boundaries in (001) and (010) direction. (c) Surface morphology of 20 nm STO thin film determined by in situ atomic force microscopy. Reprinted from Ref. [69] with permission of Springer Nature.

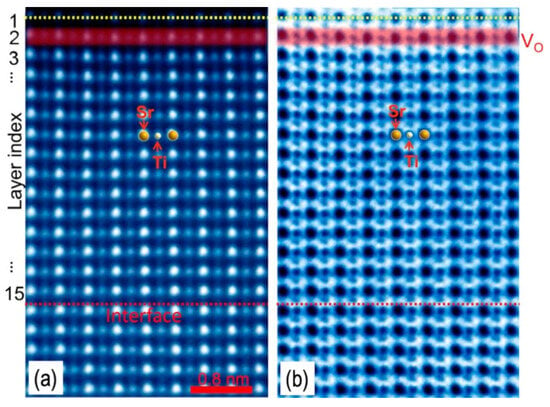

Compared to single-crystal STO (001), the polar STO (011) and STO (111) surfaces exhibit a different balance between oxygen vacancies and cation rearrangements. On STO (011), homoepitaxial growth under ultra-high vacuum on Nb-doped substrates preserves a well-defined (4 × 1) reconstruction while continuously generating oxygen vacancies [70]. In this regime, oxygen supplied from subsurface layers feeds the growing film, and the reconstructed surface acts as a reservoir for vacancy formation (Figure 4). Thermally stimulated depolarization current measurements and DFT calculations indicate that STO (011) hosts a higher oxygen vacancy concentration than the (001) and (111) surfaces, consistent with a TiO-terminated topmost layer [71]. On STO (110), varying surface cation coverage yields two distinct reconstruction families, (n × 1) and (2 × n), that can be reversibly tuned by selectively depositing Ti or Sr followed by annealing [72]. Increasing Ti coverage drives a transition from (n × 1) to (2 × n) structures associated with a Ti-rich overlayer whose local coordination evolves from corner-sharing tetrahedra to edge-sharing octahedra as packing density increases. Modulating laser fluence during PLD growth provides an additional handle on the A/B-site ratio. Ti-rich films grown at high fluence exhibit (2 × 4) reconstructions and surface roughening, whereas Sr-enriched films obtained at low fluence favor mixtures of (n × 1) structures [73].

Figure 4.

High concentration of oxygen vacancies located near the surface (layer 2 which is highlighted in red) of the 15 monolayer STO film determined by (a) high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) and (b) annular bright field (ABF) images. The yellow lines mark the film surface (top) and the interface between the STO film and the substrate (bottom). Reprinted from Ref. [70] with permission of AIP Publishing.

On STO (111), a series of reconstructions, including (2 × 2), (3 × 3), (4 × 4), (√7 × √7)R19.1°, and (√13 × √13)R13.9°, emerges as a function of annealing temperature and pO2 [34]. Transitions among these reconstructions correlate with changes in TiO2 enrichment, with higher annealing temperatures producing surfaces with lower TiO2 excess [34]. DFT and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) identified the atomic structures of the (√7 × √7)R19.1° and (√13 × √13)R13.9° reconstructions as single-layer TiO2 terminations containing fewer excess TiO2 units than earlier (2 × 2) models [74]. These single-layer terminations, in contrast to the TiO2 double-layer reconstructions on STO (001), indicate that Sr depletion and the resulting cation vacancies stabilize low-excess-TiO2 configurations on STO (111). These changes in termination and Sr content modify the near-surface band bending and density of states, which in turn influence the surface properties of STO.

Overall, titanate surfaces demonstrate how coupled oxygen and cation nonstoichiometry generate families of reconstructions, (√13 × √13), (2 × 2), (n × 1), (2 × n), and related motifs, that act as polarity-compensating structures. These reconstructions, in turn, control interfacial electronic states, defect reservoirs, and chemical reactivity, making stoichiometric engineering a central design strategy for titanate-based photocatalysts and oxide-electronic interfaces. In the following section, we extend these concepts to aluminate perovskites, where similar polar-compensation mechanisms operate but with different cation chemistry and stronger tendencies toward A-site segregation.

3.2. Aluminate Surfaces

Aluminates, such as LAO, are central to polar oxide heterointerfaces, where defect–reconstruction coupling governs electronic conductivity and interfacial confinement [63,75]. These effects are increasingly exploited in transparent conducting oxides and oxide electronics with potential roles in sustainable energy and information technologies.

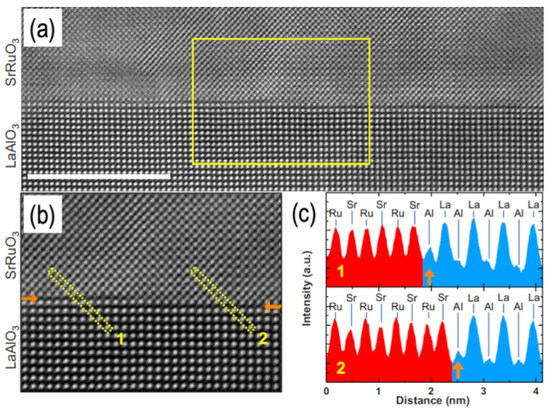

On LAO (001), both cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry participate in polarity compensation. Atomically flat, singly AlO2-terminated surfaces can be produced by high-temperature annealing followed by deionized-water leaching, which dissolves La-rich species and yields a uniform AlO2 termination that remains stable during thin-film growth [76]. As shown in Figure 5, cross-sectional high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) of an SrRuO3/LAO (001) heterostructure reveals the RuO2–SrO–AlO2–LaO stacking sequence across the interface and a one-unit-cell surface step, confirming an AlO2-terminated LAO (001) substrate and an atomically sharp interface. Coaxial impact-collision ion scattering spectroscopy on water-leached LAO (001) further indicates that ≥120 min leaching yields a singly AlO2-terminated surface (normalized La:Al ≈ 1:105), whereas a 1 min leached surface loses single termination upon 700 °C annealing. Thus, extended leaching provides a robust, growth-relevant termination [76]. Aberration-corrected TEM combined with DFT also shows that La–O-terminated reconstructions can also be energetically favorable over a wide range of oxygen chemical potentials. In those structures, La vacancies in the top La–O layer compensate the polar charge, and a (√2 × √2)R45° (LaO)1/2 model emerges as a particularly stable configuration [77].

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional STEM analysis on SrRuO3/LAO (001) interfaces. (a) HAADF-STEM image measured along the [100] zone axis of LAO. The scale bar corresponds to 10 nm. (b) Zoomed-in HAADF-STEM image from the area marked by the solid box in (a). Both images show a sharp SrO-AlO2-terminated interface and a one-unit-cell-high step. The interfaces in the left- and right-hand sides of (b) are marked by solid arrows. (c) Line profiles (1 and 2) of HAADF-STEM intensity corresponding to the dashed boxes 1 and 2 marked in (b). Reprinted from [76] with permission of the American Physical Society.

For other orientations, such as LAO (011), the balance between surface polarity and cation nonstoichiometry leads to distinct reconstructions. After annealing at 1050–1250 °C in dry oxygen, an Al-terminated (2 × 1) structure is observed on LAO (011), whereas LAO (111) does not exhibit the same reconstruction [78]. Earlier work reported a (3 × 1) reconstruction on LAO (011) [79], suggesting that multiple Al-rich compensation structures are accessible depending on thermal history. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) indicates additional AlOx components on the (011)-terminated surface and significant Al enrichment on LAO (111), again pointing to cation nonstoichiometry as a primary compensation mechanism for polar aluminates.

Collectively, aluminate surfaces show that subtle variations in A-site occupancy and oxygen content stabilize different reconstructions and terminations, which in turn influence band alignment, interfacial conductivity, and growth templates for subsequent perovskite layers. Precise control of La/Al ratios and oxygen chemical potential is therefore crucial for engineering LAO-based heterostructures for oxide electronics and energy applications.

In LAO-based heterostructures, such reconstructions are directly tied to band alignment and charge transfer. At LAO/STO (001) interfaces, for example, the choice between AlO2-terminated and LaO-terminated LAO, together with associated cation nonstoichiometry and oxygen vacancies, changes the interface dipole and the relative band positions across the junction. This modifies band bending in STO, the onset of interfacial conduction, and the carrier density in the confined electron system [75,80,81]. Building on these polarity and termination-control concepts in titanates and aluminates, we next consider cobaltate perovskites, where surface reconstructions are strongly coupled to redox-active B-site cations and oxygen-reduction kinetics.

3.3. Cobaltate Surfaces

Cobaltate perovskites, such as LaCoO3 (LCO) and (La,Sr)CoO3 (LSC), are leading candidates for oxygen evolution and reduction electrocatalysts in solid oxide fuel cells and electrolysis cells [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. Their surface reconstructions, driven by oxygen nonstoichiometry and cation redistribution, directly impact catalytic turnover frequencies and long-term stability in oxidizing and reducing environments [90,91,92,93].

In cobaltates, oxygen vacancies can be generated by reduction of Co3+ to Co2+ (LCO) or by substitution of Sr2+ for La3+ (LSC), with each oxygen vacancy acting as a doubly charged defect in Kröger–Vink notation. Atomistic simulations predict that, for LCO and LSC, families of (2n × 1) reconstructions (n = 1–5) are more stable than simpler (√2 × √2) structures on the (001), (011), and (111) surfaces [92]. This is consistent with experimental observations on epitaxial LCO (111) thin films [94]. For (001) surfaces, the most stable terminations were identified as O–Co–O (LCO) and O–La (LSC), with oxygen vacancies located between Co2+/Sr2+ cations in the first and third layers. Photoemission measurements on LCO (001) reported O–Co–O termination [95], in good agreement with these predictions. For (011) surfaces of LCO/LSC, the most stable structure was an O-terminated surface with two Co2+/Sr2+ cations in the second layer and an oxygen vacancy in the first layer. For (111) surfaces, the lowest-energy terminations were a Co-terminated surface for LCO and a La–O–O–O–terminated surface (LaOOO) for LSC.

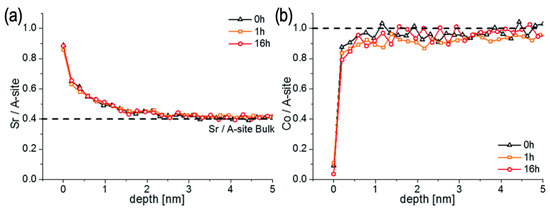

Experimentally, surface-sensitive probes corroborate this picture and highlight pronounced A-site segregation in Sr-containing cobaltates. Low-energy ion scattering (LEIS), XPS, and coherent Bragg rod analysis (COBRA) on epitaxial LSC films reveal Sr-rich surface layers after high-temperature treatment [90,91,93,96]. As shown in Figure 6, LEIS depth profiles for an as-deposited LSC film and for films annealed at 600 °C for 1 h and 16 h reveal a Sr-enriched, Co-depleted termination that persists after annealing, indicating that the Sr-rich surface is stable under these oxidizing conditions [93]. COBRA revealed that the top perovskite layer of LSC films can have an A-site Sr fraction of ~60%, and that discrete particles epitaxially grown on the film surface may approach a SrCoO3-δ-like composition, with their outermost regions covered by electrochemically less active Sr-rich phases [90]. DFT calculations found that the most stable LSC (001) surface is an AO-terminated layer containing approximately 75% Sr on the A site, and that an AO surface with 100% Sr can become stable at sufficiently high oxygen chemical potentials [42].

Figure 6.

LEIS depth profiles showing the Sr/A-site (a) and the Co/A-site (b) ratio of an as-grown LSC sample and of two LSC samples that were annealed at 600 °C for 1 and 16 h. Reprinted from ref. [93] with permission of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

These defect-driven reconstructions directly influence the activity and durability of the oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. In epitaxial LSC thin films, the ORR resistance increases from about 0.6 Ω·cm2 for a pristine film to almost 4 Ω·cm2 after annealing at 600 °C for 10 h owing to surface Sr segregation [93]. Strategies that suppress Sr segregation can substantially improve ORR kinetics. Decorating LSC thin films with a Ruddlesden–Popper oxide enhances the apparent surface oxygen exchange coefficient by up to two orders of magnitude [42], and LSM decoration yields roughly an order-of-magnitude increase [44].

Taken together, these results show that Sr-rich, vacancy-stabilized surfaces can initially enhance oxygen exchange by providing mobile oxygen species and active Co sites, but they also promote the formation of secondary Sr-rich phases and passivating overlayers under prolonged operation. As a result, controlling the balance between surface Sr enrichment, oxygen vacancy concentration, and reconstruction type is critical for designing cobaltate electrodes with both high activity and long-term stability in fuel cell and electrolysis environments. To further explore the interplay between A-site segregation, oxygen vacancies, and reconstruction in electrochemically active cathodes, we then turn to manganites such as LSM.

3.4. Manganite Surfaces

Manganite perovskites such as LaMnO3 and LSM are widely used as solid oxide cell cathodes and in solar thermochemical redox cycles. Their ability to accommodate oxygen defects and surface reconstructions governs oxygen exchange kinetics and, consequently, device efficiency in clean fuel generation and electrochemical energy conversion [44,97,98,99,100].

In LSM, surface Sr enrichment is a prominent manifestation of cation nonstoichiometry. DFT calculations for LSM with x = 0.25 show that, under reducing conditions, Sr-enriched surfaces become thermodynamically favored and lead to partial SrO terminations in which a SrO layer only partially covers the underlying MnO2 [101]. This stabilization is attributed to an increased formation of positively charged oxygen vacancies at the surface, which are locally charge-compensated by Sr2+. Experimental studies on epitaxial LSM (Sr = 0.3) films grown on STO (001) substrates confirm surface Sr segregation using LEIS and XPS [102], directly linking A-site nonstoichiometry to modified surface terminations and reconstructions.

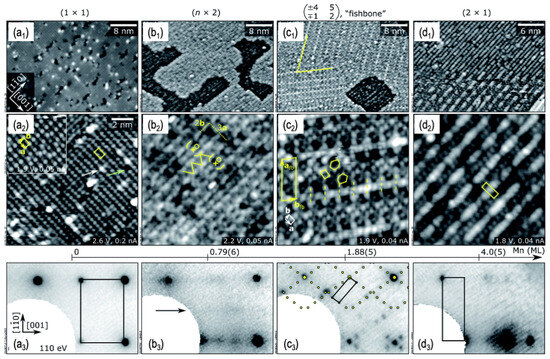

Beyond Sr enrichment, variations in the A/B-site ratio can drive rich reconstruction behavior on polar manganite surfaces. For epitaxial LSM (Sr = 0.2) films grown on single-crystal STO (011), LEIS, XPS, and STM reveal a sequence of reconstructions as the La/Mn ratio is tuned [103]. La-rich surfaces exhibit a (1 × 1) reconstruction, while increasing Mn content leads to phase separation and the emergence of (n × 2) reconstructions. Further Mn enrichment produces characteristic “fishbone” morphologies and ultimately a (2 × 1) reconstruction without phase separation (Figure 7). These structures are interpreted as polarity-compensating arrangements on LSM (011), stabilized by cation nonstoichiometry and associated oxygen defects, and they demonstrate how tuning the A/B ratio can systematically navigate between La-rich and Mn-rich reconstructions.

Figure 7.

The surface reconstructions of LSM (011) are shown by STM with (a1–d1) large-area (40 × 28 nm2), (a2–d2) closed-up (12 × 12 nm2) images and (a3–d3) low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) patterns. The overlaid boxes and markers highlight the surface unit cells in (a2–d2,a3–d3). Reprinted from ref. [103] with permission of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

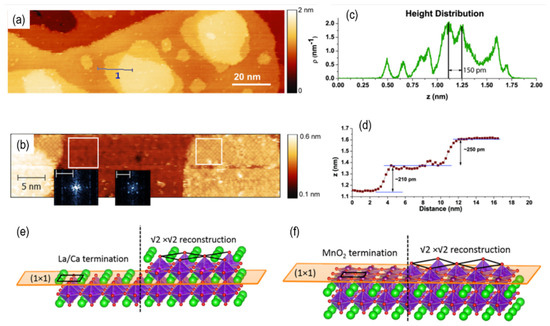

Oxygen nonstoichiometry independently modulates surface structure in manganites. For epitaxial La5/8Ca3/8MnO3 (LCM) films grown on STO (001) by PLD, changing the oxygen pressure during growth from 50 to 20 mTorr transforms a relatively disordered surface with a large fraction of A-site termination into a nearly atomically ordered surface with a larger B-site fraction [104]. At 50 mTorr, a (√2 × √2)R45° reconstruction dominates, whereas at 20 mTorr a mixed reconstruction combining (√2 × √2)R45° and (1 × 1) structures appears. Subsequent analysis associates the (√2 × √2)R45° reconstruction with (La,Ca)O-terminated regions and the (1 × 1) reconstruction with MnO2-terminated regions, accompanied by Ca enrichment in the top MnO2 layer (Figure 8). These results emphasize that pO2-dependent changes in Mn mobility and vacancy formation can reconfigure both termination and reconstruction on LCM surfaces.

Figure 8.

(a) Large scale STM topography of the surface of LCM film and (b) two distinct terminations with different reconstructions shown by atomically resolved image of the surface. The color scale in (a,b) represents surface height. Two different lattice structures are highlighted by fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the white box regions in the inset of (b) with 4 nm−1 scale bar. Half-unit-cell intervals are shown by (c) height distribution and (d) line profile of line “1” in (a). Schematic of (1 × 1) and (√2 × √2)R45° surfaces for (e) (La, Ca)O and (f) MnO2 termination. Black lines, green, red, and purple atoms are representing the unit cell, La/Ca, O, and Mn, respectively. Reprinted from ref. [104] with permission of AIP Publishing.

Taken together, manganites show how coupled oxygen and cation nonstoichiometry produce a spectrum of polarity-compensating reconstructions through Sr segregation, La/Mn ratio tuning, and oxygen pressure control, which strongly influence oxygen exchange kinetics and cathode degradation. Rational cathode design therefore requires explicit consideration of nonstoichiometry-driven surface reconstructions, not just bulk composition.

3.5. Other Systems: Vanadate and Stannate Surfaces

Beyond canonical titanates, aluminates, cobaltates, and manganites, emerging perovskite systems such as SrVO3 (SVO) and BaSnO3 (BSO) offer additional opportunities to study and exploit nonstoichiometry-driven surface reconstructions [105,106,107]. These materials are of growing interest as conducting electrodes, transparent conductors, and high-mobility oxide semiconductors in energy and electronic applications [108,109,110,111].

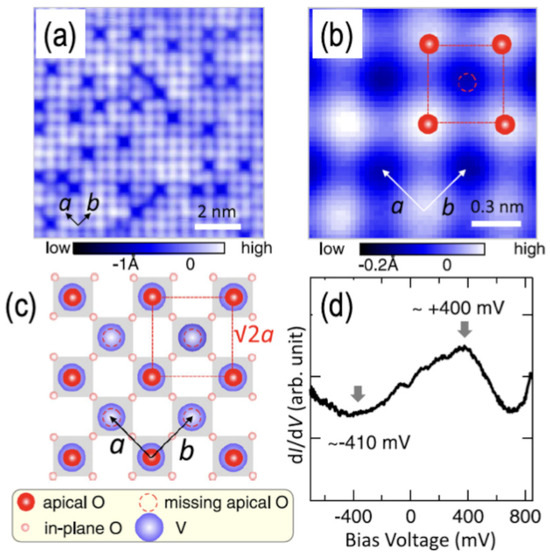

For epitaxial SVO thin films growth on Nb-doped STO (001), oxygen nonstoichiometry and film thickness strongly influence surface reconstructions and terminations. Epitaxial SVO films grown on Nb-doped STO (001) exhibit a (√2 × √2)R45° reconstructed surface associated with a VO2-terminated top layer bearing ~50% apical-oxygen coverage (a VO2.5-like termination) [112]. Using an Sr2V2O7 target supplies additional oxygen during growth and enables apical-O adsorption on the VO2 layer. As shown in Figure 9, STM resolves the (√2 × √2) lattice, and angle-dependent photoemission indicates an enhanced V5+ fraction at the surface, consistent with partial oxidation in the VO2.5-like termination. In ultrathin SVO films (3–5.7 nm) grown on reconstructed STO (001) substrates, STM and scanning tunneling spectroscopy reveal the coexistence of (√2 × √2)R45° and (√5 × √5)R26.6° reconstructions for thicknesses below ~3.8 nm, while thicker films (5.7 nm) exhibit predominantly the (√5 × √5)R26.6° structure [49]. These observations point to interfacial oxygen vacancies and thickness-dependent screening as key factors stabilizing different reconstruction motifs. Additional studies show a reduction in vanadium oxidation state within the first few unit cells near the film/substrate interface, implying significant oxygen vacancy concentrations that likely underpin the vacancy-induced reconstructions [113]. These reconstruction-driven changes in V oxidation state and near-surface density of states imply modified band bending and charge transfer at SVO-based heterointerfaces, linking stoichiometry-controlled reconstructions directly to band alignment in this correlated metal [114,115,116]. More recently, hybrid MBE using volatile metalorganic precursors has enabled growth of stoichiometric SVO films on (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2TaAlO6)0.7 (LSAT) (001) with well-defined (2 × 2) reconstructions [117,118], highlighting the role of controlled oxygen and cation fluxes in tailoring surface structure.

Figure 9.

Typical topographic images of SVO (001) surface and metallic tunneling spectra (110 nm thick film). (a,b) Topographic images with sample bias voltage Vs = −100 mV (a); the enlarged image in (b) shows the (√2 × √2)R45° structure. (c) The model used to generate the topographic image with a (√2 × √2)R45° structure. (d) Spatially averaged tunneling spectra (dI/dV) obtained from the surface. a and b denote the in-plane lattice vectors of the surface unit cell. Reprinted from ref. [112] with permission of the American Physical Society.

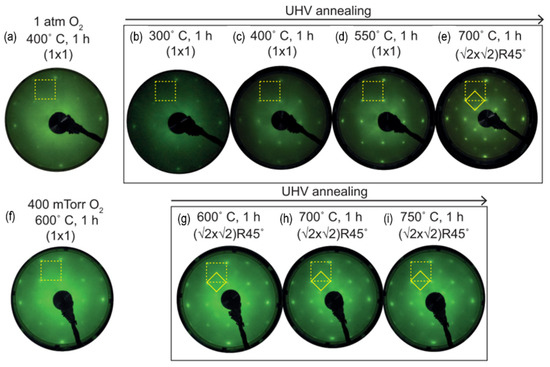

In epitaxial BSO thin films, a wide-bandgap (~3.1 eV) and high electron mobility make this stannate attractive for oxide electronics and transparent conducting layers [50], but its surface properties are only beginning to be explored. Atomically flat BSO single crystals can be prepared by deionized-water leaching followed by O2 annealing at temperatures above ~1250 °C, yielding wide terraces with predominantly SnO2-terminated surfaces and minor BaOx contributions attributed to Ba segregation [119]. On epitaxial BSO films grown on STO (001), oxygen vacancies drive reversible changes between (1 × 1) and (√2 × √2)R45° reconstructions: UHV annealing at up to 550 °C preserves a (1 × 1) surface, whereas annealing at 700 °C induces a (√2 × √2)R45° reconstruction that can be switched back to (1 × 1) by annealing in oxygen and re-established by subsequent UHV annealing (Figure 10) [120]. This reversibility demonstrates that oxygen vacancies are essential for stabilizing reconstructed BSO surfaces and that their concentration can be modulated by redox cycling without strong substrate influence.

Figure 10.

LEED patterns of BSO thin films after annealing at various conditions. (1 × 1) reconstructed surface shown at (a) 400 °C in 1 atm oxygen, (b–d) 300, 400, and 550 °C in UHV condition, respectively. (1 × 1) surface changed to (√2 × √2)R45° reconstructed surface at (e) 700 °C in UHV condition. The reversibly switching of (√2 × √2)R45° reconstructed surface back to the (1 × 1) surface was represented at (f) 600 °C in 400 mTorr oxygen. (g–i) (√2 × √2)R45° reconstructed surface is reproduced by additional UHV annealing. The yellow dashed squares indicate the LEED spots corresponding to the (1 × 1) and (√2 × √2)R45° surface reconstructions. Reprinted from ref. [120] with permission of the American Physical Society.

MBE studies further map the relationship between growth conditions, nonstoichiometry, and BSO surface reconstructions. By synthesizing La-doped BSO films on DyScO3(001) under an excess SnO2 flux, these studies constructed a phase diagram in pO2–temperature space that delineates BaO-, Ba2SnO4-, BSO-, and SnO2-rich regimes [121]. Stoichiometric BSO films grown in the stability region show (1 × 1) surfaces, whereas Ba-rich conditions yield (2 × 1) reconstructions associated with disordered Ruddlesden–Popper phases, and Sn-rich conditions lead to rough, three-dimensional morphologies. Similar (1 × 1) surfaces without additional reconstructions are observed for La-doped BSO grown on Si (001) using STO buffer layers [122], indicating that near-stoichiometric BSO favors unreconstructed terminations under appropriate growth conditions.

These vanadate and stannate systems underscore that nonstoichiometry-driven reconstructions are not limited to classical perovskites: oxygen vacancies, cation excesses, and film thickness can stabilize distinct surface motifs that, in turn, control conductivity, transparency, and interfacial transport. As these materials are integrated into energy-relevant devices, systematic control of cation and oxygen stoichiometry at their surfaces will be essential for realizing their full functional potential.

3.6. Comparative Trends Across ABO3 Families

Within these ABO3 families, several common themes emerge when comparing titanates, aluminates, cobaltates, manganites, vanadates, and stannates. Across all systems, the dominant reconstruction motifs are governed by the same defect-mediated polar-compensation framework, in which combinations of oxygen nonstoichiometry and cation nonstoichiometry act together to reduce the surface dipole and stabilize polar terminations. Titanates and aluminates provide canonical examples, where oxygen vacancies and imbalances in the A- and B-site cation contents generate families of (√13 × √13), (2 × 2), (n × 1), and related reconstructions on (001), (011), and (111) surfaces. These systems establish the basic electrostatic and chemical principles that underlie more complex, device-oriented oxides.

Cobaltates and manganites add an additional layer of complexity by coupling reconstruction and defect chemistry to redox-active B-site cations and electrochemical functionality. In LSC and LSM, for example, A-site Sr segregation and oxygen nonstoichiometry not only stabilize particular reconstructed terminations but also redistribute Co or Mn valence states, with direct consequences for oxygen surface exchange, area-specific resistance, and cathode stability under operating conditions. Compared to titanates and aluminates, these systems thus highlight how similar polar-compensation motifs acquire different functional roles when embedded in electronically active, mixed-conducting perovskites. Across both cobaltates and manganites, Sr segregation therefore has a dual role, with moderate enrichment sometimes beneficial for ORR kinetics and extensive segregation generally detrimental due to the formation of blocking Sr-rich surface layers.

Vanadates and stannates illustrate how stoichiometry-driven reconstructions manifest in more metallic or wide-bandgap platforms. In SVO, thickness- and oxygen-chemical-potential-dependent reconstructions tune screening and near-surface electronic structure in a correlated metal, whereas in BSO and related stannates, oxygen-vacancy–stabilized reconstructions evolve on high-mobility, wide-bandgap surfaces that are attractive for transparent and power electronics. Together with the titanate, aluminate, cobaltate, and manganite systems, these examples show that, although reconstruction motifs and accessible stoichiometry ranges differ with chemistry and electronic structure, controlling oxygen chemical potential, cation fluxes, and epitaxial strain provides a general route to engineer surface reconstructions, defect reservoirs, and the performance of energy-relevant ABO3 perovskites. Table 1 summarizes representative stoichiometry-driven surface reconstructions in selected epitaxial ABO3 perovskites, highlighting typical orientations/terminations, dominant reconstruction motifs, and the primary stoichiometric control parameters.

Table 1.

Representative stoichiometry-driven surface reconstructions in epitaxial ABO3 perovskites and their dominant control parameters.

4. Future Perspectives

The aforementioned perovskites demonstrate that cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry, coupled to surface reconstructions, are key design parameters for energy-relevant oxides. Three directions are particularly promising: leveraging epitaxial strain, harnessing ultrathin-film and octahedral-rotation effects, and integrating operando measurements with data-driven modeling.

First, controlled epitaxial growth offers a practical route to systematically tune nonstoichiometry. Growth temperature, pO2, and cation flux set cation ratios and oxygen-vacancy concentrations, while lattice-mismatch strain shifts defect formation energies and reconstruction stability. Strain engineering is already widely used to tailor electronic structure, oxygen transport, and defect chemistry in perovskite films [46,123,124,125,126], accessible via substrate choice or by thickness variation on a single substrate. For example, strain-induced defects can alter STO (011) reconstructions [127] and thermal mismatch between STO and Si has been used to continuously tune tensile strain and break inversion symmetry at STO (001) surfaces [128]. Mapping strain–nonstoichiometry–reconstruction phase diagrams for key materials would provide a practical design framework.

Second, ultrathin films only a few unit cells thick introduce additional symmetry breaking and interfacial constraints that can qualitatively change surface reconstructions. A previous study showed that octahedral rotations in ultrathin SrIrO3 on STO (001) drive thickness-dependent transitions between (2 × 2), (√2 × √2)R45°, and (1 × 1) surfaces [129]. In contrast, DFT calculations indicate that c(4 × 4)-like reconstructions can remain favorable for CaTiO3 and STO (001) even when octahedral rotations are varied [130]. This contrast highlights open questions about the interplay among octahedral distortions, thickness, and nonstoichiometry. Systematic studies tracking rotations, defect distributions, and reconstructions versus strain, thickness, and redox conditions could enable rotations to serve as an additional programmable “knob” for surface structure and function.

Finally, most atomic-scale information still comes from ultra-high-vacuum conditions, whereas real devices operate in high pO2, humid, or electrochemical environments. Expanding in situ and operando methods, such as ambient-pressure XPS [131,132], environmental TEM [133,134], in situ LEED and STEM [135,136], and synchrotron-based methods [137,138], on well-controlled epitaxial films will be crucial for connecting specific reconstructions to oxygen exchange kinetics and catalytic activity under realistic conditions. Coupling such data to high-throughput DFT calculations [139,140] and machine-learning models [141,142] for surfaces and defects can deliver multi-scale descriptions, in which reconstruction-dependent defect concentrations and reaction energetics feed directly into kinetic models of oxygen reduction and evolution reactions, oxygen transport, and degradation. In the long term, this combination of epitaxial control, ultrathin-film engineering, and data-driven modeling could enable inverse design of oxide surfaces and interfaces tailored for the global energy transition.

5. Conclusions

Cation and oxygen nonstoichiometry, together with the surface reconstructions they stabilize, are key design parameters for perovskite and related oxide surfaces in sustainable-energy technologies. Across titanates, aluminates, cobaltates, manganites, and emerging vanadate and stannate systems, polarity compensation and near-surface defect chemistry are inseparable from functional responses such as oxygen exchange kinetics, catalytic activity, and interfacial transport. The case studies discussed here show that controlling growth temperature, pO2, and cation flux in epitaxial films enables families of reconstructions that are difficult to realize in bulk crystals. Combining stoichiometric control with epitaxial strain and ultrathin-film engineering offers a route to bias which reconstructions and defect configurations are stabilized at oxide surfaces. Realizing this potential will require in situ and operando measurements under realistic environments, linked to multiscale and data-driven models that connect specific reconstructions to device-level performance. Together, these approaches can turn nonstoichiometry and surface reconstruction from complications into practical levers for designing oxide materials for energy conversion and storage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and supervision, D.L.; investigation, H.R.C., E.S., G.Y. and M.E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Y. and M.E.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L.; visualization, H.R.C. and E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation under NSF Award Number DMR-2340234.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Bertaglia, T.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Crespilho, F.N. Eco-friendly, sustainable, and safe energy storage: A nature-inspired materials paradigm shift. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 7534–7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Pandey, S.; Shahwal, R.; Sur, A. Recycling of waste into useful materials and their energy applications. In Microbial Niche Nexus Sustaining Environmental Biological Wastewater and Water-Energy-Environment Nexus; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 251–296. [Google Scholar]

- Worku, A.K.; Ayele, D.W.; Deepak, D.B.; Gebreyohannes, A.Y.; Agegnehu, S.D.; Kolhe, M.L. Recent advances and challenges of hydrogen production technologies via renewable energy sources. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2300273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubani, M.E.; Chalaki, H.R.; Yang, G.; Lee, D. Multifunctional Electrocatalysts for Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells; Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC Publishing): London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- El Loubani, M.; Yang, G.; Kouzehkanan, S.M.T.; Oh, T.-S.; Balijepalli, S.K.; Lee, D. Influence of redox engineering on the trade-off relationship between thermopower and electrical conductivity in lanthanum titanium based transition metal oxides. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 9007–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Nam, S.-H.; Han, G.; Fang, N.X.; Lee, D. Achieving Fast Oxygen Reduction on Oxide Electrodes by Creating 3D Multiscale Micro-Nano Structures for Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 50427–50436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; El Loubani, M.; Handrick, D.; Stevenson, C.; Lee, D. Understanding the influence of strain-modified oxygen vacancies and surface chemistry on the oxygen reduction reaction of epitaxial La0.8Sr0.2CoO3-δ thin films. Solid State Ion. 2023, 393, 116171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M.; Li, Z.; Israr, M.; Khan, A.; Luo, W.; Wang, C.; Shao, Z. Perovskite type ABO3 oxides in photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and solid oxide fuel cells: State of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 3165–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggard, P.A. Capturing metastable oxide semiconductors for applications in solar energy conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3160–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Saidi, W.A.; Chorpening, B.; Duan, Y. Applicability of Allen–Heine–Cardona theory on Mo x metal oxides and ABO3 perovskites: Toward high-temperature optoelectronic applications. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 6108–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; El Loubani, M.; Hill, D.; Keum, J.K.; Lee, D. Control of crystallographic orientation in Ruddlesden-Popper for fast oxygen reduction. Catal. Today 2023, 409, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.N.; Lim, J.; Jeon, T.H.; Choi, W. Designing Eco-functional redox conversions integrated in environmental photo (electro) catalysis. ACS EST Eng. 2022, 2, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Steiniger, K.A.; Lambert, T.H. Electrophotocatalysis: Combining light and electricity to catalyze reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12567–12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Luo, D.; Chen, P.; Li, S.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhu, R.; Lu, Z.-H. Universal band alignment rule for perovskite/organic heterojunction interfaces. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysler, M.; Gabel, J.; Lee, T.-L.; Penn, A.; Matthews, B.; Kepaptsoglou, D.; Ramasse, Q.; Paudel, J.; Sah, R.; Grassi, J. Tuning band alignment at a semiconductor-crystalline oxide heterojunction via electrostatic modulation of the interfacial dipole. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Cao, A.; Li, H. Surface coverage and reconstruction analyses bridge the correlation between structure and activity for electrocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 14346–14359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, D.H.; Dekkers, M.; Rijnders, G. Pulsed laser deposition in Twente: From research tool towards industrial deposition. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 47, 034006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Han, W.; Suleiman, A.A.; Han, S.; Miao, N.; Ling, F.C.C. Recent Advances on Pulsed Laser Deposition of Large-Scale Thin Films. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.M. The Influence of various parameters on the ablation and deposition mechanisms in pulsed laser deposition. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 5627–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Fan, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Q.; Ijaz, M. Review on preparation of perovskite solar cells by pulsed laser deposition. Inorganics 2024, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Dewey, J.; Yun, H.; Jeong, J.S.; Mkhoyan, K.A.; Jalan, B. Hybrid molecular beam epitaxy for the growth of stoichiometric BaSnO3. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 2015, 33, 060608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, W.; Usman, M. Applications of molecular beam epitaxy in optoelectronic devices: An overview. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 112002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, W.; Truttmann, T.K.; Jalan, B. A review of molecular-beam epitaxy of wide bandgap complex oxide semiconductors. J. Mater. Res. 2021, 36, 4846–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, G.; Comes, R.B. Advances in complex oxide quantum materials through new approaches to molecular beam epitaxy. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Jalan, B. Atomically precise synthesis of oxides with hybrid molecular beam epitaxy. Device 2025, 3, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvireta, J.; Vega, L.; Viñes, F. Cohesion and coordination effects on transition metal surface energies. Surf. Sci. 2017, 664, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, C. Physics and Chemistry at Oxide Surfaces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, M.; Takahashi, K.; Maeda, T.; Tsuchiya, R.; Shinohara, M.; Ishiyama, O.; Yonezawa, T.; Yoshimoto, M.; Koinuma, H. Atomic Control of the SrTiO3 Crystal Surface. Science 1994, 266, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; Nozoye, H. Surface structure of SrTiO3(100). Surf. Sci. 2003, 542, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, M.R. Nanostructures on the SrTiO3(001) surface studied by STM. Surf. Sci. 2002, 516, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, T.; Shimizu, R.; Iwaya, K.; Shiraki, S.; Hitosugi, T. Negligible Sr segregation on SrTiO3 (001)-(13 × 13)-R33. 7 reconstructed surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 161603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselberth, M.; Van Der Molen, S.; Aarts, J. The surface structure of SrTiO3 at high temperatures under influence of oxygen. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 051609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Feng, J.; Wu, K.; Guo, Q.; Guo, J. Evolution of the surface structures on SrTiO3 (110) tuned by Ti or Sr concentration. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 83, 155453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, L.; Chiaramonti, A.; Rahman, S.; Castell, M. Transition from order to configurational disorder for surface reconstructions on SrTiO3 (111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 226101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniakowski, J.; Finocchi, F.; Noguera, C. Polarity of oxide surfaces and nanostructures. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2007, 71, 016501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudine, N. Polar oxide surfaces. J. Phys. 2000, 12, R367. [Google Scholar]

- Druce, J.; Tellez, H.; Burriel, M.; Sharp, M.; Fawcett, L.; Cook, S.; McPhail, D.; Ishihara, T.; Brongersma, H.; Kilner, J. Surface termination and subsurface restructuring of perovskite-based solid oxide electrode materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3593–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Yang, C.-H.; Ramesh, R.; Jeong, Y.H. Atomically flat single terminated oxide substrate surfaces. Prog. Surf. Sci. 2017, 92, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasker, P. The stability of ionic crystal surfaces. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1979, 12, 4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrelles, X.; Cantele, G.; De Luca, G.; Di Capua, R.; Drnec, J.; Felici, R.; Ninno, D.; Herranz, G.; Salluzzo, M. Electronic and structural reconstructions of the polar (111) SrTiO3 surface. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 205421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, K.J.; Fenning, D.P.; Ming, T.; Hong, W.T.; Lee, D.; Stoerzinger, K.A.; Biegalski, M.D.; Kolpak, A.M.; Shao-Horn, Y. Thickness-dependent photoelectrochemical water splitting on ultrathin LaFeO3 films grown on Nb: SrTiO3. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Lee, Y.-L.; Hong, W.T.; Biegalski, M.D.; Morgan, D.; Shao-Horn, Y. Oxygen surface exchange kinetics and stability of (La,Sr)2CoO4±δ/La1−xSrxMO3−δ (M= Co and Fe) hetero-interfaces at intermediate temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2144–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Song, C.; Seo, M.; Kim, D.; Jung, M.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.-J.; Yu, Y.; Kim, G. Nature of the surface space charge layer on undoped SrTiO3 (001). J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 13094–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, Y.-L.; Grimaud, A.; Hong, W.T.; Biegalski, M.D.; Morgan, D.; Shao-Horn, Y. Enhanced oxygen surface exchange kinetics and stability on epitaxial La0.8Sr0.2CoO3−δ thin films by La0.8Sr0.2MnO3−δ decoration. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 14326–14334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurylev, V.; Su, C.-Y.; Perng, T.-P. Surface reconstruction, oxygen vacancy distribution and photocatalytic activity of hydrogenated titanium oxide thin film. J. Catal. 2015, 330, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herklotz, A.; Lee, D.; Guo, E.-J.; Meyer, T.L.; Petrie, J.R.; Lee, H.N. Strain coupling of oxygen non-stoichiometry in perovskite thin films. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 493001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Shi, F.; Zhu, X.; Yang, W. The roles of oxygen vacancies in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Energy 2020, 73, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Feng, Z.; Charles, N.; Wang, X.R.; Lee, D.; Stoerzinger, K.A.; Muy, S.; Rao, R.R.; Lee, D.; Jacobs, R. Tuning perovskite oxides by strain: Electronic structure, properties, and functions in (electro) catalysis and ferroelectricity. Mater. Today 2019, 31, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, H.; Okada, Y.; Hitosugi, T.; Fukumura, T. Two distinct surface terminations of SrVO3 (001) ultrathin films as an influential factor on metallicity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 113, 171601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Jalan, B. Wide bandgap perovskite oxides with high room-temperature electron mobility. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1900479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, I.-C.; Luo, G.; Lee, J.H.; Chang, S.H.; Moyer, J.; Hong, H.; Bedzyk, M.J.; Zhou, H.; Morgan, D.; Fong, D.D. Polarity-driven oxygen vacancy formation in ultrathin LaNiO3 films on SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2017, 1, 053404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, M.; Franceschi, G.; Lu, Q.; Schmid, M.; Yildiz, B.; Diebold, U. Pushing the detection of cation nonstoichiometry to the limit. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 043802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Ohnishi, T.; Mizoguchi, T.; Shibata, N.; Ikuhara, Y.; Yamamoto, T. Growth of Ruddlesden-Popper type faults in Sr-excess SrTiO3 homoepitaxial thin films by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 173109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, T.; Shibuya, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Lippmaa, M. Defects and transport in complex oxide thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Controlling cation segregation in perovskite-based electrodes for high electro-catalytic activity and durability. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6345–6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravinthkumar, K.; Praveen, E.; Mary, A.J.R.; Mohan, C.R. Investigation on SrTiO3 nanoparticles as a photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic activity and photovoltaic applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 140, 109451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, M.M.; Gogova, D. Theoretical study on electronic, optical, magnetic and photocatalytic properties of codoped SrTiO3 for green energy application. Micro Nanostruct. 2022, 168, 207302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Zong, S.; Tian, L.; Liu, M. Efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production under visible-light irradiation on SrTiO3 without noble metal: Dye-sensitization and earth-abundant cocatalyst modification. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Shi, Z.; Han, M.; He, Q.; Dastan, D.; Liu, Y.; Fan, R. Layered SrTiO3/BaTiO3 composites with significantly enhanced dielectric permittivity and low loss. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 23326–23333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.; Mallick, H.; Sahoo, M.; Pattanaik, A. Enhanced optical and dielectric properties of rare-earth co-doped SrTiO3 ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 13837–13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, S.; Wu, J.; Gao, X.; Li, C.; Du, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, F. High dielectric permittivity and ultralow dielectric loss in Nb-doped SrTiO3 ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 28438–28443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, K. Review on fabrication methods of SrTiO3-based two dimensional conductive interfaces. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 93, 21302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ning, Y.; Tang, C.S.; Dai, L.; Zeng, S.; Han, K.; Zhou, J.; Yang, M.; Guo, Y.; Cai, C. LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface: 20 years and beyond. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2024, 10, 2300730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Hu, K.; Song, D.; Meng, K.; Xu, X.; Ge, B.; Tian, W.; Jiang, Y. Tuning the magnetic anisotropy of La0.67Sr0.33MnO3 by CaTiO3 spacer layer on the platform of SrTiO3. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 554, 169299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Yang, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Yeom, M.J.; Lee, G.; Shin, H.; Bae, S.-H.; Ahn, J.-H.; Kim, S. Heterogeneous integration of high-k complex-oxide gate dielectrics on wide band-gap high-electron-mobility transistors. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.; Yu, M.; Seo, J.; Yang, D.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-W.; Irvin, P.; Oh, S.H.; Levy, J.; Eom, C.-B. Electronically reconfigurable complex oxide heterostructure freestanding membranes. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, D.; Mo, S.H.; Ryou, S.H.; Lee, J.-W.; Eom, K.; Rhim, J.-W.; Lee, H. Low-frequency noise behaviors of quasi-two-dimensional electron systems based on complex oxide heterostructures. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2024, 59, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, M.; Teker, A.; Mannhart, J.; Braun, W. Independence of surface morphology and reconstruction during the thermal preparation of perovskite oxide surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 111601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Du, H.; van der Torren, A.J.; Aarts, J.; Jia, C.-L.; Dittmann, R. Formation mechanism of Ruddlesden-Popper-type antiphase boundaries during the kinetically limited growth of Sr rich SrTiO3 thin films. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Yang, F.; Liang, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Gu, L.; Zhang, J. δ-Doping of oxygen vacancies dictated by thermodynamics in epitaxial SrTiO3 films. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Luo, B.; Bian, S.; Yue, Z. Thermally stimulated relaxation and behaviors of oxygen vacancies in SrTiO3 single crystals with (100),(110) and (111) orientations. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 046305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Loon, A.; Subramanian, A.; Gerhold, S.; McDermott, E.; Enterkin, J.; Hieckel, M.; Russell, B.; Green, R.; Moewes, A. Transition from reconstruction toward thin film on the (110) surface of strontium titanate. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 2407–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, M.; Franceschi, G.; Schmid, M.; Diebold, U. Epitaxial growth of complex oxide films: Role of surface reconstructions. Phys. Rev. Res. 2019, 1, 033059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.K.; Wang, S.; Castell, M.R.; Fong, D.D.; Marks, L.D. Single-layer TiOx reconstructions on SrTiO3 (111): (√7 × √7)R19.1°, (√13 × √13)R13.9°, and related structures. Surf. Sci. 2018, 675, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Min, T.; Seo, J.; Ryu, S.; Lee, H.; Wang, Z.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Eom, C.B.; Oh, S.H. Electronic and Structural Transitions of LaAlO3/SrTiO3 Heterostructure Driven by Polar Field-Assisted Oxygen Vacancy Formation at the Surface. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.N.; Mun, J.; Kim, Y.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, B.; Das, S.; Wang, L.; Kim, M.; Lippmaa, M. Experimental realization of atomically flat and AlO2-terminated LaAlO3 (001) substrate surfaces. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 023801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Liang, S.; Liu, L.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, R. Surface termination and stoichiometry of LaAlO3 (001) surface studied by HRTEM. Micron 2020, 137, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P.; Steele, E.; Gulec, A.; Marks, L. Al rich (111) and (110) surfaces of LaAlO3. Surf. Sci. 2018, 677, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienzle, D.; Koirala, P.; Marks, L. Lanthanum aluminate (110) 3 × 1 surface reconstruction. Surf. Sci. 2015, 633, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Campbell, N.; Lee, J.; Asel, T.; Paudel, T.; Zhou, H.; Lee, J.; Noesges, B.; Seo, J.; Park, B. Direct observation of a two-dimensional hole gas at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtomo, A.; Hwang, H. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 2004, 427, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, A.; Sohail, M.; Altaf, M.; Nafady, A.; Sher, M.; Wahab, M.A. Enhanced electrocatalytic activity of amorphized LaCoO3 for oxygen evolution reaction. Chem.-Asian J. 2024, 19, e202300870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Mostafaei, J.; Griesser, C.; Bekheet, M.F.; Delibas, N.; Penner, S.; Asghari, E.; Coruh, A.; Niaei, A. LaCoO3-BaCoO3 porous composites as efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 144829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwaiz, S.; Jennings, J.R.; Harunsani, M.H.; Khan, M.M. Recent advances in LaCoO3-based perovskite nanostructures for electrocatalytic and photocatalytic applications. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2025, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Wang, T.; Ran, J.; Jiang, S.; Gao, X.; Gao, D. Optimized conductivity and spin states in N-doped LaCoO3 for oxygen electrocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 2447–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingavale, S.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Enoch, C.M.; Pornrungroj, C.; Rittiruam, M.; Praserthdam, S.; Somwangthanaroj, A.; Nootong, K.; Pornprasertsuk, R.; Kheawhom, S. Strategic design and insights into lanthanum and strontium perovskite oxides for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Small 2024, 20, 2308443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.W.; Chae, M.S.; Jeong, I.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.J.; Jung, C.; Lee, C.-W.; Hong, S.-T. An efficient and robust lanthanum strontium cobalt ferrite catalyst as a bifunctional oxygen electrode for reversible solid oxide cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 5507–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, B.; Xiong, H.; Lin, C.; Fang, L.; Fu, J.; Deng, D.; Fan, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.-H. Cobalt-based perovskite electrodes for solid oxide electrolysis cells. Inorganics 2022, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Jung, W.; Ahn, S.-J.; Lee, D. Controlling the oxygen electrocatalysis on perovskite and layered oxide thin films for solid oxide fuel cell cathodes. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Yacoby, Y.; Hong, W.T.; Zhou, H.; Biegalski, M.D.; Christen, H.M.; Shao-Horn, Y. Revealing the atomic structure and strontium distribution in nanometer-thick La0.8Sr0.2CoO3−δ grown on (001)-oriented SrTiO3. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Yang, T.; Lee, D.; Lee, H.N.; Crumlin, E.J.; Huang, K. Temporal and thermal evolutions of surface Sr-segregation in pristine and atomic layer deposition modified La0.6Sr0.4CoO3−δ epitaxial films. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 24378–24388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Oldman, R.; Cora, F.; Catlow, C.; French, S.; Axon, S. A computational modelling study of oxygen vacancies at LaCoO3 perovskite surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 5207–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, G.M.; Téllez, H.; Druce, J.; Limbeck, A.; Ishihara, T.; Kilner, J.; Fleig, J. Surface chemistry of La0.6Sr0.4CoO3−δ thin films and its impact on the oxygen surface exchange resistance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 22759–22769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, L.; Guo, Q.; Cao, Y.; Kareev, M.; Chakhalian, J.; Guo, J. Reconstruction-stabilized epitaxy of LaCoO3/SrTiO3 (111) heterostructures by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 031603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halilov, S.; Gorelov, E.; Izquierdo, M.; Yaroslavtsev, A.; Aristov, V.; Moras, P.; Sheverdyaeva, P.; Mahatha, S.; Roth, F.; Lichtenstein, A. Surface, final state, and spin effects in the valence-band photoemission spectra of LaCoO3 (001). Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 205144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumlin, E.J.; Mutoro, E.; Liu, Z.; Grass, M.E.; Biegalski, M.D.; Lee, Y.-L.; Morgan, D.; Christen, H.M.; Bluhm, H.; Shao-Horn, Y. Surface strontium enrichment on highly active perovskites for oxygen electrocatalysis in solid oxide fuel cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6081–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, A.; Kumar, A.; Ponraj, J.; Mansour, S.A.; Tarlochan, F. Enhancing the electrocatalytic properties of LaMnO3 by tuning surface oxygen deficiency through salt assisted combustion synthesis. Catal. Today 2021, 375, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Zheng, R.; He, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, B.; Li, R.; Xu, H.; Wen, X.; Zeng, T.; Shu, C. A-site cationic defects induced electronic structure regulation of LaMnO3 perovskite boosts oxygen electrode reactions in aprotic lithium–oxygen batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 43, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Kang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Selishchev, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G. Achieving efficient toluene mineralization over ordered porous LaMnO3 catalyst: The synergistic effect of high valence manganese and surface lattice oxygen. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 615, 156248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao-Horn, Y. Thickness dependence of oxygen reduction reaction kinetics on strontium-substituted lanthanum manganese perovskite thin-film microelectrodes. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2009, 12, B82. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, F.; Yildiz, B. Polar or not polar? The interplay between reconstruction, Sr enrichment, and reduction at the La0.75Sr0.25MnO3 (001) surface. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 015801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Guo, H.; Saghayezhian, M.; Liao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Plummer, E.; Zhang, J. Surface and interface properties of La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films on SrTiO3 (001). Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 044407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, G.; Schmid, M.; Diebold, U.; Riva, M. Atomically resolved surface phases of La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 (110) thin films. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 22947–22961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, R.K.; Dixit, H.; Tselev, A.; Qiao, L.; Meyer, T.L.; Cooper, V.R.; Baddorf, A.P.; Lee, H.N.; Ganesh, P.; Kalinin, S.V. Surface reconstructions and modified surface states in La1−xCaxMnO3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Kuznetsova, T.; Miao, L.; Pogrebnyakov, A.; Alem, N.; Engel-Herbert, R. Self-regulated growth of [111]-oriented perovskite oxide films using hybrid molecular beam epitaxy. APL Mater. 2021, 9, 021114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Sung, H.-J.; Gake, T.; Oba, F. Chemical trends of surface reconstruction and band positions of nonmetallic perovskite oxides from first principles. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Yang, K. First-Principles Study of Dominant Surface Terminations on BaSnO3 (001) Surface: Implications for Precise Control of Semiconductor Thin Films. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 11995–12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh, A.; El Khaloufi, O.; Rath, M.; Luders, U.; Fouchet, A.; Cardin, J.; Labbé, C.; Prellier, W.; David, A. Tuning the transparency window of SrVO3 transparent conducting oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 47854–47865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchela, A.V.; Wei, M.; Cho, H.J.; Ohta, H. Optoelectronic properties of transparent oxide semiconductor ASnO3 (A = Ba, Sr, and Ca) epitaxial films and thin film transistors. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 020803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, G.; Zhou, L.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Shen, Y.; Xu, G.; Luo, Y.; Wang, N. Oxide perovskite BaSnO3: A promising high-temperature thermoelectric material for transparent conducting oxides. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 9756–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngabonziza, P.; Nono Tchiomo, A.P. Epitaxial films and devices of transparent conducting oxides: La:BaSnO3. APL Mater. 2024, 12, 120601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Shiau, S.-Y.; Chang, T.-R.; Chang, G.; Kobayashi, M.; Shimizu, R.; Jeng, H.-T.; Shiraki, S.; Kumigashira, H.; Bansil, A. Quasiparticle interference on cubic perovskite oxide surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 086801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Meng, M.; Saghayezhian, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Guo, H.; Zhu, Y.; Plummer, E.; Zhang, J. Role of disorder and correlations in the metal-insulator transition in ultrathin SrVO3 films. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 155114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Mizoguchi, T.; Martin, L.W.; Bradley, J.P.; Ikeno, H.; Ramesh, R.; Tanaka, I.; Browning, N. Atomic and electronic structures of the SrVO3-LaAlO3 interface. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 046104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, S.; Shoham, L.; Baskin, M.; Weinfeld, K.; Piamonteze, C.; Stoerzinger, K.A.; Kornblum, L. Effect of capping layers on the near-surface region of SrVO3 films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 013208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, S.; Rödel, T.C.; Fortuna, F.; Frantzeskakis, E.; Le Fèvre, P.; Bertran, F.; Kobayashi, M.; Yukawa, R.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Kitamura, M. Hubbard band versus oxygen vacancy states in the correlated electron metal SrVO3. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 241110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahlek, M.; Zhang, L.; Eaton, C.; Zhang, H.-T.; Engel-Herbert, R. Accessing a growth window for SrVO3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 143108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, C.; Moyer, J.A.; Alipour, H.M.; Grimley, E.D.; Brahlek, M.; LeBeau, J.M.; Engel-Herbert, R. Growth of SrVO3 thin films by hybrid molecular beam epitaxy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2015, 33, 061504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-J.; Lee, H.; Ko, K.-T.; Kang, J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, T.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, K.H. Realization of an atomically flat BaSnO3 (001) substrate with SnO2 termination. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 231604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Hong, S.; Kim, B.; Kim, D.; Jung, J.K.; Sohn, B.; Noh, T.W.; Char, K.; Kim, C. R45° surface reconstruction and electronic structure of BaSnO3 film. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, H.; Chen, Z.; Lochocki, E.; Seidner, H.A.; Verma, A.; Tanen, N.; Park, J.; Uchida, M.; Shang, S.; Zhou, B.-C. Adsorption-controlled growth of La-doped BaSnO3 by molecular-beam epitaxy. Apl. Mater. 2017, 5, 116107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Paik, H.; Chen, Z.; Muller, D.A.; Schlom, D.G. Epitaxial integration of high-mobility La-doped BaSnO3 thin films with silicon. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 022520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Jacobs, R.; Jee, Y.; Seo, A.; Sohn, C.; Ievlev, A.V.; Ovchinnikova, O.S.; Huang, K.; Morgan, D.; Lee, H.N. Stretching epitaxial La0.6Sr0.4CoO3−δ for fast oxygen reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 25651–25658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kuru, Y.; Han, J.W.; Chen, Y.; Yildiz, B. Surface electronic structure transitions at high temperature on perovskite oxides: The case of strained La0.8Sr0.2CoO3 thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17696–17704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayeshiba, T.; Morgan, D. Strain effects on oxygen migration in perovskites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 2715–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, U.; Pfenninger, R.; Selbach, S.M.; Grande, T.; Spaldin, N.A. Strain-controlled oxygen vacancy formation and ordering in CaMnO3. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2013, 88, 054111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, F.; Meng, S.; Zhang, J.; Plummer, E.; Diebold, U.; Guo, J. Strain-induced defect superstructure on the SrTiO3 (110) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 056101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Lapano, J.; Brahlek, M.; Lei, S.; Kabius, B.; Gopalan, V.; Engel-Herbert, R. Continuously Tuning Epitaxial Strains by Thermal Mismatch. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]