Abstract

In this article, electrodeposited Ni-Al2O3 coatings were fabricated on the surface of a cylinder liner to enhance its corrosion resistance. The effect of current density on the surface morphology, phase structure, and corrosion resistance of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings was investigated using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) instrument, and electrochemical workstation, respectively. The observed results show that a dense, flat morphology emerged on the surface of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2. Furthermore, among three Ni-Al2O3 coatings, the Al content of the one prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 was the highest, with a value of 5.4 wt.%. XRD patterns demonstrated that the average nickel grain size of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 was only 251.6 nm, which was obviously smaller than those deposited under current densities of 2.5 A/dm2 and 4.5 A/dm2. Meanwhile, the adhesion strength of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 was the largest, with a value of 40.9 N. Polarization curves indicated the corrosion potential of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 was the highest, with a value of −0.42 V, while the corrosion current density of the coatings fabricated under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 was the lowest, with a value of 2.17 × 10−7 A/cm2. In addition, the corrosive mass loss of Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured at 3.5 A/dm2 was only 2.8 mg, illustrating excellent corrosion resistance. This study could enhance the service life and corrosion resistance of cylinder liners in internal combustion engines.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the cylinder liner has become one of the key components in the internal combustion engine, and its structure and performance have a significant influence on the comprehensive performance of the engine system [1,2,3,4,5]. However, it has been found that, for a cylinder liner made from cast iron material within an internal combustion engine operated at high temperature and high pressure, the surface is prone to damage or corrosion [6].

Nickel-based coatings (such as Ni-Al2O3, Ni-SiC, Ni-TiN, and Ni-TiC coatings), because of their excellent chemical, mechanical, and physical performances, are becoming a hot topic in the improvement of the abrasion resistance and anti-corrosion performance of cylinder liners [7,8,9,10]. The preparation methods for obtaining nickel-based coatings include laser cladding [11], chemical plating [12], and pulse electrodeposition [13]. In comparison to other fabrication techniques, pulse electrodeposition has obvious advantages in terms of operation, cost, and efficiency [14,15,16]. For instance, Jegan et al. [17] conducted a study of Ni-Al2O3 coatings on the surface of a cylinder liner made from cast iron using the electrodeposition approach. They applied Taguchi’s optimization method for enhancing the highest microhardness value of Ni-Al2O3 coatings to 1050 Hv. Natarajan et al. [18] manufactured Ni-SiC coatings utilizing the electrodeposition method. They found significant performance variation of the Ni-SiC coatings obtained at different current densities, duty cycles, and frequencies based on variance analysis. Li et al. [19] fabricated electrodeposited Ni-Cr-MoS2 coatings on a cylinder liner surface. They proposed that the abrasion resistance of Ni-Cr-MoS2 coatings was superior to Ni-Cr coatings. These reports demonstrated that the electrodeposited Ni-based coatings could obviously improve the abrasion and corrosion resistance of cylinder liners.

Among these Ni-based coatings, Ni-Al2O3 coatings, because of high temperature stability, excellent anti-corrosion ability, and outstanding abrasion resistance, have received more and more attention from international researchers [20,21,22]. For example, Jiang et al. [23] investigated the effect of hexadecylpyridinium bromide (HBP) on the microstructure and properties of Ni-Al2O3 coatings. They demonstrated that the Al2O3 content of Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared at HBP was higher in comparison to those obtained without HBP. Kucharska et al. [24] explored how different stirring conditions impacted the anti-wear ability of Ni-Al2O3 coatings. They revealed that the largest hardness value emerged in the Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured with the mechanical stirring method. These findings demonstrated the process parameters had a significant influence on the microstructure and properties of electrodeposited Ni-Al2O3 coatings. At present, many studies on the fabrication of electrodeposited Ni-Al2O3 coatings have been reported. However, the research on the current density’s influence on the corrosion resistance of Ni-Al2O3 coatings applied on the surface of cylinder liners from internal combustion engines is low. In this paper, the influence of current density on the surface morphology, phase structure, and corrosion resistance of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated using the pulse electrodeposition approach was investigated and the results were explored.

2. Experiment

2.1. Preparation

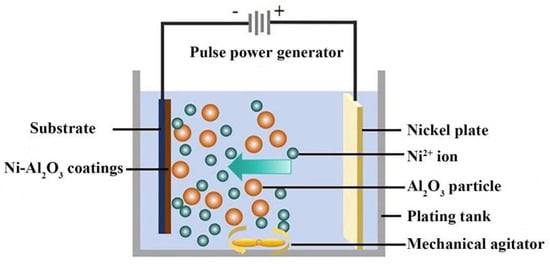

Figure 1 reveals the facility diagram of the obtained Ni-Al2O3 coatings using the electrodeposition technique. The plating parameters and components of the electrolyte are displayed in Table 1. The electrodeposition facility included a pulse power generator, substrate, plating tank, nickel plate, and mechanical agitator. Furthermore, the nickel plate acted as an anode and the cast iron sheet was employed as a cathode. The pH value of the composite electrolyte was adjusted to 4.2 utilizing NaOH solution and hydrochloric acid. Figure 2 shows a TEM image of the Al2O3 nanoparticles. The average dimension of the Al2O3 nanoparticles with 99.97% purity was approximately 20 nm.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for manufacturing electrodeposited Ni-Al2O3 coatings.

Table 1.

Compositions of electrolyte and plating parameters for obtaining Ni-Al2O3 coatings.

Figure 2.

TEM image of nano-sized Al2O3 particles.

Before the pulse electrodeposition was conducted, the cathode surface was orderly polished utilizing sandpapers of 600, 1000, and 1500 grits. A rust remover and degreaser were used to remove the rust and oil on the surface of the cathode. Furthermore, the electrolyte with Al2O3 nanoparticles was treated using an ultrasonic cleaner for 20 min.

2.2. Characterization

The surface morphology and element content of Ni-Al2O3 coatings were characterized employing a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S3400, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) allocated with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). The phase structure of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings was detected using an X-ray diffraction instrument (XRD, D5000, Siemens, Munich, Germany). The testing conditions were as follows: Cu target Kα acted as X-ray source; the scanning range and scanning speed were 30–100° and 0.02°/s, respectively. The grain size (D) of crystal plane (111) in the Ni-Al2O3 coatings was calculated using Equation (1). Furthermore, to enhance the accuracy of the results, the value was recorded three times and averaged.

where λ represents the wavelength of the X-ray, β represents the half-width of diffraction peaks, and θ expresses the Bragg’s angle, respectively.

D = 0.89λ/βcosθ,

The adhesion strength of Ni-TiN coatings was tested utilizing a TC-A10-type adhesion strength measurement facility under the following conditions: 30 s static pressure, 100 N applied force, and 5 mm scratch length.

The polarization curve measurement of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings was conducted utilizing a CS350-style electrochemical workstation in the 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at room temperature. During electrochemical measurement, the exposed area of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings acting as a working electrode was 1 cm2. Furthermore, the saturated calomel electrode and platinum electrode were employed as the reference electrode (RE) and counter electrode (CE), respectively. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (ESI) of Ni-Al2O3 coatings was performed over a frequency range from 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz with an alternating current perturbation amplitude of 10 mV at the open-circuit potential. The x-axis represents the real part of impedance (Z′), and the y-axis represents the negative imaginary part (−Z″). The BW-WY60B-type salt spray test chamber was utilized to measure the corrosive mass loss under the conditions of room temperature and 7 days. The corrosive mass loss (W) of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings was tested and calculated based on Equation (2).

W = W0 − W1

Specifically, the W0 is the initial mass loss of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings, whereas W1 is the residual mass loss of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings following the corrosion testing.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM Image Exploration

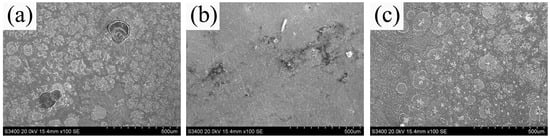

The surface morphology of Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured at various current densities is presented in Figure 3. It can be seen that the surface morphology of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings is influenced by the variation in the current density. The observed SEM images exhibited an uneven morphology and obvious protrusions with the largest-sized grains on the surface of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated under a current density of 2.5 A/dm2. By contrast, a relatively flat morphology with the smallest-sized grains appeared on the surface of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2. However, when the current density rose to 4.5 A/dm2, the uneven morphology with relatively large-sized grains and relatively obvious protrusions on the surface of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured under a current density of 4.5 A/cm2 [25].

Figure 3.

SEM graphs of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

This could be because the increase in current density caused an increase in the electric field force, leading to increased growth speed of nickel grain and distribution variation of the Al2O3 nanoparticles. Akhtar et al. [26] proposed that the growth speed of nickel grain at a suitable current density could significantly influence the surface morphology of Ni-based coatings. Furthermore, the appropriate current density contributed to the uniform distribution of Al2O3 nanoparticles embedded in the nickel matrix. The result was similar to the conclusion reported by Li et al. [27]. As a result, the Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured at 3.5 A/dm2 had a more even surface morphology and less protrusion in comparison to those obtained at 2.5 A/dm2 and 4.5 A/dm2.

3.2. Al Content Analysis

Figure 4 shows the Al content of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities. The low current density caused an increase in the speed of Ni2+ ions with Al2O3 nanoparticles, causing them to be crushed on the cathode surface, which led to the Al content of Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 2.5 A/dm2 to be the lowest, with a value of 3.7 wt.%. By contrast, the appropriate current density contributed to the co-deposition of Ni2+ ions coupled with Al2O3 nanoparticles, resulting in the Al content existing in the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 to be the highest, with a value of 5.4 wt.%. However, when the current density increased to 4.5 A/dm2, the concentration polarization and hydrogen evolution reaction aggravated and caused a low co-deposition speed of Ni2+ ions coupled with Al2O3 nanoparticles, leading to the Al content of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at 4.5 A/dm2 decreasing to 4.2 wt.%. This conclusion was consistent with the findings reported by Guo et al. [28].

Figure 4.

Al content of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

3.3. XRD Investigation

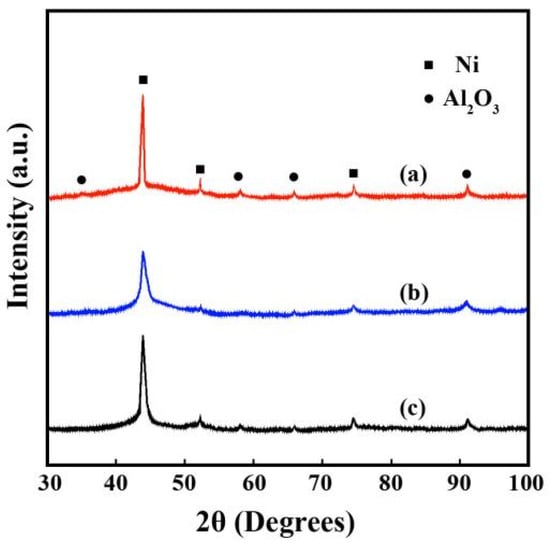

Figure 5 reveals the XRD patterns of the Ni-Al2O3 composites produced at different current densities. The average nickel grain size of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings are listed in Table 2. Three diffraction peaks of nickel phase corresponded to crystal grains of (111), (200), and (220), demonstrating their face-centered cubic (FCC) structure [29]. Furthermore, some diffraction peaks of Al2O3 phase were observed in the Ni-Al2O3 composites, demonstrating the existence of Al2O3 nanoparticles. According to Equation (1), the average nickel grain sizes of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under current densities of 2.5 A/dm2, 3.5 A/dm2, and 4.5 A/dm2 were 513.2 nm, 251.6 nm, and 484.7 nm, respectively.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

Table 2.

Average size of nickel grain in the Ni-Al2O3 coatings.

It could be clearly seen that the diffraction peaks’ intensity of nickel grain was broader initially and then narrowed, with the current density rising from 2.5 A/dm2 to 4.5 A/dm2. The results showed that the average sizes of nickel grain in the Ni-based composites were significantly influenced by the appropriate current density (such as 3.5 A/dm2), which has been indicated by the findings of Alizadeh et al. [30].

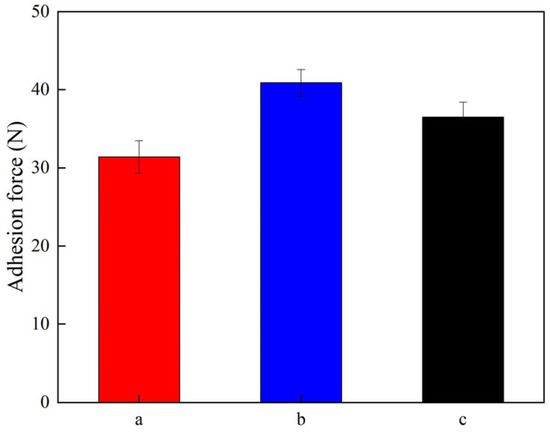

3.4. Adhesion Strength Measurement

Figure 6 exhibits the adhesion strength of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings obtained from various current densities. Specifically, the adhesion strength of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under current densities of 2.5 A/dm2, 3.5 A/dm2, and 4.5 A/dm2 was determined to be 31.4 N, 40.9 N, and 36.5 N, respectively. This phenomenon of varied adhesion strength can be illustrated as follows: (1) The appropriate current density accelerated the co-deposition speed of Ni2+ ions coupled with Al2O3 nanoparticles, resulting in the uniform distribution of reinforcing phase and effective grain refinement in the Ni-Al2O3 coatings [31]. Moreover, the appropriate current density could mitigate concentration polarization and suppress hydrogen evolution reaction, which was beneficial in forming an even morphology and few protrusions. This could decrease the internal stress accumulated in the coatings and increase inter-facial bonding between substrate and coatings, thereby enhancing the adhesion strength of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings [32]. By comparison, the low current intensity caused the agglomeration of Al2O3 nanoparticles, which compromised the grain refinement strengthening effect and decreased the adhesion strength of coatings. Conversely, the high current density exacerbated the concentration polarization and hydrogen evolution reaction, leading to the uneven morphology and protrusions of aggravated coatings. This increased the internal stress of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings and reduced their adhesion strength.

Figure 6.

Adhesion strength of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

3.5. Corrosion Resistance Testing

Figure 7 indicates the polarization curves of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings obtained from various current densities. The specific values for the corrosion potential (E) and corrosion current density (I) of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings are displayed in Table 3. When the current density rose from 2.5 A/dm2 to 3.5 A/dm2, the E of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings shifted from −0.58 V to −0.42 V, while the I of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings reduced from 6.92 × 10−7 A/cm2 to 2.17 × 10−7 A/cm2. After the current density rose from 3.5 A/dm2 to 4.5 A/dm2, the E of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings moved from −0.42 V to −0.51 V, while the I of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings increased from 2.17 × 10−7 A/cm2 to 4.29 × 10−7 A/cm2. Li et al. [33] and Xia et al. [34] found that the corrosion resistance of nickel-based coatings with a low I and high E was outstanding. The excellent corrosion resistance of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 contributed to numerous Al2O3 nanoparticles (5.38 wt.%) being uniformly distributed in the Ni-Al2O3 coatings. Therefore, the corrosion resistance of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings produced under a current density of 3.5 A/dm2 was better than those prepared under current densities of 2.5 A/dm2 and 4.5 A/dm2.

Figure 7.

Polarization curves of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

Table 3.

Specific data from polarization curves of Ni-Al2O3 coatings.

Figure 8 depicts the Nyquist plots of the Ni-Al2O3 composites produced at various current densities. The impedance arc radius of the Ni-Al2O3 prepared at 2.5 A/dm2 was the smallest, indicating the worst corrosion resistance. However, the impedance arc radius of the Ni-Al2O3 prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 was the largest, indicating the best anti-corrosion performance. This conclusion about impedance arc radius of nickel-based composites fabricated using electrodeposition approach has been proposed in the research of Li et al. [35].

Figure 8.

Nyquist plots of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

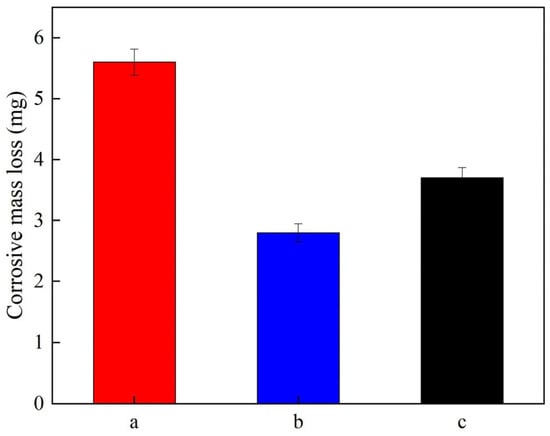

Figure 9 illustrates the corrosive mass loss of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured at different current densities. It can be seen that the corrosion mass loss values W of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings deposited under current densities of 2.5 A/dm2, 3.5 A/dm2, and 4.5 A/dm2 were 5.6 mg, 2.8 mg, and 3.7 mg, respectively. The results are attributed to the even surface morphology of coatings with a high content of reinforced phase, which served as an effective barrier to inhibit the permeation of NaCl solution and enhance the corrosion resistance of the coatings. The results were similar to those of Ali et al. [36] and Liu et al. [37].

Figure 9.

Corrosive mass loss of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

Figure 10 demonstrates the corrosive surface morphology of Ni-Al2O3 coatings obtained from different current densities. Analysis of the corrosion experiment showed that the surface of Ni-Al2O3 coatings manufactured at 2.5 A/dm2 possessed numerous corrosion products and large corrosion pores were observed. By contrast, the surface of Ni-Al2O3 prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 presented few corrosion products and small corrosion pores after the corrosion experiment. However, the increasing corrosion products and expanded corrosion pores existed on the surface of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at 4.5 A/dm2, confirming that the corrosion resistance of the coatings decreased. The results demonstrated that the current density contributed to a refined grain size and the formation of a compact, smooth microstructure, leading to a contact area between the corrosion liquid and the coatings [38]. Furthermore, Safavi et al. [39] and Wang et al. [40] found that the high content of nanoparticles uniformly immersed in the coating could significantly improve the corrosion resistance of Ni-Al2O3 coatings.

Figure 10.

Corrosive surface morphology of Ni-Al2O3 coatings fabricated at various current densities: (a) 2.5 A/dm2; (b) 3.5 A/dm2; (c) 4.5 A/dm2.

4. Conclusions

(1) The SEM images revealed that the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 had an even surface morphology with few protrusions. Furthermore, the EDS results showed that the Al content of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 was lower than that obtained at 2.5 A/dm2 and 4.5 A/dm2.

(2) The XRD patterns revealed that the grain size of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 was the lowest, with a value of 251.6 nm, in comparison to those manufactured at 2.5 A/dm2 and 4.5 A/dm2. The adhesion strength of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings produced at 2.5 A/dm2, 3.5 A/dm2, and 4.5 A/dm2 was 31.4 N, 40.9 N, and 36.5 N, respectively.

(3) The corrosion potential of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings prepared at 3.5 A/dm2 was the highest, with a value of −0.42 V, while the corrosion current density of those fabricated at 4.5 A/dm2 was the smallest, with a value of 2.17 × 10−7 A/cm2. In addition, the corrosive mass loss of the Ni-Al2O3 coatings obtained at 3.5 A/dm2 was the lowest, with a value of 2.8 mg, demonstrating the corrosion resistance was excellent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and S.Q.; methodology, G.C. and H.M.; formal analysis, F.Q. and M.C.; investigation, F.Q. and M.C.; resources, C.L. and S.Q.; data curation, L.Q. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Q. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, H.G. and C.L.; supervision, G.C. and H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sanming University Research Start-up Fund for High-level Talents (Grant No.: 25YG06), Educational Research Project for Middle-aged and Yong Teachers in Fujian Province (Grant No.: JAT241130), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No.: 2025J011051), and Science and Technology Plan Project of Fujian Province (Grant No.: 2023T3062).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yong Wang was employed by the company ZYNP Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhen, X.D.; Liu, Z.B. The effect of methanol production and application in internal combustion engines on emissions in the context of carbon neutrality: A review. Fuel 2022, 320, 123902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, J.; Wu, C.H.; Fu, J.Q.; Liu, J.P.; Duan, X.B. The application prospect and challenge of the alternative methanol fuel in the internal combustion engine. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goral, M.; Kubaszek, T.; Grabon, W.A.; Grochalski, K.; Drajewicz, M. The Concept of WC-CrC-Ni Plasma-Sprayed Coating with the Addition of YSZ Nanopowder for Cylinder Liner Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaisundaram, V.S.; Balambica, V.; Kumar, D.S.; Nithish, S.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Shanmugam, M.; Likassa, D.M. Optimization of Dual Coating Using Electroless Ni-P-Nano-TiO2 and Plasma Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia on Piston Crown and Cylinder Liner in CI Engine. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 49344926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tat, M.E.; Kaya, E. Tribomechanical characterization of ceramic reinforced composite coatings for modification of cylinder liner of heavy-duty diesel engines. Int. J. Engine Res. 2025, 26, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.X.; Lu, Y.J.; Luo, H.B.; Li, J.; Hou, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.F. Wear assessment model for cylinder liner of internal combustion engine under fuzzy uncertainty. Mech. Ind. 2021, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Nour, J.; Nasirpouri, F. Exploiting magnetic sediment co-electrodeposition mechanism in Ni-Al2O3 nanocomposite coatings. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 907, 116052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.J.; Han, K.; Jin, H.; Li, X.P.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, S.G.; Dong, T.C.; Cai, B.P.; Cheng, W.H. Preparation of Ni-SiC nano-composite coating by rotating magnetic field-assisted electrodeposition. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 57, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.Y.; He, H.X.; Xia, F.F.; Cao, M.Y. Effect of Pulse Electrodeposition Mode on Microstructures and Properties of Ni-TiN Composite Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Sun, W.C.; Zhang, Y.G.; Liu, X.J.; Dong, Y.R.; Zi, J.Y.; Xiao, Y. Effect of TiC Particles Concentration on Microstructure and Properties of Ni-TiC Composite Coatings. Mater. Res.-Ibero-Am. J. Mater. 2019, 22, e20190530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.K.; Wang, A.H.; Wu, X.H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.X. Wear resistance of diode laser-clad Ni/WC composite coatings at different temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 304, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melinescu, A.; Volceanov, E.; Eftimie, M.; Volceanov, A.; Popescu, L.; Trusca, R. Effect of low carbon steel surface preparation on Ni-P and Ni-P-Al2O3 electroless coatings characteristics. Rev. Romana Mater.-Rom. J. Mater. 2021, 51, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.S.; Gu, C.Q.; Wang, J.L.; Xi, X.H.; Qin, Z.B. Characterization and corrosion behavior of Ni-Cr coatings by using pulse current electrodeposition. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2023, 70, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhao, M.T.; Zhang, W.H. Preparation of Ni-TiO2 Composite Coatings on Q390E Steel by Pulse Electrodeposition and their Photocatalytic and Corrosion Resistance Properties. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.K.; Urumarudappa, S.K.J.; Kamal, S.; Widiadita, Y.; Mahamud, A.; Saito, T.I.; Bovornratanaraks, T. Effect of Pulse Electrodeposition Parameters on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Ni-W/B Nanocomposite Coatings. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.C.; Zhu, H.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y. Electrodeposition of Ni-Mo alloys and composite coatings: A review and future directions. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 119, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegan, A. Pulse Eletrodeposition of Ni/nano-Al2O3 Composite Coatings on Cast Iron Cylinder Liner. Mater. Res.-Ibero-Am. J. Mater. 2018, 21, e20180060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, P.; Sakthivel, P.; Vijayan, V.; Chellammuthu, K. Characterization of Pulse Electrodeposited Ni-SiC Nanocomposite Coating on Four Stroke Internal Combustion Engine Cast Iron Cylinder Liner. Silicon 2024, 16, 6193–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, X.G.; Shan, Y.C.; Shen, Y.; Xu, J.J. The effect of MoS2 concentration on the thickness and tribology performance of electro-codeposited Ni-Cr-MoS2 coatings. Wear 2024, 552, 205457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, H.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Karimzadeh, A.; Rouhaghdam, A.S. Corrosion and wear behaviour of multilayer pulse electrodeposited Ni-Al2O3 nanocomposite coatings assisted with ultrasound. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2017, 39, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezgui, I.; Belloufi, A.; Abdelkrim, M. Investigating corrosion resistance in Ni-Al2O3 composite coatings: A fuzzy logic-based predictive study. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 4363–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehgahi, S.; Amini, R.; Alizadeh, M. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of Ni-Al2O3-SiC nanocomposite coatings produced by electrodeposition technique. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 692, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.W.; Yang, L.; Pang, J.N.; Lin, H.; Wang, Z.Q. Electrodeposition of Ni-Al2O3 composite coatings with combined addition of SDS and HPB surfactants. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 286, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, B.; Poplawski, K.; Jezierska, E.; Oleszak, D.; Sobiecki, J.R. Influence of stirring conditions on Ni/Al2O3 nanocomposite coatings. Surf. Eng. 2016, 32, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, S.M. Synthesis and characterization of Ni-Si3N4 nanocomposite coatings fabricated by pulse electrodeposition. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2019, 42, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, K.; Khalid, H.; Ul Haq, I.; Zubair, N.; Khan, Z.U.; Hussain, A. Tribological Properties of Electrodeposited Ni-Co3O4 Nanocomposite Coating on Steel Substrate. J. Tribol.-Trans. ASME 2017, 139, 061302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.S.; Mei, T.Y.; Chu, H.Q.; Wang, J.J.; Du, S.S.; Miao, Y.C.; Zhang, W.W. Ultrasonic-assisted electrodeposition of Ni/diamond composite coatings and its structure and electrochemical properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 73, 105475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.J.; Yang, Z.G.; Deng, S.H.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Effect of Pulse Electrical Parameters on the Microstructure and Performance of Ni-TiN Nanocoatings Prepared by Pulse Electrodeposition Technique. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2022, 75, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhao, Y.P.; Jiang, J.; Wang, S.K.; Shan, W. Improvement of Microstructure and Wear Resistance of the Ni-La2O3 Nanocomposite Coatings by Jet-Electrodeposition. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 3429–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Cheshmpish, A. Electrodeposition of Ni-Mo/Al2O3 nano-composite coatings at various deposition current densities. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 466, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Ji, R.J.; Dong, T.C.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, F.; Ma, C.; Liu, S.G. Fabrication and characterization of WC particles reinforced Ni-Fe composite coating by jet electrodeposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 421, 127376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.Y.; Sun, C.; Sun, J.B.; Pu, B.L.; Ren, W.; Zhao, W.M. Stability of an Electrodeposited Nanocrystalline Ni-Based Alloy Coating in Oil and Gas Wells with the Coexistence of H2S and CO2. Materials 2017, 10, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Xia, F.F.; Yao, L.M.; Li, H.X.; Jia, X. Investigation of the mechanical properties and corrosion behaviors of Ni-BN-TiC layers constructed via laser cladding technique. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 6671–6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.F.; Jia, W.C.; Ma, C.Y.; Wang, J. Synthesis of Ni-TiN composites through ultrasonic pulse electrodeposition with excellent corrosion and wear resistance. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Xia, F.F.; Ma, C.Y.; Li, Q. Research on the Corrosion Behavior of Ni-SiC Nanocoating Prepared Using a Jet Electrodeposition Technique. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 6336–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.I.; Ahmad, S.N. Wear and Corrosion Behavior of Zn-Ni-Cu and Zn-Ni-Cu-TiB2-Coated Mild Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 9137–9152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Chen, H.Y.; Zhao, X.; Fan, L.; Guo, X.M.; Yin, Y.S. Corrosion behavior of Ni-based coating containing spherical tungsten carbides in hydrochloric acid solution. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2019, 26, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, K.; Ahmed, N.A.; Issaadi, H.K.; Hamzaoui, A.H.; Aliouane, N.; Djermoune, A.; Chassigneux, C.; Eyraud, M. Electrodeposition of hydrophobic Ni-Co-TiO2 nanocomposite coatings on XC70 mild steels for improving corrosion resistance. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2025, 102, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, M.S.; Rasooli, A.; Sorkhabi, F.A. Electrodeposition of Ni-P/Ni-Co-Al2O3 duplex nanocomposite coatings: Towards improved mechanical and corrosion properties. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 2020, 98, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shen, L.D.; Qiu, M.B.; Tian, Z.J.; Jiang, W. Characterizations of Ni-CeO2 nanocomposite coating by interlaced jet electrodeposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 727, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.