Abstract

Rb2KWO3F3 elpasolite was synthesized via the solid-state reaction route. The phase purity of the obtained sample was verified by the XRD analysis with Rietveld refinement in space group Fm-3m, yielding the unit cell parameter a = 8.92413 (17) Å. The electronic structure and chemical states of the constituent elements were investigated using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. The binding energy of the W 4f7/2 core level (34.95 eV) was found to be characteristic of the W6+ oxidation state, while the values for Rb 3d, K 2p, O 1s and F 1s levels were consistent with those reported for related oxide and oxyfluoride compounds. First-principles density functional theory calculations were performed to model the electronic structure. The fac-configuration of the WO3F3 octahedra was identified as the most energetically favorable. The calculations revealed a direct band gap of 4.38 eV, with the valence band maximum composed primarily of O 2p orbitals and the conduction band minimum formed by W 5d orbitals. This combined experimental/theoretical study shows that the electronic structure and wide bandgap of Rb2KWO3F3 are governed by the WO3F3 units and are largely insensitive to the Rb/K substitution. The wide bandgap identifies this class of oxyfluorides as a promising platform for developing new UV-transparent materials.

1. Introduction

The incorporation of fluorine ions into an oxide crystal lattice leads to a competition between anions for the valence electrons of metal ions. This may result in the anion disordering, distortion of coordination polyhedrons, sequent phase transitions on the temperature variation, bond ionicity variation and other effects common in oxyhalogenides [1,2,3,4,5]. Complex metal oxyfluorides are attractive compounds for the creation of novel optical crystals transparent in UV and visible optical ranges [4,5,6,7,8]. Effects of mixed anion sublattice, however, were considered for a long time for a suite of transition metal compounds with [MO6−xFx] (M = W, Mo, Nb, Ti) units [1,2,3,4,7,9,10,11,12,13,14]. From the geometrical point of view, the strongest distortion of separated [MO6−xFx] octahedron is possible for x = 3 and such distortion can induce interesting effects in its chemical bonding and compound band structure. As it was obtained for selected compositions, oxyfluorides A2BMO3F3 (A, B = Na, K, Rb, Cs, Tl, NH4; M = Mo, W) show similar structural, ferroelectric and ferroelastic properties within certain temperature intervals [4,15,16,17,18,19]. Cubic paraelectric phase G0 with the elpasolite-type parent structure in space group Fm-3m was found for A2BMO3F3 compounds in the high temperature range T > T1 [2,12,13,19,20,21,22]. Complete disorder in anion positions is a principal characteristic of this state. As to Rb2KWO3F3, its elpasolite-type crystal structure was determined in [23]. At 67 K, the heat capacity anomaly was observed, and this effect was attributed to the phase transition to a low-temperature phase. Other properties of Rb2KWO3F3 remain unknown. It is worth mentioning that the synthesis of stoichiometric oxyfuorides is not a trivial task because the ratio O/F = 1 should be fixed in the final product to reach an anion balance. At the same time, many reagents commonly applied in the synthesis of oxyfluorides are chemically unstable in their contact to the air and this factor drastically complicates the reaction batch preparation.

The present study is aimed at the comparative evaluation of the electronic structure of Rb2KWO3F3 by experimental and theoretical methods with an emphasis on seeing the effects induced by the complex anion system and anion disorder. The electronic states of the constituent elements and valence band were examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for the powder sample. The band structure of Rb2KWO3F3 was calculated by DFT methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Synthesis

KF × 2H2O (99.98%), Rb2CO3, WO3 (99.999%), concentrated hydrofluoric acid (99.999%) and NH4F (99.98%) were used as starting reagents. All reagents were produced by the Chimkent production association “Phosphorus” (Chimkent, Kazakhstan). KF, RbF and WO3 components were employed in the synthesis of Rb2KWO3F3. First, WO3 was calcined in a platinum crucible at a temperature of 800 °C to remove the adsorbed species. The KF and RbF reagents were synthesized.

Anhydrous KF was obtained by the following reaction: KOH + NH4F = KF + H2O↑ + NH3↑. Then, to remove minor alkali and water traces, the resulting dry residue was mixed with NH4F and subjected to additional fluorination. The transparent pieces of the cake were selected and later used as a KF reagent. Anhydrous RbF was obtained by the following reaction: Rb2CO3 + 2HF = 2RbF + H2O + CO2↑. An excess of hydrofluoric acid with NH4F was added to the composition, and the resulting mixture was evaporated in a fluoroplastic crucible. The transparent part of the resulting reagent was separated, placed in a hermetically sealed container in a dry nitrogen environment and subsequently used for the synthesis. At the next step, a stoichiometric KF + 2RbF + WO3 mixture was ground in a mortar and poured into a platinum crucible and loaded into an oven. Heating to 900 °C was carried out at the rate of 100 °C/h, and then the temperature decreased to 830 °C at the rate of 3 °C/h. Starting from this temperature, the reactor was free cooled to room temperature for a day. As a result, a polycrystalline colorless cake, the composition of which corresponds to the Rb2KWO3F3 compound, was obtained, according to analytical data. A detailed description of the synthesis procedures can be found in the Supplementary Materials file.

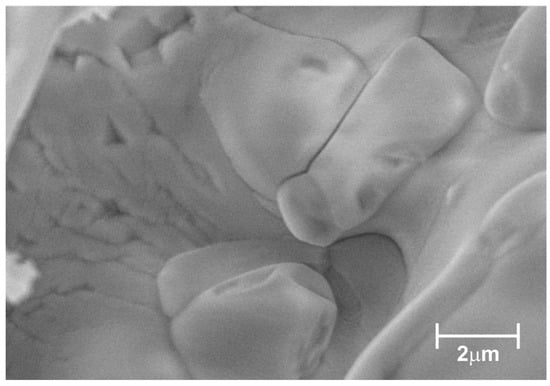

An SEM image of the selected Rb2KWO3F3 particle is shown in Figure 1. This is a tight agglomerate formed by strongly coalescent individual grains different in shape and size. The sample is characterized by a uniform contrast and the pronounced charging effect that indicates its dielectric nature.

Figure 1.

SEM image of Rb2KWO3F3 sample.

2.2. Characterization Techniques

The phase composition of the synthesized Rb2KWO3F3 sample at room temperature was elucidated by the XRD analysis. The powder diffraction data of Rb2KWO3F3 for Rietveld analysis was collected at room temperature with a Haoyuan DX-2700BH (Dandong, China) powder diffractometer (analytical equipment of Krasnoyarsk Regional Center of Research Equipment of Federal Research Center “Krasnoyarsk Science Center SB RAS”) with Cu-Kα radiation and a linear detector. The step size of 2θ was 0.016°, and the counting time was 0.2 s per step. All peaks were indexed by a cubic cell (Fm-3m) with parameters close to Rb2KWO3F3 [23]. Therefore, this structure was taken as the starting model for the Rietveld refinement which was performed using TOPAS 4.2 [24]. The particle micromorphology was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a LEO 1430 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) device. The sample preparation and measurement conditions can be found elsewhere [25,26].

The photoelectron spectra of K3WO3F3 were recorded using the surface analysis center SSC (Riber, Hillsborough, NJ, USA) with the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) method for the powder sample prepared by the chemical synthesis. Nonmonochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) with a power source of 300 W was used for the excitation of photoemission. The instrument energy resolution was chosen to be 0.7 eV. Under the conditions, the observed full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the Au 4f7/2 line was 1.31 eV. The binding energy (BE) scale was calibrated in reference to the Cu 3p3/2 (75.1 eV) and Cu 2p3/2 (932.7 eV) lines, assuring an accuracy of 0.1 eV in any peak energy position determination. The photoelectron energy drift due to charging effects was taken into account in reference to the position of the C 1s (284.6 eV) line generated by adventitious carbon present on the surface of the powder as inserted into the vacuum chamber.

2.3. Computational Method

First-principles calculations based on the density functional theory (DFT) were carried out using the CASTEP code, version 20.11 [27]. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional [28] was employed to describe the exchange–correlation interactions. The ultrasoft pseudopotentials generated on the fly were used. The structural optimization was performed with the convergence criteria set to a maximum force of 0.1 eV/Å and a maximum stress of 0.1 GPa. The plane-wave basis set was determined by an energy cutoff of 489.8 eV. Electronic self-consistent field (SCF) calculations were considered converged when the total energy difference between steps was less than 1.0 × 10−7 eV per atom. The Brillouin zone integrations were performed using a Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid with a spacing of approximately 0.

3. Results

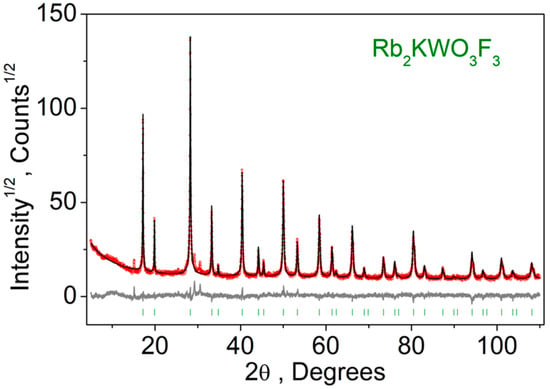

The recorded XRD pattern is shown in Figure 2. The refinement was stable and gave low R-factors (Table 1, Figure 2). The presence of pure cubic Rb2KWO3F3, space group Fm-3m, was found with the unit cell parameter a = 8.92413 (17) Å, and it is in a close relation to the value a = 8.9402(5) Å (ICSD 262285) previously reported in [23].

Figure 2.

Difference Rietveld plot of Rb2KWO3F3.

Table 1.

Main parameters of processing and refinement of the Rb2KWO3F3 sample.

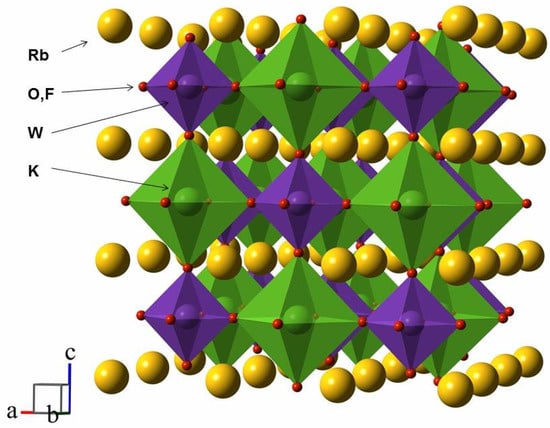

Before proceeding to the investigation of Rb2KWO3F3 properties, it is essential to analyze its crystallographic arrangement. At room temperature, this compound adopts a cubic double perovskite structure, where the alkali metals occupy interstitial sites, and the W6+ cations are in the center of octahedra coordinated by both oxygen and fluorine atoms. In Figure 3 is the three-dimensional atomic arrangement of Rb2KWO3F3. The O and F ions are shown in red representing mixed oxygen/fluorine sites.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of Rb2KWO3F3 at 24 °C.

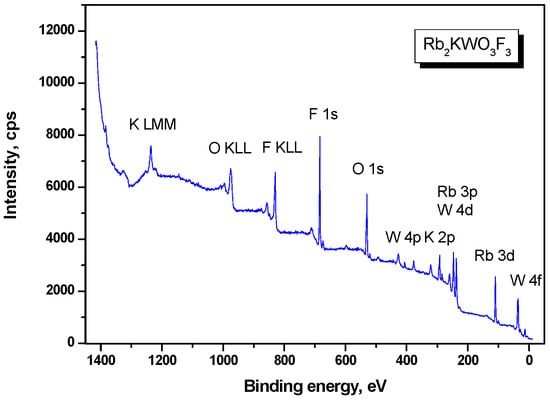

For the XPS measurements, fine Rb2KWO3F3 powder was prepared by grinding in the laboratory air, and the obtained particle product was deposited on the freshly prepared peace of indium foil. Such powder sample mounting decreases the probability of surface charging effects for dielectric materials under X-ray illumination. The recorded survey XPS spectrum is presented in Figure 4. Besides the constituent element core levels and Auger lines, a low-intensity signal of C 1s levels was detected. As can be reasonably assumed, the C 1s line is related to adventitious hydrocarbons captured by the particle surface from the laboratory air.

Figure 4.

Survey XPS spectrum of cubic Rb2KWO3F3.

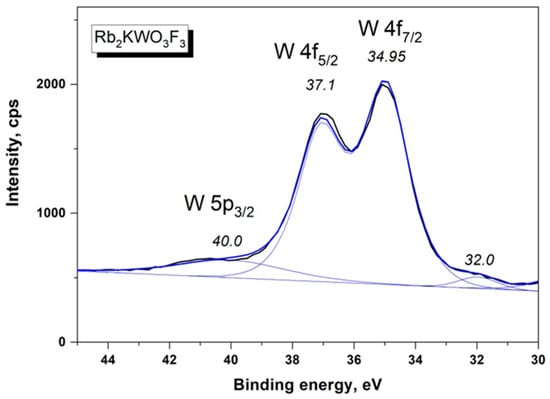

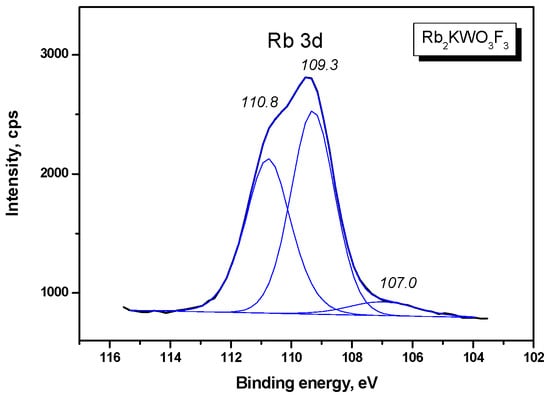

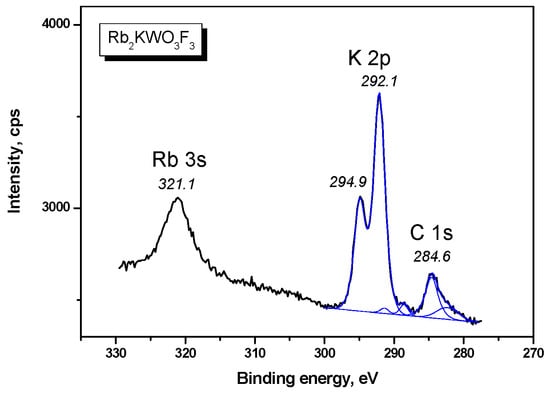

The W 4f doublet is shown in Figure 5. The W 4f doublet components are sharp, which indicates a unique chemical state of tungsten in the Rb2KWO3F3 sample. On the higher BE side of the W 4f5/2 component, a low-intensity shoulder is observed and it is assigned to the W 5p3/2 level. Also, a weak band is detected at 32.0 eV, and it is related to the K 3s core level. The Rb 3d doublet is presented in Figure 6. The doublet components were resolved by fitting under the standard conditions. In Figure 7, the C 1s line and the K 2p doublet are shown. The C 1s line is asymmetric and is evidently a multicomponent feature, and, for the BE scale calibration, the value of 284.6 eV was assigned to the line maximum. The K 2p doublet components are well resolved, and the BE value of the K 2p3/2 component (292.6 eV) is close to that found earlier for K+ ions in several complex potassium-containing crystals from the KTiOPO4 and KGd(WO4)2 families.

Figure 5.

Detailed XPS spectrum of the W 4f doublet and W 5p3/2 line in Rb2KWO3F3.

Figure 6.

Detailed XPS spectrum of the Rb 3d doublet in Rb2KWO3F3.

Figure 7.

Detailed XPS spectrum of the C 1s, K 2p and Rb 3s lines in Rb2KWO3F3.

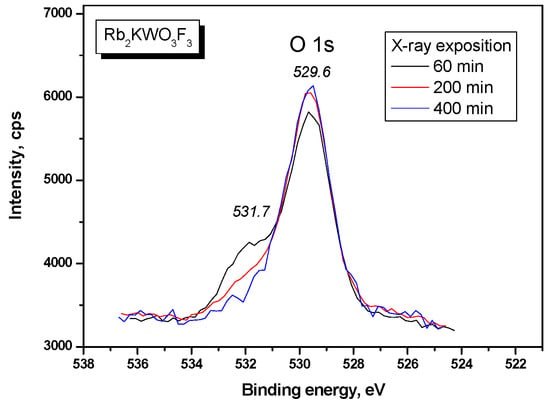

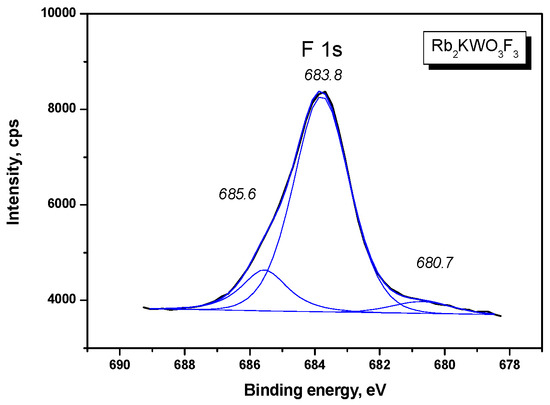

The O 1s and F 1s core levels recorded in Rb2KWO3F3 are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. As to the O 1s band, just at the start of the measurement, a pronounced shoulder was observed on the higher BE side of the main line. However, this shoulder continuously decreased in intensity under the X-ray illumination and practically disappeared for 400 min. As it can be reasonably assumed, the shoulder was generated by occasional absorbates from the laboratory air, and these molecules were desorbed or decomposed by the X-ray radiation. The F 1s band contains several components with the evident dominance of the line at 683.8 eV. The nature of two low-intensity components remains unknown.

Figure 8.

Detailed XPS spectrum of the O 1s core level in Rb2KWO3F3.

Figure 9.

Detailed XPS spectrum of the F 1s line in Rb2KWO3F3.

The chemical composition of the sample determined by XPS is Rb:K:W:O:F = 0.18:0.13:0.07:0.30:0.32, which is in a reasonable relation to the nominal composition of Rb2KWO3F3 as Rb:K:W:O:F = 0.20:0.10:0.10:0.33:0.33. In the calculations, the reported atomic sensitivity factors were used [29]. The Auger parameters of the constituent elements in Rb2KWO3F3 were determined as equal to αK = 543.05 eV, αO = 1041.18 eV and αF = 1340.72 eV. The BE values obtained for the element core levels and Auger lines in Rb2KWO3F3 are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Element core levels and Auger lines in Rb2KWO3F3 and K3WO3F3 *.

As is seen in Table 3, the BE value of the W 4f7/2 component (34.95 eV) in Rb2KWO3F3 is within the range of the values commonly observed for the W6+ state in different oxide crystals and K3WO3F3 [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. This means that the chemical states of W6+ ions in WO6 and WO3F3 units are similar.

Table 3.

BE values of W 4f7/2 and O 1s lines in inorganic tungstates and W6+-containing oxyfluorides.

As seen in Table 4, the totality of Rb-containing compounds measured by XPS is very limited. Nevertheless, the BE values obtained for the Rb 3d5/2 and Rb 3p3/2 lines in Rb2KWO3F3 are in the ranges characteristic for oxides and oxyfluorides.

Table 4.

BE values of Rb 3d5/2, Rb 3p3/2 and O 1s lines in related Rb-containing crystals.

In particular, excellent coincidence of the BE values is reached in Rb2KTiOF5, Rb2KMoO3F3 and Rb2KWO3F3 oxyfluorides measured using the same spectrometer [55,59]. Thus, it can be concluded that the chemical state of the Rb+ ion in oxyfluoride crystals is less dependent on the presence of other cations.

The electronic parameters of K-containing crystals measured by XPS are summarized in Table 5. In this case, we have a rare possibility opportunity to compare the BE values of K 2p3/2 line in fluorides and oxides. Indeed, the XPS measurements were carried out for 10 fluorides, and, in the compounds, the average BE value for the K 2p3/2 component wasis equal to 293.2 eV. As to oxide compounds, we have a set of 13 crystals that yields the average BE value of 292.7 eV. The calculation of the average BE value gives a possibility to weaken the occasional BE data scattering induced by different energy scale calibration and surface charging effects in different XPS spectrometers. Thus, the results show that the average BE value for the K 2p3/2 line in fluorides and oxides is noticeably different and it indicates a different ionicity of the chemical bonds between K+ and the related anion. Then, it can be reasonably assumed that the BE value for the K 2p3/2 line in oxyfluorides could be intermediate, i.e., between those of fluorides and oxides. Indeed, the calculation for six6 oxyfluorides reported in Table 5 yields the value of 292.8 eV. However, the more accurate analysis of available experimental results for oxyfluorides indicates that the measurements were produced using only two different XPS spectrometers. Moreover, the BE values reported in [60] are generally higher than the values recorded for the K 2p3/2 line in [5,47] and this work. Thus, the statistics for oxyfluorides may be not robust and further accumulation of the experimental results for oxyfluorides using different XPS spectrometers is topical required for a more correct comparison.

Table 5.

BE values of K 2p3/2, O 1s and F 1s lines in related K-containing crystals.

The Δ-self-consistent-field (ΔSCF, or “core-hole”) method has recently become a common approach for computing XPS core-level shifts in simple solids and molecules. For example, Ratcliff et al. [68] used this method to interpret the XPS spectra of Ga2O3 by performing core-level binding-energy calculations for both the γ- and β-polymorphs. Kahk and Lischner applied the ΔSCF approach to compute C 1s and O 1s binding-energy shifts for adsorbates on Cu(111), achieving very good agreement with experiment [69]. Ozaki and Lee proposed a ΔSCF framework for absolute core-level energies in solids, demonstrating an average error of about 0.4 eV [70]. These studies illustrate the growing utility of ΔSCF approaches for exploring chemical bonding through calculated binding-energy shifts. Applying such a method to Rb2KWO3F3 could in principle provide complementary insight into the character of W–O/F bonding and the anion-dependent chemical environment. However, the structural complexity of the elpasolite framework, combined with the presence of multiple chemically distinct sites and disordered anions, renders ΔSCF calculations significantly more complex than for the crystals discussed above. A detailed core-hole-based theoretical treatment is thus beyond the scope of the present study, but it represents a promising direction for future investigation.

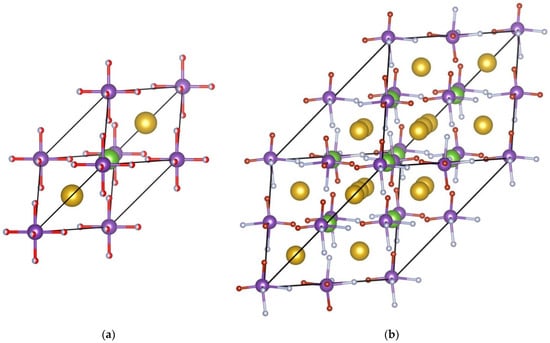

In cases of Rb2KWO3F3, the occupancies of O and F ions determined by the experimental XRD represent an averaged distribution over the entire sample volume. In reality, at each specific anion site, there is either an O ion or an F ion, but not both simultaneously. To model such systems within the DFT calculations, the conventional approach is to enlarge the unit cell, creating a supercell that allows for an explicit placement of O and F ions throughout the lattice while maintaining an integer multiple of the formula units. To perform the procedure described above, we considered the primitive Rb2KWO3F3 cell shown in Figure 10a. It contains one Rb2KWO3F3 formula unit: 1 Rb ion, 2 K ions, 1 W ion, 3 O and 3 F ions. This primitive cell was expanded two times along each crystallographic direction, resulting in an eightfold increase in the primitive cell volume, as illustrated in Figure 10b. Thus, the expanded primitive cell contains eight W ions. For the considered oxyfluoride, the arrangement of O and F ions in WO3F3 octahedra is analyzed in terms of the so-called mer- and fac-configurations, as shown in Figure S1. It is evident that various occupancy scenarios of the supercell should be considered, including configurations with only mer- or only fac-octahedra, as well as mixed configurations. This was performed using a Python (3.10.7 version) script provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S2).

Figure 10.

Primitive Rb2KWO3F3 cell (a) and its 2 × 2 × 2 supercell (b) used for modeling the oxygen and fluorine ion distribution. Yellow spheres represent Rb atoms, green spheres represent K atoms, purple spheres represent W atoms in WO3F3 octahedra, and red/light gray spheres denote O and F atoms, respectively.

Considering that there is one tungsten ion per formula unit, the configurations were examined starting from the case where all eight octahedra adopt the fac-configuration, then with one octahedron in mer- and seven octahedra in fac-, etc., as listed in Table 6. The considered supercells were fully optimized. The difference in the total energy (relative to pure fac-configuration) per formula unit for the analyzed configurations is also presented in Table 6. According to the simulation results, the energetically most favorable structure of Rb2KWO3F3 should be composed of octahedra with the fac-arrangement of O and F ions.

Table 6.

Relative total energy per formula unit for different mer-/fac-configurations of WO3F3 units in Rb2KWO3F3.

This result is in excellent relation to those earlier obtained for elpasolite-type oxyfluorides, namely (NH4)3MoO3F3, (NH4)3WO3F3 and Rb2KMoO3F3 [71,72,73]. Thus, in Rb2KWO3F3, the W6+ ion is coordinated by three O2− and three F− in a facial (fac) arrangement, which places all three like ligands on one face of the octahedron (C3v symmetry). This high-symmetry configuration maximizes orbital overlap between the W 5d orbitals and the ligand 2p orbitals (especially the three O 2p orbitals on one face), leading to stronger covalent W–O/F bonding and lowering the of electronic energy. Clustering identical anions on one face also reduces internal strain and Coulomb repulsion: the three O2− are kept symmetrically around the metal and can better screen each other’s charge, while the three F− on the opposite face form a balanced field. Moreover, separating oxygen and fluorine onto different faces produces a local polar ordering (O-rich face vs. F-rich face) which can further stabilize the lattice. Supporting evidence comes from related oxyfluorides: for example, single-crystal X-ray data for (NH4)3WO3F3 shows a slightly compressed [WO3F3]3− octahedron in fac form, with the W atom shifted toward the face of three oxygens [72]. It should be noted that the shift in the W atom in Rb2KWO3F3 model structure is clearly seen in Figure 10. Thus, the following band structure calculations were performed for the fac-arrangement of the WO3F3 units.

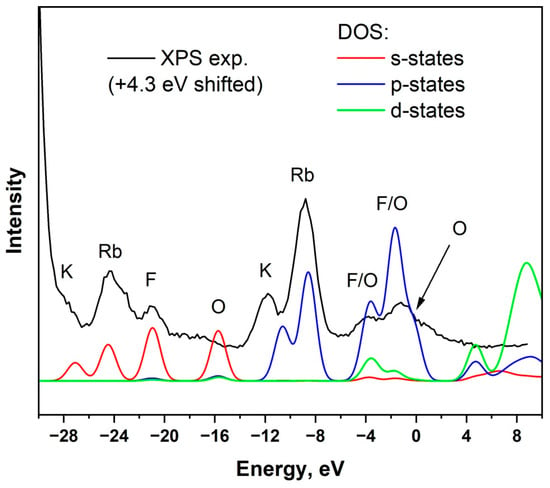

Figure 11 is a comparison between the experimental XPS spectrum over the low BE range and the calculated partial density of states. The experimental XPS spectrum was shifted by +4.3 eV to align the valence band maximum with the calculated DOS. This energy shift is associated with the difference in the absolute energy scales accepted in the XPS measurements and DFT calculations. As seen in the calculated DOS spectrum, the states near the valence band maximum are primarily composed of O 2p and F 2p orbitals. In particular, the valence band top is associated with O 2p electrons.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectrum and calculated partial density of states for Rb2KWO3F3.

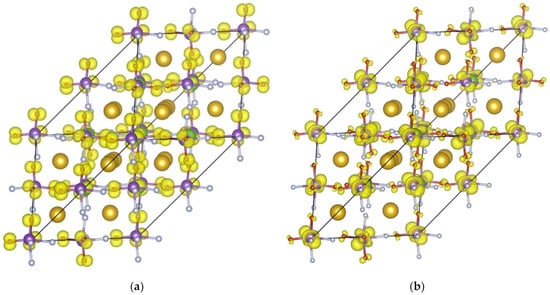

The valence-band edge charge density isosurfaces (shown in yellow) are illustrated in Figure 12a, indicating that the valence-band maximum is predominantly localized on the oxygen ions, where it forms dumbbell-shaped clouds. As seen in Figure 12b, the conduction band minimum charge density is centered on the W cations with the d-like lobes directed between the octahedral vertices; thus, presenting the 5d states of tungsten. The orbital distribution corroborates the DOS alignment, placing the oxygen p-states at the valence band top and the tungsten d-states at the conduction band bottom.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of electron density (shown in yellow) calculated for Rb2KWO3F3 corresponding to the valence band top (a) and the conduction band bottom (b).

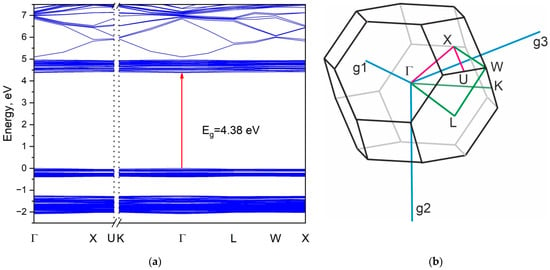

The calculated electronic band structure of Rb2KWO3F3 is presented in Figure 13a along the representative high-symmetry points of the Brillouin zone (BZ), which is shown in Figure 13b. It clearly exhibits its insulating behavior with a wide band gap equal to 4.38 eV. The electronic transition is direct, and it is located in the center of BZ. However, it should be pointed that both the valence band top and the conduction band bottom are nearly flat in Rb2KWO3F3. Thus, the band structures of K3WO3F3 [4] and Rb2KWO3F3 are very similar. The energy bandgap values, namely, 4.32 eV in K3WO3F3 and 4.38 eV in Rb2KWO3F3, are governed by the WO3F3 units that are less sensitive to the Rb substitution for K.

Figure 13.

Band structure (a) of Rb2KWO3F3 along the high-symmetry points of the Brillouin zone (b).

It is well established that semilocal GGA functionals such as PBE systematically underestimate [74] fundamental band gap in insulators and semiconductors. Hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06 [75,76]) reduce this error and typically bring band gaps much closer to the experiment; alternatively, a simple scissor correction can be applied as a constant upward shift to the PBE gap without changing the band topology [77,78]. In our case, the PBE band gap of 4.38 eV for Rb2KWO3F3 should thus be regarded as a lower bound; adopting HSE06 (or applying a scissor shift) would be expected to increase band gap. Notably, the magnitude we obtain is consistent with reported optical data for such closely related oxyfluoride as K3WO3F3 exhibits a UV absorption edge at Eg (opt) ≈ 4.32 eV. In other words, despite the known underestimation by GGA-PBE, the computed gap is in the same range as the experimental value in similar crystal, supporting the validity of our calculations.

The obtained results on the electronic structure of Rb2KWO3F3 show that, in this crystal family, the band structure is dominated by characteristics of WO3F3 units, and it is less sensitive to other elements. We can expect that future efforts should be focused on doping effects aimed at the crystal property tuning without drastic bandgap decrease, as it was reached in other oxyfluorides [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88]. This may open the way for the consideration of Rb2KWO3F3 and related oxyfluorides as promising materials for UV-transparent optics, dielectric windows, and luminescent host lattices (RE3+ doping).

4. Conclusions

The results of the present study give new insights into the nature and electronic properties of oxyfluorotungstate Rb2KWO3F3. The pure cubic phase sample was synthesized by the high-temperature chemical synthesis with the precise control of the O/F ration. The electronic structure of Rb2KWO3F3 was comparatively studied by XPS measurements and DFT calculations. It was revealed that, in Rb2KWO3F3, the direct bandgap Eg = 4.38 eV is governed by the O 2p orbitals located at the valence band maximum and the W 5d orbitals located at the conduction band minimum. In general, the structural and electronic properties of Rb2KWO3F3 and of the earlier studied K3WO3F3 elpasolites are less sensitive to the Rb/K substitution. Both crystals are characterized by wide bandgap values, and this indicates that the oxyfluorides are transparent in the UV spectral range and this chemical class is promising for the creation of new UV materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst16010018/s1, Synthesis steps; Figure S1: Schematic representation of mer- (a) and fac- (b) configurations of the WO3F3 octahedron in the Rb2KWO3F3 structure; Figure S2: Python script.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A. and A.O.; methodology, L.I., V.K. and S.Z.; software, V.K. and A.O.; formal analysis, V.K., M.M. and A.O.; investigation, V.A. and M.M.; data curation, T.G., V.K., M.M. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A., L.I., V.K., M.M. and A.O.; writing—review and editing, V.A., V.K. and A.O.; visualization, M.M., V.K. and A.O.; funding acquisition, V.A., L.I., V.K. and A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is partly supported by the state assignment of IGM SB RAS No. 122041400031-2 (synthesis and crystal growth). Special gratitude is of Aleksandr Oreshonkov for the support of the state assignment of Kirensky Institute of Physics (FWES-2024-0003) and of Victor Atuchin and Valery Kesler for the support of the state assignment of Institute of Semiconductor Physics (FWGW-2025-0024 and FWGW-2025-0008, respectively).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results can be obtained from the authors on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The experiments were carried out on the equipment of the CKP “Nanostructury”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Berg, R.W. Progress in niobium and tantalum coordination chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1992, 113, 1–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M.R.; Lesage, J.; Baek, J.; Halasyamani, P.S.; Stern, C.L.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. Cation-anion interactions and polar structures in the solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13963–13969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y.; Yamaura, K.; Takayama-Muromachi, E. Oxyfluoride chemistry of layered perovskite compounds. Appl. Sci. 2012, 2, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Isaenko, L.I.; Kesler, V.G.; Lin, Z.S.; Molokeev, M.S.; Yelisseyev, A.P.; Zhurkov, S.A. Exploration on anion ordering, optical properties and electronic structure in K3WO3F3 elpasolite. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 187, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, Y.; Atuchin, V. Chemical bonding effects and physical properties of noncentrosymmetric hexagonal fluorocarbonates ABCO3F (A: K, Rb, Cs; B: Mg, Ca, Sr, Zn, Cd). Molecules 2022, 27, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.S.; Bai, L.; Liu, L.J.; Lee, M.H.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.Y.; Chen, C.T. Influences of twist boundaries on optical effects: Ab initio studies of the deep ultraviolet nonlinear optical crystal KBe2BO3F2. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 073721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jiang, X.; Wu, C.; Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Huang, Z.; Humphrey, M.G.; Zhang, C. Ultrawide bandgap and outstanding second-harmonic generation response by a fluorine-enrichment strategy at a transition-metal oxyfluoride nonlinear optical material. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wei, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yu, H. Assembly of π-conjugated [B3O6] units by mer-isomer [YO3F3] octahedra to design a UV nonlinear optical material, Cs2YB3O6F2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202406318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausewang, G.; Rüdorff, W. AI3MeOxF6−x—Verbindungen mit x = 1, 2, 3, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1969, 364, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravez, J. The inorganic fluoride and oxyfluoride ferroelectrics. J. Phys. III 1997, 7, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Heier, K.R.; Norquist, A.J.; Halasyamani, P.S.; Duarte, A.; Stern, C.L.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. The polar [WO2F4]2− anion in the solid state. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokeev, M.S.; Vasiliev, A.D.; Kocharova, A.G. Crystal structures of room- and low-temperature phases in oxyfluoride (NH4)2KWO3F3. Powder Diffr. 2007, 22, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Molokeev, M.S.; Yurkin, G.Y.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Kesler, V.G.; Laptash, N.M.; Flerov, I.N.; Patrin, G.S. Synthesis, structural, magnetic, and electronic properties of cubic CsMnMoO3F3 oxyfluoride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 10162–10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokina, V.D.; Flerov, I.N.; Molokeev, M.S.; Pogorel’tsev, E.I.; Bogdanov, E.V.; Krylov, A.S.; Bovina, A.F.; Voronov, V.N.; Laptash, N.M. Heat capacity, p–T phase diagram, and structure of Rb2KTiOF5. Phys. Solid State 2008, 50, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokina, V.D.; Flerov, I.N.; Gorev, M.V.; Molokeev, M.S.; Vasiliev, A.D.; Laptash, N.M. Effect of cationic substitution on ferroelectric and ferroelastic phase transitions in oxyfluorides A2A′WO3F3 (A, A′: K, NH4, Cs). Ferroelectrics 2007, 347, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péraudeau, G.; Ravez, J.; Arend, H. Etude des transitions de phases des composes Rb2KMO3F3, Cs2KMO3F3 et Cs2RbMO3F3 (M = Mo, W). Solid State Commun. 1978, 27, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravez, J.; Péraudeau, G.; Arend, H.; Abrahams, S.C.; Hagenmüller, P. A new family of ferroelectric materials with composition A2BMO3F3 (A, B = K, Rb, Cs, for rA+ ≥ rB+ and M = Mo, W). Ferroelectrics 1980, 26, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraudeau, G.; Ravez, J.; Hagenmuller, P.; Arend, H. Study of phase transitions in A3MO3F3 compounds (A = K, Rb, Cs; M = Mo, W). Solid State Commun. 1978, 27, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaminade, J.-P.; Cervera-Marzal, M.; Ravez, J.; Hagenmuller, P. Ferroelastic and ferroelectric behavior of the oxyfluoride Na3MoO3F3. Mater. Res. Bull. 1986, 21, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokeev, M.S.; Misyul’, S.V.; Fokina, V.D. Structure transitions during phase transitions in the K3WO3F3 oxyfluoride. Phys. Solid State 2011, 53, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, S.C.; Bernstein, J.L. Paraelectric-paraelastic Rb2KMoO3F3 structure at 343 and 473 K. Acta Cryst. B 1981, 37, 1332–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, F.J.; Norén, L.; Withers, R.L. Synthesis, electron diffraction, XRD and DSC study of the new elpasolite-related oxyfluoride, Tl3MoO3F3. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 174, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartashev, A.V.; Molokeev, M.S.; Isaenko, L.I.; Zhurkov, S.A.; Fokina, V.D.; Gorev, M.V.; Flerov, I.N. Heat capacity and structure of Rb2KMeO3F3 (Me: Mo, W) elpasolites. Solid State Sci. 2012, 14, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker AXS TOPAS. V4: General Profile and Structure Analysis Software for Powder Diffraction Data—User’s Manual; Bruker AXS: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Chimitova, O.D.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Molokeev, M.S.; Kim, S.-J.; Surovtsev, N.V.; Bazarov, B.G. Synthesis, structural and vibrational properties of microcrystalline RbNd(MoO4)2. J. Cryst. Growth 2011, 318, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Subanakov, A.K.; Aleksandrovsky, A.S.; Bazarov, B.G.; Bazarova, J.G.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Krylov, A.S.; Molokeev, M.S.; Oreshonkov, A.S.; Stefanovich, S.Y. Structural and spectroscopic properties of new noncentrosymmetric self-activated borate Rb3EuB6O12 with B5O10 units. Mater. Des. 2018, 140, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.J.; Segall, M.D.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Probert, M.J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M.C. Furst principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. 2005, 220, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.D.; Riggs, W.M.; Davis, L.E.; Moulder, J.F.; Muilenberg, G.E. (Eds.) Handbook of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy; Perkin-Elmer Corp., Physical Electronics Division: Eden Prairie, MN, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Khyzhun, Y. XPS, XES and XAS studies of the electronic structure of tungsten oxides. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 305, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khyzhun, Y.; Strunskus, T.; Cramm, S.; Solonin, Y.M. Electronic structure of CuWO4: XPS, XES and NEXAFS studies. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 389, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.; Nataraj, D.; Khyzhun, O.Y.; Djaoued, Y.; Robichaud, J.; Mangalaraj, D. Hydrothermal synthesis and electronic properties of FeWO4 and CoWO4 nanostructures. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 493, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-X.; Yao, H.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, J.-Y.; Llu, S.-J.; Yu, S.-H. Hierarchical FeWO4 microcrystals: Solvothermal synthesis and their photocatalytic and magnatic properties. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.T.; Hercules, D.M. Studies of nickel-tungsten-alumina catalysts by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 1976, 80, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, P.; Gai, S.; Niu, N.; He, F.; Lin, J. Fabrication and luminescent properties of CaWO4:Ln3+ (Ln = Eu, Sm, Dy) nanocrystals. J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12, 2295–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefedov, V.I. A comparison of results of an ESCA study of nonconducting solids using spectrometers of different constructions. J. Elect. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1982, 25, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Li, Z.; Ding, Z.; Pan, H.; Wang, X.; Fu, X. Nanoplates of α-SnWO4 and SnW3O9 prepared via a facile hydrothermal method and their gas-sensing property. Sens. Actuat. B 2009, 140, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gao, Y. Fabrication of luminescent SrWO4 thin films by a novel electrochemical method. Mater. Res. Bull. 2007, 42, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charton, P.; Gengembre, L.; Armand, P. TeO2-WO3 glasses: Infrared, XPS and XANES structural characterization. J. Solid State Chem. 2002, 168, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Kesler, V.G.; Maklakova, N.Y.; Pokrovsky, L.D. Core level spectroscopy and RHEED analysis of KGd(WO4)2 surface. Solid State Commun. 2005, 133, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Kesler, V.G.; Maklakova, N.Y.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Sheglov, D.V. Core level spectroscopy and RHEED analysis of KGd0.95Nd0.05(WO4)2 surface. Eur. Phys. J. B 2006, 51, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Khyzhun, O.Y.; Sinelnichenko, A.K.; Ramana, C.V. Surface crystallography and electronic structure of potassium yttrium tungstate. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 033518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, S.; Sun, H.; Fan, W.; Zhao, X.; Sun, X. Experimental and theoretical studies on the enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnWO4 nanorods by fluorine doping. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 7680–7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, X. A facile microwave solvothermal process to synthesize ZnWO4 nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 480, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Galashov, E.N.; Khyzhun, O.Y.; Kozhukhov, A.S.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Shlegel, V.N. Structural and electronic properties of ZnWO4(010) cleaved surface. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 2479–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Galashov, E.N.; Khyzhun, O.Y.; Bekenev, V.L.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Borovle, Y.A.; Zhdankov, V.N. Low thermal gradient Czochralski growth of large CdWO4 crystals and electronic properties of (010) cleaved surface. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 236, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Kesler, V.G.; Molokeev, M.S.; Aleksandrov, K.S. Structural and electronic parameters of ferroelectric K3WO3F3. Solid State Commun. 2010, 150, 2085–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.E.; Van Wazer, J.R.; Stec, W.J. Inner-orbital photoelectron spectroscopy of the alkali metal halides, perchlorates, phosphates, and pyrophosphates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Isaenko, L.I.; Kesler, V.G.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Tarasova, A.Y. Electronic parameters and top surface chemical stability of RbPb2Br5. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, Y.; Isaenko, L.I.; Kesler, V.G.; Pashkov, V.M.; Yelisseyev, A.P.; Denysyuk, N.M.; Khyzhun, O.Y. Electronic structure and fundamental absorption edges of KPb2Br5, K0.5Rb0.5Pb2Br5, and RbPb2Br5 single crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2012, 73, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukarev, A.V.; Korolkov, D.V. XPS study of Group IA carbonates. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2004, 2, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlqvist, M.; Shchukarev, A. XPS spectra and electronic structure of Group IA sulfates. J. Elect. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2007, 156–158, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, B.V.; Sarat, L.L.; Zubkov, V.G.; Tyutyunnik, A.P.; Berger, I.F.; Kuznetsov, M.V.; Perelyaeva, L.A.; Shein, I.R.; Ivanovskii, A.L.; Shulgin, B.V.; et al. Structural, luminescence, and electronic properties of the alkaline metal-strontium cyclotetravanadates M2Sr(VO3)4. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 155205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Aleksandrovsky, A.S.; Chimitova, O.D.; Diao, C.-P.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Kesler, V.G.; Molokeev, M.S.; Krylov, A.S.; Bazarov, B.G.; Bazarova, J.G.; et al. Electronic structure of β-RbSm(MoO4)2 and chemical bonding in molybdates. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Khyzhun, O.Y.; Chimitova, O.D.; Molokeev, M.S.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Bazarov, B.G.; Bazarova, J.G. Electronic structure of β-RbNd(MoO4)2 by XPS and XES. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2015, 77, 101–108. 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Kesler, V.G.; Meng, G.S.; Lin, Z.S. The electronic structure of RbTiOPO4 and the effects of the A-site cation substitution in KTiOPO4-family crystals. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2012, 24, 405503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimitova, O.D.; Bazarov, B.G.; Bazarova, J.G.; Atuchin, V.V.; Azmi, R.; Sarapulova, A.E.; Mikhailova, D.; Balachandran, G.; Fiedler, A.; Geckle, U.; et al. The crystal growth and properties of novel magnetic double molybdate RbFe5(MoO4)7 with mixed Fe3+/Fe2+ states and 1D negative thermal expansion. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 3297–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Isaenko, L.I.; Kesler, V.G.; Kang, L.; Lin, Z.; Molokeev, M.S.; Yelisseyev, A.P.; Zhurkov, S.A. Structural, spectroscopic, and electronic properties of cubic G0-Rb2KTiOF5 oxyfluoride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7269–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Isaenko, L.I.; Kesler, V.G.; Molokeev, M.S.; Zhurkov, S.A. Synthesis and structural properties of cubic G0-Rb2KMoO3F3 oxyfluoride. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 2455–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, N.M.; Nefedov, V.I.; Buslaev, Y.A.; Kokunov, Y.V.; Porai-Koshits, M.A.; Ilin, E.G.; Mihailov, Y.N. XPS study of complex fluorides and oxyfluorides of elements from IV-VI groups. Izv. Academii Nauk USSR Phys. 1972, 36, 376–380. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoshkalenko, V.V.; Senkevich, A.I.; Aleshin, V.G. Photoelectron spectra and band structure of alkali hallide crystals. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. USSR 1972, 206, 593–596. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.H.; Mo, M.S.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, R.; Yu, W.C.; Qian, Y.T. A simple approach to synthesize KNiF3 hollow spheres by solvothermal method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 89, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Hong, J.M.; Chen, X.T.; Yu, Z.; You, X.Z. Mild solvothermal synthesis of KZnF3 and KCdF3 nanocrystals. Mater. Lett. 2005, 59, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Isaenko, L.I.; Kesler, V.G.; Tarasova, A.Y. Single crystal growth and surface chemical stability of KPb2Br5. J. Cryst. Growth 2011, 318, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Kesler, V.G.; Maklakova, N.Y.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Semenenko, V.N. Study of KTiOPO4 surface by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and reflection high-energy electron diffraction. Surf. Interface Anal. 2002, 34, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana, C.V.; Atuchin, V.V.; Becker, U.; Ewing, R.C.; Isaenko, L.I.; Khyzhun, O.Y.; Merkulov, A.A.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Sinelnichenko, A.K.; Zhurkov, S.A. Low-energy Ar+ ion-beam-induced amorphization and chemical modification of potassium titanyl arsenate (001) crystal surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 2702–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhard, M.; Evans, C.; Land, T.A.; Nelson, A.J. A study of potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) crystal surfaces by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2001, 8, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, L.E.; Oshima, T.; Nippert, F.; Janzen, B.M.; Kluth, E.; Goldhahn, R.; Feneberg, M.; Mazzolini, P.; Bierwagen, O.; Wouters, C.; et al. Tackling disorder in γ-Ga2O3. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2204217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahk, J.M.; Lischner, J. Core electron binding energies of adsorbates on Cu(111) from first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 30403–30411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Lee, C.-C. Absolute binding energies of core levels in solids from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 026401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. The crystal structures of ammonium fluoferrate, fluo-aluminate and oxyfluomolybdate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1924, 46, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovenko, A.A.; Laptash, N.M. Orientational disorder in crystals of (NH4)3MoO3F3 and (NH4)3WO3F3. Acta Cryst. B 2008, 64, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krylov, A.S.; Sofronova, S.N.; Kolesnikova, E.M.; Vtyurin, A.N.; Isaenko, L.I. Lattice dynamics of oxyfluoride Rb2KMoO3F3. Ferroelectrics 2012, 441, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, J.M.; Tahir-Kheli, J.; Goddard, W.A.I. Resolution of the band gap prediction problem for materials design. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borlido, P.; Aull, T.; Huran, A.W.; Tran, F.; Marques, M.A.L.; Botti, S. Large-scale benchmark of exchange–correlation functionals for the determination of electronic band gaps of solids. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 5069–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, A.J.; Scuseria, G.E. Predicting band gaps with hybrid density functionals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 4165–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolph, B.; Furthmüller, J.; Bechstedt, F. Optical properties of semiconductors using projector-augmented waves. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 125108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Tian, H.; Jiang, X.; Xu, F.; Zhao, X.; Lin, Z.; Luo, M.; Ye, N. Uncovering a vital band gap mechanism of pnictides. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Cao, W.; Gu, J.; Wang, D. Recent achievements of d0 transition-metal-based oxyfluorides: Crystal chemistry and application in second-order NLO materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2026, 549, 217347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Yao, G.; Quan, L.; Chang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; Liu, P.; Jia, Y.; et al. Structural phase transformation and microwave dielectric properties of polymorphic Li3Mg2SbO6−xF2x oxyfluoride nanoceramics. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 64045–64051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Tian, H.; Li, K.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C. Luminescence properties of Tm3+/Yb3+ ions doped oxyfluoride glass-ceramic containing Y5O4F7 and NaYF4 nanocrystals. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1037, 182533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Li, Y.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, B.; Yang, F.; Peng, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Huang, D.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Less is more: An oxyfluoride garnet broadband cyan-green phosphor towards highly efficient full-spectrum WLEDs. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 985, 173997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, B.; Paul, S.; Das, S.; Chattopadhyay, A.P.; Ali, S.I. Synthesis, crystal structure and photocatalytic studies of new oxyfluoride Cu5AsO5F5. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1286, 135610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Feng, Q.; Deng, L.; Li, J.; Han, S. A3ZnNO3X4 (A = Rb, NH4, X = Cl, I): Regulating cations and halides yields birefringent crystals with significantly enhanced optical anisotropy. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 17098–17103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Cheng, X.; Minaud, C.; Mentré, O.; Vieira, B.J.C.; Waerenborgh, J.C.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Lü, M. Fluorinated phosphates, BaMPO4F (M = Mn, Fe), with one-dimensional channels: Structure and magnetism. Inorg. Chem 2025, 64, 11731–11743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.; Fischer, L.; Hoffmann, K.F.; Limberg, N.; Millanvois, A.; Oesten, F.; Pérez-Bitrián, A.; Schlögl, J.; Toraman, A.N.; Wegener, D.; et al. On pentafluoroorthotellurates and related compounds. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 9140–9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, D.; Klepov, V.V.; Misture, S.T.; Schaeperkoetter, J.C.; Jacobsohn, L.G.; Aziziha, M.; Schorne-Pinto, J.; Thomson, S.A.J.; Hines, A.T.; Besmann, T.M.; et al. Luminescence and scintillation in the niobium doped oxyfluoride Rb4Ge5O9F6:Nb. Inorganics 2022, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, X.; Gao, H.; Duanmu, K.; Wu, C.; Lin, Z.; Huang, Z.; Humphrey, M.G.; Zhang, C. Breaking the deep-UV transparency/optical nonlinearity trade-off: Three-parameter optimization in oxyfluorides by tailoring d0-metal incorporation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 46, e202513438. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.