Abstract

The typical microstructure and mechanical properties of twin-roll cast (TRC) 2139 aluminum alloy were investigated and compared with mold casting (MC) 2139 alloy. This work pioneers the application of TRC to produce 2139 Al-Cu-Mg alloy, a material that is challenging for rapid solidification. The TRC process resulted in a denser dendritic structure, with the composition of intermetallic compounds, primarily Al2Cu and Al2CuMg, remaining largely stable throughout the casting process. After solution treatment, the recrystallized grains in the MC sheets were uniformly distributed, while the TRC sheets exhibited a more localized and refined recrystallized microstructure, particularly within coarse second-phase regions. Following heat treatments, the TRC sheets showed a significant increase in the Ω phase after T6, with a slight growth in size and a uniform distribution, while the Ω phase in T8 showed an increased density and smaller size, which diffused evenly across the material. The TRC process uniquely refines the microstructure and enhances Ω phase precipitation, yielding a 10%+ improvement in strength and ductility over conventional casting. The mechanical properties of the TRC sheets improved significantly: tensile and yield strengths increased by over 10% after T6, compared to MC sheets, with elongation slightly higher in TRC. T8 treatment further enhanced the mechanical properties of the TRC sheets, achieving an improvement in strength with only a minor trade-off in elongation. This establishes TRC as a superior industrial route for high-performance aluminum sheets, offering a promising industrial route, delivering substantial improvements in both strength and ductility over conventional casting methods.

1. Introduction

Al-Cu-Mg alloy has advantages such as high temperature resistance, high specific strength, creep resistance, oxidation resistance, and good processing performance. It is expected to partially replace titanium alloys used in 300~400 °C heat-resistant aluminum alloys [1,2]. In recent years, in order to further improve the high-temperature mechanical properties of Al-Cu-Mg alloys, the microstructure and mechanical properties of the alloys have been altered by microalloying, compositing, and process improvement, and certain research progress has been made [3,4,5]. Among these, 2139 aluminum alloy, a new high Cu/Mg ratio alloy developed by Alcan, has good damage tolerance properties and still exhibits high fracture toughness and creep resistance with low strength damage after thermal exposure at 200 °C [6]. At the engineering application level, 2139 aluminum alloy has been utilized in weight-reduction designs for armored vehicle structures and aerospace components due to its balanced strength-toughness ratio and ballistic damage resistance. Sabry demonstrated through the friction stir welding of TiB2/Al2O3-reinforced Al6061-Al6082 alloys that ceramic particle reinforcement can simultaneously improve both strength and tribological performance in dissimilar alloys, offering valuable insights for strengthening strategies applicable to 2139 alloy in high-performance aerospace and armored vehicle applications [7]. Third-generation Al-Cu-Li alloys, enhanced by the T1 (Al2CuLi) phase and featuring high specific stiffness, are employed in critical components such as wing skins, wall panels, and stiffeners. This achieves 5–15% structural weight reduction while improving fatigue and damage tolerance [8,9].

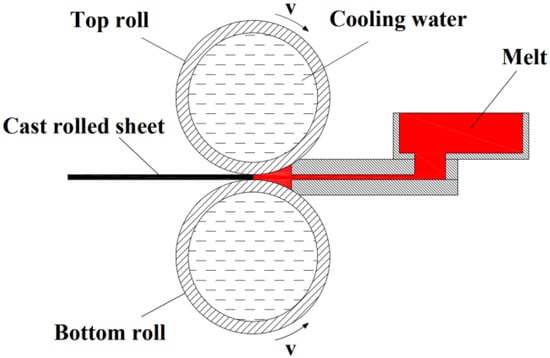

Twin-roll casting (TRC) is a short-flow, low-cost molding method, which ensures uniform composition and structure refinement and greatly improves the mechanical properties of the strips compared to the traditional preparation process [10,11]. TRC is a combination of casting and rolling to produce strips by pouring the molten metal directly onto water-cooled rolls [12,13].

The process involves rapid solidification through casting rolls, achieving cooling rates 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than conventional direct-chill casting. This high cooling rate, combined with enhanced solid solubility, promotes the formation of a supersaturated solid solution, which is crucial for subsequent precipitation strengthening. Li Shiju et al. successfully produced AA2099 aluminum-lithium alloy plates using a TRC experimental platform and optimized the corresponding process parameters. Similarly, Sabry demonstrated through friction stir welding of SiCp-reinforced AZ31C magnesium alloy that advanced solid-state forming processes can achieve grain refinement and uniform distribution of reinforcement phases via parameter optimization [14], significantly improving mechanical properties—providing a valuable reference for microstructural regulation of 2139 alloy via the TRC process [15]. Compared with traditional casting, TRC also refines eutectic phases and introduces a high density of dislocations into the alloy matrix.

Although TRC has the advantages of a simple production process, short production cycle, high yield, and high production efficiency, it mainly produces some low-alloy aluminum alloys with a narrow crystallization temperature range in the 1xxx series, 3xxx series, and 8xxx series [16]. For alloys with a wide liquid-solid zone, it is difficult to form sheets in a rapidly solidifying environment, requiring lower casting and rolling speeds and increased cooling intensity [17]. In this study, 2139 aluminum alloy sheets with wide solidification intervals were successfully produced by a TRC process for the first time. In order to investigate the structure and properties of the TRC samples, conventional sheets were also produced by an MC process, and the effects of the rolling heat treatment process on the structure and mechanical properties of the two sheets were discussed. In addition, the mechanical properties of the TRC sheets in the T8 state were also explored. Therefore, this study aims to compare 2139 alloy sheets produced via the TRC and MC processes, focusing on exploring the feasibility of the TRC process for industrial applications in high-performance aluminum alloy sheets. The research outcomes are expected to provide a theoretical basis and technical guidance for the industrial production of 2139 alloy sheets using the TRC process.

2. Materials and Methods

The chemical composition of the 2139 aluminum alloy used in this study is shown in Table 1, and the raw materials produced by the alloy include industrially pure Al ingot (99.9%), Al-50% Cu, pure Mg ingot (99.9%), Al-10% Mn, pure silver grains (99.9%), and pure Zn ingot (99.9%) intermediate alloys.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of 2139 alloy (wt%).

A schematic diagram of the TRC process is shown in Figure 1. In the melting process, pure aluminum ingots were first placed in TiO2-coated stainless steel crucibles and heated to 750 °C, and then Al-50%Cu and Al-10%Mn intermediate alloys were added. The melt is held at 720 °C for 1 h to ensure that the intermediate alloy is fully dissolved, and then pure magnesium ingots, zinc ingots, and silver grains are carefully pressed into the melt in sequence, followed by degassing and slag removal. Once the alloy was fully melted and held for 30 min, the casting and rolling machine was activated. Research by Sabry on friction stir welding of dissimilar AA2024 and A356-T6 alloys indicates that process parameters significantly affect mechanical properties by regulating temperature distribution and recrystallization behavior in the weld zone. Based on this insight, the TRC rolling speed in this study was controlled at 0.9 m/min to balance cooling efficiency and microstructural uniformity [18]. When the melt temperature was steadily lowered to 690 °C, the melt was poured into the flow channels and nozzles made of heat-resistant material of MgO, which then flowed into the roll seams. The width of the nozzle was 200 mm, and 6 mm thick sheets were produced.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of TRC process.

A cutting of 10 mm × 8 mm × 6 mm was taken as a specimen, which was then ground and polished in different states for microstructure observation. An OLYMPUSBX53M optical microscope (OM) (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan) and a scanning electron microscope SSX-550 (SEM) equipped with an X-ray spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) were used to observe the microstructure, and electron back-scattering diffraction (EBSD) using a Zeiss Ultra-55 SEM (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to analyze the grain distribution of the samples. The EBSD samples were prepared using electrolytic polishing, and the electrolytic polishing solution. The electrolytic polishing solution was a 10% perchloric acid alcohol solution (v/v), the voltage was 25 V, the time was 30 s, and the EBSD scanning step was 0.6 µm. In analyzing the EBSD results, orientation error angles of 2–15° and greater than 15° were defined as low- and high-angle boundaries, respectively. Orientation error angles smaller than 2° were eliminated to avoid errors arising from the sample surface and experimental polishing.

The cast slabs were homogenized at 510 °C for 24 h, then heated to 460 °C for 1 h. The slabs, initially 8 mm thick, were hot-rolled to 2.0 mm, with a 75% deformation. Since the recrystallization temperature for 2xxx aluminum alloys is typically 400–450 °C, 440 °C was selected to promote recovery and controlled recrystallization, relieving residual stresses and preventing excessive grain growth [19]. After heating to 440 °C for 1 h, the slabs were air-cooled and cold-rolled to 1.5 mm with 25% deformation.

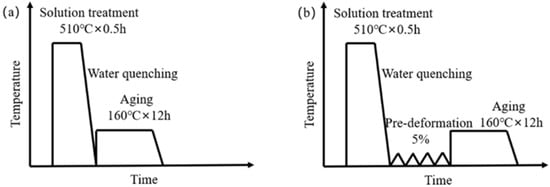

After cold rolling, the samples were solution-treated at 510 °C for 0.5 h, quenched, and aged at 160 °C for 12 h (T6 state), as shown in Figure 2a. To investigate the effect of different heat treatments, a 5% pre-stretch deformation was applied before aging, followed by homogenizing heat treatment at 160 °C for 12 h to achieve the T8 state (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Heat treatment process diagram (single-stage aging): (a) MC/TRC sample T6; (b) TRC sample T8.

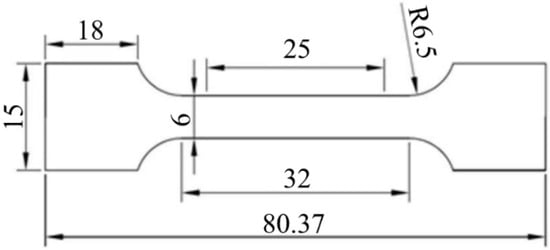

Tensile experiments were carried out on samples in different states, and the dimensions of the specimen are shown in Figure 3. The normal temperature tensile experiments were carried out using a 100 kN tensile machine, model INSTRON-4206 (Instron, Norwood, United States). The tensile rate of 1 mm/min was adopted in accordance with ASTM E8/E8M standard [20] for metallic materials, ensuring consistent strain rate conditions for accurate comparison of mechanical properties. Additionally, three standard tensile specimens were taken from each group, and the average value of each group was used as the final result. The same shape and size of the tensile specimens at high temperature were also used; the tensile temperature was set by the supporting high temperature furnace, the hydraulic pressure was set at 300 MPa, the tensile strain rate was 2 × 10−4 s−1, the same tensile rate as that of the normal temperature tensile experiments was used, and the values of the tensile strength were read directly from the tensile machine, while the values of the yield strength were obtained by the load-displacement curves recorded by the tensile machine through the reference standard-displacement curve.

Figure 3.

Size specification of tensile specimen.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. As-Cast Microstructures

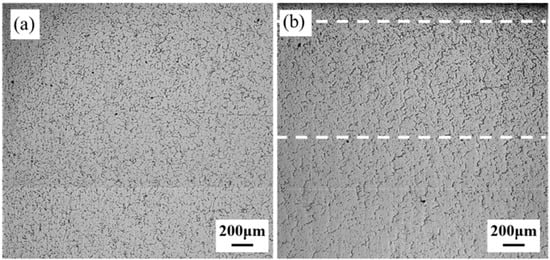

The as-cast microstructure of the experimental alloy produced by different processes is shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that there are reticulated intermetallic compounds in the structure of aluminum alloys cast in conventional molds, as well as a small number of porosity and microcrack defects (Figure 4a). The intermetallic compounds in the microstructure of the aluminum alloy produced by the TRC process show obvious bands, which generally run through the whole thickness direction, and the density and width gradually decrease from the surface to the center, and basically no pores and micro-cracks are observed. According to the analysis, the melt is easy to be sucked in during MC, resulting in volume shrinkage and defects, such as pores and microcracks. The TRC is a process that integrates continuous casting and rolling deformation. During the solidification process, the cast-rolled plate is always tightly rolled and subjected to the rolling force to compensate for the shrinkage and porosity generated during the casting process, thereby obtaining a dense plate without pores. Therefore, the plate prepared by the TRC process has a denser dendrite structure.

Figure 4.

Microstructure of 2139 aluminum alloy prepared under different process conditions: (a) MC; (b) TRC.

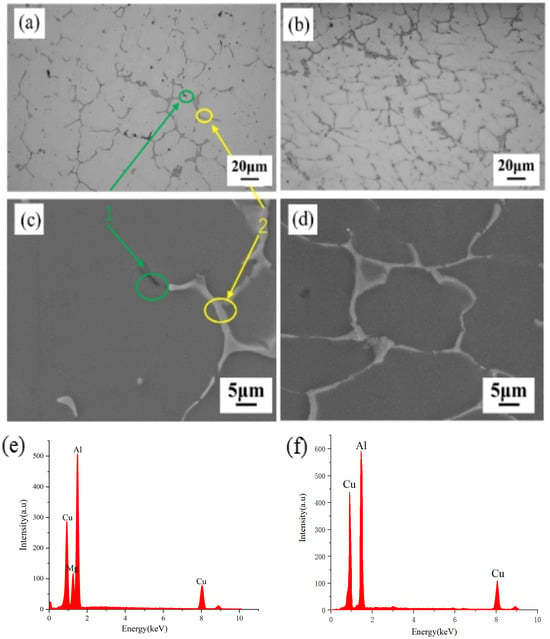

The intermetallic compounds in the sheets produced by different processes are shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the microstructure of the sheets produced by the MC process consists of an aluminum matrix and a large number of intermetallic compounds distributed along the boundary of the dendrite walls (Figure 5a). The grains of the sheets produced by the TRC process have obvious rolling microstructure characteristics, accompanied by a certain inclination angle (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Microscopic morphology of 2139 aluminum alloy produced by different processes: (a,c) MC; (b,d) TRC-surface layer; (e) the EDS image of MC; (f) the EDS image of TRC.

Figure 5c,d show the detailed information of intermetallic compounds in the plates produced by the two casting processes, respectively. There are two different intermetallic compounds at the dendrite interface. The dark region indicated by the green ellipse in Figure 5c is a pit left by the detachment of an Al2CuMg (S-phase) particle during sample preparation, not the phase itself. In contrast, the bright intermetallic compound circled in the yellow ellipse is the Al2Cu phase. This distinction is definitively established by the EDS point analysis presented in (Figure 5e,f). The key evidence is the presence of magnesium in the EDS spectra corresponding to the S-phase regions and its absence in the spectra from the Al2Cu particles. The measured atomic percentages of Cu and Mg in the S-phase correspond to the Al2CuMg stoichiometry, whereas the high Cu content and lack of Mg in the bright particles are characteristic of the Al2Cu phase. These phases are continuously distributed on the dendrite boundaries and grain boundaries, which severely impairs the strength and toughness of the alloy. Therefore, these intermetallic compounds at dendrite boundaries and grain boundaries need to be dissolved into the matrix by homogenizing heat treatment to achieve a uniform distribution of the elements.

3.2. Microstructures After Homogenization

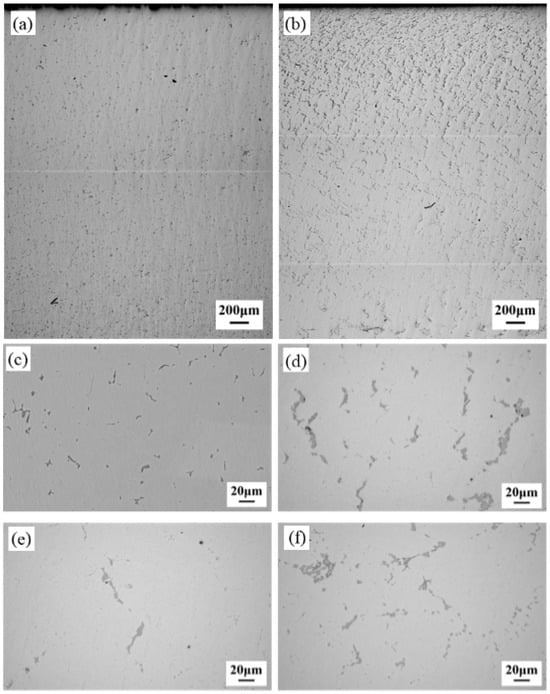

The structure and morphology of the sheet after holding at 510 °C for 24h are shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that most of the intermetallic compounds undergo dissolution after the homogenization heat treatment, and the reticulated dendritic structure disappears (Figure 6a,b). Compared to the MC samples, the changes in the 1/4 layer of the TRC samples are more significant due to the lower content of eutectic phases (Figure 6c,e).

Figure 6.

The microstructures of 2139 alloy after homogenization: (a,c) MC; (b) TRC; (d) TRC-surface layer; (e) TRC-1/4 layer; (f) TRC-central layer.

Since the content of intermetallic compounds under the TRC process varies from the surface layer to the center layer, the surface, 1/4, and middle layers were partially enlarged (Figure 6d–f). It can be seen that the intracrystalline precipitated phases of the samples in MC after homogenization heat treatment are basically dissolved back, and very few precipitated phases that are not dissolved back remain on the grain boundaries. However, there is a small amount of fragmented intermetallic compounds, a large number of coarse banded intermetallic compounds and intermediate bulk intermetallic compounds, and a large number of insoluble phases (S-Al2CuMg and Fe-rich phases) at the grain boundaries of the TRC process aluminum alloy after homogenization heat treatment, which prolongs the dissolution time of the crystal phase. The presence of a small amount of fragmented intermetallic compounds is attributed to localized strain concentration during the TRC, which promotes fragmentation but insufficiently dissolves these phases due to their initial coarse size and low solubility. In general, the dissolution of intermetallic compounds in the TRC samples after homogenization was not as good as that of MC, which is due to the initial large-sized intermetallic particles in the as-cast condition of the TRC sample.

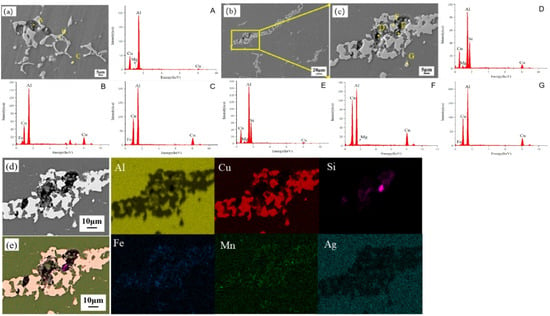

The content and distribution of residual crystalline phases of the sheets produced by different processes after homogenization heat treatment are shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that under the same homogenization state, the different preparation processes resulted in certain differences in the type, content, and distribution of residual crystalline phases.

Figure 7.

SEM image and EDS spectroscopy analysis and scanning results of tissue elements of 2139 alloy after homogenization: (a) MC; (b,c) TRC; (d,e) morphology and element distribution diagram of the insoluble second phase.

Typically, homogenizing heat treatment can effectively dissolve the eutectic structure, improve the micro-element distribution of the alloy, reduce the content of residual crystalline phases, and the residual crystalline phases become finer and more discretely distributed. This is because homogenization heat treatment can promote the diffusion of solute atoms from the eutectic phase into the aluminum matrix, thereby reducing compositional heterogeneity and facilitating the dissolution of intermetallic compounds, which is supported by classical diffusion theory and previous studies [21]. However, due to the TRC process characteristics that bring about coarse banded intergranular intermetallic compounds and central massive intermetallic compounds, which prolong the dissolution time of the crystalline phase, and even through a longer period of homogenizing heat treatment, a small amount of fragmented intermetallic compounds were still left behind which were difficult to be completely dissolved, so there were a large number of insoluble S-Al2CuMg and Fe-rich phases existed in the cast and rolled samples (Figure 7b,c).

The residual crystalline phases in the TRC samples are mainly distributed in the original banded intergranular intermetallic compounds and the intermediate layer of massive intermetallic compounds, and the distribution is relatively concentrated. Table 2 and Figure 7d,e demonstrate the EDS spectroscopy analysis and scanning results of the 2139 alloy after homogenization, with the complex residual second phase dominated by the elements Al, Cu, Si, Fe, and Mn. The solubility of Mn and Fe in the aluminum matrix is much lower than that of Cu, so it is easier to precipitate from the melt to form second-phase particles rich in Mn and Fe phases. As solidification proceeds, the melt temperature gradually decreases, and Cu atoms are gradually deposited on these cores, eventually forming the AlCuFe and AlCuFeMn phases. These Mn- and Fe-rich phases usually have a high melting point and can only be dissolved at very high temperatures, making it difficult to eliminate them completely by homogenization.

Table 2.

EDS spectroscopy analysis of residual phase in homogenized 2139 alloy.

3.3. Microstructure After Rolling and Solution Treatment

The microstructure of MC and TRC samples after hot rolling, cold rolling, and solution treatment is shown in Figure 8. After cold rolling, and the second phase is aligned along the rolling direction after cold rolling, forming a second phase containing a large number of stripes. Some of the larger-sized phases were significantly broken, while some of the insoluble and incompletely dissolved phases showed relatively good ductility and were distributed in the rolling direction. With the partial dissolution of residual crystalline phases by the homogenization heat treatment process, the distribution of residual crystalline phases after cold rolling is more dispersed, and the aggregation region of coarse crystalline phases is significantly reduced.

Figure 8.

Evolution of crystalline phase of 2139 alloy during cold rolling and solution treatment: (a,b) cold-rolled state of MC; (c,d) cold-rolled state of TRC; (e,f) solid solution state of MC; (g,h) solid solution state of TRC.

After a short period of solid solution treatment, most of the precipitated second phases in both MC and TRC samples have been dissolved into the α(Al) matrix; only a small amount of coarse undissolved phase exists. The shape and size are only slightly reduced, but the distribution state of the cold-rolled state is basically maintained. The results of point scanning at different positions are shown in Table 3. It can be seen from the Cu content that after solution treatment, the Al2Cu phase in the crystal is re-dissolved into the Al matrix, and the distribution of the residual crystalline phase does not change significantly. The slight reduction in the shape and size of the second phase particles after solution treatment is due to their high thermal stability and the short duration of the treatment, which limits Ostwald ripening and coalescence [22].

Table 3.

EDS spectroscopy analysis of crystalline phase of 2139 alloy during cold rolling and solution treatment.

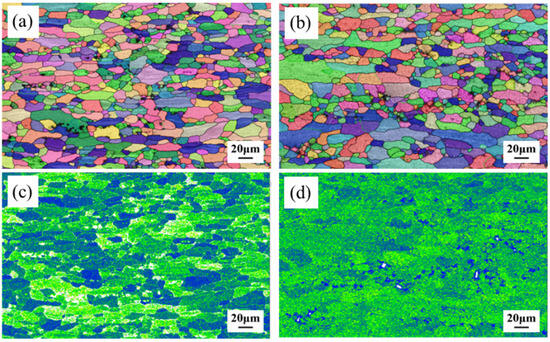

Figure 9a,b shows that the grain size of the MC sample is 9.52 μm, and the grain size of the TRC sample is 9.33 μm, which is significantly reduced compared to the as-cast state. EBSD samples were mechanically ground and polished in accordance with standard metallographic preparation procedures ASTM E3 [23] and ISO 9042 [24], followed by appropriate surface finishing for electron backscatter diffraction analysis, ensuring reliable grain size and recrystallization characterization. Compared with the core of the cast-rolled sheet, the surface grain of the cast-rolled sheet is finer, showing the characteristics of gradient distribution. In the cold rolling process, similar to the casting and rolling process, the surface grain is subjected to greater casting and rolling force, greater plastic deformation occurs, and the accumulation of more distortion energy. According to the PSN effect, a large number of second-phase particles (such as residual crystalline phase) on the surface promotes the recrystallization nucleation mechanism of PSN and reduces the grain size. Therefore, in addition to the grain size distribution characteristics of the genetic cold-rolled TRC sample, the gradient distribution of grain size is also affected by the degree of strain and the gradient of element distribution. Due to the initial accumulation of strain energy during the TRC process, the recrystallization phenomenon with large deformation is more concentrated.

Figure 9.

Observation of the solid solution microstructure and EBSD of 2139 alloy. (a) Grain structure dis-tribution of MC; (b) grain structure distribution of TRC; (c) KAM diagram of MC; (d) KAM dia-gram of TRC.

In addition, fewer low-angle and medium-angle misorientation grain boundaries can be found in both MC and TRC samples, indicating that a large number of substructures are reorganized during the solid solution process. The large angle misorientation is sparsely distributed inside the grains and is higher near the grain boundaries (Figure 9c,d). The larger the KAM value in the diagram indicates the higher the strain degree. The unidentified white part is mainly the distribution area of the residual crystalline phase. Compared with other deformation areas, the strain is concentrated in all areas where the distribution of the residual crystalline phase is concentrated. The strain concentration in regions with residual crystalline phases is attributed to the mismatch in deformation behavior between the brittle intermetallic particles and the ductile aluminum matrix, leading to stress localization and inhibited recrystallization in these areas [25].

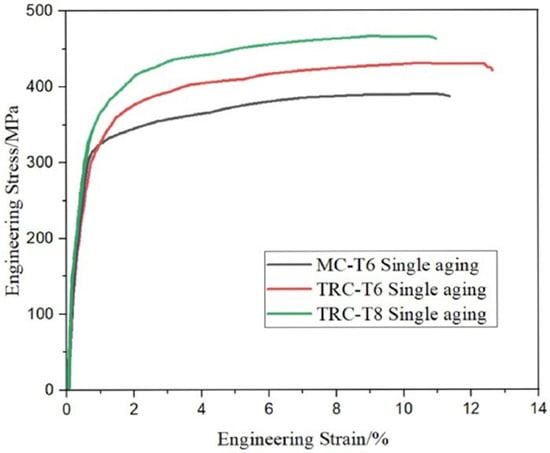

3.4. Mechanical Properties of the Sheets After Aging Heat Treatment

Normal temperature tensile experiments were conducted on the sheets after aging heat treatment, and the results are shown in Figure 10. It can be seen that at the beginning of the tensile experiment, the stress increases sharply until the peak stress is reached. After that, the stress decreases slowly until it breaks at the end of the tensile experiment. The yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation of the MC sample are 309.2 MPa, 390.0 MPa, and 11.4% after T6 (single-stage aging) treatment, respectively. The yield strength and tensile strength of the TRC sample were 354.2 MPa and 430.4 MPa, which were 10.3% higher than those of the MC sample, and the elongation of the TRC sample (12.6%) was 10.5% greater than that of the MC sample (11.4%). The tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation of the TRC specimens were increased to 385.7 MPa, 464.9 MPa, and 11.0%, respectively, after the T8 (single-stage aging) treatment. Compared with T6 (single-stage aging), the tensile strength of the alloy increased by 76.5 MPa and the yield strength by 74.9 MPa. Compared with the T6 heat treatment process, the T8 heat treatment process, which introduces 5% pre-stretch deformation before single-stage aging at 160 °C/12 h, substantially improves the strength of 2139 aluminum alloy sheet without losing too much plasticity, and enables the alloy sheet to reach a more optimal state.

Figure 10.

Tensile curves of 2139 alloy under different aging heat treatment states.

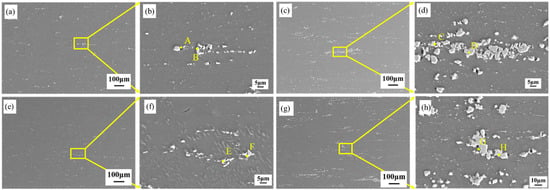

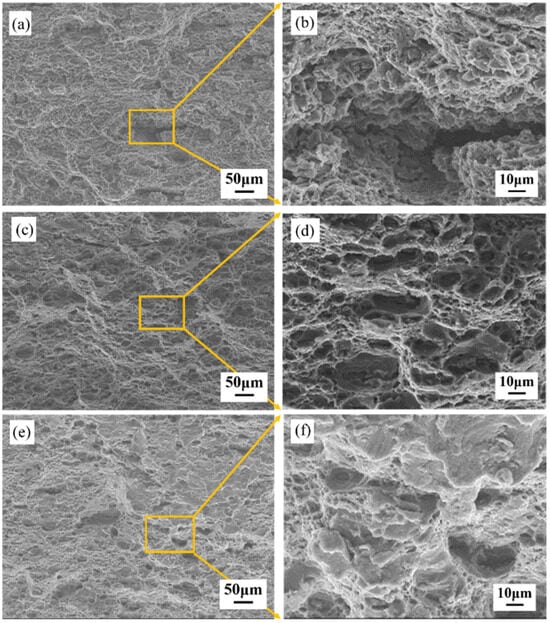

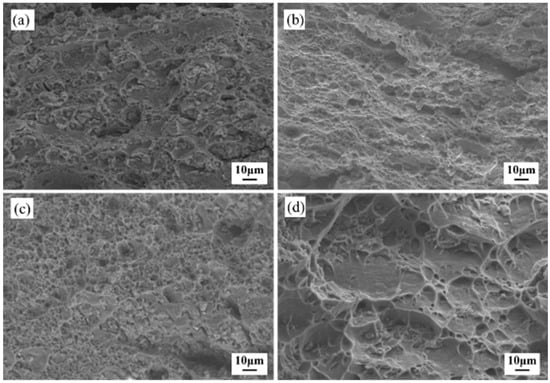

The tensile fracture morphology of 2139 aluminum alloy prepared under different process conditions in different heat treatment states is given in Figure 11. The tensile fracture morphology of 2139 aluminum alloy produced by the MC process after T6 (single-stage aging) treatment has fewer dimples and a diffuse distribution, which is a mixed mode of ductile fracture and brittle fracture (Figure 11a,b). The tensile fracture morphology of the 2139 aluminum alloy produced by the TRC process after T6 (single-stage aging) treatment, compared with the MC process, the number of dimples increases significantly, but the size of the dimples is different, the size is uneven, the amount is large, and the fractures are mainly ductile fractures (Figure 11c,d). The significant increase in dimple number in TRC-T6 samples compared to MC is attributed to the finer and more uniformly distributed Ω phases and the higher dislocation density, which promote homogeneous plastic deformation and micro-void coalescence. Judging from the detailed fracture morphology diagram, the TRC samples underwent a large plastic deformation before fracture, and the alloy was highly plasticized. The tensile fracture morphology of 2139 aluminum alloy produced by the TRC process after T8 aging treatment, where larger areas of tear edges and delamination are observed, and the alloy has the worst plasticity (Figure 11e,f).

Figure 11.

Tensile fracture morphology of 2139 alloy under different heat treatment states: (a,b) T6 (single-stage aging) of MC sample; (c,d) T6 (single-stage aging) of TRC sample; (e,f) T8 (single-stage aging) of TRC sample.

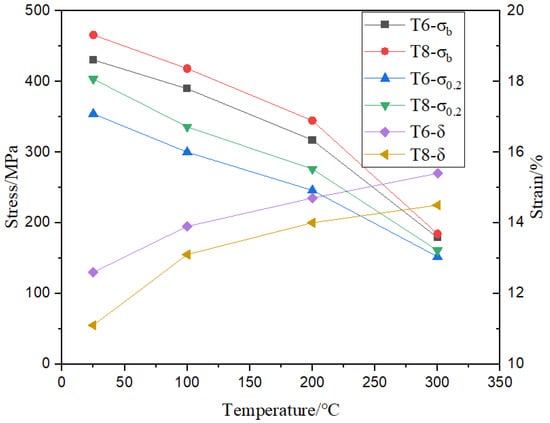

In order to investigate the high-temperature mechanical properties of TRC sheets, tensile experiments at different temperatures were carried out on specimens in T6 and T8 states, and the results are shown in Figure 12. It can be seen that the strength of the alloy decreases as the temperature increases. At 200 °C, the strength in the T6 state reaches 74% of the normal temperature strength, also 74% in the T8 state, and this reduction is further accelerated when the temperature exceeds 200 °C. At 300 °C, the strength reaches 42% and 40% of that at normal temperature, corresponding to the T6 and T8 states, respectively. In the T8 state, the high-temperature tensile and yield strengths of the alloy are higher than in the T6 state, but the elongation is lower. Therefore, 2139 aluminum alloy shows good performance at high temperatures of about 200 °C.

Figure 12.

High-temperature mechanical properties of 2139 alloy under T6 and T8 states.

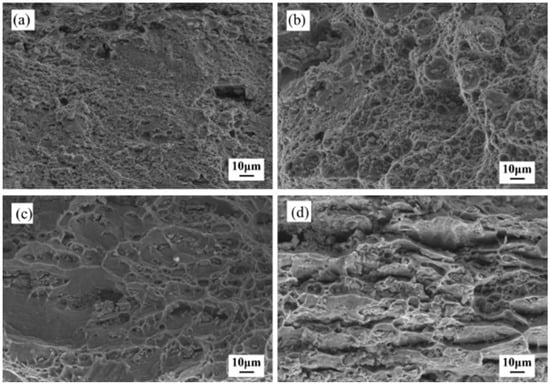

The fracture morphology of tensile specimens of 2139 alloy in the T6 state at 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, and 300 °C is shown in Figure 13. It can be found that the normal temperature fracture of 2139-T6 alloy shows a mixed fracture with a relatively flat cross-section (Figure 13a). Despite the presence of a small number of dimples, brittle fracture predominates, which is consistent with the results of the mechanical property test. As the tensile temperature increases to 100 °C, the tensile fracture morphology of the 2139 aluminum alloy T6 state shows a significant increase in the number of dimples and an increase in the area of the dimples compared to normal temperature tensile (Figure 13b). As the temperature reaches 200 °C, the dimples become deeper at this time, and the area of ductile fracture increases significantly, which signifies that ductile fracture is dominant (Figure 13c). As the tensile temperature was further increased, the number of dimples decreased significantly, but the size of the fracture dimples increased significantly to become deeper. At 300 °C, the high-temperature fracture morphology of the T6 state of 2139 aluminum alloy shows a typical dimple-type through-crystal fracture, which is consistent with the high-temperature mechanical properties of the alloy (Figure 13d).

Figure 13.

High-temperature tensile fracture morphology of T6 state alloy: (a) normal temperature; (b) 100 °C; (c) 200 °C; (d) 300 °C.

The high-temperature tensile fracture morphology of 2139 aluminum alloy T8 state at different temperatures is shown in Figure 14. Compared to the T6 state, the area of the fracture region increases at normal temperature, showing a mixed type of fracture. This may be attributed to the large number of dislocations introduced in the pre-deformation treatment, leading to the deformation strengthening effect (Figure 14a). The tensile fracture morphology of the T8 state of 2139 aluminum alloy at 100 °C, compared with the situation at normal temperature, the size of the dimple is smaller, the distribution of the dimple is more uniform, and the ductile fracture area is larger (Figure 14b). With the increase in tensile temperature, the dimples in the tensile fracture morphology of 2139-T8 alloy become deeper and larger, and the area of ductile fracture expands (Figure 14c). When the tensile temperature reaches 300 °C, the morphology of the high-temperature tensile fracture of 2139 aluminum alloy presents a dimple-type penetrating fracture, which is consistent with the change trend of high-temperature tensile mechanical properties (Figure 14d).

Figure 14.

High-temperature tensile fracture morphology of T8 state alloy: (a) normal temperature; (b) 100 °C; (c) 200 °C; (d) 300 °C.

The evolution of the high-temperature fracture morphology is directly governed by thermally activated diffusion and dynamic recovery mechanisms. As the temperature rises beyond 200 °C, the enhanced atomic diffusion promotes coarsening of the Ω phase, reducing its pinning effectiveness, while simultaneously accelerating dislocation climb and rearrangement through dynamic recovery. These combined processes lead to overall material softening and an increase in uniform plastic deformation capability, which is clearly reflected in the fracture surfaces as enlarged dimple size, greater dimple depth, and expanded dimple area, as shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14. The accelerated decline in strength observed above 200 °C corresponds to the growing dominance of dynamic recovery in the high-temperature softening behavior.

The T8 condition, with its higher dislocation density resulting from pre-deformation, retains greater strength at elevated temperatures due to its increased stored dislocation energy. However, this same high dislocation density also accelerates diffusion-assisted dislocation annihilation, leading to a more noticeable reduction in high-temperature ductility compared to the T6 condition. This mechanistic difference explains why localized tearing features appear earlier in the fracture morphology of T8 samples, as evidenced in Figure 11e,f.

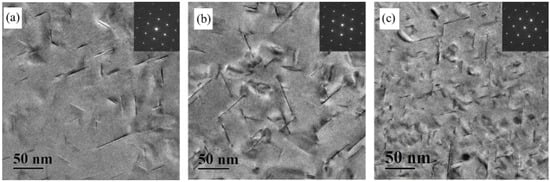

3.5. Analysis of Precipitated Phases After Aging Heat Treatment

Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) technology, the distribution of precipitated phases in two alloys prepared by different processes was characterized in both T6 and T8 conditions. Figure 15a,b show the TEM images of 2139 aluminum alloy produced by MC and TRC under two different process conditions after aging treatment, and the <110>Al direction is the direction of electron incidence. After aging at 160 ° C for 12 h and T6 treatment, a small amount of needle-like Ω (Al2Cu) phases with a large diameter and a length of about 20–80 nm can be observed in the MC sample, and the size distribution is not uniform, accompanied by a certain degree of coarsening (Figure 15a). Compared with the MC sample, the TRC sample was aged at 160 °C for 12 h and then subjected to T6 treatment. The number of Ω phases in the alloy increased significantly, the size increased slightly, the size distribution was relatively uniform, and the coarsening phenomenon was very rare (Figure 15b). The main reason is that the solid solubility in the TRC samples is high, and the phase transition driving force of the precipitated second phase in the aging process is large, which can reduce the critical nucleus size of the precipitated phase and increase the nucleation rate, thus increasing the number of precipitated phases. Therefore, after the same heat treatment, there are more and finer Ω phases precipitated in the TRC sheets, which improves the aging strengthening effect, and the strength of the TRC sheets is also improved. The microstructural distinction is governed by synergistic kinetic and thermodynamic factors. The high dislocation density in TRC samples provides potent heterogeneous nucleation sites for the Ω phase, lowering the energy barrier for its precipitation and refining its distribution. Meanwhile, the rapid solidification during TRC yields a highly supersaturated solid solution, which enhances the thermodynamic driving force for Ω-phase nucleation and simultaneously suppresses the formation of coarse equilibrium phases like Al2Cu. This multi-mechanism enhancement parallels the approach reported by Scary et al., where 5wt% SiCp reinforcement was found to optimally improve strength, ductility, and corrosion resistance in aluminum composites through a synergistic combination of Orowan strengthening, grain refinement, and intermetallic distribution optimization [26].

Figure 15.

Microstructure of the Ω phase in MC and TRC samples after aging heat treatment: (a) T6 (single-stage aging) of MC sample; (b) T6 (single-stage aging) of TRC sample; (c) T8 (single-stage aging) of TRC sample.

Moreover, a certain amount of dislocations and dislocation tangles can be found inside the grains in the TRC samples, which is due to the deformation storage effect of the TRC process itself.

After pre-stretching the TRC sample with a deformation of 5% and then T8 treatment at 160 °C for 12 h, a large number of dislocations and dislocation tangles appeared in the alloy. The Ω phases in the alloy became fine, and the density increased significantly, and the number reached a maximum. A large area of uniform, fine, and dispersed Ω phases appeared, and then the long diameter of Ω phases became shorter, and the length further narrowed, which was about 15–50 nm (Figure 15c). The pre-stretching deformation in the T8 treatment further multiplied dislocations and created dislocation tangles. These defects served as additional nucleation sites and accelerated solute atom diffusion via pipe diffusion mechanisms. This synergistic effect of enhanced nucleation and accelerated diffusion led to the observed ultra-fine and densely distributed Ω phases in the T8 state, contributing to the peak strength achieved.

In the Al–Cu–Mg alloy system, previous studies have shown that Mg promotes Ω-phase precipitation, while Ag further modifies its precipitation kinetics by assisting GP-zone formation and solute clustering [21,27]. The Ω-phase behavior observed in the TRC-processed 2139 alloy in this work—namely its higher number density and finer, more uniform distribution in the T6 and T8 states—was consistent with these reported Mg/Ag-assisted precipitation mechanisms.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the use of the twin-roll casting (TRC) process for producing 2139 aluminum alloy sheets and compares the resulting microstructure and mechanical properties to those produced by the mold casting (MC) process. The main findings are as follows:

- (1)

- The TRC process produces a microstructure where the intermetallic compounds, particularly Al2Cu and Al2CuMg phases, are more concentrated in the center and decrease in density and width from the surface inward. This leads to improved phase distribution and suggests that TRC enhances material homogeneity compared to MC.

- (2)

- After rolling and solid solution treatment, the residual crystalline phases (mainly undissolved intermetallic compounds) in the MC samples were evenly distributed, while the TRC samples showed localized recrystallization, particularly within second-phase and shear zones. This localized recrystallized-grain formation contributed to improved strength and ductility, indicating that TRC allowed for more controlled microstructural evolution.

- (3)

- Mechanical testing revealed that the TRC samples in the T6 state show a 10.3% higher yield strength and 10.5% higher tensile strength compared to the MC samples, with an elongation of 12.6%, which was 10.5% higher than that of the MC samples. These improvements in strength and elongation demonstrated the effectiveness of TRC in enhancing the alloy’s mechanical properties, especially at normal temperatures.

- (4)

- The TRC-T6 sheets exhibited a significant increase in the number of Ω phases, with a more uniform distribution and minimal coarsening. After T8 heat treatment, the Ω phase became finer and more densely distributed. This enhanced phase distribution contributed to a further increase in strength and ductility, showing that TRC could optimize phase evolution for improved mechanical performance.

5. Challenges and Perspectives

In this study, we successfully applied the twin-roll casting (TRC) process to produce 2139 aluminum alloy sheets, marking a significant innovation in the production of high-performance aluminum alloys. The application of TRC allowed for remarkable improvements in both microstructure and mechanical properties, setting the stage for future advancements. However, there were notable challenges that needed to be addressed. The dissolution of iron-rich phases remained difficult, which affected the alloy’s overall performance. Additionally, scaling up the TRC process for industrial production posed challenges, particularly regarding heat dissipation and material flow control, which were critical for maintaining consistent quality at larger scales. Future research will focus on optimizing the TRC process through advanced simulation tools, such as finite element analysis (FEA) and computational fluid dynamics (CFD), to refine parameters like cooling rates and roll speeds, ensuring better control over the alloy’s properties. Overcoming these limitations and integrating simulation-driven optimization with large-scale adaptations will be essential to making TRC a widely adopted method for producing high-performance aluminum alloys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and H.T.; methodology, Z.L. and Y.W.; validation, Z.L., Y.W., and Q.C.; investigation, Q.C. and L.M.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. and Q.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., Z.Y., and X.Q.; visualization, Y.W. and Y.X.; supervision, Y.L., X.Q., and X.L.; project administration, H.T.; funding acquisition, H.T. and X.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangxi Science and Technology Major Program (AA23073019), the Special Fund for Science and Technology Development of Guangxi (AD25069078), the Open Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Featured Metal Materials and Life-cycle Safety for Composite Structures (MMCS2023OF09, MMCS2023OF07), the Major Special Project of Science and Technology in Nanning (20231037), the Yanshan University Basic Innovation Research and Cultivation Project (2022LGQN015), and the Open Research Fund from the State Key Laboratory of Rolling and Automation, Northeastern University (2023RALKFKT004). Thanks to the Multi-disciplinary Integrated Innovation Experimental Teaching Center for Resources, Environment and Materials at Guangxi University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yong Li was employed by the company Guangxi Advanced Aluminum Processing Innovation Center Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Das, S.K.; Bye, R.L.; Gilman, P.S. Large scale manufacturing of rapidly solidified aluminum alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1991, 134, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.I.H. Advanced aluminum alloys for high temperature structural applications. Ind. Heat. 1988, 55, 31–34, 0019-8374. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, K.; Chen, J.W.; Ran, H.W.; Deng, P.; Tang, C.L.; Mo, W.F.; Ouyang, Z.Q.; Wu, X.K.; Luo, B.H.; Bai, Z.H. Effect of V additions on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Cu-Mg-Ag alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Liu, Z.; Bai, S.; Wang, J.; Cao, J. Effects of yttrium additions on microstructures and mechanical properties of cast Al-Cu-Mg-Ag alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 870, 159435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; An, Z.; Hage, F.S.; Wang, H.; Xie, P.; Jin, S.; Ramasse, Q.M.; Sha, G. Solute clustering and precipitation in an Al-Cu-Mg-Ag-Si model alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 760, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, T. Recently-developed aluminum solutions for aerospace applications. In Aluminum Alloys 2006, Pts 1 and 2: Research Through Innovation and Technology; Poole, W.J., Wells, M.A., Lloyd, D.J., Eds.; Materials Science Forum: Baech, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 519–521, pp. 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, I.; El-Deeb, M.S. Enhanced structural integrity and tribological performance of Al6061–Al6082 alloys reinforced with TiB2 and Al2O3 via friction stir welding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja, R.J.; Liu, J. The Evolution of Al-Li Base Products for Aerospace and Space Applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2012, 43, 3325–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Kyeremeh, F.; Pratesa, Y.; Shen, X.; Song, W.; Raffeis, I.; Vroomen, U.; Zander, D.; Bührig-Polaczek, A. Preheating Influence on the Precipitation Microstructure, Mechanical and Corrosive Properties of Additively Built Al–Cu–Li Alloy Contrasted with Conventional (T83) Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-T.; Wang, B.-Y.; Wang, C.; Zha, M.; Liu, G.-J.; Yang, Z.-Z.; Wang, J.-G.; Li, J.-H.; Wang, H.-Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Mg-Si alloy fabricated by a short process based on sub-rapid solidification. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Mo, Y.-T.; Wang, C.; Cheng, T.; Ivasishin, O.; Wang, H.-Y. High strength-ductility synergy induced by sub-rapid solidification in twin-roll cast Al-Mg-Si alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuser, M. Schaper, Mechanical and Microstructure Characterization of the Hypoeutectic Cast Aluminum Alloy AlSi10Mg Manufactured by the Twin-Roll Casting Process. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, M.; Stirl, M.; Prahl, U. Twin-roll casting defects in light metals. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 19003–19022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, I. Hybrid GRA-TOPSIS optimization of friction stir welding for SiCp-reinforced AZ31C magnesium alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 139, 4457–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, C.; Fu, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, Z. Evolution of microstructure and properties of novel aluminum-lithium alloy with different roll casting process parameters during twin-roll casting. Mater. Charact. 2020, 161, 110145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-G.; Kim, Y.D.; Kim, M.-S. Prediction of Grain Structure and Texture in Twin-Roll Cast Aluminum Alloys Using Cellular Automaton–Finite Element Method. Materials 2025, 18, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B. Theory and Technology of Strip Casting and Rolling; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-7502430962. [Google Scholar]

- Sabry, I. Enhanced strength, ductility, and corrosion resistance of AA6061/AA6082 alloys using Al-SiC matrix reinforcement in dissimilar friction stir welding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 2431–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Hsu, Y.; Chen, M.; Yang, W.; Lee, S. Effects of Heterogenization Treatment on the Hot-Working Temperature and Mechanical Properties of Al-Cu-Mg-Mn-(Zr) Alloys. Materials 2023, 16, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8/E8M-24; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cousland, S.M.; Tate, G.R. Structural changes associated with solid-state reactions in Al–Ag–Mg alloys. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1986, 19, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Y.; Yang, S.-P.; Wang, H.; Zhao, G.-Z. Ostwald Ripening Mechanism and Its Progress in Binary Alloys. Mod. Phys. 2022, 12, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E3-11; Standard Practice for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ISO 9042:2021; Industrial Thermometers—Metal Case Thermometers with Bimetal Sensing Element and Indicator. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Lei, T.; Hessong, E.C.; Shin, J.; Gianola, D.S.; Rupert, T.J. Intermetallic particle heterogeneity controls shear localization in high-strength nanostructured Al alloys. Acta Mater. 2022, 118347, 1359–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, I. Exploring the effect of friction stir welding parameters on the strength of AA2024 and A356-T6 aluminum alloys. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 8, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.P.; Zheng, Z.Q. Independent and combined roles of trace Mg and Ag additions in properties precipitation process and precipitation kinetics of Al-Cu-Li-(Mg)-(Ag)-Zr-Ti alloys. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 4381–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.