Abstract

An investigation of the molecular structure of a series of phenolphthalein derivatives is presented. The X-ray structures of thymolphthalein, 2,5-dimethylphenolphthalein, and 2,6-dimethylphenolphthalein have been determined for the first time. Furthermore, a series of related 3-(4-hydroxy-dialkyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-ones have also been prepared, and X-ray structures obtained. The present study allows for comparison of the structures of substituted phenolphthalein derivatives, with a particular focus on the effect of different alkyl groups on the structures.

1. Introduction

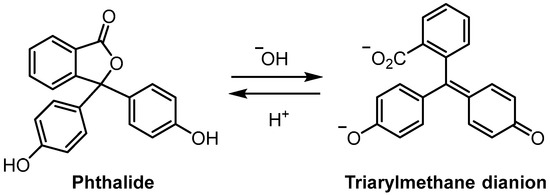

Phenolphthalein (3,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one, 1) and its derivatives are well known to the majority of chemists since these compounds are often used as acid/base indicators in titrimetric analysis [1,2]. Phenolphthaleins are halochromic, changing colour in response to changes in pH. The most notable feature of these compounds is that under basic conditions, the phthalide ring is readily opened to form a quinoidal dianion (Scheme 1) [1,2,3]. The presence of triarylmethane dianions results in strongly coloured solutions, in stark contrast to the colourless phthalide forms. For example, the dianion derived from phenolphthalein is red/pink in basic solution. Recent work has shown that the phthalide form of phenolphthalein can also be converted to the quinoidal dianion form when high hydrostatic pressure is applied to solid samples [4]. This is an example of a mechanochromic process where the increase in pressure results in rehybridisation of the sp3-hybridised spiro carbon atom to an sp2 hybridised carbon atom in the triarylmethane dianion form. A key feature of phenophthaleins that likely facilitates this interconversion process is the comparatively long C-O bond within the phthalide ring (sp3 hybridised spiro carbon atom to oxygen). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies show that the C-O bond of phenolphthalein is ~0.07 Å longer than would be expected for typical 5-membered ring lactones [5].

Scheme 1.

Interconversion of the phthalide and triarylmethane dianion forms of phenolphthalein (1).

In addition to applications as pH indicators, phenolphthaleins have been investigated as inhibitors of the enzyme thymidylate synthase (TS) [6,7,8,9]. This enzyme is an important drug target for cancer therapy since it plays a role in the biosynthesis of DNA. Lactobacillus casei thymidylate synthase has been used as a model enzyme for inhibition studies, and as part of these investigations, the X-ray crystal structure of phenolphthalein bound to the enzyme has been determined [9]. Subsequently, NMR studies and quantum mechanical calculation methods were employed to investigate the structures of phenolphthaleins and closely related analogues [6,7,8]. That report concluded there was a relationship between the conformations of the phenolphthalein derivatives that were studied and their ability to act as enzyme inhibitors. It was also demonstrated that molecules where the phenol substituents had higher degrees of rotational freedom were more likely to be active inhibitors than those that were more rotationally restricted.

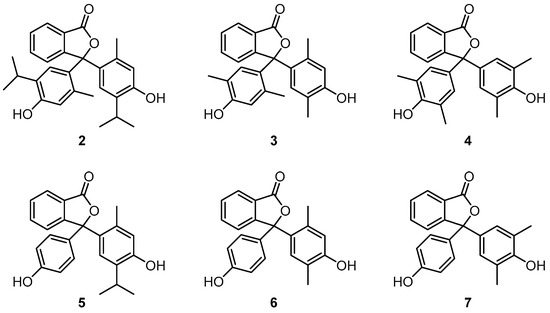

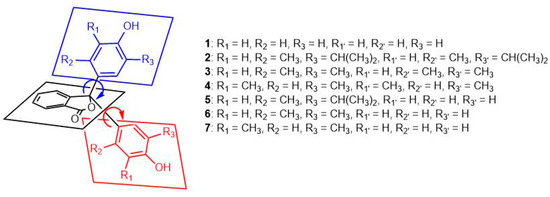

In this paper, we report the results from the study of phenolphthalein (1) and six phenolphthalein derivatives (compounds 2–7, Figure 1). In each case, the molecular structures have been determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The structures have been used to investigate the effect of the differing phenol substituents on the geometry of each compound, with a focus on the phthalide C-O bond lengths and the degree of rotation of each phenol substituent relative to the plane of the phthalide ring.

Figure 1.

Phenolphthaleins (2–7) selected for study by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Details/Instruments

Phenolphthalein (1) and thymolphthalein (2) were used as supplied (Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd., Gillingham, UK). 2-(4-Hydroxybenzoyl)-benzoic acid (8) was prepared from phenolphthalein by a literature method reported by Hubacher [10]. Melting points were recorded on a Stuart SMP3 melting point apparatus (tolerance ±1.5 °C at 300 °C) (Mettler Toledo Ltd., Leicester, UK). The melting point apparatus was calibrated using samples of phenolphthalein (mp 261–263 °C). NMR spectra were obtained for 1H at 400 MHz and for 13C at 101 MHz using a Bruker AVIII_HD 400 instrument (Bruker UK Ltd., Coventry, UK). Spectra were run at 25 °C in DMSO-d6. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to the frequency of the reference, and the coupling constants J are reported in Hz.

2.2. General Procedure 1: Synthesis of Compounds 3 and 4

Phthalic anhydride (0.3 g, 2.03 mmol), the appropriate dimethylphenol (0.4 g, 3.27 mmol), and 1 g of methanesulfonic acid were mixed in a test tube and heated to 90 °C for 5 h. The hot reaction mixture was quenched with water (20 mL), and the resulting mixture was heated in a water bath (100 °C) for 10 min. On cooling, the crude product was filtered off under suction. The product was recrystallised from a mixture of methanol and water.

- 3,3-bis(4-hydroxy-2,5-dimethylphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (3)

Compound 3 was prepared according to general procedure 1 using 2,5-dimethylphenol (270 mg, 44%). mp 291–293 °C (lit. [1] 286–289 °C), 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6); 9.40 (2H, s, OH), 7.91 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, ArH), 7.81 (1H, td, J = 7.6, 1.1 Hz, ArH), 7.64 (1H, td, J = 7.8, 1.1 Hz, ArH), 7.49 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, ArH), 6.65 (2H, s, ArH), 6.61 (2H, s, ArH), 1.96 (6H, s, CH3), 1.91 (6H, s, CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6); 169.9 (C=O), 155.6 (ArCq), 152.5 (ArCq), 135.2 (ArCq), 135.0 (ArCq), 129.9 (ArCH), 129.8 (ArCH), 129.7 (ArCq), 125.7 (ArCq), 125.6 (ArCH), 121.1 (ArCq), 119.2 (ArCH), 94.1 (Cq), 21.2 (CH3), 16.2 (CH3).

- 3,3-bis(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (4)

Compound 4 was prepared according to general procedure 1 using 2,6-dimethylphenol (295 mg, 52%). mp 253–255 °C (lit. [1] 247–249 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6); 8.44 (2H, s, OH), 7.87 (1H, td, J = 7.6, 1.0 Hz, ArH), 7.78–7.83 (2H, m, ArH), 7.62 (1H, ddd, J = 7.6, 5.7, 2.3 Hz, ArH), 6.82 (4H, s, ArH), 2.11 (12H, s, CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6); 169.7 (C=O), 153.7 (ArCq), 153.1 (ArCq), 135.1 (ArCH), 132.0 (ArCq), 129.9 (ArCH), 127.0 (ArCH), 125.7 (ArCH), 125.0 (ArCH), 124.9 (ArCq), 124.6 (ArCq), 92.0 (Cq), 17.2 (CH3).

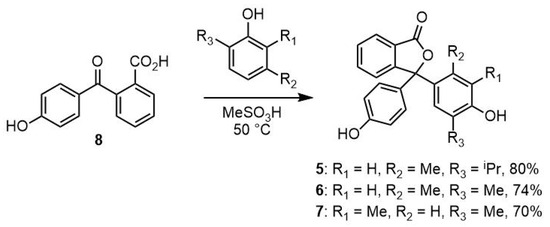

2.3. General Procedure 2: Synthesis of Compounds 5, 6, and 7

2-(4-Hydroxybenzoyl)-benzoic acid (0.4 g, 1.64 mmol), the selected dialkylphenol (1.64 mmol), and 1 g of methanesulfonic acid were mixed in a test tube and heated to 50 °C for 1 h. The reaction was quenched with water (20 mL), and the resulting mixture was heated in a water bath (100 °C) for 10 min. On cooling, the crude product was filtered off under suction. The product was recrystallised from a mixture of methanol and water.

- 3-(4-hydroxy-5-isopropyl-2-methylphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (5)

Compound 5 was prepared according to general procedure 2 using thymol (500 mg, 81%). mp 286–289 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6); 9.51 (2H, s, OH), 7.91 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, ArH), 7.82 (1H, td, J = 7.6, 1.1 Hz, ArH), 7.63 (1H, td, J = 7.8, 1.1 Hz, ArH), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, ArH), 6.97 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 6.85 (1H, s, ArH), 6.73 (2H, d, J = 8.7, Hz, ArH), 6.67 (1H, s, ArH), 3.06 (1H, sept, J = 6.8, Hz, CH), 1.06 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3), 0.92 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6); 169.9 (C=O), 157.4 (ArCq), 155.2 (ArCq), 153.5 (ArCq), 136.8 (ArCq), 134.7 (ArCH), 132.8 (ArCq), 130.6 (ArCq), 129.9 (ArCH), 128.2 (ArCq), 126.5 (ArCH), 126.0 (ArCH), 125.7 (ArCH), 124.6 (ArCq), 119.7 (ArCH), 93.0 (Cq), 26.8 (CH), 22.8 (CH3).

- 3-(4-hydroxy-2,5-dimethylphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (6)

Compound 6 was prepared according to general procedure 2 using 2,5-dimethylphenol (400 mg, 70%). mp 251–253 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6); 9.55 (1H, s, OH), 9.48 (1H, s, OH), 7.90 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, ArH), 7.80 (1H, td, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz, ArH), 7.62 (1H, td, J = 7.5, 1.0 Hz, ArH), 7.57 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, ArH), 6.98 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, ArH), 6.77 (1H, s, ArH), 6.72 (2H, d, J = 8.6, Hz, ArH), 6.68 (1H, s, ArH), 1.98 (3H, s, CH3), 1.92 (3H, s, CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6); 169.9 (C=O), 157.4 (ArCq), 156.1 (ArCq), 153.4 (ArCq), 137.1 (ArCq), 134.9 (ArCH), 132.8 (ArCq), 130.9 (ArCH), 129.8 (ArCH), 128.2 (ArCq), 126.6 (ArCH), 126.0 (ArCH), 125.8 (ArCH), 124.6 (ArCq), 120.3 (ArCq), 119.4 (ArCH), 116.0 (ArCH), 92.8 (Cq), 21.2 (CH3), 16.1 (CH3).

- 3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (7)

Compound 7 was prepared according to general procedure 2 using 2,6-dimethylphenol (420 mg, 74%). mp 217–219 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6); 9.65 (1H, s, OH), 8.46 (1H, s, OH), 7.89 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, ArH), 7.72–7.86 (2H, m, ArH), 7.63 (1H, td, J = 7.6, 1.0 Hz, ArH), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, ArH), 6.84 (2H, s, ArH), 6.75 (2H, d, J = 8.6, Hz, ArH), 2.12 (6H, s, 2 × CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6); 169.6 (C=O), 158.0 (ArCq), 153.8 (ArCq), 153.1 (ArCq), 135.2 (ArCH), 131.8 (ArCq), 129.9 (ArCH), 128.7 (ArCH), 127.0 (ArCH), 125.8 (ArCH), 125.0 (ArCH), 124.9 (ArCq), 124.6 (ArCq), 115.6 (ArCH), 91.9 (Cq), 17.2 (CH3).

2.4. X-Ray Crystallography

X-ray diffraction data for compounds 1, 2, and 4–7 were collected using a Rigaku FR-X Ultrahigh Brilliance Microfocus RA generator/confocal optics with XtaLAB P200 diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) [Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å)]. X-ray diffraction data for compounds 3 and 8 were collected using a Rigaku SCXmini CCD diffractometer with a SHINE monochromator (Rigaku USA, The Woodlands, TX, USA) [Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å)]. Intensity data for all analysed compounds were collected (using a calculated strategy) and processed (including correction for Lorentz, polarisation, and absorption) using CrysAlisPro [11]. Data for 6 was processed as a two-component twin with the second component rotated −179.9762° around 0.80 0.00 0.60 (reciprocal), 0.71 0.00 0.71 (direct). Structures were solved by dual-space methods (SHELXT [12]) and refined by full-matrix least-squares against F2 (SHELXL-2019/3 [13]). All three hydrates in the structure of 6 showed positional disorder and were modelled in two parts, with the occupancy of each pair refined separately. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms were refined using a riding model except for the hydrogen atoms on hydroxyl and water moieties which were located from the difference Fourier map and refined isotropically subject to distance restraints, except for disordered water solvates in 6, for which hydrogen atoms were placed in estimated positions from the Fourier map, rotated to maximise hydrogen bonding, and refined using a riding model with O-H distances constrained. All calculations were performed using the Olex2 [14] interface. Selected crystallographic data are presented in Table S1. CCDC 2492436-2492443 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures (accessed on 14 October 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Phenolphthalein Derivatives

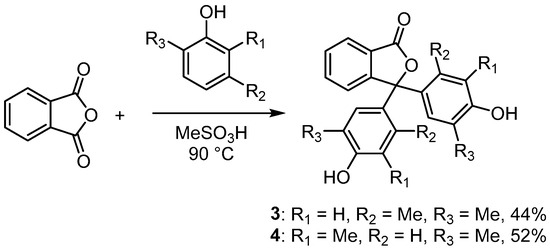

Thymolphthalein (2) was selected as one of the compounds for study. In this case, a commercial sample of material manufactured for use as a pH indicator was recrystallised slowly from a mixture of methanol and water. Surprisingly, despite 2 having been in routine use for many years [15,16], an X-ray structure has not been previously reported. Two other dialkylated phenolphthaleins (3 and 4) were also selected. These compounds are not commercially available; however, they are readily prepared by reacting phthalic anhydride with the appropriate phenol [1,2]. Phenolphthalein and its derivatives are often prepared by heating phenol with phthalic anhydride under acidic conditions (Scheme 2). We have found that the procedure reported by Sabnis is an efficient method to synthesise phenolphthalein derivatives [1]. Accordingly, phthalic anhydride was heated with 2,5-dimethylphenol and 2,6-dimethylphenol in methanesulfonic acid to afford the products (3 and 4) in 44% and 52% yield, respectively, after recrystallisation.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of phthalic anhydride with dimethylphenols in methanesulfonic acid to form phenolphthalein derivatives 3 and 4.

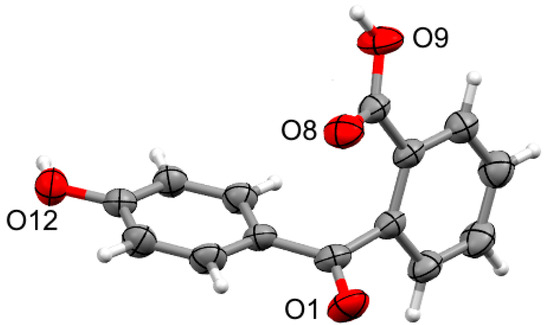

This study also investigated the unsymmetrical analogues (5, 6, and 7) of phenolphthaleins 2, 3, and 4. Compounds 5, 6, and 7 are rarely reported in the literature [17]; therefore, an efficient method to prepare these compounds was required. It has been shown that 2-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)benzoic acid (8) is a convenient precursor for related compounds, so 8 was selected as the starting material [18,19]. The method reported by Hubacher in 1946 allowed multigram quantities of compound 8 to be efficiently prepared from phenolphthalein [10]. The product was readily purified by recrystallisation from water, and, pleasingly, samples suitable for analysis by single-crystal X-ray diffraction were isolated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

X-ray structure of 2-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)benzoic acid (8) with ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability and selected atom names shown.

Further investigation revealed that compound 8 could be readily converted to the desired unsymmetrical phenolphthalein derivatives by adapting the protocol developed by Sabnis. We have found that reacting 2-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)benzoic acid (8) with thymol, 2,5-dimethylphenol, or 2,6-dimethylphenol in methanesulfonic acid at 50 °C for 60 min afforded compounds 5, 6, and 7, respectively, in good yields (Scheme 3). Each compound was purified by recrystallisation from methanol–water solution, and material suitable for analysis by single-crystal X-ray diffraction was readily obtained by this method.

Scheme 3.

Reaction of 2-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)benzoic acid (8) with dialkylphenols in methanesulfonic acid to form phenolphthalein derivatives 5, 6, and 7.

3.2. X-Ray Structure Determination

Crystals of 1 suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained from a methanol–water solution and were seen to be isomorphous to the known room temperature structures [5,20], showing two independent molecules in the asymmetric unit (Figure 3). The sp3 spiro carbons show the expected distortions from tetrahedral geometry arising from the constraint of the phthalide ring (endocyclic O-C-C 102.08(13) and 102.39(12)°), the angle between the two phenol rings being wider than the idealised tetrahedral angle (C-C-C 114.79(14) and 114.37(13)°). The C-O bond from the spiro carbon shows slight elongation (C-O 1.488(2) and 1.4813(19) Å) from the expected γ-lactone C-O distance 1.45–1.47 Å [21], as was seen in the reported room temperature structures (1.478(4), 1.497(5), and 1.485(3), 1.490(4)Å). In both independent molecules, both phenol rings are twisted away from the phthalide 49.56(8)–61.55(8)° and are twisted with respect to each other 76.16(7) and 79.98(7)°, respectively. The hydroxyl groups of the phenols form O-H···O hydrogen bonds to a mix of phenol hydroxyl and phthalide carbonyl oxygens of adjacent molecules (Table S2). The two independent molecules form separate, interpenetrating, hydrogen-bonded arrays of molecules (Figure S11) which propagate as undulating sheets in the (1 0 0) plane.

Figure 3.

X-ray structure of 1 showing one independent molecule with ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability and selected atom names shown.

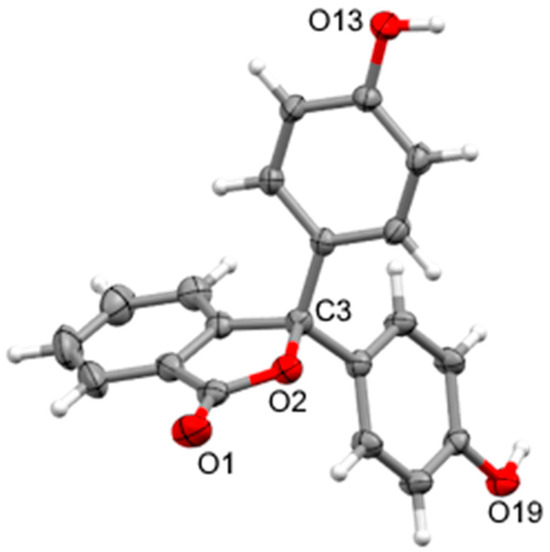

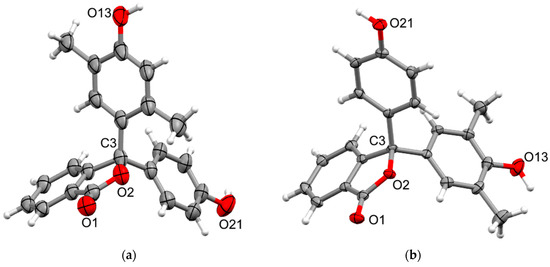

Crystals of thymolphthalein, 2, suitable for X-ray analysis, were obtained from a methanol solution, while its asymmetric analogue, phenolthymolphthalein, 5, was obtained from a methanol–water solution. The compounds crystallise in the monoclinic space groups P21/c and P21/n, respectively, each having a single molecule in the asymmetric unit (Figure 4). Both structures show the expected distortion from tetrahedral geometry at the sp3 spiro carbon from the constraint of the phthalide ring (endocyclic O-C-C 102.09(9) and 102.12(8)°, respectively) and similar angles between the thymol/phenol rings as 1 (C-C-C 112.58(9) and 114.12(9)°). Also, similar to 1, the adjacent C-O bonds in both structures are slightly longer than typical (C-O 1.4828(14) and 1.4822(13)Å). In both structures, the thymol/phenol rings show significantly different twists with respect to the phthalide ring. The structure of 2 shows a very large difference with the thymol rings twisted 27.32(5) and 70.94(5)° from the phthalide and nearly perpendicular (88.71(4)°) with respect to each other. The twists are more moderate in 5, with the phenol ring twisted 61.38(5)°, similar to 1, and the thymol twisted 30.81(5)° with respect to the phthalide. The two rings are again nearly perpendicular (85.73(4)°) to each other. Both structures pack in a similar manner by first forming intermolecular dimers through reciprocal O-H···O hydrogen bonding from one thymol hydroxyl to the carbonyl of the phthalide (Table S2) which then link together into chains along the [1 0 0] or [0 0 1] axes, respectively, (Figures S12 and S13) through additional hydrogen bonding between adjacent thymol/phenol hydroxyls (Table S2).

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structures of (a) 2 and (b) 5. Ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability, and selected atom names are shown.

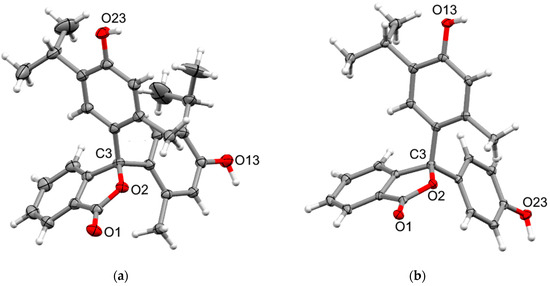

Crystals of the 2,5- and 2,6-xylenolphthaleins, 3 and 4, suitable for X-ray analysis, were obtained from their respective methanol–water solutions. The compounds crystallise in the monoclinic space groups P21/c and P21/n, respectively, each having a single molecule in the asymmetric unit (Figure 5). As expected, both structures show distortion from tetrahedral geometry at the sp3 spiro carbon (endocyclic O-C-C 101.46(11) and 102.44(9)°) and similar larger angles between the xylenol rings (C-C-C 116.53(12) and 113.99(9)°). Both structures also see elongation of the adjacent C-O bond (C-O 1.5030(18) and 1.4879(13) Å), with the bond in 3 significantly longer than expected. The xylenol rings in 3 show similar twists to those observed in 2, with their twist with respect to the phthalide of 82.15(7) and 35.25(2)°, while being nearly perpendicular to each other (83.30(6)°). In contrast, 4 shows moderate twists for both xylenol rings with respect to the phthalide (49.60(5) and 58.30(3)°, respectively), but still nearly perpendicular to each other (80.36(4)°). Adjacent molecules of 3 form intermolecular dimers through reciprocal O-H···O hydrogen bonds (Table S2) from one xylenol to the phthalide carbonyl in a manner, as was seen in 2 and 5. These intermolecular dimers then pack into sheets in the (1 0 0) plane through additional H···O hydrogen bonds (Table S2) from the other xylenol to the phthalide (Figure S14). The packing of these sheets is supported by weaker non-classical hydrogen bonds (H···O 2.4675(13), C···O 3.354(2) Å). In contrast, only one xylenol in 4 forms a hydrogen bond, which is to the phthalide carbonyl of an adjacent molecule (Table S2) with a weaker non-classical C-H···O hydrogen bond from the fused benzo to the hydroxyl oxygen (H···O 2.4446(9), C···O 3.2901(15) Å) which form rings. These hydrogen bonding interactions link molecules into chains along the [1 0 −1] axis which then further pack together through additional non-classical hydrogen bonds from the aromatic xylenol hydrogens to the carbonyl and hydroxyl oxygens (H···O 2.3949(8) and 2.5672(8) Å, C···O 3.3346(15) and 3.4584(15) Å, respectively), forming type rings, to form sheets in the (1 0 1) plane (Figure S15). The hydroxyl of the other xylenol in 4 is orientated towards the fused benzo ring of the phthalide in an O-H···π type hydrogen bond (H···centroid 2.609(17) Å, O···centroid 3.1728(10) Å, Figure S16) with this interaction linking the hydrogen-bonded sheets together.

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structures of (a) 3 (minor component of disorder omitted) and (b) 4. Ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability, and selected atom names are shown.

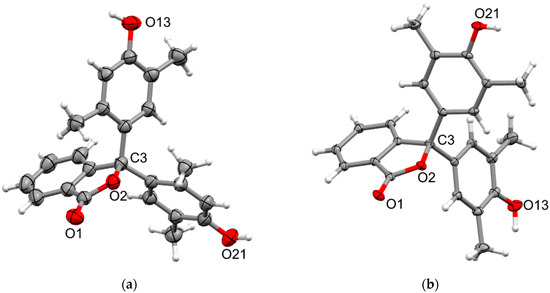

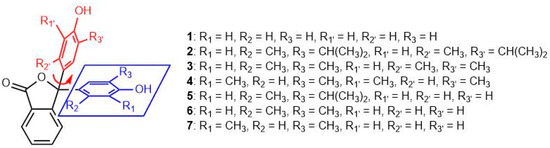

Crystals of the asymmetric 2,5- and 2,6-xylenolphenolphthaleins, 6 and 7, suitable for X-ray analysis, were obtained from their respective methanol–water solutions. The compounds crystallise in the monoclinic space groups I2/a and P21, respectively, with both structures containing two independent molecules (Figure 6) and either water or a mixture of water and methanol solvates (3 H2O in 6, 2 H2O and 2 EtOH in 7). Both show the expected distortion from tetrahedral geometry at the sp3 spiro carbon with the endocyclic angle constrained by the phthalide (endocyclic O-C-C 102.44(19) and 101.88(19)°, and 102.3(2) and 101.9(3)° for 6 and 7, respectively) and similar increase in the angle between the xylenol/phenol rings (C-C-C 112.8(2) and 113.76(19)°, and 113.2(2) and 113.7(3)° for 6 and 7, respectively) as is observed in the other structures. The substituent rings in 6 show varied twists with respect to the phthalide in a similar manner to 5, with the phenol ring in both independent units twisted more (57.06(9) and 52.65(9)°) than the xylenol rings (32.93(10) and 37.07(11)°). In 7, the substituent rings all show similar moderate twists (42.92(14)–48.41(15)°). Despite the variation in twist with respect to the phthalide, the rings in both independent molecules in both structures are close to perpendicular (81.1(1)–84.16(11)°) with respect to each other. In the structure of 6 only one hydroxyl group (O44) forms a direct hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen (O1) of an adjacent molecule (H···O 1.80(2) Å, O···O 2.754(2) Å), with the remaining intermolecular hydrogen bonds being facilitated by water molecules bridging adjacent hydroxyls, and hydroxyl to phthalide oxygens of adjacent molecules (Table S2). The structure of 7 shows similar intermolecular interactions as 7 with only one hydroxyl group (O44) forming a direct hydrogen bond to the hydroxyl oxygen (O21) of an adjacent molecule (Table S2), with the other hydrogen bonds bridging hydroxyl and phthalide groups via the water and methanol solvates (Table S2). Both structures also show various non-classical Car-H···O hydrogen bonds (H···O 2.506(4)–2.9938(18) and 2.496(2)–2.679(2) Å, C···O 3.205(5)–3.842(3) and 3.384(4)–3.614(4) Å, for 6 and 7, respectively) supporting the packing of both structures in a hydrogen-bonded lattice. Additionally, 6 shows a weak non-standard π···π interaction from the carbonyl of a phthalide to the fused benzo ring (C27>32) of an adjacent molecule (centroidC=O···centroid 3.460(2) Å).

Figure 6.

X-ray crystal structures of (a) 6 and (b) 7. Only one independent molecule is shown for each, and solvents are omitted for clarity. Ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability, and selected atom names are shown.

Crystals of 8 suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained from an aqueous solution. The compound crystallises in the monoclinic space group P21/c with a single molecule in the asymmetric unit (Figure 2). The two aromatic rings are twisted significantly away from co-planar (angle between planes 104.51(5)°), and with the carboxylic acid oriented to point in the direction of the phenol group. The hydroxyl groups of the phenol and the carboxylic acid form O-H···O hydrogen bonds to the carboxylic acid carbonyl and the ketone carbonyl (Table S2) of adjacent molecules, respectively. These hydrogen bonds assemble molecules of 8 into sheets in the (1 0 0) plane (Figure S18) which are supported by weaker non-classical C-H···O hydrogen bonds (H···O 2.5707(11)–2.7583(11) Å, C···O 3.4946(18)–3.5766(17) Å) as well as weak π···π stacking between adjacent phenol rings (centroid···centroid 3.6710(13) Å).

4. Discussion

A study from 2019 noted that the phthalide ring C-O bond length (O2-C3, Table 1) of phenolphthalein (1) is typically longer than those within simpler 5-membered ring lactones [4]. The report highlighted that the longer C-O bond likely facilitated the phthalide ring-opening reactions of both phenolphthalein and an N,N-dimethylamino derivative when hydrostatic pressure was applied to solid samples. This study also focused on the effect of changing the phenol substituents attached to the phthalide ring, concluding that electron-donating groups allowed lower pressures to be applied to cleave the C-O bond. Our study has allowed the phthalide C-O bond lengths in compounds 1–7 to be measured, and the results are presented in Table 1 (data for compound 1 at room temperature have been reported previously) [5,20]. The C-O bond lengths of compounds 2–7 are commensurate with those of phenolphthalein under the same conditions. We have found that varying the phenol ring substituents by alkylation at different positions does not affect this C-O bond length in a systematic manner.

Table 1.

Phthalide C-O bond distances (O2-C3) for compounds 1–7.

We have also examined the effect of phenol substituents on the geometry of compounds 1–7. This type of structural information may be useful in future studies on the applications of phenolphthalein derivatives, as it is complementary to existing studies using NMR data and quantum mechanical calculations to investigate the conformations of a series of phenolphthaleins [6]. Several of the compounds studied show a significant degree of twist between phenol and phthalide rings (Figure 7) compared to the values obtained from phenolphthalein (1, Table 2). The degree of twist is most pronounced in compounds 2 and 3, both of which possess 2,5-disubstituted phenol groups. The substituents in the 5-position (R2 and R2′) are methyl groups in close proximity to the phthalide ring and likely force an orientation at a position that minimises steric clash between the phenol substituents. In contrast, compound 4 has 2,6-disubstituted phenol groups, and the degree of twisting between the phenol rings and phthalide ring does not deviate significantly when compared with 1. The degree of twisting is reduced in the unsymmetrical analogues, 5 and 6; both of these compounds feature a single 2,5-disubstituted phenol ring. The other phenol substituent is not alkylated, which likely reduces the degree of steric congestion between the phenol substituents in comparison to compounds 2 and 3. Compound 7 also features an unsubstituted phenol ring; the other ring is 2,6-disubstituted (methyl groups). The twist angles in this case are closer to those in phenolphthalein than the other unsymmetrical compounds 5 and 6.

Figure 7.

Twist angles of the phenol substituents relative to the plane of the phthalide ring.

Table 2.

Selected conformational data from the structures of compounds 1–7.

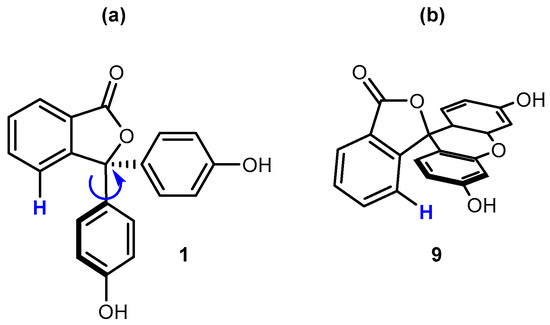

One of the key findings from previous work was that the phthalide hydrogen atom that is positioned closest to the phenol rings (Figure 8) could display varied chemical shifts that were related to the substitution pattern [6]. This chemical shift variation was attributed to the degree of ring current shielding provided by the adjacent aromatic rings. In cases where the plane of the phthalide ring and the plane of the phenol substituents were perpendicular, the closest phthalide proton was significantly shielded because of aromatic ring current shielding cones being oriented directly toward that proton. For example, the chemical shift of the phthalide proton adjacent to the phenol rings of phenolphthalein (1) was observed at 7.84 ppm for samples in deuterated DMSO at 303 K. In contrast, the corresponding phthalide proton in fluorescein (9) showed a chemical shift of 7.37 ppm under the same conditions. This difference was explained by compound 9 having a constrained aromatic ring system that is perpendicular to the plane of the phthalide ring.

Figure 8.

(a) Molecular structure of 1, showing rotation of the phenol ring relative to the closest phthalide hydrogen atom (highlighted in blue). (b) Molecular structure of compound 9, showing the constrained perpendicular relationship of the polyaromatic ring relative to the closest phthalide hydrogen atom (highlighted in blue).

Despite the differing effects on molecular geometry between solid-state structural data with solution-state NMR data, there are some correlations that align with the conclusions of earlier work. The 2,5-dialkylphenolphthaleins 2 and 3 show phthalide (H-5) chemical shifts that are lower than the corresponding signal for phenolphthalein in deuterated DMSO at 298 K (Table 3 and Figure S19). The structures of these compounds show the largest twist angle between a phenol ring plane and the phthalide ring plane (Table 2), and the NMR data suggest this behavior is retained in solution. In contrast, compounds 4–7 show maximum phenol to phthalide ring plane angles that are similar to or less than those seen in phenolphthalein, and H-5 chemical shifts lower than the corresponding signal for 1. The Δ δH values for 4–7 lie between the values for 1 and those for 2 and 3, suggesting that the substituents have more effect on phenol ring plane orientation in solution than in the solid state. These results indicate that the geometries seen in the solid-state structures of these compounds do not always fully correlate with their geometries in the solution state.

Table 3.

H-5 chemical shift values for compounds 2–7 and H-5 chemical shift differences relative to phenolphthalein (1) a.

The angles between the planes of the phenol substituents (Figure 9) are included in Table 2. Compounds 2–7 all display an increase in the angles of the phenol rings, relative to 1; compounds 2 and 5 showing the largest deviation from the values measured for 1. These observations are not so surprising since these compounds possess phenol substituents that are alkylated at the 2 and 5 positions (labelled R3 and R2, respectively), and one of these substituents is the bulky isopropyl group. Compound 3 is also 2,5-disubstituted; in this case, both alkyl substituents are methyl groups. It shows a larger angle between its phenol rings than observed in 1, but a smaller angle than seen for compounds 2 and 5. Compound 4 is also dimethylated, but at the 2- and 6-positions, so the methyl groups are not as close to those on the other substituent as in 3. This geometry may account for the phenol-phenol twist angle being closer to phenolphthalein (1). Compounds 6 and 7 are both unsymmetrical since they have a phenol and a dimethylated phenol substituent. The expectation might be that both compounds would show an angle between phenol rings closer to 1 due to reduced steric repulsions between the phenolic substituents. Both compounds show angles between phenol rings greater than that for 1. In compound 6, the angles are only slightly larger than those of 1; however, compound 7 shows unexpectedly large angles between phenols in both independent molecules.

Figure 9.

Angles between the planes of the phenol substituents.

5. Conclusions

X-ray diffraction data for a set of phenolphthalein derivatives (2–7) have been collected and compared to newly acquired data for phenolphthalein (1) [5,20]. The phthalide C-O (O2-C3) bond lengths from compounds 2–7 were found to be longer than expected for 5-membered ring lactones. This observation aligns with previous studies on phenolphthalein (1) [4,5,20]. Furthermore, we have found that varying the position of alkyl substituents on the phenol ring did not have a systematic effect on the C-O bond length. The effect of varying the phenol substituents on the degree of twist between phenol and phthalide rings, and the angles between the planes of the phenol substituents, has been examined. The twist angle between the phenol and phthalide rings was found to vary; the symmetrical compounds 2 and 3 (featuring a 2,5-dialkyl substitution pattern) deviated most in comparison with phenolphthalein. Compounds 2–7 all show an increase in the angle between the phenol ring substituents, relative to phenolphthalein (1). The substituent effects on the angle between the phenol and phthalide rings for samples in the solution state were investigated using 1H NMR spectroscopy. The geometries observed in the solid-state structures of compounds 2 and 3 were found to correlate to an extent with their geometries in the solution state. However, this degree of correlation did not hold for the rest of the compounds studied.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst15100901/s1. Figure S1: 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of 3; Figure S2: 100 MHz 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum of 3; Figure S3: 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of 4; Figure S4: 100 MHz 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum of 4; Figure S5: 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of 5; Figure S6: 100 MHz 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum of 5; Figure S7: 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of 6; Figure S8: 100 MHz 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum of 6; Figure S9: 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of 7; Figure S10: 100 MHz 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum of 7; Table S1: Selected crystallographic data for compounds 1–8; Table S2: Hydrogen bonding metrics for compounds 1–8; Figure S11: Interpenetrated hydrogen bonded sheets of the two independent molecules of 1 across (1 0 0); Figure S12: Hydrogen bonded chains of 2 along [1 0 0]; Figure S13: Hydrogen bonded chains of 5 along [0 0 1]; Figure S14: Hydrogen bonded sheets of 3 across (1 0 0); Figure S15: Hydrogen bonded sheets of 4 across (1 0 1); Figure S16: O-H···π interaction between adjacent molecules of 4; Figure S17: Hydrogen bonding interactions in 6 (left) and 7 (right); Figure S18: Hydrogen bonded sheets of 8 across (1 0 0); Figure S19: 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum (expanded) of a commercially supplied sample of 1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and methodology, I.A.S. and R.J.P.; investigation and formal analysis, D.B.C., A.P.M., N.V., I.A.S., J.H.S.-S., B.A.C. and I.L.J.P.; data curation, D.B.C. and A.P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.M., N.V., I.L.J.P. and I.A.S.; writing—review and editing, B.A.C., D.B.C., A.P.M., R.J.P., I.L.J.P. and I.A.S.; visualisation, A.P.M. and I.A.S.; supervision, D.B.C. and I.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository. CCDC 2492436-2492443 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the University of St. Andrews School of Chemistry for the use of laboratory facilities and the provision of materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCDC | Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre |

| DMSO | Dimethylsulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

References

- Sabnis, R.W. A facile synthesis of phthalein dyes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 6261–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, R.W. Developments in the chemistry and applications of phthalein dyes. Part 1: Industrial applications. Color. Technol. 2018, 134, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittke, G. Reactions of phenolphthalein at various pH values. J. Chem. Educ. 1983, 60, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Guo, H.; Meng, X.; Wang, K.; Zou, B.; Ma, Y. Visible responses under high pressure in crystals: Phenolphthalein and its analogues with adjustable ring-opening threshold pressures. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugira, H.; Kato, T.; Senda, H.; Kunimoto, K.K.; Kuwae, A.; Hanai, K. Crystal Structure of Phenolphthalein. Anal. Sci. 1999, 15, 611–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelli, S.; Rastelli, G.; Barlocco, D.; Rinaldi, M.; Tondi, D.; Pecorari, P.; Costi, M.P. Conformational Analysis of Phthalein Derivatives Acting as Thymidylate Synthase Inhibitors by Means of 1H NMR and Quantum Chemical Calculations. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1996, 4, 1783–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costi, P.M.; Rinaldi, M.; Tondi, D.; Pecorari, P.; Barlocco, D.; Ghelli, S.; Stroud, R.M.; Santi, D.V.; Stout, T.J.; Musiu, C.; et al. Phthalein Derivatives as a New Tool for Selectivity in Thymidylate Synthase Inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghelli, S.; Rinaldi, M.; Barlocco, D.; Gelain, A.; Pecorari, P.; Tondi, D.; Rastelli, G.; Costi, M.P. ortho-Halogen Naphthaleins as Specific Inhibitors of Lactobacillus casei Thymidylate Synthase. Conformational Properties and Biological Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoichet, B.K.; Stroud, R.M.; Santi, D.V.; Kuntz, I.D.; Perry, K.M. Structure-Based Discovery of Inhibitors of Thymidylate Synthase. Science 1993, 259, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubacher, M.H. The Preparation of 2-(Hydroxybenzoyl)-benzoic Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1946, 68, 718–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro, v1.171.42.94a, 43.109a, 43.129a, and 43.144a; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction; Rigaku Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 2023, 2024.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövgren, S. Eine Methode zur maßanalytischen Bestimmung von Ammoniumsalzen. Fresenius Z. Anal. Chem. 1924, 64, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollenberger, C.J. Thymolphthalein as Indicator for Titrimetric Estimation of Carbon Dioxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1928, 20, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romiński, J.K. 3,3-Diarylphthalides. Part I. Friedländer reaction of 3′-alkylphenolphthaleins. Pol. J. Chem. 1997, 71, 908–914. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, H. The constitution of phenolphthalein. Part 1. Preparation of some compounds of the phthalein type. J. Chem. Soc. 1928, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhoroshev, S.V.; Nekhoroshev, V.P.; Poleshchuk, O.K.; Yarkova, A.G.; Nekhorosheva, A.V.; Gasparyan, A.K. New chemical markers based on phthaleins. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2015, 88, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L.J.; Gerkin, R.E. Phenolphthalein and 3′,3″-Dinitrophenolphthalein. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1998, 54, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, F.H.; Watson, D.G.; Brammer, L.; Orpen, A.G.; Taylor, R. International Tables for Crystallography; Fuess, H., Hahn, T., Wondratschek, H., Müller, U., Shmueli, U., Prince, E., Authier, A., Kopský, V., Litvin, D.B., Rossmann, M.G., et al., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume C, pp. 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).