Abstract

By substituting the A site in - and varying the lattice parameters a, b, c, and the unit-cell angles, along with using crystal graph convolutional neural networks to calculate their cohesive energy, the candidate compounds, and , were selected from the structure with the lowest cohesive energy. The two candidate structures were then optimized using first-principles calculations, and their phonon, electronic, and elastic properties were computed. As a result, two dynamically stable structures were found: with a space group of and with a space group of . Their phonon spectra exhibited no imaginary frequencies; thus, their elastic constants satisfied the mechanical stability criteria. Structurally, is similar to 6H- and 15R-. Its elastic constants indicated that it is harder than those materials. exhibits metallic properties and the indirect wide-bandgap of was calculated by the generalized gradient approximation, the local density approximation, and the screened hybrid functional of Heyd, Scuseria, and Ernzerhof (HSE06) is found to be 3.093, 3.048, and 4.589 eV, respectively. According to this wide bandgap, we can conclude that has the potential to be used in high-temperature and high-power environments, making it usable in a broad range of applications.

1. Introduction

Carbon and nitrogen are the primary elements of planetary atmospheres, and anion cyanide or isocyanide has numerous potential applications in industrial materials and catalysts [1,2,3]. Previous work has reported the stability and electronic properties of six structures (, , , , , and ) of alkaline-earth metal cyanides (A = , , , , and ) using modified crystals of known structures and first-principles calculations [4]. The calculations demonstrate that some structures are potentially stable, including the structure, which is metallic, and other structures with bandgaps ranging from 2.83 to 6.33 eV.

These compound variants can be applied to systems other than alkaline-earth elements. The bonding nature between C and N in such systems may alter the structure, properties, and stability even when the formula is the same. The technique of structural simulation is the most popular and useful way to investigate valuable components made of well-known elements. Some reports of amorphous materials with various C/N ratios have been developed (e.g., Matsunaga et al. [5]). However, there have been relatively few studies on compounds in regard to stoichiometry, such as , where A is not a common valent element (e.g., alkaline-earth metal and zinc). Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate the potential structures of these compounds using computational simulations.

Recently, crystal graph convolutional neural networks (CGCNN) have been used to predict material properties, receiving significant attention in materials science [6,7,8,9]. CGCNN is exceptional for predicting properties such as formation energy, bandgap, Fermi energy, and elastic properties [6]. Crystal frameworks are represented by graphs while graph neural networks are used in forecast material performance.

In this study, the chosen structure is based on the earlier report of the structure of alkaline-earth metal cyanide [4]. Thousands of unit cells are generated by combining various side lengths and unit-cell angles, and the A atoms in are replaced with other elements. We then use CGCNN to calculate their cohesive energy to find a structure with the lowest energy. This structure is considered to be the most advantageous configuration. Other than alkaline-earth metals, aluminum and silicon were chosen as A in the formula because they have the lowest cohesive energy [10]. Additionally, their carbon and nitrogen compounds have numerous essential properties.

In the Al-C-N system, has been extensively used as a catalyst (e.g., in the textile industry) and for porous materials [1]. () is investigated for applications in materials and catalytic reactions [11]. Additionally, molecules such as , , and () may exist in the carbon star IRC+10216 [12,13]; therefore, their related structures, electronic properties, and optical properties have been studied.

Materials such as and (where x and y are any nonzero numbers) have been widely studied for their high hardness [14,15], low brittleness, low thermal expansion, high chemical, and thermal stability in the Si-C-N system. As a result, such materials are used as thin film materials, photoelectric materials, electromagnetic-wave absorption materials, etc.

2. Materials and Methods

In this work, we would like to predict the cohesive energy of . Thus, we used a CGCNN trained by inorganic crystal material data from the Materials Project [16]. The chosen structures are based on an earlier report of the structure of alkaline-earth metal cyanide [4]. We generate 1050 unit cells with varying side lengths and unit-cell angles, then substitute the A atoms in with other elements. The replaced elements include a total of 35 elements from the second to sixth periods of the first to seventh main groups. We then use CGCNN to determine the cohesive energy of a total of 36,750 unit cells [10]. Finally, aluminum and silicon (i.e., and ) were chosen for further structural optimization by using density functional theory (DFT) calculations, because they are the elements with the lowest cohesive energy besides alkaline-earth metals. In the following sections, we examine the properties (e.g., phonon, electronic, elastic) of and using DFT.

First-principles calculations based on DFT [17,18] were implemented in the Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package (CASTEP) [19,20]. For the exchange-correlation function, a generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the form of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) [21] and the local density approximation (LDA) [22,23] were considered using the on-the-fly-generated ultrasoft pseudopotential method [24]. The plane-wave kinetic-energy cutoff was set to 570 eV and, to achieve structural optimization, the k-points separation was set to 0.07 Å for all calculations in the Brillouin zone, with the Monkhorst–Pack method applied for the point distribution [25]. Since the GGA and LDA underestimate the energy bandgap [21], we used the screened hybrid functional of Heyd, Scuseria, and Ernzerhof (HSE06) [26] as a reference to calculate and along with an on-the-fly-generated norm-conserving pseudopotential [27]. The plane-wave kinetic-energy cutoff was set to 990.0 eV for HSE06. The minimization algorithm we used was the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) method [28] with convergence tolerances set to eV/atom for energy, 0.01 eV/Å for maximum force, 0.02 GPa for maximum stress, and Å for maximum displacement. The phonon spectra were calculated by using the finite-displacement method.

All the results of LDA and HSE06, including lattice parameters and band structure, are shown in the Supplementary Materials. Based on the prior reports [4], the GGA functional is more appropriate for this system. Therefore, the GGA functional is used in the subsequent calculations.

We also preformed a Mulliken population analysis for and and the elastic properties of , , 6H-, and 15R-. The graphical displays in this work are generated with BIOVIA Materials Studio.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structures of and

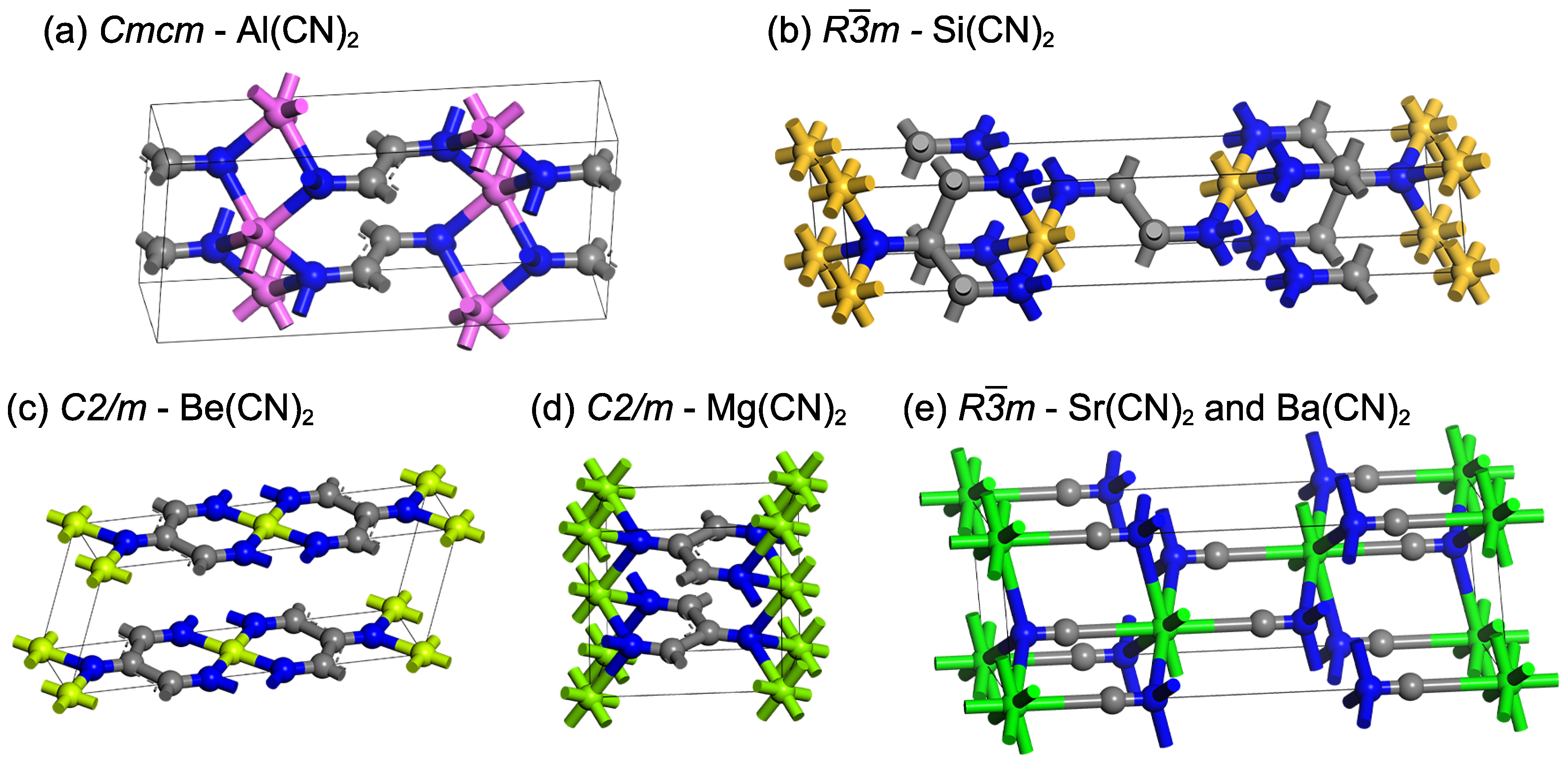

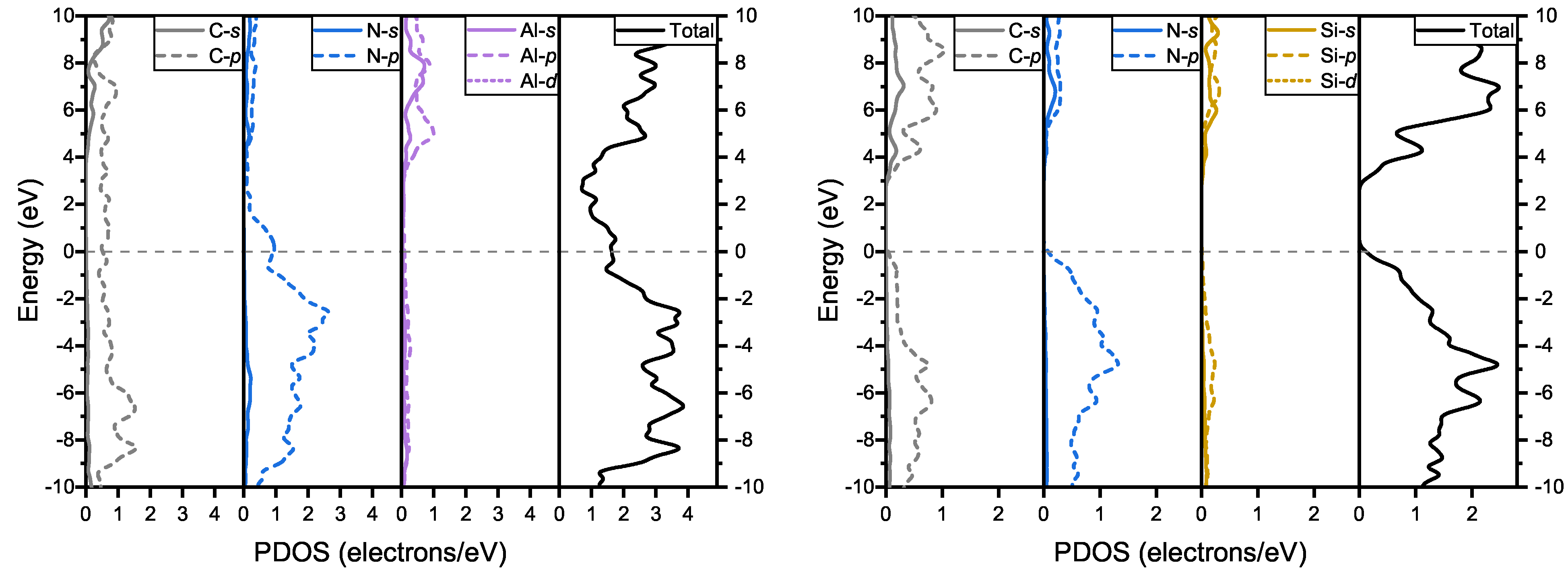

After searching with CGCNN for the structure with the lowest energy from among a large number of structures, we made use of DFT for the full relaxation geometry optimization. The structural symmetries of and are and , respectively. The unit-cell structure diagrams are shown in Figure 1 and the lattice parameters are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The unit-cell structure diagrams of (a) conventional cell structure of -, (b) hexagonal representation of -, (c,d) conventional cell structure of - and , respectively, and (e) hexagonal representation of - and . Gray: carbon; Blue: nitrogen; Purple: aluminum; Yellow: silicon; Green: alkaline-earth metal.

Table 1.

Lattice parameters of (A = , , , , , and ). is the cohesive energy.

The structure of is shown in Figure 1a; the coordination numbers of aluminum, nitrogen, and carbon are 6, 4, and 3, respectively. The bond angles ∠CCC and ∠CCN are both near to 120° (Table 1), indicating that the carbon in is hybridized and conjugated. This carbon chain structure is similar to the previously structure of and in (Figure 1c,d) [4].

In addition to the similar bond angles ∠CCC and ∠CCN in Table 1, the bond length of is comparable to that of and (1.520 Å vs. 1.501 Å and 1.598 Å, respectively). It should be noted that these three compounds are conductive and dynamically stable. The difference between them is that the bond length in is longer than that of and (1.343 Å vs. 1.279 Å and 1.270 Å, respectively). It is possible that aluminum has one extra valence electron than beryllium and magnesium, and the nitrogen connected to the metal transforms from C=N bond (e.g., vinylidendiimine , = 1.27 Å [29]) to C bond.

In terms of symmetry and the unit-cell diagram, the structure of is very close to the reported structure of and , as shown in Figure 1b,e. The coordination numbers of silicon, nitrogen, and carbon are 6, 4, and 4, respectively. In contrast, the coordination numbers of strontium/barium, nitrogen, and carbon are 8, 4, and 2, respectively. Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials displays the rhombohedral representation of these structures. In , the group is surrounded by four silicon atoms, and each group is close to forming a single bond (1.645 Å in Table 1). Meanwhile, it is considered that there is no chemical bond between the carbon atoms in and because the shortest distance between two carbons atoms is 2.903 and 3.069 Å, respectively.

The length of the unit-cell edge of is 5.672 Å, which is close to that of and (5.438 and 5.749 Å, respectively). However, the unit-cell angle of is and the cell volume is , which is significantly smaller than those of (, ) and (, ). These differences might be attributed to the fact that silicon has a much smaller atomic radius (1.11 Å) than strontium (2.19 Å) and barium (2.53 Å) [30], resulting in not enough space between silicon atoms to separate the groups. In addition, the shortest distance between carbon and silicon in is 2.912 Å (Table 1), which is much greater than the sum of the atomic radii of these two elements (), indicating that they do not form bonds.

The conventional cell of and the hexagonal representation of are found to be similar and are arranged layer by layer in the sequence of ⋯⋯ (Figure 1a,b). The difference is the type of hybridization of carbon atoms. As observed in the lattice parameters of in Table 1, although the bond (1.645 Å) has a slightly longer bond length than the normal single bond (1.52–1.58 Å) [31], and the bond length (1.468 Å) is much longer than the general cyano carbon-nitrogen triple bond , the bond angles ∠CCC, ∠CCN, ∠CNA, and ∠ANA are both close to the sp3 hybrid bond angle of 109°. It is determined that all of the carbon and nitrogen atoms in Si(CN)2 are sp3 hybridized. When combined with the previously described C(sp2)−N(sp3) bond in , there are four types of bonds, and the order of bond length from long to short is related to the degree of hybridization: (1) Both carbon and nitrogen are hybridized C()() such as - (1.468 Å); (2) carbon is hybridized and nitrogen is C()() such as - (1.343 Å); (3) both atoms are hybridized C()() such as - and (1.279 and 1.270 Å, respectively) [4]; (4) both atoms are hybridized C()() such as - and (1.182 and 1.183 Å, respectively) [4].

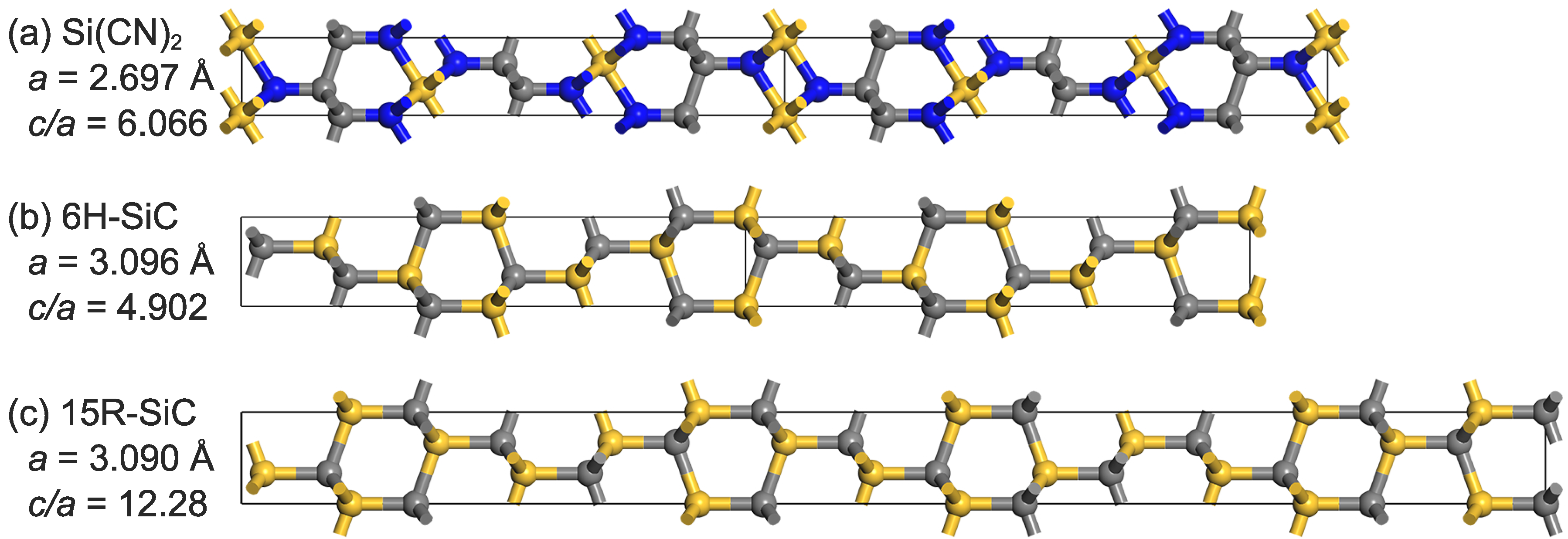

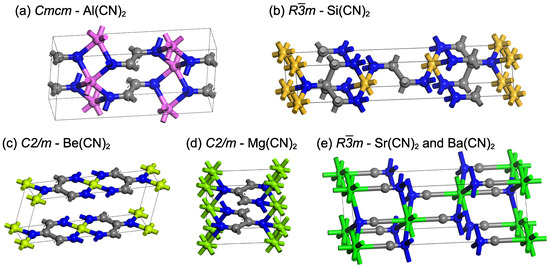

In addition, the structure of is quite similar to that of 6H- and 15R-. is comparable to 6H- when four hexagons are used as reference points (see Figure 2), while the ratio of 15R- is roughly twice that of . For both 6H- and 15R-, as well as , all atoms in the structure are hybridized in orbitals. For similar structures, is believed to exhibit some mechanical properties similar to . Aside from shortening the A side of the lattice, the addition of nitrogen atoms may change some properties. For example, films have higher scratch-and-wear resistance than [32], and other silicon carbonitrides have properties such as high piezoresistivity [33], different hardness, and an elastic modulus [34].

Figure 2.

A top view of the a-axis showing (a): , (b): 6H-, and (c): 15R-.

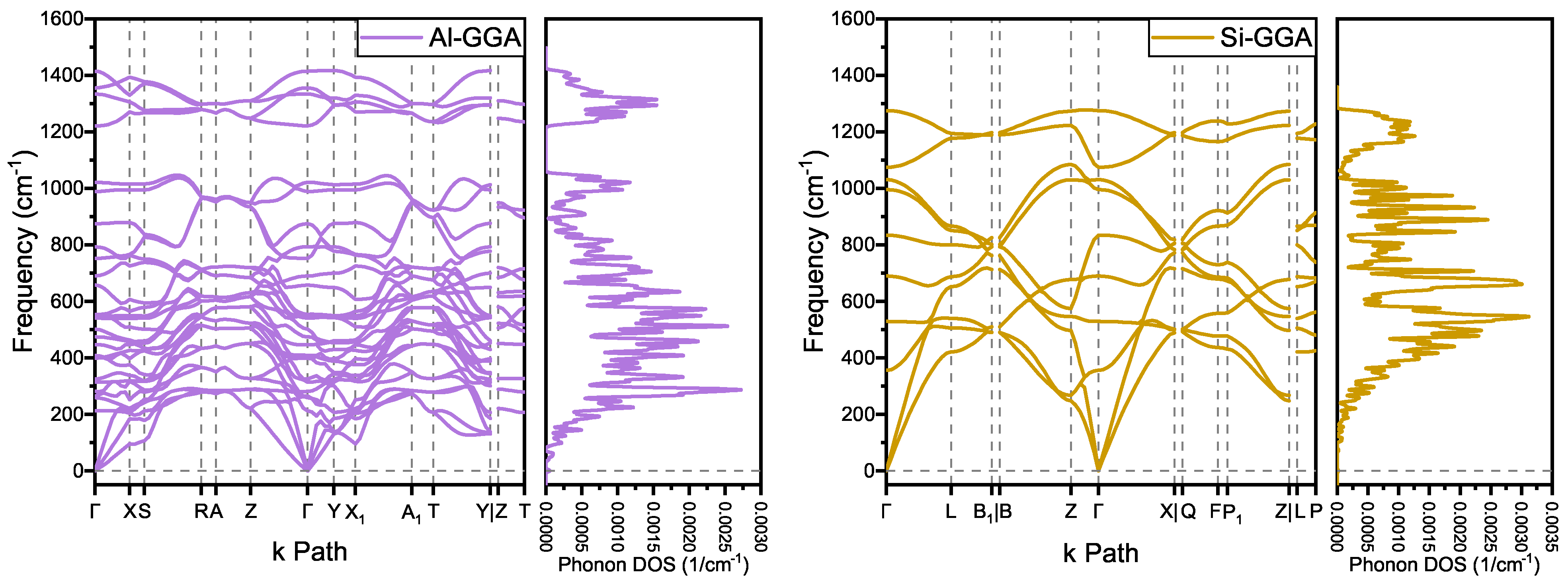

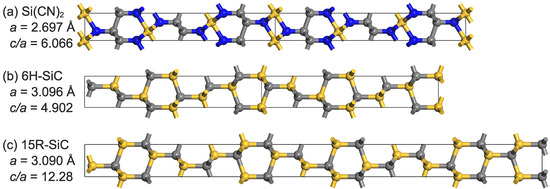

3.2. Phonon and Electrical Properties

The phonon spectra of and are shown in Figure 3. There are no imaginary frequencies, indicating that both structures are dynamically stable. As a reference comparison, and of the structure and and of the structure also have no imaginary frequencies at zero pressure. For , which is also an structure, the lowest frequency of point B in the Brillouin zone of its phonon spectrum is 490 cm, which is much greater than that of at 70 cm and at 65 cm[4]. Moreover, - of the same period has imaginary frequencies. This implies that has a higher binding energy and a more stable structure.

Figure 3.

Phonon dispersion and phonon density of states spectra of and .

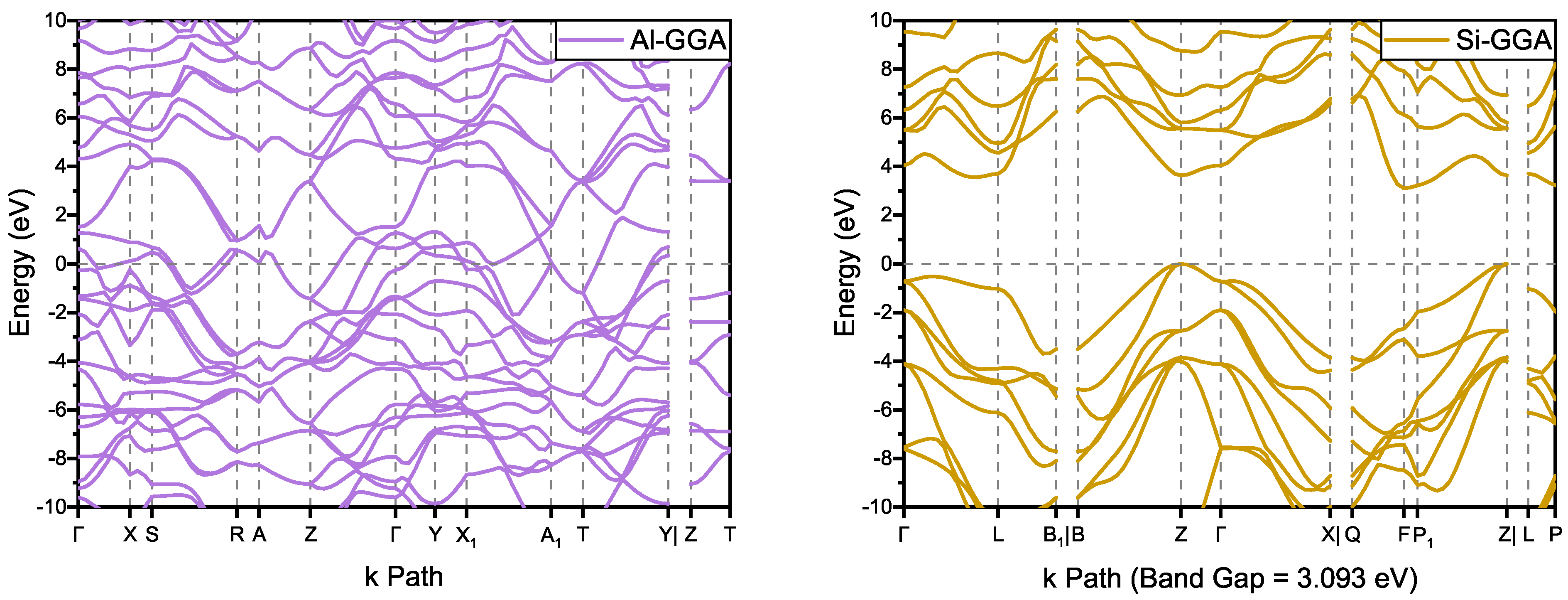

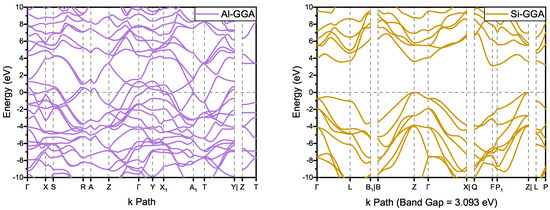

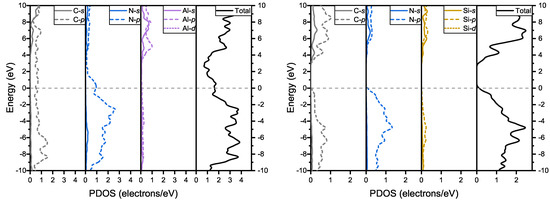

According to the band structure shown in Figure 4, has metallic properties similar to the structure of and , which is thought to be caused by the conjugated carbon chain structure. On the other hand, has an indirect bandgap of 3.093 eV with the GGA functional (see Table S1 and Figure S1: 3.048 and 4.551 eV for the LDA and HSE06 functionals, respectively). Compared with 4.143 eV for and 4.122 eV for , the bandgap of is smaller. However, it is larger than the 2.01 eV of 6H- [35]. Since the experimental bandgap of 6H- is 3.02 eV [36] and the calculated bandgap using GGA functional is an underestimate, we assume that is a wide-bandgap semiconductor.

Figure 4.

Band structures of and .

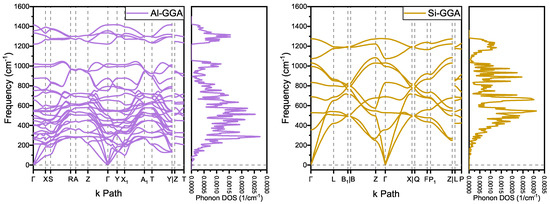

In the partial density of states (PDOS) of and , shown in Figure 5, the p electrons of carbon and nitrogen play a key role near the Fermi level in both structures. In , the p electrons of nitrogen and carbon mainly compose the band which passes through the Fermi level. In , the top of the valence band is mainly composed of p electrons of nitrogen and carbon, whereas the bottom of the conduction band is mainly composed of p electrons of carbon.

Figure 5.

Total density of states and partial density of states of and .

3.3. Population Analysis

To further investigate the bonding characteristics of the two compounds, we performed Mulliken population analysis [37], and the results are presented in Table 2. The bond population in is 2.05, indicating a strong covalent bond, and the bond population is 0.95, which is also indicative of covalent bonding characteristics [38]. The two bonds have ionic bond characteristics, with the bond at 2.009 Å having stronger ionic bonding properties. In , the bond population is even greater, indicating stronger covalent bonding properties, whereas the covalent nature of the bond is weakened and tends towards ionic bonding properties, and the bond is covalent. This implies that the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom is donating electrons to the carbon atom, i.e., the nitrogen atom exerts an electron-donating effect on the carbon atom. This increases the electron density of the carbon atom and hence lengthens the single bond.

Table 2.

Mulliken bond population analysis of and .

3.4. Elastic Property

To investigate the potential use of as a hard material similar to , we calculated its elastic constants, which are presented in Table 3. Elastic constants of , 6H-, and 15R- are also included for comparison. All compounds meet the mechanically stable criteria of the hexagonal system [39]:

Table 3.

Elastic constants of , , 6H-, and 15R-. B is the bulk modulus, G is the shear modulus, and E is Young’s modulus. All units are GPa.

The results show that the moduli of , including the bulk modulus, shear modulus, and Young’s modulus, are significantly greater than those of both 6H- and 15R-. Specifically, the bulk modulus of (347.7 GPa) is 163.5% and 165.7% that of 6H- (212.7 GPa) and 15R- (209.9 GPa), respectively. The shear modulus of (354.0 GPa) is 190.5% and 192.0% that of 6H- (185.8 GPa) and 15R- (184.4 GPa), respectively. The Young’s modulus of (792.8 GPa) is 183.7% and 185.3% that of 6H- (431.6 GPa) and 15R- (427.9 GPa), respectively. These results may be due to the introduction of nitrogen, which leads to a harder material [32,42]. Therefore, has the potential to be used in systems as a hard material. It may be a potential substitute for SiC in applications involving high-temperature and high-stress conditions. Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, the elastic constants of are mostly smaller than those of , which is consistent with the phonon spectra results.

4. Conclusions

We have selected two candidate materials through the calculation of cohesive energies of CGCNN. After the structural optimization by DFT, we consider them to be dynamically stable and mechanically stable based on the calculation of phonon and elastic constant, respectively. The structures and physical properties of - and - are also studied.

The structure of is similar to the space group of and . The structure of is similar to that of and . There are four types of bonds and the order of bond length is related to the degree of hybridization.

The band structure and density of state calculations thus suggest that is an indirect wide-bandgap semiconductor with a bandgap of 3.093 eV as per GGA, whereas has metallic properties. The p electrons of carbon and nitrogen play a key role near the Fermi level in both structures. Wide-bandgap semiconductors can operate at higher voltages and temperatures with greater efficiency and better thermal stability.

In the comparison of elastic constants, is harder than both 6H- and 15R- due to the introduction of nitrogen, so may be used as a hard material in SiCxNy systems. It may have high thermal conductivity, chemical stability, and durability in hightemperature and high-pressure environments. Due to its wide bandgap and relatively hard properties, Si(CN)2 may have widespread applications in equipment operating under extreme conditions, such as high-temperature and high-pressure sensors. It thus makes a promising candidate for use in next-generation power devices and high-frequency applications. Just like other wide-bandgap materials such as SiC, GaAs, AlGaN, and GaN, Si(CN)2 has the potential to be used in lasers, LED lighting, and RF signal processing due to its similarly wide bandgap, thus offering the potential for use in a broad range of applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst13050824/s1, Figure S1: The unit-cell structure diagrams of (a) primitive cell structure of -, (b) rhombohedral representation of -, (c) primitive cell structure of -, and (d) rhombohedral representation of - and . Gray: carbon; Blue: nitrogen; Purple: aluminum; Yellow: silicon; Green: alkaline earth metal; Figure S2: Band structures of and with different functional; Figure S3: Total density of states and partial density of states of and with LDA functional; Figure S4: Total density of states and partial density of states of and with HSE06 functional; Table S1: Lattice parameters of - (shown in primitive cell, ) and - (rhombohedral representation, ) with different functional; is the cohesive energy; Table S2: Atomic coordinates of and ; Table S3: Atomic coordinates of 6H- and 15R-; Table S4: Mulliken atomic population analysis of the and .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-I.T., C.-P.T. and T.S.; methodology, S.-I.T., P.-K.L. and C.-P.T.; software, S.-I.T. and P.-K.L.; validation, C.-P.T. and P.-K.L.; formal analysis S.-I.T., P.-K.L., C.-L.T., W.-H.L. and K.-V.T.; investigation, C.-P.T., T.S. and W.-H.L.; data curation, S.-I.T. and P.-K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-I.T., P.-K.L., C.-P.T. and T.S.; writing—review and editing, S.-I.T., P.-K.L., T.S., C.-P.T., K.-V.T. and K.-T.U.; visualization, S.-I.T., P.-K.L. and C.-L.T.; supervision, C.-P.T. and K.-T.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) of Macau [Grants 0111/2020/A, 0048/2020/A1, 0105/2020/A3, 0014/2022/A1, and 0122/2022/A. File No. SKL-LPS(MUST)-2021-2023], and partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 41974099).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bo-Chi Cha for her assistance in editing the article format.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CGCNN | Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| CASTEP | Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package |

| GGA | Generalized Gradient Approximation |

| LDA | Local Density Approximation |

| PDOS | Partial Density of States |

References

- Williams, D.; Pleune, B.; Leinenweber, K.; Kouvetakis, J. Synthesis and structural properties of the binary framework C–N compounds of Be, Mg, Al, and Tl. J. Solid State Chem. 2001, 159, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, J.; Schleyer, P.v.R. M(CN)2 Species (M = Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba): Cyanides, Nitriles, or Neither? Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, D.S.; Dasgupta, R.; Sun, C.; Tsuno, K.; Costin, G. Delivery of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur to the silicate Earth by a giant impact. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, P.K.; Sekine, T.; Tam, K.V.; Tam, S.I.; Tang, C.P. First-Principles Calculations with Six Structures of Alkaline Earth Metal Cyanide A(CN)2 (A = Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, and Ba): Structural, Electrical, and Phonon Properties. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 2973–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, K.; Iwamoto, Y.; Fisher, C.A.; Matsubara, H. Molecular dynamics study of atomic structures in amorphous Si-CN ceramics. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 1999, 107, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Grossman, J.C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ye, W.; Zuo, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ong, S.P. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3564–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Wolverton, C. Developing an improved crystal graph convolutional neural network framework for accelerated materials discovery. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 063801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Philip, S.Y. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, P.K.; Tam, S.I.; Leong, W.H.; Sekine, T.; Tam, K.V.; Tang, C.P. Unpublished Work. State Key Laboratory of Lunar and Planetary Sciences, Macau University of Science and Technology, Taipa, Macao 999078, China. 2023; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, L.; Cho, H.G.; Gong, Y. Reactions of Laser-Ablated Aluminum Atoms with Cyanogen: Matrix Infrared Spectra and Electronic Structure Calculations for Aluminum Isocyanides Al(NC)1,2,3 and Their Novel Dimers. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 5342–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Schaefe, H.F., III. Spectroscopic constants and potential energy surfaces for the possible interstellar molecules A1NC and A1CN. Mol. Phys. 1995, 86, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, A. Equilibrium Structure and Stability of AlCn (n = 2, 3) and AlCnN (n = 1, 2) Species. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 9275–9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchenko, V.; Kozak, A.; Porada, O.; Ivashchenko, L.; Sinelnichenko, O.; Lytvyn, O.; Tomila, T.; Malakhov, V. Characterization of SiCN thin films: Experimental and theoretical investigations. Thin Solid Film. 2014, 569, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Shao, C.; Wang, J. Continuous SiCN fibers with interfacial SiC x N y phase as structural materials for electromagnetic absorbing applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 22885–22894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M. Universal variational functionals of electron densities, first-order density matrices, and natural spin-orbitals and solution of the v-representability problem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 6062–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, M.; Lindan, P.J.; Probert, M.a.; Pickard, C.; Hasnip, P.; Clark, S.; Payne, M. First-principles simulation: Ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.J.; Segall, M.D.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Probert, M.J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr.-Cryst. Mater. 2005, 220, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceperley, D.M.; Alder, B.J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 1981, 23, 5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 7892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G.E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 8207–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, D.; Schlüter, M.; Chiang, C. Norm-conserving pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 43, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrommer, B.G.; Cote, M.; Louie, S.G.; Cohen, M.L. Relaxation of crystals with the quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 131, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignitti, M.; Tosato, M. The relative stabilities of isomeric HCN dimers. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1977, 4, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementi, E.; Raimondi, D.; Reinhardt, W.P. Atomic screening constants from SCF functions. II. Atoms with 37 to 86 electrons. J. Chem. Phys. 1967, 47, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, R. Carbon—carbon bond lengths. Science 1952, 116, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomastik, J.; Ctvrtlik, R.; Ingr, T.; Manak, J.; Opletalova, A. Effect of nitrogen doping and temperature on mechanical durability of silicon carbide thin films. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xu, W.; Fang, D.; Zhai, L.; Lin, K.C.; An, L. A silicon carbonitride ceramic with anomalously high piezoresistivity. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 1346–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, W.; Song, L. Mechanical properties of silicon carbonitride thin films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 42, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Xu, P.; Xu, F.; Pan, H.; Li, Y. First-principles studies of the electronic and optical properties of 6H–SiC. Physical B 2003, 336, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, E.; Bell, M.; Anjos, V. Ab initio calculations of some electronic and elastic properties for SiC polytypes. Intermetallics 2008, 16, 1040–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliken, R.S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. I. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, M.; Shah, R.; Pickard, C.J.; Payne, M. Population analysis of plane-wave electronic structure calculations of bulk materials. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 16317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M. On the stability of crystal lattices. I. In Proceedings of the Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1940; Volume 36, pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Hao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yun, S. Si–C alloys with direct band gaps for photoelectric application. Vacuum 2022, 199, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitani, K.; Grimsditch, M.; Nipko, J.; Loong, C.K.; Okada, M.; Kimura, I. The elastic constants of silicon carbide: A Brillouin-scattering study of 4H and 6H SiC single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 82, 3152–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, F.; Fazio, E.; Neri, F.; Trusso, S. Electronic properties of PLD prepared nitrogenated a-SiC thin films. Thin Solid Films 2003, 433, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).