Abstract

The dry reforming of methane (DRM) is a kind of technology used for achieving resource utilization. In this paper, different Ni/SBA-15 catalysts were prepared by adjusting the pH of the impregnation solution and applying it during the DRM reaction. The relationship between the structure and catalytic performance of the catalyst was analyzed by characterization methods such as BET, XRD, H2-TPR, H2-TPD, XPS, TG, and Raman. The research results indicated that the dispersion of the catalyst’s active components could be regulated by changing the pH value of the impregnation solution. Among them, the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst exhibits good metal dispersion, and significantly enhances the activity of the catalyst. In addition, it also has strong CO2 adsorption capacity, which improves the stability of the catalyst. At 700 °C, the conversions of CH4 and CO2 of the catalyst are 51% and 60%, respectively.

1. Introduction

Due to the excessive use of fossil fuels, the concentration of greenhouse gases has significantly increased in the atmosphere, leading to serious environmental problems [1]. Therefore, achieving the conversion and utilization of greenhouse gases has certain environmental benefits. The dry reforming of methane (DRM) is a promising process that can convert CH4 and CO2 into syngas (H2 and CO), achieving effective utilization of greenhouse gases [2,3]. Moreover, the H2/CO ratio produced is usually close to 1 in this process. It is an ideal material for Fischer–Tropsch (F-T) synthesis and can be used for the production of hydrocarbon fuels [4].

In the DRM reaction, Ni-based catalysts with high activity and low costs have received widespread attention. However, since the main reaction of DRM is strongly endothermic, this reaction is usually carried out at higher temperatures. Therefore, the active components will be sintered at high temperatures, resulting in deactivation of the catalyst [5]. In addition, due to side reactions such as the Boudouard reaction and methane cracking, carbon deposits will form in the reaction, causing rapid deactivation of the catalyst and even blockage of the reactor [6,7].

Ni-based catalysts with small particle sizes have been shown to have high resistance to sintering and carbon deposition [5,8]. Kim [9] et al. studied Ni-aluminum aerosol catalysts with different Ni loadings and found that the size of Ni particles is closely related to the formation of carbon deposits on the catalyst. When the size of Ni particles is greater than 7 nm, filamentous carbon is mainly formed on the surface of the catalyst. Peng [10] et al. have shown that the catalyst’s resistance to sintering and carbon deposition can be improved if the particle size of Ni is controlled below 5 nm in Ni/DMS catalysts. Joung [11] et al. found that catalysts with smaller particle sizes can significantly increase the conversion frequency of CH4 compared to catalysts with larger particles. Zhang [12] et al. synthesized a series of Ni/MSS catalysts using different preparation methods. The results indicate that reducing the size of Ni particles can expose more active sites and improve the activity and resistance to carbon deposition of the catalyst.

One of the effective strategies to reduce the size of Ni particles is to increase the dispersion of active components. According to current research findings, the complexation of organic ligands with metals can significantly improve the dispersion of active components, reduce the particle size of active components, and thereby inhibit the sintering of active components [13]. Recently, a study compared the effects of different complex ligand-assisted impregnation solution, such as ethylenediamine, citric acid, and acetic acid [14]. The results indicate that a catalyst with assisted impregnation helps to improve the dispersibility of the active Ni component and exhibits excellent catalytic performance. Yang [15] et al. prepared a series of catalysts using glycine-assisted impregnation and used them in DRM reactions. The results showed that the Ni/SiO2-0.7G catalyst had the best catalytic performance, and the amount of carbon deposition produced was significantly lower than that of the Ni/SiO2-0G catalyst. Mamoona [16] et al. investigated the effect of citric acid concentration on the catalytic performance of catalysts. Regardless of the concentration of citric acid, the Ni particle dispersion of the catalyst is improved, exhibiting superior and stable catalytic performance in DRM reactions.

However, these studies mainly focus on the effects of different organic ligand-assisted impregnation solution or the concentrations of organic ligands on DRM reactions. The effect of the impregnation solution on the surface charge properties of the support and the dispersion of active components has not been thoroughly studied in DRM reactions. Regalbuto [17] et al. believe that the pH value of the impregnation solution can affect the metal–support interaction and improve the dispersion of the active components. By adjusting the pH value of the impregnation solution, a series of highly dispersed precious metal and non-precious metal catalysts were obtained. The results indicate that well-dispersed metals can be synthesized on amorphous silica utilizing electrostatic adsorption theory. Li [18] et al. synthesized a series of Co/ZrO2 catalysts by adjusting the pH values of different impregnation solutions, and applied them in CO2 methanation reactions. The results indicate that the dispersion of Co metal can be changed by adjusting the pH value of the impregnating solution.

In this paper, different Ni/SBA-15 catalysts were prepared by adjusting the pH value of the impregnation solution, and their catalytic performance was compared. The relationship between the physicochemical properties and catalytic performance of Ni/SBA-15 catalyst was investigated using characterization methods such as BET, XRD, H2-TPR, H2-TPD, CO2-TPD, FTIR, and XPS.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physical Properties of Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst

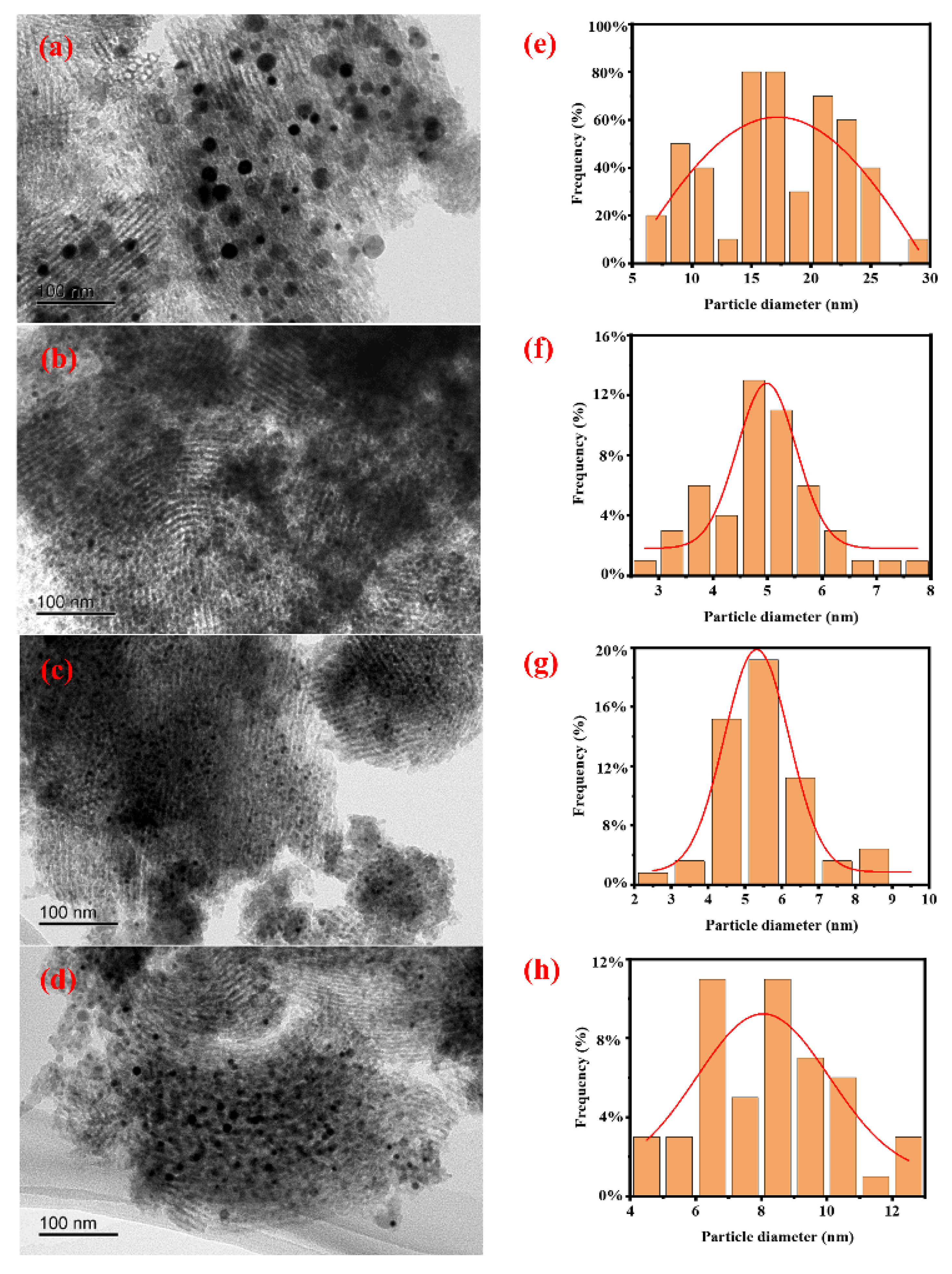

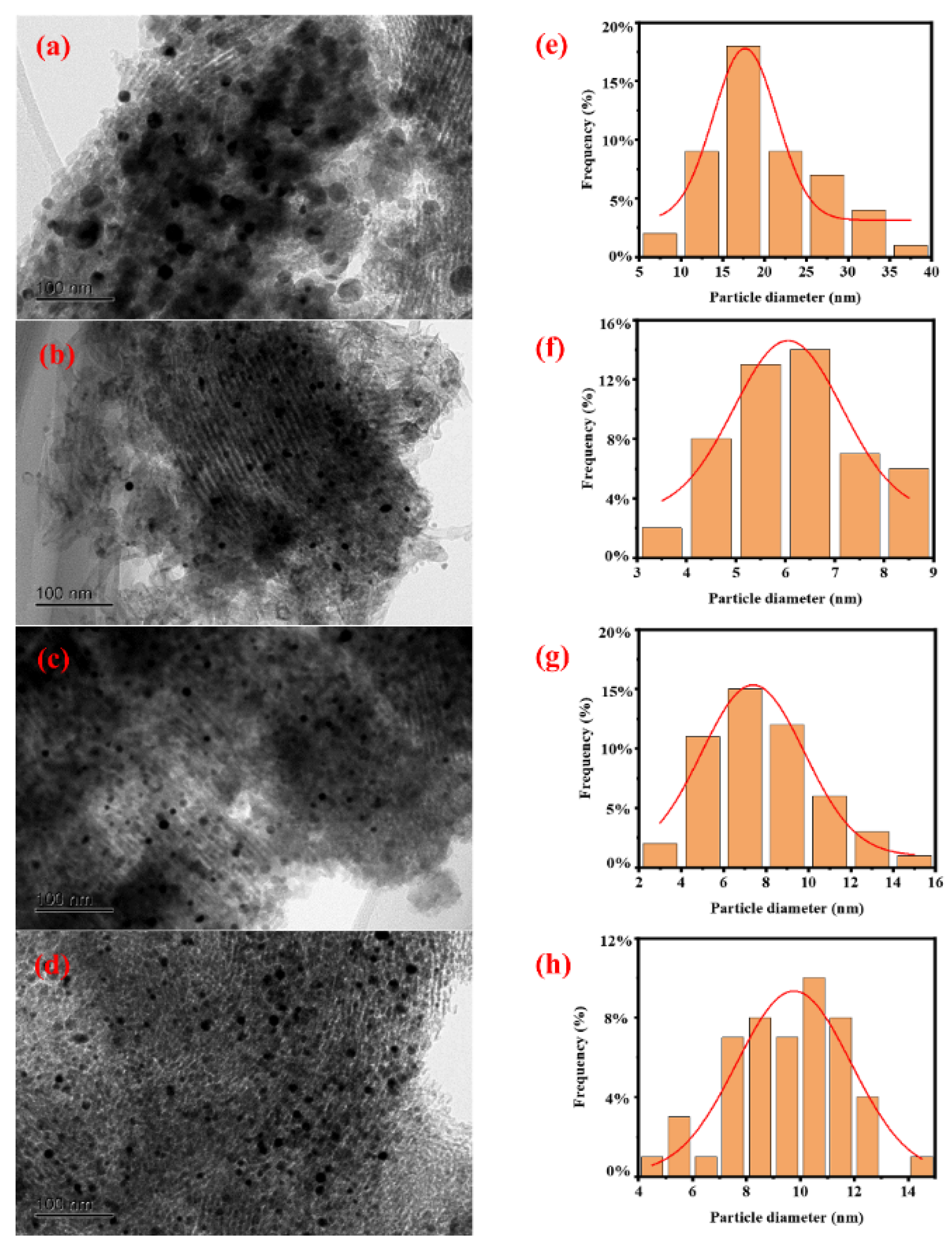

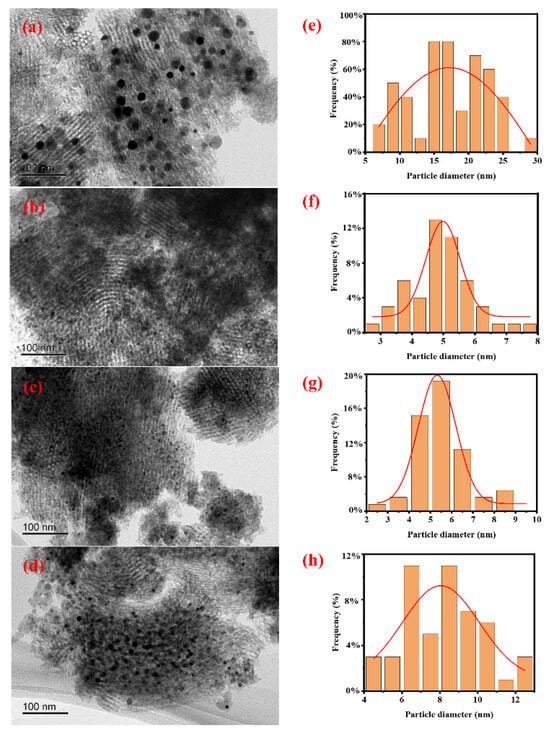

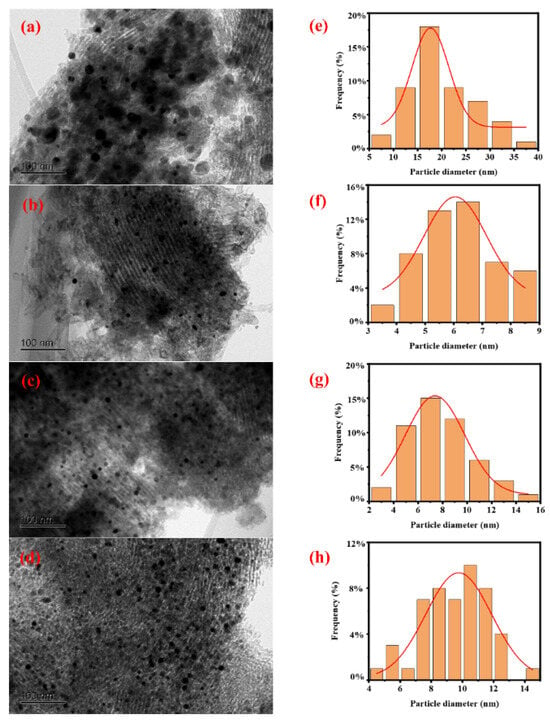

The morphology of all catalysts and the particle size distribution of Ni particles were characterized by TEM, and the results are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that Ni particles are loaded onto the SBA-15 support, and there is no significant difference in the morphology of all catalysts. From the Ni particle size distribution diagram, it can be seen that the degree of Ni particle dispersion varies in different catalysts. The average particle size of Ni particles was further calculated based on TEM characterization, and the results are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that the average size of Ni in catalysts Ni/SBA-15, Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 is 17.2 nm, 4.9 nm, 5.3 nm, and 8.1 nm, respectively.

Figure 1.

TEM images and Ni particle size distributions of the (a,e) Ni/SBA-15, (b,f) Ni/SBA-15-2, (c,g) Ni/SBA-15-6, and (d,h) Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts.

Table 1.

Textural parameters of support and different catalysts.

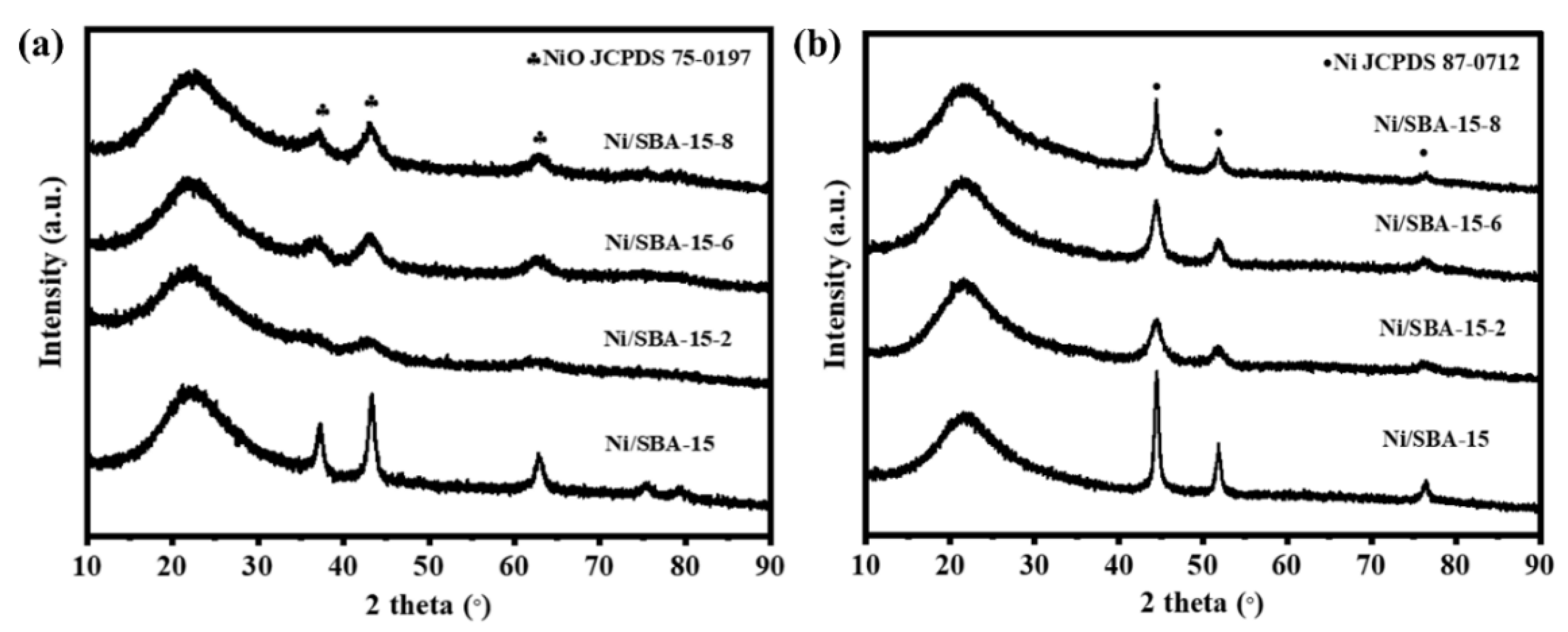

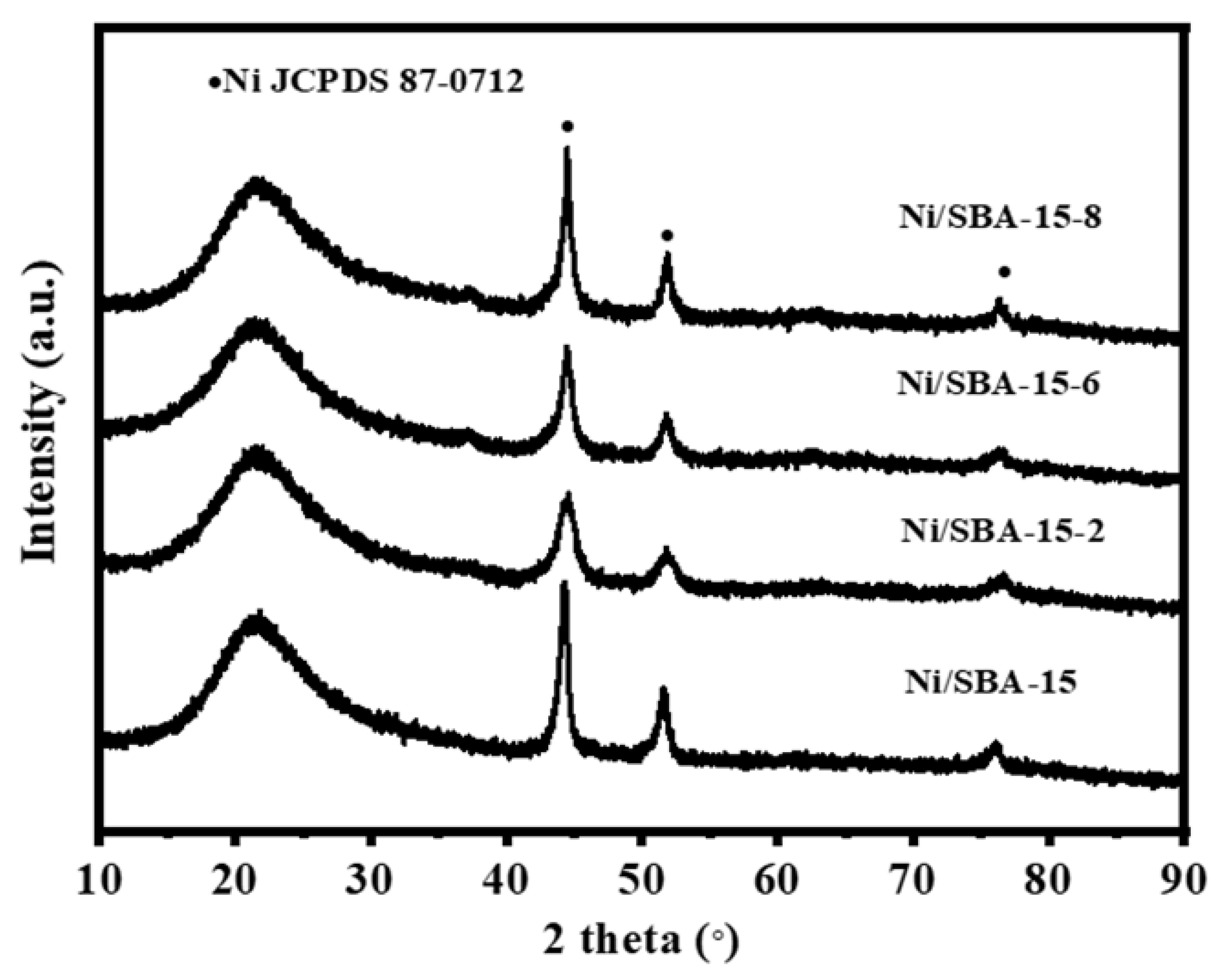

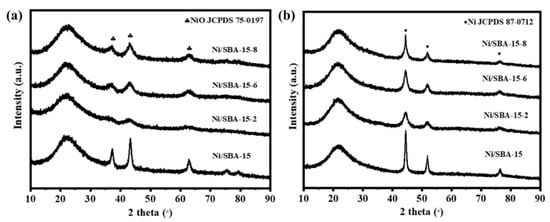

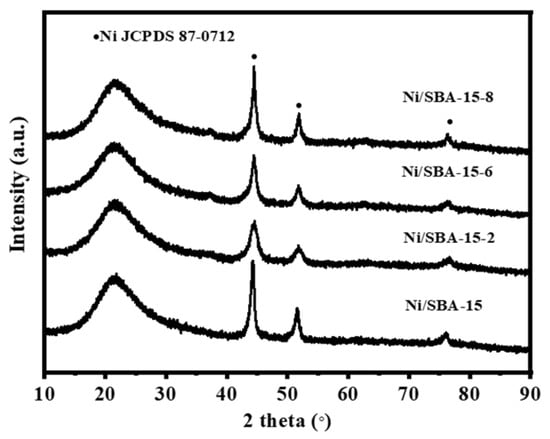

Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of the calcined and reduced catalysts. A broad peak can be observed at 2θ = 21° for all catalysts, which is attributed to the diffraction peak of amorphous SiO2 [19]. There are obvious diffraction peaks (JCPDS 89-7390) at 37.2°, 43.3° and 62.9°, which are attributed to the NiO species with its corresponding lattice planes of (111), (200), and (220). It is found that the NiO diffraction peak intensity of the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst is the highest. The results show that the assisted impregnation can help to improve the dispersion of NiO species [20]. As can be seen from Figure 2b, strong diffraction peaks were observed at 44.5°, 51.8°, and 76.4° (JCPDS 87-0712), which are attributed to the Ni species with its corresponding lattice planes of (111), (200), and (220) [21]. According to the Scherer formula, the crystallite size of Ni on all catalysts was calculated, as shown in Table 1. The average particle size of the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst is 11.2 nm, while the average sizes of Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 are 4.6 nm, 5.8 nm, and 8.7 nm, respectively. Although not completely consistent with the TEM results, the Ni particle size on the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst is the smallest regardless of the characterization method used.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of (a) calcined and (b) reduced different catalysts.

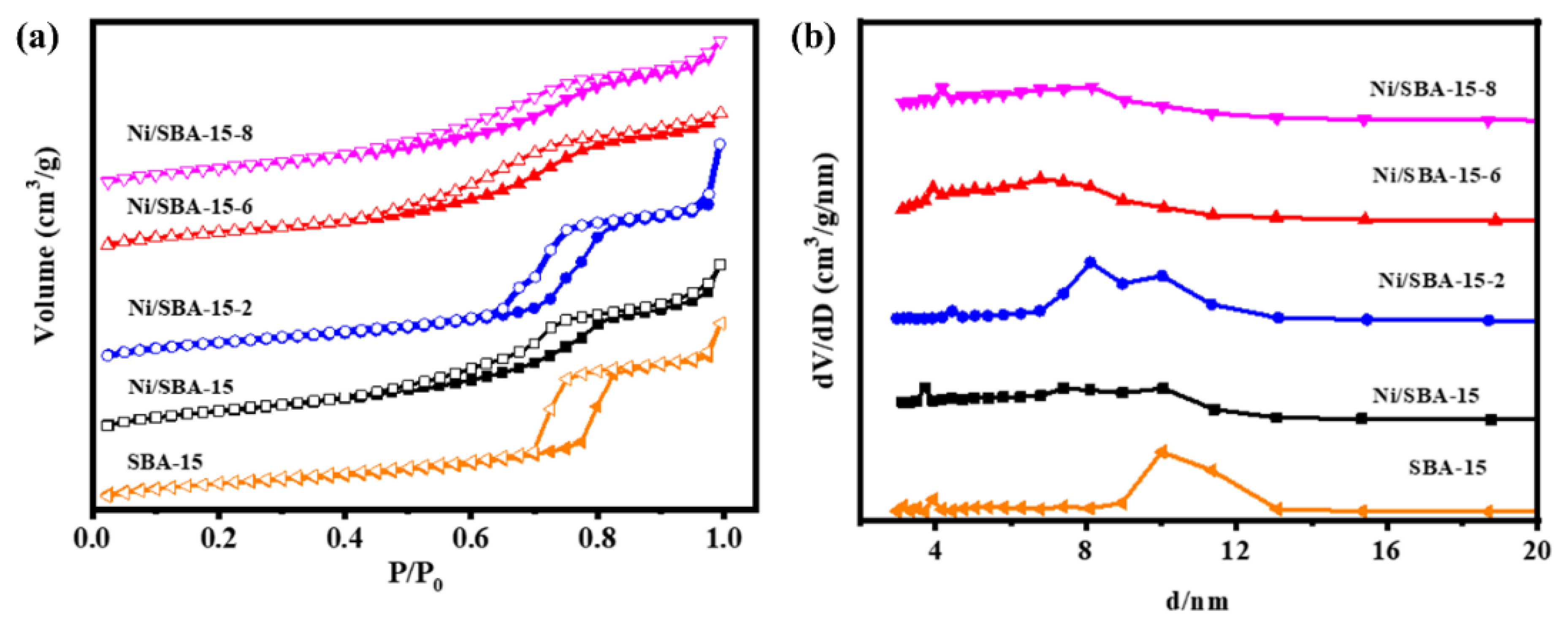

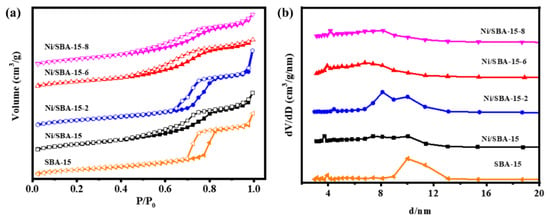

The physical structural properties of the different catalysts were compared and analyzed through N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and the research results are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that the SBA-15 and Ni/SBA-15, Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts exhibit IV-type adsorption–desorption isotherms, accompanied by H1-type hysteresis loops. Within the pressure range of 0.4~0.9, the adsorption of N2 changes sharply, which is caused by the capillary condensation in the mesoporous channel [22,23]. This indicates that all catalysts are typically mesoporous materials. The adsorption–desorption isotherms of all of the catalysts show similar types, indicating that the loading of active metal Ni does not affect the structure of the catalyst [24]. From the pore size distribution curve, it can be seen that the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst exhibits an obvious bimodal mesopore. Table 1 shows the texture parameters of all of the catalysts. Compared with the specific surface area (484.9 m2/g) and pore volume (1.48 cm3/g) of SBA-15, the specific surface area (431.9 m2/g) and pore volume (1.31 cm3/g) of the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst decreased the least. This may be because the nickel particles of the catalyst have the smallest size and hardly block the pores of the SBA-15 support [12,25].

Figure 3.

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and (b) BJH pore size distributions of supports and different catalysts.

In order to further understand the chemical structure of the active components and support, FTIR characterization was performed on the catalysts, and the results are shown in Figure S1. It can be observed that all catalysts exhibit obvious absorption peaks at 1080 cm−1, 808 cm−1, and 467 cm−1, which are attributed to the asymmetric stretching, symmetric stretching, and bending vibrations of Si-O-Si in the SBA-15 framework, respectively [19,26]. The absorption peaks that appear at 3424 cm−1 and 1630 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching and bending vibrations of O-H in adsorbed water molecules [27]. The peak located at 979 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric vibration of Si-OH [28,29]. It is worth noting that the peak intensity of the catalysts at 979 cm−1 slightly decreased after adjusting the pH value of the solution compared with SBA-15 and Ni/SBA-15. It indicates that the active metal is loaded onto the support and the Si-O-Ni bond is formed.

In order to clarify the reason why the pH value of the impregnation solution affects the metal dispersion of the catalysts, the variation in the Zeta potential on the surface of silica with different pH values of the solution was tested. The experimental results are shown in Figure S2. Researchers have shown that silicon dioxide carries different charges in solutions with different pH values [30]. Among them, PZC represents the pH value at which the surface charge of silicon dioxide is zero [18]. By adjusting the pH value relative to the zero charge surface, the metal precursor will be strongly adsorbed on the surface of silica with opposite charges. From Figure S2, it can be seen that the PZC of SBA-15 support ranges from 3 to 4. When the pH value of the solution is higher than PZC, the surface of the support is negatively charged. When the pH value of the solution is lower than PZC, the surface of the support is positively charged. The surface of Ni-complexes (citric acid and hydroxyl) have negative charges on their surfaces [29,31]. According to the electrostatic adsorption theory, the dispersion of metals can be improved. Under alkaline conditions, nickel hydroxide precipitation and even nickel silicates may be formed. Both of these can affect the degree of dispersion.

2.2. Reduction Performance of Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst

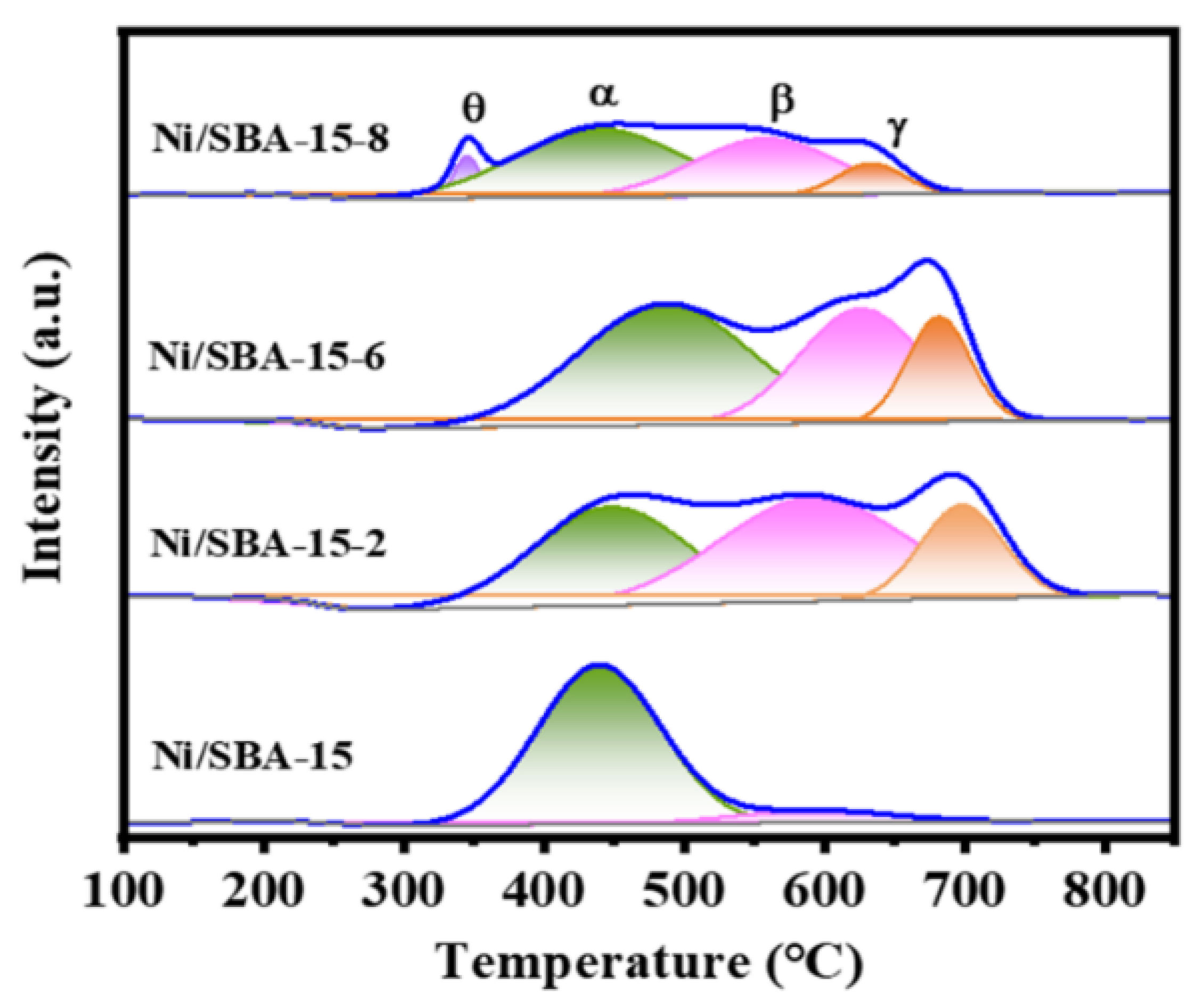

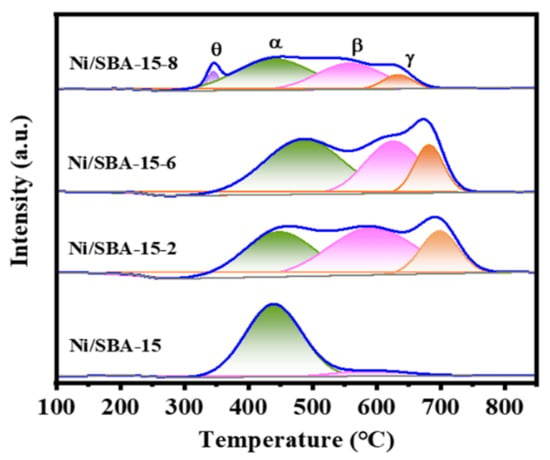

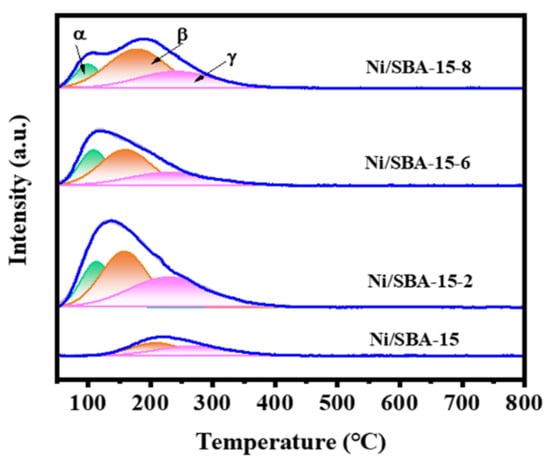

In order to study the reducibility of the active component Ni and the interaction between Ni and the support, H2-TPR characterization is shown in Figure 4. As can be seen from Figure 4, the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst exhibits two reduction peaks at 439 °C and 592 °C. Moreover, the peak area of the former is significantly higher than that of the latter, indicating that most of the active components are located on the surface of the support, rather than in the mesoporous channels [32]. According to our observations, compared to the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, the Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts exhibit γ-reduction peak. This indicates that the metal–support interaction of the catalysts is enhanced by assisted impregnation [15]. However, changing the pH value of the solution results in different interactions between the Ni and the support. Ni/SBA-15-2 and Ni/SBA-15-6 catalysts exhibit three different reduction peaks, located in the range of 350–525 °C, 525–630 °C, and 630–750 °C, respectively. The reduction peak at 525–630 °C belongs to NiO with moderate interaction with the support [33]. The reduction peak above 630 °C is the strongly interacting NiO with the support, which is usually attributed to the reduction of tiny NiO in the mesoporous channel [34,35]. In addition, the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst exhibits four reduction peaks, located at 345 °C, 439 °C, 558 °C, and 633 °C, respectively. The reduction peak δ at lower temperatures is due to the larger NiO nanoparticles located on the carrier surface, resulting in weaker metal–carrier interaction and easier reduction [36].

Figure 4.

H2-TPR curves of different catalysts.

The temperature and area calculation results after fitting the reduction peak are listed in Table 2. It can be seen that the reduction temperature of the peak γ of different catalysts has different degrees of deviation. Compared with other catalysts, the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has the highest reduction temperature. Moreover, the proportions of strong interactions between the catalysts Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 are 18.1%, 15.9%, and 8.9%, respectively. In addition, the amount of H2 consumed by the different catalysts is in the following order: Ni/SBA-15-2 (696.7 µmol/g) > Ni/SBA-15-6 (684.7 µmol/g) > Ni/SBA-15-8 (372.1 µmol/g) > Ni/SBA-15 (355.3 µmol/g). Therefore, the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst consumes the most H2.

Table 2.

The fitting results of H2-TPR.

2.3. Activation Ability of Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst for Reactants

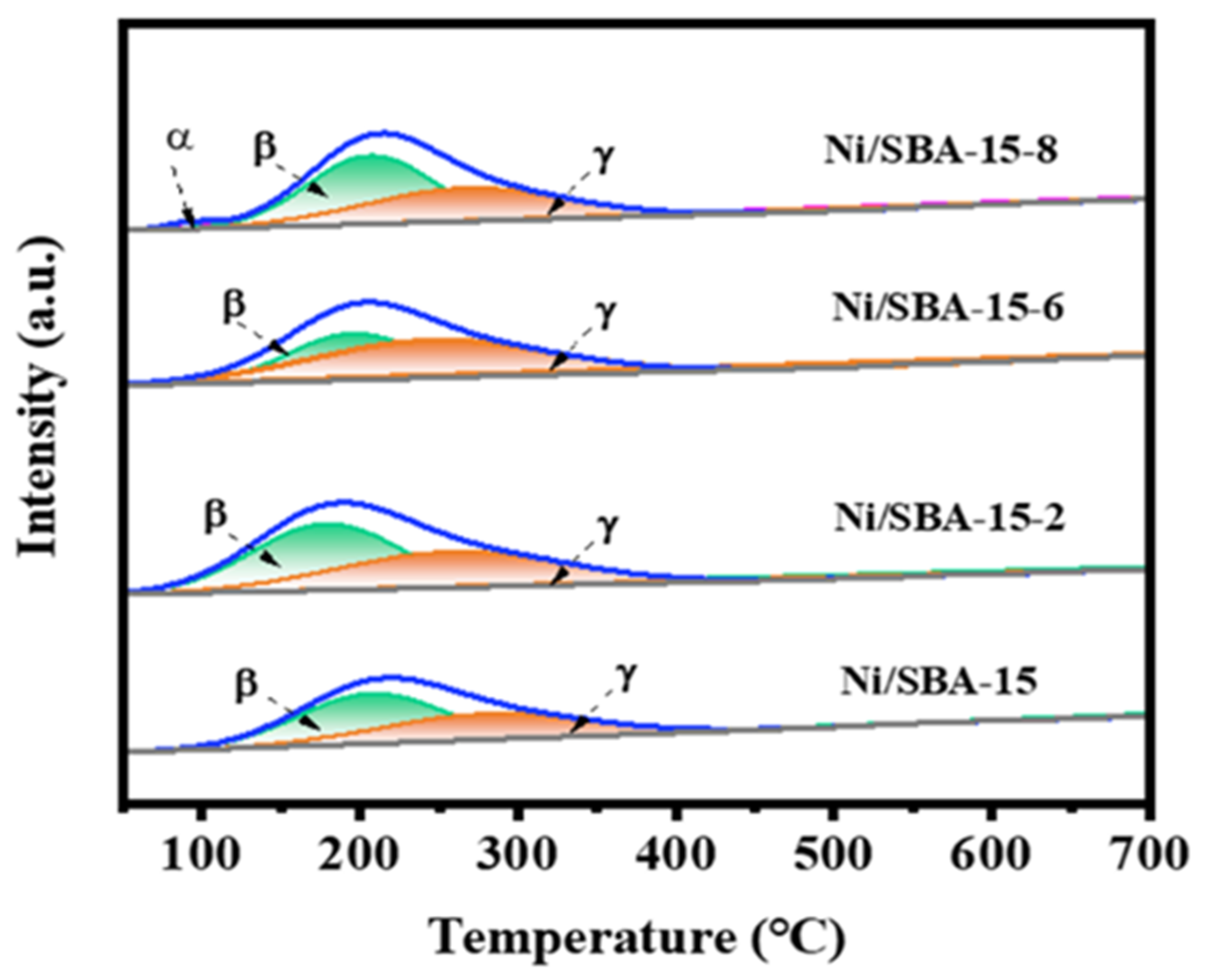

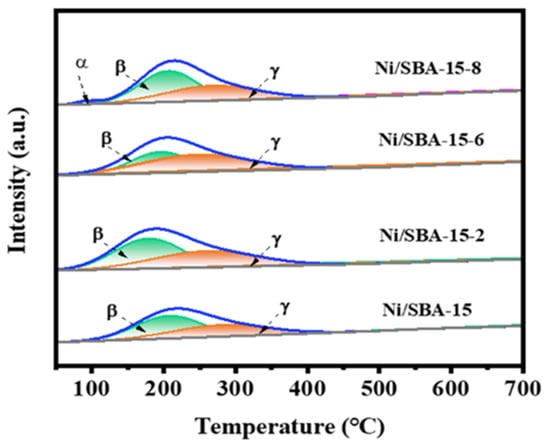

In multiphase catalytic reactions, the adsorption and activation ability of catalysts for reactants is crucial. Figure 5 shows the H2-TPD results for different catalysts. It is worth noting that there are two types of H2 desorption peaks for all of the catalysts, that is, below 200 °C and 200–400 °C. These two desorption peaks are produced by two catalytic centers on the Ni surface, which have different binding strengths for hydrogen bonds [37]. The H2 desorption peak below 200 °C is attributed to the H2 desorption adsorbed on the surface of the active metal Ni, while the H2 desorption peak at 200–400 °C is attributed to the H2 desorption peak adsorbed on the metal–support interface [38].

Figure 5.

H2-TPD curves of different catalysts.

Based on H2-TPD, the amount of desorbed H2, the surface area, and the dispersion of active metals were also calculated, and the results are shown in Table 3. For all catalysts, the dispersion of the active component Ni was in the following order: Ni/SBA-15-2 > Ni/SBA-15-6 > Ni/SBA-15-8 > Ni/SBA-15. However, it is interesting that the order of H2 desorption and metal surface area of the different catalysts is Ni/SBA-15-2 > Ni/SBA-15-8 > Ni/SBA-15-6 > Ni/SBA-15. This indicates that the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has the highest concentration of exposed active sites. This is also the reason for its highest catalytic activity. However, compared with the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst, the Ni/SBA-15-6 catalyst has a higher metal dispersion but a smaller number of exposed active sites. This may be due to the large total pore volume and adsorption capacity of the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst, which results in a higher probability of contact with the reactants, thus exposing a greater number of active sites [39].

Table 3.

The fitting results of H2-TPD.

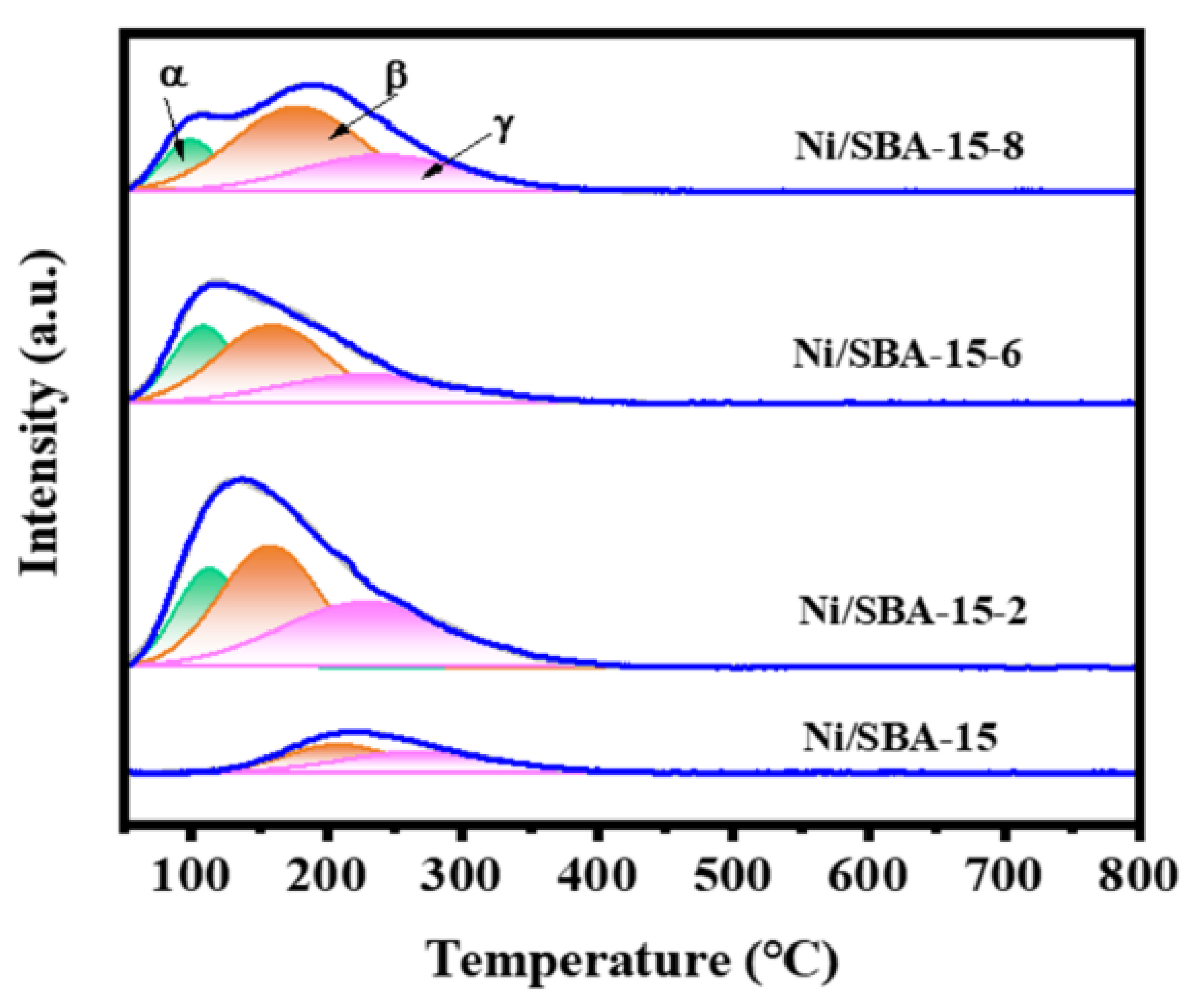

In order to explore the adsorption and desorption capabilities of different catalysts for CO2, CO2-TPD characterization is shown in Figure 6. The alkaline sites of all catalysts in different temperature ranges indicate that the catalysts have different alkalinity values [40]. Generally, the weak, medium, and strong basic sites of the catalysts are in the temperature range of below 210 °C, 210–450 °C, and above 450 °C, respectively [41,42]. According to the temperature range of the desorption peak, the α peak belongs to the desorption of physically adsorbed CO2, while the basic sites corresponding to the β and γ peaks belong to weakly basic and moderately basic sites, respectively. Table S1 shows the amount of CO2 desorption for different catalysts. The CO2 desorption of the Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts (76.1 µmol/g, 62.9 µmol/g, 65.7 µmol/g) increased compared with that of Ni/SBA-15 (53.3 µmol/g). The results indicated that the catalysts used for assisted impregnation increase the number of CO2 adsorption sites. However, the CO2 desorption capacity of the Ni/SBA-15-6 catalyst is lower than that of the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst, indicating that the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst has a relatively high adsorption capacity for CO2. In addition, the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has the highest CO2 desorption capacity, which helps to improve the conversion rate of CO2 and eliminate carbon deposits produced during the reaction process.

Figure 6.

CO2-TPD curves of different catalysts.

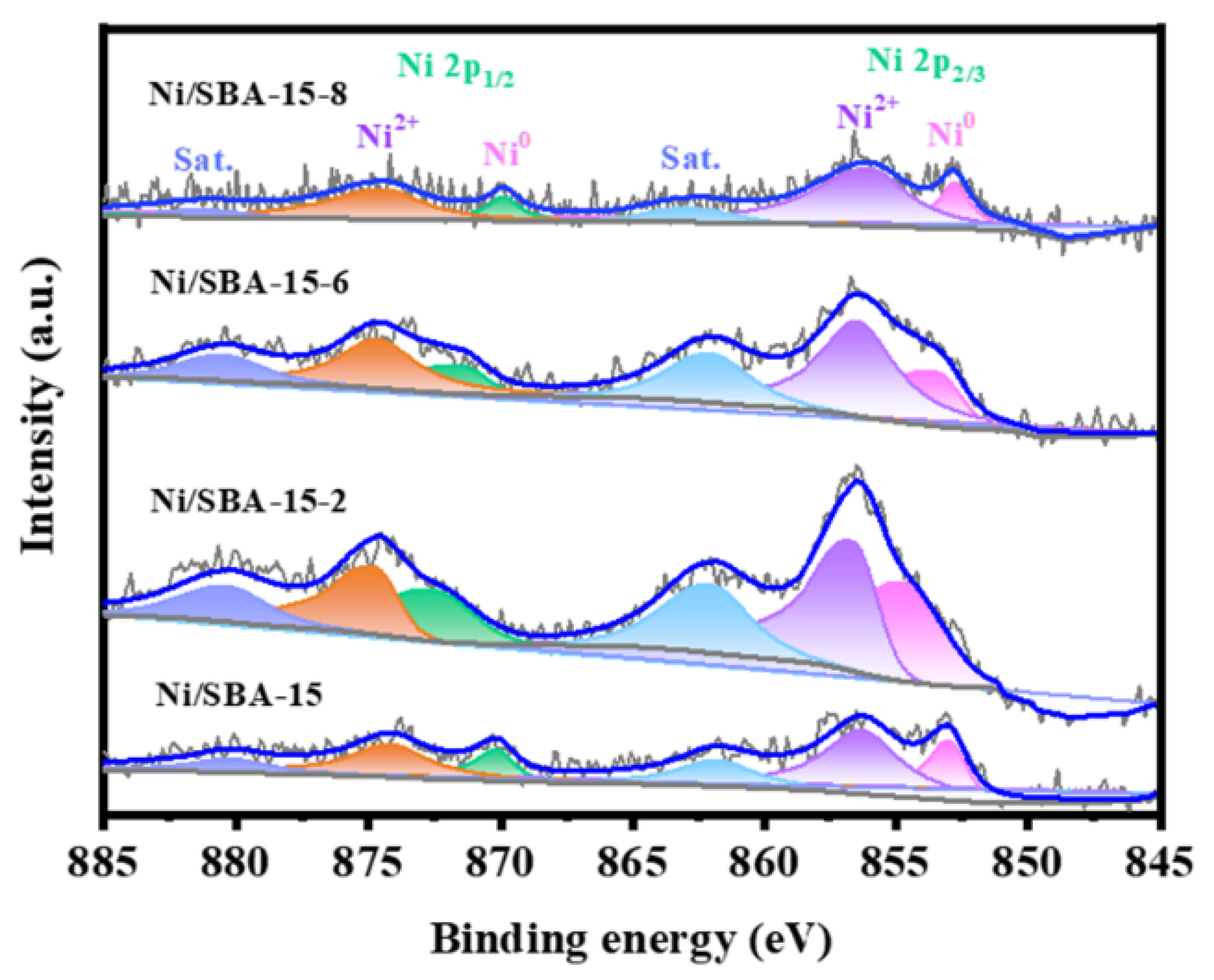

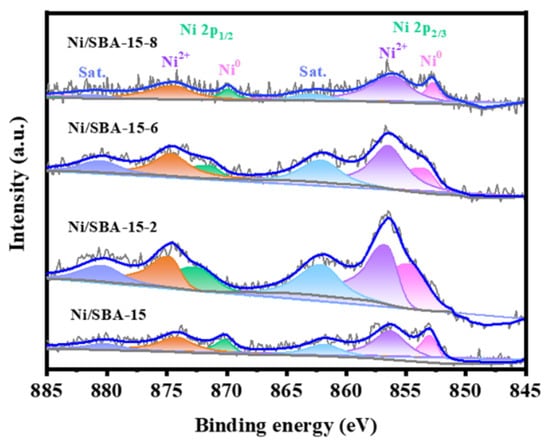

2.4. Surface Electronic Environment of Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst

XPS characterization was used to study the surface electronic environment of different catalysts, as shown in Figure 7. The Ni 2p spectra of all catalysts are split into Ni 2p1/2 and Ni 2p3/2 [43]. The fitting peaks at approximately 853 eV and 870 eV were attributed to the reduced Ni0 species, while the peaks at 856 eV and 874 eV were attributed to the Ni2+ species [44,45]. Compared with the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, the peaks for the Ni/SBA-15-2 and Ni/SBA-15-6 catalysts have higher binding energy shifts, and the former has a greater degree of shift. This is because of the high dispersion of the active components, which enhances the interaction between the metal and the support [16]. However, the peak of the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst shifts towards lower binding energy. This may be because there are some NiO species in the catalyst that have weak interactions with the support (as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of different catalysts.

In addition, the ratio of Ni0/Ni2+ was calculated to further compare the Ni0 content in the catalyst. The results are shown in Table S2. The results showed that the Ni0/Ni2+ ratio of the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst is the highest. The results showed that the Ni0/Ni2+ ratio of the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst is the highest. Meanwhile, the H2-TPD results confirmed that the catalyst also has the largest Ni specific metal surface area and H2 uptake. This indicates that it not only has a high proportion of active sites but also has the highest number of exposed active sites. Ni0 is considered the active site for the adsorption and activation of CH4 molecules [38]. The proportion of Ni0 is closely related to the initial conversion rate of CH4. This is also the main reason why the catalyst has a high initial activity.

2.5. Performance Evaluation of Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst

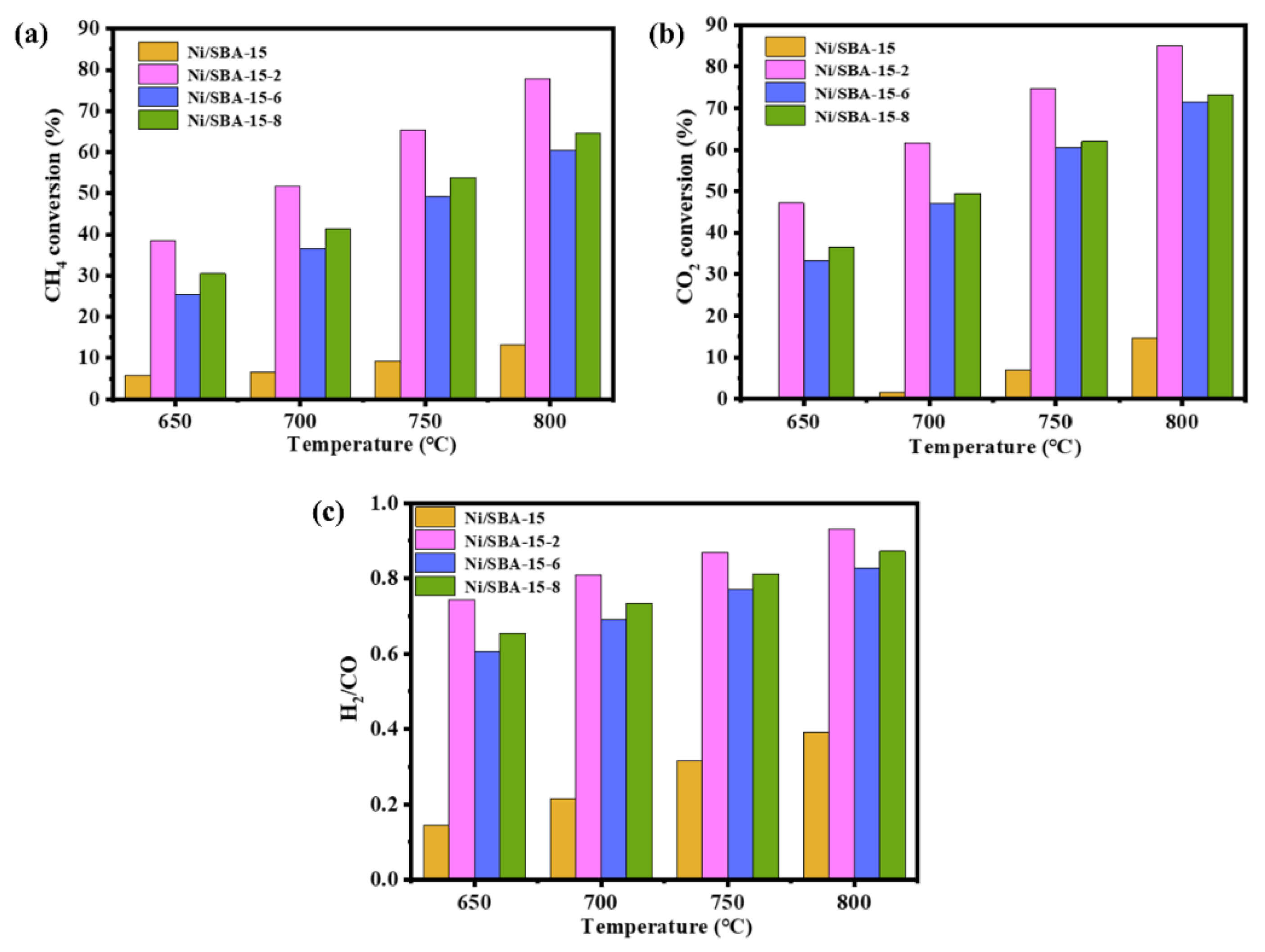

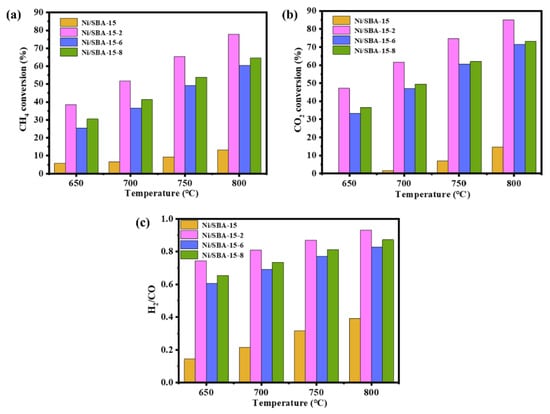

The initial activity of the Ni/SBA-15, Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts for the DRM reaction was investigated under atmospheric pressure, different temperatures (650–800 °C), and GHSV = 30,000 mL/(h·gcat). The results are shown in Figure 8. Due to the occurrence of the reverse water gas reaction (RWGS) during the reaction process, the CO2 conversions of all of the catalysts are higher than that of CH4, and the H2/CO ratio is less than 1 [46]. In addition, as the DRM reaction is a strong endothermic reaction, the CH4 and CO2 conversions of all catalysts increase with the increase in reaction temperature [47]. At the reaction temperature of 800 °C, the conversions of CH4 and CO2 of the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst are 13% and 15%, respectively. Compared with the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, the initial activity of the catalyst-assisted impregnation is significantly improved. Among them, the conversions of CH4 by the Ni/SBA-15-6 and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts are 60% and 65%, respectively. The conversions of CO2 are 72% and 73%, respectively. This is because the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst has a higher number of active sites, which helps to activate CH4. The Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has the highest conversions of CH4 and CO2. These are 78% and 85%, respectively, and that for H2/CO is 0.93. This is because the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has a smaller Ni particle size, higher dispersion of active components, and more exposed active sites, resulting in a significant increase in initial activity.

Figure 8.

Initial activity of catalysts at different temperatures: (a) CH4 conversion; (b) CO2 conversion; (c) H2/CO.

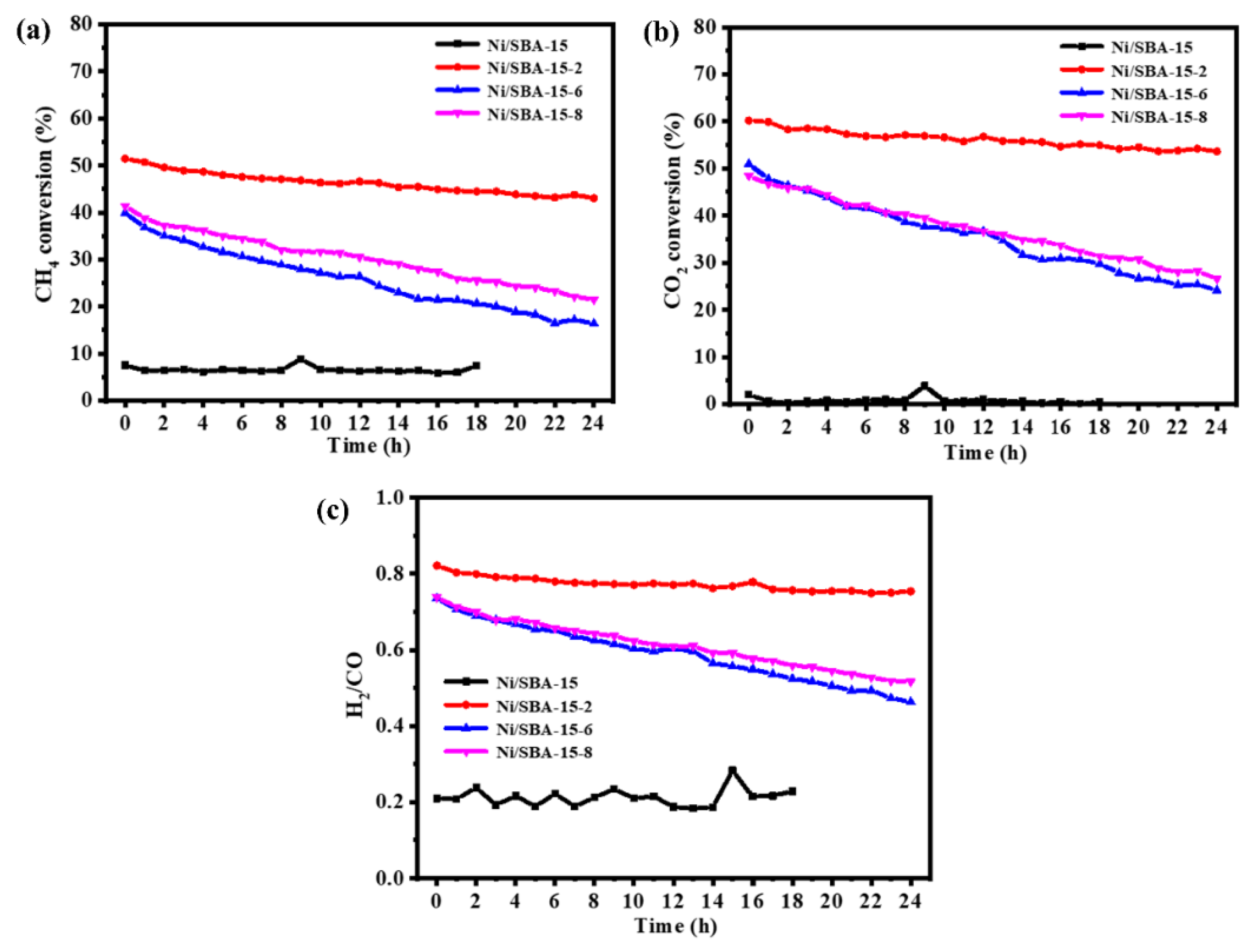

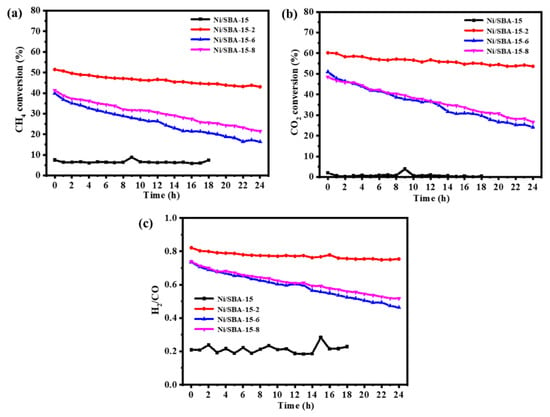

Figure 9 shows the variation in CH4 and CO2 conversions with reaction time for four catalysts under atmospheric pressure, 700 °C, and GHSV = 30,000 mL/(h·gcat). The activity of the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst is the lowest, especially for the conversions of CO2, which is almost close to 0 within 18 h of operation. The conversions of CH4 and CO2 achieved by the catalysts used for assisted impregnation were significantly improved. It can be noted that the stability of the catalysts prepared by changing the pH of the solution is also different. For the Ni/SBA-15-6 catalyst, the conversions of CH4 and CO2 decreased from 40% and 51% to 16% and 24%, respectively, with a decrease of 24% and 27%. For the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst, the conversions of CH4 and CO2 decreased from 41% and 48% to 22% and 27%, respectively, with a decrease of 19% and 21%. This is because the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst increases its adsorption capacity for CO2, so its stability is relatively better than that of the Ni/SBA-15-6 catalyst. However, the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst consistently outperforms other catalysts in terms of both activity and stability. After 24 h of reaction, the conversions of CH4 and CO2 achieved by the catalyst decreased from 51% and 60% to 43% and 54%, respectively. H2/CO is from 0.82 to 0.75. This is because the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst enhances the metal–support interaction, improves the adsorption capacity for CO2, and thus inhibits the sintering of active components and the formation of carbon deposits.

Figure 9.

Catalytic performance of catalysts over 24 h: (a) CH4 conversion; (b) CO2 conversion; (c) H2/CO.

2.6. Characterization of Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst After Reaction

Figure 10 shows the TEM image of the catalyst after the reaction. Through particle size statistical analysis, the Ni particle sizes of the Ni/SBA-15, Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts are 17.7 nm, 6.1 nm, 7.4 nm, and 9.8 nm, respectively. Compared with fresh catalysts, the metal particle size of the catalysts increased after the reaction, indicating a certain degree of Ni particle sintering and agglomeration in the catalysts. Sintering will reduce the metal surface area, thereby reducing catalytic activity [15]. Compared with the Ni/SBA-15-6 catalyst, the Ni/SBA-15-8 catalyst has a smaller increase in particle size, which is also one of the reasons for its slower deactivation rate. In contrast, the particle size of the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst is the smallest and the increase is relatively small, which is also one of the factors that maintains its excellent catalytic activity and stability.

Figure 10.

TEM images and Ni particle size distributions of spent catalysts: (a,e) Ni/SBA-15, (b,f) Ni/SBA-15-2, (c,g) Ni/SBA-15-6, and (d,h) Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts.

The XRD patterns of the catalysts after the reaction are shown in Figure 11. It can be seen that all of the catalysts exhibit Ni diffraction peaks at 44.4°, 51.8°, and 76.3° (JCPDS 87-0712) [21]. However, compared with the reduced catalyst, the line broadening (FWHM) of the catalyst after the reaction increased. This indicates that migration and aggregation of some active components occurred during the DRM reaction. In addition, the intensity of the Ni diffraction peak varies among different catalysts. According to the Scherrer formula, the particle size of the catalyst after the reaction was calculated and listed in Table 1. It is further verified that the increase in the grain size of the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst was the smallest. This is consistent with the results of the TEM.

Figure 11.

XRD spectrum of spent catalysts.

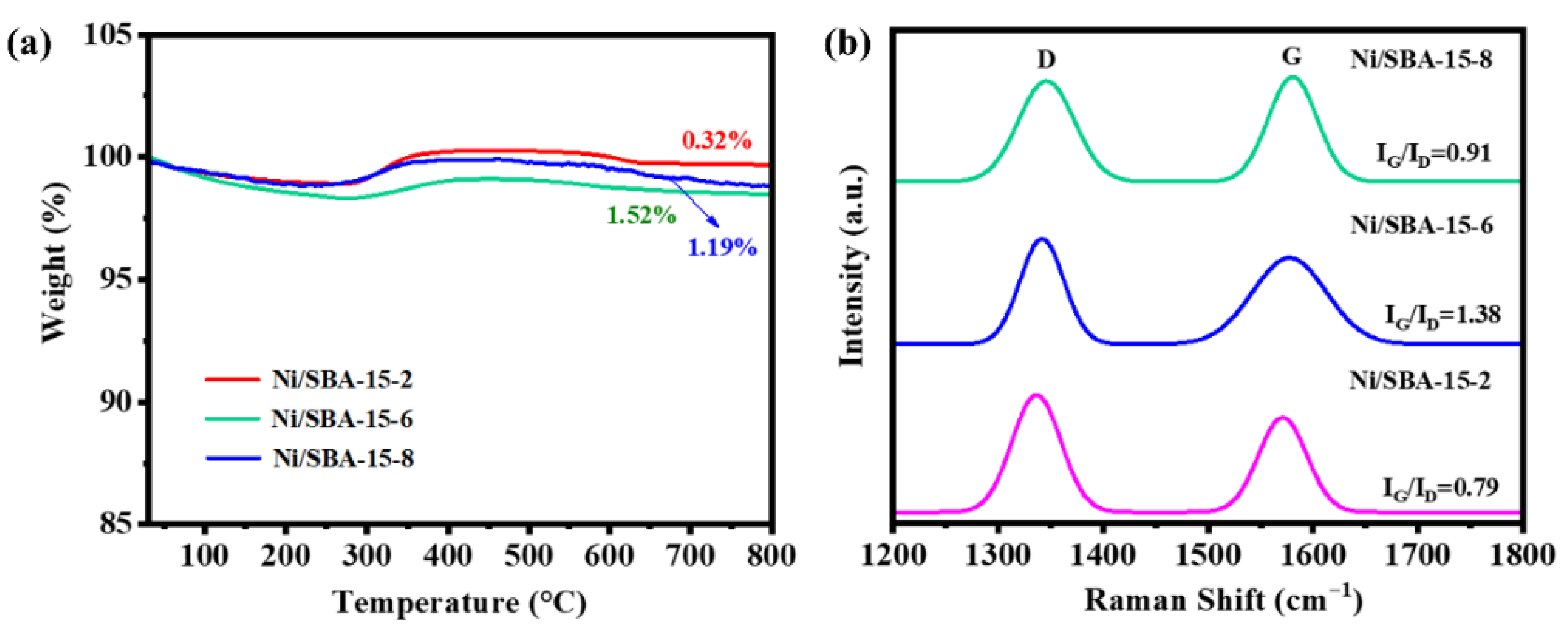

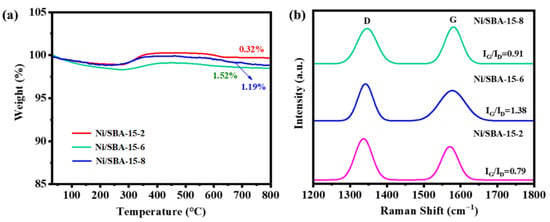

The carbon deposition of the catalyst after the reaction was characterized by TG analysis, and the results are shown in Figure 12a. The weight loss at 30–300 °C can be attributed to the desorption of water and other gases [48]. The oxidation of metal Ni leads to a slight increase in weight at 300–400 °C [49]. The weight loss observed above 400 °C is due to the elimination of carbon on the catalyst’s surface area [50]. The weight loss exhibited by the Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts after the reaction was 0.32%, 1.52%, and 1.19%, respectively. It can be seen that the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst can effectively inhibit the production of carbon deposits. This is because the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has the smallest metal particle size and the greatest ability to adsorb CO2.

Figure 12.

(a) TG curve and (b) Raman spectrum of Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts after reaction.

The carbon deposition properties on the catalyst after the reaction were analyzed by Raman spectroscopy, and the results are shown in Figure 12b. The peaks in the range of 1300~1400 cm−1 and 1500~1650 cm−1 correspond to amorphous carbon (D-band) and graphite carbon (G-band), respectively [38]. The IG/ID ratios of Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8 catalysts after the reaction were 0.79, 1.38, and 0.91, respectively. Compared to other catalysts, the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst has the lowest amount of carbon deposition and degree of carbon graphitization, which is also one of the factors contributing to its higher catalytic activity and stability.

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials

Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and SBA-15 were procured from Aladdin Biochemical Company (Aladdin Biochemical Company, Shanghai, China) and Xianfeng Nano Material Technology Co., Ltd. (Xianfeng Nano Material Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), respectively. High-purity gases, including CH4, CO2, H2 and N2, were provided by Anxuhongyun Co., Ltd. (Anxuhongyun Co., Ltd., Taiyuan, China).

3.2. Catalyst Preparation

The loading of Ni is controlled at 10 wt%. A mass of 0.2753 g of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O is dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water as solution A. According to a molar ratio of 2 between citric acid and Ni, the citric acid is dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water as solution B. The pH of solution B reaches 2, 6, and 8 through addition of ammonia solution, respectively. Solution A is added dropwise to solution B. Then, 0.50 g SBA-15 is added to the above mixture and stirred for 30 min. After the sample is dried, the temperature is raised to 550 °C in a muffle furnace at a rate of 2 °C/min and maintained for 3 h to obtain the desired catalyst. The catalysts are named Ni/SBA-15-2, Ni/SBA-15-6, and Ni/SBA-15-8, respectively.

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

The structural and physicochemical properties of the catalysts were thoroughly characterized using a variety of analytical techniques. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å, 40 kV, 30 mA). The scanning range was set from 10° to 90° at a rate of 5°·min−1. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were recorded on a Quantachrome ASIQC 050200-6 (Boynton Beach, FL, USA) constant volume adsorption instrument. Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis was performed on a NETZSCH STA 449F3 instrument (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany) under an air atmosphere, with the temperature ramped to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C·min−1. Additionally, the graphitization degree of the catalysts was evaluated by Raman spectroscopy (HORIBA Scientific LabRAM, Kyoto, Japan) using a 532 nm laser source, with spectral acquisition in the range of 800–2000 cm−1. The elemental distribution and chemical states on the surface of catalyst were measured by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Scientific K-Alpha, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Al K α (h ν = 1486.6 eV) was used as the laser source. The binding energies of all catalysts were corrected using the C 1s (284.8 eV) peak and peak fitting was performed using AVANTAGE 5 software. TEM testing was conducted using the American FEI Talos F200X transmission electron microscope (American FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) for analysis and characterization. The powdered sample was ultrasonically dispersed in anhydrous ethanol for 10 min. The suspension was dropped onto a carbon film-supported copper mesh, allowed to dry naturally, and subsequently subjected to testing. The quantitative analysis of active metal Ni in catalyst samples was measured by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES, NWR 5110, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) after diluting different solutions to the appropriate detection range. A Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FTIR, Nicolet Nexus iS50, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for surficial analysis. A mass of 1 mg of catalyst powder was mixed with 100 mg KBr for subsequent testing. The resolution was set to 4 cm−1 and the scanning range was 400~4000 cm−1, and the number of scans was 32 during the testing process.

The reducibility and surface adsorption properties of the catalysts were evaluated through temperature-programmed techniques utilizing a thermal conductivity detector (TCD, Quantachrome instrument, Shanghai, China). H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) was performed by heating the samples to 850 °C under a 10% H2/Ar flow at a ramp rate of 10 °C·min−1, with hydrogen consumption monitored by the TCD. Additionally, H2 temperature-programmed desorption (H2-TPD) and CO2 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2-TPD) analyses were performed utilizing the same experimental setup. A mass of 0.1 g of sample was reduced in 30 mL/min 10% H2/Ar at 800 °C for 60 min. Then, it was purged with high-purity Ar at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, adsorption was carried out for 30 min under a 10% H2/Ar or 10% CO2/Ar atmosphere. Then, we switched to Ar purging to remove physically adsorbed H2 or CO2. After the baseline stabilizes, the temperature was increased to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. And TCD is used to detect the signal of H2 or CO2 online.

3.4. Catalytic Reaction Test for DRM

The catalytic performance for DRM reaction was evaluated in a fixed-bed quartz reactor at atmospheric pressure. Prior to each test, the catalyst was reduced in pure H2 at 800 °C for 60 min, followed by purging with N2 to remove residual H2. The reaction was initiated by introducing an equimolar mixture of CH4 and CO2 in a 1:1 volume ratio into the reactor. The compositions of reactants and products were monitored online using a gas chromatograph (GC-A60, Anhui Pannuo Technology Co., Ltd., Hefei, China), which is equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The conversions of CH4 (XCH4) and CO2 (XCO2), as well as the H2/CO ratio, were calculated based on the inlet and outlet volumetric flows (Fin and Fout) of the corresponding components according to the following equations.

XCH4 = (FCH4,in − FCH4,out)/FCH4,in × 100%

XCO2 = (FCO2,in − FCO2,out)/FCO2,in × 100%

H2/CO = FH2,out/FCO,out

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the structure of the Ni/SBA-15 catalyst is regulated by changing the pH value of the impregnation solution, and the catalyst is applied to the DRM reaction. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) The dispersion of the active components of the catalyst is changed after changing the pH value of the impregnation solution. When the pH of the impregnation solution is 2, the dispersion of the active components is the highest and the particle size is the smallest. The second-best in terms of active component dispersion is the catalyst prepared at pH 6. When the pH of the impregnation solution is 8, the dispersion of the active components is the lowest and the particle size is the largest. This is because the interaction force between the active components and the support is different. The greater the proportion of strong interactions, the dispersion of the active components is higher.

(2) The initial activity of the catalyst is related to the number of exposed active sites. Under the same reaction conditions, the initial activity of the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst is significantly better than other catalysts. This is because the catalyst exposes a large number of active sites. At 700 °C and GHSV = 30,000 mL/(h·gcat), the conversions of CH4 and CO2 are 51% and 60%, respectively. The H2/CO ratio is 0.82.

(3) The analysis of the catalysts after the reaction shows that the Ni/SBA-15-2 catalyst exhibits the optimal anti-coking performance. This is due to the strong CO2 adsorption capacity of the catalyst, which helps inhibit the formation of carbon on the catalyst surface, thereby extending the lifespan of the catalyst.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16020130/s1, Figure S1: FTIR spectra of different catalysts; Figure S2: Effect of solution pH on Zeta potential of SBA-15 supports at room temperature; Table S1: CO2 desorption amount of different catalysts; Table S2: The fitting results of XPS spectra.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, S.D.; supervision, visualization, Z.L.; funding acquisition, project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22078226) and the Scientific Research Fund Project of Shanxi Vocational University of Engineering Science and Technology (KJ202536, KJ202533, KJ202515).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22078226). This work is also supported by the Scientific Research Fund Project of Shanxi Vocational University of Engineering Science and Technology (KJ202536, KJ202533, KJ202515).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Peng, B.; Streimikiene, D.; Agnusdei, G.P.; Balezentis, T. Is sustainable energy development ensured in the EU agriculture? Structural shifts and the energy-related greenhouse gas emission intensity. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.-J.; Shim, J.-O.; Kim, H.-M.; Yoo, S.-Y.; Roh, H.-S. A review on dry reforming of methane in aspect of catalytic properties. Catal. Today 2019, 324, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramouni, N.A.K.; Touma, J.G.; Abu Tarboush, B.; Zeaiter, J.; Ahmad, M.N. Catalyst design for dry reforming of methane: Analysis review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2570–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jie, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Al-Megren, H.A.; Alshihri, S.; Edwards, P.P.; Xiao, T. The importance of inner cavity space within Ni@SiO2 nanocapsule catalysts for excellent coking resistance in the high-space-velocity dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 259, 118019. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Z.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Liu, G.; Liang, X. Highly active and stable alumina supported nickel nanoparticle catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 201, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Stagg-Williams, S.M.; Noronha, F.B.; Fendley, G.; Resasco, D.E. CO2 Reforming of CH4 over Pt/ZrO2 Catalysts Promoted with La and Ce Oxides. J. Catal. 2000, 194, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Tardio, J.; Bhargava, S. A comparison study on carbon dioxide reforming of methane over Ni catalysts supported on mesoporous SBA-15, MCM-41, KIT-6 and γ-Al2O3. In Chemeca 2013: Challenging Tomorrow; Engineers Australia: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2013; Volume 17, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, B.; Wang, Z.; Kawi, S. High carbon resistant Ni@Ni phyllosilicate@SiO2 core shell hollow sphere catalysts for low temperature CH4 dry reforming. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 27, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Suh, D.J.; Park, T.-J.; Kim, K.-L. Effect of metal particle size on coking during CO2 reforming of CH4 over Ni-alumina aerogel catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 197, 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; Han, X.; You, X.; Lin, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; et al. Catalysts in Coronas: A surface spatial confinement strategy for high-performance catalysts in methane dry reforming. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9072–9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Park, J.S.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, H. Uncoupling the size and support effects of Ni catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 203, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y. Insight into the role of preparation method on the structure and size effect of Ni/MSS catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 250, 107891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, F.; Guo, X.; Wang, G. Syngas production via steam-CO2 dual reforming of methane over LA-Ni/ZrO2 catalyst prepared by L-arginine ligand-assisted strategy: Enhanced activity and stability. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 3461–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Long, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Song, Z.; Lin, Q. A novel promoting effect of chelating ligand on the dispersion of Ni species over Ni/SBA-15 catalyst for dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 14103–14114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Han, C.; Liu, H.; Gong, D.; Mo, L.; Wei, Q.; Tao, H.; Cui, S.; Wang, L. Glycine-assisted preparation of highly dispersed Ni/SiO2 catalyst for low-temperature dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 32071–32080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, M.; Ra, H.; Yoon, S.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, K. Efficient and stable Ni/SBA-15 catalyst for dry reforming of methane: Effect of citric acid concentration. Catalysts 2023, 13, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueras, F. Basicity, Catalytic and Adsorptive Properties of Hydrotalcites; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Mu, M.; Ding, F.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Song, C. Organic acid-assisted preparation of highly dispersed Co/ZrO2 catalysts with superior activity for CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2019, 254, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.C.; Setiabudi, H.D.; Jalil, A.A. Dendritic fibrous SBA-15 supported nickel (Ni/DFSBA-15): A sustainable catalyst for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 18533–18548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Xin, Z.; Meng, X.; Bian, Z.; Lv, Y. Highly dispersed nickel within mesochannels of SBA-15 for CO methanation with enhanced activity and excellent thermostability. Fuel 2017, 188, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shen, Z.; Chen, G.; Yin, C.; Liu, Y.; Ge, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, X. Carbon-coated mesoporous silica-supported Ni nanocomposite catalyst for efficient hydrogen production via steam reforming of toluene. Fuel 2020, 275, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Quek, X.-Y.; Wah, H.H.A.; Zeng, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over nickel-grafted SBA-15 and MCM-41 catalysts. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Arbag, H.; Yasyerli, N. SBA-15 supported mesoporous Ni and Co catalysts with high coke resistance for dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Bei, K. Promotion effect of different lanthanide doping on Co/Al2O3 catalyst for dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 18644–18656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H. Hydrogen production from steam reforming ethanol over Ni/attapulgite catalysts-Part I: Effect of nickel content. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 192, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Y. Influence of ceria existence form on deactivation behavior of Cu-Ce/SBA-15 catalysts for methanol steam reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y. Ordered mesoporous Ni/Silica-carbon as an efficient and stable catalyst for CO2 reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 4809–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz-Flores, V.G.; Martinez-Hernandez, A.; Gracia-Pinilla, M.A. Deactivation of Ni-SiO2 catalysts that are synthetized via a modified direct synthesis method during the dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 594, 117455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, W.; Yu, Q.; Tang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. Effect of citric acid addition on the morphology and activity of Ni2P supported on mesoporous zeolite ZSM-5 for the hydrogenation of 4,6-DMDBT and phenanthrene. J. Catal. 2017, 345, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Li, Z.-L.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J.-H.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z. Bimetallic Pd-M (M = Pt, Ni, Cu, Co) nanoparticles catalysts with strong electrostatic metal-support interaction for hydrogenation of toluene and benzene. Mol. Catal. 2020, 492, 110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Shi, C.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Peng, C.; Zou, J.-J. Achieving super dispersed metallic nickel nanoparticles over MCM-41 for highly active and stable hydrogenation of olefins and aromatics. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoregbe, O.; Danh, H.T.; Abidin, S.Z.; Setiabudi, H.D.; Abdullah, B.; Vu, K.B.; Vo, D.-V.N. Influence of lanthanide promoters on Ni/SBA-15 catalysts for syngas production by methane dry reforming. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Muratsugu, S.; Ishiguro, N.; Tada, M. Ceria-doped Ni/SBA-16 catalysts for dry reforming of methane. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar]

- van de Loosdrecht, J.; van der Kraan, A.M.; van Dillen, A.J.; Geus, J.W. Metal-support interaction: Titania-supported and silica-supported nickel catalysts. J. Catal. 1997, 170, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, F.; Nie, D.; Qi, L.; Lian, X.; Chen, H.; Wu, M. CO2 methanation over Ca doped ordered mesoporous Ni-Al composite oxide catalysts: The promoting effect of basic modifier. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 21, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Gong, J. A Ni@ZrO2 nanocomposite for ethanol steam reforming: Enhanced stability via strong metal-oxide interaction. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 4226–4228. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, M.; Mihet, M.; Borodi, G.; Lazar, M.D. Combined steam and dry reforming of methane for syngas production from biogas using bimodal pore catalysts. Catal. Today 2021, 366, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Xie, X.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Yuan, L. Dry reforming of methane over Mn-Ni/attapulgite: Effect of Mn content on the active site distribution and catalytic performance. Fuel 2022, 321, 124032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, R.K.; Chong, M.Y.; Osazuwa, O.U.; Nam, W.L.; Phang, X.Y.; Su, M.H.; Cheng, C.K.; Chong, C.T.; Lam, S.S. Production of activated carbon as catalyst support by microwave pyrolysis of palm kernel shell: A comparative study of chemical versus physical activation. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018, 44, 3849–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, S.; Hinrichsen, O. On the interaction of CO2 with Ni-Al catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 580, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, L.; Hu, C.; Da Costa, P. Dry reforming of methane over Ni-ZrOx catalysts doped by manganese: On the effect of the stability of the structure during time on stream. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 617, 118120. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.H.; de Luna, G.S.; Angelucci, S.; Canciani, A.; Jones, W.; Decarolis, D.; Ospitali, F.; Aguado, E.R.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Fornasari, G.; et al. Understanding structure-activity relationships in highly active La promoted Ni catalysts for CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 278, 119256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamdoust, A.; La Parola, V.; Pantaleo, G.; Testa, M.L.; Farjami Shayesteh, S.; Venezia, A.M. Partial oxidation of methane over SiO2 supported Ni and NiCe catalysts. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Ran, R.; Wu, X.; Si, Z.; Weng, D. Dry reforming of methane over Ni catalysts supported on micro- and mesoporous silica. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 68, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Tang, Z.; Hu, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, S. Influence of calcination temperature of Ni/Attapulgite on hydrogen production by steam reforming ethanol. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; Yin, Z.w.; Hu, Z.y.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Li, D. Modification of Al2O3-based catalyst by rare earth elements for steam reforming of methane. AIChE J. 2023, 69, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Lim, K.H.; Gani, T.Z.H.; Aksari, S.; Kawi, S. Bi-functional CeO2 coated NiCo-MgAl core-shell catalyst with high activity and resistance to coke and H2S poisoning in methane dry reforming. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 323, 122141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wan, H.; Du, X.; Yao, B.; Wei, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Yang, H.; Sun, L.; Tao, X.; et al. Highly active Ni/CeO2/SiO2 catalyst for low-temperature CO2 methanation: Synergistic effect of small Ni particles and optimal amount of CeO2. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 236, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; He, D. CO2 reforming of methane to syngas over highly-stable Ni/SBA-15 catalysts prepared by P123-assisted method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Hu, J.; Liang, D.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Comparison of the regenerability of Co/sepiolite and Co/Al2O3 catalysts containing the spinel phase in simulated bio-oil steam reforming. Energy 2021, 214, 118971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.