Abstract

Advanced ceramics are known for their lightweight, high-temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility. They are crucial in energy conversion, environmental protection, and aerospace fields. This review highlights the recent advancements in ceramic matrix composites, high-entropy ceramics, and polymer-derived ceramics, alongside various fabrication techniques such as three-dimensional printing, advanced sintering, and electric-field-assisted joining. Beyond the fabrication process, we emphasize how different processing methods impact microstructure, transport properties, and performance metrics relevant to catalysis. Additive manufacturing routes, such as direct ink writing, digital light processing, and binder jetting, are discussed and normalized based on factors such as relative density, grain size, pore architecture, and shrinkage. Cold and flash sintering methods are also examined, focusing on grain-boundary chemistry, dopant compatibility, and scalability for catalyst supports. Additionally, polymer-derived ceramics (SiOC, SiCN, SiBCN) are reviewed in terms of their catalytic performance in hydrogen evolution reaction, oxygen evolution reaction, oxygen reduction reaction, and CO2 reduction reaction. CeO2-ZrO2 composites are particularly highlighted for their use in environmental catalysis and high-temperature gas sensing. Furthermore, insights on the future industrialization, cross-disciplinary integration, and performance improvements in catalytic applications are provided.

1. Introduction

Advanced ceramics, also referred to as fine ceramics, are high-performance, inorganic, non-metallic materials synthesised through precise control of chemical composition and microstructure. Unlike traditional ceramics, advanced ceramics leverage advanced fabrication technologies. Compared to metals and polymers, advanced ceramics offer distinct advantages, including low density (typically one-quarter to one-third that of Ni-based superalloys), high-temperature resistance (withstanding extreme environments above 2000 °C), high hardness (with Vickers hardness ranging from 15–30 GPa), and excellent chemical stability. These properties make them ideal for fulfilling the demanding requirements of environment-adaptable materials employed in aerospace, electronic information, and biomedical applications [1,2].

In recent years, global technological competition has driven advancements in high-end equipment manufacturing, pushing for higher temperatures, greater efficiency, higher precision, and greener processes. For instance, improving the thrust-to-weight ratio in aeroengines requires hot-section materials that can withstand thermal conditions exceeding 1600 °C. Additionally, the miniaturization of microelectronic devices demands ceramic substrates that offer both high thermal conductivity and low dielectric loss. Meanwhile, the demand for personalized bone implants in medicine has spurred the development of bioceramics with “integrated structure–function” designs [3]. These emerging demands not only raise performance thresholds but also accelerate material innovation.

Against this backdrop, “high-quality development” has emerged as an important objective and overarching trend in the field of advanced ceramics. High-quality development emphasizes not only low carbon footprint, green sustainability, and cost-effectiveness, but also high performance, intelligence, and multifunctional integration. This concept reflects modern materials science’s pursuit of environmental friendliness and resource efficiency, while requiring finer structural and property control. For advanced ceramics, high-quality development is mainly reflected in three aspects: emerging fabrication processes (e.g., additive manufacturing (AM), spark plasma sintering (SPS), cold sintering), advanced material systems (high-entropy and polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs)), and broadened application scenarios. These ceramics now move beyond structural roles in extreme environments to show strong potential in energy-storage devices and energy/environmental catalysis.

2. Research Methodology

This review is based on a systematic literature survey conducted using major scientific databases, including Web of Science (Core Collection), Scopus, and ScienceDirect, which cover peer-reviewed journals in ceramics, materials science, and catalysis. The search primarily focused on publications from the past 10–15 years, with selected earlier seminal works included to provide essential background. Relevant articles were identified using combinations of keywords such as advanced ceramics, polymer-derived ceramics, high-entropy ceramics, additive manufacturing, sintering technologies, electrocatalysis, environmental catalysis, HER, OER, and CO2 reduction.

Articles were selected based on their scientific relevance and direct connection to catalytic applications. Priority was given to studies that explicitly link ceramic composition, fabrication processes, microstructural features, and catalytic performance. Particular attention was paid to works addressing high-quality development aspects, including energy-efficient and green fabrication routes, scalability, multifunctionality, and long-term catalytic stability. Only peer-reviewed English-language articles were considered, ensuring the reliability and consistency of the reviewed literature.

3. The Evolution of Advanced Ceramic Material Systems and Their Development Pathways for Catalytic Applications

Advanced ceramic materials have increasingly transitioned from passive structural or inert support roles toward active, system-enabling components in heterogeneous catalysis, driven by their unique electronic structures, defect chemistry, and architectural design freedom. This is fundamentally different from conventional ceramic systems such as γ-Al2O3 or SiO2. Advanced ceramic systems—including SiCN/SiOC, Mo2C/WC, TiN/VN, CeO2–ZrO2, and polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs)—offer intrinsic catalytic activity, superior thermal and chemical stability, and the ability to integrate active sites with load-bearing, conductive, or mass-transport-optimized frameworks. These attributes enable operation under harsh conditions (high temperature, redox cycling, corrosive environments) where traditional oxide supports suffer from sintering, phase instability, or loss of functionality. Importantly, the value proposition of advanced ceramic catalysts does not lie solely in enhanced activity, but in their capacity to deliver system-level advantages—such as reactor miniaturization, structural–functional integration, and long-term durability—that can justify increased material and processing complexity. In this context, advanced ceramics should be evaluated not as drop-in replacements for established supports, but as enabling platforms for next-generation catalytic reactors. The following sections therefore examine (i) the intrinsic catalytic advantages of representative ceramic material systems, (ii) their true performance and design advantages relative to industrial benchmark supports, and (iii) a forward-looking perspective on how ceramic catalysis may evolve toward scalable, manufacturable, and application-specific platforms.

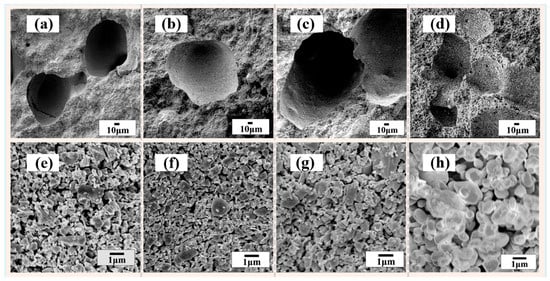

Silicate ceramics, such as cordierite- and mullite-based materials [1], have long served as conventional substrates in industrial catalysts [2], particularly as honeycomb monoliths for automotive exhaust treatment and high-temperature gas-phase reactions. Their widespread adoption is primarily attributed to low cost, excellent thermal stability [1,3], and well-established manufacturing routes, rather than intrinsic catalytic functionality. Figure 1 shows SEM micrographs of the sintered ceramic samples obtained at different sintering temperatures (1350–1650 °C). With increasing sintering temperature, significant changes in grain morphology, grain boundary clarity, and densification behavior can be observed. However, the electronic structure and chemical composition of silicate ceramics are largely inert, offering limited opportunities for active-site engineering or electronic modulation. As a result, their role in catalytic systems is typically confined to mechanical support and thermal management, motivating the development of advanced ceramic materials that integrate catalytic activity, transport functionality, and structural robustness within a single platform.

Figure 1.

Cross-section SEM micrographs of the porous SiC ceramics sintered at different sintering temperatures: (a,e) 1350 °C, (b,f) 1450 °C, (c,g) 1550 °C, and (d,h) 1650 °C.

3.1. Catalysis-Driven Design Principles of Advanced Ceramic Systems

In catalytic environments, the functional requirements imposed on ceramic materials extend far beyond mechanical support and thermal stability. Modern catalytic systems increasingly demand supports and frameworks that actively participate in charge transport, defect-mediated adsorption, and reaction–transport coupling, particularly in electrocatalysis, high-temperature reforming, and structured-reactor configurations. Conventional oxide supports such as γ-Al2O3 and SiO2, while cost-effective and scalable, are fundamentally limited by their electronic insulation, restricted defect tunability, and susceptibility to sintering or deactivation under harsh redox conditions.

Advanced ceramic systems address these limitations through a combination of intrinsic electronic functionality (e.g., conductive carbides, nitrides, and heteroatom-doped ceramics), expanded chemical stability windows, and architectural design freedom enabled by modern fabrication routes. Crucially, their value proposition does not rely solely on higher intrinsic catalytic activity, but on system-level advantages—including integrated electron/heat transport, resistance to structural degradation, and compatibility with monolithic or lattice-based reactor designs. Within this framework, advanced ceramics should be viewed not as drop-in replacements for traditional supports, but as enabling platforms whose added material and processing complexity are justified only when they unlock performance regimes inaccessible to conventional ceramic substrates. In light of the above discussion, the subsequent sections systematically examine different classes of advanced ceramic materials, including SiCN/SiOC, Mo2C/WC, TiN/VN, CeO2–ZrO2, and polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs), with a focus on their catalytic roles, structure–function relationships, and practical advantages over conventional supports.

3.2. Nitride Ceramic Catalysts (TiN/VN) for Catalytic Applications

With the rapid advancement of modern science, technology, and industry, increasingly stringent demands have been imposed on material performance. Under extreme conditions involving high temperature, corrosive environments, severe wear, and high mechanical stress, conventional metals and polymers often fail to meet long-term service requirements. Advanced structural ceramics, owing to their outstanding mechanical strength, thermal stability, and chemical resistance, have therefore become indispensable in aerospace, energy, and high-end manufacturing applications. Among these materials, carbide ceramics occupy a prominent position due to the strong covalent bonding between carbon and metal or metalloid atoms, which imparts high hardness, excellent wear resistance, and exceptional thermal stability [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

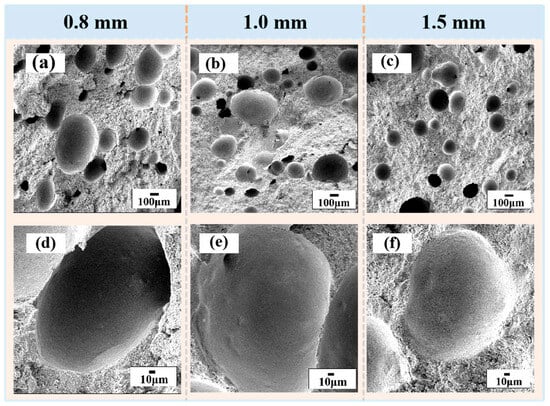

While carbide ceramics have been widely employed as cutting tools, thermal protection components, and electronic substrates, their broader application potential has historically been constrained by intrinsic brittleness, limited sinterability, and oxidation sensitivity under certain conditions. To address these challenges, extensive efforts have focused on compositional optimization, microstructural tailoring, and advanced densification techniques, enabling improved toughness, oxidation resistance, and overall reliability. In parallel, additive manufacturing (AM) of carbide ceramics has emerged as an enabling strategy for fabricating complex architectures, although high melting points and residual porosity remain persistent challenges. To date, most AM progress has been achieved in SiC- and B4C-based systems, where complex geometries can be realized while densification and dimensional stability continue to be actively optimized [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Figure 2 presents SEM images of the ceramic samples with different thicknesses (0.8, 1.0, and 1.5 mm). The low-magnification images (a–c) reveal the overall pore distribution, while the high-magnification images (d–f) provide detailed views of individual spherical pores.

Figure 2.

SEM images of ceramic samples with different thicknesses: (a,d) 0.8 mm; (b,e) 1.0 mm; (c,f) 1.5 mm. Panels (a–c) show low-magnification views of the overall pore distribution, while panels (d–f) present high-magnification images of representative spherical pores [7].

Beyond their traditional structural roles, advanced carbide and nitride ceramics have demonstrated increasing relevance in energy conversion catalysis, particularly for reactions such as water electrolysis (HER/OER), CO2 electroreduction (CO2RR), and ammonia synthesis and decomposition. These processes impose stringent requirements on catalytic activity, electronic conductivity, and long-term chemical stability. Although noble-metal catalysts such as Pt and RuO2 exhibit excellent intrinsic activity, their high cost and limited durability hinder large-scale deployment. In this context, carbide ceramics such as Mo2C and WC have emerged as promising alternatives owing to their metal-like d-band electronic structures, which afford favorable adsorption energetics for key reaction intermediates and enable low overpotentials, small Tafel slopes, and robust durability in both acidic and alkaline environments [12,13].

Similarly, conductive nitride ceramics, including TiN and VN, offer distinct advantages arising from their high electrical conductivity and nitrogen-vacancy–mediated surface chemistry. These features promote efficient charge transfer and facilitate the adsorption and dissociation of hydrogen- and oxygen-containing species, rendering such materials attractive as catalysts or catalyst supports for energy-related reactions [14,15,16]. In contrast, wide-bandgap nitrides such as AlN and Si3N4 primarily serve as thermally conductive, electrically insulating, and microwave-compatible ceramic platforms, where their excellent thermal management capability, dielectric stability, and corrosion resistance are critical for high-temperature catalytic environments and reactor integration [17,18,19].

Recent advances in additive manufacturing of nitride ceramics, including photopolymerization-based approaches for Si3N4 and extrusion-based shaping routes for AlN, have enabled the fabrication of architected ceramic components with integrated flow and thermal-management features. Although challenges related to densification, grain growth, and defect control persist, continued progress in precursor formulation and sintering strategies is expected to further expand the applicability of carbide- and nitride-based ceramics in structured catalytic reactors and multifunctional energy devices [20,21].

3.3. Polymer-Derived Ceramics (PDCs) for Catalytic Applications

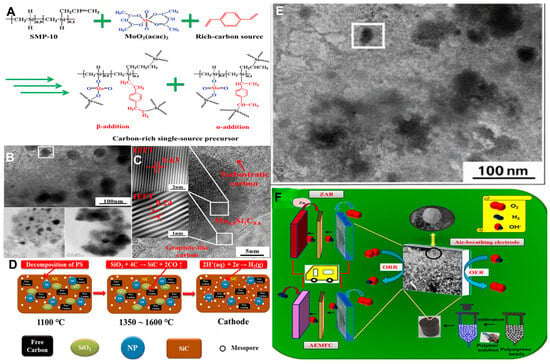

Polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs) provide a versatile platform for catalytic materials design by enabling a composition–structure–function paradigm that couples amorphous ceramic networks with conductive, heteroatom-doped carbon phases through molecular-level precursor engineering and controlled pyrolysis. In free-carbon–rich SiOC systems, percolated sp2 carbon domains offer corrosion-resistant electrical pathways and high accessible surface area, allowing these materials to serve as robust conductive supports for electrocatalytic reactions (e.g., HER/OER) while simultaneously suppressing filamentous carbon formation during high-temperature reforming via stabilized Si–O–C matrices; surface functionalization further improves metal anchoring and dispersion [22]. Figure 3 summarizes the structural characteristics and catalytic mechanism of the carbon-rich single-source–derived material. As shown in Figure 3A, a carbon-rich single-source precursor is formed by combining SMP-10, MoO2(acac)2, and a carbon-rich component, providing a suitable molecular platform for the generation of carbon-based catalysts. TEM images (Figure 3B) indicate that the active components are uniformly dispersed in the carbon matrix. HRTEM analysis (Figure 3C) reveals turbostratic carbon with short-range graphitic ordering, which is beneficial for electron transport and the creation of defect sites. The structural evolution during thermal treatment is illustrated in Figure 3D, leading to the formation of a porous carbon framework, as confirmed by SEM images in Figure 3E. Based on these structural features, the corresponding working principle of the air electrode is shown in Figure 3F.

Figure 3.

Structure and catalytic mechanism of the carbon-rich single-source–derived catalyst, (A) Formation of the carbon-rich single-source precursor. (B) TEM image showing uniform dispersion of active components. (C) HRTEM images revealing turbostratic carbon with locally ordered graphitic domains. (D) Schematic of structural evolution during high-temperature treatment. (E) SEM images of the porous carbon framework. (F) Working principle of the air-breathing electrode.

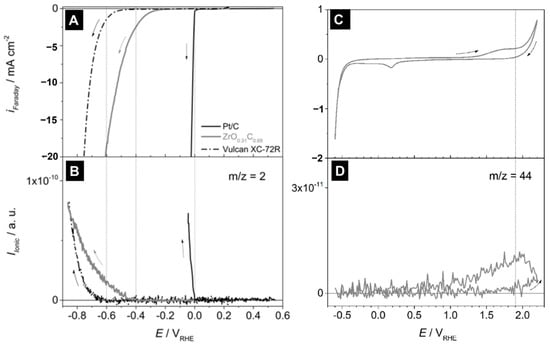

Nitrogen incorporation in SiCN tailors the electronic structure of the embedded carbon phase, where pyridinic and graphitic N species enhance charge transport and adsorption energetics, enabling metal-free or synergistic catalytic pathways in ORR and CO2 reduction, as well as improved interfacial electron transfer when functioning as catalyst supports [23]. Co-doping with boron and nitrogen in SiBCN preserves conductive networks under elevated temperatures and oxidative environments, imparting enhanced resistance to sintering and carbon over-oxidation, which is particularly advantageous for high-temperature catalytic processes and electrothermal reactor configurations [24]. Beyond compositional tuning, ultralight PDC-derived architectures such as ZrOC foams and lattices demonstrate how structural design can address system-level constraints in flow reactors, where low density, thermal-shock tolerance, and mechanical integrity enable rapid temperature modulation and reduced pressure drop while remaining compatible with conventional washcoating or infiltration strategies [25]. As shown by Shakibi Nia et al., Figure 4 combines electrochemical measurements with in situ mass spectrometry to evaluate the HER behavior of ZrO0.31C0.69. The material exhibits a clear cathodic response associated with hydrogen evolution, while MS signals at m/z = 2 confirm H2 formation in the same potential range. Cyclic voltammetry and the corresponding m/z = 44 response indicate that carbon-related oxidation is minimal under HER-relevant conditions, demonstrating that ZrO0.31C0.69 functions as an active and stable HER catalyst in acidic media. Beyond catalytic activity, the results highlight that rational structural modulation offers a viable strategy to mitigate system-level limitations in fluid reactor configurations.

Figure 4.

(A) Electrochemical and mass spectrometric analysis of ZrO0.31C0.69 during HER. (A) LSVs of Pt/C, ZrO0.31C0.69, and Vulcan XC-72R in 0.5 M H2SO4. (B) Corresponding MS-LSVs for H2 evolution (m/z = 2). (C) CV of ZrO0.31C0.69. (D) Corresponding MS-CV for CO2 evolution (m/z = 44). Scan rates: 5 mV·s−1 (LSV) and 10 mV·s−1 (CV). Dotted lines indicate onset potentials [25].

Polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs) are synthesized through the high-temperature pyrolytic conversion of preceramic polymers (PCPs), whose molecular backbones typically contain elements such as Si, O, C, N, and B, giving rise to representative systems including SiOC, SiCN, and SiBCN [26]. Unlike conventional powder-based ceramic processing, the PDC route starts from molecularly designable polymer precursors, enabling precise control over ceramic composition and functionality after crosslinking, pyrolysis, and ceramization under controlled atmospheres [27]. The favorable rheological and photochemical properties of many PCPs further allow low-temperature shaping and high-formability prior to ceramization, providing a unique pathway toward complex ceramic architectures [28].

Among various shaping techniques, vat photopolymerization (VP)-based additive manufacturing has emerged as a particularly effective approach for fabricating PDC components with intricate geometries and high dimensional fidelity. The compatibility of PCPs with photocuring processes enables the construction of complex green bodies, which can be subsequently converted into dense or architected ceramics while retaining their designed geometry. Such capabilities are especially relevant for catalytic applications, where structured reactors, hierarchical porosity, and integrated flow channels are essential for optimizing mass transport, heat management, and catalyst utilization [29,30,31,32,33].

Photocurable polysiloxane-derived systems have been extensively explored for the additive manufacturing of SiOC ceramics, with molecular modification of PCPs or incorporation of secondary phases used to regulate ceramic yield, structural integrity, and functional performance after pyrolysis [34,35,36,37,38,39]. While these studies often report enhanced mechanical strength or lightweight characteristics, their broader significance for catalysis lies in demonstrating that complex, thermally stable ceramic architectures can be reliably fabricated and preserved during high-temperature treatment. Recent advances in high-speed VP technologies, including continuous liquid interface production and tomographic stereolithography, further expand the scalability and efficiency of PDC-based manufacturing, facilitating the production of defect-free, high-surface-quality ceramic structures suitable for reactor-scale applications [40,41].

Beyond SiOC systems, additive manufacturing has also enabled the fabrication of functional PDC architectures based on SiCN, SiBCN, SiBOC, and ZrOC. For instance, 3D-printed SiCN ceramic microreactors have demonstrated excellent thermal stability and corrosion resistance during high-temperature ammonia decomposition, enabling efficient and continuous hydrogen generation [31]. The molecular design of polyborosilazane precursors has similarly been employed to fabricate SiBCN ceramics with complex geometries and enhanced high-temperature stability [32], while ultralight ZrOC lattices produced via photocuring routes illustrate the potential of PDC-derived architectures for weight-sensitive and thermally demanding flow-reactor environments [33]. Collectively, these examples highlight that the primary value of PDC processing and additive manufacturing lies not in isolated mechanical performance metrics, but in enabling structurally integrated, thermally robust ceramic platforms tailored for advanced catalytic and chemical reaction systems.

3.4. High-Entropy Oxide Catalysts for Catalytic Applications

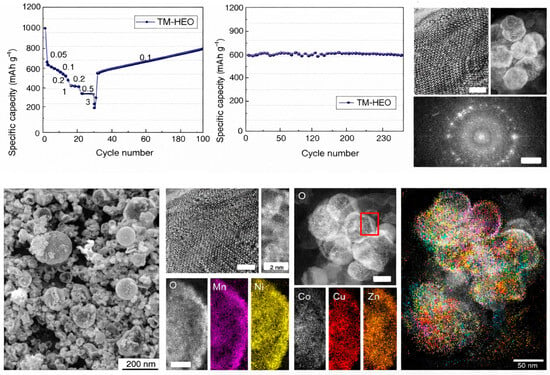

Beyond compositional complexity, the catalytic relevance of high-entropy oxides (HEOs) lies in their ability to generate statistically distributed and dynamically adaptable active-site landscapes. Unlike conventional single- or binary-oxide catalysts, where activity is often governed by a limited number of well-defined surface motifs, HEOs intrinsically host a broad spectrum of local cation coordination environments and electronic states. This ensemble effect leads to a continuous distribution of adsorption energies for key reaction intermediates, increasing the likelihood that a subset of surface sites remains catalytically optimal under varying electrochemical potentials and reaction conditions. In addition, owing to their multicomponent compositions and complex electronic band structures, high-entropy oxides generate a diverse population of catalytically relevant surface sites, underpinning their promise in electrocatalytic energy conversion. Figure 5 summarizes the electrochemical performance and microstructural characteristics of TM-HEO. The material exhibits stable capacity during long-term cycling and good rate capability. Electron microscopy and elemental mapping further reveal a structurally stable framework with homogeneous multi-metal distribution, which is favorable for the observed electrochemical behavior [42].

Figure 5.

Electrochemical performance, structural characterization, and mechanism of TM-HEO [42].

Importantly, configurational entropy in HEOs does not necessarily translate into higher intrinsic activity at individual sites; rather, it enhances catalytic robustness by suppressing phase segregation, surface reconstruction, and cation dissolution during prolonged electrochemical operation. Such entropy-stabilized active-site landscapes are particularly advantageous for demanding electrocatalytic reactions, including oxygen evolution and reduction under alkaline conditions, where catalyst degradation and activity decay often limit practical performance.

3.5. CeO2–ZrO2 Ceramic Catalysts for Catalytic Applications

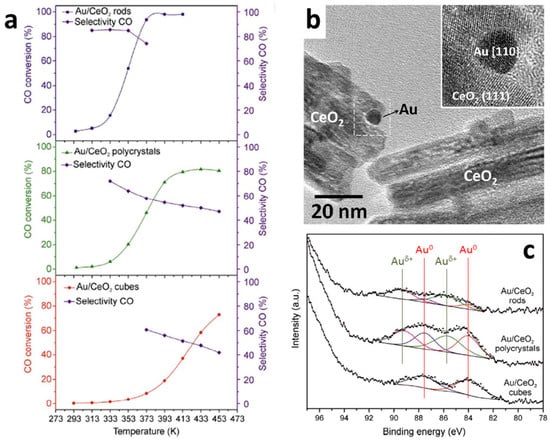

CeO2–ZrO2 (CZO) composite oxides are cornerstone materials in environmental catalysis due to their high oxygen storage/release capacity (OSC) and enhanced thermal stability compared with pure ceria, enabling sustained redox performance under the cyclic operating conditions of three-way catalytic (TWC) converters. By stabilizing the fluorite structure and promoting reversible Ce4+/Ce3+ redox transitions, CZO materials maintain efficient NOx, CO, and hydrocarbon conversion while exhibiting strong resistance to sintering and catalyst poisoning during high-temperature operation [43]. Figure 6 illustrates a representative structure–activity relationship in Au/CeO2 catalysts for the CO preferential oxidation (COPrOx) reaction. Beyond automotive exhaust purification, the same OSC-driven oxygen vacancy chemistry allows CZO to function as high-temperature gas-sensing materials for species such as NOx and CO, where rapid oxygen exchange underpins fast response and recovery.

Figure 6.

(a) CO preferential oxidation (COPrOx) performance of Au/CeO2 catalysts with different ceria morphologies. (b) HRTEM image of Au/CeO2 nanorods. (c) Au 4f XPS spectra of Au/CeO2 catalysts The red line represents metallic gold (Au0), while the green line represents cationic gold (Au⁺) [42].

From a materials design perspective, the environmental catalytic performance of CZO can be systematically tailored through compositional and structural parameters, including the Ce/Zr ratio (governing fluorite phase stability), aliovalent dopants such as Pr or La (modulating oxygen vacancy concentration), and morphology control (e.g., nanorods or nanocubes) that selectively expose reactive crystal facets. Importantly, recent advances in ceramic processing have enabled the integration of CZO active phases with porous ceramic substrates and additively manufactured (AM) lattice architectures, thereby addressing system-level constraints in environmental catalysis. Such structured ceramic supports enhance mass transport, thermal management, and mechanical durability, while simultaneously improving tolerance to sulfur or hydrothermal poisoning by mitigating local hot spots and diffusion limitations.

In parallel, TiO2-based photocatalytic ceramics represent a complementary class of environmental catalysts for volatile organic compound (VOC) degradation and water pollutant remediation, where photo-induced electron–hole pairs drive oxidative mineralization reactions [44]. Through crystal facet engineering, heterojunction construction, or elemental doping (e.g., N, C, or transition metals), the optical response of TiO2 can be extended into the visible-light region, enabling photocatalytic CO2 reduction and pollutant decomposition under solar irradiation [45]. Together, these examples illustrate how advanced ceramic catalysts—particularly when integrated into porous or architected ceramic frameworks—can couple intrinsic redox or photoactivity with structural functionality to meet the durability, efficiency, and scalability demands of environmental remediation technologies.

3.6. Composite Ceramic Catalysts for Multifunctional Catalytic Applications

Composite ceramic systems offer a versatile platform for catalytic applications by integrating multiple functional components within a single, architecturally stable framework. In contrast to monolithic ceramics, composite designs enable the deliberate combination of catalytically active phases with mechanically and thermally robust ceramic matrices, allowing activity, stability, and transport properties to be optimized independently yet operate synergistically. For example, the incorporation of conductive carbon, carbide, or nitride phases into oxide or polymer-derived ceramic matrices facilitates efficient electron transport while maintaining resistance to sintering and chemical degradation under harsh reaction conditions. Beyond phase composition, composite ceramics also enable multiscale structural integration, where macro- and mesoporous architectures enhance mass and heat transfer, while nanoscale interfaces act as stabilized catalytic sites. Such multifunctional composite strategies are particularly advantageous for high-temperature, electrochemical, and structured-reactor catalysis, where conventional single-phase supports struggle to simultaneously satisfy catalytic, transport, and durability requirements. Representative composite ceramic design strategies and their functional roles in catalysis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative composite ceramic architectures for multifunctional catalytic applications.

3.7. Processing–Structure–Performance Relationships in Advanced Ceramic Catalysis

Advanced ceramic systems offer an unprecedented degree of control spanning molecular composition, microstructural evolution, and catalytic functionality. By systematically tuning processing levers such as precursor chemistry, crosslinking strategy, pyrolysis conditions, and post-treatment protocols, it becomes possible to deliberately steer microstructural attributes, including phase composition, porosity hierarchy, conductive network formation, and surface defect density. These microstructural features, in turn, directly govern key catalytic metrics such as activity, selectivity, stability, and resistance to deactivation under harsh operating conditions.

To consolidate these relationships, an indicative mapping is presented to connect representative processing parameters with resulting microstructural characteristics and catalytic performance descriptors. Rather than prescribing fixed recipes, this framework serves as a design-oriented guide, highlighting how targeted adjustments at the processing stage can be leveraged to achieve application-specific catalytic functionalities across advanced ceramic systems.

Linking fabrication to catalytic metrics clarifies how additive and field-assisted routes tune transport and activity. Table 2 summarizes representative couplings usable for electrolyzers, CO2RR, and reforming reactors. Table 3 describes the comparative information on the microstructure, properties, and catalytic applications of ceramic additive manufacturing (AM) and related processes.

Table 2.

Comparison table of composition, typical features, and catalytic roles/examples for different ceramic-based materials.

Table 3.

Comparison table of microstructure, property, and catalytic application for ceramic am and related processes.

4. Innovations in Advanced Ceramic Fabrication Technologies and Key Enabling Drivers

In recent years, ceramic fabrication technologies have achieved a series of breakthrough advancements. From traditional techniques such as sintering, tape casting, and CVD, to emerging approaches including AM, SPS, and high-entropy ceramic design, multiple processing routes have complemented and gradually integrated with one another, collectively driving ceramics toward microstructural controllability, performance tailorability, near-net shaping, and green low-carbon development. In particular, under the demanding application scenarios of hypersonic vehicle thermal protection systems, nuclear reactor core materials, and next-generation semiconductor devices, the increasing requirements for ceramics in terms of high-temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, and mechanical performance have further spurred continuous innovation and in-depth development of fabrication processes.

4.1. Advanced Ceramic Fabrication Technologies

The current fabrication technologies used for advanced ceramics have far surpassed traditional methods, achieving significant progress in precision control, multi-material composites, structural design, and rapid forming. The performance of ceramics largely depends on the characteristics of the raw powders. High-performance ceramic powders typically require high purity, precisely controlled composition, regular particle morphology, narrow particle size distribution, and low agglomeration. Although the traditional solid-state reaction method has the advantages of simplicity and low cost, it often introduces impurities and results in coarse particles and inhomogeneous compositional distribution. Therefore, it is unsuitable for high-end applications. Consequently, in recent years, a series of advanced powder-preparation techniques have emerged, which can precisely control the composition, structure, and morphology at the atomic or molecular scale.

Wet-chemical approaches, such as co-precipitation, sol–gel, hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis, as well as precursor-based techniques like the Pechini process and combustion synthesis, have shown distinct advantages in producing multicomponent, nanoscale, and highly homogeneous ceramic powders, thus attracting widespread attention. In addition, methods such as self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS), freeze-drying, and spray pyrolysis have been applied in specific systems owing to their efficiency and energy-saving features. These techniques achieve molecular-level mixing of components through liquid-phase or gas-phase reactions, significantly enhancing the sintering activity of powders and laying a solid foundation for the development of high-performance ceramic materials [64].

Advanced Powder Preparation Technologies

Traditional powder preparation methods constitute the technological foundation of advanced ceramic material systems. Their primary objective is to convert raw materials into ceramic powders with controlled chemical composition, particle size, morphology, and sintering activity through well-established physical and chemical processes. Owing to their high maturity and reliability, these methods remain the dominant routes for industrial-scale ceramic powder production.

The performance of high-performance ceramics is strongly governed by precursor powder quality, which requires high purity, compositional homogeneity, narrow particle-size distribution, and minimal agglomeration. Accordingly, conventional techniques—including mechanical milling, solid-state reactions, liquid-phase mixing and precipitation, and high-temperature decomposition—are widely employed to produce oxide and non-oxide ceramic powders at scale. Although these approaches may be limited in achieving nanoscale control or extreme homogeneity, their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and broad equipment availability ensure their continued prevalence in both structural and functional ceramic applications.

Co-precipitation involves mixing metal salt solutions and adjusting the pH to induce the simultaneous precipitation of target components, yielding a compositionally homogeneous precursor. After washing and drying, the precipitate is converted into oxide ceramic powders through calcination. Freeze-drying is often used as an auxiliary dehydration step, in which atomized salt solutions are rapidly frozen and subsequently dehydrated by vacuum sublimation. This process suppresses compositional segregation and particle agglomeration associated with conventional liquid-phase drying, producing loose, porous precursors that can be transformed into fine-grained and chemically homogeneous oxide powders upon thermal treatment [65].

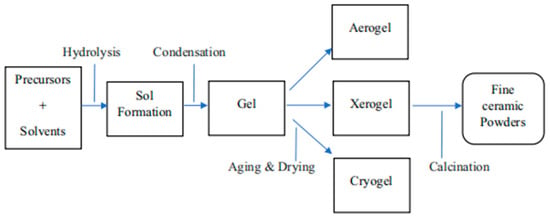

Using metal alkoxides or metal–organic compounds as precursors, stable sol dispersions with particle sizes typically smaller than 0.1 μm can be prepared. Upon solvent evaporation, these dispersions transform into gel-like substances, and initiators may be added when necessary to promote gel formation [66,67]. After dehydration and calcination, the gel can be transformed into fine ceramic powders, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Sol–gel technology for manufacturing fine ceramic powders [68].

Combustion synthesis, often referred to as the glycine–nitrate method, is an evolution of the Pechini process based on exothermic reactions between glycine and metal nitrates. Glycine functions both as a complexing agent and as a fuel, and upon solvent evaporation, the system undergoes spontaneous ignition at ~200 °C, reaching transient temperatures above 1000 °C to rapidly produce fine and compositionally homogeneous oxide powders [69,70]. Similarly, self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) relies on highly exothermic reactions between reactive metals and elements such as C, B, N, or Si to directly form ceramic compounds, including carbides, borides, nitrides, and silicides. Once initiated, these reactions propagate rapidly through the precursor, enabling highly efficient ceramic synthesis.

4.2. Forming and Structural Control Technologies

4.2.1. Tape Casting

Tape casting, also known as the doctor blade method, is widely used for fabricating thin ceramic layers, multilayer structures, and integrated circuit substrates. In this process, a ceramic slurry containing solvents and additives is uniformly deposited onto a smooth moving substrate, with the tape thickness precisely controlled by a blade. Subsequent solvent evaporation yields a continuous green tape that can be wound, stored, and further processed.

Beyond conventional doctor blade casting, alternative approaches such as paper-based tape casting and waterfall casting have been developed. In paper-based methods, ceramic slurry is impregnated into continuous paper substrates, whereas waterfall casting relies on a circulating conveyor belt to form uniform thin layers. During sintering, organic substrates are removed, leaving free-standing ceramic tapes suitable for multilayer assembly [71,72].

4.2.2. Injection Molding

Injection molding employs a rotating screw to feed a ceramic–thermoplastic mixture into a heated chamber, where the mixture softens under high temperature. Under continuous extrusion by the screw, the material is forced into a mold cavity, and upon cooling, the desired structure is obtained. This method enables mass production of components with complex geometries, though the primary cost lies in mold fabrication [73]. To enhance the overall performance of composites, advanced ceramic fibers and particles are often incorporated, especially in ultra-high-temperature composites where they are widely applied [74]. Ceramic fibers are typically prepared via CVD or spinning techniques; for instance, SiC fibers can be obtained by depositing silicon-containing gases onto heated tungsten or carbon filaments, while alumina fibers are commonly produced using a spinning method [75,76]. With their excellent high-temperature resistance, ceramic fibers can operate reliably under severe thermomechanical loads.

Extrusion and injection molding require stringent process control, often necessitating prolonged thermal or microwave drying of ceramic feedstocks, while additive manufacturing and 3D printing are emerging as complementary routes for producing complex ceramic architectures [77].

4.2.3. AM Technologies

DIW is a typical slurry-based AM technique. Relying on a computer-controlled translation stage, it enables the layer-by-layer deposition of materials through the movement of a dispensing nozzle or laser writing system, thereby rapidly constructing predesigned structures and compositions [78]. This process eliminates the need for expensive molds or photolithographic masks and allows flexible fabrication of complex geometries and locally self-supporting structures [79,80,81,82]. According to different forming modes, DIW can be categorized into droplet-based methods (e.g., 3D printing [83], direct inkjet printing [84], and hot-melt printing [85,86]) and filament-based methods (e.g., robotic casting [87], fused deposition [88], and micro-pen writing [89]). Representative studies on ink design strategies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ink designs for the selected DIW technologies.

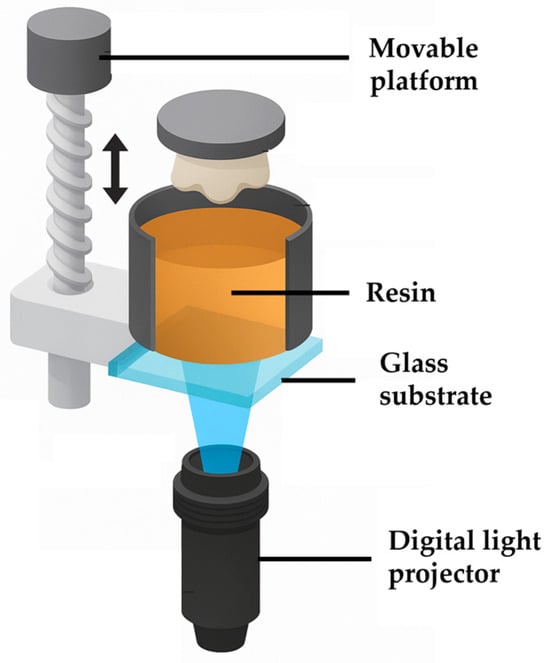

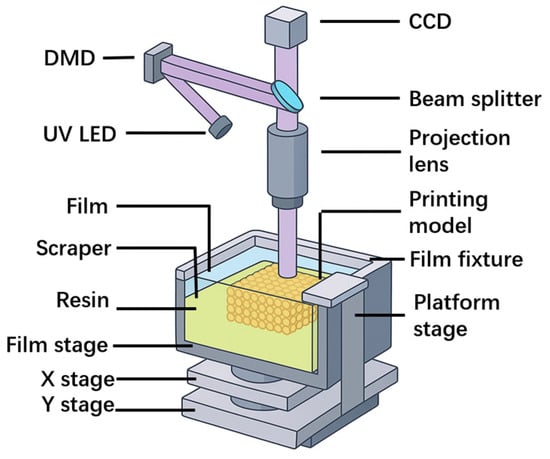

DLP/SLA:DLP employs a digital light projector, rather than a laser, to project an entire layer pattern onto a photosensitive resin [90]. Each cross-section of the object is selectively cured within a thin resin layer, and then the build platform moves upward along the Z-axis by one layer. This process is carried out from bottom to top, including the projection and curing of each successive layer until the entire object is formed. In recent years, DLP has also been referred to as projection PμSL [91].

Projectors equipped with digital micromirror devices (DMDs) precisely control thousands of micromirrors to expose high-resolution cross-sectional patterns as dynamic masks, thereby exposing and curing an entire layer simultaneously without scanning operations [92]. Consequently, compared with SLA, DLP offers not only higher accuracy but also faster forming speed [93]. However, the printing size of DLP is constrained by the resolution of the projector, and large-area exposure may result in undesirable resin shrinkage, which negatively affects printing accuracy [94].

Nevertheless, DLP has been widely applied in the manufacturing of small and complex ceramic components, especially for PDCs with intricate architectures. This is due to its cost-effectiveness, rapid forming capability, and high-resolution printing performance.

DLP is a photopolymerization-based forming technology similar to SLA (Figure 8). Its core distinction lies in the use of DMDs to project ultraviolet light onto the resin surface, enabling selective curing of cross-sections through dynamic masks [95]. Compared with the point-by-point scanning of SLA, DLP cures each layer via whole-layer projection, thereby significantly reducing printing time and alleviating requirements for high-viscosity slurries. Owing to the capability of DMDs to achieve micrometer-scale surface exposure, DLP surpasses SLA in forming accuracy.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of digital optical processing [96].

Bertsch et al. were the first to employ an LCD as a dynamic mask generator, successfully realizing the printing of millimeter-scale samples [97]. Since 2001, LCDs have gradually replaced digital multimedia projectors, markedly improving resolution and contrast. In 2015, Tumbleston et al. proposed the CLIP technique, which continuously separates the resin from the release film, effectively avoiding the staircase effect and improving the anisotropic mechanical properties of printed parts [98]. However, challenges remain in filling high-viscosity slurries, and heat accumulation during resin curing may compromise forming precision.

In 2019, Kelly et al. introduced computed axial lithography (CAL), which decomposes a 3D object into two-dimensional images projected by DLP, with rotation enabling rapid printing. This method is particularly suitable for high-viscosity resins, significantly enhancing printing speed and surface smoothness. Nonetheless, its resolution is limited to the millimeter scale, and the oxygen inhibition mechanism increases the complexity of light-source control [99]. In 2020, Regehly et al. developed xolography, which combines a dual-light processing mechanism to achieve high-efficiency printing with a resolution of 25 μm and a speed of 55 mm3·s−1 within a few seconds [100]. This method allows support-free fabrication with high precision and high speed, but its applicability is limited by the compatibility requirements of laser light sources with materials.

Overall, although new methods such as CLIP, CAL, and xolography continue to emerge, DLP has remained a mainstream technology in ceramic photopolymerization due to its ability to rapidly and accurately fabricate ceramic components.

A further development direction is projection PμSL, with a resolution range of 0.6–30 μm and a build area of approximately 90 mm × 50 mm [101]. PμSL relies on focused ultraviolet light to induce single-photon absorption, thereby achieving high efficiency and rapid printing [102]. By introducing high-precision lenses between the projector and the resin layer, the resolution can be further enhanced, while the XY-plane motion of the system ensures printing accuracy for large-scale or multiple components. In 2018, BMF Materials Technology Co., Ltd. (Dongguan, China) was the first to commercialize PμSL technology (Figure 9), advancing its applications in the field of micro/nano-fabrication [101].

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the 3D printing system [101].

Binder Jetting Printing (BJP) is a rapidly developing ceramic AM technology. Its working principle involves selectively depositing liquid binders onto ceramic powder layers using an inkjet print head, thereby bonding particles layer by layer to construct complex 3D green bodies. This technique does not require support structures, offers high forming efficiency, relatively low cost, and enables the fabrication of complex topological parts that are difficult to achieve with conventional processes. Therefore, it has demonstrated significant advantages in the field of rapid prototyping. However, BJP-fabricated parts generally require subsequent debinding, sintering, and infiltration processes to obtain final components. Due to the limited powder packing density, sintered samples typically exhibit an inherent porosity of about 50–60%, leading to insufficient mechanical performance, while also being prone to significant shrinkage and deformation during sintering. At present, its applications are mainly focused on prototypes, molds, and porous scaffolds for non-load-bearing structures.

To address these limitations, research has concentrated on material systems and process optimization. On the one hand, introducing multimodal powders (a mixture of coarse, fine, and nanoscale particles) to fill interparticle voids can effectively enhance the density of green bodies [103]; On the other hand, the development of functionalized binders (e.g., slurries containing nanoparticles) has also become an important strategy for improving forming performance. Studies on polyethylene-based 3D-printing systems have shown [104] that adding approximately 15 wt% of nanoparticles can increase the relative density of the printed green bodies by ~30%, suggesting that similar nanoparticle-assisted packing strategies may also be beneficial for ceramic systems. At the same time, the compressive strength significantly rises from 76 kPa to 641 kPa. With the continuous advancements in powder characteristics, binder chemistry, and post-processing techniques, the BJP technology is expected to be applied more widely in fields such as functional gradient devices, porous catalytic supports, and customized biomedical scaffolds.

LSD is a process in which high-solid-content ceramic slurry is spread layer by layer and dried, thereby forming powder layers. Driven by capillary forces, the powders in the slurry achieve dense packing, thereby ensuring the stability of interlayer bonding. Combined with BJ as an auxiliary technique, LSD enables the layer-by-layer construction of two-dimensional cross-sections with a typical layer thickness of about 100 μm, ultimately yielding 3D structural components, commonly referred to as LSD printing.

This method can be further coupled with the liquid silicon infiltration (LSI) process to successfully fabricate Si–SiC components with complex topologies and fine features. The slurry system uses water as the medium. Its main components are irregular SiC particles. In addition, carbon sources and a small amount of organic additives (<2 wt%) are also added. After the formation of LSD, the samples are pretreated at ~800 °C and subsequently subjected to LSI at 1400 °C to achieve densification and enhanced performance.

4.2.4. Porosity, Pore Size Distributions, and Percolation

AM lattices (DIW) enable designed macroporosity (hundreds of μm–mm) with narrow PSD and tunable percolation paths; BJ yields interconnected meso-/macropores; tape-cast supports typically present fine, less-connected porosity after lamination/sintering. Effective diffusivity scales are directly proportional to the open porosity and pore shape factor. Table 5 and Table 6 demonstrate how fabrication routes govern pore architecture and densification behavior, which in turn control mass transport and structural stability in porous ceramic systems.

Table 5.

Comparison table of pore characteristics and effective diffusivity for different porous material fabrication routes.

Table 6.

Comparison table of post-sintered relative density, grain size, pore shape factor, and linear shrinkage for different ceramic systems via AM processes.

Normalized view of as-printed vs. post-sintered attributes for representative systems; values are indicative and process-dependent.

4.3. Sintering and Densification Technologies

4.3.1. HIP

HIP is a densification process in which high temperature and constant high pressure are applied in an inert gas medium. For ceramics with low self-diffusion coefficients, it is difficult to achieve complete densification through conventional sintering. Therefore, HIP can effectively enhance sintering behavior by increasing the diffusion driving force.

Taking BaTiO3 as an example, this material, as an important electronic ceramic, is widely used in household appliances, communications, and computers [105], and its dielectric properties are closely related to its density. Feng Yilong et al. [106] demonstrated that applying HIP treatment to BaTiO3 green bodies in a graphite-heated furnace not only effectively eliminated defects and micropores but also significantly suppressed grain growth. As a result, the grains in HIP-sintered samples were finer than those in conventionally air-sintered samples, thereby improving material performance.

For Si3N4 ceramics, which exhibit inherently poor sinterability, HIP has also shown distinct advantages. Li Hongtao et al. [107] used HIP to promote densification, ultimately obtaining a fine-grained structure dominated by β-Si3N4 with uniform microstructure, thereby significantly enhancing mechanical properties.

For transparent ceramics, achieving extremely high density is necessary because any residual porosity can lead to strong light scattering and severely reduce transparency. By combining high temperature and high pressure in the HIP process, it can effectively eliminate porosity, giving it unique advantages in the fabrication of transparent ceramics. For example, tetragonal zirconia polycrystals subjected to HIP not only achieved excellent transparency but also exhibited higher fracture toughness. Similarly, Nd:YAG transparent ceramics sintered at 1650 °C and 150 MPa of argon for 3 h attained the high transparency and superior optical quality necessary for laser applications, thus overcoming the bottleneck associated with residual porosity in conventional sintering [108].

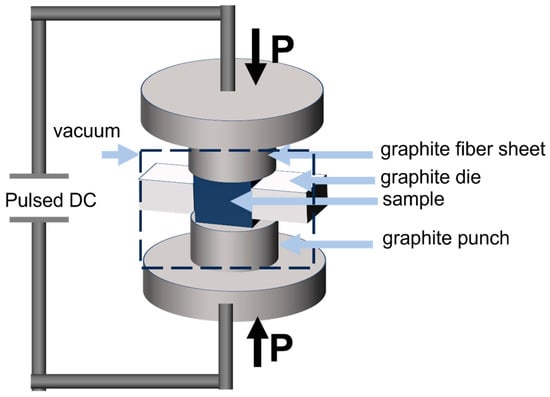

4.3.2. SPS

Compared with conventional sintering methods, SPS can generate extremely high temperatures in an extremely short period of time, with the heating rates reaching up to 1000 °C/min. Plasma activation promotes surface atom mobility at the grain boundaries, significantly accelerating diffusion processes and facilitating densification (Figure 10). The application of static pressure during SPS further enhances densification by accelerating dislocation motion and the diffusion of surface defects. However, excessive pressure may lead to plastic deformation of grains, making precise control of applied pressure essential. Sintering temperature is another critical parameter. Lu Saijun et al. [109] reported that when the sintering temperature of Ti(C,N)-based cermets was limited to 1400 °C, insufficient powder diffusion resulted in low microstructural density; as the temperature increased, densification and mechanical properties improved significantly. For nanoceramics, however, excessively high temperatures cause rapid grain growth, thereby reducing density. Therefore, optimizing the temperature range becomes particularly important.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of discharge operation principle [110].

SPS demonstrates unique advantages in the densification of difficult-to-sinter ceramics. For example, CrN, known for its outstanding wear and corrosion resistance, is considered a potential substitute for TiN coatings. However, it tends to decompose into Cr2N at high temperatures, making densification difficult through conventional sintering. Owing to its rapid heating and efficient mass transport, SPS enables dense sintering of CrN ceramics at relatively lower temperatures. Similarly, B4C, characterized by strong covalent bonding and a low self-diffusion coefficient, is difficult to densify by conventional means. SPS, through rapid heating of nanopowders and suppression of grain growth, allows B4C green bodies to achieve dense structures while retaining excellent properties.

For ultra-high-temperature ceramics, conventional sintering often requires temperatures above 2000 °C to achieve densification, which easily leads to unreacted intermediate phases, reducing purity and oxidation resistance. The rapid heating characteristic of SPS offers a new solution. For instance, ultra-high-temperature ceramics such as Ta2AlC, TaC, and ZrB2–SiC, after SPS treatment, not only exhibited significantly shortened sintering times but also achieved superior mechanical properties and oxidation resistance due to fine-grain strengthening effects [111].

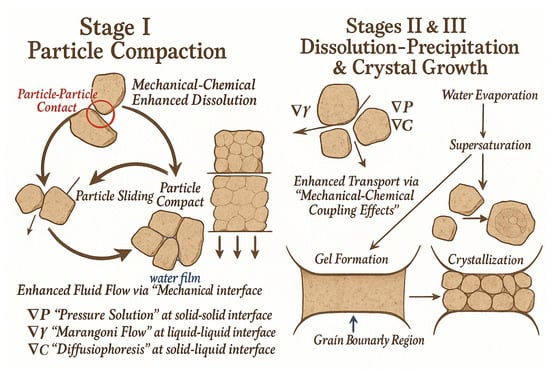

4.3.3. Cold Sintering Process (CSP)

Although HIP and SPS reduce sintering temperatures to some extent, they still cannot be categorized as true “low-temperature sintering” techniques. In recent years, the proposal of the CSP has provided a novel solution to this challenge. By introducing transient liquid-phase solvents, CSP enables densification of ceramics below 300 °C. The densification process generally proceeds through three stages: particle rearrangement and sliding, dissolution–precipitation of particles, and crystal growth (Figure 11) [112].

Figure 11.

Densification mechanism of the CSP [112].

At present, CSP has been successfully applied to a variety of systems, including oxide ceramics, ceramic/ceramic composites, microwave dielectric ceramics, ferroelectric and piezoelectric ceramics, solid electrolytes, thermoelectric materials, and ceramic/2D nanocomposites. For instance, the conventional sintering temperature of zirconia-based ceramics typically exceeds 1400 °C, which entails enormous energy consumption and inherent process limitations. Guo et al. [112] successfully fabricated 8 mol% Y2O3-stabilized zirconia ceramics with a relative density of ~96% at 300 °C by combining CSP with low-temperature post-annealing. This approach effectively reduced energy consumption. Similarly, by introducing acetic acid as a transient liquid phase, researchers obtained ZnO ceramics with a relative density as high as 98%, fine grain size (<1 μm), and excellent electrical properties. Song et al. [113] further reported the first successful preparation of Bi2O3 ceramics with a relative density of 99.13% at 270 °C and 300 MPa, where the densification process followed the dissolution–recrystallization–growth mechanism of cold sintering.

In catalytic ceramic components, processing- and scale-related factors can directly influence reaction pathways rather than acting solely as fabrication constraints. Subtle variations in local structure and interfacial chemistry affect reactant accessibility, intermediate stabilization, and heat dissipation, thereby modifying catalytic selectivity and deactivation behavior. Moreover, compositional interactions may evolve under operating conditions, leading to gradual changes in the local chemical environment of active sites.

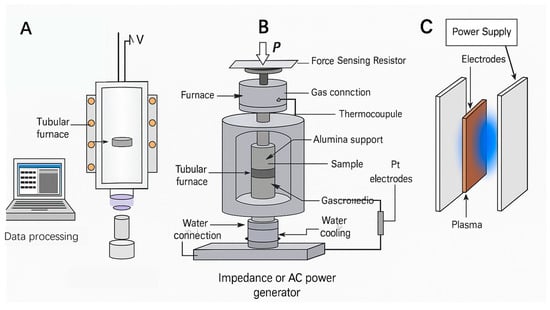

4.3.4. Flash Sintering (FS)

FS is a novel energy-efficient sintering technique that relies on Joule heating to achieve rapid densification of particulate materials within an extremely short time (<60 s) [58,114,115,116]. During FS, once the furnace temperature and sample current exceed critical thresholds, the ceramic green body instantaneously enters the densification stage. This phenomenon has been validated in various oxide systems, including yttria-stabilized zirconia, magnesia-doped alumina, strontium titanate, cobalt–manganese oxides, titanium dioxide, and magnesium aluminate spinel [116]. A typical characteristic of FS is the sudden increase in electrical conductivity concurrent with densification onset, revealing the strong coupling between electric fields and sintering kinetics.

Figure 12 illustrates FS apparatus developed by different research groups: the sample may be suspended in a tube furnace via platinum wire electrodes and triggered by continuous high voltage for sintering (Figure 12A); alternatively, it may be placed between two platinum electrodes and rapidly densified under an alternating electric field (Figure 12B). FS can also be implemented using an SPS system, where the sample is encapsulated in a graphite mold and driven by pulsed direct current. Other methods include positioning the sample between parallel-plate capacitors to achieve non-contact sintering through a strong electric field (Figure 12C). There is also a device at Rutgers University, where the sample is clamped between ceramic substrates, and FS is triggered by high electric fields generated from resistance wires wound around the substrates.

Figure 12 presents schematic diagrams of various FS experimental setups [117,118,119,120]. During the processing of FS, ceramic powders are typically uniformly mixed with binders, dispersants, or sintering aids, and then shaped into specific geometries through cold pressing or slurry casting—such as dog-bone specimens (DBS), cylinders, or rods (Figure 12A–C). When FS is performed using an SPS system, the green body must possess sufficient strength to withstand the applied pressure.

Figure 12.

(A–C) Schematic diagrams of different FS experimental setups [117,118,120].

In mechanistic studies, the main focus is on the effects of processing parameters, including electric field strength and polarity, particle size, applied pressure, atmosphere, catalytic activity of electrode materials, sample geometry, and material properties. Francis [121] demonstrated that under an electric field of 100 V·cm−1, the shrinkage strain of 3YSZ samples increased significantly with uniaxial pressure, indicating that pressure plays a promoting role in the densification process.

Furthermore, the mechanism of FS is also related to classical sintering theory. As early as 2010, prior to the first report of FS, Ghosh et al. [122] discovered that an electric field of 4 V·cm−1 could significantly suppress grain growth during the annealing of 3YSZ, suggesting that electric fields exert an important influence on high-temperature microstructural evolution. Subsequently, Chaim [123] proposed the liquid film capillarity model, in which localized Joule heating generates a liquid phase at particle contact points. Surface tension induces particle rearrangement, thereby accelerating densification.

At the same time, the thermal runaway model has been widely used to explain FS. Nearly all ceramic materials—whether ionic, electronic, or semiconducting conductors—exhibit a negative temperature coefficient of resistivity, whereby resistivity decreases with increasing temperature. This results in exponential growth of heating power, ultimately triggering accelerated densification [124].

In addition, defect-related mechanisms have been proposed. For example, the formation of Frenkel pairs can reduce resistivity and promote increased diffusion and sintering rates [125]; Nonlinear interactions between selective Joule heating and intrinsic fields may trigger “grain boundary self-diffusion avalanches.” FS may also induce partial electrochemical reduction in ionic conductors [126,127]; Furthermore, the generation of anomalous electrons, holes, and point defects can lead to unconventional grain growth, electronic conductivity, electroluminescence, and even phase transitions [128,129,130]. These phenomena all suggest that FS introduces unique non-equilibrium structures in ceramics.

Overall, FS represents a highly promising and innovative sintering technique that can significantly reduce sintering time and temperature while producing unique microstructures. However, there are still many controversies regarding the mechanism of this phenomenon, as current models lack unified and convincing evidence. From the perspective of engineering applications, FS still has considerable progress to achieve before widespread adoption.

Flash sintering (FS) considerations for catalysis-relevant ceramic components extend beyond densification efficiency to include thermal runaway control and electrically driven microstructural evolution. During FS, grain-boundary (GB) chemistry can actively steer catalytic selectivity and poisoning behavior by governing defect accumulation and segregation at interfaces. Moreover, dopants or integrated electrodes modify local electric fields and GB transport, thereby shifting reaction onset conditions and stability regimes under catalytic operation.

4.4. Fabrication Technologies for High-Entropy Ceramics

4.4.1. Chemical Vapor Infiltration (CVI)

CVI involves introducing precursor gases into the pores of fiber preforms, where chemical reactions at elevated temperatures generate a ceramic matrix, thereby forming composites [131]. This process has broad applicability and can be used for various ceramic matrices, such as SiC, BN, B4C, and TiC [132]. CVI is typically carried out at relatively low temperatures (<1200 °C), avoiding fiber degradation and forming difficulties associated with high-temperature sintering. Moreover, gaseous precursors can deeply penetrate porous preforms, making this technique suitable for fabricating large-scale and complex-shaped composite components. However, its limitations include complex equipment, high cost, limited densification (porosity of ~5–20%), and prolonged processing cycles. For example, the preparation of C/SiC composites via CVI can take more than three months [133].

4.4.2. Reactive Melt Infiltration (RMI)

The principle of RMI is to infiltrate liquid or gaseous metals or alloys into porous carbon matrices or carbon-containing intermediates, and then generate a ceramic matrix through liquid–solid or gas–solid reactions. In liquid-phase infiltration, capillary forces drive molten silicon into pores, while in gas-phase infiltration, gaseous silicon serves both as the reactant and infiltrant, achieving faster penetration rates and greater depths. This technique originates from reaction-bonded SiC and porous body filling [134]. RMI has many advantages, such as high efficiency, low cost, high densification, and near-net shaping. Its processing cycle is much shorter than CVI and polymer infiltration pyrolysis (PIP), and its raw materials (e.g., SiC and silicon powder, ~200 RMB/kg) are significantly less expensive than CVI and PIP precursors like trichloromethylsilane (~500 RMB/kg) or PCS (~4000 RMB/kg). Consequently, RMI has developed rapidly.

Nonetheless, RMI has drawbacks: (1) high-temperature melts can corrode carbon fibers, reducing composite mechanical properties; (2) residual metals may remain in the matrix, compromising high-temperature mechanical strength, oxidation resistance, and ablation resistance [135]. For example, Gao et al. [136] fabricated C/Si–Y–C composites using Si–Y alloys via RMI at 1280–1400 °C, achieving the highest density (2.25 g/cm3) and lowest open porosity (3.32%) at 1370 °C. The composite materials are mainly composed of C, SiC, and YSi2, and no residual Si was detected. Compared with C/SiC composites fabricated via RMI at 1500 °C, improvements were observed in flexural strength, fracture toughness, thermal diffusivity, and thermal conductivity. Similarly, Yan Chunlei et al. [137] prepared C/SiC composites by gas-phase infiltration at 1650 °C, obtaining a density of 2.41 g/cm3, a flexural strength of 268 MPa, and a fracture toughness of 11.33 MPa·m1/2.

Overall, each processing method for continuous fiber-reinforced CMCs has its respective advantages and limitations. For example, CVI and PIP still face challenges in cost and processing cycle, which restrict their broader application. The development of low-cost processes for continuous fiber-reinforced CMCs has thus become a primary trend. However, performance degradation is often unavoidable with cost reduction, highlighting the urgent need for further optimization of low-cost processes to balance cost control with performance enhancement, thereby expanding their application potential. Currently, low-cost fabrication methods for continuous fiber-reinforced CMCs include RMI, NITE, SI-HP, and Lanxide processes.

4.4.3. Solid-State Sintering Method

Nanoinfiltration and transient eutectoid (NITE) processing is a technique for fabricating CMCs. This method involves infiltrating fiber preforms containing interfacial phases with nanosized ceramic powders and sintering additives, followed by hot pressing at high temperature and pressure to achieve densification [138]. The process flow is illustrated in Figure 13 [139]. Composites fabricated via this method exhibit excellent properties such as high thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance, strength, and toughness. However, because the process is based on hot-press sintering, the addition of sintering additives is often required, which may influence composite properties, and the technique faces challenges in producing large-scale and complex-shaped components. Katoh et al. [140] employed the NITE method using nano-SiC powders with small amounts of Al2O3 and Y2O3 sintering additives to fabricate SiC/SiC composites, which demonstrated favorable thermomechanical properties.

Figure 13.

NITE process preparation flowchart [139].

Slurry infiltration and hot pressing (SI-HP) is a traditional method for fabricating CMCs, in which ceramics are introduced into the matrix in the form of solid particles. Ceramic powders, sintering aids, and solvents are prepared into a slurry that infiltrates carbon fibers, which are then woven into cloth without a weft. After slicing and mold pressing, hot-press sintering is applied to obtain composites, achieving the combination of carbon fibers and ceramic matrices in a single cold/hot forming process [141]. The advantages of this process include simplicity, short cycle time, low cost, high material density, and fewer defects. Its disadvantages are the relatively high processing temperature and pressure, which may damage the fibers and impair material performance; agglomeration of powders in the slurry can block pores; and it is difficult to produce large-scale or complex-shaped components [142]. Xiao et al. [143] prepared C/ZrB2–SiC composites by hot-press sintering carbon fibers with PyC and SiC interphases impregnated with SiC and ZrB2 powders at 1900 °C. The resulting composites exhibited a flexural strength of 309 MPa. Vinci et al. [144] employed ZrC/TaC + SiC slurries to infiltrate unidirectional fiber preforms, and successfully fabricated C/ZrC–SiC and C/TaC–SiC composites through hot pressing at 1900 °C.

The in-situ reaction (IR) method involves mixing transition metals or their oxides with organic carbon precursors such as phenolic resin to prepare a slurry, which is then infiltrated into porous preforms. At elevated temperatures, the transition metals or oxides react in situ with the carbon matrix to form ceramic matrices. Similar to RMI, this method has the advantages of low cost and short processing cycles, but it can also cause fiber damage [145]. However, since the process does not involve molten metal infiltration, the required heat-treatment temperature is relatively lower. For instance, Li et al. [146] prepared C/ZrC–SiC composites using zirconium powder, silicon powder, and phenolic resin as raw materials via the IR method. The composites exhibited a flexural strength of 257 MPa and an elastic modulus of 59.3 GPa. Shen et al. [147] introduced ZrO2 into preforms using ZrOCl2·8H2O as a precursor through pyrolysis. ZrO2 then reacted in situ with PyC to form ZrC, yielding C/ZrC composites. After oxyacetylene flame ablation for 60 s, the composites demonstrated a linear ablation rate of 0.6 μm/s.

4.5. Powder Processing Chain: From Chemistry to Properties

Beyond freeze-drying, low-temperature dehydration/deagglomeration of co-precipitates offers a solvent- and vacuum-free route that simplifies processing. Powder chemistry (impurity content, degree of agglomeration), particle-size distribution, and precursor routes (co-precipitation, sol–gel, SHS) define sintering windows and densification mechanisms. Consolidation methods—CIP, tape casting, injection molding, and AM packing—govern green density and pore architecture. Subsequent sintering strategies (SPS; HIP; CSP; FS) set grain size, grain-boundary chemistry, and residual porosity, which in turn control thermal conductivity, strength/toughness, and catalysis-relevant transport/selectivity. Coordinated optimization across these stages reduces energy consumption while meeting application metrics (e.g., effective diffusivity for catalyst supports) [148].

5. Conclusions

As key materials combining outstanding mechanical, thermal, and chemical stability, advanced ceramics have made substantial progress in recent years, particularly in the context of catalytic applications that demand durability, multifunctionality, and structural integration. In this review, the central focus is placed on catalytic functionalities—such as hydrogen evolution (HER), oxygen evolution/reduction (OER/ORR), CO2 reduction (CO2RR), and environmental catalysis—while ceramic fabrication technologies are discussed primarily as enablers for tailoring microstructural features (e.g., porosity, grain boundaries, composition, and defect chemistry) that directly govern catalytic performance.

From this perspective, emerging material systems—including high-entropy oxides, nitrides, and carbides, as well as polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs) and their composites—offer unique advantages for catalysis by providing abundant and diverse active sites, enhanced electronic and ionic transport, and exceptional thermal and chemical stability. These characteristics make them promising platforms for key catalytic processes such as methane reforming, water electrolysis, and CO2 conversion, where conventional supports often suffer from deactivation or structural degradation. Meanwhile, advanced fabrication technologies such as additive manufacturing, spark plasma sintering, and cold sintering enable precise control over hierarchical porosity, phase distribution, and interfacial chemistry, thereby allowing catalytic structures to be designed in a more targeted and application-driven manner.

Overall, this review highlights how the convergence of advanced ceramic materials and fabrication technologies can support high-quality development in catalysis, defined in terms of energy-efficient processing, green manufacturing, multifunctional integration, and long-term operational stability. These advances indicate that advanced ceramics are evolving from passive structural materials into active, system-level components for next-generation catalytic and energy technologies, providing a solid foundation for sustainable progress in energy, environmental remediation, and high-end manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X. and P.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.Y.; validation, J.Y.; investigation, P.L.; resources, J.H.; data curation, W.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; visualization, P.L.; supervision, J.L.; project administration, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Open Fund Project of New-type Think Tanks in Shaanxi Universities. Research on the Development Mechanism of Light Industry Talent Cultivation (ACNM-202301), Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education in China (No. 24XJA630005). The authors would like to thank Shaanxi University of Science & Technology for the assistance provided.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Su, F.; Su, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lin, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z. Generative shaping and material-forming (GSM) enables structure engineering of complex-shaped Li4SiO4 ceramics based on 3D printing of ceramic/polymer precursors. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 57, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.L.B.D.; Hirata, R.; Witek, L.; Jahlk, E.B.; Nayak, V.V.; de Souza, B.M.; de Souza, B.M. Manufacturing and characterization of a 3D printed lithium disilicate ceramic via robocasting: A pilot study. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 143, 105867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, Y.R.; Kang, J.H.; Yun, Y.N.; Park, S.W.; Lim, H.P.; Yun, K.D.; Jang, W.H.; Lee, D.J.; Park, C. Ceramic 3D printing using lithium silicate prepared by sol-gel method for customizing dental prosthesis with optimal translucency. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 39788–39799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Shang, Z.; Tian, L. Preparation of porous SiC ceramics skeleton with low-cost and controllable gradient based on liquid crystal display 3D printing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 5432–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Xue, F.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, D. 3D printing of SiC ceramic: Direct ink writing with a solution of preceramic polymers. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 5294–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baux, A.; Jacques, S.; Allemand, A.; Vignoles, G.; David, P.; Piquero, T.; Stempin, M.-P.; Chollon, G. Complex geometry macroporous SiC ceramics obtained by 3D-printing, polymer impregnation and pyrolysis (PIP) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD). J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 3274–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Su, R.; Gao, X.; Li, S.; Wang, G.; He, R. Microstructures, mechanical properties and electromagnetic wave absorption performance of porous SiC ceramics by direct foaming combined with direct-ink-writing-based 3D printing. Materials 2023, 16, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, R.; Ping, Z. Lattice-structured SiC ceramics obtained via 3D printing, gel casting, and gaseous silicon infiltration sintering. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 6488–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.F.; Ma, N.N.; Chen, J.; Zhu, M.; Chen, W.-H.; Huang, C.-C.; Huang, Z.-R. SiC ceramic mirror fabricated by additive manufacturing with material extrusion and laser cladding. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; He, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, N.P.; Xu, H. Stereolithography 3D printing of SiC ceramic with potential for lightweight optical mirror. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 18785–18790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costakis, W.J.; Rueschhoff, L.M.; Diaz-Cano, A.I.; Youngblood, J.P.; Trice, R.W. Additive manufacturing of boron carbide via continuous filament direct ink writing of aqueous ceramic suspensions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 3249–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiry, D.; Shin, H.S.; Loh, K.P.; Chhowalla, M. Low-dimensional catalysts for hydrogen evolution and CO2 reduction. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Liang, X.; Ma, F.-X.; Zhang, J.; Tan, Y.; Pan, Z.; Bo, Y.; Lawrence Wu, C.-M. Encapsulating dual-phased Mo2C-WC nanocrystals into ultrathin carbon nanosheet assemblies for efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Barile, C.J.; Pan, H. Titanium nitride-supported Cu–Ni bifunctional electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction and the oxygen evolution reaction Titanium nitride-supported Cu–Ni bifunctional electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction and the oxygen evolution reaction. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 5654–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, R.; Katayama, M.; Cha, D.; Takanabe, K.; Kubota, J.; Domen, K. Titanium Nitride Nanoparticle Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Alkaline Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, F501–F506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yoon, G.; Park, S.; Namgung, S.D.; Badloe, T.; Nam, K.T.; Rho, J. Revealing Structural Disorder in Hydrogenated Amorphous Silicon for a Low Loss Photonic Platform at Visible Frequencies. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, F.L. Silicon Nitride and Related Materials. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 83, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Bharathi, K.; Kim, D.K. Processing and Characterization of Aluminum Nitride Ceramics for High Thermal Conductivity. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangurde, L.S.; Sturm, G.S.J.; Devadiga, T.J.; Stankiewicz, A.I.; Stefanidis, G.D. Complexity and Challenges in Noncontact High Temperature Measurements in Microwave-Assisted Catalytic Reactors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 13379–13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travitzky, N.; Bonet, A.; Dermeik, B.; Fey, T.; Filbert Demut, I.; Schlier, L.; Schlordt, T.; Greil, P. Additive Manufacturing of Ceramic Based Materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xia, Z.; Molokeev, M.S.; Liu, Q. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Enhanced Luminescence of Garnet-Type Ca3Ga2Ge3O12:Cr3+ by Codoping Bi3+. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 98, 1870–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sugahara, Y. Polymer-derived ceramics for electrocatalytic energy conversion reactions. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2022, 20, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]