Abstract

The use of e-fuels, such as methanol (MeOH), is considered an alternative for the reduction of carbon emissions. MeOH can be produced from captured CO2 and green H2, with the exothermic (equilibrium-limited) reaction favoured at low temperatures and high pressures. However, CO2 is a very stable molecule and requires high temperature (>200 °C) to overcome the slow activation kinetics. In this study, MeOH was synthesized from CO2 and H2 in a packed-bed membrane reactor (PBMR) using a commercial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst and a tubular-supported, water-selective composite alumina–carbon molecular sieve membrane (Al-CMSM) immersed in the catalytic bed. A mixture of H2/CO2 (3/1) was fed into both sides of the membrane to increase the driving force of the gases produced by the reaction. The effect of the temperature of reaction (200, 220, and 240 °C), pressure difference (0 and 3 bar), and the sweep gas/reacting gas ratio (SW = 1, 3, 5) in the CO2 conversion and products yield was studied. For comparison, the reactions were also carried out in a packed-bed reactor (PBR) configuration where the tubular membrane was replaced by a metallic tube of the same size. CO2 conversion and MeOH yield are much higher in PBMR than in PBR configuration, showing the benefit of using the water-selective membrane. In PBMR, MeOH yield increases with SW and slightly decreases with the temperature, overcoming the limitation imposed by the thermodynamics.

1. Introduction

The production of CO2 from the combustion of fossil fuels is considered the main cause of anthropogenic carbon emissions and the resulting climate changes. In 2023, EU countries approved a ban on the registration of new vehicles with internal combustion engines starting in 2035 with an exception for “vehicles running exclusively on CO2-neutral fuels” [1]. Carbon-neutral fuels can be grouped into biofuels, which are derived directly or indirectly from biomass, and synthetic fuels, which are produced by chemical hydrogenation of CO2. They could not only reduce the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere but also produce valuable products such as methane, alcohols, olefins, and aromatics [2]. E-fuels (i.e., CH4, methane (CH4), MeOH, dimethyl ether (DME), and kerosene) [3] are obtained mostly from green hydrogen, produced by electrolysis of water using renewable electricity, and CO2 through carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology [3,4]. E-methanol is a liquid fuel with a high-octane number and low ignition properties, and can be used in road, aviation, and marine transport without changing the actual infrastructure. Methanol has a low carbon-to-hydrogen ratio, high oxygen content, and does not have the carbon-carbon bond, improving the combustion and reducing the exhaust emissions [5]. Differently than e-CH4, e-MeOH is liquid at room temperature and pressure and has a lower risk of climate impact since CH4 is a potent greenhouse gas. DME is more difficult to store and transport because its boiling point is −24 °C, and the production process is more difficult and requires more energy. In addition, MeOH can be used in the production of many other important products [6,7].

The MeOH synthesis takes place both directly via CO2 hydrogenation (Equation (1)) and indirectly via CO hydrogenation (Equation (3)). CO is produced by the reverse water–gas shift reaction (RWGS) (Equation (2)). As such, the overall process is limited by the thermodynamic equilibrium. MeOH synthesis is thus favoured at low temperatures and at high pressures. CO2 is referred to as an inert gas because of its very low reactivity. To increase the rate of reaction, temperatures of more than 240 °C are usually required [8,9].

CO2 + 3H2 ↔ CH3OH + H2O ΔH0 = −49.5 kJ mol−1

CO2 + H2 ↔ CO + H2O ΔH0 = +41.2 kJ mol−1

CO + 2H2 ↔ CH3OH ΔH0 = −90.5 kJ mol−1

Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 is a catalyst widely used in various industrial processes, including methanol synthesis and the water–gas shift reaction [10]. However, a major disadvantage of this catalyst is that the active metallic copper nanoparticles are prone to sintering due to the low Tammann temperature (407 °C). Water generated in Equations (1) and (2) deactivates the catalyst, causing speciation of the Cu active phase and phase separation, crystallization of ZnO and Cu particles, and the adsorption on and blocking of active sites [9,11].

In addition, a large amount of water produced accumulates in the reaction environment, limiting the equilibrium. In situ removal of water from the reaction zone by hydrophilic membranes can overcome the limitations of the thermodynamic equilibrium, promoting higher conversion rates, improving methanol yields, and enhancing catalyst stability [12,13,14,15,16].

Zeolite membranes have a well-defined pore structure; the incorporation of heteroatoms, such as Al, results in a more hydrophilic material but one that is less stable in the presence of steam [17]. Carbon molecular sieve membranes (CMSM) have emerged as a promising material for gas separation at high temperatures where polymeric membranes are not stable (200–400 °C) [18]. The gas permeation mechanism in CMSM is the combination of molecular sieving (size discrimination, where gases smaller than the pore size will permeate) and adsorption diffusion based on the preferential adsorption of the gases with the pores; the gas with more adsorption will pass preferentially, blocking at the same time the passage of other gases [19]. Supported composite alumina–carbon molecular sieve membranes (Al-CMSM) were prepared by the one dip-dry carbonization method of novolac phenolic resin loaded with various concentrations of hydrophilic boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) nanosheets in the dipping solution [20]. The gas permeation properties of several gases (H2O, H2, CO2, N2, CO, and CH4) at the range of 150 to 240 °C were studied; in all the cases, water was the most permeable gas [21]. The experimental investigation, techno-economic assessment, and study of the mass and heat transport phenomena of a PBMR for the direct conversion of CO2 to DME using CuO-ZnO-Al2O3/HZM-5 bifunctional catalyst and Al-CMSM water-selective membrane prepared from a dipping solution containing 0.8% of boehmite were reported by Poto et al. [22]; the results demonstrate that the PBMR outperforms the packed-bed reactor (PBR) in most of the experimental conditions.

The results reported by Poto et al. on DME have shown that the CMSMs can be effectively used in enhancing the conversion of reactions at temperatures higher than 200 °C. As such, these membranes could also be used for methanol production to increase the conversion per pass, thus reducing the recycle compression costs in the methanol synthesis loop.

In this study, the synthesis of MeOH using a packed-bed membrane reactor with CuO-ZnO-Al2O3 as a catalyst and an Al-CMSM as a membrane is reported for the first time.

The effect of the temperature of reaction, pressure difference, and the sweep gas/reacting gas ratio on the CO2 conversion and product yield was studied. To investigate the effect of the removal of water by the selective membrane, reactions were also carried out in a packed-bed reactor (PBR) configuration where the membrane was replaced by a tube of the same shape.

2. Results and Discussion

As the membrane reactor has both permeate and retentate sides, the definition of conversion and yields should be modified. To evaluate the performance of the reactor, the selectivity, conversion, and yield have been calculated according to the following equation. The formula takes into account the possible loss or cofeeding of reactants (i.e., through back-permeation of sweep gas in the reaction zone).

| CO2 transmembrane flow | ||

| Reactant loss | ||

| Reactant cofeeding | ||

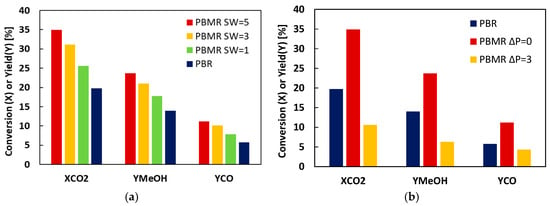

The effect of the ratio of sweep gas to reacting gas (SW) on CO2 conversion (XCO2) and MeOH CO yields (YMeOH and YCO) in the PBMR is shown in Figure 1a. The conversion and yields in PBMR are higher than in PR configuration, indicating the positive effect of the removal of water by the Al-CMSM. With increasing SW, XCO2, YMeOH, and YCO increase because the partial pressure of the gases in the permeate drops as the flow of the sweep gas increases. A strong decrease in all relevant parameters is detectable when introducing a pressure difference between retentate and permeate, as can be seen from Figure 1b; the passage of all the gases increases, losing reactants decreasing at the same time the partial pressure difference in the products.

Figure 1.

Effect of: (a) the ratio of sweep gas to reacting gas flows (SW) and (b) the pressure difference, on the CO2 conversion and MeOH, CO yields. Temperature 200 °C.

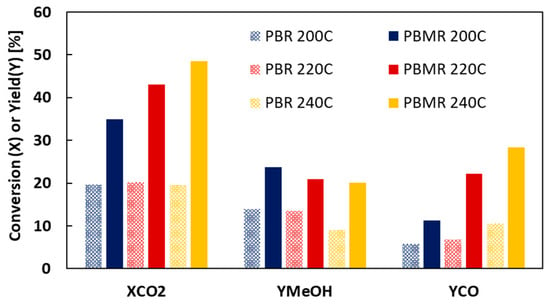

The effect of the temperature reaction on the MeOH synthesis in PBR (without membrane) and PBMR (with Al-CMSM) is presented in Figure 2 and Table A1. The kinetics of CO2 conversion are enhanced with the temperature; more water is produced and removed by the membrane, shifting the equilibrium to the product. In the PBR configuration, the change in conversion is very small because water is not removed. In both types of reactors, MeOH yield decreases, and CO yield increases with the temperature; the production of MeOH by CO2 hydrogenation is exothermic (Equation (1)); therefore, the reaction is favoured at lower temperatures. CO is produced by the endothermic RWGS (Equation (2)); thus, the CO yield increases with the temperature; the increase is more marked in PBMR because of the removal of water.

Figure 2.

Effect of the temperature of reaction on the CO2 conversion; MeOH and CO yields in PBR and PBMR configurations. SW = 5, ΔP = 0.

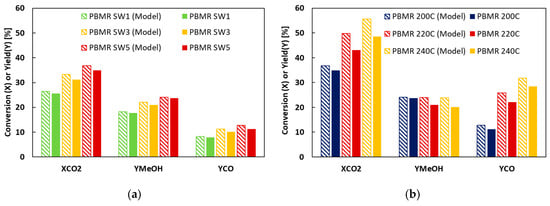

Alongside these experiments, a 1D model of the PBMR has been developed. The model is based on the CO2 hydrogenation (Equation (1)), RWGS (Equation (2)), and CO hydrogenation (Equation (3)). All relevant kinetic and permeation parameters, alongside an explanation of the governing equations of the model, have been reported in the Appendix; the main difference from the reference literature is the absence of the DME reaction, simplifying the reaction system. With the developed model programme, the CO2 conversion and the product yield were calculated; the values obtained (Model) and compared with those obtained experimentally. The comparison of the calculated (Model) and experimental values obtained by the PBMR MeOH synthesis is shown in Figure 3. For SW and temperature, the model can predict the results obtained experimentally. The discrepancies in the predicted and experimental values are because the model considers the reaction zone as consisting only of the catalyst, whereas the experimental bed is diluted with SiC.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the PBMR MeOH synthesis obtained experimentally and calculated by modelling (Model) (a) effect of SW ratio, and (b) effect of reaction temperature.

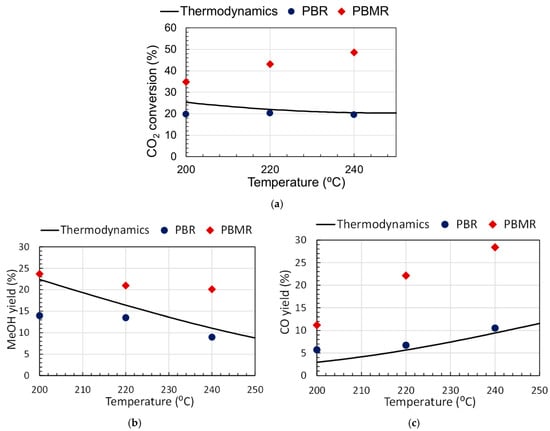

The effect of the temperature on the reaction performance in PBR and PMBR modes is depicted in Figure 4a. In the temperature range studied, the PBMR performance is well above the PBR and the thermodynamic limit. The MeOH yield slightly decreases with the temperature due to the exothermicity of the reaction (Equation (1)). The CO yield increases with the temperature because the RWGS reaction is endothermic (Equation (2)), Figure 4b. The observed enhancement of CO2 conversion with the temperature is due to the increase in CO production (Figure 4c). Therefore, to increase the production and MeOH selectivity in PBMR, the reaction should be carried out at around 200 °C.

Figure 4.

(a) CO2 conversion, (b) methanol yield, and (c) CO yield as a function of reaction temperature for PBMR and PBR at various reaction temperatures. For PBMR SW = 3, ΔP = 3 bar; the thermodynamic line was calculated from modelling.

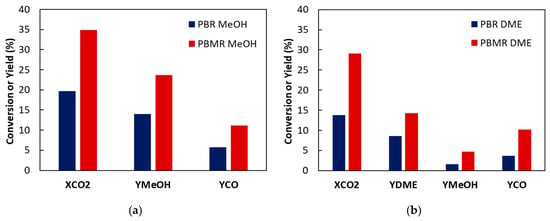

The conversion and product yield for PBR and PBMR synthesis of MeOH and DME are shown in Figure 5 and Table A2 and Table A3, respectively. Since the same membrane, reactor, and conditions were used in both cases, the results can be compared. For both reactions, CO2 conversions are higher for PBMR than PBR. CO2 conversion for MeOH synthesis is higher than for DME. A higher yield of the desired product is obtained for MeOH (23.7%) than for DME (14.3%) because fewer reactions are involved, and MeOH is an intermediate in the reaction.

Figure 5.

Comparison of CO2 conversion and product yields for PBR and PBMR synthesis of (a) MeOH 1.5 g CuO/ZnO/Al2O3 and (b) DME 1.5 g CuO/ZnO/Al2O3 and 1.5 g of HZSM-5. PBMR SW = 5, ΔP = 0, H2/CO2 ratio = 3, SW = 3, temperature 200 °C, GHSV = 400 NLkg−1h−1.

3. Experimental Methods

3.1. Al-CMSM Preparation

Supported tubular composite alumina–carbon molecular sieves membranes (Al-CMSM) were prepared by the one-dip dry carbonization step method as described before [20]. The supports used are asymmetric α-Al2O3 tubes with ID: 7 mm, OD: 10 mm, and 100 nm average pore size on the surface, provided by Inopor® (Scheßlitz, Germany). A solution was prepared by dissolving Novolac phenolic resin (as a source of carbon, 13%), ethylenediamine (0.6%), and formaldehyde (2.4%) in NMP (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). Next, the solution was heated at 90 °C for 90 min for polymerization (curing). Then, an aqueous solution containing boehmite nanoparticles with a particle size of 8–20 nm (alumisol provided by Kawaken Fine Chemicals, Singapore) was added (0.8%).

The support was dipped into the solution and dried at 90 °C overnight under continuous rotation. The coated support was carbonized under N2 inert atmosphere (i.e., 200 mL·min−1 of nitrogen) at 600 °C for 2 h using a heating rate of 1 °C·min−1). The carbonized Al-CMSM selective layer was detached from the support due to the high viscosity of the dipping solution; therefore, the solution was diluted by adding NMP in a 1:1 ratio. After carbonization, a supported Al-CMSM without defect was obtained (N2 permeance at room temperature 0.8 × 10−10 mol·m2·s−1·Pa−1)

Permeation Results

The membrane properties in terms of water permeance () and perm-selectivity () measured at 200 °C are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Properties of the membrane of this work. All membrane properties are reported at 200 °C.

The membrane prepared in this work generally has a very high permeance (i.e., of the order of 10−6) and a lower , especially for the H2O/CO2, H2O/CO, and H2O/MeOH pairs. This is clearly due to the thinner carbon layer obtained due to the dilution of the polymeric precursor.

In particular, is the smallest perm-selectivity, due to the very similar size of the two molecules. Indeed, despite capillary condensation phenomena, H2O and H2 are believed to compete for their access to the molecular sieving pores. Furthermore, is always greater than , since CO2 shows significant affinity to the membrane surface, such that, for some membranes, adsorption diffusion dominates over molecular sieving. On the other hand, and show the expected behaviour, achieving the target in most cases.

DME permeance through CMSM was measured and is reported, but the catalyst did not show any activity towards DME production, so the data is less interesting.

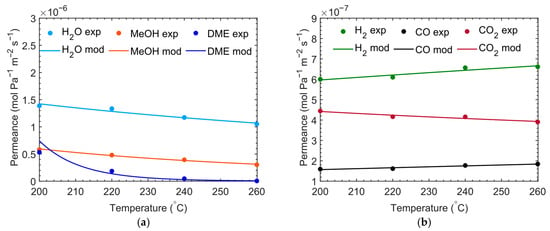

The membrane was also tested at different temperatures, and the results of permeation as a function of temperature are reported below (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Membrane properties of the CMSM used in this study in terms of water, methanol, and DME permeance (a) and H2, CO, and CO2 permeance; (b): markers and lines represent experimental and simulated data, respectively.

3.2. Methanol Synthesis

3.2.1. Catalyst

A commercial copper-based low-temperature water gas shift HiFUEL® W220 Thermo Fisher Scientific (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) cylindrical pellets (5.4 × 3.6 mm) (CuZA), with a composition of CuO(52)/ZnO(30)/Al2O3(17) (wt%) (CuZA), were used as a catalyst. The catalyst was crushed and sieved; the 50–125 µm fraction was used. Detailed information on the characteristics of the catalyst was reported in our previous paper.

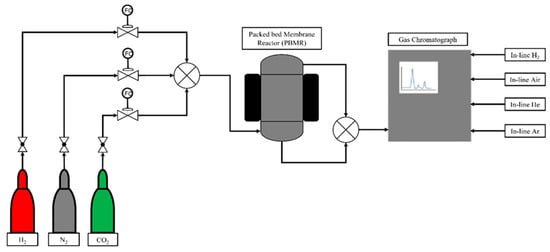

3.2.2. Packed-Bed Membrane Reactor (PBMR)

The schematic representation of the PBMR setup used for the reaction test is shown in Figure 7; the setup used is a modified version of that used for the direct synthesis of DME. The membrane reactor is a stainless-steel vessel (OD: 28.5 mm, L: 150 mm) with a top flange for the connection of the membrane tube. Both a sweep gas and a permeate line are connected to the inner side of the membrane via the top flange. The catalyst bed is placed in the outer space. Prior to the reaction test, (H2, N2, CO2) single gas permeation tests were performed to compare the results obtained one year before for the DME synthesis. Before the reaction experiments, the catalyst was reduced in situ at 280 °C for 4 h by flowing a 50% H2/N2 mixture. N2 is fed only during the reduction in the catalyst. The reactor is heated via an external jacket, and the temperature is controlled digitally through in situ controllers. While the packed bed covers the whole length of the membrane, the CuZA catalyst is in contact only with the membrane active layer. SiC was added to dilute the catalyst to avoid hot spot formation inside the reactor and achieve the desired catalytic bed ratio.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup used for the catalytic test.

For all the methanol synthesis reactions, two separate feed lines were used, one for the reaction feed and one for the sweep gas feed. The following parameters were kept constant: (a) H2/CO2 molar ratio of 3, both in the feed to the reaction zone and inside the tube as sweep gas; (b) retentate pressure of 27 bars; and (c) GHSV (gas hourly space velocity) of 400 NL/hgcat−1. The variable parameters were (a) ratio of sweep gas to reacting gas flows (SW) 1, 3, 5, (b) pressure difference between retentate and permeate side (ΔP 0, 3 bar), and (c) reaction temperature (T) (200, 220, 240 °C). The operating conditions of the PBMR are shown in Table 2. The reaction performance in terms of CO2 conversion (XCO2), methanol, and CO yield (YMeOH and YCO, respectively) was calculated using the modelling methodology reported before.

Table 2.

PBMR experiments with the corresponding operating conditions.

3.2.3. Packed-Bed Reactor (PBR)

To study the effect of the removal of water by the Al-CMSM, the membrane was replaced by a metallic tube of the same size, thus preventing permeation.

4. Conclusions

The conversion and yields in PBMR are higher than in PR configuration, indicating the positive effect of the removal of water by the Al-CMSM. By increasing SW, XCO2, YMeOH, and YCO increase because the partial pressure of the gases in the permeated drops as the flow of the sweep gas increases.

As the temperature of reaction increases: (a) CO2 conversion is enhanced because of the increase in the kinetic of reaction; the CO formation by RWGS increases due to endothermicity of the reaction, and MeOH is reduced because the CO2 hydrogenation is exothermic.

CO2 conversion and product yield are well above the thermodynamic limit, reflecting the concept of the PBMR with the removal of water. A model for MeOH synthesis was developed; the values obtained by modelling are similar to those obtained experimentally.

An extension of this work requires a dedicated techno-economic analysis to assess the influence of the sweep gas separation and recompression on the total economics of the process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G., S.P.; methodology, All authors; investigation, S.P.; resources, F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.L.T., D.A.P.T.; writing—review and editing, F.G.; funding acquisition, F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101006656 (GICO project).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

CO2 conversion and product yield for PBR and PBMR MeOH synthesis at various reaction conditions.

Table A1.

CO2 conversion and product yield for PBR and PBMR MeOH synthesis at various reaction conditions.

| Parameters | Conversion CO2 [%] | Yield MeOH [%] | Yield CO [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweep/Reacting Gases SW [-] | Pressure Difference ΔP [bar] | Temperature [°C] | PBR | PBMR | PBR | PBMR | PBR | PBMR | |

| MR1 | 1 | 0 | 200 | 19.7 | 5.6 | 14.0 | 17.7 | 5.7 | 7.9 |

| MR6 | 3 | 0 | 200 | 19.7 | 31.1 | 14.0 | 21.0 | 5.7 | 10.1 |

| MR2 | 5 | 0 | 200 | 19.7 | 34.9 | 14.0 | 23.7 | 5.7 | 11.2 |

| MR5 | 5 | 3 | 200 | 19.7 | 10.6 | 14.0 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 4.3 |

| MR3 | 5 | 0 | 220 | 20.2 | 43.1 | 13.5 | 21 | 6.7 | 22.1 |

| MR4 | 5 | 0 | 240 | 19.5 | 48.5 | 9.0 | 20.1 | 10.6 | 28.4 |

Table A2.

CO2 conversion and product yield for PBR and PBMR MeOH synthesis at various reaction temperatures obtained experimentally and thermodynamically (Therm).

Table A2.

CO2 conversion and product yield for PBR and PBMR MeOH synthesis at various reaction temperatures obtained experimentally and thermodynamically (Therm).

| Temperature [°C] | CO2 Conversion [%] | MeOH Yield [%] | CO Yield [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBR | PBMR | Therm | PBR | PBMR | Therm | PBR | PBMR | Therm | |

| 200 | 19.7 | 34.9 | 25.4 | 14.0 | 23.7 | 22.4 | 5.7 | 11.2 | 3.0 |

| 220 | 20.2 | 43.1 | 22.1 | 13.5 | 21.0 | 16.4 | 6.7 | 22.1 | 5.7 |

| 240 | 19.5 | 48.5 | 20.5 | 9.0 | 20.1 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 28.4 | 9.4 |

Table A3.

CO2 conversion and product yield for PBR, PBMR for DME synthesis are reported in a previous work.

Table A3.

CO2 conversion and product yield for PBR, PBMR for DME synthesis are reported in a previous work.

| Temperature [°C] | CO2 Conversion [%] | MeOH Yield [%] | CO Yield [%] | DME Yield [%] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBR | PBMR | PBR | PBMR | PBR | PBMR | PBR | PBMR | |

| 200 | 13.7 | 29.1 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 10.2 | 8.6 | 14.3 |

Appendix B. Model Equations and Assumptions

The phenomenological reactor model relies on the following assumptions:

- Steady state conditions.

- 1D ideal plug flow (i.e., axial and radial dispersion is neglected by considering L/dp ≥ 50 and D/dp ≥ 25, respectively).

- Kinetic control regime (i.e., the solid and gas phases are described as a single pseudo-homogeneous phase, due to the absence of mass transfer limitations).

- Negligible pressure drops in the permeation side.

- Kinetics by Lu et al. [23] valid for conventional and membrane reactors.

- Inert membrane material under reaction conditions.

Accordingly, the membrane reactor model consists of mass and energy balances for both the reaction and permeation zones, and a momentum balance for the reaction zone only. For each of the six chemical species that take part in the process (i), the following equations hold:

where is the flux of component i through the membrane, as defined in Equation (A3). By definition, is positive when the species permeates from the reaction to the permeation zone.

is the permeance of the component i and and are its partial pressures in the reaction and permeation zone, respectively. The selectivity of water with respect to the component i is defined as follows:

In this work, the dependency of on the composition was neglected because the composition of water (i.e., the primarily permeating species) does not change significantly. In addition, it was assumed that the permeation flux is limited by the transport through the membrane-selective layer. Indeed, gas permeation is usually not affected by concentration polarization phenomena (i.e., resistance to the transport from a bulk phase to the membrane surface) because of the high diffusivity and low permeability of the gases, when compared to liquids [24].

Coke formation and water adsorption (i.e., main causes of catalyst deactivation) are avoided due to the relatively low reaction temperatures and the water removal, respectively. The rate expressions derive from a Langmuir–Hinshelwood model, in which the water and methanol adsorption on the catalyst surface are neglected.

Here is the partial pressure of each component in the reaction zone, calculated as the product of the total pressure and the molar fractions. The kinetics [23], adsorption [25,26] and equilibrium constants [26] are shown in Table A4.

Table A4.

Kinetic parameters of the catalytic hydrogenation of CO2.

Table A4.

Kinetic parameters of the catalytic hydrogenation of CO2.

| Kinetic Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

The energy balance in the reaction and the permeation zone are described in Equations (A7) and (A8), respectively. These balances assume heat exchange between the reaction and permeation zone, but the reactor is isolated from the external environment to evaluate the thermal effects of feeding cold sweep gas as single cooling strategy.

The global heat transfer coefficient (A9) describes three consecutive heat transfer phenomena: (1) the convection in the inner tube, (2) the conduction trough the membrane and (3) the convection in the outer tube.

The heat transfer coefficient in the permeation zone () and reaction zone () are calculated according to the correlations by Dittus–Boelter [27] and Li–Finlayson [28], respectively. The temperature at the membrane surface on the reaction () and permeation side () are determined by the steady state energy balance around the membrane (Equations (A10) and (A11))

The pressure drop in the reaction zone is described by the Ergun equation (Equation (A12)), while the pressure drop along the permeation zone is considered negligible.

The above set of equations was implemented in MATLAB R2019a and solved numerically with the ode15s function.

References

- European parlament and the Council of the European Union. Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/631 as regards strengthening the CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars and new light commercial vehicles in line with the Union’s increased climate ambition. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L 110, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, C.; Tsubaki, N. Recent advancements and perspectives of the CO2 hydrogenation reaction. Green Carbon 2023, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Guan, B.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, C.; Hu, X.; Zhao, S.; Dang, H.; et al. Perspectives and Outlook of E-fuels: Production, Cost Effectiveness, and Applications. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 7665–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.; Olivier, P.; Jegoux, M.; Makhloufi, C.; Gallucci, F. Membrane reactors technologies for e-fuel production & processing: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 112, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, J.; Wu, C.; Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Duan, X. The application prospect and challenge of the alternative methanol fuel in the internal combustion engine. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, V.; Buttler, A.; Hanel, A.; Spliethoff, H.; Fendt, S. Power-to-liquid via synthesis of methanol, DME or Fischer–Tropsch-fuels: A review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3207–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh Sarvestani, M.; Norouzi, O.; Di Maria, F.; Dutta, A. From catalyst development to reactor Design: A comprehensive review of methanol synthesis techniques. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 302, 118070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. A short review of catalysis for CO2 conversion. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, U.J.; Song, Y.; Zhong, Z. Improving the Cu/ZnO-Based Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation to Methanol, and the Use of Methanol As a Renewable Energy Storage Media. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portha, J.F.; Parkhomenko, K.; Kobl, K.; Roger, A.C.; Arab, S.; Commenge, J.M.; Falk, L. Kinetics of Methanol Synthesis from Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation over Copper-Zinc Oxide Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 13133–13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, F.; Tang, X.; Dai, S.; Pu, T.; Liu, X.; Tian, P.; Xuan, F.; Xu, Z.; Wachs, I.E.; et al. Induced activation of the commercial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst for the steam reforming of methanol. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, F.; Basile, A. A theoretical analysis of methanol synthesis from CO2 and H2 in a ceramic membrane reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 5050–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.G.; Hashim, N.A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Hartley, U.W.; Aroua, M.K.; Wohlrab, S. Overview of the latest progress and prospects in the catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide (CO2) to methanol in membrane reactors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 936–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, F.; Paturzo, L.; Basile, A. An experimental study of CO2 hydrogenation into methanol involving a zeolite membrane reactor. Chem. Eng. Process. 2004, 43, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbe, J.; Lasobras, J.; Francés, E.; Herguido, J.; Menéndez, M.; Kumakiri, I.; Kita, H. Preliminary study on the feasibility of using a zeolite A membrane in a membrane reactor for methanol production. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 200, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, F.; Heyen, G.; Kalitventzeff, B. Energy savings in methanol synthesis: Use of heat integration techniques and simulation tools. Comput. Chem. Eng. 1997, 21, S511–S516. [Google Scholar]

- Prodinger, S.; Derewinski, M.A. Recent Progress to Understand and Improve Zeolite Stability in the Aqueous Medium. Pet. Chem. 2020, 60, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, T.M.; Pollo, L.D.; Marcilio, N.R.; Tessaro, I.C. Insights into the development of carbon molecular sieve membranes from polymer blends for gas separation: A review. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 131, 205472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.F.; Goh, P.S.; Sanip, S.M.; Aziz, M. Transport and separation properties of carbon nanotube-mixed matrix membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 70, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa Tanco, M.A.; Pacheco Tanaka, D.A.; Rodrigues, S.C.; Texeira, M.; Mendes, A. Composite-alumina-carbon molecular sieve membranes prepared from novolac resin and boehmite. Part I: Preparation, characterization and gas permeation studies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 5653–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, S.; Endepoel, J.G.H.; Llosa-Tanco, M.A.; Pacheco-Tanaka, D.A.; Gallucci, F.; Neira d’Angelo, M.F. Vapor/gas separation through carbon molecular sieve membranes: Experimental and theoretical investigation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 11385–11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, S.; Llosa Tanco, M.A.; Pacheco Tanaka, D.A.; Neira d′Angelo, M.F.; Gallucci, F. Experimental investigation of a packed bed membrane reactor for the direct conversion of CO2 to dimethyl ether. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 72, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Teng, L.; Xiao, W. Simulation and experiment study of dimethyl ether synthesis from syngas in a fluidized-bed reactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 5455–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacinti Baschetti, M.; De Angelis, M.G. Vapour Permeation Modelling; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussche KMVanden Froment, G.F. A Steady-State Kinetic Model for Methanol Synthesis and the Water Gas Shift Reaction on a Commercial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 Catalyst. J. Catal. 1996, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.T.; Cao, F.H.; Liu, D.H.; Fang, D.Y. Thermodynamic analysis for synthesis of dimethyl ether and methanol from synthesis gas. J. East China Univ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 27, 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Taler, D.; Taler, J. Simple heat transfer correlations for turbulent tube flow. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, J.J. Heat Transfer in Packed Beds. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1965, 57, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.