Magnetic Polyoxometalate@Biochar Catalysts for Selective Acetalization of Glycerol into Fuel Additive

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

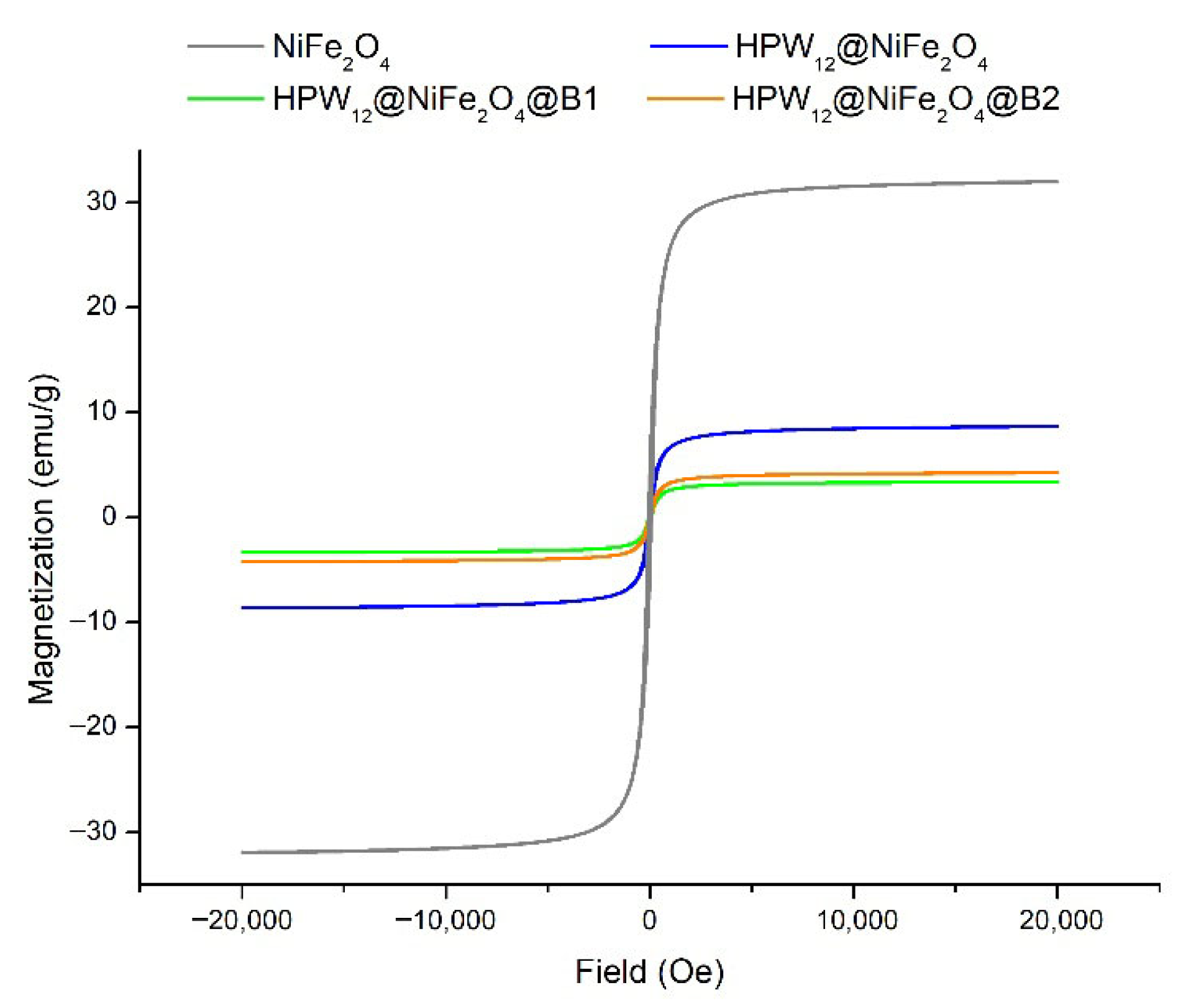

2.1. Characterization of Magnetic Biochar Catalysts

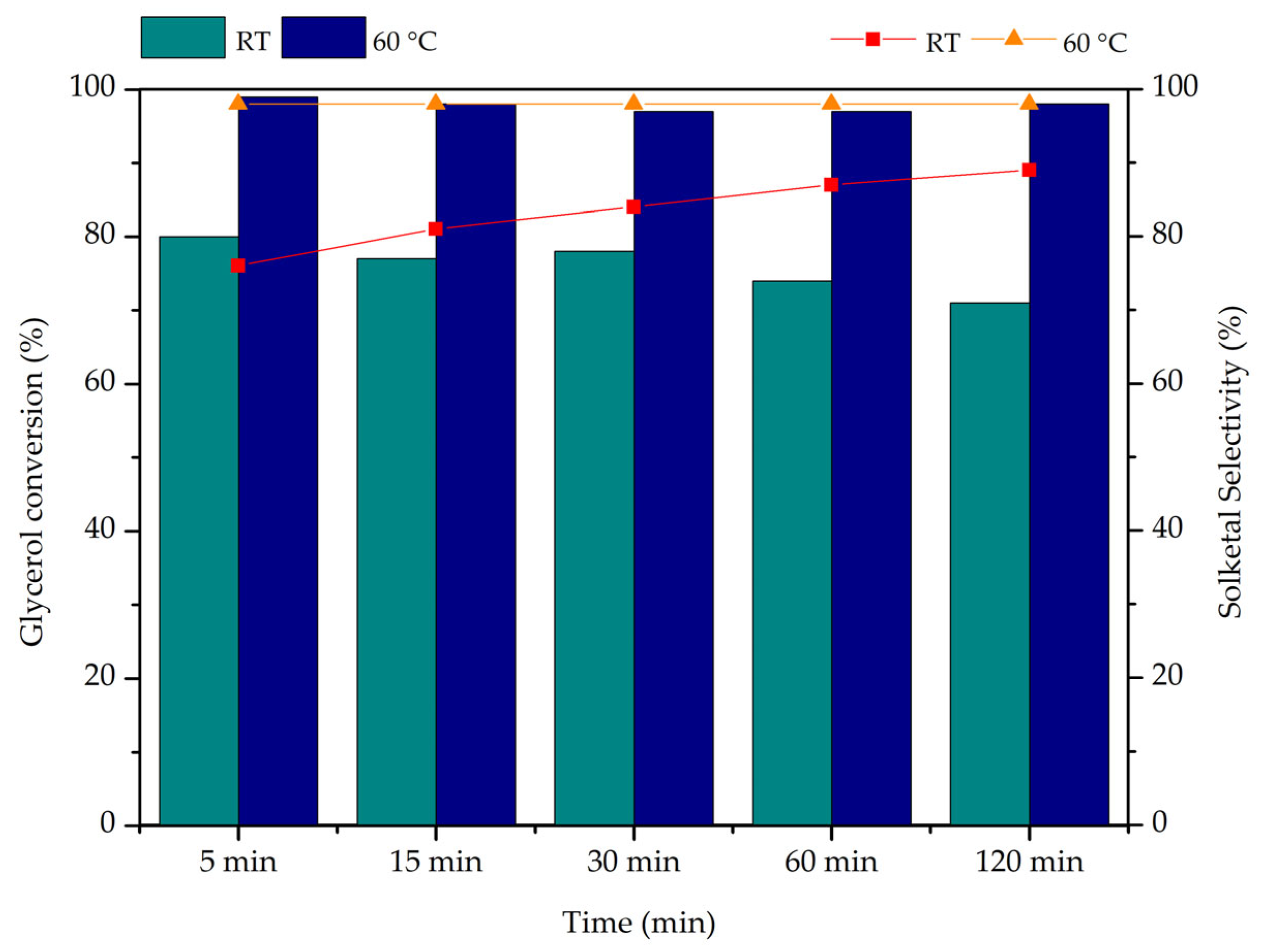

2.2. Acetalization Studies

2.3. Catalytic Performance of Biochar Composites

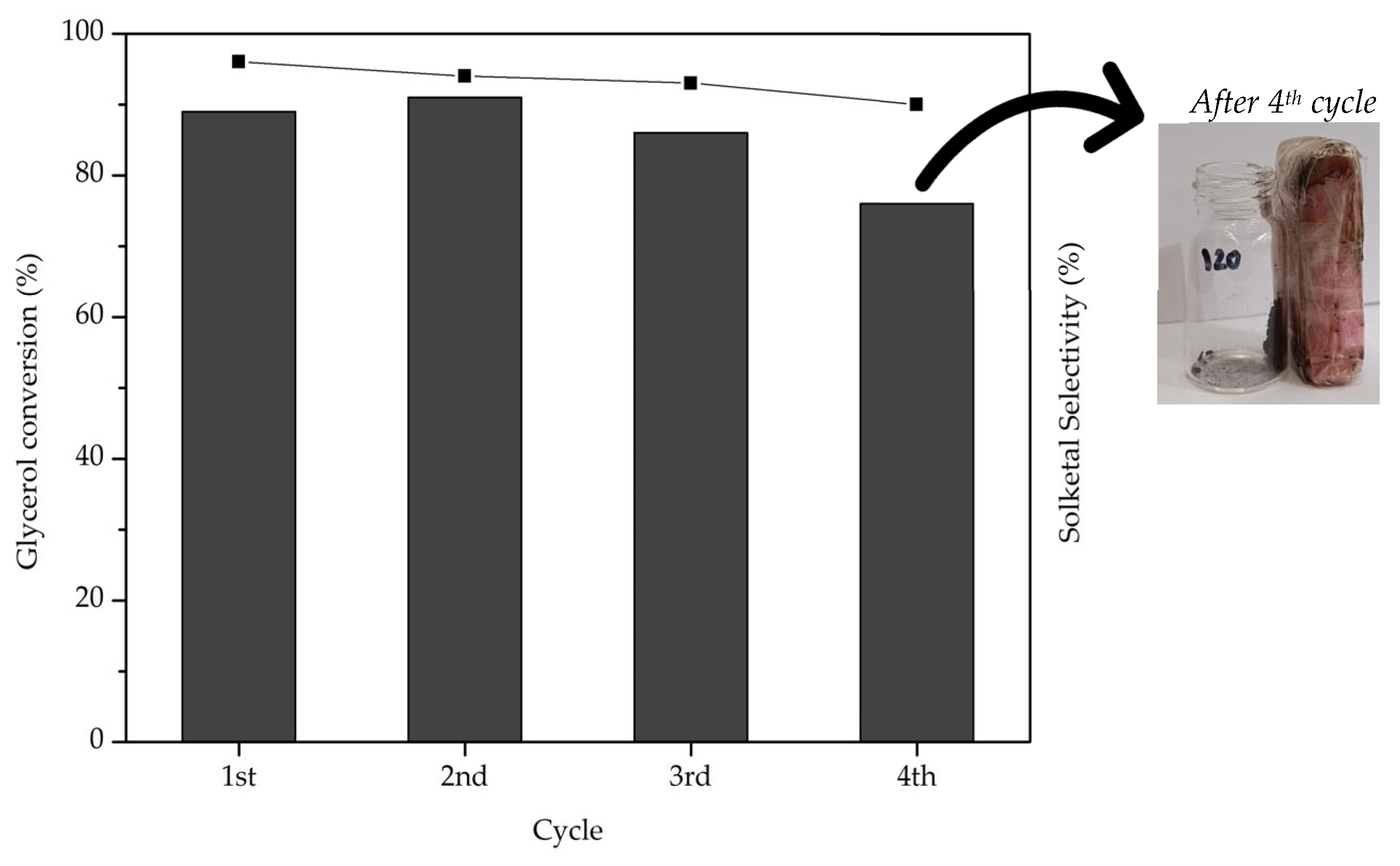

2.4. Catalyst Reutilization

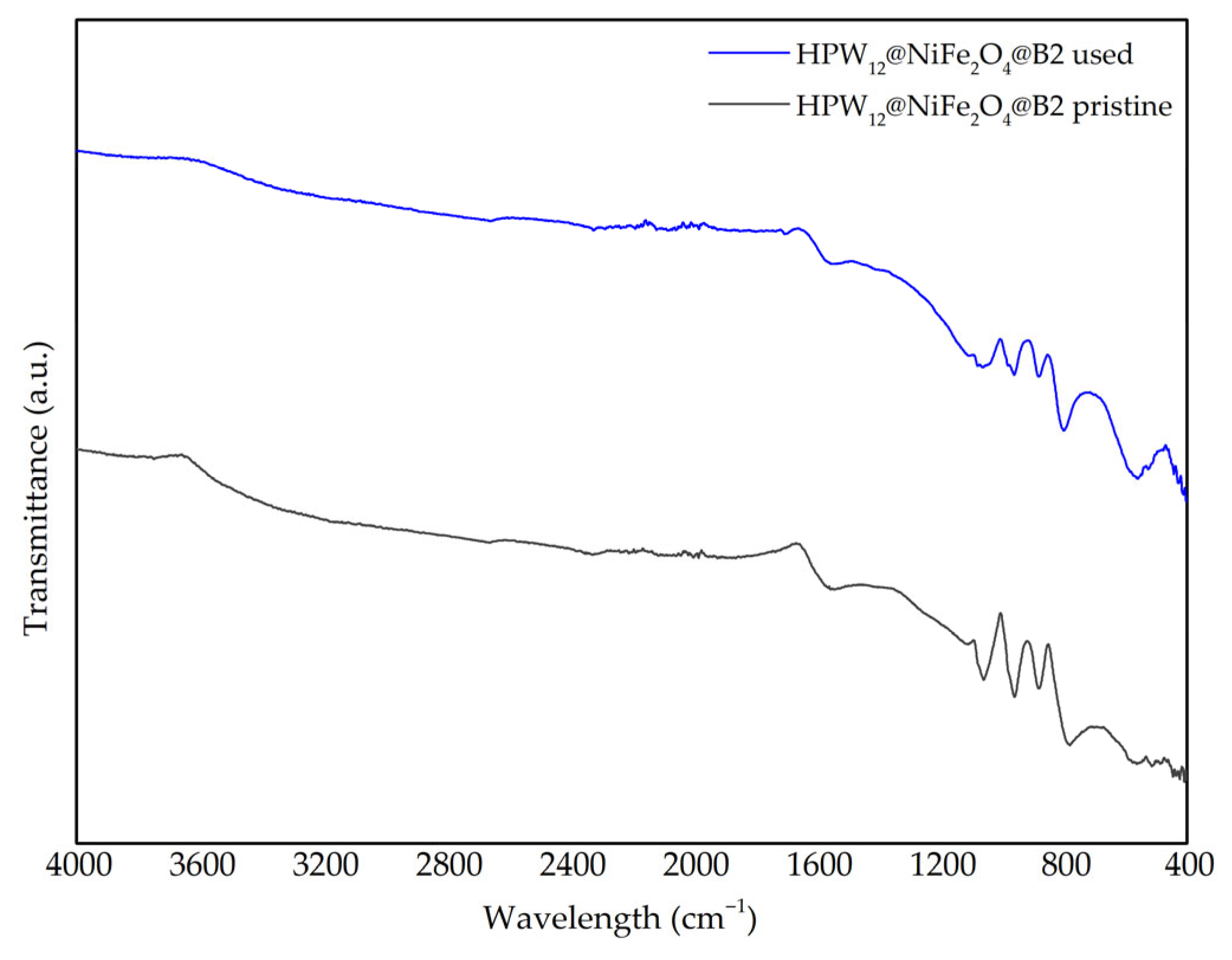

2.5. Catalyst Characterization After Use

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis and Preparation of Materials

3.1.1. NiFe2O4 by Co-Precipitation

3.1.2. HPW12@NiFe2O4 by Impregnation

3.1.3. Supports

3.1.4. Magnetic Composites

3.2. Catalytic Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corrêa, I.; Faria, R.P.V.; Rodrigues, A.E. Continuous Valorization of Glycerol into Solketal: Recent Advances on Catalysts, Processes, and Industrial Perspectives. Sustain. Chem. 2021, 2, 286–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asopa, R.P.; Bhoi, R.; Saharan, V.K. Valorization of glycerol into value-added products: A comprehensive review on biochemical route. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 20, 101290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, M.; Nogales-Delgado, S.; Montes, V.; Encinar, J.M. Recent Advances in Glycerol Catalytic Valorization: A Review. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Sakinah, A.M.M.; Zularisam, A.W. Opportunities of biodiesel industry waste conversion into value-added products. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 57, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estahbanati, M.R.K.; Feilizadeh, M.; Attar, F.; Iliuta, M.C. Current Developments and Future Trends in Photocatalytic Glycerol Valorization: Photocatalyst Development. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 22330–22352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.A.; Zhou, W.T.; Zhou, W.; Gong, Z.W. Co-valorization of crude glycerol and low-cost substrates via oleaginous yeasts to micro-biodiesel: Status and outlook. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 180, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, A.; Barrio, I.; Campoy, M.; Lázaro, J.; Navarrete, B. Oxygenated fuel additives from glycerol valorization. Main production pathways and effects on fuel properties and engine performance: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Qiang, Q.; Bai, L.; Su, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Acetalization strategy in biomass valorization: A review. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2024, 2, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, I.; Ayoub, M.; Abdullah, B.B.; Nazir, M.H.; Ameen, M.; Zulqarnain; Mohd Yusoff, M.H.; Inayat, A.; Danish, M. Production of Fuel Additive Solketal via Catalytic Conversion of Biodiesel-Derived Glycerol. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 20961–20978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.N.; Santos-Vieira, I.C.M.S.; Gomes, C.R.; Mirante, F.; Balula, S.S. Heteropolyacids@Silica Heterogeneous Catalysts to Produce Solketal from Glycerol Acetalization. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.A.; Selishcheva, S.A.; Yakovlev, V.A. Acetalization Catalysts for Synthesis of Valuable Oxygenated Fuel Additives from Glycerol. Catalysts 2018, 8, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, I.; Sahroni, I.; Fadillah, G.; Musawwa, M.M.; Mahlia, T.M.; Muraza, O. Glycerol to Solketal for Fuel Additive: Recent Progress in Heterogeneous Catalysts. Energies 2019, 12, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, M.N. Acid catalysis by heteropoly acids. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 256, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julião, D.; Mirante, F.; Balula, S.S. Easy and Fast Production of Solketal from Glycerol Acetalization via Heteropolyacids. Molecules 2022, 27, 6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.J.; Julio, A.A.; Dorigetto, F.C.S. Solvent-free heteropolyacid-catalyzed glycerol ketalization at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 44499–44506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulis, D.E. A Survey of Applications of Polyoxometalates. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikov, I.V. Catalysis by Heteropoly Acids and Multicomponent Polyoxometalates in Liquid-Phase Reactions. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.O.; Granadeiro, C.M.; Almeida, P.L.; Pires, J.; Capel-Sanchez, M.C.; Campos-Martin, J.M.; Gago, S.; de Castro, B.; Balula, S.S. Oxidative desulfurization strategies using Keggin-type polyoxometalate catalysts: Biphasic versus solvent-free systems. Catal. Today 2019, 333, 226–236. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Nohair, B.; Zhao, D.; Kaliaguine, S. Highly Efficient Glycerol Acetalization over Supported Heteropoly Acid Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 1918–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheiro, J. Acetalization of Glycerol with Citral over Heteropolyacids Immobilized on KIT-6. Catalysts 2022, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.D.; Infantes-Molina, A.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.M.; Romanelli, G.P.; Pizzio, L.R.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E. Heterogeneous acid catalysts prepared by immobilization of H3PW12O40 on silica through impregnation and inclusion, applied to the synthesis of 3H-1,5-benzodiazepines. Mol. Catal. 2020, 485, 110842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Hu, G.; Zhao, J. Heteropolyacid supported MOF fibers for oxidative desulfurization of fuel. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Xia, H.; Li, J.; Su, J.; Ge, F.; Yang, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, M. Heteropolyacids promoted MOF-derived high-performance Co(H4)@C-HPW0.25 catalysts for catalytic transfer hydrogenation of vanillin in mild condition. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheiro, J.E.; Vital, J.; Fonseca, I.M.; Ramos, A.M. Glycerol conversion into biofuel additives by acetalization with pentanal over heteropolyacids immobilized on zeolites. Catal. Today 2020, 346, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.Q.; Siddiqui, Z.N. Heteropoly Ionic Liquid Functionalized MOF-Fe: Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Application in Selective Acetalization of Glycerol to Solketal as a Fuel Additive at Room Temperature, Solvent-Free Conditions. Precis. Chem. 2023, 1, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, W.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, W. Conversion enhancement for acetalization using a catalytically active membrane in a pervaporation membrane reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.N.; Bruno, S.M.; Mirante, F.; Balula, S.S. Catalytic HPA@PVA membranes for clean fuel additive production. Mol. Catal. 2026, 589, 115569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Du, P.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Ma, J.-F. Assembly of polyoxometalate-thiacalix[4]arene-based inorganic–organic hybrids as efficient catalytic oxidation desulfurization catalysts. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Fonseca, I.M.; Ramos, A.M.; Vital, J.; Castanheiro, J.E. Acetylation of glycerol over heteropolyacids supported on activated carbon. Catal. Commun. 2011, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.J.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Teixeira, M.G. Iron (III) Silicotungstate: An Efficient and Recyclable Catalyst for Converting Glycerol to Solketal. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 9664–9673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.J.; Teixeira, M.G.; Chaves, D.M.; Siqueira, L. An efficient process to synthesize solketal from glycerol over tin (II) silicotungstate catalyst. Fuel 2020, 281, 118724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirante, F.; Leo, P.; Dias, C.N.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Balula, S.S. MOF-808 as an Efficient Catalyst for Valorization of Biodiesel Waste Production: Glycerol Acetalization. Materials 2023, 16, 7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aouissi, A.; Al-Othman, Z.A.; Al-Anezi, H. Reactivity of heteropolymolybdates and heteropolytungstates in the cationic polymerization of styrene. Molecules 2010, 15, 3319–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernaoui, C.R.; Bendraoua, A.; Zaoui, F.; Gallardo, J.J.; Navas, J.; Boudia, R.A.; Djediai, H.; Goual, N.e.H.; Adjdir, M. Synthesis and characterization of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles as reusable magnetic nanocatalyst for organic dyes catalytic reduction: Study of the counter anion effect. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 292, 126793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasumarthi, R.; Sawargaonkar, G.; Kale, S.; Kumar, N.V.; Choudhari, P.L.; Singh, R.; Davala, M.S.; Rani, C.S.; Mutnuri, S.; Jat, M.L. Innovative bio-pyrolytic method for efficient biochar production from maize and pigeonpea stalks and their characterization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakandawala, S.A.; Gunatilake, S.R.; Nardelli, M.B.; Gunawardena, S.H.; Liyanage, L.S.I. Modelling an amorphous biochar structure using classical molecular dynamics simulations. Pure Appl. Chem. 2025, 97, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różyło, K.; Jędruchniewicz, K.; Krasucka, P.; Biszczak, W.; Oleszczuk, P. Physicochemical Characteristics of Biochar from Waste Cricket Chitin (Acheta domesticus). Molecules 2022, 27, 8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, D.; Liu, Z.; Xu, D.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Tan, Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, R.; Su, C. Removal of polystyrene microplastic from aqueous solutions with London Plane bark biochar: Pyrolysis temperature, performance and mechanism. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 694, 134159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; De, M.; Tewari, H.S.; Ghoshal, S.K. Structural and magnetic properties of tailored NiFe2O4 nanostructures synthesized using auto-combustion method. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; Zakaria, M.B.; Kurz, H.; Tetzlaff, D.; Blösser, A.; Weiss, M.; Timm, J.; Weber, B.; Apfel, U.-P.; Marschall, R. Magnetic NiFe2O4 Nanoparticles Prepared via Non-Aqueous Microwave-Assisted Synthesis for Application in Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2021, 27, 16990–17001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.N.; Viana, A.M.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Balula, S.S. The Role of the Heterogeneous Catalyst to Produce Solketal from Biodiesel Waste: The Key to Achieve Efficiency. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Fonseca, I.M.; Ramos, A.M.; Vital, J.; Castanheiro, J.E. Valorisation of glycerol by condensation with acetone over silica-included heteropolyacids. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 98, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | AS (m2·g−1) a | Vp b (cm3·g−1) |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | 23.25 | 0.028 |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4@B1 | 2.24 | 0.00048 |

| HPW12@B1 | 0.46 | 0.00011 |

| B2 | 19.34 | 0.01017 |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4@B2 | 5.26 | 0.011 |

| HPW12@B2 | 6.40 | 0.00067 |

| Material | pH | Acidity (mmol H+/g) |

|---|---|---|

| HPW12 | 2.2 | 30.848 |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4 | 2.9 | 10.192 |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4@B1 | 3.5 | 5.536 |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4@B2 | 4.1 | 1.696 |

| Catalyst | Ratio Glycerol/Acetone | T (°C) | Time (h) | Conversion (%) | Selectivity to Solketal (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3PW12O40 | 1:15 | RT | 0.08 | 99 | 97 | [14] |

| H3PMo12O40 | 1:15 | RT | 0.08 | 91 | 94 | [14] |

| Cs2.5H0.5PW12O40 | 1:6 | RT | 1 | 94 | 98 | [19] |

| Cs2.5H0.5PW12O40@KIT-6 | 1:6 | RT | 0.25 | 95 | 98 | [19] |

| H3PW12@SiO2 | 1:6 | 70 | 4 | 97 | 97 | [42] |

| H3PW12@AptesSBA-15 | 1:15 | RT 60 | 0.08 | 83 91 | 97 97 | [10] |

| H3PMo12@AptesSBA-15 | 1:15 | RT 60 | 0.08 | 31 40 | 69 76 | [10] |

| H3PW12@PVA | 1:15 | 60 | 0.5 | 87 | 98 | [27] |

| H3PMo12@PVA | 1:15 | 60 | 2 | 95 | 97 | [27] |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4@B1 | 1:15 | 60 | 3 | 55 | 14 | This work |

| HPW12@NiFe2O4@B2 | 1:15 | 60 | 3 | 89 | 96 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pellaumail, Ó.; Dias, L.; Dias, C.N.; Bruno, S.M.; Silva, N.J.O.; Gholamahmadi, B.; Balula, S.S.; Mirante, F. Magnetic Polyoxometalate@Biochar Catalysts for Selective Acetalization of Glycerol into Fuel Additive. Catalysts 2026, 16, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010052

Pellaumail Ó, Dias L, Dias CN, Bruno SM, Silva NJO, Gholamahmadi B, Balula SS, Mirante F. Magnetic Polyoxometalate@Biochar Catalysts for Selective Acetalization of Glycerol into Fuel Additive. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010052

Chicago/Turabian StylePellaumail, Óscar, Luís Dias, Catarina N. Dias, Sofia M. Bruno, Nuno J. O. Silva, Behrouz Gholamahmadi, Salete S. Balula, and Fátima Mirante. 2026. "Magnetic Polyoxometalate@Biochar Catalysts for Selective Acetalization of Glycerol into Fuel Additive" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010052

APA StylePellaumail, Ó., Dias, L., Dias, C. N., Bruno, S. M., Silva, N. J. O., Gholamahmadi, B., Balula, S. S., & Mirante, F. (2026). Magnetic Polyoxometalate@Biochar Catalysts for Selective Acetalization of Glycerol into Fuel Additive. Catalysts, 16(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010052