Abstract

The ruthenium-catalysed silylative coupling (SC) reaction is a useful method for obtaining selectively functionalised organosilicon compounds, which have a wide range of applications in organometallic and organic chemistry. It is possible to prepare such compounds with norbornene matrices, which can be used for ring-opening metathesis polymerisation (ROMP) in the synthesis of linear-type polymers. Herein, we present a method for the synthesis of the aforementioned matrices by a condensation reaction between diol and vinylphenylboronic acids. Furthermore, these compounds were subsequently modified by SC reaction and polymerised by ROMP. To assess the possibility of using styryl-based silyl-derived monomers as building blocks in further organic transformations, the process of bromodesilylation was also investigated. We would also like to perform a comparative study on the selectivity of hydrosilylation and silylative coupling processes in the case of discovered materials.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, ring-opening metathesis polymerisation (ROMP) has been widely used for the preparation of complex macromolecular structures, such as well-defined polymers and block or graft polymers and copolymers with high molecular weights and low polydispersities exhibiting a unique wide range of properties [1,2,3]. This method was found to be a very useful and easily controllable tool that allows the preparation of linear, unsaturated polymeric materials by using highly strained cyclic monomers (e.g., butadiene, cyclopentene and cycloheptene) [4,5]. Currently, most works concern the use of sterically hindered norbornene (NBE) and its derivatives (27.2 kcal/mol) [6] due to energy released upon the process of ring opening, which simultaneously promotes polymerisation, resulting in creation of polymeric or copolymeric materials. These may contain diverse side-chain groups that might have almost unlimited applications, as it is possible to easily modify those constituents (groups) and introduce different elements into the polynorbornene matrix under various reaction conditions [7,8]. That way ROMP was used in the creation of conducting polymers [9], stereoregular fluoropolymers [10,11] and electroluminescent materials [12,13,14,15], among many others. The key feature of modern ROMP is the application of highly active and chemo-selective carbene metal-alkylidene catalysts bearing transition metal elements, and especially ruthenium ones, due to their high stability towards air and different functional groups [16,17,18]. When it comes to polymerisation of norbornene-derived monomers, it is vital to mention the necessity of the specific isomerism of its hanging side-chain groups. Previous studies on the reactivity of dicyclopentadiene have indicated that the endo-forms of these compounds are less reactive by an order of magnitude compared to the exo-forms. This reduced reactivity is due to steric interactions between the endo substituent of the incoming monomer and the substituents on the cyclopentane ring where the propagating centre is attached. Another factor contributing to this phenomenon is the formation of an intramolecular complex between the ruthenium centre and the neighbouring vinylene double bond [19].

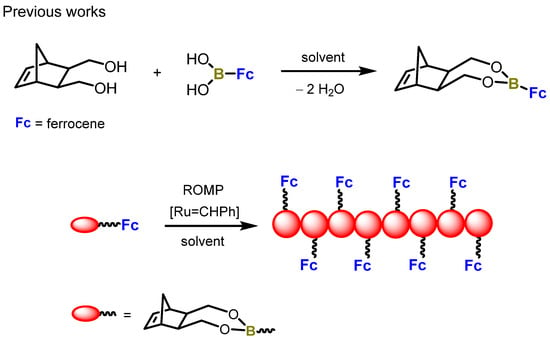

Our previous work focused on synthesis of a new norbornene-derived boronic ester that would be feasible for use in ring-opening metathesis polymerisation. This material was built of a metallocene moiety [20]. By performing a simple condensation reaction, we obtained a previously unreported material that was polymerised using the first generation of the Grubbs catalyst (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Previously published work.

Driven by our interest in developing efficient new methodologies for preparation of well-defined polymers, we have decided to further develop the idea of incorporating different functional groups into the polynorbornene-boronic ester matrix by introducing vinylsilanes into the side-chain groups, using the metal-catalysed silylative coupling (also called trans-silylation) process. It allows us to obtain stereodefined alkenylsilanes by combining functionalised olefins with vinyl-subsituted organosilicon compounds in the presence of transition metal complexes (Ru, Rh, Co and Ir) that are capable of generating in situ M-H and M-Si bonds, thus activating the C-H bond of olefins and C-Si bond of organosilicon compounds [21,22]. This type of reaction was developed in the 1990s [23] and has been consistently utilised in subsequent research focused on the development of β-functionalised vinyl-substituted organosilicon compounds. This includes the silylative coupling of N-vinylcarbazoles [24], substituted styrenes [25,26], N-vinylamides [27], polymers [28] or silsesquioxanes [29] with alkyl-, aryl- and alkoxy-substituted vinylsilanes and vinylsiloxanes. The selectivity of this process is influenced by the structure of the substrate and the catalyst employed. The most active and selective catalysts are ruthenium(II)-hydride complexes with phosphine ligands, such as [Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PPh3)3] and [Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PCy3)2]. This reaction is most effective and selective with functionalised olefins that contain aryl and nitrogen-containing groups, including substituted styrenes, N-vinylamides and N-vinylcarbazoles [30].

The formation of alkenylsilanes via the SC process is usually accompanied by subsequent desilylation reactions, allowing us to synthesise even more interesting functionalised unsaturated organic compounds that are usually considered to be building blocks in transition-metal-catalysed organic transformations [31]. Those transformations usually ensure the retention of geometry and consist of Pd-catalysed Hiyama coupling [24,32,33], Rh-catalysed Narasaka coupling [34] or a halodesilylation process using molecular halogens [35,36] or N-halosuccinimides [37,38,39,40] followed by other processes (e.g., Suzuki–Miyaura coupling and Sonogashira coupling) [41,42]. These modifications were found to be excellent synthetic pathways for obtaining conjugated π-electron compounds (e.g., stilbenes or aryl-substituted polyenes) with applications as fluorescent probes, electroluminescent devices and nonlinear optical materials [43,44,45] or in biomedicine, as they exhibited biological activity [46,47,48,49].

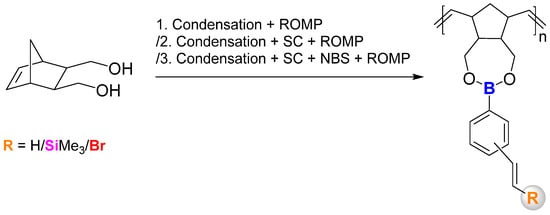

Herein, we would like to report the efficient and selective synthesis of norbornene-based boronic esters with styryl-derived functional groups supported by silylative coupling reactions with vinyltrimethylsilane, along with a halodesilylation process using N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) in order to obtain β-aryl vinyl bromides and their polymers. Compounds prepared this way could be further modified using other organic transformations. These monomers were subjected separately to ring-opening metathesis polymerisation during every step of the synthesis process using the first-generation Grubbs’ catalyst (G1) with full analyses of the obtained products. To the best of our knowledge, the combination of norbornene-based boronic esters with SC-based and desilylative bromination products has not yet been presented. The general idea of the study is visible in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

General overview of the study.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preliminary Studies

The main premise of the research was to obtain stable, well-defined polymeric materials after each modification process. In order to achieve it, monomers had to be designed in specific way, as exo-norbornene-derived materials tend to undergo ring-opening metathesis polymerisation processes with higher reactivity under ruthenium(II)-catalysed conditions, unlike its endo-isomer, due to steric hindrance interactions between the Ru=C alkylidene species of the G1 catalyst in the growing polymer chain and the incoming monomer [19]. That is why our study started with tests, allowing us to monitor the progress of each step of every reaction and oversee the formation of potential by-products.

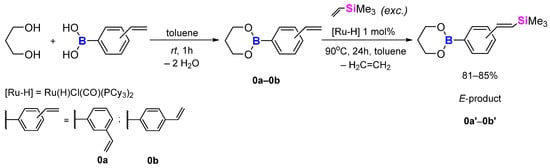

Knowing that the condensation reaction proceeds rapidly under rather mild conditions, we have decided to carry out a model reaction to see if the SC, bromodesilylation and hydrosilylation reactions were also possible. For that, 1,3-propanediol was mixed with 4-vinylphenylboronic acid or 3-vinylphenylboronic acid and dissolved in a non-polar medium (like toluene) at room temperature for 1 h. Substrates were mixed at a 1:1 molar ratio. The progress of the reaction was monitored by GC-MS analysis and FT-IR up to full conversion of the substrates.

The products were then isolated by drying the mixture with sodium sulphate (Na2SO4), filtering through the G4 funnel and evaporating the rest of the solvent, producing yellow (3-vinylphenyl) and pale yellow (4-vinylphenyl) liquids with 96%—0a, 97%—0b yields, respectively. Identification of products via NMR showed that the 13C NMR lacked one peak responsible for the B-C bond. Research on the topic revealed that this connection is not always detectable through carbon nuclear magnetic resonance, a fact supported by references in the literature [50,51,52,53]. This phenomenon was also observed in both monomers and polymers (see the ESI for results).

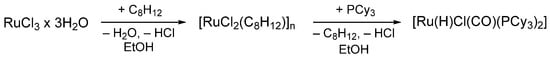

For the silylative coupling reaction, a ruthenium hydride catalyst is necessary. The reaction begins with the insertion of vinylsilane into the M-H bond, followed by β-Si transfer to the metal, resulting in the elimination of ethylene and formation of the M-Si species. This is followed by the insertion of an alkene and β-H transfer to the metal, leading to the elimination of the substituted vinylsilane [25,54]. The hydride catalyst [Ru-H], was obtained synthetically in a two-step reaction according to the following methods [55,56,57] (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Ruthenium hydride catalyst preparation.

We decided to perform the silylative coupling reaction with a volatile vinylsilane, which would be easy to remove from the resulting mixture. It also had the advantage of allowing a high excess of vinylsilane to be introduced without the risk of undesired by-products. For our studies we used vinyltrimethylsilane (ViSiMe3). The boronic esters were dissolved in toluene, and vinyltrimethylsilane was added in excess together with ruthenium hydride [Ru-H] catalyst at 90 °C for 24h. The molar ratio of substrates and catalyst was as follows: [boronic ester]:[ViSiMe3]:[Ru-H] = 1:6:0.01. Afterwards, the mixture was purified using a chromatography column with DCM as eluent (Scheme 4). The products obtained were a thick brown liquid (0b’—85% yield) and brown crystals (0a’—81% yield) (Scheme 4) and showed good solubility in common organic solvents—CH2Cl2, CHCl3, C6H5CH3 and CH3CN. The compounds were analysed with a GC-MS spectrometer and NMR spectroscopy (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 11B NMR and 29Si NMR). The analysis of the 1H NMR spectrum of both model compounds revealed the presence of two separate doublets with a coupling constant equal to JH-H = 18.4–19.2 Hz, indicating formation of an E-isomer within the double -Ar-CH=CH-SiMe3 bond.

Scheme 4.

Condensation and silylative coupling of model reactions.

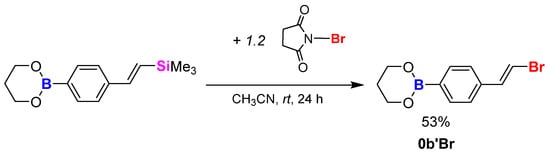

The final modification involved the desilylative bromination procedure, performed according to references in the literature [38,40]. For that, Si-modified boronic ester bearing the 4-styryltrimethylsilyl group 0b’ was mixed with an excess of N-bromosuccinimide in acetonitrile as a solvent at room temperature for 24 h (Scheme 5). The aforementioned substrates were mixed in a molar ratio of [boronic ester]:[NBS] = 1:1.2. The conversion of the substrate was monitored by GC-MS analysis. After full conversion, the solvent was concentrated and the mixture was extracted using hexane, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered through the G4 funnel and once again concentrated. The resulting product formed translucent crystals along with a colourless liquid with 53% yield and showed good solubility in the organic halogen solvents CH2Cl2 and CHCl3. The final compound (0b’Br) was analysed using a GC-MS spectrometer and NMR spectroscopy (1H NMR, 13C NMR and 11B NMR).

Scheme 5.

Bromodesilylation process of model compound.

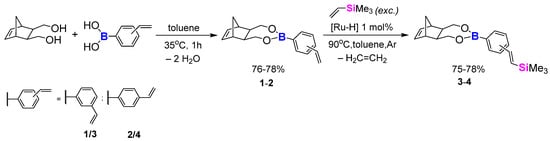

2.2. Monomer Synthesis

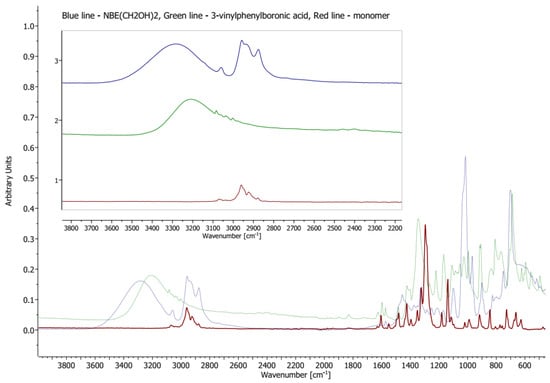

The positive results on model reactions inspired us to develop the idea of incorporating ROMP, SC and bromodesilylation procedures altogether with 5-norbornene-2-exo-3-exo-dimethanol as the diol substrate (NBE-diol). The reaction between NBE-diol and boronic acid (3-vinylphenylboronic acid or 4-vinylphenylboronic acid) in toluene at 35 °C for 1 h, monitored by GC-MS and FT-IR, provided white solids (1—76% yield and 2—78% yield, respectively) in both cases (Scheme 6). The use of FT-IR (Figure 1) allowed us to observe the disappearance of the wide bands from 3100 cm−1 to 3600 cm−1, which are attributed to hydroxyl groups. Additionally formation of another C-O stretching band is visible at 1140 cm−1, confirming the formation of an ether -H2C-O-B- system bond. The isolated products were also characterised by NMR (1H NMR, 13C NMR and 11B NMR) spectroscopy. Additional tests have been performed to assess the stability of –CH2-O-B bonds in boronic esters. Both 1 and 2 were subjected to bases (KOH and K2CO3) in moderately polar (THF) and polar (MeOH) media at room temperature and 40 °C for 24 h. GC-MS after that time showed pure designated boronic esters, and no by-products (e.g., boroxines) were observed.

Scheme 6.

Condensation and silylative coupling of the NBE-based compounds.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of reaction progress; synthesis of compound 1 (red line), 3-vinylphenylboronic acid (green line) and NBE-(CH2OH)2 (blue line) were measured at 25 °C as a solid state.

The second step, the silylative coupling process, similarly to model reactions 0a’ and 0b’, involved boronic esters 1 and 2 being dissolved in toluene and vinyltrimethylsilane along with the catalyst [Ru-H], which was added in the molar ratio [boronic ester]:[ViSiMe3]:[Ru-H] = 1:3:0.01. The progress of the reaction was observed using GC-MS analysis. It was found that the silylative coupling did not occur fully, as after approximately 10 h, unmodified boronic esters were still visible on the GC-MS spectra, and a slightly bigger excess was essential. In the case of 3, the final ratio reached 1:4.08:0.01, while for 4, it reached 1:3.3:0.01. In both cases, the resulting mixture was filtered, concentrated and purified using a chromatography column with hexane/ethyl acetate (3:1) as the eluent. The resulting products formed beige—3 (75% yield)—and white powders—4 (78% yield). Both products contained traces of by-product isomer E-/Z-2-trimethylsilylstyrene, which was later removed during the purification of polymers (P2, P3 and P4). Products were identified using GC-MS and NMR spectroscopy (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 11B NMR, 29Si NMR). Similarly to 0a’ and 0b’, the 1H NMR analyses of products 3 and 4 once again showed separate doublets with JH-H = 19.2 Hz, which once again confirmed the formation of the E-isomer.

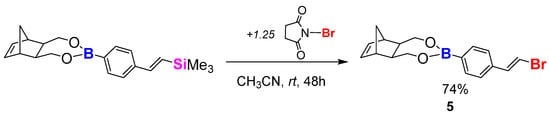

For the bromodesilylation (Scheme 7), compound 4 was mixed with an excess of NBS in an acetronitrile and toluene mixture at room temperature. Toluene was required, as substrate 4 was found to be only slightly soluble in CH3CN. The molar ratio of the substrates was as follows: [boronic ester]:[NBS] = 1:1.25. It has been observed that the reaction required more time in comparison to the model reactions; however, after 48 h, full conversion was visible using GC-MS analysis. Isolation was similar to the model reactions: concentration, extraction with hexane, drying with Na2SO4, filtration with a G4 funnel, evaporation of solvent. The final product (5) formed a white powder (74% yield). The product was analysed using GC-MS and NMR spectroscopy (1H NMR, 13C NMR and 11B NMR). All of the monomers (1–5) showed good solubility in common organic halogen solvents—however, for CH2Cl2 and CHCl3, contrary to 0a’ and 0b’, monomers 3 and 4 were found to be insoluble in CH3CN.

Scheme 7.

Desilylative bromination process of NBE-based compound.

2.3. Polymerisation Studies

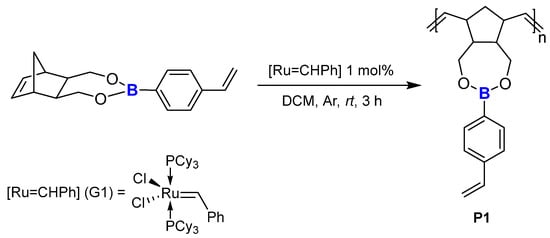

Having successfully obtained monomers containing vinylphenyl substituents (1, 2) we were curious to see what would be the result of performing a ROMP reaction on this setup. According to the literature [58], there was a high risk of an intermolecular reaction between the reactive ‘hanging’ vinyl group and the ruthenium alkylidene centre in the Grubbs’ catalyst, thus blocking the polymerisation process and providing a homometathesis product. We found it interesting to see if it was necessary to modify the substituent by an SC reaction. The test involved mixing NBE-4-styrylboronic ester with G1 catalyst at a [boronic ester]:[G1] = 1:0.01 ratio, using DCM as the solvent, at room temperature for 3 h. The isolation included concentration of the mixture and successive precipitations in a non-polar medium, which was n-hexane, in order to eliminate traces of the inactive form of the catalyst in the polymer. The resulting product P1, after drying using a vacuum-system line, was in the form of a white powder (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8.

Polymerisation of monomer 2.

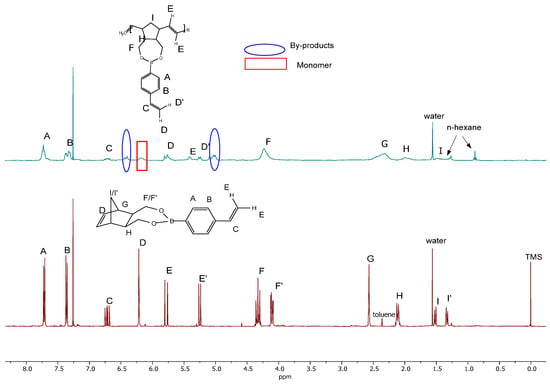

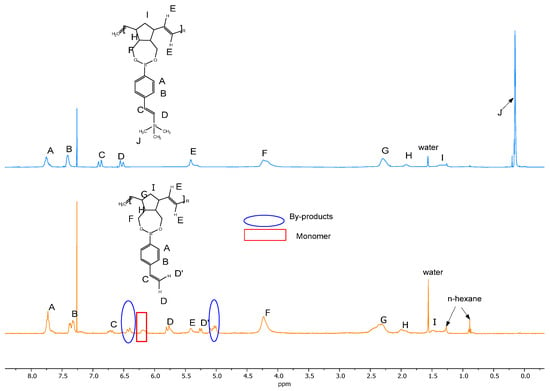

The progress of the polymerisation was observed using 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 2). Generally, the progress rate of the consumption of the NBE monomer is identified through the analysis of its vinylic region. ‘Sharp’ resonances at around 6.30–6.00 ppm of the monomer vinylene group (-HC=CH-norbornene) fade, while ‘broad’ resonances coming from the inner vinylene groups of the polymer (-HC=CH-cyclopentane) at 5.50–5.00 ppm increase in intensity.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum comparison of NBE-4-styrylboronic ester (2) and polymer (P1)—polymer (cyan line), monomer (brown line) in CDCl3 at 25 °C.

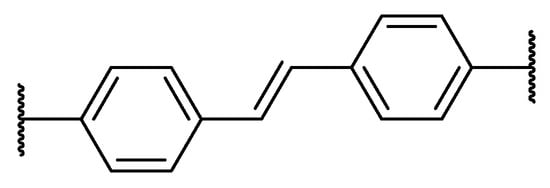

It can be seen that, in the case of P1, the conversion was not complete, as the peak at 6.22 ppm did not fade completely and the polymer was not the only product—additional peaks appeared at around 6.4 and 5.1 ppm, probably due to the formation of stilbene-derived cross-linked by-products (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Possible stilbene-derived product.

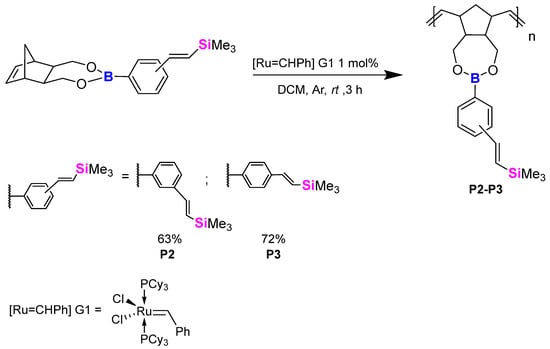

While we found that there were difficulties in obtaining pure polymer, we continued our research and performed ROMP on silyl-based compounds prepared via a silylative coupling process using similar conditions and isolation processes (Scheme 10). A resulting beige powder was obtained in both cases: P2, 63% yield, and P3, 72% yield. Lower yields were the result of the polymer being slightly soluble in n-hexane as the mixture, upon precipitation, also changed colours to beige. Products were analysed using NMR spectroscopy (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 11B NMR and 29Si NMR), gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and thermogravimetry analysis (TGA/DTG).

Scheme 10.

ROMP of Si-substituted styryl groups containing boronic esters.

The comparison between the styryl-based monomer and the Si-modified one upon the silylative coupling process clearly shows full conversion of the monomer into the polymer (6.22 ppm peak no longer observed) along with no additional by-product formation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of P1 (orange line) and P3 (blue line) polymerisation results on 1H NMR in CDCl3 at 25 °C.

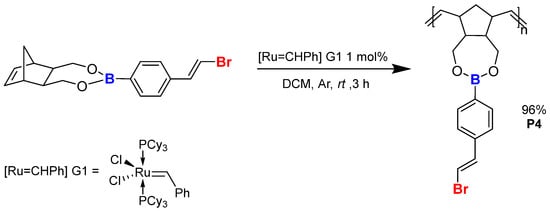

Eventually, the polymerisation of 5, boronic ester, after the bromodesilylation (Scheme 11) process provided material P4 as a white powder (96% yield). The process was conducted and isolated under similar conditions as P1–P3. All of the polymers (P1–P4) showed good solubility in common organic halogen solvents (DCM and chloroform).

Scheme 11.

ROMP of compound 5 after the desilylative bromination process.

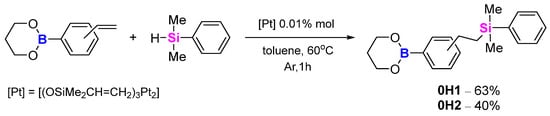

2.4. Hydrosilylation Tests

In addition, we also performed hydrosilylation on the obtained vinylphenylboronic esters, seeking another method of modifying materials. In these cases we used dimethylphenylsilanes, and the reaction mixture was heated in toluene at 60 °C for 1 h, after which GC-MS indicated full conversion of the starting material (Scheme 12). The purification step required a chromatography column with DCM as the eluent. The resulting products were colourless liquids (4-vinylphenyl (0H1)—63% yield—and 3-vinylphenyl (0H2)—40% yield) and were analysed by both the GC-MS and NMR (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 11B NMR and 29Si NMR) methods.

Scheme 12.

Hydrosilylation of model compounds 0H1, 0H2.

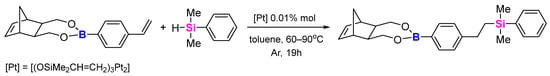

Similarly, we conducted the hydrosilylation process on styryl-boronic esters, and, although the conditions were quite similar, the process did not proceed in the same way. The GC-MS spectra after 19 h showed the presence of unmodified boronic ester (substrate), numerous by-products (including diphenyltetramethylsiloxane) and two isomers of the product. When more silane was added to the mixture, not only were more by-products formed, but a third isomer of the product was also visible (Scheme 13). It is possible that by adding an excess of dimethylphenylsilane, the hydrosilylation occurred inside the norbornene ring with a vinylene group instead of a vinylphenyl one in the substituent group. However, we did not observe the product of the double hydrosilylation process. It was impossible for us to separate the resulting mixture of products. It might be an interesting subject to develop in the future.

Scheme 13.

Hydrosilylation of monomer 2.

2.5. GPC Measurements

Gel permeation chromatography measurements in THF provided good molecular weight values of the polymers P2: Mn = 8346 g/mol, Mw = 13,960 g/mol, ĐM = 1.67. The second polymer P3 in THF showed the following results: Mn = 11,495 g/mol, Mw = 19,482 g/mol and ĐM = 1.70. The measurements for the third polymer, P4, in DCM provided the following results: Mn = 8685 g/mol, Mw = 15,451 g/mol and ĐM = 1.78. In each case similar scatterings of number average molecular weight (Mn) were visible, 8346–11,495 g/mol, along with narrow mass scatterings across the ĐM index (Mw/Mn), 1.67–1.78. For the figures regarding the GPC studies, see the ESI. The above-described data is also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

GPC results—mass parameters.

2.6. TGA Measurements

TGA results showed a similar thermal stability of both polymers with good heat-resistant properties. P2 and P3 showed a 5% mass loss at a range of 346–350 °C and a 10% mass loss from 394 to 402 °C. For P2 the biggest mass loss was observed for the following range, 268.4–529.2 °C, with a maximum at 422.4 °C with 71% mass loss, while for P3, it was shown at 273.1–534.0 °C, with a maximum at 418.7 °C with 72% mass loss. The P4 polymer, however, showed five distinguishable steps of thermal decomposition upon TGA that occurred at lower temperatures. First of all, the 5% mass loss was observed at 248.2 °C and the 10% mass loss at 270.2 °C. The biggest mass losses were observed from: 201.1 to 357.1 °C (31%), 357.1 to 495.0 °C (29%) and 495.0 to 736.3 °C (18%). Additionally, the fifth step of thermal decomposition for P4 was observed in the range of 736.3–867.5 °C, with a 4% weight loss. When it comes to the thermal stability of prepared materials, the positioning of the styryl group did not affect its heat resistance in noticeable way. These experiments confirm that these materials might find an application as building blocks in metal-catalysed transformations, as they exhibit elevated thermal stability due to their boronic ester part. This is consistent with other works in which boron is added into the structures of other compounds to enhance their thermal stability [59,60,61]. The differences in thermal stability between P2–P3 and P4 may be attributed to the lack of silicon atoms present in polymer P4 (lower thermal stability) and the large size of bromine atoms, which provided additional strain in the polymer structure and may have resulted in dehalogenation of bromine atoms from the matrix. The results are shown in Table 2 and ESI.

Table 2.

TGA results.

The thermal decomposition of organic compounds in an oxygen-free environment is a complex process that may proceed through various pathways. As a result, a range of pyrolysis products may be created, including gaseous species, semi-volatile compounds and carbons. It should be emphasised that thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) involves the pyrolytic degradation of polymeric materials under a dry, inert nitrogen atmosphere; therefore, the oxidation of double bonds within the polynorbornene matrix can be excluded from consideration. In evaluating the probable decomposition mechanism, the bond dissociation energies of organoboron, organosilicon and analogous organic compounds were considered. The reported bond energies were approximately 520–540 kJ·mol−1 for boronic ester B–O bonds, 460–480 kJ·mol−1 for B–C bonds, 350–400 kJ·mol−1 for O–C bonds and around 320 kJ·mol−1 for Si–C bonds in organic systems. For carbon–carbon and carbon–hydrogen linkages, the bond energies were as follows: C–C single bonds—350–410 kJ·mol−1; C=C double bonds—610–630 kJ·mol−1 and C–H bonds, around 413 kJ·mol−1 [62]. Detailed analysis of these energetic parameters suggests that structural degradation proceeds in two main stages: initially, the cleavage of C–C and ester O–C bonds, followed by the subsequent fragmentation of the polymeric backbone. The decomposition pathway of the boronic ester moiety, specifically the –C–O–B– linkage, should be addressed separately. This process is likely to involve dehydration and condensation reactions, leading to the formation of boron anhydrides and boroxine, accompanied by the development of a protective char layer. Char formation is typically associated with the cleavage of B–O–C bonds, yielding boron oxide species such as B2O3. Furthermore, the presence of silicon within the polymer structure may promote the formation of silicon dioxide (SiO2) or products of –Si(CH3)3 group decomposition (radical formation, isomerisations and H2 eliminations) [63].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The chemicals were obtained from following sources: toluene (99.8%), methylene chloride (DCM, 99.8%), n-hexane (99.5%), acetonitrile (99.5%), ethanol (99.0%) and diethyl ether (97.5%) were purchased from Chempur and P.O.Ch. Gliwice, 5-norbornene-2-exo-3-exo-dimethanol (>97%), 1,3-propanediol (>99%), 4-vinylphenylboronic acid (95%), 3-vinylphenylboronic acid (95%), NBS (>99%), vinyltrimethylsilane (98%), ruthenium(III) chloride hydrate, 1,5-cyclooctadiene (>99%), tricyclohexylphosphine (>99%), deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) (>99.8%), deuterated benzene (C6D6) (>99.9%) and Grubbs catalyst 1st generation C43H72Cl2P2Ru—[RuCl2(=CHPh)(PCy3)2] from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), ethyl vinyl ether (99%) from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) from EuroChem (Zug, Switzerland) and Celite®545 and silica gel—60 (SiO2) from Fluka (Seelze, Germany). Acquired solvents—toluene, methylene chloride, n-hexane and acetonitrile—were stored over molecular sieves of type A4. Methylene chloride used in polymerisation was kept in Schlenk’s system in an inert atmosphere over molecular sieves of type A4. The ruthenium hydride catalyst [Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PCy3)2] used for silylative coupling was prepared according to references from the literature [55,56,57].

3.2. Techniques

3.2.1. GC-MS

Mass spectra (GC-MS) of monomers were obtained on Varian 3300 instrument (Varian, Inc. 2700 Mitchell Drive Walnut Creek, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with capillary column type DB-1 ResteckTM (Agilent Technologies/Glastron Inc., Vineland, NJ, USA), which was connected to a Finnigan MAT 800 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) with an ion trap detector. Spectra were registered by using the ITD Finnigan MAT programme.

3.2.2. FT-IR

Infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed on a NICOLETTM iSTM50FT-IR spectrometer made by Thermo ScientificTM (Madison, WI, USA) with addition of iSTM50ATR, in a range between 4000 cm−1 and 400 cm−1. For each spectrum 16 scans were registered.

3.2.3. NMR

1H NMR (400 MHz), 13C NMR (105 MHz) and 29Si NMR (99 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Mercury plus 400MHz spectrometer (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) and Bruker Avance 600 MHz (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). 11B NMR spectra were acquired with a Bruker Avance 600 MHz spectrometer. In each method, CDCl3 solution was used as a residue solvent. Chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm) with reference to the residue solvent used (CDCl3) (1H δ H = 7.26 ppm, 13C δ C = 77.36 ppm).

3.2.4. GPC

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analyses of P2 and P3 were performed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity system equipped (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) with a Phenogel 10 um Linear(2) 300 × 7.8 mm column and RI detector. The samples were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF). Conditions of measurements: mobile phase—tetrahydrofuran (THF); flow rate (THF) = 1 mL/min; column temperature = 35 °C; RI detector temperature = 35 °C and analysis time = 15 min. The molecular weights of the analysed compounds and their mass scatterings were determined with reference to linear poly(styrene) standards with masses in the range of 1000–3,500,000. Data was processed using Agilent GPC/SEC software—1.2.3182.29519.

GPC analysis for P4 was obtained using a Viscotek GPC max equipped (Viscotek/Malvern Instruments/Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK) with a refractive index detector Viscotek VE 3580 and Shodex KF–802.5 (8 mm × 300 mm, 6 µm) column. The sample was dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM). Conditions of measurements: mobile phase—dichloromethane (DCM); flow rate (DCM) = 1 mL/min; column temperature = 35 °C and RI detector temperature = 35 °C. The molecular weights of the analysed compounds and their mass scatterings were determined with reference to linear poly(styrene) standards with masses in the range of 5800–11,500.

3.2.5. TGA

Thermal stability was investigated by the thermogravimetric analyzer TGA Q50 V20.10 Build 36 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Samples of about 1.00 to 3.50 mg were heated in platinum pans at the rate of 10 °C/min from 25 °C to 900 °C and 1000 °C under nitrogen atmosphere (90 mL/min).

3.3. Synthesis and Characterisation of Obtained Compounds

3.3.1. Synthesis Procedure of Models 0a and 0b via Condensation Reaction

A two-neck round bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirring bar was charged with 0.3 g (3.942 mmol) of 1,3-propanediol, 20 mL of toluene and 0.607 g (4.1 mmol) of either 3-vinylphenyl boronic acid or 4-vinylphenylboronic acid. The slight excess of the added boronic acid was due to purity differences between substrates. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature, during which the boronic acid dissolved and droplets of water were visible on the flask’s wall. The progress of the reaction was monitored by FT-IR and GC-MS analyses. For isolation, anhydrous sodium sulphate (Na2SO4) was inserted in order to remove any trace of water in the setup. After 3 h, the mixture was filtered through a G4 funnel, and the organic solvent was removed by rotary evaporator and vacuum line to obtain the desired products, which were yellow 0a (0.711 g, 3.782 mmol, 96% yield) and pale yellow 0b (0.741 g, 3.941 mmol, 97% yield) liquids.

Analytical data for 0a: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.83 (s, 1H, (A)), 7.7 (dt, 1H, (B), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 7.2 Hz); 7.49 (dt, 1H, (C), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 7.6 Hz); 7.32 (t, 1H, (D), JH-H = 7.6 Hz); 6.74 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E), JH-H = 10.8 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 5.79 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E-position) (F), JH-H = 0.8 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 5.23 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (Z-position) (F’), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 10.8 Hz); 4.18 (t, 4H,-CH2- (G), JH-H = 5.2 Hz); 2.06 (q, 2H, -CH2- (H), JH-H = 5.6 Hz); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 137.2; 136.8; 133.3; 131.8; 128.4; 127.9; 113.6; 62.1; 27.6; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.0; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 188.1(M+•)(100), 129.9(11), 116.8(6).

Analytical data for 0b: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.74 (dt, 2H, (A), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 8.4 Hz); 7.40 (dt, 2H, (B), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.0 Hz); 6.74 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (C), JH-H = 10.8 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 5.80 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E-position) (D), JH-H = 0.8 Hz, 17.2 Hz); 5.28 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (Z-position) (D’), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 10.8 Hz); 4.17 (t, 4H, -CH2- (E), JH-H = 5.6 Hz); 2.36 (s, toluene); 2.06 (q, 2H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 5.6 Hz); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 139.7; 137.2; 134.0; 125.5; 114.5; 62.1; 27.6; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.0; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 188.0(M+•)(100), 130.0(34), 77.0(11).

3.3.2. Ruthenium Hydride Catalyst [Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PCy3)2] Preparation

A Schlenk flask equipped with a condenser, ‘bubbler’ and magnetic stirrer was charged with 2.4 g (9.2 mmol) of ruthenium(III) chloride trihydrate and 50 mL of dried, deoxygenated ethanol. Next, 2.49 g (23.0 mmol) of freshly distilled 1,5-dicyclooctadiene was added dropwise into the reaction mixture, which was heated to a boiling temperature and stirred for 48 h while constantly being held under an inert atmosphere (Ar). During cooling, a precipitate was formed, which was filtered and washed with ethanol (4 × 20 mL), water (3 × 10 mL) and diethyl ether (2 × 10 mL) and dried under reduced pressure, providing 2.45 g of [RuCl2(C8H12)]n (95% yield). Next, 1.0 g (3.57 mmol) of the obtained ruthenium complex was placed in a Schlenk flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, and 2.05 g (7.32 mmol) of tricyclohexylphopshine was added along with 40 mL of dried, deoxygenated ethanol under an inert atmosphere. The reaction mixture was tightly sealed and stirred for 48 h at the boiling point. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature. During this process a crystalline powder was formed. The excess of ethanol and dicyclooctadiene was decanted and the precipitate was dried under reduced pressure. The obtained complex was washed with ethanol and cold diethyl ether, after which the residue was dried under reduced pressure, which provided 2.54 g (Y = 85% yield calculated per metal atom) of the desired product.

Analytical data for catalyst: 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 2.57–2.32 (m, P(C6H11)3), 2.02–1.72, 1.54–1.26 (m, P(C6H11)3), −24.16 (t, Ru-H); 13C NMR (105 MHz, C6D6): 202.1; 35.0; 30.5; 28.4; 27.2; 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D6): 44.9.

3.3.3. Synthesis Procedure of Models 0a’ and 0b’ via Silylative Coupling

A Schlenk flask was charged with 0.14 g (0.745 mmol) of either 0a or 0b. Using the vacuum line, the setup was filled with argon. Next, 1.5 mL of toluene was added into the setup (C = 0.5 mol/dm3) along with 0.457 g (662 μL, 4.56 mmol) of vinyltrimethylsilane and 5.41 mg of ruthenium hydride catalyst—[Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PCy3)2]. The mixture was then stirred and heated at 90 °C for 24 h, after which the brown solution was filtered through a syringe with blotting paper and then concentrated using a vacuum line. The product was purified by column chromatography using dichloromethane as an eluent, obtaining brown crystals 0a’ (0.156 g, 0.601 mmol, 81% yield) and thick brown liquid 0b’ (0.171 g, 6.571 mmol, 85% yield).

Analytical data for 0a’: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.86 (s, 1H (A)), 7.66 (dt, 1H, (B), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 7.2 Hz); 7.50 (dt, 1H, (C), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 7.6 Hz); 7.32 (t, 1H, (D) JH-H = 7.2 Hz); 6.90 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (E), JH-H = 18.4 Hz); 6.52 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (F), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 4.18 (t, 4H, -CH2- (G), JH-H = 5.6 Hz); 2.07 (p, 2H, -CH2- (H), JH-H = 5.2 Hz); 0.15 (s, 9H, -CH3 (I)); 0.07 (s, silicone grease); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.0; 137.6; 137.2; 133.4; 131.9; 128.2; 128.7; 128.4; 127.9; 113.6; 62.1; 27.6; 2.1; −1.1; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.0; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ −6.3; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 259.1(M+•)(100), 245.1(66), 143.0(15).

Analytical data for 0b’: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.73 (dd, 2H, (A), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 6.0 Hz); 7.42 (dd, 2H, (B), JH-H = 0.8 Hz, 8.4 Hz); 6.89 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (C), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 6.54 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 4.17 (t, 4H, -CH2- (E), JH-H = 5.6 Hz); 2.06 (p, 2H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 5.2 Hz); 0.16 (s, 9H, -CH3 (G)); 0.07 (s, silicone grease); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 143.9; 140.4; 134.0; 130.4; 125.7; 62.1; 27.6; −1.1; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.0; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ −6.2; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 258.9(M+•)(100), 245.1(29), 174.8(11), 144.8(16), 73.0(5).

3.3.4. Synthesis Procedure of Model 0b’Br via Bromodesilylation

A two-neck glass reactor under argon equipped with a magnetic stirring bar was charged with 0.03 g (0.116 mmol) of 0b’, 1.16 mL of acetronitrile and a 20% molar excess of NBS (0.024 g, 0.139 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. The mixture was then concentrated using vacuum line, extracted using hexane, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered through G4 funnel and, eventually, the solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator and vacuum line. The final product, 0b’Br, formed translucent crystals along with a colourless liquid (0.016 g, 0.0607 mmol, 53% yield).

Analytical data for 0b’Br: 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.72 (dd, 2H, (A), JH-H = 1.8 Hz, 6.6 Hz); 7.27 (dd, 2H, (B), JH-H = 0.6 Hz, 8.4 Hz); 7.10 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (C), JH-H = 13.8 Hz); 6.82 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 13.8 Hz); 4.16 (t, 4H, -CH2- (E), JH-H = 5.4 Hz); 2.06 (p, 2H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 5.4 Hz); 0.07 (s, silicone grease); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 137.9; 137.5; 134.3; 125.4; 62.1; 27.6; 1.2 (silicone grease); 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.0; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 266.0(M+•)(100), 210.0(32), 129.0(67), 115.0(17), 102.0(18), 77.1(52).

3.3.5. Synthesis Procedure of Monomers 1 and 2 via Condensation Reaction

Monomers 1 and 2 were obtained similarly to models (0a and 0b) by using 0.3 g (1.946 mmol) of 5-norbornene-2-exo-3-exo-dimethanol, 20 mL of toluene and 0.294 g (1.984 mmol) of either 3-vinylphenyl boronic acid or 4-vinylphenylboronic acid. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at 35 °C. After work-up (according to models), the products were obtained as white solids—1 (0.394 g, 1.479 mmol, 76% yield) and 2 (0.404 g, 1.518 mmol, 78% yield).

Analytical data for 1: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.80 (br s, 1H, (A)), 7.65 (dt, 1H, (B), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 7.2 Hz); 7.45 (dt, 1H, (C), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.0 Hz); 7.39 (t, 1H, (D), JH-H = 7.2 Hz); 6.73 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E), JH-H = 10.8 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 6.22 (t, 2H, -CH=CH- (F), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 5.77 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E-position) (G), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 5.21 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (Z-position) (G’), JH-H = 0.8 Hz, 10.8 Hz); 4.34 (t, 2H, -CH2- (H), JH-H = 12.0 Hz); 4.12 (dd, 2H, -CH2- (H’), JH-H = 4.0 Hz, 11.6 Hz); 2.57 (p, 2H, -CH- (I), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 2.15–2.08 (m, 2H, -CH- (J)); 1.56 (s, water); 1.52 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (K), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.8 Hz); 1.34 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (K’), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.8 Hz); 0.005 (s, TMS); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 137.4; 137.3; 136.7; 133.7; 132.2; 128.1; 127.8; 113.4; 67.3; 45.1; 43.4; 42.9; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.7; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 265.9(M+•)(100), 200.2(80), 199.2(30), 185.0(49), 91.0(17.5), 66.0(30.2).

Analytical data for 2: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.72 (dd, 2H, (A), JH-H = 2.0 Hz, 6.4 Hz); 7.36 (dd, 2H, (B), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 6.4 Hz); 6.72 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (C), JH-H = 10.8 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 6.22 (t, 2H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 5.78 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E-position) (E), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 17.6 Hz); 5.25 (dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (Z-position) (E’), JH-H = 0.8 Hz, 10.8 Hz); 4.33 (t, 2H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 12.0 Hz); 4.11 (dd, 2H, -CH2- (F’), JH-H = 4.0 Hz, 11.6 Hz); 2.57 (p, 2H, -CH- (G), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 2.36 (s, toluene); 2.14–2.08 (m, 2H, -CH- (H)); 1.56 (s, water); 1.52 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (I), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 9.2 Hz); 1.33 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (I’), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 9.2 Hz); 0.005 (s, TMS); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 139.4; 137.4; 137.2; 134.4; 125.4; 114.3; 67.3; 45.0; 43.4; 42.9; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.6; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 265.9(M+•)(61), 200.0(100), 185.0(39), 130.1(15), 91.1(15), 77.0(13), 66.0(32).

3.3.6. Synthesis Procedure of Monomer 3 via Silylative Coupling

Monomer 3 was obtained using the same synthesis procedure as models (0a’ or 0b’) by using 0.1 g (0.376 mmol) of 1, 0.5 mL of toluene (C = 0.75 mol/dm3), 0.157 g (228 μL, 1.563 mmol) of vinyltrimethylsilane and 2.7 mg of ruthenium hydride catalyst—[Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PCy3)2]. The crude product was purified by column chromatography, using hexane:ethyl acetate (3:1) mixture as the eluent, obtaining a beige powder, 3 (0.095 g, 0.282 mmol, 75% yield).

Analytical data for 3: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.83 (br, s, 1H, (A)), 7.64 (dt, 1H (B), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 7.2 Hz); 7.47 (dt, 1H, (C), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.0 Hz); 7.28 (t, 1H, (D), JH-H = 7.6 Hz); 6.89 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (E), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 6.49 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (F), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 6.22 (t, 2H, -CH=CH- (G), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 4.34 (t, 2H, -CH2- (H), JH-H = 11.6 Hz); 4.12 (dd, 2H, -CH2- (H’), JH-H = 4.0 Hz, 12.0 Hz); 2.57 (p, 2H, -CH- (I), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 2.15–2.08 (m, 2H, -CH- (J)); 1.56 (s, water); 1.52 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (K), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.8 Hz); 1.34 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (K’), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 9.2 Hz); 0.14 (s, 9H, -CH3 (L)); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.2; 137.5; 137.4; 133.9; 132.4; 128.9; 128.3; 127.8; 67.3; 45.1; 43.4; 42.9; −1.1; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.7; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ 7.4; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 338.1 (M+•)(14.7), 251.2(5), 221.3(6), 143.2(6), 119.3(100), 118.3(27), 117.3(16.5), 91.0(9).

3.3.7. Synthesis Procedure of Monomer 4 via Silylative Coupling

Monomer 4 was obtained using the same synthesis procedure as models (0a’ or 0b’) by using 0.1 g (0.376 mmol) of 2, 0.5 mL of toluene (C = 0.75 mol/dm3), 0.127 g (184 μL, 1.265 mmol) of vinyltrimethylsilane and 2.7 mg of ruthenium hydride catalyst—[Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PCy3)2]. The product was purified by column chromatography, using hexane:ethyl acetate (3:1) mixture as the eluent, obtaining a white powder, 4 (0.099 g, 0.293 mmol, 78% yield).

Analytical data for 4: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.73 (d, 2H, (A), JH-H = 8.0 Hz); 7.40 (d, 2H, (B), JH-H = 8.4 Hz); 6.89 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (C), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 6.53 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 6.22 (t, 2H, -CH=CH- (E), JH-H = 2.0 Hz); 4.33 (t, 2H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 12.0 Hz); 4.11 (dd, 2H, -CH2- (F’), JH-H = 4.0 Hz, 11.6 Hz); 2.57 (p, 2H, -CH- (G), JH-H = 2.0 Hz); 2.15–2.09 (m, 2H, -CH- (H)); 1.52 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (I), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 9.2 Hz); 1.34 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (I’), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.8 Hz); 0.16 (s, 9H, -CH3 (J)); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.0; 137.4; 136.1; 134.5; 130.1; 126.1; 125.6; 67.3; 45.1; 43.4; 42.9; −1.1; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.6; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ 7.4; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 337.9 (M+•)(100), 323.2(41), 257.2(24), 218.2(22), 145.2(47), 119.2(74), 91.2(95), 66.0(35).

3.3.8. Synthesis Procedure of Monomer 5 via Bromodesilylation

A two-neck glass reactor under argon equipped with a magnetic stirring bar was charged with 0.03 g (0.089 mmol) of 4, 1.1 mL of acetonitrile (CH3CN), 0.8 mL of toluene and a 20% molar excess of NBS (0.0189 g, 0.106 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 48 h at room temperature. The work-up was performed similarly to model 0b’Br. The final product, 5, formed a white powder (0.0226 g, 0.066 mmol, 74% yield).

Analytical data for 5: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.71 (dd, 2H, (A), JH-H = 2.0 Hz, 6.4 Hz); 7.24 (dd, 2H, (B), JH-H = 1.2 Hz, 6.2 Hz); 7.09 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (C), JH-H = 14.0 Hz); 6.80 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 14.0 Hz); 6.21 (t, 2H, -CH=CH- (E), JH-H = 2.0 Hz); 4.32 (t, 2H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 12.0 Hz); 4.10 (dd, 2H, -CH2- (F’), JH-H = 4.0 Hz, 11.6 Hz); 2.57 (p, 2H, -CH- (G), JH-H = 1.6 Hz); 2.14–2.07 (m, 2H, -CH- (H)); 1.51 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (I), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 8.8 Hz); 1.33 (dt, 1H, -CH2- (I’), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 9.2 Hz); 1.26 (br s, grease); 0.86 (m, grease); 0.07 (s, silicon grease); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 137.44; 137.41; 137.2; 134.5; 106.9; 67.1; 44.9; 43.2; 42.7; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.7; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 344.1(M+•)(19), 280.0(59), 273.0(65), 208.0(18), 129.1(22), 91.1(22), 77.1(37), 66.1(100).

3.3.9. Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerisation of Monomers 2, 3, 4

A two-neck glass reactor under argon equipped with a magnetic stirring bar was loaded with 0.045 g of monomer 2, 3 or 4, followed by addition of 4 mL of methylene chloride (DCM) and 0.001 g (67.3 μL; C = 0.02 mol/dm3) of Grubbs catalyst [Ru=CHPh]. The molar ratio between the reactants was as follows: [olefin]:[Ru=CHPh] = 100:1. The solutions were stirred for 3 h at room temperature, after which an excess (≈150 μL) of ethyl vinyl ether was added in order to terminate the reaction. The obtained mixtures were then concentrated and polymeric materials were precipitated by adding the rest of the solution dropwise to n-hexane. In the next step, the hexane was decanted and the polymers were dissolved once again in DCM and then precipitated. This step was repeated to remove any residual catalyst that may have remained in the mixtures. Finally, polymers were dried under vacuum. Polymer P1 was obtained as a white powder. NMR analysis showed the formation of the product; however, the monomer and by-product were still present. The rest of the NMR spectroscopic analyses (P2, P3) confirmed the full conversion of the monomers along with the formation of the expected polymers. Both the P2 and P3 polymers were beige powders, with P2 being 0.028 g (63% yield) and P3 being 0.035 g (78% yield).

Analytical data for P1: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.73 (t, 2H, (A), JH-H = 7.2 Hz); 7.34 (dd, 2H, (B), JH-H = 6.8 Hz, 21.2 Hz); 6.72 (br dd, 1H, -CH=CH2 (C), JH-H = 11.6 Hz, 18.4 Hz); 6.42 (br d, by-product); 6.19 (br s, -CH=CH- vinylene—monomer); 5.79 (d, 1H, -CH=CH2 (E-position) (D), JH-H = 17.6 Hz); 5.41 (br s, 2H, -CH=CH- (E)); 5.25 (d, 1H, -CH=CH2 (Z-position) (D’), 10.4 Hz); 5.05 (br dd, by-product); 4.23 (br s, 4H, -CH2- (F)); 2.31 (br s, 2H, -CH- (G)); 1.99 (br s, 2H, -CH- (H)); 1.56 (s, water); 1.48 (br s, 2H, -CH2- (I)); 1.27 (m, n-hexane); 0.89 (t, n-hexane).

Analytical data for P2: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.75 (br s, 1H, (A)); 7.68 (br s, 1H, (B)); 7.49 (br s, 1H, (C)); 7.31 (br s, 1H, (D)); 6.91 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (E), JH-H = 19.2 Hz); 6.50 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (F), JH-H = 18.8 Hz); 5.42 (br s, 2H, -CH=CH- (G)); 4.25 (br s, 4H, -CH2- (H)); 2.31 (br s, 2H, -CH- (I)); 1.92 (br s, 2H, -CH- (J)); 1.56 (s, water); 1.38 (br s, 2H, -CH2- (K)); 0.89 (t, n-hexane); 0.14 (s, 9H, -CH3 (L)); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.2; 137.5; 134.0; 133.9; 133.1; 132.5; 129.1; 128.4; 127.9; 64.5; 48.9; 45.2; 40.7; −1.0; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): 25.1; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ 7.4.

Analytical data for P3: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.76 (br s, 2H, (A)); 7.41 (br s, 2H, (B)); 6.89 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (C), JH-H = 19.6 Hz); 6.53 (d, 1H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 18.4 Hz); 5.41 (br s, 2H, -CH=CH- (E)); 4.23 (br s, 4H, -CH2 (F)); 2.30 (br s, 2H, -CH- (G)); 1.92 (br s, 2H, -CH- (H)); 1.57 (s, water); 1.35 (br s, 2H, -CH2- (I)); 0.15 (s, 9H, -CH3 (J)); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 143.9; 140.3; 134.6; 133.4; 133.1; 130.3; 125.6; 64.5; 48.8; 45.2; 40.7; −1.1; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.2; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ 7.4.

3.3.10. Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerisation of Monomer 5

ROMP of monomer 5 was conducted similarly to monomers 3 and 4, using 0.02 g of monomer 5, 1.7 mL of methylene chloride (DCM) and 0.00047 g (28.7 μL; C = 0.02 mol/dm3) of Grubbs catalyst [Ru=CHPh]. The molar ratio between the reactants was as follows: [olefin]:[Ru=CHPh] = 100:1. After a similar work-up, the polymer was produced as a white powder with P4 being 0.019 g (96% yield).

Analytical data for P4: 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.75 (br s, 2H, (A)); 7.27 (br s, 2H, (B)); 7.10 (br d, 1H, -CH=CH- (C), JH-H = 12.6 Hz); 6.82 (br d, 1H, -CH=CH- (D), JH-H = 13.8 Hz); 5.41 (br s, 2H, -CH=CH- (E)); 4.22 (br s, 4H, -CH2- (F)); 2.29 (br s, 2H, -CH- (G)); 1.91 (br s, 2H, -CH- (H)); 1.34 (br s, 2H, -CH2- (I)); 1.26 (br s, grease); 0.89 (m, grease); 0.08 (s, silicon grease); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 137.8; 137.5; 134.8; 133.1; 125.8; 125.4; 107.3; 64.5; 48.8; 45.1; 40.7; 31.7 (n-hexane); 29.8 (grease); 22.8 (n-hexane); 14.3 (n-hexane); 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 29.2.

3.3.11. Hydrosilylation Procedure for Tests 0H1 and 0H2

0H1: To a 5 mL round-bottom flask, 0b’ (51 mg, 0.274 mmol) was added along with 0.275 mL of toluene (C = 1 mol/dm3), 38 mg of dimethylphenylsilane (43 μL, 0.279 mmol) and 0.0000053 g of Karstedt catalyst (0.27 μL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at 60 °C. After 1 h GC-MS analysis showed full consumption of the starting material. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered through a fibreglass filter. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by chromatography column using DCM as the eluent to produce 56 mg (0.173 mmol, 63% yield) of product obtained as a colourless liquid, 0H1.

Analytical data for 0H1: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.68 (dd, 2H, (A), JH-H = 1.6 Hz, 6.4 Hz); 7.57–7.53 (m, 2H, o-C6H5 (B)); 7.40–7.36 (m, 3H, m-p-C6H5 (C, D)); 7.17 (dd, 2H, (E), JH-H = 2.0 Hz, 6.4 Hz); 4.16 (t, 4H, -CH2- (F), JH-H = 5.2 Hz); 2.67–2.63 (m, 2H, -CH2- (G)); 2.05 (p, 2H, -CH2- (H), JH-H = 5.2 Hz); 1.16–1.11 (m, 2H, -CH2- (I)); 0.29 (s, 6H, -CH3 (J)); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 147.8; 139.2; 133.9; 133.7; 129.0; 127.9; 127.3; 62.1; 30.3; 27.6; 17.7; −2.9; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 27.1; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ −2.9; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 323.0(M+•)(7), 309.1(86), 247.3(100), 237.8(29), 144.7(7), 131.2(10).

0H2: A similar procedure was utilised in the case of 0H2, using 60 mg of 0a’ (0.318 mmol), 0.318 mL of toluene (C = 1 mol/dm3), 44.2 mg of dimethylphenylsilane (50 μL, 0.324 mmol) and 0.0000062 g of Karstedt catalyst (0.31 μL). The product (41 mg, 0.126 mmol, 40% yield) was obtained as a colourless liquid, 0H2.

Analytical data for 0H2: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.61–7.54 (m, 4H, (A, B, C)); 7.39–7.36 (m, 3H, m-p-C6H5 (D, E)); 7.28–7.23 (m, 2H, (F, G)); 4.17 (t, 4H, -CH2- (H), JH-H = 5.6 Hz); 2.67–2.63 (m, 2H, -CH2- (I)); 2.06 (p, 2H, -CH2- (J), JH-H = 5.2 Hz); 1.17–1.12 (m, 2H, -CH2- (K)); 0.30 (s, 6H, -CH3 (L)); 13C NMR (105 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.2; 139.3; 133.7; 133.1; 131.1; 130.3; 129.0; 127.9; 127.7; 62.1; 30.1; 27.6; 18.0; −3.0; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.9; 29Si NMR (99 MHz): δ −3.0; MS (EI) [m/z (relat. int. %)]: 323.2(M+•)(10), 309.2(90), 247.5(100), 241.5(44), 144.1(11), 131.0(8).

3.4. General Information on Safe Work Practices and the Schlenk Technique

These compounds must be handled using proper needle and syringe techniques with a vacuum Schlenk line. Contact with skin and the respiratory system should be strictly avoided. All manipulations with these compounds were performed following the reported safety procedures [64].

4. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this report presents the first example of combining different organometallic and organic transformations, including ring-opening metathesis polymerisation, silylative coupling and the desilylative bromination technique. The use of a simple and easily controllable condensation reaction between diol and styryl-based boronic acids allowed for synthesis of a new class of boronic esters bearing reactive vinyl group. While ROMP of unmodified styryl-containing boronic esters proved to have difficulties regarding the conversion and eventual purity of the material, they were found to be prone to further modifications.

The possibility of binding different silyl-based groups through the use of the silylative coupling process allowed for incorporation of various Si-containing functional groups. What is more, the bromodesilylation procedure was also investigated, resulting in the formation of a compound ready to be used as a building block in organic chemistry. All of those modifications, supported by ROMP, will allow us, in the future, to obtain materials with interesting properties.

In our work, we presented an original, efficient, fully controlled and selective method of obtaining two new NBE-styryl-Si-based and one NBE-styryl-Br-containing linear polymer. Both the silyl-based materials P2 and P3 showed good thermal stabilities and narrow ĐM (Mw/Mn) mass spreads from 1.67 to 1.70. Polymer P4, containing hanging bromine atoms, showed more complex step thermal decomposition, which may be attributed to steric hindrance and debromination process occurring during the measurement. Similarly to previous polymers, it also showed narrow ĐM (Mw/Mn) mass spreads equal to 1.78.

At the moment we are also investigating the possibility of using elements other than boron, such as silicon and phosphorus, that in the future may further broaden the list of new materials. We are also researching the possibility of coordination of organic donor species possessing nitrogen atoms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16010045/s1: ESI consists of NMR spectra (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 11B NMR, 29Si NMR) of models 0a, 0b, 0a’, 0b’, 0b’Br, 0H1, 0H2, monomers 1–5, polymers P1–P4, in Figures S1–S54; GPC analysis for polymers P2–P4 in Figures S55–S57; TGA curves for polymers P2–P4 in Figures S58–S60. All SI data is collected in PDFs.

Author Contributions

M.M.: supervision of the research, conceptualization of paper, visualisation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, design of the experiments, data analysis; J.G.: main investigation and data analysis, preparation of models, monomers and polymers—catalytic screening, writing—original draft, design of the experiments, methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (Project UMO-2024/53/B/ST5/03556).

Data Availability Statement

All experimental data are included in ESI and are available to reviewers upon request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the EU, IDUB competition No. 058 (058/06/POB3/0031) and IDUB competition No. 115 (115/13/UAM/0037), Mariusz Majchrzak — Faculty subsidy for maintaining and developing research potential and special thanks to UWr. hab. Izabela Czeluśniak from University of Wrocław, Faculty of Chemistry for the consultation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ROMP | Ring-opening metathesis polymerisation |

| NBE | Norbornene |

| SC | Silylative coupling = silane coupling with olefins |

| NBS | N-bromosuccinimide |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography—mass spectrometry |

| ĐM | Polydispersity index |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

References

- Schrock, R.R. Living Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization Catalyzed by Well-Characterized Transition-Metal Alkylidene Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feast, W.J.; Gibson, V.C.; Johnson, A.F.; Khosravi, E.; Mohsin, M.A. Tailored Copolymers via Coupled Anionic and Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Synthesis and Polymerization of Bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2,3-trans-bis(Polystyrylcarboxylate)s. Polymer 1994, 35, 3542–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Abdellatif, M.M. Precise Synthesis of Polymers Containing Functional End Groups by Living Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP): Efficient Tools for Synthesis of Block/Graft Copolymers. Polymer 2010, 51, 1861–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejl, A.; Scherman, O.A.; Grubbs, R.H. Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Functionalized Low-Strain Monomers with Ruthenium-Based Catalysts. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7214–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, F.; Pascual, S.; Montembault, V.; Fontaine, L. 1,4-Polybutadienes with Pendant Hydroxyl Functionalities by ROMP: Synthetic and Mechanistic Insights. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 3843–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleyer, P.V.R.; Wiliiams, J.E.; Blanchard, K.R. The Evaluation of Strain in Hydrocarbons. The Strain in Adamantane and Its Origin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthasupa, S.; Sanda, F.; Masuda, T. ROMP of Norbornene Monomers Carrying Nonprotected Amino Groups with Ruthenium Catalyst. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barther, D.; Moatsou, D. Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Norbornene-Based Monomers Obtained via the Passerini Three Component Reaction. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 202100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, L.Y.; Schrock, R.R.; Stieglitz, S.G.; Crowe, W.E. Preparation of Discrete Polyenes and Norbornene-Polyene Block Copolymers Using Mo(CH-t-Bu)(NAr)(O-t-Bu)2 as the Initiator. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 3489–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, G.C.; Khosravi, E.; Schrock, R.R.; Feast, W.J.; Gibson, V.C.; O’Regan, M.B.; Thomas, J.K.; Davis, W.M. Living Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization Of 2,3-Difunctionalized Norbornadienes by Mo(CH-t-Bu)(N-2,6-C6H3-/-Pr2)(0-t-Bu)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8378–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, M.M.; Gerber, L.C.H.; Debelouchina, G.T.; Schrock, R.R. Z-Selective and Syndioselective Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP) Initiated by Monoaryloxidepyrrolide (MAP) Catalysts. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7515–7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochkarev, L.N.; Begantsova, Y.E.; Iĺichev, V.A.; Abakumov, G.A. Electroluminescent Platinum-Containing Polymers Based on Functionalized Norbornenes. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2014, 63, 2534–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Bazan, C.G. Paracyclophene Route to Poly(p-Phenylenevinylene). J. Am. Chem. Soc. Am. 1994, 116, 9379–9380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, A.M.; Yu, C.Y.; Horie, M.; Turner, M.L. MEH-PPV by Microwave Assisted Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerisation. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2676–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidster, B.J.; Behrendt, J.M.; Turner, M.L. Monotelechelic Poly(p-Phenylenevinylene)s by Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerisation. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11867–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, E.L.; Nguyen, S.B.T.; Grubbs, R.H. Well-Defined Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts: Mechanism and Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 3887–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchay, F.C.; Sworen, J.C.; Wagener, K.B. Metathesis Activity and Stability of New Generation Ruthenium Polymerization Catalysts. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 8231–8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Hejl, A.; Wenzel, A.G.; Funk, T.W.; Grubbs, R.H. A Standard System of Characterization for Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. Organometallics 2006, 25, 5740–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, J.D.; Moore, J.S. ROMP Reactivity of Endo- and Exo-Dicyclopentadiene. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 7878–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarek, J.; Majchrzak, M.; Wałęsa-Chorab, M.; Kubicki, M. Synthesis and Electrochemical Properties of Well-defined Norbornene-B-Ferrocene-dioxaborolane Hybrid Polymeric Material. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 21368–21378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, B.N. Synthesis of Some Carbon-Functional Organosilicon Compounds. J. Organomet. Chem. 1979, 164, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniec, B. Catalysis by Transition Metal Complexes of Alkene Silylation—Recent Progress and Mechanistic Implications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 2374–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniec, B.; Guliński, J. Metathesis of Vinyltrialkoxysilanes. J. Organomet. Chem. 1984, 266, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniec, B.; Majchrzak, M.; Prukała, W.; Kubicki, M.; Chadyniak, D. Highly Stereoselective Synthesis, Structure, and Application of (E)-9-[2-(Silyl)Ethenyl]-9H-Carbazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 8550–8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniec, B.; Pietraszuk, C. Silylation of Styrene with Vinylsilanes Catalyzed by RuCl(SiR3)(CO)(PPh3)2 and Ru(H)Cl(CO)(PPh3)3. Organometallics 1997, 16, 4320–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, M.; Hybsz, M.; Kostera, S.; Kubicki, M.; Marciniec, B. A highly stereoselective synthesis of new styryl-π-conjugate organosilicon compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 3055–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniec, B.; Chadyniak, D.; Krompiec, S. Stereoselective Synthesis of Amides Possessing a Vinylsilicon Functionality via a Ruthenium Catalyzed Silylative Coupling Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 4065–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, M.; Marciniec, B.; Itami, Y. Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of Arylene-Silylene-Vinylene Polymers. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005, 347, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itami, Y.; Marciniec, B.; Kubicki, M. Functionalization of Octavinylsilsesquioxane by Ruthenium-Catalyzed Silylative Coupling versus Cross-Metathesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluć, P.; Prukala, W.; Marciniec, B. Silylative Coupling of Olefins with Vinylsilanes in the Synthesis of π-Conjugated Double Bond Systems. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, Y.; Hiyama, T. Cross-Coupling of Organosilanes with Organic Halides Mediated by Palladium Catalyst and Tris(Diethylamino)Sulfonium Difluorotrimethylsilicate. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prukała, W.; Majchrzak, M.; Pietraszuk, C.; Marciniec, B. Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of E-4-Chlorostilbene and Its Derivatives via Tandem Cross-Metathesis (or Silylative Coupling) and Hiyama Coupling. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 254, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prukała, W.; Marciniec, B.; Majchrzak, M.; Kubicki, M. Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of Para-Substituted (E)-N-Styrylcarbazoles via Sequential Silylative Coupling-Hiyama Coupling Reaction. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluć, P.; Szudkowska, J.; Hreczycho, G.; Marciniec, B. One-Pot Synthesis of (E)-Styryl Ketones from Styrenes. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6438–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.B.; Mcgarvey, G. A Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of Vinyl Bromides and Chlorides via Disubstituted Vinylsilanes. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 4424–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, M.A.; Neuy, A. The β-effect: Changing the Ligands on Silicon. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamao, K.; Akita, M.; Maeda, K.; Kumada, M. Silafunctional Compounds in Organic Synthesis. 32. Stereoselective Halogenolysis of Alkenylsilanes: Stereochemical Dependence on the Coordination State of the Leaving Silyl Groups. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamos, D.P.; Taylor, A.G.; Kishi, Y. A Mild Preparation of Vinyliodides from Vinylsilanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 8647–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Asano, K.; Umeda, K.; Katayama, H.; Ozawa, F. Highly (Z)-Selective Hydrosilylation of Terminal Alkynes Catalyzed by a Diphosphinidenecyclobutene-Coordinated Ruthenium Complex: Application to the Synthesis of (Z,Z)-bis(2-Bromoethenyl)Arenes. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10511–10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluć, P.; Hreczycho, G.; Szudkowska, J.; Kubicki, M.; Marciniec, B. New One-Pot Synthesis of (E)-β-Aryl Vinyl Halides from Styrenes. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3390–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluć, P.; Franczyk, A.; Walkowiak, J.; Hreczycho, G.; Kubicki, M.; Marciniec, M. (E)-9-(2-Iodovinyl)-9H-Carbazole-a-New-Coupling-Reagent-for-the-Synthesis-of-π-Conjugated-Carbazoles. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1976–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawluć, P.; Franczyk, A.; Walkowiak, J.; Hreczycho, G.; Kubicki, M.; Marciniec, B. Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of N-Substituted π-Conjugated Phthalimides. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 3545–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, C.; Tsutsui, T.; Saito, S. Blue Light-Emitting Organic Electroluminescent Devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1990, 56, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Darshi, M.; Kanvah, S. α-ω-Diphenylpolyenes-Cabable-of-Exhibiting-Twisted-Intramolecular-Charge-Transfer- Fluorescence: A Fluorescence and Fluorescence Probe Study of Nitro- and Nitrocyano-Substituted 1,4-Diphenylbutadienes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, V.; Chaumeil, H.; Defoin, A.; Carré, C. Synthesis of Alkoxynitrostilbenes as Chromophores for Nonlinear Optical Materials. Synthesis 2007, 2007, 3333–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiyuki, K.; Hiromichi, O.; Shigeru, A. Effects of Stilbene Derivatives on Arachidonate Metabolism in Leukocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Lipids Lipid Metab. 1985, 837, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, M.; Nagarathnam, D.; Gopal, D.; Chakraborti, A.K.; Lin, C.M.; Hamel, E. Synthesis and Evaluation of Stilbene and Dihydrostilbene Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents That Inhibit Tubulin Polymerization. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 2579–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.S.; Kang, B.S.; Ryu, S.Y.; Chang, I.M.; Min, K.R.; Kim, Y. Inhibitory Effects of Resveratrol Analogs on Unopsonized Zymosan-Induced Oxygen Radical Production. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.K.; Chaudhary, G.; Srivastava, A.K. Protective Effect of Resveratrol against Pentylenetetrazole-Induced Seizures and Its Modulation by an Adenosinergic System. Pharmacology 2002, 65, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.T.; Chien, Y.Y.; Liao, Y.L.; Lin, C.C.; Chou, M.Y.; Leung, M.K. Efficient and Convenient Nonaqueous Workup Procedure for the Preparation of Arylboronic Esters. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alver, Ö. DFT, FT-Raman, FT-IR, Solution and Solid State NMR Studies of 2,4-Dimethoxyphenylboronic Acid. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2011, 14, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.W.; Weiss, J.W.E.; Kerneghan, P.A.; Korobkov, I.; Maly, K.E.; Bryce, D.L. Solid-State 11B and 13C NMR, IR, and X-Ray Crystallographic Characterization of Selected Arylboronic Acids and Their Catechol Cyclic Esters. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2012, 50, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrackmeyer, B. Organoboranes and Tetraorganoborates Studied by 11B and 13C NMR Spectroscopy and DFT Calculations. Z. Naturforsch. Sect. B J. Chem. Sci. 2015, 70, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakatsuki, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Nakano, M.; Yamamoto, Y. Ruthenium-catalysed Disproportionation between Vinylsilanes and Mono-substituted Alkenes via Silyl Group Transfer. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1991, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmann, D.; Ruf, R.; Knoch, F.; Moll, M. Transition-Metal Complexes with Sulfur Ligands. 112. Synthesis and Characterization of Ruthenium Complexes with [RuPS2N2] Cores. Substitution, Redox and Acid-Base Reactions of [RuII(L)(PR3)(‘S2N2H2’)], (L = CO, PPr3, R = Pr or Cy) and Five-Coordinate [RuIV(PCy3)(‘S2N2’)]. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 4745–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinger, B.M.; Mol, C.J. Degradation of the First-Generation Grubbs Metathesis Catalyst with Primary Alcohols, Water, and Oxygen. Formation and Catalytic Activity of Ruthenium(II) Monocarbonyl Species. Organometallics 2003, 22, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Park, S.; Martinez, K.; Gray, J.L.; Thowfeik, F.S.; Lundeen, J.A.; Kuhn, A.E.; Charboneau, D.J.; Gerlach, D.L.; Lockart, M.M.; et al. Ruthenium Complexes are pH-Activated Metallo Prodrugs (pHAMPs) with Light-Triggered Selective Toxicity Toward Cancer Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 7519–7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, P.; Pietraszuk, C.; Marciniec, B. Cross-Metathesis of Vinyl-Substituted Linear and Cyclic Siloxanes with Olefins in the Presence of Grubbs Catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2008, 289, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grachek, V.I.; Lukashik, A.N. Boric Acid Esters as Thermal Stabilizers and Fungicidal Additives for Elastomers from Natural Rubber. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2006, 79, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J. Synthesis and Characterization of a New Thermosetting Boric Acid Ester. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 239–242, 1907–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grachek, V.I.; Krut’Ko, E.T.; Osmolovskaya, L.Y.; Globa, A.I. Thermal Stabilization of Polyimides with Boric Acid Esters. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2011, 84, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Ran, L. “Chemical Bond Energies” Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group, CRC Press: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Vazquez, A.; Wang, D.; Li, S. Mechanism of thermal decomposition of tetramethylsilane: A flash pyrolysis vacuum ultraviolet photoionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and density functional theory study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 18782–18789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) Committee on Prudent Practices in the Laboratory. Prudent Practices in The Laboratory: Handling and Management of Chemical Hazards; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 0-309-13865-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.