Biomacromolecule-Regulated Biomimetic Mineralization for Efficiently Immobilizing Cells to Enhance Thermal Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

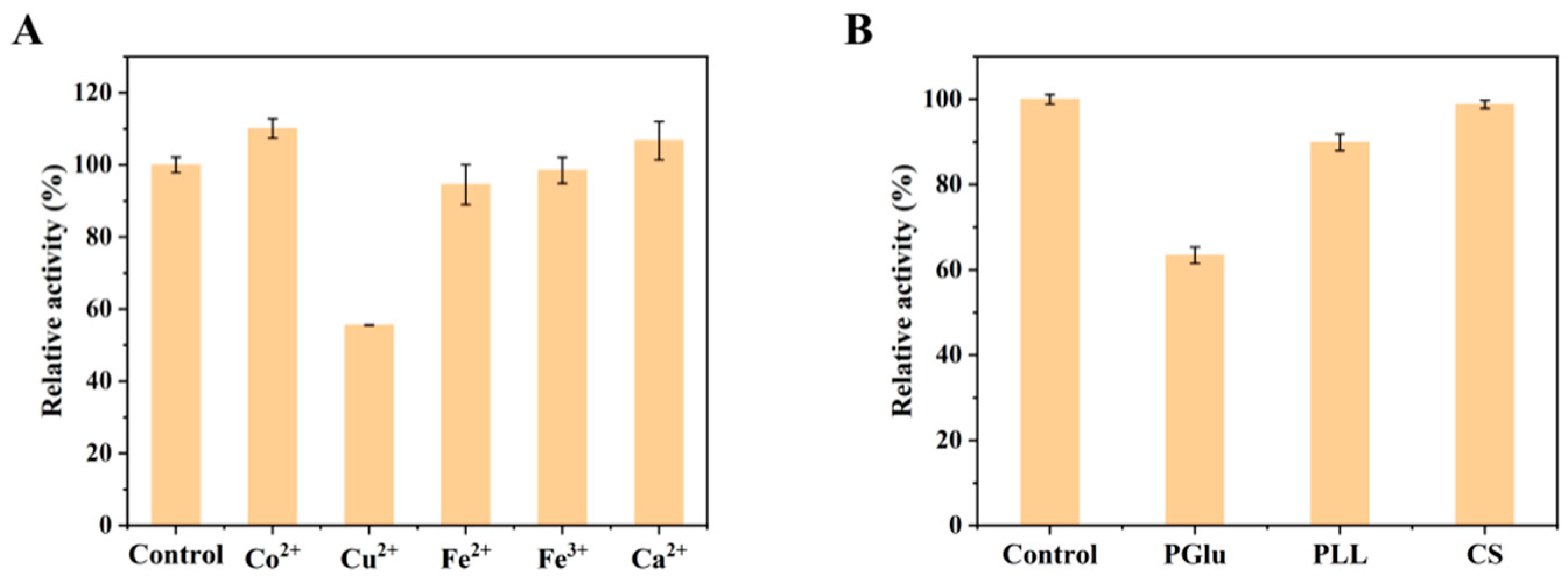

2.1. Screening of Biological Macromolecules and Inorganic Metal Ions

2.2. Effects of Immobilization Conditions on Relative Activity of CS-CaP@cells

2.3. Characterization of Free Cells and CS-CaP@cells via SEM and EDS

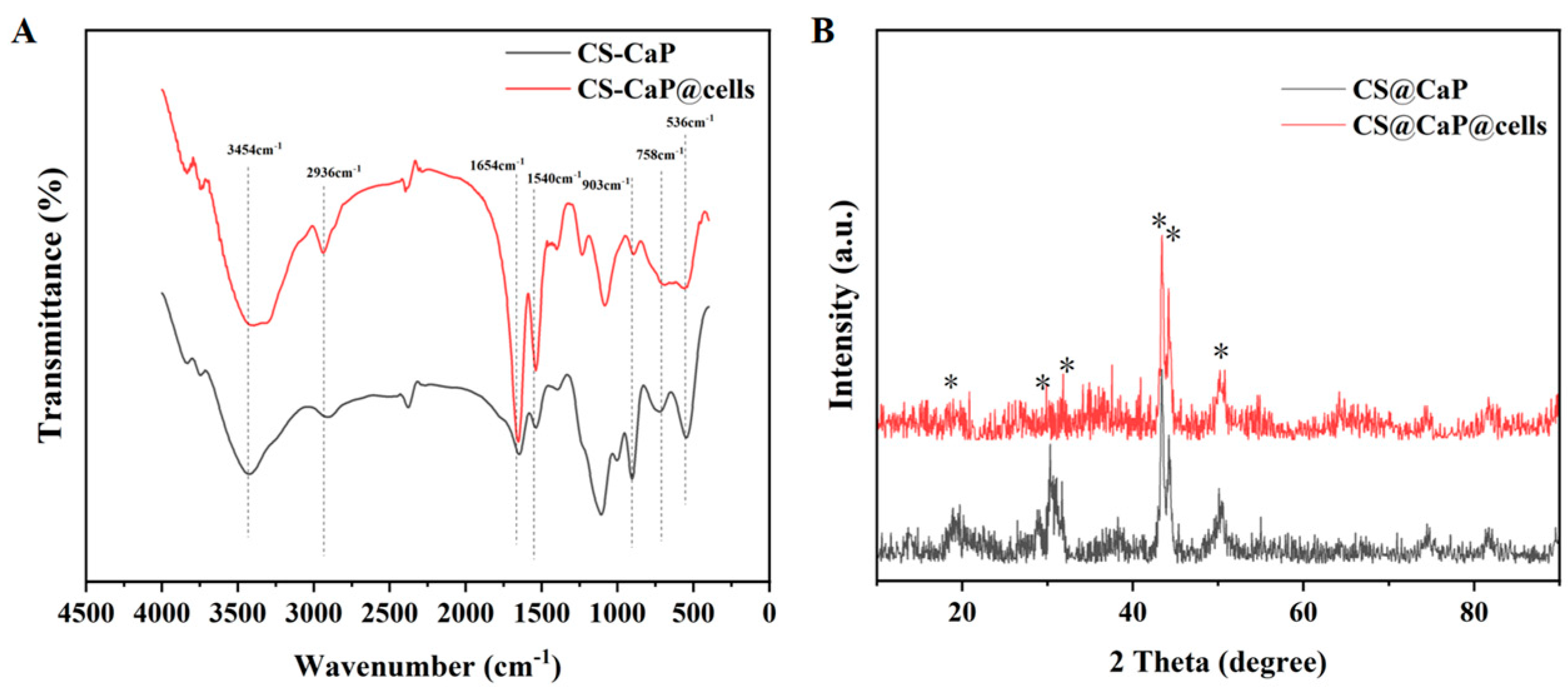

2.4. Characterization of CS-CaP and CS-CaP@cells via FTIR and XRD

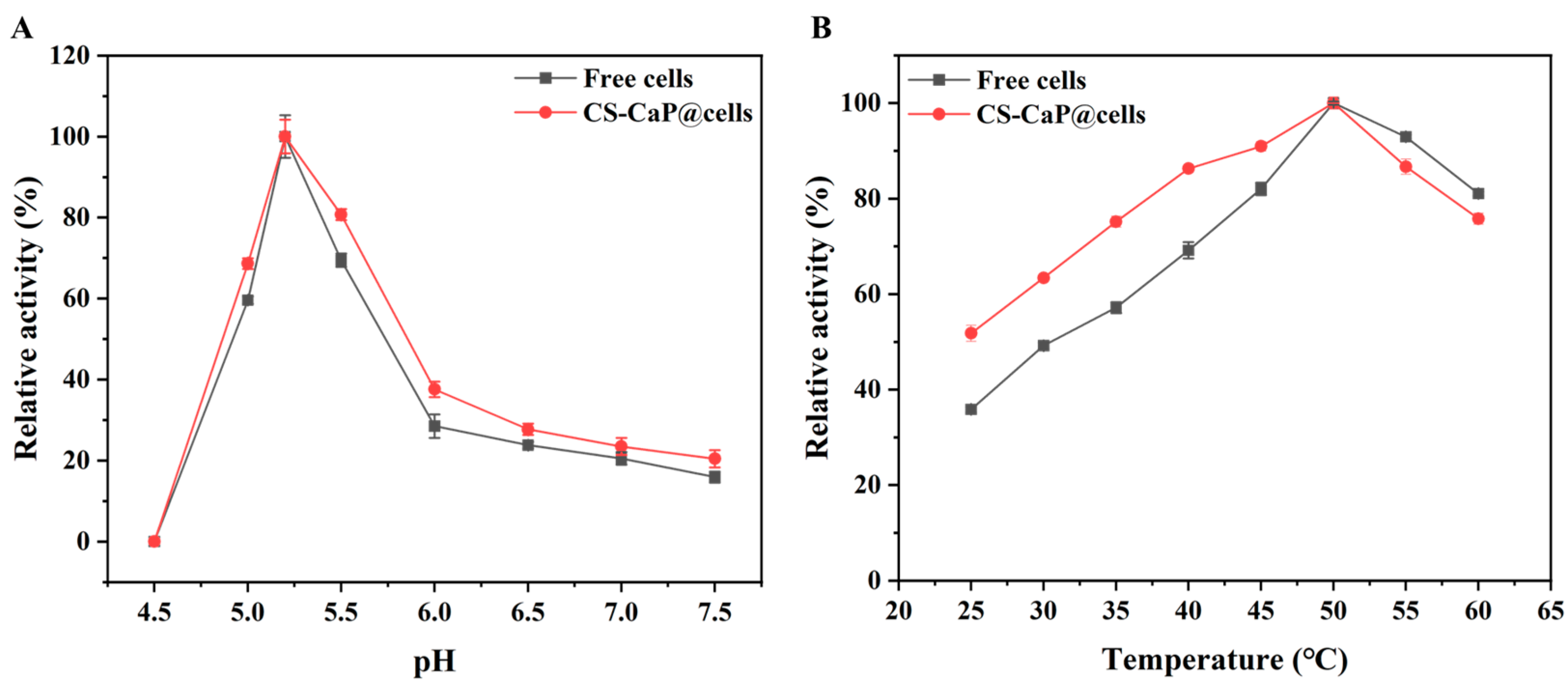

2.5. Optimal Reaction Conditions for Free Cells and CS-CaP@cells

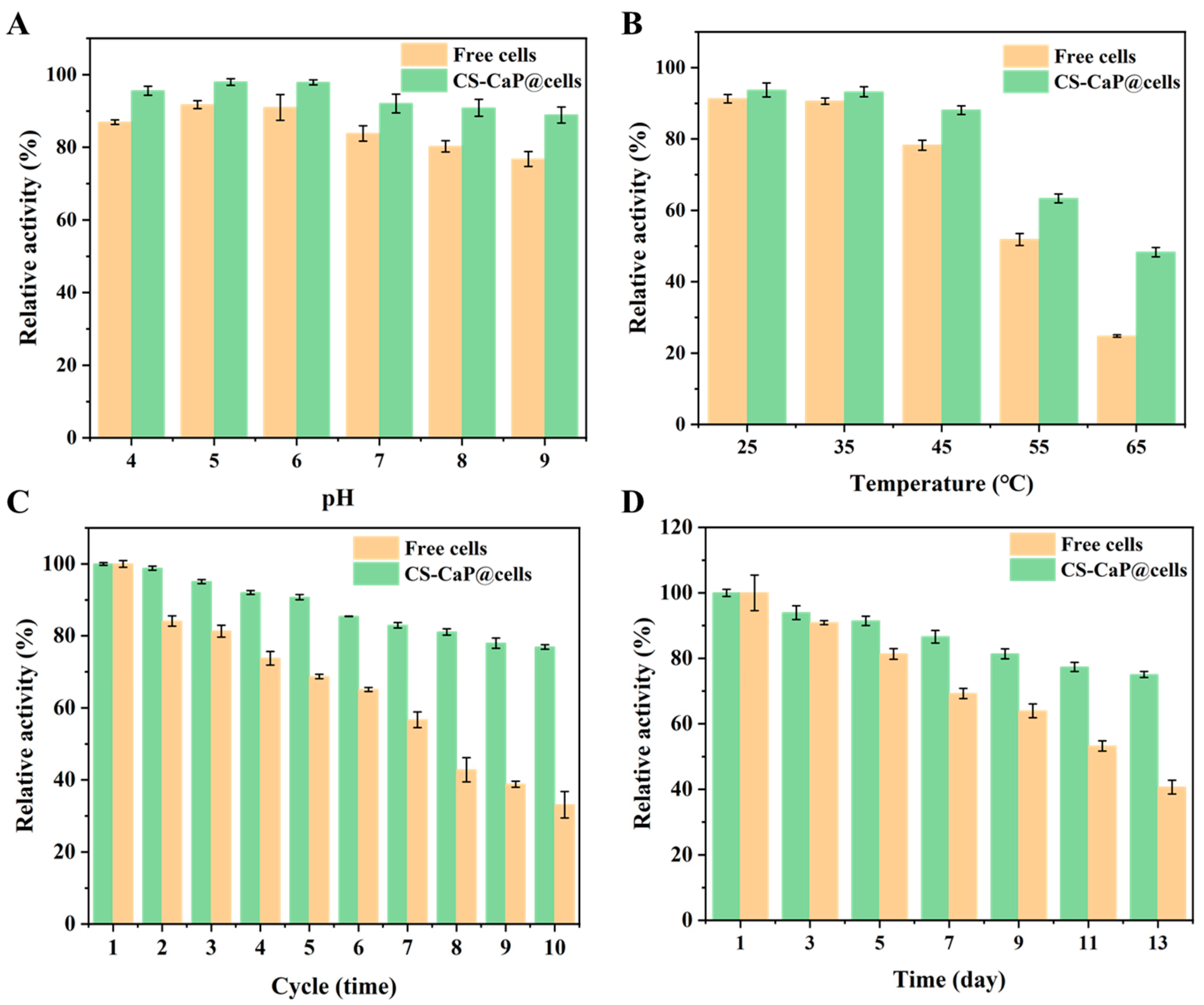

2.6. Thermal, pH, and Storage Stability and Reusability of Free Cells and CS-CaP@cells

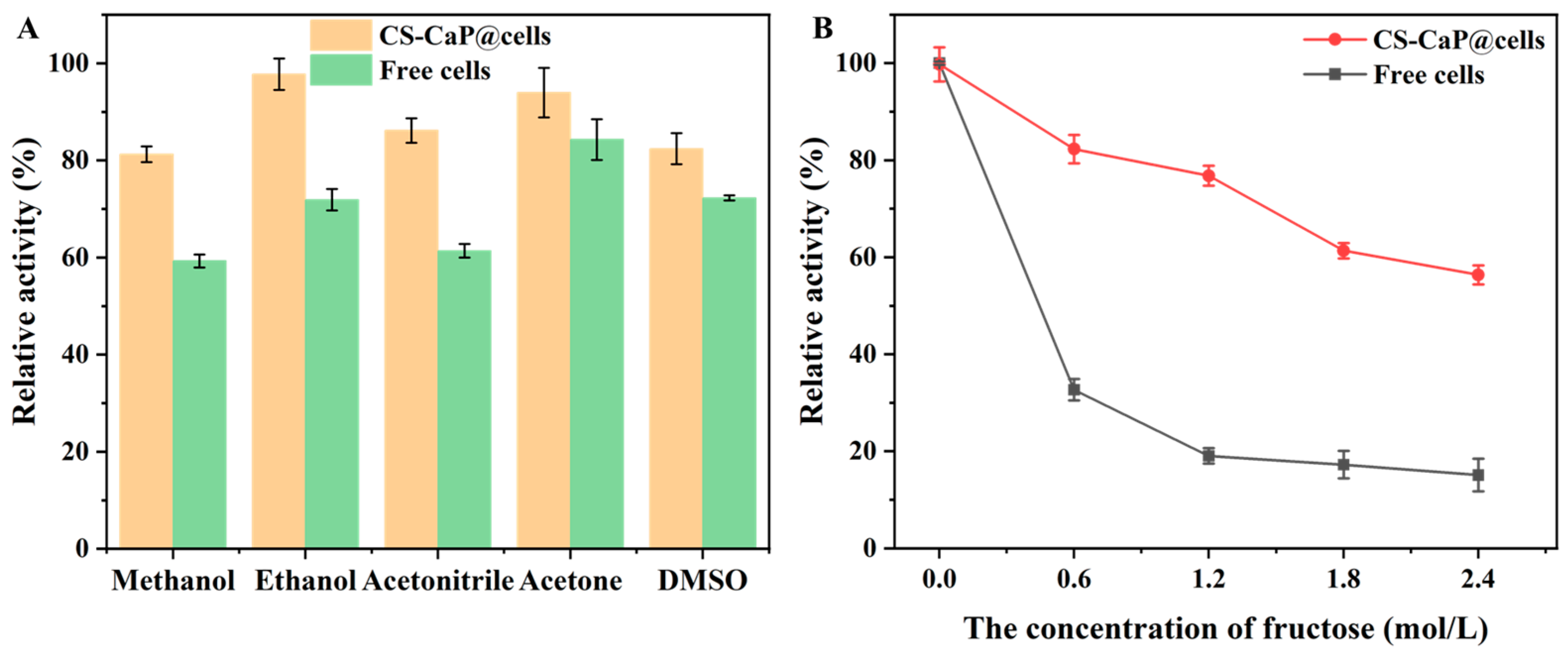

2.7. Organic Solvent and Byproduct Tolerance of Free Cells and CS-CaP@cells

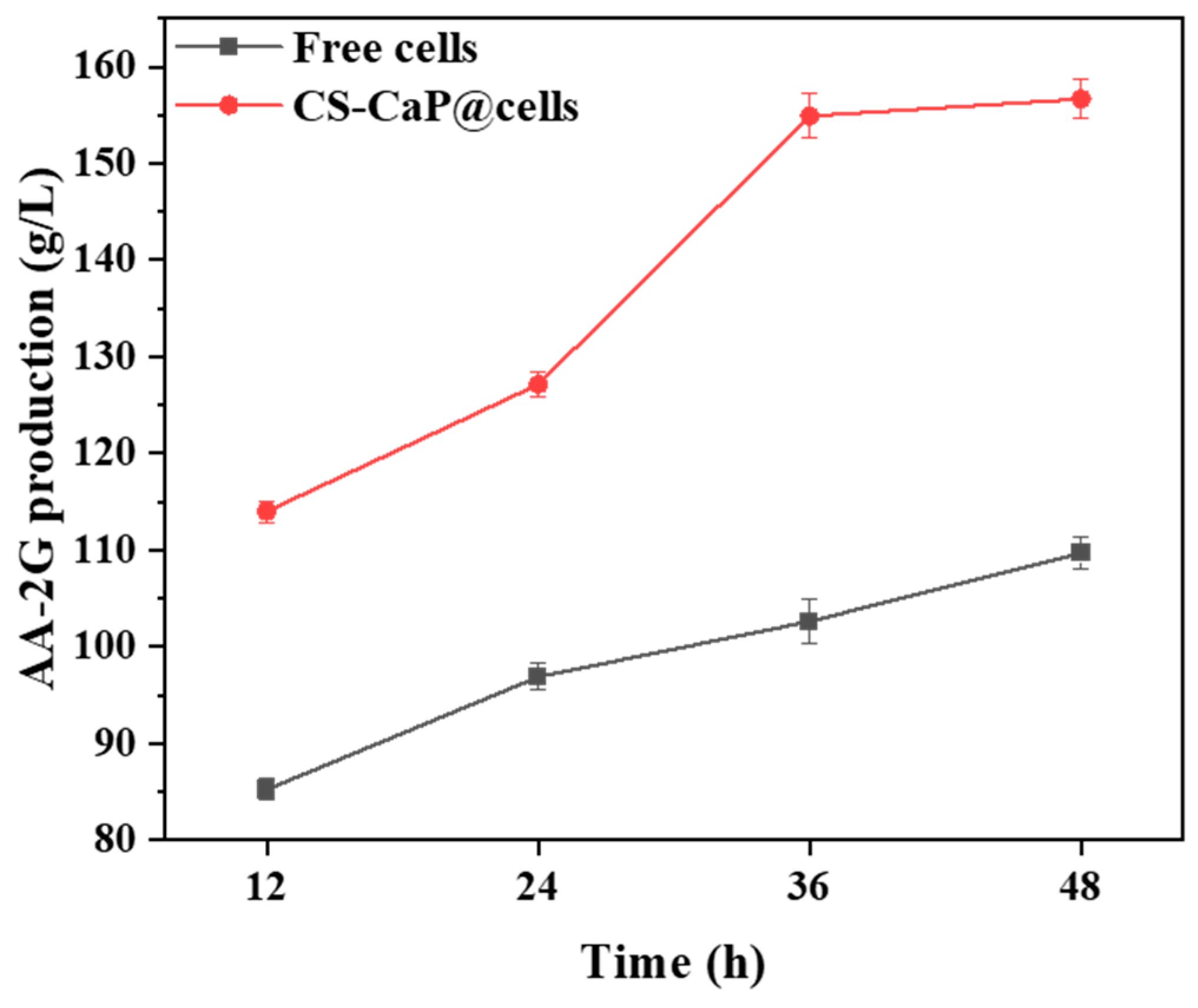

2.8. Comparing the Catalytic Performance of Free Cell and CS-CaP@cells

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Strains and Vector

3.2. E. coli Culture

3.3. Screening of Biological Macromolecules and Metal Ions

3.4. Construction of CS-CaP@cells

3.5. Characterization of Free Cells, CS-CaP, and CS-CaP@cells

3.6. SPase Activity Assay and Standard Curve Construction

3.7. Optimal Reaction Conditions and Stability of Free Cells and CS-CaP@cells

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPase | Sucrose phosphorylase |

| GG | Glycerol glucoside |

| AA-2G | 2-O-α-D-glucopyranosyl-L-ascorbic acid |

| PEI | Polyethyleneimine |

| TPP | Tripolyphosphate |

| CS-CaP@cells | Immobilized cells |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| IPTG | Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

Appendix A

Construction of Standard Curves for L-AA and AA-2G

References

- Franceus, J.; Desmet, T. Sucrose Phosphorylase and Related Enzymes in Glycoside Hydrolase Family 13: Discovery, Application and Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yin, T.; Wei, B.; Su, M.; Liang, H. Turning waste into treasure: Biosynthesis of value-added 2-O-alpha-glucosyl glycerol and d-allulose from waste cane molasses through an in vitro synthetic biology platform. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 391, 129982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudiminchi, R.K.; Nidetzky, B. Walking a Fine Line with Sucrose Phosphorylase: Efficient Single-Step Biocatalytic Production of l-Ascorbic Acid 2-Glucoside from Sucrose. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X. Research progress and application of enzymatic synthesis of glycosyl compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5317–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Liang, H. Fabricating compartmented nanoreactor via protein self-regulated biomimetic mineralization for multienzyme immobilization. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Ren, S.; Sun, B.; Jia, S. Optimization protocols and improved strategies for metal-organic frameworks for immobilizing enzymes: Current development and future challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 370, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, S.; Kou, X.; Wei, S.; Huang, S.; Jiang, S.; Shen, J.; Zhu, F.; Ouyang, G. A Convenient and Versatile Amino-Acid-Boosted Biomimetic Strategy for the Nondestructive Encapsulation of Biomacromolecules within Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jin, N.; Katsuda, T.; Fukuda, H.; Yamaji, H. Immobilization of Escherichia coli cells using polyethyleneimine-coated porous support particles for l-aspartic acid production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2009, 46, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Dong, Y.; Xie, D.; Li, Z.-q.; Xue, Y.-P.; Zheng, Y.-G. Immobilization of Escherichia coli cells harboring a nitrilase with improved catalytic properties though polyethylenemine-induced silicification on zeolite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Fernández, M.; Neto, W.; López, C.; Álvaro, G.; Tufvesson, P.; Woodley, J.M. Immobilization of Escherichia coli containing ω-transaminase activity in LentiKats®. Biotechnol. Prog. 2012, 28, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.; Fan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Yan, Y. A new lipase–inorganic hybrid nanoflower with enhanced enzyme activity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 19413–19416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-q.; Sun, D.-x.; Qi, X.-d.; Yang, J.-h.; Dai, S.; Wang, Y. Biomineralization-Inspired Ultra-tough and Robust Self-healing Waterborne Polyurethane Elastomers. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 10567–10579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Su, W.; Liu, F. Biomimetic mineralization of nitrile hydratase into a mesoporous cobalt-based metal–organic framework for efficient biocatalysis. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, C.; Musetti, S.; Fu, L.H.; Zhu, Y.J.; Huang, L. Biomolecule-assisted green synthesis of nanostructured calcium phosphates and their biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2698–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Feng, H.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Luo, P.; Wang, Y. Construction of Multienzyme Co-immobilized Hybrid Nanoflowers for an Efficient Conversion of Cellulose into Glucose in a Cascade Reaction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7910–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Luo, P.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Y. Construction of a Multienzymatic Cascade Reaction System of Coimmobilized Hybrid Nanoflowers for Efficient Conversion of Starch into Gluconic Acid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 15023–15033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi-kaji, S.; Shareghi, B.; Saboury, A.A.; Farhadian, S. Spectroscopic and molecular docking studies on the interaction between spermidine and pancreatic elastase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, S.; Nishii, I.; Kanaoka, S. Biomineralization-inspired fabrication of chitosan/calcium carbonates core-shell type composite microparticles as a drug carrier. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.; Hesemann, P. Synthesis and characterization of N-guanidinium chitosan/silica ionic hybrids as templates for calcium phosphate mineralization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, C.; Tian, C. Facile one-pot preparation of chitosan/calcium pyrophosphate hybrid microflowers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 14522–14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liao, K. Recent Advances in Emerging Metal– and Covalent–Organic Frameworks for Enzyme Encapsulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 56752–56776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-W.; Prabhu, P.; Lee, J.-K. Alginate immobilization of recombinant Escherichia coli whole cells harboring l-arabinose isomerase for l-ribulose production. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 33, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Liu, H.; Pang, L.; Guo, K.; Li, J. Biocatalyst and Colorimetric/Fluorescent Dual Biosensors of H2O2 Constructed via Hemoglobin-Cu3(PO4)2 Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Nanoflowers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 30441–30450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Fang, Z.; Duan, H.; Liang, L. Polydopamine-mediated synthesis of core-shell gold@calcium phosphate nanoparticles for enzyme immobilization. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 2841–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Tian, C.; Ren, C.; Chen, P.; Men, Y.; Sun, Y. High-Yield Biosynthesis of Glucosylglycerol through Coupling Phosphorolysis and Transglycosylation Reactions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 15249–15256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks-Hofmeister, M.E.; Verhaeghe, T.; De Winter, K.; Desmet, T. Creating Space for Large Acceptors: Rational Biocatalyst Design for Resveratrol Glycosylation in an Aqueous System. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 9289–9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yao, S.; Xu, H.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liang, H. Biomacromolecule-Regulated Biomimetic Mineralization for Efficiently Immobilizing Cells to Enhance Thermal Stability. Catalysts 2026, 16, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010046

Yao S, Xu H, Jin Y, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Kang Y, Wang H, Liang H. Biomacromolecule-Regulated Biomimetic Mineralization for Efficiently Immobilizing Cells to Enhance Thermal Stability. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Shuyi, Haichang Xu, Yankun Jin, Jinjing Zhang, Yaru Zhao, Yilin Kang, Haoyue Wang, and Hao Liang. 2026. "Biomacromolecule-Regulated Biomimetic Mineralization for Efficiently Immobilizing Cells to Enhance Thermal Stability" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010046

APA StyleYao, S., Xu, H., Jin, Y., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., Kang, Y., Wang, H., & Liang, H. (2026). Biomacromolecule-Regulated Biomimetic Mineralization for Efficiently Immobilizing Cells to Enhance Thermal Stability. Catalysts, 16(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010046