Abstract

The effective remediation of cadmium (Cd) pollution continues to pose a significant challenge in environmental science. Bacteria-loaded biochar (BLBC), a composite material synthesized by immobilizing functional microorganisms onto biochar, has emerged as a promising adsorbent for Cd due to its ability to simultaneously facilitate adsorption and biodegradation. In this study, a manganese (Mn)-oxidizing bacterium (Priestia sp. Z-MLHA-1), isolated from a high-manganese mining area, was successfully used to prepare BLBC. The Cd(II) immobilization performance and underlying mechanisms were systematically investigated. The results showed that bacterial loading significantly optimized the pore structure of the biochar, increasing its specific surface area by 40% and enriching the diversity of surface functional groups. Adsorption experiments demonstrated a strong affinity of BLBC for Cd(II), with a maximum adsorption capacity of 44.17 mg/g. The adsorption behavior followed the Langmuir isotherm and pseudo-second-order kinetic models, indicating a monolayer process dominated by chemisorption. The primary immobilization mechanisms involved complexation with surface oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., −COOH, −OH), ion exchange, and a synergistic effect between the biochar and the immobilized microorganisms. This material enables efficient Cd(II) removal under environmentally benign conditions, thereby providing a theoretical foundation and technical support for the development of green and sustainable remediation technologies for heavy metal-contaminated water.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of industrialization and urbanization has made heavy metal pollution a major global environmental challenge. Among various heavy metals, cadmium (Cd), a highly toxic element, poses a serious threat to ecosystem stability and human health due to its wide distribution, environmental persistence, and significant bioaccumulation potential [1,2]. Cd acts as both an inducer and a promoter in the onset and progression of various diseases [3]. It can accumulate in the human body through the food chain, and long-term exposure may lead to irreversible renal and hepatic damage, skeletal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and several types of cancer [4,5]. Conventional techniques for Cd removal, such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange, and membrane separation, can effectively reduce aqueous Cd concentrations in the short term. However, they often suffer from limitations including high operational costs, limited efficiency, and risks of secondary pollution [2,6,7]. In contrast, adsorption has gained widespread attention due to its high efficiency, low cost, and operational simplicity [8,9,10].

Biochar (BC), a porous carbon material produced from biomass pyrolysis, possesses a high specific surface area, abundant surface functional groups, and robust structural stability [11,12]. These properties endow it with strong physical adsorption capacity and chemical reactivity in immobilizing heavy metals [13,14]. Microbial remediation, on the other hand, utilizes specific functional microorganisms such as Mn-oxidizing bacteria to mediate the formation of metal oxides. These biogenic minerals typically exhibit high specific surface areas, well-developed pore structures, and numerous surface active sites, showing excellent environmental functionality in adsorbing and transforming pollutants [15]. Nevertheless, the standalone application of either biochar or microbial technology in heavy metal remediation still faces limitations, such as finite adsorption capacity and difficulties in material recovery and regeneration [16]. To overcome the constraints of single-technology approaches, modification or composite strategies have been developed to enhance the overall performance of biochar. Among these, bacteria-loaded biochar (BLBC) has emerged as a novel functional material. By immobilizing functional microorganisms onto biochar, BLBC effectively integrates the strong adsorption properties of biochar with the metabolic activity of microbes, demonstrating significant potential for remediating Cd pollution [17]. Recent studies on microbe–biochar synergistic mechanisms have shown that biochar loaded with mixed bacterial strains (Enterobacter and Klebsiella) could reduce soil DTPA-Cd by 22.05–55.84% and lower Cd content in pakchoi by 28.68–51.01% [18]. In another example, corn straw biochar immobilized with Klebsiella grimontii achieved a maximum Cd(II) adsorption capacity of 71.75 mg/g, significantly surpassing the performance of its individual components [19]. The efficiency of Cd adsorption and biotransformation is influenced by the immobilization efficacy of microorganisms, which varies with the pore structure and nitrogen content of biochar derived from different feedstocks. Despite these advances, the mechanism by which bacteria-loaded biochar regulates Cd(II) immobilization remains insufficiently understood, warranting systematic and in-depth investigation.

In this study, a Mn-oxidizing bacterial strain (Priestia sp. Z-MLHA-1), isolated from a high-manganese mining area, was used to prepare BLBC. We systematically investigated the Cd(II) immobilization characteristics and underlying mechanisms in aqueous solutions. The specific objectives were to: (1) analyze the physicochemical structural properties of the BLBC loaded with strain Z-MLHA-1; (2) evaluate the Cd(II) immobilization performance of BLBC under different conditions; and (3) elucidate the interaction mechanisms between BLBC and Cd(II). By revealing the molecular-level mechanisms of Cd(II) immobilization by BLBC from a multi-interface chemistry perspective, this research aims to provide a theoretical basis for developing efficient and sustainable technologies for remediating Cd(II) contamination in water.

2. Results

2.1. Experimental Materials

Soil samples used in this study were collected from a high-manganese mining area in Hanzhong City, Shaanxi Province. To maintain their original properties, the samples were stored at 4 °C. The Mn-oxidizing bacterium Priestia sp. Z-MLHA-1, isolated from the collected soil, has been deposited in the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC) under accession number CCTCC M 20242853. The strain was aerobically cultivated in NB liquid medium containing peptone (10 g/L), beef extract (3 g/L), and sodium chloride (5 g/L), with the pH adjusted to 7.2. Cultivation was carried out at 25 °C with shaking at 140 rpm for 3–5 days. The medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min before use. All chemical reagents used were of analytical grade. All experimental procedures were performed under sterile conditions, with utensils and ultrapure water sterilized prior to use.

2.2. Preparation of BLBC

Wheat straw was ground and screened through a 60-mesh sieve, then thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to remove surface impurities. The material was dried in an oven at 75 °C for 36 h until a constant mass was attained. The pre-treated straw was placed in a tubular pyrolysis furnace and pyrolyzed under a nitrogen atmosphere. The temperature was raised to 300 °C at a heating rate of 15 °C/min and held for 3 h. After pyrolysis, the system was cooled naturally to room temperature to obtain the final biochar (BC). The bacterial strain was inoculated into 100 mL of NB liquid medium and cultured at 30 °C with shaking at 150 r/min for 36 h. The resulting bacterial broth was centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was washed twice with sterile water, resuspended, and adjusted to a final volume of 100 mL to achieve an OD600 of approximately 1.0. Then, 2 g of the prepared wheat straw biochar was added to the bacterial suspension, and the mixture was co-cultured at 30 °C and 150 r/min for 24 h to facilitate bacterial loading. The resulting bacteria-loaded biochar (BLBC) was washed with sterile water, freeze-dried, and stored for subsequent use.

2.3. Characterization of BLBC

The physicochemical properties of the prepared materials were characterized using multiple analytical techniques. The specific surface area and pore structure parameters were determined by nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements using a specific surface area and porosity analyzer (BET method, JW-BK400, Beijing, China). Surface morphology and elemental distribution were examined with a scanning electron microscope coupled with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (SEM-EDS, ZEISS Sigma 300, Oberkochen, Germany). The crystalline phases of materials before and after adsorption were identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8-Focus, Karlsruhe, Germany). Furthermore, functional groups present on the biochar surface were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS20, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Batch Experiments

Simulated Cd(II) solutions with concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 mg/L were prepared using cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate (Cd(NO3)2·4H2O) to investigate the immobilization characteristics and mechanisms of Cd(II) by BLBC. Batch experiments were performed by adding 0.5 g/L of BC or BLBC into 50 mL of Cd(II) solution (initial pH 7.20) in centrifuge tubes. The mixtures were then shaken at 120 rpm and 30 °C. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Samples were taken at predetermined time intervals, and the residual Cd(II) concentration was measured using a flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Hitachi ZA3000). The Cd(II) removal efficiency (Re, %) and adsorption capacity (qe, mg/g) were calculated using Equations (1) and (2), respectively.

Here, C0 and Ce represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations of Cd(II) (mg/L), respectively; V is the volume of the solution (L); and m is the mass of the adsorbent (g).

To further elucidate the adsorption mechanism, the kinetic data were fitted using the pseudo-first-order (Equation (3)), pseudo-second-order (Equation (4)), Elovich (Equation (5)), and intra-particle diffusion (Equation (6)) models [20].

Here, Qt and Qe are the adsorption capacities (mg/g) at time t and at equilibrium, respectively. t is adsorption time (h); For k1 and k2, the adsorption rate constants for pseudo-first-order (h−1) and pseudo-second-order kinetic models [g (mg∙h)−1], respectively; α and β are constants in the Elovich model; K3 is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant; and C is the particle diffusion model constant.

Additionally, the equilibrium adsorption data were analyzed using the Langmuir (Equation (7)), Freundlich (Equation (8)), Temkin (Equation (9)), and Dubinin–Radushkevich (Equation (10)) isotherm models [21].

In these equations, Qe and Qm represent the equilibrium and theoretical maximum adsorption capacities (mg/g) for Cd(II), respectively; Ce denotes the equilibrium concentration (mg/L); KL is the Langmuir equilibrium constant (L/mg); KF and n are the Freundlich constants; a and b are Temkin constants; QDR and KDR represent the maximum adsorption capacity (mmol/kg) and the constant in the Dubinin–Radushkevich model, respectively; R is the universal gas constant; and T is the absolute temperature (K).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characterization Analysis of BLBC and BC

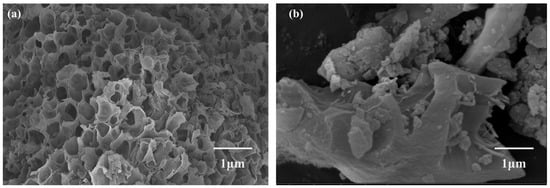

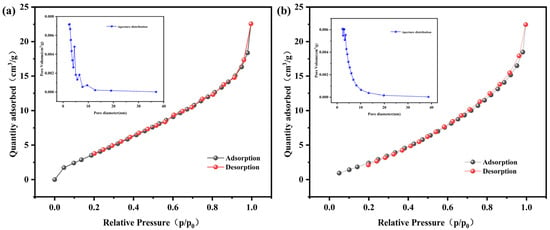

The surface morphologies of BC and BLBC were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Figure 1a, the pristine BC surface was relatively smooth, displaying the characteristic porous, gully-like structure resulting from the pyrolysis of plant straw [22], with a limited presence of naturally adhered mineral particles. In contrast, the microscopic morphology of BLBC revealed significant alterations (Figure 1b). Well-defined bacterial cells were observed on the biochar surface, which was further decorated with granular substances of varying sizes, appearing in both agglomerated and dispersed forms. This complex morphology reflects the interactive features between the biochar and the immobilized bacterial components, confirming successful microbial loading. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of both BC and BLBC exhibited overall type-II characteristics, with a slight hysteresis loop observed in the high relative pressure region. For BC, the weak hysteresis loop and low specific surface area might be attributed to its dominant large pores or interconnected macropores, which are less accessible to N2 molecules, leading to a discrepancy between the SEM-observed macroscopic porous morphology and BET-measured surface area. This phenomenon is common in plant-derived biochars pyrolyzed at relatively low temperatures (300 °C), where macropores from the original straw structure are retained but contribute minimally to N2 adsorption capacity. Pore size distribution analysis confirmed the predominance of mesoporous structures in both materials (Figure 2), which is consistent with typical mesoporous adsorbents [23,24]. The specific surface area of BC was measured at 41.48 m2/g, with a total pore volume of 0.032 cm3/g and an average pore width of 6.54 nm. After bacterial modification, the specific surface area of BLBC increased markedly to 58.06 m2/g, while the pore volume and average pore width remained largely unchanged (0.032 cm3/g and 6.58 nm, respectively). Although the isotherm shapes and pore size distribution curves of BC and BLBC appear similar, the significant increase in specific surface area of BLBC (≈40%) directly reflects the optimization of pore accessibility by bacterial loading—bacterial cells and their metabolites might fill partial macropore channels or attach to pore walls, converting some inaccessible macropores into N2-accessible mesopores. This explains the distinct morphological features observed by SEM (bacterial attachment and surface roughness) while maintaining similar pore size distribution trends. This notable increase in surface area aligns with the morphological changes observed via SEM and collectively verifies the successful optimization of the material’s physical structure through bacterial loading. It should be noted that a limitation of this study is the absence of precise quantitative data on the bacterial load immobilized on the biochar. This stems from the practical difficulty in accurately enumerating cells attached to or entrapped within the complex porous network of biochar using conventional detachment and plating methods, which may underestimate viable cell counts. Future work should employ culture-independent quantification techniques, such as qPCR targeting bacterial genes, or direct imaging approaches to establish a clear correlation between immobilized cell density and the system’s functional performance.

Figure 1.

SEM images of biochar (a) and microbial-loaded biochar (b).

Figure 2.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution curves of BC (a) and BLBC (b).

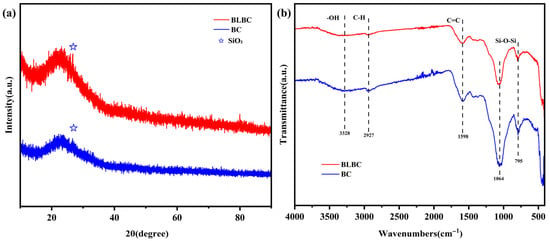

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to analyze the crystalline phases in wheat straw biochar before and after bacterial modification (Figure 3a). A broad diffuse hump centered around 22° (2θ) indicated the dominant presence of amorphous carbon, which is typical for plant straw-derived biochars [25]. A sharp diffraction peak at 26° (2θ) was identified as silicon dioxide (SiO2, quartz phase), an inherent inorganic component in the raw straw [26]. In the BLBC sample, the intensity of the SiO2 diffraction peak was noticeably enhanced. This suggests that microbial activity during modification may have preferentially dissolved part of the amorphous carbon or other soluble mineral phases, leading to the relative enrichment and increased detectability of the more crystalline SiO2 component [27]. No new crystalline phases were detected, indicating that the bacterial modification did not form new crystalline minerals but rather altered the relative composition and distribution of pre-existing components.

Figure 3.

(a) XRD patterns and (b) FTIR spectra of BC and BLBC.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to identify surface functional groups on BC and BLBC (Figure 3b). A broad absorption band around 3328 cm−1, associated with O–H and N–H stretching vibrations, confirmed the presence of hydroxyl and amino groups. The enhanced intensity of this band in BLBC suggests the successful introduction of additional hydrophilic functional groups derived from bacterial cells and their metabolites [28]. The peak at 2927 cm−1, attributed to aliphatic C–H stretching vibrations from partially carbonized organic matter, was attenuated in BLBC. This reduction may be due to the microbial degradation of unstable organic fractions during modification [29]. The peak near 1598 cm−1, corresponding to aromatic C=C ring vibrations, showed increased intensity in BLBC, indicating a rise in surface conjugated structures or oxygen-containing functional groups after modification [30]. The strong absorption bands observed around 1064 and 795 cm−1 can be attributed to the overlapping signals from both the Si–O–Si vibrational modes of the inherent silica phase and the C–O stretching vibrations of the residual biomass-derived carbon matrix. This indicates the hybrid organic-inorganic nature of the biochar after pyrolysis [26,31].

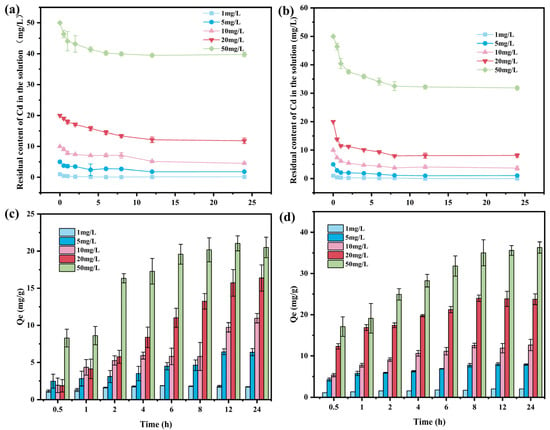

3.2. Effect of Initial Cd(II) Concentration

The adsorption performance of BC and BLBC for Cd(II) was systematically evaluated under constant conditions (adsorption temperature: 25 °C, pH: 7). BC exhibited a rapid Cd(II) removal rate during the initial stage (0–5 h) across all tested concentrations, indicating a strong initial adsorption driving force (Figure 4a). At an initial concentration of 10 mg/L, the residual Cd(II) concentration decreased to approximately 7.1 mg/L after 6 h, while at 50 mg/L, it reached about 40.2 mg/L, reflecting a more pronounced uptake at higher concentrations due to the enhanced concentration gradient. As the reaction progressed, the residual concentration gradually approached equilibrium, stabilizing notably after 10 h, which suggested the progressive saturation of available adsorption sites. In comparison, BLBC demonstrated significantly enhanced adsorption performance (Figure 4b). Under the same initial concentrations, the residual Cd(II) concentration decreased more rapidly. For instance, at 10 mg/L, the residual concentration dropped below 4.4 mg/L after 6 h, and at 50 mg/L, it reached approximately 34.1 mg/L. This improved efficiency can be attributed to the increased specific surface area and the introduction of additional functional groups after bacterial loading, which collectively enhanced the accessibility and affinity toward Cd(II) ions. The variation in adsorption capacity further highlighted the differences between the two materials. For BC (Figure 4c), the adsorption capacity increased significantly with rising initial Cd(II) concentration. At 10 mg/L, the 24-h adsorption capacity was about 10.9 mg/g, while at 50 mg/L, it reached approximately 20.5 mg/g. In the low-concentration range (1–10 mg/L), the adsorption capacity continued to increase over time, indicating that the adsorbent had not yet reached saturation. At concentrations of 20 mg/L and above, the adsorption capacity still increased, but the growth rate slowed markedly, suggesting the gradual occupation of active sites. For BLBC (Figure 4d), the overall adsorption capacity was substantially higher. At an initial Cd(II) concentration of 50 mg/L, the 24-h adsorption capacity exceeded 36.3 mg/g. Moreover, the adsorption capacity increased more rapidly, particularly in the lower concentration range, indicating that the modified material offered more active sites and stronger affinity for Cd(II), thereby delaying saturation and improving performance across a broader concentration range.

Figure 4.

Cd(II) adsorption properties at different initial concentrations: (a) residual concentration over time for BC, (b) residual concentration over time for BLBC, (c) adsorption capacity of BC, and (d) adsorption capacity of BLBC.

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherm Results

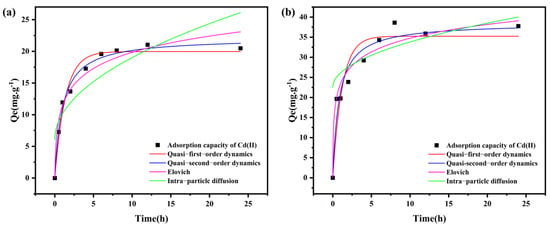

To elucidate the rate-controlling mechanisms of Cd(II) adsorption onto BC and BLBC, the experimental data were fitted using pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and intra-particle diffusion models (Table 1 and Figure 5a). For BC, the pseudo-second-order model provided the best fit (R2 = 0.9898), with a theoretical equilibrium adsorption capacity (22.15 mg/g) closely matching the experimental value. The strong applicability of the pseudo-second-order model, which is often indicative of a chemisorption process involving valence forces through electron sharing or exchange [32], suggests that chemical adsorption is a dominant mechanism. Although the pseudo-first-order model also exhibited relatively high correlation (R2 = 0.9702), its predicted Qe value (19.96 mg/g) was lower. In contrast, BLBC likewise showed a better fit with the pseudo-second-order model (R2 = 0.9436), yielding a theoretical Qe of 38.55 mg/g, significantly higher than that obtained from the pseudo-first-order model (35.25 mg/g). The conformity of both materials to this model further supports that Cd(II) adsorption is governed by chemical interactions, such as surface complexation and ion exchange. It is noteworthy that the pseudo-second-order rate constant (k2) for BLBC (0.03 g (mg·min)−1) is slightly lower than that for BC [0.05 g (mg·min)−1]. This may imply that the more complex surface structure of BLBC, while providing more adsorption sites, introduces a slightly higher diffusion resistance or that the new bacterial-derived sites have marginally different kinetics. Nonetheless, the substantially higher equilibrium capacity (Qe) of BLBC unequivocally confirms the overall enhancement due to bacterial loading.

Table 1.

Parameters of adsorption kinetic and isotherm models.

Figure 5.

Adsorption kinetics fitting for BC (a) and BLBC (b).

Both materials were also well described by the Elovich model (BC: R2 = 0.9586; BLBC: R2 = 0.9038). Notably, the α value for BLBC (555.64) was substantially higher than that for BC (78.17), reflecting a marked increase in surface active sites and initial adsorption rate after bacterial modification. This enhancement can be attributed to the increased specific surface area and additional functional groups introduced via microbial loading.

The intra-particle diffusion model fitting lines did not pass through the origin for either material, indicating that intra-particle diffusion was not the sole rate-limiting step. Instead, the adsorption process was jointly controlled by boundary layer diffusion and intra-particle transport, with the larger intercept C value for BLBC (22.55) suggesting a greater influence of surface or film diffusion, likely due to its more complex pore structure and stronger surface affinity.

The adsorption isotherm data of BLBC were further analyzed using Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) models (Table 1 and Figure 6). The Langmuir model achieved the highest fitting accuracy (R2 = 0.9742). Although the Langmuir model assumes a homogeneous surface with identical adsorption sites, its excellent fit here suggests that within the studied concentration range, Cd(II) adsorption on the inherently heterogeneous BLBC surface is effectively dominated by a monolayer coverage on a set of sites with relatively uniform and high affinity. This is plausible as bacterial loading likely introduces a dominant class of specific functional groups (e.g., −COOH, −OH) that act as primary binding sites for Cd(II) [33]. The maximum adsorption capacity (Qmax) derived from the Langmuir model was 44.17 mg/g, which was close to the theoretical saturation capacity (QDR = 36.03 mg/g) estimated from the D–R model, confirming the stable structure and high adsorption potential of BLBC. The good fit with the Temkin model (R2 = 0.9438) further verified the involvement of chemical interactions during adsorption. The Freundlich isotherm also showed acceptable correlation (R2 = 0.9102), with 1/n = 0.361 (<1), indicating a favorable adsorption process as well as the presence of some surface heterogeneity.

Figure 6.

Adsorption isotherm model fitting for BLBC.

In summary, the adsorption of Cd(II) onto both BC and BLBC is predominantly a chemisorption-driven process, as evidenced by the strong fits to the pseudo-second-order kinetic and Temkin isotherm models. The remarkable increase in the Elovich α value and the Langmuir Qmax for BLBC, compared to BC, underscores the critical role of bacterial loading in creating more abundant and effective adsorption sites. Although the surface is heterogeneous, the Langmuir model’s fit indicates that a specific type of high-affinity site (likely bacterial-derived functional groups) governs the monolayer adsorption under the experimental conditions. BLBC exhibits significantly improved adsorption capacity and kinetics compared to BC, attributable to the increased active sites, optimized pore structure, and enriched surface functional groups resulting from bacterial loading.

To better contextualize the performance of the BLBC material prepared in this study, Table 2 summarizes the adsorption capacities for Cd(II) in aqueous solution reported in recent years for various types of adsorbents. As shown, the adsorption capacity of pristine wheat straw biochar (BC, 20.5 mg/g) falls within the typical range for similar raw material biochars. After modification via loading with the Mn-oxidizing bacterium (Priestia sp. Z-MLHA-1), the maximum adsorption capacity of BLBC (44.17 mg/g) was significantly enhanced. This performance is not only superior to many physically/chemically modified biochars but also comparable to some complex composites and commercial adsorbents. It is noteworthy that the preparation of BLBC requires no expensive or toxic chemical modifiers, relying primarily on an environmentally benign biological modification process, highlighting its potential as a green adsorbent. Compared to other bacteria-loaded biochars, the unique bacterial strain and preparation method employed in this work also demonstrate competitive adsorption performance. This comparison indicates that the BLBC successfully developed in this study achieves a favorable balance among adsorption performance, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness.

Table 2.

Comparison of adsorption properties of different adsorbents for Cd(II) in aqueous solution.

3.4. Possible Mechanisms

The absence of any new crystalline phases in the XRD pattern after Cd(II) adsorption (Figure 7a) is a critical finding. It rules out the precipitation of crystalline cadmium compounds (e.g., CdCO3, Cd(OH)2) as a major immobilization pathway. This strongly suggests that Cd(II) is retained through non-precipitative, surface-mediated interactions that do not alter the long-range structural order of the BLBC matrix, aligning with the chemisorption-dominated mechanisms indicated by the kinetic and isotherm models. The BLBC was primarily composed of amorphous carbon, as evidenced by a broad diffraction peak centered at approximately 23° (2θ), which is characteristic of a disordered carbon structure. A distinct diffraction peak at 26.5° (2θ) was identified as quartz (SiO2), originating from inherent mineral impurities in the biomass feedstock. This predominantly amorphous framework provides a high specific surface area conducive to heavy metal adsorption. After Cd(II) adsorption, the XRD pattern showed no significant changes: all peak positions remained unshifted, and no diffraction signals corresponding to crystalline cadmium-containing phases such as CdCO3 and Cd(OH)2 were detected. These results, combined with the fact that adsorption was conducted at pH 7.20 (where Cd2+ is the predominant species), strongly suggest that Cd(II) immobilization did not proceed through precipitation or crystallization pathways, but rather through surface-mediated interactions that did not alter the long-range structural order of the material.

Figure 7.

XRD (a) and FTIR spectra (b) of BLBC before and after Cd(II) adsorption.

Changes in the surface functional groups of BLBC before and after Cd(II) adsorption were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Figure 7b). A broad absorption band around 3400 cm−1, attributed to −OH stretching vibrations, exhibited a slight blue shift and narrowing after adsorption. This shift reflects a change in the chemical environment of hydroxyl groups and an increase in the bond force constant, consistent with coordination between Cd(II) and oxygen/nitrogen atoms in hydroxyl or amino groups, leading to inner-sphere complex formation [38]. The intensity of peaks at 2920 cm−1 and 2850 cm−1, assigned to C–H stretching vibrations in –CH2/–CH3 groups from residual bacterial organics, decreased after adsorption, suggesting the involvement of aliphatic organic components in Cd(II) binding. The absorption band near 1620 cm−1, associated with aromatic C=C stretching and/or H-O-H bending of adsorbed water, also showed noticeable intensity changes, indicating interactions between Cd(II) and the carbon skeleton. More importantly, the broad region between 1000 and 1100 cm−1, which encompasses vibrations of C–O (in carboxylates, alcohols), Si–O–Si, and potentially P–O (from bacterial phosphate groups), displayed clear alterations after adsorption [39]. This provides direct spectroscopic evidence that oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., −COOH, −OH) serve as the primary binding sites for Cd(II) via surface complexation. Collectively, the FTIR analysis confirms that hydroxyl, carboxyl, and aromatic carbon structures serve as the primary functional groups responsible for Cd(II) immobilization on BLBC.

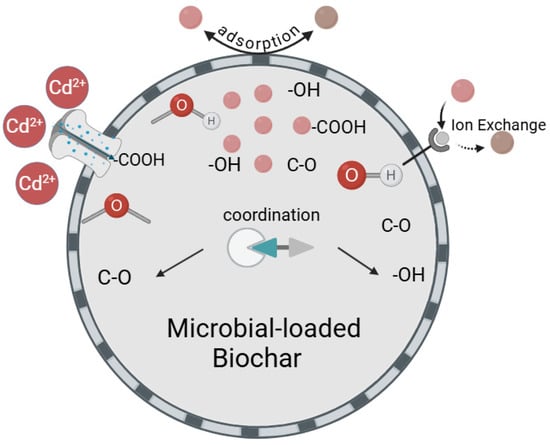

Scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) was employed to examine the surface morphology and elemental distribution of BLBC after Cd(II) adsorption (Figure 8). The sample exhibited irregular flakes and particles with a rough surface and clearly visible micropores/terraces, which provide abundant exposed sites for adsorption. The EDS spectrum (Figure 8a) confirmed that the material was mainly composed of C and O, with a distinct peak corresponding to Cd. The mass fractions were determined as C: 74.08%, O: 24.52%, and Cd: 1.40%, confirming the successful uptake of Cd(II). Elemental mapping (Figure 8c–e) revealed a continuous distribution of C and O across the observed area. The Cd signal was uniformly dispersed without localized agglomeration, which is a strong indication that Cd(II) was not retained as large precipitate particles but was homogeneously immobilized at multiple surface-active sites through mechanisms like complexation or ion exchange Combined with the FTIR and XRD results, it can be inferred that Cd(II) primarily interacts with oxygen-containing functional groups such as –OH, –COOH, and C–O as well as potentially with exchangeable cations (e.g., K+, Ca2+) on the BLBC surface, leading to effective immobilization via a combination of surface complexation and ion exchange. A schematic diagram summarizing the proposed Cd(II) immobilization mechanisms by BLBC, including surface complexation, ion exchange, and potential π-electron coordination, is provided in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

SEM and EDS mapping results of bacteria-loaded biochar after adsorption of Cd(II): EDS spectrum (a), SEM image (b), Elemental mapping of C (c), O (d), and Cd (e). Note: The elemental map for silicon (Si) is not presented here. The presence of SiO2 is identified by XRD (Figure 3a and Figure 7a).

Figure 9.

The adsorption mechanism of Cd in water by BLBC.

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of BLBC for Cd(II) immobilization; however, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Although a direct comparison between BLBC and pristine BC was conducted to highlight the effect of bacterial modification, a blank control (Cd(II) solution without adsorbent) was not included in the experimental design. The absence of a blank control limits the precise quantification of potential Cd(II) loss due to non-adsorbent factors such as container wall adsorption. Nevertheless, given the relatively low Cd(II) concentrations and short duration of the batch experiments, such losses are expected to be minimal and unlikely to affect the comparative conclusions between BC and BLBC. Future work will incorporate blank controls and further explore the long-term stability, regeneration potential, and performance of BLBC in real contaminated water systems to advance its practical application.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully prepared bacteria-loaded biochar (BLBC) by immobilizing the strain Priestia sp. Z-MLHA-1 onto wheat straw biochar and systematically evaluated its performance in Cd(II) removal from aqueous solution. The composite exhibited excellent adsorption capability, with a maximum Cd(II) uptake capacity of 44.17 mg/g. The adsorption process was best described by the Langmuir isotherm and the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. While the BLBC surface is inherently heterogeneous, the excellent fit to the Langmuir model suggests that within the studied concentration range, monolayer adsorption was effectively governed by a set of high-affinity sites with relatively uniform energy, likely the bacterial-derived functional groups. The strong conformity to the pseudo-second-order model, along with the good fit of the Temkin isotherm, underscores that chemisorption (e.g., surface complexation) is the dominant mechanism. Characterization analyses revealed that bacterial loading significantly enhanced the specific surface area of biochar from 41.48 m2/g to 58.06 m2/g and optimized its pore structure. Notably, the Elovich model parameter α for BLBC was substantially higher than for BC, reflecting a marked increase in active site density and initial adsorption rate due to bacterial modification. FTIR and XRD analyses confirmed the presence of functional groups such as −OH and −COOH, which played a critical role in Cd(II) complexation. Mechanistic studies revealed that under near-neutral pH conditions, Cd(II) was immobilized primarily as Cd2+. The superior immobilization performance of BLBC for Cd(II) is attributed to the synergy between surface complexation mediated by its abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (−OH, −COOH) and potential ion exchange processes. Post-adsorption XRD patterns showed no crystalline cadmium-containing phases, and SEM-EDS mapping revealed a uniform distribution of Cd on the adsorbent surface, indicating that immobilization occurred mainly through surface complexation and ion exchange rather than precipitation.

In summary, the organic-inorganic hybrid structure of BLBC enhances the availability of adsorption sites and improves surface reactivity, resulting in a synergistic effect that boosts Cd(II) immobilization. These findings demonstrate that BLBC is a promising green and efficient adsorbent with strong potential for practical application in the remediation of Cd(II)-contaminated water.

Author Contributions

F.J.: conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, writing—original draft. Y.W. (Yuyong Wu): investigation. G.H.: investigation. D.L.: investigation. Y.W. (Yang Wang): investigation. S.Z.: investigation. K.Y.: investigation. C.Y.: investigation. X.Z.: writing—review & editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by Shijiazhuang Major Science and Technology Special Project (246241567A), Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2024JC-YBQN-0255), and the Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education Project (23JK0364).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Fanfan Ju, Yuyong Wu, Guilei Han, Dajin Liu and Yang Wang were employed by North China Engineering Investigation Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Liu, B.; Chen, T.; Wang, B.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Pan, X.; Wang, N. Enhanced removal of Cd2+ from water by AHP-pretreated biochar: Adsorption performance and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, J.; Ali, N.; Dong, Y.; Ahmad, U.; Anjum, M.M.; Khan, G.R.; Zaib, M.; Jalal, A.; Ali, R.; Ali, L. Biochar-based adsorption for heavy metal removal in water: A sustainable and cost-effective approach. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltcheva, M.; Tzvetanova, Y.; Ostoich, P.; Aleksieva, I.; Chassovnikarova, T.; Tsvetanova, L.; Rusew, R. Oral Supplementation with Modified Natural Clinoptilolite Protects Against Cadmium Toxicity in ICR (CD-1) Mice. Toxics 2025, 13, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gan, X.; Tang, Y. Mechanisms of heavy metal cadmium (Cd)-induced malignancy. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Ruan, Z.; Yin, Y.; Hu, C.; Tian, L.; Lu, J.N.; Wang, S.; Tang, Y.T.; Qiu, R.; Chao, Y. Keystone species in microbial communities: From discovery to soil heavy metal-remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.T.; Zhao, H.P. Sulfate-driven microbial collaboration for synergistic remediation of chloroethene-heavy metal pollution. Water Res. 2025, 268, 122738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, B.; Imran, M.; Naeem, A.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Arshad, H.; Hussain, A.; Zulfiqar, U.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Prasad, P.V.; Djalovic, I. Adsorptive removal of lead from wastewater using pressmud with evaluation of kinetics and adsorption isotherms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, J.; Miao, L.; Lin, Z.; Sun, J.; Yan, H.; Ying, Y.; Wu, Z.; Song, W.; Lv, W.; Song, C.; et al. Separation and reutilization of heavy metal ions in wastewater assisted by p-BN adsorbent. Chemosphere 2024, 354, 141737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Sgarbossa, P.; Gelosa, S.; Copelli, S.; Sieni, E.; Barozzi, M. Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions on Alginate-Based Magnetic Nanocomposite Adsorbent Beads. Materials 2024, 17, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, L.; Rahimi, G. The efficiency of potato peel biochar for the adsorption and immobilization of heavy metals in contaminated soil. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2023, 25, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Yao, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Xian, J.; Wang, Y. Recent advance on application of biochar in remediation of heavy metal contaminated soil: Emphasis on reaction factor, immobilization mechanism and functional modification. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Du, B.; Zhou, J.; Ji, D. Effects of Pyrolysis Temperatures and Modified Methods on Rice Husk-Derived Biochar Characteristics and Heavy Metal Adsorption. Molecules 2025, 30, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, E.; Lewys-James, A.; Ravella, S.R.; Thomas-Jones, S.; Perkins, W.; Gallagher, J. Optimisation of slow-pyrolysis process conditions to maximise char yield and heavy metal adsorption of biochar produced from different feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Meng, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z. Roles of naturally occurring biogenic iron-manganese oxides (BFMO) in PMS-based environmental remediation: A complete electron transfer pathway. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 155, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhiwen, L.; Ruiyan, N.; Jiaheng, Y.; Liyun, Y.; Di, C. Removal of cadmium from aqueous solution by magnetic biochar: Adsorption characteristics and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 6543–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Shan, D.; He, J.; Huang, T.; Mao, Y.; Tan, H.; Shi, H.; Li, T.; Xie, T. Effects and mechanism on cadmium adsorption removal by CaCl 2-modified biochar from selenium-rich straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, X.; Xu, T.; Chu, S.; Wang, H.; Jiang, K. Removal of Pb (II) and Cd (II) from a monometallic contaminated solution by modified biochar-immobilized bacterial microspheres. Molecules 2024, 29, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Gao, H.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Hua, L.; Jia, H. The potential effectiveness of mixed bacteria-loaded biochar/activated carbon to remediate Cd, Pb co-contaminated soil and improve the performance of pakchoi plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 435, 129006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Aniagor, C.O.; Fikry, M.; Taha, G.M.; Badawy, S.M. Characterization and adsorption of raw pomegranate peel powder for lead (II) ions removal. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, X.; Li, Y.; Han, L. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and correlation analysis on the yield and physicochemical properties of crop residue biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 296, 122318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, B.; Tan, R.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M. Detecting pore size distribution of activated carbon by low-field nuclear magnetic resonance. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2022, 60, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xie, R.; Chen, Y.; Pu, X.; Jiang, W.; Yao, L. A novel mesoporous zeolite-activated carbon composite as an effective adsorbent for removal of ammonia-nitrogen and methylene blue from aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 268, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmani, R.; Yılmaz, M.; Benaoune, S.; Di Palma, L. Optimized pyrolytic synthesis and physicochemical characterization of date palm seed biochar: Unveiling a sustainable adsorbent for environmental remediation applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 60065–60079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, L.F.; Herrera, K.; López, J.E.; Saldarriaga, J.F. Use of biochar from rice husk pyrolysis: Assessment of reactivity in lime pastes. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yin, H.; Wei, X.; Dang, Z. Functional bacterial consortium responses to biochar and implications for BDE-47 transformation: Performance, metabolism, community assembly and microbial interaction. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, H.; Wu, T.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Ji, X.; Fan, H.; Song, H. Improvement of interface bonding of bacterial cellulose reinforced aged paper by amino-silanization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, B. Effect of biochar-doped rare earth tailing on soil properties and plant growth in reclaimed shale gas sites. Environ. Technol. 2025, 46, 5739–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Hong, J.; Xie, H.; Lin, X. Facile Recycling of Waste Biomass for Preparation of Hierarchical Porous Carbon with High-Performance Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. Molecules 2024, 29, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.R.; Luna, C.M.R.; Arce, G.L.; Ávila, I. Optimization of slow pyrolysis process parameters using a fixed bed reactor for biochar yield from rice husk. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 132, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Song, Z.; Cao, C.; Tang, C. Preparation of Poly (allylamine Hydrochloride) Grafted Porous Boron Nitride Fibers for Efficient Cr (VI) Adsorption from Aqueous Solution. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidi, M.; Reguig, B.A.; El Amine Monir, M.; Althagafi, T.M.; Fatmi, M.; Remil, A.; Zehhaf, A.; Ghebouli, M.A. Kinetics thermodynamics and adsorption study of raw treated diatomite as a sustainable adsorbent for crystal violet dye. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Du, R.; Wen, S.; Du, L.; Tu, Q. Adsorption of Cd2+ by Lactobacillus Plantarum immobilized on distiller’s grains biochar: Mechanism and action. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Tang, Y.; Li, C.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Feng, C.; Zhao, W.; Wang, F. Adsorption and sequestration of cadmium ions by polyptychial mesoporous biochar derived from Bacillus sp. biomass. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 23505–23523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiusheng, Y.; Peifang, W.; Xun, W.; Bin, H.; Chao, W. Nano-chlorapatite modification enhancing cadmium (II) adsorption capacity of crop residue biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 161097. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, C.; Qin, L.; Xie, M.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Y. Efficient adsorption capacity of MgFe-layered double hydroxide loaded on pomelo peel biochar for Cd (II) from aqueous solutions: Adsorption behaviour and mechanism. Molecules 2023, 28, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Saffian, H.; Hyun-Joong, K.; Md Tahir, P.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, C.H. Effect of lignin modification on properties of kenaf core fiber reinforced poly (butylene succinate) biocomposites. Materials 2019, 12, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, M.A.; Watson, J.S.; Tan, J.S.; Sephton, M.A. Biochar Stability Revealed by FTIR and Machine Learning. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2025, 2, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.