Abstract

Single-atom catalysts are highly efficient electrocatalysts for water splitting with exceptional atomic utilization, but atomic aggregation can impair their catalytic performance. To address this challenge, a Fe-Co-Ni single-atom bifunctional catalyst supported on nitrogen-doped graphene oxide was designed and employed for overall water splitting in alkaline electrolyte. The catalyst’s composition, structure, and morphology were systematically characterized using XRD, XPS, SEM, and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). Electrochemical evaluations were performed to assess its activity and stability toward both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER). The results demonstrate that strong metal-nonmetal interactions between the Fe, Co and Ni single atoms and the nitrogen-doped graphene oxide support facilitate stable and uniform anchoring of the metal centers on the wrinkled carbon framework. The total metal loading reaches approximately 6.78 wt%, ensuring a high density of accessible active sites. Furthermore, synergistic electronic coupling among the Fe, Co, and Ni centers enhances charge transfer kinetics and modulates the D-band electronic states of the metal atoms. This effect weakens the adsorption strength of hydrogen and oxygen-containing intermediates, thus promoting faster reaction kinetics for both HER and OER. Consequently, the FeCoNi/CNG catalyst delivers low overpotentials of 77 mV for HER and 355 mV for OER at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 in alkaline conditions. When integrated into an alkaline water electrolyzer, the system achieves a cell voltage of only 1.68 V to attain a current density of 10 mA cm−2, underscoring its outstanding bifunctional catalytic performance.

1. Introduction

The excessive consumption of conventional fossil fuels has resulted in severe energy shortages and widespread environmental pollution, driving global efforts to pursue sustainable energy alternatives. In the context of sustainable development, the limited availability of traditional energy resources, coupled with growing ecological concerns, has intensified the demand for innovative green technologies for energy production [1]. Hydrogen, widely recognized as a clean and environmentally benign energy carrier with high energy density, is regarded as a promising substitute for fossil fuels [2]. Electrocatalytic water splitting has emerged as a promising technology for sustainable hydrogen production, enabling efficient conversion of electrical energy into chemical energy stored in hydrogen bonds. This process provides a viable pathway for large-scale storage and utilization of intermittent renewable energy. The overall reaction comprises two coupled electrochemical processes: the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at the cathode and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode. However, both these half-reactions involve multi-step proton-coupled electron transfer processes, which present high kinetic energy barriers and result in significant reaction overpotentials. This process is further influenced by the adsorption energies of key intermediates and the electronic structure of the electrocatalyst [3,4]. In acidic media, the HER proceeds via either the Volmer-Heyrovsky or Volmer-Tafel pathway, whereas in alkaline conditions, the water dissociation step introduces an additional energy barrier [5,6]. In both acidic and alkaline environments, the OER follows mechanisms such as the Adsorbate Evolution Mechanism (AEM) or the Lattice Oxygen Mechanism (LOM), which are constrained by the scaling relationships between the formation and adsorption energies of key intermediates [7]. To overcome these energy barriers and improve the thermodynamic efficiency of water electrolysis, developing advanced electrocatalysts is essential [8,9,10]. Currently, noble metal-based materials, particularly platinum for HER and ruthenium/iridium oxides for OER, continue to serve as benchmark catalysts owing to their exceptional activity and stability. However, its high cost and limited natural abundance pose significant challenges for the large-scale implementation of electrolytic hydrogen production. Consequently, the development of efficient and stable non-precious metal catalysts for the HER and OER is crucial to advancing water electrolysis for hydrogen production.

Transition metal single-atom catalysts (SACs) have attracted considerable research interest due to their broad elemental diversity, distinctive electronic properties, and relatively low cost [3,11]. The catalytic performance of SACs is primarily governed by the chemical bonding interactions between isolated metal atoms and the support, as well as the interfacial charge transfer dynamics. Compared to monometallic SACs, binary or ternary SACs exhibit increasingly evident performance advantages. Well-defined metal-support interfaces and intermetallic synergistic effects can significantly enhance catalytic activity and enable multifunctional capabilities [12]. As a representative case, Liu et al. [13] developed a Fe–Cu diatomic catalyst supported on nitrogen-doped porous carbon (FeCu SACs/NC). Compared to the monometallic analogs (Fe SACs/NC and Cu SACs/NC), the bimetallic system displayed improved oxygen reduction performance in acidic electrolyte, manifesting as a positively shifted half-wave potential (0.75 V) and an increased kinetic current density (7.27 mA cm−2). Theoretical calculations verified that copper incorporation enables electronic modulation of the iron centers, effectively lowering the activation barrier for the oxygen reduction reaction. In another study, Da et al. [14] constructed a Pt–Ni bimetallic catalyst anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon (PtNi–NC) through atomic layer deposition. This heteronuclear catalyst exhibited outstanding hydrogen evolution activity in acidic medium, achieving an ultralow overpotential of 30 mV at 10 mA cm−2 with a mass activity 21 times higher than commercial 20 wt% Pt/C, substantially exceeding the performance of its monometallic counterparts. Wan et al. [15] developed a carbon-supported Fe/Co/Ni bimetallic single-atom catalyst (Tan–CN–CoFe/NiFe). The bimetallic system displayed superior OER performance in alkaline media, exhibiting substantially lower overpotentials (down to 320 mV), higher turnover frequencies (up to 5.2 s−1), and reduced Tafel slopes (as low as 58 mV dec−1) relative to their monometallic analogs (Tan–CN–Fe, –Co, or –Ni). Zhang et al. [16] constructed a Pt–Fe–Co ternary single-atom catalyst anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon nanospheres derived from a covalent organic framework. Electrochemical characterization showed that this ternary catalyst achieves a half-wave potential (E1/2) of 0.845 V in alkaline media, outperforming both the monometallic Pt/N–C (0.79 V) and bimetallic Fe,Co/N–C (0.81 V) catalysts. This enhancement is attributed to the synergistic modulation of the Pt D-band center by Fe and Co. While traditional single-atom catalysts possess well-defined active sites and high atom utilization efficiency, their spatially isolated single-site configuration restricts synergistic interactions between adjacent metal sites, leading to insufficient electronic coupling and creating bottlenecks for further enhancing catalytic activity. Therefore, this study investigates FeCoNi-coupled single-atom catalysts, which maintain atomic dispersion while effectively modulating the d-band electronic structure and local coordination environment of active sites. This dual modulation enhances the intrinsic activity of each metal site and optimizes the adsorption behavior of hydrogen/oxygen-containing intermediates during both the HER and OER. Consequently, the rational design of synthesis pathways and optimization of support structures to precisely control the content, atomic-level distribution, and chemical valence states of multiple metallic elements are of paramount importance for developing high-performance non-precious metal catalysts.

In carbon-supported transition metals, metal atoms possess high surface energy, which poses significant challenges to achieving stable dispersion and strong anchoring on the carbon matrix. A widely employed strategy to mitigate this issue is the construction of coordination structures between the metal and nitrogen atoms. Nitrogen species introduced into the carbon framework can coordinate with the d-orbitals of transition metals through their lone-pair electrons, thereby enhancing the metal-support interaction and effectively preventing metal atom agglomeration. Consequently, nitrogen doping has become a prevalent approach in various carbon-based supports, such as graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes, biochar, and metal–organic framework (MOF)-derived carbons, for the rational design of metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) active sites, enabling the development of structurally robust SACs with superior electrochemical performance [17,18,19]. Among these supports, GO exhibits a high specific surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, favorable chemical stability, and outstanding dispersibility, rendering it a particularly promising candidate for hosting isolated metal atoms [20].

In this study, a ternary Fe–Co–Ni single-atom catalyst anchored on nitrogen-doped graphene (FeCoNi/CNG) was successfully synthesized via an impregnation-negative pressure pyrolysis method. This approach enables complete adsorption of metal precursors within the porous support, thereby facilitating the formation of atomically dispersed active sites during subsequent pyrolysis. Fe, Co, and Ni were selected as the transition metal components owing to their low cost and tunable d-electron configurations. The cooperative electronic coupling among the metallic components enables precise optimization of adsorption energetics for critical reaction intermediates, leading to enhanced electrocatalytic efficiency. The crystal phase, morphology, and atomic-level dispersion of the material were investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) investigations provided evidence of intermetallic charge redistribution and corresponding electronic structure modifications. Comprehensive electrochemical assessment demonstrated exceptional performance across HER, OER, and overall water splitting metrics. Practical validation was further conducted through assembly of an alkaline electrolyzer, which confirmed sustained operational stability under technologically relevant conditions. This work not only provides fundamental guidance for the rational design of SACs but also establishes a valuable framework for the development of efficient and low-cost electrocatalysts for water splitting, thereby contributing to the advancement of renewable energy conversion technologies.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of FeCoNi/CNG Catalysts

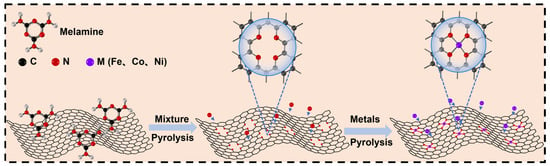

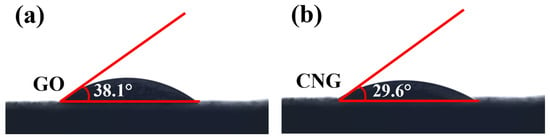

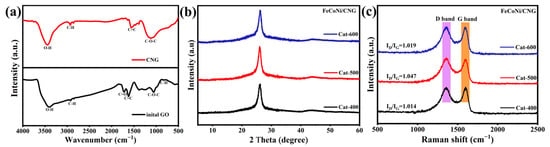

The synthesis procedure of the FeCoNi/CNG electrocatalyst is illustrated in Figure 1. In brief, graphene oxide and melamine were mixed at a mass ratio of 1:5 and subjected to a nitridation treatment. Subsequently, iron-cobalt-nickel nitrate was employed to modify the carbon nitride material through a negative-pressure impregnation pyrolysis approach, producing uniformly dispersed FeCoNi/CNG SACs [21]. Surface wettability analysis presented in Figure 2a,b reveals that the water contact angle of the melamine-derived CNG support is 27°, substantially lower than that of pristine graphene oxide (42°). This enhanced hydrophilicity is attributed to nitrogen doping, which incorporated polar nitrogen-containing functional groups. The FT-IR spectrum in Figure 3a demonstrates that during the nitridation of graphene oxide with melamine, melamine acts as both a reducing agent and a nitrogen source, leading to the reduction of graphene oxide and a consequent decrease in oxygen-containing functional groups within the resulting CNG. This reductive transformation, coupled with nitrogen doping, effectively creates catalytically active sites and enhances the electrical conductivity of the material [22]. Figure 3b displays the XRD patterns of FeCoNi/CNG catalysts pyrolyzed at 400 °C, 500 °C, and 600 °C. Two characteristic diffraction peaks at approximately 26.3° and 43.9° are assigned to the (002) and (101) crystal planes of graphitic carbon [23], confirming the predominantly amorphous nature of the carbon-based matrix. No diffraction peaks corresponding to metallic Fe, Co, Ni, or their crystalline compounds were detected, indicating that the metal species remained below the XRD detection limit and were atomically dispersed without forming metallic nanoparticles. Raman spectra (Figure 3c) reveal distinct D band (1357 cm−1) and G band (1589 cm−1) features for FeCoNi/CNG samples prepared at 400 °C, 500 °C, and 600 °C. The intensity ratio of the D band to the G band increases with pyrolysis temperature: ID/IG = 1.014 for Cat-400, 1.047 for Cat-500, and 1.090 for Cat-600. This trend indicates that as the pyrolysis temperature increases from 400 °C to 500 °C, the thermal migration and dispersion of metal precursors on the support surface become more sufficient, potentially leading to the formation of coordination structures represented by M–Nx, which contribute to an increased degree of defects [21,24]. When the temperature rises to 600 °C, the ID/IG ratio decreases, which may be attributed to the rearrangement of carbon atoms in the support at elevated temperatures, resulting in the repair of some defects. Additionally, ICP-OES analysis confirmed that Cat-500 exhibits a high total metal loading of 6.78 wt%, with individual contents of Fe, Co, and Ni quantified as 2.14 wt%, 2.34 wt%, and 2.30 wt%, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis process for the FeCoNi/CNG catalyst.

Figure 2.

Water contact angle of (a) GO and (b) CNG.

Figure 3.

(a) FT-IR spectra of graphene oxide and CNG; (b) XRD patterns and (c) Raman spectra of FeCoNi/CNG synthesized at 400 °C, 500 °C, and 600 °C.

Table 1.

Fe, Co, and Ni content in FeCoNi/CNG catalysts synthesized at 400, 500, and 600 °C.

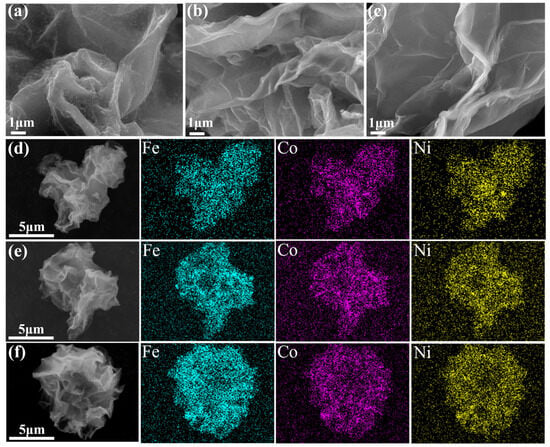

The morphology of the FeCoNi/CNG catalysts was characterized by SEM. As shown in Figure 4a–c all samples (Cat-400, Cat-500, and Cat-600) retained the characteristic multilayered wrinkled structure typical of graphene oxide. This indicates that the introduction of different metals and changes in pyrolysis temperature did not significantly alter the overall wrinkled morphology of the material. EDS analysis of the samples (Figure 4d–f) revealed the presence of Fe, Co, and Ni elements in Cat-400, Cat-500, and Cat-600, with no significant agglomeration of metal particles observed.

Figure 4.

SEM images (a–c) and the corresponding EDS spectra (d–f) of the FeCoNi/CNG catalyst synthesized at 400 °C, 500 °C, and 600 °C, respectively.

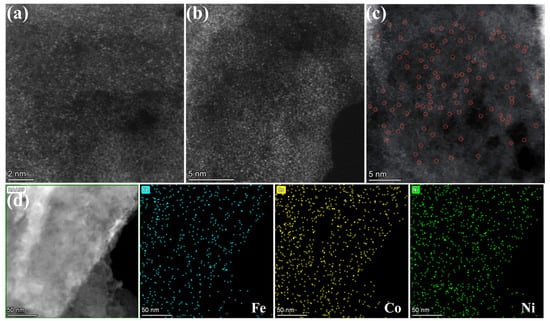

To further examine the spatial distribution of metallic elements, HAADF-STEM was conducted on the Cat-500 sample. Images acquired at 2 nm and 5 nm scales (Figure 5a–c) reveal a high density of bright spots corresponding to isolated metal atoms, providing direct evidence of atomic-level dispersion of Fe, Co, and Ni species. The absence of nanoparticles or metal clusters further corroborates the highly dispersed nature of the metal centers. Elemental mapping (Figure 5d) confirms the uniform spatial distribution of Fe, Co, and Ni across the carbon support.

Figure 5.

Microstructure and atomic-level characterization of the Cat-500 catalyst: (a–c) HAADF-STEM images; (d) HAADF-STEM elemental mapping.

2.2. Electronic Structure Analysis of FeCoNi/CNG

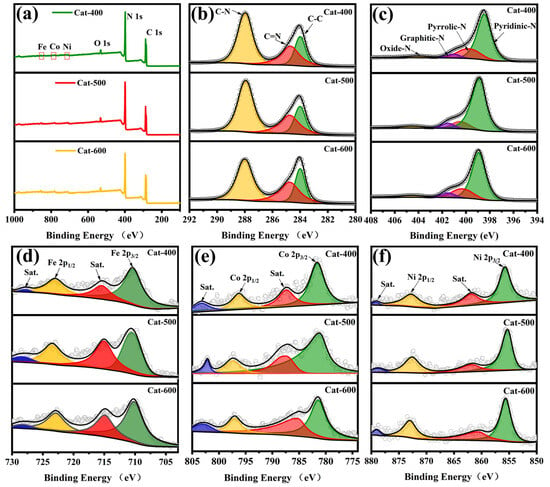

XPS analysis was employed to investigate the elemental composition and oxidation states of the FeCoNi/CNG catalyst. The XPS survey scan (Figure 6a) clearly identifies the characteristic peaks of C, N, O, Fe, Co, and Ni, aligning with the elemental distribution revealed by HAADF-STEM mapping. Deconvolution of the high-resolution C 1s spectrum (Figure 6b) displays three distinct components with binding energies centered at approximately 284.0 eV, 284.8 eV, and 288.0 eV, which are assigned to C–C, C–N, and C=N bonds, respectively. The notable presence of C–N bonding configurations confirms effective nitrogen doping within the carbon matrix.

Figure 6.

XPS analysis of the FeCoNi/CNG catalyst: (a) wide-scan survey spectrum and (b–f) corresponding high-resolution spectra of C 1s, N 1s, Fe 2p, Co 2p, and Ni 2p.

Structural and electronic modulation of nitrogen-doped carbon materials occurs through two synergistic mechanisms: (1) the slight difference in atomic radii between N (0.75 Å) and C (0.77 Å) induces bond length mismatch between C–N (1.41 Å) and C–C (1.42 Å), resulting in lattice distortion and defect formation; (2) the higher electronegativity of nitrogen (3.04) compared to carbon (2.55) drives charge redistribution within the sp2-hybridized carbon network, disrupting its intrinsic electron neutrality [25,26]. This combined defect engineering and electronic modulation synergistically reconstructs the catalyst’s electronic structure, thereby optimizing the adsorption/desorption kinetics of hydrogen intermediates (H*) and enhancing hydrogen evolution performance [27]. Analysis of the C 1s spectra further reveals the influence of pyrolysis temperature on nitrogen configuration and the carbon matrix (Table 2). Cat-500 exhibits the most favorable chemical environment: the highest proportion of C=N bonds (51.25%) provides abundant nitrogen sources for metal coordination; a relatively high C–N content (26.24%) reflects effective nitrogen doping; and the lowest C–C ratio (22.51%) indicates a defect-rich carbon framework conducive to stabilizing single atoms. In contrast, Cat-600 suffers from significant nitrogen loss and excessive graphitization, while Cat-400 displays an underdeveloped carbon structure. Therefore, Cat-500 achieves the highest density of single-atom sites and optimal catalytic performance by balancing nitrogen doping and defect concentration.

Table 2.

XPS fitting results of the C 1s spectrum for FeCoNi/CNG.

The high-resolution N 1s spectra (Figure 6c) were deconvoluted into four components: pyridinic N (398.4 eV), pyrrolic N (399.6 eV), graphitic N (401.1 eV), and oxidized N (404.3 eV) [28,29,30]. The distribution of nitrogen species is dependent on pyrolysis temperature (Table 3). Cat-500 exhibits the highest pyridinic N content (75.9%), significantly exceeding that of Cat-400 (67.15%) and Cat-600 (68.09%), indicating its superior ability to form metal anchoring sites. In contrast, Cat-600 exhibits the lowest proportion of pyrrolic N (11.36%), indicating that elevated pyrolysis temperatures facilitate the progressive conversion of less stable pyrrolic configurations into more thermally robust pyridinic and graphitic nitrogen species. This thermal transformation effectively enhances the nitrogen coordination environment within the carbon matrix. The high-resolution Fe 2p spectrum (Figure 6d) exclusively presents characteristic peaks corresponding to Fe2+ and Fe3+ oxidation states, with no detectable metallic Fe phase, confirming the successful formation of mixed-valence iron species with coordinated chemical states [31]. Similarly, the Co 2p spectrum (Figure 6e) indicates that cobalt exists in oxidized forms (Co2+ and Co3+) [32], and the Ni 2p spectrum (Figure 6f) confirms the presence of Ni2+ and Ni3+. These findings collectively confirm the atomic dispersion of Fe, Co, and Ni within the nitrogen-doped carbon matrix, stabilized through typical M–N (M = Fe, Co, Ni) coordination environments [33].

Table 3.

XPS fitting results of the N 1s spectra for FeCoNi/CNG.

2.3. Electrochemical Activity Evaluation

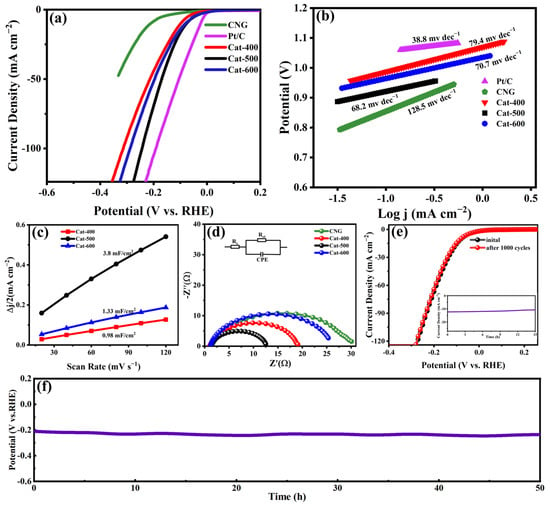

The HER activities of the FeCoNi/CNG catalysts were systematically assessed in N2-saturated 1.0 M KOH electrolyte using a conventional three-electrode configuration. A SCE and graphite rod served as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively, with all potentials calibrated to the RHE scale. For performance comparison, CNG, Cat-400, Cat-500, Cat-600, and commercial Pt/C (20 wt%) were examined under identical electrochemical conditions. Before electrochemical measurements, catalyst activation was achieved through continuous CV scanning until stable response profiles were obtained. LSV measurements were then conducted at a sweep rate of 5 mV s−1. As depicted in Figure 7a, Cat-500 exhibited a low overpotential of 77 mV to reach 10 mA cm−2, outperforming both Cat-400 (108 mV) and Cat-600 (82 mV). In contrast, the CNG support without Fe, Co, or Ni loading exhibited significantly inferior HER activity, highlighting the critical role of atomically dispersed Fe, Co, and Ni species as active sites in the HER process.

Figure 7.

Electrocatalytic HER performance of CNG, Cat-400, Cat-500, Cat-600, and Pt/C. (a) LSV polarization curves; (b) Corresponding Tafel plots; (c) Electrochemically active surface areas of the catalysts; (d) Nyquist plots of the catalysts; (e) Polarization curves of Cat-500 before and after 1000 CV cycles. The inset in panel (e) presents the long-term stability test of Cat-500 at a constant current density of 10 mA cm−2; (f) CP response profiles of Cat-500 recorded during the 50 h HER operation.

To elucidate the HER kinetics, Tafel analysis was employed based on the corresponding polarization curves. As presented in Figure 7b, the calculated Tafel slopes for Pt/C, Cat-400, Cat-500, and Cat-600 measured 38.8, 79.4, 68.2, and 70.7 mV dec−1, respectively. The Tafel values of Cat-400, Cat-500, and Cat-600, ranging between 40 and 120 mV dec−1, suggest a HER pathway following the Volmer-Heyrovsky mechanism where the electrochemical desorption step governs the overall reaction rate. The catalytic activity for HER is closely related to the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of the catalyst. The ECSA was calculated from the Cdl to specific capacitance (Cs) ratio, with Cs taken as 35 μF·cm−2 for planar electrodes in 1.0 M KOH solution [34,35]. As shown in Figure 7c, the ECSA of Cat-500 is 108.6 cm2, significantly higher than those of Cat-400 (38.0 cm2) and Cat-600 (28.0 cm2). These results indicate that the Cat-500 catalyst can provide more catalytic active sites, thereby facilitating the HER process.

Further investigation of electron transfer kinetics was conducted via EIS at an overpotential of 110 mV versus RHE. The Nyquist plots were fitted using an equivalent circuit model (inset of Figure 7d), where Rs represents the solution resistance and CPE denotes the constant phase element. The semicircle diameter in the high-frequency region corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (Rct), with a smaller diameter indicating faster electron transfer at the electrode surface. As shown in Figure 7d, the Rct values for Cat-400, Cat-500, and Cat-600 are 18.7, 12.4, and 25.3 Ω, respectively. This demonstrates that Cat-500 possesses superior charge transfer kinetics, which is beneficial for the HER.

Stability is a critical performance metric for electrocatalysts in the HER. The durability of the Cat-500 catalyst was systematically evaluated through continuous CV scanning, i–t, and CP measurements. As shown in Figure 7e, after 1000 CV cycles, the HER activity and current density exhibited negligible degradation. The i–t curve (inset, Figure 7e) further confirms excellent stability, with the current density remaining close to 10 mA cm−2 over 15 h of continuous operation at −0.087 V versus RHE. In addition, CP measurements conducted over 50 h revealed only a minor increase in overpotential, while the overall cell voltage remained stable (Figure 7f).

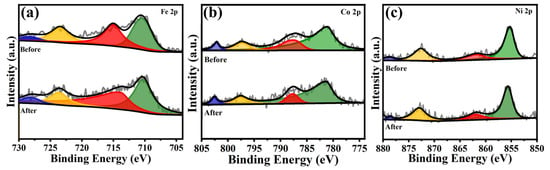

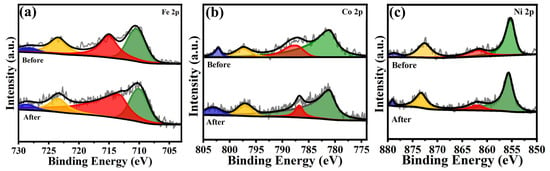

Figure 8 displays the XPS of Cat-500 before and after HER stability testing. It can be observed that the Fe 2p, Co 2p, and Ni 2p spectra show no significant changes during this process, indicating the relatively stable chemical states of the metal ions. These results collectively demonstrate the outstanding electrochemical stability of Cat-500, which can be attributed to the strong bonding interactions between the metal species and the nitrogen-doped carbon nanostructure support.

Figure 8.

XPS of Cat-500 before and after HER stability testing: (a) Fe 2p, (b) Co 2p, and (c) Ni 2p.

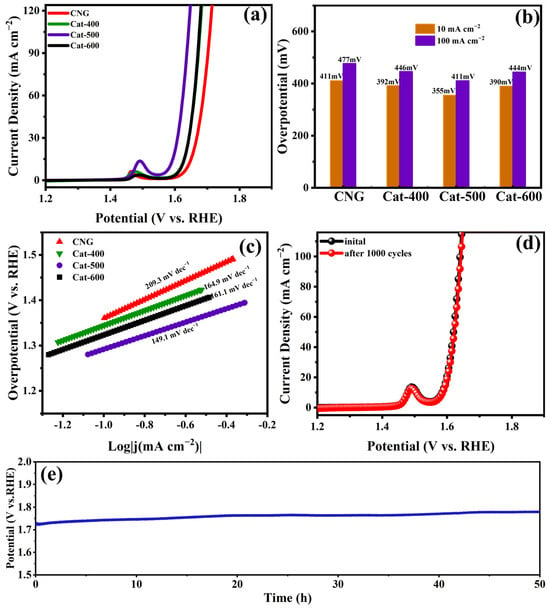

The OER performance of Cat-500 was comprehensively investigated in 1 M KOH electrolyte to evaluate its bifunctional electrocatalytic capability. As presented in Figure 9a, Cat-500 recorded a minimal overpotential of 355 mV at 10 mA cm−2, surpassing both Cat-400 (392 mV) and Cat-600 (390 mV) and confirming its enhanced OER activity. This performance superiority was amplified at elevated current densities (Figure 9b), where Cat-500 delivered 100 mA cm−2 at 411 mV, substantially below the values required by Cat-400 (446 mV) and Cat-600 (444 mV). Kinetic analysis through Tafel plots (Figure 9c) revealed that Cat-500 displays a slope of 149.1 mV dec−1, notably smaller than those of Cat-400 (164.9 mV dec−1) and Cat-600 (161.1 mV dec−1). The relatively large Tafel slope may be associated with the LOM or proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) processes. In the case of LOM, kinetic limitations could arise from the formation of oxygen vacancies or the dehydrogenation of M–OH. As for PCET, the kinetics are strongly influenced by the rate of proton transfer. Even if electron transfer is thermodynamically favorable, the overall PCET step can be hindered if water molecules or hydroxyl groups on the catalyst surface fail to efficiently accept or supply protons [36,37].

Figure 9.

Electrocatalytic OER performance of CNG, Cat-400, Cat-500, and Cat-600. (a) LSV polarization curves; (b) Overpotentials at representative current densities; (c) Corresponding Tafel plots; (d) Polarization curves of the Cat-500 electrocatalyst before and after 1000 CV cycles; (e) CP response profiles of Cat-500 recorded during the 50 h OER operation.

The operational stability of Cat-500 for OER was verified by the nearly identical LSV profiles before and after 1000 CV cycles (Figure 9d), indicating remarkable electrochemical durability. In Figure 9a,d, the electron transfer process observed around 1.5 V corresponds to the Ni2+/Ni3+ redox reaction [38,39]. Figure 9e presents the stability test results of Cat-500 at 10 mA cm−2, demonstrating that the catalyst’s overpotential remains essentially stable within the 50 h testing period.

Additionally, a comparison of the energy spectra of Cat-500 before and after the 50 h OER stability test (Figure 10) revealed no significant changes in the chemical states of Fe, Co, and Ni. This indicates that Cat-500 exhibits remarkable electrochemical durability during the OER process.

Figure 10.

XPS spectra of Cat-500 before and after OER stability testing: (a) Fe 2p, (b) Co 2p, and (c) Ni 2p.

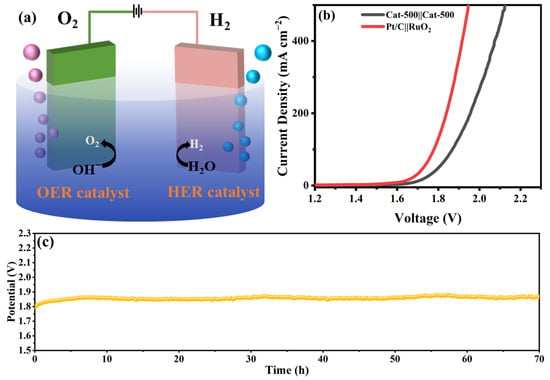

Building upon its exceptional dual-functionality for both HER and OER, a two-electrode configuration was constructed with Cat-500 functioning simultaneously as anode and cathode (designated as Cat-500(−)//Cat-500(+)) for overall water splitting (Figure 11a). Figure 11b shows the polarization curve of the Cat-500 catalyst for overall water splitting. In 1.0 M KOH solution, Cat-500||Cat-500 and Pt/C||RuO2 achieved overpotentials of 1.68 V and 1.63 V, respectively, at a current density of 10 mA cm−2, indicating the potential of Cat-500 for efficient water electrolysis applications. The stability of Cat-500||Cat-500 was evaluated by CP at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 (Figure 11c). No significant degradation in overpotential was observed after 70 h of testing, demonstrating the excellent overall water splitting stability of the catalyst.

Figure 11.

Test for Overall Water Splitting: (a) schematic illustration of overall water splitting using the Cat-500 catalyst, (b) polarization curves for overall water splitting, and (c) CP stability test under 10 mA cm−2.

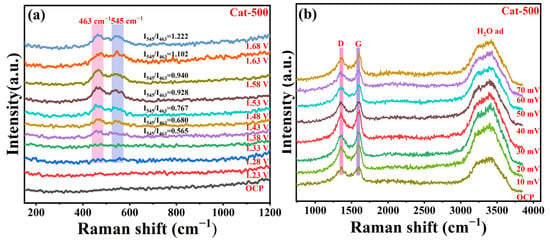

2.4. Catalytic Mechanism of Cat-500

To elucidate the role of ternary metal integration in Cat-500 in enhancing both the OER and HER, in situ Raman spectroscopy was employed to monitor reaction intermediates under operational conditions. Figure 12a presents the potential-dependent Raman spectra collected in 1.0 M KOH over a range from 0 to 1.68 V versus RHE. In situ Raman spectroscopic monitoring under open-circuit conditions revealed no distinct spectral features. However, with applied potential increasing to 1.38 V, spectral development became evident through two broad bands centered at 463 cm−1 and 545 cm−1, corresponding, respectively, to the M–O bending vibration in γ-MOOH and M–O stretching mode in β-MOOH (M = Fe/Co/Ni) [40,41,42]. Both bands exhibited progressive intensity enhancement with increasing polarization potential. Furthermore, the increasing Raman intensity ratio (I545/I463) with applied potential confirms the presence of β-MOOH intermediates on the Cat-500 catalyst surface and indicates a rising proportion of these highly active β-MOOH species within the system. These observations collectively indicate that electrochemical polarization induces phase transformation of Fe/Co/Ni sites in Cat-500 into β-MOOH configurations. The crystalline order within these formed phases promotes efficient adsorption of *OOH intermediates, consequently enhancing the OER process. In situ Raman spectroscopic analysis was conducted to probe the HER mechanism on Cat-500. As shown in Figure 12b, a broad spectral feature appearing in the 3100–3600 cm−1 range corresponds to interfacial water molecules at the catalyst-electrolyte interface. When the electrode potential was swept from 0 to −0.07 V, the water adsorption signal maintained highly stable intensity for Cat-500. This persistent interfacial water layer promotes the Volmer step in the HER process, thereby ensuring continuous proton availability for subsequent electrochemical reduction steps [43].

Figure 12.

In situ Raman spectra of (a) the OER and (b) the HER recorded for Cat-500.

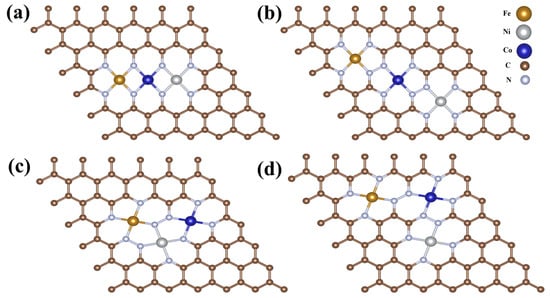

Beyond experimental characterization, the geometric and electronic structure of the FeCoNi-CNG catalyst was investigated through theoretical analysis. The Fe, Co, and Ni atoms are preferentially anchored at nitrogen-induced topological defect sites, forming stable M–N4 coordination structures [44]. First, variations in atomic radii lead to distinct metal-nitrogen bond lengths in the synthesized catalysts. As shown in Figure 13, within the M–N4 configuration, the Fe–N bond length (1.90 Å) [45] is shorter than both Co–N (1.96 Å) [46] and Ni–N (1.95 Å) [47]. This bond-length variation directly influences the coordination symmetry of the metal centers [48] and alters the lattice parameters of the carbon framework. Such structural distortion disrupts the integrity of the sp2-hybridized carbon network, thereby modulating the electronic structure and transforming these defect sites into catalytically active centers. Second, differences in electronegativity among the constituent elements induce significant electron redistribution. Electrons not only transfer from Fe (electronegativity: 1.83) and Co (1.88) to Ni (1.91), but also from the metal atoms to the carbon support. This results in reduced electron density in the d-orbitals of the metal centers. Consequently, the 1s orbital of hydrogen preferentially interacts with these electron-deficient metal d-orbitals, optimizing the hydrogen adsorption free energy [49]. The efficient charge transfer among Fe, Co, and Ni establishes strong electronic coupling within the FeCoNi/CNG catalyst. This interaction effectively modulates the d-electron configuration and promotes charge redistribution at the metal centers, enhancing overall charge transfer efficiency. As a result, the catalyst promotes the adsorption of hydrogen- and oxygen-containing radical intermediates in both the HER and OER. The synergistic effects among the multimetallic active sites collectively enhance the catalytic performance for both reactions [50].

Figure 13.

Possible structural configurations of Cat-500. (a) Compact Linear Type; (b) Loose Linear Type; (c) Compact Triangular Type; (d) Loose Triangular Type.

Furthermore, the incorporated nitrogen atoms establish strong electronic coupling with the metal single atoms through their lone pair electrons. This metal-support electronic synergy effectively modulates the position of the d-band center at the active sites, thereby optimizing the reaction kinetics [51]. Notably, nitrogen doping not only generates additional active sites but also acts synergistically with intrinsic edge defects and vacancy defects within the graphene oxide framework [52]. Finally, heteroatom doping increases the density of active sites while promoting synergistic electronic interactions among the different metal atoms. Through interatomic cooperation and coordinated electronic structures, this multifaceted strategy significantly enhances the overall catalytic activity [53,54].

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Oxide (CNG)

A mixture of 0.2 g graphene oxide (particle size < 300 μm, Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and 1.0 g melamine (99%, Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was thoroughly ground to achieve homogeneity. Then, the resulting mixture was transferred to an uncovered alumina crucible and placed in a tube furnace. Before heating, the furnace was purged with argon for 30 min to ensure an inert atmosphere. Subsequently, the sample was calcined at 600 °C for 1 h under an argon flow of 100 cm3/min, with a constant heating rate of 5 °C/min.

3.2. Synthesis of FeCoNi/CNG

The FeCoNi/CNG catalyst was prepared through an impregnation-negative pressure pyrolysis method. In a representative synthesis, 1.0 g of CNG support was dispersed in 20 mL of an aqueous solution containing equimolar concentrations (0.025 mol/L) of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, Co(NO3)2·6H2O, and Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (all 99% purity, Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd.). The suspension underwent ultrasonic dispersion for 30 min, followed by aging at ambient temperature for 2 h and subsequent drying at 80 °C for 24 h. The resulting product was then subjected to pyrolysis treatment in a tube furnace. This process was carried out under a negative pressure environment (relative pressure: −0.06 MPa) with a heating rate of 5 °C/min until reaching 500 °C, followed by maintaining at this temperature for 1.5 h, ultimately yielding a black product (named as Cat-500). For comparative analysis of pyrolysis temperature effects on electrocatalytic performance and metal loading, control samples Cat-400 and Cat-600 were synthesized under identical conditions with pyrolysis temperatures adjusted to 400 °C and 600 °C, respectively.

3.3. Material Characterization

The crystalline structures of the synthesized catalysts were examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD; D-Max 2500PC, Rigaku Co., Akishima-shi, Japan). Morphological characteristics were observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; ZEISS Sigma 360, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), while elemental mapping and composition were analyzed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Chemical states of surface species were determined through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; ESCALAB Xi+, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Surface functional groups were identified using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR; Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Raman spectroscopy (LabRAM Odyssey, Horiba, France) was employed to characterize structural defects and graphitization degree. Atomic-resolution imaging was performed via high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM; FEI Spectra 300, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Metal loadings (Fe, Co, Ni) were quantified by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Agilent 5110, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

3.4. Working Electrode Preparation

Nickel foam (NF) served as the conductive substrate for working electrode fabrication. Before electrochemical testing, the nickel foam was sequentially treated by immersion in acetone for 10 min and ultrasonic cleaning in 3.0 M hydrochloric acid for 20 min to eliminate surface oxides. The substrate was then carefully washed with ethanol and deionized water, air-dried, and stored under ambient conditions. For the catalyst ink formulation, 10 mg of the prepared catalyst (or commercial Pt/C for comparison) was dispersed in a solvent mixture containing 940 μL of ethanol, 1000 μL of deionized water, and 30 μL of Nafion binder. This mixture was sonicated for 40 min to achieve a homogeneous catalyst suspension. A 200 μL aliquot of the resulting ink was then precisely coated onto the pre-treated nickel foam substrate (1 cm × 1 cm geometric area) and allowed to dry completely at room temperature to obtain the final working electrode. The calculated loading of the catalyst on the NF was 1.02 mg cm−2.

3.5. Electrochemical Measurements

All electrochemical measurements were performed at ambient temperature using a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation (Chenhua, Shanghai, China) configured with a standard three-electrode system. The catalyst-loaded nickel foam functioned as the working electrode, with a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and graphite rod serving as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. The electrolyte consisted of 1.0 M KOH solution that had been saturated with high-purity nitrogen for at least 30 min prior to testing to establish an oxygen-free environment. Before data collection, the electrodes were stabilized through repeated cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans until stable profiles were obtained. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements were recorded at a sweep rate of 5 mV s−1 with 85% iR compensation applied. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted at an overpotential of 110 mV relative to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), covering a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz with 10 mV AC perturbation. The electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was determined from CV scans acquired at various rates (20–120 mV s−1) within non-faradaic potential windows. Stability was assessed through accelerated durability tests involving 1000 CV cycles at 50 mV s−1 in N2-saturated 1.0 M KOH, followed by LSV analysis in fresh electrolyte. Additional stability tests included chronoamperometry at −0.087 V vs. RHE for 15 h and chronopotentiometry (CP) at 10 mA cm−2 for 50 h. All reported potentials were converted to the RHE scale according to the equation: ERHE = ESCE + 0.241 + 0.059 × pH.

4. Conclusions

Fe–Co–Ni ternary single-atom catalysts were synthesized via an impregnation-negative pressure pyrolysis method, with one achieving a maximum metal atom loading of 6.78 wt%. Strong surface chelation was formed between the nitrogen-doped carbon support and the metal single atoms, which effectively stabilized the atomically dispersed active sites and prevented their aggregation. This approach overcomes the inherent limitations of conventional nanocatalysts, such as buried active sites and low utilization efficiency. The catalyst exhibits excellent performance for water electrolysis in alkaline media, delivering a current density of 10 mA cm−2 at overpotentials as low as 77 mV for the HER and 355 mV for the OER. Furthermore, it demonstrates robust electrochemical stability, maintaining consistent performance over 1000 cyclic voltammetry cycles and 50 h of CP testing. Synergistic interactions among the three metallic components cooperatively modulate the d-band center, optimize the adsorption/desorption energetics of reaction intermediates, and enhance charge transfer kinetics, resulting in intrinsic catalytic activity that surpasses that of monometallic and bimetallic systems. When integrated into a two-electrode alkaline electrolyzer as Cat-500(−)//Cat-500(+), the system achieves a current density of 10 mA cm−2 at a cell voltage of only 1.68 V. CP tests confirm the favorable stability of the catalyst, demonstrating its potential as a bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and Y.Z.; Data curation, M.G.; Formal analysis, H.Y. and M.G.; Funding acquisition, C.Z.; Investigation, H.Y. and C.Z.; Methodology, Y.Z.; Project administration, C.Z.; Resources, C.Z.; Supervision, C.Z. and Y.Z.; Visualization, M.G.; Writing—original draft, H.Y.; Writing—review and editing, C.Z. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Department of Qinghai Province, grant number 2022-QY-223.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and Challenges for a Sustainable Energy Future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, B. Recent Advances in Nanostructured Transition Metal Phosphides: Synthesis and Energy-Related Applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 4564–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, M.; Gao, B.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, J. Preparation of Fe, Co, Ni-Based Single Atom Catalysts and the Progress of Their Application in Electrocatalysis. Microstructures 2025, 5, 2025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalji, M.R.; Mahmoudi, F.; Bachas, L.G.; Park, C. MXene-Based Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting: Material Design, Surface Modulation, and Catalytic Performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Jia, W.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. Computational Chemistry for Water-Splitting Electrocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2771–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.-C.; Ren, J.-T.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Transition Metal Phosphide-Based Materials for Efficient Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution: A Critical Review. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 3357–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaud, A.; Diaz-Morales, O.; Han, B.; Hong, W.T.; Lee, Y.-L.; Giordano, L.; Stoerzinger, K.A.; Koper, M.T.M.; Shao-Horn, Y. Activating Lattice Oxygen Redox Reactions in Metal Oxides to Catalyse Oxygen Evolution. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Xiao, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; He, J.; Jiang, J.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L. Engineering Ru and Ni Sites Relay Catalysis and Strong Metal-Support Interaction for Synergetic Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 509, 161348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Hung, S.-F.; Wang, L.; Deng, L.; Zeng, W.-J.; Zhang, C.; Lin, Z.-Y.; Kuo, C.-H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Designing Neighboring-Site Activation of Single Atom via Tunnel Ions for Boosting Acidic Oxygen Evolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Wong, L.W.; Zheng, F.; Zheng, X.; Tsang, C.S.; Lai, K.H.; Shen, W.; Ly, T.H.; Deng, Q.; Zhao, J. Unraveling and Leveraging in Situ Surface Amorphization for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Media. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Huang, B.; Yi, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Li, Y.; Jia, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Anchoring Zero Valence Single Atoms of Nickel and Iron on Graphdiyne for Hydrogen Evolution. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, J.; Ye, C.; Jiang, Y.; Jaroniec, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Metal-Metal Interactions in Correlated Single-Atom Catalysts. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo0762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Khan, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, L.; Han, L. Boosting Oxygen Reduction with Coexistence of Single-Atomic Fe and Cu Sites Decorated Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 138938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, R.; Liu, Y.; Lian, X.; Xi, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Cui, B.; et al. Dual Pt-Ni Atoms Dispersed on N-Doped Carbon Nanostructure with Novel (NiPt)-N4C2 Configurations for Synergistic Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Sci. China Mater. 2023, 66, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Kang, L.; Schnegg, A.; Ruediger, O.; Chen, Z.; Allen, C.S.; Liu, L.; Chabbra, S.; DeBeer, S.; Heumann, S. Carbon-Supported Single Fe/Co/Ni Atom Catalysts for Water Oxidation: Unveiling the Dynamic Active Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, K.; Wang, P.; He, Y.; Liu, Z. Pt-Fe-Co Ternary Metal Single Atom Catalyst for toward High Efficiency Alkaline Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Energies 2023, 16, 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wei, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Kang, Z.; Dai, F.; Lu, X.; Sun, D. Phosphorus-Doped Iron-Nitrogen-Carbon Catalyst with Penta-Coordinated Single Atom Sites for Efficient Oxygen Reduction. Nano Res. 2022, 16, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Shi, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wang, M.; Su, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, J. Altering Local Chemistry of Single-Atom Coordination Boosts Bidirectional Polysulfide Conversion of Li–S Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ding, S.; Wu, C.; Gan, W.; Wang, C.; Cao, D.; Rehman, Z.; Sang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zheng, X.; et al. Synergistic Effect of an Atomically Dual-Metal Doped Catalyst for Highly Efficient Oxygen Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 6840–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Choi, J.-H. Single-Atom Doped Graphene for Hydrogen Evolution Reactions. 2D Mater. 2023, 10, 035026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Han, X.; Bai, J.; Wang, X.; Zheng, L.; Hong, C.; Li, Z.; Bai, J.; Leng, K.; et al. General Negative Pressure Annealing Approach for Creating Ultra-High-Loading Single Atom Catalyst Libraries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Feng, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Guan, H.-Y.; Argueta, M.; Wu, X.-L.; Liu, D.-S.; Austin, D.J.; Nie, P.; et al. Hierarchical Porous Carbon Pellicles: Electrospinning Synthesis and Applications as Anodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries with an Outstanding Performance. Carbon 2020, 157, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Kesama, M.R.; Tang, C.; Zhu, Y. Engineering Low-Coordination Single-Atom Cobalt on Graphitic Carbon Nitride Catalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 5517–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Zeng, S.; Jia, Z.; Ma, F.-X.; Sun, L.; Cheng, L.; Pan, J.; Bao, Y.; Mao, Z.; Bu, Y.; et al. Two-Dimensional Mineral Hydrogel-Derived Single Atoms-Anchored Heterostructures for Ultrastable Hydrogen Evolution. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Chen, S.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S.Z. Heteroatom-Doped Graphene-Based Materials for Energy-Relevant Electrocatalytic Processes. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5207–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, N.; He, R.; Peng, L.; Cai, D.; Qiao, J. Large-Scale Defect-Engineering Tailored Tri-Doped Graphene as a Metal-Free Bifunctional Catalyst for Superior Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reaction in Rechargeable Zn-Air Battery. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 285, 119811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Park, S.H.; Woo, S.I. Binary and Ternary Doping of Nitrogen, Boron, and Phosphorus into Carbon for Enhancing Electrochemical Oxygen Reduction Activity. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7084–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Guo, Y.; He, C.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, C.; Sun, X.; Ren, X. Creating High-Entropy Single Atoms on Transition Disulfides through Substrate-Induced Redox Dynamics for Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202405017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, W.; Liao, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Yan, N.; Han, X.; et al. Cohesive Energy Discrepancy Drives the Fabrication of Multimetallic Atomically Dispersed Materials for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xie, M.; Yu, S.; Zhan, X.; Wei, R.; Wang, M.; Guan, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. General Synthesis of High-Entropy Single-Atom Nanocages for Electrosynthesis of Ammonia from Nitrate. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Xing, B.; Chen, L.; Yi, G.; Huang, G.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z. Nitrogen-Doped Porous Co3O4/Graphene Nanocomposite for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Shen, S.; Zhong, W.; Pan, J. Phosphorus-Modified Cobalt Single-Atom Catalysts Loaded on Crosslinked Carbon Nanosheets for Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 3550–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Peng, H.; Ma, G.; Lei, Z.; Xu, Y. Recent Progress in Heteroatom Doping to Modulate the Coordination Environment of M–N–C Catalysts for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 2595–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yun, S.; Dang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, D. 1D/3D Rambutan-like Mott–Schottky Porous Carbon Polyhedrons for Efficient Tri-Iodide Reduction and Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, S.; Jia, X.; Xu, B.; Lin, H.; Yang, H.; Song, L.; Wang, X. Amorphous Nickel-Cobalt Complexes Hybridized with 1T-Phase Molybdenum Disulfide via Hydrazine-Induced Phase Transformation for Water Splitting. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Yang, T.; Wang, R.; Shen, R.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, B. Unveiling Complexities: Reviews on Insights into the Mechanism of Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Chin. J. Catal. 2025, 72, 48–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Xing, L.; Wang, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; et al. O-Bridged Co-Cu Dual-Atom Catalyst Synergistically Triggers Interfacial Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer: A New Approach to Sustainable Decontamination. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2423509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, C.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Hou, Y.; Lei, L.; Zhang, X. NiCoMo Hydroxide Nanosheet Arrays Synthesized via Chloride Corrosion for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Lian, Y.; Yang, W.; Lin, L.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Rümmerli, M.H.; et al. Topotactically Transformed Polygonal Mesopores on Ternary Layered Double Hydroxides Exposing Under-Coordinated Metal Centers for Accelerated Water Dissociation. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2006784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Xi, L.; Yu, Y.; Chen, N.; Sun, S.; Wang, W.; Lange, K.M.; Zhang, B. Single-Atom Au/NiFe Layered Double Hydroxide Electrocatalyst: Probing the Origin of Activity for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3876–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, M.W.; Bell, A.T. An Investigation of Thin-Film Ni–Fe Oxide Catalysts for the Electrochemical Evolution of Oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12329–12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Lei, Y. Trimetallic Oxyhydroxides as Active Sites for Large-Current-Density Alkaline Oxygen Evolution and Overall Water Splitting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 110, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Xing, Z.; Chang, J. Promoting Mechanism of the Ru-Integration Effect in RuCo Bimetallic Nanoparticles for Enhancing Water Splitting Performance. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94907243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ren, S.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, L.; Wu, J.; He, P.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Cobalt Single Atom Anchored on N-Doped Carbon Nanoboxes as Typical Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) for Boosting the Overall Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; An, Y.; Liu, S.; Sun, F.; Qi, H.; Wu, H.; He, Y.; Liu, P.; Shi, R.; Zhang, J.; et al. Highly Accessible and Dense Surface Single Metal FeN4 Active Sites for Promoting the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Bai, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Luo, X.; et al. Construction of Co-In Dual Single-Atom Catalysts for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction into CH4. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 371, 125196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Nishchakova, A.D.; Trubina, S.V.; Stonkus, O.A.; Asanov, I.P.; Okotrub, A.V.; Bulusheva, L.G. Ni-N4 Sites in a Single-Atom Ni Catalyst on N-Doped Carbon for Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid. J. Catal. 2021, 402, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-H.; Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Huang, X.; Ding, Y.; Su, B.-J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, J.-M.; et al. Regulating Electron Transfer over Asymmetric Low-Spin Co(II) for Highly Selective Electrocatalysis. Chem. Catal. 2022, 2, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Yi, K.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, X.; Huang, J.; Deng, Y.; Zeng, G. Single-Atom Catalysts for Hydrogen Generation: Rational Design, Recent Advances, and Perspectives. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Cao, K.; Gao, G.; Wang, C.; Lai, F.; Lu, S.; Ma, P.; Dong, W.; Liu, T.; et al. Unraveling the Electronegativity-Dominated Intermediate Adsorption on High-Entropy Alloy Electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wan, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y. Photoinduced Loading of Electron-Rich Cu Single Atoms by Moderate Coordination for Hydrogen Evolution. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; van Dijk, B.; Wu, L.; Maheu, C.; Hofmann, J.P.; Tudor, V.; Koper, M.T.M.; Hetterscheid, D.G.H.; Schneider, G.F. Predoped Oxygenated Defects Activate Nitrogen-Doped Graphene for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Li, H.; You, H.; Cao, M.; Cao, R. Encapsulating Metal Organic Framework into Hollow Mesoporous Carbon Sphere as Efficient Oxygen Bifunctional Electrocatalyst. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Fan, J.; Fan, Y.; Feng, C.; Jin, H.; Cai, Y.; Liu, M.-C. Cation Substituted Ni3S2 Nanosheets Wrapped Zn0.76Co0.24S Nanowire Arrays Prepared with in-Situ Oxidative Etching Strategy for High Performance Solid-State Asymmetric Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).